Abstract

Background

Pancreatic cancer (PC) is a common digestive system tumor. For patients with advanced pancreatic cancer (APC), chemotherapy is still the predominant treatment. However, no large-scale clinical studies have been done of it as first-line therapy for APC. The goal of the present study was to assess real-world outcomes with chemotherapy in that setting.

Material/Methods

We retrospectively analyzed data from 322 patients with APC who were treated with chemotherapy at 4 hospitals in different cities in China. The first-line regimens used were AS (nab-paclitaxel and S-1), AG (nab-paclitaxel and gemcitabine), and FOLFIRINOX (5-fluorouracil, leucovorin, irinotecan, and oxaliplatin).

Results

Of the patients, 232 received AS, 79 received AG, and 11 received FOLFIRINOX. The median number of chemotherapy cycles was 5. The median overall survival (mOS) was 9 months and the median progression-free survival (mPFS) was 5 months. The AS, AG, and FOLFIRINOX regimens were associated with mOS rates of 9 months, 9 months, and 10 months, respectively. The mPFS rates for the AS, AG, and FOLFIRINOX regimens were 5, 4, and 5 months, respectively. The differences between the PFS rates for the regimens were statistically significant. The overall response rate (ORR) and overall disease control rate (DCR) for chemotherapy were 38% and 81.8%, respectively. The ORRs for the AS, AG, and FOLFIRINOX regimens were 46.9%, 18.7%, and 0%, respectively. The DCRs for the AS, AG and FOLFIRINOX regimens were 87.2%, 69.3%, and 63.6%, respectively. The differences between the ORRs and DCRs for the regimens were statistically significant. The incidences of grade 3/4 adverse events (AEs) associated with the AS, AG, and FOLFIRINOX regimens were 29.9%, 25%, and 36.4%, respectively.

Conclusions

The AS regimen was associated with a higher ORR and DCR than the other 2 regimens, with a lower rate of AEs.

MeSH Keywords: Antineoplastic Agents, Drug-Related Side Effects and Adverse Reactions, Pancreatic Neoplasms

Background

Pancreatic cancer (PC) is an aggressive and lethal malignant solid tumor. The fourth most common cause of cancer-related death, it is associated with a 5-year survival rate of only 5%, even in patients who undergo curative surgery or are treated with chemotherapy and radiation therapy [1]. Estimates indicate that by 2030, PC will become the second leading cause of cancer death in the United States [2]. In 2018, it was estimated that there would be 458 918 new cases of cancer and 432 242 deaths from the disease worldwide [3]. Furthermore, for unknown reasons, the morbidity associated with PC is increasing globally. Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma is the most common type of PC, accounting for 90% of cases.

The incidence of PC is highest in East Asia, North America, and Eastern Europe. More than one-third of all new diagnoses occur in East Asia. In China, it is ranked ninth and sixth, respectively, in morbidity and mortality from PC. In 2018, 116 300 new cases and 110 400 deaths due to PC – or one-quarter of those in the world – occurred in China, making it the country most affected by the disease. Some patients with early-stage PC undergo radical surgery, but their survival rates are not very high, and most of them go on to experience recurrence or disease progression. Early detection of PC is hindered by a lack of visible symptoms and biomarkers [1,4], which is why more than 50% of patients with it are diagnosed at an advanced stage and have poor prognoses. Chemotherapy remains the optimal treatment for the majority of individuals who have advanced PC at diagnosis or whose disease relapses after surgery.

Unfortunately, few drugs have been shown to be effective against advanced PC (APC). In 2011, Conroy et al. demonstrated that in patients with metastatic PC, FOLFIRINOX (5-fluorouracil, leucovorin, irinotecan, and oxaliplatin) was associated with a median overall survival (OS) of 11.1 months versus 6.8 months for gemcitabine, a statistically significant difference. Therefore, FOLFIRINOX became the standard first-line regimen for patients with APC [5]. However, no individuals older than age 75 years were included in the 2011 study. A single-center, retrospective analysis indicated that for patients with APC who are older than age 75 years, the use of modified FOLFIRINOX had efficacy similar to that in younger patients [6]. A phase 3 study by Von Hoff et al., published in 2013, demonstrated an improved OS of 8.5 months in patients given gemcitabine and nab-paclitaxel (AG), compared with 6.7 months for gemcitabine alone, establishing the AG regimen as another option for first-line chemotherapy [7]. In the phase 3 JASPAC01 and GEST trials, rates of chemotherapy-related adverse events (AEs), and especially hematologic toxicity, were lower in patients who received S-1 monotherapy than in those treated with gemcitabine alone [8,9]. Another phase 2 clinical trial indicated that nab-paclitaxel plus S-1 (AS) produced an encouraging overall response rate (ORR) of 50% and was associated with manageable toxicities. The median progression-free survival (mPFS) and median OS (mOS) rates for AS were 5.6 months and 9.4 months, respectively [10].

No large-scale clinical study has been performed of first-line chemotherapy for APC. Therefore, there is an urgent need to explore real-world experience with chemotherapy in this clinical setting. In this retrospective, multicenter study, we evaluated the effects of the 3 predominant regimens – AS, AG, and FOLFIRINOX – on outcomes of patients with APC in China.

Material and Methods

Study design and patients

Included in the study were 322 patients who received first-line chemotherapy with AS, AG, or FOLFIRINOX for APC at the Chinese PLA General Hospital (162 cases), Beijing Cancer Hospital (84 cases), Cancer Hospital/Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (29 cases), and Harbin Medical University Cancer Hospital (47 cases) between January 2013 and December 2018. The APC diagnoses were histologically or cytologically proven and all of the patients provided written informed consent. This retrospective analysis was approved by the Ethics Committees of the Chinese PLA General Hospital. The study was conducted in accord with the Declaration of Helsinki recommendations for research involving human subjects.

Treatment

Nab-paclitaxel (120 mg/m2) was administered intravenously (IV) on Days 1 and 8. S-1 (120, 100, or 80 mg/day for body surface areas ≥1.5 m2, between 1.25 m2 and 1.5 m2, and <1.25 m2, respectively) was administered orally twice daily every 3 weeks on Days 1 to 14. Patients received gemcitabine (1000 mg/m2) IV on Days 1 and 8 plus nab-paclitaxel (120 mg/m2) IV on Days 1 and 8 every 3 weeks. Administration of 5-FU (400 mg/m2 and 2400 mg/m2) was by IV and continuous infusion, respectively. IV administration of leucovorin (400 mg/m2), irinotecan (140 mg/m2), and oxaliplatin (85 mg/m2) was IV on Day 1 every 2 weeks. In our study, routine blood tests were performed before treatment. Treatment was withdrawn or the dosages reduced depending on the degree of AEs experienced by patients. Of the patients who had previously undergone surgery, 15 received adjuvant therapy. Five patients received the gemcitabine plus S-1 (GS) regimen, 7 received gemcitabine alone, 2 received S-1 alone, and 1 received the AG regimen.

Assessments

All of the patients had measurable lesions. The efficacy of chemotherapy was assessed using the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors. All AEs were assessed using the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 3.0. Computed tomography scanning or magnetic resonance imaging was performed every 6 weeks until disease progression.

Statistical analysis

The primary endpoints of the study were the OS and PFS rates. The secondary endpoints were the disease control rate (DCR), defined as the percentage of patients who achieved a complete response (CR), partial response (PR), or who had disease that was stable disease for at least 8 weeks; the objective response rate (ORR), defined as the percentage of patients who achieved a CR or PR; and the toxicity of chemotherapy. A Kaplan-Meier analysis was performed to estimate survival benefit. We also collected data on patient demographics. All of the statistics were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics software (version 22.0).

Results

Patient characteristics

We recruited 322 patients for the analysis. Table 1 lists patient baseline characteristics, including age; sex; Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group score; tumor location; differentiation; number of metastases; levels of carcinoembryonic antigen, cancer antigen 19-9, and cancer antigen 125; and previous exposure to surgery or radiation therapy. The median age at diagnosis was 58.5 years (range 36–79). Of the patients, 62.4% (201) were men. The majority of patients (72%; 232) received AS as their first-line chemotherapy. Of the remaining patients, 79 received AG and 11 received FOLFIRINOX.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the 322 patients in the trial.

| Characteristic | AS (n=232) | AG (n=79) | FOLFIRINOX (n=11) | Total (n=322) | P value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | ||

| Sex | 0.275 | ||||||||

| Male | 140 | 60.3 | 52 | 65.8 | 9 | 81.8 | 201 | 62.4 | |

| Female | 92 | 39.7 | 27 | 34.2 | 2 | 18.2 | 121 | 37.6 | |

|

| |||||||||

| Median age (range) | 59 (36–79) | 59 (37–74) | 56 (43–67) | 58.5 (36–79) | |||||

|

| |||||||||

| ECOG PS | 0.062 | ||||||||

| 0 | 160 | 69.0 | 42 | 53.2 | 6 | 54.5 | 208 | 64.6 | |

| 1 | 71 | 30.6 | 35 | 44.3 | 5 | 45.5 | 111 | 34.5 | |

| 2 | 1 | 0.4 | 2 | 2.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 0.9 | |

|

| |||||||||

| Tumor location | 87 | 39.0 | 30 | 40.5 | 2 | 20.0 | 119 | 38.8 | |

| Head | 37 | 16.6 | 10 | 13.5 | 1 | 10.0 | 48 | 15.6 | 0.309 |

| Body | 48 | 21.5 | 19 | 25.7 | 3 | 30.0 | 70 | 22.8 | 0.574 |

| Tail | 47 | 21.1 | 15 | 20.3 | 4 | 40.0 | 66 | 21.5 | 0.852 |

| Body+tail | 4 | 1.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 1.3 | 0.49 |

|

| |||||||||

| Differentiation | 0.58 | ||||||||

| Poor | 82 | 58.6 | 28 | 54.9 | 2 | 28.6 | 112 | 56.6 | |

| Moderate | 56 | 40.0 | 22 | 43.1 | 5 | 71.4 | 83 | 41.9 | |

| High | 2 | 1.4 | 1 | 2.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 1.5 | |

|

| |||||||||

| Metastasis numbers | 0.393 | ||||||||

| 1 | 145 | 63.9 | 43 | 58.1 | 4 | 40.0 | 192 | 61.7 | |

| 2 | 43 | 18.9 | 18 | 24.3 | 4 | 40.0 | 65 | 20.9 | |

| ≥3 | 39 | 17.2 | 13 | 17.6 | 2 | 20.0 | 54 | 17.4 | |

|

| |||||||||

| Metastatic type | |||||||||

| Liver | 160 | 69.0 | 53 | 67.1 | 5 | 45.5 | 218 | 67.7 | 0.263 |

| Lung | 21 | 9.1 | 7 | 8.9 | 2 | 18.2 | 30 | 9.3 | 0.588 |

| Bone | 13 | 5.6 | 6 | 7.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 19 | 5.9 | 0.567 |

| Lymph node | 119 | 51.3 | 35 | 44.3 | 5 | 45.5 | 159 | 49.4 | 0.543 |

| Adrenal gland | 10 | 4.3 | 2 | 2.5 | 1 | 9.1 | 13 | 4.0 | 0.54 |

|

| |||||||||

| Operation | 0.376 | ||||||||

| Yes | 50 | 21.6 | 23 | 29.1 | 3 | 27.3 | 76 | 23.6 | |

| No | 182 | 78.4 | 56 | 70.9 | 8 | 72.7 | 246 | 76.4 | |

|

| |||||||||

| CEA | 0.143 | ||||||||

| Normal | 87 | 40.0 | 39 | 52.7 | 4 | 36.4 | 130 | 42.9 | |

| Abnormal | 131 | 60.0 | 35 | 47.3 | 7 | 63.6 | 173 | 57.1 | |

|

| |||||||||

| CA 19-9 | 0.508 | ||||||||

| Normal | 34 | 15.3 | 14 | 18.4 | 3 | 27.3 | 51 | 16.5 | |

| Abnormal | 188 | 84.7 | 62 | 81.6 | 8 | 72.7 | 258 | 83.5 | |

|

| |||||||||

| CA 125 | 0.312 | ||||||||

| Normal | 44 | 23.2 | 14 | 27.5 | 4 | 44.4 | 62 | 24.8 | |

| Abnormal | 146 | 76.8 | 37 | 72.5 | 5 | 55.6 | 188 | 75.2 | |

|

| |||||||||

| Median chemotherapy cycles (range) | 6 (2–23) | 4 (2–12) | 6 (3–16) | 5 (2–23) | |||||

|

| |||||||||

| Radiotherapy | 0.79 | ||||||||

| Yes | 44 | 19.0 | 15 | 19.0 | 3 | 27.3 | 62 | 19.3 | |

| No | 188 | 81.0 | 64 | 81.0 | 8 | 72.7 | 260 | 80.7 | |

Efficacy

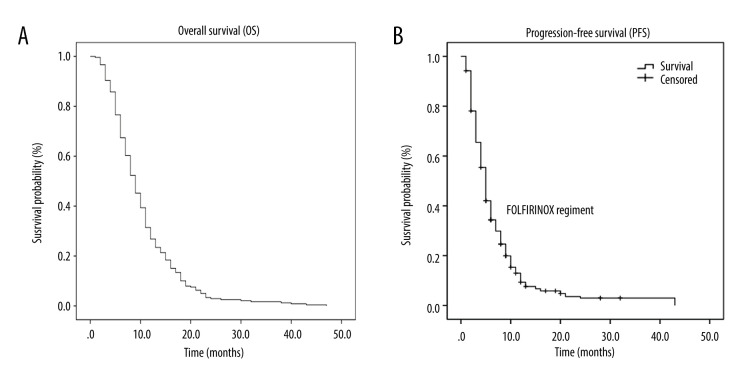

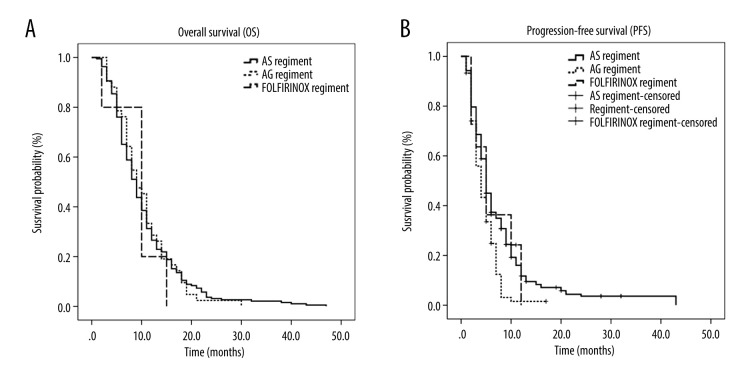

The median number of chemotherapy cycles was 5 (range 2-–23). As of December 1, 2019, the 1-year survival rate was 31%. The mOS rate was 9 months (95% confidence interval [CI]: 8.1 to 9.9) (Figure 1A). The mPFS rate was 5 months (95% CI: 4.6 to 5.4) (Figure 1B). The mOS rates for the AS, AG, and FOLFIRINOX regimens were 9 months (95% CI: 8.1–9.9), 9 months (95% CI: 7.0–11.0), and 10 months (95% CI: 5.3–14.7) respectively. The mPFS rates for the AS, AG, and FOLFIRINOX regimens were 5 months (95% CI: 4.4–5.6), 4 months (95% CI: 3.1–4.9), and 5 months (95% CI: 2.9–7.1) respectively. There was no statistically significant difference in OS rates among the 3 regimens (P=0.928) (Figure 2A), but there was among the PFS rates (P=0.001) (Figure 2B).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier curve of overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) in all patients. (A) OS in all patients in the trial. (B) PFS in all patients in the trial.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curve of overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) in patients treated with the regimens. (A) OS in patients treated with nab-paclitaxel and S-1 (AS), ab-paclitaxel and gemcitabine (AG), and 5-fluorouracil, leucovorin, irinotecan, and oxaliplatin (FOLFIRINOX). (B) PFS of patients treated with the AS, AG, and FOLFIRINOX.

The ORR to first-line chemotherapy was 38%. The ORRs for AS, AG, and FOLFIRINOX of 46.9%, 18.7%, and 0%, respectively, were statistically significantly different (P=0.000). The overall DCR was 81.8%. The DCRs for the AS, AG, and FOLFIRINOX regimens of 87.2%, 69.3%, and 63.6%, respectively, were statistically significantly different (P=0.001). Table 2 lists the rates of response to treatment in the patients.

Table 2.

Rates of treatment response in patients in the trial.

| Event | AS | AG | FOLFIRINOX | P value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any grade (%) | Grade 3/4(%) | Any grade (%) | Grade 3/4(%) | Any grade (%) | Grade 3/4 (%) | Any grade (%) | Grade 3/4 (%) | |

| Myelosuppression | 151 (68.3) | 54 (24.4) | 61 (63.2) | 15 (19.7) | 9 (81.8) | 3 (27.3) | 0.44 | 0.619 |

| Neurotoxicity | 97 (43.9) | 7 (3.2) | 15 (19.7) | 2 (2.6) | 2 (18.2) | 0 | 0.006 | |

| Diarrhea | 26 (12.3) | 5 (2.3) | 10 (13.2) | 0 | 4 (36.4) | 2 (18.2) | 0.002 | |

| Nausea and vomiting | 114 (51.6) | 4 (1.8) | 35 (46.1) | 1 (1.3) | 5 (45.5) | 1 (9.1) | 0.664 | |

| Liver dysfunction | 33 (14.9) | 1 (0.5) | 10 (13.2) | 1 (1.3) | 4 (36.4) | 0 | 0.502 | |

| Alopecia | 50 (22.6) | 2 (0.9) | 2 (2.6) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.005 | |

| Oral mucositis | 8 (3.6) | 3 (1.4) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.779 | |

| Rash | 11 (5) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (1.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.832 | |

| Total | 66 (29.9) | 19 (25) | 4 (36.4) | |||||

Safety and tolerability

Table 3 lists data on the toxicity of the chemotherapy regimens. The overall rate of grade 3/4 AEs was 28.9%, including myelosuppression (23.4%), nausea and vomiting (1.9%), diarrhea (2.3%), neurotoxicity (2.9%), liver dysfunction (0.6%), alopecia (0.6%), oral mucositis (1%), and rash (0.3%). The grade 3/4 AE rates for the AS, AG, and FOLFIRINOX regimens were 29.9%, 25%, and 36.4%, respectively. Intestinal obstruction occurred in 2 patients and pancreatitis occurred in 1 patient during treatment. In the majority of the patients, the AEs associated with chemotherapy were manageable and tolerable.

Table 3.

Rates of adverse events in patients in the trial.

| Variable | AS (n=211) | AG (n=75) | FOLFIRINOX (n=11) | Total (n=297) | P value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | ||

| Response | |||||||||

| Complete response | 2 | 0.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.7 | |

| Partial response | 97 | 46.0 | 14 | 18.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 111 | 37.3 | |

| Stable disease | 85 | 40.3 | 38 | 50.7 | 7 | 63.6 | 130 | 43.8 | |

| Progressive disease | 27 | 12.8 | 23 | 30.7 | 4 | 36.4 | 54 | 18.2 | |

|

| |||||||||

| Objective response rate | 98 | 46.9 | 14 | 18.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 113 | 38.0 | 0.000 |

|

| |||||||||

| Disease control rate | 184 | 87.2 | 52 | 69.3 | 7 | 63.6 | 243 | 81.8 | 0.001 |

Discussion

In this retrospective, multicenter analysis, we included 322 patients with APC who received AS, AG, or FOLFIRINOX as their first-line chemotherapy. The ORRs for AS, AG, and FOLFIRINOX were 46.9%, 18.7%, and 0%, respectively, and their DCRs were 87.2%, 69.3%, and 63.6%, respectively. Given the statistically significant differences in the ORRs and the DCRs, we concluded that the AS regimen was more effective than the other 2 regimens, with the rate of grade 3/4 AEs at 29.9%, compared with 25% for AG and 36.4% for FOLFIRINOX. Although treatment-associated toxicities are unavoidable with chemotherapy, the regimens had distinctly different AE rates. Therefore, when selecting chemotherapy for APC, clinicians should assess the disease status of a patient and balance the benefits and risks of various treatments [11].

Nab-paclitaxel is a novel, albumin-bound, solvent-free, water-soluble formulation of paclitaxel. With it, in contrast to previous castor oil-based formulations, pre-medication to avoid hypersensitivity reactions is unnecessary [12]. In the GEST study, the curves for OS and PFS in the S-1 group were nearly identical to those in the gemcitabine group, confirming the non-inferiority of S-1 to gemcitabine in terms of those 2 outcomes. Therefore, S-1, which offers the convenience of oral administration, can be used as first-line therapy for APC [9]. In a single-arm, phase 2 trial of 32 patients with APC reported by Wen Zhang et al. in 2018, use of AS followed by S-1 maintenance therapy resulted in ORRs and DCRs in the intent-to-treat (ITT) population of 53.1% and 87.5%, respectively. The mPFS rate was 6.2 months (range 4.4–8), and the mOS rate was 13.6 months (range 8.7–18.5). The incidence of grade 3/4 neutropenia was 27.6% [13], which was similar to our study. In another single-arm, single-center, phase 2 trial, AS and GS were administered to patients with APC. The mPFS and mOS rates were 5.6 months and 9.4 months, respectively, and the ORR was 50% in the ITT population [10]. The median times to progression (TTP) in the 2 groups were 7.1 months (95% CI: 4.5–9.7) and 3.6 months (95% CI: 1.8–5.4), respectively. The mOS rates were 10.2 months (95% CI: 9.1–11.3) and 6 months (95% CI: 4.2–7.8), respectively, which indicates that AS was associated with a prolonged median TTP (P=0.022) and improved mOS (P<0.001) [14].

Gemcitabine-based combination regimens, with either S-1 or nab-paclitaxel, have been associated with more frequent chemotherapy-related AEs [15,16]. Previous clinical trials support the conclusion that FOLFIRINOX is more toxic than gemcitabine and nab-paclitaxel [17]. In Asia, most patients with APC cannot tolerate the AEs associated with FOLFIRINOX; therefore, its application is limited. Both FOLFIRINOX and gemcitabine/nab-paclitaxel can be offered to patients who have good performance status.

There were also some limitations to the present study. First, only 11 patients were treated with FOLFIRINOX, which may explain why the regimen was not very effective. Second, we did not collect enough data on genetic testing because it is not covered by medical insurance in China and is so expensive that most patients cannot afford it. Further study is needed of the relationship between the expression of certain genes and the prognosis for APC.

Conclusions

In conclusion, AS and AG are safe and effective alternative regimens for APC. Moreover, in the present study, AS was more effective than AG and the favorable response to it showed that it has promise in patients with APC. These results should be confirmed by additional prospective, randomized trials. Individualized precision therapy should be the treatment of choice for patients diagnosed with unresectable PC.

Footnotes

Source of support: This study was supported by Suzhou Cooperative Medical and Health Foundation, No. GDS2019091601095 (Guang-hai Dai)

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(1):7–34. doi: 10.3322/caac.21551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rahib L, Smith BD, Aizenberg R, et al. projecting cancer incidence and deaths to 2030: The unexpected burden of thyroid, liver, and pancreas cancers in the United States. Cancer Res. 2014;74(11):2913–21. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-0155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adamska A, Domenichini A, Falasca M. Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: Current and evolving therapies. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(7):1338. doi: 10.3390/ijms18071338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conroy T, Desseigne F, Ychou M, et al. FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(19):1817–25. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mizrahi JD, Rogers JE, Hess KR, et al. Modified FOLFIRINOX in pancreatic cancer patients age 75 or older. Pancreatology. 2020;20(3):501–4. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2020.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Von Hoff DD, Ervin T, Arena FP, et al. Increased survival in pancreatic cancer with nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(18):1691–703. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1304369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maeda A, Boku N, Fukutomi A, et al. Randomized phase III trial of adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine versus S-1 in patients with resected pancreatic cancer: Japan Adjuvant Study Group of Pancreatic Cancer (JASPAC-01) Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2008;38(3):227–29. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hym178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ueno H, Ioka T, Ikeda M, et al. Randomized phase III study of gemcitabine plus S-1, S-1 alone, or gemcitabine alone in patients with locally advanced and metastatic pancreatic cancer in Japan and Taiwan: GEST study. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(13):1640–48. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.3680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shi Y, Zhang S, Han Q, et al. Nab-paclitaxel plus S-1 in advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma (NPSPAC): A single arm, single center, phase II trial. Oncotarget. 2017;8(54):92401–10. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.21359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen J, Chen L, Yu J, et al. Meta-analysis of current chemotherapy regimens in advanced pancreatic cancer to prolong survival and reduce treatment-associated toxicities. Mol Med Rep. 2019;19(1):477–89. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2018.9638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neesse A, Michl P, Tuveson DA, Ellenrieder V. Nab-Paclitaxel: Novel clinical and experimental evidence in pancreatic cancer. Z Gastroenterol. 2014;52(4):360–66. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1366002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang W, Du C, Sun Y, et al. Nab-paclitaxel plus S-1 as first-line followed by S-1 maintenance for advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma: A single-arm phase II trial. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2018;82(4):655–60. doi: 10.1007/s00280-018-3650-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu Y, Guo X, Fan Y, et al. Efficacy and safety comparison of nabpaclitaxel plus S-1 and gemcitabine plus S-1 as first-line chemotherapy for metastatic pancreatic cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2018;48(6):535–41. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyy063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Von Hoff DD, Ervin T, Arena FP, et al. Increased survival in pancreatic cancer with nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(18):1691–703. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1304369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sudo K, Takeshi I, Hirata N, et al. Randomized controlled study of gemcitabine plus S-1 combination chemotherapy versus gemcitabine for unresectable pancreatic cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2014;73(2):389–96. doi: 10.1007/s00280-013-2368-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Muranaka T, Kuwatani M, Komatsu Y, et al. Comparison of efficacy and toxicity of FOLFIRINOX and gemcitabine with nab-paclitaxel in unresectable pancreatic cancer. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2017;8(3):566–71. doi: 10.21037/jgo.2017.02.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]