Abstract

Aging in place (AIP) is a term that is commonly used and defined in a plethora of ways. Multiple disciplines take a different stance on the definition of AIP, and its definition has evolved over time. Such diverse ways to define AIP could be a barrier to reach a shared expectation among multiple stakeholders when formulating research studies, making policy decisions, developing care plans, or designing technology tools to support older adults. We conducted a scoping review for the term AIP to understand specifically how it has been defined across time and disciplines. We collected exemplary definitions of AIP from 7 databases that represent different fields of study; namely, AgeLine, Anthropology Plus, Art and Architecture Source, CINAHL, PsycINFO, PubMed, and SocINDEX. We conducted a thematic analysis to identify the common concepts that emerged across the definitions identified in the scoping review. We developed 3 main categories from the themes: space, person, and time to illustrate the root of meaning across the definitions. Intersectionality across the categories yielded a comprehensive understanding of AIP, which does not constrain its definition to a place-related phenomenon. We propose that AIP be defined as “One’s journey to maintain independence in one’s place of residence as well as to participate in one’s community.” With this shared understanding of the term AIP, policymakers, researchers, technology designers, and caregivers can better support those who aim to age in the place of their choice.

Keywords: Design, Environment, Older adults, Public policy, Residences, Scoping review

Translational Significance: The term “aging in place” is used widely but not defined consistently across disciplines or contexts. We reviewed the use of the term in research contexts to develop a shared definition inclusive of space, person, and time. Our interdisciplinary review revealed the importance of considering the intersectionality of these components. A broader, consistent definition of aging in place can guide interdisciplinary research and design collaborations between environmental gerontology and other related fields. A shared understanding will expand future design programs, tools, technologies, services, and policies to support aging in place.

A well-known and clearly documented phenomenon is the aging of the world population (World Health Organization, 2018). There are more people older than the age of 60 than ever before and the trend is continuing. Where do most older of these older adults live? The idea that people want to remain in their own original home may seem obvious on the surface, but is it really true for everyone? Older people in their 60s and 70s may move to downsize, move to a different climate, an over-55 community, to be nearer to family, or to invest in a continuing care retirement community. On theme of these moves is choice—older adults today have many options about where to live as they grow older. In other cases, the older person may have to move due to illness or injury, finances, physical limitations, or cognitive challenges. The motivations may differ, but there are options for the person to consider and to choose from.

The term “aging in place (AIP)” is used widely in research articles, public policy documents, government information websites, commercial advertisements, business names, and more. However, it is not always clear what the intended meaning is in these different contexts, or even if the term is being interpreted similarly for the different usages.

Most commonly, the intention appears to be that older adults want to remain in their own—sometimes long-time or original—homes as they age. For example, Beidler and Bourbonniere (1999, pp. 34–35) defined AIP as a term that is “used in long-term care discussions to describe the desire of older people to remain at home,” whereas Bigby (2008, p. 77) focused on AIP as the enabler for people to “remain in familiar surroundings, close to family and friends, to retain personal belongings, and avoid institutionalization.” These two definitions favored the home as the setting for AIP to follow older adults’ desire to stay in their familiar environment with their family and friends. However, these definitions did not take into account older adults’ ability to maintain their independence in conducting their everyday activities. As people age, they experience cognitive and functional capacity changes that may interfere with their ability to stay in their current environment. As evidenced by the person–environment fit theory (Lawton & Nahemow, 1973), it is important to consider the personal capacity to provide sufficient environmental support for successful adaptation in old age. The experience of living in a familiar environment may not be enough if individuals’ ability to successfully engage with their activities of daily living is sacrificed. This perspective may be overly constraining, which might result in negative connotations and limit opportunities for older adults (Weil & Smith, 2016).The term AIP gets used a short hand and how individuals, families, communities, and societies think about where older adults should want to live. But words matter. Assuming that all older adults want to remain in their current living situation for the foreseeable future is limiting. Moreover, forgetting that people who do not live in traditional homes still need environmental supports that enhance their quality of life does them a disservice.

When specific AIP definitions are provided, they vary widely. To illustrate:

“This aging-in-place philosophy means residents will have to relocate to a new settings less often.” (Chapin & Dobbs-Kepper, 2001, p. 43)

“Implicit in the current ‘aging in place’ movement is the assumption that people develop an attachment, affinity, or familiarity for a place, and maintaining this connection to home and environment is adaptive.” (Kovach, 1998, p. 33)

“The concrete strategy of ‘ageing in place’ is to provide the elderly and the disabled with care services in their own community.” (Chen, 2008, p. 183)

“The term “aging-in-place” denotes the process of cohort transition to increasing age and residential inertia.” (Graff & Wiseman, 1978, p. 382)

“The demographic processes involved in the numerical growth or decline of the elderly population over a fixed time period include both net migration and natural increase.” (Lichter et al., 1981, p. 481)

“… aging-in-place is not only a demographic or political issue, but is also an emotional and lived experience that inherently involves the broader place or residence.” (Coleman & Kearns, 2015, p. 206)

These examples exemplify the range of concepts included in AIP definitions as well as the goals for using the term. Sometimes the definition assumes intentions on the part of older individuals; other times it provides guidance for measurement and defines a scope of research.

As researchers, it is crucially important to define the terms that guide our paths of inquiry. Based on the review of common concepts and constructs that are associated with AIP, Weil and Smith (2016) suggested the reevaluation of the AIP concept to highlight and to incorporate a wider diversity in its definition beyond the matter of “place.” Moreover, as was clear from Weil and Smith’s (2016) examples, AIP has been used ambiguously with limited empirical support. Our goal in this project was to understand how AIP has been defined—and hence explored in the research literature. We conducted a scoping review to trace AIP definitions over time and across disciplines to understand the parameters of use, themes, distinctions, and trends. Ultimately, we wanted to broaden the utility of the term to encompass the needs and preferences of older adults.

Research Design and Method

The purpose of a scoping review is to “map” the evidence to convey a summary that captures the breadth and depth of a field (Levac et al., 2010). To understand the changing AIP meaning and context of use, we searched multiple databases for evidence of the AIP concept, definition, and development in different fields of study. We selected a comprehensive set of disciplines that would be most likely to investigate concepts related to AIP: social, medical, behavioral, gerontological, and architectural.

Data Collection

Literature screening was the initial step to collect various definitions of AIP. We conducted the search in seven databases to represent multiple disciplines: medicine, psychology, nursing, gerontology, sociology, anthropology, and architecture. These databases were recommended by the university librarian as the best avenue to gather articles that are representative of the disciplines we had selected. The list of databases with a short content description is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Databases Included in the Scoping Review

| Database | Description | Relevance scoring method |

|---|---|---|

| AgeLine | Focuses on the population aged 50 years and older/gerontology. Also covers topics of health sciences, psychology, sociology, social work, economics, and public health, as well as issues in aging from the individual, national, and global perspectives. Contains journals, books, and reports. | - The order of influential search fields (maximizing accuracy with field ranking) - Mapping vocabulary terms from multiple sources/fields and users natural language (enhanced subject position) - Prioritizing newly published and peer-reviewed articles over older and non-peer-reviewed articles (value ranking) - Concentrating on documents with phrase than contains words in isolation (adjacency bias) - Applying normalization scoring model to prevent inflation of high-frequency hits on matching words in the full-text documents - An article can receive a “field match boost” if the search query exactly matches the title field of the library catalog records |

| Anthropology Plus | Includes journal articles, reports, commentaries, edited works, and obituaries and covers anthropology, archeology, art history, demography, and economics. | - Same as AgeLine |

| Art and Architecture Source | Includes journals, books, international periodicals, art reproduction records, and abstracts for journals, magazines, and trade publications. Covers fine, decorative, and commercial art, as well as architecture and design. Also covers art history, archeology, architecture history, advertising art, and antiques. | - Same as AgeLine |

| CINAHL | Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL). Journal articles pertaining to health care, nursing, biomedicine, and allied health. | - Same as AgeLine |

| PsycINFO | Database of abstracts from the field of psychology. Produced by the American Psychological Association (APA). Contains journal articles, books, and dissertations dating back to the 19th century. | - The matched of distinct or individual words across the documents, unless the search is limited to exact terms by quotes (exact term vs. individual word) - The frequency of search terms contained in the documents (term frequency) - The frequency of less common terms used compared to terms that are commonly found (inverse document frequency) - The appearance of search terms in different fields is weighed differently (metadata field weighting) - The usage of special characters (i.e., *) will not affect the relevance scoring (truncation) |

| PubMed | Primarily accesses information from the Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online (MEDLINE). Includes journals, references, and abstracts on biomedical and life science topics. | - The number of search terms found in the fields - The location of the fields that the search terms are found - The articles that are recently published is weighed higher - Articles identified using the criteria above, then re-ranked using a different machine learning algorithm |

| SocINDEX | Journals and abstracts covering sociology topics including criminology, criminal justice, demography, ethnic and racial studies, and gender studies. | -Same as AgeLine |

Notes: Database descriptions were adapted from the database websites. Relevance scoring methods determined from EBSCOConnect, 2020; Fiorini et al., 2018; National Library of Medicine, 2020; ProQuest Support Center, 2020.

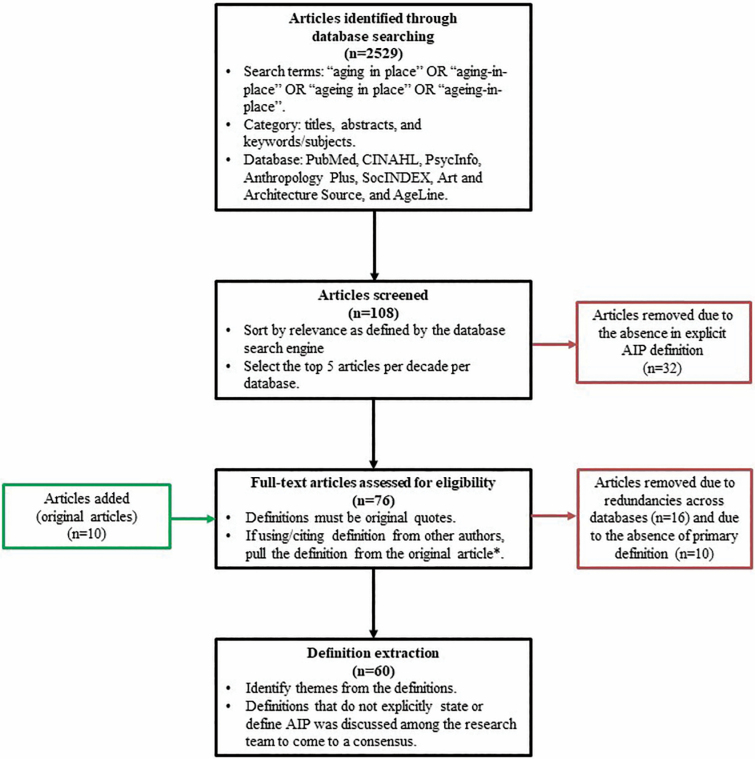

The data were collected from June to December 2019. We used the search terms “aging in place,” “aging-in-place,” “ageing in place,” and “ageing-in-place” under titles, abstracts, keywords, and subject category in every database during the initial literature screening. Articles other than research articles, books, and book sections that appeared on the search were excluded from the pool. The process of article search and screening is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of article search and inclusion criteria.

We identified 2,529 items through the initial screening of seven databases. To make a detailed review of the definitions feasible, we selected a subset of the articles that were most relevant to our goals. We thus conducted a separate search for each decade: before the 1960s, 1960–1969, 1970–1979, 1980–1989, 1990–1999, 2000–2009, and 2010–2019 to differentiate the number of items that were published in each decade. Then, we sorted the search results using the “sort by relevance” feature of the database for each decade to select the top five articles in a specific time period. Some of the databases only had a few (i.e., less than 2) articles for some decades, whereas other databases had many articles (i.e., more than 50) in a decade. We decided to select the top five relevant articles to have a relatively balanced number of articles that are most relevant as determined by the database. The detail of relevance scoring method in each database is explained in Table 1.There were 108 articles after the secondary screening. We reviewed the full text from this pool for specific AIP definitions. We excluded 32 articles that did not have an explicit AIP definition in the body of text; note that this represents 30% of articles that used the term without explicitly defining it, assuming it must be self-explanatory. There were 76 articles remaining to be assessed for eligibility with the criterion that the definition included in the article must be the original citation for that definition. Ten articles that used or cited definitions from other articles were replaced with the original article from which it cited the AIP definition. Some items appeared in multiple databases. Following the redundancy check, we removed 12 articles that showed up more than once and only retained the ones that appeared in the earlier database search. The order of the search was alphabetical: AgeLine, Anthropology Plus, Art and Architecture Source, CINAHL, PubMed, PsycINFO, and SocINDEX. After this entire process, we were left with 60 article definitions to analyze thematically.

Two research team members extracted the AIP definitions from the 60 articles. One researcher extracted definitions from CINAHL, PsycINFO, and PubMed, whereas the other researcher extracted the definitions from AgeLine, Anthropology Plus, Art and Architecture Source, and SocINDEX. The definitions were copied and combined in a matrix. Once the definition extraction was completed, thematic analysis was conducted separately by two researchers. Each researcher coded the definitions separately to find themes that emerged from the data. Subsequently, the researchers met to discuss the themes and the words used to explain them. If necessary, similar themes were reworded to ensure that every team member was using similar wording. When there was a disagreement on themes, the team discussed to reach an agreement on the code definition. From this process, we created a database that had the theme definitions and similar words or phrases that would fall under the same codes. This thematic analysis was done iteratively until a comprehensive and well-defined coding scheme was constructed, and all the definitions were coded using the latest version of coding schemes.

Once the themes were finalized, the research team grouped them subjectively into higher-level categories of space, person, and time (Table 2). Themes that concerned the place-related issue were grouped into the “space” category. Themes related to the personal capacity, preference, and relations were classified under the “person” category. Lastly, themes related to periodical moments were combined under the “time” category. A single definition could be coded with multiple codes if it is related to more than one category. Some definitions had only space or person-related themes in the definitions, whereas others had multiple categories represented in the AIP definition. After grouping the themes, the team then counted how many times each category appeared throughout the definitions. Counting the category appearance among AIP definitions was the foundation to understand how AIP has been defined and changed over time. The results of the thematic analysis were then analyzed to synthesize the history and utilization of the AIP terminology across disciplines.

Table 2.

Coding Scheme of Themes Identified From the Aging in Place Definitions

| Space | Person | Time |

|---|---|---|

|

Accessibility Aging of residential setting Assisted living Community Familiar settings Home Home modifications Living environment Migration Moving Staying |

Adaptation Cost Emotional attachment Health conditions Maintaining independence Preference Social participation |

Length of residence Life span Process |

Results

Trends Over Time

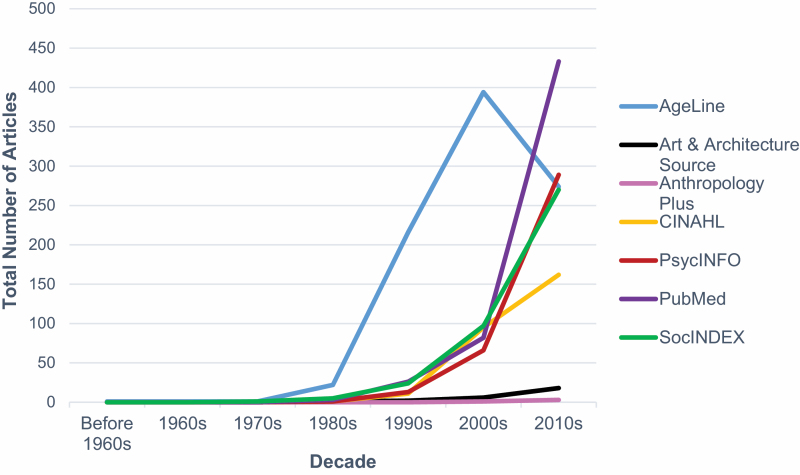

In general, the number of articles related to AIP has increased over time. Figure 2 shows the distribution of the 2,529 articles that mentioned AIP in titles, abstracts, or keywords. AgeLine had the earliest AIP-related articles starting from the 1970s. However, between the 2000s and 2010s, we found a decreasing number of articles in AgeLine. Interestingly, the rest of the databases showed an increasing trend around that period. This contradiction is shown clearly in Figure 2. Due to this noticeable difference, we explored the reasoning behind the AgeLine anomaly. We assessed whether (a) there were fewer journals included in the AgeLine database, or if (b) AgeLine database was inactive in the 2010s period. However, these ideas could not be confirmed. The other alternative explanation of this finding was that, although AgeLine is a database for age-specific topics, there may have been a shift of publication channels as more multidisciplinary research on aging emerged. Aging-related studies that had previously been published in journals under AgeLine may have instead been published in other discipline-specific databases. This argument was supported by our findings that between the 2000s and 2010s, the other databases showed a notable gain of AIP articles. We expected that the trend of increasing AIP-related articles will continue to escalate as more researchers are concerned about the AIP phenomenon.

Figure 2.

Frequency of articles with the term “aging in place” across decades and databases.

Definitions of AIP changed over time across the seven different databases. As the term evolved over the years, the frequency of it being discussed in articles increased over time, starting as early as 1970 to 2019. The earliest definition by Graff and Wiseman (1978, p. 383) stated, “Aging-in-place associated with the selective out-migration of younger cohorts appears to be the dominant factor accounting for most of the large increases in the county percentages of elderly persons between 1950 and 1970.” Although other definitions were not found in this decade, Graff and Wiseman set the stage for subsequent definitions by focusing on the increasing number of older adults.

Early articles in the 1980s mentioned the term AIP but predominately focused on understanding not moving and staying put (Blackie, 1986). Ryther (1987) and Rudzitis (1982) shared a similar idea of staying in the same place of residence in the old age. This early notion of AIP was rooted in the acknowledgment of connection that was built upon people’s experience in their living environment over time.

The term AIP was more common in the literature of the 1990s. Although various articles agreed on the significance of aging in a familiar environment, the type of living environment was only vaguely described. For example, Gilson and Netting (1997, p. 290) stated, “It implies the aging of people within familiar environments and the accompanying changes that occur as they become older. It implies the physical aging of the home, the neighborhood, and the larger community, all of which are nested within one another.”

The literature in the 2000s had more varied definitions of AIP, focusing on services and policies (Mitty & Flores, 2008; Tang & Pickard, 2008), choice (Wagnild, 2001), and independence (Sixsmith & Sixsmith, 2008). Some still focused on the importance of place and familiar environment, especially the home, neighborhood, and the community where older adults built their physical, emotional, and social connection throughout their life. In other words, “People are enabled to remain in familiar surroundings, close to family and friends, to retain personal belongings, and avoid institutionalization” (Bigby, 2008, p. 77). As this term went to a new decade, the meaning was further transformed.

The highest number of articles that included the concept of AIP was found in the 2010s. The core definition focused on the sense of identity and ties to the home as well as the community (Wiles et al., 2011). An example that encompassed this was by Gammonley et al. (2019, p. 498), “The problem is that this strong desire to age in place in one’s current and preferred home or even in another independent setting, is very often not enough. Community support and access to resources help enhance successful aging in place by providing practical service assistance as well as addressing isolation and loneliness.” This exemplified how space and person are combined to develop a useful definition of AIP. It also illustrated themes that have appeared in other decades, such as familiar settings and services.

Trends Across Disciplines

Figure 2 portrays the trend of AIP-related publications across the databases. The majority of the databases began to publish AIP-related articles in the 1980s, and it gradually increased throughout the decades. AgeLine led the total number of publications, yet showed a decrease in the number of publications in the 2010s, whereas the rest of the databases showed an increase in the number of publications in the same decade. AIP-related publications in PubMed steadily increased with a steep increment around the 2000s. Similarly, PsycInfo, CINAHL, and SocINDEX also experienced a rise in the number of AIP-related publications in the 2000s. On the lower end are Art and Architecture Source and Anthropology Plus that showed a rather slower growth compared to the rest of the databases. In the latest decade, PubMed had the highest count of articles, followed by AgeLine, PsycINFO, and SocINDEX in the upper-middle range, then CINAHL on the lower-middle range, and lastly Art and Architecture Source and Anthropology Plus had the least. From Figure 2, we can see the large gap in the number of AIP-related publications in different databases, which represent opportunities for researchers and policymakers to explore AIP within their respective disciplines.

General Themes

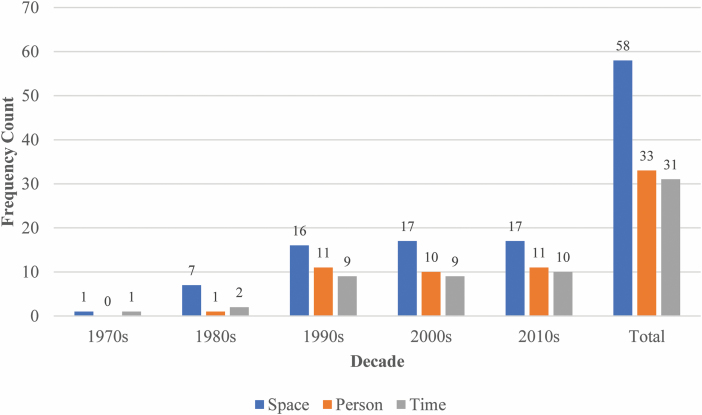

Through the thematic analysis of the 60 article definitions, we identified three thematic categories: space, person, and time (Table 2). The most terms related to the category of space, such as the type of housing (home and assisted living), aspects of the structure itself (accessibility, modifications, and aging of the setting itself), and activities in the space (moving, staying, and migrations). Definitions codes relating to the person included ideas about what an individual was doing (e.g., adapting), their characteristics (e.g., health), as well as their goals and preferences. Concepts related to time were the length of time in residence, life span, or process over time.

Figure 3 illustrates the number of times a code was assigned to an excerpt of definition. One excerpt could be assigned multiple codes, hence illustrating the intersectionality of space, person, or time in the definition. This diagram illustrates the number of times a code is assigned to an excerpt of definition. Space had the highest count compared to the other categories in every decade, indicating that the concept of space was consistently at the core of AIP definitions over time. In general, AIP definitions across literature focused more on the space-related themes, such as the accessibility and familiarity, the place of residence (home and assisted living), the act of choosing the place (staying, moving, and migrating), and the relation with the community who shared the space living environment with older adults. Despite a substantial amount of space-related definitions in the earlier literature, the themes of person and time also grew over time. In the last decade, definitions included considerations of the person and time. This finding suggests that recent literature defined AIP more inclusively beyond just space, supporting the idea that AIP is not limited to one’s location.

Figure 3.

The frequency of space, person, and time categories (total n = 122) assigned to each definition across the decades.

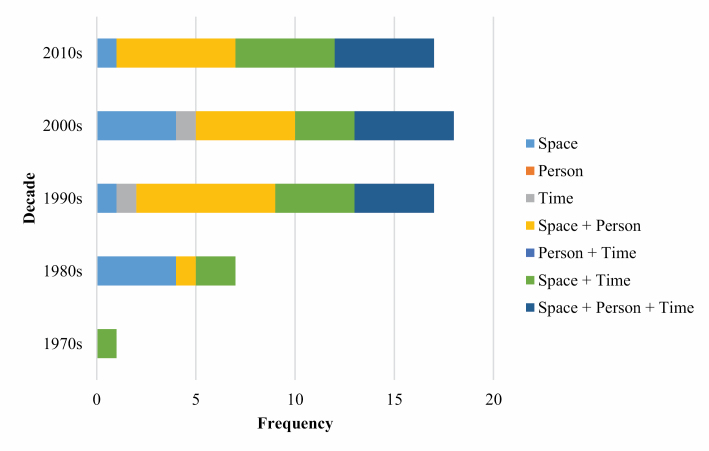

Beyond the individual category, we observed intersectionality between two or more categories in one definition. Intersectionality refers to the overlapping of more than one aspect of space, person, and time in a definition. The purpose of focusing on the intersectionality of these categories is to illustrate the interconnected nature of the space, person, and time aspects in the experience of AIP. Figure 4 portrays the trend of space, person, time, or the intersectionality that were contained in the definition excerpts from the articles across the decades. We observed that the intersectionalities between two or three categories were more commonly used among the definitions in the more recent literature (2010s).

Figure 4.

Trend and frequency of space, person, time, or the intersectionality in the definition excerpts from all of the articles (n = 60).

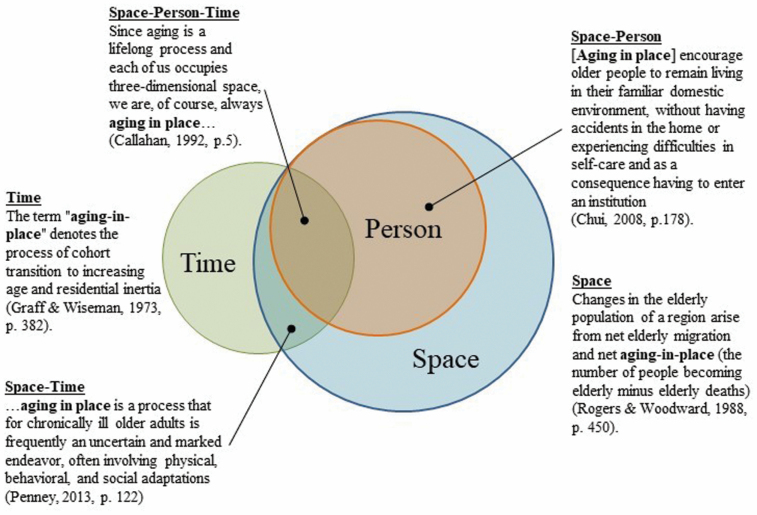

Figure 5 illustrates the intersectionality between space, person, and time along with the exemplary definitions that were coded in the categories. The size of the circle represents the proportion of definitions tied to the category. Space was the most discussed theme in all the definitions found, followed by person, and then by time. We found intersectionality in space–time and space–person, but there was not any definition that had the intersectionality of person–time. All the definitions that were coded under the person category were also coded under space, as illustrated in Figure 5 where the “Person” circle is completely encompassed within the “Space” circle. The portion of the figure where all the three circles overlapped with each other indicates that some definitions contained themes from all the categories.

Figure 5.

Space–person–time exemplary definitions. The size of each circle maps to the frequency of articles shown in Figure 2.

Beyond illustrating the proportion and intersectionality across categories, Figure 5 also shows some examples of definitions. Some definitions were coded under just one category. For instance, Rogers and Woodward’s (1988) definition was coded under the “Space” category. They looked at the AIP phenomenon from the migration perspective, hence focusing solely on individuals’ residential locations to classify whether someone was AIP or not. Graff and Wiseman’s (1978, p. 382) definition was primarily about time, with AIP as the “process of cohort transition to increasing age and residential inertia.” Their definition focused more on the time aspect of AIP, both the aging process of the individual and the setting.

Furthermore, there were definitions coded under two categories. For instance, Chui (2008, p. 178) viewed AIP to “encourage older people to remain living in their familiar domestic environment, without having accidents in the home or experiencing difficulties in self-care …,” which focused on both the person and space aspects. Another example was a definition by Penney (2013) wherein AIP was the process of frequent physical, behavioral, as well as social adaptations among older adults, which illustrated the intersectionality of space and time categories.

Lastly, several definitions touched all three categories, for instance, a definition by Callahan (1992, p. 5), “Since aging is a lifelong process and each of us occupies three-dimensional space, we are, of course, always aging in place ….” This definition evenly acknowledged all three categories: related to the person, the living space, and that the process takes time across the life span. Other examples included Lawlor and Thomas (2008, p. 1): “The concept of residential design for aging in place is simple: Create houses and homes [space] that adapt to an elder population [person], segments of the society who are or will begin to endure the aging process [time].” Another example is by Torkildsby (2018, p. 6), who stated “Moreover, an ageing population [person] is need of (housing) [space] design that facilitates long-term [time] accessibility and hence homeowners ‘ageing in place’ safely without losing their independence.”

In summary, the definitions we reviewed revealed three main concepts: space (the setting), person (the individual), and time (the process throughout the life span). Although space was more frequently mentioned across the years, definitions that specifically incorporated the person and time also increased over the decades.

Discussion: Redefining Aging in Place

As we enter a new decade and we see the growth of the term AIP, there are newer terms that are emerging with the aim of becoming more encompassing. Two of these terms are “aging in the community” and “aging in the right place.”

Aging in the community emerged to be part of the discussion as a “grassroots movement of like-minded citizens who come together to create systems of mutual support and caring to enhance their well-being, improve their quality of life, and maximize their ability to remain, as they age, in their homes and communities” (Blanchard, 2013, p. 7). This concept is presumed to be more open to various interpretations compared to AIP, with an emphasis on older adults’ needs for meaningful social contact. This social contact in the community provides support for access to resources and can prevent isolation and loneliness (Gammonley et al., 2019). Without meaningful social connection, older adults’ lives can be meaningless and purposeless (Blanchard, 2013).

Another idea proposed to replace the AIP concept came from Golant (2015), who proposed “aging in the right place” that does not limit the option only to remain living in an older adult’s own home and community. Vanleerberghe et al. (2017, p. 2900) stated that “Aging in place used to refer to individuals growing old in their own homes, but lately the idea has broadened to remaining in the current community and living residence of one’s choice.” Therefore, when older adults need continuous assistance, relocation to residential care can be accepted and will not be perceived negatively. If AIP in older adults’ homes is no longer desirable or relevant, they must look for the other living options so that they can receive care assistance (Golant, 2015). Nevertheless, they will continue to aging in that place.

Expanding to a more comprehensive terminology, including aging in the community and aging in the right place, may enhance ways to support those who are aiming to age in place. Regardless of the name of the term, the three components (i.e., space, person, and time) should be considered when developing programs, tools, services, or policies.

The Administration for Community Living website (https://acl.gov/about-community-living) states that “All people, regardless of age or disability, should be able to live independently and participate fully in their communities.” That is the essence of AIP—it does not have to mean remaining in the same residence throughout old age. The goal is to provide continuity, and as Atchley (1989, p. 183) described it, “Continuity Theory assumes evolution, not homeostasis, and this assumption allows change to be integrated into one’s prior history without necessarily causing upheaval or disequilibrium.”

AIP should be a holistic concept that incorporates the demands and supports of the place; the needs and characteristics of the person; and the fact that aging is a process, and adjustments (e.g., residential relocation) may actually enhance the AIP experience for individuals. We need to broaden and specify the definition of AIP to move beyond overly constrained definitions or casual use of the term. A common, holistic definition can guide policy, technology intervention design, and research across disciplines.

The AIP literature will likely continue to grow across disciplines as the term becomes more popular, new terms are introduced, and varying definitions are developed. Therefore, it is important that we have a common unifying definition. We recommend that AIP be defined as “One’s journey to maintain independence in one’s place of residence as well as to participate in one’s community.” The “journey” component reflects that a person’s situation changes over time as they are aging; that is, AIP is a process. The aspects of “maintain independence” and “participate” reflect the broad goals of the person that are independent of the space. The space aspect is represented by both “place of residence” and “community,” as the sense of community is a key component of AIP.

Focusing on the individual’s agency to choose is key to ensuring that they can retain their autonomy. AIP concerns the individual’s process of adaptation that allows unlimited possibilities for residential places. We present this updated definition to focus on matching one’s personal capabilities to their environmental demands (Lawton & Nahemow, 1973). Our definition is not limited to a specific type of housing due to the increasingly unrealistic assumption that people will stay in one place for their entire life as their health, needs, and goals change. A definition that encompasses space, person, and time might better guide the design of interventions, technologies, and policies that are inclusive to researchers, designers, and policymakers from different fields.

Funding

The contents of this article were developed under a grant from the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR grant number 90REGE0006-01-00) under the auspices of the Rehabilitation and Engineering Research Center on Technologies to Support Aging-in-Place for People with Long-Term Disabilities (TechSAge; www.rerctechsage.org). NIDILRR is a Center within the Administration for Community Living (ACL), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The contents of this article do not necessarily represent the policy of NIDILRR, ACL, or HHS, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

References

- Atchley R C. (1989). A continuity theory of normal aging. The Gerontologist, 29(2), 183–190. doi: 10.1093/geront/29.2.183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beidler S M, & Bourbonniere M (1999). Aging in place: A proposal for rural community-based care for frail elders. Nurse Practitioner Forum, 10(1), 33–38. PMID: 10542579 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigby C. (2008). Beset by obstacles: A review of Australian policy development to support ageing in place for people with intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 33(1), 76–86. doi: 10.1080/13668250701852433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackie N K. (1986). The option of “Staying Put.” In Gutman G M & Blackie N K (Eds.), Aging in place: Housing adaptations and options for remaining in the community (pp. 1–12). The Gerontology Research Centre Simon Fraser University. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard J M. (2013). Aging in community: The communitarian alternative to aging in place, alone. Journal of the American Society on Aging, 37(4), 6–13. [Google Scholar]

- Callahan J J. (1992). Aging in place. Generations, 16(2), 5–6. [Google Scholar]

- Chapin R, & Dobbs-Kepper D (2001). Aging in place in assisted living: philosophy versus policy. The Gerontologist, 41(1), 43–50. doi: 10.1093/geront/41.1.43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y-J. (2008). Strength perspective: An analysis of ageing in place care model in taiwan based on traditional filial piety. Ageing International, 32(3), 183–204. doi: 10.1007/s12126-008-9018-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chui E. (2008). Ageing in place in Hong Kong—Challenges and opportunities in a capitalist Chinese city. Ageing International, 32(3), 167–182. doi: 10.1007/s12126-008-9015-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman T, & Kearns R (2015). The role of bluespaces in experiencing place, aging and wellbeing: Insights from Waiheke Island, New Zealand. Health & Place, 35, 206–217. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2014.09.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EBSCOConnect (2020, January 13). How is relevance ranking determined in EBSCOhost? https://connect.ebsco.com/s/article/How-is-relevance-ranking-determined-in-EBSCOhost?language=en_US

- Fiorini N, Canese K, Starchenko G, Kireev E, Kim W, Miller V, Osipov M, Kholodov M, Ismagilov R, Mohan S, Ostell J, & Lu Z (2018). Best match: New relevance search for PubMed. PLoS Biology, 16(8), e2005343. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.2005343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gammonley D, Kelly A, & Purdie R (2019). Anticipated engagement in a village organization for aging in place. Journal of Social Service Research, 45(4), 498–506. doi: 10.1080/01488376.2018.1481169 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gilson S F, & Netting F E (1997). When people with pre-existing disabilities age in place: Implications for social work practice. Health & Social Work, 22(4), 290–298. doi: 10.1093/hsw/22.4.290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golant S M. (2015). Aging in the right place. Health Professions Press. [Google Scholar]

- Graff T O, & Wiseman R F (1978). Changing concentrations of older Americans. Geographical Review, 68(4), 379. doi: 10.2307/214213 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kovach C R. (1998). Nursing home dementia care units. Providing a continuum of care rather than aging in place. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 24(4), 30–36. doi: 10.3928/0098-9134-19980401-09 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawlor D, & Thomas M A (2008). Residential design for aging in place. Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Lawton M P, & Nahemow L (1973). Ecology and the aging process. In C. Eisdorfer & M. P. Lawton (Eds.), The psychology of adult development and aging (p. 619–674). American Psychological Association. doi: 10.1037/10044-020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Levac D, Colquhoun H, & O’Brien K K (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5, 69. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichter D T, Fuguitt G V, Heaton T B, & Clifford W B (1981). Components of change in the residential concentration of the elderly population: 1950–1975. Journal of Gerontology, 36(4), 480–489. doi: 10.1093/geronj/36.4.480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitty E, & Flores S (2008). Aging in place and negotiated risk agreements. Geriatric Nursing (New York, N.Y.), 29(2), 94–101. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2008.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Library of Medicine (2020, June 16). PubMed user guide https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/help/ [DOI] [PubMed]

- Penney L. (2013). The uncertain bodies and spaces of aging in place. Anthropology and Aging Quarterly, 34(3), 113–125. doi: 10.5195/aa.2013.12 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- ProQuest Support Center. (2020, January 8). ProQuest search results—Relevance ranking https://support.proquest.com/articledetail?id=kA11W000000GzP4SAK&key=relevance&pcat=All__c&icat=

- Rogers A, & Woodward J (1988). The sources of regional elderly population growth: Migration and aging-in-place. Professional Geographer, 40(4), 450–459. doi: 10.1111/j.0033-0124.1988.00450.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rudzitis G. (1982). Residential location determinants of the older population. University of Chicago, Department of Geography; http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=gnh&AN=72685 [Google Scholar]

- Ryther B. (1987). Aging in place: Training for managers. The Council of State Housing Agencies and the National Association of the State Units on Aging. [Google Scholar]

- Sixsmith A, & Sixsmith J (2008). Ageing in place in the United Kingdom. Ageing International, 32(3), 219–235. doi: 10.1007/s12126-008-9019-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tang F, & Pickard J G (2008). Aging in place or relocation: Perceived awareness of community-based long-term care and services. Journal of Housing for the Elderly, 22(4), 404–422. doi: 10.1080/02763890802458429 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Torkildsby A B. (2018). Critical design in universal design settings: Pedagogy turned upside down. Design and Technology Education, 23(2), 6–23. [Google Scholar]

- Vanleerberghe P, De Witte N, Claes C, Schalock R L, & Verté D (2017). The quality of life of older people aging in place: A literature review. Quality of Life Research, 26(11), 2899–2907. doi: 10.1007/s11136-017-1651-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagnild G. (2001). Growing old at home. Journal of Housing for the Elderly, 14(1–2), 71–84. doi: 10.1300/J081v14n01_04 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weil J, & Smith E (2016). Revaluating aging in place: From traditional definitions to the continuum of care. Working With Older People, 20(4), 223–230. doi: 10.1108/WWOP-08-2016-0020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wiles J L, Leibing A, Guberman N, Reeve J, & Allen R E (2011). The meaning of “aging in place” to older people. The Gerontologist, 52(3), 357–366. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnr098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2018, February 5). Ageing and health. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health