Abstract

Introduction:

To objectively assess the quality of laparoscopic camera navigation (LCN), the structured assessment of LCN skills (SALAS) score was developed and validated for laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The aim of this pre-clinical study was to investigate the influence of LCN on surgical performance during virtual cholecystectomy (vCHE) using this score.

Methods:

A total of 84 medical students were included in this prospective study. Individual characteristics were assessed with questionnaires. Participants completed a structured 2-day training course on a validated virtual reality laparoscopic simulator. At the end of the course, all students took over LCN during vCHE, all performed by the same surgeon. The numbers of errors regarding centering, horizon adjustment and instrument visualisation as well as manual and verbal corrections by the surgeon were recorded to calculate the SALAS score (range 5–25) to investigate the influence of LCN on surgical performance. The study population was divided by the recorded SALAS score into low and medium performers (Group A; 1st–3rd quartile; n = 60) and high performers (Group B, 4th quartile, n = 21).

Results:

The SALAS score of the camera assistant correlates positively with the surgeon's overall performance in vCHE (P < 0.001), and the surgeon's virtual laparoscopic performance was significantly better in Group B (P < 0.001). Moreover, a significantly shorter operation time during vCHE was shown for Group B (Median (IQR); Group A: 508 s [429 s; 601 s]; Group B: 422 s [365 s; 493 s]; P = 0.001). Frequent gaming and a higher self-confidence to assist during a basic laparoscopic procedure were associated with a higher SALAS score (P = 0.013).

Conclusion:

In this pre-clinical setting, the surgeon's virtual performance is significantly influenced by the LCN quality. LCN by high performers resulted in a shorter operation time and a lower error rate.

Keywords: Camera navigation, laparoscopic simulation, minimal invasive surgery, surgical education, virtual surgery

INTRODUCTION

The adequate navigation of the laparoscope is of clinical importance and can alleviate or aggravate the procedural flow of a laparoscopic surgery. However, the influence of the camera navigation quality on surgical performance or patient outcome is not well investigated. Only few studies have shown that a general involvement of medical students or inexperienced residents in laparoscopic surgery tends towards longer operation time.[1,2,3] With the recently validated tool for the structured assessment of laparoscopic camera navigation (LCN) skills, the SALAS-score, it is now possible to objectively assess the quality of the camera assistance.[4] Virtual reality laparoscopy (VRL) simulators have been developed to train surgical skills in a safe environment and are well investigated regarding the transferability of performance to the operating room.[5,6] The software enables a measurement of surgical performance using metric calculations, time and errors.

The aim of the current study was to investigate the influence of the LCN quality on the surgeon's performance in a pre-clinical setting during a cholecystectomy performed on a VRL simulator as a basis for future intraoperative analyses.

METHODS

Study design

During this prospective study, a total of 84 participants were included. All students assisted during a virtual cholecystectomy (vCHE) which was always performed by the same resident (post-graduate year 5) of the surgical department (T. H.) on a VRL Simulator. The used simulator was a LapSim®, Software Version 2015, produced by Surgical Science (Göteborg, Sweden). The software divides the vCHE into two parts: vessel preparation (VP) and gallbladder dissection (GD) which have been analysed separately and combined.

Before the study, students were familiarised with the simulator during 21 2-day extracurricular peer-to-peer courses. The participants were introduced to the technical, anatomical and surgical background of laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

The standardised course included two exercises regarding camera navigation (0° and 30° scope), two for fine preparation ('fine dissection', 'clip applying') and three for instrument navigation ('peg transfer', 'grasping', lifting and grasping'). Two students were assigned as a surgical team (operator and camera assistant) for the bimanual tasks and alternated as operator and assistant.

Virtual performance assessment

The surgeons' and students' performance on the VRL simulator was evaluated based on the calculated Z- score, which is defined as z = x − μ/σ where x is the raw score, μ is the mean of the parameter and σ is the standard deviation of the parameter. The Z- scores for the singular items were sorted into three subcategories (time, handling economics and errors) and were also added up to yield a total Z- score for each task.

Camera navigation assessment

For the calculation of the SALAS score,[4] the virtual operation time and the number of errors regarding the centering of the operational field (centering), the correct angle of the horizon (horizon) and the instrument visualisation (target out of view) as well as verbal commands (verbal) and manual corrections (manual) by the surgeon during the vCHE were assessed by a trained medical student. Because of the reduced operation time in vCHE the scoring scale for horizon and centring of the original SALAS score needed to be slightly modified: The time frame was reduced since the original time frame of 30 min is not reached during vCHE [Table 1].

Table 1.

Modified rating scale - structured assessment of laparoscopic assistant skills score[4]

| Item | Score value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 | 5 | |

| Centering | >1/10 min | 1/10 min | 0-1/20 min |

| Horizon | >1/10 min | 1/10 min | 0-1/20 min |

| Target out of view | >2/operation | 1-2/operation | None |

| Verbal | >1/5 min | 0-1/5 min | None |

| Manual | >1/operation | 1/operation | None |

| Total score value | Sum of all items (range: 5-25) | ||

Group stratification

Participants that qualified for analysis were stratified into a low and medium performer (Group A) and high performer Group (B) based on the achieved SALAS score. Students were divided according to percentiles (A: SALAS ≤11, 1st–3rd quartile, n = 60; B: SALAS >11, 4th quartile, n = 21).

Questionnaire

To compare student characteristics with the individual SALAS score and VRL performance, questionnaires were used prior and after the course. These were constructed to identify personal characteristics, including sex, age, handedness, video game experience, previous laparoscopic and VRL experience and the confidence to assist during a simple laparoscopic procedure.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 23 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). The Spearmen coefficient was used for correlation analysis. The non-parametric Mann–Whitney U-test and the Kruskal–Wallis test were performed to analyse the differences between two groups. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data are presented as the median and interquartile range (IQR).

RESULTS

Study population

Three students had to be excluded from the study since they did not finish the course prior to the study (n = 2), or data were accidentally not recorded by the simulator (n = 1). The 81 students included in the analysis (36 male, 45 female) had a median age of 24 (range 20–35) years. Most participants (90%, n = 73) were right handed. The majority of students had no previous VRL experience (91%) and had never assisted during a laparoscopic surgery (80%). 83% denied frequent video gaming.

Influence of camera navigation on virtual performance

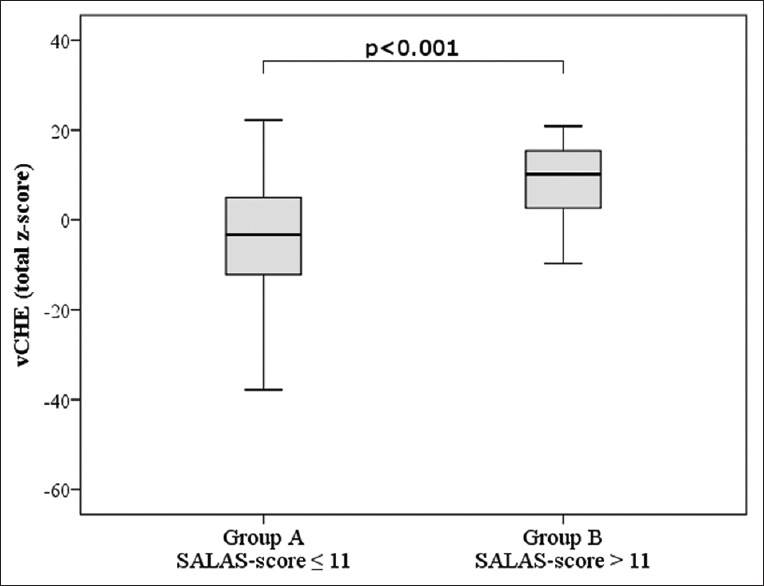

The SALAS score of the assisting student and the surgeons' Z- scores for VP (P < 0.001; r = 0.424), GD (P = 0.001; r = 0.415) as well as vCHE (P < 0.001; r = 0.520) reveal a positive correlation. A significant difference regarding the surgeon's performance in vCHE was obtained comparing LCN performance groups, favouring Group B [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Surgeon's performance during virtual cholecystectomy (vCHE). SALAS = structured assessment of laparoscopic assistant skills

Furthermore, fewer errors occurred during the vCHE in Group B (Median (IQR): group A: −2.39 (−8.54; 3.19) and Group B: 4.74 (0.97; 7.12); P < 0.001) [Table 2]. In detail, a better SALAS score (Group B) was associated with a shorter virtual operation time: surgical time was reduced by 86 s (16.9%; P < 0.001) between Group A 508 s (429 s; 601 s) and B 422 s (365 s; 493 s) in median (IQR). The camera assistant's gender, handedness, gaming frequency and experience with laparoscopic simulators had no significant influence on the surgeon's performance.

Table 2.

Surgeon’s grouped performance parameters in relation to assistant’s camera navigation skills

| Exercise | Z-score, median (IQR) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group A (SALAS-score ≤11) (n=60) | Group B (SALAS-score >11) (n=21) | ||

| Vessel preparation (VP) | −3.18 (−9.81; 2.35) | 5.76 (1.72; 8.71) | <0.001 |

| Efficiency | −0.66 (−3.30; 1.20) | 1.84 (0.53; 2.43) | 0.001 |

| Time | −0.20 (−1.07; 0.37) | 0.59 (0.35; 0.94) | <0.001 |

| Error rate | −2.11 (−5.06; 1.59) | 4.08 (0.78; 5.17) | <0.001 |

| Gallbladder dissection (GD) | −0.66 (−4.57; 4.30) | 5.13 (−0.61; 8.45) | 0.002 |

| Efficiency | −0.35 (−4.28; 3.35) | 3.75 (0.84; 5.50) | 0.003 |

| Time | 0.10 (−0.64; 0.46) | 0.58 (0.21; 0.88) | 0.003 |

| Error rate | 0.22 (−1.94; 2.05) | 1.61 (−0.30; 3.26) | 0.074 |

| Virtual cholecystectomy (vCHE) | |||

| Efficiency | −1.01 (−6.22; 2.34) | 5.15 (2.53; 7.16) | <0.001 |

| Time | −0.26 (−1.82; 0.80) | 1.20 (0.59; 1.60) | <0.001 |

| Error rate | −2.39 (−8.53; 3.19) | 4.74 (0.97; 7.12) | <0.001 |

IQR=Interquartile range; SALAS=Structured assessment of laparoscopic assistant skills

Camera assistant's characteristics

Comparison of Groups A and B did not reveal significant differences in VRL performance during the course prior to the study [Table 3].

Table 3.

Students’ virtual reality laparoscopic performance during the 2 days training course

| Exercise | Z-score, median (IQR) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group A (SALAS-score ≤11) (n=60) | Group B (SALAS-score >11) (n=21) | ||

| Camera navigation 0° | 0.61 (−1.92; 2.36) | 0.79 (−1.82; 2.29) | 0.98 |

| Camera navigation 30° | 1.01 (−0.43; 2.49) | 2.41 (−2.13; 3.51) | 0.40 |

| Fine dissection | 3.20 (−1.70; 5.32) | 3.68 (−3.07; 5.59) | 0.76 |

| Peg transfer | 1.11 (−1.11; 3.05) | 0.17 (−1.63; 3.81) | 0.91 |

| Clip applying | 2.58 (−1.08; 5.16) | 1.75 (−2.02; 4.59) | 0.42 |

| Grasping | 2.96 (−3.28; 4.91) | 3.51 (−2.09; 5.94) | 0.74 |

| Lifting and grasping | 4.07 (−5.45; 6.55) | 1.73 (−3.71; 7.24) | 0.98 |

SALAS=Structured assessment of laparoscopic assistant skills; IQR=Interquartile range

The obtained self-perception at the beginning of the course was not associated with the SALAS score (P = 0.720). Post-course self-perception is in concordance with the individual SALAS score: students, who felt confident to assist a laparoscopic surgery after the course, achieved a median SALAS score of 11 (9; 12) compared to unconfident students with a median score of 9 (7; 10.5) (P = 0.038).

Frequent gaming revealed a significant positive influence on the individual SALAS score (P = 0.013). Gender, handedness, experience with laparoscopic simulators or previous laparoscopic assistance had no influence on the students' performance regarding LCN scores, VRL scores or the obtained SALAS score (P ≥ 0.05).

The percentage of students with a very high or high interest in a surgical profession increased from 63% at the beginning to 70% at the end of the course (P = 0.51).

DISCUSSION

Aside from the performance of the surgeon, the quality of LCN is an important factor for a safe and efficient laparoscopic operation.[1,2] Yet, the influence of LCN quality on the surgeon's performance is not well investigated. Following Hirst's recommendation to perform surgical research also in a pre-IDEAL setting,[7] the current study was conducted using VRL simulation to analyse the influence of LCN quality on surgical performance. VRL simulators enable the training of manual and camera navigation skills independently. The training as a unit of two trainees per simulator has been proven efficient in laparoscopic simulation compared to training alone.[8] Furthermore, training as an interactive team (camera assistant and surgeon) improves collaboration and performance parameters in a VRL setup.[3]

The current results reveal that a better SALAS score is associated with a better surgical performance during vCHE. A significantly shorter virtual operation time was obtained, which is in concordance with the work of Babineau et al. and Mori et al., who stated that operation time increases when inexperienced assistants are involved. Since the degree of involvement remains unclear in these studies, it cannot be concluded, that the longer operation time was necessarily due to the camera navigation skills.[1,2] Furthermore, the surgeons' error rate was significantly lower in the current investigation for higher performing assistants. According to Zhu et al., an inexperienced assistant lacks the knowledge of the critical steps during an operation resulting in an inadequate view of the surgical field. Especially, a tilted view between 15° and 30° was documented during intraoperative complications.[9] A tilted view is also part of the SALAS score (item horizon) while it includes even more dimensions of LCN performance.

The students' self-perception regarding their camera navigation skills in relation to their objective ability was more precise after the study. This becomes even more important, since the students' own technical performance during the training course (Z- scores for LCN and manual skills) did not differ between Groups A and B. Laparoscopic manual skills and LCN performance are thus not related in the current study. We, furthermore, conclude that LCN during a surgical procedure cannot be estimated by the previous technical performance parameters on a simulator, suggesting that surgical VRL performance and LCN performance are not related.

Our own previous study with 488 medical students revealed a positive influence of frequent gaming on virtual LCN performance.[10] Likewise, frequent gaming was associated with a higher SALAS score in the current study but failed to reach significance regarding the students' performance during the VRL simulator exercises. Sammut et al. stated that frequent gaming was associated with statistically significant better results in maintaining the laparoscopic camera horizon. Both activities, gaming and camera navigation, require similar eye-hand and visual-spatial skills.[11] Roch et al. also found an association between the camera assistants' performance and the time to complete an LCN simulator task with their visual-spatial ability in their study with medical students and surgical residents.[12]

The visual-spatial ability of the students was not assessed in our study but could be an interesting amendment for further investigations. A further limitation of the current study is the study population of medical students with no experience in laparoscopic surgery resulting in a rather low median SALAS score of 11 compared to the validation study where LCN was performed by residents.[4] Thus, the group assignment was based on quartiles. Further studies with different cohorts including surgical residents will have to confirm the current results.

In addition, a comparison of virtual performance to the SALAS score would be helpful to further objectify the data. However, during a vCHE, the used simulator records the performance of the operating surgeon, not the performance of the assistant. Thus, the SALAS score needs to be assessed during vCHE to analyse LCN quality. Potentially, this will be possible with further software development of the VRL simulators. To further analyse the influence of camera navigation on laparoscopic performance, simultaneous intraoperative analysis of surgeon (e.g., GOALS score[13]) and camera assistant (SALAS score) should be part of future investigations.

CONCLUSION

The previously validated SALAS score can assess camera navigation skills in vCHE on a simulator. The surgeon's performance is significantly influenced by the LCN quality, and a higher SALAS score was associated with a shorter operation time and a lower error rate.

Financial support and sponsorship

The study was funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (FKZ: 16SV8057 “AVATAR”) and by intramural funding from the University Medical Center of the Johannes Gutenberg-University, Mainz (”MAICUM”).

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mori M, Liao A, Hagopian TM, Perez SD, Pettitt BJ, Sweeney JF. Medical students impact laparoscopic surgery case time. J Surg Res. 2015;197:277–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2015.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Babineau TJ, Becker J, Gibbons G, Sentovich S, Hess D, Robertson S, et al. The “cost” of operative training for surgical residents. Arch Surg. 2004;139:366–9. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.139.4.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huber T, Paschold M, Lang H, Kneist W. Influence of a camera navigation training on team performance in virtual reality laparoscopy. J Surg Sim. 2015;2:35–9. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huber T, Paschold M, Schneble F, Poplawski A, Huettl F, Watzka F, et al. Structured assessment of laparoscopic camera navigation skills: The SALAS score. Surg Endosc. 2018;32:4980–4. doi: 10.1007/s00464-018-6260-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Satava RM. Virtual reality surgical simulator.The first steps. Surg Endosc. 1993;7:203–5. doi: 10.1007/BF00594110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beyer-Berjot L, Aggarwal R. Toward technology-supported surgical training: The potential of virtual simulators in laparoscopic surgery. Scand J Surg. 2013;102:221–6. doi: 10.1177/1457496913496494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hirst A, Philippou Y, Blazeby J, Campbell B, Campbell M, Feinberg J, et al. No surgical innovation without evaluation: Evolution and further development of the IDEAL framework and recommendations. Ann Surg. 2019;269:211–20. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kowalewski KF, Minassian A, Hendrie JD, Benner L, Preukschas AA, Kenngott HG, et al. One or two trainees per workplace for laparoscopic surgery training courses: Results from a randomized controlled trial. Surg Endosc. 2019;33:1523–31. doi: 10.1007/s00464-018-6440-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhu A, Yuan C, Piao D, Jiang T, Jiang H. Gravity line strategy may reduce risks of intraoperative injury during laparoscopic surgery. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:4478–84. doi: 10.1007/s00464-013-3093-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paschold M, Niebisch S, Kronfeld K, Herzer M, Lang H, Kneist W. Cold-start capability in virtual-reality laparoscopic camera navigation: A base for tailored training in undergraduates. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:2169–77. doi: 10.1007/s00464-012-2735-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sammut M, Sammut M, Andrejevic P. The benefits of being a video gamer in laparoscopic surgery. Int J Surg. 2017;45:42–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2017.07.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roch PJ, Rangnick HM, Brzoska JA, Benner L, Kowalewski KF, Müller PC, et al. Impact of visual-spatial ability on laparoscopic camera navigation training. Surg Endosc. 2018;32:1174–83. doi: 10.1007/s00464-017-5789-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vassiliou MC, Feldman LS, Andrew CG, Bergman S, Leffondré K, Stanbridge D, et al. Aglobal assessment tool for evaluation of intraoperative laparoscopic skills. Am J Surg. 2005;190:107–13. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]