Summary

Aims:

In a study of ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast, we identified five genes at chromosome 17q21.33 that were over-expressed in high grade cases, and showed a correlation between expression and gene copy number. The aim of this study was to investigate potential drivers of genomic amplification at 17q21.33.

Methods:

Analysis of high resolution comparative genomic hybridisation and published data specified a minimum region of amplification at 17q21.33. Prohibitin (PHB) expression was examined by immunohistochemistry in 285 invasive breast cancers. Gene copy number was examined by fluorescence in situ hybridisation.

Results:

The minimum region of amplification at 17q21.33 included ten genes with PHB selected as a candidate driver. Increased PHB expression was associated with higher grade breast cancer and poorer survival. Amplification of PHB was detected in 13 of 235 cases (5.5%) but was not associated with PHB expression. PHB amplification was most common in the ERBB2+ breast cancer subtype, although high expression was most prevalent in basal-like and luminal B cancers.

Conclusions:

Amplification at 17q21.33 is a recurrent feature of breast cancer that forms part of a ‘firestorm’ pattern of genomic aberration. PHB is not a driver of amplification, however PHB may contribute to high grade breast cancer.

Keywords: Breast cancer, genomic amplification, grade, prohibitin

INTRODUCTION

Biological heterogeneity is a particular feature of breast cancer that manifests clinically as striking variation in the patterns of disease presentation, progression and response to treatment. The origin of this diversity is largely unknown, although there has been speculation that different cancer types may reflect distinct cell types in the normal breast.1 More certain is the impact of key genetic lesions on breast cancer biology with over-expression of the ERBB2 (HER2) oncoprotein as a consequence of amplification at 17q12.21, the definitive example of a genomic lesion that has a critical influence on cancer cell growth. By analogy to ERBB2, high level expression of genes in recurrent regions of genomic amplification in breast cancer may indicate the location of other ‘driver’ genes.

In a previous study examining gene expression and genomic profiles of microdissected in situ breast lesions, we reported a binary molecular grade classification for ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), based on differential expression at 173 nucleotide probes between DCIS associated with grade 1 and grade 3 invasive breast cancer.2 A positive correlation between gene expression and copy number (Pearson correlation, r>0.5) existed for 13 of the 173 grade associated probes in an expanded sample set of microdissected in situ lesions (Supplementary Table 1, http://links.lww.com/PAT/A11). Probes for five of these genes co-located at chromosome 17q21.33; solute carrier family 35, member B1 (SLC35B1), hypothetical protein PRO1855 (PRO1855), essential meiotic endonuclease 1 homolog 1 (S. pombe) (EME1), prohibitin (PHB) and epsin 3 (EPN3). All of these genes showed relatively high expression in high molecular grade DCIS, suggesting that 17q21.33 may be influential in high grade breast cancer growth.2

Chromosome 17q is a gene rich region of the genome that is particularly susceptible to complex copy number changes in breast cancer.3 This was apparent in our study of DCIS, and in relation to the expression of grade-associated genes, a distinct region of amplification at 17q21.33 was noted in a proportion of high molecular grade cases. This is consistent with other genomic profiling studies of breast cancer that have described a region of recurrent amplification at 17q21.33.4–11 For example, Chin et al. reported gain or amplification in this region in around 19% of 171 breast tumours and 22% of 49 breast cancer cell lines.8 A relationship between gene copy number and expression in this region has also been documented in a number of studies.4,8,11–13 A further repeated observation has been that 17q21.33 and ERBB2 amplification commonly co-exist in breast cancer, forming part of an ‘amplifier’ or ‘firestorm’ pattern of genomic aberration.6,7,14 However, in relation to the impact on selective gene expression, it is important to acknowledge that the ERBB2 and 17q21.33 amplicons are distinct, separated by approximately 10 Mb, and can occur independently.14

On the basis of these data indicating that 17q21.33 is a region of recurrent amplification in breast cancer, with an impact on gene expression, and that genes in this region are relatively over-expressed in high molecular grade DCIS, we hypothesised that one or more genes at 17q21.33 may contribute to high grade breast cancer growth. To investigate this issue we used high resolution genomic profiling to localise a minimum region of amplification at 17q21.33. On the basis of these data in combination with our previous study, we identified prohibitin (PHB, PHB1) as a candidate driver of amplification at this location.

Prohibitin (PHB) is a ubiquitously expressed protein with a variety of documented functions and subcellular locations. For example, in mitochondria, PHB forms a complex with the related protein prohibitin 2 (PHB2) to provide structural support, as well as contributing to mitochondrial development, cellular respiration and possibly control of apoptosis.15 At the plasma membrane, phosphorylated PHB is a critical intermediate in the interaction of Ras with Raf, leading to activation of the MEK-ERK and PI3K signalling pathways with demonstrated effects on cellular adhesion and migration that promote malignant progression.16–18 In this study, we examined the possibility that PHB was a driver of amplification at 17q21.33 and the clinicopathological correlates of PHB expression in breast cancer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient samples and data

This work was conducted with primary approval from the Sydney West Area Health Service Human Research Ethics Committee (now the Western Sydney Local Health District Human Research Ethics Committee).

Chromosome 17q targeted high-resolution comparative genomic hybridisation (CGH) was performed on 16 samples of amplified DNA from a set of 50 samples that had been previously analysed using lower resolution array-CGH.2 The original series included samples extracted from foci of DCIS, lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS), and atypical ductal hyperplasia (ADH) microdissected from frozen sections of 46 invasive breast cancer specimens as previously described.2 The high resolution CGH subgroup consisted of DCIS (n = 15) and LCIS (n = 1). Two DCIS samples were different morphological subtypes microdissected from the same invasive breast cancer. Other samples were from distinct invasive breast cancer cases.

Tissue microarray (TMA) sections used for immunohistochemical and fluorescent in situ hybridisation (FISH) studies were from a cohort of primary invasive breast cancer patients that has also previously been described.19 Data on histological grade, oestrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), ERBB2 (HER2) amplification and cluster grouping were derived from the previously published study.19

In addition, a publicly available Affymetrix 500K Single Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP) array dataset published by Haverty et al. in 200910 was accessed from Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/).

Targeted high resolution CGH

Custom microarrays (Nimblegen, USA) were designed with complete genome coverage (18 529 probes covering all chromosomes excluding chromosome 17) and high resolution coverage of chromosome 17q (160 096 probes on chromosome 17). Amplified DNA was quantified using Quant-iT PicoGreen dsDNA Assay Kit (Invitrogen, USA). DNA was labelled using the Bioprime Array CGH Labeling Module (Invitrogen) with modifications. Specifically, 20 μL 2.5X Random Primer Mix was combined with 10 μg DNA in 21 μL nuclease free water and heat-denatured. To the cooled DNA was added: 5 μL of nucleotide mix (1.2mM each of dATP, dGTP, dCTP, and 0.6mM dTTP), 3 nmol of appropriate labelled nucleotide (test DNA and reference DNA labelled with Cy5-dUTP and Cy3-dUTP, respectively), and 1 μL Exo-Klenow. Reaction was incubated at 37°C for 2 h, acidified with 10 μL 3 M sodium acetate (pH 5.2), and purified using QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen, USA). Labelled test DNA was combined with labelled reference DNA, diluted to 150 μL with nuclease free water, and combined with 50 μL Cot-1 DNA (Invitrogen), 50 μL 10X Blocking Agent (Agilent, USA), and 250 μL 2X Hybridization Buffer (Agilent). Labelled DNAs were heat-denatured and pre-blocked at 37°C for 30 min. The microarray was hybridised in a rotisserie at 65°C for 40 h. Washing was according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Arrays were scanned in an Agilent DNA Microarray Scanner and processed with Feature Extraction Software (Agilent, CGH-v4_95_Feb07) using build HG18. Microarray raw data are available through the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) repository, accession number GSE33249.

The extracted copy number data were loaded into Nexus 3.1 (Biodiscovery, USA) for analysis.

PHB immunohistochemistry

PHB expression was determined by manual immunohistochemical staining of stored TMA sections using a mouse monoclonal anti-PHB antibody (Clone II-14–10, 1:20 dilution; Abcam, UK). In each 0.6mm tissue core, PHB staining was scored as negative (0), equivocal (0.5), low (1), moderate (2) or high (3) with the median score from up to three tissue cores forming the overall score for each case. Scoring was performed initially by two independent observers (LW/RB). Cases showing an inter-observer scoring discrepancy ≥2 were re-examined and revised in some cases by one observer (RB). The mean score from two observers was then used to derive a final PHB score of negative/low (mean ≤1.5), moderate (mean >1.5, ≤2.5), or high (mean >2.5).

FISH

FISH of stored TMA sections was performed to assess PHB copy number. BAC clone, RP11–472H5 (BACPAC Resource Centre, USA), containing the PHB gene and adjacent NGFR gene was cultured in DH10 E.coli and BAC DNA isolated using the Qiagen large-construct kit (Qiagen). BAC DNA was amplified using GenomiPhi V2 (GE Healthcare) before labelling with ChromaTide Alexa-488–5-dUTP (Invitrogen) by nick translation. TMA sections were co-hybridised with 300 ng of Alexa-488 labelled PHB BAC probe and a Chromosome 17 centromeric probe (SE17, Poseidon Satellite Enumeration Probe) (Kreatech Diagnostics, The Netherlands) and counterstained with DAPI (0.1 μg/mL) (Sigma-Aldrich, USA). Signals were visualised using an Olympus BX40 fluorescence microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) with TXR, FITC and UV filters. Images from individual fluorescence channels were captured with a SPOT RT KE digital camera (Diagnostic Instruments, USA) and assessed using ImagePro Plus 5.0 software (Media Cybernetics, USA). Green (PHB) and red (chromosome 17 centromeric) signals were manually counted in ten individual nuclei per tissue core. As there were three cores per case included on TMAs, up to 30 cells per case were scored if available (median 29 cells, range 8 to 30 cells). Individual nuclei were identified on a merged green/red/blue image and saved as ‘areas of interest’ (AOI). Green and red signals within these AOI were counted on their respective single fluorescence channel images. Image brightness and contrast enhancement were used as necessary to increase the signal to background and improve signal interpretation. Green to red signal ratios of <2, 2–4 and >4 were classified as non-amplified, low level amplification and high level amplification, respectively. The same scoring was used to evaluate ERBB2 amplification by FISH in the previously published study and those data have been used to designate ERBB2 (HER2) status in this report.19 To examine the veracity of the BAC probe, FISH was performed on paraffin sections of a PHB amplified and non-amplified cancer included in the high resolution CGH study, as well as the 17q21.33 amplified BT474 and un-amplified MCF7 cell lines.7,20

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using PASW Statistics version 17.0 software (IBM Corporation, USA). Two-tailed tests with a significance level of 5% were used throughout. Spearman rank correlation (r) was used to quantify the degree of association between gene expression and gene copy number measurements. Supervised analysis with the limma package from Bioconductor was used to identify genes that were significantly differentially expressed between high grade and low grade DCIS; benign breast tissue and DCIS; and (ERBB2) HER2 positive and negative DCIS lesions (as defined by immunohistochemical staining) (p values reported were adjusted for multiple comparisons). Chi squared or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate, were used to test for associations between PHB expression and copy number and clinicopathological features. Where there was a natural ordering of the categories, a Chi squared test for linear association or the equivalent permutation test as appropriate were used. Kruskal–Wallis non-parametric ANOVA was used to test for association between the PHB FISH ratio and PHB expression. Kaplan–Meier survival curves were used to illustrate the survival distributions and log-rank tests used to compare them.

RESULTS

A minimum region of amplification at 17q21.33 includes genes over-expressed in high molecular grade DCIS

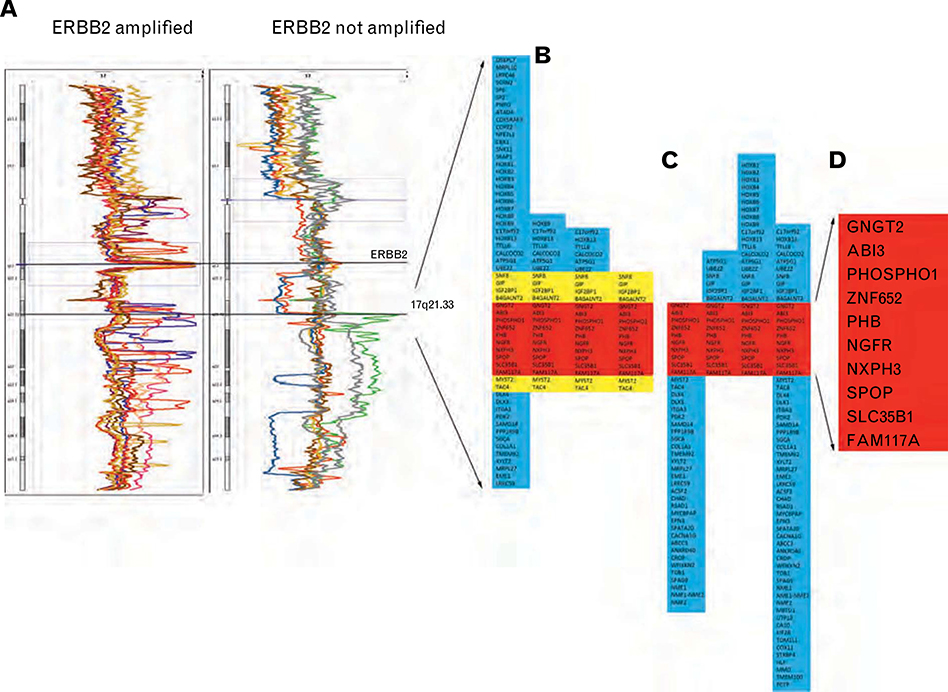

In a previous genomic profiling study, complex alterations of 17q were identified in a number of samples of microdissected in situ breast carcinoma. To examine this chromosomal region in more detail, 16 samples (15 DCIS and 1 LCIS) were selected for re-analysis of chromosome 17q by high-resolution CGH (Fig. 1A). Initial quality control analyses identified one DCIS sample with poor hybridisation results. This sample did not have a detectable ERBB2 or 17q21.33 amplification and was excluded from further analysis. Of the remaining 15 samples, nine showed amplification at the ERBB2 (HER2) locus and four showed a distinct region of amplification at 17q21.33. In three samples, including two microdissected from the same invasive breast cancer, there was amplification at both ERBB2 and 17q21.33.

Fig. 1.

(A) High resolution CGH mapping of 17q in ERBB2 amplified (n = 9) and non-amplified (n = 7) in situ carcinoma samples. Four samples showed a region of amplification at 17q21.33. (B) Genes included in the 17q21.33 amplicon. (C) Genes included in the same 17q21.33 region from the high resolution CGH study of Haverty et al.10 (D) Ten genes included in the minimum region of overlap in amplification at 17q21.33 in eight cases.

These genomic features were also examined in published data from a high resolution SNP study of 51 invasive breast cancers by Haverty et al.10 Their cohort included five ERBB2 amplified and four 17q21.33 amplified cases with three cases showing amplification at both sites.

The 17q21.33 amplicon was variable in size in the combined series of eight amplified samples; spanning between 16 and 62 genes (Fig. 1B, this study; Fig. 1C, Haverty et al.). A minimum region of overlap included ten genes (Fig. 1D). In our previous study, there was a correlation between gene copy number and expression (r>0.5) for four of these ZNF652, PHB, SLC35B1 and FAM117A (LOC81558) (Table 1). In addition the expression of two genes, PHB and SLC35B1, was significantly higher in DCIS associated grade 3 compared with grade 1 invasive breast cancer. The expression of PHB was also significantly higher in microdissected in situ carcinoma compared with benign breast tissue. None of the four genes were differentially expressed between samples from ERBB2 positive and ERBB2 negative breast cancer (Table 1).

Table 1.

Features of expression of 10 genes in the minimum region of amplification at 17q21.33 in a previous study of microdissected DCIS, LCIS and ADH samples2

| Gene | A | B | C | D |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expression/copy number correlation (r) | DCIS in grade 1 vs grade 3 cancer (Adj p value) | DCIS/LCIS vs benign (Adj p value) | ERBB2+vs ERBB2−(Adj p value) | |

| GNGT2 | 0.16 | |||

| ABI3 | 0.06 | |||

| PHOSPHO1 | 0.35 | |||

| ZNF652 | 0.54 | 0.8 | 0.55 | 0.97 |

| PHB* | ||||

| H200006074 | 0.55 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 1 |

| H300003694 | 0.52 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.92 |

| H300009508 | 0.53 | 0.1 | 0.02 | 0.91 |

| NGFR | −0.06 | |||

| NXPH3 | −0.07 | |||

| SPOP | 0.45 | |||

| SLC35B1 | 0.83 | 0.01 | 0.1 | 0.87 |

| FAM117A | 0.58 | 0.5 | 0.02 | 1 |

3 probes.

Based on 50 samples; DCIS (46), LCIS (1), ADH (3).

Based on 23 DCIS samples.

Based on 56 samples; DCIS (47), LCIS (2), benign (7).

Based on 45 samples; DCIS (44), LCIS (1).

ADH, atypical ductal hyperplasia; Adj, adjusted; DCIS, ductal carcinoma in situ; LCIS, lobular carcinoma in situ.

These data showing an association between PHB copy number and expression, in combination with relatively high level expression in high grade cancer compared with low grade cancer and normal cells, respectively, identified PHB as a potential driver of amplification at 17q21.33.

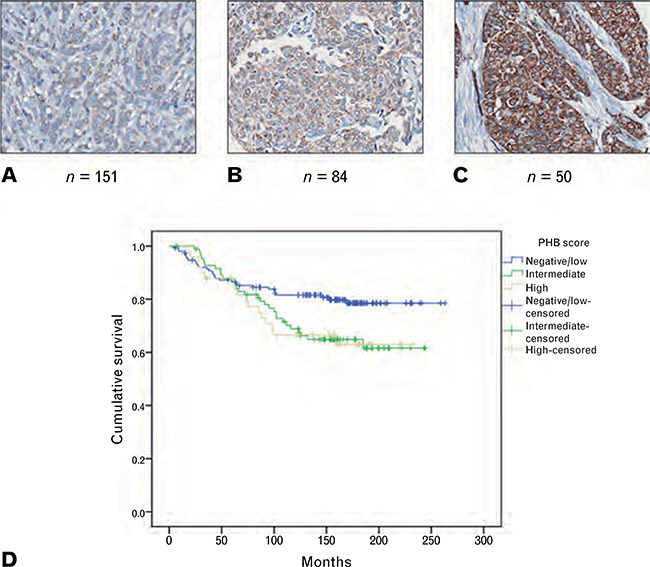

High level expression of PHB is associated with reduced survival in invasive breast cancer

To investigate the potential role of PHB as a driver of high grade breast cancer growth, expression of PHB was examined by immunohistochemical staining of TMA sections from a previously described invasive breast cancer cohort19 (Table 2A). A degree of granular cytoplasmic staining was present in almost all cases, although the intensity of staining was variable across the cohort with PHB expression designated negative/low in 151 of 285 cases (53%), intermediate in 84 (29.5%) and high in 50 (17.5%) (Fig. 2A–C, Table 2B). PHB expression was significantly associated with increasing tumour size (p = 0.044) and grade (p = 0.007). There was a borderline significant association with ER negativity (p = 0.053), but not age (p = 0.213), lymph node status (p = 0.859), PR (p = 0.174) or ERBB2 status (p = 0.206) (Table 2B). There was a significant association between PHB expression and survival (p = 0.039) with the subgroup of PHB negative/low cases showing better cancer specific survival than intermediate and high expressing cases (Fig. 2D).

Table 2.

Clinicopathological features of invasive breast cancer in relation to PHB expression and copy number

| Characteristic | A |

B |

C |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PHB expression |

PHB copy number |

|||||||||||||

| Total n | (%) | Negative/Low n | (%) | Intermediate n | (%) | High n | (%) | P | Non-amplified n | % | Amplified n | (%) | P | |

| Age at diagnosis, years | (n = 370) | (n = 285) | (n = 235) | |||||||||||

| <36 | 23 | (6.2) | 4 | (22.2) | 9 | (50.0) | 5 | (27.8) | 0.213 | 13 | (81.3) | 3 | (IS.8) | 0.445 |

| 36–50 | 117 | (31.6) | 51 | (58.0) | 25 | (28.4) | 12 | (13.6) | 64 | (94.1) | 4 | (5.9) | ||

| 51–65 | 144 | (38.9) | 61 | (52.1) | 32 | (27.4) | 24 | (20.5) | 98 | (9S.0) | 2 | (2.0) | ||

| 66–75 | 66 | (17.8) | 26 | (53.1) | 14 | (28.6) | 9 | (18.4) | 37 | (92.5) | 3 | (7.5) | ||

| >75 | 20 | (5.4) | 9 | (69.2) | 4 | (30.8) | 0 | (0) | 10 | (90.9) | 1 | (9.1) | ||

| Invasive tumour size, mm | (n = 359) | (n = 276) | (n = 227) | |||||||||||

| 0–10 | 62 | (17.3) | 25 | (55.6) | 13 | (28.9) | 7 | (15.6) | 0.044 | 37 | (97.4) | 1 | (2.6) | 0.242 |

| 11–20 | 160 | (44.6) | 70 | (56.9) | 40 | (32.5) | 13 | (10.6) | 94 | (94.9) | 5 | (5.1) | ||

| >20 | 137 | (38.2) | 51 | (47.2) | 28 | (25.9) | 29 | (26.9) | S3 | (92.2) | 7 | (7.8) | ||

| Lymph node status, no. positive nodes | (n =341) | (n = 263) | (n = 216) | |||||||||||

| 0 | 205 | (60.1) | 81 | (54.0) | 43 | (28.7) | 26 | (17.3) | 0.859 | 116 | (92.8) | 9 | (7.2) | 0.583 |

| 1–3 | SS | (25.8) | 38 | (52.8) | 22 | (30.6) | 12 | (16.7) | 54 | (96.4) | 2 | (3.6) | ||

| >3 | 48 | (14.1) | 21 | (51.2) | 13 | (31.7) | 7 | (17.1) | 33 | (94.3) | 2 | (5.7) | ||

| Tumour grade | (n = 353) | (n = 273) | (n = 225) | |||||||||||

| 1 | 101 | (27.3) | 49 | (65.3) | 19 | (25.3) | 7 | (9.3) | 0.007 | 52 | (98.1) | 1 | (1.9) | 0.126 |

| 2 | 128 | (34.6) | 49 | (49.0) | 32 | (32.0) | 19 | (19.0) | 84 | (95.5) | 4 | (4.5) | ||

| 3 | 124 | (33.5) | 46 | (46.9) | 29 | (29.6) | 23 | (23.5) | 77 | (91.7) | 7 | (8.3) | ||

| ER status | (n = 295) | (n = 272) | (n = 230) | |||||||||||

| Positive | 191 | (64.7) | 99 | (54.7) | 56 | (30.9) | 26 | (14.4) | 0.053 | 142 | (93.9) | 6 | (6.1) | 0.528 |

| Negative | 104 | (35.3) | 44 | (48.4) | 23 | (25.3) | 24 | (26.4) | 77 | (95.9) | 5 | (4.1) | ||

| PR status | (n = 298) | (n = 275) | (n = 231) | |||||||||||

| Positive | 168 | (56.4) | 87 | (49.1) | 49 | (27.6) | 23 | (23.3) | 0.174 | 129 | (92.9) | 4 | (7.1) | 0.211 |

| Negative | 130 | (43.6) | 57 | (54.7) | 32 | (30.8) | 27 | (14.5) | 91 | (97.0) | 7 | (3.0) | ||

| ERBB2 status* | (n = 299) | (n = 274) | (n = 232) | |||||||||||

| Negative | 256 | (85.6) | 119 | (50.9) | 73 | (31.2) | 42 | (17.9) | 0.206 | 193 | (97.5) | 5 | (2.5) | 0.002 |

| Positive | 43 | (14.4) | 25 | (62.5) | 7 | (17.5) | 8 | (20.0) | 28 | (82.4) | 6 | (17.6) | ||

| Molecular subtype † | (n = 270) | (n = 252) | (n = 216) | |||||||||||

| Luminal A | 135 | (50.0) | 72 | (58.1) | 33 | (26.6) | 19 | (15.3) | 0.051 | 102 | (99.0) | 1 | (1.0) | 0.001 |

| Luminal B | 75 | (27.8) | 29 | (40.8) | 27 | (38.0) | 15 | (21.1) | 59 | (93.7) | 4 | (6.3) | ||

| ERBB2+ | 35 | (13.0) | 21 | (63.6) | 7 | (21.2) | 5 | (15.2) | 22 | (78.6) | 6 | (21.4) | ||

| Basal-like | 25 | (9.3) | 11 | (45.8) | 4 | (16.7) | 9 | (37.5) | 22 | (100.0) | 0 | (0) | ||

Fig. 2.

(A–C) Examples of low, intermediate and high level immunohistochemical staining of invasive breast cancers for PHB. (D) Kaplan–Meier survival curve demonstrating better cancer specific survival associated with negative/low level PHB expression compared with moderate and high level expression in invasive breast cancer (n = 285; p = 0.039).

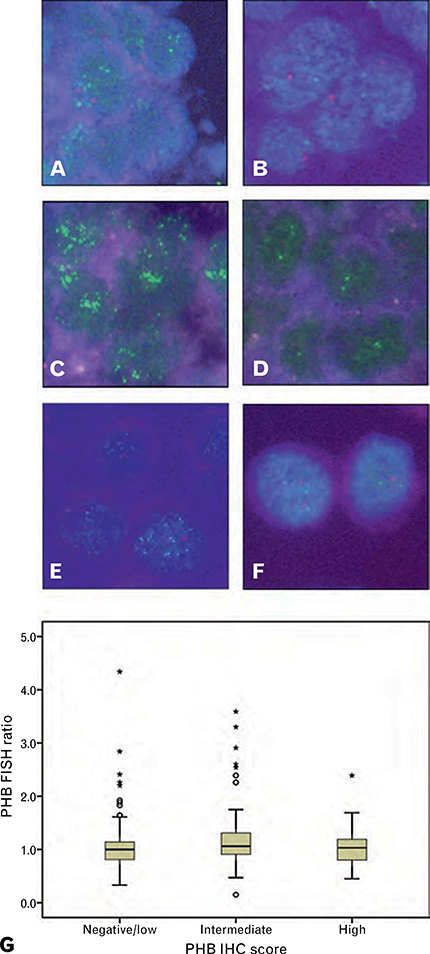

Amplification at 17q21.33 was uncommon in breast cancer and was not related to PHB expression

To examine the relationship between PHB expression and gene copy number in invasive breast cancer, amplification at the 17q21.33 region including PHB was examined by FISH (Fig. 3A–F). In the invasive breast cancer cohort, results were obtained for 235 cases, of which 12 (5.1%) showed low level amplification at PHB and one case showed high level amplification (total amplified 13/235, 5.5%). Data on ERBB2 amplification (FISH ratio >2) were available for 232 cases. There was a significant association between PHB and ERBB2 amplification (p = 0.002) with six of 11 (54.5%) PHB amplified cases also ERBB2 amplified, and six of 34 ERBB2 amplified cases showing amplification at PHB (17.6%) (Table 2C). PHB amplification was not associated with age at diagnosis (p = 0.445), tumour size (p = 0.242), lymph node status (p = 0.583), grade (p = 0.126), ER (p = 0.528) or PR (p = 0.211) (Table 2C).

Fig. 3.

(A–F) FISH showing a 17q21.33 probe including PHB (green) relative to a chromosome 17 centromeric probe (red). (A,B) Invasive breast cancers from the tissue microarray cohort. (C,D) An amplified and un-amplified case included in the high resolution CGH study. (E,F) 17q21.33 amplified BT474 and unamplified MCF7 breast cancer cells. (G) The relationship between PHB FISH ratio and PHB immunohistochemical score in invasive breast cancer (n = 233; p = 0.154).

There was no association between the PHB FISH ratio and PHB immunohistochemical score (p = 0.154) indicating that high level expression of PHB in invasive breast cancer was not related to increased gene copy number (Fig. 3G).

PHB amplification and expression are differentially associated with breast cancer subtypes

We have previously reported sub-categorisation of this cohort of invasive breast cancers, on the basis of histological and biomarker features, into prognostic subgroups that were consistent with the major ‘molecular’ breast cancer subtypes of luminal A, luminal B, ERBB2+ and basal-like, respectively.19 Comparison of these subtype allocations with PHB amplification showed a significant association (p = 0.001), with the majority of PHB amplified cases belonging to the ERBB2+ subtype and the remainder belonging to the luminal subgroups (Table 2C). There was a borderline significant association between PHB expression and breast cancer subtypes (p = 0.051). However, in contrast to amplification, the basal-like subgroup which had no PHB amplified cases showed the greatest proportion (37.5%) with high level PHB expression (Table 2B).

DISCUSSION

A discrete region of genomic amplification involving chromosome 17q21.33 has been repeatedly identified in a proportion of breast cancers, and an association between gene copy number and expression in this region has also been documented.4,8,11–13 These features were apparent in our previous study of microdissected DCIS, and in addition we observed distinctive over-expression of a number of genes at 17q21.33 in high molecular grade cases.2 These data suggested that amplification at 17q21.33 could provide a selective advantage to breast cancer by supporting high level expression of one or more genes that actively contributed to an aggressive tumour phenotype. To investigate this possibility and to localise potential driver genes at 17q21.33, we re-examined a number of microdissected DCIS samples with complex changes at 17q using high-resolution CGH. In combination with a published high resolution genomic profiling breast cancer dataset from Haverty et al.,10 a minimum region of overlap in amplification at 17q21.33 in eight samples was identified. This included 10 genes, of which PHB and SLC35B1 were included in our high molecular grade profile, with PHB also showing higher expression in in situ carcinoma compared with benign breast tissue.

In breast cancer, the main interest in PHB has been in the tumour suppressor function of the 3’ untranslated region (UTR) of the PHB transcript which is abolished by a rare single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP).21 This SNP has been inconsistently associated with breast cancer risk, although there is evidence that it may act as a modifier of breast and ovarian cancer risk in BRCA1/2 mutation carriers.22–25 In consideration of the PHB protein, relatively high levels have been documented in a range of cancers including breast cancer.26,27 In addition to a key supportive role mitochondrial PHB plays in cellular respiration,15,28 in cancer cells PHB expression has been shown to generally promote an aggressive malignant phenotype. For example, PHB has been implicated in cancer cell invasion, metastasis and reduced survival of animal models via activation of Ras-Raf.18 A cytoprotective effect of PHB has been demonstrated in cancer cell lines with reduced levels of PHB associated with increased sensitivity to cytotoxic agents,29,30 and reduced cellular proliferation associated with reduction of PHB in vitro has also been demonstrated.31 A range of other functions have been attributed to PHB including transcriptional regulation, and there is evidence that PHB can act as a co-repressor of oestrogen receptor activity in breast cancer cells.32 On the basis of such data, it was plausible that high levels of PHB expression could provide an advantage to the growth of high grade breast cancer.

In a well characterised cohort of 285 invasive breast cancers, immunohistochemical staining showed variable levels of PHB. In keeping with PHB expression as a component of a high molecular grade gene expression signature, there was a significant association between PHB and the poor prognostic features of larger tumour size and high histological grade in invasive breast cancer. Moreover, breast cancer specific survival in individuals with cancers expressing intermediate and high levels of PHB was reduced compared with negative/low expressing cases.

A characteristic pattern of genomic rearrangement that can affect the long arm of chromosome 17 in breast cancer is a series of relatively narrow amplification peaks, frequently but not always including the ERBB2 amplicon. Hicks et al. denoted this pattern as a ‘firestorm’ and speculated that the effect was created by intensive, localised recombination pressure rather than more generalised genomic instability.14 In a series of 23 cancers showing a 17q firestorm pattern, these investigators identified at least five distinct amplification peaks including ERBB2 and 17q21.33.14 This pattern of genomic change is in keeping with our observations from high-resolution CGH of 15 microdissected in situ carcinoma samples previously shown to have complex changes on 17q; nine cases were ERBB2 amplified, four showed amplification at 17q21.33 and three cases were amplified at both sites. Investigation of a larger inclusive series of invasive breast cancers by FISH gave consistent results, and a broader perspective on the relative frequency of these events since PHB amplification was detected in only 5.5% of cases compared with 14.6% amplified at ERBB2, with a non-exclusive but statistically significant association between amplification at the two sites (p = 0.002).

In the case of PHB, the absence of a relationship between gene amplification and high level PHB protein expression refuted the possibility that PHB was a driver of amplification at 17q21.33. This failure of association between copy number and expression of PHB was counter-intuitive in view of the link between high PHB expression and poor prognosis, high grade breast cancer and also between PHB and ERBB2 amplification. However, insight into these observations came from comparison of PHB expression/amplification characteristics and breast cancer subtypes.

We have previously reported sub-classification of this cohort of invasive breast cancers into four subgroups by hierarchical cluster analysis based on components of histopathological grade, ER, ERBB2 (HER2) amplification and CK5/6 expression.19 These subgroups had phenotypic and survival characteristics that were strongly concordant with the luminal A, luminal B, ERBB2+ and basal-like molecular subtypes of breast cancer, respectively.19 The majority (6/11) of PHB amplified cancers belonged to the ERBB2+ subtype category, with the remainder distributed between the luminal subtypes. A striking finding was that there were no PHB amplified cancers in the poor-prognosis basal-like subgroup, although this subgroup showed the largest proportion of high PHB expressing cases in this cohort.

Our finding of an absence of PHB amplification in basal-like breast cancer is consistent with reports that, in contrast to the ‘firestorm’ form of genomic change characteristic of ERBB2+ cancer, basal-like tumours tend to show a pattern of widespread genomic aberration without high level amplification described as ‘complex’ or ‘sawtooth’.5,13,14 Furthermore, in the study by Natrajan et al. that specifically documented genomic changes in breast cancers subtypes, 17q21.33 amplification was also identified as a feature of ERBB2+ and luminal, but not basal-like breast cancers.5

Interestingly, studies investigating PPM1D (protein phosphatase magnesium-dependent δ) as a potential driver of another discrete 17q amplicon at 17q23.2 showed some similar results, with a 6% overall rate of amplification, association with ERBB2 amplification, and amplification seen only in luminal or ERBB2 breast cancer types.5,33 However, in contrast to PHB, amplification of PPM1D was associated with high level expression at the transcript level in a validation cohort, although there was no apparent relationship between PPM1D expression and clinicopathological features of breast cancer or survival.33

High level expression of PHB in basal-like breast cancers has not previously been described to our knowledge. However, a possible explanation comes from the fact that PHB expression is directly up-regulated by MYC (c-Myc), and in cancer this may form part of a mechanism that reduces oxidative stress and supports cancer cell growth in hypoxic conditions.34 MYC is expressed at high levels in basal-like breast cancer and gene expression profiling studies have also demonstrated that a MYC activation signature is characteristic, suggesting a potentially important role for MYC in the pathogenesis of basal-like breast cancer.35,36 Interestingly, in a study of 245 breast cancers, Rodriguez-Pinilla et al. found that MYC amplification was not a feature of the basal-like breast cancer phenotype, being less common in basal-like than ERBB2+ and luminal cases.37 This in combination with other evidence that MYC is not consistently over-expressed when the MYC gene on chromosome 8q4 is amplified,12 is similar to our finding of discordant amplification and expression of PHB across breast cancer subtypes. Together these results suggest that high level expression of both MYC and PHB in basal-like breast cancers may be an adaptive response rather than an oncogenic effect.

In this study we have delineated a region of recurrent amplification on chromosome 17q21.33 that included a number of genes highly expressed in high molecular grade breast cancer. This genomic feature was significantly associated with amplification at ERBB2, consistent with a ‘firestorm’ pattern of localised high level amplification which is itself associated with high grade forms of breast cancer. We did not find evidence to support PHB as a driver of 17q21.33 amplification. However, high level expression of PHB was associated with high grade breast cancer and poor survival, suggesting that PHB may contribute to the growth of an aggressive tumour type.

Acknowledgements:

The authors gratefully acknowledge helpful advice from Clinical Associate Professor Anna de Fazio and Associate Professor Helen Rizos on aspects of this work.

Conflicts of interest and sources of funding: This work was supported by funding by the Cure Cancer Australia Foundation, the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (NHMRC; grant number 306700), the Cancer Institute New South Wales (CINSW) and the University of Sydney Cancer Research Fund. RLB was a CINSW Fellow. The authors state that there are no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Visvader JE. Keeping abreast of the mammary epithelial hierarchy and breast tumorigenesis. Genes Dev 2009; 23: 2563–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balleine RL, Webster LR, Davis S, et al. Molecular grading of ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. Clin Cancer Res 2008; 14: 8244–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Orsetti B, Nugoli M, Cervera N, et al. Genomic and expression profiling of chromosome 17 in breast cancer reveals complex patterns of alterations and novel candidate genes. Cancer Res 2004; 64: 6453–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andre F, Job B, Dessen P, et al. Molecular characterization of breast cancer with high-resolution oligonucleotide comparative genomic hybridization array. Clin Cancer Res 2009; 15: 441–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Natrajan R, Lambros MB, Rodriguez-Pinilla SM, et al. Tiling path genomic profiling of grade 3 invasive ductal breast cancers. Clin Cancer Res 2009; 15: 2711–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marchio C, Natrajan R, Shiu KK, et al. The genomic profile of HER2-amplified breast cancers: the influence of ER status. J Pathol 2008; 216: 399–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arriola E, Marchio C, Tan DS, et al. Genomic analysis of the HER2/TOP2A amplicon in breast cancer and breast cancer cell lines. Lab Invest 2008; 88: 491–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chin SF, Teschendorff AE, Marioni JC, et al. High-resolution aCGH and expression profiling identifies a novel genomic subtype of ER negative breast cancer. Genome Biol 2007; 8: R215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yao J, Weremowicz S, Feng B, et al. Combined cDNA array comparative genomic hybridization and serial analysis of gene expression analysis of breast tumor progression. Cancer Res 2006; 66: 4065–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haverty PM, Fridlyand J, Li L, et al. High-resolution genomic and expression analyses of copy number alterations in breast tumors. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2008; 47: 530–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Curtis C, Shah SP, Chin SF, et al. The genomic and transcriptomic architecture of 2,000 breast tumours reveals novel subgroups. Nature 2012; 486: 346–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Natrajan R, Weigelt B, Mackay A, et al. An integrative genomic and transcriptomic analysis reveals molecular pathways and networks regulated by copy number aberrations in basal-like, HER2 and luminal cancers. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2010; 121: 575–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chin K, DeVries S, Fridlyand J, et al. Genomic and transcriptional aberrations linked to breast cancer pathophysiologies. Cancer Cell 2006; 10: 529–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hicks J, Krasnitz A, Lakshmi B, et al. Novel patterns of genome rearrangement and their association with survival in breast cancer. Genome Res 2006; 16: 1465–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Osman C, Merkwith C, Langer T. Prohibitins and the functional compartmentalization of mitochondrial membranes. J Cell Science 2009; 122: 3823–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rajalingam K, Rudel T. Ras-Raf signaling needs prohibitin. Cell Cycle 2005; 4: 1503–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rajalingam K, Wunder C, Brinkmann V, et al. Prohibitin is required for Ras-induced Raf-MEK-ERK activation and epithelial cell migration. Nat Cell Biol 2005; 7: 837–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chiu CF, Ho MY, Peng JM, et al. Raf activation by Ras and promotion of cellular metastasis require phosphorylation of prohibitin in the raft domain of the plasma membrane. Oncogene 2013; 32: 777–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Webster LR, Lee SF, Ringland C, et al. Poor-prognosis estrogen receptorpositive breast cancer identified by histopathologic subclassification. Clin Cancer Res 2008; 14: 6625–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jonsson G, Staaf J, Olsson E, et al. High-resolution genomic profiles of breast cancer cell lines assessed by tiling BAC array comparative genomic hybridization. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2007; 46: 543–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manjeshwar S, Branam DE, Lerner MR, et al. Tumor suppression by the Prohibitin gene 3’ untranslated region RNA in human breast cancer. Cancer Res 2003; 63: 5251–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spurdle AB, Hopper JL, Chen X, et al. Prohibitin 3’ untranslated region polymorphism and breast cancer risk in Australian women. Lancet 2002; 360: 925–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Campbell IG, Allen J, Eccles AM. Prohibitin 3’ untranslated region polymorphism and breast cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2003; 12: 1273–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jakubowska A, Jaworska K, Cybulski C, et al. Do BRCA1 modifiers also affect the risk of breast cancer in non-carriers? Eur J Cancer 2009; 45: 837–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jakubowska A, Rozkrut D, Antoniou A, et al. Association of PHB 1630 C>Tand MTHFR 677 C>T polymorphisms with breast and ovarian cancer risk in BRCA1/2 mutation carriers: results from a multicenter study. Br J Cancer 2012; 106: 2016–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coates PJ, Nenutil R, McGregor A, et al. Mammalian prohibitin proteins respond to mitochondrial stress and decrease during cellular senescence. Exp Cell Res 2001; 265: 262–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.He Q, Zhang SQ, Chu YL, et al. Separation and identification of differentially expressed nuclear matrix proteins in breast carcinoma forming. Acta Oncol 2010; 49: 76–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Artal-Sanz M, Tavernarakis N. Prohibitin and mitochondrial biology. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2009; 20: 394–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Patel N, Chatterjee SK, Vrbanac V, et al. Rescue of paclitaxel sensitivity by repression of Prohibitin1 in drug-resistant cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2010; 107: 2503–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gregory-Bass RC, Olatinwo M, Xu W, et al. Prohibitin silencing reverses stabilization of mitochondrial integrity and chemoresistance in ovarian cancer cells by increasing their sensitivity to apoptosis. Int J Cancer 2008; 122: 1923–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sievers C, Billig G, Gottschalk K, et al. Prohibitins are required for cancer cell proliferation and adhesion. PLoS One 2010; 5: e12735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.He B, Feng Q, Mukherjee A, et al. A repressive role for prohibitin in estrogen signaling. Mol Endocrinol 2008; 22: 344–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lambros MB, Natrajan R, Geyer FC, et al. PPM1D gene amplification and overexpression in breast cancer: a qRT-PCR and chromogenic in situ hybridization study. Mod Pathol 2010; 23: 1334–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nijtmans LG, Artal SM, Grivell LA, et al. The mitochondrial PHB complex: roles in mitochondrial respiratory complex assembly, ageing and degenerative disease. Cell Mol Life Sci 2002; 59: 143–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alles MC, Gardiner-Garden M, Nott DJ, et al. Meta-analysis and gene set enrichment relative to ER status reveal elevated activity of MYC and E2F in the ‘basal’ breast cancer subgroup. PLoS One 2009; 4: e4710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chandriani S, Frengen E, Cowling VH, et al. A core MYC gene expression signature is prominent in basal-like breast cancer but only partially overlaps the core serum response. PLoS One 2009; 4: e6693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rodriguez-Pinilla SM, Jones RL, Lambros MB, et al. MYC amplification in breast cancer: a chromogenic in situ hybridisation study. J Clin Pathol 2007; 60: 1017–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]