Abstract

According to previous studies in Lorestan Province, western Iran on human fascioliasis, we aimed to understand the epidemiology of the disease and to identify the cases in rural and nomad regions of this province. The studied population was a rural and nomadic population of nine districts of Lorestan province, of which 1053 were selected according to the population of each studied county based on random sampling in 2016–2017. Initially, a questionnaire was completed for each person, including age, gender, education, occupation, use of local native aquatic plants and history of travel to the northern provinces of the country where fasciolosis has been reported mostly. Then, 5 ml blood samples were taken and the samples were evaluated as for anti-Fasciola specific antibodies using ELISA technique. Overall, 1053 individuals were participated, of which 28 (2.66%) were infected with fasciolosis and 18 positive cases were female. The highest infection rate was in the age group of 20–29 years (23%) followed by 30–39 years of age (22%). There was no significant difference between the rate of infection in terms of gender (P = 0.89), age (P = 0.15), travel history to the northern provinces of the country (P = 0.089), history of aquatic plant consumption called Balmak natively (P = 0.48), history of surface water consumption (springs, streams) (P = 0.18), and occupation (P = 0.43). Considering the results of current and previous studies it seems that the disease in the Lorestan province is expanding and new foci in different parts of the province are formed or are being formed. Therefore, the preventive measures, control and treatment should be taken in areas with parasites transmission.

Keywords: Seroepidemiology, Fascioliasis, Freshwater vegetable, Iran

Introduction

Fascioliasis is a zoonosis disease that has been reported in five continents (Mas-Coma 2005). It affects domestic animals (cattle, sheep, and goats) that are in close contact with humans, important in veterinary medicine and transmittable to humans, therefore, it is important in terms of the health and prevention of contagious diseases, and unfortunately, it is rising across the world (Mas-Coma et al. 2009). The disease has emerged or re-emerged in some parts of the world, due to human activity (Sabourin et al. 2018). Irrigation systems, management, and maintenance of domestic animals, human nutrition, and public health habits and behaviors have affected the incidence of disease (Sabourin et al. 2018).The main transmitting ways of the disease to the main hosts include eating water plants, or drinking polluted water within a stage of the life cycle of the parasite, called metacercariae, which clings to watery plants or exists at the surface of the water (Hurtrez-boussès 2001). It is estimated that 17 million people are affected by the disease all over the world (Valero et al. 2009). However, the disease seems to have numerous cases in many countries, especially in Africa and Asia (Mas-Coma 2005). The more real numbers of people suffering from the disease are between 35 and 72 million people, with over 180 million at-risk people (Nyindo and Lukambagire 2015).

Recently Iran has been included by WHO among six countries with serious problems with fascioliasis (WHO 2007; Rokni et al. 2014). In recent years the cases of disease in some provinces has been increased and new foci of disease has been reported from some provinces (Ashrafi 2015). Different rates of polluted livestock (cattle, sheep, buffalos and goats) with fascioliasis have been reported from 27 provinces of Iran (Ashrafi 2015).

Fascioliasis is an emerged or re-emerged disease in Gilan province of northern Iran near Caspian sea and some other provinces of Iran (Ashrafi et al. 2015; Parhizgari et al. 2017) and is endemic in the Mazandaran province of northern Iran (Moghaddam et al. 2004; Amor et al. 2011; Parhizgari et al. 2017). First and biggest epidemic of human fascioliasis in the world with 10,000 positive cases has been reported from Gilan province, northern Iran at 1989 (Massoud 1989; Asmar et al. 1991). Second epidemic of human fascioliasis with 5000 positive cases has been reported from the same province 10 years later (Massoud 1989; Asmar et al. 1991). Some cases of disease have been reported in other provinces of Iran, such as Ardabil (Asadian et al. 2013), Kermanshah (Hatami et al. 2012), Ilam (Abdi et al. 2013), Kohgiluyeh and Boyerahmad (Sarkari et al. 2012) and Isfahan (Saberinasab et al. 2014).

In a study that have been carried out in Lorestan province, west of Iran, 2.6% of sheep and goats and 2.8% of cattle have been reported as positive to fascioliasis (Sabzvarinezjad 2007). Two previous studies, reported positive cases of human fascioliasis in Lorestan province (Kheirandish et al. 2016; Heydarian et al. 2017).

According to previous studies in Lorestan province (Sabzvarinezjad 2007; Kheirandish et al. 2016; Heydarian et al. 2017) and some reports regarding human infection with fascioliasis, this study aimed to understand the epidemiology of the disease well and to identify the cases in other counties of province.

Materials and methods

The studied population and serum blood preparation

The Lorestan province with a population of 1,800,000 people is located in western Iran. The studied population was a rural and nomadic population of nine districts of Lorestan province, of which 1053 were selected according to the population of each studied county based on random sampling.

The sample size was estimated by the following equation:

In this study we considered the P as the expected prevalence of the fasciolosis (2%) in the general population (1), d as ¼ of P and Z(1−a/2) = 1.98. Accordingly, 1700 sample size was calculated which finally 1053 people were recruited for the study. We used a multistage random sampling in which we listed all of the provincial villages of all districts and selected a number of these villages randomly. Finally in each selected village we selected recruited people from the raster which is available in each health house located in that village by simple random sampling.

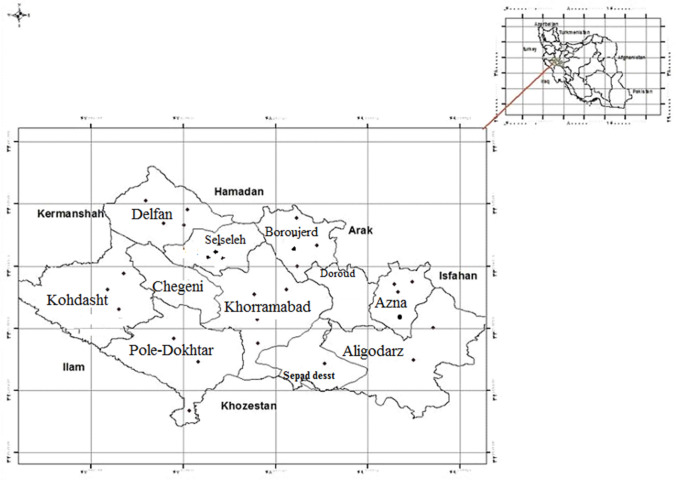

Considering the sample size, nine county of Lorestan province were selected as a cluster and the samples number was determined based on the population of each county. Then, in each region of the province at least three villages and three nomadic areas with either a stream or running water or a spring with vegetation were randomly selected (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Geographical distribution of positive cases of fascioliasis between counties, Lorestan province, Iran

All the necessary explanations were provided to the subjects who signed a written consent form. About the children, the written consent form was signed by their parents after providing the explanations. This research was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Lorestan University of Medical Sciences and informed consent from the legally authorized representatives of participants have been provided.

Initially, a questionnaire was completed for each person, including age, gender, education, occupation, use of local native aquatic plants (Nasturtium officinalis, local native name: Balmak) and history of travel to the northern provinces of the country. Then, the 5 cc blood samples were taken and the samples were sent to a parasitological laboratory, School of Public Health, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, to evaluate anti- fasciola specific antibodies using ELISA technique. The ELISA kite was purchased from Pishtaz Medical Co. and then the antigen prepared by the Tehran University of Medical Sciences was used to perform ELISA. The suspicious and positive samples were checked for confirmation and re-check. After obtaining the results, those with a positive serologic test result were evaluated clinically and paraclinically.

ELISA test method, serologic methods

100 μL of antigen was added to each well of the ELISA plate.

The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 1 h and then incubated in a refrigerator overnight.

200 μL of BSA 2% was dispensed to plates.

The plates were evacuated and washed with PBS/Tween 20 solution three times for each plate.

The patient’s serum was added to wells at 100 μL with appropriate dilution (1:250) and incubation was performed for 30 min at 37 °C.

Sera of a human positive to fascioliasis and an individual not infected to fascioliasis were tested in parallel, as positive and negative controls, respectively.

Rewashing was performed for five times with PBS/Tween 20 solution.

Anti-human IgG-HRP conjugate was added at 100 μL with appropriate dilution (1:10,000) and the incubation was performed with the above conditions (30 min at 37 °C).

The rewashing was performed for five times.

The OPD substrate was added to the wells in 100 μL and was placed at the room temperature for 10 min in the dark.

The reaction was completed by adding 50 μL of normal 0.1 sulfuric acid (12.5% H2SO).

The results were read by the ELISA reader at 492 nm and the positive samples were determined after the cut-off (Rokni et al. 2002).

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using descriptive statistics (ratios, frequency, mean, and standard deviation), and Chi square test or Fisher’s exact test was used to compare the positive serological frequency between the subgroups. P values < 0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

Results

According to the results, in this study, 1053 individuals, including 750 women (71.23%) and 303 men (28.77%) were participated, of which 28 (2.66%) were infected with Fasciola, 18 were positive women and 10 were positive men. Cut-off point for ELISA was 0.32 (mean ± 3 SD). The highest infection was in the age group 20–29 years (23%) and 30–39 years (22%) (Table 1). The most positive cases were in Azna (6.45%) and Khorramabad (6.35%), respectively (Table 2). In terms of local vegetable consumption, 18 people were infected with Fasciola from those who ate all kinds of local herbs, and 10 people were infected with Fasciola using only local name Balmak. In terms of literacy, the most contaminated ones were 11 illiterate people. In terms of tourist areas, the areas in traditional restaurants located along or at the edge of the recreational and tourist sites, consuming Balmak along with their meals, such as the Tunnel Barfi (snow Tunnel) in Azna, Bisheh Waterfall in Khorramabad, the recreational of Venaei in Boroujerd, with 6.45%, 6.34% and 5.12% had the highest contamination respectively (Table 3).

Table 1.

Percentage of positive cases of fascioliasis in Lorestan province, Iran, according to age groups

| Age groups (years) | Total nos. | Percentage of positive cases |

|---|---|---|

| ≤ 10 | 5 | 0 |

| 11–19 | 75 | 7 |

| 20–29 | 242 | 23 |

| 30–39 | 238 | 22 |

| 40–49 | 206 | 20 |

| 50–59 | 138 | 13 |

| 60–69 | 84 | 8 |

| 70–79 | 48 | 5 |

| ≥ 80 | 17 | 2 |

| Total | 1053 | 100 |

Table 2.

Seropositivity rate of fascioliasis according to counties of Lorestan province, Iran

| County | Kuhdasht | Azna | Aligudarz | Borujerd | Pol-e-Dokhtar | Khorramabad | Delfan | Sepid dasht | Selseleh (Aleshtar) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seropositivity rate (%) | 1.60 | 6.45 | 2.56 | 1.41 | 3.70 | 6.35 | 3.20 | 0.90 | 4.76 |

Table 3.

Seropositivity rate of fascioliasis according to recreational and tourism areas of the Lorestan province, Iran

| County | Kuhdasht | Azna | Borujerd | Pol-e-Dokhtar | Khorramabad | Selseleh (Aleshtar) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tourist site | Shirraz valley | Snow tunnel | Venaei | Lakes | Bisheh Waterfall | Kahman |

| Seropositivity rate (%) | 1.61 | 6.45 | 5.12 | 3.70 | 6.34 | 4.74 |

There was no significant difference between the amount of infection in males and females (P = 0.89), in terms of the age (P = 0.15), travel history to the northern provinces of the country (P = 0.089), history of aquatic plant consumption called Balmak natively (P = 0.48), history of surface water consumption (springs, streams) (P = 0.18), and occupation (P = 0.43).

Discussion

Considering that the phases of the life cycle of the parasite are in the water and the disease is zoonotic, the domesticated livestock are affected, and the eggs of the parasite are present in their feces, hence, the water resources and aquatic plants near the villages are contaminated with the parasite eggs and metacercariae phase easily and by consuming water and the aquatic plants infested with metacercariae, the humans and animals become infected with fascioliasis. Consequently, in Iran, the disease is prevalent and transferred in the provinces and areas with abundant water sources located near the villages, in the northern provinces of the country (Gilan, Mazandaran, and Golestan) (Forghan-parast et al. 1993; Ashrafi et al. 2015; Forghan et al. 2015; Parhizgari et al. 2017) and the western and southwestern provinces of the country, which have more abundant water resources than other provinces, the cases were reported and studied (Asadian et al. 2013; Hatami et al. 2012; Sarkari et al. 2012; Abdi et al. 2013; Saberinasab et al. 2014).

This is the second comprehensive seroepidemiological study conducted in 9 counties of Lorestan province. The first fascioliasis case in the province of Lorestan was reported by Kheirandish et al. (2016), in Pirabad, Dorood county (Kheirandish et al. 2016). Then, another extensive study was performed by Heydarian et al. (2017) in 2015–2016 in 10 counties of Lorestan province. The present study is the second largest seroepidemiological study in Lorestan province that was carried out in 2017.

In the previous study (Heydarian et al. 2017), the target population were people that live in rural and urban areas of 10 counties of Lorestan province and the prevalence rate was 1.3% (1.9% in rural and 0.4% in urban) comparing with 2.66% in the current study, that the studied population was a rural and nomadic population of 9 districts of Lorestan province (Heydarian et al. 2017). In both studies, there was no significant difference between the prevalence rates in males and females, which is consistent with the similar studies in our country and other countries (Esteban et al. 1997; O’Neill et al. 1998; Kaplan et al. 2002; Moghaddam et al. 2004; Asadian et al. 2013; Hatami et al. 2012; Sarkari et al. 2012; Abdi et al. 2013; Ashrafi et al. 2015). However, there was significant difference between males and females in the first outbreak of disease in Gilan province (Asmar et al. 1991; Forghan-parast et al. 1993; Ashrafi et al. 2015). Also, there was similar results in studies that were carried out in Egypt with the Gilan study and incidence of disease in women was significantly more than men in Egypt (Esteban et al. 2003; Ashrafi 2015).

The highest prevalence in the province in the previous study was reported in people over 60 years old (Heydarian et al. 2017), while the highest prevalence in this study was in people between the ages of 20 and 49 years, which is more consistent with the studies conducted in Kermanshah and Gilan reporting the highest prevalence rates in the ages between 10 and 29 years (Asmar et al. 1991; Hatami et al. 2012; Ashrafi et al. 2015). Generally, in Iran, fascioliasis is more prevalent among adults, rather children, and perhaps one of its reasons is the high consumption the aquatic plant by the adults, which is the main route of transmission to humans.

Using raw aquatic plants as the food is an important factor in the disease transmission to humans in Iran. Usually, these plants are not washed and not disinfected well by the villagers. After harvesting the plants in clean and clear water springs and streams, it seems that the plant is clean, the secondary washing is not done, and the metacercarias are eaten easily with the plant.

In the present study, 10 out of 18 people with fascioliasis noted that they used the aquatic plant called Balmak. Particularly, in recreational and tourism areas of the province with abundant water resources such as the Tunnel Barfi in Azna, the Bisheh waterfall in Khorramabad and the village of Vanei in Boroujerd, where the consumption of Balmak is more than the other areas, the prevalence rate of disease is higher. However, this difference in prevalence with the other areas is not significant. While, in the previous studies, there was a significant difference between the use of Balmak with the prevalence of disease in the province (Kheirandish et al. 2016; Heydarian et al. 2017).

In other regions of Iran, there is a correlation between the use of raw aquatic and semi-aquatic plants and the prevalence of fascioliasis (Salahi 2009; Salahimoghaddam et al. 2009). However, in studies in other regions of Iran consistent with our study, there was no significant relationship between the use of aquatic and semi-aquatic plants and the prevalence of fascioliasis (Asadian et al. 2013; Ashrafi et al. 2015; Manouchehri Naeini et al. 2016).

The main problem and limitation of the study was non-participation of nomads and rural people in the blood sampling. It is essential to distribute posters, training pamphlets and animations to promote the awareness and knowledge of nomads and rural people.

Conclusion

Considering the results of current and previous studies it seems that the disease in the Lorestan province is expanding and new foci in different parts of the province are formed or are being formed. Therefore, the preventive measures, control and treatment should be taken in areas with parasites transmission, most notably is the training the native people especially in rural areas, regarding the ways of transmission of parasites to humans, non-consumption of Balmak and surface water, and washing and disinfection of Balmak and other edible vegetables before consuming. The domestic animals should be avoided contacting with water resources, sanitary water should be provided to the villagers and the affected people should be treated.

Although the findings of the study do not determine the main pattern of the disease transmission, it can be stated that those who are using the raw traditional vegetable, especially Balmak, are more likely to develop the disease.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Infectious Diseases Management Center of Ministry of Health and Medical Education, Department of Water and Food-Transmitted Diseases of Ministry of Health, who supported the project financially, in addition, the Parasitology Department, School of Public Health, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, who carried out the experiments on project samples.

Author’s contribution

BE, MBR, FK and MHK proposed and designed the study. HM, MM and AM collaborated in field work and sample collection. MBR, HM, AM and MM help in technical and laboratory work. BE, FK and MHK collaborated in statistical analysis. HM and MHK wrote the manuscript. BE, MBR, FK, MM and AM revised the manuscript. All the authors approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The present study was funded by the Infectious Diseases Management Center of Ministry of Health and Medical Education, Department of Water and Food-Transmitted Diseases of Iranian Ministry of Health and Medical Education.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Informed consent

All the necessary explanations were provided to the subjects who signed a written consent form. About the children, the written consent form was signed by their parents after providing the explanations. This research was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Lorestan University of Medical Sciences, Khorramabad, Iran.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Abdi J, Naserifar R, Rostami Nejad M, et al. New features of fascioliasis in human and animal infections in Ilam Province, western Iran. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench. 2013;6(3):152–155. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amor N, Halajian A, Farjallah S, Merella P, Said K, Ben Slimane B. Molecular characterization of Fasciola spp. from the endemic area of northern Iran based on nuclear ribosomal DNA sequences. Exp Parasitol. 2011;128:196–204. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2011.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asadian S, Mohebali M, Mahmoudi M, Eshrat Beigom KIA, Heidari Z, Asgari M, Aryaeipour M, Moradi S, Rokni MB. Seroprevalence of human fascioliasis in Meshkin-Shahr District, Ardabil Province, northwestern Iran in 2012. Iran J Parasitol. 2013;8(4):516–521. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashrafi K. The status of human and animal fascioliasis in Iran: a narrative review article. Iran J Parasitol. 2015;10(3):306–328. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashrafi K, Saadat F, O’Neill S, Rahmati B, Amin Tahmasbi H, Pius Dalton J, Nadim A, Asadinezhad M, Rezvani SM. The endemicity of human fascioliasis in Guilan Province, Northern Iran: the baseline for implementation of control strategies. Iran J Pub Heal. 2015;44(4):501–511. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asmar M, Milaninia A, Amir-Khani A, Yadegari D, Forghan-Parast K, Nahrava-nian H, Piazak N, Esmaeili A, Hovanesian A, Valadkhani Z. Seroepidemiological investigation of fascioliasis in northern Iran. Med J Islamic Rep Iran. 1991;5(1–2):23–27. [Google Scholar]

- Esteban JG, Flores A, Aguirre C, et al. Presence of very high prevalence and intensity of infection with Fasciola hepatica among aymara children from the northern Bolivian Altiplano. Act Trop. 1997;66(1):1–14. doi: 10.1016/s0001-706x(97)00669-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esteban JG, Gonzalez C, Curtale F, Munoz-Antoli C, Valero MA, Bargues MD, El Sayed M, El Wakeel A, Abdel-Wahab Y, Montresor A, Engels D, Savioli L, Mas-Coma S. Hyperendemic fascioliasis associ-ated with schistosomiasis in villages in the Nile Delta of Egypt. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2003;69(4):429–437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forghan PK, Yadegari D, Asmar M. Study of clinical epidemiology of fascioliasis in Guilan. Iran J Pub Heal. 2015;44(4):501–511. [Google Scholar]

- Forghan-Parast K, Yadegari D, Asmar M. Clinical epidemiology of human fascioliasis in Gilan. J Guilan Uni Med Sci. 1993;2:6–7. [Google Scholar]

- Hatami H, Asmar M, Masoud J, et al. The first epidemic and new-emerging human fascioliasis in Kermanshah (western Iran) and a ten-year follow up, 1998–2008. Int J Pre Med. 2012;3(4):266–272. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heydarian P, Ashrafi K, Mohebali M, Eshrat Beigom KIA, Aryaeipour M, Chegeni Sharafi A, Mokhayeri H, Bozorgomid A, Rokni MB. Seroprevalence of human fasciolosis in Lorestan province, western Iran, in 2015–2016. Iran J Parasitol. 2017;12(3):389–397. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurtrez-boussès S. Dynamics of host–parasite interactions: the example of population biology of the liver fluke (Fasciola hepatica) Microb Inf. 2001;3:841–849. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(01)01442-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan MA, Kuk SA, Kalkan AB, Demirdaǧ KB, Özdarendeli AC. Investigation of Fasciola hepatica seroprevalence in Elazig Region. Mikrobiyoloji Bulteni. 2002;36(3–4):337–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kheirandish F, Kayedi MH, Ezatpour B, Anbari K, Karimi Rouzbahani HR, Chegeni Sharafi A, Zendehdel A, Bizhani N, Rokni MB. Seroprevalence of human fasciolosis in Pirabad, Lorestan Province, western Iran. Iran J Parasitol. 2016;11(1):24–29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manouchehri Naeini K, Mohammad Nasiri K, Rokni MB, Kheiri S. Seroprevalence of human fascioliasis in Chaharmahal and Bakhtiyari province, southwestern Iran. Iran J Pub Heal. 2016;45(6):774–780. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mas-Coma S. Epidemiology of fascioliasis in human endemic areas. J Helm. 2005;79(3):207–216. doi: 10.1079/joh2005296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mas-Coma S, Valero MA, Bargues MD. Fasciola, lymnaeids and human fascioliasis, with a global overview on disease transmission, epidemiology, evolutionary genetics, molecular epidemiology and control. Adv Parasitol. 2009;69:41–146. doi: 10.1016/S0065-308X(09)69002-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massoud J. Fascioliasis outbreak in man and drug test (Triclabendazole) in Caspian Sea Littoral, Northern part of Iran. Bull Soc France Parasitol. 1989;8(S1):438–439. [Google Scholar]

- Moghaddam AS, Massoud J, Mahmoodi MA, Mahvi AH, Periago MV, Artigas P, Fuentes MV, Bargues MD, Mas-Coma S. Human and animal fascioliasis in Mazandaran Province, northern Iran. Parasito Res. 2004;94(1):61–69. doi: 10.1007/s00436-004-1169-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyindo M, Lukambagire AH. Fascioliasis: an ongoing zoonotic trematode infection. Biomed Res Int. 2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/786195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill SM, Parkinson M, Strauss W, Angles R, Dalton JP. Immunodiagnosis of Fasciola hepatica infection (fascioliasis) in a human population in the Bolivian Altiplano using purified cathepsin l cysteine proteinase. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1998;58(4):417–423. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1998.58.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parhizgari N, Gouya MM, Mostafavi E. Emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases in Iran. Iran J Microbiol. 2017;9(3):122–142. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rokni MB, Massoud J, O’Neill SM, Parkinson M, Dalton JP. Diagnosis of human fasciolosis in the Gilan province of northern Iran: application of cathepsin l-ELISA. Diagnostic Microbiol Infect Dis. 2002;44(2):175–179. doi: 10.1016/s0732-8893(02)00431-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rokni MB, Lotfy WM, Ashrafi K, Murrell KD (2014) Fasciolosis in the MENA Region. In: Neglected tropical diseases-Middle East and North Africa. Springer, Vienna, pp 59–90

- Saberinasab M, Mohebali M, Molawi G, Eshrat Beigom KIA, Aryaeipour M, Rokni MB. Seroprevalence of human fascioliasis using indirect ELISA in Isfahan district, central Iran in 2013. Iran J Parasitol. 2014;9(4):461–465. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabourin E, Alda P, Vazquez A, Hurtrez-Bousses S, Vittecoq M. Impact of human activities on fasciolosis transmission. Trends Parasitol. 2018;34(10):891–903. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2018.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabzvarinezjad G. Prevalence of zoonotic liver trematodes in slaughtered animals in Khoramabad slaughterehouse. J Lorestan Univ Med Sci. 2007;6(22):51–54. [Google Scholar]

- Salahi MA. Epidemiology of human fascioliasis in Iran. J Arch Military Med. 2009;1(1):6–12. [Google Scholar]

- Salahimoghaddam A, Pedram M, Fathi A. Epidemiology of human fasciolosis in Iran. J Kerman Uni Med Sci. 2009;16(4):358–398. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkari B, Ghobakhloo N, Moshfea AA, Eilami O. Seroprevalence of human fasciolosis in a new-emerging focus of fasciolosis in Yasuj district, southwest of Iran. Iran J Parasitol. 2012;7(2):15–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valero MA, Perez-Cresgo I, Periago MV, Khoubbane M, Mas-Coma S. Fluke egg characteristics for the diagnosis of human and animal fascioliasis by Fasciola hepatica and F. gigantica. Act Trop. 2009;111(2):150–159. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization The “ne-glected” neglected worms. Action against Worms. WHO Rep. 2007;10:1–8. [Google Scholar]