Abstract

Background:

The Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS) is a widely used measure of negative emotional states. While the DASS is increasingly used in mental health research in India, to date no study has examined the factor structure among Indian adults.

Methods:

A large community sample of English-speaking Indian adults completed the DASS 21-item version, and confirmatory factor analyses were conducted.

Results:

The results indicated a good fit for a three factor (depression, anxiety, and stress) and a one-factor model (general psychological distress). There was no substantial difference between the fit of the models, and the DASS subscales were very strongly correlated with one another (r ≥ .80).

Conclusion:

The findings from this sample suggest that the DASS-21 items appear to assess general psychological distress, with little evidence that the items assess three distinct subscales.

Keywords: Confirmatory factor analysis, Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale, factor structure, India

INTRODUCTION

The Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS[1]) is a widely used measure of the negative emotional states of depression, anxiety, and stress. Its impact is clear, having been cited more than 5300 times in the scientific literature.[1] The DASS has demonstrated good psychometric properties in converging with other measures of these emotional states[2] and has been psychometrically validated in a diverse range of countries around the world.[3,4,5]

As the need for increased provision of mental health services is identified in the vast population of India,[6] so too is the need for psychometrically valid instruments to assess symptoms of mental ill health. A range of measures have already been developed in Western countries, but require close examination to assess whether their items assess underlying factors in the same manner as originally intended, or whether differences in responding based on language or culture may alter this. While the DASS may be an appropriate measure for the Indian context, to the authors' knowledge, only two studies to date have examined the factor structure of the DASS among Indians. One study by Singh et al.[7] focused on examining the psychometric properties of a Hindi-translated version of the DASS in a sample of bilingual adults. Their results showed that the subscales each had acceptable internal reliability, but principal components analysis showed that between four to six items on each subscale loaded poorly onto their respective factors (factor loading <0.40). In a second study, Singh et al.[8] administered English and Hindi versions of the shortened 21-item version of the DASS (DASS-21) to a large sample of school-attending adolescents described as being “well-versed” in both languages. Their results indicated that fit indices did not reach cutoffs, indicating a good fit for the English version; however, the Hindi version was acceptable. On the English version, factor loadings indicated that a number of items, particularly on the stress subscale, did not load very strongly onto the latent variable of stress.

To date, no study has assessed whether the factor structure of an English language version of the DASS is valid in a sample of Indian adults, and whether its items predict the underlying factors of depression, anxiety, and stress that it is intended to measure. A further consideration is whether the items used in the DASS discriminate between these three emotional states. Contrary to earlier findings of the psychometric properties of the DASS subscales,[1,9] studies in various racially[10] and culturally diverse groups[4] have shown that the subscales correlate extremely highly with one another. If these subscales share most of their variance with one another, they may not be useful for the purpose of discriminating emotional states, or examining which variables are uniquely related to depression, anxiety, and stress.

Given the increasing use of the DASS in the Indian context,[11,12,13,14,15] further examination of the factor structure is needed now to determine its validity and identify any changes that may need to be made. This study aimed to compare the psychometric properties of a three- and one-factor model of the DASS items using an English language version of the DASS in a population of Indian adults.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Setting and participants

The survey was part of a larger study to explore patterns of technology use. The sample was collected from colleges and workplaces in urban (Bengaluru) and rural (Kolar) localities of Karnataka, India. To ensure representation of different economic classes, specific colleges and workplaces were targeted for sampling. The inclusion criteria were between 18 and 25 years of age and the ability to read and write English language, which were assessed through direct questioning. There were no exclusion criteria.

Materials

The participants were administered the 21-item short-form version of the DASS. Each DASS subscale comprises seven self-report items that are rated on a four-point scale from 0 (did not apply to me at all) to 3 (applied to me very much, or most of the time). The depression subscale assesses core depressive symptomatology of dysphoria, hopelessness, devaluation of life, self-deprecation, lack of interest/involvement, anhedonia, and inertia. The anxiety subscale assesses core anxiety symptomatology of autonomic arousal, skeletal muscle effects, situational anxiety, and the subjective experience of anxious affect. The stress subscale assesses chronic, nonspecific arousal, namely, difficulty relaxing, nervous arousal, being easily upset or agitated, irritability and overreactance, and impatience.

Procedure

Ethics approval was obtained from the National Institute for Mental Health and Neuroscience Research Ethics Committee before recruitment commencing. The administration was carried out in a group setting. After signing informed consent form, participants were administered a sociodemographic data sheet and the DASS as part of a packet of measures. Researchers with postgraduate qualifications explained the rationale of the study and administered the survey in a group setting. Participation was anonymous, voluntary, and no incentives were provided. There were no refusals to participate.

Data analytic approach

To assess and compare the fit of a priori one- and three-factor models of the DASS-21 items to the data, confirmatory factor analyses were conducted using the Rosseel and Lavaan package[16] in R. A weighted least squares means with variance adjusted robust estimator (WLSMV) was used to estimate the model, which provides less biased and more accurate estimations of factor loadings in ordinal data, which is not assumed to be normally distributed, compared to maximum likelihood estimation.[17] Two models were tested: the prescribed three-factor model with items loading onto depression, anxiety, and stress factors, and a one-factor model with all items loading onto one underlying psychological distress factor. We assessed model fit with the following indices: WLSMV test statistic and corresponding P value, the comparative fit index (CFI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). The guidelines used for interpreting whether models were a good fit were provided by Hu and Bentler,[18] who suggested that in a good fitting model, the RMSEA is ≤0.06, the SRMR is ≤ 0.09, and the CFI is ≥0.95. We used Chi-square test to assess for differences between the models in fit to the data. However, given this test is known to be overly sensitive to differences in large samples, a difference exceeding 0.01 on the CFI was also adopted as a criterion for assessing differences between models. This goodness-of-fit index is independent of model complexity and sample size in assessing relative fit.[19] Given the ordinal and nonnormally distributed nature of the data, Spearman's rank correlation confidents were used to assess bivariate correlations. Cronbach's alpha was used as a measure of the internal consistency of scale items.

RESULTS

A total of 784 participants were recruited. Responses sets that were missing data were removed (n = 11) as were those with univariate outliers (n = 5). The final sample comprised 768 participants. Table 1 shows the sample characteristics, indicating that the sample was majority single, young adults who were students.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics

| Variable | Statistic (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 20.9 (3.0) |

| Sex (female) | 62.2 |

| Salary, mean (SD) | 26,317 INR (38,889) |

| Education | |

| Postgraduate | 22.7 |

| Graduate | 63.4 |

| Year 12 | 10.5 |

| Below year 10 | 3.4 |

| Occupation | |

| Currently studying | 77.5 |

| Working in government | 16.9 |

| Private employment | 5.6 |

| Relationship status | |

| Single | 88.1 |

| Married | 7.6 |

| Living with partner | 4.3 |

SD – Standard deviation

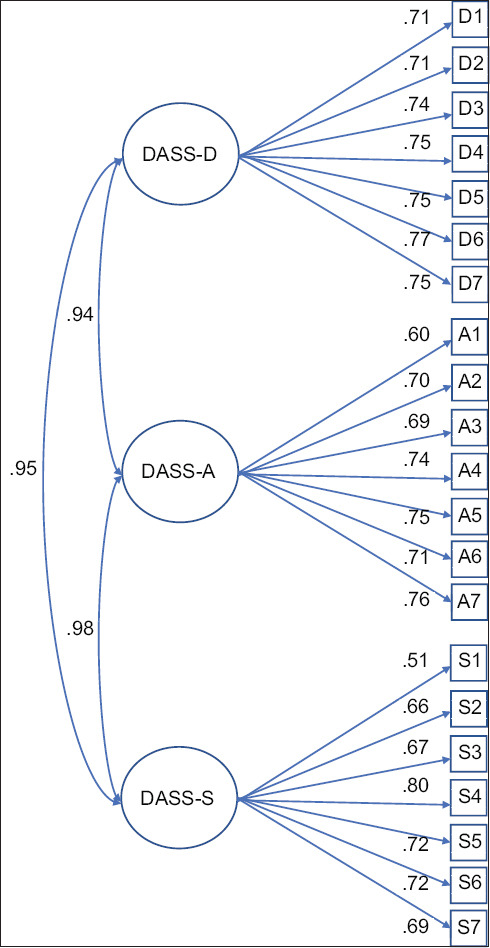

Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics, correlations, and internal reliabilities for the DASS scales. The subscales showed good internal reliability, were strongly correlated with one another, and had a strong positive skew, typical for measures of symptoms of mental ill health. A three-factor confirmatory factor analysis model was then conducted with latent variables for depression, anxiety, and stress items. The results indicated a good fit to the data WLSMV statistic = 422.0 (df = 186, P < 0.001), CFI = 0.985, RMSEA = 0.041 (90% confidence interval [CI]: 0.036–0.046), SRMR = 0.041. All items loaded significantly and strongly onto their latent variables [Figure 1]. The exception to this was the first item of the stress subscale, “I found it hard to wind down,” which had a weaker factor loading magnitude relative to other items. No cross-loadings were allowed between items. As indicated, the factors correlated very strongly with each other, sharing the large majority of their variance with one another (range of shared variance = 88.3%–96%).

Table 2.

Statistics for the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale variables

| DASS-D | DASS-A | DASS-S | Mean (SD) | Cronbach’s α | Skew/kurtosis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DASS-D | - | 3.4 (3.5) | 0.85 | 10.7/0.3 | ||

| DASS-A | 0.80*** | - | 3.5 (3.7) | 0.81 | 11.1/0.8 | |

| DASS-S | 0.81*** | 0.82*** | - | 3.9 (3.7) | 0.81 | 9.2/0.5 |

***P<0.001. D – Depression; A – Anxiety; S – Stress; DASS – Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale; SD – Standard deviation

Figure 1.

Three-factor model of DASS subscales. All standardized loadings and covariances p < .001

A second model loading all items onto a single latent variable was then conducted. The results again indicated a good fit to the data, WLSMV statistic = 445.8 (df = 189, P < 0.001), CFI = 0.982, RMSEA = 0.042 (90% CI: 0.037–0.047), SRMR = 0.04, and all items loaded strongly onto the latent factors [Table 3]. Again, no cross-loadings were allowed between items. Chi-square difference test indicated that the three-factor model was a better fit to the data, χ2Δ (df = 3) =23.8, P < 0.001; however, no difference was observed on the CFI. On this basis, there was little evidence that the three-factor model had a superior fit to the data.

Table 3.

Statistics for the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale items in the one-factor model in standard order of administration

| Item | Subscale | Mean (SD) | Item-total correlation | Standardized factor loadings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Stress | 0.44 (0.68) | 0.45 | 0.51 |

| 2 | Anxiety | 0.56 (0.81) | 0.56 | 0.60 |

| 3 | Depression | 0.56 (0.80) | 0.65 | 0.70 |

| 4 | Anxiety | 0.41 (0.73) | 0.59 | 0.69 |

| 5 | Depression | 0.60 (0.82) | 0.66 | 0.70 |

| 6 | Stress | 0.67 (0.84) | 0.64 | 0.65 |

| 7 | Anxiety | 0.49 (0.79) | 0.57 | 0.66 |

| 8 | Stress | 0.56 (0.83) | 0.61 | 0.67 |

| 9 | Anxiety | 0.58 (0.81) | 0.66 | 0.73 |

| 10 | Depression | 0.55 (0.85) | 0.65 | 0.73 |

| 11 | Stress | 0.56 (0.80) | 0.72 | 0.79 |

| 12 | Stress | 0.52 (0.80) | 0.62 | 0.72 |

| 13 | Depression | 0.59 (0.81) | 0.67 | 0.73 |

| 14 | Stress | 0.61 (0.81) | 0.65 | 0.71 |

| 15 | Anxiety | 0.52 (0.81) | 0.65 | 0.74 |

| 16 | Depression | 0.55 (0.81) | 0.65 | 0.74 |

| 17 | Depression | 0.51 (0.81) | 0.63 | 0.76 |

| 18 | Stress | 0.60 (0.83) | 0.63 | 0.69 |

| 19 | Anxiety | 0.50 (0.79) | 0.61 | 0.70 |

| 20 | Anxiety | 0.52 (0.80) | 0.64 | 0.75 |

| 21 | Depression | 0.56 (0.90) | 0.64 | 0.74 |

All item-total correlations and factor loadings significant at the P<0.001 level. SD – Standard deviation

DISCUSSION

This study is the first to report on the factor structure of the DASS-21 among Indian adults. The results indicated a good fit to the data for the three- and one-factor models. There were no substantial differences in the model fit. The high zero-order correlations, and high covariances between the factors in the three-factor model, indicated that these subscales have little divergence with one another, and could be described as measuring a common underlying factor of psychological distress.

The individual DASS items strongly predicted the underlying factors in the three- and one-factor models, although the first item on the stress subscale loaded relatively less strongly. This suggests that the expression “winding down” may not be understood in the Indian population as referring to relaxing and therefore is not a strong predictor of the stress subscale or general psychological distress. Otherwise, the factor loadings were more consistently strong in this study compared to findings of an English version among Indian adolescents.[8] It is possible that the older age of participants in this study, relative to the adolescents, entailed more experience with the English language, and therefore a more accurate interpretation of the meaning of DASS items.

The implication of these findings is that the items of the DASS-21 assess an underlying construct of psychological distress among Indian adults, and that the subscales overlap so substantially that they may not validly discriminate between different emotional states. This may explain why the subscales show very similar magnitudes of correlations with other variables in previous studies in India.[11,14,15,20,21] For example, the subscales show very similar strength of relationship with poor health behaviors,[12] sense of humor,[20] symptoms of internet addiction,[15,21] academic-related variables,[22] and coping and resilience.[23] Practically then, researchers intending to examine whether depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms are differentially associated with others variable may wish to choose measures that have more specificity in assessing these emotional states. Clinically, however, scores on individual items may still be useful in assessing the individual expression of psychological distress and targeting specific symptoms.

Modifications may be made to the first stress item that was a poor predictor, or this first item may be removed when using the measure. Previous studies on the psychometric properties of the DASS in Asian countries have also indicated removal of some stress-related items to improve the validity,[5] suggesting that cultural differences affect the validity of these items in cleanly assessing the underlying construct of stress.

This is the first study of an English-language DASS in Indian adults, and therefore future studies are needed to assess the replicability of these findings. Several limits to generalizability are notable, including the restricted age range and the sample being recruited from one geographic area in India. With regard to future studies, a larger age range would be beneficial, to assess whether the scale operates differently in later adulthood. Further, factor analysis of the full DASS-42 scale might indicate other items that perform better in discriminating the underlying factors, both in factor structure, and for criterion validity with other depression, anxiety, and stress measures.

CONCLUSION

The findings from this sample suggest that the DASS-21 items assess general psychological distress in Indian adults, with little evidence that responses to the items are indicative of three latent subscales.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lovibond PF, Lovibond SH. The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behav Res Ther. 1995;33:335–43. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antony MM, Bieling PJ, Cox BJ, Enns MW, Swinson RP. Psychometric properties of the 42-item and 21-item versions of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales in clinical groups and community sample. Psychol Assess. 1998;10:176–81. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bottesi G, Ghisi M, Altoè G, Conforti E, Melli G, Sica C. The Italian version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales-21: Factor structure and psychometric properties on community and clinical samples. Compr Psychiatry. 2015;60:170–81. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2015.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mellor D, Vinet EV, Xu X, Mamat NH, Richardson B, Román F. Factorial invariance of the DASS-21 among adolescents in four countries. Eur J Psychol Assess. 2015;31:138–42. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oei TP, Sawang S, Goh YW, Mukhtar F. Using the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale 21 (DASS-21) across cultures. Int J Psychol. 2013;48:1018–29. doi: 10.1080/00207594.2012.755535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patel V, Xiao S, Chen H, Hanna F, Jotheeswaran AT, Luo D, et al. The magnitude of and health system responses to the mental health treatment gap in adults in India and China. Lancet. 2016;388:3074–84. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00160-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singh B, Prabhuappa KP, Eqbal S, Singh AR. Depression, anxiety and stress scale: Reliability and validity of Hindi adaptation. Int J Edu Manage Stud. 2013;3:446–9. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singh K, Junnarkar M, Sharma S. Anxiety, stress, depression, and psychosocial functioning of Indian adolescents. Indian J Psychiatry. 2015;57:367–74. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.171841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown TA, Chorpita BF, Korotitsch W, Barlow DH. Psychometric properties of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) in clinical samples. Behav Res Ther. 1997;35:79–89. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(96)00068-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Norton PJ. Depression Anxiety and Stress Scales (DASS-21): Psychometric analysis across four racial groups. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2007;20:253–65. doi: 10.1080/10615800701309279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iqbal S, Gupta S, Venkatarao E. Stress, anxiety and depression among medical undergraduate students and their socio-demographic correlates. Indian J Med Res. 2015;141:354–7. doi: 10.4103/0971-5916.156571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Merchant HH, Mulkalwar AA, Nayak AS. A study to assess the prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress among undergraduate medical students across the state of Maharashtra, India. Global J Res Analysis. 2018;7:8–13. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sahoo S, Khess CR. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress among young male adults in India: A dimensional and categorical diagnoses-based study. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2010;198:901–4. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181fe75dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Waghachavare VB, Dhumale GB, Kadam YR, Gore AD. A study of stress among students of professional colleges from an Urban area in India. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2013;13:429–36. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yadav P, Banwari G, Parmar C, Maniar R. Internet addiction and its correlates among high school students: A preliminary study from Ahmedabad, India. Asian J Psychiatr. 2013;6:500–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2013.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosseel Y. Lavaan: An R Package for Structural Equation Modeling and More Version 05–12 (BETA) 2010. Ghent, Belgium: Ghent University; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li CH. Confirmatory factor analysis with ordinal data: Comparing robust maximum likelihood and diagonally weighted least squares. Behav Res Methods. 2016;48:936–49. doi: 10.3758/s13428-015-0619-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struc Equat Model Multidis J. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheung GW, Rensvold RB. Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Struc Equat Model. 2002;9:233–55. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Madhan B, Barik AK, Patil R, Gayathri H, Reddy MS. Sense of humor and its association with psychological disturbances among dental students in India. J Dent Educ. 2013;77:1338–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meena PS, Soni R, Jain M, Paliwal S. Social networking sites addiction and associated psychological problems among young adults: A study from North India? SL J Psychiatry. 2015;6:14–6. doi:10.4038/sljpsyc.v6i1.8055/ [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bhasin SK, Sharma R, Saini NK. Depression, anxiety and stress among adolescent students belonging to affluent families: A school-based study. Indian J Pediatr. 2010;77:161–5. doi: 10.1007/s12098-009-0260-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stanley S, Mettilda Bhuvaneswari G. Stress, anxiety, resilience and coping in social work students (a study from India) Social Work Educ. 2016;35:78–88. [Google Scholar]