Abstract

Background:

The feasibility of minimally invasive approach for Crohn's disease (CD) is still controversial. However, several meta-analysis and retrospective studies demonstrated the safety and benefits of laparoscopy for CD patients. Laparoscopic surgery can also be considered for complex disease and recurrent disease. The aim of this study was to investigate retrospectively the effect of three minimally invasive techniques on short- and long-term post-operative outcome.

Patients and Methods:

We analysed CD patients underwent minimally invasive surgery in the Digestive Surgery Unit at Careggi University Hospital (from January 2012 to March 2017). Short-term outcome was evaluated with Clavien–Dindo classification and visual analogue scale for post-operative pain. Long-term outcome was evaluated through four questionnaires: Short Form Health Survey (SF-36), Gastrointestinal Quality Of Life Index (GIQLI), Body Image Questionnaire (BIQ) and Hospital Experience Questionnaire (HEQ).

Results:

There were 89 patients: 63 conventional laparoscopy, 16 single-incision laparoscopic surgery and 10 robotic-assisted laparoscopy (RALS). Serum albumin <30 g/L (P = 0.031) resulted to be a risk factor for post-operative complications. HEQ had a better result for RALS (P = 0.019), while no differences resulted for SF-36, BIQ and GIQLI.

Conclusions:

Minimally invasive technique for CD is feasible, even for complicated and recurrent disease. Our study demonstrated low rates of post-operative complications. However, it is a preliminary study with a small sample size. Further studies should be performed to assess the best surgical technique.

Keywords: Crohn's disease, minimally invasive surgery, quality of life

INTRODUCTION

Crohn's disease (CD) is a chronic relapsing disorder whose aetiology is still largely unknown. The incidence of CD has increased overall in Europe from 1.0/100,000 person-years in 1962 to 6.3/100,000 person-years in 2010.[1,2] Globally, 70%–83% of patients affected with CD will require surgery within 10 years from diagnosis.[1,2]

Mortality risk is increased up to 50% in CD when compared to the background population, and 25%–50% deaths are disease-specific (i.e., malnutrition, post-operative complications and intestinal cancer).[3,4,5,6]

In CD, surgical indication is linked to the medical therapy resistance or to the onset of complications (occlusion, fistulae, abscesses, intractable bleeding or growth delay in adolescence).[7,8,9,10]

Laparoscopy has experienced an overwhelming growth in a few years. Even in CD, several scientific studies show the advantages of laparoscopic surgery in terms of hospital stay, reduced post-operative pain, early re-feeding and preservation of the abdominal wall. In particular, in CD treatment, laparoscopy enabled significant improvements in outcome (less morbidity and a better cosmetic results compared to the open surgery).[11,12,13] Single-port laparoscopic surgery and robotic surgery may represent a further step towards the minimally invasive approach, but many aspects related to the feasibility in CD are still unknown and should be investigated in order to assess a new standard of care.[14,15] Even if pre-operative selection criteria are still debated and not standardised, the CD relapsing nature with the consequent risk for further reoperations, suggests that minimally invasive approach may not only be indicated for uncomplicated primary surgery but also for the treatment of recurrence or complex CD cases.[16]

In this study, we compared, in terms of post-operative pain, complications and long-term post-operative outcome, three different minimally invasive surgical techniques (single-incision laparoscopic surgery (SILS), conventional laparoscopy (CVL) and robotic-assisted laparoscopic surgery [RALS]) performed for CD patients.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

After internal ethical committee approval and written consent acquisition from all patients, we analysed patients affected by CD underwent to minimally invasive surgery from January 2012 to March 2017 at the Digestive Surgery Unit of Careggi University Hospital.

Three different surgery techniques were involved: SILS, CVL and RALS. These surgical procedures were performed by the same group of surgeons.

The indications for surgery were the failure of medical treatment or the onset of complications. Complete clinical records were available for all patients: age at diagnosis, age at surgery, presence of stricturing or penetrating disease, previous biological treatment and withdrawal period, concomitant corticosteroids therapy, type of resection, type of anastomosis, operative time, primary or recurrent surgery, length of post-operative stay, post-operative complications, nutritional status at the moment of surgery (body mass index (BMI), serum albumin and percentage of weight loss in the last 6 months before surgery) and pain at 2nd and 3rd post-operative day were recorded and statistically analysed. Post-operative pain was evaluated using the visual analogue scale (VAS). Post-operative complications were classified adopting the Clavien–Dindo classification.[17] We considered a malnourish patient, the presence of serum albumin not exceeding 30 g/L (ALB30), BMI not exceeding 18 kg/m2(BMI18) and weight loss ≥10% of the habitual weight in the last 6 months before surgery (WL10).

At follow-up on October 2018, all patients were asked to answer the following questionnaires: Gastrointestinal Quality Of Life Index (GIQLI), Body Image Questionnaire (BIQ), Hospital Experience Questionnaire (HEQ) and Short Form (36) Health Survey (SF-36).

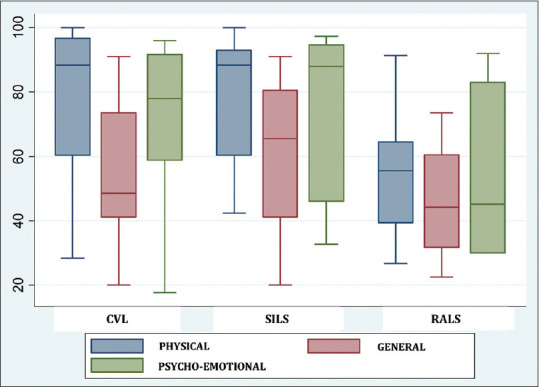

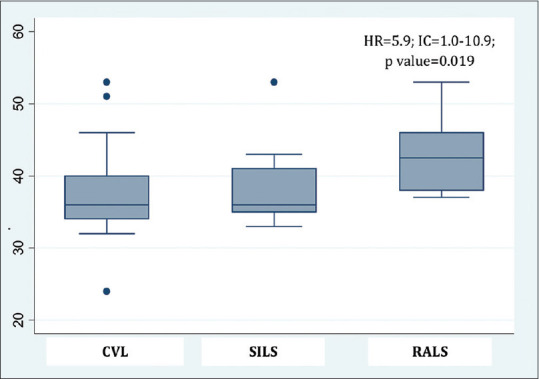

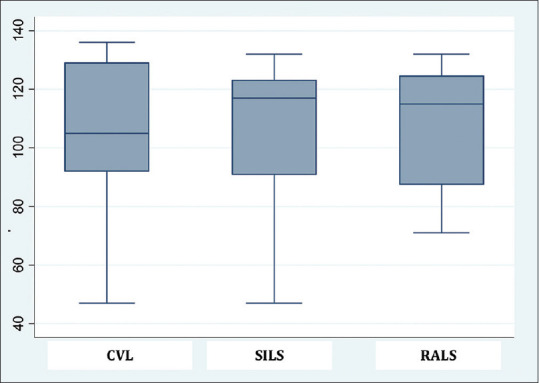

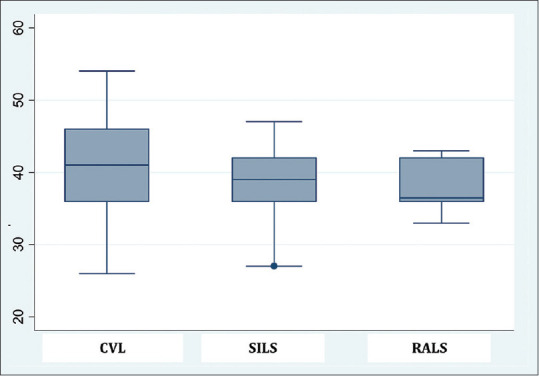

The SF-36 is divided into three principal arms: physical, psycho-emotional and general health. Higher is the score, less is the disability. They could run from 0 to 100. The GIQLI is a measure of the subjective perception of well-being of a patient. It includes 36 items with five answer categories for each item by rating the answers from 0 to 4, a global score ranging from 0 to 144 can be estimated. Higher the score, better is the quality of life. The HEQ is an evaluation of the hospital post-operative stay, including questions on post-operative complications and the importance given to them by the patients. The BIQ considers the relationship between body image and psychological aspects and surgical procedures.

All the clinical variables recorded as well as the questionnaires results obtained, were statistically analysed according to the different surgical approach adopted.

Statistical analysis

The main endpoint was to assess the relationship between the different minimally invasive surgical approach adopted and the post-operative outcome, in terms of post-operative complications, post-operative pain and GIQLI, BIQ, HEQ and SF-36 questionnaires in order to analyse if factors considered can influence the post-operative outcome.

The secondary endpoint was to verify if there were differences between the three groups in terms of nutritional status, presentation of disease, age at surgery and at diagnosis, previous biological treatment and withdrawal period, concomitant corticosteroids therapy, type of resection and anastomosis, primary or recurrent surgery in order to assess if some predictive factors could help in deciding the best surgical approach to be adopted, thus to clarify the possible surgical indications of these three different techniques.

Statistical analysis (univariate and multivariate models) was performed using SPSS (IBM Crop, SPSS inc., Chicago, USA) and creating 'logit' models with STATA software. P ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant, after verifying with the Chi-squared test the fit of the models.

Surgical technique

In case of SILS and CVL techniques, patients were positioned in a supine position, with the left arm adjacent to the body and the right open. For RALS, both arms were adjacent to the body. Usually, all the surgical procedures were performed starting with disinfection of the skin, mobilisation of the right hemicolon from the caecum to the transverse colon with complete dissection of the right flexure with visualisation of the right ureter and careful protection of the duodenum, exteriorisation of the right colon with the terminal ileum, inspection of the whole bowel searching for another site of the disease and ligature of the vessels and anastomosis.

In particular, for the SILS technique, a paraumbelical single incision with a mean length of 4 cm was performed and a SILS port system inserted. We utilised in the majority of cases 'the glove port technique' with three trocars: two 5 mm instruments and one of 10 mm for a 30° laparoscope.[18]

For CVL, a 10-mm periumbilical trocar for the camera, others 5- and 10-mm trocars were positioned in the left iliac fossa and left flank, respectively. In case of very difficult adhesiolysis, a further 5-mm trocar was put below the xiphoid. For RALS, the trocar placement was similar to CVL, four trocars, three for the robot arms and one for the assistant. After the insertion of the trocars, the robot is brought over the right upper quadrant to dock with the camera port periumbilically and the right lower and left upper quadrant ports.

RESULTS

From January 2012 to March 2017, a total of 102 patients with CD underwent minimally invasive surgery at the digestive surgery unit of Careggi University hospital of Florence.

No mortality rate was recorded in the post-operative course. The mean follow-up time was 4.3 years (range 1.6–9.6 years).

Conversion rate was of 12.7% (13 patients among the CVL group). Therefore, we considered for statistical analysis the remaining 89 patients who underwent a minimally invasive surgery; they were 43 male (48.3%) and 46 female (51.7%). According to the Montreal classification, there were 5 patients (5.62%) classified as A1 (≤16 years), 50 patients (56.18%) as A2 (17–40 years) and 34 patients (38.20%) as A3 (>40 years). Globally, the mean age at diagnosis was 35.0 years (standard deviation [SD] ± 15.8). The mean age at surgery was 42.8 years (SD ± 15.1) among males and 43.6 years (SD ± 16.6) between females.

ALB30 was observed in 20 patients (22.5%), BMI 18 in 17 patients (19.1%) and WL10 in 27 patients (30.3%).

The type of the disease was penetrating in 3 patients (3.4%), stricturing in 65 patients (73%) and both in 21 patients (23.6%).

The patients that had experienced medical treatment with biological drugs (Infliximab) before surgery were 16 (17.9%), among these, the median time of the withdrawal period was 41.6 days (SD ± 30.7). The patients treated with corticosteroids up to the moment of surgery, were 46 (51.7%). All patients were treated with 20 mg of methylprednisolone at maximum. However, in this study, we have not statistical relationship between pre-operatory drugs and post-operative complications. The surgical approach adopted was: CVL in 63 patients (70.8%), SILS in 16 patients (18.0%) and RALS in 10 patients (11.2%). Recurrent surgery was performed in 14 patients (15.7%): in 10 patients (71.4%), it was performed adopting CVL and in 4 patients (28.6%) adopting SILS. No recurrence surgery was approached with RALS. Globally, the mean operative time was 191.0 min, while analysing the three different surgical approaches; it was 188.1 min for CVL, 175.3 min for SILS and 234.5 min for RALS.

Ileocecal resection was performed in 83 patients (93.3%), rectal anterior resection in 2 patients (2.2%), total colectomy in 2 patients (2.2%), ileal resection in 1 patient (1.1%) and an extracorporeal side-to-side isoperistaltic strictureplasty in 1 patient (1.1%).

The more frequently performed ileo-colic anastomosis was the handsawn side-to-side isoperistaltic (48 patients, 53.9%). A stapled side-to-side was performed in 22 patients (24,7%). The others anastomosis performed were: stapled isoperistaltic in 8 patients (8.9%), kono in 7 patients (7.8%), stapled ileorectal in 1 patient (1.1%), stapled coloanal in 1 patient (1,1%), manual colorectal in 1 patient (1.1%) and one patient (1.1%) received a definitive ileostomy.

Globally, the mean post-operative stay was 6.7 days (SD ± 2.5); it was 7.0 days (SD ± 2.7) for patients operated with CVL, 5.4 days (SD ± 0,9) adopting SILS and 6.7 days (SD ± 2.3) in RALS subgroup.

The mean post-operative pain evaluated at the second and third post-operative day (VAS2, VAS3) were, respectively, 2 (SD ± 1.9) and 0 (SD ± 1.9). The VAS2 was higher among patients of the RALS group (2.7).

Eleven patients (12.3%) experienced post-operative complication recorded according to Clavien–Dindo. One patient (1.1%) developed wound infection (Grade I); six patients (6.7%) had a Grade II complication (4 blood loss requiring blood transfusions and 2 phlebitis) and four patients (4.5%) required reoperation (Grade III) because of anastomotic leakage (3 patients) and haemoperitoneum (1 patient).

No complications were recorded with RALS technique.

Table 1 ('population characteristics') shows clinical results recorded in the pre-operative, intraoperative and short term post-operative course stratified on the three different minimally invasive surgical techniques.

Table 1.

Population characteristics

| CVL | SILS | RALS | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, n° (%) | 63 (70.8) | 16 (18) | 10 (11.2) |

| Gender, n° (%) | |||

| Male | 31 (49.2) | 10 (62.5) | 2 (20) |

| Female | 32 (50.8) | 6 (37.5) | 8 (80) |

| Median age at diagnosis (years) | 28.1 (11.6-67.2) | 34.8 (14.2-51.5) | 45.4 (22.4-67.8) |

| Median age at surgery (years) | 41.5 (17.2-76.9) | 41.4 (19.5-63.8) | 52.9 (26.9-82.3) |

| Behaviour, n° (%) | |||

| Stricturing | 47 (74.6) | 8 (50) | 10 (100) |

| Penetrating | 2 (3.2) | 1 (6.3) | - |

| Stricturing and penetrating | 14 (22.2) | 7 (43.8) | - |

| Pre-operative biologics, n° (%) | 11 (17.5) | 2 (12.5) | 2 (20) |

| Biologics withdrawal period (days) | 47.8 | 16.7 | 45 |

| Pre-operatory corticosteroids, n° (%) | 35 (55.6) | 7 (43.8) | 4 (40) |

| Mean post-operative stay (days) | 7.0±2.7 | 5.4±0.9 | 6.7±2.3 |

| Median VAS | |||

| D2 | 2 (0-8) | 2 (0-6) | 2.5 (0-5) |

| D3 | 0 (0-8) | 0 (0-6) | 0 (0-3) |

| Complications, n° (%) | |||

| Grade I | - | 1 (6.3) | - |

| Grade II | 6 (9.5) | - | - |

| Grade III | 4 (6.3) | - | - |

| Nutritional status, n° (%) | |||

| BMI18 | 12 (19) | 2 (12.5) | 3 (30) |

| ALB30 | 16 (25.4) | 2 (12.5) | 2 (20) |

| WL10 | 20 (31.7) | 3 (18.8) | 4 (40) |

| Redo surgery, n° (%) | 10 (15.9) | 4 (25) | - |

| Type of anastomosis, n° (%) | |||

| Mechanical L-L | 21 (33.3) | 1 (6.3) | - |

| Manual L-L isoperistaltic | 34 (53.9) | 7 (43.8) | 7 (70) |

| Kono | 2 (3.2) | 5 (31.3) | - |

| Ileorectal | 1 (1.6) | - | - |

| Coloanal | 1 (1.6) | - | - |

| Mechanical L-L isoperistaltic | 2 (3.2) | 3 (18.8) | 3 (30) |

| Manual colorectal | 1 (1.6) | - | - |

| Terminal ileostomy | 1 (1.6) | - | - |

| Median operative time | 180 (90-385) | 180 (120-230) | 240 (130-385) |

CVL: Conventional laparoscopy, SILS: Single incision laparoscopic surgery, RALS: Robotic-assisted laparoscopic surgery, VAS: Visual analogue scale, BMI: Body mass index, ALB: Albumin, WL: Weight loss

At follow-up, 6 patients refused to answer all the questionnaires (6.7%), the remaining 76 patients (85.4%) completed all the questionnaires: the results obtained in relationship with the different surgical approach adopted, are described in Table 2 ('Questionnaires').

Table 2.

Questionnaires results

| CVL | SILS | RALS | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SF-36, mean±SD | |||

| Physical health | 79±21.2 | 81±19.2 | 55±21.4 |

| General health | 56±20.1 | 62±23.0 | 46±19.3 |

| Psycho-emotional health | 72±22.1 | 75±24.1 | 55±27.8 |

| GIQLI, mean±SD | 107±22.8 | 102±28.6 | 107±22.4 |

| BIQ, mean±SD | 40±6.7 | 38±6.2 | 38±3.7 |

| HEQ, mean±SD | 37±6.7 | 39±6.4 | 43±5.4 |

CVL: Conventional laparoscopy, SILS: Single-incision laparoscopic surgery, RALS: Robotic-assisted laparoscopic surgery, SF-36: Short Form Health Survey-36, SD: Standard deviation, GIQLI: Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index, BIQ: Body Image Questionnaire, HEQ: Hospital Experience Questionnaire

Statistical analysis of complications related to the risk factors considered is reported in Table 3 ('Complication risk factors'). Analysis of major post-operative pain at the 3rd post-operative day (VAS3) is reported in Table 4 ('VAS3 risk factors').

Table 3.

Complication risk factors

| Risk factors | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 1 (reference) | 0.529 | 1 (reference) | 0.103 |

| Female | 1.5 (0.4-5.9) | −1.7 (−5.7-3.4) | ||

| Type of disease | ||||

| Stricturing | 1 (reference) | 0.663 | 1 (reference) | 0.735 |

| Penetrating | 1.4 (0.3-5.9) | 0.3 (2.9-8.6) | ||

| Penetrating + stricturing | 1.4 (0.3-6.9) | −0.4 (−1.6-4.04) | ||

| Pre-operative biologics | ||||

| No | 1 (reference) | 0.860 | 1 (reference) | 0.734 |

| Yes | 1.2 (0.2-6.1) | 0.34 (1.4-4.2) | ||

| Pre-operative corticosteroids | ||||

| No | 1 (reference) | 0.578 | 1 (reference) | 0.435 |

| Yes | 1.5 (0.4-5.6) | 0.8 (3.5-4.5) | ||

| BMI18 | 1.9 (0.5-8.7) | 0.359 | −0.48 (0.6-0.5) | 0.629 |

| ALB30 | 6.9 (1.7-27.9) | 0.006 | 5.35 (1.2-24.7) | 0.031 |

| WL10 | 4.1 (1.1-16.1) | 0.041 | 1.28 (2.9-2.4) | 0.202 |

| Re-do surgery, n° (%) | 2.6 (0.6-11.8) | 0.201 | 1.34 (3.3-2.9) | 0.181 |

BMI: Body mass index, ALB: Albumin, WL: Weight loss, CI: Confidence interval, HR: Hazard ratio

Table 4.

Visual analogue scale 3 risk factors

| Risk factors | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 1 (reference) | 0.969 | 1 (reference) | 0.932 |

| Female | 0.9 (0.3-3.6) | 1.06 (0.2-4.5) | ||

| CVL | 0.9 (0.2-4.0) | 0.954 | 1.0 (0.99-1.01) | 0.503 |

| SILS | 2.2 (0.5-9.5) | 0.302 | 5.4 (0.8-36.8) | 0.081 |

| RALS | - | - | - | - |

| Re-do surgery, n° (%) | 1.7 (5.4-5.2) | 0.162 | 1.0 (0.9-1.1) | 0.915 |

CVL: Conventional laparoscopy, SILS: Single-incision laparoscopic surgery, RALS: Robotic-assisted laparoscopic surgery, CI: Confidence interval, HR: Hazard ratio

From [Figures 1-4], we reported a visual representation of the questionnaires according to the type of surgery. Furthermore, we have compared the results of the questionnaire for each subgroup (CVL, SILS and RALS).

Figure 1.

Short Form Health Survey-36 questionnaire stratified according to the surgical technique

Figure 4.

Hospital Experience Questionnaire stratified according to the surgical technique

Figure 2.

Gastrointestinal Quality Of Life Index Questionnaire stratified according to the surgical technique

Figure 3.

Body Image Questionnaire stratified according to the surgical technique

Multivariate analysis filled with all the variables considered in this study, showed a statistical significance only for ALB30 for having post-operative complications P = 0.031, 5.35 (1.2–24.7), with a concrete Chi-squared.

Operative time was longer for group underwent RALS (235 min, 188 for CVL and 175 for SILS), without a statistical difference. We did not find a statistical significance between the type of surgery and the post-operative complications between surgical- and non-surgical-site complications. However, we noticed that SILS is linked to have more pain in 3rd post-operative day, P = 0.08, 5.4 (0.79–36.84).

DISCUSSION

According to short- and long-term post-operative outcome, our study has not reported significant statistical differences among CVL, SILS and RALS. It could be linked to a different sample size of each surgical group considered. However, the characteristics of the population were equally distributed.

The serum albumin <30 g/L had a statistical significance in terms of post-operative complications [Table 3], and SILS seems to have a statistical influence in having more post-operative pain at day 3rd, probably related to a longer abdominal incision [Table 4].

In this study, we have focalised the attention not only on the objective characteristics of patients (such as the age at diagnosis, the pre-operative therapy or nutritional status) but, through the questionnaires proposed, also on patients' personal experience of operative and post-operative treatment. We analysed if there were differences between the type of surgical techniques used, in order to understand if they could have influenced the quality of life [Figures 1-4].

Interestingly, patients treated with RALS seemed to have poorer physical health (P = 0.009), but these data are not justified by a statistical difference in this type of population analysing possible interactions between the variables contained in the subgroup of patients. Furthermore, comparing median results at HEQ according to the type of surgical technique, we have noticed that patients treated by RALS had a meaningful better HEQ [Figure 4]. We could explain that result by the hypothesis that robotic surgery has a great influence in emotional part of the patients.

We have recorded less conversion rate comparing to the median of the ones present in the literature: in a multicentric review by Mino et al., a conversion rate from 15% to 70% was reported,[19] Moorthy et al. compared conversion rate in primary and recurrence surgery for CD finding 13% and 42%, respectively (globally 28%).[20] Only one study of Nguyen et al. records a very low conversion rate of only 2%.[21]

The major complication rate observed in this study seems lower than in literature: we globally had experienced three anastomotic leakages and one haemoperitoneum (4.5%) versus 15.8% up to 17% reported in literature for CD operation in an elective setting (Schad et al. and Moorthy et al.).[20,22] This could be due to a better pre-operative selection of patients to be operate with a minimally invasive approach.

In the literature, several studies compare SILS and CVL or SILS and open surgery or CVL and open surgery.[23,24] At this moment, we did not find studies with a comparison between CVL, SILS and RALS. We can consider our study a preliminary study, actually we are performing other cases that are going to be recorded.

However, laparoscopic approach can be considered as one of the major technical advances in colorectal surgery over the last 20 years. It has now become the standard of care in many colorectal diseases with demonstrated short and long-term benefits over the open approach. However, its acceptance and widespread for CD surgical management have been slower than for other benign, and even malignant, conditions.[25]

The immediate advantages of laparoscopic surgery are smaller, less painful wounds, decreased analgesic requirements, quicker recovery, earlier return to normal diet, shorter hospital stays and better cosmetic results. Enhanced recovery protocols using standardised nutrition, analgesia and mobilisation help to improve recovery. There is also the potential for reducing incisional hernias and decreasing adhesion formation. Potential difficulties specific to CD are the adherent nature of the disease, the presence of fistulas, the thickened vascular mesentery and the subtle nature of some multisite small bowel strictures.[26,27]

Systematic review of laparoscopic surgery for ileo-colic disease suggests it is as safe as open surgery.[12] Meta-analyses have shown benefits with decreased hospital stay and possibly a decrease in complications and hernia formation.[13,24] An analysis of outcomes from the NSQIP database of ileo-colic resections for Crohn's went further and suggested laparoscopic surgery was associated with lower major and minor complications and decreased hospital stay, and should be the first option whenever possible.[28,29] Long-term follow-up suggests laparoscopic resection does not influence recurrence rates.[12,24,29] Laparoscopic surgery can also be considered for complex disease and recurrent disease.[16,18,27] Finally, many studies and meta-analyses have nowadays demonstrated the safety and benefits of laparoscopic approach for CD surgery.

CONCLUSIONS

Questionnaires proposed in this study could help to have a more consciously approach to such complicated patients affected by a chronic disease with a high risk of surgical complications and recurrence.

Our study confirms not only the feasibility of CVL but also SILS and RALS in CD. In fact, these techniques performed in a tertiary centre, showed low rates of short and long-term post-operative complications. Further studies are needed to assess specific selection criteria for each surgical technique.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bernell O, Lapidus A, Hellers G. Risk factors for surgery and recurrence in 907 patients with primary ileocaecal Crohn's disease. Br J Surg. 2000;87:1697–701. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01589.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ramadas AV, Gunesh S, Thomas GA, Williams GT, Hawthorne AB. Natural history of Crohn's disease in a population-based cohort from Cardiff (1986-2003): A study of changes in medical treatment and surgical resection rates. Gut. 2010;59:1200–6. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.202101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernstein CN, Blanchard JF, Kliewer E, Wajda A. Cancer risk in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A population-based study. Cancer. 2001;91:854–62. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010215)91:4<854::aid-cncr1073>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Binder V, Hendriksen C, Kreiner S. Prognosis in Crohn's disease – Based on results from a regional patient group from the county of Copenhagen. Gut. 1985;26:146–50. doi: 10.1136/gut.26.2.146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Persson PG, Karlén P, Bernell O, Leijonmarck CE, Broström O, Ahlbom A, et al. Crohn's disease and cancer: A population-based cohort study. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:1675–9. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90807-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gollop JH, Phillips SF, Melton LJ, 3rd, Zinsmeister AR. Epidemiologic aspects of Crohn's disease: A population based study in Olmsted county, Minnesota, 1943-1982. Gut. 1988;29:49–56. doi: 10.1136/gut.29.1.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hefaiedh R, Sabbeh M, Miloudi N, Ennaifer R, Romdhane H, Belhadj N, et al. Surgical treatment of Crohn's disease: Indications, results and predictive factors of recurrence and morbidity. Tunis Med. 2015;93:356–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kolar B, Speranza J, Bhatt S, Dogra V. Crohn's disease: Multimodality imaging of surgical indications, operative procedures, and complications. J Clin Imaging Sci. 2011;1:37. doi: 10.4103/2156-7514.82966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alós R, Hinojosa J. Timing of surgery in Crohn's disease: A key issue in the management. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:5532–9. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.5532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Toh JW, Stewart P, Rickard MJ, Leong R, Wang N, Young CJ. Indications and surgical options for small bowel, large bowel and perianal Crohn's disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:8892–904. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i40.8892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soop M, Larson DW, Malireddy K, Cima RR, Young-Fadok TM, Dozois EJ. Safety, feasibility, and short-term outcomes of laparoscopically assisted primary ileocolic resection for Crohn's disease. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:1876–81. doi: 10.1007/s00464-008-0308-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dasari BV, McKay D, Gardiner K. Laparoscopic versus open surgery for small bowel Crohn's disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;19:CD006956. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006956.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tilney HS, Constantinides VA, Heriot AG, Nicolaou M, Athanasiou T, Ziprin P, et al. Comparison of laparoscopic and open ileocecal resection for Crohn's disease: A metaanalysis. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:1036–44. doi: 10.1007/s00464-005-0500-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bucher P, Pugin F, Morel P. Single port access laparoscopic right hemicolectomy. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2008;23:1013–6. doi: 10.1007/s00384-008-0519-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heeney A, O'Connor DB, Martin S, Winter DC. Single-port access laparoscopic surgery for complex Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:1273–4. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tavernier M, Lebreton G, Alves A. Laparoscopic surgery for complex Crohn's disease. J Visc Surg. 2013;150:389–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jviscsurg.2013.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: A new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205–13. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000133083.54934.ae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moftah M, Nazour F, Cunningham M, Cahill RA. Single port laparoscopic surgery for patients with complex and recurrent Crohn's disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:1055–61. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2014.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mino JS, Gandhi NS, Stocchi LL, Baker ME, Liu X, Remzi FH, et al. Preoperative risk factors and radiographic findings predictive of laparoscopic conversion to open procedures in Crohn's disease. J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;19:1007–14. doi: 10.1007/s11605-015-2802-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moorthy K, Shaul T, Foley RJ. Factors that predict conversion in patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery for Crohn's disease. Am J Surg. 2004;187:47–51. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2002.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nguyen SQ, Teitelbaum E, Sabnis AA, Bonaccorso A, Tabrizian P, Salky B. Laparoscopic resection for Crohn's disease: An experience with 335 cases. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:2380–4. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0362-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schad CA, Haac BE, Cross RK, Syed A, Lonsako S, Bafford AC. Early postoperative anti-TNF therapy does not increase complications following abdominal surgery in Crohn's disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2019;25:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s10620-019-5476-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Okabayashi K, Hasegawa H, Watanabe M, Nishibori H, Ishii Y, Hibi T, et al. Indications for laparoscopic surgery for Crohn's disease using the Vienna classification. Colorectal Dis. 2007;9:825–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2007.01294.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patel SV, Patel SV, Ramagopalan SV, Ott MC. Laparoscopic surgery for Crohn's disease: A meta-analysis of perioperative complications and long term outcomes compared with open surgery. BMC Surg. 2013;13:14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2482-13-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosman AS, Melis M, Fichera A. Metaanalysis of trials comparing laparoscopic and open surgery for Crohn's disease. Surg Endosc. 2005;19:1549–55. doi: 10.1007/s00464-005-0114-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maggiori L, Panis Y. Laparoscopy in Crohn's disease. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;28:183–94. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2013.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pinto RA, Shawki S, Narita K, Weiss EG, Wexner SD. Laparoscopy for recurrent Crohn's disease: How do the results compare with the results for primary Crohn's disease? Colorectal Dis. 2011;13:302–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2009.02133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee Y, Fleming FJ, Deeb AP, Gunzler D, Messing S, Monson JR. A laparoscopic approach reduces short-term complications and length of stay following ileocolic resection in Crohn's disease: An analysis of outcomes from the NSQIP database. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14:572–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2011.02756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lowney JK, Dietz DW, Birnbaum EH, Kodner IJ, Mutch MG, Fleshman JW. Is there any difference in recurrence rates in laparoscopic ileocolic resection for Crohn's disease compared with conventional surgery.A long-term, follow-up study? Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:58–63. doi: 10.1007/s10350-005-0214-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]