Abstract

Purpose of review

Anticoagulation with vitamin-K antagonists or direct oral anticoagulants is associated with a significant risk of bleeding. There is a major effort underway to develop antithrombotic drugs that have a smaller impact on hemostasis. The plasma contact proteins factor XI (FXI) and factor XII (FXII) have drawn considerable interest because they contribute to thrombosis but have limited roles in hemostasis. Here, we discuss results of preclinical and clinical trials supporting the hypothesis that the contact system contributes to thromboembolic disease.

Recent findings

Numerous compounds targeting FXI or FXII have shown antithrombotic properties in preclinical studies. In phase 2 studies, drugs-targeting FXI or its protease form FXIa compared favorably with standard care for venous thrombosis prophylaxis in patients undergoing knee replacement. While less work has been done with FXII inhibitors, they may be particularly useful for limiting thrombosis in situations where blood comes into contact with artificial surfaces of medical devices.

Summary

Inhibitors of contact activation, and particularly of FXI, are showing promise for prevention of thromboembolic disease. Larger studies are required to establish their efficacy, and to establish that they are safer than current therapy from a bleeding standpoint.

Keywords: anticoagulation, contact activation, factor XI, factor XII

INTRODUCTION

More than 30 million prescriptions for anticoagulants are written annually in the United States for treating or preventing thromboembolic disease [1]. Bleeding is a well recognized common side effect of vitamin-K antagonists such as warfarin [2,3]. Newer direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) targeting the proteases thrombin and factor Xa are replacing warfarin for many indications [2–5,6▪]. DOACs appear safer than warfarin from the standpoint of life-threatening hemorrhage [3,4,6▪], but their use still carries significant risks of major bleeding [5,6▪]. As a result, many patients who could benefit from anticoagulation therapy do not receive it. This reality drives the search for safer drugs. Inhibition of the plasma contact system is emerging as an antithrombotic strategy that could reduce therapy-associated bleeding [6▪,7–9]. Blocking the contact system may also have a role in treating inflammatory processes. Here, we discuss the biology of the contact system, preclinical, and clinical trials of compounds targeting the system, and possible therapeutic applications.

CONTACT ACTIVATION AND BLOOD COAGULATION

The contact system consists of the plasma protease precursors factor XII (FXII), prekallikrein, and factor XI (FXI), and the cofactor high-molecular-weight kininogen [10–13]. These contact factors are synthesized primarily in hepatocytes like other coagulation factors, but do not require vitamin K for posttranslational modifications. FXII, prekallikrein and high-molecular-weight kininogen are also referred to as the kallikrein-kinin system (KKS) [10,14]. In normal health, FXII and prekallikrein reciprocally convert each other to the proteases FXIIa and plasma kallikrein (PKa) [15]. PKa cleaves high-molecular-weight kininogen to liberate the vasoactive peptide bradykinin, which plays a role in setting blood vessel tone and permeability [10,14,16]. The KKS does not appear to contribute significantly to physiologic blood coagulation at an injury site (hemostasis), as congenital deficiencies of FXII, prekallikrein, or high-molecular-weight kininogen are not associated with abnormal bleeding [17].

When blood comes into contact with certain types of biological or artificial ‘surfaces’, reciprocal activation of FXII and prekallikrein is accelerated by a process called contact activation [8,10–12,17]. Polyphosphates [18–21], polynucleic acids [22–25], bacterial components (lipopolysaccharides, teichoic acids, peptidoglycans) [26,27], and misfolded proteins [28] are biological substances that support contact activation. Contact activation also occurs on surfaces of medical devices [29,30] including intravenous catheters [29,31], heart valves [31], and circuits for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) [32], cardiopulmonary bypass [33,34], and renal dialysis [35].

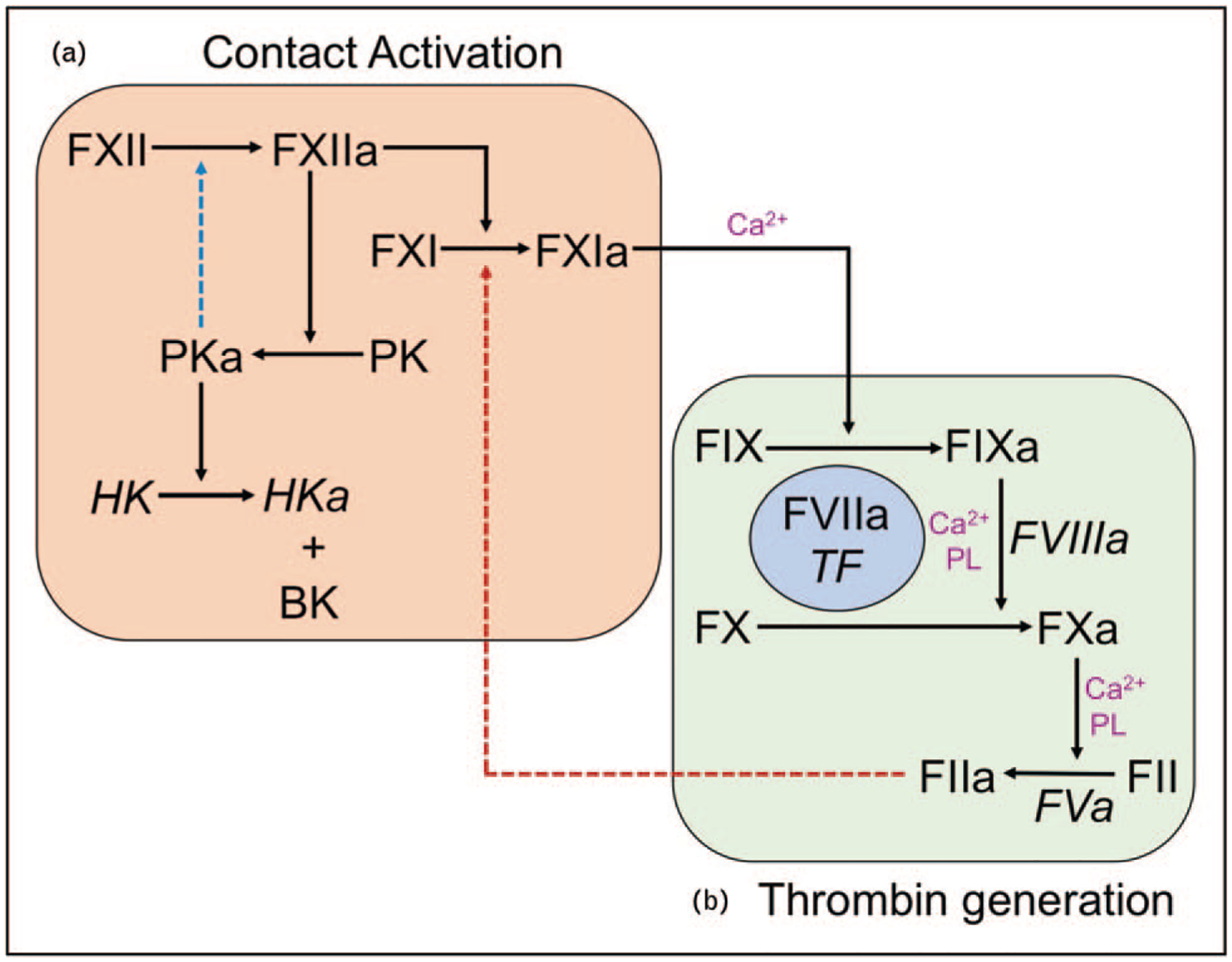

Contact activation (Fig. 1, orange square) is initiated when FXII binds to a surface and undergoes autoactivation to FXIIa [10–14]. FXIIa converts prekallikrein to PKa, which activates more FXII, amplifying the process. High-molecular-weight kininogen facilitates prekallikrein surface-binding. FXIIa then converts FXI to the protease FXIa. This reaction is the major procoagulant step in contact activation, as FXIa is a potent activator of the coagulation protease factor IX (Fig. 1, green square) [36]. The sequential reactions starting with FXII activation and culminating in factor IX activation comprise the intrinsic pathway of coagulation, which initiates clotting in the activated partial thromboplastin time assay used in clinical practice [17].

FIGURE 1.

Contact activation and thrombin generation. (a) Contact activation. Binding of factor XII to a surface initiates its autocatalytic conversion to its activated form factor XIIa. Factor XIIa catalyzes conversion of prekallikrein to plasma kallikrein, which activates additional factor XII (blue dashed arrow) amplifying the contact process. Plasma kallikrein also cleaves high-molecular-weight kininogen to release the vasoactive peptide, bradykinin. In addition to activating prekallikrein, factor XIIa also converts factor XI to factor XIa. (b) Thrombin generation. At a site of injury, thrombin generation is initiated by a complex comprised of factor VIIa and the integral membrane protein tissue factor. This complex activates factor X and factor IX to factor Xa and factor IXa, respectively. Factor IX activates additional factor X in the presence of factor VIIIa. Factor Xa then converts factor II (prothrombin) to factor IIa (thrombin) in a reaction that uses factor Va as a cofactor. In this system, factor XIa generated through contact activation can promote coagulation independently of factor VIIa/tissue factor by activating factor IX. Alternatively, factor XI may be activated independently of factor XII (red dashed arrow) by thrombin. In both parts of the diagram, cofactors for protease reactions are indicated in italics. Some reactions require calcium ions (Ca2+) and/or phosphatidylserine-containing phospholipids.

CONTACT FACTOR DEFICIENCIES AND HEMOSTASIS

Observations of humans and domesticated animals with FXII, prekallikrein, or high-molecular-weight kininogen deficiency clearly indicate that KKS proteins are not required for hemostasis [10–14,17], consistent with the finding that FXIIa inhibitors do not induce bleeding in laboratory animals [34,37,38,39▪]. FXI-deficient patients, on the other hand, can bleed abnormally [40–42]. This may be explained by the observation that FXI is activated by proteases other than FXIIa, such as thrombin (Fig. 1, dashed red line) [41,42]. In humans, abnormal bleeding associated with FXI deficiency is variable and generally milder than in hemophilia A or B (factor VIII or IX deficiency) [40,41]. Indeed, some patients with severe FXI deficiency do not exhibit a bleeding phenotype. Despite the variation, several features of the bleeding disorder caused by FXI deficiency are clear. Hemorrhage occurs primarily with trauma to tissues with high fibrinolytic activity such as the mouth and urinary tract [40–45]. Bleeding from other tissues is less frequent, and procedures such as appendectomy, cholecystectomy and knee arthroplasty have been performed successfully in FXI-deficient patients without factor replacement [17,43,44,46]. Spontaneous bleeding, with the exception of heavy menstrual bleeding [47], is uncommon, and central nervous system and gastrointestinal bleeding do not appear to occur more frequently than in individuals with normal FXI levels. These observations suggest that therapies targeting FXI and FXII will cause less perturbation of hemostasis than current anticoagulants.

CONTACT ACTIVATION AND THROMBOSIS: PRECLINICAL STUDIES

Studies in laboratory animals provide compelling evidence that contact factors, despite their limited roles in hemostasis, contribute to thrombosis. Mice lacking FXI or FXII are remarkably resistant to arterial and venous thrombus formation [15,48–51]. Mice lacking prekallikrein or high-molecular-weight kininogen also are resistant to thrombosis, but to a lesser degree than FXI or FXII-deficient mice [15,52–54]. FXI or FXII inhibition or reduction in rabbits reduces injury-induced arterial and venous thrombosis [55,56]. FXI inhibition with antibodies [57–59] or FXI reduction with antisense oligonucleotides (ASO) [60] reduces thrombus growth in collagen-coated grafts in baboons, with an antithrombotic effect detected when FXI is reduced by as little as 50% [60]. Antibodies inhibiting FXII also reduce thrombus formation in baboons, but to a lesser extent than with FXI inhibition [38]. Antibodies to FXIIa and FXI attenuate thrombosis in ECMO models in rabbits and baboons [37,39▪]. While encouraging, these results should be extrapolated to human disease with caution. Injury-induced thrombosis in animal models may require contributions from contact activation that do not reflect human disorders such as venous thromboembolism (VTE), myocardial infarction (MI), or stroke.

CONTACT ACTIVATION AND THROMBOSIS: EPIDEMIOLOGY

FXI deficiency is prevalent in persons of Ashkenazi Jewish descent, with severe deficiency occurring in one in 450 persons [43,46]. In this population, FXI-deficient individuals have significantly lower risks for VTE and ischemic stroke than those with normal FXI levels [61–63]. The results are supported by data from the general population showing a correlation between plasma FXI concentration and risks for VTE and stroke [62,64–67]. Some studies link higher FXI levels to increased risk of MI [63,68], although severe deficiency may not have as large a protective effect as in VTE and stroke [69].

Associations between FXII and VTE, stroke, or MI have not been established in humans [70–73]. Indeed, one study indicates that individuals with lower FXII levels are more prone to cardiovascular events [74]. Similarly, plasma levels of prekallikrein and high-molecular-weight kininogen do not appear to influence risk for VTE, stroke, or MI [75,76]. However, components of the KKS, and FXII in particular, do contribute to thrombus formation on surfaces of medical devices, such as ECMO, renal dialysis and cardiopulmonary bypass circuits [29–35].

CONTACT ACTIVATION AND INFLAMMATION

Contact activation contributes to innate host-defense processes not directly related to thrombin generation [7–12]. In addition to bradykinin production, contact proteases activate the complement and fibrinolytic systems, activate platelet receptors, and induce cytokine formation. These activities may contribute to systemic inflammatory response syndromes (SIRS) associated with infections, trauma, and other conditions [7–12,27,77,78]. FXI-deficiency or an antibody to FXI that blocks activation by FXIIa (IgG 14E11) blunted inflammation and improved survival in murine sepsis models [79–82]. A humanized version of 14E11 (3G3 or AB023) prevented death in baboons after infusion of heat-inactivated Staphylococcus aureus [83▪▪] by blunting the early cytokine rise and reducing thrombin generation, activation of fibrinolysis, and activation of complement. Similar findings were reported for an FXIIa-inhibiting antibody (5C12 or AB052) [84], supporting the notion that the FXII–FXI axis is a nexus for proinflammatory pathways.

THERAPEUTIC INHIBITION OF CONTACT ACTIVATION TO PREVENT THROMBOSIS

Current anticoagulants inhibit factor Xa or thrombin, or lower levels of the precursors of these enzymes. As these proteases are required for clot formation, therapy aimed at them will perturb hemostasis. This places limits on the situations in which these agents are used, and the intensity of therapy that is applied. It is anticipated that inhibitors of FXI or FXII will cause less bleeding than factor Xa or thrombin inhibitors, facilitating therapy in situations where anticoagulation is currently avoided, and expanding the pool of patients eligible for treatment. To this end, several strategies targeting FXI and FXII are under development, including ASOs that inhibit synthesis of FXI [6▪,8,85–87], monoclonal IgGs that bind to precursor and/or active forms of FXI and FXII [88,89,90▪▪], small molecules that block the FXIa active site [91,92▪], nucleic acid aptamers that bind and inhibit FXI or FXII [93–95], and glycosaminoglycan mimetics that allosterically inhibit the FXIa active site [96] (Table 1 and Fig. 2). Compounds tested in phase 2 trials, or for which phase 2 trials are in progress or planned, are discussed below.

Table 1.

Compounds-targeting factor XI and factor XII

| Strategy | Compound | Target | Mechanism of action and method of administration | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antisense oligonucleotide | IONIS-FXIRx/BAY2306001 | FXI | Reduces hepatic synthesis of FXI. Subcutaneous admin | [60,85] |

| mAbs | BAY1213790/Osocimab | FXIa | Allosteric inhibition of FXIa. Intravenous admin | [90▪▪] |

| AB023/Xisomab | FXI FXIa |

Binds to Apple 2 domain of FXI and inhibits its activation by FXIIa. Binds to FXIa and inhibits activation of FXIIa. Intravenous admin | [59,89] | |

| MAA868 | FXI and FXIa | Binds to the FXI and FXIa catalytic domain locking protein in zymogen form. Intravenous admin | [88] | |

| Garadacimab/CSL312 | FXIIa | Binds to the FXIIa catalytic domain near the active site. Intravenous admin | [37,97] | |

| AB052 | FXII FXIIa |

Binds to FXII and FXIIa near the active site. Intravenous admin | [84] | |

| Small molecule inhibitors | BMS986177/JNJ-70033093 | FXIa | Blocks FXIa active site. Oral admin | [98,99] |

| EP-7041 | FXIa | Blocks FXIa active site. Intravenous admin | [100] | |

| ONO-8610539 | FXIa | Block FXIa active site. Intravenous admin | [101,102] | |

| ONO-7750512 | FXIa | Block FXIa active site. Oral admin | [103] | |

| ONO-5450598 | FXIa | Block FXIa active site. Oral admin | [104] | |

| Aptamers | 12.7, 11.16 | FXI, FXIa | RNA aptamers bind to FXI/XIa anion binding site on catalytic domain. Allosteric inhibition | [94] |

| FELIAP | FXIa | DNA aptamer binds at or near the FXIa active site | [105] | |

| R4cXII-1t | FXII/FXIIa | RNA aptamer inhibits FXI activation by FXIIa and autoactivation of FXII | [93] | |

| Glycosaminoglycan based small inhibitors | Sulfated chiro-inositol | FXIa | Binds to FXI/XIa anion binding site on catalytic. Allosteric inhibitor | [96] |

FXI, factor XI; FXIa, factor XIa; FXII, factor XII; FXIIa, factor XIIa.

FIGURE 2.

Mechanisms of action of drugs targeting contact activation. Blue figures represent factor XI and factor XIa, and green figures represent factor XII and factor XIIa. The catalytic domains of factor XII and factor XI are indicated by CD, and the serine protease active sites of factor XIIa and factor XIa are indicated by AS. The red T-bars indicate the parts of the molecule with which individual drugs interact. In the case of the antisense oligonucleotide, the drug targets factor XI mRNA in hepatocytes, reducing production of factor XI protein. GAG, glycosaminoglycan; SMI, small molecule inhibitor; MAb, monoclonal antibody. Drugs marked by an asterisk (*) are being studied in phase II trials.

Factor XI antisense oligonucleotide: IONIS-FXIRx (BAY2306001)

IONIS-FXIRx is a subcutaneously administered DNA-based ASO containing an antisense sequence specific for human FXI mRNA [85]. The drug is taken up by several cell types including hepatocytes. FXI mRNA bound to IONIS-FXIRx is degraded by endogenous RNAse, resulting in reduced FXI synthesis. A phase II trial involving 300 patients compared IONIS-FXIRx with enoxaparin for VTE prophylaxis in patients undergoing elective knee arthroplasty [85]. The primary endpoint was venous thrombosis detected clinically or by venography 8–12 days after surgery. IONIS-FXIRx given in doses of 200 or 300 mg starting 35 days before surgery reduced plasma FXI, on average, to 38 and 20% of the normal concentration (~30 nmol/l) by the day of surgery. The incidence of VTE was similar for patients treated with 200 mg IONIS-FXIRx and enoxaparin (27 vs. 30%), while 300 mg IONIS-FXIRx (4% VTE incidence) was superior to enoxaparin. There was a trend toward less bleeding with the ASO. It is important to note that patients receiving IONIS-FXIRx were under the full effect of the drug during surgery. Despite this, hemostasis during and after surgery appeared normal.

Phase 2 trials (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT02553889 and NCT03358030) are underway to study IONIS-FXIRx in chronic renal dialysis patients, a particularly difficult group to treat with anticoagulation. Preliminary data suggest that patients treated with IONIS-FXIRx had less clot formation within dialysis circuits than patients who did not receive the ASO [106].

Factor XIa mAb: osocimab (BAY1213790)

Osocimab is a fully humanized IgG that binds FXIa near its active site [90▪▪,107]. In the FOXTROT Trial (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT03276143) the drug was studied in patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty [90▪▪]. Osocimab was administered as single postoperative intravenous infusions of 0.3, 0.6, 1.2, or 1.8 mg/kg, or preoperative infusions of 0.3 or 1.8 mg/kg, and was compared with 10 days of postoperative enoxaparin (40 mg/day) or apixaban (2.5 mg/day). The primary outcome was incidence of symptomatic VTE or VTE 10–13 days postoperatively identified by venography. Except for 0.3 mg/kg doses, all osocimab doses met noninferiority criteria compared with enoxaparin. The 1.8 mg/kg preoperative dose was superior to enoxaparin (11.3 vs. 26.3% incidence), and similar to apixaban (14.5%). Major or clinically relevant bleeding occurred in 4.7% of patients on osocimab, 5.9% on enoxaparin, and 2% on apixaban.

Factor XIa small molecule active site inhibitor: BMS-986177 (JNJ-70033093)

BMS-986177 is an orally administered small molecule inhibitor that binds to the FXIa active site [91,92▪]. It has completed extensive phase I testing in healthy volunteers and in a small number of patients with moderate-to-severe renal insufficiency. BMS-986177 is undergoing evaluation in two phase 2 trials. In the AXIOMATIC-SSP trial (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT03766581), BMS-986177 is being compared with placebo for secondary prevention of stroke in patients with small ischemic strokes or high-risk transient ischemic attacks who are on aspirin and clopidogrel. In the AXIOMATIC-TKR study (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT03891524) BMS-986177 is being compared with standard dose enoxaparin for prevention of VTE in patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty.

Factor XIIa mAb: garadacimab (CSL312)

Garadacimab is a humanized IgG directed against the FXIIa active site. The drug is undergoing evaluation in patients with hereditary angioedema for prevention of symptoms due to excessive bradykinin production (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT03712228) [97,108]. Results from preclinical studies suggest it’s activity could be useful in preventing thrombus formation on artificial surfaces. IgG 3F7, an early version of garadacimab, was as effective as heparin at preventing thrombus formation in a rabbit ECMO model [37]. In contrast to heparin, 3F7 had no demonstrable effect on hemostasis. A Phase 1/2 study to investigate the efficacy of garadacimab in preventing catheter-associated blood clots in subjects with cancer receiving chemotherapy through PICC lines (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT04281524) was to start in March 2020, but was put on hold for non-safety-related reasons.

SUMMARY AND FUTURE CONSIDERATIONS

Results of trials with IONIS-FXIRx and osocimab support the premise that inhibiting FXI/FXIa reduces the incidence of VTE [85,90▪▪]. Within a few years we should have additional data with these agents and the oral inhibitor BMS-986177 to inform phase 3 trials comparing FXI inhibition with standard care for preventing VTE and ischemic stroke. Primary or secondary prevention of VTE and stroke are the indications best supported by epidemiologic data [61–65]. Patients at high risk of bleeding or who have renal insufficiency may also tolerate FXI-directed therapy better than warfarin or a DOAC. Inhibitors of either FXI or FXII may be particularly useful for safely preventing clots on artificial surfaces. For example, central venous catheters are associated with a significant rate of thrombosis [109]. These devices are often used in patients with conditions such as cancer that increase bleeding risk with standard anticoagulation therapy. Similarly, anticoagulation-related bleeding is common in patients on ECMO, often leading to termination of therapy [110,111]. In both situations, a contact factor inhibitor may reduce thrombus formation by blunting surface-induced thrombin generation with relatively little impact on hemostasis. It may also be possible to administer contact inhibitors in combination with standard treatment to enhance efficacy, while improving safety by facilitating dose-reduction of the standard therapy.

A hypothetical advantage of contact factor inhibitors over DOACs is that they could be given in amounts sufficient to completely suppress activity of a target without having a major impact on hemostasis. While it is highly likely that this will be the case for FXII/XIIa inhibitors, the situation is less clear for FXI. Data from the FOXTROT trial suggested more bleeding in patients given a large dose of preoperative osocimab than in patients on postoperative apixaban [90▪▪]. While larger trials are required to address the safety issue, the findings raise questions regarding optimal intensity for FXI inhibition. Bleeding associated with FXI deficiency tends to be greatest in patients with FXI levels 15% or less of the normal plasma concentration (30 nmol/l) [112]. Data from nonhuman primates studies [60] and the IONIS-FXIRx study [85] suggest that a maximum antithrombotic effect is achieved by reducing plasma FXI to ~20% of the normal concentration. Perhaps targeting therapy to this level would provide a balance between efficacy and safety.

The anti-inflammatory properties of FXI and FXII antibodies in preclinical studies in nonhuman primates [83▪▪,84] suggest they may be useful in preventing tissue damage in patients with consumptive coagulopathies related to sepsis. Conventional anticoagulants have met with limited success in this setting, and their use is complicated by significant bleeding. FXI or FXII inhibitors may be better tolerated in this setting because of their limited effects on hemostasis. Their anti-inflammatory properties may also blunt the SIRS. It would be interesting to test such agents in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 to prevent development of the thrombo-inflammatory component of the syndrome that contributes to significant organ damage.

KEY POINTS.

The plasma proteases FXI and FXII contribute to pathologic thrombus formation, but play relatively minor roles in hemostasis.

Drugs targeting these proteases have impressive effects in preclinical thrombosis models, while having little effect on hemostasis.

In phase 2 trials, drugs targeting FXI were comparable to standard of care for thrombosis prophylaxis during knee replacement therapy.

In knee replacement trials, preoperative administration of drugs targeting FXI did not appear to compromise hemostasis during or after surgery.

Therapy with FXI or FXII inhibitors may be associated with lower risk of serious bleeding compared with currently used anticoagulant.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the support of the Ernest W. Goodpasture Chair in Experimental Pathology for Translational Research from Vanderbilt University.

Financial support and sponsorship

The current work was supported by grant HL140025 from the National Heart, Lung and blood Institute.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

P.S. has no conflict to report. D.S. is a consultant for several pharmaceutical companies that are developing compounds that target factor XI and factor XII for therapeutic purposes.

REFERENCES AND RECOMMENDED READING

Papers of particular interest, published within the annual period of review, have been highlighted as:

▪ of special interest

▪▪ of outstanding interest

- 1.Simon EM, Streitz MJ, Sessions DJ, Kaide CG. Anticoagulation reversal. Emerg Med Clin North Am 2018; 36:585–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Es N, Coppens M, Schulman S, et al. Direct oral anticoagulants compared with vitamin K antagonists for acute venous thromboembolism: evidence from phase 3 trials. Blood 2014; 124:1968–1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weitz JI, Jaffer IH, Fredenburgh JC. Recent advances in the treatment of venous thromboembolism in the era of the direct oral anticoagulants. F1000 Res 2017; 6:985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kearon C, Akl EA, Ornelas J, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest 2016; 149:315–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khorana AA, Noble S, Lee AYY, et al. Role of direct oral anticoagulants in the treatment of cancer-associated venous thromboembolism: guidance from the SSC of the ISTH. J Thromb Haemost 2018; 16:1891–1894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. ▪.Weitz JI, Chen NC. Novel antithrombotic strategies for treatment of venous thromboembolism. Blood 2020; 135:351–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; An excellent review of novel strategies for treating venous thromboembolism, including discussions of inhibition of factor XI (FXI) and factor XII (FXII).

- 7.Schmaier AH. Antithrombotic potential of the contact activation pathway. Curr Opin Hematol 2016; 23:445–452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tillman BF, Gruber A, McCarty OJT, Gailani D. Plasma contact factors as therapeutic targets. Blood Rev 2018; 32:433–448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Visser M, Heitmeier S, Ten Cate H, Spronk HMH. Role of factor XIa and plasma kallikrein in arterial and venous thrombosis. Thromb Haemost 2020; 106:883–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmaier AH. The contact activation and kallikrein/kinin systems: pathophysiologic and physiologic activities. J Thromb Haemost 2016; 14:28–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Long AT, Kenne E, Jung R, et al. Contact system revisited: an interface between inflammation, coagulation, and innate immunity. J Thromb Haemost 2016; 14:427–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin L, Wu M, Zhao J. The initiation and effects of plasma contact activation: an overview. Int J Hematol 2017; 105:235–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schmaier AH, Emsley J, Feener EP, et al. Nomenclature of factor XI and the contact system. J Thromb Haemost 2019; 17:2216–2219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maas C, Renné T. Coagulation factor XII in thrombosis and inflammation. Blood 2018; 131:1903–1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Revenko AS, Gao D, Crosby JR, et al. Selective depletion of plasma prekallikrein or coagulation factor XII inhibits thrombosis in mice without increased risk of bleeding. Blood 2011; 118:5302–5311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Margaglione M, D’Apolito M, Santocroce R, Maffione AB. Hereditary angioedema: looking for bradykinin production and triggers of vascular permeability. Clin Exp Allergy 2019; 49:1395–1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gailani D, Wheeler AP, Neff AT. Rare coagulation factor deficiencies In: Hoffman R, editor. Hematology basic principles and practice, Seventh ed Philadelphi, PA: Elsevier; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Müller F, Mutch NJ, Schenk WA, et al. Platelet polyphosphates are proinflammatory and procoagulant mediators in vivo. Cell 2009; 139:1143–1156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Choi SH, Smith SA, Morrissey JH. Polyphosphate is a cofactor for the activation of factor XI by thrombin. Blood 2011; 118:6963–6970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morrissey JH, Smith SA. Polyphosphate as modulator of hemostasis, thrombosis, and inflammation. J Thromb Haemost 2015; 13(Suppl 1):S92–S97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang Y, Ivanov I, Smith SA, et al. Polyphosphate, Zn(2+) and high molecular weight kininogen modulate individual reactions of the contact pathway of blood clotting. J Thromb Haemost 2019; 17:2131–2140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kannemeier C, Shibamiya A, Nakazawa F, et al. Extracellular RNA constitutes a natural procoagulant cofactor in blood coagulation. Proc Natl Acad of Sci U S A 2007; 104:6388–6393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fuchs TA, Brill A, Duerschmied D, et al. Extracellular DNA traps promote thrombosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010; 107:15880–15885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gould TJ, Vu TT, Swystun LL, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps promote thrombin generation through platelet-dependent and platelet-independent mechanisms. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2014; 34:1977–1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ivanov I, Shakhawat R, Sun MF, et al. Nucleic acids as cofactors for factor XI and prekallikrein activation: different roles for high-molecular-weight kininogen. Thromb Haemost 2017; 117:671–681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pathak M, Kaira BG, Slater A, Emsley J. Cell receptor and cofactor interactions of the contact activation system and factor XI. Front Med (Lusanne) 2018; 5:66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Raghunathan V, Zilberman-Rudenko J, Olson SR, et al. The contact pathway and sepsis. Res Prac Thromb Haemost 2019; 3:331–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maas C, Govers-Riemslag JWP, Bouma B, et al. Misfolded proteins activate factor XII in humans, leading to kallikrein formation without initiating coagulation. J Clin Invest 2008; 118:3208–3218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jaffer IH, Fredenburgh JC, Hirsh J, Weitz JI. Medical device-induced thrombosis: what causes it and how can we prevent it? J Thromb Haemost 2015; 13(S1):S72–S81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tillman B, Gailani D. Inhibition of factors XI and XII for prevention of thrombosis induced by artificial surfaces. Semin Thromb Hemost 2018; 44:60–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yau JW, Stafford AR, Liao P, et al. Corn trypsin inhibitor coating attenuates the prothrombotic properties of catheters in vitro and in vivo. Acta Biomater 2012; 8:4092–4100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sniecinski RM, Chandler WL. Activation of the hemostatic system during cardiopulmonary bypass. Anesth Analg 2011; 113:1319–1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wendel HP, Jones DW, Gallimore MJ. FXII levels, FXIIa-like activities and kallikrein activities in normal subjects and patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Immunopharmacology 1999; 45:141–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Worm M, Köhler EC, Panda R, et al. The factor XIIa blocking antibody 3F7: a safe anticoagulant with anti-inflammatory activities. Ann Transl Med 2015; 3:247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Frank RD, Weber J, Dresbach H, et al. Role of contact system activation in hemodialyzer-induced thrombogenicity. Kidney Int 2001; 60:1972–1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mohammed BM, Matafonov A, Ivanov I, et al. An update on factor XI structure and function. Thromb Res 2018; 161:94–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Larsson M, Rayzman V, Nolte MW, et al. A factor XIIa inhibitory antibody provides thromboprotection in extracorporeal circulation without increasing bleeding risk. Sci Transl Med 2014; 6:222ra17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Matafonov A, Leung PY, Gailani AE, et al. Factor XII inhibition reduces thrombus formation in a primate thrombosis model. Blood 2014; 123:1739–1746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. ▪.Wallisch M, Lorentz CU, Lakshmanan HHS, et al. Antibody inhibition of contact factor XII reduces platelet deposition in a model of extracorporeal membrane oxygenator perfusion in nonhuman primates. Res Pract Thromb Haemost 2020; 4:205–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Demonstration of the ability of anti-FXII antibody to prevent thrombus formation on components of an extracorporeal oxygenator circuit in a primate model.

- 40.James P, Salomon O, Mikovic D, Peyvandi F. Rare bleeding disorders - bleeding assessment tools, laboratory aspects and phenotype and therapy of FXI deficiency. Haemophilia 2014; 20(Suppl 4):71–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wheeler AP, Gailani D. Why factor XI deficiency is a clinical concern. Expert Rev Hematol 2016; 9:629–637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Puy C, Rigg RA, McCarty OJ. The hemostatic role of factor XI. Thromb Res 2016; 141(Suppl 2):S8–S11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Asakai R, Chung DW, Davie EW, Seligsohn U. Factor XI deficiency in Ashkenazi Jews in Israel. N Engl J Med 1991; 325:153–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Salomon O, Steinberg DM, Seligshon U. Variable bleeding manifestations characterize different types of surgery in patients with severe factor XI deficiency enabling parsimonious use of replacement therapy. Haemophilia 2006; 12:490–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mumford AD, Ackroyd S, Alikhan R, et al. Guideline for the diagnosis and management of the rare coagulation disorders. Brit J Haematol 2014; 167:304–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Duga S, Salomon O. Congenital factor XI deficiency: an update. Sem Thromb Hemost 2013; 39:621–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kadir RA, Economides DL, Lee CA. Factor XI deficiency in women. Am J Hematol 1999; 60:48–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rosen ED, Gailani D, Castellino FJ. FXI is essential for thrombus formation following FeCl3-induced injury of the carotid artery in the mouse. Thromb Haemost 2002; 87:774–776. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang X, Cheng Q, Xu L, et al. Effects of factor IX or factor XI deficiency on ferric chloride-induced carotid artery occlusion in mice. J Thromb Haemost 2005; 3:695–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Renné T, Pozgajová M, Grüner S, et al. Defective thrombus formation in mice lacking coagulation factor XII. J Exp Med 2005; 202:271–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang X, Smith PL, Hsu MY, et al. Effects of factor XI deficiency on ferric chloride-induced vena cava thrombosis in mice. J Thromb Haemost 2006; 4:1982–1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bird JE, Smith PL, Wang X, et al. Effects of plasma kallikrein deficiency on haemostasis and thrombosis in mice: murine ortholog of the Fletcher trait. Thromb Haemost 2012; 107:1141–1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Merkulov S, Zhang WM, Komar AA, et al. Deletion of murine kininogen gene 1 (mKng1) causes loss of plasma kininogen and delays thrombosis. Blood 2008; 111:1274–1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gailani D, Gruber A. Factor XI as a therapeutic target. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2016; 36:1316–1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Minnema MC, Friederich PW, Levi M, et al. Enhancement of rabbit jugular vein thrombolysis by neutralization of factor XI. In vivo evidence for a role of factor XI as an antifibrinolytic factor. J Clin Invest 1998; 101:10–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yau JW, Liao P, Fredenburgh JC, et al. Selective depletion of factor XI or factor XII with antisense oligonucleotides attenuates catheter thrombosis in rabbits. Blood 2014; 123:2102–2107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gruber A, Hanson SR. Factor XI-dependence of surface- and tissue factor-initiated thrombus propagation in primates. Blood 2003; 102:953–955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tucker EI, Mrazek UM, White TC, et al. Prevention of vascular graft occlusion and thrombus-associated thrombin generation by inhibition of factor XI. Blood 2009; 113:936–944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cheng Q, Tucker EI, Pine MS, et al. A role for factor XIIa-mediated factor XI activation in thrombus formation in vivo. Blood 2010; 116:3981–3989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Crosby JR, Mrazek U, Revenko AS, et al. Antithrombotic effect of antisense factor XI oligonucleotide treatment in primates. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2013; 33:1670–1678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Salomon O, Steinberg DM, Zucker M, et al. Patients with severe factor XI deficiency have a reduced incidence of deep-vein thrombosis. Thromb Haemost 2011; 105:269–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Salomon O, Steinberg DM, Koren-Morag N, et al. Reduced incidence of ischemic stroke in patients with severe factor XI deficiency. Blood 2008; 111:4113–4117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Preis M, Hirsch J, Kotler A, et al. Factor XI deficiency is associated with lower risk for cardiovascular and venous thromboembolism events. Blood 2017; 129:1210–1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li Y, Bezemer ID, Rowland CM, et al. Genetic variants associated with deep vein thrombosis: the F11 locus. J Thromb Haemost 2009; 7:1802–1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Folsom AR, Tang W, Roetker NS, et al. Prospective study of circulating factor XI and incident venous thromboembolism: the Longitudinal Investigation of Thromboembolism Etiology (LITE). Am J Hematol 2015; 90:1047–1051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Suri MFK, Yamagishi K, Aleksic N, et al. Novel hemostatic factor levels and risk of ischemic stroke: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Cerebrovasc Dis 2010; 29:497–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Siegerink B, Govers-Riemslag JWP, Rosendaal FR, et al. Intrinsic coagulation activation and the risk of arterial thrombosis in young women: results from the Risk of Arterial Thrombosis in relation to Oral contraceptives (RATIO) case-control study. Circulation 2010; 122:1854–1861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Doggen CJM, Rosendaal FR, Meijers JCM. Levels of intrinsic coagulation factors and the risk of myocardial infarction among men: opposite and synergistic effects of factors XI and XII. Blood 2006; 108:4045–4051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Salomon O, Steinberg DM, Dardik R, et al. Inherited factor XI deficiency confers no protection against acute myocardial infarction. J Thromb Haemost 2003; 1:658–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Koster T, Rosendaal FR, Briet E, Vandenbroucke JP. John Hageman’s factor and deep-vein thrombosis: Leiden Thrombophilia Study. Brit J Haematol 1994; 87:422–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zeerleder S, Schloesser M, Redondo M, et al. Reevaluation of the incidence of thromboembolic complications in congenital factor XII deficiency - a study on 73 subjects from 14 Swiss families. Thromb Haemost 1999; 82:1240–1246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Halbmayer WM, Mannhalter C, Feichtinger C, et al. The prevalence of factor XII deficiency in 103 orally anticoagulated outpatients suffering from recurrent venous and/or arterial thromboembolism. Thromb Haemost 1992; 68:285–290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cushman M, O’Meara ES, Folsom AR, Heckbert SR. Coagulation factors IX through XIII and the risk of future venous thrombosis: the longitudinal investigation of thromboembolism etiology. Blood 2009; 114:2878–2883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Endler G, Marsik C, Jilma B, et al. Evidence of a U-shaped association between factor XII activity and overall survival. J Thromb Haemost JTH 2007; 5:1143–1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Folsom AR, Tang W, Basu S, et al. Plasma concentrations of high molecular weight kininogen and prekallikrein and venous thromboembolism incidence in the general population. Thromb Haemost 2019; 119:834–843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Parikh RR, Folsom AR, Misialek JR, et al. Prospective studyof plasma high molecular weight kininogen and prekallikrein and incidence of coronary heart disease, ischemic stroke and heart failure. Thromb Res 2019; 182:89–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Didiasova M, Wujak L, Schaefer L, Wygrecka M. Factor XII in coagulation, inflammation and beyond. Cell Signal 2018; 51:257–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.van de Veerdonk FL, Netea MG, van Deuren M, et al. Kallikrein-kinin blockade in patients with COVID-19 to prevent acute respiratory distress syndrome. E-life 2020; 9:e57555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tucker EI, Gailani D, Hurst S, et al. Survival advantage of coagulation factor XI-deficient mice during peritoneal sepsis. J Infect Dis 2008; 198:271–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Luo D, Szaba FM, Kummer LW, et al. Factor XI-deficient mice display reduced inflammation, coagulopathy, and bacterial growth during listeriosis. Infect Immun 2012; 80:91–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tucker EI, Verbout NG, Leung PY, et al. Inhibition of factor XI activation attenuates inflammation and coagulopathy while improving the survival of mouse polymicrobial sepsis. Blood 2012; 119:4762–4768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bane CE Jr, Ivanov I, Matafonov A, et al. Factor XI deficiency alters the cytokine response and activation of contact proteases during polymicrobial sepsis in mice. PLoS One 2016; 11:e0152968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. ▪▪.Silasi R, Keshari RS, Lupu C, et al. Inhibition of contact-mediated activation of factor XI protects baboons against S. aureus-induced organ damage and death. Blood Adv 2019; 3:658–669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The article reports the role of FXI in Staphylococcus aureus induced inflammation and sepsis progression in baboons. The anti-FXI antibody 3G3 prevented sepsis-induced organ failure and death in this study.

- 84.Lupu F, Keshari R, Silasi R, et al. Blocking activated factor XII with a monoclonal antibody prevents organ failure and saves baboons challenged with heat-inactivated S. aureus. Res Pract Thromb Haemost 2019; 3:S127–S128. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Büller HR, Bethune C, Bhanot S, et al. Factor XI antisense oligonucleotide for prevention of venous thrombosis. N Engl J Med 2015; 372:232–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lippi G, Harenberg J, Mattiuzzi C, Favaloro EJ. Next generation antithrombotic therapy: focus on antisense therapy against coagulation factor XI. Sem Thromb Hemost 2015; 41:255–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.DeLoughery EP, Olson SR, Puy C, et al. The safety and efficacy of novel agents targeting factors XI and XII in early phase human trials. Sem Thromb Hemost 2019; 45:502–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Koch AW, Schiering N, Melkko S, et al. MAA868, a novel FXI antibody with a unique binding mode, shows durable effects on markers of anticoagulation in humans. Blood 2019; 133:1507–1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lorentz CU, Verbout NG, Wallisch M, et al. Contact activation inhibitor and factor XI antibody, AB023, produces safe, dose-dependent anticoagulation in a phase 1 First-In-Human Trial. Arterio Thromb Vasc Bio 2019; 39:799–809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. ▪▪.Weitz JI, Bauersachs R, Becker B, et al. Effect of osocimab in preventing venous thromboembolism among patients undergoing knee arthroplasty: the FOXTROT randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2020; 323:130–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The article reports the results for the phase FOXTROT trial compares a mAb that inhibits FXIa with standard care in patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty. The study compares the effects of FXIa inhibition administered before and after surgery.

- 91.Quan ML, Pinto DJP, Smallheer JM, et al. Factor XIa inhibitors as new anticoagulants. J Med Chem 2018; 61:7425–7447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. ▪.Al-Horani RA. Factor XI(a) inhibitors for thrombosis: an updated patent review (2016–present). Expert Opin Ther Pat 2020; 30:39–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The article reviews advances in inhibition of FXI(a) with small molecule inhibitors, antibodies, and oligonucleotides since 2016. This is an excellent pharmacologic review.

- 93.Woodruff RS, Xu Y, Layzer J, et al. Inhibiting the intrinsic pathway of coagulation with a factor XII-targeting RNA aptamer. J Thromb Haemost 2013; 11:1363–1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Woodruff RS, Ivanov I, Verhamme IM, et al. Generation and characterization of aptamers targeting factor XIa. Thromb Res 2017; 156:134–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Chabata CV, Frederiksen JW, Sullenger BA, Gunaratne R. Emerging applications of aptamers for anticoagulation and hemostasis. Curr Opin Hematol 2018; 25:382–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Al-Horani RA, Abdelfadiel EI, Afosah DK, et al. A synthetic heparin mimetic that allosterically inhibits factor XIa and reduces thrombosis in vivo without enhanced risk of bleeding. J Thromb Haemost 2019; 17:2110–2122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.A study to investigate CSL312 in subjects with hereditary angioedema (HAE) https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03712228.

- 98.A study on BMS-986177 for the prevention of a stroke in patients receiving aspirin and clopidogrel (AXIOMATIC-SSP) https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03766581.

- 99.A Study of JNJ-70033093 (BMS-986177) versus subcutaneous enoxaparin in participants undergoing elective total knee replacement surgery (AXIOMATIC-TKR) https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03891524.

- 100.Hayward NJ, Goldberg DI, Morrel EM, et al. Phase 1a/1b study of EP-7041: a novel, potent, selective, small molecule FXIa inhibitor. Circulation 2017; 136:A13747. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Sakimoto S, Hagio T, Yonetomi Y, et al. ONO-8610539, an injectable small-molecule inhibitor of blood coagulation factor XIa, improves cerebral ischemic injuries associated with phtothrombotic occlusion of rabbit middle cerebral artery. Stroke 2017; 48:AW286. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Sakai M, Hagio T, Koyama S, et al. Antithrombotic effect of ONO-8610539, a new potent and selective small molecule factor Xia inhibitor, in a monkey model of arteriovenous shunt. J Thromb Haemost 2015; 13(Sup2): 230–231. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Koyama S, Ono T, Harada K, et al. Discovery of ONO-7750512, and orally bioavailable small molecule factor XIa inhibitor: the pharmacokinetic and pharmacological profiles. J Thromb Haemost 2015; 13(Sup1):389 (Abstract PO351). [Google Scholar]

- 104.Koyama S, Ono T, Hagio T, et al. Discovery of ONO-5450598, a highly orally bioavailable small molecule factor XIa inhibitor: the pharmacokinetic and pharmacological profiles. Res Pract Thromb Haemost 2017; 1(Sup1):1038 (Abstract PB21391). [Google Scholar]

- 105.Donkor DA, Bhakata V, Eltringham-Smith LJ, et al. Selection and characterization of a DNA aptamer inhibiting coagulation factor Xia. Sci Rep 2017; 7:2102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Bethune C, Walsh M, Jung B, et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of Ionis-FXIRx, an antisense inhibitor of factor XI, in patients with end-stage renal disease on hemodialysis. Blood 2017; 130(Suppl 1):1116. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Thomas D, Thelen K, Kraff S, et al. BAY 1213790, a fully human IgG1 antibody targeting coagulation factor XIa: first evaluation of safety, pharmacodynamics, and pharmacokinetics. Res Pract Thromb Haemost 2019; 3:242–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Cao H, Biondo M, Lioe H, et al. Antibody-mediated inhibition of FXIIa blocks downstream bradykinin generation. J Alllergy Clin 2018; 142:1355–1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Wall C, Moore J, Thachil J. Catheter-related thrombosis: a practical approach. J Intensive Care Soc 2016; 17:160–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Aubron C, DePuydt J, Belon F, et al. Predictive factors of bleeding events in adults undergoing extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Ann Intensive Care 2016; 6:97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Lotz C, Streiber N, Roewer N, et al. Therapeutic interventions and risk factors of bleeding during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. ASAIO J 2017; 63:624–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Brenner B, Laor A, Lupo H, et al. Bleeding predictors in factor-XI-deficient patients. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis 1997; 8:511–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]