Abstract

The cuticle is the outmost layer of the eggshell and may affect the hatchability by modulating eggshell conductance. Three different solutions using acetic acid (AA), vinegar (V), and citric acid (CA) for cuticle removal by egg washing were developed, and the effects of cuticle removal on hatching performance of quail hatching eggs were evaluated. A total of 5,238 fresh quail hatching eggs were randomly divided into 9 treatments as follows: unwashed control, nondipped (CND); washed control, water dipped (CWD); standard control, 0.13% sodium hyperchlorite (CSH); 2% AA (AA2); 4% AA (AA4); 44.4% V (V2); 88.8% V (V4); 2% CA (CA2); and 4% CA (CA4). Overall, AA4, V4, and CA4 treatments significantly improved the hatchability of fertile eggs (95.42%, 94.16% and 95.66%, respectively) (P < 0.05) and the hatchability of CND, CWD, CSH, AA2, V2 and CA2 treatments were 90.98%, 93.00%, 92.27%, 79.44%, 90.37%, and 90.59%, respectively. The eggshell thickness and cuticle quality results showed that all AA, V, and CA solutions can effectively remove the quail eggshell cuticle, and AA4, V4 and CA4 significantly decreased eggshell thickness (P < 0.05). Microbial activity on the eggshell surface in all acid treatments was reduced significantly at day 0 of incubation (P < 0.05) and that significantly decreased than controlled treatments over the incubation period except AA2 treatment.

Egg weight loss was lower for all acid treatments than that of the CND treatment (P < 0.05). There was no clear effect of treatments on chick quality. Hatch time in AA4, V4, and CA4 treatments slightly improved compared with controlled treatments (P > 0.05). There were no significant differences between treatments for chick livability and live weight at the first 21 D of life. Results of the present study indicate that cuticle removal with AA4, V4, or CA4 could effectively decrease the microbial activity on the eggshell surface during the incubation period and improve hatchability of quail hatching eggs without negative effects on hatch time and performance of quail chicks.

Key words: eggshell cuticle, egg washing, hatchability, chick quality, quail

Introduction

Quail farming for egg and meat production is of great economic interest to the world poultry industry, owing to its low investment cost and excellent nutritional value (Baumgartner, 1994, Hamm and Ang, 2010, Tunsaringkarn et al., 2013). Quail farming has been encouraged and promoted in certain developing countries, and China has become one of the largest quail farming countries in the world (Pi, 2007, Zhang et al., 2012, Lukanov, 2019). Hatchability is one of the most important indexes in poultry industry, and thus, how to improve the hatchability performance of hatching eggs in the quail farming industry has drawn a worldwide interest.

Eggshell is a critical factor that influence hatching performance of hatching eggs in modern commercial incubation (King'Ori, 2011). The avian eggshell is a highly ordered structure with several layers (mammillae, palisades, vertical crystal layer, and cuticle) that provide protection for the embryo from mechanical damage, microbial invasions, and solar radiation and regulate water, gas, and heat exchange with the environment during embryonic development. The cuticle, the outmost protective layer of the shell, contributes greatly to the eggshell's multifunctionality (D'Alba et al., 2017). The cuticle is deposited during the final hr of egg formation and forms a plug blocking the external openings of the gaseous exchange pores that extend down through the shell thickness (Wilson et al., 2017, Kulshreshtha et al., 2018). It mainly consists of hydroxyapatite crystals, glycoprotein, polysaccharides, lipids, and pigment (Kusuda et al., 2011, Fecheyr-Lippens et al., 2015), and many of the proteins have been proven to be antibacterial (e.g., C-type lysozyme, ovotransferrin, and ovocalyxin-32) (Wellman-Labadie et al., 2008, Rose-Martel et al., 2012).

The eggshell cuticle may modulate eggshell conductance and then affect embryo development. Eggshell conductance is described as the basic biological functions of the eggshell that provide an incubation environment and allow for essential movement of water vapor and respiratory gases (Ar et al., 1974). Furthermore, avian egg embryonic growth and hatchability have been clearly shown to be dependent on the conductance of the eggshell to water vapor and vital gases (Burton and Tullett, 1983). Structures, morphologies, quantity, and functions of the cuticle varies greatly between species (Kusuda et al., 2011, D'Alba et al., 2017, Chen et al., 2019). Contributions of the cuticle to eggshell conductance are closely related to the ultrastructure of the cuticle itself, and the cuticle may have different influence on the embryonic development in different species (Christensen and Bagley, 1984, Deeming, 1987, Peebles et al., 1987). A thicker cuticle could affect the conductance of hatching eggs and hinder embryo development in artificial incubation conditions. Different from domestic chicken eggs, domestic duck, goose, and turkey eggs embody relative thick and even cuticle layer, and the conductance increased after cuticle removal (Christensen and Bagley, 1984, Deeming, 1987, Chen et al., 2019). Especially, the cuticle removal of hatching eggs to improve hatching performance is a common commercial practice in duck production (Deeming, 2006, Boerjan, 2013). The quail also naturally possesses a relatively thick and dense cuticle layer (Kusuda et al., 2011, D'Alba et al., 2017, Chen et al., 2019); cuticle removal may be a practical method to promote the embryonic development and hatchability in quail hatching eggs.

Sanitation program is critical to achieve a high level of hatchability in poultry production; however, chemicals used in egg washing for sanitation and cuticle removal are mostly chlorine or EDTA based. These are considered harmful to hatching eggs, the environment, and human beings (Northcutt et al., 2005, Pouvreau and Baudon, 2016, Zhang et al., 2017). There is a worldwide interest in developing alternative egg washing chemicals to minimize the environmental and public health impacts. Ascorbic acid was reported to remove the cuticle of broiler breeder eggs effectively, but this treatment is expensive and therefore unlikely to be adopted by the industry (Shafey, 2002). Acetic acid (AA) and citric acid (CA) are also weak acids that are readily available, but their sterilizing and cuticle removal effects have not yet been demonstrated.

The Shendan-1 quail (Coturnix coturnix japonica) is a Chinese commercial laying breed with excellent production performance. In this study, we used and compared two AA types (commercial vinegar [V] and industrial AA)] with an industrial CA treatment and a chlorine-based method to remove the cuticle of the Shendan-1 quail to investigate the hypothesis that cuticle removal could improve the hatching performance. The effectiveness of these treatments on the surface microbial contamination at different incubation stages was also investigated.

Materials and methods

Ethics Statement

All of the experimental procedures were conducted in accordance with the Guidelines for Experimental Animals established by the Animal Care and Use Committee of China Agricultural University (permit number: AW22119102-1-1).

Egg Collection and Treatments

More than 50,000 fresh hatching eggs produced in the same day by 81-day-old Shendan-1 commercial quail breeder flocks were collected. The flocks were maintained in the Quail Breeding Farm of Hubei Shendan Healthy Food Co., Ltd., China and kept under the same environmental and management conditions. The quail were housed in different battery cages with 22 quails (4 male:18 female) per 0.32 m2 and a photoperiod of 16L:8D. A breeder diet (2,860 kcal of ME/kg and 21% CP) and water were provided ad libitum. Eggs were stored at 16°C (65% RH) for 1 D. During the storage, eggs were sorted by cleanliness, egg weight, egg shape, and egg color, and abnormal (dirty, cracked, broken, misshapen, excessively small or large, and white and light brown) eggs were discarded in this study.

Cuticle removal was performed by egg washing employing 1) AA (20 mL AA/L [AA2] or 40 mL AA/L [AA4]); 2) V (commercial aged vinegar [Shanxi, China], containing 4.5% AA and a few other ingredients [Yuan and Yang, 2009]) (444 mL V/L [V2] or 888 mL V/L [V4]); or 3) CA (20 g CA/L [CA2] or 40 g CA/L [CA4]). The control treatments used were as follows: 1) unwashed control, nondipped (CND); 2) washed control, water dipped (CWD); and 3) standard control, 0.13% sodium hyperchlorite (CSH), which is used in previous studies or the industry for cuticle removal (Peebles and Brake, 1986).

All solutions were freshly prepared using clean water. Microbiological activity of the clean water met the Chinese national standards for drinking water quality (GB 5749-2006 released by the Standardization Administration of the People's Republic of China), that is the total number of colonies and Escherichia coli were lower than 10,000 and 1 CFUs/100 mL, respectively. A large plastic bucket was used for egg dipping, and eggs from each treatment were dipped for up to 8 min at a temperature of 25°C. After treatment, the eggs were rinsed with clean water, allowed to dry, and then stored at 16°C (65% RH).

Egg Distribution and Management

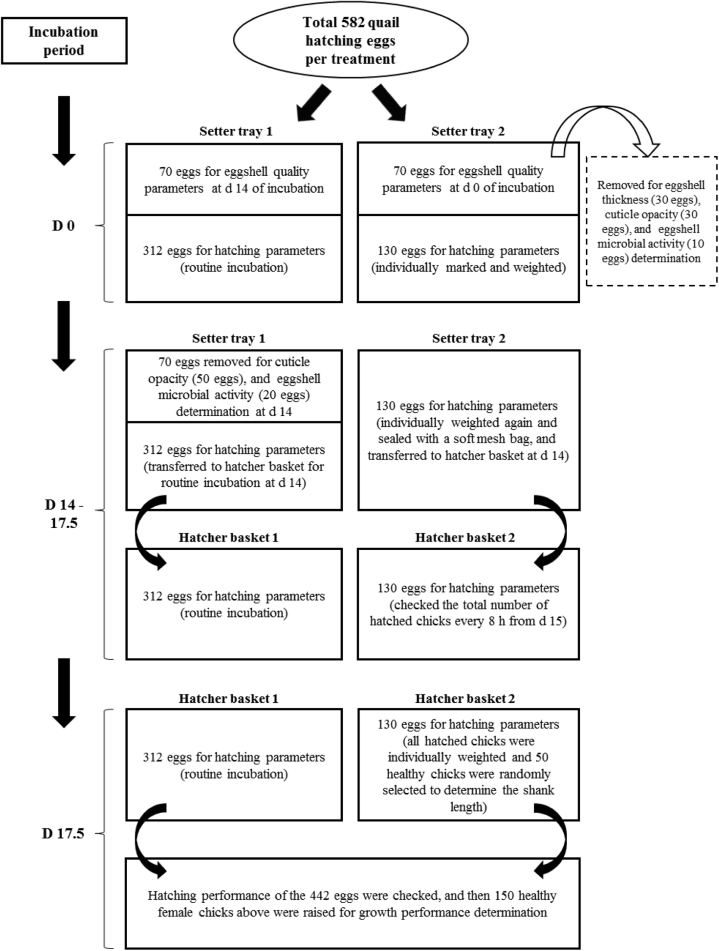

A total of 5,238 eggs were equally distributed to the 9 treatments. Egg distribution and management during incubation period are shown in Figure 1. In detail, 2 setter trays were used to set the eggs for each treatment, that is 312 eggs for hatching parameters (routine incubation) and 70 eggs for eggshell quality parameters were set in the same tray, and 130 eggs for hatching parameters (as a sample during incubation) and 70 eggs for eggshell quality parameters were set in the same tray. All trays were set in the same trolley for incubation. At day 14 of incubation, apart from eggs removed for eggshell quality parameters measurement, the 312 and 130 eggs for hatching parameters were individually transferred to different hatcher baskets. Two trolleys were used to set all baskets, that is the 312 and 130 eggs were distributed to different trolleys. All trays or baskets used prevously were randomly set closely to each other in the central position of the trolleys and set in the center of a large incubator (capacity 99,008 eggs, Liannong-19200; EI Electronic Technology Co., Ltd., Bengbu, China), which was filled to capacity with other quail hatching eggs. There was no replicate tray or basket during the incubation period.

Figure 1.

Egg distribution and management during incubation period.

Incubation Management

After storage for 24 h after treatment, the eggs used for incubation were prewarmed for 6 h at 25°C and 60% RH and then loaded into the incubator at the same time recorded as day 0 of incubation. The temperature and RH settings of the incubator during incubation are shown in Table 1, and the eggs were turned 90° every 2 h until they were transferred to the same incubator on day 14 of incubation to complete the hatching process till day 17.5. The temperature, humidity, oxygen and carbon dioxide concentration, and other factors were controlled and monitored by the fully automatic incubator. Cleaning and disinfection procedures for the incubator followed the company's guidelines.

Table 1.

The temperature and RH setting of an incubator during incubation.

| Incubation period (D) | Temperature (°C) | RH (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 0–1 | 38.2 ± 0.1 | 56 ± 2 |

| 2–3 | 38 ± 0.1 | 58 ± 2 |

| 4–6 | 37.8 ± 0.1 | 60 ± 2 |

| 7–9 | 37.6 ± 0.1 | 62 ± 2 |

| 10–11 | 37.4 ± 0.1 | 64 ± 2 |

| 12 | 37.4 ± 0.1 | 64 ± 2 |

| 13 | 37.2 ± 0.1 | 66 ± 2 |

| 14 | 37.2 ± 0.1 | 68 ± 2 |

| After 14 | 37 ± 0.1 | 72 ± 2 |

Eggshell Quality Parameters

Eggshell Thickness Measurement

At day 0 of incubation, 30 eggs of each treatment were collected, and their eggshell thickness was measured at the large end, equator, and small end without eggshell membrane by using a digital-display micrometer gauge (Mitutoyo, Kawasaki, Japan). The eggshell thickness were determined by the mean of the 3 points.

Cuticle Quality Assessment

An additional sample of 30 and 50 eggs per treatment were taken for eggshell cuticle quality measure on day 0 and 14 of incubation, respectively. The sample of eggs at 14 D were removed from the incubator, assessed for cuticle, and then checked to determine if they contained developing embryos. Any nonfertile or dead-in-shell eggs were discarded and not included in our analysis (n = 30 per treatment). The cuticle quality measure was conducted as per the staining method proposed by Chen et al. (2018). Briefly, the cuticle quality (α value) was evaluated based on differences in cuticle staining before and after staining with MST cuticle blue using a spectrophotometer (CM-2600d; Konica Minolta, Japan) with the XYZ color space system. A high α value corresponds to more cuticle deposition, that is good cuticle quality. Each egg was measured at 3 points: the large end, equator, and small end. Cuticle quality per egg was determined from the mean value of these points. The opacity of cuticle was calculated by the formulas presented in equations (1), (2), (3), (4), (5), (6), (7)

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

| (7) |

In the XYZ model, Y is luminance, Z is quasi-equal to blue stimulation, and X is a mix (a linear combination) of cone response curves. XYZ color space can be converted into RGB color space by the formulas aforementioned, where red (R), green (G), and blue (B) light are added together in various ways to reproduce a broad array of colors. α is the cuticle opacity, subscript “a” indicates egg values after staining, “b” indicates prestaining values, and “d” indicates values for the cuticle blue dye.

Eggshell Microbiological Analyses

A total of 10 and 20 eggs per treatment were collected for microbiological analysis at day 0 and 14 of incubation, respectively. Eggs were immediately removed from the incubator and placed in a sterile glass bottle containing 25 mL of sterile physiological (0.9% NaCl) saline. A whole-egg washing method with a vortex was used to recover eggshell surface bacteria. Serial dilutions of the saline wash after treatment were made and then inoculated onto sterile plate count agar medium (10 g tryptone, 5 g yeast extract, 10 g sodium chloride, and 15 g agar/L) for 24 h at 37.5 ± 1°C. Colonies were measured as CFUs/egg. Further sample of eggs were tested at day 14. Consistent to the measurement results of the cuticle, only results of eggs with normal developing embryos on day 14 of incubation were retained for statistics (n = 10 per treatment).

Hatching Parameters

The 130 eggs as a sample for hatching parameters were individually marked on the shell surface using a permanent marker pen and weighted with a precision electronic balance (0.1 mg) before incubation (day 0). At day 14 of incubation, they were removed to a warm room (37.5°C, 60% RH) adjacent to an incubator, individually weighed again, sealed in a soft mesh bag, and transferred to hatcher baskets within 3 h, then returned to the incubator. From day 15, these eggs were monitored every 8 h to day 17.5 to determine the precise time of hatching. At each examination period, the number of hatched chicks were counted by moving the eggs into a warm room for 15 to 25 min and then returned to the incubator. After the last hatch examination (day 17.5), all chicks were removed from the bag, identified by the marked eggshell, and weighed (i.e., day-old chick weight) one by one in the warm room within 5 h. At this time, 50 healthy chicks from each treatment were selected at random to determine the length of the left shank. This was determined with a digital caliper (0.01 mm). Chick yield was expressed as the percentage of day-old chick weight to initial egg weight at day 0. Egg weight loss was calculated by egg weight determined at 2 incubation stages and expressed as the percentage to initial egg weight. Only eggs with normal developing embryos were calculated for percentage of egg weight loss. Percentage of hatched chicks during hatch time was expressed as the percentage of the number of hatched chicks in every 8-h interval during hatch time to the number of fertile eggs.

Four hundred forty-two eggs (i.e., the 312 eggs and 130 eggs) from each treatment were used for hatching performance assessment. At hatch on day 17.5 of incubation, all quail chicks and unhatched eggs were removed from the incubator, and their number were counted. Every chick was feather sexed and classified as healthy or cull chick. A healthy chick (saleable) was defined as being robust, clean, dry, and free from deformities (normal conformation of body), completely sealed navel, and no yolk sac or residual membrane protruding from the navel area (Tona et al., 2003). Unhatched eggs were opened and examined. Infertile eggs and embryonic deaths were classified by developmental traits as early, middle, and late embryo mortality (to day 7, between day 8 and 13, and from day 14 of incubation, respectively) (Ainsworth et al., 2010). For purposes of statistical analysis, final stage dead or pipped but not out of shell embryos were classified as late embryonic mortality. These data were used to calculate 1) fertility, that is the percentage of fertile eggs to total set eggs; 2) hatchability, that is the percentage of hatched chicks to total fertile eggs; 3) percentage of female chicks, that is the percentage of female chicks to hatched chicks; 4) percentage of healthy chicks, that is the percentage of healthy chicks quality to total hatched chicks; and 5) embryo mortality, that is the percentages of early, middle, and late embryo mortality to total fertile eggs. Unexpectedly broken eggs during incubation were taken into account when performing calculations based on total eggs incubated. Then, chick quality is comprehensively evaluated using parameters that is percentage of female chicks, percentage of healthy chicks, day-old chick weight, day-old chick shank length, and chick yield.

A total of 1,350 (150 per treatment) healthy female day-old quail chicks were subsequently transported to a farm near the incubation room where their livability and live weight during the brooding and rearing period (the first 21 D) were recorded. Chicks were raised (10 pens/treatment) in different pens with 15 chicks per 0.13 m2. During the 21 D of growth, a grower diet (3,000 kcal of ME/kg and 24% CP) and water were provided ad libitum. The room temperature was set at 37°C in the first 3 D, and the temperature decreased by 2°C every 3 D. The photoperiod was 24L:0D in the first 3 D, and the light time decreased by 2 h every 3 D. At the end of the 21-D period, all chicks were individually weighed with a precision electronic balance (0.01 g). Female chick livability was calculated as the percentage of chicks meeting the breed standard (live weight ≥ 70 g) at day 21.

Statistical Analysis

Differences in fertility, hatchability, percentage of female chicks, percentage of healthy chicks, embryo mortality, percentage of hatched chicks during hatch time, and chick livability between treatments were evaluated by the chi-square test or Fisher's exact test, as appropriate. The chi-square test or Fisher's exact test parameters that is df and Chi-Square value (α = 0.05) were 1 and 3.82, respectively. Cuticle quality (α value), bacterial activity (log CFUs/egg), eggshell thickness (μm), initial egg weight (g), egg weight loss (%), day-old chick weight (g), chick yield (%), day-old chick shank length (mm), and live weight at 21 D (g) were analyzed via one-way ANOVA. Statistically significant differences among treatments were determined by the least significant difference test. The phenotypic correlation between the initial egg weight, egg weight loss, day-old chick weight, chick yield, and shank length was estimated by Pearson's correlation coefficients in total. All statistical analyses were performed with the statistical software RStudio (version 3.6.0) (Grolemund and Wickham, 2017), and figures were plotted in Microsoft Excel 2016. The results of basic descriptive statistics are shown in tables using the mean and SD (mean ± SD).

Results and discussion

Eggshell Thickness and Cuticle Opacity

To evaluate the effects of different solutions on cuticle removal in quail eggs, eggshell thickness and cuticle opacity were determined at day 0 of incubation (Table 2). Calcified eggshell and cuticle mainly with glycoprotein are easily dissolved in acid solution, resulting in the decrease of eggshell thickness and cuticle quality. Supplementary Figure 1 demonstrates the effect of each treatment on the appearance of each group of eggs. The AA, V, and CA solutions removed the cuticle compared with 3 control treatments. Previous studies suggest that the cuticle comprises 5 to 10% of the total eggshell thickness in quail (Kusuda et al., 2011, D'Alba et al., 2017), and the eggshell thickness decreased by 5 to 12% with the concentration of AA, V, and CA increased, and eggshell cuticle quality decreased largely in all acid-dipping treatments (P < 0.05). The evidence presented in Table 2 suggests that the AA2, V2, and CA2 treatments were effective at removing the cuticle than the CSH treatment, but when used at the higher concentration (AA4, V4, and CA4), shell thickness was significantly decreased (P < 0.05).

Table 2.

Eggshell thickness, cuticle opacity, and microbiological activity of different treatments.

| Treatment1 | Eggshell thickness (μm) | Cuticle opacity (%) |

Microbial flora (log CFUs/egg) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| day 0 | day 14 | day 0 | day 14 | ||

| CND | 184.6 ± 16.8a,b | 61.59 ± 10.74a,A | 31.37 ± 9.20a,B | 4.30 ± 0.47a,B | 7.81 ± 0.14a,A |

| CWD | 182.0 ± 16.3a,b | 54.26 ± 8.73b,A | 30.17 ± 9.61a,B | 4.36 ± 0.51a,B | 7.67 ± 0.15a,A |

| CSH | 185.4 ± 15.9a | 45.27 ± 11.53c,A | 25.42 ± 10.16b,B | 2.58 ± 1.50b,B | 7.78 ± 0.11a,A |

| AA2 | 174.7 ± 11.1a,b,c | 2.20 ± 1.90d | 1.55 ± 1.78c | 1.07 ± 1.39c,B | 7.89 ± 0.15a,A |

| AA4 | 165.6 ± 14.2c | 2.38 ± 1.18d,A | 1.18 ± 1.22c,B | 0.00 ± 0.00c,B | 1.54 ± 2.16b,A |

| V2 | 175.3 ± 14.1a,b,c | 2.60 ± 1.36d,A | 1.60 ± 1.51c,B | 0.48 ± 1.01c | 1.07 ± 1.48b |

| V4 | 166.2 ± 12.9c | 2.08 ± 1.49d | 1.72 ± 1.50c | 0.48 ± 1.01c | 0.53 ± 1.21b |

| CA2 | 170.7 ± 15.5b,c | 2.94 ± 1.65d,A | 1.72 ± 1.34c,B | 0.56 ± 1.19c | 1.61 ± 1.48b |

| CA4 | 162.9 ± 12.2c | 2.6 ± 1.12d | 1.93 ± 2.12c | 0.51 ± 1.08c | 0.00 ± 0.00b |

a–dMeans within a column that do not share a common superscript differ significantly (P < 0.05).

A,BMeans within a row of the same trait that do not share a common superscript differ significantly (P < 0.05).

Abbreviations: AA2, 2% acetic acid; AA4, 4% acetic acid; CA2, 2% citric acid; CA4, 4% citric acid; CND, unwashed control, nondipped; CSH, standard control, 0.13% sodium hypochlorite; CWD, water control, water dipped; V2, 44.4% vinegar; V4, 88.8% vinegar.

Shendan-1 quail eggs used in this study possessed a better-quality cuticle layer compared with that presented in a previous study (Chen et al., 2019). At day 14, cuticle quality in both the CND and CWD groups had significantly decreased by approximately 50%. A similar pattern was observed for the CSH group. As the cuticle was almost completely removed using the AA, V and CA, the data from these treatments are of lesser interest. The decrease of cuticle quality may be mainly owing to oxidation and decomposition, suggesting antibacterial effect of the cuticle may also decrease during incubation.

Microbiological Activity

Application of different solutions significantly (P < 0.05) affected total surface flora of hatching eggs at day 0 of incubation (Table 2). The eggshell surfaces initially contained 4.30 log CFUs microbial flora per egg in CND treatment. The total surface flora at day 0 of incubation significantly decreased (P < 0.05) about 3–4 log CFUs/egg within the treatment of AA, V, and CA compared with CND, CWD, and CSH treatments, showing the remarkable sterilizing effectiveness of the AA, V, and CA solutions. Egg microbial contamination occurs most frequently after oviposition, and there are large microbial populations present on the eggshell surface and Salmonella, Escherichia, Pseudomonas, Staphylococcus, and mold-yeast are the typical contaminants (Aygun et al., 2012). Many chemical sanitizers using dipping method have been demonstrated to be effective in reducing the microbial load on the eggshell surface (Scott and Swetnam, 1993a); the results of total surface flora at day 0 of incubation also agreed with previous studies that sodium hypochlorite, AA, V, and CA solutions were proved to be broadly effective disinfectants, and their antimicrobial activities on various pathogens has been well confirmed (Rutala and Weber, 1997, Entani et al., 1998, Mcdonnell, 2007, Cortesia et al., 2014). Acetic acid (the active component of V) and CA are both weak organic acids, and their antimicrobial activity can be classified into the bacteriostatic and bactericidal action, though the mechanistic reasons are not fully understood. The antimicrobial activity of weak organic acids toward bacteria is not just because of their acidity of lowering pH (Roe et al., 1998, Hirshfield et al., 2003, Warnecke and Gill, 2005). Because of the hydrophobic structure and the equilibrium between their ionized and nonionized forms, weak acids such as AA and CA can pass easily through the phospholipid bilayer of the bacterial membrane (Salmond et al., 1984, Walter and Gutknecht, 1984), collapsing the proton gradients that are necessary for ATP synthesis, acidifying the cytoplasm, and damaging cellular protein, membrane, and DNA (Hirshfield et al., 2003, Lund et al., 2014).

Total surface flora at day 14 of incubation of CND, CWD, CSH, AA2, and AA4 treatments significantly increased (P < 0.05) during the incubation period, and total surface flora change during the incubation period in V2, V4, CA2, and CA4 treatments were not significant (Table 2). Furthermore, microbial activity in acid-dipping treatments significantly decreased than 3 controlled treatments over the incubation period except AA2 treatment (P < 0.05). The ideal environment for the embryo development is the same needed for microorganism multiplication (Shahein and Khalifa, 2014); the increase of the total surface flora was consistent with previous study that the microbial activity on the shell surface would increase during incubation period for eggs without any treatment as in CND or CWD treatment (Aygun et al., 2012). Different weak acids and concentrations can have very different antimicrobial effects on bacteria (Salmond et al., 1984, Roe et al., 1998, Hirshfield et al., 2003). It was noted that treating with 2% AA or 0.13% sodium hypochlorite for 8 min could not effectively disinfect microorganisms that occurred on eggshell as residual microorganisms on shell surface would multiply during incubation. Sanitation is essential in successful hatching egg production, effective sanitizing of hatching eggs can diminish the microbial load on the shell surface and then increase hatchability and ensure the production of high quality chicks (Sacco et al., 1989, Cox et al., 1994, Shahein and Khalifa, 2014).

Egg Weight and Egg Weight Loss

In this study, initial egg weight at day 0 of incubation in all treatments has no statistical difference (Table 3). Egg weight loss of successful hatch was calculated for that it is an important parameter for incubation and closely correlated with embryonic development and eggshell conductance (Burton and Tullett, 1983). The conductance is an accurate measure of the eggshell's functional ability to regulate water vapor and gas passage (Paganelli et al., 1978; Burton and Tullett, 1983). Furthermore, the loss of mass in eggs during incubation was mainly due to loss of water (Amos and Rahn, 1980). The results of egg weight loss during the incubation of day 0 to 14 of embryonic development are given in Table 3. The egg weight losses of all dipping treatments were lower by 10.62 to 27.90% compared with those of the CND treatments, implying that the eggshell conductance to water vapor was lowered. It was reviewed that chemical exposure could alter the cuticle and result in both negative and positive changes in the eggshell conductance, any alteration or removal of the cuticle by sanitizers may have a significant impact on egg weight loss and hatchability (Brake and Sheldon, 1990, Scott et al., 1993). Apart from the difference in egg washing reagents, this may owing to the ultrastructural difference of the cuticle itself in intraspecies or interspecies. The cuticle as a barrier to liquid penetration has been demonstrated, and the glycoprotein spheres of the cuticle plays an important part in the liquid resistance of the eggshells (Board and Halls, 1973, Board, 1982). Quail eggshell cuticle embodies abundant glycoprotein and dense pigment (D'Alba et al., 2017), which may have an interaction with SH, AA, and CA in the dipping solution and then dissolve or/and denature to form a viscous less permeable substance that blocked the eggshell pores. The lowered egg weight loss may therefore be explained by restriction of water vapor diffusion through these blocked pores after dipping treatment. Moreover, significant differences (P < 0.05) in egg weight loss among acid-dipping treatments were detected. Egg weight losses in AA2, V2, and CA2 treatments (average 7.52%) were all lower than those in AA4, V4, and CA4 treatments (average 8.61%), suggesting that higher concentration of AA and CA solutions can remove the cuticle more effectively with less blockage of eggshell pores.

Table 3.

Effects of cuticle removal on initial egg weight, egg weight loss, day-old chick weight, day-old chick weight/initial egg weight, and day-old chick shank length of quail hatching eggs.

| Treatment1 | Initial egg weight (g) | Egg weight loss2 (%) | Day-old chick weight (g) | Chick yield (%) | Day-old chick shank length (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CND | 10.63 ± 0.51 | 10.36 ± 4.26a | 6.93 ± 0.52b | 65.19 ± 3.61c | 16.22 ± 0.59a,b |

| CWD | 10.78 ± 0.54 | 9.26 ± 2.74a,b | 7.14 ± 0.47a,b | 66.21 ± 2.42a,b,c | 16.04 ± 0.77b,c |

| CSH | 10.71 ± 0.51 | 9.25 ± 2.31a,b | 7.01 ± 0.57a,b | 65.49 ± 3.96b,c | 16.01 ± 0.76b,c |

| AA2 | 10.80 ± 0.54 | 7.48 ± 2.05d | 7.25 ± 0.61a | 67.08 ± 3.43a,b | 16.21 ± 0.79a,b |

| AA4 | 10.61 ± 0.51 | 8.31 ± 1.46b,c,d | 7.05 ± 0.39a,b | 66.49 ± 2.15a,b,c | 16.29 ± 0.61a,b |

| V2 | 10.84 ± 0.52 | 7.62 ± 1.57c,d | 7.25 ± 0.46a | 66.91 ± 2.57a,b,c | 16.19 ± 0.59a,b |

| V4 | 10.72 ± 0.47 | 8.76 ± 1.59b,c | 7.17 ± 0.43a,b | 66.90 ± 2.44a,b,c | 16.04 ± 0.61b,c |

| CA2 | 10.76 ± 0.59 | 7.47 ± 1.06d | 7.28 ± 0.55a | 67.59 ± 2.80a | 16.54 ± 0.72a |

| CA4 | 10.66 ± 0.57 | 8.75 ± 1.67b,c | 7.15 ± 0.56a,b | 67.05 ± 3.23a,b | 16.59 ± 0.71a |

a–dMeans within a column that do not share a common superscript differ significantly (P < 0.05).

Abbreviations: AA2, 2% acetic acid; AA4, 4% acetic acid; CA2, 2% citric acid; CA4, 4% citric acid; CND, unwashed control, nondipped; CSH, standard control, 0.13% sodium hypochlorite; CWD, water control, water dipped; V2, 44.4% vinegar; V4, 88.8% vinegar.

Egg weight loss at day 14 of incubation as a percentage of initial egg weight.

The rates of egg weight loss significantly varied between 4.13 and 24.55% among all treatments, suggesting that the embryos have strong adaptability to different degrees of water loss. Other researchers have previously demonstrated that avian embryos possess regulatory mechanisms that limit their dependence on environmental variables so that embryos can tolerate different rates of water loss from their eggs during incubation (Hoyt, 1979, Simkiss, 1980, Board, 1982, Davis et al., 1988). Nevertheless in artificial incubation, egg water loss should be optimized as this is essential for successful hatch as too extreme (too low or too high) water loss will highly influence embryonic development and chick quality (Davis and Ackerman, 1987, Davis et al., 1988, Geng and Wang, 1990, Meir and Ar, 2008).

Hatchability and Embryonic Mortality

The cuticle removal's effect on fertility, hatchability, and embryonic mortality are shown in Table 4. The different treatments had no effect on fertility, while had a significant effect on hatchability and embryonic mortality. Overall, the AA4, V4, and CA4 treatments resulted in a higher hatchability (by 1.16 to 4.68%) than that for 3 control treatments, but this was not significant when the comparisons were made with CWD and CSH. Two percent acetic acid, V2, and CA2 treatments resulted in a lower hatchability compared with control treatments. Two percent acetic acid treatment in particular significantly decreased hatchability. The increase in hatchability of AA4-, V4-, and CA4-treated eggs appeared to be large because of lower proportions of late embryonic mortality, as the late embryonic mortality in AA4, V4, and CA4 treatments was significantly reduced when compared with CND treatment. However when compared with the CWD, only CA4 treatment embryo mortality was statistically lower.

Table 4.

Effects of cuticle removal on fertility, hatchability, percentage of female chicks, percentage of healthy chicks, and embryonic mortality of quail hatching eggs.

| Treatment1 | Fertility (%) | Hatchability2 (%) | Percentage of female chicks (%) | Percentage of healthy chicks (%) | Embryonic mortality2 (%) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| To day 7 | day 8 to 13 | From day 14 | |||||

| CND | 92.63 | 90.98b,c | 52.48 | 97.38 | 2.92a,b | 0.27c | 5.84b |

| CWD | 93.46 | 93.00a,b,c | 45.97 | 97.31 | 1.25b | 0.75b,c | 5.00b,c |

| CSH | 95.57 | 92.27a,b,c | 49.72 | 98.60 | 4.12a | 1.03b,c | 2.58c,d |

| AA2 | 93.59 | 79.44d | 53.04 | 98.72 | 1.78a,b | 5.84a | 12.94a |

| AA4 | 92.84 | 95.42a | 52.78 | 98.23 | 1.69a,b | 0.24c | 2.65c,d |

| V2 | 93.10 | 90.37c | 48.09 | 97.54 | 1.48b | 1.48b,c | 6.67b |

| V4 | 93.41 | 94.16a,b | 50.90 | 98.19 | 1.22b | 1.95b | 2.68c,d |

| CA2 | 92.87 | 90.59b,c | 49.18 | 97.81 | 1.73a,b | 2.48b | 5.20b,c |

| CA4 | 93.47 | 95.66a | 51.88 | 97.98 | 1.45b | 1.20b,c | 1.69d |

a–dPercentages within a column that do not share a common superscript differ significantly (P < 0.05).

Abbreviations: AA2, 2% acetic acid; AA4, 4% acetic acid; CA2, 2% citric acid; CA4, 4% citric acid; CND, unwashed control, nondipped; CSH, standard control, 0.13% sodium hypochlorite; CWD, water control, water dipped; V2, 44.4% vinegar; V4, 88.8% vinegar.

The percentage to fertile eggs.

There are few research studies on the effect of cuticle removal on hatchability in quail hatching eggs. In duck production, it is believed that the improvement of hatchability by egg washing for cuticle removal is mainly because of the reduction of microbial infection and the increase of eggshell conductance to respiratory gases and heat (Deeming, 2006, Boerjan, 2013, Liang et al., 2017). The results of microbial activity showed that the solutions used for egg washing could diminish the microbial load on the shell surface and then reduce microbial infections. Decrease of egg weight loss during the incubation period could contribute in increasing hatchability to some extent (Aygun et al., 2012, Shahein and Khalifa, 2014), although results of egg weight loss suggested that the conductance to respiratory gases decreased after acid dipping, but rapid water loss during incubation is disadvantageous for the normal embryonic development (Mcdaniel et al., 1979, Board, 1982, Geng and Wang, 1990). An alternative explanation is that cuticle removal and decreased eggshell thickness by acid-treated hatching eggs may promote the heat exchange between quail embryos and the incubator. Taking account of the embryo's mass heat production in late incubation phase, egg cooling (e.g., spraying eggs with water, increasing ventilation) is essential to remove the excess calories produced by the embryo in artificial incubation (Tong et al., 2013, Pouvreau and Baudon, 2016, Shi, 2017, Zhang et al., 2018). In duck production, cuticle removal by egg washing can improve embryo thermoregulation by increasing the eggshell conductance to heat and can replace traditional egg cooling methods that is tedious and difficult to grasp the timing in industrialized hatchery practice (Deeming, 2006, Liang et al., 2017). Therefore, it was speculated that cuticle removal can be applied to improve embryo thermoregulation and hatchability in quail hatching eggs. In addition, a positive correlation between shell thickness and strength (Bain, 2005, Yan et al., 2014), the decrease of eggshell thickness and strength (because of the absorption of calcium by the embryo) during incubation period likely facilitate the breaking of the eggshell by hatchlings (Castilla et al., 2007), it could be easier for the embryo to pipe out the eggshell during hatching process with the decreased eggshell thickness and strength by cuticle removal.

In our pre-experiment, the acids with 1% concentration could not effectively remove the cuticle, whereasile 5% would overreact with the eggshell and significantly lowered the hatchability. As for the lower hatchability in AA2, V2, and CA2 treatment, it appears that the rate of water loss may have been decreased below the optimum range of water loss required for the growth and survival of the embryo at the late stage of incubation. The lower water loss limits the embryo development and will result in an insufficient air cell that suppresses embryonic lung ventilation (Rahn and Ar, 1980, Metcalfe et al., 1981). The lowest hatchability in AA2 treatment is probably caused by embryo microbial infection as poor cuticle quality, thinner eggshell thickness, and excessive bacterial contamination on the eggshell surface could increase the risk of microbial infection and embryo mortality during incubation (Scott and Swetnam, 1993b, Chen et al., 2019).

Chick Quality

Day-old chick weight has great importance in poultry production for a good start of the chick and for the posthatch production performance. Shendan-1 quail is a commercial laying breed; treatments in this study had no effect on percentage of female chicks (Table 4). A positive correlation (0.84) was observed between initial egg weight and day-old chick weight (Table 5). Chick yield was calculated to correct the egg weight effect on day-old chick weight as chick weight and chick yield are closely related (Jabbar and Ditta, 2017). Chick yield in all acid-dipping treatments slightly increased compared with that of 3 control treatment, but the difference were significant only when comparisons were made between AA2, CA2, CA4, and CND treatment. The increased chick yield could be partly attributed to difference in egg weight loss that there was a negative correlation between egg weight loss and day-old chick weight or chick yield (−0.26 and −0.21, respectively). These results were in agreement with that chick weight was primarily determined by initial egg weight and was secondarily determined by weight loss during incubation (Marks, 1975, Khurshid et al., 2004, Grzegrzka and Gruszczynska, 2019). These results were also supported that decreased egg weight loss during incubation could increase chick weight (Peebles et al., 1987, Shahein and Khalifa, 2014). Before hatching, absorption of the yolk sac into the abdomen of the embryo provides nutrients for the chicks during the first few days of life that the chick weight is a combination of the real chick weight and the remaining yolk residual (Ipek and Sozcu, 2014). Therefore, water that had not evaporated in the egg during incubation will be absorbed together with the yolk sac by the embryo and consequently causing an increase in the day-old weight and chick yield. Furthermore, another reason for the increased day-old chick weight may be the better embryonic development discussed previously for well-developed embryos made better use of nutrients in the egg.

Table 5.

Pearson's correlations of initial egg weight, egg weight loss, day-old chick weight, chick yield, and day-old chick shank length of all treatments.

| Hatching parameter | Initial egg weight (g) | Egg weight loss1 (%) | Day-old chick weight (g) | Chick yield (%) | Day-old chick shank length (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial egg weight(g) | 1 | ||||

| Egg weight loss(%) | −0.19 | 1 | |||

| Day-old chick weight (g) | 0.842 | -0.262 | 1 | ||

| Chick yield (%) | 0.12 | -0.212 | 0.632 | 1 | |

| Day-old chick shank length (mm) | 0.242 | -0.01 | 0.342 | 0.252 | 1 |

Egg weight loss at day 14 of incubation as a percentage of initial egg weight.

P < 0.01.

Shank length is a reliable indicator of body shape and body weight in quail production (Gambo et al., 2014), and it was also measured to further confirm the effect of acid-dipping treatment on quail chick quality. The shank length results showed that there is no significant difference between acid-dipping treatments and CND treatment, confirming that cuticle removal using acid treatment did not have a negative effect on chick development. The Pearson's correlation analysis results showed that the shank length was correlated to initial egg weight, day-old chick weight and chick yield without being affected by egg weight loss. The Pearson's correlations reported here for initial egg weight, day-old chick weight, and shank length (0.84, 0.24, and 0.34, respectively, Table 5) were lower than those reported previously (0.91, 0.57, and 0.58) (Grzegrzka and Gruszczynska, 2019), but this is most likely because of the reduced sample size in this trial.

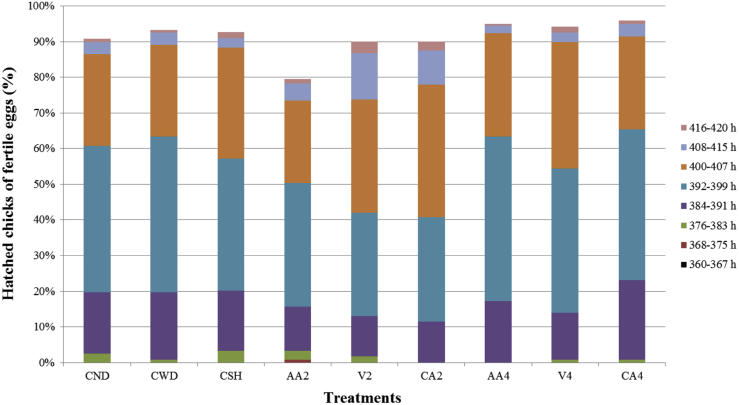

Hatch Time

Hatching began at 384, 384, 384, 376, 392, 384, 384, 392, and 384 h of incubation duration in CWD, CND, CSH, AA2, V2, CA2, AA4, V4, and CA4 treatments, respectively (Figure 2). Hatching ended in all treatments at 420 h of incubation. The peak hatching period was during 384 to 408 h of incubation. Percentages of hatched chicks in AA4, V4, and CA4 treatments (92.40, 89.11, and 90.61%, respectively) during peak hatching period were slightly improved compared with control treatments (84.05, 88.28, and 85.18% for CND, CWD, and CSH, respectively) (P > 0.05), but significant decrease in percentages of hatched chicks in AA2, V2, and CA2 treatments (70.19, 72.13, and 77.96%) during peak hatching period were observed compared with other groups (P < 0.05). The results of hatch time implied that AA4, V4, and CA4 treatments might narrow the speed of hatching, whereas AA2, V2, and CA2 treatments had a longer hatching periods and delayed embryonic development. The hatch time is also affected by water loss (Amos and Rahn, 1980, Jabbar and Ditta, 2017). It has been demonstrated that the low eggshell conductance affects rates of embryonic growth and causes longer incubation periods (Visschedijk, 1968, Burton and Tullett, 1983). Hatch time is a good indicator for chick distribution in the hatcher, and the uniformity of hatch time is important for commercial breeders as there will be homogeneity for chick quality. Extended hatching period will increase the number of chicks that will be remained without food and water and then reduce chick quality and posthatch performance (Wyatt et al., 1985, Noy and Sklan, 1997, Dibner et al., 1998, Careghi et al., 2005, Mahmoud and Edens, 2012).

Figure 2.

Effects of cuticle removal on percentage of hatched chicks during hatch time. Abbreviations: AA2, 2% acetic acid; AA4, 4% acetic acid; CA2, 2% citric acid; CA4, 4% citric acid; CND, unwashed control, nondipped; CSH, standard control, 0.13% sodium hypochlorite; CWD, water control, water dipped; V2, 44.4% vinegar; V4, 88.8% vinegar.

Chick livability and Live Weight at the First 21 D of Life

Although cuticle removal may have no negative effects on hatching performance in quail hatching eggs, chick livability and live weight at the first 21 D of life were recorded to continue verifying the safety of the cuticle removal. The effect of cuticle removal on livability and live weight are shown in Table 6. There were no significant differences between treatments in livability and live weight during brooding period, showing cuticle removal using AA, V, and CA did not have a negative effect on these traits.

Table 6.

Effects of cuticle removal on livability and live weight of quail chicks at the first 21 D.

| Treatment1 | Livability at the first 21 D (%) | Live weight at 21 D (g) |

|---|---|---|

| CND | 94.67 | 79.37 ± 8.91 |

| CWD | 95.33 | 82.23 ± 9.07 |

| CSH | 94.00 | 81.69 ± 9.04 |

| AA2 | 96.00 | 79.5 ± 8.92 |

| AA4 | 95.33 | 82.14 ± 9.06 |

| V2 | 96.67 | 79.71 ± 8.93 |

| V4 | 94.67 | 82.93 ± 9.11 |

| CA2 | 96.00 | 83.81 ± 9.15 |

| CA4 | 95.33 | 82.59 ± 9.09 |

AA2, 2% acetic acid; AA4, 4% acetic acid; CA2, 2% citric acid; CA4, 4% citric acid; CND, unwashed control, nondipped; CSH, standard control, 0.13% sodium hypochlorite; CWD, water control, water dipped; V2, 44.4% vinegar; V4, 88.8% vinegar.

In accordance with the high demand on poultry, quail production is of high economic importance not only in developed countries but also in the developing countries worldwide. The livability is crucial because it is a measure of chick quality and animal welfare. Livability during brooding period in quail production is the key to ensure subsequent production performance and income to quail farms as well as to the hatcheries. In other words, the cuticle removal may increase the hatchability without compromising subsequent production performance.

Conclusions

In conclusion, results of this study demonstrate that the cuticle removal by dipping hatching eggs into 4% AA, 88.8% V, or 4% CA for 8 min could effectively decrease the microbial activity on the eggshell surface during the incubation period and improve hatchability of quail hatching eggs without negative effects on hatch time and performance of quail chicks. For cuticle removal in diverse quail hatching eggs in practice, better egg washing conditions (e.g., washing methods, washing time, temperature, and reagents and their concentrations) and the effects on the production performance of whole production cycle require further exploration.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31672408); the China Agriculture Research Systems (CARS-41); the Special Fund for Agro-scientific Research in the Public Interest (201303084); the Program for Changjiang Scholars and Innovative Research Team in University (IRT 15R62). We would like to thank Hu Bei Shendan healthy food Co., Ltd., China for their supports for this research. We gratefully acknowledge our colleagues on the College of Animal Science and Technology of China Agricultural University for their assistance during the experiment.

Conflict of Interest Statement: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to this work.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at http://doi.org/10.1016/j.psj.2020.04.018.

Supplementary data

References

- Ainsworth S.J., Stanley R.L., Evans D.J.R. Developmental stages of the Japanese quail. J. Anat. 2010;216:3–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2009.01173.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amos A.R., Rahn H. Water in the avian egg overall budget of incubation. Am. Zool. 1980;20:373–384. [Google Scholar]

- Ar A., Paganelli C.V., Reeves R.B., Greene D.G., Rahn H. The avian egg: water vapor conductance, shell thickness, and functional pore area. Condor. 1974;76:153–158. [Google Scholar]

- Aygun A., Sert D., Copur G. Effects of propolis on eggshell microbial activity, hatchability, and chick performance in Japanese quail (Coturnix coturnix japonica) eggs. Poult. Sci. 2012;91:1018–1025. doi: 10.3382/ps.2011-01944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bain M. Recent advances in the assessment of eggshell quality and their future application. World's Poult. Sci. J. 2005;61:268–277. [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner J. Japanese quail production, breeding and genetics. World's Poult. Sci. J. 1994;50:227–235. [Google Scholar]

- Board R.G. Properties of avian egg shells and their adaptive value. Biol. Rev. 1982;57:1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Board R.G., Halls N.A. The cuticle: a barrier to liquid and particle penetration of the shell of the hen's egg. Br. Poult. Sci. 1973;14:69–97. doi: 10.1080/00071667308416040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boerjan M. Overcoming late mortality when hatching Peking duck eggs. 2013. https://www.pasreform.com/en/knowledge/35/overcoming-late- mortality-when-hatching-peking-duck-eggs

- Brake J., Sheldon B.W. Effect of a quaternary ammonium sanitizer for hatching eggs on their contamination, permeability, water loss, and hatchability. Poult. Sci. 1990;69:517–525. doi: 10.3382/ps.0690517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton F.G., Tullett S.G. A comparison of the effects of eggshell porosity on the respiration and growth of domestic fowl, duck and Turkey embryos. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 1983;75:167–174. [Google Scholar]

- Careghi C., Tona K., Onagbesan O., Buyse J., Decuypere E., Bruggeman V. The effects of the spread of hatch and interaction with delayed feed access after hatch on broiler performance until seven days of age. Poult. Sci. 2005;84:1314–1320. doi: 10.1093/ps/84.8.1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castilla A., Herrel A., Díaz G., Francesch A. Developmental stage affects eggshell-breaking strength in two ground-nesting birds: the partridge (Alectoris rufa) and the quail (Coturnix japonica) J. Exp. Zool. 2007;307:471–477. doi: 10.1002/jez.400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Li X., Guo Y., Li W., Jianlou S., Xu G., Yang N., Zheng J. Impact of cuticle quality and eggshell thickness on egg antibacterial efficiency. Poult. Sci. 2018;98:1–9. doi: 10.3382/ps/pey369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Li X., He Z., Hou Z., Xu G., Yang N., Zheng J. Comparative study of eggshell antibacterial effectivity in precocial and altricial birds using Escherichia coli. PLoS One. 2019;14:e220054. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0220054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen V., Bagley R. Vital gas exchange and hatchability of Turkey eggs at high altitude. Poult. Sci. 1984;63:1350–1356. doi: 10.3382/ps.0631350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortesia C., Vilcheze C., Bernut A., Contreras W., Gomez K., de Waard J., Jacobs W., Kremer L., Takiff H. Acetic acid, the active component of vinegar, is an effective tuberculocidal disinfectant. MBio. 2014;5:e13–e14. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00013-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox N.A., Bailey J.S., Berrang M.E., Buhr R.J., Mauldin J.M. Automated Spray sanitizing of broiler hatching eggs 3. Total bacteria and Coliform Recovery after using an egg spraying Machine. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 1994;3:234–237. [Google Scholar]

- D'Alba L., Torres R., Waterhouse G.I.N., Eliason C., Hauber M.E., Shawkey M.D. What does the eggshell cuticle do? A functional comparison of avian eggshell cuticles. Physiol. Biochem. Zool. 2017;90:588–599. doi: 10.1086/693434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis T.A., Ackerman R.A. Effects of increased water loss on growth and water content of the chick embryo. J. Exp. Zool. 1987;1:357–364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis T.A., Shen S.S., Ackerman R.A. Embryonic osmoregulation: Consequences of high and low water loss during incubation of the chicken egg. J. Exp. Zool. 1988;245:144–156. doi: 10.1002/jez.1402450205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deeming C.D. Effect of cuticle removal on the water vapour conductance of egg shells of several species of domestic bird. Br. Poult. Sci. 1987;28:231–237. [Google Scholar]

- Deeming C.D. Cherry Valley improves incubation of Pekin duck eggs. World Poult. 2006;22:18–19. [Google Scholar]

- Dibner J.J., Knight C.D., Kitchell M.L., Atwell C.A., Downs A.C., Ivey F.J. Early feeding and development of the immune system in neonatal poultry. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 1998;7:425–436. [Google Scholar]

- Entani E., Asai M., Tsujihata S., Tsukamoto Y., Ohta M. Antibacterial action of vinegar against Food-Borne pathogenic bacteria including escherichia coliO157:h7. J. Food Protect. 1998;61:953–959. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-61.8.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fecheyr-Lippens D.C., Igic B., D'Alba L., Hanley D., Verdes A., Holford M., Waterhouse G.I.N., Grim T., Hauber M.E., Shawkey M.D. The cuticle modulates ultraviolet reflectance of avian eggshells. Biol. Open. 2015;4:753–759. doi: 10.1242/bio.012211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gambo D., Ojoh Momoh M., Dim N., Kosshak A.S. Body parameters and prediction of body weight from linear body measurements in Coturnix quail. Livest. Res. Rural Dev. 2014;26:98–110. [Google Scholar]

- Geng Z.Y., Wang X.L. Relationship of hatchability and the percentage of egg weight loss and shell pore concentration during incubation. Chin. J. Anim. Sci. 1990;26:12–14. [Google Scholar]

- Grolemund G., Wickham H. R for data science. 2017. https://r4ds.had.co.nz/ Accessed March 2020.

- Grzegrzka B., Gruszczynska J. Correlations between egg weight, early embryonic development, and some hatching characteristics of Japanese quail (Coturnix japonica) Turk. J. Vet. Anim. Sci. 2019;43:253–258. [Google Scholar]

- Hamm D., Ang C.Y.W. Nutrient Composition of quail meat from three Sources. J. Food Sci. 2010;47:1613–1614. [Google Scholar]

- Hirshfield I., Terzulli S., O'Byrne C. Weak organic acids: a panoply of effects on bacteria. Sci. Prog. 2003;86:245–269. doi: 10.3184/003685003783238626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyt D.F. Osmoregulation by avian embryos: the allantois functions like a toad's bladder. Physiol. Zool. 1979;52:354–362. [Google Scholar]

- Ipek A., Sozcu A. The effects of broiler breeder age on intestinal development during hatch window, chick quality and first week broiler performance. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 2014;43:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Jabbar A., Ditta A.Y. Effect of floor eggs on hatchability, candling, water loss, chick yield, chick weight and dead in shell. J. World's Poult. Res. 2017;7:154–158. [Google Scholar]

- Khurshid A., Farooq M., Durrani F.R., Sarbiland K., Manzoor A. Hatching performance of Japanese quails. Livest. Res. Rural Dev. 2004;16:24–28. [Google Scholar]

- King'Ori A. Review of the factors that influence egg fertility and hatchabilty in poultry. Int. J. Poult. Sci. 2011;10:483–492. [Google Scholar]

- Kulshreshtha G., Rodrigueznavarro A., Sanchezrodriguez E., Diep T., Hincke M.T. Cuticle and pore plug properties in the table egg. Poult. Sci. 2018;97:1382–1390. doi: 10.3382/ps/pex409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusuda S., Iwasawa A., Doi O., Ohya Y., Yoshizaki N. Diversity of the cuticle layer of avian eggshells. J. Poult. Sci. 2011;48:119–124. [Google Scholar]

- Liang G., Li J., He J., Jiang X. Study on the concentration of egg washing solutions for cuticle removal before incubation in muscovy duck eggs. Chin. Poult. 2017;39:66–67. [Google Scholar]

- Lukanov H. Domestic quail (Coturnix japonica domestica), is there such farm animal? World's Poult. Sci. J. 2019;75:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Lund P., Tramonti A., De Biase D. Coping with low pH: Molecular strategies in neutralophilic bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2014;38:1091–1125. doi: 10.1111/1574-6976.12076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoud K.Z., Edens F.W. Breeder age affects small intestine development of broiler chicks with immediate or delayed access to feed. Br. Poult. Sci. 2012;53:32–41. doi: 10.1080/00071668.2011.652596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks H.L. Relationship of embryonic development to egg weight, hatch weight, and growth in Japanese quail. Poult. Sci. 1975;54:1257–1262. doi: 10.3382/ps.0541257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mcdaniel G.R., Roland D.A., Coleman M.A. The effect of egg shell quality on hatchability and embryonic mortality. Poult. Sci. 1979;58:10–13. [Google Scholar]

- Mcdonnell G.E. ASM Press; Washington, DC: 2007. Antisepsis, Disinfection, and Sterilization: Types, Action and Resistance. [Google Scholar]

- Meir M., Ar A. Changes in eggshell conductance, water loss and hatchability of layer hens with flock age and moulting. Br. Poult. Sci. 2008;49:677–684. doi: 10.1080/00071660802495288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metcalfe J., Mccutcheon I.E., Francisco D.L., Metzenberg A.D.B., Welch J.E. Oxygen availability and growth of the chick embryo. Respir. Physiol. 1981;46:81–88. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(81)90091-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northcutt J.K., Musgrove M.T., Jones D.R. Chemical analyses of commercial shell egg wash water. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 2005;14:289–295. [Google Scholar]

- Noy Y., Sklan D. Posthatch development in poultry. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 1997;6:344–354. [Google Scholar]

- Paganelli C.V., Ackerman R.A., Rahn H. Respiratory Function in Birds, Adult and Embryonic. Int. Congr. Physiol. Sci., 27th. Satell. Symp; Paris, France: 1978. The avian egg: in vivo conductances to oxygen, carbon dioxide, and water vapor in late development; pp. 212–218. [Google Scholar]

- Peebles E.D., Brake J. The role of the cuticle in water vapor conductance by the eggshell of broiler breeders. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1986;65:1034–1039. [Google Scholar]

- Peebles E.D., Brake J., Gildersleeve R.P. Effects of eggshell cuticle removal and incubation humidity on embryonic development and hatchability of broilers. Poult. Sci. 1987;66:834–840. doi: 10.3382/ps.0660834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pi J. Countermeasures for the development of quail production in China. Hubei J. Anim. Vet. Sci. (In Chin.) 2007;2:7–11. [Google Scholar]

- Pouvreau P., Baudon S. Incubation of Pekin ducks by single loading with the cuticle on. Int. Hatch. Pract. 2016;30:21–23. [Google Scholar]

- Rahn H., Ar A. Gas exchange of the avian egg time, structure, and function. Am. Zool. 1980;20:477–484. [Google Scholar]

- Roe A., Mclaggan D., Davidson I., O'Byrne C., Booth I. Perturbation of anion balance during Inhibition of growth of Escherichia coli by weak acids. J. Bacteriol. 1998;180:767–772. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.4.767-772.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose-Martel M., Du J., Hincke M.T. Proteomic analysis provides new insight into the chicken eggshell cuticle. J. Proteomics. 2012;75:2697–2706. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2012.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutala W.A., Weber D.J. Uses of inorganic hypochlorite (bleach) in health-care facilities. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1997;10:597–610. doi: 10.1128/cmr.10.4.597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacco R., Renner P., Nestor K., Saif Y., Dearth R. Effect of hatching egg sanitizers on embryonic survival and hatchability of Turkey eggs from different Lines and on egg shell bacterial populations. Poult. Sci. 1989;68:1179–1184. doi: 10.3382/ps.0681179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmond C., Kroll R., Booth I. The effect of food Preservatives on pH Homeostasis in Escherichia coli. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1984;130:2845–2850. doi: 10.1099/00221287-130-11-2845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott T.A., Swetnam C. Screening sanitizing agents and methods of application for hatching eggs. II. Effectiveness against microorganisms on the egg shell. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 1993;2:12–18. [Google Scholar]

- Scott T.A., Swetnam C. Screening sanitizing agents and methods of application for hatching eggs. ⅰ. Environmental and user friendliness. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 1993;2:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Scott T.A., Swetnam C., Kinsman R. Screening sanitizing agents and methods of application for hatching eggs III. Effect of concentration and exposure time on embryo viability. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 1993;66:295–301. [Google Scholar]

- Shafey T.M. Eggshell conductance, embryonic growth, hatchability and embryonic mortality of broiler breeder eggs dipped into ascorbic acid solution. Br. Poult. Sci. 2002;43:135–140. doi: 10.1080/00071660120109999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahein E., Khalifa E. Role of spraying hatching eggs with natural disinfectants on hatching characteristics and eggshell bacterial counts. Egypt. Poult. Sci. J. 2014;34:211–228. [Google Scholar]

- Shi W. Technical points for improving hatchability of quail. Agric. Technol. Equip. (In Chin.) 2017;332:95–96. [Google Scholar]

- Simkiss K. Eggshell porosity and the water metabolism of the chick embryo. Proc. Zool. Soc. Lond. 1980;192:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Tona K., Bamelis F., Ketelaere B.D., Bruggeman V., Moraes V.M., Buyse J., Onagbesan O., Decuypere E. Effects of egg storage time on spread of hatch, chick quality, and chick juvenile growth. Poult. Sci. 2003;82:736–741. doi: 10.1093/ps/82.5.736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong Q., Romanini C., Exadaktylos V., Bahr C., Berckmans D., Bergoug H., Eterradossi N., Roulston N., Verhelst R., Mcgonnell I., Demmers T. Embryonic development and the physiological factors that coordinate hatching in domestic chickens. Poult. Sci. 2013;92:620–628. doi: 10.3382/ps.2012-02509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tunsaringkarn T., Tungjaroenchai W., Siriwong W. Nutrient benefits of quail (Coturnix coturnix japonica) eggs. Int. J. Sci. Res. Publ. 2013;3:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Visschedijk A. The air space and embryonic respiration. 2. The times of pipping and hatching as influenced by an artificially changed permeability of the shell over the air space. Br. Poult. Sci. 1968;9:185–196. doi: 10.1080/00071666808415708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter A., Gutknecht J. Monocarboxylic acid permeation through lipid Bilayer-Membranes. J. Membr. Biol. 1984;77:255–264. doi: 10.1007/BF01870573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warnecke T., Gill R. Organic acid toxicity, tolerance, and production in Escherichia coli biorefining applications. Microb. Cell. Fact. 2005;4:25–34. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-4-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellman-Labadie O., Picman J., Hincke M.T. Antimicrobial activity of the Anseriform outer eggshell and cuticle. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 2008;149:640–649. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpb.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson P.W., Suther C.S., Bain M.M., Icken W., Jones A., Quinlanpluck F., Olori V., Gautron J., Dunn I.C. Understanding avian egg cuticle formation in the oviduct: a study of its origin and deposition. Biol. Reprod. 2017;97:39–49. doi: 10.1093/biolre/iox070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt C.L., Weaver W.D., Beane W.L. Influence of egg size, eggshell quality, and posthatch holding time on broiler performance. Poult. Sci. 1985;64:2049–2055. [Google Scholar]

- Yan Y., Sun C., Lian L., Zheng J., Xu G., Yang N. Effect of uniformity of eggshell thickness on eggshell quality in chickens. J. Poult. Sci. 2014;51:338–342. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Z., Yang J.Y. Fragrance Ingredient Analysis of Our Brands of Vinegar with LLE-GC/MS. China Condiment. 2009;34:102–105. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G., Chen L., Liu Y., Chen X. Effects of microenvironmental control on improving broiler hatching performance. Chin. Poult. 2018;40:63–65. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R., El-Mashad H. Waste management in egg production. In: Roberts J., Sandilands V., editors. Achieving Sustainable Production of Eggs Volume 2: Animal Welfare and Sustainability. Burleigh Dodds Science Publishing; London, UK: 2017. pp. 357–365. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W., Li S., Du J. The Survey of research about quails in China. Hubei Agric. Sci. (In Chin.) 2012;51:5572–5575. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.