Abstract

Atherosclerosis is a chronic inflammatory disease caused by lipids and calcareous accumulations in the vascular wall due to an inflammatory reaction. Recent reports have demonstrated that regulatory T (Treg) cells have an important role as a new treatment for atherosclerosis. This study suggests that bee venom phospholipase A2 (bvPLA2) may be a potential therapeutic agent in atherosclerosis by inducing Treg cells. We examined the effects of bvPLA2 on atherosclerosis using ApoE-/- and ApoE-/-/Foxp3DTR mice. In this study, bvPLA2 increased Treg cells, followed by a decrease in lipid accumulation in the aorta and aortic valve and the formation of foam cells. Importantly, the effect of bvPLA2 was found to depend on Treg cells. This study suggests that bvPLA2 can be a potential therapeutic agent for atherosclerosis.

Keywords: bee venom, phospholipase A2, PLA2, atherosclerosis, Tregs

1. Introduction

Atherosclerosis is a chronic inflammatory disease that causes cardiovascular heart disease. Lipid accumulation, a major cause of disease, occurs in the arterial walls and causes the narrowing of blood vessels by producing blood clots. The main risk factors of this disease include smoking, obesity, hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, and diabetes. It is well accepted that atherosclerosis is related to the innate and adaptive immune systems. In particular, T cells and macrophages are involved in the development of atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis is ultimately caused by the interaction among endothelial cells, macrophages, smooth muscle cells, and lymphocytes, which are highly associated with lipid-laden macrophage foam cells and pro-inflammatory T cell factors [1,2,3,4].

It has been reported that secreted phospholipase A2 (sPLA2) is a disulfide-rich Ca2+-requiring enzyme that releases lysophospholipid products by catalyzing the sn-2 ester bond hydrolysis of glycerophospholipids. In addition, sPLA2 binds to a specific membrane receptor to act as a ligand to induce cellular signaling independent of enzymatic activity [5,6].

According to previous reports, group III PLA2 is involved in foam cell formation in macrophages. The formation of foam cells is triggered when monocyte-derived macrophages accumulate in the atherosclerotic lesion site or arterial wall where lipids are deposited. These monocyte-derived macrophages take up oxidized low-density lipoprotein (oxLDL) via a scavenger receptor. Moreover, foam cells cause an inflammatory response inside the arterial wall and are known to be an important component of atherosclerotic plaque formation [7].

CD4+ Foxp3+ regulatory T (Treg) cells are being investigated as an alternative method to reduce foam cells, and they are important factors in atherosclerosis [8]. In addition, they maintain immunologic homeostasis through the secretion of immunosuppressive cytokines and may have a potential therapeutic effect on atherosclerosis [9,10,11,12,13]. The importance of Treg cells has already been identified in several diseases.

Previously, we demonstrated the effect of bee venom phospholipase A2 (bvPLA2), a major active compound controlling the generation of Treg cells, in several immune-related diseases such as asthma, kidney disease, atopic dermatitis, and Alzheimer’s disease [14,15,16,17,18]. Many of the biological effects of PLA2s are dependent on their catalytic activity [19]. It also has been proposed that bvPLA2 increases the expression of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), which then binds to the EP2 receptor in naïve T helper cells. Moreover, it induces differentiation into Treg cells [20].

Here, we hypothesized that bvPLA2 may reduce the risk of atherosclerosis caused by lipid accumulation and suppress the transformation of macrophages into foam cells by Treg cell. In this study, we confirmed a reduction of lipid accumulation and foam cell formation by treating with bvPLA2. Furthermore, we suggest that bvPLA2 may be a significant therapeutic agent to mitigate arteriosclerosis.

2. Results

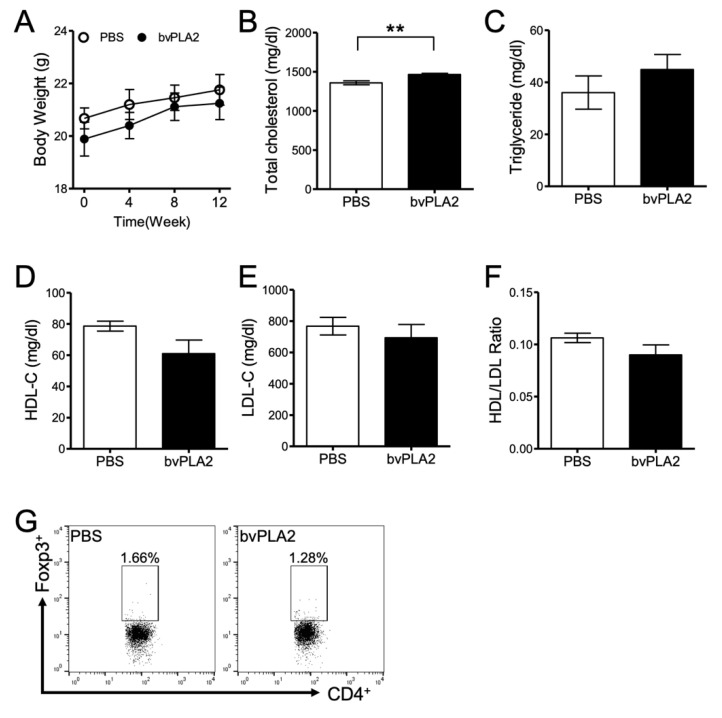

2.1. Effect of bvPLA2 Treatment on Atherosclerotic Mice

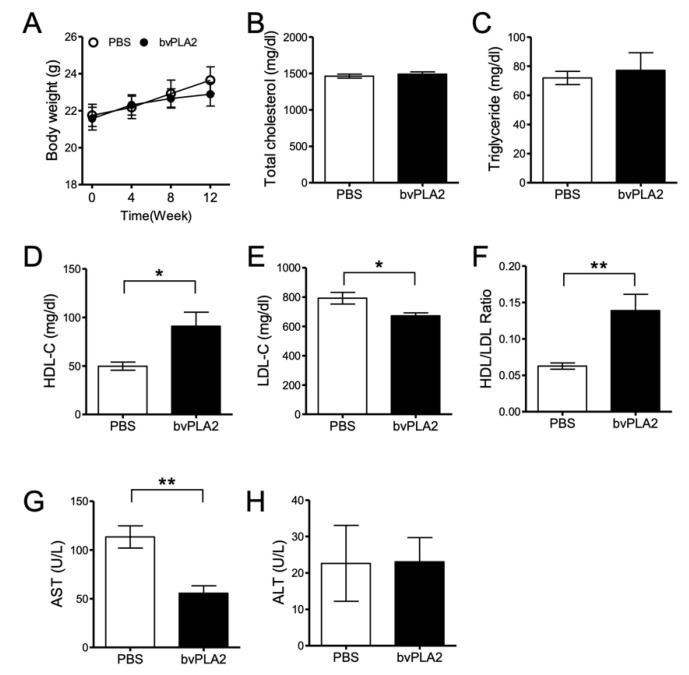

We investigated the therapeutic effect of bvPLA2 on atherosclerosis caused by a high-fat diet. Eight- to ten-week-old ApoE knock out (ApoE-/-) mice were used to induce hypercholesterolemia with an atherogenic high-cholesterol diet (D12336; Research Diets, Inc., New Brunswick, NJ, USA) for 12 weeks. The mice were divided into phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and bvPLA2 (0.2 mg/kg) groups and injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) every 2 days after a 4-week diet. Body weight was measured every week, and it increased less in the bvPLA2 group compared to that in the PBS group (Figure 1A). However, there was no significant difference between the two groups. Blood was also collected from the inferior vena cava to perform lipid analysis. Total cholesterol (TC) and triglyceride (TG) were not significantly different between those groups (Figure 1B,C). However, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) was significantly increased (Figure 1D, p < 0.05, t = 2.739, df = 10) and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) decreased (Figure 1E, p < 0.05, t = 2.694, df = 10) in the bvPLA2-treated group. The HDL/LDL ratio was significantly increased in the bvPLA2 group (Figure 1F, p < 0.01, t = 3.341, df = 10). Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) were also measured to confirm the hepatotoxicity of bvPLA2. It was found that AST levels were significantly decreased in the bvPLA2 group (Figure 1G, p < 0.01, t = 4.214, df = 8), but there was no change in ALT (Figure 1H). To address the systemic effects of bvPLA2 on the production of bioactive lipids, the levels of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) and arachidonic acid (AA) in vivo were analyzed. The results showed that bvPLA2 (0.2 mg/kg, i.p.) treatment did not induce the release of PGE2 or arachidonic acids in various tissues (Appendix A, Figure A1).

Figure 1.

The effect of bee venom phospholipase A2 (bvPLA2) on atherosclerotic ApoE-/- mice. An atherogenic high-cholesterol diet (D12336) was fed to ApoE-/- mice for 12 weeks, and mice were then injected with PBS or bvPLA2 (0.2 mg/kg, i.p) every 2 days after a 4-week diet. The serum was separated from the blood and analyzed through a biochemical analyzer. (A) Body weight and diet were measured at 0, 4, 8, and 12 weeks. (B) Total cholesterol, (C) triglyceride, (D) high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), (E) low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), (F) HDL/LDL ratio, (G) aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and (H) alanine aminotransferase (ALT) were measured in the serum for lipid analysis. The data are displayed as the means ± SEM. The statistical analyses were conducted with Student’s unpaired t test; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 vs. the PBS group; n = 10.

2.2. bvPLA2 Treatment Increases Regulatory T Cells in Lymph Nodes

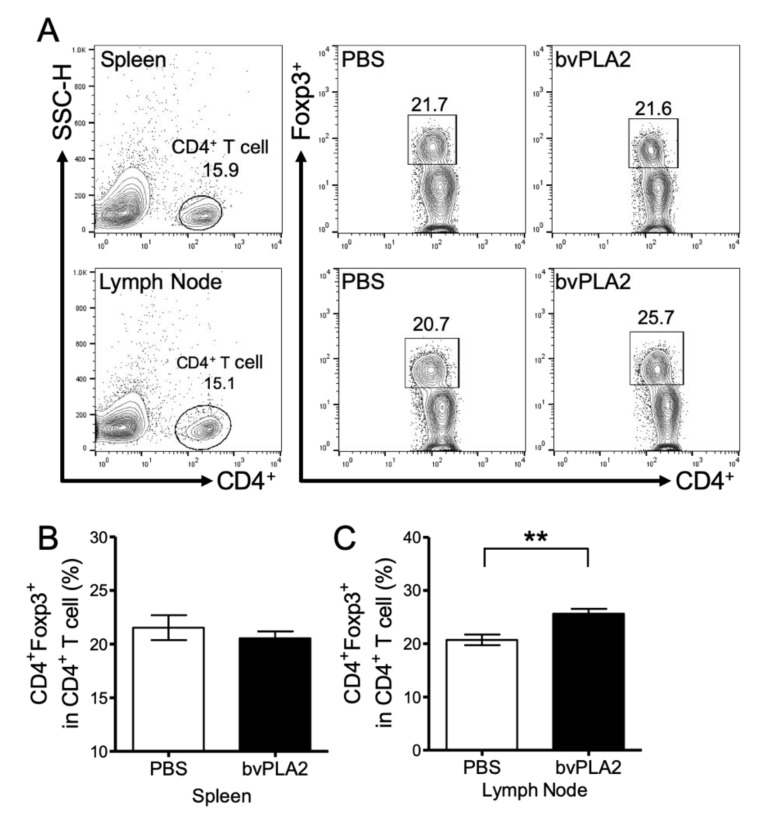

To measure the increase of Treg cells following bvPLA2 treatment in the tissues, mouse spleens and peripheral lymph nodes (brachial, axial) were analyzed. Monocytes were isolated from the spleen and lymph nodes and analyzed by flow cytometry (Figure 2A). In the spleen, there was no difference in the CD4+ Foxp3+ Treg cell populations between the PBS and bvPLA2 groups (Figure 2B). On the other hand, there was a significant increase in CD4+ Foxp3+ Treg cells in the lymph nodes of the bvPLA2 group (Figure 2C, p < 0.01, t = 3.601, df = 20). This result is in accordance with previous results that the Treg cell populations quantitatively differ between the peripheral lymph nodes and the spleen to maintain homeostasis [21].

Figure 2.

Effect of bvPLA2 on CD4+ Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. Single cells from the spleen and peripheral lymph node were measured using a fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS) Calibur flow cytometer. (A) Representative flow cytometry plots from spleen (upper panel) and lymph node (lower panel) in ApoE-/- mice. Doublets and small multiplets were filtered by side-scatter height (SSC-H), and only CD4+ cells were gated. The cells were gated on Foxp3+ cells and analyzed. Number shows the percentage of CD4+ cells (left, upper and lower panel) out of total cells and Foxp3+ cells (right, upper and lower panel) in CD4+ cells with treatment of PBS and bvPLA2. Graphs show the percentage of CD4+ Foxp3+ Treg cells in CD4+ T cells in the spleen (B) and lymph node (C). The data are displayed as the means ± SEM. Statistical analyses were conducted with Student’s unpaired t test; **, p < 0.01 vs. the PBS group; n = 11.

2.3. bvPLA2 Treatment Reduces the Inflammatory Cytokines

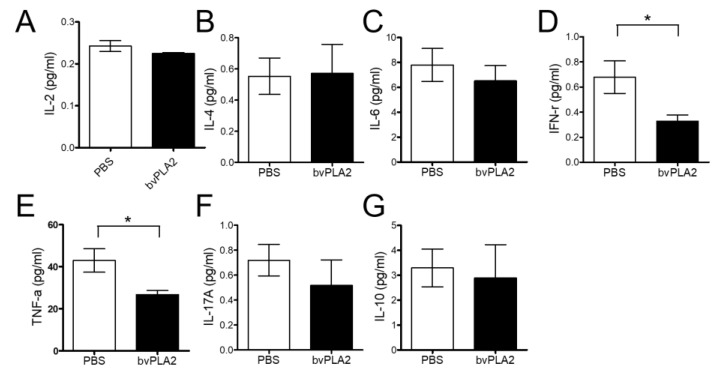

We analyzed and compared the inflammatory cytokines between PBS and bvPLA2 serum with a Cytometric Bead Array (CBA) Mouse Th1/Th2/Th17 Cytokine Kit. Interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) (Figure 3D, p < 0.01, t = 1.943, df = 14) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) (Figure 3E, p < 0.01, t = 2.728, df = 16) serum levels significantly decreased in the bvPLA2 group compared to those in the PBS group. However, there was no significant difference in interleukin (IL)-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-17A, and IL-10 (Figure 3A–C,F,G). This result suggests that bvPLA2 may potentially play a role in alleviating atherosclerosis by reducing cytokines.

Figure 3.

Effect of bvPLA2 on inflammatory cytokines. Inflammatory cytokines were analyzed and quantified in the serum by FACS analysis. The serum that separated from the blood was analyzed. The inflammatory cytokines, (A) IL-2, (B) IL-4, (C) IL-6, (D) IFN-γ, (E) TNF-α, (F) IL-17A, and (G) IL-10, were investigated. The data are displayed as the means ± SEM. The statistical analyses were conducted with Student’s unpaired t test; *, p < 0.05 vs. the PBS group; n = 9.

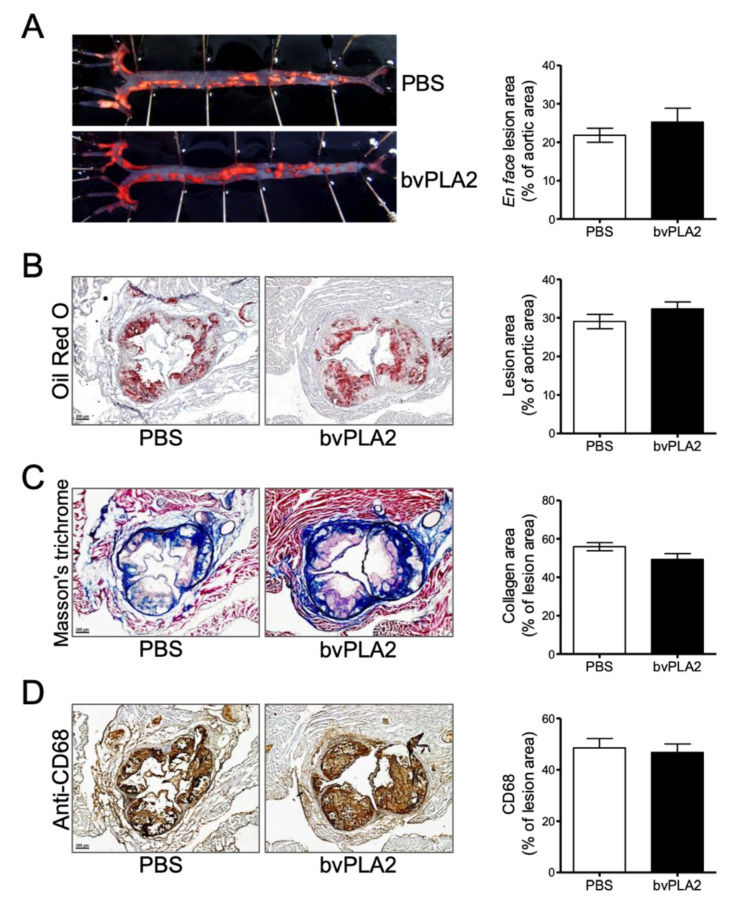

2.4. bvPLA2 Treatment Reduces Atherosclerotic Lesions and Foam Cell Formation

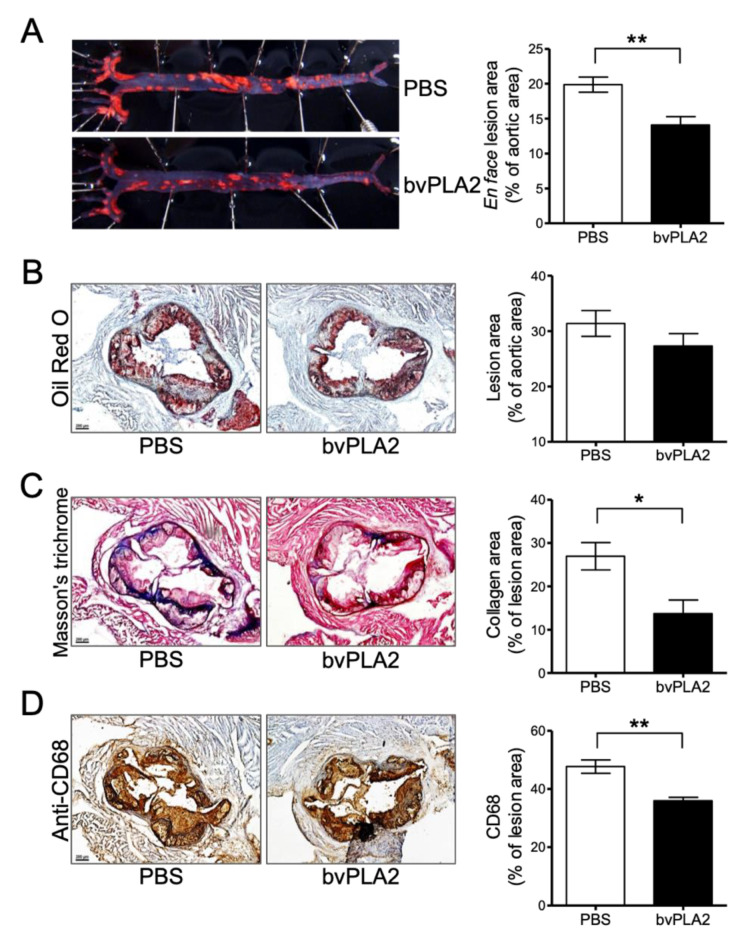

We confirmed the effect of Treg cells induced by bvPLA2 on atherosclerosis via the “en face” method. We extracted the aorta of mice fed an atherogenic diet for 12 weeks and measured the aorta with Oil red O staining. Indeed, the incidence of atherosclerosis was dramatically reduced in the bvPLA2-treated group (14.11% ± 1.19%) compared to that in the PBS group (19.87% ± 1.08%) (Figure 4A, p < 0.01, t = 2.967, df = 10). Furthermore, the accumulation of lipid on the aortic valve was decreased, although this was not significant (Figure 4B). Collagen staining with Masson’s trichrome (MT) was performed to confirm fibrosis in the heart. There was a significant reduction in fibrosis in the bvPLA2 group compared to that in the PBS group (Figure 4C, p < 0.05, t = 1.943, df = 14). Then, we identified and quantified foam cells through immunohistochemistry (IHC) using anti-CD68, which is a macrophage marker. Macrophages that developed into foam cells were significantly decreased in the bvPLA2 group (Figure 4D, p < 0.01, t = 4.528, df = 8). In this experiment, we found that bvPLA2-induced Treg cells may have a therapeutic effect on atherosclerosis by inhibiting foam cell formation along with reducing fibrosis.

Figure 4.

The therapeutic effect of bvPLA2 on atherosclerosis. (A) ApoE-/- mice aortas were measured with Oil red O staining and confirmed with an “en face” method. (B) Lipid accumulation of the aortic valve with Oil red O, (C) fibrosis with Masson’s trichrome (MT), (D) foam cell formation by macrophage with immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining were measured and quantified in heart sections (magnification ×50). The data are displayed as the means ± SEM. Statistical analyses were conducted with Student’s unpaired t test; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 vs. the PBS group; n = 6.

2.5. Effect of bvPLA2 Treatment on ApoE-/-/Foxp3DTR Mice

We used the ApoE-/-/Foxp3DTR mice to confirm whether bvPLA2 has therapeutic effects on Treg depletion. ApoE-/-/Foxp3DTR mice fed an atherogenic diet for 12 weeks were injected i.p. with either PBS or bvPLA2 (0.2 mg/kg) every 2 days after a 4-week diet. For Treg depletion, ApoE-/-/Foxp3DTR mice were injected i.p. with 1 µg of diphtheria toxin (DT) for two consecutive days during the atherogenic diet. There were no significant differences in body weight, TG, HDL-C, LDL-C, or HDL/LDL ratio between the PBS and bvPLA2 groups (Figure 5A,C–F). However, the total cholesterol slightly increased in the bvPLA2 group (Figure 5B, p < 0.01, t = 3.464, df = 9). Treg depletion was confirmed by flow cytometry analysis using mouse peripheral lymph node cells (Figure 5G). Thus, we confirmed that bvPLA2 exerts its functions depending on the presence of Treg.

Figure 5.

The effect of bvPLA2 on ApoE-/-/Fopx3DTR mice. ApoE-/-/Fopx3DTR mice were fed an atherogenic diet for 12 weeks, as in the previous experiment. They were injected with PBS or bvPLA2 (0.2 mg/kg, i.p) every 2 days after a 4-week diet. In addition, 1 µg of diphtheria toxin (DT) was injected for two consecutive days to deplete Tregs. (A) Body weight was measured weekly and shown at 0, 4, 8, and 12 weeks. (B) Total cholesterol, (C) triglyceride, (D) HDL-C, (E) LDL-C, and (F) HDL/LDL ratio were measured for lipid analysis in the serum. (G) Treg depletion was confirmed in the peripheral lymph node by FACS analysis. The cells were gated on CD4+ Foxp3+ cells and analyzed. Number showed the percentage of CD4+ Foxp3+ cells in total cells with treatment of PBS (left panel) and bvPLA2 (right panel). The data are displayed as the means ± SEM. The statistical analyses were conducted with Student’s unpaired t test; **, p < 0.01 vs. the PBS group; n = 7.

2.6. Effects of Treg Deletion on the Treatment of Arteriosclerosis with bvPLA2

We also performed the same experimental “en face” method and Oil red O staining with the aorta from ApoE-/-/Foxp3DTR mice. There were no significant differences in lipid accumulation in the Treg-depleted mouse aortas of the PBS and bvPLA2 groups (Figure 6A,B). Fibrosis was measured and quantified by MT staining, and foam cell formation was also confirmed with IHC staining. However, there were no significant differences (Figure 6C,D). These results suggest that the therapeutic effect of bvPLA2 is dependent on Treg cells in the atherosclerotic lesion.

Figure 6.

The therapeutic effect of bvPLA2 treatment on the atherosclerotic lesions of Treg-depleted mice. Atherosclerotic lesions were confirmed in the aorta of Treg-depleted mice. (A) The aorta was measured and quantified with Oil red O staining and an “en face” method. (B) Lipid accumulation of the aortic valve, (C) fibrosis, and (D) foam cell formation were measured and quantified in heart sections (magnification ×50). The data are displayed as the means ± SEM (n = 5). The statistical analyses were conducted with Student’s unpaired t test.

3. Discussion

Atherosclerosis is a chronic inflammatory disease caused by lipid and calcareous accumulation. It leads to blood vessel narrowing and clogging and eventually death. The main cause of atherosclerosis is thought to be an inflammatory reaction by foam cells, in which monocyte-derived macrophages take up oxLDL. Current treatments of atherosclerosis include drugs of the statin family, angioplasty, or stent implantation. Recently, Treg cells were mentioned as an alternative therapy for atherosclerosis [10,12,13]. Foks et al. and Lin et al. mentioned that Treg cells are involved in foam cell formation, cholesterol metabolism, and immune suppression [11,22]. In previous studies, it was shown that increased Treg cells inhibited atherosclerosis [23]. Conversely, Treg cell deficiency further induced atherosclerosis [24]. Based on these studies, we examined the therapeutic effect of increased Treg cells by bvPLA2 on atherosclerosis.

Previously, several reports confirmed the effect of bvPLA2 according to the dosage administration and experimental systems. The activity of bvPLA2 is well studied by the experimental methods—especially, the adverse effect induced by bvPLA2 when it is injected directly into the paw and spinal cord at a wide range (ng–µg) of dosages [25,26,27], and on the other hand, the beneficial effect of bvPLA2 found when it is injected peritoneally at 0.1–1 mg/kg in an in vivo study [14,15,20,28,29]. Based on these results, we selected and applied 0.2 mg/kg of bvPLA2 to show the therapeutic effect in atherosclerosis.

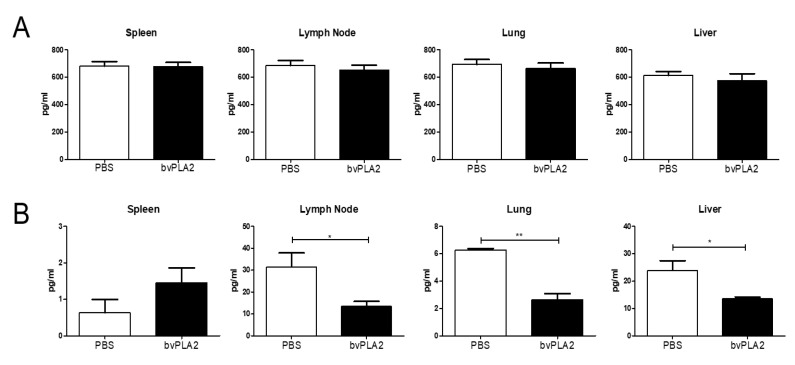

Prior to confirming the effect of bvPLA2 on atherosclerosis, the biologically active lipid metabolites (PGE2 and AA) were analyzed to exclude the potential effects of bvPLA2 on the systemic production of PGE2 and AA. This demonstrated that PGE2 and AA levels were not increased by bvPLA2 treatments, suggesting that a relatively low dosage of bvPLA2 (0.2 mg/kg) did not affect lipid metabolite production systemically. These results implicated that the biological effects of bvPLA2 on Treg inductions could be mediated mainly by the paracrine production of biological lipids at sites where Treg cells were differentiated, such as at lymph nodes and the spleen.

We confirmed that bvPLA2 did not affect total cholesterol, but bvPLA2 increased HDL and decreased LDL and AST significantly (Figure 1). However, bvPLA2 treatment following Treg cell depletion, increased cholesterol but did not affect changes in LDL and HDL. From these results, it was confirmed that the increased Treg cells by bvPLA2 affected lipoprotein production, and its further anti-atherogenic effect was confirmed.

ApoE-/- and ApoE-/-/Foxp3DTR mice were used to establish an atherosclerosis model by consuming a high-cholesterol diet according to several reports [30,31]. In this study, we found that bvPLA2 treatment increased Treg cells in the peripheral lymph nodes of ApoE-/- mice (Figure 2). Treg cells expanded by bvPLA2 also reduced several inflammatory cytokines (Figure 3). Moreover, these results had an effect on foam cell formation and lipid accumulation in the aorta (Figure 4). We examined whether the increased Treg cells by bvPLA2 were associated with suppressed foam cell formation and reduced inflammatory reactions. Interestingly, these results did not appear when Treg cells were depleted (Figure 5 and Figure 6). Upon Treg depletion, bvPLA2 only affected total cholesterol and HDL-C (Figure 5). The effect of bvPLA2 was also apparent in the atherosclerotic aorta (Figure 6). Based on these results, bvPLA2 has an anti-atherosclerotic effect that is dependent on Treg cells.

In this study, bvPLA2 increased HDL-C and decreased LDL-C by increasing Treg cells (Figure 1D–F). It is known that HDL-C, good cholesterol, plays an important role in cardiovascular-related disease. Further, LDL and HDL are important for determining the risk of coronary artery disease (CAD) [32]. Rueda et al. reported the relationship between HDL-C and Treg cells, revealing that HDL-C is involved in Treg cell survival and viability [33]. However, the mechanism of bvPLA2 on cholesterol remains to be established. Our results suggest that bvPLA2 has an important role in atherosclerosis by modulating Treg cells. These results may useful in developing new treatments for other heart diseases.

4. Material and Methods

4.1. Mice

Male 8- to 10-week-old ApoE-/- mice (B6.129P2-Apoetm1Unc/J) and C57BL/6J mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (OrientBio, Seongnam, Korea). ApoE-/- mice were crossed with Foxp3DTR mice (B6.1 29(Cg)-Foxp3tm3(DTR/GFP)Ayr/J) to generate ApoE-/-/Foxp3DTR mice. ApoE-/- and ApoE-/-/Foxp3DTR mice were fed an atherogenic high-cholesterol diet (D12336; Research Diets, Inc., New Brunswick, NJ, USA) containing 35% fat, 1.25% cholesterol, and 0.5% sodium cholate. This atherogenic diet enhances plasma cholesterol levels to double in hypomorphic ApoE mice, unlike the Western diet without cholate [34]. The mice were fed an atherogenic diet for 12 weeks, and PBS or bvPLA2 (0.2 mg/kg, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) were injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) every 2 days after a 4-week diet. bvPLA2 was dissolved in PBS as a vehicle. For Treg depletion experiments, ApoE-/-/Foxp3DTR male mice were given i.p. injections of 1 µg diphtheria toxin (DT, Sigma-Aldrich), dissolved in PBS, for two consecutive days. After 12 weeks of a high-fat diet, the animals were sacrificed for tissue sampling after 8 h of fasting. All mice were housed in conventional plastic cages with free access to feed and water at 23 ± 2 °C, 60% ± 10% humidity, and a 12-h light/dark photoperiod. The study was conducted following the Rules for Animal Care and the Guiding Principles for Animal Experiments Using Animals and was approved on 4. November 2016 by the University of Kyung Hee Animal Care and Use Committee (KHUASP(SE)-16-119).

4.2. Body Weight and Lipid Profile

The body weight and diet intake of mice were monitored every week. Blood samples were collected from the inferior vena cava and centrifuged (1000× g at 4 °C for 10 min) to separate the serum. Total cholesterol, triglyceride, high-density lipoprotein (HDL-C), low-density lipoprotein (LDL-C), AST, and ALT were determined using a Beckman Coulter AU480 automatic biochemistry analysis system with kit reagents provided by the manufacturer (Beckman Coulter, Inc., Brea, CA, USA).

4.3. Flow Cytometric Analysis

Flow cytometric analysis of regulatory T (Treg) cells was performed using phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated anti-mouse CD4 (clone RM4-5; BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA, USA) and Alexa Fluor 647 anti-mouse/rat Foxp3 antibodies (clone MF23; BD Biosciences). Treg depletion was confirmed using allophycocyanin (APC)-conjugated anti-mouse CD4 antibody (clone 145-2C11; eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA). Spleens and peripheral lymph nodes were isolated and separated into single cells using 25 µm nylon mesh (BD Biosciences). After treatment with red blood cell (RBC) lysis buffer (BD Biosciences), the cells were washed twice with PBS and stained with PE-conjugated anti-mouse CD4 antibody in staining buffer (BD Biosciences) on ice for 30 min in the dark. The cells were washed twice with PBS, and fixation/permeabilization buffer (eBioscience) was added for 15 min at room temperature (RT). Subsequently, the cells were washed twice with PBS and stained with Alexa Fluor 647 anti-Foxp3 antibody in the dark at 4 °C for 1 h. Then, the samples were analyzed with a FACS Calibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) and FLOWJO software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR, USA).

4.4. ELISA and Inflammatory Cytokines Analysis

Mouse prostaglandin E2 (PGE2, Enzo, Farmingdale, NY, USA) and arachidonic acid (AA, Aviva systems biology, San Diego, CA, USA) levels were measured by using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Inflammatory cytokine levels in serum were analyzed with a Cytometric Bead Array (CBA) Mouse Th1/Th2/Th17 Cytokine Kit (BD Biosciences) according to the protocol recommended by the manufacturer. Serum was obtained from blood samples by centrifuging 1000× g at 4 °C for 10 min. A mixture of captured antibody beads and PE-conjugated antibody was added to the serum and incubated at RT. After washing with PBS, the data were acquired using a BD FACS Calibur flow cytometer and analyzed using BD CellQuest, BD CBA software (BD Biosciences). Individual cytokine concentrations were indicated by their fluorescence intensities.

4.5. Measurement of Atherosclerotic Lesions in the Aorta

To measure the atherosclerotic lesion of the aorta, aortas were extracted and fixed with 10% formalin. After washing with PBS, an incision was performed using the “en Face” method. The iliac arteries were also incised and fixed. The fixed aortas were stained with Oil red O, and images of atherosclerotic lesions were obtained a camera (Samsung, Seoul, Korea). Total aortic surface area and Oil red O staining area were measured using Adobe Photoshop software version 5.0.1 (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA, USA).

4.6. Histological Analysis

The heart and ascending aorta were embedded into optical cutting temperature (OCT) compound to measure lipid accumulation in the aortic sinus. Frozen tissues were sectioned into 7 µm thick sections. The sections that contained the cusps of 3 aortic valves at the junction of the aorta and left ventricle were selected. Oil red O staining was performed to confirm the lipid accumulation in the aortic sinus. Images were obtained using a Zeiss inverted microscope (Axio Observer 5), and the atherosclerotic lesions were observed. Lipid accumulation in the aortic sinus was measured using Adobe Photoshop software version 5.0.1 (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA, USA). Masson’s trichrome (MT) staining was performed to measure fibrosis in the aortic sinus. Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining was also carried out to examine foam cell formation. Anti-CD68 antibody (clone H-255; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA) was used for IHC staining at a 1:50 concentration. MT staining and IHC staining were analyzed using ImageJ Fiji software (WS Rasband, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). The quantitation was calculated as the percentage of the total aortic sinus versus the stained portion.

4.7. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis of the data was performed using Prism 7 software (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). The results were expressed as the means ± SEM. Two-tailed Student’s unpaired test was performed to compare the two groups.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

The effect of bvPLA2 on prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) and arachidonic acid (AA) levels in mice. Mice were injected with PBS or bvPLA2 (0.2 mg/kg, i.p) every 2 days for 5 times. After the injection, (A) PGE2 and (B) AA levels were analyzed in mouse spleen, lymph node, lung, and liver using ELISA system. The data are displayed as the means ± SEM. Statistical analyses were conducted with Student’s unpaired t test; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 vs. the PBS group; n = 3–4.

Author Contributions

G.-H.K. carried out the experiments and wrote the manuscript. H.Y. carried out the experiments and edited the manuscript. S.L., D.B.C., J.K. and D.S. discussed and performed the data analysis. H.B. supervised the project and edited the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT-2020RIA2B5B03002164).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Key Contribution

Our study indicates that bvPLA2 markedly suppressed the progression of atherosclerosis, reducing lipid accumulation in the aorta and aortic valve. These effects were mediated by increasing the Treg cell population and suppressing foam cell formation in the aorta. To our knowledge, we demonstrated for the first time that bvPLA2 possesses therapeutic potentials in atherosclerosis.

References

- 1.Binder C.J., Chang M.K., Shaw P.X., Miller Y.I., Hartvigsen K., Dewan A., Witztum J.L. Innate and acquired immunity in atherogenesis. Nat. Med. 2002;8:1218–1226. doi: 10.1038/nm1102-1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Libby P. Inflammation in atherosclerosis. Nature. 2002;420:868–874. doi: 10.1038/nature01323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hansson G.K. Inflammation, atherosclerosis, and coronary artery disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;352:1685–1695. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra043430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hansson G.K., Hermansson A. The immune system in atherosclerosis. Nat. Immunol. 2011;12:204–212. doi: 10.1038/ni.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burke J.E., Dennis E.A. Phospholipase A2 structure/function, mechanism, and signaling1. J. Lipid Res. 2009;50:S237–S242. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800033-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakashima S., Kitamoto K., Arioka M. The catalytic activity, but not receptor binding, of sPLA2s plays a critical role for neurite outgrowth induction in PC12 cells. Brain Res. 2004;1015:207–211. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.04.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hayden J.M., Brachova L., Higgins K., Obermiller L., Sevanian A., Khandrika S., Reaven P.D. Induction of monocyte differentiation and foam cell formation in vitro by 7-ketocholesterol. J. Lipid Res. 2002;43:26–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu G., Ma H., Qiu L., Li L., Cao Y., Ma J., Zhao Y. Phenotypic and functional switch of macrophages induced by regulatory CD4+CD25+ T cells in mice. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2011;89:130–142. doi: 10.1038/icb.2010.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pastrana J.L., Sha X., Virtue A., Mai J., Cueto R., Lee I.A., Wang H., Yang X.F. Regulatory T cells and Atherosclerosis. J. Clin. Exp. Cardiolog. 2012;2 doi: 10.4172/2155-9880.S12-002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yamashita T., Sasaki N., Kasahara K., Hirata K. Anti-inflammatory and immune-modulatory therapies for preventing atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. J. Cardiol. 2015;66:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2015.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Foks A.C., Lichtman A.H., Kuiper J. Treating atherosclerosis with regulatory T cells. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2015;35:280–287. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.303568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spitz C., Winkels H., Bürger C., Weber C., Lutgens E., Hansson G.K., Gerdes N. Regulatory T cells in atherosclerosis: Critical immune regulatory function and therapeutic potential. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2016;73:901–922. doi: 10.1007/s00018-015-2080-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ou H.X., Guo B.B., Liu Q., Li Y.K., Yang Z., Feng W.J., Mo Z.C. Regulatory T cells as a new therapeutic target for atherosclerosis. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2018;39:1249–1258. doi: 10.1038/aps.2017.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park S., Baek H., Jung K.H., Lee G., Lee H., Kang G.H., Bae H. Bee venom phospholipase A2 suppresses allergic airway inflammation in an ovalbumin-induced asthma model through the induction of regulatory T cells. Immun. Inflamm. Dis. 2015;3:386–397. doi: 10.1002/iid3.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim H., Lee H., Lee G., Jang H., Kim S.S., Yoon H., Kang G.H., Hwang D.S., Kim S.K., Chung H.S., et al. Phospholipase A2 inhibits cisplatin-induced acute kidney injury by modulating regulatory T cells by the CD206 mannose receptor. Kidney Int. 2015;88:550–559. doi: 10.1038/ki.2015.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jung K.H., Baek H., Kang M., Kim N., Lee S.Y., Bae H. Bee Venom Phospholipase A2 Ameliorates House Dust Mite Extract Induced Atopic Dermatitis Like Skin Lesions in Mice. Toxins. 2017;9:68. doi: 10.3390/toxins9020068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baek H., Lee C.J., Choi D.B., Kim N.S., Kim Y.S., Ye Y.J., Kim J.S., Shim I., Bae H. Bee venom phospholipase A2 ameliorates Alzheimer′s disease pathology in Aβ vaccination treatment without inducing neuro-inflammation in a 3xTg-AD mouse model. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:17369. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-35030-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baek H., Yang H., Lee J.H., Kang N.H., Lee J., Bae H., Hwang D.S. Prophylactic Effects of Bee Venom Phospholipase A2 in Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Pregnancy Loss. Toxins. 2019;11:404. doi: 10.3390/toxins11070404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee G., Bae H. Bee Venom Phospholipase A2: Yesterday’s Enemy Becomes Today’s Friend. Toxins. 2016;8:48. doi: 10.3390/toxins8020048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chung E.S., Lee G., Lee C., Ye M., Chung H.S., Kim H., Bae S.J., Hwang D.S., Bae H. Bee Venom Phospholipase A2, a Novel Foxp3+ Regulatory T Cell Inducer, Protects Dopaminergic Neurons by Modulating Neuroinflammatory Responses in a Mouse Model of Parkinson’s Disease. J. Immunol. 2015;195:4853–4860. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1500386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Milanez-Almeida P., Meyer-Hermann M., Toker A., Khailaie S., Huehn J. Foxp3+ regulatory T-cell homeostasis quantitatively differs in murine peripheral lymph nodes and spleen. Eur. J. Immunol. 2015;45:153–166. doi: 10.1002/eji.201444480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin J., Li M., Wang Z., He S., Ma X., Li D. The role of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells in macrophage-derived foam-cell formation. J. Lipid Res. 2010;51:1208–1217. doi: 10.1194/jlr.D000497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kita T., Yamashita T., Sasaki N., Kasahara K., Sasaki Y., Yodoi K., Takeda M., Nakajima K., Hirata K. Regression of atherosclerosis with anti-CD3 antibody via augmenting a regulatory T-cell response in mice. Cardiovasc. Res. 2014;102:107–117. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvu002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klingenberg R., Gerdes N., Badeau R.M., Gisterå A., Strodthoff D., Ketelhuth D.F., Lundberg A.M., Rudling M., Nilsson S.K., Olivecrona G., et al. Depletion of FOXP3+ regulatory T cells promotes hypercholesterolemia and atherosclerosis. J. Clin. Investig. 2013;123:1323–1334. doi: 10.1172/JCI63891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Landucci E.C., Toyama M., Marangoni S., Oliveira B., Cirino G., Antunes E., de Nucci G. Effect of crotapotin and heparin on the rat paw oedema induced by different secretory phospholipases A2. Toxicon. 2000;38:199–208. doi: 10.1016/S0041-0101(99)00143-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu N.K., Zhang Y.P., Titsworth W.L., Jiang X., Han S., Lu P.H., Shields C.B., Xu X.M. A novel role of phospholipase A2 in mediating spinal cord secondary injury. Ann. Neurol. 2006;59:606–619. doi: 10.1002/ana.20798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Titsworth W.L., Onifer S.M., Liu N.K., Xu X.M. Focal phospholipases A2 group III injections induce cervical white matter injury and functional deficits with delayed recovery concomitant with Schwann cell remyelination. Exp. Neurol. 2007;207:150–162. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim H., Keum D.J., Kwak J., Chung H.S., Bae H. Bee venom phospholipase A2 protects against acetaminophen-induced acute liver injury by modulating regulatory T cells and IL-10 in mice. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e114726. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li D., Lee Y., Kim W., Lee K., Bae H., Kim S.K. Analgesic Effects of Bee Venom Derived Phospholipase A (2) in a Mouse Model of Oxaliplatin-Induced Neuropathic Pain. Toxins. 2015;7:2422–2434. doi: 10.3390/toxins7072422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang Z., Mao S., Zhan Z., Yu K., He C., Wang C. Effect of hyperlipidemia on Foxp3 expression in apolipoprotein E-knockout mice. J. Cardiovasc. Med. 2014;15:273–279. doi: 10.2459/JCM.0b013e3283641b9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li X.-M., Chen J., Dai X., Liao X.-X., Hu C.-L., Li Y.-J. Changes in CD4. Exp. Biol. Med. Maywood. 2017;242:918–925. doi: 10.1177/1535370216689826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wilson P.W. High-density lipoprotein, low-density lipoprotein and coronary artery disease. Am. J. Cardiol. 1990;66:7A–10A. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(90)90562-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rueda C.M., Rodríguez-Perea A.L., Moreno-Fernandez M., Jackson C.M., Melchior J.T., Davidson W.S., Chougnet C.A. High density lipoproteins selectively promote the survival of human regulatory T cells. J. Lipid Res. 2017;58:1514–1523. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M072835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Raffai R.L., Weisgraber K.H. Hypomorphic apolipoprotein E mice: A new model of conditional gene repair to examine apolipoprotein E-mediated metabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:11064–11068. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111222200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]