Abstract

Micrococcal nuclease (MNase) is extensively used in genome-wide mapping of nucleosomes but its preference for AT-rich DNA leads to errors in establishing precise positions of nucleosomes. Here, we show that the MNase digestion of nucleosomes assembled on a strong nucleosome positioning sequence, Widom’s clone 601, releases nucleosome cores whose sizes are strongly affected by the linker DNA sequence. Our experiments produced nucleosomal DNA sizes varying between 147 and 155 bp, with positions of the MNase cuts reflecting positions of the A · T pairs rather than the nucleosome core/linker junctions determined by X-ray crystallography. Extent of chromatosomal DNA protection by linker histone H1 also depends on the linker DNA sequence. Remarkably, we found that a combined treatment with MNase and exonuclease III (exoIII) overcomes MNase sequence preference producing nucleosomal DNA trimmed symmetrically and precisely at the core/linker junctions regardless of the underlying DNA sequence. We propose that combined MNase/exoIII digestion can be applied to in situ chromatin for unbiased genome-wide mapping of nucleosome positions that is not influenced by DNA sequences at the core/linker junctions. The same approach can be also used for the precise mapping of the extent of linker DNA protection by H1 and other protein factors associated with nucleosome linkers.

Keywords: nucleosome positioning, micrococcal nuclease, exonuclease III, linker histone, 601 nucleosome

Introduction

In eukaryotic genomes, the DNA is packed into repeated units called nucleosomes. Each nucleosome contains 145–147 bp of DNA wrapped around an octamer of core histones to form the nucleosome core. Nucleosome cores are connected by 10–70 bp of the linker DNA forming nucleosome arrays. Recent developments in parallel sequencing technology allowed obtaining millions of nucleosomal DNA sequences genome-wide and mapping them to eukaryotic genomes ranging from yeast to human.1–3 It is generally believed that most nucleosomes are not randomly placed and that many of them, but not all, reside at preferred locations in the genome. This revolutionary progress opens exciting prospects for elucidating molecular mechanisms operative in nucleosome positioning, which in turn is essential for better understanding how the three-dimensional structure of chromatin is involved in the regulation of genes and other chromosomal elements. There is no consensus, however, to what degree nucleosome positions are dictated by the underlying DNA sequence or other factors.4–8 Nevertheless, it is clear that due to the helical nature of the DNA, small variations in the nucleosome positioning (about 5 bp) may have a dramatic effect on DNA accessibility to transcriptional factors3,9 and DNA repair and modification enzymes10,11 as well as a profound effect on chromatin higher-order structure12–14 and spontaneous mutations.15,16

To understand the mechanistic consequences of DNA organization in the nucleosome, one needs highly accurate information on both the precise nucleosome positions and their relative occurrences. The very first step in obtaining nucleosomal sequences includes the use of micrococcal nuclease (MNase) digestion of nuclear chromatin followed by size selection and parallel sequencing of the protected nucleosome core DNA. The main assumption here17 is that at limited digestion conditions, MNase first cuts the linker DNA and then trims the ends of the linker DNA, transiently stops at chromatosome, a particle containing ~165 bp of DNA and H1, and eventually removes the linker DNA to yield the core particle before digesting DNA within the nucleosome core. The midpoint between the MNase cleavages producing the ~145-bp core particle defines the position of the nucleosome dyad.

The sequence specificity of MNase is arguably the major shortcoming in the precise nucleosome position mapping. The fact that MNase cuts free DNA almost exclusively at the 5′ side of A·T base pairs18,19 is well established. As was shown by Dingwall et al.,20 the sequence preference of MNase on chromatin is the same as that on naked DNA. MNase predominantly cleaves the linker DNA in A/T sequences, but instead of reducing the linker DNA by direct exonucleolytic action, it rather cuts again at positions containing A/T nucleotides close to “some structural feature which provides the stop point of digestion.” In the case of chromatin, it would be either linker histone H1 or core histone octamer. This way of MNase action can explain why, as shown by Cockell et al.21 and McGhee and Felsenfeld,22 over the wide range of digestion time points, the frequency of A and T nucleotides at the 5′ termini of released nucleosomal DNA fragments is higher than 90%. More recent work that utilized high-throughput pyro-core sequencing of more than 187,000 nucleosomal DNA fragments also revealed that G/C nucleotides are considerably underrepresented on both residues immediately flanking the site of MNase cleavage.23 Concerns were also raised over the bias introduced by cutting preference of MNase in combination with the fragment size selection step prior to sequencing.24 Furthermore, native nucleosomes show surprisingly high variations in the susceptibility to MNase so that genome-wide mapping of the nucleosome occupancy is dependent on the extent of MNase digestion.25

On the other hand, caspase-activated DNase, an enzyme that cleaves DNA through a different enzymatic mechanism, was shown recently to provide an apparently equivalent pattern of nucleosome positions on in vitro reconstituted chromatin, which was considered as an argument against a substantial bias in MNase mapping.26 Nevertheless, in some positions, there were notable differences in nucleosome size distribution, indicating that the two nucleases are not entirely equivalent especially for precise mapping of the nucleosome core/linker junctions. However imperfect, the MNase treatment of nuclear chromatin has remained a universal tool for 25 years, since Satchwell et al.27 used MNase in their pioneering paper for extraction of nucleosomal DNA fragments from chicken erythrocytes.

To better understand the limitations caused by the MNase sequence specificity, and in a search of possible improvements of the existing method, we thoroughly studied the MNase cleavage of nucleosomal constructs based on the 601 DNA sequence. Clone 601 DNA28 contains a nucleosome positioning signal that defines the nucleosome dyad position with a single-nucleotide precision.29,30 In this clone 601, the DNA fragments that determine exceptionally high nucleosome stability are located in the center so that the DNA termini are likely to be insignificant for nucleosome positioning.31 That makes a nucleosome reconstituted on clone 601 DNA an ideal substrate for testing the effect of the DNA sequence at the entry–exit sites on MNase cutting. In our previous work,32 we observed that the MNase treatment detects a single nucleosome 601 position, with the center of the 149-bp core DNA close to the center of symmetry of the 601 DNA sequence.28 However, when we compared our data with the recently published X-ray structure of the nucleosome 601 core,33 we were intrigued to observe that the MNase cutting sites at the nucleosome core/linker junction were not precisely symmetric towards the dyad position. We hypothesized that the sequence preference together with orientation of the scissile bonds relative to the histone core were determining the precise position of the nucleosomal MNase cuts.

In this study, we show that the MNase digestion of mononucleosomes assembled in vitro on strong nucleosome positioning sequence 60128 with systematically modified linker DNA sequences releases nucleosomes whose sizes are greatly influenced by the DNA sequence—in particular, by position of the A·T pair closest to the core/linker junction. MNase does not cut within ~10 bp of the core/linker junction if there are no A·T pairs in that region. Predominant cuts occur in the A/T sequences on the linker DNA with secondary cuts inside the nucleosome core DNA where the minor groove of A·T pairs is exposed to solvent. To overcome the effect of MNase sequence specificity, we used a combined MNase and exoIII cleavage of the linker DNA, thereby producing nucleosomal DNA trimmed at the core/linker junction regardless of sequence. This method can be further used to obtain an unbiased pattern of nucleosome positioning in vivo and determine the nucleosome core/linker junctions throughout the genome at a single-nucleotide precision.

Results

MNase cuts nucleosomal DNA asymmetrically, predominantly in the A/T sequences closest to the nucleosome core/linker junctions

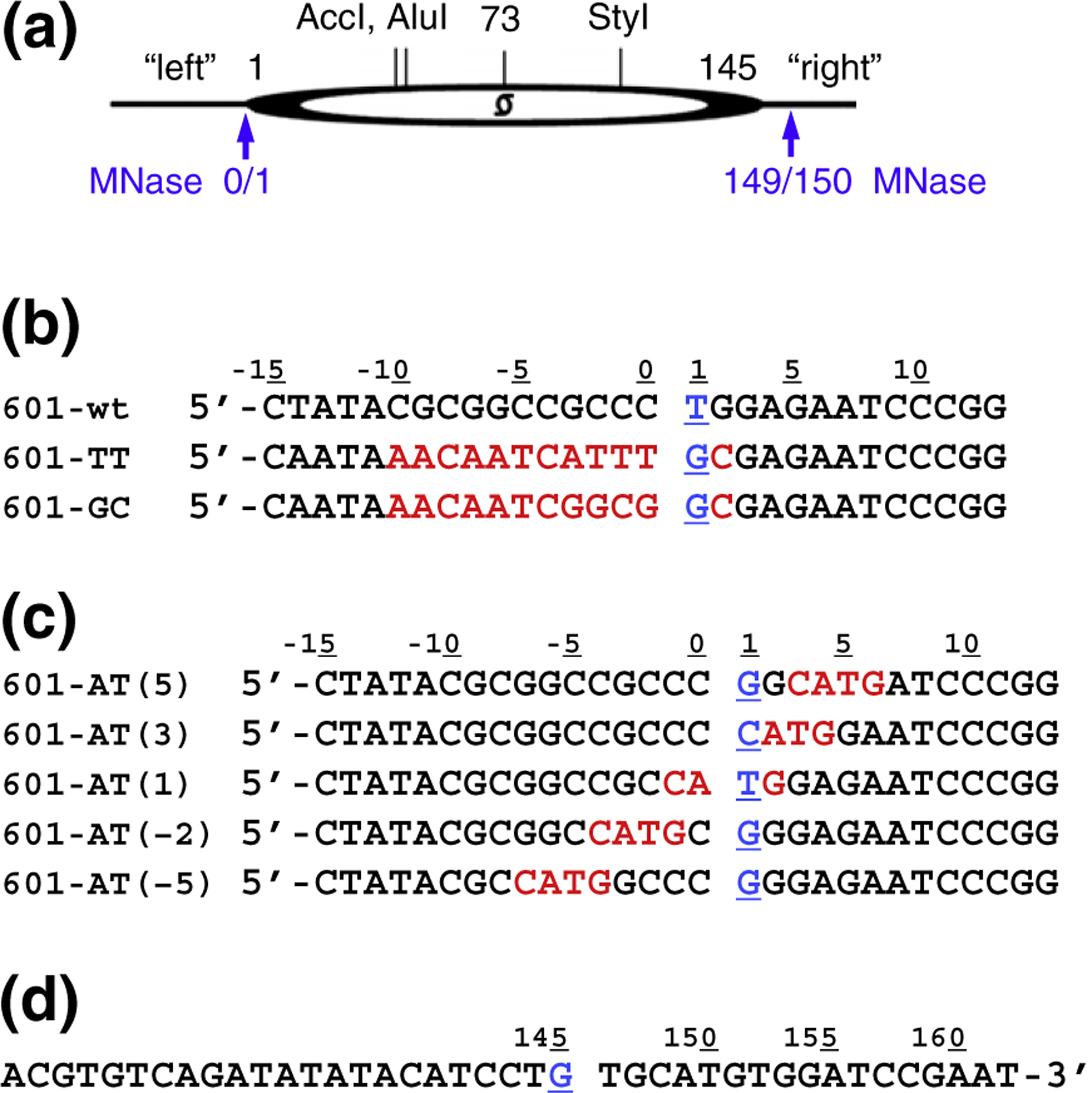

Earlier, we performed the MNase mapping of clone 601-based nucleosome array with a 207-bp repeat, 601–207×12.32 Comparing these results with the position of the dyad determined by X-ray crystallography,33 we observed that MNase released a 149-bp core particle where one linker (we designate it here as the “left” linker) was cut at the distance of 72 bp and the other linker (“right” linker) was cut at the distance of 76 bp from the dyad (Fig. 1a). We also found that the cut at the left linker occurred at a single A·T pair embedded in a string of G/C nucleotides. To examine if DNA sequence alterations would affect MNase cutting pattern, we prepared three 178-bp-long mononucleosome constructs with the first one (601-wt) having the sequence identical to the 601–207 positioning sequence,32 the other one (601-TT) was modified so that the left linker contained the TTT trinucleotide adjacent to the core/linker junction, and the third construct (601-GC) contained a G/C string effectively covering the core/linker junction (Fig. 1b). The right linker was not modified (Fig. 1d); we expected that mapping the position of the intact linker will allow us to detect any nucleosome repositioning that could have resulted from sequence alterations.

Fig. 1.

Clone 601-derived mononucleosomal constructs. (a) Scheme of the 601 mononucleosome. The dyad position at nucleotide #73 corresponds to nucleotide #0 of the DNA sequence in the X-ray nucleosome 601 structure.33 Positions of AccI, AluI, and StyI cutting sites and the left and right DNA linkers are shown. Blue arrows indicate MNase cleavage sites observed earlier.31 (b and c) Left linker DNA sequences in the mononucleosomal constructs. The underlined nucleotide #1 (in blue) corresponds to nucleotide −72 in the 145-bp-long core DNA.33 The changes in DNA sequences (compared to 601-wt) are highlighted in red. (d) All mononucleosomal constructs have the same right linker DNA sequence. The underlined nucleotide #145 (in blue) corresponds to nucleotide +72 in the 145-bp-long core DNA.33

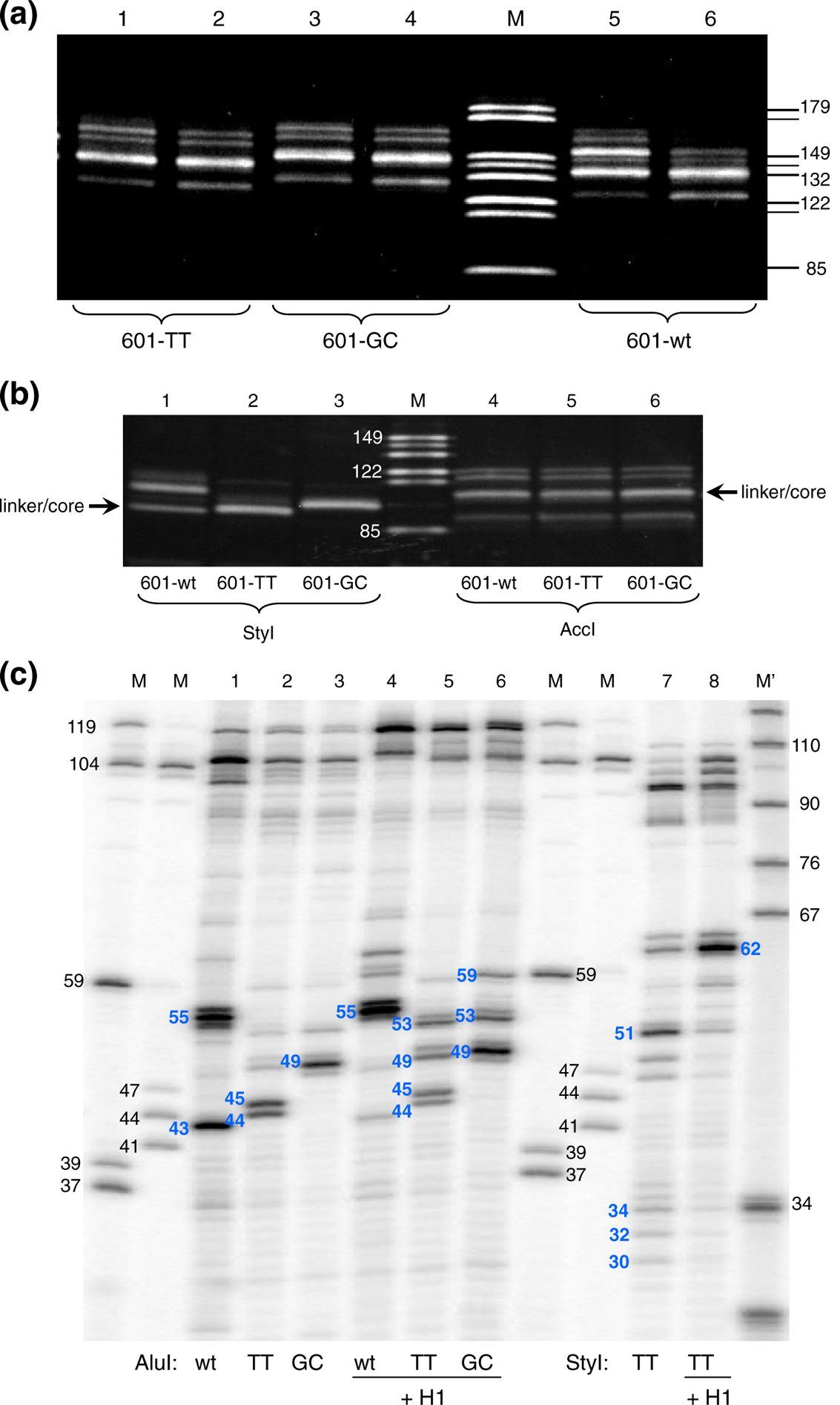

We reconstituted nucleosomes with stoichiometric amount of core histones to achieve ~100% incorporation of DNA into assembled nucleosomes. The reconstituted nucleosomes were examined by native PAGE (Fig. S1a, lanes 1 and 2) or native agarose gels (Fig. S1b, lanes 1 and 10) to achieve an almost complete incorporation of the DNA into the nucleosome band. If any free DNA was still present in the nucleosomal samples, this would not contribute to the pattern of MNase-digested material, because under the conditions used to digest nucleosomes (MNase concentration and time of digestion), the free DNA is completely digested (Fig. S2, lane 1). The reconstituted mononucleosomes were treated with two different MNase concentrations and time ranging from 15 s to 20 min, to find conditions that produce predominant cuts at the linker/core DNA junction (Fig. 2a and Fig. S2). We found that major bands corresponding to the nucleosome core size (as well as secondary bands) have different lengths for each nucleosome. We further digested DNA with the restriction enzymes (REs) StyI, AccI, and AluI to localize the positions of the MNase cuts in relation to the RE cuts (Fig. 1a). Band pattern on acrylamide gel (Fig. 2b) shows that the main DNA fragment resulting from digestion of nucleosome 601-GC at the left linker (lane 3) is longer than the one from nucleosome 601-TT (lane 2), while nucleosome 601-wt has two predominant cuts—one is close to the expected core/linker junction and another is within the linker DNA (lane 1). As expected, the DNA fragments representing the right linker have the same length, indicating that the nucleosome core position is the same for all three constructs (Fig. 2b, lanes 4–6).

Fig. 2.

MNase digestion of the nucleosomes with modified left linker sequences produce bands of different length. (a) Nucleosomes were digested with MNase and the resulting DNA fragments were separated on discontinuous 16% SDS/PAGE. Lanes 1 and 2, nucleosome 601-TT; lanes 3 and 4, nucleosome 601-GC; lanes 5 and 6, nucleosome 601-wt. Lanes 1, 3, and 5, digestion for 10 min; lanes 2, 4, and 6, digestion for 20 min. Lane M, size markers as indicated on the right side of the gel. (b) Lanes 1 and 4, nucleosome 601-wt; lanes 2 and 5, nucleosome 601-TT; lanes 3 and 6, nucleosome 601-GC. Nucleosomes were digested with MNase, and DNA was extracted and digested with RE StyI or AccI. Resulting fragments were separated on discontinuous 16% SDS/PAGE. Lanes 1 to 3 show DNA fragments between StyI site and MNase cuts on the left linker of nucleosomes 601-wt, 601-TT, and 601-GC, respectively. Lanes 4 to 6 show DNA fragments between AccI site and MNase cuts on the right linker of nucleosomes 601-wt, 601-TT, and 601-GC, respectively. Lane M, 149-, 144-, 132-, 122-, 114-, and 85-bp size markers. (c) MNase-digested DNA was purified, end labeled, digested with AluI or StyI, and separated on high-resolution 12% polyacrylamide-urea gel. Lanes 1 to 6 show the band patterns for MNase plus AluI-digested nucleosomes: 601-wt, 601-TT, 601-GC, 601-wt + H1, 601-TT + H1, and 601-GC + H1, respectively. Lanes 7 and 8 show the band patterns for MNase plus StyI-digested nucleosomes 601-TT and 601-TT + H1. Lanes M, size markers obtained by RE digestion of the clone 601 DNA. Lane M′, size markers prepared by MspI digestion of pBR322 DNA.

To determine precise locations of the MNase cuts, we ran the same material but now labeled on the 5′-ends (released by the MNase) with 32P on high-resolution denaturing gels (Fig. 2c and Fig. S3). Using markers generated from the same sequences, we were able to measure exact sizes of the DNA fragments and locate positions of MNase cuts on both linkers.

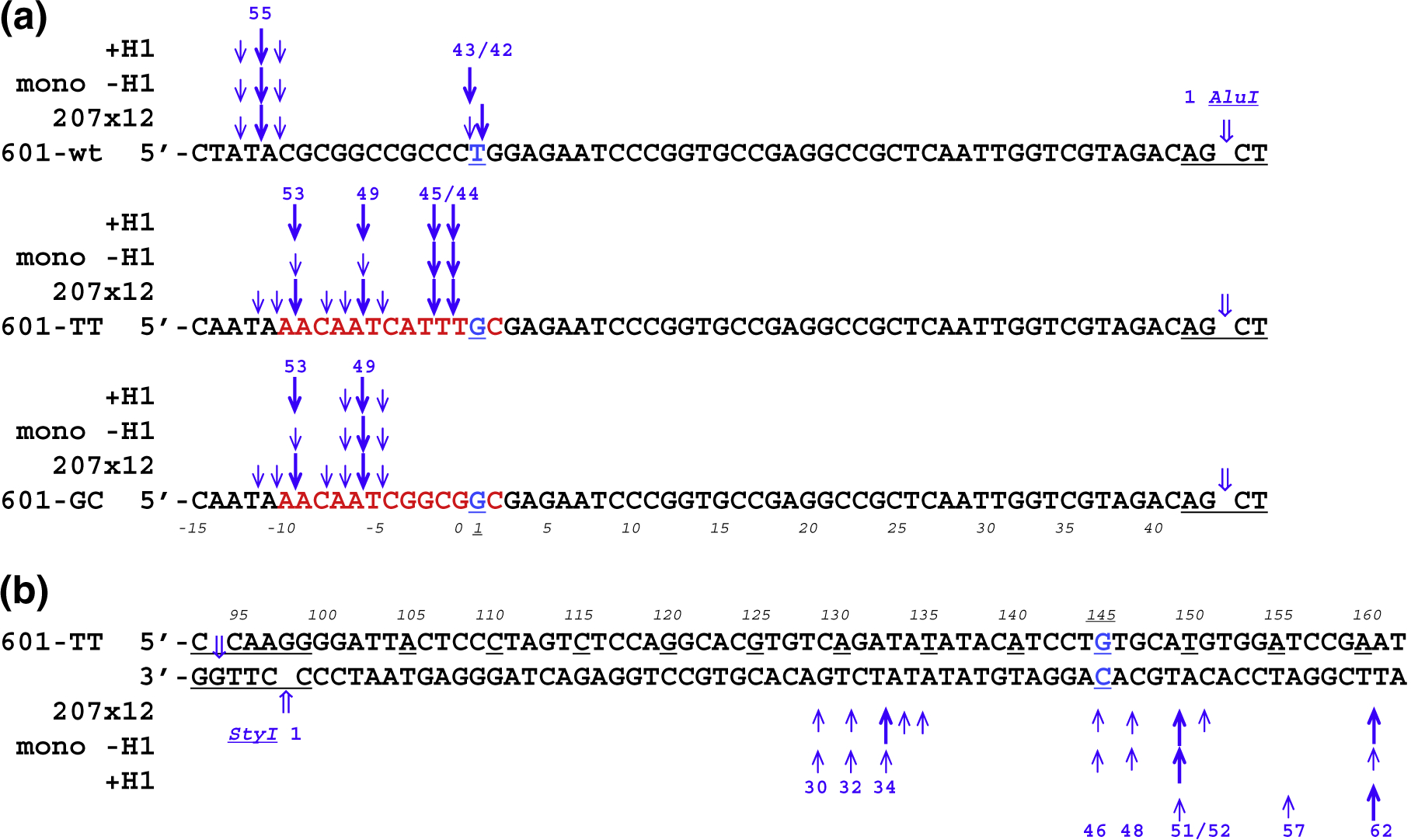

We found that on the left linker (AluI lanes), the strongest cleavages in 601-wt and 601-TT occurred in the A/T nucleotides located close to the nucleosome core/linker junction and right upstream of the G/C string. The 11-nt G/C string in 601-wt linker and the 8-nt G/C string in 601-GC, the latter covering the core/linker junction, are protected from MNase digestion (Fig. 3a). On the right linker (StyI lanes), the 601-TT nucleosome is cut predominantly between the A/T nucleotides most proximal to the core/linker junction, with some minor cuts further on the linker DNA or inside the core DNA (Figs. 2c and 3b). The nucleosomes 601-wt and 601-GC reveal the same MNase cleavage pattern on the right linker (data not shown; also, see below). All these cutting sites follow the same pattern consistent with previous findings:19–21 MNase cuts predominantly in A/T sequences proximal to G/C but does not cut between C and G nucleotides. Digestion with two different MNase concentrations and time ranging from 15 s to 20 min shows that the same pattern of cuts on the linker DNA is retained over a broad range of MNase digestion (Fig. S3).

Fig. 3.

Location of MNase cuts on the mononucleosomes and 207×12 oligonucleosome arrays with different left linkers. (a) Diagrams showing the positions of predominant and secondary MNase cutting sites at the left linkers of nucleosomes with and without histone H1, as well as oligonucleosomes 601-wt(207×12), 601-TT(207×12), and 601-GC(207×12). Numbers on the top indicate the size (nucleotides) of the fragments between the MNase and AluI cleavage sites. Numbers at the bottom (italic font) indicate nucleotide positions in the clone 601 nucleosome (cf. Fig. 1b). The size of the arrows is proportional to the intensity of MNase cleavage. (b) Diagrams showing the positions of predominant and secondary MNase cutting sites at the right linkers of nucleosome 601-TT, chromatosome 601-TT-H1, and oligonucleosome 601-TT(207×12). Numbers at the bottom indicate the sizes (nucleotides) of the fragments between the MNase and StyI cleavage sites. Numbers on the top (italic font) indicate nucleotide positions in the clone 601 nucleosome (cf. Fig. 1d).

Thus, the resulting nucleosome sizes are strongly influenced by the A/T positions versus the core/linker junction so that in the three nucleosomes with apparently the same position of the histone core, the MNase releases nucleosome cores with predominant sizes of 149 bp, 150 bp, and 154 bp, respectively (giving rise to the 43-, 44-, and 49-nt AluI fragments at the left linker and the 51-nt StyI fragment at the right linker; see Fig. 3a and b).

Extent of chromatosomal DNA protected by histone H1 depends on the nucleotide sequence in the linker DNA

In the presence of linker histone H1, limited digestion of random-sequence chromatin by MNase may release a nucleosome particle with about 165 bp of DNA known as the chromatosome.34 Previous works showed that in two different types of positioned nucleosomes, reconstitution with histone H1 leads to either asymmetric protection of 20 bp on one out of two linkers for 5S nucleosomes35 or apparently symmetric protection of 11 bp of the linker DNA on each side of the nucleosome core.32 Here, we examined whether DNA sequence affects the size of chromatosome. We reconstituted mononucleosomes with increasing amount of histone H1 and tested by band shifts on agarose gels to contain one molecule of histone H1 per nucleosome (Fig. S1b, lanes 5 and 14). We used three types of clone 601-derived nucleosomes (Fig. 1b) with equimolar amount of linker histone H1 to prepare nucleosome particles 601-wt + H1, 601-TT + H1, and 601-GC + H1, and mapped the MNase cutting pattern as above. We found that the number of base pairs protected by H1 on the left linker is different for each construct and does not correspond to either symmetric ~10-bp protection or asymmetric ~20-bp protection (Fig. S4a). The right linker is similarly protected in all three constructs (Fig. S4b).

To find precise locations of MNase cuts, we analyzed the same material but now labeled on 5′-ends with 32P on a sequencing gel (Fig. 2c, lanes 4–6 and 8). We found that the MNase cutting pattern for nucleosomes incubated with H1 follows the same rules as for nucleosomes without H1. As a result of MNase preference for the A/T sequences, histone H1 protects extra 12 bp on the left linker DNA in the case of 601-wt + H1, extra 8 bp in 601-TT + H1, extra 4 bp in 601-GC + H1, and extra 11 bp in the right linker in all three cases (Fig. 3a and b). It appears that both in the clone 601 mononucleosome and on the chromatosome, the two linkers are excised by MNase independently of each other and the precise cutting positions are dictated by a combination of the DNA sequence and the spatial hindrance resulting from DNA association with histones.

Nucleosomal arrays are cleaved by MNase predominantly at the same A·T pairs as observed for mononucleosomes

Since the 178-bp nucleosomes contained short linker DNA that are expected to readily unfold for MNase, we asked if the same pattern of MNase digestion could be observed in the context of a nucleosome array where linker DNA folding could contribute to its protection from the MNase. Therefore, we constructed 12-mer nucleosome arrays containing 207-bp nucleosome repeats where the nucleosome core/linker junctions contained sequences identical with the three constructs shown on Fig. 1b. We designate this nucleosome arrays as 601-wt(207×12), 601-TT(207×12), and 601-GC(207×12), respectively. The positions of MNase cuts in relation to the RE cuts were mapped exactly as we did for the mononucleosomes using a high-resolution denaturing gel (Fig. S5, lanes 1–6). At the left linker (AluI, lanes 1–3), the strongest cuts were at the A/T nucleotides located at the nearest proximity of the nucleosome core/linker junction. The G/C strings in the 601-wt(207×12) and at the 601-GC(207×12) linkers were completely protected from MNase digestion strikingly similar to the MNase digestion of corresponding mononucleosomes (Fig. 3a). As expected, on the right linker (StyI), we observed that all three nucleosomes were cut very similarly, predominantly at the A/T sequences proximal to the core/linker junction, with secondary cuts further on the linker DNA or inside the core DNA (Fig. 3b and Fig. S2, lanes 4–6).

In addition, we examined if the two DNA strands on the nucleosome are similarly protected from the MNase. To address this question, we labeled the 5′-ends released by RE from the 601-TT(207×12) and 601-GC(207×12) nucleosomes with 32P in addition to the previous labeling at the 5′-ends released by MNase (Fig. S5, lanes 7–14). The comparison of the additional bands resulting from the double labeling with the bands originating from single-labeled DNA shows that for majority of the MNase cutting sites, the nuclease digests the two DNA strands at the “complementary” positions. Thus, the sequence- and the position-specific cleavage of the A/T nucleotides is preserved in the nucleosome arrays and is not affected by linker DNA folding.

Position of the A/T sequence at the nucleosome core/linker junction determines the MNase cutting pattern

To systematically investigate how linker DNA sequence affects MNase digestion in the context of DNA assembled onto a nucleosome, we designed and prepared five additional mononucleosome constructs. Each of the new constructs has CATG tetranucleotide within the left GC-rich linker positioned at a different distance from the core/linker junction (Fig. 1c). We have chosen this combination of nucleotides because it has the AT dinucleotide, which is favored by MNase and also is a recognition site for NlaIII providing a convenient size marker derived from a homologous sequence. Having CATG at these positions within the GC-rich linker would allow us to answer the question where on the linker DNA the MNase would cut if the A/T motif closest to the core/linker junction is hidden inside the core.

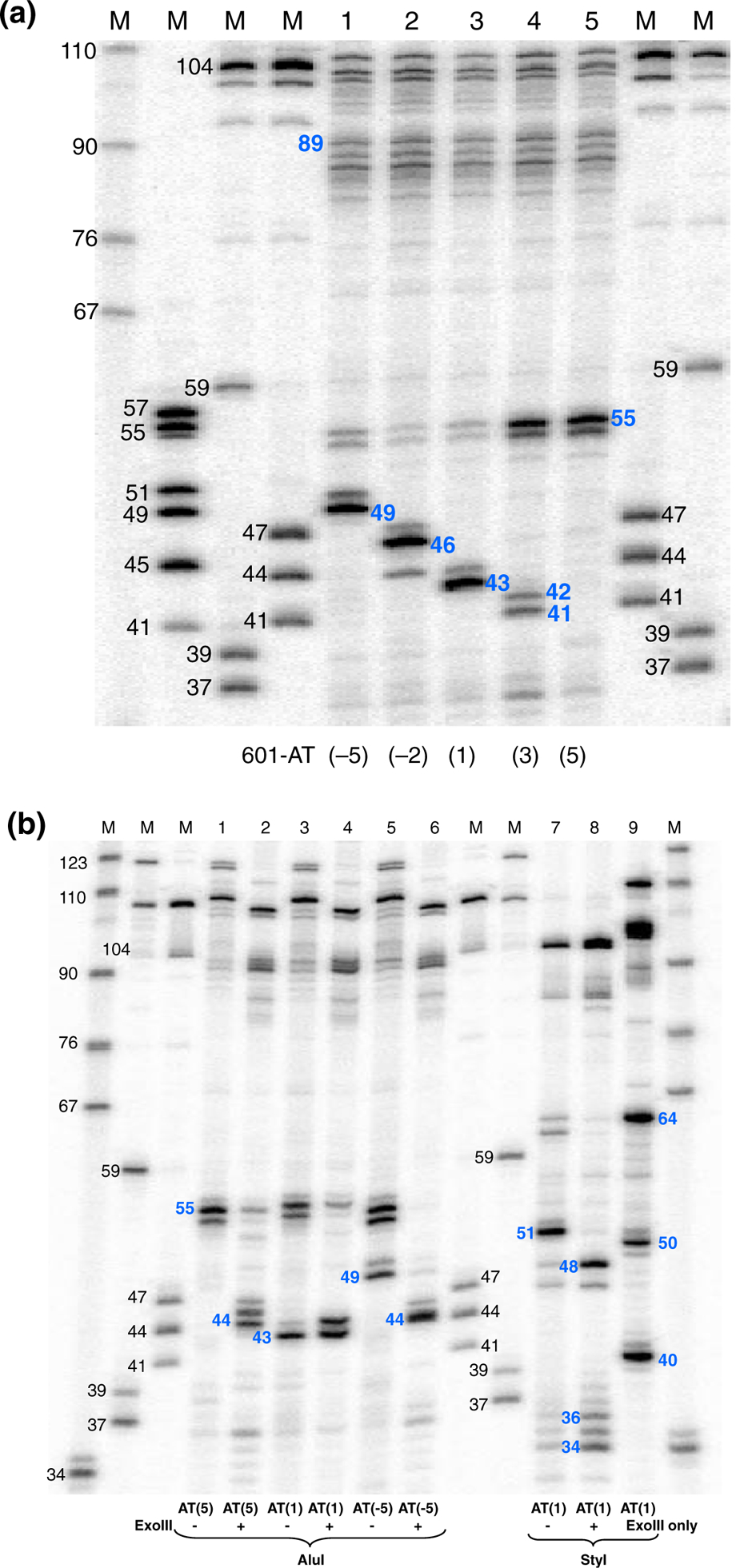

We reconstituted the nucleosomes, treated them with MNase under limited digestion conditions, and further cut the DNA with AccI to localize the positions of the MNase cuts in relation to the RE cuts. Band pattern on acrylamide gel shows that MNase produces DNA fragments of different length apparently originating from cutting at different locations in the left linkers, resulting in the longest total DNA fragment in the case of constructs 601-AT(5) and 601-AT(3) (Fig. S6a, lanes 1 and 2). In contrast, MNase has the same preferred cutting sites on the right linkers related to AccI (Fig. S6b), which share the same DNA sequence.

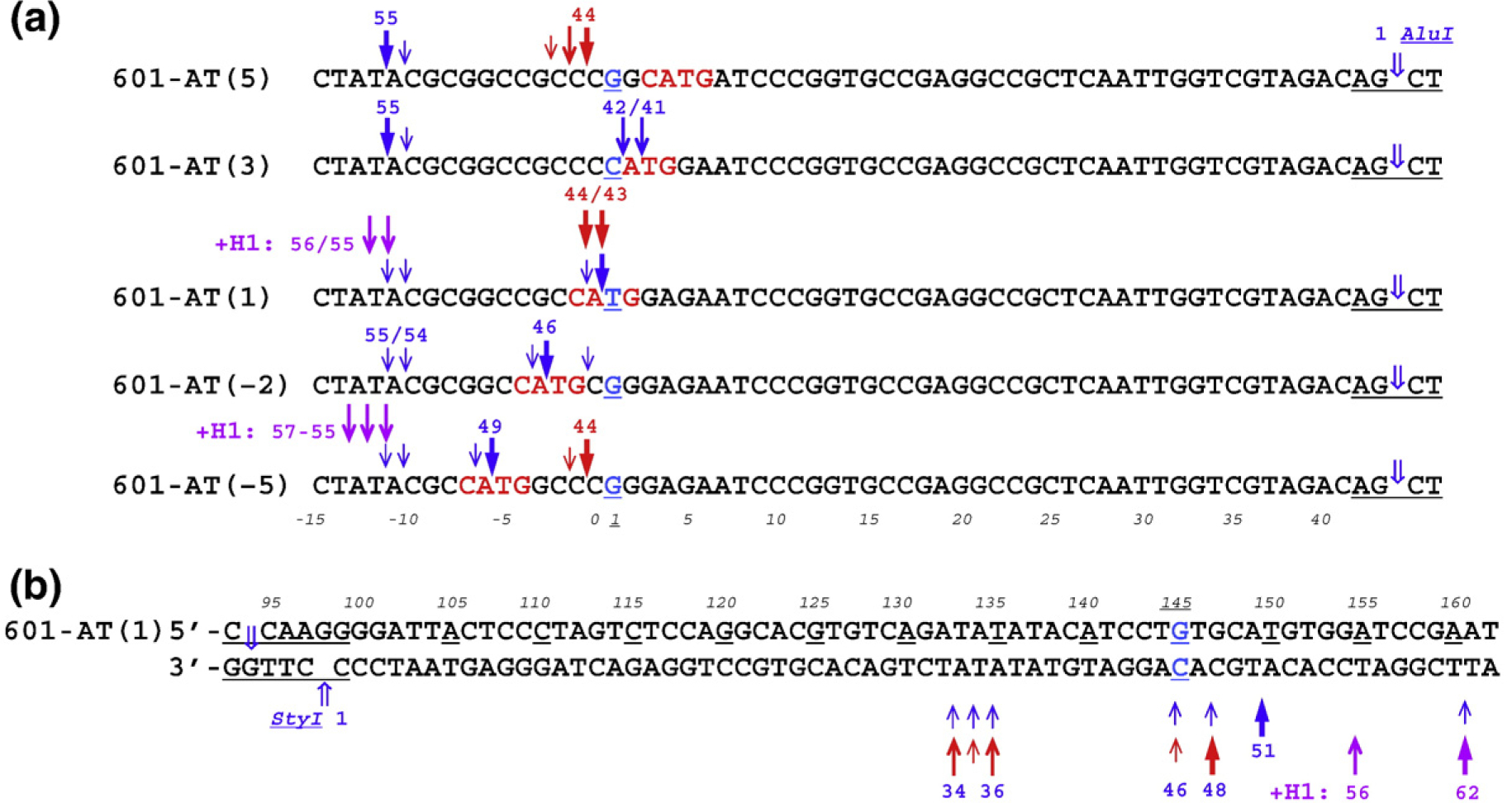

Precise locations of the MNase cuts in relation to AluI are shown on the high-resolution denaturing gel (Fig. 4a) and the corresponding digestion maps (Fig. 5). Remarkably, there is no cleavage at the left core/linker junction in nucleosome 601-AT(5). MNase cuts DNA at the 5′-end of the linker in the TAC motif, but the 14-nt G/C string remains practically intact. In the case of nucleosome 601-AT(3), in addition to the cuts at the 5′-end of the linker, MNase also produces two bands of 41 and 42 nt just inside the nucleosome core. In the nucleosome 601-AT(1), the MNase cleavage produces the 43-nt band (Fig. 5), which exactly corresponds to the end of nucleosome core observed in X-ray.36,37 Finally, in the nucleosomes 601-AT(− 2) and 601-AT(− 5), the MNase cuts, separated from AluI site by 46 and 49 nt, are located in the linker (Fig. 5). Bands of about 100 nt and longer in the upper part of the denaturing gel (Fig. 4a) show that all five nucleosomes are similarly cleaved close to the right core/linker junction (compare with Fig. S6b).

Fig. 4.

MNase and MNase/exoIII digestion of the nucleosomes containing CATG tetranucleotide at different positions in relation to the core/linker DNA junction. (a) MNase cleavage. MNase-digested DNA was purified, end labeled, digested with AluI, and separated on high-resolution 12% polyacrylamide-urea gel. Lanes 1 to 5 show DNA fragments from nucleosomes 601-AT(−5), 601-AT(−2), 601-AT(1), 601-AT(3), and 601-AT(5). The numbers in blue indicate the lengths (nucleotides) of the DNA fragments between AluI site and MNase cuts on the left linker. Lanes M, size markers obtained by RE digestion of the clone 601 DNA and pBR322 DNA. The numbers in black indicate the size (nucleotides) of calibration markers. (b) MNase or MNase/exoIII cleavage. Nucleosomes were digested with MNase and exoIII, and the digested DNA was purified, end labeled, digested with AluI or StyI, and separated on high-resolution 12% polyacrylamide-urea gel. Lanes 1 to 6 show DNA fragments from nucleosomes 601-AT(−5), 601-AT(1), and 601-AT(5) digested with or without addition of exoIII. Lanes 7 to 9 show DNA fragments from nucleosomes 601-AT(1) digested without (7) or with (8) addition of exoIII as well as with exoIII only (9). The numbers in blue indicate the lengths (nucleotides) of the DNA fragments between AluI site and cuts on the left linker and between StyI site and cuts on the right linker.

Fig. 5.

Location of MNase cuts and combined MNase/exoIII cuts on nucleosomes containing CATG tetranucleotide. (a) Diagrams showing the positions of cleavage sites at the left linkers of nucleosomes. Note that predominant cuts on all five nucleosomes by MNase (blue arrows) occur between A and T inside tetranucleotide CATG [601-AT(1), 601-AT(−2), and 601-AT(−5)] or at the 5′-end of the left linker in the TAC motif [601-AT(5) and 601-AT(3)]. The predominant cuts of combined MNase/exoIII cleavage (red arrows) occur between C and C in 601-AT(−5) and 601-AT(5), and between C and A and A and T in 601-AT(1). Numbers on the top indicate the size (nucleotides) of the fragments between the MNase (MNase/exoIII) and AluI cleavage sites. Numbers at the bottom (italic font) indicate nucleotide positions in the clone 601 nucleosome (cf. Fig. 1b). The size of the arrows is proportional to the intensity of MNase and MNase/exoIII cleavage. The MNase/exoIII cleavage in the presence of histone H1 is shown by purple arrows [601-AT(1) and 601-AT(−5)]. (b) Diagram showing the positions of cutting sites at the right linker of nucleosome 601-AT(1). Numbers at the bottom indicate the sizes (nucleotides) of the fragments between the MNase (MNase/exoIII) and StyI cleavage sites. Numbers on the top (italic font) indicate nucleotide positions in the clone 601 nucleosome (cf. Fig. 1d). Note that the predominant cut of combined MNase/exoIII cleavage is 3 nt closer to the core/linker junction (the underlined nucleotide #145) compared to the cut produced by MNase only (bands 48 and 51 nt, respectively). The purple arrows indicate MNase/exoIII cleavage in the presence of histone H1.

As expected, in all these constructs, the primary MNase cuts are located exactly between nucleotides A and T inside the CATG motif, with the secondary cuts located mostly between nucleotides C and A inside CATG. What we did not expect to see was that MNase stops as far away as 11 bp from the linker/core DNA junction and does not progress any further when no A·T pairs are present at any location closer to the core DNA [see 601-AT(5) in Figs. 4a and 5]. Another interesting result is that MNase cuts much more frequently at A/T nucleotides inside the core DNA than at G/C nucleotides on the linker DNA. As we discuss below, accessibility of A·T pairs for the MNase cleavage is likely to be defined by their rotational and translational position in the three-dimensional structure of the nucleosome core.

Combined MNase/exoIII treatment overcomes MNase sequence preference

To find out if we can get nucleosomal DNA digested at the core/linker junction independently of its sequence, we added exonuclease III (exoIII) during MNase treatment of reconstituted mononucleosomes. ExoIII digests the 3′-end of the nucleo somal DNA creating the 5′-overhang on the other DNA strand, which, as we expected, would be readily cleaved by MNase. The 601-AT(5), 601-AT(1), and 601-AT(−5) constructs were selected for this experiment because they have the CATG tetranucleotide positioned inside the core DNA, exactly at the core/linker junction and on the far left end of the linker, respectively (Fig. 1c). We treated mononucleosomes with MNase under limited digestion conditions while adding increasing amount of exoIII. We found that, after adding 20 units of exoIII into the digestion reaction, the sizes of released nucleosomal DNA were almost the same for all three constructs and close to the size of 601-AT(1) nucleosomal DNA (Fig. S7).

To find precise locations of the cuts, we analyzed the same material labeled on 5′-ends with 32P on the sequencing gel (Fig. 4b and Fig. S8). First, to test the sensitivity of the combined MNase/exoIII treatment to the enzyme concentrations, we digested nucleosomes with gradually increasing amount of exoIII in the reaction mixture under the “optimal” conditions selected above for MNase digestion (0.3 units of MNase per 1 μg of DNA) to produce nucleosome bands. As an example, Fig. S8 shows 601-AT(−5) nucleosomes digested with increasing concentration of exoIII, followed with digestion by RE and running on a sequencing gel. With all exoIII concentrations used, we see two major cuts on the left linker DNA, one at position 49, or 6 nt away from core/linker junction, and another one at positions 44/45, only 1 or 2 nt away from core/linker junction (Fig. S8, lanes 2–5). On the right linker, digestion with 10, 20, and 40 units of exoIII first produces cuts at the core/linker junction (position 48) followed with cutting inside the core DNA (Fig. S8, lanes 9–11). This result demonstrates that over the wide range of exoIII concentrations, the population of digested nucleosomes contains a significant amount of the DNA fragments trimmed close to the core/linker junctions, even for the G/C-rich linker sequences resisting the MNase cleavage (in the absence of exoIII).

We then mapped nucleosomes with three different sequences at the left linker. In the 601-AT(1) nucleosome with the CATG tetranucleotide positioned at the core/linker junction, the cuts originating from the combined nuclease cleavage and related to AluI cuts did not change compared to those produced by MNase only, except that now we see two major bands just upstream of the core boundary instead of one (Fig. 4b, lanes 3 and 4, and Fig. 5a, bands 44/43 nt). The other two nucleosomes acquire new strong cuts on the left linker adjacent to the core/linker junction where there are no cuts made by MNase only (Fig. 4b, lanes 1, 2, 5, and 6, and Fig. 5a, bands 44 nt).

As to the right linker, the strong cut on 601-AT(1) nucleosome is now 3 nt closer to the core/linker junction than it was when only MNase was used (see Fig. 4b, lanes 7 and 8, and Fig. 5b, bands 48 and 51 nt). The nucleosomes 601-AT(5) and 601-AT(−5) have the same cleavage pattern on the right linker related to StyI (data not shown).

Finally, we repeated MNase/ExoIII combined digestion experiments on two types of nucleosomes reconstituted with equimolar amount of linker histone H1, the chromatosome particles 601-AT(1) + H1 and 601-AT(−5) + H1 (Fig. 1b). We digested the mononucleosomes (−H1) and chromatosomes (+H1) with MNase plus exoIII, labeled the DNA, digested them with RE, and ran them on a sequencing gel (Fig. S9). We observed that in both cases, addition of linker histone has led to complete protection of the nucleosome linker/core junctions independent of the underlying DNA sequence. With these nucleosomes, histone H1 appeared to confer a strong though not precisely symmetric protection of 11–12 bp on the left linker and 8–10 bp on the right linker (see purple arrows in Fig. 5).

Overall, our results suggest that the combined MNase and exoIII treatment of nucleosomes is practically insensitive to the DNA sequence at the core/linker junction, producing a 147-bp nucleosome core (Fig. 5) with the 5′-ends symmetrically located versus the nucleosome dyad, which makes it perfectly suited for mapping precise nucleosome positions.

Discussion

Relationship of the in vitro mapping to the nucleosome X-ray crystal structure

X-ray crystallography has established the nucleosome core as a pseudo-symmetric structure where the helical twist of DNA may slightly vary to accommodate various DNA sequences (both symmetric and asymmetric). In clone 601 nucleosome core crystals, for example, the asymmetric DNA is slightly stretched and overtwisted36,37 so that 145 bp occupy the same space on the histone octamer as 147 bp of symmetric α-satellite DNA.38 The precise length of DNA associated with the histone core in solution is not known. Solving the X-ray crystal structure of the clone 601 nucleosomes36,37 positioned with a single-nucleotide precision in vitro29,30 provided an excellent opportunity to compare high-resolution MNase mapping with X-ray data.

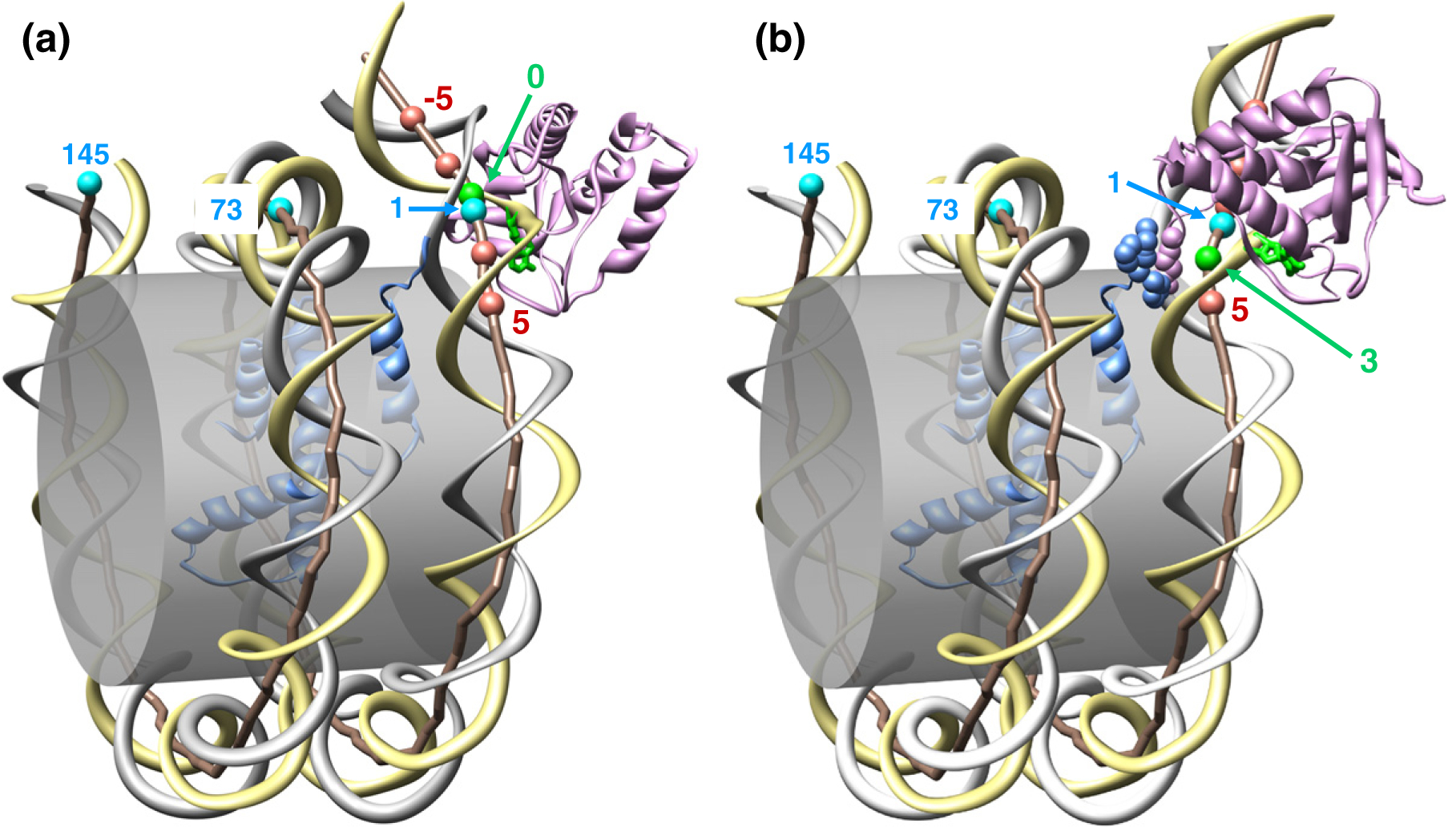

Our previous data32 showed that the uniquely positioned clone 601 nucleosome displayed a notably asymmetric MNase protection that did not match the positions of the core/linker junctions expected based on the X-ray structures.36,37 We realized, however, that MNase digestion of the clone 601 mononucleosomes released DNA fragments whose sizes were strongly influenced by position of the A·T pair closest to the core/linker junction (Figs. 3a and 5a). We built several spatial models showing MNase associated with the cleavable DNA positions on the nucleosome (Fig. 6 and Fig. S10). The modeling shows that in the two out of three constructs with complete digestion at the CATG motif, 601-AT(−5) and 601-AT(1), the MNase digesting these bonds is positioned in such a way that there is no spatial clash between the enzyme and the nucleosome (Figs. S10b and d). In the third construct with complete digestion at the CATG, 601-AT(−2), the MNase faces the nucleosome core, but a moderate bending of the linker DNA (known to be flexible) is sufficient to relieve the clash (Fig. S10c). In the 601-AT(3) where MNase digestion is partially inhibited, the enzyme is in close contact with the H3 histone, which is likely to be relieved by a local rearrangement of the histone N-tail (Fig. 6b and Fig. S10e). Finally, in the 601-AT(5), the position of MNase necessary for the DNA cleavage at this point is sterically impossible due to strong clashes between the enzyme and the next turn of DNA in the nucleosome (Fig. S10f), resulting in a complete protection of the CATG motif from the MNase (Fig. 5a). It thus appears that our MNase digestion map of the nucleosome 601 in vitro is entirely consistent with its X-ray crystal structures.36,37

Fig. 6.

Stereochemical models for MNase associated with the 601 nucleosomal DNA. The crystal structure of nucleosome 601 [33] is shown schematically: the gray cylinder represents the surface of histone octamer. The yellow ribbon denotes the W-strand; the gray ribbon is for the C-strand. The DNA axis is shown as a brown rod connecting the centers of WC pairs, with the balls representing selected positions; the numbering scheme is the same as in Fig. 1. MNase (shown in pink) is bound to the W-strand; DNA is cleaved at the 5′-end of the flipped-out base (shown in green). In (a), the flipped-out base is in position 0 (see Fig. 5a, the arrows marked 44); in (b), the cleavage occurs at position 3 [see 601-AT(3) in Fig. 5a, the arrow marked 41]. Note that in (a), there is no contact between MNase and the histone octamer, whereas in (b), the MNase loop is in direct contact with the N-tail of histone H3 (shown in blue); see the main text for details. Molecular modeling of MNase binding to DNA is briefly described in Fig. S11.

Chromatosome protection by linker histone H1 and other architectural factors

Our work also demonstrates that the apparent length of nucleosome linker protection by histone H1 is affected by the sequence of the linker DNA when it is probed by MNase digestion assay. Initially, it was shown that digestion of random-sequenced native chromatin by MNase produces a characteristic pause site of about 165 bp that was attributed to protection of two 10-bp linker DNA segments by linker histone H1 and called the chromatosome.34 However, mapping of unique sequence chromatosomes reconstituted with linker histone by MNase leads to a controversy whether linker histone protects 20 bp on one out of two linkers in a nucleosome reconstituted from 5S rDNA35 or symmetrically protects about 10–11 bp of DNA on each side of the nucleosome reconstituted from clone 601.32 Symmetric protection by linker histone was confirmed in independent experiments with hydroxyl radical mapping of clone 601 nucleosome,30 suggesting that the sequence difference between the 5S DNA and clone 601 could result in the different modes of MNase mapping.

Here, we found that in clone 601 nucleosomes reconstituted with linker histone, MNase digests the two linkers independently of each other and the precise MNase cutting positions are heavily influenced by the MNase preference for AT-rich sequences. As can be seen on Fig. 2c, the pattern of bands generated by MNase is the same, with or without H1; only the band intensities are different. This indicates that the MNase attacks DNA at preferred cutting sites if they are exposed and not shielded by bound proteins, in this case linker histone H1. When an MNase-digested nucleosome construct, for example, the 601-wt nucleosome, has A·T pairs in the two linkers at equal distance (~10 bp) from the core/linker junctions, then both nucleosome ends are equally protected by the linker histone (Fig. 2c), resulting in a symmetric chromatosome. If, however, one of the two DNA linkers contains a long string of G/C nucleotides proximal to the core, then this linker would not be digested, creating a resemblance of asymmetric chromatosome.

It thus appears that the precise positioning of A·T pairs in the linker DNA should be considered when designing a mononucleosome template suitable for studies of the linker DNA protection by architectural factors.

Problems with deducing the nucleosome dyad positions from the MNase digestion

In the past years, massive parallel sequencing of MNase-digested nuclear chromatin allowed obtaining millions of genome-wide nucleosomal DNA sequence reads and mapping them to genomes. In the existing approaches, the nucleosome dyad positions are allocated at the midpoint of 145- to 150-bp-long nucleosomal core DNA.1,3,8 While the preference of MNase for A·T pairs has been long known, the question of whether this bias could significantly affect nucleosome position maps remains a matter of discussion.23,24,26

Based on our studies with reconstituted clone 601 nucleosome, we suggest that due to its strong sequence preference, the MNase digestion generates several types of artifacts that may significantly affect precise positioning of the nucleosome dyad for certain nucleosomes. Indeed, multiple examples of nucleosome mapping from yeast to human showed a dramatic preference for A·T pairs at the ends of the digested nucleosomal DNA.5,39,40 For a “random” sequence with 50% A/T nucleotides, seven out of eight nucleosomes are expected to have an A·T pair within 1 nt of the core/linker junction and to be cleaved by MNase without a significant bias. Our experiments show, however, that nucleosomes with GC-rich patches at the core/linker junctions will be digested to DNA fragments of 150 bp or longer and might be excluded from analysis or will be underrepresented in the whole population of mononucleosomal sequences; in the latter case, a “dominant position” might be assigned to a wrong nucleosome frame. The number of recovered DNA fragments might not be proportional to the actual nucleosome occupancy due to different affinity of MNase to AT-rich and GC-rich DNA. The ability of MNase to cut inside nucleosomal DNA, coupled with cuts on the linker DNA rather than at the edge of nucleosomal core, will generate fragments that do not represent true genomic positions of nucleosomes with GC-rich core/linker junctions. Overall, the MNase sequence bias is relatively insignificant for mapping nucleosomes in the AT-rich yeast genome, but for the higher eukaryotes whose genomes contain GC-rich regions, the MNase bias represents a more serious problem.

This conclusion is consistent with recent nuclease mapping of in vitro reconstituted nucleosomes by Allan et al.26 who used two genomic sequences, one from sheep and another from yeast. In both cases, the MNase-derived DNAs had the peaks at 149, 159, and 168 bp in the length distribution. Importantly, the GC-rich sheep sequences were characterized by longer nucleosomal DNA fragments, predominantly 159 bp long, compared to 149 bp for the AT-rich yeast sequences (Fig. 3 in Ref. 26). This result agrees with our data indicating that GC-rich linkers are under-digested by MNase (Fig. 3a).

Our mapping is also consistent with the A/T DNA preference by MNase for native nucleosome positioning sequences of Lytechinus variegatus 5S rDNA with several preferred nucleosome positioning frames.41 However, a precise mapping of the MNase cut sites in relation to the nucleosome core/linker junction on 5S rDNA nucleosomes is not feasible due to lack of X-ray crystal core structural data and several competing nucleosome positions due to translational variations in the 5S rDNA nucleosomes. In the future, it would be interesting to apply the high-resolution MNase/exoIII approach in combination with chemical mapping of the dyad axis position42 to determine precise core/junction positions in native nucleosomes with distinct positional variations.

For native nucleosomes, the accessibility of the nucleosome ends to MNase and precise positions of nucleosome core/linker junctions may be sensitive to specific sequences promoting transient DNA unwrapping43 as well as histone variants such as histone CENPA44 or H2A.Bbd45 that do not constrain the terminal segments of the nucleosome core. Future studies with nucleosomes reconstituted from modified clone 601 DNA sequences and histone variants should allow developing optimized nuclease digestion conditions for studies of specific nucleosomes with altered DNA-histone affinity.

MNase/exoIII digestion increases precision of nucleosome positioning

Several different methodologies for mapping nucleosomes in addition to the MNase digestion have been proposed. One such example is the chemical mapping recently developed by Brogaard et al.46 This approach is not easily applicable to the higher eukaryotes, however, as it demands special genetically modified organisms. In some earlier works, the MNase digestion was used as a first step in obtaining mononucleosomes that were further digested with exonuclease III trimming the 3′-hydroxyl termini of duplex DNA.47–51 After removal of the opposite single strand with nuclease S1, the resulting DNA produced bands with ~10 bp length periodicity.52

In this work, we found that a surprisingly simple experimental approach combining the MNase and exoIII treatment is very efficient in overcoming the MNase sequence preference. Addition of exonuclease III into digestion reaction resulted in a major change in the sites where the linker DNA is cut. Now, instead of having major cuts at the A·T pairs, as it was with the MNase-only digestion, DNA is cut predominantly within 1 nt from the core/linker junction defined by X-ray crystallography (Figs. 5 and 6a). In other words, the nucleosomal DNA is now cut symmetrically, with the two MNase cuts at the 5′-ends being separated by 147 bp, which is merely 2 bp longer than the core DNA defined by X-ray crystallography.

It was shown earlier49,52 that exoIII could remove dozens of nucleotides at each 3′-end of the core particle. Our data also indicate that exoIII cuts as much as 24 nt inside the 601 core DNA (not shown). Strikingly, this “intrusion” of exoIII inside core DNA did not eliminate specific MNase cuts on the opposite strand at the core/linker junction (Fig. 5). This observation is critical for the parallel sequencing of the nucleosomal DNA fragments. The current strategy17,53,54 implies filling in the 5′-overhangs and removing the 3′-overhangs; thus, from a practical point of view, it is not essential how extensively exoIII penetrates the core DNA at the 3′-end. It is important, however, that the MNase/exoIII cleavage produces DNA fragments with their 5′-ends located symmetrically relative to the core/linker junctions, thereby allowing determination of the nucleosome dyad position with single-nucleotide accuracy. Therefore, combined MNase/exoIII digestion can be applied to in situ chromatin for a more precise genome-wide mapping of the nucleosome positions that is not influenced by DNA sequence at the core/linker junction. We propose that the same approach can be used for precise mapping of the extent of linker DNA protection by H1 and other protein factors associated with nucleosome linkers.

Materials and Methods

DNA constructs preparation

DNA templates were designed using clone 601 DNA28 and adding modified sequences of the linker DNA (Fig. 1b–d). DNA sequence for the nucleosome 601-wt (178 bp) was derived from the 207-bp template described in Nikitina et al.55 Plasmids with inserts 601-TT and 601-GC were prepared by cutting off DNA fragment between XbaI and MfeI (cat# R0145S, R0589S; New England BioLabs) restriction sites from 601-wt (inserted in the pUC19 plasmid) DNA followed by ligation of 75-bp DNA fragments purchased from IDT using standard procedures. Ligation products were used to transform MaxEfficiency DH5a cells (cat# 18258012; Invitrogen), transformants were grown, and plasmid DNA was prepared using Plasmid purification kit (cat# 27104; Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

DNA fragments 601-AT(−5), 601-AT(−2), 601-AT(1), 601-AT(3), and 601-AT(5) were prepared by PCR-directed mutagenesis using 601–207 plasmid as a template. High-pressure liquid chromatography-purified forward and reverse primers for plasmid preparation were purchased from IDT. Each newly prepared DNA fragment was digested with RE NlaIII (cat# R0125S; New England BioLabs) to verify the presence of CATG tetranucleotide. The PCR primers are listed in Table S1.

We prepared 178-bp inserts 601-wt, 601-TT, and 601-GC by standard PCR amplification reaction using corresponding plasmid as templates. High-pressure liquid chromatography-purified forward and reverse primers for PCR reactions were purchased from IDT.

Each PCR amplification product was run and 1% agarose gel bands corresponding to amplified DNA were cut off, DNA extracted, and purified using Wizard SV Gel and PCR Clean-Up System (cat# A9281; Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Nucleosome preparation

Nucleosomes were prepared by mixing purified chicken erythrocyte core histones isolated as described previously41,56 except that gradient dialysis from 2.0 NaCl to 250 mM NaCl was used for reconstitution, followed by dialysis to 50 mM NaCl. Reconstituted nucleosomes were tested on 6% native polyacrylamide gel (cat# EC6365BOX; Invitrogen) in 0.5× TBE gel electrophoresis buffer.

Oligonucleosome templates and reconstitutions

The 601-wt(207×12) template was described previously.55 The 601-AT(207×12) and 607-GC(207×12) templates were first designed as monomers with the length of the linker DNA altered through primer modification PCR. Monomeric templates were tandemly repeated by serial subcloning to result in 12-mer repeats and reconstituted with chicken erythrocyte histones to produce 12-mer oligonucleosome arrays essentially as previously described.14

Nucleosome reconstitution with linker histone

Nucleosomes were incubated with human H10 (cat# M2501S; New England BioLabs) at a molar ratio of 1:1 for 30 min at 23 °C in buffer containing 50 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 10% Ficoll (cat# F5415; Sigma), and 0.025% Nonidet P-40 (cat# NC9168253; Fisher Scientific). H10 binding was assayed by band-shift analysis in native 1% agarose gels (Type IV, cat# A3643; Sigma) in 20 mM Hepes, pH 8.0, and 0.2 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid.

MNase, exoIII, and restriction nuclease digestion

Nucleosomes only or nucleosomes incubated with H10 were digested with 0.3 units of MNase (Nuclease S7 Micrococcal Nuclease, cat# 10107921001; Roche Applied Science) per 1 μg of DNA for 10 min at 22 °C in the presence of 0.7 mM CaCl2. In the case when exoIII (cat# M0206S; New England BioLabs) was used in combination with MNase, the same buffer was supplemented with 2 mM MgCl2 and 20 units of exoIII per 1 μg of DNA was added to the digestion reaction. For titration experiment, we used 0.3 units of MNase with digestion time ranging from 15 s to 20 min and 1.0 unit of MNase for 20 min. For titration with exoIII, we used 10, 20, 40, and 60 units of exoIII per 1 μg of DNA. To stop the reaction, we added 10 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid and placed the samples on ice for 5 min. Samples were treated with 10% SDS and 0.2 mg/ml proteinase K (cat# 1373196; Roche Applied Science) for 1 h at 55 °C and cleaned with Wizard SV Gel and PCR Clean-Up System. DNA was further digested with REs AccI and StyI (cat# R0161S, R3500S; New England Biolabs) and treated with 10% SDS for 20 min at 37 °C.

Non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

Loading buffer (30 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.0, 1% SDS, 5% sucrose, 2.5% mercaptoethanol, and 0.005% bromophenol blue) was added to digested DNA; samples were applied to SDS discontinuous polyacrylamide gel (6% stacking gel, 13% resolving gel, 35:1 acrylamide:bis) and run for 5 h at a constant current of 24 mA. The gels were stained with GelRed (cat# 41002; Biotium Inc.).

Denaturing high-resolution gel electrophoresis

Isolated MNase-digested DNA or MNase/exoIII-digested DNA was 5′-end labeled with 32P using T4 Kinase (cat# 18004–010; Invitrogen), purified by phenol–chloroform extraction, and run through Illustra MicroSpin G-50 columns (cat# 28917923; GE Health-care). The radioactive samples were further digested with AluI (cat# R0137S; New England Biolabs) or StyI, mixed (3:2 w/w) with sequencing stop solution (cat# EC-848; National Diagnostic), and separated on 40-cm-long 12% polyacrylamide/urea “sequencing” gels. Samples digested with exoIII without MNase were labeled with 32P after digestion with REs. The gels were dried and exposed to a PhosphoImager (Amersham Biosciences) for autoradiography.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to David Clark and Hope Cole for valuable discussion of the conditions used for the combined MNase/exoIII digestion and to Igor Panyutin and M. Onyshchenko for help with high-resolution gels. This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research (V.B.Z.), and by National Science Foundation grant MCB-1021681 (S.A.G.).

Abbreviations used:

- MNase

micrococcal nuclease

- RE

restriction enzyme

Footnotes

Supplementary Data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jmb.2013.02.026

References

- 1.Segal E, Fondufe-Mittendorf Y, Chen L, Thastrom A, Field Y, Moore IK et al. (2006). A genomic code for nucleosome positioning. Nature, 442, 772–778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Albert I, Mavrich TN, Tomsho LP, Qi J, Zanton SJ, Schuster SC & Pugh BF (2007). Translational and rotational settings of H2A.Z nucleosomes across the Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome. Nature, 446, 572–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang Z & Pugh BF (2011). High-resolution genome-wide mapping of the primary structure of chromatin. Cell, 144, 175–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaplan N, Moore IK, Fondufe-Mittendorf Y, Gossett AJ, Tillo D, Field Y et al. (2009). The DNA-encoded nucleosome organization of a eukaryotic genome. Nature, 458, 362–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Valouev A, Johnson SM, Boyd SD, Smith CL, Fire AZ & Sidow A (2011). Determinants of nucleosome organization in primary human cells. Nature, 474, 516–520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang Y, Moqtaderi Z, Rattner BP, Euskirchen G, Snyder M, Kadonaga JT et al. (2009). Intrinsic histone–DNA interactions are not the major determinant of nucleosome positions in vivo. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 16, 847–852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mavrich TN, Jiang C, Ioshikhes IP, Li X, Venters BJ, Zanton SJ et al. (2008). Nucleosome organization in the Drosophila genome. Nature, 453, 358–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stein A, Takasuka TE & Collings CK (2010). Are nucleosome positions in vivo primarily determined by histone–DNA sequence preferences? Nucleic Acids Res. 38, 709–719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sahu G, Wang D, Chen CB, Zhurkin VB, Harrington RE, Appella E et al. (2010). p53 binding to nucleosomal DNA depends on the rotational positioning of DNA response element. J. Biol. Chem 285, 1321–1332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cole HA, Tabor-Godwin JM & Hayes JJ (2010). Uracil DNA glycosylase activity on nucleosomal DNA depends on rotational orientation of targets. J. Biol. Chem 285, 2876–2885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Song Q, Cannistraro VJ & Taylor JS (2011). Rotational position of a 5-methylcytosine-containing cyclobutane pyrimidine dimer in a nucleosome greatly affects its deamination rate. J. Biol. Chem 286, 6329–6335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Widom J (1992). A relationship between the helical twist of DNA and the ordered positioning of nucleosomes in all eukaryotic cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 89, 1095–1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Woodcock CL, Grigoryev SA, Horowitz RA & Whitaker N (1993). A chromatin folding model that incorporates linker variability generates fibers resembling the native structures. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 90, 9021–9025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Correll SJ, Schubert MH & Grigoryev SA (2012). Short nucleosome repeats impose rotational modulations on chromatin fibre folding. EMBO J. 31, 2416–2426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sasaki S, Mello CC, Shimada A, Nakatani Y, Hashimoto S, Ogawa M et al. (2009). Chromatin-associated periodicity in genetic variation downstream of transcriptional start sites. Science, 323, 401–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen X, Chen Z, Chen H, Su Z, Yang J, Lin F et al. (2012). Nucleosomes suppress spontaneous mutations base-specifically in eukaryotes. Science, 335, 1235–1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cole HA, Howard BH & Clark DJ (2011). Activation-induced disruption of nucleosome position clusters on the coding regions of Gcn4-dependent genes extends into neighbouring genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, 9521–9535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pauli UH, Seebeck T & Braun R (1982). Sequence-specific cleavage of chromatin by staphylococcal nuclease can generate an atypical nucleosome pattern. Nucleic Acids Res. 10, 4121–4133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Axel R (1975). Cleavage of DNA in nuclei and chromatin with staphylococcal nuclease. Biochemistry, 14, 2921–2925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dingwall C, Lomonossoff GP & Laskey RA (1981). High sequence specificity of micrococcal nuclease. Nucleic Acids Res. 9, 2659–2673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cockell M, Rhodes D & Klug A (1983). Location of the primary sites of micrococcal nuclease cleavage on the nucleosome core. J. Mol. Biol 170, 423–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McGhee JD & Felsenfeld G (1983). Another potential artifact in the study of nucleosome phasing by chromatin digestion with micrococcal nuclease. Cell, 32, 1205–1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson SM, Tan FJ, McCullough HL, Riordan DP & Fire AZ (2006). Flexibility and constraint in the nucleosome core landscape of Caenorhabditis elegans chromatin. Genome Res. 16, 1505–1516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chung HR, Dunkel I, Heise F, Linke C, Krobitsch S, Ehrenhofer-Murray AE et al. (2010). The effect of micrococcal nuclease digestion on nucleosome positioning data. PLoS One, 5, e15754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weiner A, Hughes A, Yassour M, Rando OJ & Friedman N (2010). High-resolution nucleosome mapping reveals transcription-dependent promoter packaging. Genome Res. 20, 90–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Allan J, Fraser RM, Owen-Hughes T & Keszenman-Pereyra D (2012). Micrococcal nuclease does not substantially bias nucleosome mapping. J. Mol. Biol 417, 152–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Satchwell SC, Drew HR & Travers AA (1986). Sequence periodicities in chicken nucleosome core DNA. J. Mol. Biol 191, 659–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lowary PT & Widom J (1998). New DNA sequence rules for high affinity binding to histone octamer and sequence-directed nucleosome positioning. J. Mol. Biol 276, 19–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morozov AV, Fortney K, Gaykalova DA, Studitsky VM, Widom J & Siggia ED (2009). Using DNA mechanics to predict in vitro nucleosome positions and formation energies. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, 4707–4722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Syed SH, Goutte-Gattat D, Becker N, Meyer S, Shukla MS, Hayes JJ et al. (2010). Single-base resolution mapping of H1-nucleosome interactions and 3D organization of the nucleosome. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 107, 9620–9625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thastrom A, Bingham LM & Widom J (2004). Nucleosomal locations of dominant DNA sequence motifs for histone–DNA interactions and nucleosome positioning. J. Mol. Biol 338, 695–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grigoryev SA, Arya G, Correll S, Woodcock CL & Schlick T (2009). Evidence for heteromorphic chromatin fibers from analysis of nucleosome interactions. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 106, 13317–13322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tan S & Davey CA (2011). Nucleosome structural studies. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol 21, 128–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Clarke MF, FitzGerald PC, Brubaker JM & Simpson RT (1985). Sequence-specific interaction of histones with the simian virus 40 enhancer region in vitro. J. Biol. Chem 260, 12394–12397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.An W, Leuba SH, Van Holde K & Zlatanova J (1998). Linker histone protects linker DNA on only one side of the core particle and in a sequence-dependent manner. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 95, 3396–3401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Makde RD, England JR, Yennawar HP & Tan S (2010). Structure of RCC1 chromatin factor bound to the nucleosome core particle. Nature, 467, 562–566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu B, Mohideen K, Vasudevan D & Davey CA (2010). Structural insight into the sequence dependence of nucleosome positioning. Structure, 18, 528–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Richmond TJ & Davey CA (2003). The structure of DNA in the nucleosome core. Nature, 423, 145–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cui F & Zhurkin VB (2009). Distinctive sequence patterns in metazoan and yeast nucleosomes: implications for linker histone binding to AT-rich and methylated DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, 2818–2829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Valouev A, Ichikawa J, Tonthat T, Stuart J, Ranade S, Peckham H et al. (2008). A high-resolution, nucleosome position map of C. elegans reveals a lack of universal sequence-dictated positioning. Genome Res. 18, 1051–1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Meersseman G, Pennings S & Bradbury EM (1991). Chromatosome positioning on assembled long chromatin. Linker histones affect nucleosome placement on 5S rDNA. J. Mol. Biol 220, 89–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Panetta G, Buttinelli M, Flaus A, Richmond T & Rhodes D (1998). Differential nucleosome positioning on xenopus oocyte and somatic 5S RNA genes determines both TFIIIA and HI binding: a mechanism for selective H1 repression. J. Mol. Biol 282, 683–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Anderson JD & Widom J (2000). Sequence and position-dependence of the equilibrium accessibility of nucleosomal DNA target sites. J. Mol. Biol 296, 979–987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tachiwana H, Kagawa W, Shiga T, Osakabe A, Miya Y, Saito K et al. (2011). Crystal structure of the human centromeric nucleosome containing CENP-A. Nature, 476, 232–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tolstorukov MY, Goldman JA, Gilbert C, Ogryzko V, Kingston RE & Park PJ (2012). Histone variant H2A.Bbd is associated with active transcription and mRNA processing in human cells. Mol. Cell, 47, 596–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brogaard K, Xi L, Wang JP & Widom J (2012). A map of nucleosome positions in yeast at base-pair resolution. Nature, 486, 496–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Riley D & Weintraub H (1978). Nucleosomal DNA is digested to repeats of 10 bases by exonuclease III. Cell, 13, 281–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Igo-Kemenes T, Omori A & Zachau HG (1980). Non-random arrangement of nucleosomes in satellite I containing chromatin of rat liver. Nucleic Acids Res. 8, 5377–5390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Prunell A & Kornberg RD (1978). Relation of nucleosomes to nucleotide sequences in the rat. Philos. Trans. R. Soc., B, 283, 269–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Strauss F & Prunell A (1982). Nucleosome spacing in rat liver chromatin. A study with exonuclease III. Nucleic Acids Res. 10, 2275–2293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Strauss F & Prunell A (1983). Organization of internucleosomal DNA in rat liver chromatin. EMBO J. 2, 51–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Prunell A (1983). Periodicity of exonuclease III digestion of chromatin and the pitch of deoxyribonucleic acid on the nucleosome. Biochemistry, 22, 4887–4894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Henikoff JG, Belsky JA, Krassovsky K, MacAlpine DM & Henikoff S (2011). Epigenome characterization at single base-pair resolution. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 108, 18318–18323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kent NA, Adams S, Moorhouse A & Paszkiewicz K (2011). Chromatin particle spectrum analysis: a method for comparative chromatin structure analysis using paired-end mode next-generation DNA sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, e26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nikitina T, Ghosh RP, Horowitz-Scherer RA, Hansen JC, Grigoryev SA & Woodcock CL (2007). MeCP2–chromatin interactions include the formation of chromatosome-like structures and are altered in mutations causing Rett syndrome. J. Biol. Chem 282, 28237–28245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Springhetti EM, Istomina NE, Whisstock JC, Nikitina TV, Woodcock CL & Grigoryev SA (2003). Role of the M-loop and reactive center loop domains in the folding and bridging of nucleosome arrays by MENT. J. Biol. Chem 278, 43384–43393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.