Abstract

Oral anti-cancer medications (OAMs) are frequently used to treat patients with cancer. Unlike intravenous chemotherapy, OAMs are covered by prescription drug plans. We examined barriers to initiation of OAMs in 116 prostate and kidney cancer patients (149 unique prescriptions). We found that the median time from initial prescription to prior authorization was 3 days and the median time from initial prescription to patient receipt of drug was 12 days. Seventy three percent of all prescriptions required two or more phone calls and 40% required five or more calls by clinic staff. Out of 107 prescriptions with data available, 54% utilized financial assistance and those required significantly more phone calls (P=0.0001) and led to a longer median time to drug obtainment (P=0.003) compared to those who did not utilize financial assistance. In those with both initial and final copay information available, the initial out-of-pocket mean and median copayments were $1226 and $329.73, but dropped to $124.57 and $25 respectively after utilization of copayment assistance programs, excluding those with a $0 final copay. These early observations suggest that a more efficient process for initiation of OAMs is needed.

Keywords: Oral anticancer medications, oncology, drug costs, financial toxicity in oncology

Summary

Oral anti-cancer medications are frequently used to treat patients with cancer. We found significant time and energy burdens in obtaining these drugs.

Over 50 oral anticancer medications (OAMs) have been approved since 1998 making treatment possible and more convenient for many patients.1,2 Unlike office administered chemotherapy, which is covered as a medical benefit by insurance plans, OAMs are obtained through a patient’s prescription coverage. Although anecdotally providers discuss the significant burden that is placed on them to help patients receive OAMs, there is little empiric data that describes the effort and time spent to obtain these drugs. Access to these data is complicated for multiple reasons. First, there is heterogeneity among prescription plans regarding the requirements for prior authorization for OAMs and the contracted specialty pharmacies to fill them. Second, cost sharing varies substantially based on insurance; for example, many Medicare patients will face very high co-payments with their initial drug fills as they enter the coverage gap.3 Third, patient assistance programs (PAPs) may provide some relief, but accessing them can be time-consuming and complicated due to applications involved, the availability of funds and restrictions on eligibility.3 The reasons described above are not clear to providers at the time of prescribing and require significant staff effort to resolve. This effort has not previously been quantified as no readily available datasets to address this question exist.

In an initial step to characterize the barriers to timely initiation of oral therapy, we describe our efforts obtaining on-label OAMs in a disease-specific academic medical oncology practice. Because of the multiple parties involved for each prescription (patient, insurer, specialty pharmacy, industry and foundation co-payment PAPs), we sought to granularly quantify and qualitatively describe the clinic staff’s efforts to obtain OAMs. We focused on metastatic prostate and renal cell cancers, two diseases for which OAMs are frequently used.

Methods

Clinical setting

We conducted a retrospective review of prescriptions written for on-label recommended OAMs for advanced prostate (abiraterone and enzalutamide) and renal cell carcinoma (sunitinib, pazopanib, axitinib, everolimus and sorafenib). To identify patients, we accessed nurse-maintained clinic tracking logs for OAMs between August 1st, 2014 and August 31st, 2015. During the study period, four attending physicians, two advanced practice clinicians and three registered nurses were involved in the care of these patients.

Data source

The tracking sheets, which are maintained for all patients prescribed OAMs, are used by the clinic staff to organize data regarding patients’ OAMs prescriptions. Notes about phone calls, pharmacy and copayment information, patient specific notes and other data are kept on these logs. In addition, we searched the electronic medical records for incoming and outgoing telephone phone calls.

Data elements and measures

We collected demographics, insurance coverage, use of copayment PAPs and specialty pharmacy assignment. In addition, we measured the number of phone calls involving clinic staff required to obtain a drug, and reasons for phone calls. We also recorded the date the prescription was initiated, date prior authorization was received (if applicable) and the date drug was received or initiated by the patient. When available, any copayment information was recorded. Time in days and number of calls were summarized by whether the patient received co-pay assistance. Differences were compared using Wilcoxon-rank sum tests. This study was approved by the Fox Chase Cancer Center’s Institutional Review Board.

Results

Prescription characteristics

Of 116 patients examined, 55% had renal cell carcinoma and 45% had prostate cancer. The median age was 65 years (range: 27–88), 85% percent were male, 89% white, and 77% had prescription drug coverage. Of note, only 3 patients were known to not have prescription drug coverage with status of the rest (21%) being unknown. There were 149 unique prescriptions written during the study’s time period. Four specialty pharmacies dispensed almost 70% of all prescriptions. In 32% of prescriptions, the initially contacted specialty pharmacy transferred the prescription to another pharmacy. Table 1 shows the results for prescription details, phone calls made, copays incurred and financial assistance obtained for patients.

Table 1:

Patient Characteristics and Variables Involved in Obtaining Oral Anticancer Medications. Unit of analysis is prescriptions.

| Prostate Carcinoma | Renal Cell Carcinoma | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PATIENT CHARACTERISTICS | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) |

| # of Rx | 54 (36) | 95 (64) | 149 (100) |

| # of patients | 51 (44) | 65 (56) | 116 (100) |

| # of patients with Prescription Drug Coverage | 43 (83) | 46 (72) | 89 (77) |

| # of patients without Prescription Drug Coverage | 0 (0) | 3 (5) | 3 (2) |

| # of patients with unknown status of Prescription | 9 (17) | 15 (23) | 24 (21) |

| Drug Coverage | |||

| RX DETAILS | |||

| Did the Initial Pharmacy Transfer the OAM Rx to another Pharmacy to be Dispensed | |||

| Yes | 18 (33) | 29 (31) | 47 (32) |

| No | 36 (67) | 66 (69) | 102 (68) |

| Date of Rx to Prior Authorization Approval Interval | 44Rx | 68 records Rx | 112 Rx |

| Mean | 6 days (0–45) | 5.6 days (0–81) | 6 days (0–81) |

| Median | 3.5 days | 3 days | 3 days |

| Date of Rx to Rx Initiation Interval | 54records | 93 records | 147records |

| Mean | 16.8 days (0–62) | 13.2 days (0–42) | 14.5 days (0–62) |

| Median | 12.5 days | 11 days | 12 days |

| PHONE CALLS INVOLVING CLINIC STAFF | |||

| Total # of phone calls (to and from clinic) | 280 | 328 | 608 |

| Average number of phone calls per patient | 5.5 | 5 | 5.25 |

| Mean (Range) # of phone calls/prescription | 5 (0–22) | 3.5 (0–15) | 4 (0–22) |

| 0–1 calls | 8 (15) | 32 (34) | 40 (27) |

| 2–4 calls | 18 (33) | 31 (33) | 49 (33) |

| 5+ calls | 28 (52) | 32 (34) | 60 (40) |

| Parties Involved | |||

| # Pharmacy | 158 (56) | 208 (63) | 366 (60) |

| # Patient/ Family | 83 (30) | 100 (30) | 183 (30) |

| # Other | 39 (14) | 20 (6) | 59 (10) |

| Subject of Call | |||

| # Prior Authorization | 91 (33) | 53 (16) | 144 (24) |

| # Insurance | 54 (19) | 87 (27) | 141 (23) |

| # Transferring Rx | 16 (6) | 20 (6) | 36 (6) |

| # Misc. Medication Questions | 79 (28) | 127 (39) | 206 (34) |

| # Other | 40 (14) | 41 (13) | 81 (13) |

| COPAYS AND FINANCIAL ASSISTANCE | |||

| Any financial data available | 45 Rx | 62 Rx | 107 Rx |

| Initial Copay per month | 25Rx | 31Rx | 56 Rx |

| # Rx copay $0 | 1 (4) | 2 (6) | 3 (5) |

| # Rx copay $1 – $100 | 8 (32) | 12 (39) | 20 (36) |

| # Rx copay > $100 | 16 (64) | 17 (55) | 33 (59) |

| Mean, median | $1679.22, $445.15 | $973.18, $150 | $1292.90, $250 |

| Range | $20 – $9453.15 | $3.60 – $3729.81 | $3.60 – $9453.15 |

| Assistance program used | 25 Rx | 33 Rx | 58 Rx |

| Final Copay per month | 32 Rx | 44 Rx | 76 Rx |

| # Rx copay $0 | 18 (56) | 19 (43) | 37 (49) |

| # Rx copay $1 – $100 | 14 (44) | 22 (50) | 36 (47) |

| # Rx copay > $100 | 0 (0) | 3 (7) | 3 (4) |

| Mean, median | $31, $30 | $109.40, $25 | $81.26, $25 |

| Range | $2.50 – $75 | $3.60 – $1056.44 | $2.50 – $1056.44 |

NOTE: “Days” refer to calendar days, not business days. Copays reported are for a monthly supply. Mean, median, and range values for initial and final copays do not include Rx with $0 copays.

Time to prior authorization and receipt of medications

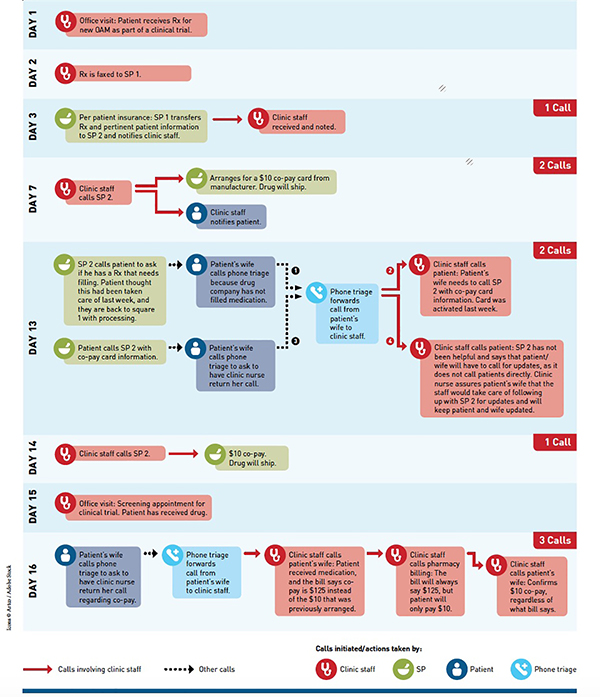

The median time from initial prescription to prior authorization was 3 days (range: 0–81) and the median time from initial prescription to patient receipt of the drug was 12 calendar days (range: 0–62). One hundred and nine (73%) of prescriptions required two or more phone calls and 60 (40%) required five or more calls. Figure 1 is an example of a typical patient’s sixteen-day process to obtain an on-label OAM with 9 phone calls made by the nursing staff.

FIGURE.

Sample Process of Obtaining and Initiating an OAM for RCC: 9 Calls Involving Clinic Staffa

OAM indicates oral anticancer medication; RCC, renal cell carcinoma; SP, specialty pharmacy.

a “Real-life” example of 48-year-old male patient with metastatic RCC and his path for obtaining a single OAM.

Co-payment information

Some financial information was available for 107 prescriptions (72%). Fifty-eight prescription fills had documentation of utilizing financial assistance: eight received a drug voucher or free limited supply; fifty received a grant or copayment card. Examining the 38 prescription fills with complete (initial and final) co-payment information, two prescriptions initially had a zero dollar copayment. The remaining 36 initially had mean and median copayments of $1226 and $329.73 (range: $3.6-$6000). For final copayment data, 17 of the 38 prescriptions had $0 copay, and the remaining 21 prescriptions had a mean and median copayment of $124.57 and $25 (range: $3.60-$1056.44). See Table 1 for all available copayment information. Comparing prescriptions that did or did not require financial assistance showed statistically significant differences in median time from prescription to drug obtainment (P=0.003) and mean number of phone calls made per prescription (P=0.0001). See Table 2 for details.

Table 2:

Time and phone calls required to obtain drugs for patients depending on whether financial assistance was required.

| Financial Assistance (58 Rx) | No documented Financial Assistance (91 Rx) | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median time from prescription to prior authorization (days) | 3 (0–52) | 3 (0–83) | 0.25 |

| Median time from prescription to drug obtainment (days) | 15 (0–62) | 10 (0–49) | 0.003 |

| Mean number of phone calls per prescription | 3.2 (0–8) | 2.0 (0–8) | 0.0001 |

NOTE: “Days” refer to calendar days, not business days. No initiation period was available for one individual for whom it took 83 days to receive a prior authorization thus resulting in a smaller range.

Discussion

In a genitourinary oncology patient cohort being treated by a sub-specialized group of providers, we report on a substantial and unique barrier to timely initiation of oral anticancer medications—time and effort of clinical staff and patients—a challenge not present with the use of intravenous oncology drugs. Although all drugs were prescribed on-label, approximately 50% of calls were for prior authorization and insurance barriers. With the median time from prescription to receipt of drugs being 12 days, many patients waited weeks to start their drug for no reason other than the work required to obtain them. At a time when increasing value in healthcare is becoming a major focus of reform, the extra work and time imposed by this model creates waste and reduces value for all parties involved.4

We believe these data for the first time provide empiric insight into the real-world experience that providers face when prescribing OAMs. We also provide initial evidence that the need to obtain financial assistance leads to a statistically—and potentially clinically—significant additional delay in obtaining OAMs. This has face validity as obtaining financial assistance for patients requires filling out applications, calling foundations, obtaining patient financial documents, and working through administrative hurdles for the clinic staff. Thus, policies that would streamline the financial assistance process would be beneficial, although would not eliminate a delay that still persisted for patients who did not need financial assistance.

Our findings have implications for both clinical care and research. A delay in prompt initiation of care by several weeks may lead to clinical deterioration of patients as well as significant anxiety, although both of these outcomes need to be further evaluated prospectively. The nursing logs and phone call records we reviewed, documented confusing and frustrating efforts to navigate through pre-authorizations and PAPs. In support of this, a recent study by Zafar et al. investigated PAPs for anticancer medications, and found that as a whole, the industry-sponsored programs lacked transparency in regard to the eligibility criteria and actual financial benefit available to patients.3 The authors concluded that “more work is needed in understanding how these programs affect practice patterns, outcomes, and the overall cost of cancer care.” Our findings extend the discussion surrounding the many barriers to efficient obtainment of OAMs, and the impact of the process on clinic staff and patients.

Although limited, our co-payment data also provides information regarding the importance of copayment assistance programs in providing access to these treatments. Fifty eight of the 107 prescriptions with copayment data available utilized some type of financial assistance. Given the missing data, this likely understates the true need for co-payment assistance, which is particularly notable since 77% of our patient sample had prescription coverage. Out of the remaining 23%, only 3 were known to not have prescription drug coverage and therefore, no analysis based on whether one had or did not have drug coverage was possible. In contacting hotlines for various industry sponsored assistance programs, Zafar et al. found the average of reported patient out-of-pocket co-payments to be $21, with a range of $0-$75, consistent with our findings of 49% having $0 copay, but the remaining 51% having a mean and median copay of $81 and $25 respectively. This highlights that the cost control strategies (such as prior authorizations and co-sharing) imposed by payers were resource intensive and diverted staff resources from patient care, while at the end, very few patients had co-pays over $100. Although co-payments were initially developed to overcome overuse of unnecessary care5, for OAMs they may instead serve as a barrier by requiring patients and staff to seek out co-payment assistance to access drugs.

Practice level quality improvement projects to improve access to OAMs will need to account for the heterogeneity of patients’ insurance coverage for treatments and should include adequate staff to address these issues. The scenario shown in Figure 1 was not uncommon and requires attentive and dedicated staff to ensure that information is transmitted among parties accurately and efficiently. New research methods to address disparities in care will need to be developed to adjust for the use of PAPs and other resources that may not be apparent in claims data.

Our study does have several limitations. This was a retrospective analysis and the tracking sheets were not designed for prospective data collection. The staff may not have recorded all the phone calls, so we may have underestimated the number of phone calls made. We also did not collect information on faxes received or sent, or the length of phone calls. The days reported were calendar days, not business days, and thus could account for some of the delays in prior authorization and drug obtainment. The source of the co-payment financial support was not recorded in all cases and could have come from manufacturers or patient support foundations. In addition, given the focus of our practice, we only evaluated on-label treatments for renal cell cancer and prostate cancer. However, the issues we identified were related to insurance characteristics (such as the need for prior authorization), rather than disease-specific issues, and thus we expect that these barriers would be relevant to patients treated on-label for other cancers where OAMs are used (over 60 OAMs are currently FDA approved for cancer patients). We would expect that patients receiving off-label treatments might have longer delays. Finally we had a stable staff focusing on only two diseases. It is likely that a practice focusing on a wider range of diseases or with a less experienced staff would have greater delays due to their lack of familiarity with disease specific assistance programs or other clinical issues.

Conclusion

Processes to fill on-label prescriptions for OAMs are heterogeneous and involve multiple parties, which can lead to delays in treatment initiation. As payers and health care providers examine methods for quality improvement, they should consider improved processes to facilitate prompt initiation of OAMs.

Summary Statement.

Oral anti-cancer medications (OAMs) are frequently used to treat patients with cancer. Unlike intravenous chemotherapy, OAMs are covered by prescription drug plans. We examined barriers to initiation of OAMs.

We found that the median time from initial prescription to prior authorization was 3 days and the median time from initial prescription to patient receipt of drug was 12 days.

Seventy three percent of all prescriptions required two or more phone calls and 40% required five or more calls by clinic staff.

Fifty four percent of all prescriptions with data available utilized financial assistance and for most patients final copays were <$100, but required a significant amount of work by clinic staff.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by award P30CA006927 from the National Cancer Institute.

References:

- 1.Conti RM, Fein AJ, Bhatta SS. National trends in spending on and use of oral oncologics, first quarter 2006 through third quarter 2011. Health affairs. October 2014;33(10):1721–1727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu G, Franssen E, Fitch MI, Warner E. Patient preferences for oral versus intravenous palliative chemotherapy. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. January 1997;15(1):110–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zafar SY, Peppercorn J, Asabere A, Bastian A. Transparency of Industry-Sponsored Oncology Patient Financial Assistance Programs Using a Patient-Centered Approach. Journal of oncology practice. January 31 2017:JOP2016017509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nabhan C, Horner G, Howell MD. Lean: Targeted Therapy for Care Delivery. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network : JNCCN. February 2017;15(2):271–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Newhouse JP, Manning WG, Morris CN, et al. Some interim results from a controlled trial of cost sharing in health insurance. The New England journal of medicine. December 17 1981;305(25):1501–1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]