Abstract

Purpose of Review

This review summarizes recent literature linking Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and late life depression (LLD). It describes shared neurobiological features associated with both conditions, as well as factors that may increase resilience to onset and severity of cognitive decline and AD. Finally, we pose a number of future research directions toward improving detection, management, and treatment of both conditions

Recent Findings

Epidemiological studies have consistently shown a significant relationship between LLD and AD, with support for depression as a prodromal feature of AD, a risk factor for AD, and observation of some shared risk factors underlying both disease processes. Three major neurobiological features shared by LLD and AD include neurodegeneration, disruption to cerebrovascular functioning, and increased levels of neuroinflammation. There are also potentially modifiable factors that can increase resilience to AD and LLD, including social support, physical and cognitive engagement, and cognitive reserve.

Summary

We propose that, in the context of depression, neurobiological events, such as neurodegeneration, cerebrovascular disease, and neuroinflammation result in a brain that is more vulnerable to the consequences of the pathophysiological features of AD, lowering the threshold for the onset of the behavioral presentation of AD (i.e., cognitive decline and dementia). We discuss factors that can increase resilience to AD and LLD, including social support, physical and cognitive engagement, and cognitive reserve. We conclude with a discussion of future research directions.

Keywords: depression, dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, late life depression

Introduction

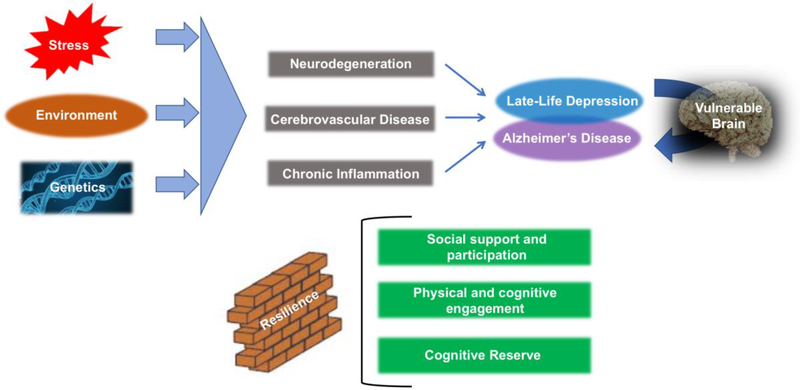

Epidemiological studies have consistently shown a significant relationship between late life depression (LLD) and AD (Alzheimer’s disease), with support for depression as a prodromal feature of AD(1), a risk factor for AD(2), and the presence of shared risk factors underlying both disease processes(3)(4). Examining shared pathophysiology between the two disease processes can provide some indications as to possible biological mechanisms underlying the linkage between LLD and AD. In this review, we will first summarize the epidemiological literature linking AD and late life depression (LLD). We will then focus on three major neurobiological mechanisms that have been associated with both AD and LLD including neurodegenerative processes, cerebrovascular disease, and chronic inflammation. This is not meant to be an exhaustive list, and we refer the reader to a discussion of genetic factors underlying both disease processes, that is beyond the scope of this paper(3) We propose that, in the context of depression, these conditions result in a brain that is vulnerable to the consequences of the pathophysiological features of AD, such as neurofibrillary plaques and tangles, essentially lowering the threshold and increasing susceptibility for the onset of the behavioral presentation of AD (i.e., cognitive decline and dementia). We discuss factors that can increase resilience to the consequences of AD and LLD, including social support, physical and cognitive engagement, and cognitive reserve (see Figure 1). We conclude with a discussion of future research directions.

Figure 1.

Genetics, environment, and stressors give rise to factors that contribute to depression in late life, including neurodegeneration, cerebrovascular disease, and chronic inflammation, all of which can create a brain that is increasingly vulnerable to the risks of development and progression of cognitive decline due to Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Factors associated with resilience, including social support and participation, physical and cognitive engagement, and cognitive reserve, can buffer even vulnerable brains from susceptibility to the behavioral phenotype of AD.

Epidemiology

With a growing and aging population(5) the number of individuals suffering from LLD and AD is on the rise. The global number of individuals who currently suffer from depression exceeds 300 million, which is more than 4% of the total world population (6)A systematic review of 20 studies published between 1985 and 2011 in individuals aged 70 years or older at baseline revealed that the incidence rate of major depressive disorder (MDD) ranges between 0.2 and 14.1 per 100 person-years(7) The global number of people who currently live with dementia equals 50 million, of which roughly 65% are Alzheimer cases(8), while the incidence rate of Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI; thought to represent a preclinical stage of AD for some individuals) has been reported to be between 0.5 and 16.8 per 100 person years(9). Results from the Framingham Heart Study show that the incidence of AD over a period of 5 years in a cohort assessed between 2004 and 2008 was 1.4 per 100 persons(10).

In order to better understand the relationship between LLD and AD, it is necessary to study how often cognitive dysfunction is observed in LLD and in the same vein, how often depression occurs in MCI and AD. Though cognitive disorders are related to LLD, few studies have examined incidence rates of depression in prevalent MCI or AD. A recent meta-analysis revealed that the prevalence of depression or depressive symptoms in community dwelling people with MCI was 25%(11) with higher prevalence in amnestic-MCI (aMCI) relative to non-amnestic MCI. (34% vs 26%). A prospective longitudinal population-based study reported that individuals with MCI were 3.13 times more likely to develop depression during follow up compared to those without MCI(12). Of 775 Korean older adults recruited from hospital clinic sample with AD who completed a 1-year follow-up, 103 (13.29%) developed depression(13)A French study that followed 312 AD patients for 6 years reported an incidence of depressive symptoms of 17.45% per 100 person/years (14), Unfortunately, because of the lack of control groups in these two studies, it is not possible to compare these statistics with those in the general population.

Likewise, depression is a risk factor for developing cognitive disorders. Postmenopausal women aged 65 years and older with a depressive disorder at baseline were 1.98 times more likely to develop MCI(11) than their non-depressed counterparts after a mean follow-up of 5.4 years According to a meta-analysis pooling across 23 studies, individuals with LLD were 1.65 times more likely to develop AD(15). This is consistent with recent data from the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center which showed that after a median follow-up of 27 months, individuals who were depressed within the last two years were 1.44 times more likely to develop AD (pooled odds ratio 1.65) than those without depression(15). Greater depression symptom severity as measured by the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) has also been linked to higher risk of developing AD (hazard ratio 1.11 per 1 unit increase on the GDS total score)(16). These results indicate that LLD is a statistical predictor for AD. Whether LLD is an independent risk factor for AD is a source of some contention in the field, although recent commentaries on the topic lend some support to LLD as a potentially causal predictor (17). The multi-site longitudinal Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) may be able to contribute increased understanding of how AD and MDD are temporally related. While patients with MDD are excluded from enrollment in ADNI, subsyndromal symptoms of depression are not exclusionary, and investigation into mechanisms linking depressive symptoms and AD pathology have already begun(18).

Shared Neurobiological Processes in AD and LLD

Neurodegeneration

Much investigation has taken place over the past decade related to neurodegenerative factors that may link depression and AD. A number of studies have measured atrophy to gray matter regions in both disorders. A recent coordinate-based meta-analysis found that, while both disease are associated with atrophy in bilateral hippocampus, greater atrophy in left anterior hippocampus and bilateral posterior cingulate cortex is observed in AD, while greater atrophy in precuneus, superior frontal gyrus, and ventromedial prefrontal cortex is associated with LLD(19).

Other investigations have sought to understand the role that two hallmark biomarkers for AD – β-amyloid (Aβ) plaques and tau tangles – have in increasing the brain’s vulnerability in LLD(20)(21). Aβ peptides and tau proteins have been central to the proposed development of AD for decades, associated with the accumulation of Aβ plaques and hyper-phosphorylated tau tangles in the brains of those affected by AD. In addition to the role of these biomarkers in AD, several studies(22)(23)(24)(25) have observed alterations in Aβ and tau levels in older adults with clinically classified depression, further supporting inquiry into the association between AD and LLD. The results of such investigations have been equivocal. For example, a large-scale review by Harrington and colleagues(26) examining 19 studies between 2007 and 2014 found similarities between the pattern of Aβ changes observed in older adults with depression and with those in patients with AD. Specifically, a general pattern emerged of decreased Aβ42 levels and increased Aβ40:42 ratio in blood and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), as well as increased amyloid binding on positron emission tomography (PET) scans, consistent with AD(27)(28). Additionally, other studies of patients with MCI have shown that (1) those with sub-syndromal symptoms of depression possess lower levels of CSF Aβ1–42 and diminished global cognition(18), and (2) a lifetime history of depression (LHD), and not current depressive symptoms or vascular risk factors predicts increased Aβ accumulation(29), indicating that having LHD is specifically associated with greater risk of having this brain pathology. Further, hyper-phosphorylated tau tangles have been shown to accumulate in greater numbers in the hippocampus of AD patients with depression than in those without depression(30)(31). A major caveat is that drawing any conclusions about the directionalities of relationship between LHD and AD-related pathology is difficult from these cross-sectional studies alone. Interestingly, in a prospective study of cognitively normal older adults with either high or low Aβ levels based on Aβ PET neuroimaging classification, those in the high Aβ group were 4.5 times more likely to have developed depression at the 2.5-year follow-up, which indicates that having elevated Aβ aggregation in the brain may confer greater risk of developing depression later in life (20).

Conversely, several other recent studies have failed to find such relationships between Aβ/tau and depression. For example, no associations were observed between tau and depression in a systematic review and meta-analysis of 49 studies from 1995 to 2015 using CSF, PET, and clinicopathological analyses(32). Similarly, patients with AD have been shown to possess comparable CSF Aβ levels regardless of a history of neuropsychiatric symptoms(33), and other research found that neither Aβ plaque burden or tau pathology was associated with elevated symptoms of depression(34). Multiple studies examining cortical Aβ aggregation using amyloid-PET in cognitively normal older adults have either not observed a relationship with depressive symptoms or found that the presence of increased depressive symptoms are “unlikely to be a direct consequence of increasing Aβ”(35)(36). Furthermore, some have hypothesized that increased risk of AD in older patients with depression is likely more proximally related to “reduced brain reserve” resulting from brain pathology, rather than a direct consequence of it (29). Finally, a recent study found no differences in CSF AD biomarkers (Aβ42 or tau proteins), or cortical hypometabolism using 18F-flurodeoxyglucose (FDG)-PET, between LLD and healthy controls, whereas AD patients in the same study displayed consistently greater pathology(37). Given the inconsistent nature of these findings, further studies are required to permit definitive conclusions between these biomarkers associated with neurodegenerative disease and LLD. Moreover, the idea of amyloid-associated depression as a prodromal feature of cognitive disorders including AD is worth revisiting and expanding [1,24]. Given the well-known heterogeneity of depression symptom profiles(38) and underlying biology(39), it is certainly possible that equivocal results linking LLD with Amyloid biomarkers may be due to the “diluting” of amyloid-associated LLD with LLD from other etiologies. Further, while this research focus has been on beta-amyloid and tau derived neurodegeneration, less is known about the relationship between LLD and non-amyloid/tau pathologies such as TDP-43 pathology(40) or hippocampal sclerosis(41), which could potentially represent late-life etiologies with stronger associations with LLD (though see Wilson et al(34), which did not show a relationship between AD pathology and hippocampal sclerosis).

Cerebrovascular

Deterioration in cerebrovascular function has been associated with both LLD(42) and dementia(43). Vascular health conditions, such as diabetes, and LLD have been known to be comorbid, with some even suggesting cerebrovascular decline as a key etiological mechanism for developing LLD(44)(45)(42). A meta-analysis revealed that LLD is positively associated with presence of specific cerebrovascular risk factors including diabetes, cerebrovascular diseases, and stroke(46). Research also suggests that there exist disproportionately greater white-matter hyperintensities (WMH) in individuals with LLD, relative to their never-depressed counterparts. When white matter lesions were compared between individuals with LLD and never-depressed comparison subjects with equivalent vascular risk factors, those with LLD had greater white matter hyperintensities (WMH) located in frontal-subcortical regions of the brain that serve a key role in cognition and emotion(47). These suggest that specific vascular risk factors may expose older adults to both LLD and cognitive impairment in the context of AD, depending on the extent and location of the cerebrovascular disease. WMH burden has also been found to be sensitive to clinical response to antidepressant treatment, whereby non-remitters in a 12-week trial had greater extent of WMH than did remitters(48). White-matter integrity as measured by diffusion tensor imaging was also shown to be related to clinical correlates of LLD, such that greater depression severity was correlated with lower white-matter integrity of the bilateral cingulum and right uncinate fasciculus, which were, in turn, negatively associated with learning and memory, and executive function, respectively(49). It also appears that comorbid LLD and aMCI confers a double burden, resulting in disproportionately lower white-matter integrity compared to individuals affected by either LLD or aMCI alone(50).

Moreover, recent studies shed light on the role vascular risk factors play in determining the clinical course of dementia, including AD. In light of multiple phase 3 clinical trials of amyloid clearing agents showing no therapeutic effect on primary outcomes(51)(52)(53)(54), some have suggested that vascular pathology maybe more central to pathophysiology of AD than previously believed(55). In fact, it has been known that cerebrovascular risk factors and vascular health conditions increase risk for AD. For instance, hypertension, diabetes, cerebrovascular diseases, and hypercholesterolemia have been identified as factors that increase the risk of conversion from MCI to AD, and individuals with MCI whose vascular health conditions were treated in totality had lower conversion rate from MCI to AD compared to those who only received partial treatment of their vascular health conditions(56)(57). Having a prior history of cerebrovascular events such as stroke has also been associated with more rapid decline in older adults already diagnosed with AD [21]. Further, higher level of WMH at baseline have been shown to predict worse processing speed(58) and faster clinical decline(59) in MCI.

Recent studies have also lent support to the idea that vascular pathology and amyloid pathology in AD likely interact(60). One such recent study using a mouse model demonstrated that fibrinogen, a type of blood-coagulating protein, when coming in contact with neural cells - as is the case in brain-microbleeds due to vascular damage - can cause microglia-mediated synaptic spine elimination resulting in cognitive decline(61). Previous studies have shown that even among cognitively normal older adults, those with evidence of cortical microbleeds found on MRIs concurrently showed reduced cerebral blood flow across multiple regions of the brain(62). Given the positive association between global brain hypoperfusion and amnestic MCI diagnosis(63)(64) a cascade of events starting from vascular damage-induced cerebral microbleeds, microglia-mediated synaptic elimination along with reduced global cerebral perfusion may be closely linked to the cognitive impairment observed in aMCI and AD.

Neuroinflammation

Microglia-mediated neuroinflammation has also been proposed as a mechanism linking LLD with AD (65)(66). In response to stress or injury, the immune response is activated via microglia, which release cytokines. Acutely, cytokines foster clearance of damaged tissue and resolve infections. However, chronic release can result in reduced synaptic strength, changes in neuronal excitability, recruitment of neurotoxic secondary immune cells, and increased production of age-associated plaques (see Herman et al., 2019 for review(65)). In addition, they disrupt function of glucocorticoid receptors and decrease hippocampal neurotrophic support(67)

A recent meta-analysis of 82 studies, comprising 3212 individuals with Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) and 2798 healthy controls (HC) found that peripheral levels of interleukin-6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha, IL-10, IL-2, C-C chemokine ligand 2, IL-13, IL-18, IL-12, the IL-1 receptor antagonist, and the soluble TNF receptor 2 were higher in individuals with MDD, relative to controls, while interferon-y levels were slightly reduced in patients compared to controls(68). Elevated peripheral cytokines in MDD may reflect an acute defense response against pathogens(69). While peripheral cytokine levels may not reflect CNS activity, studies using rodent models find that obstructing the trafficking of peripheral monocytes to the brain decreases proinflammatory cytokine production and depressive-like behaviors (see Wohleb et al., 2015 for review(70)).

Elevated cytokines have also been found in the CSF (71) and plasma of patients with AD, particularly during pre-clinical and early disease stages. A meta-analysis of 175 studies, including 13,344 patients with AD and 12,912 HC found numerous elevated peripheral cytokine levels in AD relative to controls(72). An increasing amount of evidence suggests that microglia are crucial for neuroprotection and clearance of Aβ, which may explain increased cytokine release during preclinical and early disease stages(71).

There have been a number of in-vivo PET studies using compounds that bind to microglia, such as 11C-(R)PK11195. A seminal study by Su and colleagues (73) found that older adults with MDD had higher 11C-(R)PK11195 binding in regions previously associated with depression, including subgenual anterior cingulate cortex and parahippocampus. A study in AD using the same radiotracer found an 18% reduction in binding over 14 months in those with MCI, with an increase in binding over the same time period in those with AD. They suggest that the early peak in MCI may be reflective of protection, while the later increase during the course of AD may be pro-inflammatory (74). Further evidence for the role of neuroinflammation in LLD and AD comes from clinical trials of drugs such as minocycline, a tetracycline antibiotic with anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective effects(75). A meta-analysis of 18 studies in MDD demonstrated a large effect size for reducing symptoms(76). Minocycline is currently being tested as a disease-modifying agent in clinical trials of AD. In addition to discussing the shared neurobiology of risk for LLD and AD, we feel that it is equally important to highlight shared variables that may enhance resilience to both disease processes, and to comment upon areas that could be near-term priorities for investigation.

Resilience

There is a growing interest in potentially modifiable variables that may decrease the risk of developing AD, and that are also known to be associated with depression onset and/or disease course. Physical activity has well-established, positive effects on mood and cognition(77)(78) through mechanisms such as alterations to neurotransmitter levels (e.g., endorphins, serotonin, dopamine)(79) and improvements to cardiovascular health. A study by Boots and colleagues (77) using cardiorespiratory fitness in a sample of middle-aged participants at risk for developing AD showed that physical activity was negatively correlated with depressive symptoms and cognitive complaints. Interestingly, in a review of the literature by Hendrie and colleagues (80), better lung capacity was found to be a protective factor against cognitive decline in older adults. Physical activity has been identified as a significant modifier of the relationship between depressive symptoms and disability in older adults, particularly those with severe depression and functional disability(81). Researchers found that older adults who were obligated to relinquish activities due to health-related issues reported more depressive symptoms; however, substituting new, acceptable activities for previously valued activities reduced depressive symptoms to levels comparable to healthier counterparts(82)(83).

Cognitive activity(84) and engagement in complex and cognitively-demanding work(85) in older adults has been found to reduce the risk of dementia, while higher education attainment and socioeconomic status are consistent protective factors for cognition and mood in older adults(80). Participation in leisurely (e.g., reading, playing board games or a musical instrument, dancing, etc.)(86)(87), religious and/or spiritual(88), and/or meditative(89) activities in older adulthood has also been shown to reduce the risk of developing depression and dementia. Thus, engagement in enriched activities may directly, or indirectly, contribute to the prevention of cognitive decline and LLD, through the avoidance of comorbid medical conditions and disability.

Social engagement and perceived social support also appear to be protective factors against LLD/mood symptoms(90) and development of dementia(87)(91). As suggested by Berkman and colleagues(92), the demands of social engagement (e.g., communication) might stimulate cognitive capacities in older adults. Furthermore, Zuelsdorff and colleagues(93) found that both social interactions and perceived social support reduced the negative effects of stressful events in older adults. Further, instrumental social support (e.g., material goods, financial support) help toward preventing functional decline in people with LLD. (94). Conversely, low levels of perceived social support has been linked to depression severity(95), and social isolation and loneliness were associated with cognitive decline(96)(97)and dementia/AD(84)(98).

Lastly, cognitive reserve—a theoretical notion that proposes certain life experiences (e.g., educational and occupational attainment, social, cognitive, and physical enrichment) increase the capabilities and efficiency of neural networks, thereby protecting those with higher reserve against clinical impairment or symptoms of a disease, even in the context of neuropathology(99)—may play a role in determining one’s risk of developing or exhibiting symptoms of dementia. For example, research by Okonkwo and colleagues(100) (2014) and Vemuri and colleagues (101) has shown that engagement in both cognitive and physical activities in mid- and late-adulthood strengthens cognitive reserve in older adults, potentially dampening the effects of pathological changes in the brain related to aging and AD. However, researchers continue to consider the most effective ways of measuring reserve and resilience as well as determining the mechanisms through which these factors provide protection from the onset of cognitive impairment. That said, as research progresses in areas of treatment interventions (pharmacological and/or therapeutic) for older adults predisposed to developing AD, modifiable, protective factors that promote healthy brain aging and reduce mood symptoms should continue to be an important focus in the efforts to delay and/or prevent cognitive decline and potential dementia. Importantly, those with LLD are less likely to engage in physical activity(102) and have lower levels of social support(103), suggesting important targets for prevention and treatment.

Future Directions

There are many avenues ripe for exploration in the context of improving diagnostic accuracy in depression and AD, understanding how the two disease processes are related, and perhaps most importantly, prevention and improving management, treatment and overall outcomes. We focus on just a few, though this is certainly not an exhaustive list.

Enhanced Understanding of Neuroendocrine Mechanisms that May Underlie Sex Differences in Prevalence of MDD and AD

Both MDD and AD are at least twice as common among women than among men (104) (105). The role of sex-mediated steroids, including estrogen and testosterone, have been investigated as one mechanism contributing to increased prevalence rates of both disorders in women. While a complete review of this literature is beyond the scope of this paper, the reader is referred to Pike (106) and Ma et al. (107) for more complete discussion. Evidence that sex-specific, age-related decline of estrogen in women and testosterone in men are relevant to the association of age and AD and relationships between onset of both depression and AD during late life is incomplete, and has important implications for delaying or preventing onset of both disease processes during middle- and older-age.

Development of Sensitive and Easy to Use Tools for Detecting Cognitive Decline and Dementia

The large burden of dementia on health care systems(108) calls for early intervention and diagnosis. Contemporary diagnostic protocols include cognitive testing and may involve amyloid imaging. To improve the diagnostic process, inexpensive and sensitive tools that are easy and fast to administer are needed. Psychomotor measures may offer one candidate, given that several studies have already demonstrated the predictive value of motor dysfunction in AD(109)(110)(111) and because many motor tests can be administered within minutes. Future studies might focus on identifying motor behaviors that are most sensitive for predicting AD to aid in the development of a diagnostic motor test battery for AD.

Enhanced Understanding of the Role of Emotion Regulation in MCI and AD

With age, individuals can experience a strengthening of psychological resiliency and improvements in emotion regulation, which protect against depression. When compared to their younger adult counterparts, older adults tend to: (1) focus more on positive, emotionally meaningful experiences(112); (2) experience less emotional reactivity when faced with a challenging task(113); (3) be less reactive to stressors (e.g., interpersonal problems)(114); and (4) similarly engage in cognitive strategies (e.g., positive reappraisal), in turn reducing susceptibility to depressive symptoms(115). Emotion regulation among older adults with MCI, AD, and/or LLD has been poorly studied, however. The National Institutes of Health have recently sought applications for studies of emotion regulation in the context of cognitive decline and LLD. Most studies of cognition in LLD and in MCI have focused on cognitive functioning, and there is very little understanding as to how cognitive decline may impact emotion processing skills, including emotion regulation. Enhanced understanding of emotion regulation in older adults with cognitive impairment and depression would not only increase our knowledge about the linkage between AD and LLD, but will also provide some direction as to the development of effective behavioral interventions for these conditions.

Novel therapies to treat cognitive impairment and emotion dysregulation in MCI and LLD

One relatively under-explored but promising avenue of research overlapping between LLD and cognitive disorders (including AD) involves investigating the novel treatment usage of neuromodulation tools to treat sub-optimal cognitive and emotional functioning in individuals with LLD and/or MCI. Neuromodulatory tools, more specifically Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS) has been utilized as a neurotherapeutic tool in a limited scope. TMS is a non-invasive brain stimulation tool that is currently being clinically used as an FDA-approved treatment for intractable depression(116). While TMS is a very promising tool with divergent potentials, there are challenges to utilizing it with older adults. Aging brains show varying degrees of atrophy, which may change the dosages delivered from the TMS machine to individual’s brain. Thus, it will be important to take into account the individual differences in brain morphology and atrophy, which may be particularly important when using this method in patients with LLD and MCI/AD, known to have greater likelihood of atrophy. Novel uses of TMS are actively being investigated for various psychiatric and neurological conditions. Future studies utilizing neuromodulatory tools such as TMS should capitalize on the benefit of non-invasive brain stimulation and investigate the potential of using this modality as a novel treatment tool that can engage and modulate the neural bases that underlie various cognitive functions and emotional regulation problems observed in LLD and aMCI/AD(117). Pharmacological studies of how treatment for one condition impacts the onset and/or course of the other condition are also needed. Nicotine agonists have been proposed as another novel therapy for enhancing cognition in MCI and LLD. Pilot work has suggested that six months of treatment with transdermal nicotine enhances memory, attention, and processing speed in MCI(118), relative to placebo. An open-label trial of 12-week treatment with transdermal nicotine in LLD suggests that it may also improve apathy, depression symptom severity, rumination, and subjective cognitive performance(119).

Conclusions

AD and LLD share a number of neurobiological processes, including neurodegenerative changes, alterations to cerebrovascular functioning, and high inflammatory cytokine levels. A number of variables are also known to prevent or delay the onset of both conditions, including social support and participation and engagement in physically and cognitively stimulating activities. While there are many avenues for future research, important areas of inquiry include the development of sensitive and clinically-exportable tools for detection of cognitive decline and dementia, enhanced understanding of emotion regulation skills during unhealthy aging, and the development of interventions for enhancing cognition and emotion in LLD and MCI/AD.

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Conflict of Interest

Sara Weisenbach reports grants from National Institutes of Health outside the submitted work. Joseph Kim, Dustin Hammers, Kelly Konopacki and Vincent Koppelmans declare no conflicts of interest relevant to this manuscript.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of a an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:

• Of importance

•• Of major importance

- 1.Kida J, Nemoto K, Ikejima C, Bun S, Kakuma T, Mizukami K, et al. Impact of Depressive Symptoms on Conversion from Mild Cognitive Impairment Subtypes to Alzheimer’s Disease: A Community-Based Longitudinal Study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;51(2):405–15.• A recent community-based longitudinal study of how depression in MCI increases risk for AD.

- 2.Ownby RL, Crocco E, Acevedo A, John V, Loewenstein D. Depression and risk for Alzheimer disease: systematic review, meta-analysis, and metaregression analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(5):530–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ye Q, Bai F, Zhang Z. Shared Genetic Risk Factors for Late-Life Depression and Alzheimer’s Disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016. 08;52(1):1–15.• Meta-analysis of shared genetic risk for AD and LLD.

- 4.Hermida AP, McDonald WM, Steenland K, Levey A. The association between late-life depression, mild cognitive impairment and dementia: is inflammation the missing link? Expert Rev Neurother. 2012;12(11): 1339–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.United Nations, Department of Economics and Social Affairs, Population Division. World population ageing, 2017 highlights. 2017.

- 6.World Health Organization. Depression and Other Common Mental Disorders: Global Health Estimates [Internet]. 2017. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/254610/WHO-MSD-MER-2017.2-eng.pdf;jsessionid=297CF875C1CF9F521218271E3F5C71C7?sequence=1

- 7.Büchtemann D, Luppa M, Bramesfeld A, Riedel-Heller S. Incidence of late-life depression: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2012. December 15;142(1–3):172–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization. Towards a dementia plan: a WHO guide [Internet]. 2018. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/272642/9789241514132-eng.pdf?ua=1

- 9.Roberts R, Knopman DS. Classification and epidemiology of MCI. Clin Geriatr Med. 2013. November;29(4):753–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Satizabal C, Beiser AS, Seshadri S. Incidence of Dementia over Three Decades in the Framingham Heart Study. N Engl J Med. 2016. 07;375(1):93–4.• One of the longest-running longitudinal studies of dementia risk.

- 11.Ismail Z, Elbayoumi H, Fischer CE, Hogan DB, Millikin CP, Schweizer T, et al. Prevalence of Depression in Patients With Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(1):58–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu Y-T, Beiser AS, Breteler MMB, Fratiglioni L, Helmer C, Hendrie HC, et al. The changing prevalence and incidence of dementia over time - current evidence. Nat Rev Neurol. 2017;13(6):327–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Byers AL, Yaffe K. Depression and risk of developing dementia. Nat Rev Neurol. 2011. May 3;7(6):323–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xia M, Yang L, Sun G, Qi S, Li B. Mechanism of depression as a risk factor in the development of Alzheimer’s disease: the function of AQP4 and the glymphatic system. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2017;234(3):365–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ryu S-H, Jung H-Y, Lee KJ, Moon SW, Lee DW, Hong N, et al. Incidence and Course of Depression in Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease. Psychiatry Investig. 2017;14(3):271–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arbus C, Gardette V, Cantet CE, Andrieu S, Nourhashémi F, Schmitt L, et al. Incidence and predictive factors of depressive symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease: the REAL.FR study. J Nutr Health Aging. 2011;15(8):609–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bennett S, Thomas AJ. Depression and dementia: cause, consequence or coincidence? Maturitas. 2014;79(2):184–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gonzales MM, Insel PS, Nelson C, Tosun D, Schöll M, Mattsson N, et al. Chronic depressive symptomatology and CSF amyloid beta and tau levels in mild cognitive impairment. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018;33(10):1305–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boccia M, Acierno M, Piccardi L. Neuroanatomy of Alzheimer’s Disease and Late-Life Depression: A Coordinate-Based Meta-Analysis of MRI Studies. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;46(4):963–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harrington KD, Gould E, Lim YY, Ames D, Pietrzak RH, Rembach A, et al. Amyloid burden and incident depressive symptoms in cognitively normal older adults. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2017;32(4):455–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grundke-Iqbal I, Iqbal K, Tung YC, Quinlan M, Wisniewski HM, Binder LI. Abnormal phosphorylation of the microtubule-associated protein tau (tau) in Alzheimer cytoskeletal pathology. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83(13):4913–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cirrito JR, Disabato BM, Restivo JL, Verges DK, Goebel WD, Sathyan A, et al. Serotonin signaling is associated with lower amyloid-β levels and plaques in transgenic mice and humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(36):14968–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rapp MA, Hellweg R, Heinz A. [The importance of depressive syndromes for incipient Alzheimer-type dementia in advanced age]. Nervenarzt. 2011;82(9):1140–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sun X, Steffens DC, Au R, Folstein M, Summergrad P, Yee J, et al. Amyloid-associated depression: a prodromal depression of Alzheimer disease? Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(5):542–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gatchel JR, Donovan NJ, Locascio JJ, Schultz AP, Becker JA, Chhatwal J, et al. Depressive Symptoms and Tau Accumulation in the Inferior Temporal Lobe and Entorhinal Cortex in Cognitively Normal Older Adults: A Pilot Study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;59(3):975–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harrington KD, Lim YY, Gould E, Maruff P. Amyloid-beta and depression in healthy older adults: a systematic review. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2015. January;49(1):36–46.•• Review of studies investigating amyloid binding in LLD.

- 27.Alves L, Correia ASA, Miguel R, Alegria P, Bugalho P. Alzheimer’s disease: a clinical practice-oriented review. Front Neurol. 2012;3:63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prvulovic D, Hampel H. Amyloid β (Aβ) and phospho-tau (p-tau) as diagnostic biomarkers in Alzheimer’s disease. Clin Chem Lab Med. 201;49(3):367–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chung JK, Plitman E, Nakajima S, Chow TW, Chakravarty MM, Caravaggio F, et al. Lifetime History of Depression Predicts Increased Amyloid-β Accumulation in Patients with Mild Cognitive Impairment. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;45(3):907–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rapp MA, Schnaider-Beeri M, Grossman HT, Sano M, Perl DP, Purohit DP, et al. Increased hippocampal plaques and tangles in patients with Alzheimer disease with a lifetime history of major depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(2):161–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rapp MA, Schnaider-Beeri M, Purohit DP, Perl DP, Haroutunian V, Sano M. Increased neurofibrillary tangles in patients with Alzheimer disease with comorbid depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;16(2):168–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brown EE, Iwata Y, Chung JK, Gerretsen P, Graff-Guerrero A. Tau in Late-Life Depression: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016. 06;54(2):615–33.•• Review of studies investigating tau binding in LLD.

- 33.Poulin SP, Bergeron D, Dickerson BC, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Risk Factors, Neuroanatomical Correlates, and Outcome of Neuropsychiatric Symptoms in Alzheimer’s Disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;60(2):483–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilson RS, Boyle PA, Capuano AW, Shah RC, Hoganson GM, Nag S, et al. Late-life depression is not associated with dementia-related pathology. Neuropsychology. 2016;30(2):135–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Perin S, Harrington KD, Lim YY, Ellis K, Ames D, Pietrzak RH, et al. Amyloid burden and incident depressive symptoms in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. J Affect Disord. 2018. 15;229:269–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Donovan NJ, Hsu DC, Dagley AS, Schultz AP, Amariglio RE, Mormino EC, et al. Depressive Symptoms and Biomarkers of Alzheimer’s Disease in Cognitively Normal Older Adults. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;46(1):63–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liguori C, Pierantozzi M, Chiaravalloti A, Sancesario GM, Mercuri NB, Franchini F, et al. When Cognitive Decline and Depression Coexist in the Elderly: CSF Biomarkers Analysis Can Differentiate Alzheimer’s Disease from Late-Life Depression. Front Aging Neurosc i 2018;10:38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hybels CF, Blazer DG, Landerman LR, Steffens DC . Heterogeneity in symptom profiles among older adults diagnosed with major depression. Int Psychogeriatr. 2011;23(6):906–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lebowitz BD, Pearson JL, Schneider LS, Reynolds CF, Alexopoulos GS, Bruce ML, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of depression in late life. Consensus statement update. JAMA. 1997;278(14):1186–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ichikawa T, Baba H, Maeshima H, Shimano T, Inoue M, Ishiguro M, et al. Serum levels of TDP-43 in late-life patients with depressive episode. J Affect Disord. 2019. 01;250:284–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Briellmann RS, Hopwood MJ, Jackson GD. Major depression in temporal lobe epilepsy with hippocampal sclerosis: clinical and imaging correlates. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78(11):1226–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sheline YI, Pieper CF, Barch DM, Welsh-Bohmer K, Welsh-Boehmer K, McKinstry RC, et al. Support for the vascular depression hypothesis in late-life depression: results of a 2-site, prospective, antidepressant treatment trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(3):277–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kivipelto M, Ngandu T, Fratiglioni L, Viitanen M, Käreholt I, Winblad B, et al. Obesity and vascular risk factors at midlife and the risk of dementia and Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2005;62(10):1556–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Alexopoulos GS, Meyers BS, Young RC, Campbell S, Silbersweig D, Charlson M. “Vascular depression” hypothesis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54(10):915–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Taylor WD, Aizenstein HJ, Alexopoulos GS. The vascular depression hypothesis: mechanisms linking vascular disease with depression. Mol Psychiatry. 2013;18(9):963–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Valkanova V, Ebmeier KP. Vascular risk factors and depression in later life: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;73(5):406–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sheline YI, Price JL, Vaishnavi SN, Mintun MA, Barch DM, Epstein AA, et al. Regional white matter hyperintensity burden in automated segmentation distinguishes late-life depressed subjects from comparison subjects matched for vascular risk factors. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(4):524–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Khalaf A, Edelman K, Tudorascu D, Andreescu C, Reynolds CF, Aizenstein H. White Matter Hyperintensity Accumulation During Treatment of Late-Life Depression. Neuropsychopharmacology;40(13):3027–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Charlton RA, Lamar M, Zhang A, Yang S, Ajilore O, Kumar A. White-matter tract integrity in late-life depression: associations with severity and cognition. Psychol Med;44(7):1427–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li W, Muftuler LT, Chen G, Ward BD, Budde MD, Jones JL, et al. Effects of the coexistence of late-life depression and mild cognitive impairment on white matter microstructure. J Neurol Sci. 2014;338(1–2):46–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Doody RS, Thomas RG, Farlow M, Iwatsubo T, Vellas B, Joffe S, et al. Phase 3 trials of solanezumab for mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(4):311–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ostrowitzki S, Lasser RA, Dorflinger E, Scheltens P, Barkhof F, Nikolcheva T, et al. A phase III randomized trial of gantenerumab in prodromal Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2017;9(1):95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Salloway S, Sperling R, Fox NC, Blennow K, Klunk W, Raskind M, et al. Two phase 3 trials of bapineuzumab in mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(4):322–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vandenberghe R, Rinne JO, Boada M, Katayama S, Scheltens P, Vellas B, et al. Bapineuzumab for mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease in two global, randomized, phase 3 trials. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2016;8(1):18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Prins ND, Scheltens P. White matter hyperintensities, cognitive impairment and dementia: an update. Nat Rev Neurol. 2015; 11(3): 157–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li J, Wang YJ, Zhang M, Xu ZQ, Gao CY, Fang CQ, et al. Vascular risk factors promote conversion from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2011. April 26;76(17):1485–91.•• Meta-analysis of extent to which vascular health conditions predict conversion of MCI to AD.

- 57.Li J-Q, Tan L, Wang H-F, Tan M-S, Tan L, Xu W, et al. Risk factors for predicting progression from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2016. May;87(5):476–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lorius N, Locascio JJ, Rentz DM, Johnson KA, Sperling RA, Viswanathan A, et al. Vascular disease and risk factors are associated with cognitive decline in the alzheimer disease spectrum. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2015;29(1):18–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tosto G, Zimmerman ME, Carmichael OT, Brickman AM, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Predicting aggressive decline in mild cognitive impairment: the importance of white matter hyperintensities. JAMA Neurol. 2014;71(7):872–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Strickland S Blood will out: vascular contributions to Alzheimer’s disease. J Clin Invest. 2018;128(2):556–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Merlini M, Rafalski VA, Rios Coronado PE, Gill TM, Ellisman M, Muthukumar G, et al. Fibrinogen Induces Microglia-Mediated Spine Elimination and Cognitive Impairment in an Alzheimer’s Disease Model. Neuron. 2019; [EPub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gregg NM, Kim AE, Gurol ME, Lopez OL, Aizenstein HJ, Price JC, et al. Incidental Cerebral Microbleeds and Cerebral Blood Flow in Elderly Individuals. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72(9):1021–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liu J, Zhu Y-S, Khan MA, Brunk E, Martin-Cook K, Weiner MF, et al. Global brain hypoperfusion and oxygenation in amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Alzheimers Dement. 2014;10(2):162–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Beishon L, Haunton VJ, Panerai RB, Robinson TG. Cerebral Hemodynamics in Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Systematic Review. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;59(1):369–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Herman FJ, Simkovic S, Pasinetti GM. Neuroimmune Nexus of Depression and Dementia: Shared Mechanisms and Therapeutic Targets. Br J Pharmacol. 2019; [EPub ahead of print].•• Review of neuroinflammatory mechanisms underlying depression and dementia.

- 66.Santos LE, Beckman D, Ferreira ST. Microglial dysfunction connects depression and Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Behav Immun. 2016;55:151–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Koo JW, Duman RS. IL-1beta is an essential mediator of the antineurogenic and anhedonic effects of stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(2):751–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Köhler CA, Freitas TH, Maes M, de Andrade NQ, Liu CS, Fernandes BS, et al. Peripheral cytokine and chemokine alterations in depression: a meta-analysis of 82 studies. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2017. May;135(5):373–87.•• Meta-analysis of inflammation in depression.

- 69.Kalkman HO, Feuerbach D. Antidepressant therapies inhibit inflammation and microglial M1-polarization. Pharmacol Ther. 2016;163:82–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wohleb ES, McKim DB, Sheridan JF, Godbout JP. Monocyte trafficking to the brain with stress and inflammation: a novel axis of immune-to-brain communication that influences mood and behavior. Front Neurosci. 2014;8:447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Brosseron F, Krauthausen M, Kummer M, Heneka MT. Body fluid cytokine levels in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease: a comparative overview. Mol Neurobiol. 2014;50(2):534–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lai KSP, Liu CS, Rau A, Lanctôt KL, Köhler CA, Pakosh M, et al. Peripheral inflammatory markers in Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 175 studies. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2017;88(10):876–82.•• Meta-analysis of inflammation in AD.

- 73.Su L, Faluyi YO, Hong YT, Fryer TD, Mak E, Gabel S, et al. Neuroinflammatory and morphological changes in late-life depression: the NIMROD study. Br J Psychiatry. 2016;209(6):525–6.27758838 [Google Scholar]

- 74.Fan Z, Brooks DJ, Okello A, Edison P. An early and late peak in microglial activation in Alzheimer’s disease trajectory. Brain. 2017;140(3); 792–803.• Documents trajectory of neuroinflammation in MCI and AD.

- 75.Soczynska JK, Mansur RB, Brietzke E, Swardfager W, Kennedy SH, Woldeyohannes HO, et al. Novel therapeutic targets in depression: minocycline as a candidate treatment. Behav Brain Res. 2012;235(2):302–17.22963995 [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rosenblat JD, McIntyre RS. Efficacy and tolerability of minocycline for depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. J Affect Disord. 2018;227:219–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Boots EA, Schultz SA, Oh JM, Larson J, Edwards D, Cook D, et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness is associated with brain structure, cognition, and mood in a middle-aged cohort at risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Imaging Behav. 2015;9(3):639–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Laurin D, Verreault R, Lindsay J, MacPherson K, Rockwood K. Physical activity and risk of cognitive impairment and dementia in elderly persons. Arch Neurol. 2001;58(3):498–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wrosch C, Schulz R, Miller GE, Lupien S, Dunne E. Physical health problems, depressive mood, and cortisol secretion in old age: buffer effects of health engagement control strategies. Health Psychol. 2007;26(3):341–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hendrie HC, Albert MS, Butters MA, Gao S, Knopman DS, Launer LJ, et al. The NIH Cognitive and Emotional Health Project. Report of the Critical Evaluation Study Committee. Alzheimers Dement. 2006;2(1):12–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lee Y, Park K. Does physical activity moderate the association between depressive symptoms and disability in older adults? Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23(3):249–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Williamson GM. Extending the activity restriction model of depressed affect: Evidence from a sample of breast cancer patients. Health Psychology. 2000;19(4):339–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Benyamini Y, Lomranz J. The relationship of activity restriction and replacement with depressive symptoms among older adults. Psychol Aging. 2004;19(2):362–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wilson RS, Scherr PA, Schneider JA, Tang Y, Bennett DA. Relation of cognitive activity to risk of developing Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2007. 13;69(20):1911–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Schooler C, Mulatu MS, Oates G. The continuing effects of substantively complex work on the intellectual functioning of older workers. Psychol Aging. 1999;14(3):483–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Verghese J, Lipton RB, Katz MJ, Hall CB, Derby CA, Kuslansky G, et al. Leisure activities and the risk of dementia in the elderly. N Engl J Med. 2003. 19;348(25):2508–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Fabrigoule C, Letenneur L, Dartigues JF, Zarrouk M, Commenges D, Barberger-Gateau P. Social and leisure activities and risk of dementia: a prospective longitudinal study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1995;43(5):485–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.George LK, Ellison CG, Larson DB. Explaining the Relationships between Religious Involvement and Health. Psychological Inquiry. 2002;13(3):190–200. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Khalsa DS. Stress, Meditation, and Alzheimer’s Disease Prevention: Where The Evidence Stands. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;48(1):1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Isaac V, Stewart R, Artero S, Ancelin M-L, Ritchie K. Social activity and improvement in depressive symptoms in older people: a prospective community cohort study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;17(8):688–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Dickinson WJ, Potter GG, Hybels CF, McQuoid DR, Steffens DC. Change in stress and social support as predictors of cognitive decline in older adults with and without depression. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;26(12):1267–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Berkman LF. Which influences cognitive function: living alone or being alone? Lancet. 2000;5;355(9212):1291–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Zuelsdorff ML, Koscik RL, Okonkwo OC, Peppard PE, Hermann BP, Sager MA, et al. Social support and verbal interaction are differentially associated with cognitive function in midlife and older age. Neuropsychol Dev Cogn B Aging Neuropsychol Cogn. 2019;26(2):144–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hays JC, Steffens DC, Flint EP, Bosworth HB, George LK. Does social support buffer functional decline in elderly patients with unipolar depression? Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(11):1850–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Steffens DC, Pieper CF, Bosworth HB, MacFall JR, Provenzale JM, Payne ME, et al. Biological and social predictors of long-term geriatric depression outcome. Int Psychogeriatr. 2005;17(1):41–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Shankar A, Hamer M, McMunn A, Steptoe A. Social isolation and loneliness: relationships with cognitive function during 4 years of follow-up in the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Psychosom Med. 2013;75(2):161–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Tilvis RS, Kähönen-Väre MH, Jolkkonen J, Valvanne J, Pitkala KH, Strandberg TE. Predictors of cognitive decline and mortality of aged people over a 10-year period. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2004;59(3):268–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Fratiglioni L, Wang HX, Ericsson K, Maytan M, Winblad B. Influence of social network on occurrence of dementia: a community-based longitudinal study. Lancet. 2000;15;355(9212):1315–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Stern Y Cognitive reserve in ageing and Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2012. November;11(11):1006–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Okonkwo OC, Schultz SA, Oh JM, Larson J, Edwards D, Cook D, et al. Physical activity attenuates age-related biomarker alterations in preclinical AD. Neurology. 2014;83(19):1753–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Vemuri P, Lesnick TG, Przybelski SA, Knopman DS, Machulda M, Lowe VJ, et al. Effect of intellectual enrichment on AD biomarker trajectories: Longitudinal imaging study. Neurology. 2016. March 22;86(12):1128–35.• Longitudinal study of effect of cognitive enrichment on appearance of AD biomarkers.

- 102.Cooney GM, Dwan K, Greig CA, Lawlor DA, Rimer J, Waugh FR, et al. Exercise for depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;12;(9):CD004366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.An S, Jung H, Lee S. Moderating Effects of Community Social Capital on Depression in Later Years of Life: A Latent Interaction Model. Clin Gerontol. 2019;42(1):70–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Swartz M, Blazer DG, Nelson CB. Sex and depression in the National Comorbidity Survey. I: Lifetime prevalence, chronicity and recurrence. J Affect Disord. 1993. November;29(2–3):85–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Seshadri S, Wolf PA, Beiser A, Au R, McNulty K, White R, et al. Lifetime risk of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. The impact of mortality on risk estimates in the Framingham Study. Neurology. 1997;49(6):1498–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Pike CJ. Sex and the development of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci Res. 2017;95(1–2):671–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Ma L, Xu Y, Wang G, Li R. What do we know about sex differences in depression: A review of animal models and potential mechanisms. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2019. 08;89:48–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.GBD 2016 Dementia Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18(1):88–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Buchman AS, Wilson RS, Boyle PA, Bienias JL, Bennett DA. Grip strength and the risk of incident Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroepidemiology. 2007;29(1–2):66–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Scarmeas N, Albert M, Brandt J, Blacker D, Hadjigeorgiou G, Papadimitriou A, et al. Motor signs predict poor outcomes in Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2005;64(10):1696–703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Beauchet O, Annweiler C, Callisaya ML, De Cock A-M, Helbostad JL, Kressig RW, et al. Poor Gait Performance and Prediction of Dementia: Results From a Meta-Analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016;17(6):482–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Carstensen LL, Fung HH, Charles ST. Socioemotional Selectivity Theory and the Regulation of Emotion in the Second Half of Life. Motivation and Emotion. 2003;27(2):103–23. [Google Scholar]

- 113.Chow S-M, Hamagani F, Nesselroade JR. Age differences in dynamical emotion-cognition linkages. Psychol Aging. 2007;22(4):765–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Neupert SD, Almeida DM, Charles ST. Age differences in reactivity to daily stressors: the role of personal control. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2007;62(4):P216–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Garnefski N, Kraaij V. Relationships between cognitive emotion regulation strategies and depressive symptoms: A comparative study of five specific samples. Personality and Individual Differences. 2006;40(8):1659–69. [Google Scholar]

- 116.Perera T, George MS, Grammer G, Janicak PG, Pascual-Leone A, Wirecki TS. The Clinical TMS Society Consensus Review and Treatment Recommendations for TMS Therapy for Major Depressive Disorder. Brain Stimul. 2016;9(3):336–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Kim JU, Weisenbach SL, Zald DH. Ventral prefrontal cortex and emotion regulation in aging: A case for utilizing transcranial magnetic stimulation. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;34(2):215–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Newhouse P, Kellar K, Aisen P, White H, Wesnes K, Coderre E, et al. Nicotine treatment of mild cognitive impairment: a 6-month double-blind pilot clinical trial. Neurology. 2012;78(2):91–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Gandelman JA, Kang H, Antal A, Albert K, Boyd BD, Conley AC, et al. Transdermal Nicotine for the Treatment of Mood and Cognitive Symptoms in Nonsmokers With Late-Life Depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2018;79(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]