Key Points

Question

What is the spectrum of multisystem immune-related adverse events (irAEs) that occur in patients with non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs)? Do patients with multisystem irAEs have improved survival, adjusting for treatment duration?

Findings

In this multicenter cohort study of 623 patients with NSCLC treated with anti–programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) and programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) ICIs patients treated with anti–PD-(L)1 monotherapy developed multisystem irAEs, most commonly: pneumonitis thyroiditis, hepatitis thyroiditis, dermatitis pneumonitis, and dermatitis thyroiditis. Multisystem irAEs were associated with improved survival from ICIs in NSCLC, adjusting for treatment duration, in a multivariable model.

Meaning

Multisystem irAEs are associated with improved survival from immunotherapy in NSCLC.

This multicenter cohort study characterizes the spectrum of multisystem immune-related adverse events, their association with survival, and risk factors for development, in patients with non–small cell lung cancer treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Abstract

Importance

The spectrum of individual immune-related adverse events (irAEs) from anti–programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) and programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) has been reported widely, and their development is associated with improved patient survival across tumor types. The spectrum and impact on survival for patients with non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) who develop multisystem irAEs from ICIs, has not been described.

Objective

To characterize multisystem irAEs, their association with survival, and risk factors for multisystem irAE development.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This retrospective cohort study carried out in 5 academic institutions worldwide included 623 patients with stage III/IV NSCLC, treated with anti–PD-(L)1 ICIs alone or in combination with another anticancer agent between January 2007 and January 2019.

Exposures

Anti–PD-(L)1 monotherapy or combinations.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Multisystem irAEs were characterized by combinations of individual irAEs or organ system involved, separated by ICI-monotherapy or combinations. Median progression-free (PFS) and overall survival (OS) were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Differences in PFS and OS between irAE groups were assessed by multivariable models. Risk for multisystem irAE was estimated as odds ratios by multivariable logistic regression.

Results

The 623 patients included in the study were mostly men (60%, n = 375) and White (77%, n = 480). The median (range) age was 66 (58-73) years, and 148 patients (24%) developed a single irAE, whereas 58 (9.3%) developed multisystem irAEs. The most common multisystem irAE patterns in patients receiving anti–PD-(L)1 monotherapy were pneumonitis thyroiditis (n = 7, 14%), hepatitis thyroiditis (n = 5, 10%), dermatitis pneumonitis (n = 5, 10%), and dermatitis thyroiditis (n = 4, 8%). Favorable Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS) (ECOG PS = 0/1 vs 2; adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 0.27; 95% CI, 0.08-0.94; P = .04) and longer ICI duration (aOR, 1.02; 95% CI, 1.01-1.03; P < .001) were independent risk factors for development of multisystem irAEs. Patients with 1 irAE and multisystem irAEs demonstrated incrementally improved OS (adjusted hazard ratios [aHRs], 0.86; 95% CI, 0.66-1.12; P = .26; and aHR, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.38-0.85; P = . 005, respectively) and PFS (aHR, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.55-0.85; P = .001; and aHR, 0.39; 95% CI, 0.28-0.55; P < .001, respectively) vs patients with no irAEs, in multivariable models adjusting for ICI duration.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this multicenter cohort study, development of multisystem irAEs was associated with improved survival in patients with advanced NSCLC treated with ICIs.

Introduction

Anti–programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) and programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) are a vital part of the therapeutic landscape for non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).1,2,3,4,5 However, immune-related adverse events (irAEs) may lead to patient morbidity and mortality. Large case series studies in NSCLC and other tumors have identified that irAE development is associated with improved survival outcomes.6

Although the range of individual irAEs is widely reported,1,2,3,4 the prevalence, clinical patterns, and survival implications for patients who develop irAEs involving multiple organ systems (multisystem irAEs), is unknown. This multicenter cohort study characterizes the spectrum of multisystem irAEs, their association with survival, and risk factors for multisystem irAE development, in patients with NSCLC treated with ICIs.

Methods

Study Population

Patients with NSCLC treated with anti-PD(L)1 ICIs at 5 academic centers were identified. Patients aged 18 years or older, with pathologically confirmed stage III/IV NSCLC who received 1 dose or more of anti-PD(L)1 monotherapy or anti–PD(L)1-based combinations were included (eFigure 1 in the Supplement).

Data Collection

The institutional review board for each institution granted waiver of review and informed consent for this study. Patient irAEs were defined by the treating oncologist after alternative diagnoses had been excluded, based on (1) pathologic evidence of irAE, (2) multidisciplinary adjudication including 2 or more oncologists, or (3) clinical improvement with irAE-based treatment,7,8,9 in this rank order. Multisystem irAEs were defined as irAEs involving more than 1 organ system.

Statistical Analysis

Time to onset of first irAE was compared for patients with single vs multisystem irAEs using Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Median progression-free survival (PFS), overall survival (OS), and 1-year survival rates were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Differences in PFS and OS between irAE groups were assessed by multivariable proportional hazards regression. Risk for multisystem irAE was estimated as odds ratios by multivariable logistic regression. Details regarding data collection and statistical analysis are described in eMethods in the Supplement.

Results

Patient Characteristics

The clinical features of 623 patients with NSCLC (375 [60%] men and 248 [40%] women), stratified by irAE development and cohort, are outlined in the Table and eTable 1 in the Supplement, respectively. Of these patients, 148 (24%) developed 1 irAE, and 58 (9%) developed multisystem irAEs. Patients with multisystem irAEs were more likely to have a favorable Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS) (ECOG PS, 0/1; no irAE vs single irAE vs multi-irAE; 82% vs 86% vs 95%; P = .03), stage IV disease (88% vs 97% vs 98%, P < .001), be ever smokers (82% vs 83% vs 86%, P < .001), receive anticytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen-4 (anti–CTLA-4) combination ICIs (4% vs 2% vs 9%, P = .01), and sustain disease control (complete response [CR] + partial response [PR] + stable disease [SD], 28% vs 51% vs 74%; P < .001). Median ICI duration was longer in patients with multisystem irAEs (median weeks, 10.1 vs 17.1 vs 27.9, P < .001).

Table. Baseline Clinical Features of the 623 Patients With NSCLC Treated With Anti-PD(L)1 Immunotherapy.

| Characteristic | irAEs, No. (%) | P valuea | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | Single | Multiple | ||

| No. | 417 | 148 | 58 | |

| Age, median (range), y | 66 (58-73) | 65 (60-73) | 65.5 (57-73) | .89 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 249 (59.7) | 90 (60.8) | 36 (62.1) | .93 |

| Female | 168 (40.3) | 58 (39.2) | 22 (37.9) | |

| Race | ||||

| African American | 55 (13.2) | 19 (12.8) | 5 (8.6) | .71 |

| White | 323 (77.5) | 112 (75.7) | 45 (77.6) | |

| Asian | 39 (9.4) | 17 (11.5) | 8 (13.8) | |

| Smoking status | ||||

| Ever | 341 (81.8) | 123 (83.1) | 49 (84.5) | <.001 |

| Never | 74 (17.7) | 25 (16.9) | 9 (15.5) | |

| NA | 2 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Stage at diagnosis | ||||

| III | 52 (12.5) | 5 (3.4) | 1 (1.7) | <.001 |

| IV | 365 (87.5) | 143 (96.6) | 57 (98.3) | |

| ECOG PS | ||||

| 0/1 | 340 (81.5) | 127 (85.8) | 55 (94.8) | .03 |

| 2 | 77 (18.5) | 21 (14.2) | 3 (5.2) | |

| Histology | ||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 280 (67.1) | 102 (68.9) | 44 (75.9) | .35 |

| Squamous cell | 115 (27.6) | 38 (25.7) | 9 (15.5) | |

| NOS | 22 (5.3) | 8 (5.4) | 5 (8.6) | |

| Treatment received | ||||

| Monotherapy | 341 (81.8) | 135 (91.2) | 51 (87.9) | .02 |

| Combination therapy | 76 (18.2) | 13 (8.8) | 7 (12.1) | |

| +CTLA-4 | 18 (4.3) | 3 (2.0) | 5 (8.6) | .01 |

| +Chemotherapy | 30 (7.2) | 2 (1.4) | 1 (1.7) | |

| +Otherb | 28 (6.7) | 8 (5.4) | 1 (1.7) | |

| Anti–PD-(L)1 type | ||||

| PD-1 | 393 (94.2) | 142 (95.9) | 58 (100) | .14 |

| PD-L1 | 24 (5.8) | 6 (4.1) | 0 (0) | |

| ICI duration, median (range), wk | 10.1 (4.36-21) | 17.1 (6.43-42.9) | 27.9 (9.71-51.4) | <.001 |

| Best treatment response | ||||

| CR, PR, SD | 117 (28.1) | 75 (50.7) | 43 (74.1) | <.001 |

| PD | 234 (56.1) | 50 (33.8) | 12 (20.7) | |

| NA | 66 (15.8) | 23 (15.5) | 3 (5.2) | |

Abbreviations: CR, complete response; CTLA-4, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor; NA, not applicable; NOS, not otherwise specified; PD, progressive disease; PD-(L)1, programmed cell death (ligand) 1; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease.

Categorical and continuous variables were compared using χ2 and Kruskal-Wallis tests, respectively.

Other: anti-ERBB2, anti-LAG3, anti-TIM3, anti-KIR therapy; azacitidine/etinostat epigenetic priming.

Spectrum of Multisystem irAEs

The most common irAEs in patients receiving anti–PD-(L)1 monotherapy were pneumonitis (n = 64, 12%), thyroiditis (n = 53, 10%), and dermatitis (n = 47, 9%) (eFigure 2A in the Supplement). Most patients with multisystem irAEs had 2 irAEs (n = 40, 78%), and the most common first irAEs were thyroiditis (n = 22, 38%) and dermatitis (n = 13, 22%). The most common multisystem irAE patterns were pneumonitis thyroiditis (n = 7, 14%), hepatitis thyroiditis (n = 5, 10%), dermatitis pneumonitis (n = 5, 10%), and dermatitis thyroiditis (n = 4, 8%) (eFigure 3A in the Supplement).

The most common irAEs in patients receiving ICI-combinations were pneumonitis (n = 9, 9%), diarrhea/colitis (n = 5, 5%), and dermatitis (n = 4, 4%) (eFigure 2B in the Supplement). No patterns of multisystem irAEs were observed for patients receiving ICI-combinations (all n = 1) (eFigure 3B in the Supplement) owing to sample size.

Time to Onset and Risk Factors for Multisystem irAEs

Of the 199 irAE patients who had complete time to onset data (eFigure 4 in the Supplement), median time from ICI start to first irAE was 1.6 months (range, 0-36.7 months), and to second irAE was 3.25 months (range, 0-20 months). All multisystem irAEs occurred sequentially. There was no difference in time to first irAE in patients who had single vs multisystem irAEs (median, 1.6 vs 1.8 months; P = .51). Favorable ECOG PS (ECOG PS, 0/1 vs 2; adjusted odds ratio [aOR]; 0.27; P = .04) and longer ICI duration (aOR, 1.02; P < .001) were independent risk factors for development of multisystem irAEs (eTable 2 in the Supplement).

Association Between Multisystem irAEs and Survival

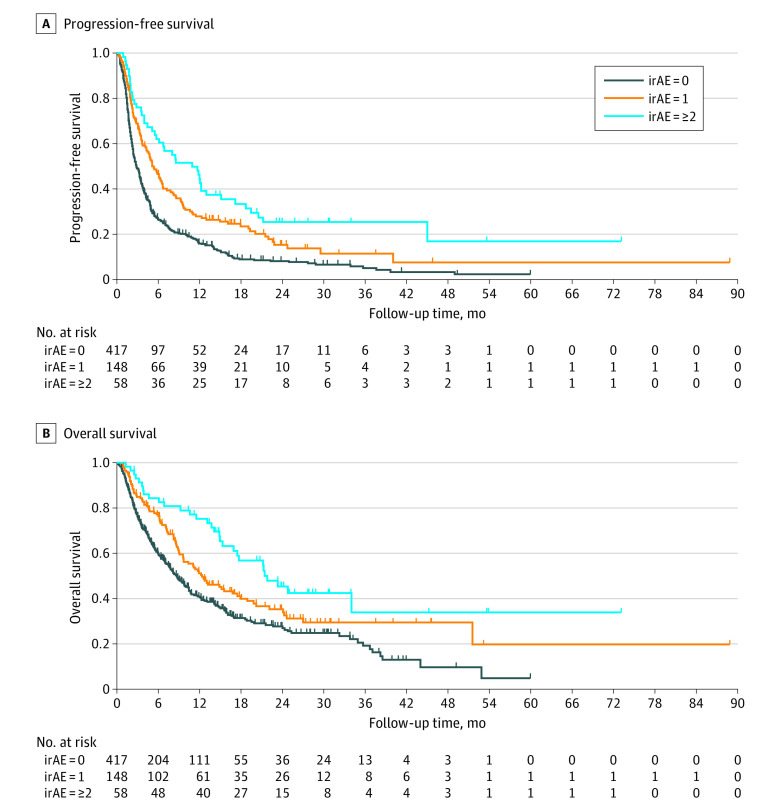

The median PFS for multisystem vs single vs no irAE groups was 10.9 months (95% CI, 5.7-13.0 months), 5.1 months (95% CI, 4.1-6.6 months) and 2.8 months (95% CI, 2.4 - 3.3 months) (P < .001), respectively (Figure). One-year PFS for multisystem vs single vs no irAE groups was 44% (95% CI, 31%-57%); 28% (95% CI, 21%-35%); and 16% (95% CI, 12%-20%), respectively. In a multivariable model, patients with 1 irAE and multisystem irAEs demonstrated incrementally improved PFS (adjusted hazard ratios [aHRs], 0.68 and 0.39, respectively, both P < .001) vs those with no irAEs (eTable 3 in the Supplement).

Figure. Progression-Free Survival and Overall Survival in Patients With NSCLC Treated With Anti–Programmed Cell Death 1 and Programmed Cell Death Ligand 1 Immunotherapy.

A, Progression-free survival, and (B) overall survival in patients with NSCLC treated with anti–programmed cell death 1 and programmed cell death ligand 1 immunotherapy. irAE Indicates immune-related adverse events; NSCLC, non–small cell lung cancer.

Patients with multisystem irAEs demonstrated the best OS among irAE groups (median months: multisystem vs single vs no irAE, 21.8 vs 12.3 vs 8.7; multisystem vs no irAEs, aHR, 0.57; P = .005; single irAEs vs no irAEs, aHR, 0.86; P = .26) (eTable 3 in the Supplement). There was a significant positive association between irAE number and PFS (HR, 0.67; P < .001) and OS (HR, 0.79; P = .003), respectively (eTable 4 in the Supplement).

Sensitivity analysis using multisystem irAEs as a time-varying covariate, stratified by cohort (Hopkins/non-Hopkins), and restricting to patients treated with ICI-monotherapy demonstrated results consistent with our main analysis (eFigures 5, 6, and 7, eTables 5, 6, and 7 in the Supplement). An analysis assessing the individual irAE-survival association suggested that development of diarrhea/colitis and dermatitis, among the 4 most common irAEs in this study, appear to drive the favorable survival observed (eTables 8 and 9 in the Supplement). In patients with multisystem irAEs, those with either all low-grade (<3) irAEs or at least 1 high-grade (≥3) irAE demonstrated improved PFS, yet only the former derived a significant OS benefit from ICIs, vs patients without irAEs (eTable 10 and eFigure 8 in the Supplement). Schoenfeld residuals showed that the proportional hazard assumption was not violated.

Discussion

The findings of this multicenter cohort study suggest that patients with NSCLC treated with ICI-monotherapy may develop multisystem irAEs including: pneumonitis thyroiditis, hepatitis thyroiditis, dermatitis pneumonitis, and dermatitis thyroiditis. In addition, we identified an association between multisystem irAEs and improved survival in NSCLC, which persists after adjustment for treatment duration.

In this study, the overall incidence of single irAEs in those treated with PD-(L)1 monotherapy and ICI-combinations, is consistent with published prospective trials.2,3,4,5 Although meta-analyses and systematic reviews have characterized single irAEs that occur from ICIs, there is a paucity of data regarding multisystem irAEs, limited to the myositis, myocarditis, myasthenia syndrome.10 Although in this study multisystem irAEs represented a combination of the most common individual irAEs, it is possible they may share common pathobiology, such as human leucocyte antigen genotypes or autoantibody formation.11,12

Prior studies have described an association between irAE development and improved survival in NSCLC and other tumors, and between longer ICI duration and irAE development.5,6,13 The findings of this study demonstrated that multisystem irAEs were associated with improved OS and PFS, and that this association is more prominent with increasing irAE count. Although patients with multisystem irAEs received a longer ICI treatment course, the association between irAE count and improved survival is sustained after adjusting for ICI duration, suggesting that these patients experience greater therapeutic effect and higher irAE risk.

Limitations

The small percentage of the cohort that developed multisystem irAEs and its retrospective nature are limitations of this study. We acknowledge that these data may only be generalizable to similar populations.

Conclusions

This study described patterns of multisystem irAEs in patients with NSCLC treated with ICIs, and demonstrates an association between multisystem irAEs and survival.

eMethods

eReferences

eTable 1. Baseline clinical features of NSCLC patients treated with anti-PD-(L)1 immunotherapy, by cohort

eTable 2. Multivariate logistic regression of risk factors for developing multi-system irAEs in patients with NSCLC treated with anti-PD(L)1 immunotherapy

eTable 3. Multivariate Cox regression model of (A) overall and (B) progression-free survival in patients with NSCLC treated with anti-PD(L)1 immunotherapy, utilizing multi-system irAEs as a categorical variable

eTable 4. Multivariate Cox regression model of (A) overall and (B) progression-free survival in patients with NSCLC treated with anti-PD(L)1 immunotherapy, utilizing multi-system irAEs as a continuous variable

eTable 5. Multivariate Cox regression model of (A) overall and (B) progression-free survival in patients with NSCLC treated with anti-PD(L)1 immunotherapy, utilizing multi-system IrAEs as a time-varying covariate

eTable 6. Multivariate Cox regression model of (A) overall and (B) progression-free survival in patients with NSCLC treated with anti-PD(L)1 monotherapy, with a sensitivity analysis stratified by cohorts

eTable 7. Multivariate Cox regression model of (A) overall and (B) progression-free survival in patients with NSCLC treated with anti-PD1 monotherapy

eTable 8. Multivariate Cox regression model of (A) overall and (B) progression-free survival in patients with NSCLC treated with anti-PD(L)1 immunotherapy, utilizing the four most common single irAEs as binary variables

eTable 9. Multivariate Cox regression model of (A) overall and (B) progression-free survival in patients with NSCLC treated with anti-PD(L)1 immunotherapy, utilizing the four most common single irAEs as binary variables, overall and stratified by cohorts

eTable 10. Multivariate Cox regression model of multi-system irAE grade on (A) overall and (B) progression-free survival in patients with NSCLC treated with anti-PD(L)1 immunotherapy

eFigure 1. Study design: inclusion and exclusion criteria

eFigure 2. Spectrum of irAEs for patients with NSCLC receiving (A) mono- or (B) combination anti-PD(L)1 immunotherapy

eFigure 3. Chord diagram displaying the spectrum of multi-system irAEs for patients with NSCLC receiving (A) mono- or (B) combination anti-PD(L)1 immunotherapy

eFigure 4. Time to onset of irAE in all patients with NSCLC after anti-PD(L)1 immunotherapy

eFigure 5. (A) Progression-free survival and (B) overall survival in patients with NSCLC from the Johns Hopkins cohort treated with anti-PD(L)1 immunotherapy, with no irAEs, single irAEs, and multi-system irAEs

eFigure 6. (A) Progression-free survival and (B) overall survival in patients with NSCLC from the non-Johns Hopkins cohorts treated with anti-PD(L)1 immunotherapy, with no irAEs, single irAEs, and multi-system irAEs

eFigure 7. (A) Progression-free survival and (B) overall survival in patients with NSCLC treated with anti-PD(L)1 monotherapy, with no irAEs, single irAEs, and multi-system irAEs

eFigure 8. (A) Progression-free survival and (B) overall survival in patients with NSCLC treated with anti-PD(L)1 immunotherapy, who had no irAEs; all <G3 multi-system irAEs; and at least 1 ≥G3 multi-system irAEs

References

- 1.Garon EB, Rizvi NA, Hui R, et al. ; KEYNOTE-001 Investigators . Pembrolizumab for the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(21):2018-2028. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1501824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fehrenbacher L, von Pawel J, Park K, et al. Updated efficacy analysis including secondary population results for OAK: a randomized phase III study of atezolizumab versus docetaxel in patients with previously treated advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2018;13(8):1156-1170. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2018.04.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brahmer J, Reckamp KL, Baas P, et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced squamous-cell non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(2):123-135. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borghaei H, Paz-Ares L, Horn L, et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(17):1627-1639. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1507643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hellmann MD, Paz-Ares L, Bernabe Caro R, et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(21):2020-2031. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1910231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Das S, Johnson DB. Immune-related adverse events and anti-tumor efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors. J Immunother Cancer. 2019;7(1):306. doi: 10.1186/s40425-019-0805-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brahmer JR, Lacchetti C, Schneider BJ, et al. ; National Comprehensive Cancer Network . Management of immune-related adverse events in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(17):1714-1768. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.77.6385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thompson JA. New NCCN guidelines: recognition and management of immunotherapy-related toxicity. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2018;16(5S):594-596. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2018.0047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Puzanov I, Diab A, Abdallah K, et al. ; Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer Toxicity Management Working Group . Managing toxicities associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: consensus recommendations from the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer (SITC) Toxicity Management Working Group. J Immunother Cancer. 2017;5(1):95. doi: 10.1186/s40425-017-0300-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suzuki S, Ishikawa N, Konoeda F, et al. Nivolumab-related myasthenia gravis with myositis and myocarditis in Japan. Neurology. 2017;89(11):1127-1134. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hasan Ali O, Berner F, Bomze D, et al. Human leukocyte antigen variation is associated with adverse events of checkpoint inhibitors. Eur J Cancer. 2019;107:8-14. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2018.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iwama S, De Remigis A, Callahan M, Slovin S, Wolchok J, Caturegli P. Pituitary expression of CTLA-4 mediates hypophysitis secondary to administration of CTLA-4 blocking antibody. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6(230):230ra45-230ra45. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maher VE, Fernandes LL, Weinstock C, et al. Analysis of the association between adverse events and outcome in patients receiving a programmed death protein 1 or programmed death ligand 1 antibody. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(30):2730-2737. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.00318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods

eReferences

eTable 1. Baseline clinical features of NSCLC patients treated with anti-PD-(L)1 immunotherapy, by cohort

eTable 2. Multivariate logistic regression of risk factors for developing multi-system irAEs in patients with NSCLC treated with anti-PD(L)1 immunotherapy

eTable 3. Multivariate Cox regression model of (A) overall and (B) progression-free survival in patients with NSCLC treated with anti-PD(L)1 immunotherapy, utilizing multi-system irAEs as a categorical variable

eTable 4. Multivariate Cox regression model of (A) overall and (B) progression-free survival in patients with NSCLC treated with anti-PD(L)1 immunotherapy, utilizing multi-system irAEs as a continuous variable

eTable 5. Multivariate Cox regression model of (A) overall and (B) progression-free survival in patients with NSCLC treated with anti-PD(L)1 immunotherapy, utilizing multi-system IrAEs as a time-varying covariate

eTable 6. Multivariate Cox regression model of (A) overall and (B) progression-free survival in patients with NSCLC treated with anti-PD(L)1 monotherapy, with a sensitivity analysis stratified by cohorts

eTable 7. Multivariate Cox regression model of (A) overall and (B) progression-free survival in patients with NSCLC treated with anti-PD1 monotherapy

eTable 8. Multivariate Cox regression model of (A) overall and (B) progression-free survival in patients with NSCLC treated with anti-PD(L)1 immunotherapy, utilizing the four most common single irAEs as binary variables

eTable 9. Multivariate Cox regression model of (A) overall and (B) progression-free survival in patients with NSCLC treated with anti-PD(L)1 immunotherapy, utilizing the four most common single irAEs as binary variables, overall and stratified by cohorts

eTable 10. Multivariate Cox regression model of multi-system irAE grade on (A) overall and (B) progression-free survival in patients with NSCLC treated with anti-PD(L)1 immunotherapy

eFigure 1. Study design: inclusion and exclusion criteria

eFigure 2. Spectrum of irAEs for patients with NSCLC receiving (A) mono- or (B) combination anti-PD(L)1 immunotherapy

eFigure 3. Chord diagram displaying the spectrum of multi-system irAEs for patients with NSCLC receiving (A) mono- or (B) combination anti-PD(L)1 immunotherapy

eFigure 4. Time to onset of irAE in all patients with NSCLC after anti-PD(L)1 immunotherapy

eFigure 5. (A) Progression-free survival and (B) overall survival in patients with NSCLC from the Johns Hopkins cohort treated with anti-PD(L)1 immunotherapy, with no irAEs, single irAEs, and multi-system irAEs

eFigure 6. (A) Progression-free survival and (B) overall survival in patients with NSCLC from the non-Johns Hopkins cohorts treated with anti-PD(L)1 immunotherapy, with no irAEs, single irAEs, and multi-system irAEs

eFigure 7. (A) Progression-free survival and (B) overall survival in patients with NSCLC treated with anti-PD(L)1 monotherapy, with no irAEs, single irAEs, and multi-system irAEs

eFigure 8. (A) Progression-free survival and (B) overall survival in patients with NSCLC treated with anti-PD(L)1 immunotherapy, who had no irAEs; all <G3 multi-system irAEs; and at least 1 ≥G3 multi-system irAEs