EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The 2019-2020 Student Affairs Standing Committee addressed charges related to professional identity formation (PIF) in order to set direction and propose action steps consistent with Priority #3.4 of the AACP Strategic Plan, which states “Academic-practice partnerships and pharmacist-involved practice models that lead to the progress of Interprofessional Practice (IPP) are evident and promoted at all colleges and schools of pharmacy.” To this end, the committee was charged to 1) outline key elements of PIF, 2) explore the relationship between formal curricular learning activities and co- or extra-curricular activities in supporting PIF, 3) determine the degree to which there is evidence that strong PIF is embedded in student pharmacists’ educational experience, and 4) define strategies and draft an action plan for AACP’s role in advancing efforts of schools to establish strong PIF in pharmacy graduates. This report describes work of the committee in exploring PIF and provides resources and background information relative to the charges. The committee offers several suggestions and recommendations for both immediate and long-term action by AACP and members to achieve goals related to integrating PIF into pharmacy education. The committee proposes a policy statement relative to the committee charges. Furthermore, the report calls upon the profession to develop a unified identity and incorporate support for PIF into pharmacy education, training, and practice.

Keywords: professional identity formation, communities of practice, professionalism, socialization, practice transformation

INTRODUCTION AND COMMITTEE CHARGES

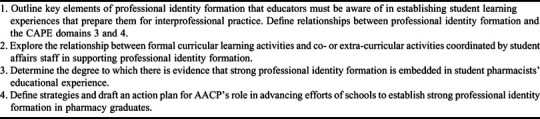

The Student Affairs Standing Committee, in accordance with the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy (AACP) Bylaws, received charges from the Association President (Table 1).1 President Todd Sorensen focused his presidential year on transforming practice models. He articulated that while it is a time of tremendous opportunity, there is frustration and despair among pharmacists who frequently feel undervalued and question the future of the profession. Therefore, all standing committees were charged with activities to support practice transformation according to the bold aim “by 2025, 50 percent of primary care physicians in the U.S. will have a formal relationship with a pharmacist.”2 In particular, President Sorensen charged the 2019-2020 Student Affairs Standing Committee to examine professional identity formation (PIF) in order to set direction and propose actions steps consistent with Priority #3, which states, “AACP will lead and partner with members and other health professions in the transformation of innovative health professions education and practice.”3 The transformation of the pharmacy practice model from one that is product-based to one that is service-based hinges on a change in the profession’s identity. The identity change needed goes beyond acquiring knowledge (“thinking”) and displaying professionalism (“acting”) to include the pharmacist's perceptions of self (“feeling”). Professional identity formation (PIF) is a process of internalization of a profession’s core values and beliefs and is representative of all three domains: thinking, feeling, and acting. The committee contends that PIF will better serve the profession of pharmacy during a time of practice transformation than our current and usual approach to “teaching professionalism.”

Table 1.

Charges of the 2019-2020 AACP Student Affairs Standing Committee

To address the charges, committee members searched existing health professions education literature, sought advice from external experts in the field, and drafted an extensive narrative relative to charges using relevant literature. The committee drafted an action plan with specific goals supporting the charges and submitted it in December 2019. In January 2020, the committee met in person to review and fine-tune the draft action plan. At this meeting, members met with other AACP Standing Committees and received further guidance from President Sorensen. Following this meeting, the committee further detailed the action plan identifying the goals and steps to be completed by the current committee and those that were beyond the scope and purview of the 2019-2020 committee.

Charge 1: What Is Professional Identity Formation?

The terms professionalism and professional identity are often mistakenly used interchangeably. Developing student professionalism has been part of pharmacy education for decades, the perceived importance of which has grown with the advanced role of the pharmacist as an equal member of the healthcare team. The intent of developing professionalism in pharmacy students is to lay the foundation for the professional behaviors and displayed attitudes expected of a practicing pharmacist. In concert with the technical knowledge and skills required of a pharmacist, professionalism allows for ethical, patient-centered care and contributes to the public trust. While professionalism is often defined by behavior that is outwardly visible, professional identity is represented by an internal adoption of the norms of a profession such that one will “think, feel, and act” like a member of a community.4

Identity can be described as the way in which one sees themselves and is seen by others.5 As educators consider the prospect of influencing identity formation within our learners, a common concern is the apparent lack of a universally accepted6 and singular identity for the profession of pharmacy.7 Elvey8 and Kellar7 describe multiple identities described by practicing pharmacists (eg, “apothecary,” “medicine supplier,” “merchandiser,” “expert advisor,” etc.). If the profession is to transition as healthcare providers, we face challenges. As the history of our profession suggests, these polymorphic identity constructs have accumulated rather than shifted over time.7 The multiple seemingly incongruent or divergent identities described by practicing pharmacists may have an unintentionally negative impact on the formation of a uniform healthcare provider identity, thus hindering pharmacists’ successful practice transformation.7,8 If there is no agreement on identity within our profession, what are educators educating toward? Yet, while agreement is important, an educator’s work cannot wait while the profession resolves its future. Clearly, the PIF work at the collective professional level (What is our identity as a profession?) cannot be forgotten as educators seek to influence at the individual student level (How can we influence adoption of professional pharmacist identity by early learners?).

Some might argue that the current focus in the United States on the Pharmacist’s Patient Care Process (PPCP) will move the profession toward a unified identity. The PPCP has generated consensus on a specific, patient-centered approach to collaboration with other providers in optimizing medication outcomes.9 Additional work within the realm of the PPCP has included developing clarity around a philosophy of practice10 and establishing the operational definitions necessary for fidelity in the delivery of a well-defined patient care service.11 However, the intent of the PPCP only addresses what it means to “think” like a pharmacist and does not define what it means to “feel and act” like a pharmacist. Additional work is required to ensure each pharmacist and trainee internalizes a professional identity that supports and advances our community of practice.

Medical schools have also historically prioritized student professionalism as part of a competency-based educational approach, with professional behaviors viewed as one of many competencies to be taught and assessed. However, concerns have arisen that an emphasis on competency assessment (ie, professionalism skills checklists) is poorly aligned with a need to train practitioners who legitimately internalize the shared attitudes and beliefs of the medical profession.12 As a result, schools of medicine have been called to redirect their efforts away from teaching students what a professional does and toward formation of a professional identity. In fact, in discussing PIF in medical education, Cruess and colleagues have recognized the need for educators to envision a professional identity for the future that: 1) acknowledges core elements that are foundational and timeless, 2) accommodates the alterations that must be made to address new realities.13

Within pharmacy education, the transition to PIF could be simplified by building upon existing constructs and approaches. Most terminology and guidance within pharmacy education, training, and practice currently focuses on professional characteristics, traits, and roles, without explicit discussion of PIF.14-17 For example, within the CAPE Outcomes and ACPE Standards 2016, concepts related to pharmacist professional identity are present in Domains 3 and 4, (eg, self-awareness and professionalism), but “professional identity formation” is not directly discussed.14,18 The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists seems to evoke the beginnings of a professional identity when it defines a PharmD graduate as “a novice who possesses fundamental knowledge, skills, attitudes, and abilities to provide medication-related patient care, but has limited practice experience,”19 but explicit reference to “professional identity formation” is not made. Guidance documents from pharmacy professional organizations emphasize the roles and responsibilities of the pharmacist, but do not directly discuss PIF.9,15-17,20

Just as the PPCP provides a uniform approach to patient care across all practice areas, a common language to evoke PIF should be shared by all involved in educating, training, and managing current and developing pharmacists. There is a need to evolve our current focus on teaching professionalism to a focus on actively supporting PIF. As the profession advances to solidify its role in healthcare, pharmacy educators and the profession must adopt common language within guidance documents and support PIF in pharmacy students, postgraduate trainees, and pharmacists.

Recommendation 1

AACP should advocate for the adoption of PIF in educational and professional goal statements in guidance documents to assist in creating a culture of commitment to professional identity formation.

Recommendation 2

AACP should initiate conversations within the profession of pharmacy to: 1) develop a unified identity and 2) incorporate support for PIF into pharmacy education, training, and practice.

Proposed Policy Statement

AACP encourages colleges and schools of pharmacy to advance education that is aimed at the intentional formation of professional identity (ie, thinking, feeling and acting like a pharmacist) and developed and implemented in cooperation with professional pharmacy organizations within the broader pharmacy profession.

Charge 2: Education That Supports Professional Identity Formation

The process of professional identity formation requires engaging in social interactions within a professional community and then reflecting and acting on feedback from community members as one’s roles and responsibilities evolve towards competence. The perspectives of others influence a student pharmacist’s view of themselves and their professional responsibilities and identity during the socialization process.21,22 The PIF process is thus heavily influenced by communities of practice, defined as “a persistent, sustaining social network of individuals who share and develop an overlapping knowledge base, set of beliefs, values, history, and experiences focused on a common practice.”23 Identity formation is an iterative process that involves the individual, the communities with whom the individual interacts, and the feedback the individual receives based on those interactions. Herein, learners transition from passive to active participation in the community, acquiring aspects of identity from members of the community.22

Students describe difficulty using their classroom experiences as part of their PIF.24 In a study by Noble and colleagues, students report few opportunities to practice the roles of pharmacists and, therefore, to see themselves as student pharmacists rather than simply students. In addition, traditional teaching approaches were infrequently thought of by students as authentic experiences through which they could connect to the pharmacy community of practice. This reduced opportunities for students to observe the behaviors, attitudes, and actions they attribute to the profession, thus limiting the classroom’s perceived impact on PIF.

Experiential education and co-curriculum can play an important role in professional socialization, and therefore in PIF, by providing opportunities for students to directly engage in communities of pharmacy practice. Learners are influenced intraprofessionally within a community of practice.22,24 However, there can also be dual identity formation as a healthcare professional through interactions with other professionals.22,25 Pharmacy education has stressed enhanced co-curricular participation, early experiential education and increased interprofessional education (IPE) and these existing frameworks can be leveraged as important venues for student pharmacists’ PIF.14,25

A key first step to engaging pharmacy educators, namely faculty and preceptors, in the PIF process is to provide professional development that orients them to the process, terminology, and pedagogies involved. Given that PIF is not commonly discussed among pharmacy educators, promoting faculty and preceptor understanding could enhance the implementation of successful activities throughout the curriculum. Educator development should include the definition of professional identity and theories behind the educational purpose of PIF, such as socialization and communities of practice.6 This primer can set the stage for educators to understand their importance as role models to students, which is a vital component of PIF.24 To date there is little definitive guidance for faculty in supporting students’ PIF, which is a complex, dynamic process. Undoubtedly, the identification of meaningful, intentional experiences both within and outside of the classroom will be an important part of an educator’s role in developing professional identity in student pharmacists. Several models of personal identity development and formation have been explored and applied to pharmacy students, including both Self Determination Theory and Self-Authorship Theory, which are introduced briefly below.

Mylrea and colleagues suggest the use of Self Determination Theory (SDT) when developing academic approaches to developing professional identity.26 SDT proposes that individuals who are making progress toward developing a specific identity will be responding to either extrinsic or intrinsic motivation in decision-making and action. The transition from extrinsic to intrinsic motivation marks the development of an identity- thinking, feeling and acting like a member of a community. The use of SDT theory to create curricula that develop the intrinsic motivation characteristic of professional identity involves a focus on competence, relatedness and autonomy, with relatedness and autonomy being important additions to pharmacy education’s traditional focus on competence.

Johnson and Chauvin developed a framework linking Marcia Baxter-Magolda’s Self-Authorship Theory to PIF. Similar to SDT, Self-Authorship Theory describes an individual's journey to intrinsic motivation and self-reliance as a direct result of “provocative experiences.”27 Self-Authorship Theory additionally proposes the Learning Partnerships Model as a pedagogical framework for the intentional design of such provocative learning experiences that can directly trigger progression towards identity development.28 More attention to the intentional design of potentially provocative experiences is needed in pharmacy education. These two theories and models of identity formation (Self Determination and Self Authorship) can be used by educators to develop authentic learning experiences that will promote PIF. Additional research in the implementation, effectiveness, and applicability of these models to pharmacy education is warranted.

Interactions with mentors and role models also provide students with opportunities to enhance their understanding of appropriate professional behaviors across various settings in which exchanges are occurring (eg, medical rounds, active learning activities, patient counseling, etc.).29 Performance feedback and role modeling by pharmacy educators can validate a student’s existing identity and help shape continued development. Institutions can use a proactive approach to role modeling to assist educators in understanding the influence and supportive function that role-modeling plays in PIF and to enhance the relational component of identity formation.

The framework an institution adopts for support of student PIF should include clear definitions and learning objectives linked to specific educational strategies that extend throughout the curriculum.6,30 Establishing a longitudinal, multi-pronged approach in the curriculum is essential, given that PIF is a dynamic, continuous process. The PIF process should ideally start as early as the pre-pharmacy period and go through a student’s experiential education.13 Incorporation of PIF requires a team approach and should involve all individuals who can influence identity formation of the learner across various settings including, but not limited to: administrators, practicing pharmacists, and faculty.22

Recommendation 3

AACP should provide faculty development resources and programming on professional identity formation.

Recommendation 4

AACP should invite an expert on professional identity formation to serve as speaker at an AACP conference and/or a teacher’s seminar focused on the topic.

Suggestion 1

Colleges and schools should provide professional development for faculty and preceptors (ie, pharmacy educators) on professional identity formation.

Suggestion 2

Colleges and schools should develop intentional approaches and specific educational strategies to support socialization, role modeling, and integration of student pharmacists within the pharmacy community of practice that is longitudinal, multi-pronged and begin as early as pre-pharmacy coursework.

Suggestion 3

Colleges and schools incorporate authentic experiences within their curriculum, co-curriculum, and extra-curriculum that reflect current practice, but also support practice transformation.

Charge 3: Evidence and Assessment Of PIF Within Pharmacy Education

As suggested by Noble, McKauge, Clavarino, PIF in pharmacy education is an area that needs to be more fully explored.6 As directed by our charge, we did not find that there was “evidence that strong professional identity formation is embedded in student pharmacists’ educational experience.” In particular, further exploration into PIF assessment is needed to firmly support strong approaches to pharmacy student PIF. There are published reports of programs incorporating curricular and co-curricular elements targeting professionalism and PIF (references included in Noble 2019), and more work is likely occurring.6 Assessment of professionalism can be less challenging than assessing PIF, due to the latter’s internal and transitional nature. Assessment of professionalism often relies on observations of the presence or frequency of certain actions and several studies in pharmacy education have designed instruments or constructs to evaluate professionalism.31-33

Because “feeling like a pharmacist” is not an observable characteristic, it is more difficult to assess. Instead, assessing PIF requires evaluating students’ internal beliefs and the rationale for those beliefs, which evolve during a student’s education. As articulated in the committee’s response to Charge 1 above, assessment of PIF is also complicated by the lack of an agreed-upon definition of pharmacists’ professional identity. The need for a definition, coupled with the need to align with an ever-evolving practice of pharmacy, means that the challenges of measuring PIF relative to a particular professional standard will endure for the foreseeable future. It is understandable that educators will look for a single measure that provides a definitive, summative, “pass/don’t pass,” reliable and valid assessment of any variable targeted by our educational systems. However, this type of measurement may not be possible for PIF.

Assessment strategies can help inform pharmacy educators about PIF in students. Understanding a student’s or cohort’s relative stage or phase of identity formation allows us to meet students where they are and devise programming to support and assist in this developmental process. Since identity is formed and revised over time, programs for guiding pharmacy students’ PIF will need to be longitudinal. Likewise, assessing PIF at one point in time, rather than longitudinally over time, limits the validity of the evaluation, and thus the ability to draw accurate conclusions about the scope of someone’s identity development. Therefore, multiple points of assessment are desirable.

The existence of multiple identities and the presence of multiple theories complicates the ability to construct a single assessment strategy capable of capturing both the depth and breadth of PIF. There are many examples of applicable identity theories for qualitative evaluation of PIF in the health professions.26,28,34-36 Qualitative methodologies evaluating PIF offer conceptual language for exploring the complexity of identity formation through interviews or written narratives from students. Employing qualitative strategies aids in the ability to understand the “why” behind identity formation. Most quantitative instruments assessing PIF are questionnaires, asking students to indicate agreement on a Likert-type scale and are largely site-specific.6,26,37,38 As a result, evidence from any one questionnaire would not be representative of the breadth of pharmacy learners across the US or the globe.6 Although instrument limitations are apparent, quantitative strategies can be helpful in evaluating the impact of an activity or experience designed to promote PIF (eg, mentoring, experiential activities, role play).39

Recommendation 5

AACP should continue to facilitate inquiry and dissemination of strategies related to PIF assessment.

Suggestion 4

Colleges and schools should pursue scholarly questions in support of the assessment of PIF.

Suggestion 5

Colleges and schools should share their initiatives with evaluative evidence related to PIF.

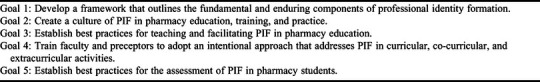

Charge 4: Action Plan for AACP

The Student Affairs Standing Committee has worked to heighten the pharmacy education community’s interest in and commitment to PIF. AACP webinars and conference themes on PIF have surfaced secondary to the actions of the committee. At the AACP Interim Meeting 2020, PIF-focused microsessions were presented. In addition, AACP introduced a theme on PIF for the 2020 Annual Meeting School poster session and hosted a spring 2020 webinar on PIF as part of its Practice Transformation series. Additionally, as part of the American Pharmacists Association 2020 Annual Meeting, a panel discussion on PIF was conducted as a virtual continuing education session. While progress has been made, additional action by future committees and organizations toward goals were identified by the 2019-2020 committee (Table 2).

Table 2.

Future Goals to Continue Advancement of PIF within Pharmacy Education

PIF efforts need to advance and broaden both within pharmacy education and the profession itself. Work on professional identity formation should be a focus for future strategic initiatives. Paramount to the advancement of PIF is the need for the profession to evaluate and define the professional identity of the pharmacist. As Kellar and colleagues state, “It is more important than ever that pharmacists embody a clear identity, as boundaries and scopes of practice are continuously being renegotiated, and if not careful, pharmacists risk losing their professional status. A solid professional identity can facilitate the internal regulation of pharmacists, as well as enable confidence for members to practice effectively.”7

Recommendation 6

AACP should adopt professional identity and PIF as priorities in its next strategic plan.

Recommendation 7

AACP should collaborate with other pharmacy organizations to help the profession develop and embody a clear and unified identity for practice today and tomorrow.

CONCLUSION

To successfully achieve the goals of practice transformation, pharmacy educators must deliberately support PIF in students through socialization and communities of practice. Collaboration among all stakeholder organizations, additional scholarly research, and the adoption of change management principles will be required to effectively shift the culture of pharmacy towards a common identity that transcends a diversity of practice roles and settings. Students and graduates who “think, feel, and act” like a pharmacist will have greater confidence, clarity, and leverage to be catalysts for change that advance patient care.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. Bylaws for the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. https://www.aacp.org/sites/default/files/2017-10/aacp_bylaws_revised_july_2017.pdf. Accessed April 15, 2020.

- 2.Sorensen TD. AACP Report. Leading in Dickensian times: address of the president-elect at the 2019 AACP annual meeting. Am J Pharm Educ. 2019;83(6):Article 7780 https://www.ajpe.org/content/83/6/7780/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. AACP Strategic Plan 2018-2021. https://www.aacp.org/sites/default/files/2018-10/aacp-strategic-plan.pdf. Accessed April 15, 2020.

- 4.Cruess SR, Cruess RL, Steinert Y. Supporting the development of a professional identity: general principles. Med Teach. 2019;41(6):641-649. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2018.1536260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Monrouxe LV. Identity, identification and medical education: why should we care? Med Educ . 2010;44:40-49. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Noble C, McKauge L, Clavarino A. Pharmacy student professional identity formation: a scoping review. Integr Pharm Res Pract . 2019;8:15-34. doi: 10.2147/IPRP.S162799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kellar J, Paradis E, Cees PM, Mirjam GA, Austin Z. A historical discourse analysis of pharmacist identity in pharmacy education. Am J Pharm Educ . 2020;84(9):Article 7864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elvey R, Hassell K, Hall J. Who do you think you are? pharmacists’ perceptions of their professional identity. Int J Pharm Pract. 2013;21(5):322-332. 10.1111/ijpp.12019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joint Commission of Pharmacy Practitioners. Pharmacists’ patient care process. Published May 29, 2014. https://www.pharmacist.com/sites/default/files/files/PatientCareProcess.pdf. Accessed April 29, 2020.

- 10.Pestka DL, Frail CK, Sorge LA, Funk KA, Roth McClurg RT, Sorensen TD. The practice management components needed to support comprehensive medication management in primary care clinics. JACCP. 2019;38(1):69-79. 10.1002/phar.2062. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The Patient Care Process for Delivering Comprehensive Medication Management (CMM): Optimizing Medication Use in Patient-Centered, Team-Based Care Settings. CMM in Primary Care Research Team. July 2018. http://www.accp.com/cmm_care_process. Accessed April 1, 2020.

- 12.Jarvis-Sellinger S, Pratt D, Regehr G. Competency is not enough: integrating identity formation into the medical education discourse. Acad Med. 2012;87(9):1185-90. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182604968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Boudreau JD, Snell L, Steinert Y. Reframing medical education to support professional identity formation. Acad Med . 2014;89(11):1446-1451. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Council for Pharmacy Education. Accreditation standards and key elements for the professional program in pharmacy leading to the doctor of pharmacy degree. 2015. https://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/Standards2016 FINAL.pdf. Accessed April 17, 2020.

- 15.American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. ASHP Guidelines: minimum standard for ambulatory care pharmacy practice. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2015;72(14):1221-1236. 10.2146/sp150005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.American College of Clinical Pharmacy. Standards of practice for clinical pharmacists. Pharmacotherapy. 2014;34(8):794-797. http://www.accp.com/docs/positions/guidelines/StndrsPracClinPharm_Pharmaco8-14.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.American Pharmacists Association. APhA Policy Manual 2019. https://www.pharmacist.com/policy-manual. Accessed April 10, 2020.

- 18.Medina MS, Plaza CM, Stowe CD, et al. Center for the Advancement of Pharmacy Education 2013 educational outcomes. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77(8):Article 162 10.5688/ajpe778162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.American Society of Health System Pharmacists. Glossary of Terms. https://www.ashp.org/Professional-Development/Residency-Information/Student-Residency-Guide/Glossary-of-Terms. Accessed March 13, 2020.

- 20.American Society of Health System Pharmacists. Practice Advancement Initiative 2030 Recommendations. https://www.ashp.org/Pharmacy-Practice/PAI/PAI-Recommendations. Accessed March 13, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Steinert Y. Amending Miller’s Pyramid to include professional identity formation. Acad Med . 2016;91(2):180-185. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cruess SR, Cruess RL, Steinert Y. Supporting the development of a professional identity: general principles. Med Teach. 2019;41(6):641-649. 10.1080/0142159X.2018.1536260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barab SA, Barnett MG, Squire K. Building a community of teachers: navigating the essential tensions in practice. J of the Learning Sci. 2002;11(4):495. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Noble C, O’Brien M, Coombes I, Shaw PN, Nissen L, Clavarino A. Becoming a pharmacist: students’ perceptions of their curricular experience and professional identity formation. Curr Pharm Teach Learn . 2014;6(3):327-339. 10.1016/j.cptl.2014.02.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Joynes VCT. Defining and understanding the relationship between professional identity and interprofessional responsibility: implications for educating health and social care students. Adv Health Sci Educ. 2018;23(1):133-149. 10.1007/s10459-017-9778-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mylrea MF, Gupta TS, Glass BD. Developing professional identity in undergraduate pharmacy students: a role for self-determination theory. Pharmacy (Basel Switzerland). 2017;5(2):16. doi:10.3390/pharmacy5020016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson JL. Self-authorship in pharmacy education. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77(4):69 https://www.ajpe.org/content/77/4/69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnson JL, Chauvin S. Professional identity formation in an advanced pharmacy practice experience emphasizing self-authorship. Am J Pharm Educ. 2016;80(10):172 10.5688/ajpe8010172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goldie J. The formation of professional identity in medical students: considerations for educators. Med Teach . 2012;34(9):e641-8. doi:10.3109/0142159X.2012.687476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holden MD, Buck E, Luk J, et al. Professional identity formation: creating a longitudinal framework through TIME (Transformation in Medical Education). Acad Med . 2015;90(6):761-767. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kelley KA, Stanke LD, Rabi SM, Kuba SE, Janke KK. Cross-validation of an instrument for measuring professionalism behaviors. Am J Pharm Educ. 2011;75(9):179 10.5688/ajpe759179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chishom-Burns MA, Cobb H, Duke L, McDuffie C, Kennedy WK. Development of an instrument to measure professionalism. Am J Pharm Educ. 2006;70(4):85 doi:10.5688/aj700485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hammer DP, Berger BA, Beardsley RS, Easton MR. Student professionalism. Am J Pharm Educ. 2003;67(3):96. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moseley LE, Ford CR, Wilkins EB. Using focus groups to explore evolving perceptions of student pharmacists’ curricular experiences. Am J Pharm Ed . 2020;84(1):Article 7122 10.5688/ajpe7122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Niemi PM. Medical students’ professional identity: self-reflection during the preclinical years. Med Educ. 1997;31(6):408-415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kalet A, Buckvar-Keltz L, Harnik V, et al. Measuring professional identity formation early in medical school. Med Teach . 2017;39(3):255-261. 10.1080/0142159X.2017.1270437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Swisher LL, Beckstead JW, Bebeau MJ. Factor analysis as a tool for survey analysis using a professional role orientation inventory as an example. Phys Ther . 2004;84(9):784-799. 10.1093/ptj/84.9.784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Crossley J, Vivekananda-Schmidt P. The development and evaluation of a Professional Self Identity Questionnaire to measure evolving professional self-identity in health and social care students. Med Teach. 2009;21(12):e603-e607. doi:10.3109/01421590903193547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bloom TJ, Smith JD, Rich W. Impact of pre-pharmacy work experience on development of professional identity in student pharmacists. Am J Pharm Ed. 2017;81(10):Article 6141 10.5688/ajpe6141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]