ABSTRACT

Background:

The etiological relationship between the plaque and the gingival inflammation has been long established. The long-term use of chemical antiplaque agents may lead to side effects such as teeth staining and alteration of taste. Therefore, natural plant extracts with potential antibacterial and anti-inflammatory activity have been explored, which are equally effective and safe for long-term use.

Objective:

The aim of this study was to compare and evaluate effect of neem gel and chlorhexidine (CHX) gel on dental plaque, gingivitis, and bacterial count of Streptococcus mutans and Lactobacilli among 20–30-year-old school teachers in a city of western Maharashtra, over 90 days’ usage.

Materials and Methods:

A double-blind, parallel armed, controlled, randomized clinical study was conducted among 60 school teachers of 20–30 years’ age group for 90 days. The two study groups were as follows: Group A––2.5% neem gel (n = 30) and Group B––0.2% CHX gel (n = 30). The plaque scores were recorded by Plaque Index (Löe H. The gingival index, the plaque index and the retention index systems. J Periodontol 1967;38:610-6) and gingival scores by Gingival Index (Löe H, Silness J. Periodontal disease in pregnancy. Acta Odontol Scand 1963;21:533-51). Streptococcus mutans and Lactobacilli species count by conventional culture method was carried out at baseline, 30th day and 90thday. Considering P value <0.05 as statistically significant, intergroup comparison was performed using unpaired t test. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test was used followed by Tukey’s post hoc test for intragroup comparison.

Results:

The mean plaque, gingival scores, and microbial count of S. mutans and Lactobacilli showed significant reduction at 30th and 90th day in neem gel group as well as CHX gel group (P < 0.05). None of the parameter showed any significant change at 30th and 90th day (P > 0.05) on intergroup comparison.

Conclusion:

The neem gel showed significant decrease in dental plaque, gingival inflammation, and microbial counts, which was comparable to CHX gel proving to be a good herbal alternative. No side effects were reported for use of neem gel over considered period of time.

KEYWORDS: Azadirachtaindica, chlorhexidine, dental plaque, gels, gingivitis, microbial count, neem

INTRODUCTION

It has been well established that oral health is an integral part of general health and well-being. Oral health and general health comorbidity is well established. Throughout the world, dental diseases contribute as major public health problem. Worldwide, dental caries affects 60%–90% children and approximately 100% adults.[1] Periodontal disease in its simplest form is chronic gingivitis,[2] and, regardless of age, sex, or race, affects more than 90% of the population.[3]

The etiology for dental caries and periodontal diseases is the supragingival and subgingival plaque.[4] Dental plaque is a biofilm, which is formed by the interaction between microbial deposits and salivary coating immersed in an extracellular polysaccharide matrix.[5] The most common bacteria responsible for plaque formation are Streptococcus mutans and Lactobacilli.[6] The most crucial factor in terms of preventive and curative treatment of dental diseases is therefore the removal of bacterial biofilm. The most feasible and cost-effective method for gingivitis control is use of mechanical agents.[7]

However, this mechanical plaque control has failed as effective control measure as proven by worldwide prevalence of gingivitis. It is difficult to achieve an “ideal” mechanical plaque control and this resulted in exploring chemical antimicrobial agents inhibiting biofilm formation.[8]

Although numerous chemical agents for plaque control have been tried over the years, all have shown some side effects. Thus, patients are more inclined toward herbal preparations, which are effective and do not cause any side effects. Hence, the search for unconventional product continues.

The neem tree has been deeply rooted in Indian culture.[9] The neem leaves are cheap and easily available as well as widely accepted socially in the Indian society. It has been tested for its antibacterial activity,[10,11,12,13] including its therapeutic use for gingivitis and periodontitis.[3,8,14,15]

In this study, attempts were made to prolong the contact time of therapeutic dosage of agent to allow sufficient time period of contact[16] and improve compliance by the virtue of sustained release drug-delivery system of bioadhesive nature without any side effects. Thus, there is need to study this indigenous agent in depth to establish its efficacy in gel form for the prevention of oral diseases. On extensive literature review, we were unable to find adequate studies conducted to assess effect of gel form of chemical plaque control agents. Hence, this study was conducted with an aim to evaluate and compare the effect of neem gel and chlorhexidine (CHX) gel on plaque, gingivitis, and the bacterial count of S. mutans and Lactobacilli during a period of 90 days use in a city of western Maharashtra, India.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of gel formulations

The gels were formulated with the help of pharmacology department of BioGreen Healthcare, Mulund, Mumbai, India––a commercial manufacturer of ayurvedic and herbal medicines. The aqueous liquid extract of Azadirachtaindica was prepared by boiling 20g of neem leaves in 1000 mL of water, which was reduced to 100g of neem extract. It was observed that the neem extracts showed a minimum inhibitory concentration at 25 µg/mL for S. mutans and Lactobacilli by in vitro testing. Hence, this concentration was used for the preparation of the neem gel. 20g of carbopol 934P was added in 1000 mL of water and soaked for 24h to prepare the base gel. To this base gel 2.5% neem extract and 0.2% CHX powder was added along with 0.06% peppermint oil and preservatives to prepare the respective gels. The gels were tested and found stable for 1 year. The gels had similar color and were packed in opaque collapsible tubes, which were labelled as gel A and gel B by pharmacologist for allocation concealment.

Sample size calculation

It was carried out according to the expected minimum reduction in dental plaque scores in control group, as observed in a previous study[16] along with consideration of 10% attrition, which was derived to be 30 in each group.

Recruitment, randomization, and clinical examination

Ethical approval from institutional ethical committee and informed consent from study participants in local language were obtained prior to start of this randomized parallel arm double-blind clinical trial. All the examinations and recording of the parameters were carried out by a single trained and calibrated examiner. After obtaining approval from school authorities to conduct study among school teachers, participants were evaluated for inclusion and exclusion criteria. Those with similar socioeconomic status, oral hygiene methods, having fair plaque score, and moderate gingivitis assessed by Plaque Index[17] and Gingival Index,[18] respectively, and no loss of attachment were included in study. Those with overhanging restorations, antibiotic therapy in last 3 months before commencing the study, using any dentifrice/mouthwash having anti-inflammatory action, presence of grossly decayed teeth, and any systemic disorders that require the use of medications with side effects known to affect oral health were excluded from the study.

A total of 60 participants were randomly allocated by lottery method into two groups of 30 each such that both groups had equal gender distribution. The two study groups were as follows:

Group A––2.5% neem gel (n = 30, men = women = 15 each)

Group B––0.2% CHX gel (n = 30, men = women = 15 each)

The preparatory phase for the study started from October 2014, which included preparation of test formulations, stability testing, obtaining permissions from schools, and screening for selection of study participants. The actual study period of clinical trial extended from July 14, 2015 to October 23, 2015. Type 3 clinical examination (classification by the American Dental Association 1970)[19] was followed throughout the study during intraoral examinations. The study participants were availed with their respective gels and instructions were given of its use as, twice daily––once in morning after consuming breakfast and at night just before sleeping. Approximately 1g of gel should be dispensed on index finger and applied thoroughly in the oral cavity. This was shown with the help of video. They were instructed that after gel application they were not supposed to eat or drink for 30 min. They were provided with 20g of gel tube every 10th day. They were asked to maintain their normal dietary habits throughout the study. No instructions were given concerning brushing technique and duration. Compliance evaluation checklist was given in which participants had to tick mark in corresponding boxes after every application of gel.

Data were collected using predesigned recording form and by clinical examinations at baseline, 30th day and 90th day. The recording form had two parts:

In first part, the general information regarding the participant’s demographic profile, past and present medical history, dental history, and oral hygiene practices, which was collected through an interview.

-

Second part included the clinical examination of the oral cavity and assessment of plaque and gingival scores at baseline, 30th day and 90th day using:

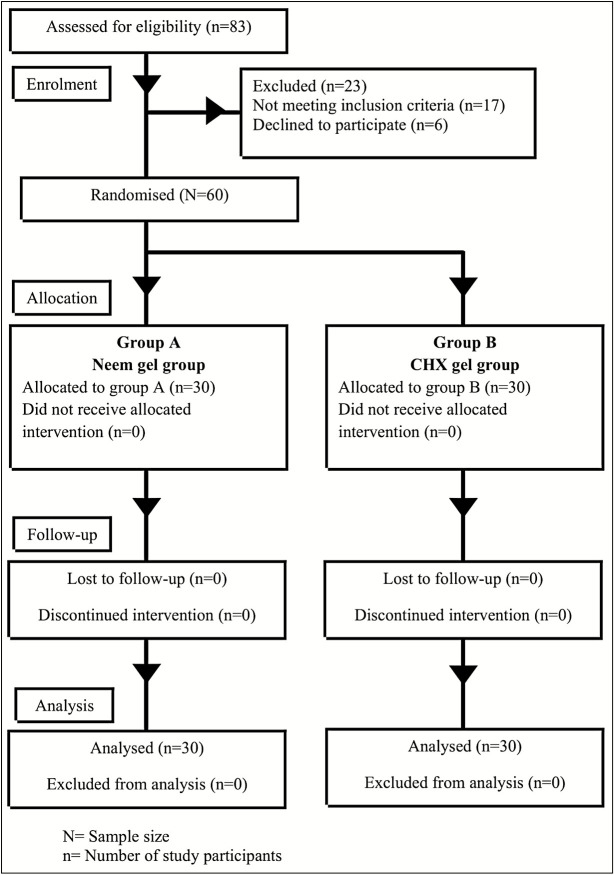

Total colony counts of S. mutans and Lactobacilli from dental plaque samples were entered into recording form after obtaining results from the microbiologist. The CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) 2010 guidelines were followed throughout the study as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of study design (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials [CONSORT] 2010 guidelines)

Plaque sample collection

Instructions were given to the participants that they should not eat or drink at least 1h before the plaque sample collection. To control the circadian variations, samples were collected between 8:00 AM and 11:00 AM. All patients were asked to wash their mouth with normal saline prior to dental plaque sampling. The study participants were seated on a chair to collect plaque from the cervical thirds of the buccal surfaces and from the pit and fissure areas using explorer. The collected samples were transferred into appropriately coded 2 mL sterile Eppendorf vials containing 1 mL normal saline and carried in a vaccine carrier with freezing mixture to the laboratory.

Microbial analysis of plaque

The plaque sample was homogenized and vortexed manually for 2 min and stirred by stirrer. 100 µL of this mixture was diluted till a dilution of 1:1000 was obtained and used for microbial analysis. Streptococcus mutans was cultured on Mitis salivarius-bacitracin (MSB) agar and Lactobacilli on De Man, rogosa and sharpe (MRS) agar being selective media for culture of these organisms. Using 5 µL of the 1:1000 dilution, sample was streaked on MSB and MRS agar under strict aseptic conditions by the aid of an inoculation loop. The MSB agar and MRS agar plates were incubated for 48h at 37°C, anaerobically using candle jar. After 48h of incubation period, tiny, raised, rough, and adherent colonies of S. mutans appeared. For Lactobacilli colonies were large and white. Electronic colony counter was used for counting identified colonies.

After the completion of 90 days period of use of gels, the study participants were educated regarding the oral health, oral hygiene maintenance, and proper method of tooth brushing with the aid of health education models and charts. Emphasizing on routine regular dental checkup, the participants who needed immediate care were directed to the required departments in Dental College and Hospital.

Statistical analysis was performed with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences software program, version 21.0 for Windows (IBM, Armonk, New York). Data were presented as mean and standard deviation (SD). For all tests, P < 0.05 was considered for statistical significance. Unpaired t test compared the difference between Groups A and B for plaque index, gingival index, and microbial colony count at baseline, 30th and 90th day. Within groups, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test was used for intragroup comparison followed by Tukey’s post hoc.

Following statistical analysis, decoding was carried out by the pharmacologist for Group A as neem gel group and Group B as CHX gel group.

RESULTS

The participants in Groups A and B were of mean ages of 27.26 ± 2.13 years and 28.10 ± 1.64 years, respectively, without statistically significant difference (P > 0.05). Table 1 shows that the mean plaque scores for Group A on 30th day and 90th day showed statistically significant reduction as compared to baseline (P < 0.05). Similar results were observed for Group B. On the intergroup comparison, there was absence of statistically significant difference at any stage (P > 0.05).

Table 1.

Comparative evaluation of mean plaque scores between two groups

| Group | Plaque index (mean ± SD) | P value intragroup comparison | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0th day | 30th day | 90th day | 0–30 day | 0–90 day | 30–90 day | |

| Group A (neem gel) | 1.60 ± 0.19 | 1.13 ± 0.14 | 0.99 ± 0.13 | <0.001** | <0.001** | 0.006* |

| Group B (CHX gel) | 1.67 ± 0.19 | 1.11 ± 0.18 | 0.93 ± 0.15 | <0.001** | <0.001** | 0.001* |

| P value intergroup comparison | 0.169 | 0.621 | 0.118 | – | – | – |

SD = standard deviation, CHX = chlorhexidine

* P < 0.05––statistically significant

**P < 0.001––statistically highly significant

DISCUSSION

Plaque-induced gingivitis is a chronic disease and it may lead to chronic periodontitis over a period of time. Gingivitis is more commonly seen among age group of 20–30 years, due to effect of long-term accumulation of plaque.[20,21,22] In our study, significant reduction was seen in the neem gel group for plaque scores over a period of 90 days [Table 1]. This antiplaque activity may be attributed to the fluorides, tannins, silica, calcium, sulfur, and saponins present in neem. Fluorides are known to show anticariogenic activity. Silica and calcium acts as abrasives and polishes the tooth surface, hence preventing accumulation of plaque.[10,23] Tannins protect from tooth decay by forming a coat over the enamel and exerting an astringent effect.[10] Wolinsky et al.[24] observed that prior to bacterial exposure, when saliva-conditioned hydroxyapatite was pretreated with neem-stick extract, it showed significant reduction in the bacterial adhesion. It implied that neem extract had potential to diminish the capability of some streptococci to colonize the tooth surfaces.

Similar results are found in the randomized controlled clinical trial conducted by Balappanavar et al.[25] among 18–25-year-old adults for 3 weeks where in 2% neem mouthwash showed statistically significant reduction in plaque scores immediately after the first rinse (P < 0.05) and every week till 3 weeks (P < 0.05). Similar trend of decrease in mean plaque scores was observed in the randomized clinical trial conducted by Chatterjee et al.[15] among 18–65-year-old adults using 0.19% neem mouthwash use over a period of 21 days (P < 0.05).

Botelho et al.[26] conducted a randomized clinical trial using 25% neem mouthwash and 0.2% CHX mouthwash in the treatment of plaque-induced gingivitis among 18–65-year-old adults and mean plaque scores were reduced significantly in neem group at 7th day and 30th day as compared to baseline (P < 0.001).

The mean gingival scores for neem gel group from baseline to follow-up till 90th day also showed significant reduction [Table 2]. The decrease in the severity of gingivitis may be attributed to anti-inflammatory action by virtue of inhibition of prostaglandin E1 (PGE1) and 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) on the inflammatory edema caused by bradykinin, histamine, 5-HT, and PGE1.[27] Alkaloids are known to exert an analgesic action.[10] Also, salivary flow decreases at night and the gel formulation slowly release the drug from viscid matrix, which maintains the concentration of drug well above the required concentration therapeutically. Also, carbopol shows mucoadhesive property, which prolongs the drug action in the oral cavity.[16] Similarly, study conducted by Chatterjee et al.,[15] Balappanavar et al.,[25] and Botelho et al.[26] showed significant reduction in mean gingival scores at follow-up measurements when compared to the baseline.

Table 2.

Comparative evaluation of mean gingival scores between two groups

| Group | Gingival index (mean ± SD) | P value intragroup | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0th day | 30th day | 90th day | 0–30 day | 0–90 day | 30–90 day | |

| Group A (neem gel) | 1.57 ± 0.13 | 1.02 ± 0.17 | 0.83 ± 0.14 | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** |

| Group B (CHX gel) | 1.55 ± 0.13 | 1.05 ± 0.17 | 0.87 ± 0.15 | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** |

| P value intergroup comparison | 0.602 | 0.641 | 0.291 | – | – | – |

SD = standard deviation, CHX = chlorhexidine

**P < 0.001––statistically highly significant

In our study, the mean S. mutans count and mean Lactobacilli count of dental plaque sample for neem gel group showed statistically significant (P < 0.05) reduction from baseline to 90th day [Tables 3 and 4]. Similarly, study conducted by Pai et al.[16] and Botelho et al.[26] showed that the bacterial count significantly reduced at follow-up as compared to baseline.

Table 3.

Comparative evaluation of mean Streptococcus mutans count expressed as 103 CFU/mL of dental plaque between two groups

| Group | Total colony count of S. mutans (mean ± SD) | P value intragroup | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0th day | 30th day | 90th day | 0–30 day | 0–90 day | 30–90 day | |

| Group A (neem gel) | 27.30 ± 5.50 | 23.63 ± 5.23 | 19.13 ± 4.71 | 0.020* | <0.001** | 0.003* |

| Group B (CHX gel) | 26.33 ± 4.75 | 21.76 ± 4.51 | 17.36 ± 4.28 | 0.001* | <0.001** | 0.001* |

| P value intergroup comparison | 0.593 | 0.509 | 0.618 | – | – | – |

S. mutans = Streptococcus mutans, SD = standard deviation, CHX = chlorhexidine

*P < 0.05––statistically significant

**P < 0.001––statistically highly significant

Table 4.

Comparative evaluation of mean Lactobacilli count expressed as 103 CFU/mL of dental plaque between two groups

| Group | Total colony count of Lactobacilli (mean ± SD) | P value intragroup | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0th day | 30th day | 90th day | 0–30 day | 0–90 day | 30–90 day | |

| Group A (neem gel) | 9.46 ± 2.80 | 7.90 ± 2.04 | 6.16 ± 1.55 | 0.019* | <0.001** | 0.008* |

| Group B (CHX gel) | 8.667 ± 3.57 | 6.933 ± 2.01 | 4.80 ± 1.44 | 0.024* | <0.001** | 0.004* |

| P value intergroup comparison | 0.498 | 0.935 | 0.854 | – | – | – |

SD = standard deviation, CHX = chlorhexidine

*P < 0.05––statistically significant

**P < 0.001––statistically highly significant

In this study, 0.2% CHX gel group the mean plaque scores and mean gingival scores showed significant reduction of from baseline to 90th day (P < 0.001) [Tables 1 and 2]. Similar results were observed by Balappanavar et al.,[25] Chatterjee et al.,[15] and Botelho et al.[26] wherein use of 0.2% CHX mouthwash showed statistically significant reduction in mean plaque and mean gingival scores at follow-up.

At baseline mean S. mutans count and mean Lactobacilli count reduced significantly from baseline to 90th day (P < 0.05) in our study [Tables 3 and 4]. The results are in consensus with study conducted by Pai et al.[16] and Botelho et al.,[26] who reported similar significant reduction in bacterial count.

In our study, intergroup comparison between 2.5% neem gel and 0.2% CHX gel for clinical parameters, no statistically significant difference was observed in the mean plaque scores and mean gingival scores at baseline, 30th day and 90th day (P > 0.05) [Tables 1 and 2]. The study by Pai et al.[6] used 5% neem extract gel and 0.2% CHX gel and observed similar trend. Similar results were observed by Chatterjee et al.[15] and Botelho et al.,[26] who used mouthwashes.

However, contrasting results were seen in the study by Pai et al.[16] where in effect of 25% neem extract gel was compared with 0.2% CHX mouthwash on mean plaque scores and mean gingival scores over a period of 6 weeks. This could be attributed to many factors. First, the concentration of neem extract in their study is 25% which is higher as compared to that used in our study, that is, 2.5%. Second is the type of extract. In our study, we have used aqueous extract of neem whereas in their study alcohol-based extract is used. Third is the mode of drug delivery. CHX in their study was used in the form of mouthwash where as in our study we have used CHX in the form of gel. Fourth is the duration of study. We have evaluated the effect over the duration of 90 days whereas in their study is of relatively shorter period of 6 weeks.

In our study, no significant difference was found in the mean S. mutans count and mean Lactobacilli count reduction between two groups at 30th and 90th day. Similar results were observed by Botelho et al.[26]

However, study by Pai et al.[16] showed significant reduction in salivary S. mutans bacterial count in the group treated with the 25% neem extract gel compared to the 0.2% CHX mouthwash. This may be attributed to different concentration and type of neem extract, the mode of drug delivery and the duration of study.

The shelf life of this neem gel formulation is found to be 12 months so far and further stability studies are going on. It is expected that the shelf life of this gel will be around 24 months which is in line with other over the counter commonly used gels for oral health maintenance. Hence, the use of product is economical and feasible.

This study showed that because of mucoadhesive property of the gelling agent carbopol, locally the drug was maintained at effective levels for an extended period. This may prove useful for the children less than 6 years of age with poor swallowing reflex, swallowing up to 100% of the mouthwash. Similarly, the gel may be used in treating oral infections focusing specific groups such as people with special care needs and medically compromised individuals.

Limitations

In our study, Hawthorne effect and Novelty effect may be seen. Although attempt was made to assess compliance in the appropriate use of allocated gels, the measures do not confirm the regular use of gels. Another limitation was that the use of antimicrobials over the period of 3 months was not taken into account at follow-up visits. The sample size was relatively small and duration of study was short. Hence, further studies for longer duration involving larger sample size and different age groups are recommended.

CONCLUSION

In our study, neem gel has shown anti-plaque and anti-gingivitis effects comparable to CHX gel. This is a significant finding. Neem is available in ample and accessible. Also it is economically and cultural feasible and acceptable. This gel form as vehicle for drug delivery can be useful in children below 6 years and special care need groups with poor swallowing reflex resulting in swallowing anywhere ranging from 100% of mouthwash. This property can also be used for improving oral health in specific groups such as people with special care needs and medically compromised individuals.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

We are thankful to Mr. Uttam Tendulkar––Director, BioGreen Healthcare for sincere help in preparation of gels and allocation concealment.

The trial is registered in Clinical Trial Registry, India (registration number CTRI/2017/10/010243).

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. Oral Health. [Last accessed on 2020 March 17 at 2:58 PM]. Fact sheet no. 318. April 2012. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/oral-health .

- 2.Moran JM. Chemical plaque control–prevention for the masses. Periodontol 2000. 1997;15:109–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1997.tb00110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rodrigues IS, Tavares VN, Pereira SL, Costa FN. Antiplaque and antigingivitis effect of Lippia sidoides: a double-blind clinical study in humans. J Appl Oral Sci. 2009;17:404–7. doi: 10.1590/S1678-77572009000500010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gurenlian JAR. The role of dental plaque biofilm in oral health. J Dent Hyg. 2007;81:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zanatta FB, Antoniazzi RP, Rösing CK. The effect of 0.12% chlorhexidine gluconate rinsing on previously plaque-free and plaque-covered surfaces: a randomized, controlled clinical trial. J Periodontol. 2007;78:2127–34. doi: 10.1902/jop.2007.070090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pai MR, Acharya LD, Udupa N. The effect of two different dental gels and a mouthwash on plaque and gingival scores: a six-week clinical study. Int Dent J. 2004;54:219–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.2004.tb00283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Franco Neto CA, Parolo CC, Rösing CK, Maltz M. Comparative analysis of the effect of two chlorhexidine mouthrinses on plaque accumulation and gingival bleeding. Braz Oral Res. 2008;22:139–44. doi: 10.1590/s1806-83242008000200008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Teles RP, Teles FR. Antimicrobial agents used in the control of periodontal biofilms: effective adjuncts to mechanical plaque control? Braz Oral Res. 2009;23:39–48. doi: 10.1590/s1806-83242009000500007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kumar VS, Navaratnam V. Neem (azadirachta indica): prehistory to contemporary medicinal uses to humankind. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 2013;3:505–14. doi: 10.1016/S2221-1691(13)60105-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prashant GM, Chandu GN, Murulikrishna KS, Shafiulla MD. The effect of mango and neem extract on four organisms causing dental caries: Streptococcus mutans, Streptococcus salivavius, Streptococcus mitis, and Streptococcus sanguis: an in vitro study. Indian J Dent Res. 2007;18:148–51. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.35822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nayak A, Nayak RN, Soumya B, Bhat K, Kudalkar M. Evaluation of antibacterial and anticandidial efficacy of aqueous and alcoholic extract of neem (Azadirachtaindica): an in vitro study. Int J Res Ayurveda Pharm. 2011;2:230–5. [Google Scholar]

- 12.PackiaLekshmi NCJ, Sowmia N, Viveka S, Brindha JR, Jeeva S. The inhibiting effect of Azadirachtaindica against dental pathogens. Asian J Plant Sci Res. 2012;2:6–10. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sharma A, Sankhla B, Parkar SM, Hongal S, K T, Cg A. Effect of traditionally used neem and babool chewing stick (datun) on Streptococcus mutans: an in-vitro study. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8:ZC15–7. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2014/9817.4549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oosterwaal PJ, Mikx FH, van ‘t Hof MA, Renggli HH. Comparison of the antimicrobial effect of the application of chlorhexidine gel, amine fluoride gel and stannous fluoride gel in debrided periodontal pockets. J Clin Periodontol. 1991;18:245–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1991.tb00422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chatterjee A, Saluja M, Singh N, Kandwal A. To evaluate the antigingivitis and antiplaque effect of an Azadirachtaindica (neem) mouthrinse on plaque induced gingivitis: a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2011;15:398–401. doi: 10.4103/0972-124X.92578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pai MR, Acharya LD, Udupa N. Evaluation of antiplaque activity of azadirachta indica leaf extract gel––a 6-week clinical study. J Ethnopharmacol. 2004;90:99–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2003.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Löe H. The gingival index, the plaque index and the retention index systems. J Periodontol. 1967;38:610, 6. doi: 10.1902/jop.1967.38.6.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Löe H, Silness J. Periodontal disease in pregnancy. Acta Odontol Scand. 1963;21:533–51. doi: 10.3109/00016356309011240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.James PMC, Beal JF. Dental epidemiology and survey procedures. In: Slack JL, Burt BA, editors. Dental public health: an introduction to community dental health. 2nd ed. Bristol, UK: John Wright and Sons; 1981. pp. 86–118. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haloi R, Ingle NA, Kaur N, Gupta R. Comparing the oral health promoting role and knowledge of government and private primary school teachers in Mathura city. Int J Sci Study. 2014;1:9–14. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ababneh KT, Abu Hwaij ZM, Khader YS. Prevalence and risk indicators of gingivitis and periodontitis in a multi-centre study in north Jordan: a cross sectional study. BMC Oral Health. 2012;12:1. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-12-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dayakar MM, Shivprasad D, Pai PG. Assessment of periodontal health status among prison inmates: a cross-sectional survey. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2014;18:74–7. doi: 10.4103/0972-124X.128230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chava VR, Manjunath SM, Rajanikanth AV, Sridevi N. The efficacy of neem extract on four microorganisms responsible for causing dental caries viz Streptococcus mutans, Streptococcus salivarius, Streptococcus mitis and Streptococcus sanguis: an in vitro study. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2012;13:769–72. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10024-1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wolinsky LE, Mania S, Nachnani S, Ling S. The inhibiting effect of aqueous azadirachta indica (neem) extract upon bacterial properties influencing in vitro plaque formation. J Dent Res. 1996;75:816–22. doi: 10.1177/00220345960750021301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Balappanavar AY, Sardana V, Singh M. Comparison of the effectiveness of 0.5% tea, 2% neem and 0.2% chlorhexidine mouthwashes on oral health: a randomized control trial. Indian J Dent Res. 2013;24:26–34. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.114933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Botelho MA, Santos RA, Martins JG, Carvalho CO, Paz MC, Azenha C, et al. Efficacy of a mouthrinse based on leaves of the neem tree (Azadirachtaindica) in the treatment of patients with chronic gingivitis: a doubleblind, randomized, controlled trial. J Med Plant Res. 2008;2:341–6. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chattopadhyay RR, Chattopadhyay RN, Maitra SK. Study of possible mechanism of anti-inflammatory activity of Azadirachtaindica leaf extract. Indian J Pharmacol. 1993;25:99–100. [Google Scholar]