Abstract

Infectious bronchitis (IB), caused by avian IB virus (IBV), is an acute and highly contagious disease of chickens. From 2016 to 2018, 56 IBV strains were isolated and identified from clinical samples obtained from various chicken farms located in central China. The S1 sequencing of these strains revealed nucleotide and amino acid identities of 70.2 to 100% and 62.6 to 100%, respectively, compared with those of reference strains. Phylogenetic analysis indicated that the genotypes of the isolates included GI-13 (4/91), GI-7 (TW-I), GI-24 (Mass), GI-19 (QX), and GI-18 (LDT3-A), with GI-19 (QX) being the predominant genotype. Meanwhile, GI-13 (4/91) was the second most dominant genotype in Henan Province, whereas it was GI-7 (TW-I) in Hunan and Hubei provinces. Recombination analysis of 3 variant strains showed that CK/CH/HeN/20160113 might be a recombination of LDT3-A- and QX-type strains and that CK/CH/HeN/20160316 might be a recombination of Italy-02-type strain and CK-CH-LJS08II. The predicted tertiary structure between CK/CH/HeN/20160113 and LDT3-A-type strain revealed that the novel 336 (L-P) and 455 (S-A) mutations changed the structure from an alpha helix to a random crimp. In addition, the 275 (Y-F) site reduced the length of the β-sheet, whereas the site 353 (A-T) extended the β-sheet. These findings suggested that GI-19 (QX) remains the predominant genotype in central China, and a locally determined complex genotype associated with variable clinical symptoms exists related to gene recombination and mutations.

Key words: epidemiological investigation, infectious bronchitis virus, S1 glycoprotein, recombination analysis, tertiary protein structure analysis

Introduction

Avian infectious bronchitis (IB) is caused by avian IB virus (IBV) and poses an economic threat to poultry farms worldwide (Stern and Sefton, 1982). IBV has a wide range of hosts, but researchers generally believe that its natural hosts are gallus and pheasants (Cavanagh et al., 1986). In chickens, IBV infection mainly causes respiratory tract infection, nephritis, decline in productivity, and other symptoms (Cavanagh, 2007). Infection of layers can not only cause related clinical symptoms but also cause permanent irreversible damage to their reproductive system, presenting as a loss of the maximum egg production and decreasing the quantity and quality of egg production. Some IBV strains can also cause intestinal, glandular, and muscular diseases (Song et al., 1998, Gelb et al., 2005). IB is one of the major infectious diseases that severely affect the poultry industry worldwide. At present, vaccines remain the most important means of its prevention and control, among which live attenuated vaccines are the most widely used (Bande et al., 2015).

IBV belongs to the Gammacoronavirus genus of the Coronaviridae family and Nidovirales order. Its viral genome encodes structural and nonstructural proteins. Structural proteins include the spike proteins S1 and S2, membrane protein M, nucleocapsid protein N, and small membrane protein E (Xu et al., 2018). S1 is a glycoprotein that plays an important role in virus adsorption and neutralization of antibody production (Cavanagh, 1983). IBV replication relies on RNA polymerase, which lacks correction ability (Smati et al., 2002). Therefore, the virus is prone to mutation or recombination during replication. With the added pressure of antibodies produced by the use of vaccines, the genetic variation of IBV is further accelerated; the large variation in S1 among different strains results in a weakened degree of cross-protection between strains (Lai and Cavanagh, 1997). S1 protein is the most variable protein in IBV (Casais et al., 2003). The insertion, deletion, point mutation, or recombination of the nucleotide sequence of S1 can directly lead to the emergence of many serotypes/genotypes (Sapats et al., 1996). Therefore, an S1-based sequence difference analysis is the focus of the molecular epidemiological investigation of IBV (Han et al., 2011, Feng et al., 2014).

In this study, we conducted an IB epidemiological survey in chicken farms located in 3 provinces in central China mainly involved in the chicken industry in 2016–2018: Henan, Hunan, and Hubei provinces. We performed evolutionary genetic and recombination analyses on the isolated IBV strain S1 to understand the epidemiological spread of IBV in chickens in China.

Materials and methods

Clinical Samples and Virus Isolation

Tissue samples of the trachea, lungs, and kidneys were collected from dead chickens suspected of IBV infection in 151 chicken farms located in Henan, Hubei, and Hunan provinces of China in 2016–2018. Most of the flocks had been vaccinated against IB with commercial live attenuated vaccines. The tissue samples were pooled together from chickens from the same flock, soaked in liquid nitrogen, and ground into a fine powder. Then, 5 times the volume of frozen PBS buffer solution containing 200 U/mL of penicillin and 200 μg/mL of streptomycin was added and mixed. After 3 repeated freezing–thawing cycles, the suspension was centrifuged at 5,000 × g for 10 min, and 0.2 mL of the supernatant filtrate was inoculated into the allantoic cavity of 9-day-old embryonated specific pathogen-free chicken eggs purchased from Beijing Merial Vital Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd., and the allantoic fluid of the chicken embryo was collected after incubation at 37°C for 48 h so as to repeat at least 3 blind passages.

Total RNA of virus from chicken embryo allantoic fluid was extracted after 3 generations of blind transmission for reverse transcription (RT)-PCR detection using specific primer sets targeting M (forward: 5′-CCTAAGAACGGTTGGAAT-3′ and reverse: 5′-TACTCTCTACACACACAC-3′) and 3′UTR (forward: 5′-GGAAGATAGGCATGTAGCTT-3′ and reverse: 5′-CTAACTCTATACTAGCCTAT-3′) for IBV detection using RT-PCR.

Cloning and Sequencing of S1

According to the IBV sequence published in GenBank, the primer pair (forward: 5′-AAGACTGAACAAAACCGACT-3′ and reverse: 5′-CAAAACCTGCCATAACTAACATA-3′) was used to amplify S1 by referring to the instructions of the TransScript One-Step RT-PCR SuperMix Kit (TransGen Biotechnology, Inc., Beijing, China) using the total RNA extracted from virus from chicken embryo allantoic fluid as the template: RT-PCR was performed by reverse transcription at 45°C for 30 min followed by 30 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 30 s, annealing at 55°C for 30 s, and extension at 72°C for 90 s, with a final extension at 72°C for 10 min. RT-PCR products were linked to pMD18-T (Suzhou Hongxun Biotechnology Co., Ltd., China) for sequencing.

Identity and Recombination Analyses of the S1 Sequence

The SeqMan program of the Lasergene 7.1 software package (DNASTAR Inc., Madison, WI) was used to assemble the S1 sequence of IBV isolates. Identity analysis was performed with reference to the S1 sequence of 56 IBV strains obtained from GenBank (Table 1). The Clustal W model in MEGA 6.0 was used for multisequence alignment (Tamura et al., 2013). The neighbor-joining method (bootstrap = 1,000) was used to construct a phylogenetic tree of S1 for IBV isolates and reference strains, whereas EvolView 2 (http://www.evolgenius.info/evolview/) was used for visualizing and annotating clusters. Simplot 3.5.1 (http://sray.med.som.jhmi.edu/SCRoftware/simplot/) was used to conduct sequence recombination analysis of the S1 sequences of field and reference strains. RDP, GENECONV, MAXCHI, and BOOTSCAN methods of RDP v.4.36 were used to further analyze and confirm recombination events (Martin et al., 2015).

Table 1.

Background and S1 information of domestic isolates of IBV from 2016 to 2018.

| IBV isolates | Province1 | Date (day-month-year) | Production type | Vaccination history | Clinical type | Length of S1 (nt/aa)2 | Cleavage recognition motifs3 | Accession no. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CK/CH/HeN/20180409 | Henan | 09-04-2018 | Broiler | H120 | NP | 1,617/539 | RRSRR4 | MN615458 |

| CK/CH/HuB/20180911 | Hubei | 11-09-2018 | Layer | H120 + LDT3 | EPA | 1,617/539 | RRSRR | MN615454 |

| CK/CH/HeN/20180129 | Henan | 29-01-2018 | Broiler | H120 + LDT3 | RS | 1,617/539 | RRSRR | MN615459 |

| CK/CH/HeN/20180102 | Henan | 02-01-2018 | Broiler | H120 | NP | 1,620/540 | RRSRR | MN615470 |

| CK/CH/HeN/20180123 | Henan | 23-01-2018 | Broiler | H120 | NP | 1,617/539 | RRSRR | MN615464 |

| CK/CH/HeN/20160926 | Henan | 26-09-2016 | Broiler | N/A | NP | 1,620/540 | RRSRR | MN615447 |

| CK/CH/HuN/20180415 | Hunan | 15-04-2018 | Broiler | H120 + LDT3 | NP | 1,620/540 | RRSRR | MN615465 |

| CK/CH/HeN/20180326 | Henan | 26-03-2018 | Layer | H120 + LDT3 | EPA | 1,617/539 | RRSRR | MN615462 |

| CK/CH/HeN/20161208 | Henan | 08-12-2016 | Broiler | H120 + LDT3 | NP | 1,617/539 | HRRRR | MN615445 |

| CK/CH/HuB/20170317 | Hubei | 17-03-2017 | Broiler | H120 | NP | 1,620/540 | HRRRR | MN615456 |

| CK/CH/HuN/20161023 | Hunan | 23-10-2016 | Broiler | H120 | RS | 1,611/537 | RRFRR | MN615433 |

| CK/CH/HuN/20171127 | Hunan | 27-11-2017 | Broiler | H120 + LDT3 | NP | 1,632/544 | RRFRR | MN615471 |

| CK/CH/HuB/20180103 | Hubei | 03-01-2018 | Broiler | H120 + 4/91 | NP | 1,620/540 | RRFRR | MN615469 |

| CK/CH/HeN/20180310 | Henan | 10-03-2018 | Broiler | H120 | RS | 1,620/540 | HRRRR | MN615463 |

| CK/CH/HuB/20170929 | Hubei | 29-09-2017 | Broiler | H120 + 4/91 | NP | 1,620/540 | HRRRR | MN615477 |

| CK/CH/HuB/20170107 | Hubei | 07-01-2017 | Broiler | H120 + LDT3 | RS | 1,620/540 | HRRRR | MN615473 |

| CK/CH/HuN/20170122 | Hunan | 22-01-2017 | Broiler | H120 + 4/91 | NP | 1,620/540 | HRRRR | MN615466 |

| CK/CH/HuB/20161019 | Hubei | 19-10-2016 | Layer | H120 + 4/91 | EPA | 1,620/540 | RRFRR | MN615444 |

| CK/CH/HuN/20170720 | Hunan | 20-07-2017 | Layer | H120 + LDT3 | EPA | 1,620/540 | RRFRR | MN615453 |

| CK/CH/HeN/20161114 | Henan | 14-11-2016 | Broiler | H120 + LDT3 | NP | 1,620/540 | RRFRR | MN615446 |

| CK/CH/HuN/20160229 | Hunan | 29-02-2016 | Broiler | N/A | RS | 1,620/540 | RRFRR | MN615443 |

| CK/CH/HuB/20160411 | Hubei | 11-04-2016 | Broiler | H120 + LDT3 | R.S | 1,620/540 | RRFRR | MN615442 |

| CK/CH/HuN/20180323 | Hunan | 23-03-2018 | Broiler | H120 + 4/91 | NP | 1,620/540 | RRFRR | MN615472 |

| CK/CH/HuB/20170218 | Hubei | 18-02-2017 | Broiler | H120 | NP | 1,620/540 | RRFRR | MN615457 |

| CK/CH/HeN/20161108 | Henan | 08-11-2016 | Broiler | H120 + 4/91 | NP | 1,620/540 | RRFRR | MN615437 |

| CK/CH/HeN/20160406 | Henan | 06-04-2016 | Broiler | N/A | NP | 1,620/540 | RRFRR | MN615449 |

| CK/CH/HuN/20160909 | Hunan | 09-09-2016 | Broiler | H120 | NP | 1,620/540 | HRRKR | MN615448 |

| CK/CH/HuB/20170418 | Hubei | 18-04-2017 | Broiler | H120 | NP | 1,620/540 | HRRKR | MN615467 |

| CK/CH/HuB/20160901 | Hubei | 01-09-2016 | Layer | H120 + LDT3 | EPA | 1,620/540 | HRRRR | MN615435 |

| CK/CH/HuB/20160412 | Hubei | 12-04-2016 | Broiler | H120 | NP | 1,620/540 | HRRRR | MN615450 |

| CK/CH/HuB/20171124 | Hubei | 24-11-2017 | Broiler | H120 + 4/91 | NP | 1,620/540 | HRRRR | MN615475 |

| CK/CH/HeN/20161009 | Henan | 09-10-2016 | Broiler | H120 + LDT3 | NP | 1,620/540 | HRRRR | MN615439 |

| CK/CH/HuB/20160928 | Hubei | 28-09-2016 | Broiler | H120 + LDT3 | NP | 1,620/540 | HRRRR | MN615440 |

| CK/CH/HeN/20170115 | Henan | 15-01-2017 | Broiler | H120 + 4/91 | RS | 1,620/540 | HRRRR | MN615479 |

| CK/CH/HuN/20161119 | Hunan | 19-11-2016 | Broiler | H120 | NP | 1,620/540 | HRRRR | MN615441 |

| CK/CH/HeN/20160902 | Henan | 02-09-2016 | Broiler | H120 | NP | 1,620/540 | HRRRR | MN615429 |

| CK/CH/HuB/20170920 | Hubei | 20-09-2017 | Broiler | H120 | NP | 1,620/540 | HRRRR | MN615474 |

| CK/CH/HuN/20170402 | Hunan | 02-04-2017 | Broiler | H120 + LDT3 | RS | 1,620/540 | HRRRR | MN615468 |

| CK/CH/HeN/20161129 | Henan | 29-11-2016 | Broiler | H120 + LDT3 | NP | 1,620/540 | HRRRR | MN615434 |

| CK/CH/HeN/20160330 | Henan | 30-03-2016 | Broiler | N/A | RS | 1,620/540 | HRRRR | MN615438 |

| CK/CH/HuB/20180524 | Hubei | 24-05-2018 | Broiler | H120 + 4/91 | RS | 1,620/540 | HRRRR | MN615461 |

| CK/CH/HeN/20180923 | Henan | 23-09-2018 | Broiler | H120 + 4/91 | RS | 1,620/540 | HRRRR | MN615425 |

| CK/CH/HeN/20181120 | Henan | 20-11-2018 | Broiler | H120 | RS | 1,620/540 | HRRRR | MN615427 |

| CK/CH/HuB/20180420 | Hubei | 20-04-2018 | Broiler | H120 + 4/91 | NP | 1,620/540 | HRRRR | MN615455 |

| CK/CH/HuB/20180511 | Hubei | 11-05-2018 | Broiler | H120 + 4/91 | RS | 1,620/540 | HRRRR | MN615478 |

| CK/CH/HeN/20180303 | Henan | 03-03-2018 | Layer | H120 + LDT3 | EPA | 1,620/540 | HRLRR | MN615424 |

| CK/CH/HeN/20180304 | Henan | 04-03-2018 | Broiler | H120 + 4/91 | NP | 1,620/540 | HRRRR | MN615426 |

| CK/CH/HeN/20160516 | Henan | 16-05-2016 | Broiler | H120 | NP | 1,620/540 | HRRRR | MN615431 |

| CK/CH/HuB/20160219 | Hubei | 19-02-2016 | Broiler | N/A | NP | 1,620/540 | HRRRR | MN615452 |

| CK/CH/HuN/20160414 | Hunan | 14-04-2016 | Broiler | H120 | NP | 1,620/540 | HRRRR | MN615436 |

| CK/CH/HuB/20180227 | Hubei | 27-02-2017 | Broiler | H120 + 4/91 | RS | 1,620/540 | HRRRR | MN615460 |

| CK/CH/HuB/20160922 | Hubei | 22-09-2016 | Broiler | H120 | NP | 1,623/541 | HRRRR | MN615432 |

| CK/CH/HuN/20170206 | Hunan | 06-02-2017 | Broiler | N/A | RS | 1,620/540 | HRRRR | MN615476 |

| CK/CH/HeN/20160316 | Henan | 16-03-2016 | Layer | H120 + LDT3 | EPA | 1,620/540 | RRSRR | MN615430 |

| CK/CH/HeN/20160113 | Henan | 13-01-2016 | Broiler | N/A | NP | 1,620/540 | RRFRR | MN615451 |

| CK/CH/HeN/20181207 | Henan | 07-12-2018 | Layer | H120 + 4/91 | EPA | 1,614/538 | RRSRR | MN615428 |

Abbreviations: IBV, infectious bronchitis virus; NP, nephropathogenic; EPA, egg production abnormal; RS, respiratory; N/A, data not available.

Province where the viruses were isolated.

Length of nucleotides and deduced amino acids of S1.

Cleavage recognition motifs of S1.

R, arginine; F, phenylalanine; H, histidine; T, threonine; K, lysine; L, leucine; S, serine.

Prediction of the Tertiary Structure of the S1 Protein

To visually reflect S1 protein difference between the variant strain CK/CH/HeN/20160113 and the vaccine strain LDT3-A, which was one of the most widely used live vaccine strains, the SWISS-MODEL (https://swissmodel.expasy.org/interactive) was used to predict the tertiary structure. The tertiary structure of amino acid residues obtained from the SWISS-Prot database was modified by PyMol (Alexander et al., 2011).

Results

Epidemic Information and S1 Sequence of Clinical Samples

From 2016 to 2018, a total of 56 IBV isolates were isolated from various broiler and layer farms in Hubei (n = 20, 35.71%), Hunan (n = 12, 21.43%), and Henan (n = 24, 42.86%) provinces (collected in 2016, n = 25; 2017, n = 13; and 2018, n = 18). The accession numbers and clinical information of each strain are summarized in Table 1. Nucleic acids, amino acid sequence length, and cleavage site of S1 of the 56 IBV isolates were analyzed. Within S1, there were 6 different nucleotide (1,611, 1,614, 1,617, 1,620, 1,623, and 1,632) and deduced amino acid (537, 538, 539, 540, 541, and 544) lengths. The most common S1 comprised 1,620 nucleotides, accounting for 82.14% of the total IBV isolates, and there were 5 types of cleavage sites including HRRRR, RRFRR, HRLRR, HRRKR, and RRSRR, all of which are similar to those reported previously (Feng et al., 2014).

Evolutionary Genetic Analysis of S1

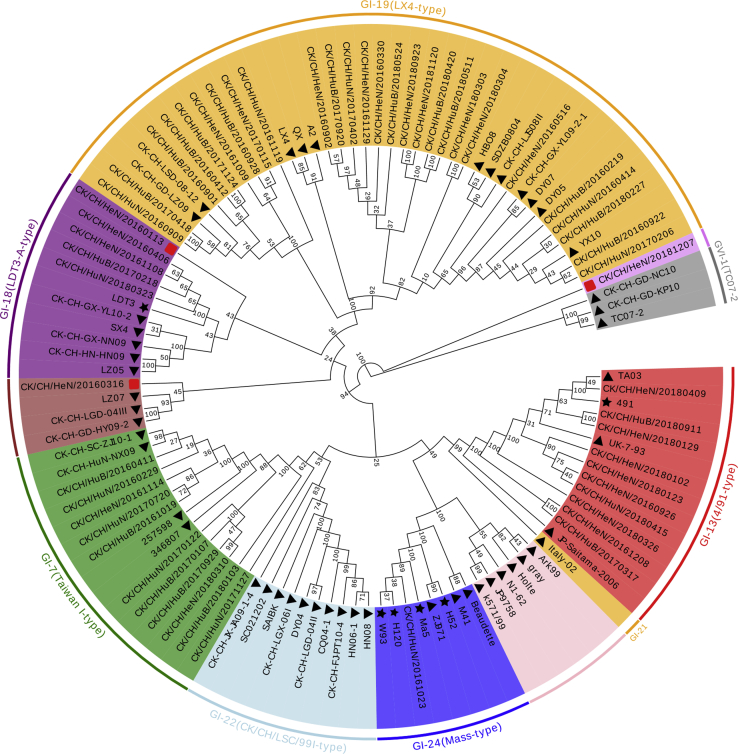

The phylogenetic tree of S1 of the 56 foreign reference strains and 56 IBV isolates was constructed using MEGA 6.0 (Figure 1). As shown in Figure 1, 112 strains comprising 7 genotypes, that is, GI-19 (QX), GI-22, GI-13 (4/91), GI-24 (Mass), GI-18 (LDT3-A), GVI-1, and GI-7 (TW-I), were obtained. Three isolates, CK/CH/HeN/20181207, CK/CH/HeN/20160316, and CK/CH/HeN/20160113, formed independent evolutionary branches and were considered variant strains. The reference strains, except the introduced 4/91- and Mass-type vaccine strains, showed clustering with the domestic IBV isolates; however, other reference strains such as Gray, Hotle, Ark99, N1-62, JP9758, and k571/99 did not exhibit clustering with the domestic IBV isolates in this study, indicating a large evolutionary distance.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic analysis of S1 of infectious bronchitis virus strain in chicken farms in 3 provinces in China during 2016–2018. The phylogenetic trees were computed using the neighbor-joining method with 1,000 bootstrap replicates using MEGA 6.0. “▲” represents the reference sequence downloaded from GenBank. “★” represents the vaccine strain. “▪” represents the variant strains in the study. Unmarked strains represent the strains isolated in this study.

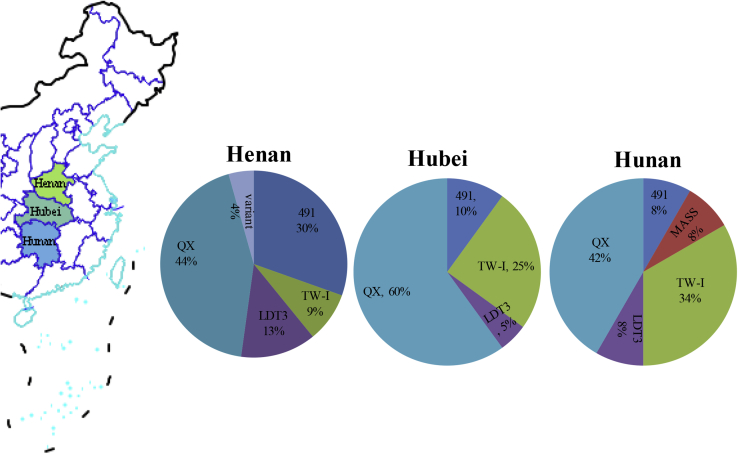

The genotypes of isolates from different regions are shown in Figure 2. The 56 IBV isolates comprised 5 main genotypes, that is, GI-13 (4/91), GI-7 (TW-I), GI-24 (Mass), GI-19 (QX), and GI-18 (LDT3-A). GI-24 (Mass) was composed of only one IBV isolate from Hunan Province, and it accounted for 1.78% of the total IBV isolates. In addition, there were 11, 10, 5, and 27 TW-I–, 4/91-, LDT3-A–, and QX-type isolates, accounting for 17.8, 19.6, 8.9, and 48.2% of the total isolates, respectively. As shown in Figure 2, GI-13 (4/91), GI-7 (TW-I), GI-18 (LDT3-A), and GI-19 (QX) were found in the 3 provinces, with GI-19 (QX) being the predominant genotype in all provinces. In Henan Province, GI-13 (4/91) was the second largest genotype among those investigated, whereas in Hunan and Hubei provinces, this position was occupied by GI-7 (TW-I). In addition, GI-24 (Mass) was found only in Hunan Province, and variant strains were found only in Henan Province.

Figure 2.

Genotype proportion and geographic distribution of infectious bronchitis virus isolates.

Similarity Analysis of S1

The nucleotide and amino acid sequences of S1 of the 56 domestic IBV isolates were aligned using Clustal-X, and similarity was analyzed by MegAlign of the Lasergene 7.1 software package (DNASTAR Inc.). The results showed that the nucleotide and amino acid sequence similarities were 66.9 to 100% and 63.5 to 100%, respectively. The largest differences between nucleotides and amino acid sequences were observed in CK/CH/HeN/20181207 and CK/CH/HuB/20160411 (66.9 vs. 63.5%). Only CK/CH/HuB/20180420 and CK/CH/HuB/20180511, both of which were QX-type strains, showed a nucleotide sequence similarity of 100% for S1. According to different genotypes, the IBV isolates in this study were compared with common vaccine strains (LDT3, 4/91, and Mass) reported in GenBank (Table 2). Mass-type vaccine strains included H120, H52, Ma5, and W93. The isolates of each genotype had the highest similarity with the corresponding vaccine strain S1. GI-7 (TW-I) did not have any equivalent vaccine strain, and the similarity of S1 was low with the 3 major vaccine strains.

Table 2.

Similarity in nucleotides and amino acids between isolate strains and vaccine strains.

| Isolated strains of various genotypes | Vaccine strains |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| LDT3 | 4/91 | Mass | |

| GI-13 (4/91) type (n = 10) | 78.0–80.1% (nt)/75.1–77.0% (aa) | 96.3–99.8% (nt)/94.2–99.3% (aa) | 77.1–78.5% (nt)/73.3–75.6% (aa) |

| GI-7 (TW-I) (n = 11) | 81.7–84.4% (nt)/78.3–82.2% (aa) | 76.7–78.3% (nt)/73.8–77.8% (aa) | 80.0–81.8% (nt)/78.0–81.9% (aa) |

| GI-18 (LDT3) (n = 4) | 99.0–99.1% (nt)/97.6–98% (aa) | 78.4–78.7% (nt)/74.8–75.3% (aa) | 81.6–82.3% (nt)/79.7–80.6% (aa) |

| GI-19 (QX) (n = 27) | 84.7–85.7% (nt)/82.6–84.8% (aa) | 77.7–78.6% (nt)/77.4–79% (aa) | 76.6–78.0% (nt)/75.0–77.4% (aa) |

| GI-24 (Mass) (n = 1) | 82.2% (nt)/79.7% (aa) | 78.2% (nt)/74.7% (aa) | 99.1–99.8% (nt)/98.5–99.8% (aa) |

| CK/CH/HeN/20180316 (n = 1) | 86.3% (nt)/84.4% (aa) | 88.9% (nt)/86.5% (aa) | 78.0–78.5% (nt)/75.7–76.5% (aa) |

| CK/CH/HeN/20160113 (n = 1) | 89.8% (nt)/88.3% (aa) | 78.4% (nt)/77.0% (aa) | 79.6–80.1% (nt)/77.1–77.8% (aa) |

| CK/CH/HeN/20181207 (n = 1) | 70.3% (nt)/65.8% (aa) | 71.6% (nt)/66.7% (aa) | 69.8–70.2% (nt)/66.6–67.4% (aa) |

Recombination Analysis of S1

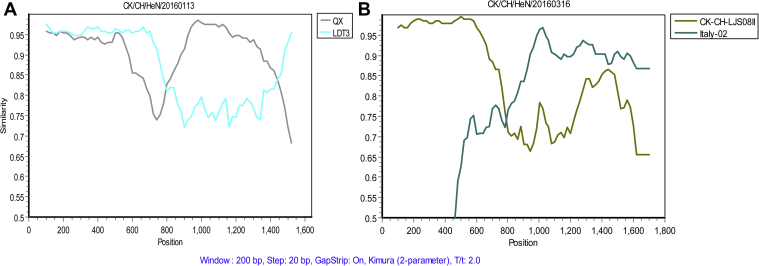

Three isolates did not cluster with the reference strains and formed an independent evolutionary branch, called a variant strain. RDP4 and Simplot recombination analysis software were used to detect recombination in S1 of the 3 variant strains: CK/CH//HeN/20160113, CK/CH/HeN/20160316, and CK/CH/HeN/20181207. The results showed that no recombination events occurred in CK/CH/HeN/20181207. The variant strain CH/CK/HeN/20160113 possibly originated from the recombination of QX-type variant strain (major parent) and LDT3-type variant strain (minor parent) (Figure 3); as shown in Table 3, recombination occurred between nucleotides 820 and 1,478. The similarity between nucleotides 820 to 1,478 and QX-type variant strain was 93.7%, whereas that between the rest of S1 and LDT3-type variant strain was 94.5%. RDP and Simplot recombination analysis showed that CK/CH/HeN/20160316 may be derived from recombination between Italy-02–type variant strain and CK-CH-LJS08II, which occurred between nucleotides 11 and 701. This region (11–701) was 98% identical to that in CK-CH-LJS08II, whereas the rest of S1 showed an 89.3% similarity to Italy-02–type variant strain. Italy-02–type variant strain and CK-CH-LJS08II are GI-21 and GI-19 (QX) types, respectively.

Figure 3.

Recombination occurrence was analyzed using the Simplot method. (A) The variant strain CK/CH/HeN/20160113 may have originated from the recombination of QX- and LDT3-type vaccine strains. (B) CK/CH/HeN/20160316 may be derived from recombination between Italy-02 and CK-CH-LJS08II vaccine strains.

Table 3.

RDP v.4.36 recombination analysis of S1 of variants strains.

| Recombinant sequence | Breakpoint position |

Major parent1 |

Minor parent2 |

P-value3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Begin | End | Strain similarity | Strain similarity | ||||

| CK/CH/HeN/20160113 | 820 | 1,478 | LDT3 | 94.5% | QX | 93.7% | 5.884E−12 |

| CK/CH/HeN/20160316 | 11 | 701 | Italy-02 | 89.3% | CK-CH-LJS08II | 98% | 1.01E−29 |

Major parent: parent contributing to the larger fraction of the sequence.

Minor parent: parent contributing to the smaller fraction of the sequence.

P-value: P-value of RDP method.

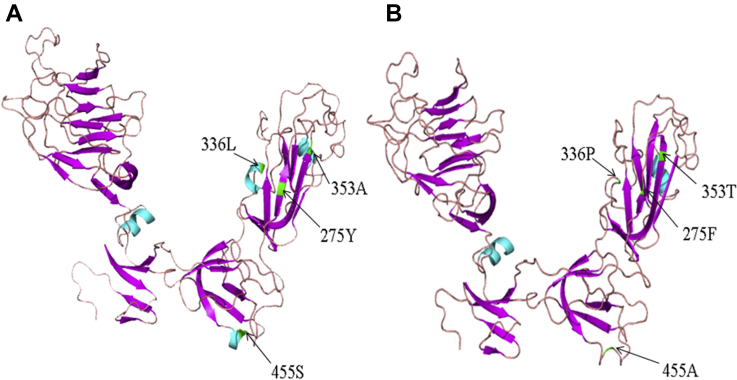

Prediction of the Tertiary Structure for the Key Mutation Loci

The tertiary structures of CH/CK/HeN/20160113 and LDT3-type variant strain were modeled using the SWISS-MODEL homology modeling server. Compared with the LDT3-type variant strain, CH/CK/HeN/20160113 had many mutations. The 336 (L-P) and 455 (S-A) mutations changed their structure from an alpha helix to a random crimp. Moreover, the 275 (Y-F) site reduced the length of the β-sheet, whereas the site 353 (A-T) extended it (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Cartoon scheme view of the S1 protein structure. (A) S1 protein structure of LDT3-type vaccine strain. (B) S1 protein structure of CK/CH/HeN/20160113.

Discussion

In this study, isolates recently collected from central China were categorized into 6 main genotypes; the most abundant genotype was GI-19 (QX). Since its discovery in 1996, GI-19 (QX) has become the most prevalent strain in China (Feng et al., 2017). Subsequently, GI-19 (QX) has been reported in most parts of the world as a strain causing serious economic losses (Bochkov et al., 2006, Valastro et al., 2010, Sigrist et al., 2012). In 2016–2018, an epidemiological survey conducted on IBV in farms located in Henan, Hubei, and Hunan provinces showed that the prevalence of GI-19 (QX) was high, accounting for 48.2% of the 56 isolates. Furthermore, it remained the main epidemic strain in all 3 provinces. It is possible that GI-19 (QX) originated in China, and the development of trade may be the cause of the extensive spread of this genotype in China. Moreover, the spread could be due to the abundant poultry farms in China and the frequent IB mixing with low pathogenic avian influenza, mycoplasma, and other infections, thereby causing immunosuppression and making IBV infection easier in vaccinated chickens (Georgiades et al., 2001, Vandekerchove et al., 2004, Dwars et al., 2009). At present, vaccines are the main means of prevention and control of IBV, but for epidemic QX-type strains, recombination and mutation of strains may occur under the pressure of vaccines and conditions of natural selection, which limits prevention and control by vaccines. In China, the genotype GI-19 (QX) vaccine was just approved in 2018 (data from the National Veterinary Drug Basic Information Database of China) and would be used before long; the continuous emergence of IBV variants calls for constantly updated vaccines and procedures according to the locally determined genotype.

GI-7 (TW-I) accounted for 19.6% of the total isolates. The TW-I–type strain was first isolated from Taiwan, and the proportion of this strain increased annually according to previous reports (Feng et al., 2017), perhaps because there is no commercial vaccine against TW-I–type IBVs yet. Furthermore, GI-13 (4/91), GI-24 (Mass), and GI-18 (LDT3-A) accounted for 17.8, 8.9, and 1.78% of the total isolates, respectively. Each of the 3 genotypes has a corresponding commercial vaccine. Compared with the other 2 genotypes, only one Mass-type strain was found, and the nucleotide similarity of the Mass-type vaccine strain was as high as 99.1 to 99.8% to the reference strain, indicating that the prevalence of Mass-type IBVs was relatively less. Whether this strain originated from a live Mass-type vaccine strain remains to be determined.

The co-circulation of multiple IBV genotypes and increase in the proportion of IBV variant strains accelerate the possibility of recombination of virus strains, which poses a great challenge for vaccination control of IBV (Ali et al., 2018, Yan et al., 2019, Zhang et al., 2020). It may also be one of the reasons for the increase in the proportions of LDT3-A– and 4/91-type strains. The 3 variant strains showed low identity with major vaccine strains used in China. Nucleotide similarity between CK/CH/HeN/20160316 and 4/91-, LDT3-A–, and Mass-type vaccine strains ranged from 78.0 to 88.9%, with the similarity between CK/CH/HeN/20160316 and Mass-type vaccine strain being the lowest. The nucleotide and amino acid similarities of CK/CH/HeN/20160113 with the vaccine strains were 78.4 to 89.8% and 77.0 to 88.3%, respectively. In contrast, the nucleotide and amino acid similarities between CK/CH/HeN/20181207 and the 3 vaccine strains were the lowest at 69.8 to 71.6% and 65.8 to 67.4%, respectively. Regarding low similarity, the control effect of vaccines on variant strains is limited. Hence, variant strains may infect most local chickens and gradually become the dominant strain, threatening the development of the local poultry industry, or they may recombine with domestic epidemic strains to produce novel recombinant strains (Feng et al., 2018).

Recombination analysis showed that no recombination event occurred in CK/CH/HeN/20181207. CK/CH/HeN/20181207 is possibly a recombinant strain, but RDP analysis showed that its maternal strain was unknown. Probably owing to the limited number of reference strains, the strains with recombination events were not included. CK/CH/HeN/20160316 was derived from the recombination of 2 strain types isolated from China and Italy. Recombination of QX- and LDT3-type strains in CK/CH/HeN/20160113 may be a unique discontinuous RNA transcription system in IBV and a result of viral polymerase template jumps (Feng et al., 2017). Because CK/CH/HeN/20160113 may recombine with LDT3-type strain (one of the most widely used live vaccine strains), we predicted the tertiary structures of LDT3-type and CK/CH/HeN/20160113 strains. Mutations at some sites altered some parts of the protein structure. Whether these changes have an impact on IBV infectivity and whether IBV can cope with the protective effect of vaccines require further study. Recombination of different genotypes may contribute to the emergence of new IBV variant strains, thereby reducing the vaccine's protective effect on chickens infected with the variant strains.

In conclusion, our results indicate that the IBV variant strains found in central China have undergone a remarkable change in terms of genetic diversity and locally determined dominant genotypes. Therefore, real-time monitoring of IBV is still necessary and conducive to understanding the changes in regional epidemic strains and selecting appropriate vaccines for timely prevention and control.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 31802185 and 31870917), Scientific and Technological Project of Henan Province (grant no. 182107000040), Henan University Student Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program of Henan Province (S201910481018), Program for Innovative Research Team of Science and Technology in Henan Province (grant no. 20IRTSTHN024), Key Scientific and Technological Project of Nanyang City (grant nos. KJGG2018144 and KJGG2018069), and Technological Project of Nanyang Normal University (grant nos. 18046, 2019QN009, and 2019CX001). Ethical statement is not applicable as samples were collected from chickens. Procedures of virus isolation from embryonated specific pathogen-free chicken eggs were approved by the South China Agricultural University Committee for Animal Experiments (approval ID: SYXK-2014-0136, 25 March 2014) conducted in accordance with the recommendations of the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health.

Conflict of Interest Statement: The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Contributor Information

Jun Ji, Email: jijun020@126.com.

Xin Xu, Email: jzbetty@163.com.

References

- Alexander N., Woetzeland N., Meiler J. bcl:Cluster: a method for clustering biological molecules coupled with visualization in the Pymol molecular Graphics system. IEEE International Conference on Computational Advances in Bio and Medical Sciences: [proceedings] IEEE Int. Conf. Comput. Adv. Bio Med. Sci. 2011:13–18. doi: 10.1109/ICCABS.2011.5729867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali A., Kilany W.H., Zain E.M.A., Sayedand M.E., Elkady M. Safety and efficacy of attenuated classic and variant 2 infectious bronchitis virus candidate vaccines. Poult. Sci. 2018;97:4238–4244. doi: 10.3382/ps/pey312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bande F., Arshad S.S., Bejo M.H., Moeiniand H., Omar A.R. Progress and challenges toward the development of vaccines against avian infectious bronchitis. J. Immunol. Res. 2015:424860. doi: 10.1155/2015/424860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bochkov Y.A., Batchenko G.V., Shcherbakova L.O., Borisovand A.V., Drygin V.V. Molecular epizootiology of avian infectious bronchitis in Russia. Avian Pathol. 2006;35:379–393. doi: 10.1080/03079450600921008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casais R., Dove B., Cavanagh D., Britton P. Recombinant avian infectious bronchitis virus expressing a heterologous spike gene demonstrates that the spike protein is a determinant of cell tropism. J. Virol. 2003;77:9084–9089. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.16.9084-9089.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh D. Coronavirus avian infectious bronchitis virus. Vet. Res. 2007;38:281–297. doi: 10.1051/vetres:2006055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh D. Coronavirus IBV: structural characterization of the spike protein. J. Gen. Virol. 1983;64:2577–2583. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-64-12-2577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh D., Davis P.J., Darbyshireand J.H., Peters R.W. Coronavirus IBV: virus retaining spike glycopolypeptide S2 but not S1 is unable to induce virus-neutralizing or haemagglutination-inhibiting antibody, or induce chicken tracheal protection. J. Gen. Virol. 1986;67:1435–1442. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-67-7-1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwars R.M., Matthijs M.G., Daemen A.J., van Eck J.H., Verveldeand L., Landman W.J. Progression of lesions in the respiratory tract of broilers after single infection with Escherichia coli compared to superinfection with E. coli after infection with infectious bronchitis virus. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2009;127:65–76. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2008.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng K., Wang F., Xue Y., Zhou Q., Chen F., Biand Y., Xie Q. Epidemiology and characterization of avian infectious bronchitis virus strains circulating in southern China during the period from 2013-2015. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:6576. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-06987-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng K., Xue Y., Wang F., Chen F., Shuand D., Xie Q. Analysis of S1 gene of avian infectious bronchitis virus isolated in southern China during 2011-2012. Virus Genes. 2014;49:292–303. doi: 10.1007/s11262-014-1097-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng K.Y., Chen T., Zhang X., Shao G.M., Cao Y., Chen D.K., Lin W.C., Chenand F., Xie Q.M. Molecular characteristic and pathogenicity analysis of a virulent recombinant avain infectious bronchitis virus isolated in China. Poult. Sci. 2018;97:3519–3531. doi: 10.3382/ps/pey237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelb J., Weisman Y., Ladmanand B.S., Meir R. S1 gene characteristics and efficacy of vaccination against infectious bronchitis virus field isolates from the United States and Israel (1996 to 2000) Avian Pathol. 2005;34:194–203. doi: 10.1080/03079450500096539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgiades G., Iordanidisand P., Koumbati M. Cases of swollen head syndrome in broiler chickens in Greece. Avian Dis. 2001;45:745–750. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han Z., Sun C., Yan B., Zhang X., Wang Y., Li C., Zhang Q., Ma Y., Shao Y., Liu Q., Kongand X., Liu S. A 15-year analysis of molecular epidemiology of avian infectious bronchitis coronavirus in China. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2011;11:190–200. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2010.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai M.M., Cavanagh D. The molecular biology of coronaviruses. Adv. Virus Res. 1997;48:1–100. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(08)60286-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin D.P., Murrell B., Golden M., Khoosaland A., Muhire B. RDP4: detection and analysis of recombination patterns in virus genomes. Virus Evol. 2015;1:vev003. doi: 10.1093/ve/vev003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapats S.I., Ashton F., Wrightand P.J., Ignjatovic J. Novel variation in the N protein of avian infectious bronchitis virus. Virology. 1996;226:412–417. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigrist B., Tobler K., Schybli M., Konrad L., Stöckli R., Cattoli G., Lüschow D., Hafez H.M., Britton P., Hoopand R.K., Vögtlin A. Detection of Avian coronavirus infectious bronchitis virus type QX infection in Switzerland. J. Vet. Diagn. Invest. 2012;24:1180–1183. doi: 10.1177/1040638712463692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smati R., Silim A., Guertin C., Henrichon M., Marandi M., Arellaand M., Merzouki A. Molecular characterization of three new avian infectious bronchitis virus (IBV) strains isolated in Quebec. Virus Genes. 2002;25:85–93. doi: 10.1023/A:1020178326531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song C.S., Kim J.H., Lee Y.J., Kim S.J., Izumiya Y., Tohya Y., Jangand H.K., Mikami T. Detection and classification of infectious bronchitis viruses isolated in Korea by dot-immunoblotting assay using monoclonal antibodies. Avian Dis. 1998;42:92–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern D.F., Sefton B.M. Coronavirus proteins: structure and function of the oligosaccharides of the avian infectious bronchitis virus glycoproteins. J. Virol. 1982;44:804–812. doi: 10.1128/jvi.44.3.804-812.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K., Stecher G., Peterson D., Filipski A., Kumar S. MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013;30:2725–2729. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valastro V., Monne I., Fasolato M., Cecchettin K., Parker D., Terreginoand C., Cattoli G. QX-type infectious bronchitis virus in commercial flocks in the UK. Vet. Rec. 2010;167:865–866. doi: 10.1136/vr.c6001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandekerchove D., Herdt P.D., Laevens H., Butaye P., Meulemansand G., Pasmans F. Significance of interactions between Escherichia coli and respiratory pathogens in layer hen flocks suffering from colibacillosis-associated mortality. Avian Pathol. 2004;33:298–302. doi: 10.1080/030794504200020399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L., Han Z., Jiang L., Sun J., Zhaoand Y., Liu S. Genetic diversity of avian infectious bronchitis virus in China in recent years. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2018;66:82–94. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2018.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan S., Sun Y., Huang X., Jia W., Xieand D., Zhang G. Molecular characteristics and pathogenicity analysis of QX-like avian infectious bronchitis virus isolated in China in 2017 and. Poult. Sci. 2019;98:5336–5341. doi: 10.3382/ps/pez351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X., T. Deng, J. Lu, P. Zhao, L. Chen, M. Qian, Y. Guo, H. Qiao, Y. Xu, Y. Wang, X. Li, G. Zhang, Z. Wang and C. Bian. 2020. Molecular characterization of variant infectious bronchitis virus in China, 2019: implications for control programmes [e-pub ahead of print]. Transbound Emerg. Dis. doi: 10.1111/tbed.13477, accessed April 14, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]