Abstract

Molecular mechanism of diseases like Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Parkinson’s diseases (PD) is associated with misfolding of specific proteins, such as amyloid beta (Aβ) proteins in the case of AD, followed by their self-assembly into toxic oligomers along with the formation of amyloid fibrils assembled as plaques in the brain. Interaction of Aβ with membrane can lead to membrane damage; this process is considered as the major factor associated with the AD development. Additionally, membrane can facilitate the aggregation process of Aβ proteins. This important property of membranes is discussed in this review. A specific emphasis is given to the recently discovered property of cellular membranes to catalyze the initial step of Aβ aggregation process by which self-assembly of Aβ can be observed at physiologically low concentrations of Aβ proteins. At such low concentrations, no spontaneous aggregation occurs in the bulk solution. This fact was a major weakness of the protein aggregation model for AD. The catalytic property of membrane surfaces towards Aβ aggregation depends on the membrane composition. This finding suggests a number of novel ideas on the development of treatments and preventions for AD, which is briefly discussed in the review.

Keywords: Amyloid aggregation, Neurodegenerative diseases, Cellular membrane, Lipid bilayer, AFM imaging

Introduction

The self-assembly of misfolded proteins resulting in the formation of protein aggregates leads to a variety of human disorders, including fatal neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Huntington’s disease, and Parkinson’s disease (PD) [1–3]. The formation of amyloid plaques in the AD patient’s brain has been attributed as one of the major pathogenic signatures of the disease [4]. Growing evidence directly points out the involvement of protein oligomers in the development of protein misfolding diseases, including AD and PD. Numerous studies have tested the effect of various factors, including the protein monomer concentration, presence of metal ions, pH of the medium, and interaction with small molecules-that influence the aggregation kinetics [5,6]. However, very limited knowledge is available regarding the molecular mechanisms behind the disease development. The amyloid cascade hypothesis (ACH) which was proposed more than a quarter-century ago [7] remains as one of the major models for AD pathology and other neurodegenerative diseases [7–11]. The spontaneous assembly of amyloidogenic proteins to form the protein oligomers has been assigned as the main event for disease development in ACH model. Based on this model, efforts have been made to decrease the concentration of amyloid proteins for decelerating the aggregation process. However, drug development focused towards decreasing the Aβ concentration, as well as disaggregating the plaques, has failed [12,13], which challenges the validity of ACH. Indeed, all amyloidogenic proteins are functionally important proteins in the monomeric state. Therefore, positive functional roles of amyloid protein monomers could be hindered by decreasing the concentration. Another major problem that remains with ACH [9] is the high concentration of Aβ. Most of the in vitro studies have been carried out in high micromolar concentration range. However, the physiological concentration of Aβ is in low nanomolar to picomolar range [14–17]. It raises the question of how Aβ proteins assemble into oligomers at such low concentrations. These limitations of ACH demonstrate the necessity of an alternative model for AD development. Intracellular conditions, such as the protein crowding effect, facilitate the self-assembly of amyloidogenic proteins and membrane surface is another important cellular component contributing to the aggregation.

In this review, we will mainly focus on the studies (i) showing the catalytic effect of surface and cellular membrane towards the aggregation of amyloid proteins and (ii) how the protein-lipid membrane interaction leads to the cytotoxicity.

Surfaces as Catalysts for Amyloid Aggregation at Physiologically Relevant Low Concentrations

The major limitation of the ACH in explaining the neurodegenerative disease development is the in vivo concentration of amyloidogenic peptides, which is several orders of magnitude below the critical concentration required to form the aggregates observed in post-mortem brains. This limitation can be dramatically reduced by considering a novel aggregation pathway where the amyloid proteins interact with the surfaces. It is observed that α-Syn dimers can be formed at nanomolar concentrations when the target monomer is tethered to a surface [18]. This result gave the first indication for the hypothesis that binding of the amyloid proteins to the surface can dramatically enhance the aggregation processes. To test this hypothesis, atomic force microscopy (AFM) was applied to directly visualize the surface-mediated aggregation at the nanomolar range for full-sized Aβ42, the Aβ (14–23) peptide, and α-Synuclein (α-Syn) protein [19]. The time-lapse experiments of the on-surface aggregation demonstrate directly that the aggregation of these proteins occurs at concentrations as low as 10 nM with no visible aggregation in the bulk solution. Gradual increase in both number and size of the aggregates were observed, indicating the surface-catalyzed aggregation process. Time-lapse experiments, in which a selected area was imaged continuously, revealed an important property for the on-surface assembly of aggregates – they can dissociate from the surface, creating a pool of aggregates in bulk solution. This property was confirmed by direct measurement of the concentration of aggregates in bulk solution. Thus, on-surface aggregation is the mechanism by which amyloid oligomers in solution can be produced, regardless of their low concentration. This conclusion is in line with a recent publication [20] in which aggregation of Aβ40 and Aβ42 peptides at nanomolar concentrations was detected with the use of a single-molecule fluorescence approach. A theoretical model that offers a molecular explanation has been proposed in paper [21]. According to this model, monomers transiently immobilized to surfaces increase the local monomer protein concentration and thus work as nuclei to dramatically accelerate the entire aggregation process. This theory was verified by experimental studies using mica surfaces to examine the aggregation kinetics of amyloidogenic α-Syn and non-amyloidogenic cytosine deaminase APOBEC3G.

Interaction of Aβ with lipid membrane

Cellular membrane is a complex system, so simplified models like vesicles, micelles, supported lipid bilayer (SLB) nanodiscs have been used to mimic the membrane environment [22–25]. AFM imaging was applied to visualization of interaction of smooth, homogeneous SLB is prepared to directly visualize the aggregation of Aβ42 protein with phospholipid bilayers containing 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC), 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-L-serine (POPS) [22]. These methodological advances allowed the authors to directly visualize aggregation of Aβ42 at concentrations as low as10 nM, which is very close physiological ones. In all cases, aggregates have been observed to be mainly oligomers, no fibrils have been detected. The presence of 150 mM NaCl further increases the on-membrane aggregation [26]. Lipid vesicles have also been used to probe the aggregation kinetics of Aβ, and the acceleration of the aggregation has been observed [27]. David, et al. showed that the enhanced aggregation rate is mainly initiated by vesicle-fibril interaction. Zwitterionic 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DOPC) vesicles do not alter primary nucleation step; rather, monomer dependent secondary nucleation on the fibril surface helps to enhance the overall rate of aggregation [27]. The role of membrane curvature in the aggregation of Aβ has also been monitored. A smaller liposome having larger curvature has been found to accelerate the aggregation of Aβ40 by shortening the lag phase [28]. The effect of the thickness of lipid bilayer towards Aβ aggregation has been tested by assembling vesicles with different acyl chain lengths. 1,2-dilauroyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DLPC) vesicles with shorter lipid chains inhibited the amyloid fibril formation by stabilizing disordered aggregates, whereas conventional bilayers with DOPC and POPC facilitated fibril formation [29].

Numerous reports indicate that the composition of the membrane plays a significant role in the development of the disease state by facilitating the formation of Aβ oligomers [30]. Lipid rafts are a microdomain in the membrane which are rich in cholesterol and sphingolipids and serve a critical role in neuronal functions. Cholesterol was known to modulate the Aβ interaction with lipid bilayers [31]. In addition, cholesterol depletion in hippocampal neurons reduced the production of insoluble Aβ [32]. Recent studies show that cholesterol in 1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DMPC) vesicles plays a catalytic role in enhancing the aggregation of Aβ by increasing the primary nucleation rate 20 fold [33]. However, the role of cholesterol in Aβ self-assembly has been controversial, and conflicting results are reported. Increase in the level of cholesterol in neuroblastoma cells has been found to inhibit the binding of Aβ with gangliosides [34]. Such results demonstrate that it is not a single component of lipid bilayer that modulates Aβ aggregation; rather, multiple components in the bilayer are involved. This led to investigation of the role of different lipids for the development of AD. It has been found that the level of gangliosides [35], which are glycosphingolipids, predominantly found in the central nervous system has a direct relation to AD pathology. A recent study shows that Aβ binds with GM1 cluster, and it is the Aβ monomer which is mainly involved in the binding, not the oligomers [36]. GM1 enriched membrane induced the fibril formation and oligomer deposition [37]. Ganglioside bound Aβ has been found to possess strong seeding ability towards amyloid formation [38]. This evidence points out that different membrane components have a crucial and decisive role towards the formation of Aβ aggregates.

α-Syn Aggregation on the Membrane Bilayers

Catalytic effect of lipid membrane in α-Syn aggregation has also been observed [39]. Time-lapse AFM imaging has shown that 10 nM α-Syn can form oligomers when exposed to POPC, POPS and POPC-POPS (1:1 mol) mixture SLB. More aggregates accumulated over time, as well as the size of aggregates. Very few aggregates were found in the absence of a phospholipid bilayer in a 10 nM solution of α-Syn incubated under the same conditions. The aggregation propensity depends on the bilayer composition, demonstrating that a negatively charged POPS surface catalyzes the aggregation process much faster than the overall neutral POPC surface. The dynamics of the aggregation process in which assembled aggregates dissociate from the surface was observed for these bilayers and α-Syn. Thus, cellular membranes, regardless of the low concentrations of the protein, catalyze the conversion of monomeric α-Syn to oligomeric aggregates; the membrane composition contributes to the efficiency of aggregate assembly, and assembled oligomers can dissociate from the membrane to the solution.

Computer simulations were applied in paper [39] to reveal the underlying molecular mechanism of α-Syn aggregation on the bilayer surface. Computational modeling revealed that dimers of α-Syn assembled rapidly through the membrane-bound monomer on POPS bilayer due to an aggregation-prone orientation of α-Syn. Interaction of α-Syn with POPC leads to a binding mode that does not induce a fast assembly of the dimer. Membrane induced structural alterations of α-Syn have also been reported. The N-terminus of the protein has been identified as the essential part for both lipid binding and formation of α-helical structure [40]. α-Syn forms curved α-helices ranging the residues Val3-Val37 and Lys45-Thr92 when bound to micelles [41].

The overall conclusion of these studies was that phospholipid bilayers dramatically facilitate aggregation of α-Syn on the surface, with aggregates forming at concentrations as low as the nanomolar range. The membrane composition defines the aggregation catalytic properties of the membrane. This is a novel pathway for the spontaneous assembly of amyloid oligomers at physiologically relevant concentrations.

Changes in both protein and membrane structure as a cause for toxicity

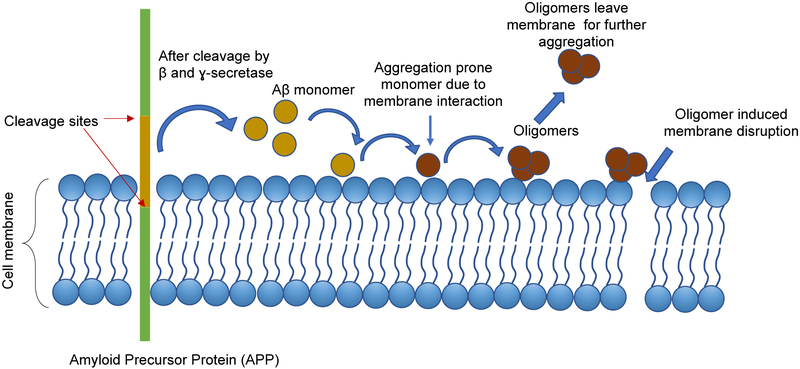

The interaction of Aβ with the lipid membrane is considered to have a two-way effect toward the disease development: (i) it changes the protein conformation in such a way that the changed Aβ structure triggers the oligomer formation, and (ii) the formed oligomers can alter the membrane structure to initiate the toxicity (Figure 1). Molecular dynamics simulations show that the transient interaction of Aβ with POPC has an extensive effect towards generating β-structure in the protein, which has never been seen in solution [26]. The β-content increases up to 17% as the peptide transiently interacts with the POPC bilayer. The interaction is mainly focused towards the N-terminal and residues of the central 20–30 segment. This Aβ conformation with higher β-content rapidly forms a dimer with a free monomer. Similar interaction between Aβ and lipid bilayer has been observed to induce trimer and tetramer formation [26].

Figure 1:

Schematic showing the plausible mechanism behind the membrane induced Aβ oligomer formation followed cytotoxic effects of oligomers.

Aβ peptides are produced by proteolytic cleavage of membrane protein APP. Aβ can then self-assemble to form oligomers and fibrils, or the monomer can interact with different membrane components, including phospholipids, cholesterol or sphingolipids. These interactions can induce structural changes in Aβ and facilitate the aggregation process. The oligomers formed on the membrane can leave the surface and participate in further aggregation as seeds. Membrane-oligomer interaction could result in membrane disruption which can lead to cytotoxicity.

This enhanced rate of oligomer formation is proposed to be one of the potential causes for membrane disruption, which is thought to be the major pathway for cytotoxicity. Aβ induced membrane disruption of PC-PS-ganglioside containing large unilamellar vesicles has been identified as a two-step process, where initial ion selective pores are formed in the membrane, and later nonspecific fragmentation of the lipid membrane takes place during fibril formation [42]. The binding of Aβ oligomers to the large unilamellar vesicles (LUVs) induce the calcein release, directly showing the disruption of membrane structure [43]. A detergent-like effect of Aβ has also been reported on lipid bilayer where the oligomers damage the bilayer integrity, and lipid extraction has been observed [44].

Membrane permeabilization by α-Syn aggregates is also thought to be one of the major pathways for generation of cytotoxicity. Protofibrilar aggregates of α-Syn are observed to bind vesicles and permeabilize them [45]. The formation of highly conductive ion channels has been detected by WT α-Syn and mutants E46K and A53T [46].

Concluding Remarks

The amyloid-membrane interaction has long been studied by multiple approaches and the major emphasis to explain the disease development. The membrane damage by the oligomers is considered as one of the major neurotoxic mechanism associated with the disease development. The recent findings on the membrane catalysis of amyloid aggregation highlight another important property of membranes in the development of the diseases [26]. According to the model shown in (Figure 1), self-assembly of the disease-prone amyloid aggregates is initiated and driven by the interaction of amyloid proteins with the cellular membrane. This process takes place at a physiologically low concentration of amyloids, providing additional support for the amyloid hypothesis. Furthermore, assembled aggregates can also dissociate from the membrane to initiate neurodegenerative processes such as the assembly neurofibrillary tau-mediated tangles. The proposed model is a paradigm shift for the development of efficient treatments and diagnostics for AD, PD, and other protein aggregation diseases. According to this model, treatment efforts will be focused on decreasing the affinity of amyloid proteins to membranes by the development of small molecules that interfere with membrane-amyloid interactions and the change in the membrane composition via regulation of lipid metabolism. Control of the membrane composition is expected to be the major focus for preventative means that can be proven by corresponding experimental studies.

Acknowledgements

The work at the University of Nebraska Medical Center (UNMC) was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health to Y.L.L. (R01 GM096039, R01GM118006 and R21 NS101504) Authors sincerely thank Thomas D Stormberg for diligent proofreading of the manuscript.

Abbreviations:

- AD

Alzheimer’s Disease

- PD

Parkinson’s Diseases

- ACH

Amyloid Cascade Hypothesis

- AFM

Atomic Force Microscopy

- POPC

1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine

- POPS

1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-L-serine

- DOPC

1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine

- DLPC

dilauroyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine

- DMPC

1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine

- APP

Amyloid Precursor Protein

- LUVs

Large Unilamellar Vesicles

References

- 1.Dobson CM (2004) Principles of protein folding, misfolding and aggregation. Semin Cell Dev Biol 15(1): 3–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chiti F, Dobson CM (2006) Protein misfolding, functional amyloid, and human disease. Annual review of biochemistry 75: 333–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Selkoe DJ (1991) The molecular pathology of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron 6(4): 487–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Small DH, Mok SS, Bornstein JC (2001) Alzheimer’s disease and Abeta toxicity: from top to bottom. Nat Rev Neurosci 2(8): 595–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tiiman A, Krishtal J, Palumaa P, Tõugu V (2015) In vitro fibrillization of Alzheimer’s amyloid-β peptide (1–42). AIP Advances 5(9): 092401. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Habchi J, Chia S, Limbocker R, Mannini B, Ahn M, et al. (2017) Systematic development of small molecules to inhibit specific microscopic steps of Aβ42 aggregation in Alzheimer’s disease. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 114(2): E200–E208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hardy JA, Higgins GA (1992) Alzheimer’s disease: the amyloid cascade hypothesis. Science 256(5054): 184–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mohamed T, Shakeri A, Rao PPN (2016) Amyloid cascade in Alzheimer’s disease: Recent advances in medicinal chemistry. Eur J Med Chem 113: 258–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Armstrong RA (2014) A critical analysis of the ‘amyloid cascade hypothesis’. Folia Neuropathologica 52(3): 211–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hardy J (2006) Has the amyloid cascade hypothesis for Alzheimer’s disease been proved? Curr Alzheimer Res 3(1): 71–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hardy J (2006) Alzheimer’s disease: the amyloid cascade hypothesis: an update and reappraisal. J Alzheimers Dis 9(3): 151–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abbott A, Dolgin E (2016) Leading Alzheimer’s theory survives drug failure. Nature 540: 15–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hardy J, De Strooper B (2017) Alzheimer’s disease: where next for anti-amyloid therapies? Brain 140(4): 853–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McGeer PL, McGeer EG (2013) The amyloid cascade-inflammatory hypothesis of Alzheimer disease: implications for therapy. Acta Neuropathol 126(4): 479–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.An SSA, Lee BS, Yu JS, Lim K, Kim GJ, et al. (2017) Dynamic changes of oligomeric amyloid β levels in plasma induced by spiked synthetic Aβ42. Alzheimer’s Res Ther 9(1): 86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bjerke M, Portelius E, Minthon L, Wallin A, Anckarsäter H, et al. (2010) Confounding factors influencing amyloid Beta concentration in cerebrospinal fluid. Int J Alzheimers Dis 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Copani A (2017) The underexplored question of β-amyloid monomers. Eur J Pharmacol 817: 71–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lv Z, Krasnoslobodtsev AV, Zhang Y, Ysselstein D, Rochet JC, et al. (2015) Direct Detection of α-Synuclein Dimerization Dynamics: Single-Molecule Fluorescence Analysis. Biophys J 108(8): 2038–2047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Banerjee S, Hashemi M, Lv Z, Maity S, Rochet JC, et al. (2017) A novel pathway for amyloids self-assembly in aggregates at nanomolar concentration mediated by the interaction with surfaces. Scientific Reports 7: 45592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chang CC, Edwald E, Veatch S, Steel DG, & Gafni A (2018) Interactions of amyloid- β peptides on lipid bilayer studied by single molecule imaging and tracking. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Biomembranes 1860(9): 1616–1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pan YG, Banerjee S, Zagorski K, Shlyakhtenko LS, Kolomeisky AB, et al. (2018) A molecular model of the surface-assisted protein aggregation process. Bio R xiv: 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lv Z, Banerjee S, Zagorski K, Lyubchenko YL (2018) Supported Lipid Bilayers for Atomic Force Microscopy Studies. Methods Mol Biol 1814: 129–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Durr UH, Gildenberg M, Ramamoorthy A (2012) The magic of bicelles lights up membrane protein structure. Chemical reviews 112(11): 6054–6074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ahmad Z, Shah A, Siddiq M, Kraatz HB (2014) Polymeric micelles as drug delivery vehicles. RSC Advances 4(33): 17028–17038. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Akbarzadeh A, Rezaei Sadabady R, Davaran S, Joo SW, Zarghami N, et al. (2013) Liposome: classification, preparation, and applications. Nanoscale research letters 8(1): 102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Banerjee S, Hashemi M, Zagorski K, & Lyubchenko YL (2019) Lipid membranes trigger misfolding and self-assembly of amyloid β 42 protein into aggregates. Bio R xiv: 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lindberg DJ, Wesen E, Bjorkeroth J, Rocha S, & Esbjorner EK (2017) Lipid membranes catalyse the fibril formation of the amyloid-beta (1–42) peptide through lipid-fibril interactions that reinforce secondary pathways. Biochimica et biophysica acta. Biomembranes 1859(10): 1921–1929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Terakawa MS, Yagi H, Adachi M, Lee YH, & Goto Y (2015) Small liposomes accelerate the fibrillation of amyloid beta (1–40). J Biol Chem 290(2): 815–826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Korshavn KJ, Satriano C, Lin Y, Zhang R, Dulchavsky M, et al. (2017) Reduced Lipid Bilayer Thickness Regulates the Aggregation and Cytotoxicity of Amyloid-beta. The Journal of biological chemistry 292(11): 4638–4650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rushworth JV, Hooper NM (2010) Lipid Rafts: Linking Alzheimer’s Amyloid- β Production, Aggregation, and Toxicity at Neuronal Membranes. International journal of Alzheimer’s disease 2011: 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Qiu L, Lewis A, Como J, Vaughn MW, Huang J, et al. (2009) Cholesterol Modulates the Interaction of beta- Amyloid Peptide with Lipid Bilayers. Biophys J 96(10): 4299–4307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schneider A, Schulz-Schaeffer W, Hartmann T, Schulz JB, Simons M (2006) Cholesterol depletion reduces aggregation of amyloid-beta peptide in hippocampal neurons. Neurobiol Dis 23(3): 573–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Habchi J, Chia S, Galvagnion C, Michaels TCT, Bellaiche MMJ, et al. (2018) Cholesterol catalyses Abeta42 aggregation through a heterogeneous nucleation pathway in the presence of lipid membranes. Nature chemistry 10(6): 673–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cecchi C, Nichino D, Zampagni M, Bernacchioni C, Evangelisti E, et al. (2009) A protective role for lipid raft cholesterol against amyloid-induced membrane damage in human neuroblastoma cells. Biochimica et biophysica acta 1788(10): 2204–2216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Molander Melin M, Blennow K, Bogdanovic N, Dellheden B, Mansson JE, et al. (2005) Structural membrane alterations in Alzheimer brains found to be associated with regional disease development; increased density of gangliosides GM1 and GM2 and loss of cholesterol in detergent-resistant membrane domains. J Neurochem 92(1): 171–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thomaier M, Gremer L, Dammers C, Fabig J, Neudecker P, et al. (2016) High-Affinity Binding of Monomeric but Not Oligomeric Amyloid-β to Ganglioside GM1 Containing Nanodiscs. Biochemistry 55(48): 6662–6672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Matsubara T, Nishihara M, Yasumori H, Nakai M, Yanagisawa K, et al. (2017) Size and Shape of Amyloid Fibrils Induced by Ganglioside Nanoclusters: Role of Sialyl Oligosaccharide in Fibril Formation. Langmuir 33(48): 13874–13881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kakio A, Nishimoto S, Yanagisawa K, Kozutsumi Y, Matsuzaki K (2002) Interactions of amyloid beta-protein with various gangliosides in raft-like membranes: importance of GM1 ganglioside-bound form as an endogenous seed for Alzheimer amyloid. Biochemistry 41(23): 7385–7390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lv Z, Hashemi M, Banerjee S, Zagorski K, Rochet JC, et al. (2018) Phospholipid membranes promote the early stage assembly of α-synuclein aggregates. Bio R xiv: 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vamvaca K, Volles MJ, Lansbury PT (2009) The first N-terminal amino acids of alpha-synuclein are essential for alpha-helical structure formation in vitro and membrane binding in yeast. J Mol Biol 389(2): 413–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ulmer TS, Bax A, Cole NB, & Nussbaum RL (2005) Structure and dynamics of micelle-bound human alpha-synuclein. The Journal of biological chemistry 280(10): 9595–9603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sciacca MF, Kotler SA, Brender JR, Chen J, Lee DK, et al. (2012) Two-Step Mechanism of Membrane Disruption by Aβ through Membrane Fragmentation and Pore Formation. Biophysical journal 103(4): 702–710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Williams TL, Day IJ, Serpell LC (2010) The effect of Alzheimer’s Abeta aggregation state on the permeation of biomimetic lipid vesicles. Langmuir 26(22): 17260–17268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bode DC, Freeley M, Nield J, Palma M, Viles JH (2019) Amyloid-beta oligomers have a profound detergent-like effect on lipid membrane bilayers, imaged by atomic force and electron microscopy. Journal of biological chemistry 294(19): 7566–7572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Volles MJ, Lee SJ, Rochet JC, Shtilerman MD, Ding TT, et al. (2001) Vesicle permeabilization by protofibrillar alpha-synuclein: implications for the pathogenesis and treatment of Parkinson’s disease. Biochemistry 40(26): 7812–7819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zakharov SD, Hulleman JD, Dutseva EA, Antonenko YN, Rochet JC, et al. (2007) Helical alpha-synuclein forms highly conductive ion channels. Biochemistry 46(50): 14369–14379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]