Abstract

Abstract

Background

HIV prevention interventions which support engagement in care and increased awareness of biomedical options, including pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), are highly desired for disproportionately affected Black/African American, Hispanic/Latinx and gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (GBMSM) populations in the United States (US). However, in almost 40 years of HIV research, few interventions have been developed directly by and for these priority populations in domestic counties most at risk. We submit that interventions developed by early-career scientists who identify with and work directly with affected subgroups, and which include social and structural determinants of health, are vital as culturally tailored HIV prevention and care tools.

Methods

We reviewed and summarized interventions developed from 2007 to 2020 by historically underrepresented early-career HIV prevention scientists in a federally funded research mentoring program. We mapped these interventions to determine which were in jurisdictions deemed as high priority (based on HIV burden) by national prevention strategies.

Results

We summarized 11 HIV interventions; 10 (91%) of the 11 interventions are in geographic areas where HIV disparities are most concentrated and where new HIV prevention and care activities are focused. Each intervention addresses critical social and structural determinants of health disparities, and successfully reaches priority populations.

Conclusion

Focused funding that supports historically underrepresented scientists and their HIV prevention and care intervention research can help facilitate reaching national goals to reduce HIV-related disparities and end the HIV epidemic. Maintaining these funding streams should remain a priority as one of the tools for national HIV prevention.

Keywords: HIV, Historically underrepresented scientists, Interventions, Black/African American, Hispanic/Latinx

Introduction

Although Blacks/African Americans (Blacks thereafter) and Hispanics/Latinxs (Latinxs thereafter) jointly constituted an estimated 31% of the United States (US) population [1], they accounted for an estimated 70% of HIV diagnoses in 2018 [2]. The disparate HIV morbidity and mortality burden among Blacks and Latinxs are seen in each region of the US (although more so in the southern US) and within each major transmission risk category/subgroup, including gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (GBMSM), men, and women of transgender experience, women and men exposed through heterosexual contact, sexually active youth, people who use drugs, and infants exposed through perinatal transmission. In fact, Black/African American GBMSM accounted for 26% of new HIV diagnoses and 37% of new diagnoses among all gay and bisexual men in the US; Hispanic/Latino GBMSM made up 21% of new HIV diagnoses in the US. Efforts to address these alarming HIV-related health disparities have included trainings, mentoring programs, and career development awards designed to help build a more diverse and culturally-experienced scientific and clinical workforce [3–5]. Early-career scientists with a commitment to these communities, particularly historically underrepresented minority scientists, are vital for the development and evaluation of culturally appropriate HIV interventions to reduce HIV disparities.

Recent data underscore that domestic HIV prevention and treatment efforts should be more geographically targeted. During 2016 and 2017, half of the new HIV diagnoses were concentrated in Washington, DC, Puerto Rico and 48 of the 3007 counties in the US [6, 7]. Also in 2017, 52% of HIV diagnoses were in southern states, including several rural southern states, although these states comprise only 38% of the US population [6, 7]. The South accounts for the majority of Blacks newly diagnosed with HIV (63% in 2017) and Blacks living with an HIV diagnosis at the end of 2016 (58%). Among Latinxs, the data are also alarming; 25% of new HIV infections in the US occur among Latinx [8]. Latinx GBMSM are the only subgroup experiencing an increase in new diagnoses compared with other groups in recent years [8, 9].

Several reports underscore that minority scientists’ sociocultural insights and personal commitment augment our collective capacity to develop relevant questions and programs for highly affected communities [3–5, 10–15]. Several senior federal officials suggest that HIV research conducted by investigators who resemble affected communities strengthens the understanding of cultural and contextual issues that may enhance the utility and generalizability of specific findings and interventions [14–16]. For HIV, scientific contributions from Black, Latinx, same-gender loving, and transgender scientists are warranted based on the epidemiology of the domestic HIV epidemic, yet these scientists remain underrepresented [16, 17]. Also, federal data show that research grant applications from investigators of color are less likely to be funded for federal research compared with those from non-Hispanic white peers; targeted scientific research programs that support and mentor historically underrepresented scientists have been suggested as one federal, policy-level solution [18].

Of the diversity-focused HIV training and research programs in the US, one is funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)—The Minority HIV/AIDS Research Initiative (MARI). MARI, funded initially in 2003, is a mentored training program for underrepresented, early-career minority scientists conducting HIV prevention research in highly affected racial/ethnic and sexual minority communities (https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/dhap/eb/mari/index.html). The program is one of the few in the US that assists early-career minority investigators through mentoring, training, and funding to conduct high impact, innovative HIV research and increase diversity of the scientific workforce. It is the only HIV research mentoring program in the US that funds investigators as lead principal investigators (PIs), thus allowing for the necessary protected time, academic support, and hiring of team members to fully implement impactful studies [4]. Details about the program have been published previously [4, 11]. MARI’s annual budget (~ $2 million dollars) is less than 1% of the CDC’s Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention’s annual domestic spending [4]. To date, MARI has been announced as a mentoring grant four times: 2003, 2007, 2011, and 2016, and funded 37 grantees. Previously published MARI reports did not include information about HIV interventions developed by MARI scientists [4, 11]. However, effective interventions have become more vital as the country continues to build on the progress of the first-ever National HIV/AIDS Strategy started in 2010 [19] and towards national HIV prevention goals of “reducing the number of new HIV infections in the United States by 75 percent within five years, and then by at least 90 percent within 10 years, for an estimated 250,000 total HIV infections averted” [6, 7].

In this report, we (1) describe several social and structural determinants of health (SSDoH) that inform disparities in HIV prevention and care in affected communities, particularly in the southern US and among Black and Latinx GBMSM, (2) summarize the HIV prevention and treatment interventions developed or in progress by MARI grantees, and (3) make the case for efforts like MARI in disproportionately affected communities. Dissemination of HIV prevention and care interventions to priority populations is strengthened when those strategies are culturally tailored [20].

Social and Structural Determinants of Health and Disparities in HIV Prevention and Care

As Black and Latinx GBMSM remain disproportionately affected by HIV, especially in high-prevalence geographic areas in the US, most MARI PIs have conducted epidemiologic research to inform efforts that strengthen HIV prevention and care for Black and Latinx GBMSM in these geographic areas. Several reports underscore the impact of SSDoH on GBMSM populations’ prevention and care strategies and the importance of targeting them in interventions, including 2-fold greater odds of Black and Latinx GBMSM having any structural barrier that increases HIV risk (e.g., education; history of incarceration; low income; pervasive racism and discrimination; housing insecurity, homelessness and displacement; anti-immigration policies and laws; unemployment; lack of insurance) [21], the role of self-efficacy, hardiness/adaptive coping/resilience, and effective transition to adulthood in protecting young, GBMSM from HIV-related risks [22–27]; the importance of medical mistrust, of culturally competent clinical services, and Medicaid expansion for HIV-related care among Black GBMSM, especially in the southern US [28]; and the prevalence of stigma, childhood sexual trauma, mental health stressors, including antihomosexual expectations of masculinity and racism for Black and Latinx GBMSM as HIV risk factors, barriers to HIV care and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for prevention [29, 30]. MARI PIs have also focused on Black and Latinx heterosexual youth and the context of family support [31], geographical risks [32], and social-cognitive relationship factors [33] on sexual behaviors and risks. Addressing these SSDoH factors as HIV prevention and care interventions are being developed is a key component to improving their acceptability within some highly affected Black and Latinx communities.

Interventions Developed by MARI Investigators

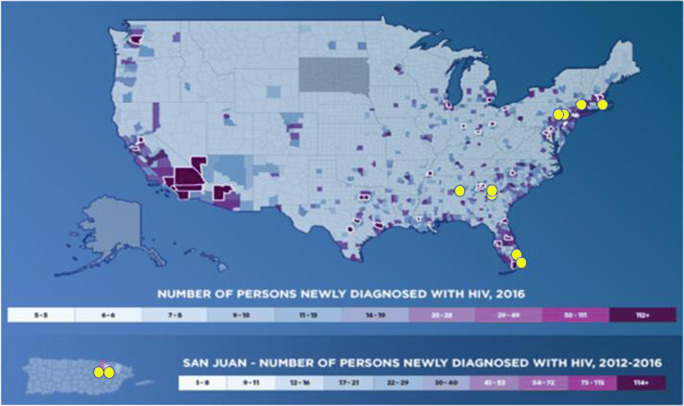

From 2007 to 2020, 11 MARI investigators developed HIV prevention interventions based on primary data collected from persons in affected communities. Importantly, 10 (91%) of the 11 interventions that are being developed or already implemented are in one of the priority 48 counties or seven states based on new HIV diagnoses (see Fig. 1) [6, 7]. Table 1 summarizes the interventions by PI’s names, years of funding, title of the intervention, key publications and presentations that describe the methods of the intervention and/or the main outcome findings, and intervention session details. The interventions (completed and in-progress) are described below. All studies and interventions described were reviewed and approved by each institution’s local or private Internal Review Board (IRB).

Fig. 1.

The 48 highest HIV-burden counties + DC + San Juan, overlayed with the 11 MARI intervention research areas (yellow dots). These 48 counties have the highest burden of HIV. Not highlighted here are the 7 states with substantial rural HIV burden (Alabama, Arkansas, Kentucky, Mississippi, Missouri, Oklahoma and South Carolina). This map is publicly available at: https://aidsvu.org/ending-the-epidemic/. Accessed June 18, 2020

Table 1.

HIV prevention interventions developed by the minority HIV/AIDS research initiative (MARI), 2007–2020

| Principal investigator/years funded/study location | Intervention developed or in-progress | Intervention delivery |

|---|---|---|

|

Guillermo (Willy) Prado/2007–2011 University of Miami—*Miami, FL |

Brief Familias Unidas Publication: Estrada et al., Efficacy of a Brief Intervention to Reduce Substance Use and Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection Risk Among Latino Youth. J Adolesc Health, 2015. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.07.006 |

• 6-week intervention compared with a community practice control condition. • Adolescents were surveyed at 6, 12, and 24 months after baseline. |

|

Yannine Estrada/2011–2016 University of Miami—*Miami, FL |

eFamilias Unidas Publication: Estrada et al. eHealth Familias Unidas: Pilot Study of an Internet Adaptation of an Evidence-Based Family Intervention to Reduce Drug Use and Sexual Risk Behaviors Among Hispanic Adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health, 2017. http://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/14/3/264. |

• Eight parent video groups viewed through the intervention’s website • Four family sessions conducted with an intervention facilitator and parent/adolescent dyads via web-conferencing software |

|

Bridgette Brawner/2011–2016 University of Pennsylvania—*Philadelphia, PA |

Project GOLD: We are Kings and Queens Publication: Brawner et al., The development of an innovative, theory-driven, psychoeducational HIV/STI prevention intervention for heterosexually active Black adolescents with mental illnesses. Vulnerable Child Youth Stud, 2019; 14:2, 151–165. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/17450128.2019.1567962 |

• Manualized curriculum is delivered over 2 days (3 h per day), with eight, 45-min modules, in mixed-gender groups of up to eight participants |

|

Andres Camacho-Gonzalez/2011–2016 Emory University—*Atlanta, GA |

MACARTI Publication: Camacho-Gonzalez, et al., The Metropolitan Atlanta community adolescent rapid testing initiative study: closing the gaps in HIV care among youth in Atlanta, Georgia, USA. AIDS. 2017 Jul 1;31 Suppl 3:S267-S275. |

• Meetings are three times biweekly. The first session is a one-hour encounter to establish rapport, understand participant experience with stigma. • Two weeks later, a second one-hour session is conducted. • Four weeks after the second session, a final 30-min booster session is implemented for positive reinforcement. |

|

Pamela Payne-Foster/2011–2016 University of Alabama—*Tuscaloosa, AL |

Project FAITHH Publication: Payne-Foster et al., Testing our FAITHH: HIV Stigma and Knowledge after a Faith-based HIV Stigma Reduction Intervention in the Rural South, AIDS Care, 30:2, 232–239, 10.1080/09540121.2017.1371664 |

• The eight-module intervention included educational materials, myth-busting exercises to increase accurate HIV knowledge, role-playing, activities to confront stigma, and opportunities to develop and practice delivering a sermon about HIV that included scripture-based content and guidance. |

|

Carlos Rodriguez-Diaz/2011–2016 University of Puerto Rico—*San Juan, Puerto Rico |

Contacto Publication/Presentation: Rodríguez-Díaz, C. E., et al. Feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy of a stigma management intervention for Spanish-speaking HIV-positive gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men. Under review. |

• A one-on-one, a 90 min long intervention with a health educator. • Follow up at 6 weeks and 3 months from baseline. |

|

Sophia Hussen/2016–2020 Emory University—*Atlanta, GA |

Brothers Building Brothers by Breaking Barriers (B6) Publication: Hussen et al., Brothers Building Brothers by Breaking Barriers: development of a resilience-building social capital intervention for young Black gay and bisexual men living with HIV. AIDS Care, 2019, 30:sup4, 51–58. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09540121.2018.1527007. |

• B6 is a group-level intervention that contains 10 modules which can be delivered over 1 or 2 days. |

|

Yzette Lanier/2016–2020 New York University---*NYC (Bronx & Upper Manhattan), NY |

Project YESS! Presentation: Lanier Y, Campo A. The Role of Relationship Characteristics on Use of Combination HIV Prevention Methods Among Young Black And Latino Heterosexual Adolescents And Young Adults. J Adolescent Health. 2019; 64(2):S27-S28. Available at: https://www.jahonline.org/article/S1054-139X(18)30526-3/abstract |

• Intervention development is in progress with direct input from youth in priority populations. |

|

Souhail Malave-Rivera/2016–2020 University of Puerto Rico—*San Juan, Puerto Rico |

Contactos Publication/presentation: Malavé-Rivera SM, et al. Persistent gay and HIV-related stigma among young gay and bisexual men diagnosed with HIV in Puerto Rico. Under review. |

• Three biweekly 2.5-h sessions. • During the first session, through conversations and prompted by open-ended questions and materials, each participant weights the benefits (pros) and costs (cons) for change and identify strengths and challenges to achieve desired change. Each participant develops a personal plan to achieve their goals. • During the following sessions, participants share updates of the steps taken to achieve the proposed goal. |

|

Omar Martinez/2016–2020 Temple University—*Philadelphia, PA |

Connecting Latinos en Pareja Publication: Martinez et al., A couple-based HIV prevention intervention for Latino men who have sex with men: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2018; 19: 218. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5887179/ |

• Four sessions: Session 1 focuses on the personal, cultural and contextual factors that influence risk and protection among couples. Session 2 consists of developing effective communication and goal setting skills, developing couple sexual health plans, and increasing the couple’s motivation to use different prevention technologies. Session 3 focuses on relationship strengthening, identifying and defining unwritten rules, exploring couple’s power and decision-making process, examining triggers to risky sex and developing action plans. It includes skill-building and role play for negotiating HIV protected, safe and fun sex and exploring different prevention alternatives. In session 4, couples identify social support networks and resources within and outside the Latino community that could help them sustain their goals. |

|

Jacob van den Berg/2016–2020 Brown University---Providence, RI |

For HIMM Publication: van den Berg et al., Using eHealth to Reach Black and Hispanic Men Who Have Sex With Men Regarding Treatment as Prevention and Preexposure Prophylaxis: Protocol for a Small Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Res Protoc. 2018; Jul 16;7(7):e11047. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30012549 |

• Social media messages to encourage participants to repeatedly access and engage with the website over the course of the 6-month intervention. |

*One of the 48 counties or 7 states with substantial HIV burden as outlined in “Ending the HIV Epidemic.” (https://files.hiv.gov/s3fs-public/Ending-the-HIV-Epidemic-Counties-and-Territories.pdf)

Completed Interventions

Familias Unidas (Developed in Miami, FL; 2007–2011)

Familias Unidas is a culturally-specific, family-based intervention for Latinx youth and their families. Informed by ecodevelopmental theory [34], Familias Unidas aims to prevent substance use, unprotected sexual behavior, and sexually transmitted infection (STI) incidence by increasing positive parenting, family support of the adolescent, and parental involvement, as well as by improving parent-adolescent communication. Familias Unidas is delivered through family-centered, multi-parent groups that place parents in the change agent role and through family sessions where parents have an opportunity to practice the skills learned in the group sessions with their own youth. Familias Unidas has been evaluated and found to be efficacious and effective in preventing and reducing substance use, externalizing disorders, sexual risk behaviors, internalizing symptoms, and suicidal behavioral outcomes in multiple CDC and NIH funded studies [35–40]. The intervention is listed in a number of evidence-based registries, including CDC’s Compendium of Evidence-based Interventions (Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/research/interventionresearch/compendium/index.html), and is currently being disseminated in other parts of the US and the world including Providence, RI; Chester County, PA; Guayaquil, Ecuador; and Santiago, Chile. Additional Familias Unidas details are available: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/research/interventionresearch/compendium/Familias_Unidas_BEST_RR.pdf.

eHealth Familias Unidas (developed in Miami, FL; 2011–2016) is an online family intervention designed to prevent drug use and sexual risk behaviors (condomless sex) among Latinx adolescents. eHealth Familias Unidas was adapted onto an Internet platform (informed by increased use of the internet and cell phones by priority populations) based on its face-to-face version, Familias Unidas [31, 35, 41]. We tested the efficacy of eHealth Familias Unidas in a randomized controlled trial with 230 Latinx families [42]. Families were assessed and randomized to eHealth Familias Unidas or prevention as usual. Researchers conducted follow-up assessments at 3 and 12 months post-baseline. Positive intervention effects were found for drug use including, past 90 day marijuana use, inhalant use, and prescription drug use. Additionally, the intervention improved family functioning. Intervention effects were not found for condom use. The lack of findings for condom use is likely due to a shorter than normal follow-up period. Previous Familias Unidas trials have found condom use intervention effects at longer follow-ups [43]. eHealth Familias Unidas is currently being tested across pediatric primary care settings via an effectiveness trial.

Project GOLD: We Are Kings and Queens (Developed in Philadelphia, PA; 2011–2016)

Project GOLD was developed in an iterative, community-engaged process to account for the role of mental health and emotion regulation in sexual risk behaviors among heterosexually-active Black youth aged 14 to 17 years [44]. The intent is to build skills to negotiate consistent condom use, limit the number of sexual partners, encourage HIV testing, and promote abstinence as an alternative to unwanted sexual activity. In addition to evidence-based HIV/STI prevention strategies (e.g., condom use technical skills), the activities are rooted in principles of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. This includes fun, interactive strategies to help participants negotiate safer sexual practices—particularly in the face of distorted cognitions and elevated psychological symptoms. Although not statistically significant, compared to the general health condition (n = 56), those in the HIV/STI prevention condition (n = 52) reported a higher proportion of condom use (M = 0.77 vs. M = 0.64) and fewer sexual partners (M = 1.79 vs. M = 4.17) at 3 months. The lack of statistical significance may have been due to the pilot study’s small sample size at the follow-up periods. Future testing in an adequately powered optimization trial is planned. Alongside the intervention activities, the research team established a precedent for youth participation in sexual health research without parental consent to protect their confidentiality and ensure the representative advancement of HIV/STI prevention science [45]. Additional information on Project GOLD is here: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03348813?titles=Project+GOLD&rank=1.

Metropolitan Atlanta Community Adolescent Rapid Testing Initiative (MACARTI) (Developed in Atlanta, GA; 2011–2016)

The MACARTI intervention was designed to utilize non-traditional venue HIV testing, motivational interviewing (MI), and case management (CM) support to increase identification, linkage, and retention in care of newly diagnosed HIV-positive youth between the ages 18–24 years in Atlanta. A formative phase consisted of focus groups with HIV-positive and HIV-negative youth to understand HIV testing preferences and potential venues for testing [46]. Participant responses were used to develop a youth-friendly testing strategy, to select testing sites, and to better characterize post-diagnosis support [47]. During the intervention phase, MACARTI screened 435 participants and identified 49 (11.3%) newly HIV-positive youth. The standard of care arm (SOC) enrolled 49 new HIV-positive individuals for comparison. Overall, 63% were linked within 3 months of diagnosis; linkage was higher for MACARTI compared with SOC (96% vs. 57%, p < 0.001) [48]. Median linkage time for MACARTI participants compared to SOC was 0.39 (IQR: 0.20–0.72) vs. 1.77 (IQR: 1.12–12.65) months (p < 0.001) and MACARTI appointment adherence was higher than SOC (86.1% vs. 77.2%, p = 0.018) [48]. MACARTI successfully identified HIV-positive youth in the community and utilized MI and CM to address behavioral, motivational, and socioeconomic factors that affect HIV care effectively decreasing gaps for youth along the HIV care continuum. After study enrollment, the MACARTI team continued to effectively link and retain an additional 91 newly identified HIV-positive youth.

Project FAITHH (Developed in Tuscaloosa, AL; 2011–2016)

Project Faith-based Anti-stigma Initiative Towards Healing HIV/AIDS (FAITHH) is an HIV stigma-reduction intervention which was developed as a collaborative effort with rural, southern faith leaders from various denominations [49]. We measured HIV-related stigma held by 199 adults (church members) who participated in the intervention (individual-level) and their perception of stigma among other congregants (congregational-level). Analyses of pre- and post-assessments showed the anti-stigma intervention group reported a significant reduction in individual-level stigma compared with the control group (mean difference: − 0.70 intervention vs. − 0.16 control, adjusted p < 0.05) [50]. Engaging faith leaders facilitated the successful tailoring of the intervention, and congregation members were willing participants in the research process. Findings suggest African American churches may be poised to support HIV stigma-reduction efforts. Since 2016, a public website was developed and more than 300 manuals of the intervention have been distributed to HIV service organizations and staff persons, health department officials, and church leaders. Additional information is available at: https://projectfaithh.ua.edu/.

Contacto (Developed in San Juan, Puerto Rico; 2011–2016)

The goal of this intervention was to improve health outcomes (i.e., HIV status or sexual orientation/gender identity disclosure, engagement in healthcare) by addressing the negative impact of social stigma among HIV-positive Spanish-speaking GBMSM. Contacto was developed after formative research with the community [26] and is the first HIV intervention sponsored by CDC completely developed in Spanish for Spanish-speaking populations by bilingual (Spanish and English) and native Spanish-speaking scientists. A total of 109 men participated in the feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy assessment of Contacto. The retention rate of the intervention was 95%. Following a pre-post-post design at 6 weeks (at booster session) and 3 months from baseline, we documented significant reductions in felt-HIV stigma, perceived-gay stigma, internalized gay stigma, and internalized homonegativity (p < 0.05) [51]. Findings also suggest a decrease in depression symptomatology and an increase in HIV disclosure, social support, and overall quality of life. Based on these findings, two iterations of the intervention are being developed: Contactos (group-level) and Contacta-dos (couples-level).

In-Progress Interventions

Brothers Building Brothers by Breaking Barriers (B6) (Developed in Atlanta, GA; 2016–2020)

B6 was developed based on the scientific premise that social capital [52]—defined here as the sum of resources an individual derives from his/her social network—is a significant resilience resource that can improve engagement in care for people living with HIV. The objective of B6 is to increase social capital for young Black gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (YB-GBMSM) who are HIV-positive, as a means to improve care engagement and mental health outcomes. The group-level intervention was developed through an iterative community-based participatory research process [53, 54], in collaboration with a youth advisory board composed of HIV-positive YB-GBMSM and a separate community advisory board composed of local HIV advocates. Rather than focusing exclusively on HIV, B6 takes a holistic approach to supporting YB-GBMSM. Activities aim to explore and affirm Black gay identity, build skills in critical self-reflection, and teach effective communication skills for navigating family, relationships, and clinical and professional settings. B6 is currently being tested in a randomized controlled trial (NCT03664817); 60 participants have gone through the B6 or control condition to date (of a planned 120). In anonymous post-intervention surveys, participants have shared that they enjoyed “meeting new people, gaining new resources”, had fun, learned about themselves, and that their “social network expanded.”

Project YESS! (Youth Engaging in Healthy and Safe Sex; Developed in New York, NY; 2016–2020)

The objective of Project YESS! is to develop a scalable, culturally tailored and developmentally appropriate couple-level intervention to increase uptake of biomedical combination HIV prevention methods (i.e., correct and consistent and correct condom use, STI screening and treatment, routine regular HIV testing and linkage to care, and initiation of and adherence to PrEP) among Black and Latino heterosexual couples living in vulnerable geographic areas. The formative phase consisted of in-depth individual and dyadic interviews and prospective quantitative surveys completed by both couple members. Black and Latino youth aged 16 to 24 and their nominated romantic partners are recruited from the South Bronx and Upper Manhattan, two communities with elevated poverty and high local HIV/STI prevalences [55]. Preliminary findings have led to important insights into the following: (1) the feasibility of engaging adolescent and young adult heterosexual couples in HIV prevention research, (2) characteristics of young couples’ romantic relationships, and (3) individual and interactive effects of social-cognitive and relationship factors on young couples’ sexual behavior and practices [33]. Intervention development is underway.

Contactos (Developed in San Juan, Puerto Rico; 2016–2020)

Contactos is an adaptation from Contacto into a group-level intervention. The adaptation followed the ADAPT-IT [56] model. A total of 32 HIV-positive young GBMSM ages 16 to 29 years, sexually active, Spanish-speakers, and Puerto Rico residents participated in qualitative formative focus groups and interviews [57]. We are implementing the intervention in collaboration with two local community-based organizations (CBOs) that provide LGBT and HIV-related services. Contactos consists of three biweekly 2.5-h sessions. Participants discuss topics regarding their experiences as young GBMSM with HIV, gay and HIV stigmas, healthcare access, and remaining in treatment, among others. MI-trained facilitator and co-facilitator assist participants identifying an area related to their health that they would like to improve or change. To evaluate the objectives of the intervention, participants complete three web-based assessments: (1) prior to the first session, (2) during the last session, and (3) 3 months from baseline (after first session). To date, six participants have completed the intervention.

Connecting Latinos en Pareja (CLP) (Developed in Philadelphia, PA; 2016–2020)

The overall objective of this intervention is to promote healthy relationships among Latino/Latinx, Afro-Latino/Afro-Latinx, and/or Latinx men in same-sex relationships in Philadelphia and surrounding areas [58]. Enrolled male couples receive information, resources, and learn skills with the goal of improving their sexual health, overall well-being, and strengthening their communication. CLP consists of four sessions whose content, scenarios, and examples can be adapted to each couple’s unique circumstances and relative HIV statuses. It incorporates biomedical prevention methods such as pre-exposure prophylaxes (PrEP); promotes engagement in care, adherence to treatment regimens and viral suppression; and encourages routine HIV testing as indicated by the couple’s serostatus. To date, 41 couples have completed intervention sessions and session attendance rates are 100% regardless of condition. Details about the ongoing study are available here: http://latinosenpareja.com/ .

HIV Information for Minority Men or For HIMM (Developed in Providence, RI and Boston, MA; 2016–2020)

For HIMM is a theoretically based eHealth intervention designed to educate HIV-negative and HIV-positive Black and Latinx MSM about PrEP and treatment as prevention (TasP) or Undetectable = Untransmittable (U=U) through the use of social media including Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram [59]. Grounded in the information-motivation-behavioral skills (IMB) and social cognitive theory (SCT) frameworks, For HIMM aims to increase awareness, knowledge, and behavioral intentions towards the use of PrEP and TasP. A culturally tailored interactive website was developed by and for HIV-negative and HIV-positive Black and Latinx MSM along with similarly tailored and IMB/SCT-informed social media messages to encourage these men to repeatedly access and engage with the website over the course of the 6-month intervention. The content and other aspects of the website and social media messages were based heavily on information gathered through focus groups (n = 31 participants; k = 8 focus groups) and cognitive interviews (n = 20 participants) from members of the priority populations. Information on the website in English and in Spanish includes facts about HIV; PrEP and TasP/U=U, and local health care providers who prescribe PrEP or other HIV medications. For HIMM will be tested in an open pilot and a randomized controlled trial (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT03404531). Further information about the website can be found at: www.forhimm.com/ .

Discussion

HIV prevention and care interventions developed and in-progress by MARI early-career scientists have been community-informed, address critical SSDoH disparities, and successfully reach priority populations. Furthermore, these interventions have been focused in geographic areas where HIV disparities are most concentrated and where new HIV prevention and care activities are focused [6, 7]. Early-career scientists, like those supported by MARI, have received training and mentorship that have enabled them to continue as independent investigators committed to advancing the science and public health practice needed to end the HIV epidemic. Continued support and commitment to early-career, historically underrepresented scientists aligns with the shared commitment by federal agencies to invest in innovative ideas, reduce new infections and HIV-related disparities fueled by structural conditions, increase access to care among people living with HIV, and achieve a national coordinated response targeting hardest hit populations in heavily impacted jurisdictions. MARI interventions described in this report are based on primary data collection, which allows for better acceptability with public health partners and affected populations. As such, interventions developed that are found to be effective can greatly strengthen culturally tailored options that are needed for Black and Latinx priority populations.

MARI interventions have addressed and incorporated SSDoH, including internal and external sources of HIV and anti-LGBT stigma, medical mistrust, racial discrimination, anti-immigrant/immigrant rhetoric and policies, mental health and coping, disparate access to education, knowledge, testing and care, social support and capital, adolescent development and cognition, and family support and involvement. Incorporation of these determinants is critical for reaching Black and Latinx priority populations most affected by these SSDoH factors. MARI, through its funding priorities, selection of grantees, and support and mentorship of funded scientists, created opportunities for the development and dissemination of these interventions that has been unparalleled by other existing HIV prevention and care programming. The developed interventions have facilitated and encouraged academic-community partnerships as platforms for implementation science projects to reduce disparities in HIV infection. As an additional example, the COVID-19 pandemic has also highlighted the trickle-down impact of the social and structural determinants on health outcomes among Black and Latinx communities. Opportunities that respond at the intersection of HIV and COVID-19 prevention and treatment are urgently needed, including training the next generation of biobehavioral researchers and supporting capacity building to community-based organizations for pandemics like COVID-19 that hit the disenfranchised the hardest.

Most of the MARI PIs are racial, ethnic and/or sexual minorities historically underrepresented in medicine and public health [4]. More importantly, PIs were competitively selected for their experience with and commitment to working with Black and Latinx priority populations. This experience and commitment have been integral to the development of the culturally appropriate community tailored interventions described above. The importance of cultural competency and representation of racial/ethnic minorities in public health research is well established [60–62].

MARI funding has supported early-career scientists by building on their prior experience and expanding their skill sets through training and mentorship. Therefore, the impact of research initiatives like MARI is far reaching, i.e., long-term career contributions and additional funding for ongoing, innovative HIV prevention, and care research studies. Examples include newly funded studies to address the lack of HIV/HCV co-morbidity interventions in the southern US, dissemination of effective HIV prevention interventions into routine HIV, pediatric and adult care clinical settings in the US, and dissemination of certain strategies developed within Latinx communities to nearby Spanish-speaking countries, if culturally appropriate.

CBOs are critically important to reduce the burden of HIV and ensure long-term success of developed interventions; all MARI interventions in Table 1 included CBO collaborations. Collaborations between MARI PIs and CBOs have been crucial to building greater trust and buy-in from community participants in areas often considered hard-to-reach for scientific research. For example, some of these collaborations included financial support and professional development/capacity building for CBO members. For example, the partnership between Temple University and GALAEI included financial and instructive support by the PI to offset the costs associated with the use of space. In addition, some of these collaborations resulted in training CBO staff on recruitment/engagement strategies, up-to-date data on local HIV epidemiology, and innovative approaches for HIV prevention and treatment. In many cases, we found that the learning was bi-directional, as CBO frontline experiences provided important educational context for the PIs. Furthermore, CBOs which focus on HIV prevention and care are better able to implement interventions that have been developed with community engagement using methods that are culturally aware and sensitive to participant needs. CBOs which directly engage Black and Latinx priority populations often underscore the importance of cultural context for HIV prevention and care interventions when engaging daily with local communities.

HIV disparities impacting Black and Latinx gay, bisexual and other MSM, trans and cisgender women, adolescents and young adults, and other priority populations have been persistent in the US With PrEP, TasP, U=U, and other behavioral and structural interventions, we now have more strategies in our prevention and care toolbox to eliminate these disparities. However, the proper allocation of resources, understanding and incorporation of SSDoH factors, and the effective dissemination and implementation of these tools are vital for these disparities to be addressed and eliminated. MARI has been a cost-effective strategy for developing efficacious and/or effective HIV prevention and care interventions, paving the way for the dissemination of these evidence-based interventions, furthering the science of prevention and treatment in affected communities, and building a culturally competent and diverse scientific and public health workforce. As such, MARI and other similar programmatic and funding strategies remain critical to maximizing the effectiveness of domestic HIV prevention and care efforts in support of ending the HIV epidemic, especially for disproportionately affected communities [6].

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank our study participants for their contribution to research and the broader membership of community-engaged research partnerships that the authors are part of, including community stakeholders living and impacted by HIV infection. Communities are the key to ending the epidemic; affected and impacted communities should assume a major role in planning, developing, and implementing HIV prevention and treatment initiatives.

Authors’ Contributions

All co-authors made substantial contributions to the conception or design of this report; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work; AND helped draft the work or revised it critically for important intellectual content; AND gave final approval of the version to be published; AND agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding

This manuscript was not funded, but describes interventions developed through the Minority HIV/AIDS Research Initiative funded by CDC (2006–2019).

Data Availability

Limited data available from the authors.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Disclaimer

This study declares to be used for non-life science journals.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.2017 American Community Survey Single Year Estimates. U.S. Census Fact Finder. American Community Survey. Available at: https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-kits/2018/acs-1year.html. Accessed 29 Oct 2020.

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report, 2018; vol. 31. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance/vol-31/index.html. Published May 2020. Accessed 29 Oct 2020.

- 3.Fernández MI, Wheeler DP, Alfonso SV. Embedding HIV mentoring programs in HIV research networks. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(Suppl 2):281–287. doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1367-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sutton MY, Lanier YA, Willis LA, Castellanos T, Dominguez K, Fitzpatrick L, Miller KS. Strengthening the network of mentored, underrepresented minority scientists and leaders to reduce HIV-related health disparities. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(12):2207–2214. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dolcini MM, Reznick OAG, Marin BV. Investments in the future of behavioral science: the University of California, San Francisco, Visiting professors program. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(suppl 1):S43–S47. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.121301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fauci AS, Redfield RR, Sigounas G, Weahkee MD, Giroir BP. Ending the HIV epidemic: a plan for the United States. JAMA. 2019;321(9):844–845. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.HIV.gov. Ending the HIV epidemic: a plan for America. Available at: https://www.hiv.gov/federal-response/ending-the-hiv-epidemic/overview. Accessed 18 June 2020.

- 8.CDC Fact Sheet. HIV among Latinos. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/docs/factsheets/cdc-hiv-latinos-508.pdf. Accessed 18 June 2020.

- 9.McCree DH, Walker T, DiNenno E, et al. A programmatic approach to address increasing HIV diagnoses among Hispanic/Latino MSM, 2010-2014. Prev Med. 2018;114:64–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marín BV, Diaz RM. Collaborative HIV prevention research in minority communities program: a model for developing investigators of color. Public Health Rep. 2002;117(3):218–230. doi: 10.1093/phr/117.3.218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fitzpatrick LK, Sutton M, Greenberg AE. Toward eliminating health disparities in HIV/AIDS: the importance of the minority investigator in addressing scientific gaps in Black and Latino communities. J Natl Med Assoc. 2006;98(12):1906–1911. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wyatt GE, Williams JK, Henderson T, Sumner L. On the outside looking in: promoting HIV/AIDS research initiated by African American investigators. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(suppl 1):S48–S53. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.131094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walters KL, Simoni JM, Evans-Campbell TT, et al. Mentoring the mentors of underrepresented racial/ethnic minorities who are conducting HIV research: beyond cultural competency. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(Suppl 2):288–293. doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1491-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stoff DM, Cargill VA. Building a more diverse workforce in HIV/AIDS research: the time has come. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(Suppl 2):222. doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1501-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sullivan Commission on Diversity in the Healthcare Workforce. Missing persons: minorities in the health professions. Washington, DC. 2004. Available at: https://campaignforaction.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/SullivanReport-Diversity-in-Healthcare-Workforce1.pdf. Accessed 29 Oct 2020.

- 16.Stoff DM, Cargill VA. Future HIV mentoring programs to enhance diversity. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(Suppl 2):318–325. doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1502-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scheim AI, Appenroth MN, Beckham SW, Goldstein Z, Grinspan MC, Keatley JAG, Radix A. Transgender HIV research: nothing about us without us. Lancet HIV. 2019;6(9):e566–e567. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(19)30269-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ginther DK, Shaffer WT, Schnell J, et al. Race, ethnicity and NIH awards. Science. 2011;333:1015–1019. doi: 10.1126/science.1196783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.HIV.gov. National HIV/AIDS strategy: updated to 2020. Available at: https://www.hiv.gov/federal-response/national-hiv-aids-strategy/nhas-update. Accessed 29 Oct 2020.

- 20.Airhihenbuwa CO, Ford CL, Iwelunmor JI. Why culture matters in health interventions: lessons from HIV/AIDS stigma and NCDs. Health Educ Behav. 2014;41(1):78–84 https://sph.umd.edu/sites/default/files/files/Why%20Culture%20Matters%20HEB.pdf. Accessed 29 Oct 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Millett GA, Peterson JL, Flores SA, Hart TA, Jeffries WL, 4th, Wilson PA, Rourke SB, Heilig CM, Elford J, Fenton KA, Remis RS. Comparisons of disparities and risks of HIV infection in black and other men who have sex with men in Canada, UK, and USA: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2012;380(9839):341–348. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60899-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilson PA, Meyer IH, Antebi-Gruszka N, Boone MR, Cook SH, Cherenack EM. Profiles of resilience and psychosocial outcomes among young Black gay and bisexual men. Am J Commun Psychol. 2016;57:144–157. doi: 10.1002/ajcp.12018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hussen SA, Andes K, Gilliard D, Chakraborty R, del Rio C, Malebranche DJ. Transition to adulthood and antiretroviral adherence among HIV-positive young Black men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(4):725–731. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.301905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martinez O, Arreola S, Wu E, Muñoz-Laboy M, Levine EC, Rutledge SE, Hausmann-Stabile C, Icard L, Rhodes SD, Carballo-Diéguez A, Rodríguez-Díaz CE, Fernandez MI, Sandfort T. Syndemic factors associated with adult sexual HIV risk behaviors in a sample of Latino men who have sex with men in New York City. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;166(1):258–262. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.06.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muñoz-Laboy M, Martinez O, Levine EC, Mattera BT, Fernandez MI. Syndemic conditions reinforcing disparities in HIV and other STIs in an urban sample of behaviorally bisexual Latino men. J Immigr Minor Health. 2018;20(2):497–501. doi: 10.1007/s10903-017-0568-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ortiz-Sánchez EJ, Rodríguez-Díaz CE, Jovet-Toledo GG, Santiago-Rodríguez EI, Vargas-Molina RL, Rhodes SD. Sexual health knowledge and stigma in a community sample of HIV-positive gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men in Puerto Rico. J HIV AIDS Soc Serv. 2017;16(2):143–153. doi: 10.1080/15381501.2016.1169467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wilson P, Nanin J, Amesty S, Wallace S, Cherenack E, Fullilove R. Using syndemic theory to understand vulnerability to HIV infection among Black and Latino men in New York City. J Urban Health. 2014;91(5):983–998. doi: 10.1007/s11524-014-9895-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cahill S, Taylor SW, Elsesser SA, Mena L, Hickson D, Mayer KH. Stigma, medical mistrust, and perceived racism may affect PrEP awareness and uptake in black compared to white gay and bisexual men in Jackson, Mississippi and Boston, Massachusetts. AIDS Care. 2017;29:1351–1358. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2017.1300633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levine EC, Martinez O, Mattera B, Wu E, Arreola S, Rutledge SE, Newman B, Icard L, Muñoz-Laboy M, Hausmann-Stabile C, Welles S, Rhodes SD, Dodge BM, Alfonso S, Fernandez MI, Carballo-Diéguez A. Child sexual abuse and adult mental health, sexual risk behaviors, and drinking patterns among Latino men who have sex with men. J Child Sex Abus. 2018;27(3):237–253. doi: 10.1080/10538712.2017.1343885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fields EL, Bogart LM, Smith KC, Malebranche DJ, Ellen J, Schuster MA. “I always felt I had to prove my manhood”: homosexuality, masculinity, gender role strain, and HIV risk among young Black men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health. 2015;105:122–131. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prado G, Pantin H, Huang S, Cordova D, Tapia MI, Velazquez MR, Calfee M, Malcolm S, Arzon M, Villamar J, Jimenez GL, Cano N, Brown CH, Estrada Y. Effects of a family intervention in reducing HIV risk behaviors among high-risk Hispanic adolescents: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166(2):127–133. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brawner BM, Guthrie B, Stevens R, Taylor L, Eberhart M, Schensul JJ. Place still matters: racial/ethnic and geographic disparities in HIV transmission and disease burden. J Urban Health. 2017;94(5):716–729. doi: 10.1007/s11524-017-0198-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lanier Y, Campo A. The role of relationship characteristics on use of combination HIV prevention methods among young Black and Latino heterosexual adolescents and young adults. J Adolesc Health. 2019;64(2):S27–8 Available at: https://www.jahonline.org/article/S1054-139X(18)30526-3/abstract. Accessed 29 Oct 2020.

- 34.Szapocznik J, Coatsworth JD. An ecodevelopmental framework for organizing the influences on drug abuse: a developmental model of risk and protection. In: Glantz M, Hartel CR, editors. Drug abuse: Origins and interventions. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1999. pp. 331–366. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Estrada Y, Lee TK, Huang S, Tapia MI, Velázquez MR, Martinez MJ, Pantin H, Ocasio MA, Vidot DC, Molleda L, Villamar J, Stepanenko BA, Brown CH, Prado G. Parent-centered prevention of risky behaviors among Hispanic youths in Florida. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(4):607–613. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Estrada Y, Rosen A, Huang S, Tapia M, Sutton M, Willis L, Quevedo A, Condo C, Vidot DC, Pantin H, Prado G. Efficacy of a brief intervention to reduce substance use and Human Immunodeficiency Virus infection risk among Latino youth. J Adolesc Health. 2015;57(6):651–657. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Molleda L, Estrada Y, Kyoung Lee T, et al. Short term effects on family communication and adolescent conduct problems: Familias Unidas in Ecuador. Prev Sci. 2017;18(7):783–792. doi: 10.1007/s11121-016-0744-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Perrino T, Pantin H, Huang S, Brincks A, Brown CH, Prado G. Reducing the risk of internalizing symptoms among high-risk Hispanic youth through a family intervention: a randomized controlled trial. Fam Process. 2016;55(1):91–106. doi: 10.1111/famp.12132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Prado G, Pantin H, Briones E, Schwartz SJ, Feaster D, Huang S, Sullivan S, Tapia MI, Sabillon E, Lopez B, Szapocznik J. A randomized controlled trial of a family-centered intervention in preventing substance use and HIV risk behaviors in Hispanic adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2007;75:914–926. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.6.914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vidot D, Huang S, Poma S, Estrada Y, Lee T, Prado G. Familias Unidas’ cross-over effects on suicidal behaviors among Hispanic adolescents: results from an effectiveness trial. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2016;46(2):S8–S14. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Prado G, Huang S, Córdova D, et al. The efficacy of Familias Unidas on drug and alcohol outcomes for Hispanic delinquent youth: main effects and interaction effects by parental stress and social support. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;125:S18–S25. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Estrada Y, Lee TK, Wagstaff R, M. Rojas L, Tapia MI, Velázquez MR, Sardinas K, Pantin H, Sutton MY, Prado G. eHealth Familias Unidas: efficacy trial of an evidence-based intervention adapted for use on the internet with Hispanic families. Prev Science. 2019;20:68–77. doi: 10.1007/s11121-018-0905-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pantin H, Prado G, Lopez B, Huang S, Tapia MI, Schwartz SJ, Sabillon E, Brown CH, Branchini J. A randomized conrolled trial of Familias Unidas for Hispanic adolescents with behavior problems. Psychosom Med. 2009;71:987–995. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181bb2913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brawner BM, Abboud S, Reason J, Wingood G, Jemmott LS. The development of an innovative, theory-driven, psychoeducational HIV/STI prevention intervention for heterosexually active black adolescents with mental illnesses. Vulnerable Child Youth Stud. 2019;14(2):151–165. doi: 10.1080/17450128.2019.1567962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brawner BM, Sutton MY. Sexual health research among youth representing minority populations: to waive or not to waive parental consent. Ethics Behav. 2017;28(7):544–559. doi: 10.1080/10508422.2017.1365303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Camacho-Gonzalez AF, Wallins A, Toledo L, Murray A, Gaul Z, Sutton MY, Gillespie S, Leong T, Graves C, Chakraborty R. Risk factors for HIV transmission and barriers to HIV disclosure: metropolitan Atlanta youth perspectives. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2016;30:18–24. doi: 10.1089/apc.2015.0163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Murray A, Hussen SA, Toledo L, Thomas-Seaton LT, Gillespie S, Graves C, Chakraborty R, Sutton MY, Camacho-Gonzalez AF. Optimizing community-based HIV testing and linkage to care for young persons in Metropolitan Atlanta. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2018;32:234–240. doi: 10.1089/apc.2018.0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Camacho-Gonzalez AF, Gillespie SE, Thomas-Seaton L, Frieson K, Hussen SA, Murray A, Gaul Z, Leong T, Graves C, Sutton MY, Chakraborty R. The Metropolitan Atlanta community adolescent rapid testing initiative study: closing the gaps in HIV care among youth in Atlanta, Georgia. USA AIDS. 2017;31(Suppl 3):S267–S275. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bradley ELP, Sutton MY, Cooks E, Washington-Ball B, Gaul Z, Gaskins S, Payne-Foster P. Developing FAITHH: methods to develop a faith-based HIV stigma-reduction intervention in the rural south. Health Promot Pract. 2018;19(5):730–740. doi: 10.1177/1524839917754044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Payne-Foster P, Bradley ELP, Aduloju-Ajijola N, Yang X, Gaul Z, Parton J, Sutton MY, Gaskins S. Testing our FAITHH: HIV stigma and knowledge after a faith-based HIV stigma reduction intervention in the rural south. AIDS Care. 2018;30:232–239. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2017.1371664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rodríguez-Díaz CE, et al. Feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy of a stigma management intervention for Spanish-speaking HIV-positive gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men. Under review.

- 52.Bourdieu P. The forms of capital. In: Richardson JE, editor. Handbook of theory of research for the sociology of education. Westport: Greenwood Press; 1986. pp. 241–258. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hussen SA, Easley KA, Smith JC, Shenvi N, Harper GW, Camacho-Gonzalez AF, Stephenson R, del Rio C. Social capital, depressive symptoms and HIV viral suppression among young Black, gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men living with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(9):3024–3032. doi: 10.1007/s10461-018-2105-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hussen SA, Jones M, Moore S, et al. Brothers building brothers by breaking barriers: development of a resilience-building social capital intervention for young black gay and bisexual men living with HIV. AIDS Care. 2018;30(sup4):51–58. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2018.1527007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.New York City: Community Health. New York City Community Health Profiles Atlas. 2015. https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/doh/downloads/pdf/data/2015_CHP_Atlas.pdf. Accessed 18 June 2020.

- 56.Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ. The ADAPT-ITT model: a novel method of adapting evidence-based HIV interventions. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;47(Suppl 1):S40–S46. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181605df1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Malavé-Rivera SM, Santiago-Rodríguez EI, Vargas-Molina RL, Arroyo-Andujar LA, Martínez-Lozano M, Rodríguez-Díaz CE. Persistent gay and HIV-related stigma among young gay and bisexual men diagnosed with HIV in Puerto Rico. Under review.

- 58.Martinez O, Isabel Fernandez M, Wu E, Carballo-Diéguez A, Prado G, Davey A, Levine E, Mattera B, Lopez N, Valentin O, Murray A, Sutton M. A couple-based HIV prevention intervention for Latino men who have sex with men: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2018;19(1):218. 10.1186/s13063-018-2582-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 59.van den Berg JJ, Silverman T, Fernandez MI, Henny KD, Gaul ZJ, Sutton MY, Operario D. Using eHealth to reach Black and Hispanic men who have sex with men regarding treatment as prevention and preexposure prophylaxis: protocol for a small randomized controlled trial. JMIR Res Protoc. 2018;7(7):e11047. doi: 10.2196/11047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wyatt GE. Enhancing cultural and contextual intervention strategies to reduce HIV/AIDS among African Americans. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(11):1941–1945. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.152181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vermund SH, Hamilton EL, Griffith SB, Jennings L, Dyer TV, Mayer K, Wheeler D. Recruitment of underrepresented minority researchers into HIV prevention research: the HIV Prevention Trials Network Scholars Program. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 2018;34:171–177. doi: 10.1089/aid.2017.0093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Brickley DB, Lindan CP. AIDS prevention research: training and mentoring the next generation of investigators from low- and middle-income countries. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(Supp 1):1–3. doi: 10.1007/s10461-018-2189-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Limited data available from the authors.