Abstract

Alternative flooring designs in broiler housing have been the subject of intensive research. Research comparing different floor types with a focus on animal-based welfare indicators might be of special interest to meet the animal's needs. This case–control study investigated the effect of a partially perforated vs. a littered flooring system on health- and behavior-based welfare indicators of fast-growing Ross 308 broilers. Furthermore, production performance was assessed. The experimental barn was partially (50%) equipped with a perforated floor directly underneath the feeders and water lines accessible by perforated ramps. Conventional wood shavings were used in the control barn, as usual in practice. There were 4 fattening periods (repetitions) of 31 to 32 D performed with 500 animals per barn (final density of 39 kg m−2). Beside the flooring system, management conditions were identical. Health- and behavior-based welfare indicators were assessed weekly. Production performance indicators were measured continuously during animal control. During the avoidance distance test, animals were less fearful on day 21 (P = 0.010) and tended to be less fearful on day 28 (P = 0.083) in the barn with the partially perforated flooring system compared to the littered control barn. More animals around the novel object were also assessed in the barn with the partially perforated flooring system during the novel object test on day 1 (P < 0.001) and a tendency was found on day 28 (P = 0.064). Results showed that the partially perforated flooring system had a positive influence on foot pad dermatitis from day 14 (all P ≤ 0.007) and hock burn on day 28 (P < 0.001). With regard to the production performance, animals showed no differences in final body weight for both floor types. In this study, the partially perforated flooring system had a positive effect on animal health and behavior as indicated by welfare indicators without a reduction in production performance.

Key words: broiler production, alternative flooring, animal welfare, animal health, animal behavior

Introduction

In Germany, broilers are conventionally housed in deep-litter systems with organic bedding materials. From an economic point of view, the costs of bedding materials and labor are important factors. New bedding and laborious manure removal during the fattening period is unusual in practice. Because animal welfare is gaining public interest, housing systems should not only be economical but also adapted to animal's needs. The Welfare Quality Assessment protocol for poultry of Welfare Quality (2009) serves to quantify animal welfare in broilers and laying hens. Management, physiological, and health, as well as behavioral, indicators are used to assess the suitability of a husbandry environment for the animals. Based on 4 main principles (good feeding, good housing, good health, and appropriate behavior), management- and animal-based information can be collected on farm (Welfare Quality, 2009).

In conventional deep-litter systems, broilers are usually kept in an unstructured housing environment, spending the whole fattening period in direct contact with litter (Bergmann et al., 2017). According to Shepherd and Fairchild (2010), litter is referred to as a mixture of bedding material, excrements, feathers, wasted feed, and moisture. One of the main functions of litter is to absorb moisture, to store it, and to release it after evaporation via the ventilation system (Dunlop et al., 2016). Nevertheless, Elwinger and Svensson, 1996 reported a reduction in litter's dry matter from 92 to 64% between day 0 and day 35 of the fattening period. Litter is defined as wet if the rate of water addition exceeds the rate of removal and the dry matter content is less than 75% (Collett, 2012). From day 14, about 80% of litter's dry matter consists of excrements and feed residues (Kamphues et al., 2011). Therefore, the animals spend at least half of the fattening period in contact with litter with a high percentage of moisture and excrements. Permanent contact with litter with these properties can lead to foot pad dermatitis, hock burn, plumage contamination, and a reduction in production performance (De Jong et al., 2014). These circumstances can cause discomfort, pain, injury, or diseases and will, therefore, be classified as reducing animal welfare.

Studies on housing broilers on perforated floors have shown that separating broilers from the litter can be useful to increase animal welfare. It could be identified that perforated floors can reduce the occurrence of foot pad dermatitis (Cengiz et al., 2013), as well as hock burn and plumage contamination (Almeida et al., 2017) compared to deep-litter systems. Chuppava et al. (2018) even showed economic advantages for the use of perforated floors due to an increase in production performance.

The main disadvantage of a totally perforated flooring system is the missing bedding material for exercising natural behavior (Blokhuis, 1989). Bedding materials have a major effect on the behavior and the physiology of the animals (Nowaczewski et al., 2011, Cabrera et al., 2018). Several studies showed that many of the broiler's natural behaviors like pecking, scratching, and dust bathing are exhibited in contact to bedding material (Shields et al., 2005, Villagrá et al., 2014, Baxter et al., 2018). In addition, it was reported that an enrichment of the housing environment through elevated surfaces, ramps, and other structural elements increases the complexity of the housing system and thus animal welfare (Ventura et al., 2012, Bergmann et al., 2017, Tahamtani et al., 2018, Tahamtani et al., 2019, Bach et al., 2019, De Jong and Gunnink, 2019). For example, Baxter et al. (2019) reported an increase in animal welfare when broilers were kept with access to perforated platform perches.

The idea of the study was to combine the positive effects of perforated and littered areas in broiler housing and, therefore, to increase animal welfare. An elevated perforated floor in the area of feed and water supply could reduce the animals' contact to litter with a high percentage of moisture and excrements and thus improve animals' health. Owing to the elevated position, the perforated area could contribute to an increase in environmental enrichment and an enhanced environmental complexity in broiler houses. At the same time, littered areas could provide access to bedding material to exhibit natural behavior such as scratching, pecking, and dust bathing. The aim of the study was therefore to compare animal-based welfare indicators for broilers kept on a partially (50%) perforated flooring system with conventional deep-litter housing.

Materials and methods

Animals and Housing

This case–control study was carried out at the Educational and Research Center Frankenforst of the Faculty of Agriculture, University of Bonn (Königswinter, Germany; 55° 42′ 55N and 7° 12′ 26E). The experiments were performed in accordance with German regulations and approved by the relevant authority (Landesamt für Natur-, Umwelt- und Verbraucherschutz Nordrhein-Westfalen, Recklinghausen; 81.02.04.2018.A057). A total of 4 fattening periods of 31 to 32 D were carried out in 4 different seasons, from August 2018 to June 2019. To fulfil the conditions of a case–control study (experimental vs. control barn), 2 identical barns were used. Each barn measured 5.3 × 4.7 × 2.3 m (17.4 × 15.4 × 7.5 feet; ca. 25 m2 and ca. 57 m³), with a housing capacity of 500 fast-growing Ross 308 broilers and a final density of 39 kg m−2. Both barns were ventilated by negative pressure ventilation, whereby the ventilation rate and the barn temperature were adapted to the management guide given for Ross 308 (Aviagen, 2018). Automatically controlled climate computers (PL-9400, Stienen Bedrijfselektronica B.V., RT Nederweert, Netherlands) were used to ensure identical conditions for both barns. As usual in practice, the management followed an “all in/all out” production cycle. The animals were hatched in the hatchery (BWE-Brüterei Weser-Ems GmbH & Co. KG, Rechterfeld, Germany) and placed on feed and water immediately after transport. After the fattening period, the broilers were slaughtered. The service period between the fattening periods was used to clean and provide both barns with new wood shavings (except the area of the perforated floor). Standard broiler feed (Deuka, Deutsche Tiernahrung Cremer GmbH & Co. KG, Düsseldorf, Germany) and water were offered to the animals for ad libitum consumption. Table 1 shows the ingredients and nutrient composition of the commercial broiler diets. According to the German Order on the Protection of Animals and the Keeping of Production Animals (2006), both barns were equipped with 4 round feeders (1.07 cm per animal) and 2 water lines (9 animals per nipple). Furthermore, both barns were equipped with windows (light entrance area: 3% of floor space). The additional lighting program is shown in Table 2. A dawn to dusk program with 1 hour each was used to create transitions between the light and dark periods. As an enrichment tool, a limited number of Miscanthus briquettes (Campus Klein-Altendorf, Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-University Bonn, Rheinbach, Germany) were added on day 14, 21, and 28 in both barns. Animals were vaccinated against Newcastle disease (day 13), Gumboro disease (day 18), and infectious bronchitis (day 18).

Table 1.

Ingredients and nutrient composition of commercial broiler diets.

| Starter | Grower | Finisher | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolic energy (MJ/kg) | 12.40 | 12.40 | 12.40 |

| Crude protein (%) | 21.50 | 21.00 | 20.00 |

| Crude fat (%) | 5.20 | 6.10 | 5.50 |

| Crude fiber (%) | 3.10 | 3.30 | 3.30 |

| Crude ash (%) | 5.40 | 5.00 | 4.90 |

| Calcium (%) | 0.90 | 0.80 | 0.80 |

| Phosphorus (%) | 0.60 | 0.55 | 0.50 |

| Sodium (%) | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.14 |

| Lysine (%) | 1.25 | 1.15 | 1.05 |

| Methionine (%) | 0.55 | 0.50 | 0.50 |

Table 2.

Lighting program during the fattening periods.

| Day of life [d] | Light [h] | Dark [h] |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 24 | 0 |

| 1 | 22 | 2 |

| 2 | 20 | 4 |

| 3 to 29 | 18 | 6 |

| 30 | 20 | 4 |

| 31 | 22 | 2 |

| 32 | 24 | 0 |

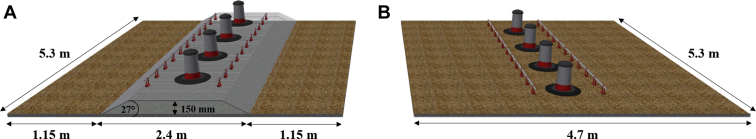

Floor Design

The floor of the experimental barn was partially (50%) equipped with an elevated perforated floor (Figure 1). Polypropylene-based perforated elements (Golden Broiler Floor, FIT Farm Innovation Team GmbH, Steinfurt, Germany) were modified as the basis of the construction. These perforated elements seemed to be useful because they were walkable and easy to adapt to the experimental setup. The construction of the perforated floor had a size of 5.3 × 2.4 m (17.4 × 7.9 feet) and was located underneath the feeders and water lines in the middle of the barn (Figure 2). Exactly underneath the feeders and water lines, there was a horizontal area with perforated elements. Each perforated element measured 1,198 × 560 × 40 mm (lengths x width x height), and the openings were 15 × 15 mm (lengths x width) in size. To ensure storage capacity of the excrements, the horizontal area had a ground clearance of 150 mm. A construction of polyethylene posts (PE-HD pipe 2″) and flat steel beams (type V2A; 5.3 × 5 × 50 mm) were used for stabilization. The horizontal area was accessible by the animals via perforated ramps with an angle of 27°, constructed by the same floor type. The remaining concrete floor area of 12.2 m2 was equipped with conventional wood shavings (600 g m−2). The control barn was completely equipped with conventional wood shavings (600 g m−2) and served as control group (Figure 2). Except for the construction of the perforated floor in the experimental barn, both barns were set up and operated identically (case–control study). The experimental and control barn were changed once after the fall fattening period to avoid an effect of the barn buildings themselves on the results.

Figure 1.

Illustration of a partially perforated flooring system in the area of feed and water supply in the experimental barn (A) compared to a littered flooring system in the control barn (B).

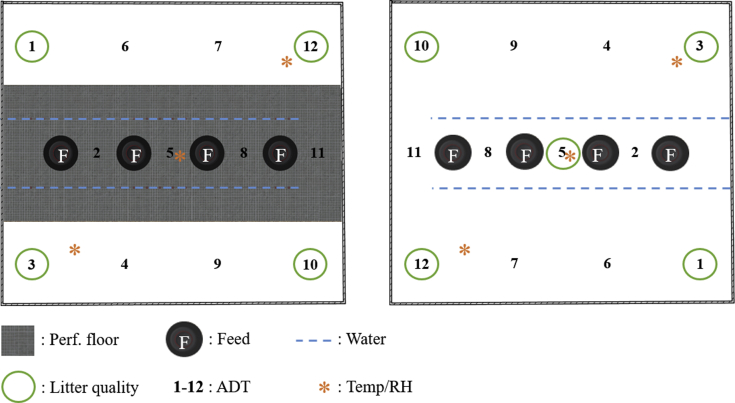

Figure 2.

Layout of 2 broiler housing systems; a partially perforated floor underneath the feeders and water lines with access to a littered area in the experimental barn (A) and a total littered floor in the control barn (B).

Behavior-Based Welfare Indicators

With regard to the behavioral welfare indicators, the avoidance distance test (ADT) and the novel object test (NOT) were carried out as described by Welfare Quality (2009). Observations were always carried out by the same person on day 1, 7, 14, 21, and 28.

The assessment of the animal-based welfare indicators on the different assessment days always started with the ADT. The ADT introduced in its procedure by Welfare Quality (2009) is considered a validated method to investigate the human–animal relationship. The reaction of animals to an observer can be classified as an indicator of general fearfulness and, therefore, of animal welfare. On assessment day 1, the ADT started 2 h after morning feeding in the control barn. With regard to the following assessment day, the order changed and the observer started in the experimental barn. The weekly order changes were applied to avoid an effect of starting time. After entering the barn, the observer waited 5 min for the animals to calm down. According to Welfare Quality (2009), the test consists of 21 trials all over the barn. Due to the size of the barns (ca. 25 m2), only 12 trials were carried out to avoid repeated scoring of the same animals. Regardless of the assessment day and the floor type, the trials were always carried out at the same positions and in the same order (Figure 3). In each trial, the observer went to a position, squatted for 10 s, and counted the number of animals in arm's reach (1 m). Every attempt to approach a group of animals was considered a trial. If no animals were around the observer after 10 s, the numerical value was still recorded as “0” and the next trial was started.

Figure 3.

Layout of 2 broiler housing systems with 2 different floor types including measurement positions for the litter quality, avoidance distance test (ADT), air temperature (Temp), and relative air humidity (RH).

After the ADT, the NOT was carried out. The NOT is a validated method by Welfare Quality (2009) to determine general fearfulness and neophobia as an indicator for animal welfare in poultry. The principle is to confront the animals with an unknown object and to assess the following reaction. First, the observer selected 4 different positions, where the most animals have stayed (including the perforated floor, if animals were present). On every assessment day, care was taken to ensure that the number of animals at the different positions was comparable for both barns. After that, the novel object was placed on the ground, and the observer moved 1.5 m backwards and counted the animals around the novel object every 10 s for a total time of 2 min. The radius for counting was one bird length, adjusted weekly to the increasing size of the animals. If no animals were around the novel object at any time of assessment, the numerical value was still recorded as “0.” This procedure was repeated at the 4 different positions. Every week, a different novel object was used. Because the color of the novel object has an impact on the behavior of the animals (Ham and Osorio, 2007), the objects had identical proportions of green, yellow, and red.

Litter Quality

Following the assessment of the behavior-based welfare indicators on day 1, 7, 14, 21, and 28, litter quality was recorded according to Welfare Quality (2009). Figure 3 shows the positions where the litter samples were taken. A total of 5 litter samples were taken in the littered control barn and 4 litter samples in the experimental barn (no litter in the perforated area). A scoring system from 0 to 4 was used to evaluate the litter quality (Welfare Quality, 2009). Score 0 was equal to “completely dry and flaky, that is, moves easily with the foot”; score 1 was equal to “dry but not easy to move with foot”; score 2 was equal to “leaves imprint of foot and will form a ball if compacted, but ball does not stay together well”; score 3 was equal to “sticks to boots and sticks readily in a ball if compacted”; and score 4 was equal to “sticks to boots once the cap or compacted crust is broken.”

Health-Based Welfare Indicators

After the litter quality assessment, health-based welfare indicators were assessed on day 1, 7, 14, 21, and 28 by Welfare Quality (2009). For the evaluation of the health indicators, 50 broilers per barn and test day were randomly selected. To ensure a representative sample, care was taken to catch the animals equally from all areas of the barn. After that, animals were examined with regard to foot pad dermatitis, hock burn, and plumage cleanliness. According to the scoring system of Welfare Quality (2009), a scoring range from 0 to 2 was used to evaluate foot pad dermatitis and hock burn. No evidence of foot pad dermatitis or hock burn was equal to score 0, minimal evidence of foot pad dermatitis or hock burn was equal to score 1, and evidence of foot pad dermatitis or hock burn was equal to score 2. For plumage cleanliness, a scoring from 0 to 3 was used. No soiling of the breast was equal to score 0, mild soiling of the breast was equal to score 1, increased soiling of the breast was equal to score 2, and severe soiling of the breast was equal to score 3. Observations were always carried out by the same person.

Production Performance

For the evaluation of the production performance, body weight, feed consumption, and mortality were recorded. To measure the initial body weight, 50 randomly selected animals per barn were weighed immediately after transport with a platform scale (Kern DE 6K1D, KERN & SOHN GmbH, Balingen, Germany). During the first fattening period (summer), no initial body weight was recorded. The 50 randomly selected animals per barn from the health assessment were weighed on day 1, 7, 14, 21, and 28. Another 20 randomly selected animals per barn were weighed on day 31 to 32 to record the final body weight. Feed consumption was determined as cumulated feed intake per week divided by the number of animals, expressed in kg. Feed consumption was adjusted for mortality, which was documented daily during animal control. The feed conversion ratio (FCR) was calculated as a quotient of the feed consumption and the total weight gain at the end of the fattening period. To compare the efficiency of different flocks, the European Production Efficiency Factor (EPEF) was calculated:

| (1) |

where EPEF = European Production Efficiency Factor, survival rate = percentage of animals that survived to the end of the fattening period (%), final body weight = average body weight at the end of the fattening period (kg bird−1), age = age of the broilers at the end of the fattening period (day), feed conversion ratio = feed consumption (kg bird−1)/total weight gain (kg bird−1).

Environmental Factors

To measure air temperature (Temp) and relative air humidity (RH), the experimental and control barn were evenly equipped with 3 data loggers (Tiniytag Plus 2–TGP-4,500 loggers, Gemini Data Loggers Ltd., Chichester, West Sussex, UK) at 55 cm height (Figure 3). On the basis of 3 measurements per minute and measurement point, the average Temp and RH were calculated from 480 values per barn and day.

Statistical Analysis

For statistical analysis, SPSS Statistics 25 was used (IBM Corporation, Armonk, USA). Graphical presentation was done with SigmaPlot 14.0 (Systat Software Inc., Chicago, USA).

Health- and behavior-based welfare indicators as well as litter quality data were analyzed by general linear models (GLM). Link function was Poisson distributed. Owing to the lack of variability of the recorded health-based welfare indicators as well as litter quality data on day 1, these data were excluded from the statistical analysis. In the first step, univariate GLM were used to select the significant main effects with ADT, NOT, litter quality, foot pad dermatitis, hock burn, and plumage cleanliness as response variables. Significant main effects were then analyzed by multifactorial GLM. After backward selection, the final GLM were presented with interaction terms (floor type x day) and can be found in Supplementary Tables 1–7. The P-values were corrected by Bonferroni. Differences P ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant; 0.05 < P < 0.10 were considered a tendency.

For production performance, differences between body weight, feed consumption, cumulated daily mortality, FCR, and EPEF were presented with 95% confidence interval (95% CI).

Temp and RH were tested for normal distribution using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Because data were not normal distributed, Spearman's rho correlation analysis was applied to compare the 2 different flooring systems regarding average daily Temp and RH over the fattening periods (n = 4).

Results

Behavior-Based Welfare Indicators

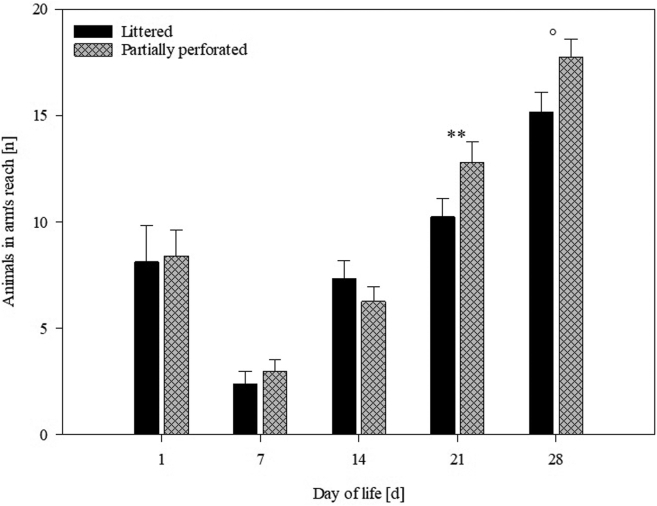

A comparison of the average weekly number of animals in arm's reach of the observer during the ADT showed differences between the partially perforated and the littered flooring system (Figure 4). On day 21, a significantly higher number of animals could be observed in arm's reach of the observer in the barn with the partially perforated flooring system compared to the littered control barn (P = 0.010). Furthermore, there was a tendency that more animals around the observer were found on day 28 when kept on the partially perforated flooring system (P = 0.083). For both floor types, the lowest number of animals in arm's reach of the observer could be found on day 7 and the highest number on day 28.

Figure 4.

Mean number of animals in arm's reach of the observer during the avoidance distance test (ADT) with standard error from broilers kept on 2 different floor types measured weekly over 4 different fattening periods (repetitions; n = 48 values per assessment day and barn). Significant differences are marked by asterisks: ∗∗P < 0.01. Tendencies are marked by circles: °0.05 < P < 0.10.

Independent of floor type, the highest number of animals around the observer could be found in the summer and the lowest in the fall fattening period (P < 0.001). In general, a higher number of animals could be found in the littered areas next to the feeders and water lines compared to the area of feed and water supply in the middle of the barn (P < 0.001). With each trial carried out during the different assessment days, the number of animals in arm's reach of the observer increased (P = 0.005).

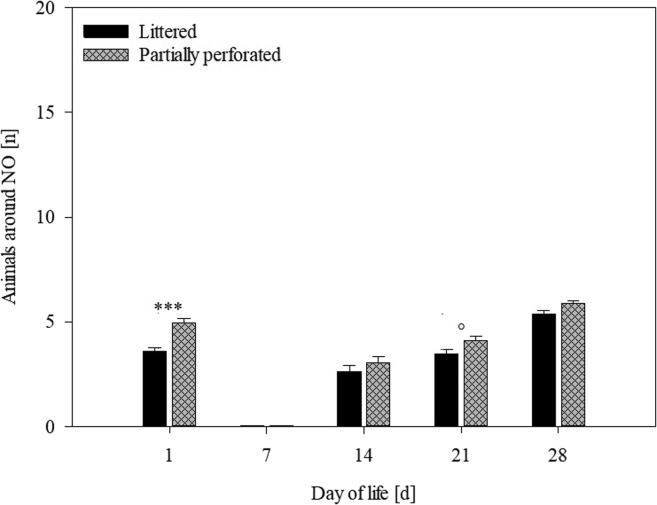

Figure 5 shows the average weekly number of animals around the novel object of the 4 fattening periods (repetitions). On day 1, more animals around the novel object were observed in the barn with the partially perforated flooring system compared to the littered control barn (P < 0.001). Results for day 21 showed a tendency that animals kept on the partially perforated flooring system were less fearful of the novel object compared to the littered control barn (P = 0.064). For both floor types, the lowest number of animals around the novel object could be observed on day 7 and the highest on day 28.

Figure 5.

Mean number of animals around the novel object (NO) during the novel object test (NOT) with standard error from broilers kept on 2 different floor types measured weekly over 4 different fattening periods (repetitions; n = 192 measurements per assessment day and barn). Significant differences are marked by asterisks: ∗∗∗P < 0.001. Tendencies are marked by circles: °0.05 < P < 0.10.

In summary, the highest number of animals around the novel object was found in the summer and the lowest in the fall fattening period (P < 0.001). Furthermore, the position (successive performance of the NOT at the 4 different positions) and the counting time (second of counting) influenced the animals' reaction of the novel object. It could be shown that the highest number of animals around the novel object was observed at position 1 and the lowest at position 2. Between position 2 and 4, the number of animals increased continuously (P < 0.001). Overall, general fearfulness of the novel object decreased with an increase in counting time within the 4 selected positions (P = 0.005).

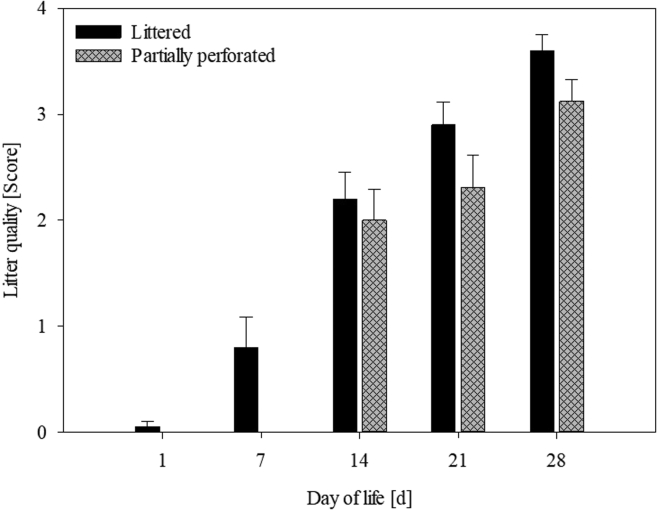

Litter Quality

A decrease in litter quality over the fattening period is shown in Figure 6. Floor type had no effect on average litter quality. Overall, a lower litter quality was observed in the area of feed and water supply of the control barn compared to the littered areas next to it (P < 0.001).

Figure 6.

Mean scores of litter quality with standard error from broilers kept on 2 different floor types measured weekly over 4 different fattening periods (repetitions; n = 16 to 20 litter samples per assessment day and barn).

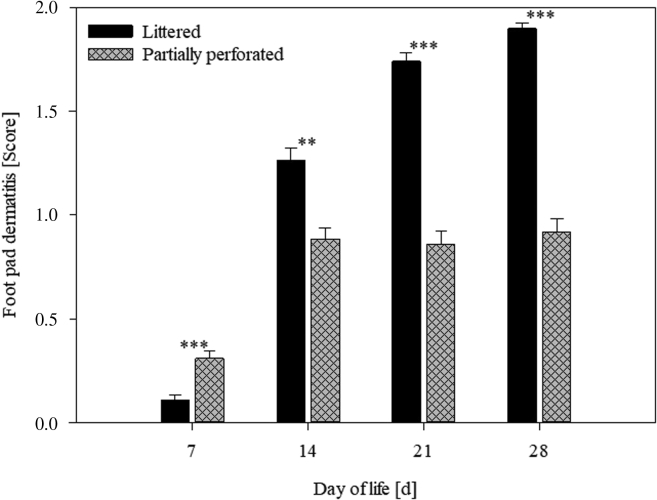

Health-Based Welfare Indicators

The average weekly foot pad dermatitis scores of the 4 fattening periods (repetitions) are shown in Figure 7. On day 7, animals of the littered control barn had significantly lower foot pad dermatitis scores than animals kept on the partially perforated flooring system (P < 0.001). By contrast, animals on day 14 had less foot pad dermatitis when kept on the partially perforated flooring system compared to the littered control barn, as well as on day 21 and on day 28 (P all < 0.007). There was a continuous decrease in foot pad health for animals kept in the littered control barn over the time. Animals kept on the partially perforated flooring system showed a nearly constant foot pad health from day 14. With regard to the 4 different fattening periods, animals had the highest foot pad health in the fall and the lowest in the summer fattening period (P < 0.001).

Figure 7.

Mean scores of foot pad dermatitis with standard error from broilers kept on 2 different floor types measured weekly over 4 different fattening periods (repetitions; n = 200 animals per assessment day and barn). Significant differences are marked by asterisks: ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001.

A comparison of the average weekly hock burn scores of the 4 fattening periods (repetitions) revealed a significant difference between both floor types toward the end of the fattening period (Figure 8). Results for day 28 showed less hock burns for animals kept on the partially perforated flooring system compared to animals kept in the littered control barn (P < 0.001). A decrease in average hock health toward the end of the fattening period could be shown for both floor types. In addition, hock health was influenced by the fattening period with the highest hock health in the spring flock and the lowest in the summer flock (P < 0.001).

Figure 8.

Mean scores of hock burn with standard error from broilers kept on 2 different floor types measured weekly over 4 different fattening periods (repetitions; n = 200 animals per assessment day and barn). Significant differences are marked by asterisks: ∗∗∗P < 0.001.

Figure 9 presents the average weekly plumage cleanliness scores of the 4 fattening periods (repetitions). Average weekly plumage cleanliness was not affected by the 2 different floor types. Animals showed a continuous decrease in plumage cleanliness toward the end of the fattening period with the lowest pollution in the fall and the highest in the summer fattening period (P < 0.001).

Figure 9.

Mean scores of plumage cleanliness with standard error from broilers kept on 2 different floor types measured weekly over 4 different fattening periods (repetitions; n = 200 animals per assessment day and barn).

Production Performance

The average initial and final body weights (g bird−1) of the 4 fattening periods (repetitions) are shown in Table 3. Further information on body weight development can be found in Supplementary Table 8. There was an increase in body weight during each fattening period. In the fall and winter fattening periods, animals kept on the partially perforated flooring system started with a lower initial body weight compared to animals of the littered control barn. There were no differences in final body weight between both floor types at the end of each fattening period.

Table 3.

Average initial and final body weight of broilers kept on 2 different flooring systems of 4 different fattening periods (repetitions).

| Fattening period | Floor type | Day | n | Mean | SD | 95%-CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Summer | Littered | 0 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Part. perforated | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | ||

| Fall | Littered | 0 | 50 | 41.42 | 3.59 | [40.40];[42.44] |

| Part. perforated | 50 | 39.66 | 2.41 | [38.97];[40.35] | ||

| Winter | Littered | 0 | 50 | 43.82 | 3.35 | [42.87];[44.77] |

| Part. perforated | 50 | 41.86 | 3.02 | [41.00];[42.72] | ||

| Spring | Littered | 0 | 50 | 41.86 | 2.94 | [41.03];[42.69] |

| Part. perforated | 50 | 42.06 | 2.83 | [41.26];[42.87] | ||

| Summer | Littered | 31 | 20 | 2,007.35 | 253.10 | [1,888.90];[2,125.81] |

| Part. perforated | 20 | 1,904.20 | 227.72 | [1,797.62];[2,010.78] | ||

| Fall | Littered | 32 | 20 | 2,058.05 | 184.23 | [1,971.83];[2,144.27] |

| Part. perforated | 20 | 2,117.60 | 235.27 | [2,007.49];[2,227.71] | ||

| Winter | Littered | 32 | 20 | 2,101.55 | 208.83 | [2,003.81];[2,199.29] |

| Part. Perforated | 20 | 2,134.85 | 236.70 | [2,024.07];[2,245.63] | ||

| Spring | Littered | 32 | 20 | 1,930.40 | 244.26 | [1,816.09];[2,044.72] |

| Part. Perforated | 20 | 1,963.75 | 241.77 | [1,850.60];[2,076.90] |

The table contains the number of animals (n), mean values (mean), standard deviations of mean values (SD), and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI).

N/A, not available, the data were not collected during the summer fattening period.

Table 4 shows the feed consumption (kg bird−1), cumulative daily mortality (%), FCR, and EPEF of the 4 fattening periods (repetitions). There were no differences concerning the average production performance indicators of the 4 different fattening periods (repetitions) between both floor types.

Table 4.

Production performance indicators of broilers kept on 2 different flooring systems of 4 different fattening periods (repetitions; n = 4 calculated values per fattening period and barn).

| Summer | Fall | Winter | Spring | Mean | SD | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fattening period (d) | 31.00 | 32.00 | 32.00 | 32.00 | |||

| Feed consumption (kg bird−1) | |||||||

| Littered | 2.73 | 2.84 | 2.94 | 2.52 | 2.76 | 0.18 | [2.47];[3.04] |

| Part. perforated | 2.64 | 2.93 | 2.86 | 2.75 | 2.80 | 0.13 | [2.59];[3.00] |

| Cum. daily mortality (%) | |||||||

| Littered | 4.72 | 5.56 | 2.02 | 4.29 | 4.15 | 1.51 | [1.74];[6.56] |

| Part. perforated | 4.51 | 6.19 | 2.23 | 5.56 | 4.62 | 1.74 | [1.86];[7.39] |

| FCR1,2 | |||||||

| Littered | 1.395 | 1.41 | 1.43 | 1.33 | 1.39 | 0.04 | [1.32];[1.46] |

| Part. perforated | 1.425 | 1.41 | 1.37 | 1.43 | 1.41 | 0.03 | [1.37];[1.45] |

| EPEF3,4 | |||||||

| Littered | 444.08 | 431.29 | 450.37 | 432.69 | 439.61 | 9.18 | [425.00];[454.22] |

| Part. perforated | 413.92 | 440.26 | 477.34 | 404.99 | 434.13 | 32.47 | [382.47];[485.79] |

The table contains mean values (mean), standard deviation of mean values (SD), and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI).

FCR: feed conversion ratio.

FCR = feed consumption (kg bird−1)/total weight gain (kg bird−1).

EPEF: European Production Efficiency Factor.

EPEF = (survival rate (%) x final body weight (kg))/(age (d) x feed conversion ratio) x 100.

The average initial body weight was used to calculate the FCR of the summer fattening period.

Environmental Factors

The average daily Temp and RH of the 4 fattening periods (repetitions) are shown in Figure 10. There was a statistically significant correlation between the Temp in the barn with the partially perforated and the littered flooring system (r(60,599) = +0.959, P < 0.01, 2-tailed). In addition, the correlation between the RH of both floor types was found to be statistically significant (r(60,599) = +0.920, P < 0,01, 2-tailed).

Figure 10.

Average daily air temperature (Temp) and relative air humidity (RH) over 4 different fattening periods (repetitions) from broiler houses with 2 different flooring systems (n = 1,920 measurement values per day and barn).

Discussion

Behavior-Based Welfare Indicators

During the ADT, animals were less fearful of the observer toward the end of the fattening period when kept on the partially perforated flooring system compared to litter flooring. Baxter et al. (2019) also showed a reduction in general fearfulness for animals with access to perforated platform perches, assessed with the avoidance distance method by Graml et al. (2008). By contrast, Li et al. (2017) showed no effect of a totally (100%) perforated floor on general fearfulness during the ADT. Also, Çavuşoğlu and Petek (2019) showed no effect of a totally (100%) perforated floor on general fearfulness, using the avoidance distance method by Graml et al. (2008) and the tonic immobility test by Jones and Faure (1981). As known by Keer-Keer et al. (1996), different results in fear responses could be based on differences in the methodological approach.

Independent of the floor type, the lowest number of animals next to the observer was observed on day 7. So far, no studies have repeated the ADT every week of life. The highest number of animals around the observer was found on day 28. These findings are in line with the study of Li et al. (2017). Bokkers and Koene (2003) state that an increase in body weight could lead to a decrease in activity over time. The decrease in activity could be a reason for a higher number of animals around the observer at the end of the fattening period. Furthermore, animals cover a larger floor area with an increase in body weight. Consequently, animals have lower possibilities to evade the observer at the end of the fattening period.

Regarding the different fattening periods, the highest number of animals in arm's reach of the observer could be found in the summer and the lowest in the fall fattening period. A study by Aksit et al. (2006) found no effect of temperature during rearing and crating on the duration of tonic immobility in broilers. A lower number of animals in arm's reach of the observer was observed in the area of feed and water supply compared to the littered areas next to it. Fast-growing broilers spend more than 60% of their time sitting and resting during daytime (McLean et al., 2002). Buijs et al. (2010) showed that broilers use the wall areas more frequently for resting to avoid disturbance. This could explain the higher number of animals in arm's reach of the observer in the littered areas near the sidewalls. Furthermore, the number of animals around the observer increased with each trial carried out during the ADT at the different assessment days. The 12 trials at the 12 different positions were always carried out in the same order from front to back. Therefore, an increasing number of animals around the observer to the end of the ADT could indicate that the animals tried to avoid in front of him.

Current results regarding the NOT showed a positive effect of the partially perforated flooring system on general fearfulness. This result is in line with that by Tahamtani et al. (2018), who used the tonic immobility test by Jones and Faure (1981) to show a reduction in general fearfulness for broilers kept with access to perforated platforms.

Interestingly, the results independent of floor type are consistent for ADT and NOT. The least number of animals next to the novel object during the NOT was again observed on day 7. Andrew and Brennan (1983) found similar results for male chickens on day 7. They reported fluctuations in the fear reaction due to an incomplete brain development in the first 2 wk of life. The highest number of animals around the novel object was again observed on day 28. Bokkers and Koene (2003) reported a decrease in activity with an increase in body weight over the time. Therefore, animals kept on the partially perforated flooring system seem to be more active at the end of the fattening period compared to animals kept on litter. Further studies are needed to investigate the effect of the partially perforated flooring system on broiler activity. In further investigations, this hypothesis shall be proved with electronic activity sensors.

According to the results of the ADT, the highest number of animals around the novel object during the NOT was observed in the summer and the lowest in Fall fattening period. Before chickens were bred for intensive production, they had to adapt their behavior to constantly changing seasonal conditions (Newberry, 1999). Further research is needed to investigate the seasonal effect on broilers' fear response under current husbandry conditions. Furthermore, the highest number of animals around the novel object was observed at position 1 and the lowest at position 2. Between position 2 and position 4, the number of animals increased continuously. In addition, the fear response of the novel object decreased with increasing counting time. Rozempolska-Rucinska et al. (2017) reported a negative correlation between the exploration and fear behavior in laying hens. Therefore, the animals' fear of the novel object could decrease over the time with an increase in their exploration behavior.

Keeping broilers on a partially perforated flooring system contributed to a reduction in general fearfulness. Chickens use elevated structures as an anti-predator behavior (Newberry et al., 2001). As known by Malchow et al. (2019), broilers prefer elevated platforms instead of perches because of the difficulty to find a balanced resting position with increasing body weight. The partially perforated flooring system offered an elevated platform and, therefore, the opportunity to reach an elevated area. This husbandry enrichment and the resulting increase in husbandry complexity could be an explanation for a reduction in general fearfulness for animals kept on the partially perforated flooring system.

Health-Based Welfare Indicators

In general, the present study showed a positive effect of the partially perforated flooring system on foot pad health compared to litter flooring. Nevertheless, animals on day 7 showed a higher foot pad health when kept in the littered control barn. It was shown that average litter quality decreased during the fattening period. Furthermore, average litter quality in the control barn was lower in the area of feed and water supply compared to the littered areas next to it. A drastic deterioration of the litter quality was observed between day 7 and 14. Therefore, the positive effect of the perforated floor in the area of feed and water supply could only occur at a later stage of the fattening period. From day 14, foot pad health status for animals kept on the partially perforated flooring system was higher compared to those kept on litter at each day of life. This result is in line with several studies which have also observed a higher foot pad health status for animals kept on perforated flooring systems compared to litter flooring (Cengiz et al., 2013, Çavuşoğlu et al., 2018, Çavuşoğlu and Petek, 2019). In addition, Tahamtani et al. (2019) reported a higher foot pad health status for animals kept with access to elevated platforms compared to straw bales and an increased distance between feed and water. As mentioned by Karcher et al. (2013), perforated floors also had a positive effect on foot pad dermatitis for Peking ducks. In other studies, for example Li et al. (2017), no differences in the foot pad status for animals kept on a totally (100%) perforated floor compared to a littered system could be found. No differences in foot pad health were also reported by Chuppava et al. (2018) for animals kept on littered, littered and heated, partially (50%) perforated, and totally (100%) perforated flooring systems. These findings are in contrast to Almeida et al. (2017), who found a trend for higher foot pad dermatitis scores when animals were kept on a totally (100%) perforated compared to a littered floor. However, the animals of the study of Almeida et al. (2017) were kept in climate chambers and not under practical conditions, as in the present study.

Independent of the flooring system, the present study showed an increase in foot pad dermatitis from day 1 to 28 of life. There was a steady increase in foot pad dermatitis over time for animals kept on the littered floor. Interestingly, foot pad dermatitis scores of animals kept on the partially perforated flooring system remained almost constant from day 14. Although the recording periods differed between several studies, a similar trend could be observed by Cengiz et al., 2013, Li et al., 2017, and Çavuşoğlu and Petek (2019).

The highest foot pad dermatitis scores were found in the summer and the lowest in the fall fattening period. Meluzzi et al. (2008) reported the highest foot pad scores in winter. In addition, Musilová et al. (2013) found the lowest foot pad health in spring followed by winter and the highest in summer followed by fall. They concluded that the inadequate ventilation in winter month leads to an increase in barn and litter moisture levels and thus in a lower foot pad health. The results of the present study showed no differences in litter quality of the 4 fattening periods (repetitions).

For animals spending the whole fattening period in contact litter, the structure of the litter could have an effect on foot pad health (Bilgili et al., 2009). Therefore, Shepherd and Fairchild (2010) concluded that the litter conditions and the litter management are main factors influencing foot pad dermatitis. As known by Kamphues et al. (2011), animals are in contact with litter that contains higher proportions of excrements than fresh bedding material from day 7. Results of the present study also showed a decrease in average litter quality over the time. With a decrease in litter quality, a decrease in foot pad health was also shown by Haslam et al. (2007). Animals kept on the partially perforated flooring system were separated from 50% of the litter with those conditions. The partial separation had a positive effect on foot pad health by reducing the contact with the litter and the contained excrements and moisture.

Results for hock burn showed a higher hock health for animals kept on the partially perforated flooring system compared to litter flooring toward the end of the fattening period. Similar results regarding hock health were observed in several studies, all showing a higher hock health for animals kept on a perforated compared to a littered flooring system (Almeida et al., 2017, Çavuşoğlu et al., 2018, Çavuşoğlu and Petek, 2019). In addition, Li et al. (2017) found no differences regarding hock burn for animals kept on a totally (100%) perforated compared to a littered floor.

For both floor types, results of this study showed an increase in hock burn from day 1 to 28. This increase in hock burn over the time was also found by Li et al. (2017) and Çavuşoğlu and Petek (2019).

The highest hock burn scores were found in the summer and the lowest in the spring fattening period. Further studies showed contradictory results regarding the seasonal effect on the occurrence of hock burn. Bruce et al. (1990) reported a lower hock health status in winter. Menzies et al. (1998) showed no seasonal effect on hock burn in 1986/1087 and 1993 and a lower hock health status in winter 1994. No seasonal effect on hock burn was also shown by Haslam et al. (2007).

As mentioned by Elwinger and Svensson (1996), litter's dry matter content decreases over the fattening period from 92 to 64%. A decrease in hock health over the fattening period can be explained with an increase in body weight (Sørensen et al., 2000) and therefore an increased sitting time in direct contact with litter with an increasing moisture content (Hepworth et al., 2010). Results of the present study also showed a decrease in average litter quality over the time, especially in the area of feed and water supply of the control barn. Consequently, a reduction of contact time with those litter conditions due to the partially perforated flooring system results in a higher hock health status.

Regarding plumage cleanliness, no effect of the different floor types could be found. Numerous studies showed results with a higher plumage cleanliness for animals kept on a perforated flooring system compared to litter flooring (Akpobome and Fanguy, 1992, Almeida et al., 2017, Li et al., 2017, Çavuşoğlu et al., 2018, Çavuşoğlu and Petek, 2019). As reported by Kaukonen et al. (2017), the use of perforated platforms (10% of the floor area) had no effect on plumage cleanliness.

For both floor types, the present study showed a decrease in plumage cleanliness over time. Results of the studies of Li et al. (2017) and Çavuşoğlu and Petek (2019) also showed a decrease in plumage cleanliness over time for animals kept on litter and a totally (100%) perforated flooring system. Pecking, scratching, and dustbathing are behaviors with direct contact with litter. About 80% of litter's dry matter consists of excrements at the end of the fattening period (Kamphues et al., 2011). The decrease in litter quality could lead to a continuous contamination of the feathers with excrements during the exercise of species-specific behavior.

Production Performance

Regarding body weight, there was no difference for animals kept on the partially perforated floor system and the littered floor at the end of the fattening period. The results are in line with the results by Andrews et al., 1974, Simpson and Nakaue, 1987, Zhao et al., 2009, Cengiz et al., 2013, and Li et al. (2017). Chuppava et al. (2018) and Çavuşoğlu et al. (2018) found higher body weights for animals kept on partially (50%) or totally (100%) perforated flooring systems on days 36 and 47, respectively. Earlier results of Akpobome and Fanguy (1992) showed a reduction in production performance for animals kept on wire mesh floors compared to litter flooring on days 42 and 56. However, the animals of the study by Akpobome and Fanguy (1992) were kept in cages and not in deep-litter systems, as in the present study.

There was a general increase in body weight over the time for both floor types. This result is consistent with the performance objectives given for Ross 308 (Aviagen, 2019).

The 2 different floor types did not affect feed consumption, cumulative daily mortality, FCR, or EPEF. Several studies are in line and also showed no effect on feed consumption (Zhao et al., 2009, Li et al., 2017, Chuppava et al., 2018), mortality (Andrews et al., 1974, Cengiz et al., 2013, Li et al., 2017), and FCR (Andrews et al., 1974, Zhao et al., 2009, Cengiz et al., 2013, Li et al., 2017, Chuppava et al., 2018). With regard to the EPEF, De Jong et al. (2014) reported a higher EPEF for animals kept on litter compared to litter flooring with an increased moisture content (300 mL water addition per m2 from day 6, 5 times a week). This observation suggests that the litter management is an important factor influencing production performance.

Environmental Factors

Results showed a strong positive correlation for the Temp as well as the RH between the barn with the partially perforated and the littered flooring system. Therefore, identical Temp and RH conditions can be assumed during the fattening periods for both floor types.

Conclusion

Because animal welfare increases public awareness, a higher adaption of the husbandry environment to the animal's needs is gaining public interest. The idea of the study was to combine the positive effects of perforated and littered areas in broiler housing to increase animal welfare. The system offers an elevated area and reduces the animal's contact to litter with contained excrements and moisture at the same time. Littered areas promote the species-specific behavior like scratching, pecking, and dust bathing. The creation of different functional areas at different heights enriches the husbandry environment and reduces animals' general fearfulness due to an increase in environmental complexity. Furthermore, the separation of the animals from 50% of the litter has a positive influence on foot pad dermatitis and hock burn. This study illustrates a positive effect of a partially perforated flooring system on health- and behavior-based welfare indicators in broiler housing without a reduction in production performance. Further investigations are needed to evaluate the influence of the partially perforated flooring system on broilers' activity as well as environmental-based welfare indicators inside the barn and the environmental impact in general.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Educational and Research Center Frankenforst of the Faculty of Agriculture, University of Bonn (Königswinter, Germany) for the care of the animals and their comprehensive support. The study was funded by the Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture and supported by the Federal Office for Agriculture and Food (2817700214).

Conflict of Interest Statement: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psj.2020.04.008.

Supplementary data

References

- Akpobome G.O., Fanguy R.C. Evaluation of cage floor systems for production of commercial broilers. Poult. Sci. 1992;71:274–280. doi: 10.3382/ps.0710274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aksit M., Yalcin S., Ozkan S., Metin K., Ozdemir D. Effects of temperature during rearing and crating on stress Parameters and Meat quality of broilers. Poult. Sci. 2006;85:1867–1874. doi: 10.1093/ps/85.11.1867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida E.A., Souza L.F.A., Sant'Anna A.C., Bahiense R.N., Macari M., Furlan R.L. Poultry rearing on perforated plastic floors and the effect on air quality, growth performance, and carcass injuries - Experiment 1: Thermal Comfort. Poult. Sci. 2017;96:3155–3162. doi: 10.3382/ps/pex131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrew R.J., Brennan A. The lateralization of fear behavior in the male domestic chick: a developmental study. Anim. Behav. 1983;31:1166–1176. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews L.D., Seay R.L., Harris G.C., Nelson G.S. Flooring materials for caged broilers and their effect upon performance. Poult. Sci. 1974;53:1141–1146. [Google Scholar]

- Aviagen Ross 308 broiler management Handbook. 2018. http://en.aviagen.com/assets/Tech_Center/Ross_Broiler/Ross-BroilerHandbook2018-EN.pdf

- Aviagen Ross 308 performance objectives. 2019. http://en.aviagen.com/assets/Tech_Center/Ross_Broiler/Ross308-308FF-BroilerPO2019-EN.pdf

- Bach M.H., Tahamtani F.M., Pedersen I.J., Riber A.B. Effects of environmental complexity on behaviour in fast-growing broiler chickens. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2019;219:104840. [Google Scholar]

- Baxter M., Bailie C.L., O'Connell N.E. An evaluation of potential dustbathing substrates for commercial broiler chickens. Animal. 2018;12:1933–1941. doi: 10.1017/S1751731117003408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxter M., Bailie C.L., O'Connell N.E. Play behaviour, fear responses and activity levels in commercial broiler chickens provided with preferred environmental enrichments. Animal. 2019;13:171–179. doi: 10.1017/S1751731118001118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann S., Schwarzer A., Wilutzky K., Louton H., Bachmeier J., Schmidt P., Erhard M., Rauch E. Behavior as welfare indicator for the rearing of broilers in an enriched husbandry environment—a field study. J. Vet. Behav. 2017;19:90–101. [Google Scholar]

- Bilgili S.F., Hess J.B., Blake J.P., Macklin K.S., Saenmahayak B., Sibley J.L. Influence of bedding material on footpad dermatitis in broiler chickens. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 2009;18:583–589. [Google Scholar]

- Blokhuis H.J. The effect of a Sudden change in floor type on pecking behaviour in chicks. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1989;22:65–73. [Google Scholar]

- Bokkers E.A.M., Koene P. Behaviour of fast- and slow growing broilers to 12 weeks of age and the physical consequences. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2003;81:59–72. [Google Scholar]

- Bruce D.W., McIlroy S.G., Goodall E.A. Epidemiology of a contact dermatitis of broilers. Avian Pathol. 1990;19:523–537. doi: 10.1080/03079459008418705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buijs S., Keeling L.J., Vangestel C., Baert J., Vangeyte J., Tuyttens F.A.M. Resting or hiding? Why broiler chickens stay near walls and how density affects this. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2010;124:97–103. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera M.L., Kissel D.E., Hassan S., Rema J.A., Cassity-Duffey K. Litter type and number of flocks affect sex hormones in broiler litter. J. Environ. Qual. 2018;47:156–161. doi: 10.2134/jeq2017.08.0301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Çavuşoğlu E., Petek M., Abdourhamane İ.M., Akkoc A., Topal E. Effects of different floor housing systems on the welfare of fast-growing broilers with an extended fattening period. Arch. Anim. Breed. 2018;61:9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Çavuşoğlu E., Petek M. Effects of different floor materials on the welfare and behaviour of slow- and fast-growing broilers. Arch. Anim. Breed. 2019;62:335–344. doi: 10.5194/aab-62-335-2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cengiz Ö., Hess J.B., Bilgili S.F. Effect of protein source on the development of footpad dermatitis in broiler chickens reared on different flooring types. Arch.Geflügelk. 2013;77:166–170. [Google Scholar]

- Chuppava B., Visscher C., Kamphues J. Effect of different flooring designs on the performance and foot pad health in broilers and turkeys. Animals. 2018;70:1–12. doi: 10.3390/ani8050070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collett S.R. Nutrition and wet litter problems in poultry. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2012;173:65–75. [Google Scholar]

- De Jong I.C., Gunnink H., van Harn J. Wet litter not only induces footpad dermatitis but also reduces overall welfare, technical performance, and carcass yield in broiler chickens. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 2014;23:51–58. [Google Scholar]

- De Jong I.C., Gunnink H. Effects of a commercial broiler enrichment programme with or without natural light on behaviour and other welfare indicators. Animal. 2019;13:384–391. doi: 10.1017/S1751731118001805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunlop M.W., McAuley J., Blackall P.J., Stuetz R.M. Water activity of poultry litter. Relationship to moisture content during a grow-out. J. Environ. Manage. 2016;172:201–206. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2016.02.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elwinger K., Svensson L. Effect of dietary protein content, litter and Drinker type on Ammonia Emission from broiler houses. J. Agric. Engng Res. 1996;64:197–208. [Google Scholar]

- German Order on the Protection of Animals and the Keeping of Production Animals (German Designation: Tierschutz-Nutztierhaltungsverordnung). Publisht on August 22nd, 2006 (BGBl. I S. 2043) and last changed on June 30th, 2017 (BGBl. I S. 2147) 2006. https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/tierschnutztv/BJNR275800001.html

- Graml C., Waiblinger S., Niebuhr K. Validation of tests for on-farm assessment of the hen–human relationship in non-cage systems. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2008;111:301–310. [Google Scholar]

- Ham A.D., Osorio D. Colour preferences and colour vision in poultry chicks. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2007;274:1941–1948. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2007.0538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haslam S.M., Knowles T.G., Brown S.N., Wilkins L.J., Kestin S.C., Warriss P.D., Nicol C.J. Factors affecting the prevalence of foot pad dermatitis, hock burn and breast burn in broiler chicken. Br. Poult. Sci. 2007;48:264–275. doi: 10.1080/00071660701371341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepworth P.J., Nefedov A.V., Muchnik I.B., Morgan K.L. Early warning indicators for hock burn in broiler flocks. Avian Pathol. 2010;39:405–409. doi: 10.1080/03079457.2010.510500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones R.B., Faure J.M. Tonic immobility "righting time" in laying hens housed in cages and pens. Appl. Anim. Ethol. 1981;7:369–372. [Google Scholar]

- Kamphues J., Youssef I., Abd El-Wahab A., Üffing B., Witte M., Tost M. Influences of feeding and housing on foot pad health in hens and turkeys. Übers. Tiererernährg. 2011;39:147–195. [Google Scholar]

- Karcher D.M., Makagon M.M., Fraley G.S., Fraley S.M., Lilburn M.S. Influence of raised plastic floors compared with pine shaving litter on environment and Pekin duck condition. Poult. Sci. 2013;92:583–590. doi: 10.3382/ps.2012-02215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaukonen E., Norring M., Valros A. Evaluating the effects of bedding materials and elevated platforms on contact dermatitis and plumage cleanliness of commercial broilers and on litter condition in broiler houses. Br. Poult. Sci. 2017;58:480–489. doi: 10.1080/00071668.2017.1340588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keer-Keer S., Hughes B.O., Hocking P.M., Jones R.B. Behavioural comparison of layer and broiler fowl: measuring fear responses. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1996;49:321–333. [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Wen X., Alphin R., Zhu Z., Zhou Z. Effects of two different broiler flooring systems on production performances, welfare, and environment under commercial production conditions. Poult. Sci. 2017;96:1108–1119. doi: 10.3382/ps/pew440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malchow J., Berk J., Puppe B., Schrader L. Perches or grids? What do rearing chickens differing in growth performance prefer for roosting? Poult. Sci. 2019;98:29–38. doi: 10.3382/ps/pey320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean J.A., Savory C.J., Sparks N.H.C. Welfare of male and female broiler chickens in relation to stocking density, as indicated by performance, health and behaviour. Anim. Welf. 2002;11:55–73. [Google Scholar]

- Meluzzi A., Fabbri C., Folegatti E., Sirri F. Survey of chicken rearing conditions in Italy. Effects of litter quality and stocking density on productivity, foot dermatitis and carcase injuries. Br. Poultry Science. 2008;49:257–264. doi: 10.1080/00071660802094156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menzies F.D., Goodall E.A., McConaghy D.A., Alcorn M.J. An update on the epidemiology of contact dermatitis in commercial broilers. Avian Pathol. 1998;27:174–180. doi: 10.1080/03079459808419320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musilová A., Lichovníková M., Hampel D., Przywarová A. The effect of the season on incidence of footpad dermatitis and its effect on broilers performance. Acta Univ. Agric. Silvic. Mendelianae Brun. 2013;61:1793–1798. [Google Scholar]

- Newberry R.C. Exploratory behaviour of young domestic fowl. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1999;63:311–321. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1591(01)00135-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newberry R.C., Estevez I., Keeling L.J. Group size and perching behaviour in young domestic fowl. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2001;73:117–129. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1591(01)00135-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowaczewski S., Rosiński A., Markiewicz M., Kontecka H. Performance, foot-pad dermatitis and haemoglobin saturation in broiler chickens kept on different types of litter. Arch.Geflügelk. 2011;72:132–139. [Google Scholar]

- Rozempolska-Rucinska I., Kibala L., Prochniak T., Zieba G., Lukaszewicz M. Genetics of the novel object test outcome in laying hens. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2017;193:73–76. doi: 10.5713/ajas.16.0436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd E.M., Fairchild B.D. Footpad dermatitis in poultry. Poult. Sci. 2010;89:2043–2051. doi: 10.3382/ps.2010-00770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields S.J., Garner J.P., Mench J.A. Effect of Sand and wood-shavings bedding on the behavior of broiler chickens. Poult. Sci. 2005;84:1816–1824. doi: 10.1093/ps/84.12.1816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson G.D., Nakaue H.S. Performance and carcass quality of broilers reared on wire flooring, plastic Inserts, wood Slats, or plastic-Coated Expanded metal flooring each with or without Padded Roosts. Poult. Sci. 1987;66:1624–1628. [Google Scholar]

- Sørensen P., Su G., Kestin S.C. Effects of age and stocking density on Leg Weakness in broiler chickens. Poult. Sci. 2000;79:864–870. doi: 10.1093/ps/79.6.864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tahamtani F.M., Pedersen I.J., Toinon C., Riber A.B. Effects of environmental complexity on fearfulness and learning ability in fast growing broiler chickens. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2018;207:49–56. [Google Scholar]

- Tahamtani F.M., Pedersen I.J., Riber A.B. Effects of environmental complexity on welfare indicators of fast-growing broiler chickens. Poult. Sci. 2019;99:21–29. doi: 10.3382/ps/pez510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventura B.A., Siewerdt F., Estevez I. Access to Barrier perches improves behavior Repertoire in broilers. PLoS One. 2012;7:1–7. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villagrá A., Olivas I., Althaus R.L., Gómez E.A., Lainez M., Torres A.G. Behavior of broiler chickens in four different substrates: a Choice test. Rev. Bras. Cienc. Avic. 2014;16:67–76. [Google Scholar]

- Welfare Quality . Welfare Quality® Consortium; Lelystad, Netherlands: 2009. Welfare Quality® Assessment Protocol for Poultry (Broilers, Laying Hens) [Google Scholar]

- Zhao F.R., Geng A.L., Li B.M., Shi Z.X., Zhao Y.J. Effects of environmental factors on breast blister incidence, growth performance, and some biochemical indexes in broilers. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 2009;18:699–706. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.