I spent my youth and a great deal of my nursing practice in a remote region on Québec’s Lower North Shore. As a nurse responsible for populations of 600 residents or less I have endured my fair share of precarious experiences. Outpost clinics are significantly different than mainstream health centres. There are no labs, x-rays, ultrasounds and, at times, no doctor. Nurses are the community’s life support. When emergencies arise they rarely occur within the clinic. Transporting patients to hospital can be extremely challenging. However, there is a strong sense of community through each village in this region. Community members can be your biggest asset in recovering injured or sick patients. They are your right hand and sometimes your only extra hands. From transporting patients by snowmobile and komatik in the winter to a stretcher in the back of my own van in the summer, I have learned how to develop a makeshift style of nursing.

In 2009, I decided to move to Ottawa and took a position in the emergency department at Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario (CHEO). I stayed less than a year before eagerly wanting to return to rural nursing. For the next seven years I decided to take contracts in northern regions. Then, in 2016, I was offered the role of an Indigenous Nurse Navigator at The Ottawa Hospital. This position was created by Alethea Kewayosh, Director of the Indigenous Cancer Care Unit of Ontario Health (Cancer Care Ontario). There is an Indigenous Navigator of varying professional backgrounds in every (formerly) Local Health Integration Network in Ontario.

This new role allowed me to once again incorporate my unconventional approach to nursing. My personal and professional experiences in rural and northern regions have provided me with the knowledge and skills to develop a trusting relationship with patients and their family while I support them through one of the most difficult times of their life.

YESTERDAY AND TODAY

Trust in the healthcare system has not come easily to Indigenous and Inuit peoples. Why should it? The First Nations Inuit and Métis have been and continue to be discriminated against since the founding of Canada. The assimilation of this group of individuals had even been promoted with the election of the first Prime Minister, John A. MacDonald. He expressed his views on the indigenous culture as he stated, “It has been strongly pressed on myself, as the head of the Department, that Indian children should be withdrawn as much as possible from the parental influence, and the only way to do that would be to put them in central training industrial schools where they will acquire the habits and modes of thought of white men”.

The last residential school to be closed was 24 years ago in 1996. Many consider this a long time ago but, working in Indigenous communities, I can confirm this mentality continues to linger.

My most recent encounter with this discriminatory attitude involved a hospital volunteer in Spring 2019. She presented to my office and proceeded to tell me that in her early days as a nurse, she worked on a reserve in Alberta. In her opinion, the Indigenous people living on the reserve “had no natural maternal instincts” and they needed to be “taught how to be civilized human beings.” She also referred to the residential schools as being beneficial, as they educated “them people.” After clearly stating her perspective, she then defended herself by claiming she was not a racist. More often than not, those who convey degrading remarks often follow with a defensive statement, as if by claiming not to be racist permits them to utter racial slurs freely. Part of my role as a nurse navigator is to be aware of these prejudiced behaviours, do my best to educate and raise awareness, and offer my clients a positive and safe environment during their treatment in Ottawa.

THE NURSE NAVIGATOR ROLE

What is an Indigenous patient nurse navigator? It is diverse, land-based and entirely patient centred. My role is non-clinical and does not replace any service within the hospital. Nor is it case management. It involves a triage of needs based on what the patient and family determine their needs are. I meet them with no prior agenda, as there is no single care plan suitable for every patient. I introduce myself by asking if they have any questions, not just about their cancer but anything at all. My principal objective is to establish trust and to be that important link between them and the cancer care team. Given the historical context, I understand this will come gradually. To help build this trust, it’s necessary to give Indigenous communities their own voice. Often, they are overshadowed by others speaking on their behalf. Their individual voices need to be heard and I make it a priority to be their advocate.

The nursing clinical knowledge I have obtained through outpost and emergency room settings assists me with patient care, but also with acceptance amongst hospital and community partner staff. Relationship building is key not only with FNIM patients, but also those treating them. Having 20 years of unique outpost experience in Indigenous and Inuit communities establishes a credibility to my professional role and, therefore, helps me serve as a more creditable advocate.

SUPPORTIVE CARE FRAMEWORK

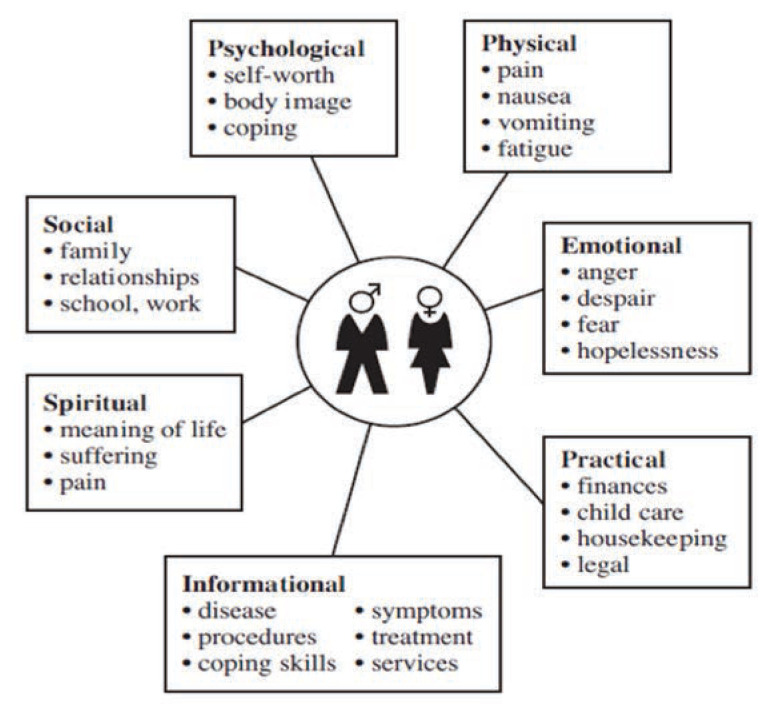

Since I first became involved with this program, we have been using an unconventional approach that directly focuses on the patients’ personal needs. This style of nursing can be exemplified by Margaret Fitch’s Supportive Care Framework for Cancer Care. A wholistic perspective to the care of cancer patients is based on a variety of needs, not just the physical aspect (Fitch, 2008). “The Supportive Care Framework for Cancer Care draws upon the constructs of human needs, cognitive appraisal, coping and adaptation as a basis for conceptualizing how human beings experience and deal with the cancer” (Fitch, 2008). In order to meet the non-physical needs of each individual, it is necessary to have a respectful understanding of who they are as a person and what is important to them.

Examples of needs of indiviauls living with cancer

First Nations, Métis and Inuit communities may differ in culture, land mass and lifestyle, but what unites them is their shared connection to the land. Both presently and historically, they use resources provided by nature to prosper, grow, heal, and find comfort. Keeping the Supportive Care Framework in mind, I developed an approach that meets their non-clinical needs while at the same time complementing the care being received from the cancer care staff. What better way to strengthen this connection than outside of the hospital setting, in nature where these patients are most comfortable?

Debra

MY FIRST PATIENT

My first patient in my role as the cancer program’s Indigenous Nurse Navigator was a young woman named Debra from the eastern sector of Nunavut. While on a school trip to Quebec City, Debra began experiencing severe migraines. She was taken to the emergency and was later diagnosed with stage 4 glioblastoma. Eighteen months prior to this diagnosis, she had lost two sisters to cancer, both under the age of 24. I first met Debra and her family outside of the CHEO genetic testing centre. I make it a point not to insert myself into the medical aspect of their treatment, especially on the first encounter, as this is not my primary role. My primary role is to establish trust and then to be that link for the patient with the hospital and all the supporting partners in between. The staff at The Ottawa Hospital do such a wonderful job at informing patients about their cancer process, treatments, and side effects that I get few questions concerning their actual disease.

As Debra and her parents emerged from the appointment, I could see an overwhelmed look on each of their faces. At this point, it had become obvious it was not a time to take them into yet another hospital room or another office to have that first conversation, and they certainly did not want to discuss cancer anymore. Instead, I asked if they would appreciate a drive around Ottawa to escape and have a break from the medical environment.

Coming from a small village, I know the strong impact hockey has in uniting people in Canada. Without any prior appointment, I decided to take Debra and her family to the Canadian Tire Centre, home rink of the Ottawa Senators. Even though it was June and there were no games taking place, I thought even seeing the building might be something they would appreciate. Once security had allowed us entry and we began the tour, I felt a palpable shift in the emotions of Debra and her family. I realized the positive outcomes that take place when patients are given a reprieve from the traditional healthcare environment. Incorporating community activities to help alleviate the overwhelming and all-consuming stress of the cancer care experience is a key factor in establishing the trusting relationship essential to my role.

This experience with Debra and her family was the inspiration for my role as Indigenous Nurse Navigator. First Nations, Inuit and Métis peoples, while diverse in so many ways, have one thing in common—they are people from the land. Incorporating land-based experiences out of the hospital environment has a significant impact on the mental health of the patient and fosters a first step in building a trustful and meaningful relationship with the Nurse Navigator. Like Debra, patients from Nunavut may experience a sense of being lost in an urban setting and in such a geographically different landscape. There are no trees in Nunavut. No horses. No cows, or wild turkeys. With almost every patient I take them on a land-based activity. It may be sitting by the Ottawa River watching the geese. It may be in the Gatineau Park walking in the leaves, peeling the bark off a tree. Tranquil settings really assist in breaking down barriers.

These experiences allow me to support mental health and psychosocial aspects of their care. Once a year, our program takes a group of Inuit cancer patients and their families on a horse drawn wagon ride with a visit to a small farm. For many, it is their first time seeing these animals. Being up close to a horse has been a bucket list dream for some participants. To be able to assist in creating wonderful memories for patients while they are receiving cancer care is immeasurable.

COMMUNITY

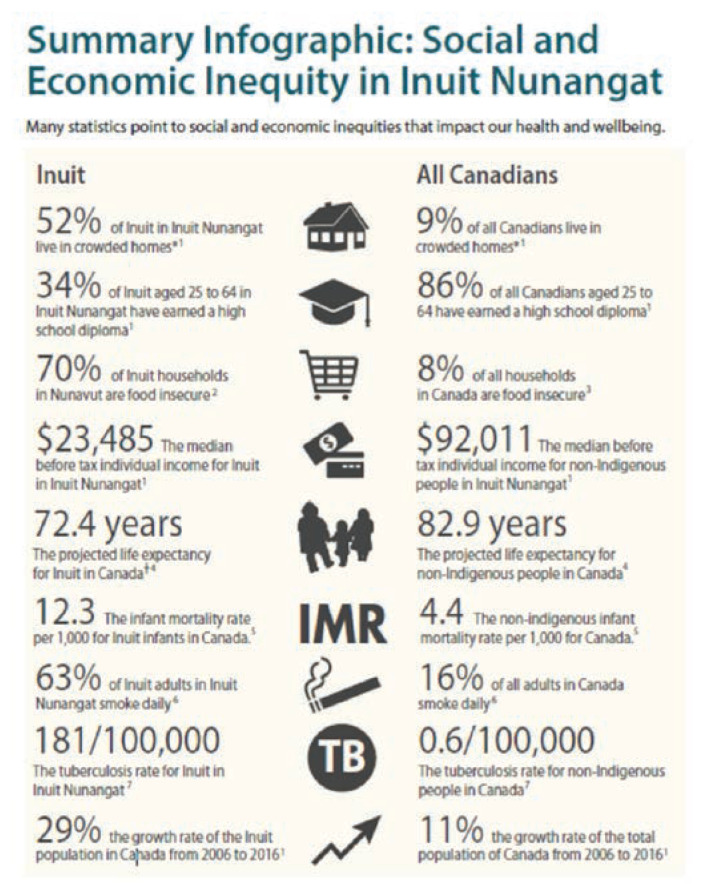

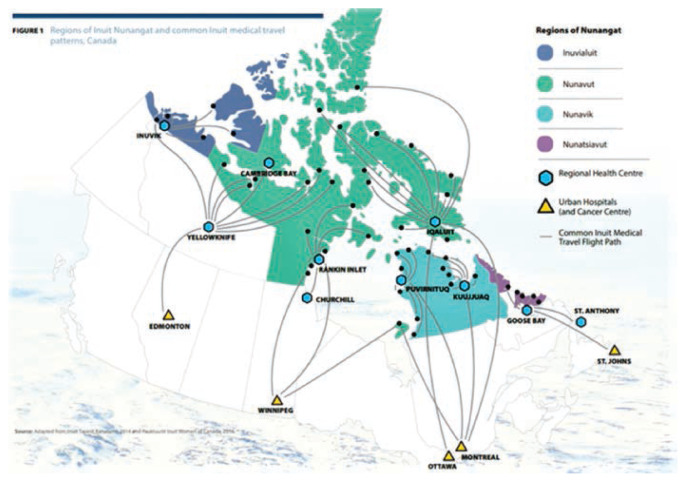

Too often, for a variety of reasons, our team meets Indigenous patients who have a late stage cancer diagnosis. With all patients, I provide support and help for their emotional well-being through the cancer care experience, including for the many who, unfortunately, require palliative care. A unique level of support is required for our patients from Nunavut who need to be in Ottawa for tests and treatments. Diagnosing and treating their disease requires them to be away from their family, friends, culture, and community for months at a time. They experience a level of isolation, boredom and loneliness that we can only imagine.

Travel routes for residents of Inuit Nunangat accessing medical care

My goal is to support patients in looking past their diagnosis and giving them as many positive experiences as I can. Being in an urban setting, we take the various activities Ottawa has to offer for granted. For some of our patients there may be a variety of obstacles in getting to experience them. When I was practising in northern regions, I relied heavily on community resources. When patients come to Ottawa for treatment they are displaced from family, community and culture. In my opinion, we should be able to assist with urban navigation, as well as oncology navigation.

As a result of this navigation program, wonderful experiences and opportunities have come their way. Our team has been repeatedly moved by the outpouring support from the Ottawa community. Community members, like William (Bill) Ellam, Head of Security and Guest Services at the Canadian Tire Centre, have been wonderful. Bill, an unofficial member of our team, has supplied patients and their families with countless VIP experiences at Senators hockey games. He said, “Hockey really breaks down barriers.” Our team was also recognized by the Ottawa Redblacks Football organization and given a Redblacks community hero’s award for the work we are doing to support Frist Nations Inuit and Métis patients, families, and communities.

The Ottawa Hospital Indigenous Cancer Program From left to right: Treena Greene, MD, CCFP, FCFP, Regional Indigenous Cancer Lead; Carolyn Roberts, First Nations, Inuit and Métis Patient Nurse Navigator; Gwen Barton, Manager, Indigenous Cancer Program; Meg Ellis, Indigenous Cancer Program Coordinator

A snapshot of a few of the many supporters who influenced my nursing career.

CONCLUSION

I recognize that the navigator approach described in this article is not practical or possible for many clinical departments or healthcare settings. However, to provide patient-centred, culturally safe care, we must look for opportunities beyond traditional western medicine and consider some ‘out-of-the box’ approaches whenever possible. As clearly stated in the Truth and Reconciliation Calls to Action (Truth, & Reconciliation Commission of Canada), we need to acknowledge and address the challenges in accessing health services for many of our Indigenous patients and take action to provide opportunities for positive mental health while receiving care.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to end by saying that without the constant support from my manager and the leadership team at The Ottawa Hospital Cancer Program, I never would have been able to use this untraditional type of patient care and supported the patients in this meaningful way. I also have tremendous gratitude toward my previous outpost colleagues who helped shape me into the nurse I am today. Most importantly, I want to thank my family. As with most nurses, we miss many holidays and special events. When I took northern contracts, I was separated from my husband John and four children for up to eight weeks at a time. Without their consistent and unwavering love and support, it would not have led me to where I am today.

I am extremely grateful to have been the recipient of the Helen Hudson Award, which has given me the opportunity to share my experiences with so many nurses from across Canada. I encourage all nurses, who I feel are the backbone of healthcare, to look for ways to support each other. If a colleague, junior staff, or any member of your team comes to you with an untraditional approach, ask yourself: “Is it safe? Is it feasible? Most importantly, will it benefit the patient?”

Qujannamiik.

Footnotes

Editor’s Note: This article was prepared based on the Helene Hudson Lectureship given at the Annual CANO/ACIO Conference in 2019. The lectureship was established in memory of Helene Hudson from Manitoba who provided inspiring leadership for oncology nursing and patient care.

REFERENCES

- Fitch M. Supportive care framework. Canadian Oncology Nursing Journal /Revue Canadienne De Soins Infirmiers En Oncologie. 2008;18(1):6–14. doi: 10.5737/1181912x181614. Retrieved from http://canadianoncologynursingjournal.com/index.php/conj/article/view/248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami. Inuit Statistical Profile 2018. 2018. Retrieved from https://www.itk.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Inuit-Statistical-Profile.pdf.

- Truth & Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Canada’s Residential Schools-Missing Children and Unmarked Burials: The Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Vol. 4. McGill-Queen’s Press-MQUP; 2015. [Google Scholar]