ABSTRACT

Chlorhexidine is a cationic bisbiguanide with broad antibacterial activity, and wide spectrum of activity encompassing gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria, yeasts, dermatophytes and some lipophilic viruses. Its antibacterial action is due to the disruption of the bacterial cell membrane by the chlorhexidine molecules, increasing the permeability and resulting in cell lysis. Thus, chlorhexidine plays a key role in the dentistry and is used to treat or prevent periodontal disease, and has earned its eponym of the gold standard. This article reviews in detail about the mechanism of action, indications, forms and various studies related to chlorhexidine.

KEYWORDS: Antiseptic, chemical plaque control, chlorhexidine, mouthrinse, periodontal diseases

INTRODUCTION

Plaque is a resilient, yellowish material that firmly adheres to the tooth surface and restorations.[1] The plaque plays a key role in the initiation of gingivitis and periodontal diseases. The complete elimination of plaque by mechanical therapy is often impossible, so antimicrobial agents are used as an adjunct to the mechanical approaches. Chlorhexidine (CHX) is the most effective antimicrobial agent, and the clinical effect of CHX is likely due to both its substantive and antibacterial properties.[2]

HISTORY

Imperial Chemical Industries in 1940 developed CHX first in England. Schroeder in 1969 first used CHX for plaque inhibition. Later in 1997, CHX gelatin chip—PerioChip (Perio Products Ltd, Jerusalem, Israel) was introduced for the treatment of periodontitis.[3]

STRUCTURE

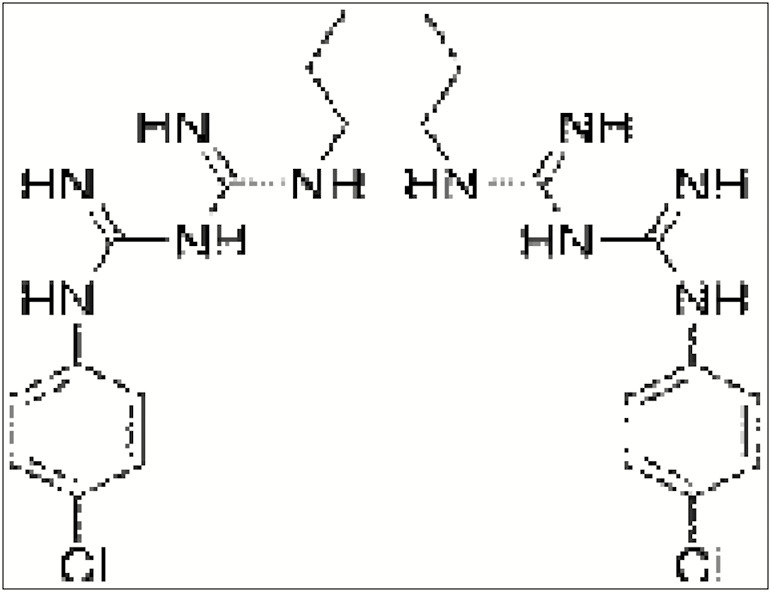

CHX is a bisbiguanide that consists of four chlorophenyl rings and two biguanide groups connected by a central hexamethylene bridge as shown in Figure 1. This is strongly basic with pH levels >3.5, and with the positive charges on either sides of the hexamethylene bridge.[2]

Figure 1.

Chlorhexidine—structure

FORMS

The three forms of CHX are digluconate and acetate, which are water soluble, and hydrochloride salts that are less water soluble.[4]

AVAILABILITY

CHX is available in gels, chips, sprays, varnishes, and mouthwashes. CHX is also incorporated in toothpaste and chewing gums.[4]

SUBSTANTIVITY

The unique property of CHX is its substantivity. The substantivity is the ability of drugs to adsorb and bind to tissues. CHX binds to the pellicle and saliva.[5] The action of CHX persists up to 5 h and retains in the oral cavity for more than 12 h.

SPECTRUM OF ACTIVITY

CHX is a membrane-type antimicrobial agent and acts on the inner cytoplasmic membrane.[6] Depending on the dose, the action varies as bacteriostatic or bactericidal. It acts against gram-positive and gram-negative bacterias, dermatophytes, viruses, fungi, and yeasts.[7] They also neutralize periodontal pathogens such as Streptococcus aureus, Porphyromonas gingivalis, and Prevotella intermedia.[8]

PIN-CUSHION EFFECT

The positively charged end of CHX molecule binds to the tooth surface and the negatively charged end interacts with bacterial membrane, which is termed as a pin-cushion effect.[4]

MECHANISM OF ACTION

Antibacterial action

The positive charges of CHX molecule are present over the nitrogen atoms on the sides of the hexamethylene bridge.[3] At low concentration, CHX damages the cellular transport of the bacterial cell by creating pores in the cellular membrane.[5] In higher concentration, CHX penetrates the bacterial cell and causes bacteriolysis.[9]

Bacteriostatic effect

The CHX molecule attracts the negatively charged bacterial cell surface and attaches to phosphate-containing compounds. This alters the integrity of bacterial cell membrane.[10] The CHX molecule is further attracted toward the inner cell membrane and is bound to phospholipids. This bacteriostatic effect is reversible.

Bactericidal effect

When the concentration increases, CHX causes greater damage to the membrane. The leakage of low-molecular-weight components causes the coagulation and precipitation of the cytoplasm by the formation of phosphated complexes. This bactericidal stage is irreversible.[5]

Anti-plaque effect

The substantivity of CHX made it a more suitable antimicrobial agent for the inhibition of plaque.[11] The CHX affects the pellicle formation by blocking the acidic groups on the salivary glycoproteins. There is a reduction in the protein adsorption to the tooth surface. CHX binds to the bacterial surface and thus reduces the formation of plaque by precipitating the agglutination factors in saliva and displaces the calcium. Thus, plaque is prevented from forming as the bacterial colonies.[5]

Clinical applications in periodontics

CHX is mainly used as an adjunct to scaling and root planing. It is also used after periodontal surgeries. It is indicated in the maintenance protocol for immediate implants[12] in patients with intermaxillary fixation and who are under high risk of caries. To maintain oral hygiene in patients with physical and mental disabilities, CHX sprays and mouthwashes can be used. It is also used in medically compromised patients.[13] CHX is also used as an adjunct to antibiotic prophylaxis.[14] The other uses include subgingival irrigation, oral malodor, denture stomatitis, and hypersensitivity. CHX irrigation is performed in full-mouth disinfection procedures. CHX is used as a local drug delivery system as biodegradable chip for treating localized periodontitis.[15]

Adverse effects

The prolonged use of CHX is limited by its long-term side effects. The main adverse effect is extrinsic staining of teeth.[9] A brown stain occurs after the use of CHX and is due to the polymerization reaction of carbohydrate in pellicle producing pigmented substances called as melanoidins. CHX also denatures the proteins in pellicle and forms free sulfhydryl groups, and these react with iron or tin ions producing yellow pigmented products. CHX also reacts with dietary ketones to form insoluble, colored compounds.[1] The other adverse effects are alteration in taste particularly for salt taste, greater chance for calculus formation, staining of mucous membranes and, parotid swelling.[16]

Safety of CHX

CHX exhibits very low toxicity as it is poorly absorbed in the gut. No teratogenic alterations and no evidence of formation of carcinogenic substances are reported.[9]

Precautions

The intake of tea, coffee, and red wine should be avoided along with CHX.[17] There should be a 30-min lapse between the usage of CHX and tooth paste because the anionic surfactants in the toothpastes reduce the substantivity of CHX.[18]

CONCLUSION

CHX is the most potent chemical plaque control agent that has various clinical applications in periodontics. Its broad antimicrobial spectrum can be considered as boon for maintaining overall oral health. Thus, the effective antibacterial actions of CHX make it a viable option for use in all periodontal procedures with very few undesirable side effects.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lindhe J, Karring T, Lang NP. Clinical periodontology and implant dentistry. 4th ed. Chichester: Blackwell Munksgaard; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sajjan P, Laxminarayan N, Kar P, Sajjanar M. Chlorhexidine as an antimicrobial agent in dentistry—a review. OHDM. 2016;15:93–100. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balagopal S, Radhika A. Chlorhexidine: the gold standard antiplaque agent. J Pharm Sci Res. 2013;5:270–4. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Poonam S, Rathore K, Khurana D. Chlorhexidine—an antiseptic in periodontics. J Dent Med Sci. 2014;13:85–8. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones CG. Chlorhexidine: is it still a gold standard? Perio 2000. 1997;15:55–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1997.tb00105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lang NP, Brecx MC. Chlorhexidine digluconate—an agent for chemical plaque control and prevention of gingival inflammation. J Periodont Res. 1986;21:74–89. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Emisilon C. Susceptibility of various microorganisms to chlorhexidine. Scand J Dent Res. 1977;85:255–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1977.tb00561.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grenier D. Effect of chlorhexidine on the adherence properties of porphyromonas gingivalis. J Clin Periodontol. 1996;23:140–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1996.tb00547.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mathur S, Mathur T, Srivastava R, Khatri R. Chlorhexidine: the gold standard in chemical plaque control. Natl J Physiol Pharm Pharmacol. 2011;1:45–50. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zanatta FB, Antoniazzi RP, Rosing CK. Staining and calculus formation after 0.12% chlorhexidine rinses in plaque- free and plaque covered surfaces: a randomized trial. J Appl Oral Sci. 2009;18:515–21. doi: 10.1590/S1678-77572010000500015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jenkins S, Addy M, Wade W. The mechanism of action of chlorhexidine: a study of plaque growth on enamel inserts in vivo. J Clin Periodontol. 1988;15:415–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1988.tb01595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keijser JA, Verkade H, Timmerman MF, Van der Weijden FA. Comparison of 2 commercially available chlorhexidine mouthrinses. J Periodontol. 2003;74:214–8. doi: 10.1902/jop.2003.74.2.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Addy M, Moran JM. Clinical indications for the use of chemical adjuncts to plaque control. Periodontol 2000. 1997;15:52–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1997.tb00104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greenstein G, Berman C, Jaffin R. Chlorhexidine. An adjunct to periodontal therapy. J Periodontol. 1986;57:370–7. doi: 10.1902/jop.1986.57.6.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Divya PV, Bindu RN, Nandakumar K. Clinical efficacy of sustained release chlorhexidine in collagen membrane in the non-surgical management of chronic localised periodontitis. J Den Med Sci. 2018;17:22–9. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gürgan CA, Zaim E, Bakirsoy I, Soykan E. Short-term side effects of 0.2% alcohol-free chlorhexidine mouthrinse used as an adjunct to non-surgical periodontal treatment: a double-blind clinical study. J Periodontol. 2006;77:370–84. doi: 10.1902/jop.2006.050141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eley BM. Antibacterial agents in the control of supragingival plaque—a review. British Dent Journal. 1999;186:286–96. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4800090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jenkins S, Addy M, Newcombe R. The effects of a chlorhexidine toothpaste on the development of plaque, gingivitis and tooth staining. J Clin Periodontol. 1993;20:59–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1993.tb01761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]