Abstract

Background

Many cancer patients use additional herbs or supplements in combination with their anti-cancer therapy. Green tea—active ingredient epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG)—is one of the most commonly used dietary supplements among breast cancer patients. EGCG may alter the metabolism of tamoxifen. Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate the influence of green tea supplements on the pharmacokinetics of endoxifen; the most relevant active metabolite of tamoxifen.

Methods

In this single-center, randomized cross-over trial, effects of green tea capsules on endoxifen levels were evaluated. Patients treated with tamoxifen for at least 3 months were eligible for this study. After inclusion, patients were consecutively treated with tamoxifen monotherapy for 28 days and in combination with green tea supplements (1 g twice daily; containing 300 mg EGCG) for 14 days (or vice versa). Blood samples were collected on the last day of monotherapy or combination therapy. Area under the curve (AUC0–24h), maximum concentration (Cmax) and minimum concentration (Ctrough) were obtained from individual plasma concentration–time curves.

Results

No difference was found in geometric mean endoxifen AUC0–24h in the period with green tea versus tamoxifen monotherapy (− 0.4%; 95% CI − 8.6 to 8.5%; p = 0.92). Furthermore, no differences in Cmax (− 2.8%; − 10.6 to 5.6%; p = 0.47) nor Ctrough (1.2%; − 7.3 to 10.5%; p = 0.77) were found. Moreover, no severe toxicity was reported during the whole study period.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated the absence of a pharmacokinetic interaction between green tea supplements and tamoxifen. Therefore, the use of green tea by patients with tamoxifen does not have to be discouraged.

Keywords: Tamoxifen, Green tea extract, Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG), Herb–drug interaction, Pharmacokinetics, Toxicities, Breast cancer

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed type of cancer among women [1]. In the adjuvant treatment of hormone sensitive breast cancer, tamoxifen is the most frequently used and an effective oral endocrine therapy [2]. Many cancer patients—with estimates up to 80%—use complementary and alternative medicines in combination with their anti-cancer therapy [3–7]. One of the most popular herbal supplements among breast cancer patients are green tea (Camellia sinensis) supplements [4, 5, 8].

Green tea contains a large number of bioactive compounds, such as catechins and flavonoids [9, 10]. The active pharmacological ingredient of green tea is epigallocatechin-3-gallate, EGCG [11]. EGCG is believed to contribute to various cancer-preventive effects resulting from its high antioxidant potential [11–14]. In vitro and animal studies reported a number of cancer-preventative effects of EGCG including: attenuation of oxidative stress, inhibition of angiogenesis, induction of apoptosis and alterations in expression of cell cycle regulatory proteins [11, 12, 14–17]. None of these effects have been proven clinically. However, there are also signs that green tea and associated substances can influence other prescribed drugs. For example, it has been reported that EGCG could significantly reduce the systemic exposure of nadolol, folic acid and digoxin in subjects with approximately 85%, 39% and 31%, respectively [18–20]. Moreover, EGCG significantly increased the bioavailability of for example simvastatin and verapamil in rat studies [21, 22]. The described interactions with these drugs are the result of altered bioavailability or decreased metabolism, and can mechanistically be explained by inhibition of influx transporter organic anion transporter polypeptide (OATP) or efflux transporter P-glycoprotein and several phase I and II metabolizing enzymes (e.g., cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A and UDP-glucuronosyltransferase (UGT)) [18–27]. Simultaneous administration with green tea is therefore not recommended for these drugs. However, the impact of green tea on tamoxifen pharmacokinetics remains unclear.

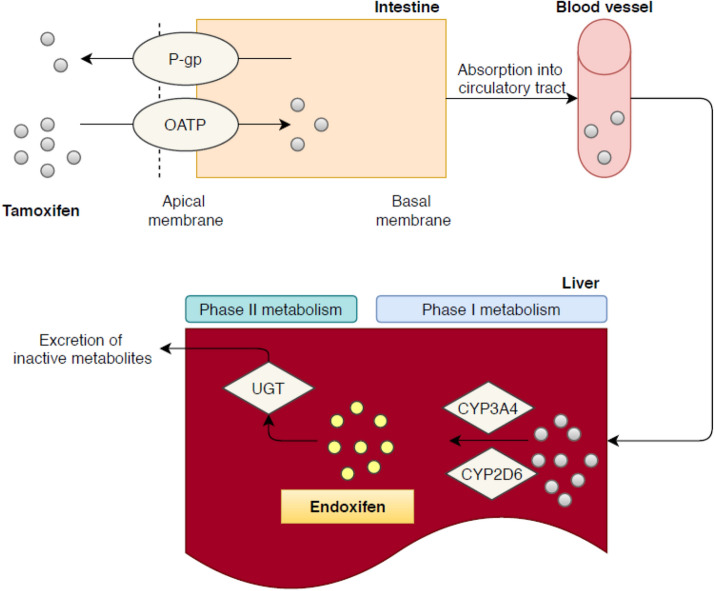

Tamoxifen pharmacokinetics depends on a multi-pathway biotransformation (Fig. 1) [28]. After hepatic uptake by—among others—OATP1B1, the cytochrome P450 iso-enzymes CYP2D6 and CYP3A4 metabolize tamoxifen into the main metabolite endoxifen [28–31]. Endoxifen is ultimately glucuronidated by UGT into an inactive metabolite and excreted through bile and feces [30]. In view of the involvement of drug transporting proteins and metabolizing enzymes, green tea could potentially interfere with the tamoxifen metabolism. Herb–drug interactions with tamoxifen could negatively impact the pharmacokinetic profile, as was previously shown with the combination of tamoxifen and curcumin [32]. Therefore, the primary objective of this study was to evaluate the possible pharmacokinetic interaction between green tea supplements and tamoxifen. The secondary objective was to assess the safety profile of green tea in combination with tamoxifen.

Fig. 1.

Main metabolism pathway of tamoxifen. After absorption tamoxifen is metabolized mainly by CYP2D6 in its active metabolite endoxifen. Tamoxifen relies on phase II metabolism before it can be excreted from the body. Endoxifen is ultimately glucuronidated into endoxifen-glucuronide mainly by UGTs. Several in vitro studies suggest inhibition by green tea of several phase I enzymes (CYP2D6 and CYP3A4) and inhibition of several drug-transporters which the efflux transporter P-gP (ABCB1) and sever influx-transporters like OATP. P-gP P-glycoprotein, CYP cytochrome P450, OATP organic anion transporting polypeptide, UGT UDP-glucuronosyltransferase

Methods

Study design

This single-center, randomized, two-armed, open-label, pharmacokinetic cross-over trial aimed to investigate the endoxifen exposure in breast cancer participants using tamoxifen with or without green tea. The study protocol was written in conformity with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Local Medical Ethics Committee and registered at the Netherlands Trial Registry (Number NL8144). Enrollment took place after written informed consent at the Erasmus University Medical Center, Rotterdam, The Netherlands. Patients with a confirmed histological or cytological diagnosis of primary breast cancer, a World Health Organization (WHO) performance status of ≤ 1 and on tamoxifen treatment at a stable dose of 20 or 40 mg q.d. for at least 3 months (ensuring steady-state concentration) were included. Participant demographics, medical history, CYP2D6 phenotype status and serum biochemistry were assessed before study entry. Participants were excluded if they were CYP2D6 poor or ultra-rapid metabolizers or if they had an impaired drug absorption. Furthermore, all participants were required to abstain from herbal or dietary supplements and strong inhibitors or inducers of CYP3A4, CYP2D6, UGT and P-glycoprotein. Depending on randomization, participants either started with tamoxifen monotherapy (20 or 40 mg q.d.; 10 AM) for 28 consecutive days or tamoxifen and green tea (1000 mg b.i.d.; containing 150 mg of EGCG; 10 AM and 10 PM) concomitantly for 14 consecutive days. This dose of green tea capsules is equivalent to approximately 5 to 6 cups of regular green tea and is also in line with previous clinical studies. Thereafter, participants received tamoxifen and green tea concomitantly for 14 consecutive days or tamoxifen monotherapy for 28 days, respectively. The green tea capsules were manufactured by a qualified Dutch Pharmacy (NatuurApotheek, Pijnacker, the Netherlands) and the batch was provided with a certificate of analysis for verification of the EGCG content. Participants were hospitalized for 24-h pharmacokinetic blood sampling on days 14 and 42, after one night of fasting. Blood samples were collected periodically at 13 predefined time points (t = 0, 0.5, 1.5, 2, 2.5, 3, 3.5, 4, 6, 8, 12 and 24 h after tamoxifen intake) and after processing to plasma stored at − 80 °C until analysis. Plasma samples were analyzed by a validated liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC–MS/MS) method in accordance with U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) bioanalytical method validation guidelines [33]. Adverse events were graded using the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 5.0 (CTCAEv.5, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Pharmacokinetic analysis

A non-compartmental pharmacokinetic analysis of steady-state concentrations was performed using Phoenix WinNonlin version 8.1 (Pharsight, a Certara Company, Princeton, NJ, USA). Main pharmacokinetic parameters including area under the curve (AUC0–24h), maximum observed concentration (Cmax) and minimum observed concentration (Ctrough) were constructed by individual plasma concentration–time curves.

Statistical analysis

The main objective of this trial was to compare the concentration of endoxifen with and without green tea supplements by comparing the AUC0–24h between days 14 and 42, where one comparison was made: endoxifen monotherapy versus combined with green tea supplements. A relative difference in AUC0–24h of at least 25% was considered to be clinically relevant and the within-patient deviation was assumed to be 20%. Given a power of 90% and a two-sided α of 5%, this resulted in a sample size of 14 evaluable patients (7 in both treatment arms). Analyses of AUC of tamoxifen, and Ctrough and Cmax of both endoxifen and tamoxifen were performed on log-transformed observations since these are assumed to follow a log-normal distribution. Estimates for the mean differences in Ctrough and Cmax were obtained for one comparison (tamoxifen concomitantly with green tea monotherapy versus tamoxifen monotherapy) separately using a linear mixed effect model treatment with sequence, and period as fixed effects and subject within sequence as a random effect. Variance components were estimated based on restricted maximum likelihood (REML) methods, and the Kenward–Roger method of computing the denominator degrees of freedom was used. The antilog were taken from the effect estimate and corresponding 95% confidence interval boundaries for the comparisons of tamoxifen concomitantly with green tea versus tamoxifen monotherapy to interpret the results (interpreted as ratios of the geometric means).

Results

Trial participants

Between October 2019 and February 2020, a total of 14 breast cancer patients were enrolled. All participants completed this trial and were evaluable. An overview of baseline characteristics is presented in Table 1. Participants were predominantly of Caucasian origin (86%) and were extensive metabolizers of CYP2D6 (79%). All participants were treated with adjuvant tamoxifen in this trial. The vast majority of patients used tamoxifen in a dose of 20 mg once daily (93%) and 1 patient used tamoxifen in a dose of 40 mg once daily (7%). In addition, the median duration of tamoxifen use before enrollment in this trial was 11.8 (range 6.0 to 12.9) months.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of evaluable participants (N = 14)

| Characteristic | N (%) or median (range) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Female | 14 (100%) |

| Male | 0 (0%) |

| Age (years) | 58.5 (50.8–68.3) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.4 (23.9–28.5) |

| WHO performance status | |

| 0 | 12 (86%) |

| 1 | 2 (14%) |

| Ethnic origin | |

| Caucasian | 12 (86%) |

| Afro-Caribbean | 2 (14%) |

| CYP2D6 phenotype | |

| EM | 11 (79%) |

| IM | 3 (21%) |

| Biochemistry | |

| AST (U/L) | 21 (17.8–27.0) |

| ALT (U/L) | 15 (11.8–21.0) |

| ALP (U/L) | 53.5 (43–67) |

| GGT (U/L) | 21 (16.5–29.5) |

| Total bilirubin (µmol/L) | 6 (5.3–8.5) |

| Albumin (g/L) | 36 (35–37) |

| LD (U/L) | 189 (181.5–196.5) |

| Hb (mmol/L) | 8.1 (7.7–8.3) |

| Creatinine (µmol/L) | 76.5 (71.8–87.3) |

| Previous treatment | |

| Surgery | 14 (100%) |

| Radiotherapy | 9 (64%) |

| Chemotherapy | 3 (21%) |

| Tamoxifen dose | |

| 20 mg | 13 (93%) |

| 40 mg | 1 (7%) |

| Duration of adjuvant tamoxifen use (months) | 11.8 (6.0–12.9) |

BMI body mass index, EM extensive metabolism, IM intermediate metabolism, AST aspartate aminotransferase, ALT alanine aminotransferase, ALP alkaline phosphatase, GGT gamma-glutamyltransferase, LD lactate dehydrogenase, Hb hemoglobin

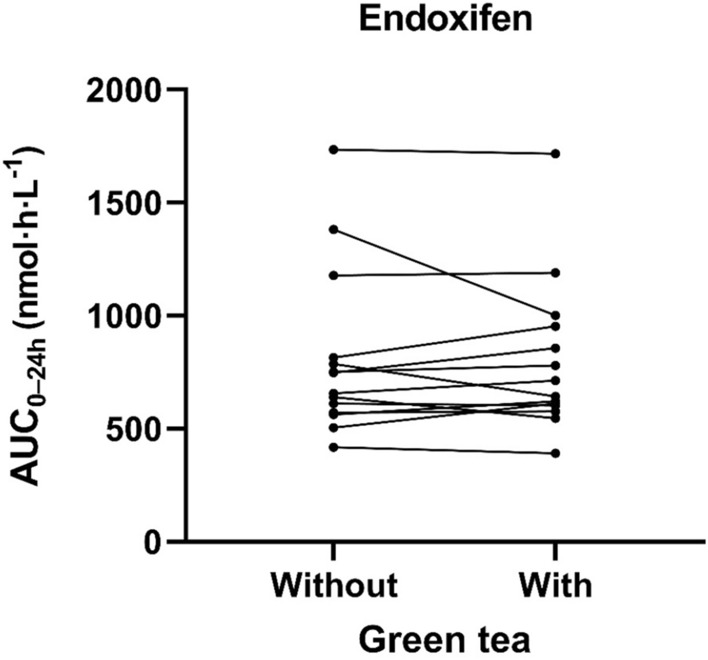

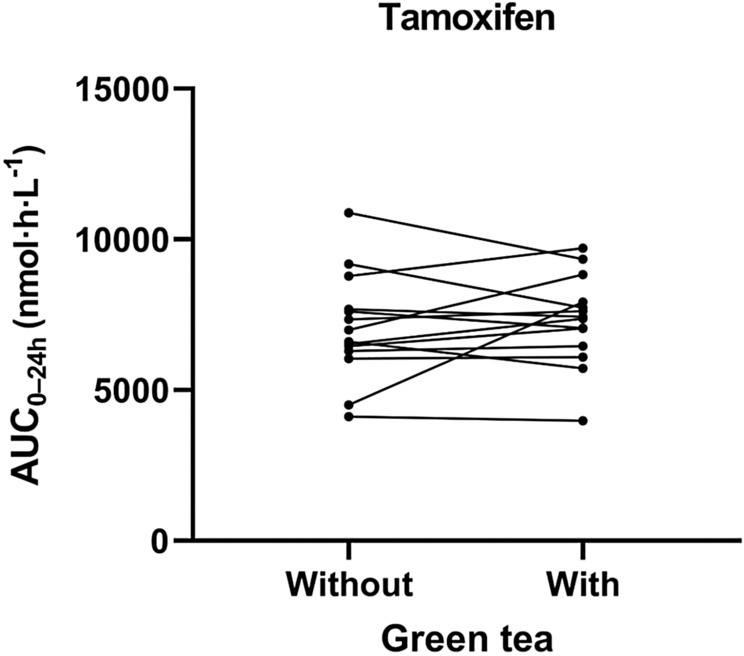

Pharmacokinetics

Tamoxifen and endoxifen levels were detectable in all collected blood samples. Estimates of main pharmacokinetic parameters for tamoxifen monotherapy versus tamoxifen with green tea supplements are presented in Table 2. The individual AUC values for endoxifen and tamoxifen exposure without and with green tea supplements are displayed in Figs. 2 and 3. The geometric mean of endoxifen AUC0–24h during concomitant administration of green tea was comparable to tamoxifen monotherapy [746 nmol h/L; coefficient of variation (CV): 38.6% vs 749 nmol h/L; CV 41.1%]. The corresponding relative difference (RD) in endoxifen AUC0–24h between the cycle with and without green tea was − 0.4% (95% CI − 8.6 to 8.5%; p = 0.92). Endoxifen geometric means of Cmax 38.5 nmol/L; CV 37.3% vs 39.6 nmol/L; CV 41.7% and Ctrough 32.2 nmol/L; CV 34.1% vs 31.9 nmol/L; CV 39.8% also did not significantly differ between with or without green tea.

Table 2.

Main pharmacokinetic parameters of tamoxifen and endoxifen

| PK parameters | Tamoxifen monotherapya | Tamoxifen with green teaa | p-value | Relative difference (%) (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endoxifen | ||||

| AUC0–24h (nmol·h/L) | 749 (41.1) | 746 (38.6) | 0.92 | − 0.4 (− 8.6 to 8.5) |

| Cmax (nmol/L) | 39.6 (41.7) | 38.5 (37.3) | 0.47 | − 2.8 (− 10.6 to 5.6) |

| Cmin (nmol/L) | 31.9 (39.8) | 32.2 (34.1) | 0.77 | 1.2 (− 7.3 to 10.5) |

| Tamoxifen | ||||

| AUC0–24h (nmol·h/L) | 6867 (26.1) | 7150 (22.9) | 0.44 | 4.1 (− 6.6 to 16.1) |

| Cmax (nmol/L) | 401.5 (28.1) | 392.6 (25.1) | 0.64 | − 2.2 (− 11.8 to 8.4) |

| Cmin (nmol/mL) | 257.1 (35.6) | 273.0 (24.4) | 0.34 | 6.2 (− 6.8 to 20.9) |

PK pharmacokinetic, CI confidence interval, AUC area under the plasma-concentration–time curve, Cmax maximum observed concentration, Cmin minimum observed concentration

aValues are geometric mean (% coefficient of variation)

Fig. 2.

Pharmacokinetics of endoxifen without and with concomitant green tea supplements

Fig. 3.

Pharmacokinetics of tamoxifen without and with concomitant green tea supplements

The plasma pharmacokinetic parameters of tamoxifen showed a clear resemblance in AUC0–24h with and without green tea (RD 4.1%, 95% CI − 6.6 to 16.1%; p = 0.44). Likewise, the determined relative difference of tamoxifen Cmax (RD − 2.2%, 95% CI − 11.8 to 8.4%; p = 0.64) and Ctrough (RD 6.2%, 95% CI − 6.8 to 20.9%; p = 0.34) also shared similar results between both treatments. No differences between CYP2D6 phenotype groups and endoxifen exposure were found.

Treatment-related adverse events

An overview of treatment-related adverse events is presented in Table 3. Headache, gastro-intestinal side-effects (e.g., constipation and dyspepsia) and polyuria were reported more often during the treatment with green tea vs tamoxifen monotherapy. A few changes in liver biochemical parameters (AST, ALT, GGT) occurred during administration with green tea, as well as a creatinine increase and platelet count decrease. Hot flashes were the most reported side-effects, but its occurrence count remained the same independent of green tea consumption. Adverse events were mild and serious adverse events (grade 3 or higher) were not observed during the study period.

Table 3.

Treatment-related adverse events, graded according to CTCAEv.5

| Adverse event | Tamoxifen monotherapy (N) | Tamoxifen with green tea (N) |

|---|---|---|

| Grade 1 | ||

| General | ||

| Abdominal pain | 2 | |

| Headache | 2 | 4 |

| Hot flashes | 5 | 5 |

| Restlessness | 1 | |

| Gastro-intestinal | ||

| Nausea | 1 | |

| Dyspepsia | 1 | |

| Gastroesophageal reflux | 1 | |

| Constipation | 1 | |

| Belching | 1 | |

| Bloating | 1 | |

| Urogenital | ||

| Polyuria | 3 | |

| Irregular menstruation | 1 | |

| Menorrhagia | 1 | 1 |

| Biochemistry | ||

| ASAT increased | 1 | |

| ALAT increased | 1 | |

| GGT increased | 1 | |

| Creatinine increased | 1 | |

| Platelet count decreased | 2 | |

| Grade ≥ 3 | 0 | 0 |

ASAT aspartate aminotransferase, ALAT alanine aminotransferase, GGT gamma-glutamyltransferase

Discussion

This randomized, cross-over, pharmacokinetic study clearly demonstrated that green tea supplements did not cause a pharmacokinetic interaction with tamoxifen or endoxifen in breast cancer patients. Therefore, we can conclude that tamoxifen absorption and metabolism were not affected by green tea from a pharmacokinetic point of view. Furthermore, serious or severe green tea related adverse events were not reported during the whole study period.

These results were unexpected as preclinical studies showed that green tea did modify important targets of tamoxifen metabolism (e.g., OATP, P-glycoprotein, UGT and CYP enzymes) [23, 25–27, 34]. Several mechanisms for drug interactions resulting in an altered bioavailability or metabolism have been reported, including inhibition of influx- or efflux-transporters and cytochrome P450 enzymes [18–22]. Furthermore, other green tea–drug combinations were previously studied in humans, and significant herb–drug interactions with clinical implications were found [18, 20]. Consequently, it was hypothesized that green tea would induce changes in the systemic exposure of tamoxifen and endoxifen, but no differences in endoxifen and tamoxifen exposure between the phase with and without green tea were found in this study.

The non-significant effect is not consistent with the outcomes of a study that reported EGCG (range 3 to 10 mg/kg) significantly altered the pharmacokinetic parameters of tamoxifen in rats [35]. This animal study suggested that EGCG might be effective to obstruct CYP3A4-mediated metabolism and P-glycoprotein mediated efflux pathways in the intestine and liver. However, a lower dose EGCG (0.5 mg/kg) did not significantly alter the metabolite formation of tamoxifen in rats [35]. This phenomenon suggests a dose-dependent effect of EGCG on the pharmacokinetic profile of tamoxifen. In this trial, the EGCG dose used is equivalent to a dose of approximately 4 mg/kg.

In this study a commercially available green tea extract was administered, in what is considered a high, but safe dose for humans (2000 mg green tea per day of which 300 mg is EGCG) and in line with dosages used in previous clinical studies and with what we observe in breast cancer patients in our out-patient clinic [10, 35–39]. This EGCG dose is equivalent to approximately about 5 to 6 cups of green tea. According to the European Food and Safety Association (European agency funded by the European Union) 300 mg EGCG is comparable to the maximum mean daily EGCG intake from the consumption of regular green tea in beverage form [38]. However, it is worth noting that routes of administration other than green tea supplements (e.g., green tea beverages) may in theory affect green tea absorption and bioavailability and therefore may affect tamoxifen pharmacokinetics. Therefore, it is possible that green tea beverages show a different bioavailability of EGCG compared with green tea capsules. However, a possible interaction with the green tea beverage is less likely since similar EGCG levels are likely to be obtained in human plasma. Apparently, administration of green tea capsules influences the phase II metabolism of tamoxifen to a very limited extend.

The main reported adverse events in this trial were headaches, hot flashes, gastro-intestinal toxicity, polyuria and minor abnormalities in liver biochemical parameters. The incidences of headache, polyuria, gastro-intestinal adverse events and minor liver biochemical disturbances were increased in the green tea phase, whereas abdominal pain was more present without green tea. All reported adverse events during this study were mild (grade 1). Previous studies found similar gastro-intestinal and hepatic adverse events related to the administration of high doses of green tea [36, 37, 40]. In addition, headache, polyuria and restlessness are well-known side-effects of caffeine, one of the substituents of green tea supplements (140 mg/day, equivalent to approximately 200 mL of filtered coffee). These green tea related adverse events suggest that green tea was sufficiently absorbed, which is important because of its low oral bioavailability [13, 41, 42]. To ensure adequate green tea absorption, we administered the daily dose in two dosages and patients with known impaired drug absorption were excluded.

In conclusion, this study clearly indicated that tamoxifen and endoxifen pharmacokinetics were not affected by green tea supplements. Concomitant treatment with green tea and tamoxifen was well-tolerated in this real-life breast cancer cohort. Therefore, the use of green tea among breast cancer patients does not have to be actively discouraged by physicians.

Funding

This study was performed without external funding.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Local Ethics Committee (Erasmus MC, Rotterdam; MEC 19-0581) and was registered in the Dutch Trial Registry (NL8144).

Footnotes

The original online version of this article was revised due to open access correction

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

C. Louwrens Braal and Koen. G. A. M. Hussaarts contributed equally to this work.

Change history

11/23/2020

Unfortunately, the original version of the article was published with incorrect copyright as “© Springer Science + Business Media, LLC, part of Springer Nature 2020”.

References

- 1.Bray F, et al. (2018) Global Cancer Statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (EBCTCG) Effects of chemotherapy and hormonal therapy for early breast cancer on recurrence and 15-year survival: an overview of the randomised trials. Lancet. 2005;365:1687–1717. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66544-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Horneber M, et al. How many cancer patients use complementary and alternative medicine: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Integr Cancer Ther. 2012;11:187–203. doi: 10.1177/1534735411423920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boon HS, Olatunde F, Zick SM. Trends in complementary/alternative medicine use by breast cancer survivors: comparing survey data from 1998 and 2005. BMC Womens Health. 2007;7:4. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-7-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Witt CM, Cardoso MJ. Complementary and integrative medicine for breast cancer patients—evidence based practical recommendations. Breast. 2016;28:37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2016.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mathijssen RHJ, Sparreboom A, Verweij J. Determining the optimal dose in the development of anticancer agents. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2014;11:272–281. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2014.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Veerman GDM, et al. Clinical implications of food–drug interactions with small-molecule kinase inhibitors. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:e265–e279. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30069-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Engdal S, Klepp O, Nilsen OG. Identification and exploration of herb–drug combinations used by cancer patients. Integr Cancer Ther. 2009;8:29–36. doi: 10.1177/1534735408330202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Graham HN. Green tea composition, consumption, and polyphenol chemistry. Prev Med. 1992;21:334–350. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(92)90041-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Balentine DA, Wiseman SA, Bouwens LC. The chemistry of tea flavonoids. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 1997;37:693–704. doi: 10.1080/10408399709527797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu JZ, Yeung SYV, Chang Q, Huang Y, Chen Z-Y. Comparison of antioxidant activity and bioavailability of tea epicatechins with their epimers. Br J Nutr. 2004;91:873–881. doi: 10.1079/BJN20031085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gormaz JG, Valls N, Sotomayor C, Turner T, Rodrigo R. Potential role of polyphenols in the prevention of cardiovascular diseases: molecular bases. Curr Med Chem. 2016;23:115–128. doi: 10.2174/0929867323666151127201732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ju J, Lu G, Lambert JD, Yang CS. Inhibition of carcinogenesis by tea constituents. Semin Cancer Biol. 2007;17:395–402. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2007.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miyata Y, Shida Y, Hakariya T, Sakai H. Anti-cancer effects of green tea polyphenols against prostate cancer. Molecules (Basel Switz) 2019;24:193. doi: 10.3390/molecules24010193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang CS, et al. Cancer prevention by tea: evidence from laboratory studies. Pharmacol Res. 2011;64:113–122. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schröder L, et al. Effects of green tea, matcha tea and their components epigallocatechin gallate and quercetin on MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 breast carcinoma cells. Oncol Rep. 2019;41:387–396. doi: 10.3892/or.2018.6789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bigelow RLH, Cardelli JA. The green tea catechins, (−)-Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) and (−)-Epicatechin-3-gallate (ECG), inhibit HGF/Met signaling in immortalized and tumorigenic breast epithelial cells. Oncogene. 2006;25:1922–1930. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Misaka S, et al. Green tea ingestion greatly reduces plasma concentrations of nadolol in healthy subjects. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2014;95:432–438. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2013.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim T-E, et al. Effect of green tea catechins on the pharmacokinetics of digoxin in humans. Drug Des Dev Ther. 2018;12:2139–2147. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S148257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alemdaroglu NC, Dietz U, Wolffram S, Spahn-Langguth H, Langguth P. Influence of green and black tea on folic acid pharmacokinetics in healthy volunteers: potential risk of diminished folic acid bioavailability. Biopharm Drug Dispos. 2008;29:335–348. doi: 10.1002/bdd.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Misaka S, et al. Green tea extract affects the cytochrome P450 3A activity and pharmacokinetics of simvastatin in rats. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2013;28:514–518. doi: 10.2133/dmpk.DMPK-13-NT-006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chung J-H, Choi D-H, Choi J-S. Effects of oral epigallocatechin gallate on the oral pharmacokinetics of verapamil in rats. Biopharm Drug Dispos. 2009;30:90–93. doi: 10.1002/bdd.644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Albassam AA, Markowitz JS. An appraisal of drug–drug interactions with green tea (Camellia sinensis) Planta Med. 2017;83:496–508. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-100934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Satoh T, Fujisawa H, Nakamura A, Takahashi N, Watanabe K. Inhibitory effects of eight green tea catechins on cytochrome P450 1A2, 2C9, 2D6, and 3A4 activities. J Pharm. 2016;19:188–197. doi: 10.18433/J3MS5C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nikaidou S, et al. Effect of components of green tea extracts, caffeine and catechins on hepatic drug metabolizing enzyme activities and mutagenic transformation of carcinogens. J Vet Res. 2005;52:185–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Farabegoli F, Papi A, Bartolini G, Ostan R, Orlandi M. (−)-Epigallocatechin-3-gallate downregulates Pg-P and BCRP in a tamoxifen resistant MCF-7 cell line. Phytomedicine. 2010;17:356–362. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Knop J, et al. Inhibitory effects of green tea and (−)-epigallocatechin gallate on transport by OATP1B1, OATP1B3, OCT1, OCT2, MATE1, MATE2-K and P-glycoprotein. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0139370. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0139370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jordan VC. New insights into the metabolism of tamoxifen and its role in the treatment and prevention of breast cancer. Steroids. 2007;72:829–842. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2007.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Del Re M, et al. Pharmacogenetics of CYP2D6 and tamoxifen therapy: light at the end of the tunnel? Pharmacol Res. 2016;107:398–406. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2016.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Binkhorst L, Mathijssen RHJ, Jager A, van Gelder T. Individualization of tamoxifen therapy: much more than just CYP2D6 genotyping. Cancer Treat Rev. 2015;41:289–299. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2015.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Binkhorst L, van Gelder T, Mathijssen RH. Individualization of tamoxifen treatment for breast carcinoma. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012;92(4):431–433. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2012.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hussaarts KGAM, et al. Impact of curcumin (with or without piperine) on the pharmacokinetics of tamoxifen. Cancers (Basel) 2019;11:403. doi: 10.3390/cancers11030403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Food and Drug Administration (FDA) guideline. Bioanalytical method validation guidance for industry. 44 (2018). https://www.fda.gov/files/drugs/published/Bioanalytical-Method-Validation-Guidance-for-Industry.pdf

- 34.Qian F, Wei D, Zhang Q, Yang S. Modulation of P-glycoprotein function and reversal of multidrug resistance by (−)-epigallocatechin gallate in human cancer cells. Biomed Pharmacother. 2005;59:64–69. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shin S-C, Choi J-S. Effects of epigallocatechin gallate on the oral bioavailability and pharmacokinetics of tamoxifen and its main metabolite, 4-hydroxytamoxifen, in rats. Anticancer Drugs. 2009;20:584–588. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0b013e32832d6834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hu J, Webster D, Cao J, Shao A. The safety of green tea and green tea extract consumption in adults—results of a systematic review. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2018;95:412–433. doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2018.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Crew KD, et al. Phase IB randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, dose escalation study of polyphenon E in women with hormone receptor-negative breast cancer. Cancer Prev Res. 2012;5:1144–1154. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-12-0117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.European Food Safety Agency (EFSA) Scientific Opinion on the safety of green tea catechins—2018. https://www.efsa.europa.eu/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Stingl JC, et al. Protocol for minimizing the risk of metachronous adenomas of the colorectum with green tea extract (MIRACLE): a randomised controlled trial of green tea extract versus placebo for nutriprevention of metachronous colon adenomas in the elderly population. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:360. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bonkovsky HL. Hepatotoxicity associated with supplements containing Chinese green tea (Camellia sinensis) Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:68–71. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-1-200601030-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scholl C, et al. Population nutrikinetics of green tea extract. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0193074. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0193074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee M-J, et al. Pharmacokinetics of tea catechins after ingestion of green tea and (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate by humans: formation of different metabolites and individual variability. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2002;11:1025–1032. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]