Abstract

Background and Aims

Branching is an important mechanism of plant shape establishment and the direct consequence of axillary bud outgrowth. Recently, hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) metabolism, known to be involved in plant growth and development, has been proposed to contribute to axillary bud outgrowth. However, the involvement of H2O2 in this process remains unclear.

Methods

We analysed the content of H2O2 during bud outgrowth and characterized its catabolism, both at the transcriptional level and in terms of its enzymatic activities, using RT–qPCR and spectrophotometric methods, respectively. In addition, we used in vitro culture to characterize the effects of H2O2 application and the reduced glutathione (GSH) synthesis inhibitor l-buthionine sulfoximine (BSO) on bud outgrowth in relation to known molecular markers involved in this process.

Key Results

Quiescent buds displayed a high content of H2O2 that declined when bud outgrowth was initiated, as the consequence of an increase in the scavenging activity that is associated with glutathione pathways (ascorbate–glutathione cycle and glutathione biosynthesis); catalase did not appear to be implicated. Modification of bud redox state after the application of H2O2 or BSO prevented axillary bud outgrowth by repressing organogenesis and newly formed axis elongation. Hydrogen peroxide also repressed bud outgrowth-associated marker gene expression.

Conclusions

These results show that high levels of H2O2 in buds that are in a quiescent state prevents bud outgrowth. Induction of ascorbate–glutathione pathway scavenging activities results in a strong decrease in H2O2 content in buds, which finally allows bud outgrowth.

Keywords: Ascorbate–glutathione cycle, branching, bud outgrowth, glutathione synthesis, hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), reactive oxygen species (ROS), rosebush (Rosa ‘Radrazz’)

INTRODUCTION

Branching constitutes an essential developmental process in the establishment of plant shape and results from a spatio-temporal regulation of axillary bud functioning (Evers et al., 2011; Rameau et al., 2015). Buds can remain quiescent or sprout to form new axes and consequently condition the branching scheme of plants. Bud growth resumes from a quiescent state after the reception of appropriate signals that trigger bud outgrowth (Beveridge et al., 2000, 2003). This complex mechanism is regulated internally by the genetic background (Li-Marchetti et al., 2015) and also through different nutrition/signalling pathways such as phytohormones (Domagalska and Leyser, 2011; Müller and Leyser, 2011), sugars (Henry et al., 2011; Mason et al., 2014; Barbier et al., 2015a, b, 2019b) and nitrogen (Huché-Thélier et al., 2011; Furet et al., 2014; Le Moigne et al., 2018). Furthermore, fine tuning of the branching pattern is under the control of environmental factors, allowing the plants to cope with environmental constraints (Evers et al., 2011).

The transition of buds from a quiescent to an actively growing state relies on two major mechanisms: the resumption of cell division and cell elongation. Previous studies showed in several species that the quiescent axillary bud cells are paused at the G1 phase of the cell cycle and resume to the S phase when bud outgrowth is induced (Devitt and Stafstrom, 1995; Horvath et al., 2003; Chao et al., 2007). This transition is under the control of genes encoding cyclins (CYC) or involved in their regulation (Devitt and Stafstrom, 1995). These genes were characterized as being upregulated at the onset of bud outgrowth in the quiescent bud (Shimizu and Mori, 1998a; Roman et al., 2016; Pérez and Noriega, 2018). Similarly, PCNA (PROLIFERATING CELL NUCLEAR ANTIGEN), identified as a key factor in DNA replication and cell cycle regulation, is also induced during bud outgrowth (Shimizu and Mori, 1998a, b; Strzalka and Ziemienowicz, 2011), notably in rosebushes, apple trees and grapevine (Roman et al., 2016; Li et al., 2018; Meitha et al., 2018). Molecular genetic approaches allowed the identification of additional genes implicated in bud outgrowth. BRC1 (BRANCHED 1), encoding a TCP transcription factor (TEOSINTE BRANCHED1, CYCLOIDEA, PCF; Aguilar-Martínez et al., 2007; Dun et al., 2009), has been particularly studied, and was considered an important hub in the control of bud outgrowth since it was found to control the expression of cyclin genes (González-Grandío et al., 2013). Cell elongation is another process of bud outgrowth essential in bringing the pre- and neoformed organs produced by the axillary bud meristem to their final size. This process involves the transcription of genes encoding expansins and extensins (Mathiason et al., 2009; Dal Santo et al., 2011; Roman et al., 2016, 2017; Sudawan et al., 2016), which relax the cell wall to allow its expansion and consequently the elongation of the axis resulting from budburst. These mechanisms are dependent on repressing (auxin, strigolactones) or stimulating (mainly cytokinins) phytohormones (Rameau et al., 2015) and have been shown to be linked to the redox status (Jiang et al., 2003; Wang et al., 2006)

Reactive oxygen species (ROS), small ubiquitous reactive molecules derived from a partial reduction of oxygen, constitute major components of redox plant metabolism (Considine and Foyer, 2014; Das and Roychoudhury, 2014; Mittler, 2017). Long considered as toxic rubbish of aerobic metabolism, ROS are nowadays increasingly seen in plants as essential actors in many physiological processes, such as root growth, flowering, fruiting and seed germination (Henmi et al., 2007; Mhamdi and Van Breusegem, 2018). In contrast to other ROS-related molecules, whose half-life is extremely short, hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) lasts long enough in cells to see its quantity regulated through production/scavenging activities (Mhamdi and Van Breusegem, 2018). The scavenging system relies on two major modalities: (1) a non-enzymatic modality, involving different classes of molecules, such as polyphenols, carotenoids, ascorbate and glutathione, the last of these being of primary importance (Barnes et al., 2002); and (2) an enzymatic modality, based on several specific activities, such as catalase or peroxidases. Catalase (EC 1.11.1.6), a tetrameric haem-containing enzyme, is able to degrade H2O2 to H2O and O2 without requiring any reducing molecule. Widely present in plant tissues, it is particularly concentrated in peroxisomes (Mittler, 2002). Catalase is encoded by three genes in arabidopsis, maize and rice that are developmentally and spatially regulated (Mhamdi et al., 2010a, b). Peroxidases, mainly ascorbate and glutathione peroxidases (EC 1.1.11.1 and EC 1.11.1.9, respectively), are also strongly involved in the regulation of H2O2 content and are present in all cell compartments (Das and Roychoudhury, 2014). Moreover, ascorbate peroxidase (APX) is an integral component of the ascorbate–glutathione cycle, and glutathione reductase (GR, EC 1.6.4.2), involved in the regeneration of GSH, is finally used to regenerate ascorbate (Foyer and Noctor, 2011). Management of H2O2 scavenging is also regulated through the different affinities of enzymes for H2O2: coarse degradation is performed by catalase (low affinity, mm range) while fine tuning relies on APX (high affinity, µm range; Gill and Tuteja, 2010). An increasing number of reports integrate variations of H2O2 content in the regulation of different plant development processes (Liu et al., 2013; Zang et al., 2020).

Interestingly, a link between H2O2 metabolism and bud outgrowth was suggested by several studies. The application of chemicals or physical treatments (sodium azide, hydrogen cyanamide, heat shock) induces an marked H2O2 peak, resulting from a transient inhibition of catalase and respiration, that promotes bud outgrowth (Or et al., 2002; Pérez et al., 2008; Ophir et al., 2009; Vergara et al., 2012; Sudawan et al., 2016; Meitha et al., 2018). This mechanism is rather close to seed dormancy release, which is also induced by hydrogen cyanamide (Oracz et al., 2009; Cooke et al., 2012). In parallel, H2O2 appears also to be involved in bud outgrowth in the actively growing plant. Studies involving rboh mutant plants altered in their capacity to produce apoplastic H2O2 that displayed a highly branched phenotype suggested that H2O2 is involved in bud outgrowth inhibition (Sagi et al., 2004; Chen et al., 2016). However, the time-course of bud H2O2 content in wild-type plants and its metabolism have, to our knowledge, never been investigated during a natural bud outgrowth process.

In the present study, we aimed to characterize H2O2 abundance and metabolism in quiescent buds and during the outgrowth process. We showed that the H2O2 content is high in quiescent buds and decreases during the outgrowth process. We established that this decrease is a result of the activation of ascorbic acid (AsA)–GSH scavenging activity, while catalase appears to be a minor actor.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Growth conditions and sample harvest

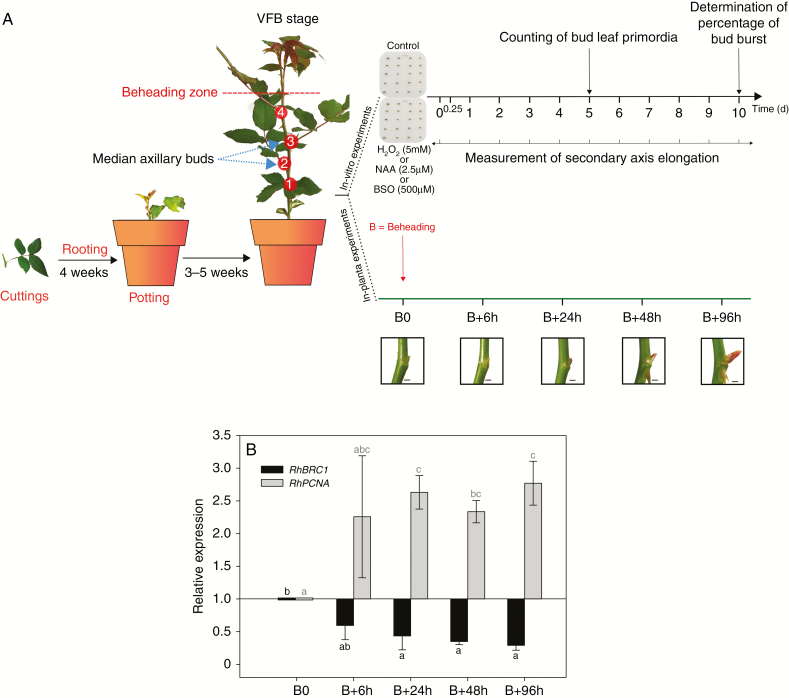

All experiments were carried out using plants from of a single clone of Rosa ‘Radrazz’ KNOCK OUT. Plants were grown as described earlier (Furet et al., 2014). When the plants reached the developmental stage where the apical flower bud is visible (VFB, Fig. 1A), they could be used for in vitro or in planta experiments (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Experimental plan and validation of the study model. (A) The plant model (Rosa ‘Radrazz’) was cultivated in a greenhouse until the visible floral bud (VFB) stage. At this stage, we numbered the different buds from 1 (basal) to 4 and determined the beheading zone 1 cm above the fourth bud. For in vitro experiments, the different buds (first to fourth) were grown in culture medium in the presence or absence of 5 mm H2O2, 2.5 µm NAA for 10 d or 500 µm BSO for 5 d. Samples were harvested at different times after culture set-up for the quantification of H2O2 content or gene expression. In parallel, for in planta experiments buds and node tissues were harvested at different times after beheading time (B0): B+6 h, B+24 h, B+48 h, B+96 h. Samples were used for measuring H2O2 content, gene expression and enzyme activities at each sampling time and GSH and GSSG contents at 0, 24 and 96 h. Scale bars = 2 mm. (B) Relative accumulation in median buds at different times after beheading (B) of transcripts of RhBRC1 (BRANCHED1) involved in the inhibition of shoot branching and RhPCNA (PROLIFERATING CELL NUCLEAR ANTIGEN), involved in mitosis processes, both already implicated in the bud outgrowth mechanism in rosebush. Data are means of n = 3 biological independent replicates ± s.e. Black and grey letters indicate significant differences for RhBRC1 and RhPCNA, respectively, after a Kruskal–Wallis non-parametric test.

In planta experiments

The plants were beheaded by removing the upper part 1 cm above the fourth basal five-leaflet leaf. After beheading, a typical plant displays an unbranched axis carrying four nodes, each bearing axillary buds: the upper (youngest) one (numbered 4), the two located immediately below (numbered 3 and 2, named ‘median buds’), and the oldest, basal node, numbered 1. The plants were then placed in a controlled growth chamber under white light (300–350 µmol m−2 s−1, light:dark 16:8 h, 22:19 °C) in fertilized substrate (1 kg m−3 PgMix™ 14:16:18-Mg trace elements; Yara, Nanterre, France) and fertirrigated with a nutrient solution (15:10:30: Fe 1.2; Plant-Prod). Harvests of median axillary buds (pool of second and third buds) and associated leaves and nodes were performed at beheading time (B0) and 6, 24, 48 and 96 h later (Fig. 1A). We performed a total of three independent biological replicates, each consisting of at least three independent experiments containing a minimum of 20 plants.

In vitro culture experiments

Stem fragments carrying axillary buds were grown in vitro as previously described (Le Moigne et al., 2018). The culture medium was supplemented in test samples with 5 mm H2O2, 2.5 µm naphthaleneacetic acid (NAA) or 500 µm l-buthionine sulfoximine (BSO; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). These concentrations were successfully used in a similar context in previous studies (Takahashi et al., 2014; Chen et al., 2016). Samples were placed in Petri dishes in a controlled environment (300–350 µmol m−2 s−1, light:dark 16:8 h, 22:19 °C for 5–10 d according to experiment). Elongation of secondary axes resulting from bud outgrowth was measured every day for 10 d using a numerical calliper (Fig. 1A). Percentage of bud outgrowth was calculated after 10 d, according to Girault et al. (2008). The number of bud leaf primordia was determined after bud dissection at T0 and after 5 d of culture in the presence or absence of 5 mm H2O2 (Fig. 1A). Buds cultured in vitro were harvested at different times after culture set-up depending on experiment. Data were obtained from three independent experiments, each consisting of a minimum of three technical replicates involving sets of 15 buds in a Petri dish.

Determination of H2O2 content in buds using chemiluminescence

Hydrogen peroxide levels were determined using a chemiluminescence method according to Lu et al. (2009). This H2O2 detection method was adapted and verified using rosebush tissues (Supplementary Data Fig. S1). Briefly, frozen tissues (20 mg) were ground in liquid nitrogen and homogenized in 500 µL of 5 % trichloroacetic acid containing 5 % (w/v) of insoluble polyvinylpolypyrrolidone (PVPP). The samples were centrifuged at 13 000 g for 10 min. The supernatant was collected and diluted 100-fold in 0.1 m sodium carbonate buffer (pH 10.2). Aliquots (40 µL) were incubated at 30 °C for 15 min in the presence of 0.5 milliunits of catalase (Catalase from bovine liver; Sigma) or an equivalent volume of distilled water. The quantity of H2O2 was assayed from 10 µL of incubated samples (catalase and water) in a microplate (white polypropylene MicroWell plate; Nunc, round bottom) after the addition of 250 µL of reaction mixture solution (65 µm luminol and 10 µm cobalt chloride solubilized in 0.1 m sodium carbonate buffer, pH 10.2). Luminescence was measured in a microplate reader (FLUOstar Omega; BMG Labtech) and the quantity of H2O2 was determined from a standard curve established from freshly prepared dilutions of commercial H2O2 (Sigma). The H2O2 content was corrected by subtracting the value of the samples containing catalase and expressed as µmol g−1 FW. Very weak luminescence signal was detected in the presence of catalase, demonstrating that the measured signal accurately reflects H2O2 levels in the plant tissues and does not result from interfering compounds (Noctor et al., 2016).

Soluble protein isolation and enzyme activity assay

We monitored the activities of GR, APX and catalase as reporters of ROS scavenging level. We adapted the protein extraction method to lignified tissues from Gill et al. (2015). Approximately 100 mg of buds was ground in liquid nitrogen in the presence of 10 % PVPP (w/w). The powder was homogenized on ice with 1 mL of 100 mm potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.8) containing 2 mm dithiothreitol, 1 mm EDTA and 1.25 mm PEG4000. The homogenate was centrifuged at 13 500 g for 15 min at 4 °C and the supernatant was collected and purified on a Nap-5 column (GE Healthcare) to clarify samples. Total soluble protein content was determined using the standard Bradford assay (Bio-Rad Protein Assay). The activity of GR was determined by monitoring the decrease in A340nm at 25 °C according to Jiang and Huang (2001) and expressed as nmol of NADPH consumed per minute and per mg of protein. APX activity was measured according to Nakano and Asada (1981) for 5 min at 25 °C and expressed as nmol of ascorbic acid consumed per minute and per mg of protein. Catalase enzymatic activity was determined for 5 min at 25 °C and expressed as µmol of H2O2 consumed per minute and per mg of protein.

Assay of reduced and oxidized glutathione and ratio determination

The GSH and oxidized glutathione (GSSG) contents of rose buds during outgrowth were determined by an adaptation of the GSH-GSSG-Glo™ Assay kit method (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). The modification consisted of adding an acid extraction followed by a neutralization step. To achieve this, 50 mg of median bud tissue was ground in liquid nitrogen and homogenized on ice in 500 µL of HCl (0.2 m). Samples were centrifuged at 15 000 g for 10 min at 4 °C, and 200 µL of supernatant was collected in new tubes. Neutralization was carried out by the addition of 40 µL of 0.2 m phosphate buffer (pH 5.6) and the extracts were adjusted to pH 4–5 with 0.2 m NaOH (Noctor et al., 2016). The added volumes were noted for calculations (typically 160 µL per sample for rose buds). The neutralized extracts were used for the GSH-GSSG assay using the commercial protocol established for ‘suspension cells’ (available at www.promega.com). Quantities of GSH and GSSG were calculating as nmol−1 g−1 FW after taking into account the neutralization step.

Gene identification and phylogenetic analysis

Sequences of GRs, APXs and CAT were retrieved by similarity of arabidopsis mRNA sequences (Arabidopsis thaliana, https://www.arabidopsis.org) to those of Rosa chinensis available at https://www.rosaceae.org. Multiple sequence alignments were performed using ClustalW with basic parameters in MEGA X® software (Kumar et al., 2018). Phylogenetic analyses were performed using a maximum likelihood approach with the Tamura–Nei model (Tamura and Nei, 1993). The test of phylogeny to construct the phylogenetic tree was done using the bootstrap method with 500 replications using MEGA X® software. Sequences of Rosa genes were named according to Arabidopsis gene annotation.

Primer design for genes of interest

The expression of different genes of interest was analysed using RT–qPCR. Primers were designed using R. chinensis sequences obtained at https://www.rosaceae.org. The primer sequences were designed using the online software Primer3Plus (http://www.bioinformatics.nl/primer3plus) with standard parameters enabling the design of amplicons with a size of 100–250 base pairs. These amplicons were verified on Rosa ‘Radrazz’ cDNA material by PCR. All primer sequences used in this study are available in Supplementary Data Tables S1 and S2.

Total RNA extraction, reverse transcription and RT–qPCR

Approximately 20 mg of frozen tissue was ground in liquid nitrogen and used as the source for total RNA isolation using a phenol/chloroform-free method developed by Barbier et al. (2019a, b). The RNA quantities and qualities were checked using Nanodrop One (Thermo Scientific), completed with an analysis on agarose gel to check integrity. cDNA synthesis was achieved from 300 ng of total RNA, using iScript Reverse Transcription Supermix for RT–qPCR (Bio-Rad). The qPCR was carried out in a final volume of 15 µL with a mix containing 50-fold diluted cDNA, primer pairs (Supplementary Data Tables S1 and S2) and iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad) using the following amplification programme: initiation at 98 °C for 30 s, 40 cycles of 5 s at 95 °C and 30 s at 60 °C, and finally a melting curve with an increase of 0.5 °C every 2 s to 95 °C. Fluorescence was detected using the CFX Connect Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad). The abundance of transcripts was expressed relative to the control condition according to the method described by Pfaffl (2001) after normalization with the reference genes RhUBC (UBIQUITIN CONJUGATING ENZYME E2) and RhTCTP (TRANSLATIONALLY CONTROLLED TUMOR PROTEIN), described as reliable genes for normalization (Han et al., 2012) and previously used in rosebush materials (Hibrand Saint-Oyant et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2019).

Statistical analysis

All data were obtained with a minimum of three biologically independent replicates and at least two different technical replicates. Statistical analysis was performed using the statistical software R (R Core Team, 2017). Graphics were drawn using Sigmaplot 11.0 and Inkscape 0.92 software.

RESULTS

We focused on in planta beheading experiments and harvesting of median buds at various time-points to evaluate the possible modification of redox status in rose buds during the outgrowth process (Fig. 1A). After beheading (B0), apical dominance is released, and outgrowth of quiescent buds is initiated and becomes visible 48 h after beheading (Fig. 1A). We measured the expression of different marker genes previously studied in the rosebush bud outgrowth mechanism to confirm that the chosen time-course is appropriate for the analysis of the phenomenon (Fig. 1B and Supplementary Data Fig. S2). Transcript accumulation of the bud outgrowth inhibitor gene RhBRC1 decreased after beheading and remained significantly lower after 24 h (2- to 3-fold, black bars in Fig. 1B). Conversely, transcript accumulation of the RhPCNA gene (known to be activated during outgrowth) significantly increased from 24 h after beheading (2.5-fold, grey bars in Fig. 1B). These results validated the beheading treatment and the harvest time-course used to study the bud outgrowth process.

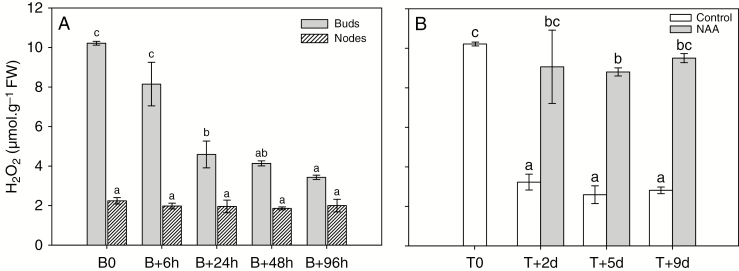

H2O2 abundance is critical for the axillary bud outgrowth process

In order to evaluate the modification of ROS status during bud outgrowth, we measured the H2O2 quantities in median buds (pools of second and third buds; Fig. 1A) and associated nodes at different time-points after beheading (Fig. 2A). First, we established a contrasted course of H2O2 content between buds and nodes during the outgrowth process: it was low in the nodes (2.2 µmol g−1 FW; Fig. 2A, B0 hatched bars) and was much higher in the quiescent buds, where it remained constant (10.3 µmol g−1 FW; Fig. 2A, B0 grey bars). Hydrogen peroxide decreased continuously from 6 to 96 h after beheading (Fig. 2A, B+6 h to B+96 h) to reach a value of 3.5 µmol g−1 FW after 96 h (it is worth noting that the content of H2O2 in buds was then approaching the content in nodes). This decrease even preceded the emergence of the new axis of the bud scales (B+6 h, B+24 h, Fig. 2A). In parallel, the presence of 2.5 µm NAA (an auxin homologue), which prevented bud outgrowth in vitro (Supplementary Data Fig. S3), also caused H2O2 to remain at a high level that was comparable to that measured in quiescent buds (Fig. 2B). Therefore, we characterized the effects of H2O2 supply on bud outgrowth using excised nodes cultured in vitro (Fig. 1A). It is worth noting that the addition of 5 mm H2O2 to the culture medium did not cause a massive increase in H2O2 content in buds but rather maintained it at that observed in quiescent buds (Fig. 3A). In these conditions, the formation of leaf primordia in buds was strongly inhibited (Fig. 3B); their number (about 7–8) remained constant after 5 d when the culture medium was supplemented with 5 mm H2O2, while the untreated control displayed at this time more than 11 primordia (Fig. 3B). Additionally, the proportion of outgrowing buds was considerably lowered (particularly the upper ones) in the presence of H2O2 (between 20 and 50 %) compared with that observed in untreated samples (80–100 %; Fig. 3C). Hydrogen peroxide also severely reduced the elongation of the newly formed secondary axis (from 50 to 80 % depending on bud position (Fig. 3D, black symbols) compared with the untreated samples (Fig. 3D, open symbols).

Fig. 2.

Course of H2O2 content in buds in relation to the bud outgrowth process. (A) H2O2 content, measured by chemiluminescence, in median buds (pool of second and third buds; Fig. 1A) and excised nodes (without associated buds) at beheading time (B0) and at different times after beheading. (B) H2O2 content in buds 2, 5 and 9 d after in vitro culture set-up (T0) of excised nodes in the presence (grey bars) or absence (white bars) of 2.5 µm of NAA. Data are means of n = 3 independent biological replicates ± s.e. Letters indicate significant differences after a Kruskal–Wallis non-parametric test for each organ.

Fig. 3.

Effects of H2O2 on bud outgrowth. (A) H2O2 content in buds 2, 5 and 9 d after in vitro culture set-up (T0) of excised nodes in the presence (grey bars) or absence (white bars) of 5 mm H2O2. Letters indicate significant differences after a Kruskal–Wallis non-parametric test. (B) Number of leaf primordia in each bud in control condition before culture set-up (white bar) or after 5 d of in vitro culture in the presence (black bar) or absence (grey bar) of 5 mm H2O2. Significant differences between 5-d-old buds and reference and between the treatment conditions are indicated by asterisks and hash symbols, respectively. (C) Percentage of bud outgrowth according to bud position on stem (Fig. 1A, basal bud 1) after 10 d of in vitro culture in the presence (black bars) or absence (white bars) of H2O2. Pictures on the right correspond to bud morphologies in the different medium conditions in the absence (white frames) and presence (black frames) of 5 mm H2O2. Significant differences between control and H2O2-treated conditions are indicated by asterisks. (D) Elongation of secondary axis for the four different bud positions on the stem after 9 d of in vitro culture in the presence (black symbols) or absence (open symbols) of 5 mm H2O2. Significant differences between control and H2O2-treated conditions for each kinetic time are indicated by asterisks. Data are means of n > 3 independent biological replicates ± s.e., and significant differences at confidence range of 95% are indicated: P < 0.05 (*), P < 0.01 (**) and P < 0.001 (*** and ###) (Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney non-parametric test).

Central role of H2O2 scavenging in bud outgrowth

The marked reduction in the quantity of H2O2 in buds during the outgrowth process (Fig. 2A) led us to consider the activity of H2O2 detoxification pathways, particularly that of the ascorbate–glutathione cycle and catalase, by measuring both transcript abundances and enzyme activities.

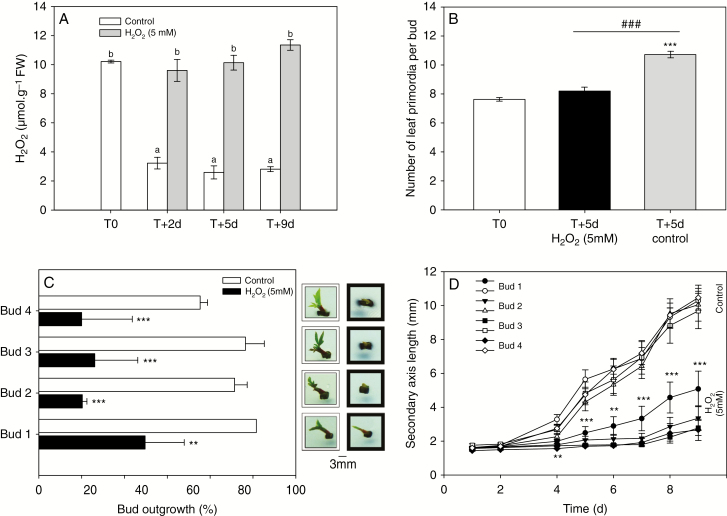

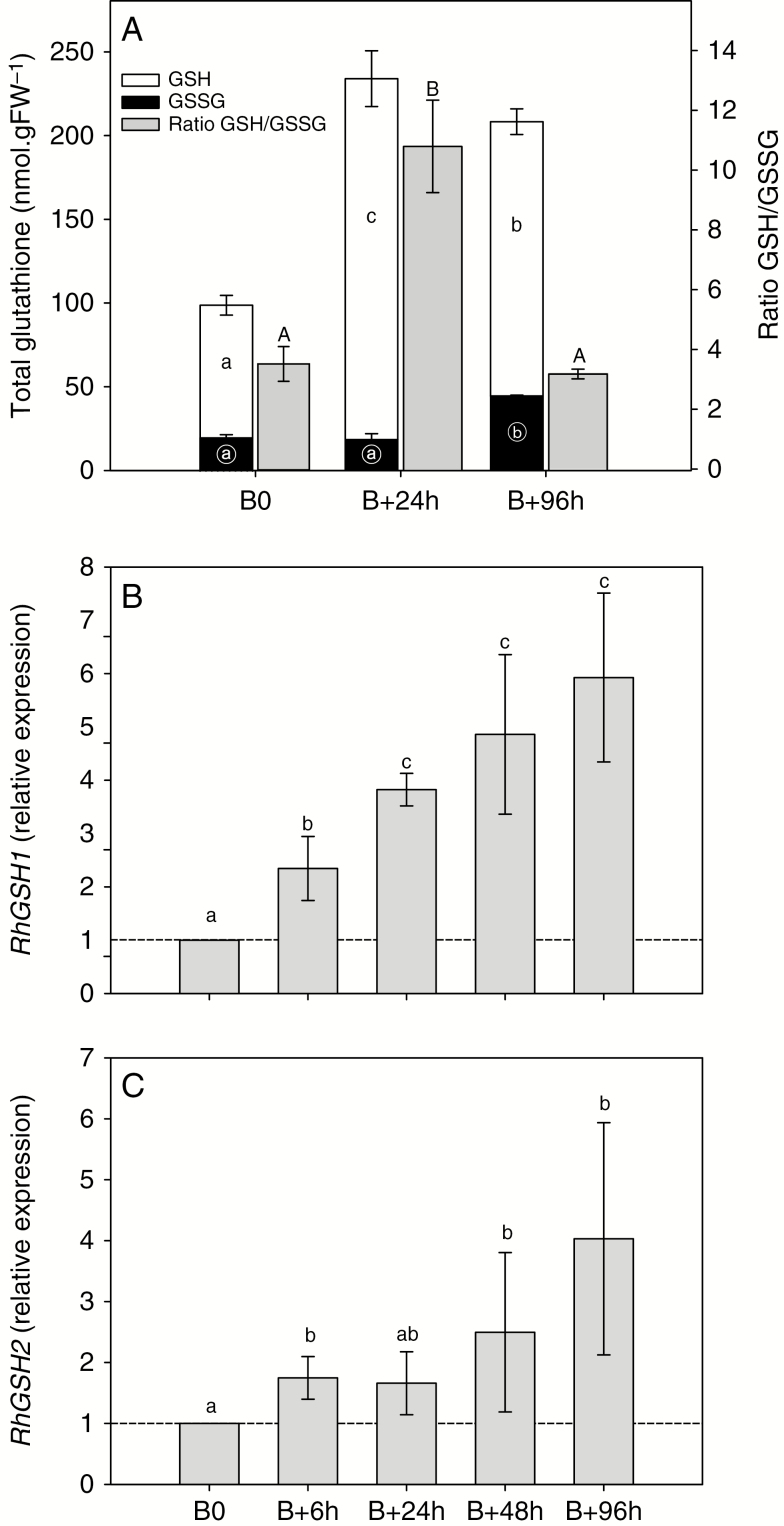

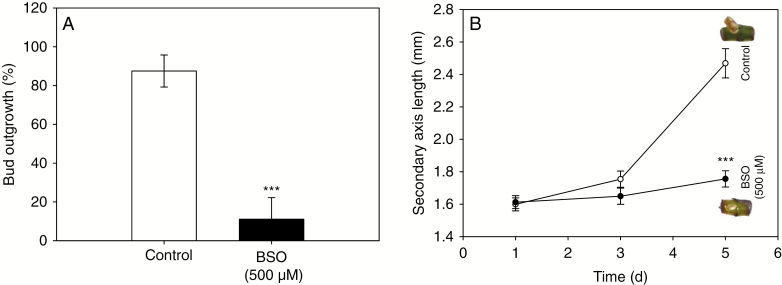

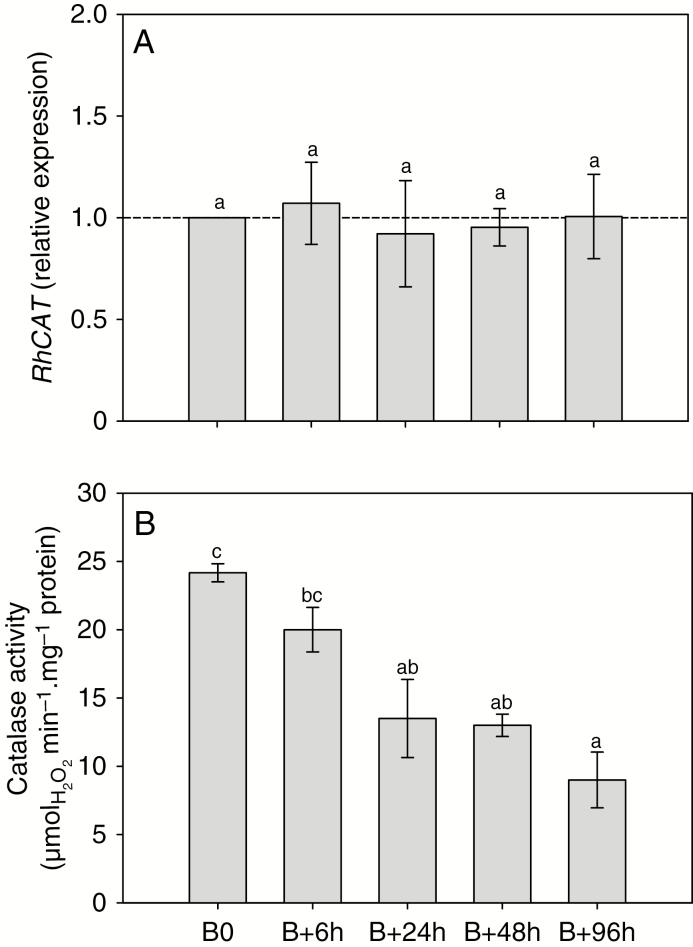

Accumulation of APX (a major enzyme in the AsA-GSH cycle; Supplementary Data Figs S4 and S5) RhAPX1 transcript increased (1.6-fold) after beheading and differed significantly between 24 and 96 h (Fig. 4A). The expression of the isoform RhAPX6 also increased continuously after beheading and became significantly different (1.6-fold) after 48 h (Fig. 4B). These increases in RhAPX gene expression were concordant with the overall APX activity, which increased by 2.2-fold after beheading and was significantly different after 48 h (Fig. 4E). Glutathione reductase, another major enzyme of the AsA–GSH cycle (Supplementary Data Fig. S5), is encoded by two gene isoforms that behaved differently during the bud outgrowth process in Rosa. The cytoplasmic isoform (RhGR1; Supplementary Data Fig. S4B) mRNA abundance massively increased after beheading and became significantly different (1.5- to 4.5-fold) after 6 h (Fig. 4C). In contrast, the mRNA abundance of the plastid-located isoform (RhGR2; Supplementary Data Fig. S4B) remained constant after beheading and therefore appeared not to be implicated (Fig. 4D). The total activity of GR was closely correlated with RhGR1 transcript accumulation (r2 = 0.99, P = 0.002; Supplementary Data Fig. S6): GR activity increased continuously after beheading and became significantly different after 48 h (~2-fold; Fig. 4F), when the new axis protruded from the bud scales (Fig. 1A). In view of these results, it appeared important to quantify glutathione in its reduced (GSH) and oxidized (GSSG) forms to highlight major changes in their quantities and ratio during the bud outgrowth process. Total glutathione content (GSH + GSSG) increased by 2.3-fold after beheading (Fig. 5A) and remained at a high level (~225 nmol g−1 FW) during the entire outgrowth process. This increase mainly relied on the reduced (GSH) form, which was dramatically increased (2.8-fold) 24 h after beheading (Fig. 5A, white bars). This was accompanied by an large increase in GSH/GSSG ratio (from 4 to 11.7, grey bars), since the quantity of GSSG remained essentially constant. A significant but much lower increase in the oxidized form (GSSG) occurred at 96 h and appeared to result from the conversion of the reduced to the oxidized form (2.5-fold, black bars), as suggested by the diminution of the GSH/GSSG ratio, which displayed a massive drop at 96 h to reach a value of 3.7, close to that observed at B0. These variations in total glutathione content and reduced/oxidized form ratio could also result from an alteration of glutathione synthesis. Indeed, the expressions of the two genes involved in the glutathione biosynthesis pathway, namely RhGSH1 and RhGSH2, which encode glutamate-cysteine ligase (GCL) and glutathione synthetase, respectively, were induced during bud outgrowth and were significantly higher by 6 h after beheading (Fig. 5B, C). These increases in both glutathione biosynthesis and GSH recycling (Fig. 4C, F), along with the increase in total glutathione (Fig. 5A), suggested a direct involvement of glutathione in the bud outgrowth mechanism. To test this hypothesis, we used BSO as an inhibitor of glutathione synthesis. Addition of 500 µm BSO to the culture medium strongly decreased the glutathione content in buds (Supplementary Data Fig. S7) and induced a marked decline in bud outgrowth (7.8-fold) after 5 d of in vitro culture (Fig. 6A). Treatment with BSO also strongly repressed elongation of the new axis compared with the control samples (Fig. 6B). Accumulation of mRNA of the other major H2O2 scavenger, catalase, encoded by a single gene in rosebush (RhCAT; Supplementary Data Fig. S4C), remained constant from beheading time (B0) to 96 h (Fig. 7A), while the corresponding enzyme activity decreased by ~44 and 62 % at 24 and 96 h after beheading (Fig. 7B), along with the quantity of H2O2 (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 4.

Transcript accumulation and enzymatic activity involved in the ascorbate–glutathione cycle during the bud outgrowth process. Transcript accumulation of (A) RhAPX1, (B) RhAPX6 (two cytoplasmic forms of APX-encoding genes), (C) RhGR1 (cytoplasmic form) and (D) RhGR2 (plastid form) in median buds during bud outgrowth [0–96 h; B0 (time of beheading), B+6h, ... B+96h] induced by beheading. (E, F) Course of (E) total APX activity and (F) total GR activity during bud outgrowth induced by beheading. Data are means of n = 3 biological independent replicates ± s.e. Letters indicate significant differences after Kruskal–Wallis non-parametric test for each panel.

Fig. 5.

Modification of GSH/GSSG content and transcript accumulation of glutathione biosynthesis genes during bud outgrowth. (A) Contents of reduced (GSH, white bars) and oxidized (GSSG, black bars) forms of glutathione in median buds (pool of second and third buds; Fig. 1) at beheading time (B0) and 24 and 96 h after beheading. The GSH/GSSG ratio is shown (grey bars) for each time point. (B, C) Transcript accumulation of (B) RhGSH1 and (C) RhGSH2, involved in the glutathione biosynthesis pathway during the bud outgrowth process. Data are means of n = 3 independent biological replicates ± s.e. Lower- and upper-case letters indicate significant differences in contents of GSH and GSSG (lower-case) and the GSH/GSSG ratio (upper-case) after a Kruskal–Wallis non-parametric test. For RhGSH1 and RhGSH2 expression, the letters indicate significant differences in relative expression levels after a Kruskal–Wallis non-parametric test for each isoform.

Fig. 6.

Effect of BSO on GSH biosynthesis in bud outgrowth. (A) Percentage of bud outgrowth after 5 d of in vitro culture in the absence (white bar) or presence (black bar) of 500 µm BSO. (B) Elongation of new secondary axis after 5 d of in vitro culture in the presence (black circles) or absence (open circles) of 500 µm BSO. Morphologies of buds in the corresponding medium conditions are shown on the right. Data are means of n = 3 independent biological replicates ± s.e. *P < 0.001 at confidence range of 95% (Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney non-parametric test).

Fig. 7.

Transcript accumulation and activity of catalase during bud outgrowth. (A) Transcript accumulation of RhCAT and (B) course of catalase activity during bud outgrowth in median buds during bud outgrowth. B0, time of beheading. Data are means of n = 3 biological independent replicates ± s.e. Letters indicate significant differences after a Kruskal–Wallis non-parametric test.

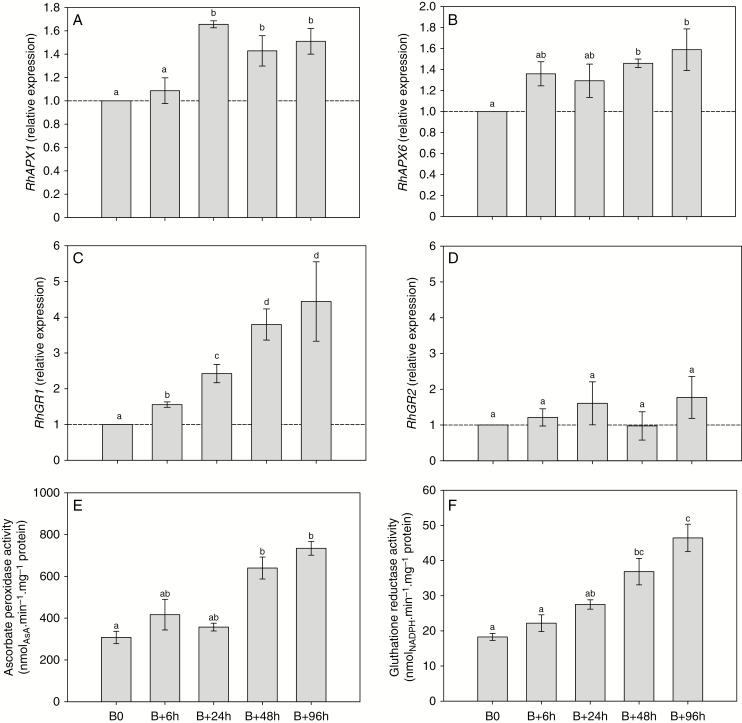

H2O2 interaction with the major actors in bud outgrowth

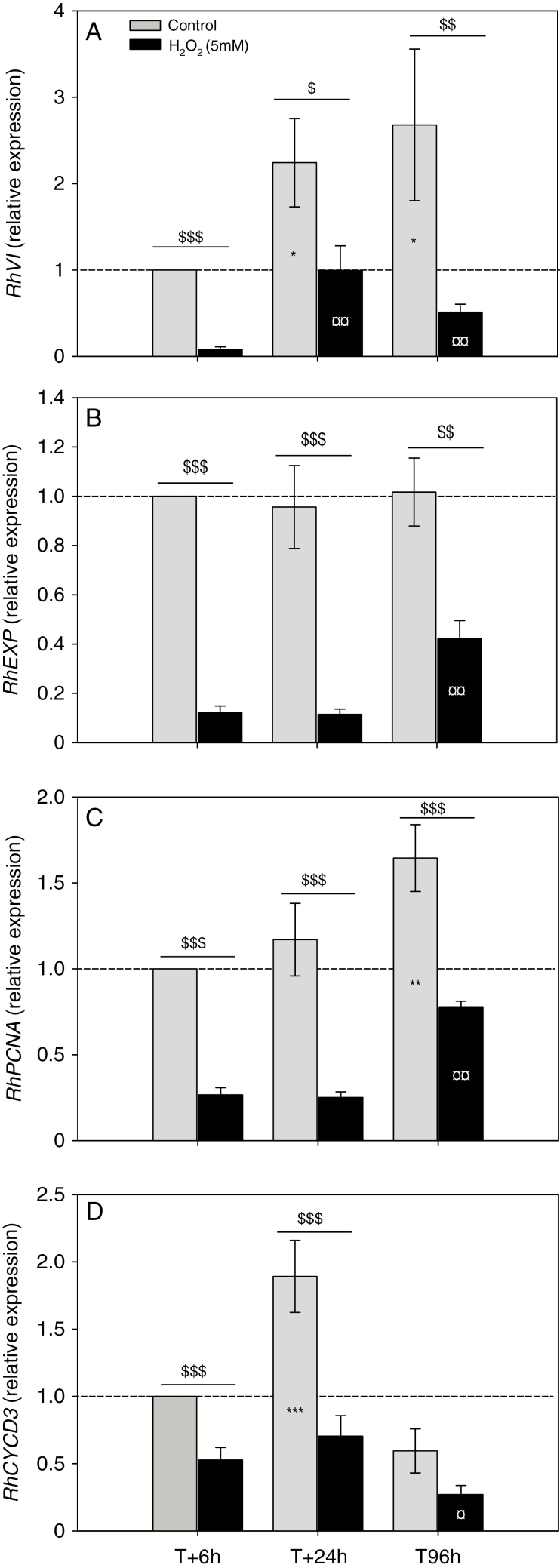

Since the exogenous application of 5 mm H2O2 kept endogenous H2O2 at the level observed in quiescent buds, we analysed in this condition its impact on the expression of previously identified key genes in bud outgrowth (Figs 8 and 9). Transcript accumulation of RhVI (vacuolar invertase), involved in bud carbohydrate nutrition, was induced during bud outgrowth in control conditions in planta and in vitro (Fig. 8A, grey bars; Supplementary Data S1A). However, the expression of this gene was consistently lower in the presence of H2O2 (5- to 10-fold; Fig. 8A, black bars). The accumulation of expansin (RhEXP) transcript remained constant in control condition (Fig. 8B, grey bars) while the addition of H2O2 considerably lowered its abundance (2.5- to 8-fold; Fig. 8B, black bars). The same observation was performed for PCNA transcripts (Fig. 8C) while RhPCNA transcripts slightly increased in the control condition (Fig. 8C, grey bars). Inhibition was maximum at 6 and 24 h after the supply of H2O2 (4-fold) and still very significant at 96 h (2-fold). The expression of RhCYCD3, which is involved in control of the cell cycle, significantly increased (2-fold) 24 h after in vitro culture initiation, before returning after 96 h to a value close to that measured at 6 h (Fig. 8D, grey bars). This course was similar to that observed in planta (Supplementary Data Fig. S1B). The addition of 5 mm H2O2 globally reduced the expression of RhCYCD3 and totally prevented the expression peak at 24 h (Fig. 8D, black bars).

Fig. 8.

Impact of H2O2 on transcript accumulation of genes involved in bud outgrowth. Relative transcript accumulation of (A) RhVI (VACUOLAR INVERTASE 1), (B) RhEXP (EXPANSINE), (C) RhPCNA and (D) RhCYCD3 (CYCLINE D3), involved in dormancy, cell expansion, mitosis and cell cycle control, respectively, at different times after in vitro culture set-up (at time T) in the presence (black bars) or absence (grey bars) of 5 mm H2O2. Data are means of n = 3 biological independent replicates ± s.e. Asterisks (*) indicate significant differences when T + 24 and T + 96 h were compared with T + 6 h of the control condition (grey bars). The ¤ symbols indicate significant differences when T + 24 and T + 96 h were compared with T + 6 h of the H2O2-treated condition (black bars). The $ symbols indicate significant differences between the H2O2-treated condition and the control for each sampling time and each transcript. *, ¤, $, P < 0.05; **/¤¤/$$, P < 0.01; ***, $$$, P < 0.001 at confidence range of 95% (Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney non-parametric test).

Fig. 9.

Involvement of H2O2 metabolism in bud outgrowth. This scheme summarizes the involvement of H2O2 in bud outgrowth. The quiescent bud (left) presents a high level of H2O2 along with a low GSH pool that blocks bud outgrowth by repressing cell cycle progression, cell division and expansion. In contrast, the outgrowing bud (right) induced by beheading presents a low level of H2O2 and a high GSH pool due to strong activation of H2O2 scavenging, mainly due to the AsA–GSH cycle and higher GSH biosynthesis. In these conditions, cells enter mitosis and expansion, allowing bud outgrowth. Black lines indicate active pathways and grey lines paused pathways. The sizes of the coloured ellipses indicate metabolite pool sizes.

DISCUSSION

Course of H2O2 content during bud outgrowth

It has previously been pointed out that H2O2 appears to be important in bud outgrowth (Sagi et al., 2004; Pérez et al., 2008). Its implication in this process has been deduced from studies using mutant plants for the generation of ROS, but the exact mechanism of action at bud level was not clearly established. Here we studied variations in H2O2 content in axillary buds occurring during the branching process of actively growing perennial lignified plants, which is a different process from that of winter endodormancy release (Pérez and Noriega, 2018). For this purpose, we developed at the plant and molecular levels an experimental model (Fig. 1A) that allows us to study the axillary bud outgrowth process, both in planta and in vitro, on excised nodes. We determined that the quantity of H2O2 was high in quiescent buds compared with that measured in the stem and continuously decreased in buds after the beheading that initiated the outgrowth process. Additionally, the stability of low levels in the neighbouring stem (Fig. 2A) strongly suggested that this response actually concerns the outgrowth process and not a wounding systemic response to beheading. Furthermore, H2O2 level remained similar to that found in quiescent buds in the presence of the synthetic auxin NAA (Fig. 2B), which mimicked apical dominance. This result is in line with the observations of Wang and Faust (1988), which showed a strong presence of radical compounds in dormant apple tree buds. It is also interesting to note that, during bud outgrowth, H2O2 content became progressively closer to that found in the stem, highlighting the phenotypic transformation from bud to stem (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, we showed that H2O2 treatment kept the bud’s internal level of H2O2 close to that measured in quiescent buds (Fig. 3A), thus strongly preventing bud outgrowth (Fig. 3C), as previously observed in tomato plants (Chen et al., 2016). This inhibition was explained by the total absence of leaf primordium formation and the decline of elongation of preformed organs. This correlation between aerial branching and low H2O2 is in agreement with observations made in tomato plants impaired for RBOH genes, which showed low H2O2 levels in leaves in the high branching phenotype (Sagi et al., 2004; Chen et al., 2016). These results suggested that H2O2 originating from NOX [respiratory burst oxidase homologue (RBOHs)] activity readily controls the ability of buds to enter the outgrowth process. Thus, as H2O2 levels result from the balance between synthesis and degradation, we showed here that H2O2 scavenging is actually also modified in addition to its synthesis (Sagi et al., 2004; Chen et al., 2016) during the outgrowth process to provide a fine tuning of H2O2 towards bud outgrowth.

Scavenging activity drives H2O2 decrease during bud outgrowth

It is well known that the scavenging system is involved in the control of H2O2 level in many plant developmental processes (Das and Roychoudhury, 2014). Since H2O2 decreases during bud outgrowth we were interested to analyse its scavenging. We found a strong activation of ascorbate and glutathione metabolism, particularly through the AsA–GSH cycle, a key process in H2O2 scavenging in plants (Foyer and Noctor, 2011; Supplementary Data Fig. S5). We showed a correlated increase in gene expression and activity levels of cytoplasmic forms of both APX and GR in buds during the outgrowth process (Fig. 4, Supplementary Data Figs S4 and S5). This result suggests that the increase in scavenging during the bud outgrowth process would mainly be due to transcriptional regulation, as previously shown in barley after iron starvation (Bashir et al., 2007). Moreover, it appears from our results that only the cytoplasmic forms of enzymes are involved in the regulation of H2O2 content in buds, as described by Mhamdi et al. (2010a, b) in stress conditions. Bud outgrowth took place in the presence of a high level of glutathione that was correlated with high expression of glutathione synthesis genes (GSH1 and GSH2). Bud endodormancy release may rely on a mechanism sharing similarities with those taking place in bud outgrowth in Rosa. Indeed, Wang et al. (1991), Wang and Faust (1994) and Halaly et al. (2008) showed increased gene expression and enzyme activity of the AsA–GSH pathway during endodormancy release. However, the exact contribution of H2O2 here remains to be clarified since the presence of an initial peak could be interpreted as stimulating bud dormancy release (Pérez and Burgos, 2004). It is striking to note that a quite similar activation of the AsA–GSH cycle was reported in the apparently related yet different bud endodormancy release process (Wang et al., 1991; Wang and Faust, 1994; Halaly et al., 2008). The inhibition of GSH synthesis using its specific inhibitor BSO, inducing a drop in GSH content (Supplementary Data Fig. S7), almost totally prevented rosebush bud outgrowth (Fig. 6). This result constitutes a strong argument confirming the requirement for a high level of GSH in the bud to allow its outgrowth, similar to that observed in the Gentiana branching process (Takahashi et al., 2014). In contrast to many studies highlighting the essential role of catalase in bud outgrowth (Or et al., 2002; Pérez and Lira, 2005; Halaly et al., 2008), our results show that catalase provides a minor contribution (if any) to the bud outgrowth process in rosebush. This point is supported by the fact that catalase is mostly involved in the coarse regulation of redox status because of its lower affinity for H2O2 compared with APX, which consequently finely tunes the H2O2 level (Gill and Tuteja, 2010). This precise control of the H2O2 level appears furthermore well adapted to allowing the accurate regulation of bud outgrowth.

Contribution of bud redox status to cell cycle and growth

Taken together, our results on H2O2 metabolism suggest that the passage of the redox status of the bud from the oxidized to the reduced state during bud outgrowth confirms its role in the branching process, as proposed by Considine and Foyer (2014). Indeed, the relationship between redox status and the modification of markers of gene expression involved in cell division (RhPCNA, RhCYCD3), cell expansion (RhEXP) and sugar availability (RhVI) during axillary bud outgrowth in Rosa (Rabot et al., 2014; Roman et al., 2016, 2017; Barbier et al., 2019a, b) could constitute valuable indications of the contribution of H2O2 to bud outgrowth processes. We established that an H2O2 supply modified the expression of these marker genes in the opposite direction to that observed during bud outgrowth (Figs 1B and 8 and Supplementary Data Fig. S1). The highly oxidized state found naturally in quiescent buds or after H2O2 supply repressed meristem activity. This result has already been found in the paused quiescent centre of roots that contained higher H2O2 levels compared with neighbouring cells. The quiescent centre became less oxidized (lower H2O2 content) at the onset of its activation (Jiang et al., 2003). Similarly, the application of menadione (a superoxide producer, later transformed to H2O2) in cultured cells stopped their division (Reichheld et al., 1999) because of an impaired G1–S transition of the cell cycle, related to the inhibition of cyclin genes. We also showed that H2O2-treated buds displayed a marked reduction of cyclin gene expression (Fig. 8D). Glutathione (GSH) and ascorbate (AsA) pools and their redox states have proven to constitute excellent indicators of cell redox status in plants (Foyer and Noctor, 2011; Considine and Foyer, 2014) and have also been proposed to regulate cell division and cell cycle progression (Reichheld et al., 1999; Potters et al., 2000, 2004, 2010; Diaz Vivancos et al., 2010; Foyer and Noctor, 2011). Here, increases in total GSH and GSH/GSSG ratio in buds during their outgrowth are concordant with the induction of cyclin that is essential for the cell cycle to resume to S phase (Diaz-Vivancos et al., 2015) and could constitute an important component of dormancy release (Kranner et al., 2006). However, as noted by Schnaubelt et al. (2015), subsequent de novo synthesis of GSH is required for the induction of the cell cycle in Arabidopsis, as also found in Rosa in the present work, since BSO application resulted in total repression of bud outgrowth (Fig. 6A). Furthermore, cell expansion, reflected through the expression of RhEXP, is also inhibited by H2O2 (Fig. 8B) and contributes to the decrease in axis elongation in H2O2-treated buds (Fig. 3D). The negative effect of H2O2 treatment on plant growth has already been described in shoots and roots (Wang et al., 2006; Ivanchenko et al., 2013), and could also be linked to expansin repression in Arabidopsis (Wang et al., 2006). Here we showed that vacuolar invertase was downregulated in the presence of H2O2 (Fig. 8A), preventing the supply of free hexose in the cytosol and thereafter reducing elongation of the new axis.

Figure 9 summarizes the central role played by internal H2O2 metabolism in cellular processes in the fate of the bud. In the quiescent state, a high level of H2O2, along with a low pool of GSH, blocks cell expansion and mitosis, both acting to repress bud outgrowth. In contrast, after apical dominance release a large increase in scavenging actors (AsA–GSH cycle and GSH synthesis) causes a strong reduction in H2O2 level and a large increase in the GSH pool, both of these acting to restart the cell cycle and release the inhibition of cell expansion and mitosis, leading to bud outgrowth.

Conclusions

Our data suggest that H2O2 scavenging, through the AsA–GSH cycle, appears to be an important component of the bud outgrowth mechanism, confirming a major role for H2O2 in bud outgrowth control, as previously suggested. The contribution of H2O2 to this process brings new insights to the understanding of the mechanism surrounding the bud outgrowth process. Here we showed that the level of H2O2 actually drives different factors towards bud quiescence (high H2O2) or bud outgrowth (low H2O2) as a function of the major role of the H2O2-scavenging activity of the AsA–GSH and glutathione synthesis pathways, while catalase appears not to be implicated. The potential targets for this reduction in H2O2 are likely to include phytohormones, as many of them have been proved to critically regulate bud outgrowth (Rameau et al., 2015) and the auxin/cytokinin ratio was decreased in mutant plants deficient in H2O2 synthesis that displayed a high branching phenotype (Chen et al., 2016). Thus, investigating the crosstalk between H2O2 and phytohormones would make a valuable contribution to a deeper understanding of the bud outgrowth mechanism.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available online at https://academic.oup.com/aob and consist of the following. Figure S1: validation of the H2O2 determination technique by luminescence in rosebush tissues. Figure S2: course of transcript accumulation of different bud outgrowth marker genes. Figure S3: effect of NAA (auxin homologue) in the bud outgrowth process. Figure S4: phylogenetic trees of mRNA sequence homology between Rosa sp. and Arabidopsis thaliana. Figure S5: schematic representation of the ascorbate–glutathione cycle (Foyer–Halliwell–Asada cycle). Figure S6: Pearson correlation between relative accumulation of RhGR1 transcripts and total GR activity during bud outgrowth. Figure S7: effect of BSO on total glutathione content in buds. Table S1: list of primer sequences already published in previous work in rosebush. Table S2: list of primer sequences of unpublished genes in rosebush; genes were named by homology with Arabidopsis thaliana genes.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to Professor Eric Davies for manuscript English correction and English correction and Pascale Satour for her help in protein extract purification. We are most grateful to the PHENOTIC core facility (Angers, France) for its technical support. A.P., A.V., J.L. and V.G. conceived and designed the study. A.P. and A.L. performed the experiments. A.P. and F.M. analysed the results. A.P, A.V, V.G. and J.L. drafted the manuscript. A.V., J.L., V.G. and F.M. proofread the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the manuscript. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

FUNDING

This research was conducted within the framework of the regional program ‘Objectif Végétal, Research, Education and Innovation in Pays de la Loire’, supported by the French Pays de la Loire region, Angers Loire Métropole and the European Regional Development Fund.

LITERATURE CITED

- Aguilar-Martínez JA, Poza-Carrión C, Cubas P. 2007. Arabidopsis BRANCHED1 acts as an integrator of branching signals within axillary buds. Plant Cell 19: 458–472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbier FF, Lunn JE, Beveridge CA. 2015a Ready, steady, go! A sugar hit starts the race to shoot branching. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 25: 39–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbier F, Péron T, Lecerf M, et al. 2015. b Sucrose is an early modulator of the key hormonal mechanisms controlling bud outgrowth in Rosa hybrida. Journal of Experimental Botany 66: 2569–2582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbier F, Chabikwa TG, Ahsan MU, et al. 2019. a A phenol/chloroform-free method to extract nucleic acids from recalcitrant, woody tropical species for gene expression and sequencing. Plant Methods 15: 9–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbier FF, Dun EA, Kerr SC, Chabikwa TG, Beveridge CA. 2019b An update on the signals controlling shoot branching. Trends in Plant Science 24: 220–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes J, Zheng Y, Lyons T. 2002. Plant resistance to ozone: the role of ascorbate. In: Omasa K, Saji H, Youssefian S, Kondo N. eds Air pollution and plant biotechnology. Tokyo, Japan: Springer, 235–252. doi: 10.1007/978-4-431-68388-9_12 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bashir K, Nagasaka S, Itai RN, et al. 2007. Expression and enzyme activity of glutathione reductase is upregulated by Fe-deficiency in graminaceous plants. Plant Molecular Biology 65: 277–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beveridge CA, Symons GM, Turnbull CG. 2000. Auxin inhibition of decapitation-induced branching is dependent on graft-transmissible signals regulated by genes Rms1 and Rms2. Plant Physiology 123: 689–698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beveridge CA, Weller JL, Singer SR, Hofer JM. 2003. Axillary meristem development. Budding relationships between networks controlling flowering, branching, and photoperiod responsiveness. Plant Physiology 131: 927–934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao WS, Foley ME, Horvath DP, Anderson JV. 2007. Signals regulating dormancy in vegetative buds. International Journal of Plant Developmental Biology 1: 49–56. [Google Scholar]

- Chen XJ, Xia XJ, Guo X, et al. 2016. Apoplastic H2O2 plays a critical role in axillary bud outgrowth by altering auxin and cytokinin homeostasis in tomato plants. New Phytologist 211: 1266–1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Considine MJ, Foyer CH. 2014. Redox regulation of plant development. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling 21: 1305–1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke JE, Eriksson ME, Junttila O. 2012. The dynamic nature of bud dormancy in trees: environmental control and molecular mechanisms. Plant, Cell & Environment 35: 1707–1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dal Santo S, Fasoli M, Cavallini E, Tornielli GB, Pezzotti M, Zenoni S. 2011. PhEXPA1, a Petunia hybrida expansin, is involved in cell wall metabolism and in plant architecture specification. Plant Signaling & Behavior 6: 2031–2034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das K, Roychoudhury A. 2014. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) and response of antioxidants as ROS-scavengers during environmental stress in plants. Frontiers in Environmental Science 2: 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Devitt ML, Stafstrom JP. 1995. Cell cycle regulation during growth-dormancy cycles in pea axillary buds. Plant Molecular Biology 29: 255–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Vivancos P, De Simone A, Kiddle G, Foyer CH. 2015. Glutathione – linking cell proliferation to oxidative stress. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 89: 1154–1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz Vivancos P, Wolff T, Markovic J, Pallardó FV, Foyer CH. 2010. A nuclear glutathione cycle within the cell cycle. Biochemical Journal 431: 169–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domagalska MA, Leyser O. 2011. Signal integration in the control of shoot branching. Nature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biology 12: 211–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dun EA, Brewer PB, Beveridge CA. 2009. Strigolactones: discovery of the elusive shoot branching hormone. Trends in Plant Science 14: 364–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evers JB, van der Krol AR, Vos J, Struik PC. 2011. Understanding shoot branching by modelling form and function. Trends in Plant Science 16: 464–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foyer CH, Noctor G. 2011. Ascorbate and glutathione: the heart of the redox hub. Plant Physiology 155: 2–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furet PM, Lothier J, Demotes-Mainard S, et al. 2014. Light and nitrogen nutrition regulate apical control in Rosa hybrida L. Journal of Plant Physiology 171: 7–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill RA, Zang L, Ali B, et al. 2015. Chromium-induced physio-chemical and ultrastructural changes in four cultivars of Brassica napus L. Chemosphere 120: 154–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill SS, Tuteja N. 2010. Reactive oxygen species and antioxidant machinery in abiotic stress tolerance in crop plants. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 48: 909–930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girault T, Bergougnoux V, Combes D, Viemont JD, Leduc N. 2008. Light controls shoot meristem organogenic activity and leaf primordia growth during bud burst in Rosa sp. Plant, Cell & Environment 31: 1534–1544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Grandío E, Poza-Carrión C, Sorzano COS, Cubas P. 2013. BRANCHED1 promotes axillary bud dormancy in response to shade in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 25: 834–850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halaly T, Pang X, Batikoff T, et al. 2008. Similar mechanisms might be triggered by alternative external stimuli that induce dormancy release in grape buds. Planta 228: 79–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han X, Lu M, Chen Y, Zhan Z, Cui Q, Wang Y. 2012. Selection of reliable reference genes for gene expression studies using real-time PCR in tung tree during seed development. PLoS ONE 7: 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henmi K, Yanagida M, Ogawa K. 2007. Roles of reactive oxygen species and glutathione in plant development. International Journal of Plant Developmental Biology 1: 185–193. [Google Scholar]

- Henry C, Rabot A, Laloi M, et al. 2011. Regulation of RhSUC2, a sucrose transporter, is correlated with the light control of bud burst in Rosa sp. Plant, Cell & Environment 34: 1776–1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibrand Saint-Oyant L, Ruttink T, Hamama L, et al. 2018. A high-quality genome sequence of Rosa chinensis to elucidate ornamental traits. Nature Plants 4: 473–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath DP, Anderson JV, Chao WS, Foley ME. 2003. Knowing when to grow: signals regulating bud dormancy. Trends in Plant Science 8: 534–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huché-Thélier L, Boumaza R, Demotes-Mainard S, et al. 2011. Nitrogen deficiency increases basal branching and modifies visual quality of the rose bushes. Scientia Horticulturae 130: 325–334. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanchenko MG, Den Os D, Monshausen GB, Dubrovsky JG, Bednářová A, Krishnan N. 2013. Auxin increases the hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) concentration in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) root tips while inhibiting root growth. Annals of Botany 112: 1107–1116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang K, Meng YL, Feldman LJ. 2003. Quiescent center formation in maize roots is associated with an auxin-regulated oxidizing environment. Development 130: 1429–1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, Huang B. 2001. Effects of calcium on antioxidant activities and water relations associated with heat tolerance in two cool-season grasses. Journal of Experimental Botany 52: 341–349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kranner I, Birtić S, Anderson KM, Pritchard HW. 2006. Glutathione half-cell reduction potential: a universal stress marker and modulator of programmed cell death? Free Radical Biology & Medicine 40: 2155–2165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Stecher G, Li M, Knyaz C, Tamura K. 2018. MEGA X: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Molecular Biology and Evolution 35: 1547–1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G, Tan M, Cheng F, et al. 2018. Molecular role of cytokinin in bud activation and outgrowth in apple branching based on transcriptomic analysis. Plant Molecular Biology 98: 261–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li-Marchetti C, Le Bras C, Relion D, et al. 2015. Genotypic differences in architectural and physiological responses to water restriction in rose bush. Frontiers in Plant Science 6: 355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Macarisin D, Wisniewski M, et al. 2013. Production of hydrogen peroxide and expression of ROS-generating genes in peach flower petals in response to host and non-host fungal pathogens. Plant Pathology 62: 820–828. [Google Scholar]

- Lu S, Song J, Campbell-Palmer L. 2009. A modified chemiluminescence method for hydrogen peroxide determination in apple fruit tissues. Scientia Horticulturae 120: 336–341. [Google Scholar]

- Mason MG, Ross JJ, Babst BA, Wienclaw BN, Beveridge CA. 2014. Sugar demand, not auxin, is the initial regulator of apical dominance. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA 111: 6092–6097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathiason K, He D, Grimplet J, et al. 2009. Transcript profiling in Vitis riparia during chilling requirement fulfillment reveals coordination of gene expression patterns with optimized bud break. Functional & Integrative Genomics 9: 81–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meitha K, Agudelo-Romero P, Signorelli S, et al. 2018. Developmental control of hypoxia during bud burst in grapevine. Plant, Cell & Environment 41: 1154–1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mhamdi A, Van Breusegem F. 2018. Reactive oxygen species in plant development. Development 145: dev164376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mhamdi A, Hager J, Chaouch S, et al. 2010. a Arabidopsis GLUTATHIONE REDUCTASE1 plays a crucial role in leaf responses to intracellular hydrogen peroxide and in ensuring appropriate gene expression through both salicylic acid and jasmonic acid signaling pathways. Plant Physiology 153: 1144–1160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mhamdi A, Queval G, Chaouch S, Vanderauwera S, Van Breusegem F, Noctor G. 2010b Catalase function in plants: a focus on Arabidopsis mutants as stress-mimic models. Journal of Experimental Botany 61: 4197–4220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittler R. 2002. Oxidative stress, antioxidants and stress tolerance. Trends in Plant Science 7: 405–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittler R. 2017. ROS are good. Trends in Plant Science 22: 11–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Moigne MA, Guérin V, Furet PM, et al. 2018. Asparagine and sugars are both required to sustain secondary axis elongation after bud outgrowth in Rosa hybrida. Journal of Plant Physiology 222: 17–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller D, Leyser O. 2011. Auxin, cytokinin and the control of shoot branching. Annals of Botany 107: 1203–1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakano Y, Asada K. 1981. Hydrogen peroxide is scavenged by ascorbate-specific peroxidase in spinach chloroplasts. Plant and Cell Physiology 22: 867–880. [Google Scholar]

- Noctor G, Mhamdi A, Foyer CH. 2016. Oxidative stress and antioxidative systems: recipes for successful data collection and interpretation. Plant, Cell & Environment 39: 1140–1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ophir R, Pang X, Halaly T, et al. 2009. Gene-expression profiling of grape bud response to two alternative dormancy-release stimuli expose possible links between impaired mitochondrial activity, hypoxia, ethylene-ABA interplay and cell enlargement. Plant Molecular Biology 71: 403–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Or E, Vilozny I, Fennell A, Eyal Y, Ogrodovitch A. 2002. Dormancy in grape buds: isolation and characterization of catalase cDNA and analysis of its expression following chemical induction of bud dormancy release. Plant Science 162: 121–130. [Google Scholar]

- Oracz K, El-Maarouf-Bouteau H, Kranner I, Bogatek R, Corbineau F, Bailly C. 2009. The mechanisms involved in seed dormancy alleviation by hydrogen cyanide unravel the role of reactive oxygen species as key factors of cellular signaling during germination. Plant Physiology 150: 494–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez FJ, Burgos B. 2004. Alterations in the pattern of peroxidase isoenzymes and transient increases in its activity and in H2O2 levels take place during the dormancy cycle of grapevine buds: the effect of hydrogen cyanamide. Plant Growth Regulation 43: 213–220. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez FJ, Lira W. 2005. Possible role of catalase in post-dormancy bud break in grapevines. Journal of Plant Physiology 162: 301–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez FJ, Noriega X. 2018. Sprouting of paradormant and endodormant grapevine buds under conditions of forced growth: similarities and differences. Planta 248: 837–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez FJ, Vergara R, Rubio S. 2008. H2O2 is involved in the dormancy-breaking effect of hydrogen cyanamide in grapevine buds. Plant Growth Regulation 55: 149–155. [Google Scholar]

- Pfaffl MW. 2001. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT–PCR. Nucleic Acids Research 29: 16–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potters G, Horemans N, Caubergs RJ, Asard H. 2000. Ascorbate and dehydroascorbate influence cell cycle progression in a tobacco cell suspension. Plant Physiology 124: 17–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potters G, Horemans N, Bellone S, et al. 2004. Dehydroascorbate influences the plant cell cycle through a glutathione-independent reduction mechanism. Plant Physiology 134: 1479–1487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potters G, Horemans N, Jansen MAK. 2010. The cellular redox state in plant stress biology – a charging concept. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 48: 292–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabot A, Portemer V, Péron T, et al. 2014. Interplay of sugar, light and gibberellins in expression of Rosa hybrida vacuolar invertase 1 regulation. Plant & Cell Physiology 55: 1734–1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rameau C, Bertheloot J, Leduc N, Andrieu B, Foucher F, Sakr S. 2015. Multiple pathways regulate shoot branching. Frontiers in Plant Science 5: 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichheld J, Vernoux T, Lardon F, Van Montagu M , Inze D, Wilrijk B. 1999. Specific checkpoints regulate plant cell cycle progression in response to oxidative stress. Plant Journal 17: 647–656. [Google Scholar]

- Roman H, Girault T, Barbier F, et al. 2016. Cytokinins are initial targets of light in the control of bud outgrowth. Plant Physiology 172: 489–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roman H, Girault T, Le Gourrierec J, Leduc N. 2017. In silico analysis of 3 expansin gene promoters reveals 2 hubs controlling light and cytokinins response during bud outgrowth. Plant Signaling & Behavior 12: e1284725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. 2017. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; https://www.R-project.org/. [Google Scholar]

- Sagi M, Davydov O, Orazova S, et al. 2004. Plant respiratory burst oxidase homologs impinge on wound responsiveness and development in Lycopersicon esculentum. Plant Cell 16: 616–628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnaubelt D, Queval G, Dong Y, et al. 2015. Low glutathione regulates gene expression and the redox potentials of the nucleus and cytosol in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant, Cell & Environment 38: 266–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu S, Mori H. 1998a Changes in protein interactions of cell cycle-related genes during the dormancy-to-growth transition in pea axillary buds. Plant & Cell Physiology 39: 1073–1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu S, Mori H. 1998b Analysis of cycles of dormancy and growth in pea axillary buds based on mRNA accumulation patterns of cell cycle-related genes. Plant & Cell Physiology 39: 255–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strzalka W, Ziemienowicz A. 2011. Proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA): a key factor in DNA replication and cell cycle regulation. Annals of Botany 107: 1127–1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudawan B, Chang CS, Chao HF, Ku MS, Yen YF. 2016. Hydrogen cyanamide breaks grapevine bud dormancy in the summer through transient activation of gene expression and accumulation of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. BMC Plant Biology 16: 202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi H, Imamura T, Konno N, et al. 2014. The gentio-oligosaccharide gentiobiose functions in the modulation of bud dormancy in the herbaceous perennial Gentiana. Plant Cell 26: 3949–3963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Nei M. 1993. Estimation of the number of nucleotide substitutions in the control region of mitochondrial DNA in humans and chimpanzees. Molecular Biology and Evolution 10: 512–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vergara R, Parada F, Rubio S, Pérez FJ. 2012. Hypoxia induces H2O2 production and activates antioxidant defence system in grapevine buds through mediation of H2O2 and ethylene. Journal of Experimental Botany 63: 4123–4131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M, Ogé L, Voisine L, et al. 2019. Posttranscriptional regulation of RhBRC1 (Rosa hybrida BRANCHED1) in response to sugars is mediated via its own 3′ untranslated region, with a potential role of RhPUF4 (Pumilio RNA-Binding Protein Family). International Journal of Molecular Sciences 20: 3808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang PC, Du YY, An GY, Zhou Y, Miao C, Song CP. 2006. Analysis of global expression profiles of Arabidopsis genes under abscisic acid and H2O2 applications. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology 48: 62–74. [Google Scholar]

- Wang SY, Faust M. 1988. Metabolic activities during dormancy and blooming of deciduous fruit trees. Israel Journal of Botany 37: 227–243. [Google Scholar]

- Wang SY, Faust M. 1994. Changes in the antioxidant system associated with budbreak in ‘Anna’ apple (Malus domestica Borkh.) buds. Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science 119: 735–741. [Google Scholar]

- Wang SY, Jiao HJ, Faust M. 1991. Changes in ascorbate, glutathione, and related enzyme activities during thidiazuron‐induced bud break of apple. Physiologia Plantarum 82: 231–236. [Google Scholar]

- Zang L, Morère-Le Paven M-C, Clochard T, et al. 2020. Nitrate inhibits primary root growth by reducing accumulation of reactive oxygen species in the root tip in Medicago truncatula. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 146: 363–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.