Abstract

Background and aims

The stable carbon isotope ratio of leaf dry matter (δ 13Cp) is generally a reliable recorder of intrinsic water-use efficiency in C3 plants. Here, we investigated a previously reported pattern of developmental change in leaf δ 13Cp during leaf expansion, whereby emerging leaves are initially 13C-enriched compared to mature leaves on the same plant, with their δ 13Cp decreasing during leaf expansion until they eventually take on the δ 13Cp of other mature leaves.

Methods

We compiled data to test whether the difference between mature and young leaf δ 13Cp differs between temperate and tropical species, or between deciduous and evergreen species. We also tested whether the developmental change in δ 13Cp is indicative of a concomitant change in intrinsic water-use efficiency. To gain further insight, we made online measurements of 13C discrimination (∆ 13C) in young and mature leaves.

Key Results

We found that the δ 13Cp difference between mature and young leaves was significantly larger for deciduous than for evergreen species (−2.1 ‰ vs. −1.4 ‰, respectively). Counter to expectation based on the change in δ 13Cp, intrinsic water-use efficiency did not decrease between young and mature leaves; rather, it did the opposite. The ratio of intercellular to ambient CO2 concentrations (ci/ca) was significantly higher in young than in mature leaves (0.86 vs. 0.72, respectively), corresponding to lower intrinsic water-use efficiency. Accordingly, instantaneous ∆ 13C was also higher in young than in mature leaves. Elevated ci/ca and ∆ 13C in young leaves resulted from a combination of low photosynthetic capacity and high day respiration rates.

Conclusion

The decline in leaf δ 13Cp during leaf expansion appears to reflect the addition of the expanding leaf’s own 13C-depleted photosynthetic carbon to that imported from outside the leaf as the leaf develops. This mixing of carbon sources results in an unusual case of isotopic deception: less negative δ 13Cp in young leaves belies their low intrinsic water-use efficiency.

Keywords: Carbon isotope ratio, intercellular CO2 concentration, leaf development, water-use efficiency

INTRODUCTION

Leaf demography can play an important role in controlling canopy gas exchange in both deciduous and evergreen forest trees (Beringer et al., 2015; Wu et al., 2016, 2017). When young leaves emerge, they typically have negative or low photosynthetic rates, which then increase as the photosynthetic apparatus matures (Choinski et al., 2003; Cernusak et al., 2006, 2009a). Leaf expansion and development also probably involve changes in water-use efficiency, and understanding such changes could be helpful for understanding how forests will respond to climate change, especially where the response involves changes in leaf demography and/or phenology (Wu et al., 2016; Cernusak, 2020).

Measurements of stable carbon isotope ratios in leaf dry matter (δ 13Cp) provide a valuable tool for assessing variation in water-use efficiency in C3 plants (Farquhar and Richards, 1984). Such measurements have been used to assess water-use efficiency variation among crop cultivars (Richards et al., 2002; Rebetzke et al., 2008), among species of wild plants (Marshall and Zhang, 1994; Cernusak et al., 2007) and among functional groups with different ecological strategies (Brooks et al., 1997; Guehl et al., 2004). The association between leaf δ 13Cp and water-use efficiency derives from the relationship between discrimination against 13C during photosynthetic CO2 assimilation (∆ 13C) and the ratio of the intercellular to ambient CO2 concentrations (ci/ca) (Farquhar et al., 1982b; Farquhar and Richards, 1984). In the simplest form, the model relating ∆ 13C to ci/ca can be expressed as:

| (1) |

where as is the 13C/12C fractionation during diffusion through the stomatal pore (4.4 ‰) and is discrimination against 13CO2 by carboxylating enzymes. Equation (1) can also be written for the δ 13C of plant tissue (δ 13Cp), such that:

| (2) |

where δ 13Ca is the δ 13C of CO2 in air surrounding the plant. The link to water-use efficiency comes about through the term ci/ca. Intrinsic water-use efficiency can be defined as A/gs, where A is the net CO2 assimilation rate of a leaf and gs is the stomatal conductance to water vapour:

| (3) |

where the factor 1.6 in the denominator represents the ratio of stomatal conductance for water vapour to that for CO2. Equation (3) shows that A/gs can be expected to increase if ci/ca decreases, assuming no change in ca.

In a more complete form of the model, ∆ 13C can be expressed as (Farquhar et al., 1982b; Farquhar and Cernusak, 2012; Busch et al., 2020):

| (4) |

where ab is the 13C/12C fractionation during diffusion of CO2 through the boundary layer (2.9 ‰), and am is that for dissolution and diffusion from the intercellular air spaces to the sites of carboxylation in the chloroplasts (1.8 ‰). The term b is here taken as fractionation by Rubisco (∼29 ‰), e is fractionation during day respiration and f is fractionation during photorespiration. Rd is the rate of day respiration and Γ* is the CO2 compensation point in the absence of day respiration. The terms cs and cc are the CO2 concentrations at the leaf surface and at the sites of carboxylation, respectively. The term t is a ternary correction factor, defined as t ≈ E/(2gc), where E is transpiration rate and gc is leaf conductance to CO2 (Farquhar and Cernusak, 2012). Equation (4) is thought to include most processes that would impact upon ∆ 13C if it were measured instantaneously, for example using the online technique in which the δ 13C of CO2 is measured in air entering and exiting a gas exchange cuvette (Evans et al., 1986).

Comparison of eqns (1) and (4) shows that there are a number of processes in the more complete model for ∆ 13C that have been neglected from the simplified expression. These include the drawdown in CO2 concentration from ci to cc, fractionations associated with day respiration and photorespiration, and the ternary correction, for example. The simplified expression in eqn (2) is most often applied to δ 13Cp measured in plant dry matter, most commonly in leaves or wood. On the other hand, the more complete eqn (4) is most often applied to instantaneous measurements of ∆ 13C, when parameters determined by accompanying gas exchange measurements can be applied in combination, with the objective of solving for the conductance from ci to cc, termed mesophyll conductance. When eqn (2) is applied to plant dry matter, there can be additional considerations that may become important. Two such examples are post-photosynthetic fractionations, in which the carbon retained in the dry matter of a given tissue takes on a δ 13C different from that of the photosynthate used to construct the tissue (Badeck et al., 2005), and developmental effects, whereby ontogenetic changes in ∆ 13C through time will be reflected in the integrated δ 13C signal of the accumulated carbon in the tissue (Cernusak et al., 2009a).

The practical benefit of eqn (2) is that if the terms δ 13Ca, as and are known, then δ 13Cp can be used to estimate ci/ca and therefore A/gs from only a measurement of the carbon isotope ratio of a dried leaf, for example. For plants grown outdoors, CO2 in the atmosphere is generally well mixed and δ 13Ca can be approximated as −8 ‰, although it can be more negative beneath dense forest canopies (Buchmann et al., 2002). Also, there is a decreasing trend in δ 13Ca due to fossil fuel combustion, such that the average tropospheric value for 2018 was −8.5 ‰ (Keeling et al., 2017). The term as is assumed to have a value of 4.4 ‰, based on diffusivities of 13CO2 and 12CO2 in static air (Farquhar et al., 1989b). When eqn (2) was first developed and applied to δ 13Cp of mature leaves, was estimated to have a value of 27 ‰ (Farquhar et al., 1982a). This is smaller than in vitro estimates of discrimination by Rubisco of about 29–30 ‰ (McNevin et al., 2007). This is expected because has lumped within it the additional processes shown in eqn (4). Furthermore, there also exists the possibility in C3 plants that some carboxylation can take place by phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase, which would lower the combined fractionation factor for Rubisco plus that enzyme (Farquhar and Richards, 1984; Raven and Farquhar, 1990). Interestingly, if one calculates using typical parameter values for these additional processes, one would expect a value even smaller than 27 ‰, for example in the range from 21 to 24 ‰ (Ubierna and Farquhar, 2014). Thus, it appears that the empirically determined value of 27 ‰ for for mature leaf tissue probably includes additional effects to those shown in eqn (4), such as post-photosynthetic fractionation or integration through time of a developmental change in photosynthetic discrimination.

The original estimate for of 27 ‰ has been shown over the years to be reasonably general for mature leaf tissue, and δ 13Cp has accordingly been shown for the most part to be a reliable indicator of variation in ci/ca, and therefore of intrinsic water-use efficiency (Farquhar et al., 1982b, 1989a; Cernusak et al., 2013; Cernusak, 2020). An interesting exception to this general rule is that young, expanding leaves typically have less negative δ 13Cp than mature leaves of the same individual, while at the same time also having higher ci/ca (Evans, 1983; Francey et al., 1985; Terwilliger et al., 2001; Cernusak et al., 2009a). This is opposite to the expectation based on eqn (2), which would predict that a leaf with higher ci/ca should have a lower, or more negative, δ 13Cp. If widespread, this would establish an intriguing exception to the general relationship between δ 13Cp and intrinsic water-use efficiency, and it may also give insight into why estimated for mature leaves takes on a value somewhat higher than expected.

We had two objectives in this paper. The first was to compile data from both published and unpublished sources to determine (1) how widespread the δ 13Cp difference between mature and young leaves is, and (2) whether this difference shows dependence on temperate vs. tropical climate, or on whether the plant is deciduous or evergreen. Our second objective was to place the change in δ 13Cp from young to mature leaves into the context of the value of , which has been estimated for mature leaves. We hypothesized that a general decrease in δ 13Cp during leaf expansion could partly explain why appears to be somewhat larger than expected based on comparison of eqns (1) and (4). To gain insight into the physiological processes at work, we measured instantaneous ∆ 13C in both young and mature leaves, along with ci/ca. We then built upon previous work to develop a theoretical basis for why δ 13Cp decreases during leaf expansion in C3 plants.

METHODS

We compiled published and unpublished data to test whether the extent of the decline in leaf δ 13Cp during leaf expansion differs by biome or by deciduousness. We categorized study locations as either temperate or tropical, depending on geographical location. In addition, we categorized species as either evergreen or deciduous based on notes in the published papers, or botanical descriptions of the species. Previously unpublished data were included for Ficus insipida and Swietenia macrophylla grown as seedlings at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, Santa Cruz Experimental Field Facility, Gamboa, Panama [9°07′N, 79°42′W; 28 m above sea level a.s.l.)], and for Toona ciliata grown in a glasshouse at the Australian National University in Canberra, Australia (35°17′S, 149°7′E; 577 m a.s.l.). The seedlings of T. ciliata were obtained from north-east Queensland, and were therefore categorized as tropical. Although this species is deciduous, we considered it evergreen for our analysis because the seedlings had not experienced a leaf shedding event before sampling, and the canopy had not therefore been reconstructed from stored carbohydrate, which we assumed was an important process for δ 13Cp of leaves of deciduous species.

We similarly surveyed published literature for measurements of ci/ca in young and mature leaves. We also included in this compilation values of ci/ca for young and mature leaves of F. insipida, S. macrophylla and T. ciliata from the locations described above. We made gas exchange measurements of F. insipida and S. macrophylla with a Li-6400 portable photosynthesis system (Li-Cor Inc., Lincoln, NE, USA). The chamber was illuminated with 1200 μmol photosynthetically active radiation m−2 s−1, provided by an artificial light source (6400-02B LED, Li-Cor Inc.). Leaf temperature averaged 30.8 ± 0.5 °C (mean ± s.d.) during measurements, leaf-to-air vapour pressure difference averaged 0.9 ± 0.3 kPa, and the CO2 concentration in the chamber averaged 378 ± 22 μmol mol−1. We measured leaves of different ages within a plant on the same day, and we also made repeated measurements of the same leaves as they expanded from one day to the next. These gas exchange measurements were made between 13 and 19 October 2009.

We measured online carbon isotope discrimination (∆ 13C) on young and mature leaves of T. ciliata at the Australian National University between 12 and 20 April 2012. These measurements were made by coupling a Li-6400 portable photosynthesis system with a tunable diode laser spectrometer (TGA100A, Campbell Scientific Inc., Logan, UT, USA). The calibration and measurement protocol was similar to that described previously (Tazoe et al., 2011; Evans and von Caemmerer, 2013). ∆ 13C was calculated from the carbon isotope ratio of CO2 entering and exiting the leaf chamber, along with CO2 concentrations of dry air, according to the equation presented by Evans et al. (1986). The irradiance during measurements was 1500 μmol photosynthetically active radiation m−2 s−1 supplied with an artificial light source (6400-02B LED, Li-Cor Inc.); average leaf temperature was 26.9 ± 0.2 °C; average leaf-to-air vapour pressure difference was 1.1 ± 0.2 kPa; and average CO2 concentration in the sample chamber was 380 ± 3 µmol mol−1.

Leaves measured for gas exchange in both Panama and at the Australian National University were collected, and their leaf area was determined using a leaf area meter (Li-3100, Li-Cor Inc.). They were then oven dried at 70 °C, weighed, and thereafter ground to a fine powder and measured for the δ 13C of their dry mass as described previously (Cernusak et al., 2003, 2009b).

We used a paired t-test to compare δ 13C values between mature and young leaves. We then calculated the difference between mature and young leaf δ 13C for each species, and used two-way ANOVA to test for effects on this difference of climate and deciduousness. A similar analysis was conducted for ci/ca. Statistical analyses were conducted in R (R Core Team, 2019).

RESULTS

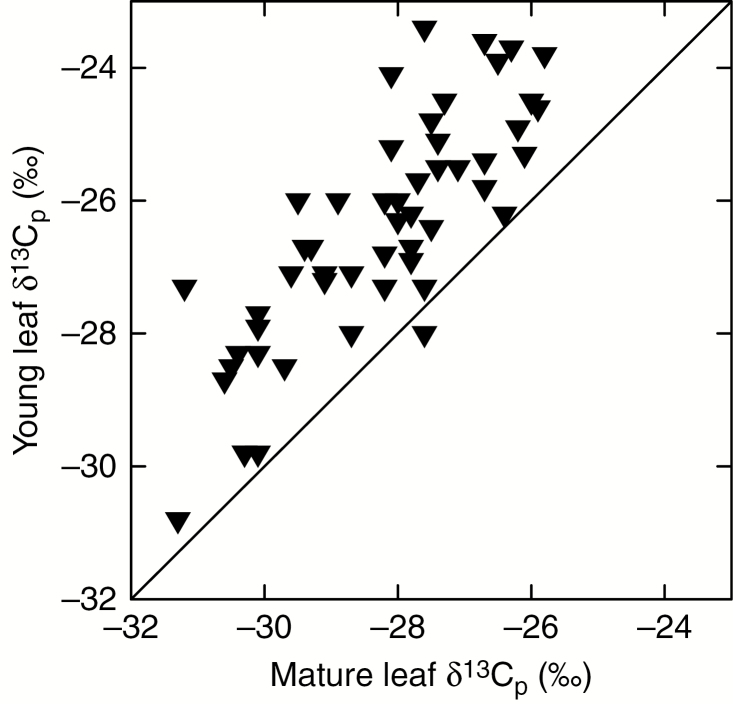

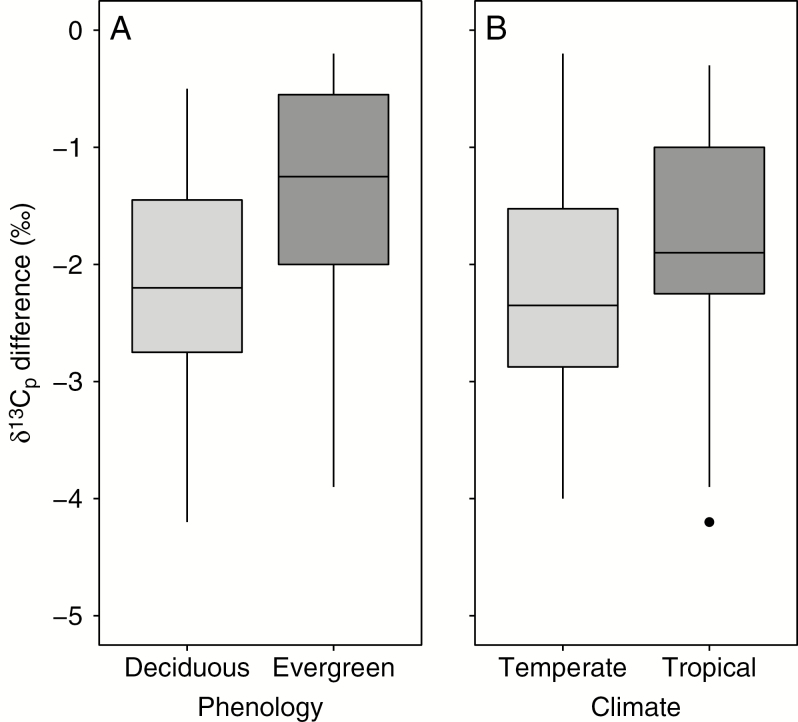

In our literature survey, we found paired δ 13C values for young and mature leaves of 54 species. Of these, 36 were from tropical environments and 18 from temperate environments, and we designated 18 of the species as evergreen and 36 as deciduous (Table 1). The δ 13C values for mature leaves ranged from −31.3 to −25.8 ‰, and those for young leaves ranged from −30.8 to −23.0 ‰ (Fig. 1). A paired t-test indicated that young leaf δ 13C was significantly less negative than mature leaf δ 13C (t = 13.2, P < 0.0001, n = 54). Values for the difference between mature and young leaf δ 13C ranged from −4.2 to 0.4 ‰, with a mean of −1.9 ‰. Two-way ANOVA indicated that the δ 13C difference between mature and young leaves did not vary significantly between tropical and temperate climates (t = 1.6, P = 0.11, n = 54). However, whether a species was deciduous or evergreen had a significant effect on the mature-to-young leaf δ 13C difference (t = 2.1, P < 0.05, n = 54). The mean δ 13C difference for deciduous species was −2.1 ‰ and that for evergreen species was −1.4 ‰, with median and quartiles shown in Fig. 2. The interaction effect between climate and deciduousness was not significant (t = −1.4, P = 0.18, n = 54).

Table 1.

Stable carbon isotope ratios of young and mature leaves (δ 13Cp; ‰) for plants that use the C3 photosynthetic pathway.

| Species | Young leaf δ 13C | Mature leaf δ 13C | Difference, mature–young | Deciduousness | Geography | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acer grandidentatum | −26.8 | −28.2 | −1.4 | Deciduous | Temperate | Leavitt and Long (1985) |

| Acer negundo | −27.9 | −30.1 | −2.2 | Deciduous | Temperate | Tipple and Ehleringer (2018) |

| Acer rubrum | −25.2 | −28.1 | −2.9 | Deciduous | Temperate | Lowdon and Dyck (1974) |

| Acer rubrum | −27.1 | −29.6 | −2.5 | Deciduous | Temperate | Suh and Diefendorf (2018) |

| Acer saccharum | −28.7 | −30.6 | −1.9 | Deciduous | Temperate | Suh and Diefendorf (2018) |

| Acrocomia aculeata | −26.9 | −27.8 | −0.9 | Evergreen | Tropical | Holtum and Winter (2005) |

| Albizia adinocephala | −27.1 | −29.1 | −2 | Evergreen | Tropical | Holtum and Winter (2005) |

| Anacardium excelsum | −24.6 | −25.9 | −1.3 | Deciduous | Tropical | Holtum and Winter (2005) |

| Anacardium excelsum | −25.4 | −26.7 | −1.3 | Deciduous | Tropical | Terwilliger (1997) |

| Annona spraguei | −26.7 | −27.8 | −1.1 | Deciduous | Tropical | Holtum and Winter (2005) |

| Antirrhoea trichantha | −26.0 | −28.9 | −2.9 | Deciduous | Tropical | Holtum and Winter (2005) |

| Astronium graveolens | −28.0 | −27.6 | 0.4 | Deciduous | Tropical | Holtum and Winter (2005) |

| Betula occidentalis | −28.5 | −29.7 | −1.2 | Deciduous | Temperate | Tipple and Ehleringer (2018) |

| Beureria cumanensis | −26.2 | −27.8 | −1.6 | Deciduous | Tropical | Sobrado and Ehleringer (1997) |

| Capparis aristiguetae | −27.3 | −31.2 | −3.9 | Evergreen | Tropical | Sobrado and Ehleringer (1997) |

| Castilla elastica | −26.0 | −28.0 | −2 | Deciduous | Tropical | Holtum and Winter (2005) |

| Cecropia insignis | −27.2 | −29.1 | −1.9 | Evergreen | Tropical | Terwilliger (1997) |

| Cecropia longipes | −23.7 | −26.3 | −2.6 | Deciduous | Tropical | Terwilliger (1997) |

| Cecropia longipes | −24.9 | −26.2 | −1.3 | Deciduous | Tropical | Terwilliger et al. (2001) |

| Cecropia longipes | −25.3 | −26.1 | −0.8 | Deciduous | Tropical | Holtum and Winter (2005) |

| Cecropia peltata | −24.8 | −27.5 | −2.7 | Evergreen | Tropical | Terwilliger (1997) |

| Combretum apiculatum | −25.7 | −27.7 | −2 | Deciduous | Tropical | February and Higgins (2016) |

| Cordia alliadora | −26.7 | −29.4 | −2.7 | Deciduous | Tropical | Terwilliger (1997) |

| Coursetia arborea | −26.0 | −28.2 | −2.2 | Deciduous | Tropical | Sobrado and Ehleringer (1997) |

| Didymopanax morototoni | −26.3 | −28.0 | −1.7 | Evergreen | Tropical | Holtum and Winter (2005) |

| Enterolobium cyclocarpum | −27.1 | −28.7 | −1.6 | Deciduous | Tropical | Holtum and Winter (2005) |

| Fagus crenata | −25.9 | −29.8 | −3.9 | Deciduous | Temperate | Han et al. (2016) |

| Fagus sylvatica | −24.1 | −28.1 | −4 | Deciduous | Temperate | Damesin and Lelarge (2003) |

| Fagus sylvatica | −24.5 | −27.3 | −2.8 | Deciduous | Temperate | Keitel et al. (2003) |

| Fagus sylvatica | −24.5 | −26.0 | −1.5 | Deciduous | Temperate | Helle and Schleser (2004) |

| Ficus insipida | −23.8 | −25.8 | −2 | Evergreen | Tropical | Holtum and Winter (2005) |

| Ficus insipida | −28.5 | −30.5 | −2 | Evergreen | Tropical | This paper |

| Larix sibirica | −23.0 | −25.8 | −2.8 | Deciduous | Temperate | Li et al. (2007) |

| Lonchocarpus dipteroneurus | −25.5 | −27.4 | −1.9 | Deciduous | Tropical | Sobrado and Ehleringer (1997) |

| Luehea seemannii | −27.3 | −27.6 | −0.3 | Evergreen | Tropical | Holtum and Winter (2005) |

| Luehea seemanii | −27.3 | −28.2 | −0.9 | Evergreen | Tropical | Terwilliger (1997) |

| Morisonia americana | −29.8 | −30.1 | −0.3 | Evergreen | Tropical | Sobrado and Ehleringer (1997) |

| Picea crassifolia | −25.5 | −27.1 | −1.6 | Evergreen | Temperate | Li et al. (2019) |

| Pithecellobium dulce | −26.7 | −29.3 | −2.6 | Deciduous | Tropical | Sobrado and Ehleringer (1997) |

| Populus angustifolia | −30.8 | −31.3 | −0.5 | Deciduous | Temperate | Tipple and Ehleringer (2018) |

| Pseudobombax septenatum | −26.4 | −27.5 | −1.1 | Deciduous | Tropical | Holtum and Winter (2005) |

| Quercus ilex | −26.2 | −26.4 | −0.2 | Evergreen | Temperate | Damesin et al. (1998) |

| Quercus pubescens | −23.9 | −26.5 | −2.6 | Deciduous | Temperate | Damesin et al. (1998) |

| Salix interior | −23.6 | −26.7 | −3.1 | Deciduous | Temperate | Le Roux-Swarthout et al. (2001) |

| Sassafras albidum | −26.0 | −29.5 | −3.5 | Deciduous | Temperate | Suh and Diefendorf (2018) |

| Siparuna guianensis | −29.8 | −30.3 | −0.5 | Evergreen | Tropical | Vitoria et al. (2016) |

| Spondias mombin | −25.1 | −27.4 | −2.3 | Deciduous | Tropical | Holtum and Winter (2005) |

| Swietenia macrophylla | −28.3 | −30.4 | −2.1 | Evergreen | Tropical | This paper |

| Terminalia sericea | −23.4 | −27.6 | −4.2 | Deciduous | Tropical | February and Higgins (2016) |

| Toona ciliata | −25.8 | −26.7 | −0.9 | Evergreen | Tropical | This paper |

| Ulmus americana | −28.3 | −30.1 | −1.8 | Deciduous | Temperate | Suh and Diefendorf (2018) |

| Urera caracasana | −28.0 | −28.7 | −0.7 | Evergreen | Tropical | Terwilliger et al. (2001) |

| Xylopia sericea | −29.8 | −30.3 | −0.5 | Evergreen | Tropical | Vitoria et al. (2016) |

| Zuelania guidonia | −27.7 | −30.1 | −2.4 | Deciduous | Tropical | Holtum and Winter (2005) |

Fig. 1.

Stable carbon isotope ratios of young vs. mature leaf dry matter (δ 13Cp) for the species shown in Table 1. The solid line shows the one-to-one line.

Fig. 2.

Boxplots showing the δ 13Cp difference between mature and young leaf dry matter as a function of phenology (A), and whether the trees grew in temperate or tropical climate zones (B). The δ 13C difference was calculated as mature leaf δ 13Cp minus young leaf δ 13Cp for the same species. Further details of the dataset are given in Table 1.

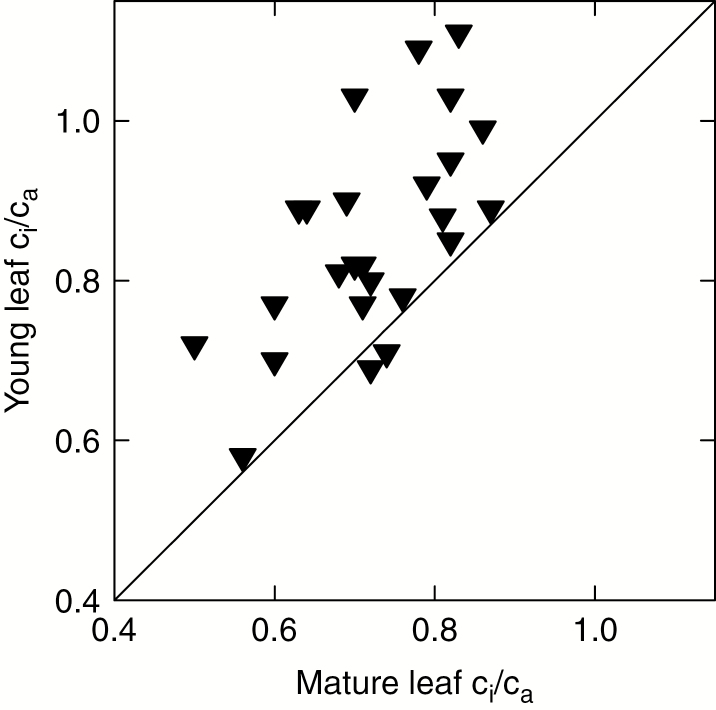

For instantaneous measurements of ci/ca, we compiled data for 25 woody C3 species for which we could locate paired values for young and mature leaves. We again designated these species as either deriving from temperate or tropical environments, and as either deciduous or evergreen (Table 2). The instantaneous ci/ca for young leaves was significantly higher than that for mature leaves (t = 6.4, P < 0.0001, n = 25), with mean values of 0.86 and 0.72, respectively (Fig. 3). For the difference in instantaneous ci/ca between mature and young leaves, we did not detect significant variation between temperate and tropical species (t = 1.0, P = 0.31, n = 25), nor between deciduous and evergreen species (t = 1.5, P = 0.15, n = 25).

Table 2.

The ratio of intercellular to ambient CO2 concentrations (ci/ca) for young and mature leaves of plants that use the C3 photosynthetic pathway.

| Species | Young leaf ci/ca | Mature leaf ci/ca | Difference, mature–young | Deciduousness | Geography | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anthocephalus chinensis | 0.89 | 0.63 | −0.26 | Evergreen | Tropical | Cai et al. (2005) |

| Beureria cumanensis | 0.71 | 0.74 | 0.03 | Deciduous | Tropical | Sobrado and Ehleringer (1997) |

| Byrsonima sericea | 0.90 | 0.69 | −0.21 | Deciduous | Tropical | Vitoria et al. (2016) |

| Cecropia longipes | 1.09 | 0.78 | −0.31 | Deciduous | Tropical | Terwilliger et al. (2001) |

| Coursetia arborea | 0.77 | 0.71 | −0.06 | Deciduous | Tropical | Sobrado and Ehleringer (1997) |

| Eucalyptus delegatensis | 0.85 | 0.82 | −0.03 | Evergreen | Temperate | Cernusak (2020) |

| Eucalyptus miniata | 1.11 | 0.83 | −0.28 | Evergreen | Tropical | Cernusak et al. (2006) |

| Eucalyptus pauciflora | 0.88 | 0.81 | −0.07 | Evergreen | Temperate | Cernusak (2020) |

| Eucalyptus tetrodonta | 1.03 | 0.82 | −0.21 | Evergreen | Tropical | Cernusak et al. (2006) |

| Ficus insipida | 0.89 | 0.87 | −0.02 | Evergreen | Tropical | This paper |

| Lagarostrobos franklinii | 0.70 | 0.60 | −0.1 | Evergreen | Temperate | Francey et al. (1985) |

| Litsea dilleniifolia | 0.80 | 0.72 | −0.08 | Evergreen | Tropical | Cai et al. (2005) |

| Litsea pierrei var. semois | 0.82 | 0.70 | −0.12 | Evergreen | Tropical | Cai et al. (2005) |

| Lonchocarpus dipteroneurus | 0.82 | 0.71 | −0.11 | Deciduous | Tropical | Sobrado and Ehleringer (1997) |

| Luehia seemanii | 0.99 | 0.86 | −0.13 | Deciduous | Tropical | Terwilliger (1997) |

| Morisonia americana | 0.78 | 0.76 | −0.02 | Evergreen | Tropical | Sobrado and Ehleringer (1997) |

| Pachysandra terminalis | 0.58 | 0.56 | −0.02 | Evergreen | Temperate | Yoshie and Kawano (1986) |

| Persea americana | 0.77 | 0.60 | −0.17 | Evergreen | Tropical | Terwilliger (1997) |

| Pithecellobium dulce | 0.69 | 0.72 | 0.03 | Deciduous | Tropical | Sobrado and Ehleringer (1997) |

| Quercus douglasii | 0.72 | 0.50 | −0.22 | Deciduous | Temperate | Xu and Baldocchi (2003) |

| Siparuna guianensis | 1.03 | 0.70 | −0.33 | Evergreen | Tropical | Vitoria et al. (2016) |

| Swietenia macrophylla | 0.95 | 0.82 | −0.13 | Evergreen | Tropical | This paper |

| Toona ciliata | 0.81 | 0.68 | −0.13 | Evergreen | Tropical | This paper |

| Urera caracasana | 0.92 | 0.79 | −0.13 | Evergreen | Tropical | Terwilliger et al. (2001) |

| Xylopia sericea | 0.89 | 0.64 | −0.25 | Evergreen | Tropical | Vitoria et al. (2016) |

Fig. 3.

Instantaneous measurements of the ratio of intercellular to ambient CO2 concentrations (ci/ca) for young leaves plotted against those for mature leaves of the same species. Data are detailed in Table 2. The solid line shows the one-to-one line.

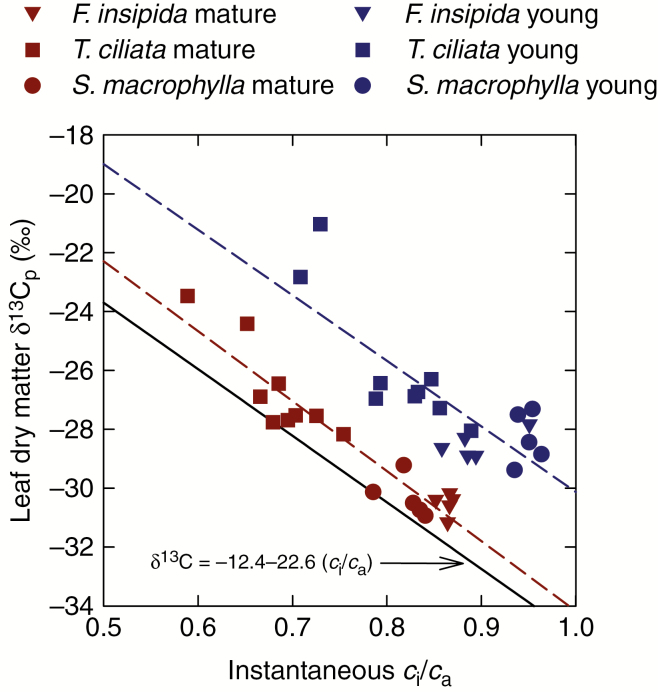

The measurements that we made in S. macrophylla, F. insipida and T. ciliata were consistent with these overall trends. The instantaneous values of ci/ca were higher in young than in mature leaves, and δ 13C was less negative in young than in mature leaves. Figure 4 shows δ 13C of bulk leaf material plotted against instantaneous ci/ca for these three species for young and mature leaves. For a given instantaneous ci/ca, there is a clear separation between δ 13C of young and mature leaves, with that of young leaves being about 2 ‰ less negative than that of mature leaves. The relationship between mature leaf δ 13C and instantaneous ci/ca is similar to that originally reported by Farquhar et al. (1982a), having the form δ 13Cp = δ 13Ca − as − ( − as)ci/ca, with as = 4.4 ‰ and = 27 ‰. Thus, the coefficients that we observed for the linear relationship between mature leaf δ 13C and ci/ca match reasonably well those originally observed for mature leaves of Phaseolus vulgaris, Avicennia marina and Aegiceras corniculatum (Farquhar et al., 1982a). However, the relationship that we observed for young leaves shows a consistent offset from this well-established relationship (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

The stable carbon isotope ratio of the dry matter (δ 13Cp) of young and mature leaves plotted against instantaneous measurements of the ratio of intercellular to ambient CO2 concentrations (ci/ca) in the same leaves. The solid line represents the theoretical relationship according to the model of Farquhar et al. (1982a). The broken lines represent least-squares regressions through the mature and young leaves. The regression equation for mature leaves is δ 13Cp = −10.4 – 23.8(ci/ca) (R2 = 0.90), and that for young leaves is δ 13Cp = −7.8 – 22.3(ci/ca) (R2 = 0.64).

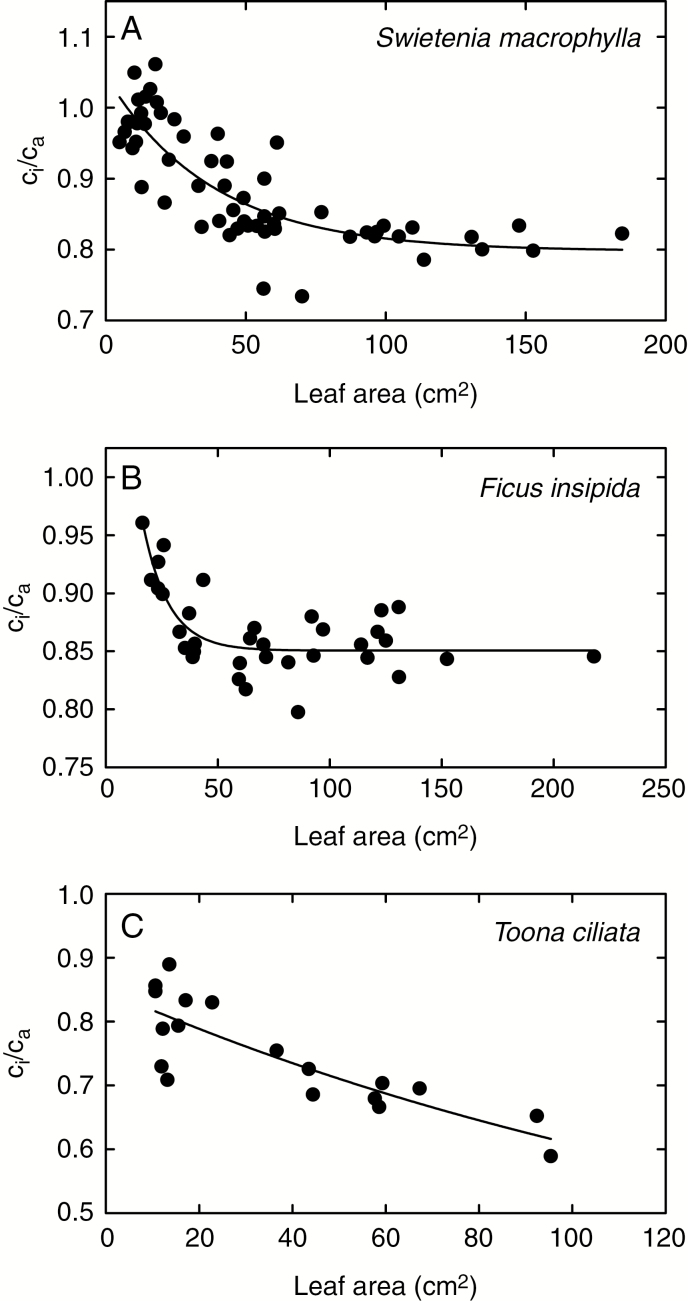

Figure 5 shows instantaneous observations of ci/ca for S. macrophylla, F. insipida and T. ciliata plotted against leaf size, where leaf size in this case acts as a proxy for leaf age. For S. macrophylla and F. insipida, we quantified the relationship between leaf size and leaf age during leaf expansion. Leaves of both species required about 15 d to reach full expansion, and showed a sigmoidal relationship between days after emergence and area as a proportion of the fully expanded area. For all three species in Fig. 5, there is a non-linear relationship between ci/ca and leaf size, which can be approximated by an exponential decay function. The smallest leaves that we could measure showed the highest values of ci/ca, and as the leaves expanded, ci/ca declined until it stabilized at values typical of mature leaves on the same plant.

Fig. 5.

Instantaneous measurements of the ratio of intercellular to ambient CO2 concentrations (ci/ca) plotted against leaf area for three tropical tree species. Here, leaf area is a proxy for leaf age.

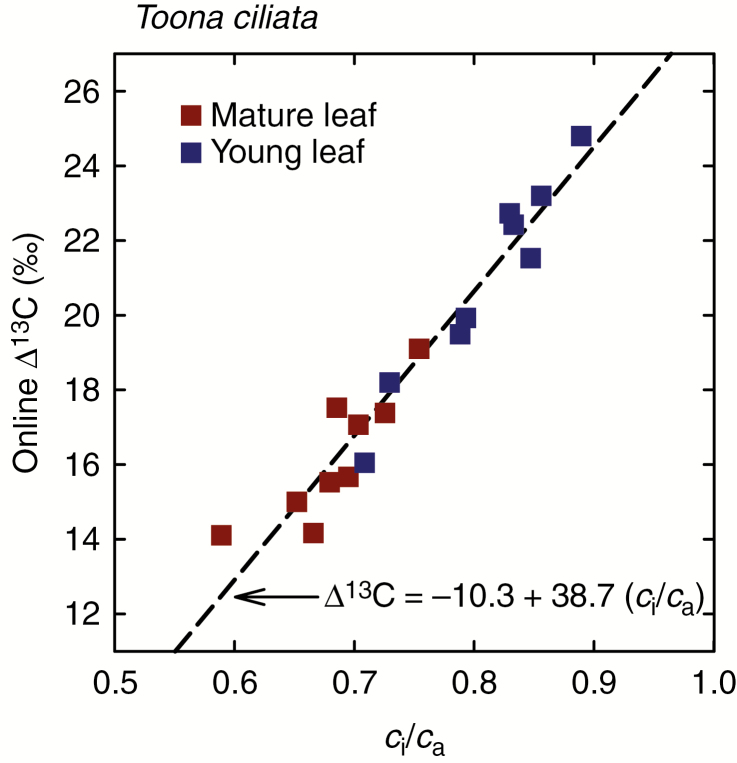

On-line measurements of ∆ 13C are plotted against simultaneously measured ci/ca in young and mature leaves of T. ciliata in Fig. 6. For these instantaneous measurements, the relationship between ∆ 13C and ci/ca was similar between young and mature leaves, although the range of ci/ca covered by young leaves only partly overlapped with the range covered by mature leaves. Analysis of covariance indicated that the interaction term between leaf age (young or mature) and ci/ca did not significantly improve the prediction of ∆ 13C, and with this interaction term removed, the main effect of leaf age also did not improve the prediction of ∆ 13C compared to a model with only an intercept and ci/ca. Thus, a simple linear model could be fitted to all the data in Fig. 6 (R2 = 0.94, P < 0.0001, n = 18). This model had a slope of 38.7 ‰. This indicates that a developmentally driven decrease in ci/ca of 0.1 in a young leaf of T. ciliata will be accompanied by a decrease in instantaneous ∆ 13C of 3.9 ‰.

Fig. 6.

Online measurements of carbon isotope discrimination (∆ 13C) plotted against the ratio of intercellular to ambient CO2 concentrations (ci/ca) measured at the same time; measurements were made in both young and mature leaves of Toona ciliata. The broken line shows a least squares regression through the data described by the equation shown at the bottom of the panel.

DISCUSSION

Our survey of literature data (Table 1) confirms that there is a general pattern for C3 plants in which leaf δ 13Cp decreases as leaves expand. This pattern has been previously observed by a number of authors for selected species (see references in Table 1). Following seminal work relating carbon isotope discrimination to ci/ca (Farquhar et al., 1982a, b), it was also recognized that this developmental change in leaf dry matter δ 13C is opposite to that which would be expected based on the relationship between instantaneous ∆ 13C and ci/ca (Evans, 1983; Francey et al., 1985; Evans et al., 1986; Terwilliger, 1997, 2001; Cernusak et al., 2009a). Our literature survey further establishes the generality of this observation (Table 2).

Evans (1983) and Francey et al. (1985) put forth an explanation for the divergence of leaf δ 13Cp and ci/ca during leaf expansion based on the following sequence of logic: (1) the structural carbon in a leaf comprises a mixture, some of which is imported from source leaves in the phloem or from storage in buds or woody tissues, and some of which is fixed by the leaf’s own photosynthesis; (2) in an emerging leaf, the mixture will primarily comprise carbon imported from source leaves or from storage; (3) source leaves are likely to be mature leaves, operating at their typical ci/ca; (4) the young, expanding leaf will have higher ci/ca than these mature leaves; (5) higher ci/ca in the young, expanding leaf will cause the carbon fixed by its own photosynthesis to have more negative δ 13C than that imported from mature leaves or from storage; (6) this will cause the expanding leaf’s δ 13Cp to become progressively more negative as it adds more of its own photosynthate to the structural carbon being laid down during leaf expansion; and (7) finally, when the leaf reaches maturity, it will go on to export carbon which it fixes at lower ci/ca and therefore with less negative δ 13C than the mixture which comprises its own structural carbon.

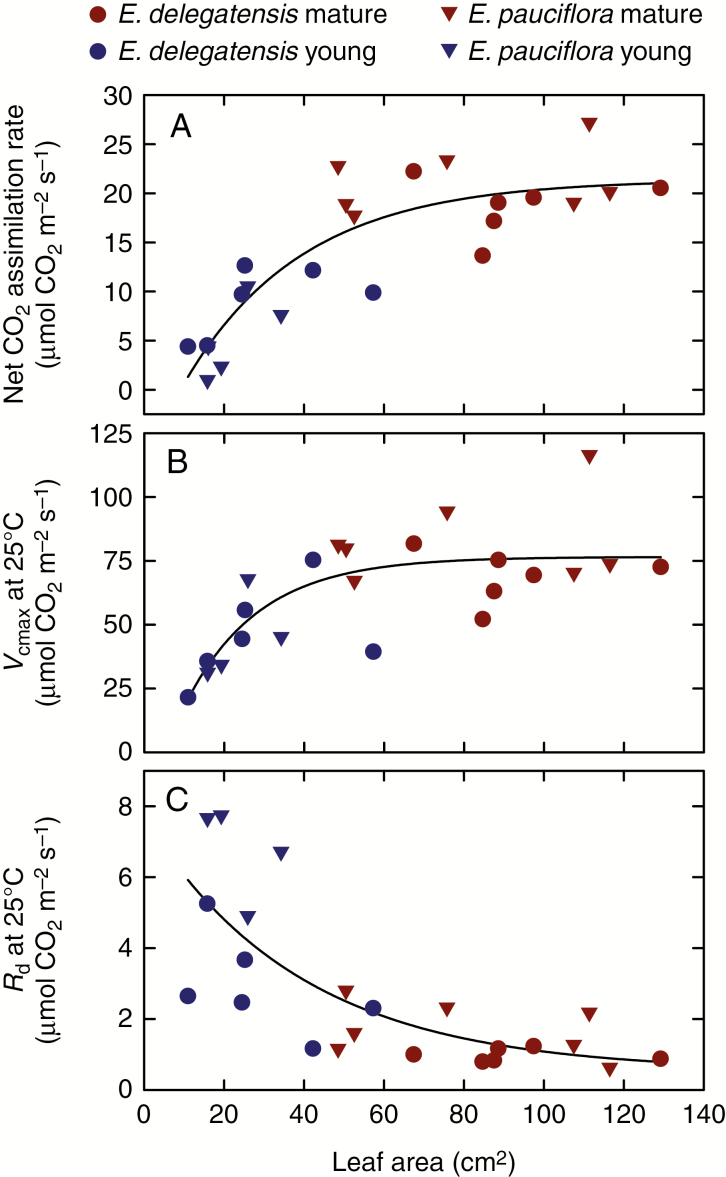

The results that we present here help to strengthen and reinforce this mechanistic explanation for the developmental change in leaf δ 13Cp that occurs during leaf expansion in C3 plants. We demonstrated that for those instances in which ci/ca was measured in both young and mature leaves of the same species, the young leaves had significantly higher ci/ca than the mature leaves. In some instances, the young leaves had ci/ca greater than unity, indicating a net CO2 efflux from the leaves (Table 2; Fig. 3). Why should young, expanding leaves have higher ci/ca than mature leaves? Figure 7A shows net CO2 assimilation rates for young and mature leaves of two Eucalyptus species, for which CO2 responses curves (A–ci) were also measured (Cernusak, 2020). Analysis of the A–ci curves provides insight into why ci/ca is higher in young than in mature leaves. Young leaves have both lower photosynthetic capacity, represented by the maximum Rubisco carboxylation rate, Vcmax (Fig. 7B), and a higher day respiration rate, Rd (Fig. 7C). The combination of these two factors leads to less CO2 being removed from the intercellular air spaces by carboxylation in the chloroplasts of the young leaves, due both to the lower carboxylation velocity and because more CO2 is being fed into the chloroplasts by mitochondrial CO2 release, which means less will come from the intercellular air spaces (Ubierna et al., 2019). The patterns for net CO2 assimilation, Vcmax and Rd can be approximated as exponential functions of leaf area, where leaf area is again taken as a proxy for leaf age, similar to the pattern of ci/ca change with leaf area (Fig. 5).

Fig. 7.

Changes in net photosynthesis rate (A), maximum rate of carboxylation by Rubisco (B) and day respiration rate (C) as a function of leaf area for two Eucalyptus species. Here, leaf area represents a proxy for leaf age. These data were presented previously by Cernusak (2020), and details of the measurements are given there.

We showed, for the first time to our knowledge, that the instantaneous ∆ 13C observed in young, expanding leaves is larger than that in mature leaves of the same plant, consistent with expectation based on their higher ci/ca (Fig. 6). The slope of the relationship between ∆ 13C and ci/ca for this dataset, which includes both young and mature leaves, was rather steep, although within expectations if one were to apply the more complete eqn (4) and assume mesophyll resistance remained in a fixed proportion to stomatal resistance. It indicated a change in ∆ 13C of almost 4 ‰ for each 0.1 change in ci/ca. The mean difference in ci/ca between young and mature leaves from our literature survey was 0.13. Applying the ∆ 13C–ci/ca relationship that we observed for T. ciliata to this difference would predict a mean difference of about 5 ‰ in instantaneous ∆ 13C between young and mature leaves; that is, young leaves would fix carbon depleted in 13C by 5 ‰ compared to mature leaves. This would seem to make quite plausible the suggestion that young leaves can add enough of their own photosynthate to their structural carbon during leaf expansion to shift their overall δ 13Cp by about 2 ‰.

Figure 6 suggests that the relationships between ∆ 13C and ci/ca for both young and mature leaves are similar, whereas Fig. 4 shows that the relationships between leaf δ 13Cp and ci/ca differ for young and mature leaves. The sequence of logic detailed above implies that the relationship between mature leaf δ 13Cp and ci/ca should reflect the legacy of the contribution to δ 13Cp of photosynthesis while the leaves were expanding, with this process having added carbon with more negative δ 13C. If this is the case, we could expect the general relationship between mature leaf δ 13Cp and ci/ca established by Farquhar et al. (1982a), and subsequently confirmed in numerous other species (Farquhar et al., 1989a; Cernusak et al., 2013; Cernusak, 2020), to differ from instantaneous relationships between ∆ 13C and ci/ca. The relationship observed for mature leaf dry matter δ 13Cp is the one represented by eqn (2) with as = 4.4 ‰ and = 27 ‰.

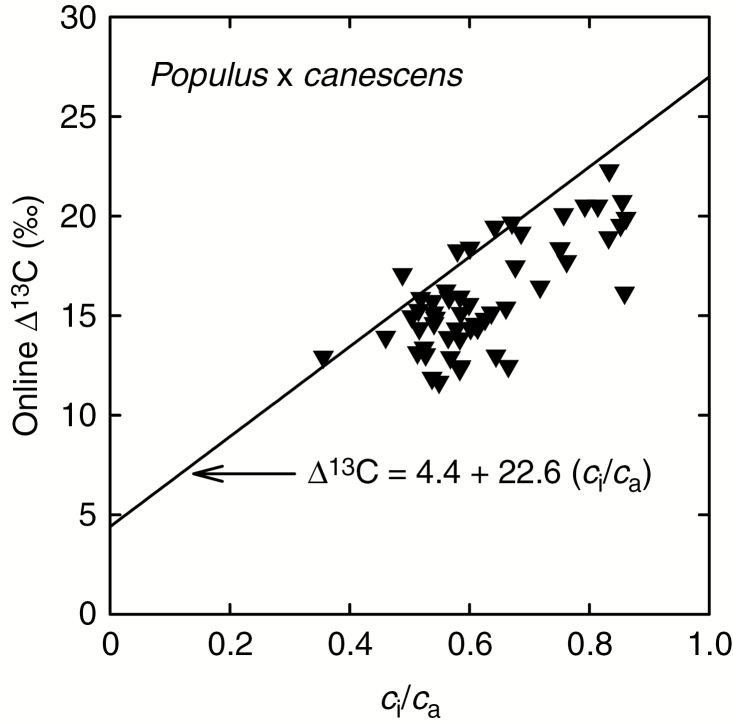

Our expectation is that this relationship, based on mature leaf δ 13Cp, should appear to show a larger ∆ 13C for a given ci/ca due to the ~2 ‰ depletion of δ 13Cp that occurs during leaf expansion than would be shown for instantaneous ∆ 13C in mature leaves. Figure 8 shows example data for instantaneous ∆ 13C and ci/ca for a dataset recently collected for mature leaves of grey poplar, Populus × canescens (Cernusak et al., 2019) and the relationship developed for mature leaf δ 13Cp (Farquhar et al., 1982a). The relationship for mature leaf δ 13Cp is indeed offset compared to the instantaneous measurements, with ∆ 13C from mature leaf δ 13Cp appearing to be larger for a given ci/ca than that for the instantaneous measurements. This pattern of the relationship for mature leaf δ 13Cp lying above observations of instantaneous ∆ 13C for a given ci/ca is common to other datasets as well (Evans et al., 1986; von Caemmerer and Evans, 1991). It is also consistent with ∆ 13C inferred from measurements of mature leaf dry matter being larger than instantaneous observations of ∆ 13C at ci/ca representative of growth conditions (Evans et al., 1986; von Caemmerer and Evans, 1991). This latter difference for the mature leaves of T. ciliata in the present study averaged 3 ‰.

Fig. 8.

Instantaneous measurements of carbon isotope discrimination (∆ 13C) plotted against the ratio of intercellular to ambient CO2 concentrations (ci/ca) measured concurrently. Data are for mature leaves of wild type plants of Populus × canescens from the dataset published by Cernusak et al. (2019). The solid line in the graph represents a general, empirical relationship between ∆ 13C measured in mature leaf dry matter and ci/ca (Farquhar et al., 1982a).

Is there other experimental evidence to support the sequence of logic given above to explain changes in leaf δ 13Cp with leaf expansion? One kind of experiment is to examine leaves in which photosynthesis did not occur during leaf expansion to see if they show different mature leaf δ 13Cp than those in which photosynthesis did occur. Evans (1983) allowed leaves of Triticum aestivum and Phaseolus vulgaris to expand in darkness and therefore in the absence of photosynthesis. He found that dark-expanded leaves were consistently less negative in δ 13C than light-expanded leaves by 1 ‰. Terwilliger and Huang (1996) applied an inhibitor of carotene synthesis to allow chlorophyll-free leaves of Lycopersicon esculentum to grow alongside photosynthetic leaves on the same plant. They found that mature leaf δ 13Cp of the leaves that expanded without photosynthesis was 1–3 ‰ less negative than adjacent, simultaneously produced leaves that expanded with photosynthesis. Both of these experiments support the idea that leaf δ 13Cp becomes more negative during leaf expansion due to the progressive addition of the leaf’s own photosynthate to its structural carbon, with this photosynthate being fixed at relatively high ci/ca and therefore more negative δ 13C.

We found that deciduous species tended to have a larger δ 13Cp difference between mature and young leaves compared with evergreen species. We can think of two possible explanations for this. First, there could be additional fractionation associated with putting carbon into and taking it out of storage in deciduous species, such that the carbon that is used to reconstruct the canopy after a leafless period is less negative in δ 13C than the carbon that would be donated directly by mature, source leaves. There is some evidence in the literature to suggest that processes associated with carbon storage do lead to such 13C enrichment of the stored carbon pool (Gleixner et al., 1993, 1998; Damesin and Lelarge, 2003; Offermann et al., 2011). Second, it is possible that in deciduous species the contribution of the expanding leaf’s own photosynthesis to the mature leaf structural carbon is larger, due to lack of mature, source leaves exporting carbon at the time of new leaf emergence and expansion. Further research would be useful to help clarify the mechanism or mechanisms that lead deciduous species to have larger δ 13Cp differences between mature and young leaves than evergreen species.

The widespread nature of developmental depletion of δ 13Cp in leaves of C3 plants and the explanation reiterated here, but put forth previously (Evans, 1983; Francey et al., 1985; Evans et al., 1986; Cernusak et al., 2009a), have a number of important implications for interpreting leaf δ 13Cp. First, the average δ 13Cp of C3 leaves globally is probably depleted by about 2 ‰ compared to the δ 13C of global gross primary production of C3 plants. This can be seen, for example, in stems and roots having less negative δ 13C than leaves (Badeck et al., 2005; Cernusak et al., 2009a). This is a detail which may be useful to include in 13C-constrained global carbon cycle models (Francey et al., 1995; Lloyd et al., 1996; Battle et al., 2000; Kaplan et al., 2002; Keeling et al., 2017). Second, our analysis suggests that reconstruction of ci/ca from mature leaf δ 13Cp should be carried out using the relationship which is shown in eqn (2) above, with as = 4.4 ‰ and = 27 ‰ (Farquhar et al., 1982a, b). If one instead uses a more complete model which has been parameterized based on observations of how instantaneous ∆ 13C relates to ci/ca, this will cause ci/ca to be overestimated. This is because such a parameterization would not include the legacy effect of leaf expansion which causes ∆ 13C measured in mature leaf dry matter to be larger than instantaneous ∆ 13C measured in the same leaves. An example of this can be seen in a recent analysis in which the prediction of ci/ca with eqn (2) was made along with the prediction of a more complete model based on instantaneous ∆ 13C, with both compared to ci/ca measured by gas exchange (Bloomfield et al., 2019). In that example, the latter prediction overestimated the observed ci/ca. Third, the extent of depletion in δ 13Cp which occurs between young leaves and mature leaves may provide useful insight into the dynamics of carbon sources for leaf expansion, in terms of import from source leaves and storage vs. the leaf’s own photosynthesis (Terwilliger et al., 2001).

Finally, one of the most useful applications of leaf δ 13Cp for C3 plants is as an indicator of intrinsic water-use efficiency (Farquhar and Richards, 1984; Farquhar et al., 1989a). The relationship between intrinsic water-use efficiency and mature leaf δ 13Cp has generally been observed to be robust (Farquhar et al., 1989a; Cernusak et al., 2013; Cernusak, 2020). However, our analysis suggests that for young vs. mature leaves of C3 plants, higher δ 13Cp should not be interpreted as an indication of higher intrinsic water-use efficiency. Indeed, the pattern of change for intrinsic water-use efficiency as C3 leaves expand is just the opposite.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank John Evans and Susanne von Caemmerer for allowing us to use their facility for online measurements of ∆ 13C at the Australian National University. We also thank Aurelio Virgo and Jorge Aranda for technical assistance with plants grown at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute.

LITERATURE CITED

- Badeck FW, Tcherkez G, Nogues S, Piel C, Ghashghaie J. 2005. Post-photosynthetic fractionation of stable carbon isotopes between plant organs – a widespread phenomenon. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry 19: 1381–1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battle M, Bender ML, Tans PP, et al. 2000. Global carbon sinks and their variability inferred from atmospheric O2 and δ 13C. Science 287: 2467–2470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beringer J, Hutley LB, Abramson D, et al. 2015. Fire in Australian savannas: from leaf to landscape. Global Change Biology 21: 62–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloomfield KJ, Prentice IC, Cernusak LA, et al. 2019. The validity of optimal leaf traits modelled on environmental conditions. New Phytologist 221: 1409–1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks JR, Flanagan LB, Buchman N, Ehleringer JR. 1997. Carbon isotope composition of boreal plants: functional grouping of life forms. Oecologia 110: 301–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchmann N, Brooks JR, Ehleringer JR. 2002. Predicting daytime carbon isotope ratios of atmospheric CO2 within forest canopies. Functional Ecology 16: 49–57. [Google Scholar]

- Busch FA, Holloway-Phillips M, Stuart-Williams H, Farquhar GD. 2020. Revisiting carbon isotope discrimination in C3 plants shows respiration rules when photosynthesis is low. Nature Plants 6: 245–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Caemmerer S, Evans JR. 1991. Determination of the average partial pressure of CO2 in chloroplasts from leaves of several C3 plants. Australian Journal of Plant Physiology 18: 287–305. [Google Scholar]

- Cai Z-Q, Slot M, Fan Z-X. 2005. Leaf development and photosynthetic properties of three tropical tree species with delayed greening. Photosynthetica 43: 91–98. [Google Scholar]

- Cernusak LA. 2020. Gas exchange and water-use efficiency in plant canopies. Plant Biology 22(Suppl. 1): 52–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cernusak LA, Aranda J, Marshall JD, Winter K. 2007. Large variation in whole-plant water-use efficiency among tropical tree species. New Phytologist 173: 294–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cernusak LA, Arthur DJ, Pate JS, Farquhar GD. 2003. Water relations link carbon and oxygen isotope discrimination to phloem sap sugar concentration in Eucalyptus globulus. Plant Physiology 131: 1544–1554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cernusak LA, Goldsmith G, Arend M, Siegwolf RTW. 2019. Effect of vapor pressure deficit on gas exchange in wild-type and abscisic acid-insensitive plants. Plant Physiology 181: 1573–1586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cernusak LA, Hutley L, Beringer J, Tapper NJ. 2006. Stem and leaf gas exchange and their responses to fire in a north Australian tropical savanna. Plant Cell and Environment 29: 632–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cernusak LA, Tcherkez G, Keitel C, et al. 2009. a. Why are non-photosynthetic tissues generally 13C enriched compared to leaves in C3 plants? Review and synthesis of current hypotheses. Functional Plant Biology 36: 199–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cernusak LA, Ubierna N, Winter K, Holtum JAM, Marshall JD, Farquhar GD. 2013. Environmental and physiological determinants of carbon isotope discrimination in terrestrial plants. New Phytologist 200: 950–965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cernusak LA, Winter K, Aranda J, Virgo A, Garcia M. 2009b. Transpiration efficiency over an annual cycle, leaf gas exchange and wood carbon isotope ratio of three tropical tree species. Tree Physiology 29: 1153–1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choinski JS, Ralph P, Eamus D. 2003. Changes in photosynthesis during leaf expansion in Corymbia gummifera. Australian Journal of Botany 51: 111–118. [Google Scholar]

- Damesin C, Lelarge C. 2003. Carbon isotope composition of current-year shoots from Fagus sylvatica in relation to growth, respiration and use of reserves. Plant, Cell & Environment 26: 207–219. [Google Scholar]

- Damesin C, Rambal S, Joffre R. 1998. Seasonal and annual changes in leaf δ 13C in two co-occuring Mediterranean oaks: relations to leaf growth and drought progression. Functional Ecology 12: 778–785. [Google Scholar]

- Evans JR. 1983. Photosynthesis and nitrogen partitioning in leaves of Triticum aestivum L. and related species. PhD thesis, Australian National University, Canberra. [Google Scholar]

- Evans JR, von Caemmerer S. 2013. Temperature response of carbon isotope discrimination and mesophyll conductance in tobacco. Plant, Cell & Environment 36: 745–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans JR, Sharkey TD, Berry JA, Farquhar GD. 1986. Carbon isotope discrimination measured concurrently with gas exchange to investigate CO2 diffusion in leaves of higher plants. Australian Journal of Plant Physiology 13: 281–292. [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar GD, Ball MC, von Caemmerer S, Roksandic Z. 1982a. Effect of salinity and humidity on δ 13C value of halophytes – evidence for diffusional isotope fractionation determined by the ratio of intercellular/atmospheric partial pressure of CO2 under different environmental conditions. Oecologia 52: 121–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar GD, Cernusak LA. 2012. Ternary effects on the gas exchange of isotopologues of carbon dioxide. Plant, Cell & Environment 35: 1221–1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar GD, Ehleringer JR, Hubick KT. 1989a. Carbon isotope discrimination and photosynthesis. Annual Review of Plant Physiology and Plant Molecular Biology 40: 503–537. [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar GD, Hubick KT, Condon AG, Richards RA. 1989b. Carbon isotope fractionation and plant water-use efficiency. In: Rundel PW, Ehleringer JR, Nagy KA, eds. Stable isotopes in ecological research. New York: Springer, 21–46. [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar GD, O’Leary MH, Berry JA. 1982b. On the relationship between carbon isotope discrimination and the intercellular carbon dioxide concentration in leaves. Australian Journal of Plant Physiology 9: 121–137. [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar GD, Richards RA. 1984. Isotopic composition of plant carbon correlates with water-use efficiency in wheat genotypes. Australian Journal of Plant Physiology 11: 539–552. [Google Scholar]

- February EC, Higgins SI. 2016. Rapid leaf deployment strategies in a deciduous savanna. PLoS One 11: e0157833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francey RJ, Gifford RM, Sharkey TD, Weir B. 1985. Physiological influences on carbon isotope discrimination in huon pine (Lagarostrobos franklinii). Oecologia 66: 211–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francey RJ, Tans PP, Allison CE, Enting IG, White JWC, Trolier M. 1995. Changes in oceanic and terrestrial carbon uptake since 1982. Nature 373: 326–330. [Google Scholar]

- Gleixner G, Danier HJ, Werner RA, Schmidt HL. 1993. Correlations between the 13C content of primary and secondary plant products in different cell compartments and that in decomposing basidiomycetes. Plant Physiology 102: 1287–1290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleixner G, Scrimgeour C, Schmidt HL, Viola R. 1998. Stable isotope distribution in the major metabolites of source and sink organs of Solanum tuberosum L.: a powerful tool in the study of metabolic partitioning in intact plants. Planta 207: 241–245. [Google Scholar]

- Guehl JM, Bonal D, Ferhi A, Barigah TS, Farquhar GD, Granier A. 2004. Community-level diversity of carbon-water relations in rainforest trees. In: Gourlet-Fleury S, Guehl JM, Laroussinie O, eds. Ecology and management of a neotropical rainforest. San Diego: Elsevier, 75–94. [Google Scholar]

- Han Q, Kagawa A, Kabeya D, Inagaki Y. 2016. Reproduction-related variation in carbon allocation to woody tissues in Fagus crenata using a natural 13C approach. Tree Physiology 36: 1343–1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helle G, Schleser GH. 2004. Beyond CO2-fixation by Rubisco – an interpretation of 13C/12C variations in tree rings from novel intra-seasonal studies on broad-leaf trees. Plant, Cell & Environment 27: 367–380. [Google Scholar]

- Holtum JAM, Winter K. 2005. Carbon isotope composition of canopy leaves in a tropical forest in Panama throughout a seasonal cycle. Trees-Structure & Function 19: 545–551. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan JO, Prentice IC, Knorr W, Valdes PJ. 2002. Modeling the dynamics of terrestrial carbon storage since the Last Glacial Maximum. Geophysical Research Letters 29: 31-1–31-4. [Google Scholar]

- Keeling RF, Graven HD, Welp LR, et al. 2017. Atmospheric evidence for a global secular increase in carbon isotopic discrimination of land photosynthesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 114: 10361–10366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keitel C, Adams MA, Holst T, et al. 2003. Carbon and oxygen isotope composition of organic compounds in the phloem sap provides a short-term measure for stomatal conductance of European beech (Fagus sylvatica L.). Plant, Cell & Environment 26: 1157–1168. [Google Scholar]

- Le Roux-Swarthout DJ, Terwilliger VJ, Martin CE. 2001. Deviation between δ 13C and leaf intercellular CO2 in Salix interior cuttings developing under low light. International Journal of Plant Sciences 162: 1017–1024. [Google Scholar]

- Leavitt SW, Long A. 1985. Stable-carbon isotopic composition of maple sap and foliage. Plant Physiology 78: 427–429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Wang B, Chen T, et al. 2019. Leaf age compared to tree age pays a dominant role in leaf δ 13C and δ 15N of Qinghai Spruce (Picea crassifolia Kom.). Forests 10: 310. [Google Scholar]

- Li SG, Tsujimura M, Sugimoto A, Davaa G, Oyunbaatar D, Sugita M. 2007. Temporal variation of δ 13C of larch leaves from a montane boreal forest in Mongolia. Trees-Structure and Function 21: 479–490. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd J, Kruijt B, Hollinger DY, et al. 1996. Vegetation effects on the isotopic composition of atmospheric CO2 at local and regional scales: theoretical aspects and a comparison between rain forest in Amazonia and a boreal forest in Siberia. Australian Journal of Plant Physiology 23: 371–399. [Google Scholar]

- Lowdon JA, Dyck W. 1974. Seasonal variations in the isotope ratios of carbon in maple leaves and other plants. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 11: 79–88. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall JD, Zhang J. 1994. Carbon isotope discrimination and water-use efficiency in native plants of the North-Central Rockies. Ecology 75: 1887–1895. [Google Scholar]

- McNevin DB, Badger MR, Whitney SM, von Caemmerer S, Tcherkez GGB, Farquhar GD. 2007. Differences in carbon isotope discrimination of three variants of d-ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase reflect differences in their catalytic mechanisms. Journal of Biological Chemistry 282: 36068–36076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Offermann C, Ferrio JP, Holst J, et al. 2011. The long way down – are carbon and oxygen isotope signals in the tree ring uncoupled from canopy physiological processes? Tree Physiology 31: 1088–1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team . 2019. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- Raven JA, Farquhar GD. 1990. The influence of N metabolism and organic acid synthesis on the natural abundance of isotopes of carbon in plants. New Phytologist 116: 505–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebetzke G, Condon A, Farquhar G, Appels R, Richards R. 2008. Quantitative trait loci for carbon isotope discrimination are repeatable across environments and wheat mapping populations. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 118: 123–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards RA, Rebetzke GJ, Condon AG, van Herwaarden AF. 2002. Breeding opportunities for increasing the efficiency of water use and crop yield in temperate cereals. Crop Science 42: 111–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobrado MA, Ehleringer JR. 1997. Leaf carbon isotope ratios from a tropical dry forest in Venezuela. Flora 192: 121–124. [Google Scholar]

- Suh YJ, Diefendorf AF. 2018. Seasonal and canopy height variation in n-alkanes and their carbon isotopes in a temperate forest. Organic Geochemistry 116: 23–34. [Google Scholar]

- Tazoe Y, von Caemmerer S, Estavillo GM, Evans JR. 2011. Using tunable diode laser spectroscopy to measure carbon isotope discrimination and mesophyll conductance to CO2 diffusion dynamically at different CO2 concentrations. Plant, Cell & Environment 34: 580–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terwilliger VJ. 1997. Changes in the δ 13C values of trees during a tropical rainy season: some effects in addition to diffusion and carboxylation by Rubisco? American Journal of Botany 84: 1693–1700. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terwilliger VJ, Huang J. 1996. Heterotrophic whole plant tissues show more 13C enrichment than their carbon sources. Phytochemistry 43: 1183–1188. [Google Scholar]

- Terwilliger VJ, Kitajima K, Le Roux-Swarthout DJ, Mulkey S, Wright SJ. 2001. Intrinsic water-use efficiency and heterotrophic investment in tropical leaf growth of two Neotropical pioneer tree species as estimated from δ 13C values. New Phytologist 152: 267–281. [Google Scholar]

- Tipple BJ, Ehleringer JR. 2018. Distinctions in heterotrophic and autotrophic-based metabolism as recorded in the hydrogen and carbon isotope ratios of normal alkanes. Oecologia 187: 1053–1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ubierna N, Cernusak LA, Holloway-Phillips M, Busch FA, Cousins AB, Farquhar GD. 2019. Critical review: incorporating the arrangement of mitochondria and chloroplasts into models of photosynthesis and carbon isotope discrimination. Photosynthesis Research 141: 5–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ubierna N, Farquhar GD. 2014. Advances in measurements and models of photosynthetic carbon isotope discrimination in C3 plants. Plant, Cell & Environment 37: 1494–1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitoria AP, Vieira TdO, Camargo PdB, Santiago LS. 2016. Using leaf δ 13C and photosynthetic parameters to understand acclimation to irradiance and leaf age effects during tropical forest regeneration. Forest Ecology and Management 379: 50–60. [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Albert LP, Lopes AP, et al. 2016. Leaf development and demography explain photosynthetic seasonality in Amazon evergreen forests. Science 351: 972–976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Serbin SP, Xu X, et al. 2017. The phenology of leaf quality and its within-canopy variation is essential for accurate modeling of photosynthesis in tropical evergreen forests. Global Change Biology 23: 4814–4827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L, Baldocchi DD. 2003. Seasonal trends in photosynthetic parameters and stomatal conductance of blue oak (Quercus douglasii) under prolonged summer drought and high temperature. Tree Physiology 23: 865–877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshie F, Kawano S. 1986. Seasonal changes in photosynthetic characteristics of Pachysandra terminalis (Buxaceae), an evergreen woodland chamaephyte, in the cool temperate regions of Japan. Oecologia 71: 6–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]