Abstract

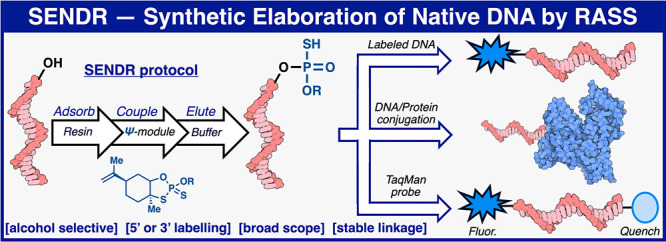

Controlled site-specific bioconjugation through chemical methods to native DNA remains an unanswered challenge. Herein, we report a simple solution to achieve this conjugation through the tactical combination of two recently developed technologies: one for the manipulation of DNA in organic media and another for the chemoselective labeling of alcohols. Reversible adsorption of solid support (RASS) is employed to immobilize DNA and facilitate its transfer into dry acetonitrile. Subsequent reaction with P(V)-based Ψ reagents takes place in high yield with exquisite selectivity for the exposed 3′ or 5′ alcohols on DNA. This two-stage process, dubbed SENDR for Synthetic Elaboration of Native DNA by RASS, can be applied to a multitude of DNA conformations and sequences with a variety of functionalized Ψ reagents to generate useful constructs.

Short abstract

The development of synthetic elaboration of native DNA by reversible adsorption of solid support (SENDR) is presented, and its utility is demonstrated in multiple examples relevant to the fields of biology through chemistry.

Introduction

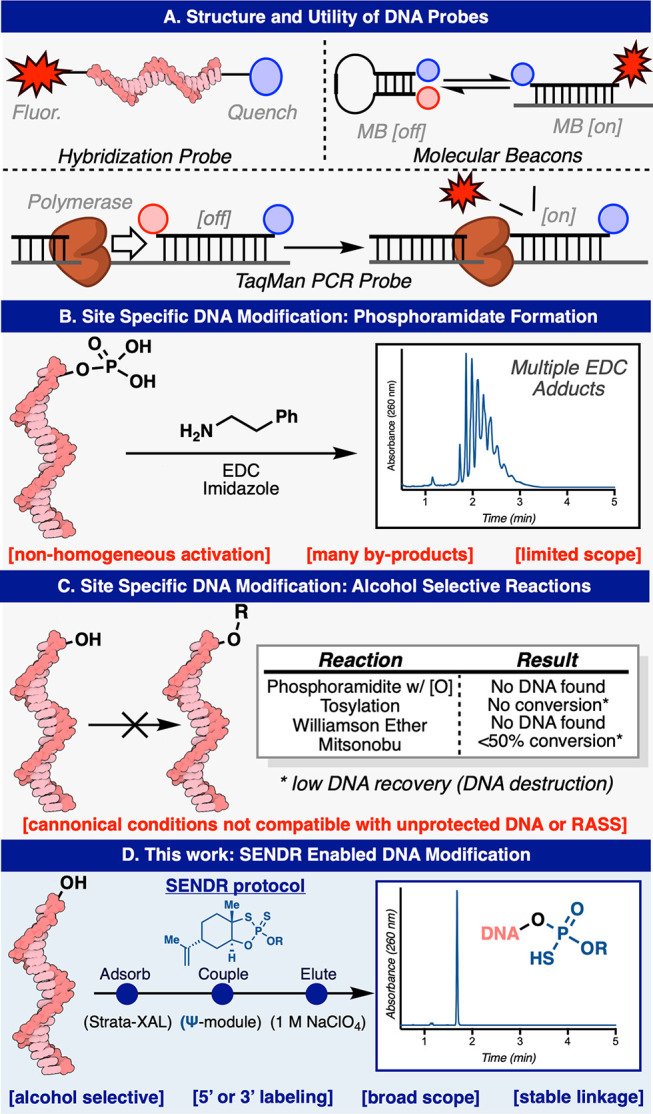

DNA conjugates are ubiquitous in the fields of chemical biology, biophysics, and diagnostics (Figure 1A).1 Indeed, DNA conjugate technology has provided the basis for many modern technological advances.1 For example, DNA-PAINT conjugates enable super resolution microscopy,2−5 and TaqMan PCR probes have revolutionized precision diagnostics.6−11 These hybridization probes all require custom DNA oligomer conjugates that are precisely functionalized and homogeneous.1 Clearly, such homogeneous functionalization is a challenge of the highest magnitude for chemoselective chemical bioconjugation.

Figure 1.

Modification of native DNA. (A) Structure and utility of some DNA hybridization probes (B) State of the art in site selective chemical DNA bioconjugation: Phosphoramidate formation. (C) Classical organic alcohol selective reactions. (D) This work: SENDR.

Hybridization probes operate through the exquisite molecular recognition ability that a single strand of DNA displays toward its complementary sequence.1,12,13 The ability for DNA to take on well-defined conformations, set by inter- and intramolecular interactions, allows for another dimension of selectivity.1,14,15 Detecting these molecular interactions usually requires the incorporation of a fluorophore or radioactive moiety.1 Thus, DNA–probe conjugates form the foundation that allows for ubiquitous biochemical and diagnostic techniques such as Southern16 and Northern blotting,17 molecular beacons,1,15 and TaqMan qPCR.6−11

Although these techniques are universal, chemical synthesis of custom DNA conjugates can be cost-prohibitive and labor-intensive.1 As a result, less sensitive techniques not requiring precision-labeled DNA are often utilized.1 As DNA tagging becomes increasingly popular, massively multiplexed experiments would require thousands of chemically synthesized and modified oligonucleotides. Thus, simple ways to precisely and inexpensively build DNA conjugates, ideally from ubiquitous substrate building blocks, would be of great interest to researchers across many fields.

Chemical Approach to Site-Specific DNA Modification

Although many chemical and biochemical methods exist for the random labeling of native DNA, these methods produce nonhomogenous products that contain modified bases determined randomly or statistically.18−22 In some cases, DNA with randomly incorporated labels can be useful, but unlocking the total power of DNA as a molecular recognition probe requires site-selective incorporation of the desired tag. Although biochemical methods exist for the site-specific labeling of native DNA, they are not without their drawbacks.23−27 Many require custom synthesis of transfer small molecules, and the scope can be limited or the enzymes might be noncommercial.23−27

One classic method for selective modification of native DNA exists, although it presents with several limitations. The method first reported in 1983 by Orgel relies on a water-soluble carbodiimide (EDC), imidazole, and amines, which when combined furnish a phosphoramidate linkage between native DNA bearing a 5′ phosphate group and an amine of interest.28−32 Although this method is widely cited, its scope is limited to simple amines, and the reaction and workup must be conducted rapidly to avoid premature hydrolysis of the carbodiimide. In our hands, this method proved unreliable, providing a product that was contaminated with many EDC adducts, even after multiple attempts varying concentration and stoichiometry (Figure 1B, and also see Supporting Information). Multiple other classical alcohol selective reactions were investigated via the RASS platform in an attempt to develop an alternative bioconjugation route. Unfortunately, applying canonical conditions of a phosphoramidite coupling (and subsequent oxidation), tosylation, Williamson ether synthesis, and Mitsunobu reactions resulted in DNA damage and little to no DNA recovery (Figure 1C, and see Supporting Information).

In an attempt to remedy this, we set out to combine two technologies previously disclosed from our respective (P.S.B. and P.E.D.) laboratories. Specifically, P(V)-based Ψ-reagents have been established to construct stereochemically pure phosphorothioate linkages between hydroxyl nucleophiles in a chemoselective fashion (Figure 1D).33,34 While upon first glance, it seemed simple to employ this reagent system for the labeling of DNA 5′ or 3′ hydroxyl groups, Ψ-loaded reagents are typically employed in dry acetonitrile, as they are readily hydrolyzed in water.33,34 In contrast, because of the highly charged nature of the native DNA phosphate backbone, these polymeric substrates are insoluble in most organic solvents and usually require significant water content to solubilize it in a mixed aqueous/organic system.35,36 These mutually exclusive properties precluded the simple adaptation of Ψ for the purposes of site-specific DNA labeling. Reversible adsorption of solid support (RASS), an alternate paradigm for performing chemistry on-DNA, thus seemed like an ideal merger with Ψ-based chemistry. RASS is a process that allows for the adsorption of biomacromolecules onto a solid support to facilitate their transfer into solvents or reaction paradigms that would previously be considered incompatible.37−40 In this manifestation, DNA is adsorbed onto a polystyrene-based cationic support, through a simple mixing procedure, and the solvent exchanged (by simple washing and drying) into near-anhydrous conditions. In turn, water-incompatible reactions are enabled. Herein, we describe the union of Ψ and RASS for the site-specific labeling of oligonucleotides, Synthetic Elaboration of Native DNA by RASS: SENDR.

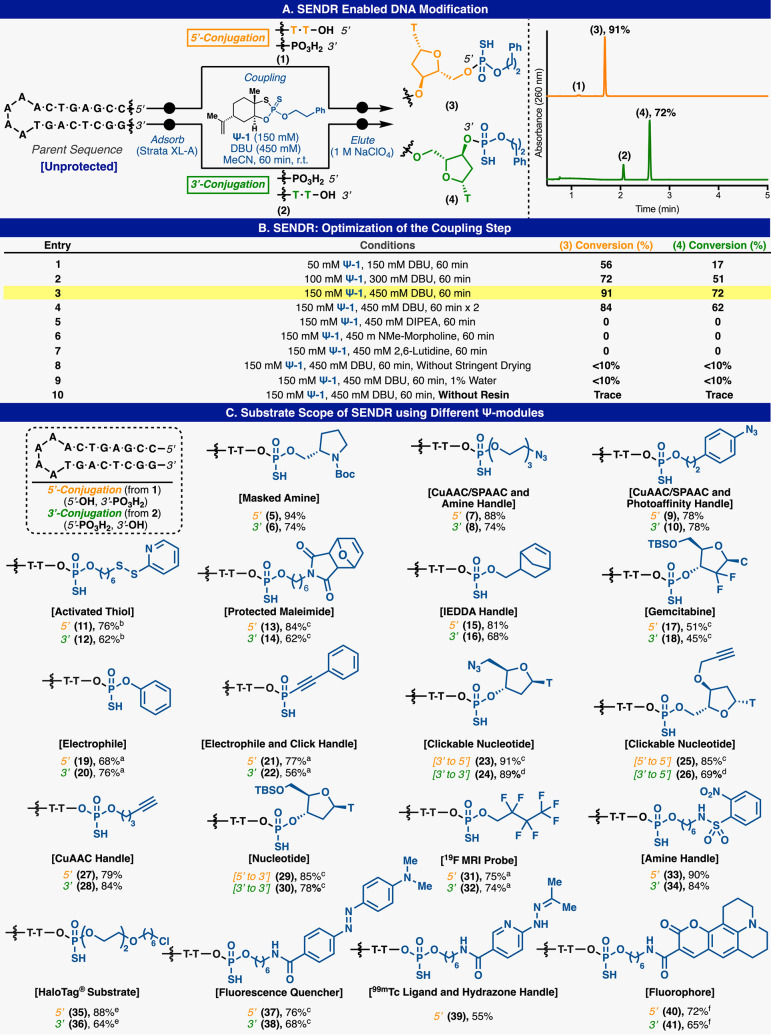

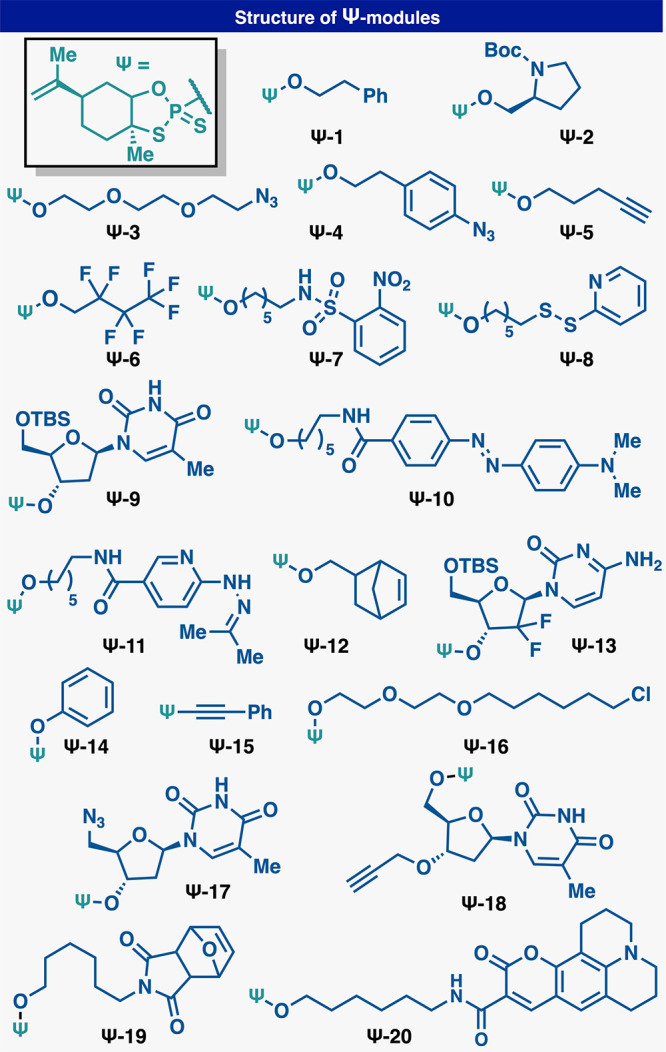

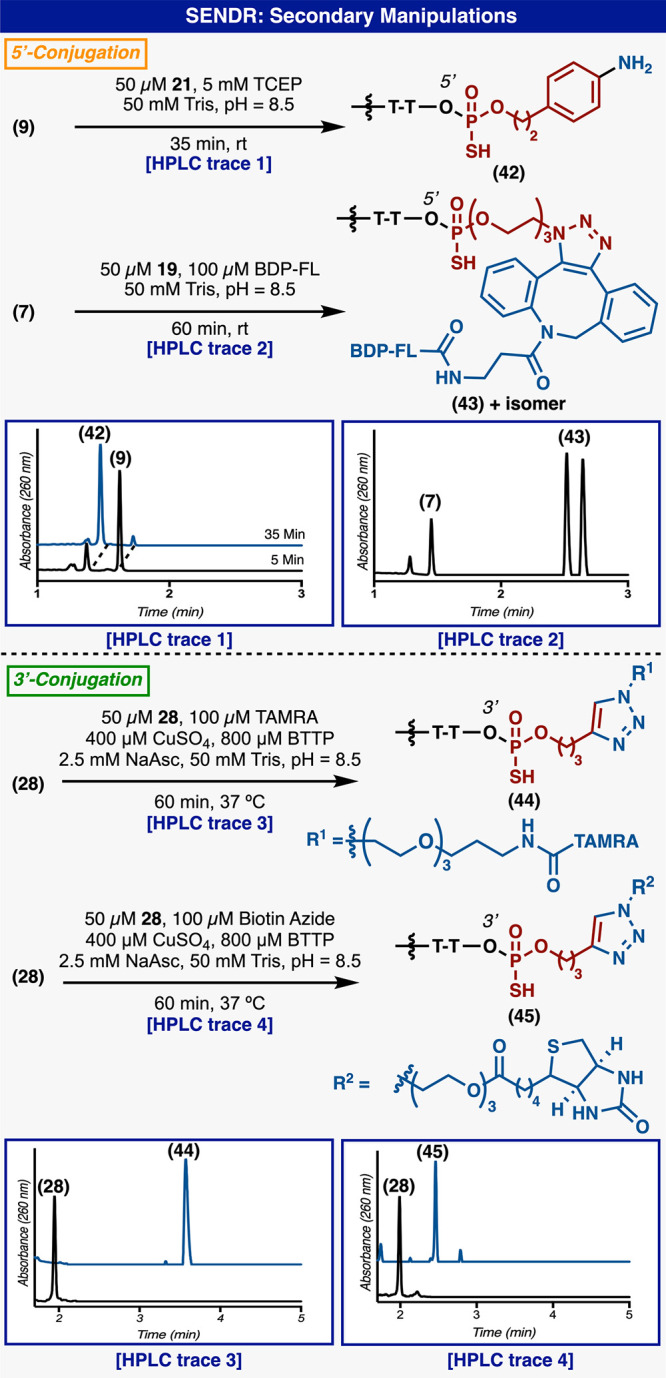

With this design in mind, a variety of Ψ-loaded reagents (Ψ-modules, Figure 2) were prepared to explore site-specific labeling of native DNA. Model DNA (1) and (2) each contains single modifiable terminal hydroxyl groups at the 5′ and 3′ positions, respectively, with the other terminal hydroxyl group capped with a phosphate group (Figure 3A). Model DNA could readily undergo RASS (Strata XL-A resin, Phenomenex), but initial attempts to apply Ψ-conjugation proved difficult, furnishing only low yields of the modified product. On the basis of significant amounts of hydrolyzed Ψ-derivatives in the crude product mixture, we postulated that this protocol (3× washes with dry acetonitrile) was not sufficient to fully dry the DNA-bound resin. Residual water would subsequently quench the Ψ-modules upon addition of DBU.34 Optimization of the washing protocol to use reagent-grade DMA, then THF, and finally drying under vacuum rectified this issue. With this revised protocol in hand, promising initial reactivity was observed (Figure 3B, entry 1). By modulating DBU stoichiometry, concentration, and reaction time, general conditions were identified (Figure 3B, entry 3) to produce singly labeled products (3) and (4) with good conversion (determined by total UV quantification at 260 nm) at both the 5′ and 3′ position, with no observable byproducts. The labeling position was confirmed by MS fragmentation (see Supporting Information). Also, DNA without any phosphate “blocking” groups could be selectively modified at the more reactive 5′ terminus with a single Ψ-module by reducing Ψ-module concentration, albeit at reduced yields (53%) (see Supporting Information). Additionally, the same DNA starting material (without terminal phosphates) could be dual labeled at both termini with two Ψ-modules under standard conditions (73%) (see Supporting Information). DNA lacking a terminal phosphate could be readily phosphorylated by T4 polynucleotide kinase (T4PNK) (30 min) and directly loaded onto the support for subsequent SENDR protocol (see Supporting Information). Biochemically phosphorylated substrates were labeled at efficiencies comparable to chemically phosphorylated material (see Supporting Information). The conditions also proved to be sequence independent (see Supporting Information). SENDR provided efficient conjugations to oligonucleotides regardless of the identity of the terminal nucleoside. Also, both “sticky ends” (i.e., overhanging oligonucleotides) and “blunt ends” (i.e., nonoverhanging oligonucleotides) could be modified efficiently. This is important as there exists evidence that DNA retains its secondary structure while adsorbed to the support.37 High Tm DNA hairpins with nonoverhanging terminal alcohols were labeled in higher conversions when thermally denatured while being adsorbed to the support (see Supporting Information). With all of these elements combined, the development of SENDR was complete, and our attention turned to its application. On the basis of previous studies, it was envisioned that a wide array of Ψ-modules derived from alcohol nucleophiles could be prepared as stable (and often crystalline) reagents.33,34 Combined with the present findings, subsequent coupling to DNA sequences would allow for a vast scope. Indeed, a large number of Ψ-modules (Figure 2, Ψ-1−Ψ-20), including multiple click chemistry handles (7–10, and 21–26), protected amines (5, 6, 13, and 14), an activated disulfide (11, 12), an MRI probe (31, 32), a fluorescent quencher (37, 38), a ligand for radiomedicine (39), photoaffinity tag (35, 36), a fluorophore (40, 41), and nucleosides (17, 18, 25, 26, 29 and 30), were prepared (Figure 3D). It is important to note that azide-containing handles typically cannot be incorporated directly in solid phase DNA synthesis by standard phosphoramidite chemistry as the P(III) containing phosphoramidite reactive group generally reduces the azide in a classical Staudinger reaction. Thus, most suppliers conjugate an azide to a preinstalled amine via NHS-ester chemistry postsynthesis. All Ψ-modules produced singly labeled products upon conjugation to DNA in good to excellent conversion at both the 3′ and 5′ hydroxyl groups. DNA recovery was also good (30–80%), given that the upper yield limit after ethanol precipitation is known to be 80–85%.41 Throughout these applications, the general conditions were not modified, with the exception of cases where solubilization of the reagent required slightly elevated temperature (37 to 50 °C). Unfortunately, reagents containing extremely lipophilic substituents, such as cholesterol and oleyl alcohol, provided lower yields (<50%) under these conditions (see Supporting Information). The SENDR-modified oligonucleotides could be further processed via additional conjugation and click manipulations (Figure 4). Thus, DNA-linked azides and alkynes were competent in SPAAC42−44 and CuAAC42,43,45 respectively, and directly provided constructs that were useful without further purification. In addition, DNA-linked azides could be easily transformed into the corresponding amines through the addition of a water-soluble phosphine (TCEP).46 This manipulation could be performed after SENDR as a one-pot procedure in the elution buffer, providing an exceedingly simple route to amine-modified DNA. Similarly, the construction of high-value DNA labeled with 3′ TAMRA or biotin (Figure 5). The 3′ SENDR-modified DNA could be quantitatively transformed with multiple complex azides to furnish DNA conjugates that are sufficiently homogeneous (>80%) for most biochemical experiments without additional purification. Potential adverse effects on Cu(I) chemistry that could arise, due to coordination to the phosphorothioate moiety,47 were not observed, and CuAAC could be readily employed, allowing for, in principle, near-infinite diversification.

Figure 2.

Ψ-modules synthesized for this study.

Figure 3.

P(V) based DNA modification. (A) SENDR enabled DNA modification. (B) Optimization of the coupling step. (C) Substrate scope. Conversions based on HPLC integration of a total absorbance signal at 260 nm. Unless otherwise noted, standard reaction conditions were applied; Ψ-module (150 mM), DBU (450 mM), in dry MeCN (250 μL), 60 min, r.t. while adsorbed to Strata XL-A. a75 mM PSI and 225 mM DBU, b45 °C,c37 °C. d200 mM PSI at 50 °C. e300 mM PSI at 37 °C. DNA loading (adsorption step) performed in PBS. Resin washed with DMA (×2) and THF (×3). Resin dried under a vacuum 2 h. Elution was performed using elution buffer 1 M NaClO4, 40 mM Tris pH 8.5, 20% MeOH. fIn-situ protocol (see Supporting Information for details).

Figure 4.

Downstream synthetic manipulations of SENDR-derived DNA-small molecule hybrids (ligated at 3′ or 5′).

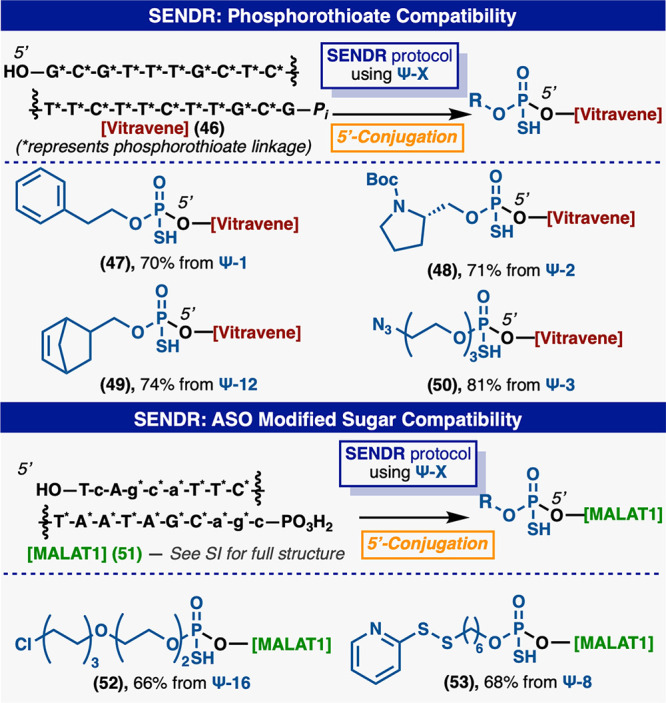

Figure 5.

(Top) SENDR compatibility with PS DNA. (Bottom) SENDR compatibility with larger structured oligomers. Standard reaction conditions were applied; Ψ-module (150 mM), DBU (450 mM), in dry MeCN (250 μL), 60 min, 37 °C while adsorbed to Strata XL-A.

SENDR: Complex Settings

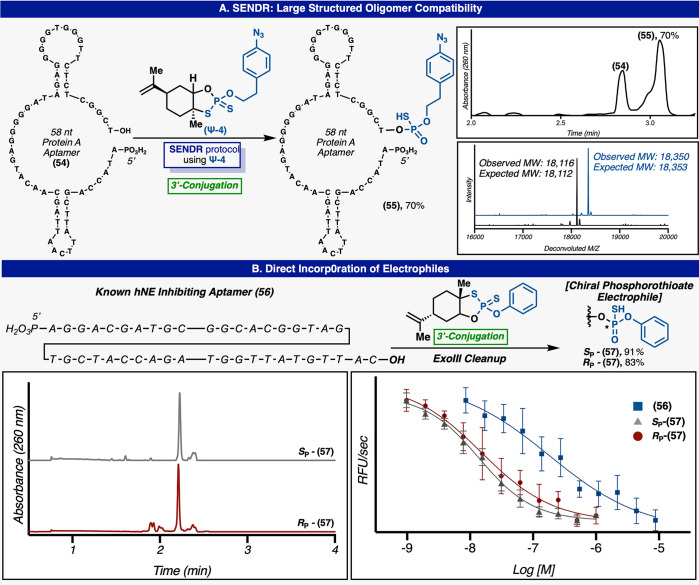

SENDR could also be adapted for the efficient modification of phosphorothioate antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) (Figure 5). The 3′ phosphorylated version of Vitravene, an FDA-approved ASO for the treatment of cytomegalovirus retinitis (CMV),48,49 was efficiently ligated with a number of Ψ-modules with no change to the general protocol. The 3′ phosphorylated version of MALAT1, a published ASO50 with multiple modified sugars and bases, and containing PS linkages, could be readily modified with multiple Ψ-modules. This result exemplifies the opportunity for the late-stage modification of ASO pools with target-engaging small molecules or peptides. Previously, such handles would have required a de novo chemical synthesis for each new compound. A large (58 nt) “protein A” aptamer51 (54) which exhibits significant secondary structure could be modified at the 3′ hydroxyl in 70% conversion (Figure 6). Additionally, an aptamer52 to human neutrophil elastase (hNE) (56) could be modified at the 3′ position with a phosphorothioate electrophile and was labeled using both enantiomers of (Ψ-14), in similar conversions. The unlabeled aptamers were selectively digested using ExoIII53 leaving high purity aptamers (Sp-(57)) and (Rp-(57)). The addition of the phenol (Figure 6) electrophile (Sp-(57)) and (Rp-(57)) conferred a 10-fold increase in potency (Ic50 of 15 and 17 nM respectively) when compared to parent aptamer (63) (Ic50 of 140 nM) in a fluorescence-based hNE inhibition assay.54 Also small molecules containing the same electrophiles were inactive in this screen (see Supporting Information). This example further demonstrates the sequence and structure independence of the SENDR platform. It could prove useful in the modification of entire SELEX55,56 pools with libraries of reactive warheads or target engaging moieties for the facile creation of DNA–small molecule chimeric inhibitors.

Figure 6.

SENDR aptamer modification. (A) Standard reaction conditions were applied; Ψ-module (150 mM), DBU (450 mM), in dry MeCN (250 μL), 60 min, r.t. while adsorbed to Strata XL-A. (B) Direct incorporation of electrophiles into aptamers and their inhibition of protein targets. The reaction conditions that were applied: Ψ-module (150 mM), DBU (450 mM), in dry MeCN (250 μL), 60 min, 37 °C, while adsorbed to Strata XL-A.

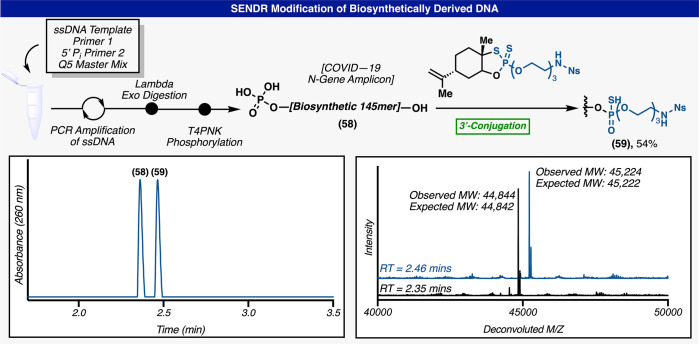

SENDR could also be used to directly modify large strands of biosynthetically produced DNA (Figure 7). A portion of the COVID-19 N-gene (ss-DNA) was amplified by PCR using one primer with a 5′ phosphorylation and one primer without this modification. The resulting amplicon could be readily converted into ssDNA by the selective digestion of the 5′ phosphorylated strand using Lambda exonuclease.57 The resulting ssDNA could be phosphorylated at the 5′ hydroxyl by T4 polynucleotide kinase. This reaction mixture could be directly loaded onto the support and the 3′ hydroxyl modified in good yields (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

SENDR on biosynthetically derived DNA. Scheme representing the biosynthetic steps to produce the COVID-19 N gene amplicon (59). HPLC chromatogram of the SENDR reaction. Deconvoluted mass spectrum of the starting material peak and the product peak.

SENDR: DNA–Protein Conjugates

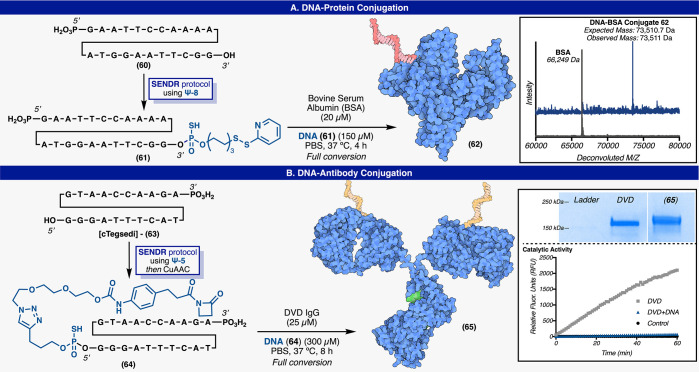

Another utility of SENDR was also demonstrated in the formation of DNA–protein conjugates, which are becoming increasingly valuable in the production of long-acting and/or targeted oligonucleotide drugs.58−61 An oligonucleotide was modified by SENDR (using Ψ-8) with an activated disulfide group resulting in (61) (Figure 8A). This construct could be used directly, without purification in a disulfide forming reaction with bovine serum albumin (BSA). The reaction cleanly furnished the DNA–BSA conjugate (62), and ESI-TOF analysis of the crude reaction mixture indicated that no unmodified BSA remained in solution.62,63 Conjugation to serum albumin is a valuable half-life increasing strategy for quickly cleared peptide and small protein drugs and could in principle be applied to next-generation ASOs.64−68

Figure 8.

SENDR enabled DNA–protein conjugation. (A) DNA–BSA conjugation (ESI-TOF mass spectra of starting material and product). (B) cTegsedi–DVD conjugation (SDS PAGE and catalytic methodol fluorescence assay including control experiments). SENDR: DNA–protein conjugates.

SENDR was also used to create a DNA construct that could be used in site-specific antibody conjugations (Figure 8B). The complementary cDNA sequence of FDA-approved ASO Tegsedi69−71 (cTegsedi) was modified with an alkyne handle. In turn, this alkyne was ligated to a reactive beta-lactam containing moiety via CuAAC. The beta lactam containing oligonucleotide (64) was competent in the site-specific labeling of an engineered lysine on the heavy chain of a dual variable domain (DVD) IgG that has been pioneered for use in antibody drug conjugates (ADCs) by the Barbas and Rader laboratories.72−75 This system was derived from the antihapten mAb h38C2 and is especially reactive toward beta lactam haptens. The reactive lysine residue also catalyzes a retro aldol reaction with methodol, which results in increased fluorescence of the aldehyde product.72−75 The modified site on the DVD was confirmed to be the catalytic lysine via methodol florescence assay—after conjugation, signal from the florescent aldehyde was not detected (Figure 8B).72−75 These DVDs have shown promise as flexible platforms for the production of antibody drug conjugates, as they can be produced by typical recombinant methods, and drug molecules can be added at a known stoichiometry, to a known position, through a stable amide linkage.72−75 Labeling the DVD with cTegsedi created, in effect, an ASO delivery system that could protect, target, and deliver Tegsedi to the cell of interest. This process may be useful in the creation of many antibody–ASO conjugates that could provide targeted ASO therapies. The above two examples enabled by SENDR are striking due to the ease and efficiency with which these complex conjugates could be prepared, along with the near-infinite flexibility in design.

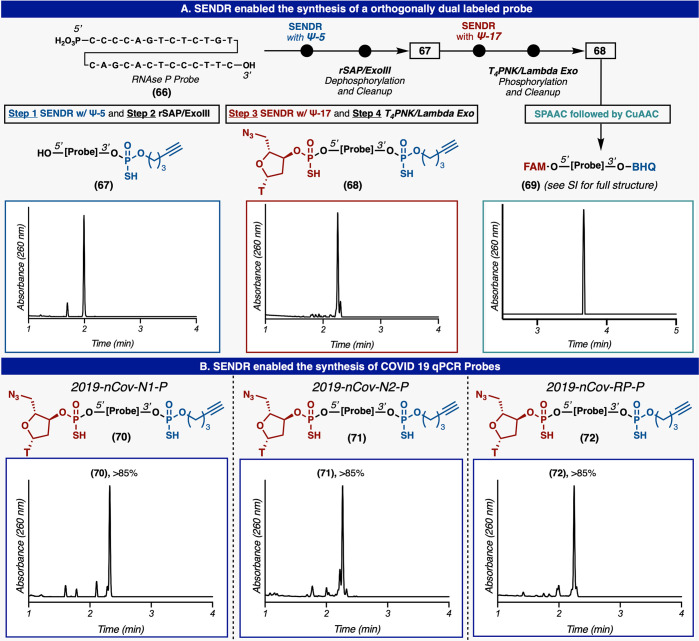

SENDR: Dual Labeled Probes

Although many DNA-based technologies only require a single probe, the true power of hybridization probes is realized in dual labeled form.1 The canonical dual labeled DNA probe has a fluorophore label on one terminus and a fluorescence quencher at the other (Figure 9A).1 Fluorescence of the probe is quenched when the two components are in close proximity. Molecular beacons (MBs),15 for example, form a stem loop system that brings the termini labels into close proximity when the target is not present (Figure 1A). Upon target engagement, the MB adopts an extended conformation, which moves the two labels out of FRET range and results in a fluorescence signal.15 Another ubiquitous example of dual labeled probes is the TaqMan qPCR probe.6−11 These probes are also typically constructed with a fluorophore and a quencher at the termini.6−11 These probes hybridize to a diagnostic sequence of interest and upon PCR elongation by Taq polymerase, the probe is cleaved (by the intrinsic exonuclease activity of Taq), and increased fluorescence is read out (Figure 1A).6−11 Although TaqMan PCR is widely considered to be the state-of-the-art in real-time PCR methods, practitioners are reliant on vendors for custom synthesis of probes with proprietary linking technologies. This synthesis must be done for each individual target and can prove to be prohibitively expensive. Indeed, the less sensitive method of SYBR Green-based qPCR, which relies on increased fluorescence of an intercalating dye during polymerization, is gaining in popularity because of the immense cost of buying custom TaqMan PCR probes for every experiment. SENDR, when used in concert with ubiquitous biochemical techniques, presents a unique opportunity for biochemical researchers to produce dual labeled probes for their own custom applications (Figure 9A). Synthesis of these probes proceeds through a multistage process. In the event, a typical synthetic oligonucleotide containing a 5′ phosphate and a 3′ hydroxyl group is ligated with an alkyne group by SENDR (Figure 9). Next, this modified oligomer is quantitatively dephosphorylated by recombinant shrimp alkaline phosphatase (rSAP)76 unmasking the 5′ hydroxyl group, while the unmodified DNA is selectively degraded by ExoIII53 in one pot. This oligomer is then subjected to a second SENDR modification at the 5′ terminus, providing the dual labeled probe. Similarly, remaining unlabeled DNA is selectively degraded by a mixture of lambda exonuclease and T4PNK in one pot. The T4PNK phosphorylates the remaining unlabeled 5′ hydroxyl DNA which is then recognized and degraded by lambda exonuclease. These resulting probes are highly pure without the need for HPLC purification. The position of each label on the dual labeled probe was confirmed by MS fragmentation (see Supporting Information). This dual-labeled parent probe (68) is now primed for subsequent SPAAC/CuAAC reactions with any fluorophore/quencher pair desired to furnish the qPCR-competent probe. These reactions with FAM-DBCO and BHQ1-azide proceed quantitatively, resulting in the qPCR competent construct (69). The utility of in-house probe production was demonstrated by the facile and expedient production of dual labeled probes for COVID-19 diagnostics (Figure 9B). The native sequences for the panel of RT-PCR probes for COVID-19 diagnostics 66 and 67 (as defined by HHS 24 Jan 2020) were transformed in parallel (∼48 h) into dual labeled probes through the above sequences in good overall conversions. Although this class of probes are commercially available, we have demonstrated an alternate paradigm for their synthesis, and we believe this could enable the construction of probes beyond those that are currently offered by vendors.

Figure 9.

Creation of dual labeled DNA probes. (A) The synthesis of a TaqMan probe for RNaseP. (B) Synthesis of the COVID 19 qPCR panel of probes.

A Simple SENDR Kit and Future Outlook

From a pragmatic standpoint, a simple kit-format would be of use to the community. Toward that end, a “SENDR kit” was created from readily available consumables. The SENDR process is simple and robust enough to be miniaturized and performed in a cartridge/flow set up, and all reagents employed are shelf-stable indefinitely. Gratifyingly, when performed in a cartridge, the process proved simpler and faster than the previously employed microcentrifuge tubes. Also, the handling procedures were greatly simplified and could be performed by any researcher with basic micropipetting skills. Importantly, reaction efficiency was identical to reactions performed in microcentrifuge tubes (see Supporting Information). Using this kit, a researcher could customize synthetic or biochemically derived DNA, in-house, with a suite of commercialized reagents. We believe that SENDR kits will expand the toolbox and allow researchers to pursue experimental designs that were previously out of reach.

Although SENDR will not displace the need for chemical oligonucleotide synthesis, we envision that this complementary approach will democratize site-specific DNA modifications. Although the chemical diversity of the developed SENDR compatible modules is yet to exceed the commercially available phosphoramidites (which have had >40 years of development), it does not require de novo synthesis (and specialized equipment) and benefits from the intrinsic advantages of a late-stage incorporation. With the acknowledgment that enzymatic means of site-selective functionalization are powerful, SENDR is uniquely versatile and programmable using easily accessible reagents. As more modules are developed, one could imagine an unlimited diversity being incorporated. Regarding limitations, highly lipophilic groups are challenging to employ, groups sensitive to DBU might be problematic, and at this point are limited to terminal modifications. More broadly, the modular nature of the process could permit a more medicinal chemistry mindset into the derivatization of complex DNA-based conjugates. Although some may interject that SENDR-based modification of DNA lies outside the skill set of the general molecular biology practitioner, the robust chemistry should prove simple enough for any practitioner with basic liquid handling skills. This initial disclosure demonstrates conjugations that are compatible with simple organic molecules, proteins, aptamers, and ASOs. Numerous extensions such as applications to carbohydrate conjugation, and multiplexed high throughput arrays, could be anticipated.

Acknowledgments

Financial support for this work was from NIH (GM-132787 for P.E.D, GM-118176 P.S.B and GM-136286 for D.W.W.). The authors thank Christoph Rader and Junpeng Qi for graciously providing DVD IgG. D.T.F. was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Grant No. UL1 TR002551 and linked award TL1 TR002551. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. All nonphotorealistic biomolecular illustrations were created with Goodsell’s Illustrate.77 Authors are grateful to Dr. Dee-Hua Huang and Dr. Laura Pasternack (Scripps Research) for assistance with nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acscentsci.0c00680.

Materials and methods, DNA starting materials synthesis and characterization of PSI modules, NMR spectra, secondary manipulations of DNA conjugates, enzymatic phosphorylation and PCR experiments, and analysis of DNA conjugates (PDF)

Author Contributions

⊥ D.T.F. and K.W.K. contributed equally to this work.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Kolpashchikov D. M. Evolution of Hybridization Probes to DNA Machines and Robots. Acc. Chem. Res. 2019, 52 (7), 1949–1956. 10.1021/acs.accounts.9b00098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieves D. J.; Gaus K.; Baker M. A. B. DNA-Based Super-Resolution Microscopy: DNA-PAINT. Genes 2018, 9 (12), 621. 10.3390/genes9120621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jungmann R.; Avendano M. S.; Woehrstein J. B.; Dai M.; Shih W. M.; Yin P. Multiplexed 3D cellular super-resolution imaging with DNA-PAINT and Exchange-PAINT. Nat. Methods 2014, 11 (3), 313–318. 10.1038/nmeth.2835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jungmann R.; Steinhauer C.; Scheible M.; Kuzyk A.; Tinnefeld P.; Simmel F. C. Single-molecule kinetics and super-resolution microscopy by fluorescence imaging of transient binding on DNA origami. Nano Lett. 2010, 10 (11), 4756–4761. 10.1021/nl103427w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnitzbauer J.; Strauss M. T.; Schlichthaerle T.; Schueder F.; Jungmann R. Super-resolution microscopy with DNA-PAINT. Nat. Protoc. 2017, 12 (6), 1198–1228. 10.1038/nprot.2017.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland P. M.; Abramson R. D.; Watson R.; Gelfand D. H. Detection of specific polymerase chain reaction product by utilizing the 5′----3′ exonuclease activity of Thermus aquaticus DNA polymerase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1991, 88 (16), 7276–7280. 10.1073/pnas.88.16.7276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro E.; Serrano-Heras G.; Castano M. J.; Solera J. Real-time PCR detection chemistry. Clin. Chim. Acta 2015, 439, 231–250. 10.1016/j.cca.2014.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espy M. J.; Uhl J. R.; Sloan L. M.; Buckwalter S. P.; Jones M. F.; Vetter E. A.; Yao J. D. C.; Wengenack N. L.; Rosenblatt J. E.; Cockerill F. R.; Smith T. F. Real-Time PCR in Clinical Microbiology: Applications for Routine Laboratory Testing. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2006, 19 (1), 165–256. 10.1128/CMR.19.1.165-256.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer G.; Muller J.; Lunse C. E. RNA diagnostics: real-time RT-PCR strategies and promising novel target RNAs. Wiley Interdiscip Rev. RNA 2011, 2 (1), 32–41. 10.1002/wrna.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardullo R. A.; Agrawal S.; Flores C.; Zamecnik P. C.; Wolf D. E. Detection of nucleic acid hybridization by nonradiative fluorescence resonance energy transfer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1988, 85 (23), 8790–8794. 10.1073/pnas.85.23.8790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison L. E.; Halder T. C.; Stols L. M. Solution-phase detection of polynucleotides using interacting fluorescent labels and competitive hybridization. Anal. Biochem. 1989, 183 (2), 231–244. 10.1016/0003-2697(89)90473-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall B. D.; Spiegelman S. Sequence complementarity of T2-DNA and T2-specific RNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1961, 47, 137–163. 10.1073/pnas.47.2.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolton E. T.; McCarthy B. J. A general method for the isolation of RNA complementary to DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1962, 48, 1390–1397. 10.1073/pnas.48.8.1390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolpashchikov D. M. An elegant biosensor molecular beacon probe: challenges and recent solutions. Scientifica 2012, 2012, 928783. 10.6064/2012/928783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyagi S.; Kramer F. R. Molecular beacons: probes that fluoresce upon hybridization. Nat. Biotechnol. 1996, 14 (3), 303–308. 10.1038/nbt0396-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southern E. M. Detection of specific sequences among DNA fragments separated by gel electrophoresis. J. Mol. Biol. 1975, 98 (3), 503–517. 10.1016/S0022-2836(75)80083-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kevil C. G.; Walsh L.; Laroux F. S.; Kalogeris T.; Grisham M. B.; Alexander J. S. An improved, rapid Northern protocol. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1997, 238 (2), 277–279. 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller G. H.; Cumming C. U.; Huang D.-P.; Manak M. M.; Ting R. A chemical method for introducing haptens onto DNA probes. Anal. Biochem. 1988, 170 (2), 441–450. 10.1016/0003-2697(88)90656-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto H.; Traincard F.; Vo-Quang T.; Ternynck T.; Guesdon J.-L.; Avrameas S. 5-Bromodeoxyuridine in vivo labelling of M13 DNA, and its use as a non-radioactive probe for hybridization experiments. Mol. Cell. Probes 1987, 1 (1), 109–120. 10.1016/0890-8508(87)90011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tasara T.; Angerer B.; Damond M.; Winter H.; Dorhofer S.; Hubscher U.; Amacker M. Incorporation of reporter molecule-labeled nucleotides by DNA polymerases. II. High-density labeling of natural DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003, 31 (10), 2636–2646. 10.1093/nar/gkg371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul N.; Yee J. PCR incorporation of modified dNTPs: the substrate properties of biotinylated dNTPs. BioTechniques 2010, 48 (4), 333–334. 10.2144/000113405. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mix K. A.; Aronoff M. R.; Raines R. T. Diazo Compounds: Versatile Tools for Chemical Biology. ACS Chem. Biol. 2016, 11 (12), 3233–3244. 10.1021/acschembio.6b00810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motea E. A.; Berdis A. J. Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase: the story of a misguided DNA polymerase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Proteins Proteomics 2010, 1804 (5), 1151–1166. 10.1016/j.bbapap.2009.06.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoang T. M.; Kent T.; Pomerantz R. T., Modification of 3′ Terminal Ends of DNA and RNA Using DNA Polymerase theta Terminal Transferase Activity. Bio Protocol 2017, 7 ( (12), ), 10.21769/BioProtoc.2330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deen J.; Vranken C.; Leen V.; Neely R. K.; Janssen K. P. F.; Hofkens J. Methyltransferase-Directed Labeling of Biomolecules and its Applications. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56 (19), 5182–5200. 10.1002/anie.201608625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner A. F.; Jackson K. M.; Boyle M. M.; Buss J. A.; Potapov V.; Gehring A. M.; Zatopek K. M.; Correa I. R. Jr.; Ong J. L.; Jack W. E. Therminator DNA Polymerase: Modified Nucleotides and Unnatural Substrates. Front Mol. Biosci. 2019, 6, 28. 10.3389/fmolb.2019.00028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samanta B.; Horning D. P.; Joyce G. F. 3′-End labeling of nucleic acids by a polymerase ribozyme. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46 (17), e103 10.1093/nar/gky513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ralph R. K.; Young R. J.; Khorana H. G. The Labelling of Phosphomonoester End Groups in Amino Acid Acceptor Ribonucleic Acids and its use in the Determination of Nucleotide Sequences. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1962, 84 (8), 1490–1491. 10.1021/ja00867a030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chu B. C.; Wahl G. M.; Orgel L. E. Derivatization of unprotected polynucleotides. Nucleic Acids Res. 1983, 11 (18), 6513–6529. 10.1093/nar/11.18.6513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu B. C.; Orgel L. E. Ligation of oligonucleotides to nucleic acids or proteins via disulfide bonds. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988, 16 (9), 3671–3691. 10.1093/nar/16.9.3671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh S. S.; Kao P. M.; Kwoh D. Y. Synthesis of 5′-oligonucleotide hydrazide derivatives and their use in preparation of enzyme-nucleic acid hybridization probes. Anal. Biochem. 1989, 178 (1), 43–51. 10.1016/0003-2697(89)90354-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh S. S.; Kao P. M.; McCue A. W.; Chappelle H. L. Use of maleimide-thiol coupling chemistry for efficient syntheses of oligonucleotide-enzyme conjugate hybridization probes. Bioconjugate Chem. 1990, 1 (1), 71–76. 10.1021/bc00001a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu D.; Rivas-Bascon N.; Padial N. M.; Knouse K. W.; Zheng B.; Vantourout J. C.; Schmidt M. A.; Eastgate M. D.; Baran P. S. Enantiodivergent Formation of C-P Bonds: Synthesis of P-Chiral Phosphines and Methylphosphonate Oligonucleotides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142 (12), 5785–5792. 10.1021/jacs.9b13898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knouse K. W.; deGruyter J. N.; Schmidt M. A.; Zheng B.; Vantourout J. C.; Kingston C.; Mercer S. E.; McDonald I. M.; Olson R. E.; Zhu Y.; Hang C.; Zhu J.; Yuan C.; Wang Q.; Park P.; Eastgate M. D.; Baran P. S. Unlocking P(V): Reagents for chiral phosphorothioate synthesis. Science 2018, 361 (6408), 1234–1238. 10.1126/science.aau3369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flood D. T.; Kingston C.; Vantourout J. C.; Dawson P. E.; Baran P. S. DNA Encoded Libraries: A Visitor’s Guide. Isr. J. Chem. 2020, 60, 268. 10.1002/ijch.201900133. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arcella A.; Portella G.; Collepardo-Guevara R.; Chakraborty D.; Wales D. J.; Orozco M. Structure and properties of DNA in apolar solvents. J. Phys. Chem. B 2014, 118 (29), 8540–8548. 10.1021/jp503816r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flood D. T.; Asai S.; Zhang X.; Wang J.; Yoon L.; Adams Z. C.; Dillingham B. C.; Sanchez B. B.; Vantourout J. C.; Flanagan M. E.; Piotrowski D. W.; Richardson P.; Green S. A.; Shenvi R. A.; Chen J. S.; Baran P. S.; Dawson P. E. Expanding Reactivity in DNA-Encoded Library Synthesis via Reversible Binding of DNA to an Inert Quaternary Ammonium Support. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141 (25), 9998–10006. 10.1021/jacs.9b03774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flood D. T.; Yan N. L.; Dawson P. E. Post-Translational Backbone Engineering through Selenomethionine-Mediated Incorporation of Freidinger Lactams. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57 (28), 8697–8701. 10.1002/anie.201804885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flood D. T.; Zhang X.; Fu X.; Zhao Z.; Asai S.; Sanchez B. B.; Sturgell E. J.; Vantourout J. C.; Richardson P.; Flanagan M. E.; Piotrowski D. W.; Kolmel D. K.; Wan J.; Tsai M. H.; Chen J. S.; Baran P. S.; Dawson P. E. RASS-Enabled S/P-C and S-N Bond Formation for DEL Synthesis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 7377. 10.1002/anie.201915493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cistrone P. A.; Dawson P. E. Click-Based Libraries of SFTI-1 Peptides: New Methods Using Reversed-Phase Silica. ACS Comb. Sci. 2016, 18 (3), 139–143. 10.1021/acscombsci.5b00195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.; Chen S.; Liu N.; Ma L.; Wang T.; Veedu R. N.; Li T.; Zhang F.; Zhou H.; Cheng X.; Jing X. A systematic investigation of key factors of nucleic acid precipitation toward optimized DNA/RNA isolation. BioTechniques 2020, 68, 191. 10.2144/btn-2019-0109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sletten E. M.; Bertozzi C. R. Bioorthogonal chemistry: fishing for selectivity in a sea of functionality. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48 (38), 6974–6998. 10.1002/anie.200900942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devaraj N. K. The Future of Bioorthogonal Chemistry. ACS Cent. Sci. 2018, 4 (8), 952–959. 10.1021/acscentsci.8b00251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agard N. J.; Prescher J. A.; Bertozzi C. R. A strain-promoted [3 + 2] azide-alkyne cycloaddition for covalent modification of biomolecules in living systems. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126 (46), 15046–15047. 10.1021/ja044996f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rostovtsev V. V.; Green L. G.; Fokin V. V.; Sharpless K. B. A Stepwise Huisgen Cycloaddition Process: Copper(I)-Catalyzed Regioselective “Ligation” of Azides and Terminal Alkynes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2002, 41 (14), 2596–2599. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staudinger H.; Meyer J. Über neue organische Phosphorverbindungen III. Phosphinmethylenderivate und Phosphinimine. Helv. Chim. Acta 1919, 2 (1), 635–646. 10.1002/hlca.19190020164. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Honcharenko M.; Honcharenko D.; Stromberg R. Copper-Catalyzed Huisgen 1,3-Dipolar Cycloaddition Tailored for Phosphorothioate Oligonucleotides. Curr. Protoc Nucleic Acid Chem. 2020, 80 (1), e102 10.1002/cpnc.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry C. M.; Balfour J. A. Fomivirsen. Drugs 1999, 57 (3), 375–80. discussion 381 10.2165/00003495-199957030-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein C. A.; Castanotto D. FDA-Approved Oligonucleotide Therapies in 2017. Mol. Ther. 2017, 25 (5), 1069–1075. 10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ammala C.; Drury W. J. 3rd; Knerr L.; Ahlstedt I.; Stillemark-Billton P.; Wennberg-Huldt C.; Andersson E. M.; Valeur E.; Jansson-Lofmark R.; Janzen D.; Sundstrom L.; Meuller J.; Claesson J.; Andersson P.; Johansson C.; Lee R. G.; Prakash T. P.; Seth P. P.; Monia B. P.; Andersson S. Targeted delivery of antisense oligonucleotides to pancreatic beta-cells. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4 (10), eaat3386 10.1126/sciadv.aat3386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoltenburg R.; Krafcikova P.; Viglasky V.; Strehlitz B. G-quadruplex aptamer targeting Protein A and its capability to detect Staphylococcus aureus demonstrated by ELONA. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 33812. 10.1038/srep33812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlton J.; Kirschenheuter G. P.; Smith D. Highly potent irreversible inhibitors of neutrophil elastase generated by selection from a randomized DNA-valine phosphonate library. Biochemistry 1997, 36 (10), 3018–3026. 10.1021/bi962669h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putney S. D.; Benkovic S. J.; Schimmel P. R. A DNA fragment with an alpha-phosphorothioate nucleotide at one end is asymmetrically blocked from digestion by exonuclease III and can be replicated in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1981, 78 (12), 7350–7354. 10.1073/pnas.78.12.7350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Q.; Woehl J. L.; Kitamura S.; Santos-Martins D.; Smedley C. J.; Li G.; Forli S.; Moses J. E.; Wolan D. W.; Sharpless K. B. SuFEx-enabled, agnostic discovery of covalent inhibitors of human neutrophil elastase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2019, 116 (38), 18808–18814. 10.1073/pnas.1909972116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuerk C.; Gold L. Systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment: RNA ligands to bacteriophage T4 DNA polymerase. Science 1990, 249 (4968), 505–510. 10.1126/science.2200121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai C.; Xie Z.; Grotewold E. SELEX (Systematic Evolution of Ligands by EXponential Enrichment), as a powerful tool for deciphering the protein-DNA interaction space. Methods Mol. Biol. 2011, 754, 249–258. 10.1007/978-1-61779-154-3_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avci-Adali M.; Paul A.; Wilhelm N.; Ziemer G.; Wendel H. P. Upgrading SELEX technology by using lambda exonuclease digestion for single-stranded DNA generation. Molecules 2010, 15 (1), 1–11. 10.3390/molecules15010001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Synakewicz M.; Bauer D.; Rief M.; Itzhaki L. S. Bioorthogonal protein-DNA conjugation methods for force spectroscopy. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9 (1), 13820. 10.1038/s41598-019-49843-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardinelli G.; Hogberg B. Entirely enzymatic nanofabrication of DNA-protein conjugates. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45 (18), e160 10.1093/nar/gkx707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan X.; Zhang H.; Wang Z.; Peng H.; Tao J.; Li X. F.; Chris Le X. Quantitative synthesis of protein-DNA conjugates with 1:1 stoichiometry. Chem. Commun. (Cambridge, U. K.) 2018, 54 (54), 7491–7494. 10.1039/C8CC03268H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niemeyer C. M. Semisynthetic DNA-protein conjugates for biosensing and nanofabrication. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010, 49 (7), 1200–1216. 10.1002/anie.200904930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman A. W.; Dien V. T.; Karadeema R. J.; Fischer E. C.; You Y.; Anderson B. A.; Krishnamurthy R.; Chen J. S.; Li L.; Romesberg F. E. Optimization of Replication, Transcription, and Translation in a Semi-Synthetic Organism. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141 (27), 10644–10653. 10.1021/jacs.9b02075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Won Y.; Jeon H.; Pagar A. D.; Patil M. D.; Nadarajan S. P.; Flood D. T.; Dawson P. E.; Yun H. In vivo biosynthesis of tyrosine analogs and their concurrent incorporation into a residue-specific manner for enzyme engineering. Chem. Commun. (Cambridge, U. K.) 2019, 55 (100), 15133–15136. 10.1039/C9CC08503C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie D.; Yao C.; Wang L.; Min W.; Xu J.; Xiao J.; Huang M.; Chen B.; Liu B.; Li X.; Jiang H. An albumin-conjugated peptide exhibits potent anti-HIV activity and long in vivo half-life. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010, 54 (1), 191–196. 10.1128/AAC.00976-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng J.; Zhao C.; Wang L.; Qu L.; Zhu H.; Yang Z.; An G.; Tian H.; Shou C. Development of a novel albumin-based and maleimidopropionic acid-conjugated peptide with prolonged half-life and increased in vivo anti-tumor efficacy. Theranostics 2018, 8 (8), 2094–2106. 10.7150/thno.22069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki K.; Ishihara J.; Ishihara A.; Miura R.; Mansurov A.; Fukunaga K.; Hubbell J. A. Engineered collagen-binding serum albumin as a drug conjugate carrier for cancer therapy. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5 (8), eaaw6081 10.1126/sciadv.aaw6081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byeon H. J.; Min S. Y.; Kim I.; Lee E. S.; Oh K. T.; Shin B. S.; Lee K. C.; Youn Y. S. Human serum albumin-TRAIL conjugate for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Bioconjugate Chem. 2014, 25 (12), 2212–2221. 10.1021/bc500427g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thibaudeau K.; Leger R.; Huang X.; Robitaille M.; Quraishi O.; Soucy C.; Bousquet-Gagnon N.; van Wyk P.; Paradis V.; Castaigne J. P.; Bridon D. Synthesis and evaluation of insulin-human serum albumin conjugates. Bioconjugate Chem. 2005, 16 (4), 1000–1008. 10.1021/bc050102k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gertz M. A.; Scheinberg M.; Waddington-Cruz M.; Heitner S. B.; Karam C.; Drachman B.; Khella S.; Whelan C.; Obici L. Inotersen for the treatment of adults with polyneuropathy caused by hereditary transthyretin-mediated amyloidosis. Expert Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. 2019, 12 (8), 701–711. 10.1080/17512433.2019.1635008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson M. D.; Waddington-Cruz M.; Berk J. L.; Polydefkis M.; Dyck P. J.; Wang A. K.; Plante-Bordeneuve V.; Barroso F. A.; Merlini G.; Obici L.; Scheinberg M.; Brannagan T. H. 3rd; Litchy W. J.; Whelan C.; Drachman B. M.; Adams D.; Heitner S. B.; Conceicao I.; Schmidt H. H.; Vita G.; Campistol J. M.; Gamez J.; Gorevic P. D.; Gane E.; Shah A. M.; Solomon S. D.; Monia B. P.; Hughes S. G.; Kwoh T. J.; McEvoy B. W.; Jung S. W.; Baker B. F.; Ackermann E. J.; Gertz M. A.; Coelho T. Inotersen Treatment for Patients with Hereditary Transthyretin Amyloidosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379 (1), 22–31. 10.1056/NEJMoa1716793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gales L. Tegsedi (Inotersen): An Antisense Oligonucleotide Approved for the Treatment of Adult Patients with Hereditary Transthyretin Amyloidosis. Pharmaceuticals 2019, 12 (2), 78. 10.3390/ph12020078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanna A. R.; Rader C. Engineering Dual Variable Domains for the Generation of Site-Specific Antibody-Drug Conjugates. Methods Mol. Biol. 2019, 2033, 39–52. 10.1007/978-1-4939-9654-4_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanna A. R.; Li X.; Walseng E.; Pedzisa L.; Goydel R. S.; Hymel D.; Burke T. R. Jr.; Roush W. R.; Rader C. Harnessing a catalytic lysine residue for the one-step preparation of homogeneous antibody-drug conjugates. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8 (1), 1112. 10.1038/s41467-017-01257-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rader C.; Turner J. M.; Heine A.; Shabat D.; Sinha S. C.; Wilson I. A.; Lerner R. A.; Barbas C. F. A Humanized Aldolase Antibody for Selective Chemotherapy and Adaptor Immunotherapy. J. Mol. Biol. 2003, 332 (4), 889–899. 10.1016/S0022-2836(03)00992-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner J.; Lerner R. A.; Barbas C. F. 3rd, Efficient aldolase catalytic antibodies that use the enamine mechanism of natural enzymes. Science 1995, 270 (5243), 1797–1800. 10.1126/science.270.5243.1797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millan J. L. Alkaline Phosphatases: Structure, substrate specificity and functional relatedness to other members of a large superfamily of enzymes. Purinergic Signalling 2006, 2 (2), 335–341. 10.1007/s11302-005-5435-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodsell D. S.; Autin L.; Olson A. J. Structure 2019, 27, 1716–1720. 10.1016/j.str.2019.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.