Abstract

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) crisis has greatly affected human lives across the world. Uncertainty and quarantine have been affecting people’s mental health. Estimations of mental health problems are needed immediately for the better planning and management of these concerns at a global level. A rapid scoping review was conducted to get the estimation of mental health problems in the COVID-19 pandemic during the first 7 months. Peer-reviewed, data-based journal articles published in the English language were searched in the PubMed, Medline, and Google Scholar electronic databases from December 2019 to June 2020. Papers that met the inclusion criteria were analyzed and discussed in this review. A total of 16 studies were included. Eleven studies were from China, two from India, and one from Spain, Italy, and Iran. Prevalence of all forms of depression was 20%, anxiety 35%, and stress 53% in the combined study population of 113,285 individuals. The prevalence rate of all forms of depression, anxiety, stress, sleep problems, and psychological distress in general population was found to be higher during COVID-19 pandemic.

Keywords: COVID-19, mental health, stress, anxiety, depression

Introduction

The outbreak of the third coronavirus severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV2), also named coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), has occurred more rapidly than people could have ever imagined from the experience of the past two SARS-CoV and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. 1 2 To control the spread of this virus, the entire world acted fast and in collaboration, but the COVID-19 pandemic could not be controlled as it has rather impacted human lives across the globe. In 6 months, in 216 countries including territories, 13,876,441 people got confirmed for infection and 593,087 lost their lives. 3 To reduce the risk of COVID-19 exposure, social distancing was suggested and enforced. People of all walks are required to stay in their homes and maintain physical distance in any given situation while they are out for any essential reason. 4 5 This intervention has not only impacted all ongoing activities but has led to a tremendous negative effect on the mental health of people. The fear of contracting the virus, lack of treatment, higher mortality associated with the virus, and uncertainty about when the virus would be controlled and when a vaccine would be available are the major factors that were found to be highly responsible in increasing psychological distress, adjustment, and even more serious mental health problems. Economic loss, interrupted daily routine, the inability of engaging in social events, and constant news exposure are additional factors that affected mental health. The crisis became an unmanageable stressor. Incidences were even noticed where some people could not handle the mental pressure, and as an escape from traumatizing reality, they committed suicide. 6 7

Editorials, scientific letters, perspectives, and commentaries in scientific literature and reports in print and visual media have pointed out an increase in mental health problems. Experts across the world expressed concerns for an increasing toll of mental health problems and urged for mental health support. 8 The increase in mental health problems in every society and age group in every nation has turned out to be another important global public health concern during this pandemic. 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Experts have suggested appropriate and cost-effective ways to address psychological distress and their resulted effects. 17 A lot of attention has been given to this emerging situation with mental health concerns. However, we still lack quantifiable information about the increase in mental health problems due to the pandemic. Policy makers need to know the extent of the problem before making the appropriate arrangements for addressing this issue of increased mental health problems. This scoping review was conducted to provide an estimate of various mental health problems that occurred due to COVID-19.

Objective

The aim of this study was to review the prevalence of depression, anxiety, stress, and sleep problems during the first 7 months of COVID-19 pandemic.

Methodology

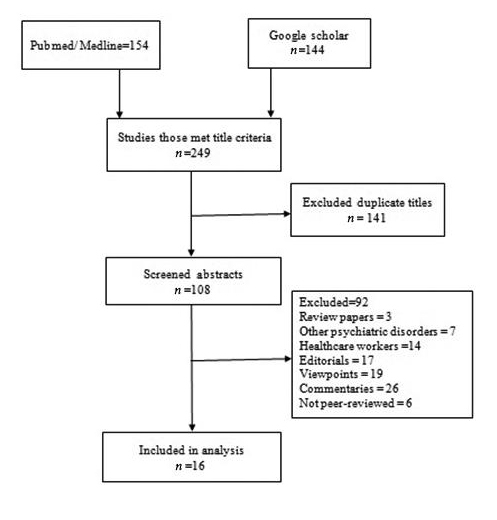

Articles published in the English language were searched by the first author in the PubMed, Medline, and Google Scholar electronic databases from December 2019 to June 30, 2020. Search with “COVID-19,” “coronavirus,” “SARS-CoV-2,” “nCov,” “pandemic,” “mental health,” “psychiatric problems,” “anxiety,” “depression,” “stress,” “psychological distress,” and “sleep” words in multiple combinations was performed. Only data-based articles were considered for inclusion. Editorials, perspective, case reports, viewpoints, opinion, letters to the editor, commentaries, secondary data analysis, and review articles were excluded. Gray literature was also excluded. Ahead of print papers were also included. A total of 298 articles, 154 in PubMed/Medline, and 144 in Google Scholar electronic databases containing at least two search words were found. After reading titles, 49 articles that did not meet the title criteria were excluded. Further, 141 articles with duplicate titles were removed and the remaining 108 articles were selected for reading their abstracts. In reading the abstracts or summaries of the articles, 92 articles were excluded for not meeting the inclusion criteria. Remaining 16 articles were read in full and included in the review ( Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of the literature search process.

Results

Out of all 16 research studies included in the analysis, 11 studies came from China, two from India, and one each from Italy, Spain, and Iran. Except for one study that followed longitudinal research design, all others followed cross-sectional design. Data on mental health problems for all studies were obtained from 113,285 people in five countries including 87.16% from China, 9.49% Iran, 2.44% Italy, 0.89% India, and 0.86% Spain. Eleven studies from China have assessed anxiety and out of those, seven assessed both depression and anxiety ( Table 1 ).

Table 1. Reviewed studies and their salient findings ( n = 16) .

| Authors | Country | Study type and scale | Sample population | Outcome variable/objective | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Huang and Zhao, 2020 18 | China | Cross-sectional, web-based. Chinese versions of generalized anxiety disorder-7 (GAD-7), The Center for Epidemiology Scale for Depression (CES-D), Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) were used | General public Sample 7,236 self-selected volunteers |

To estimate GAD, depressive symptoms, and sleep quality | The overall prevalence of GAD was found 35.1%, depressive symptoms 20.1%, and sleep quality 18.2% GAD was found higher among younger people than older age people |

| Wang et al, 2020 19 | China | Longitudinal study. Event Scale-Revised (IES-R) and the depression, anxiety and stress scale (DASS-21) were used | General public Surveyed twice—during the initial outbreak and the epidemic's peak 4 weeks later Total sample was 1,738. First time 1,210 and the second time 861 |

Assessed psychological impact, stress, anxiety, and depression during this pandemic | In the initial survey, moderate-to-severe stress was found among 8.1%, anxiety 28.8%, and depression 16.5%. No significant changes were noticed in prevalence in the second round ( p > 0.05) |

| Qiu et al, 2020 20 | China | Cross-sectional, nationwide large-scale. Self-reporting questionnaire was designed—The COVID-19 Peritraumatic Distress Index (CPDI). Cronbach’s α of CPDI is 0.95 ( p < 0.001). This tool measured anxiety, depression, specific phobias, cognitive change, avoidance and compulsive behavior, physical symptoms, and loss of social functioning | General population. Total of 52,730 people from 36 provinces responded to the survey. Males 18,599 (35.27%) and females 34,131 (64.73%) | To estimate the prevalence of psychological distress | A total of 29.29% of respondents experienced psychological distress. Females, young adults between 18 to 30 years and over 60 years of age experienced higher psychological distress compared with males, younger than 18 years and between 30 and 60 years of age |

| Wang et al, 2020. 21 | China | Cross-sectional. An online survey was conducted using snowball sampling. IES-R, and the DASS-21 for mental health were used |

General population. 1210 respondents from 194 cities responded to the survey | To estimate psychological impact was assessed | About 53.8% were found to have some level of stress. Among those, 16.5% experienced moderate-to-severe depressive symptoms; 28.8% moderate-to-severe anxiety symptoms; and 8.1% moderate to severe stress |

| Ahmed, et al, 2020 22 | China | Cross-sectional, online survey. The Chinese version of Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), the Beck Depression Inventory–II (BDI-II), the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT), the Warwick Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (WEMWBS) were used |

1,074 Chinese people | To estimate the prevalence of depression, anxiety, hazardous drinking, and poor mental well-being due to lockdown | Approximately 37.1% participants had different levels of depression (mild 10.2%, moderate 17.8%, and severe 9.1%) 29% suffered from different levels of anxiety (mild 10.1%, moderate 6.0% and severe 12.9%). Hazardous drinking increased to 29.1%, harmful drinking increased to 9.5%, and alcohol dependency reached 1.6%. About 32.1% were found to have lower mental well-being |

| Lei et al, 2020 28 | China | Cross-sectional study. Used the self-rating anxiety scale (SAS) and the self-rating depression scale (SDS) |

1593 adults aged 18 years and above | To find out the rate of depression and anxiety between affected and nonaffected people | Depression and anxiety were found to be 8.3% and 14.6% respectively in unaffected people. While depression and anxiety were found 12.9 and 22.4% of people who had someone in their family, friends, relatives, or in the neighborhood contracting the virus |

| Zhou et al, 2020 23 | China | Cross-sectional, online survey. Used Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) and the GAD-7 questionnaire |

Students 12 to 18 years Total participants 8079 |

To assess the prevalence of depression and anxiety | The prevalence of depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, and a combination of depressive and anxiety symptoms was found among 43.7, 37.4, and 31.3%, respectively |

| Gao et al, 2020 24 | China | Cross-sectional study. The Chinese version of WHO-Five Well-Being Index (WHO-5) and GAD-7 were used |

Chinese citizens above 18 years of age Total of 4872 participants |

To find out the prevalence of depression and anxiety | The prevalence of depression, anxiety, and combination of depression and anxiety (CDA) was 48.3 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 46.9–49.7%), 22.6 (95% CI: 21.4–23.8%), and 19.4% (95% CI: 18.3–20.6%), respectively |

| Verma and Mishra, 2020 25 | India | Cross-sectional, electronic survey. Self-reported DASS-21 was used |

A total of 354 respondents completed survey | To find out the prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress | In total, 25% had moderate-to-severe depression, 28% anxiety and 11.6% stress |

| Mazza et al, 2020 26 | Italy | Cross-sectional, online survey. The Italian version of the DASS-21, and two scales (negative affect and detachment) of the personality inventory, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fifth edition (DSM-5–Brief Form) (Personality Inventory for DSM-5—Brief Form, PID-5-BF) were used |

A total of 2,766 Italian participants | To find out the prevalence of psychiatric symptoms in the general population | The prevalence of severe depression 15.4%, moderate 17%, severe anxiety 11.5%, and moderate anxiety 7.2%, and extremely high stress in 12.6% and high stress in 14.6% were found |

| Ozamiz-Etxebarria et al, 2020 27 | Spain | Cross-sectional. DASS-21 was used | A total of 976 adults took the survey | To estimate the level of depression, anxiety, and stress in the general population | Depression in males: mild 8.7, moderate 4.0, severe 2.9, and extremely severe 1.7%. In females: mild 8.6, moderate 7.1, severe 2.3 and extremely severe 3.0% Anxiety in male: mild 4.0, moderate 5.2, severe 1.2, and extremely severe 3.5% In female: mild 7.0, moderate 12.0, severe 3.3, and extremely severe 3.6% Stress in male: mild 9.2, moderate 5.2, severe 2.9 and extremely severe 0.6%. In female: mild 8.9, moderate 9.0, severe 3.1, and extremely severe 1.2% |

| Cao et al, 2020 38 | China | Cross-sectional GAD-7 |

College students Sample 7,143 responded |

To estimate the prevalence of anxiety | Severe anxiety was experienced by 0.9, moderate anxiety by 2.7, and mild anxiety by 21.3% in college students. Living in urban, with parents, and steady income found to be protective factors against anxiety |

| Zhang and Ma, 2020 39 | China | Cross-sectional, online survey. A modified validated questionnaire that assessed the IES was used | Chinese residents aged ≥18 years. A total of 263 participants,106 males, and 157 females responded to the survey | To assess mental health and quality of life | The pandemic situation was found to be mildly stressful to all. About 53.3% did not feel helpless, while 52.1% felt horrified and apprehensive |

| Moghanibashi-Mansourieh, 2020 40 | Iran | Cross-sectional, online survey. DASS-21 | 10,754 individuals | To find the association of anxiety rate with age, gender, education | Women had higher rate of anxiety (95% CI [0.1, 81.36] than men did. Compared with other age groups, people between 21 and 40 years had the highest rate of anxiety. Anxiety rate increased with education |

| Zhou et al, 2020 30 | China | Cross-sectional PSQI, the PHQ-9, and the GAD-7 were used | Young adults 12–29 years Participants 11,835 |

To find out the prevalence of insomnia due to the pandemic | Prevalence of insomnia was found 23.2% |

| Roy, et al, 2020 29 | India | Cross-sectional. An online survey was conducted using a semi-structured questionnaire using a nonprobability snowball sampling technique | General public. A total of 662 responses were received | To assess the knowledge, attitude, anxiety experience, and perceived mental healthcare need among the adult Indian population | The anxiety levels identified in the study population were found higher |

Depression

The prevalence of depression ranged from 8.3 to 48.3% in the respondents from China. 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 In India, depression was reported in 25%, Italy 15.4 to 17%, and in Spain 1.7% extreme depression to 8.7% mild depression. 25 26 27

Anxiety

The prevalence of anxiety in general population in China ranged from 2 to 37%. 18 19 20 21 22 23 25 28 29 30 31 32 In Italy, prevalence of anxiety was found in the range of 7.2 to 11.5%, 26 in Spain 1.2 to 4%, 27 and in India ~28%. 25 29

Stress

The prevalence of stress in China was found to range between 8.1 and 29.29% in survey respondents. 19 20 21 In India, stress was experienced by 11.6%, 25 in Italy by 14.6%, 26 and in Spain for men from 0.6% extreme severe stress to 9.2% mild stress and for women from 1.2% extreme severe stress to 8.9% mild stress. 24 The prevalence of insomnia ranged from 18.2 to 23.2% in China 18 30 ( Table 1 ).

Discussion

Worldwide, researchers have expressed deep concerns toward an increase in mental health issues around the world, in general, as well as, in vulnerable populations. 31 32 Estimations of the prevalence are needed for the planning purpose. However, the global behaviors and perception in COVID-19 make it difficult to measure true prevalence of emerging rates of mental health problems in the population. 33 This review is consistent with the call of the researchers that attempted to provide a snapshot of the prevalence rates, which have been estimated around the world. Challenges posed during COVID-19 are much different and wider than the challenges faced by individuals in nonpandemic periods; therefore, it is difficult to compare the finding of this research. However, it is worth emphasizing that the high rate of depression up 20%, anxiety 35%, and stress 53% in the survey population indicates a high need for preventive and curative care for mental health concerns. Only one study included in this analysis followed a cohort research design that did not demonstrate an increase in the rate of mental health problems during this pandemic. 19 This information is very crucial. It indicates that some other factors working simultaneously are having protective effects on populations, reducing the escalation of mental health problems. However, the COVID-19 situation has not changed much yet since the beginning. Limited progress has taken place toward the development of a vaccine. The entire world is probably going to live almost in a similar state of uncertainty until a permanent solution to combat this virus is discovered. Looking at the findings of these cross-sectional studies, further increases in mental health problems can be experienced in the future. Unaddressed psychological distress and anxiety experiences for a prolonged period may result in more serious mental health issues. 34 35

Limitations of the Studies

Some of the major limitations of the included research studies are being cross-sectional, smaller sample sizes, and self-administration of the tests. Research studies have only provided points of prevalence. There is also a high chance of self-reported bias as we know that people can react to news and public perception.

Limitations of This Review

Because of the urgent nature of the issue, this was a rapid scoping review and as such multiple databases could not be included. Only English Language articles were included and also the gray literature was excluded. As a result, the review cannot claim to be exhaustive of all prevalence studies on the topic that could underestimate or overestimate the prevalence. The review focuses on only the first 7 months and the prevalence rates could be modified as time elapses.

Conclusion

The findings of this review demonstrate that the occurrence of mental health problems, specifically adjustment and phobia related, has increased in all populations. However, these studies primarily came from developing countries, so there is no scientific estimation of prevalence available of such mental health issues in other countries, specifically in developed nations that have suffered more deaths due to COVID-19. Mental health problems do not always need medical and therapeutic intervention as some of the problems can be healed at community levels. 17 Does an increase in depression, anxiety, stress, insomnia, and phobia need more medicalized and therapeutic attention during this crisis when mental health experts have the same level of COVID-19-related information, or should mental health experts analyze the situation more carefully, identify protective factors available in the community, and offer more information to the public to adjust in this crisis? This is one of the important questions of this review that urges attention for future research. Researchers not only need to find out the pandemic-related global incidence of mental health problems, but they must also evaluate the effect and role of social ecology in the progression and healing of the mental health issue to address this concern more appropriately. 17 36 37

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest None declared.

References

- 1.NIH. 2020 National Institute for Health. Coronaviruses. Covid-19 is an emerging, rapidly evolving situation. Available at: https://www.niaid.nih.gov/diseases-conditions/coronaviruses. Accessed July 17, 2020

- 2.Sanche S, Lin Y T, Xu C, Romero-Severson E, Hengartner N, Ke R. High contagiousness and rapid spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26(07):1470–1477. doi: 10.3201/eid2607.200282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO. 2020. World Health Orgnisation, Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. Available at: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019. Accessed July 18, 2020

- 4.Rundle A G, Park Y, Herbstman J B, Kinsey E W, Wang Y C. COVID-19-related school closings and risk of weight gain among children. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2020;28(06):1008–1009. doi: 10.1002/oby.22813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sen-Crowe B, McKenney M, Elkbuli A. Social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic: staying home save lives. Am J Emerg Med. 2020;38(07):1519–1520. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.03.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sahoo S, Rani S, Parveen S et al. Self-harm and COVID-19 pandemic: An emerging concern - a report of 2 cases from India. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;51:102104. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mamun M A, Griffiths M D. First COVID-19 suicide case in Bangladesh due to fear of COVID-19 and xenophobia: possible suicide prevention strategies. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;51:102073. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xiang Y T, Yang Y, Li W et al. Timely mental health care for the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak is urgently needed. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(03):228–229. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30046-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Torales J, O’Higgins M, Castaldelli-Maia J M, Ventriglio A. The outbreak of COVID-19 coronavirus and its impact on global mental health. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2020;66(04):317–320. doi: 10.1177/0020764020915212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shigemura J, Ursano R J, Morganstein J C, Kurosawa M, Benedek D M. Public responses to the novel 2019 coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in Japan: mental health consequences and target populations. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2020;74(04):281–282. doi: 10.1111/pcn.12988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xie X, Xue Q, Zhou Y et al. Mental health status among children in home confinement during the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak in Hubei Province, China. JAMA Pediatr. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mukhtar S. Mental health and psychosocial aspects of coronavirus outbreak in Pakistan: psychological intervention for public mental health crisis. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;51:102069. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Banerjee D. How COVID-19 is overwhelming our mental health. Nature India. 2020 doi: 10.1038/nindia.2020.46. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park S C, Park Y C. Mental health care measures in response to the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak in Korea. Psychiatry Investig. 2020;17(02):85–86. doi: 10.30773/pi.2020.0058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zandifar A, Badrfam R. Iranian mental health during the COVID-19 epidemic. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;51:101990. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.101990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee J. Mental health effects of school closures during COVID-19. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020;4(06):421. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30109-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pfefferbaum B, North C S. Mental health and the Covid-19 pandemic. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2008017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang Y, Zhao N. Generalized anxiety disorder, depressive symptoms and sleep quality during COVID-19 outbreak in China: a web-based cross-sectional survey. Psychiatry Res. 2020;288:112954. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang C, Pan R, Wan X et al. A longitudinal study on the mental health of general population during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;87:40–48. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qiu J, Shen B, Zhao M, Wang Z, Xie B, Xu Y. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: implications and policy recommendations. Gen Psychiatr. 2020;33(02):e100213. doi: 10.1136/gpsych-2020-100213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang C, Pan R, Wan X et al. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(05):1729. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17051729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ahmed M Z, Ahmed O, Aibao Z, Hanbin S, Siyu L, Ahmad A. Epidemic of COVID-19 in China and associated Psychological Problems. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;51:102092. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou S J, Zhang L G, Wang L L et al. Prevalence and socio-demographic correlates of psychological health problems in Chinese adolescents during the outbreak of COVID-19. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020;29(06):749–758. doi: 10.1007/s00787-020-01541-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gao J, Zheng P, Jia Y et al. Mental health problems and social media exposure during COVID-19 outbreak. PLoS One. 2020;15(04):e0231924. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0231924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Verma S, Mishra A. Depression, anxiety, and stress and socio-demographic correlates among general Indian public during COVID-19. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2020;66(08):756–762. doi: 10.1177/0020764020934508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mazza C, Ricci E, Biondi S et al. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Italian people during the COVID-19 pandemic: Immediate psychological responses and associated factors. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(09):3165. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17093165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ozamiz-Etxebarria N, Dosil-Santamaria M, Picaza-Gorrochategui M, Idoiaga-Mondragon N. Stress, anxiety, and depression levels in the initial stage of the COVID-19 outbreak in a population sample in the northern Spain. Cad Saude Publica. 2020;36(04):e00054020. doi: 10.1590/0102-311X00054020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lei L, Huang X, Zhang S, Yang J, Yang L, Xu M. Comparison of prevalence and associated factors of anxiety and depression among people affected by versus people unaffected by quarantine during the COVID-19 epidemic in southwestern China. Med Sci Monit. 2020;26:e924609-1–e924609–12. doi: 10.12659/MSM.924609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roy D, Tripathy S, Kar S K, Sharma N, Verma S K, Kaushal V. Study of knowledge, attitude, anxiety & perceived mental healthcare need in Indian population during COVID-19 pandemic. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;51:102083. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou S J, Wang L L, Yang R et al. Sleep problems among Chinese adolescents and young adults during the coronavirus-2019 pandemic. Sleep Med. 2020;74:39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2020.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Holmes E A, O’Connor R C, Perry V H et al. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: a call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(06):547–560. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30168-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pappa S, Ntella V, Giannakas T, Giannakoulis V G, Papoutsi E, Katsaounou P. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;88:901–907. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fetzer T, Witte M, Hensel L et al. Global behaviors and perceptions in the COVID-19 pandemic. Natl Bureau Economic Res. 2020 doi: 10.31234/osf.io/3kfmh. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schneiderman N, Ironson G, Siegel S D. Stress and health: psychological, behavioral, and biological determinants. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2005;1:607–628. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Muscatell K A, Slavich G M, Monroe S M, Gotlib I H. Stressful life events, chronic difficulties, and the symptoms of clinical depression. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2009;197(03):154–160. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e318199f77b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lakhan R, Ekúndayò O T. Application of the ecological framework in depression: an approach whose time has come. AP J Psychol Med. 2013;14(02):103–109. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bavel J J, Baicker K, Boggio P S et al. Using social and behavioural science to support COVID-19 pandemic response. Nat Hum Behav. 2020;4(05):460–471. doi: 10.1038/s41562-020-0884-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cao W, Fang Z, Hou G et al. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Res. 2020;287:112934. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang Y, Ma Z F. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health and quality of life among local residents in Liaoning Province, China: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(07):2381. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17072381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moghanibashi-Mansourieh A. Assessing the anxiety level of Iranian general population during COVID-19 outbreak. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;51:102076. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]