Increasing evidence accumulated from the past year on the outbreak of corona virus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, suggesting a strong association between the severe acute respiratory syndrome corona virus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection and autoimmunity. The reported inflammatory/autoimmune-related symptoms by patients, the appearance of circulating autoantibodies and the diagnosis of defined diverse autoimmune diseases in a subgroup of SARS-CoV-2-infected patients, indicate the critical and pivotal effect of SARS-CoV-2 virus on human immunity, and its capability to trigger autoimmune disorders, in genetically predispose subjects.

1. Hyperstimulation of the immune system: cytokine storm and hyperferritinemia

Severe cases of COVID-19 disease are characterized by fever, hyperferritinemia and a massive production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (‘cytokine storm’), which may lead to a high rate of mortality [[1], [2], [3]]. Cytokine storm phenomenon in severe SARS-CoV-2 infected patients have been thoroughly explored and reported in COVID-19 critical ill patients [4,5]. Macrophages, account to be one of the main immune population which resides in the lung parenchyma, has been suggested to have a critical role in the pathophysiology of SARS-CoV-2-induced acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and life-threating-related manifestations in critically severe patients. SARS-CoV-2 may trigger hyperstimulation of the immune system [6] in genetically predispose subjects which may lead to over activation of local macrophages to produce high level of inflammatory mediators such as: cytokines, chemokines and ferritin. Overproduction of cytokines by macrophages has been shown to enhance the inflammatory process and to trigger unusually large amount of ferritin in the blood (‘hyperferritenemia’) [[7], [8], [9]]. Importantly, it was shown recently that on admission to hospitals, SARS-CoV-2 infected patients have high level of ferritin [10,11]. In light with this, it is worth mentioning that cytokine storm and hyperferitenemia have been previously shown to be triggered by other pathogenic viruses such as influenza and dengue [10,12].

2. Autoantibodies reported in COVID-19 patients

2.1. Anti-nuclear antibodies in SARS-CoV-2-infected patients

On May 2020, Gazzaruso et al. showed the prevalence of autoimmune markers such as: anti-nuclear autoantibodies (ANA) (35.6%) and lupus anti-coagulant (11.1%) in 45 patients admitted to the hospital for SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia. Furthermore, on August 2020, Fujii et al. reported a case-based review of two patients with severe respiratory failure due to COVID-19 who had high of anti-SSA/Ro antibody titer [13]. These finding clearly suggest an autoimmune response in these patients.

2.2. Antiphospholipid antibodies in SARS-CoV-2-infected patients

Antiphospholipid (aPL) profile study have been conducted in critically ill COVID-19 patients and showed that 10 out of 19 patients (52.6%) had serum anti-cardiolipin (aCL) and/or anti-β2 glycoprotein 1 (aβ2GP1) autoantibodies, while 7 out of these 10 patients had multiple isotypes of aPLs [14]. The presence of these antibodies, together with elevated factor VIII (FVIII), has been attributed to hypercoagulation in these critically ill patients.

2.3. Anti-IFN antibodies in SARS-CoV-2-infected patients

A study, recently published by Bastard et al. shows that neutralizing IgG auto-antibodies against type I IFNs where found in patients with a life threatening COVID-19 infection [15]. Importantly, these antibodies have the capabilities to abrogate the ability of the corresponding type I IFNs to block SARS-CoV-2 infection in vitro.

2.4. Anti-MDA5 antibodies in SARS-CoV-2-infected patients

Another example of the appearance of potentially pathogenic autoantibodies in SARS-CoV-2-infected patients is the anti-MDA5 autoantibodies. The melanoma differentiation-associated protein 5 (MDA5) is a receptor capable of detecting different type of RNA molecules [16]. Antibodies against MDA5 have been shown to be associated with amyopathic dermatomyositis, which is a rare disease in a global scale [17]. Dermatomyositis associated with MDA5 is recently being discussed as for its epidemiologic, biomarkers and pathological aspects of tissue damage that have resemblance to a SARS-CoV-2 infection [18]. Indeed, in an online pre-print study from China, the authors study the production of circulating autoantibodies against MDA5 in SARS-CoV-2-infected patients as compared with healthy controls and found that 132/274 patients (48.2%) had positive titer of Anti-MDA5 antibody, and this antibody tended to represent with severe cases and in non-survivals subjects (medrxviv; doi:https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.29.20164780).

The above mention findings regarding autoantibodies production in SARS-CoV-2 infected patients (Table 1 ), strengthen our belief on the possibility that there could be potentially additional autoantibodies present in similar patients, and these autoantibodies might have a pivotal role in the pathophysiology of severe and life-threating manifestations in COVID-19 patients.

Table 1.

A list of autoimmune diseases and autoantibodies associated with COVID-19 infection.

| Autoimmune disease/syndromes secondary to COVID-19 infection | Circulating autoantibodies reported in COVID-19 patients |

|---|---|

| Guillain-Barré syndrome | Anti-nuclear antibodies (ANA) |

| Miler Fisher Syndrome (MFS) | Anti-cardiolipin (aCL) antibodies |

| Antiphospholipid syndrome | Anti-β2 glycoprotein 1 (aβ2GP1) antibodies |

| Immune thrombocytopaenic purpura | Anti-MDA5 antibodies |

| systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) | Anti RBC antibodies (direct anti globulin) |

| Kawasaki disease | LAC –lupus anticoagulant |

| Cold agglutinin disease & autoimmune hemolytic anemia | Antiprothrombin IgM |

| Neuromyelitis optica | Antiphosphatidylserine IgM/IgG |

| NMDA-receptor encephalitis | Antiannexin V IgM/IgG |

| Myasthenia gravis | Anti-GD1b antibodies |

| Type I diabetes | Anti-heparin PF4 complex antibody |

| Large vessel vasculitis & thrombosis | pANCA AND cANCA |

| Psoriasis | Anti-CCP antibodies |

| Subacute thyroiditis | |

| Graves' disease | |

| Sarcoidosis | |

| Inflammatory arthritis |

2.5. Potential anti-Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) autoantibodies in SARS-CoV-2-infected patients

Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) is an important physiological protein that is catalyzing the hydrolysis of angiotensin II into angiotensin [[1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7]], thus regulating the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system. In addition, ACE2 acts as the SARS-CoV-2 receptor for its entrance into cells, thus it is a necessary component in the pathophysiology of COVID-19. Importantly, ACE2 also exists in a soluble form (sACE2) in the extracellular fluid and in the blood, and acts as an inactivator protein of SARS-CoV-2, similarly to other pathogenic viruses. As a result of the high affinity between SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and ACE2, formation of SARS-CoV-2-sACE2 complex occurs, that could potentially lead to the formation of autoantibodies against ACE2.

3. COVID-19 infection in genetically susceptible human subjects: association with HLA gene polymorphism

The human leukocyte antigen (HLA) gene and its polymorphism have been described to be associated with the development of various autoimmune diseases/disorders [19]. Recently, researchers are trying to understand how human genetics may affect the spreading and contagion of the current SARS-Cov-2 virus. As for the above mention evidence for the association between the SARS-Cov-2 virus and autoimmunity, it is not surprising that scientist explored a strong association between covid-19 and HLA genetic polymorphisms [[20], [21], [22]].

4. Sharing peptides between SARS-CoV-2 virus and Human antigens: implication for the upcoming vaccine against COVID-19

Molecular mimicry phenomena between pathogenic viruses and human proteins - have been already analyzed and suggested to play a major role in the etiologies of various inflammatory and autoimmune diseases [23,24]. We recently have been thoroughly quantifying hexa- and heptapeptide sharing of SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein with mammalian proteomes and found that a massive heptapeptide sharing exist between SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein and human proteins [25]. This study highlights the possibility of molecular mimicry–induced adverse autoimmune-related manifestations, already reported in SARS-CoV-2-infected patients, and raise concern regarding the upcoming desired vaccine, indicating the need for vaccines based on minimal immune determinants unique to pathogens and absent in the human proteome [26]. With regard to the concern of future post COVID-19 vaccine-related autoimmune manifestations, it is worth to mention the recent reports regarding participants who developed symptoms of transverse myelitis, an inflammation of the spinal cord (already reported secondary to COVID-19 infection [27]) – in the trial assessing the safety and efficacy of COVID-19 vaccine by AstraZeneca company.

5. The development of autoimmune diseases secondary to COVID-19 infection

Our group and colleagues have comprehensively investigating and reporting the association between various common pathogenic viruses such as: Parvovirus B19, Epstein-Barr-virus (EBV), Cytomegalovirus (CMV), Herpes virus-6, HTLV-1, Hepatitis A and C virus, and Rubella virus, with the development of chronic inflammatory and autoimmune diseases [[28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33]]. In light with this observations, we recently review the appearance of autoimmune diseases/disorders reported to be triggered by the SARS-CoV-2 infection [34] (Table 1). Autoimmune disorders such as: Guillain-Barré syndrome [35,36], Miler Fisher Syndrome (MFS) [37], Antiphospholipid syndrome [14], Immune thrombocytopaenic purpura [38,39], systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) [40] and Kawasaki disease [41,42] – have been reported in patients with COVID-19 infection.

6. Loss of smell in SARS-CoV-2-infected patients and in autoimmune disease

We previously showed that olfactory dysfunction can be seen in a number of autoimmune diseases such as: SLE, multiple sclerosis and myasthenia gravis (MG) [[43], [44], [45]]. As for the above mention clear association between autoimmunity and the current COVID-19 pandemic, the recent observation of high prevalence of olfactory dysfunction, especially in the early presentation in COVID-19 patients - is not surprising [46].

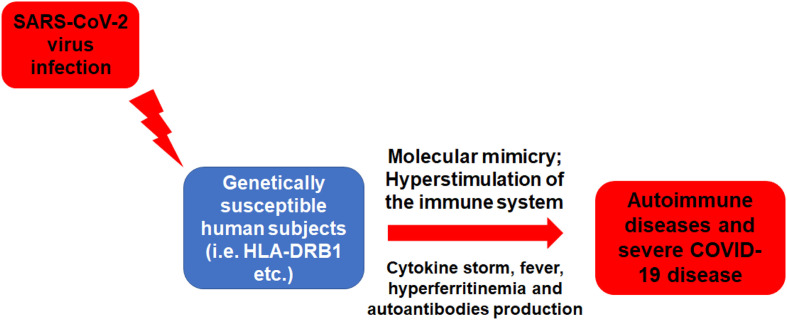

7. COVID-19 infection as a classical example of ASIA syndrome

Overall, the above mentioned suggested link between SARS-CoV-2 infection and autoimmunity (Fig. 1 ) can be demonstrated by the concept of autoimmune/inflammatory syndrome induced by adjuvants (ASIA syndrome), which was introduced by our group in 2011 to gather all autoimmune phenomena that emerged following the exposure to an external stimulus (such as: infections, adjuvant, vaccine and silicone) [6,47]. With this regard, a virus infection such as the SARS-CoV-2 can trigger: i) a strong activation of the immune system; ii) the appearance of ‘typical’ clinical manifestations such as: myalgia, myositis, arthralgia, chronic fatigue, sleep disturbances, neurological manifestations, cognitive impairment, memory loss and pyrexia – all of which already reported in SARS-CoV-2 –infected patients; iii) the appearance of autoantibodies, which may lead to the development of autoimmune diseases in genetically predispose subjects (i.e. HLA-DRB1 etc.). Therefore, the current COVID-19 pandemic indeed fulfills almost all the major and minor criteria for ASIA syndrome [47].

Fig. 1.

The development of autoimmune diseases following SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgement

This work is supported by the grant of the Government of the Russian Federation for the state support of scientific research carried out under the supervision of leading scientists, agreement 14.W03.31.0009.

References

- 1.Ruscitti P., Berardicurti O., Barile A., Cipriani P., Shoenfeld Y., Iagnocco A. Severe COVID-19 and related hyperferritinaemia: more than an innocent bystander? Ann Rheum Dis. 2020 Nov;79(11):1515–1516. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-217618. (PubMed PMID: 32434816) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ruscitti P., Berardicurti O., Di Benedetto P., Cipriani P., Iagnocco A., Shoenfeld Y. Severe COVID-19, another piece in the puzzle of the hyperferritinemic syndrome an immunomodulatory perspective to alleviate the storm front. Immunol. 2020;11:1130. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01130. (PubMed PMID: 32574264. Pubmed Central PMCID: PMC7270352) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shoenfeld Y. Corona (COVID-19) time musings: our involvement in COVID-19 pathogenesis, diagnosis, treatment and vaccine planning. Autoimmun Rev. 2020 Jun;19(6):102538. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2020.102538. (PubMed PMID: 32268212. Pubmed Central PMCID: 7131471) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mangalmurti N., Hunter C.A. Cytokine storms: understanding COVID-19. Immunity. 2020 Jul 14;53(1):19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.06.017. (PubMed PMID: 32610079. Pubmed Central PMCID: 7321048) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mehta P., McAuley D.F., Brown M., Sanchez E., Tattersall R.S., Manson J.J. COVID-19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet. 2020 Mar 28;395(10229):1033–1034. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30628-0. (PubMed PMID: 32192578. Pubmed Central PMCID: PMC7270045) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Watad A., Bragazzi N.L., Amital H., Shoenfeld Y. Hyperstimulation of adaptive immunity as the common pathway for silicone breast implants, autoimmunity, and lymphoma of the breast. Isr Med Assoc J. 2019 Aug;21(8):517–519. (PubMed PMID: 31474010) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gomez-Pastora J., Weigand M., Kim J., Wu X., Strayer J., Palmer A.F. Hyperferritinemia in critically ill COVID-19 patients - is ferritin the product of inflammation or a pathogenic mediator? Clinica chimica acta; international journal of clinical chemistry. Oct. 2020;509:249–251. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2020.06.033. (PubMed PMID: 32579952. Pubmed Central PMCID: 7306200) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vlahakos V.D., Marathias K.P., Arkadopoulos N., Vlahakos D.V. 2020 Sep 3. Hyperferritinemia in patients with COVID-19: An opportunity for iron chelation? Artificial organs. (PubMed PMID: 32882061) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosario C., Zandman-Goddard G., Meyron-Holtz E.G., D’Cruz D.P., Shoenfeld Y. The hyperferritinemic syndrome: macrophage activation syndrome, Still’s disease, septic shock and catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome. BMC Med. 2013 Aug 22;11:185. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-185. (PubMed PMID: 23968282. Pubmed Central PMCID: 3751883) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lalueza A., Ayuso B., Arrieta E., Trujillo H., Folgueira D., Cueto C. Elevation of serum ferritin levels for predicting a poor outcome in hospitalized patients with influenza infection. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020 Feb;28 doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.02.018. (PubMed PMID: 32120038) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dahan S., Segal G., Katz I., Hellou T., Tietel M., Bryk G. Ferritin as a marker of severity in COVID-19 patients: a fatal correlation. Isr Med Assoc J. 2020 Aug;8(22):429–434. (PubMed PMID: 32812717) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Soundravally R., Agieshkumar B., Daisy M., Sherin J., Cleetus C.C. Ferritin levels predict severe dengue. Infection. 2015 Feb;43(1):13–19. doi: 10.1007/s15010-014-0683-4. (PubMed PMID: 25354733) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fujii H., Tsuji T., Yuba T., Tanaka S., Suga Y., Matsuyama A. High levels of anti-SSA/Ro antibodies in COVID-19 patients with severe respiratory failure: a case-based review: high levels of anti-SSA/Ro antibodies in COVID-19. Clin Rheumatol. 2020 Nov;39(11):3171–3175. doi: 10.1007/s10067-020-05359-y. (PubMed PMID: 32844364. Pubmed Central PMCID: 7447083) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang Y., Cao W., Jiang W., Xiao M., Li Y., Tang N. Profile of natural anticoagulant, coagulant factor and anti-phospholipid antibody in critically ill COVID-19 patients. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2020 Oct;50(3):580–586. doi: 10.1007/s11239-020-02182-9. (PubMed PMID: 32648093. Pubmed Central PMCID: 7346854) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bastard P., Rosen L.B., Zhang Q., Michailidis E., Hoffmann H.H., Zhang Y. Auto-antibodies against type I IFNs in patients with life-threatening COVID-19. Science. 2020 Sep;24 doi: 10.1126/science.abd4585. (PubMed PMID: 32972996) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kato H., Takeuchi O., Sato S., Yoneyama M., Yamamoto M., Matsui K. Differential roles of MDA5 and RIG-I helicases in the recognition of RNA viruses. Nature. 2006 May 4;441(7089):101–105. doi: 10.1038/nature04734. (PubMed PMID: 16625202) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoshino K., Muro Y., Sugiura K., Tomita Y., Nakashima R., Mimori T. Anti-MDA5 and anti-TIF1-gamma antibodies have clinical significance for patients with dermatomyositis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2010 Sep;49(9):1726–1733. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keq153. (PubMed PMID: 20501546) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Lorenzis E., Natalello G., Gigante L., Verardi L., Bosello S.L., Gremese E. What can we learn from rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease related to anti-MDA5 dermatomyositis in the management of COVID-19? Autoimmun Rev. 2020 Sep;14:102666. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2020.102666. (PubMed PMID: 32942036. Pubmed Central PMCID: PMC7489246) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arango M.T., Perricone C., Kivity S., Cipriano E., Ceccarelli F., Valesini G. HLA-DRB1 the notorious gene in the mosaic of autoimmunity. Immunol Res. 2017 Feb;65(1):82–98. doi: 10.1007/s12026-016-8817-7. (PubMed PMID: 27435705) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lorente L., Martin M.M., Franco A., Barrios Y., Caceres J.J., Sole-Violan J. HLA genetic polymorphisms and prognosis of patients with COVID-19. Med Intensiva. 2020 Sep;6 doi: 10.1016/j.medin.2020.08.004. (PubMed PMID: 32988645. Pubmed Central PMCID: PMC7474921) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tomita Y., Ikeda T., Sato R., Sakagami T. Association between HLA gene polymorphisms and mortality of COVID-19: an in silico analysis. Immun Inflamm Dis. 2020 Oct;13 doi: 10.1002/iid3.358. (PubMed PMID: 33047883) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Novelli A., Andreani M., Biancolella M., Liberatoscioli L., Passarelli C., Colona V.L. HLA allele frequencies and susceptibility to COVID-19 in a group of 99 Italian patients. Hla. 2020 Aug;22 doi: 10.1111/tan.14047. (PubMed PMID: 32827207. Pubmed Central PMCID: 7461491) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blank M., Barzilai O., Shoenfeld Y. Molecular mimicry and auto-immunity. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2007 Feb;32(1):111–118. doi: 10.1007/BF02686087. (PubMed PMID: 17426366) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kanduc D., Shoenfeld Y. Human papillomavirus epitope mimicry and autoimmunity: the molecular truth of peptide sharing. Pathobiol J Immunopathol Mol Cell Biol. 2019;86(5–6):285–295. doi: 10.1159/000502889. (PubMed PMID: 31593963) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kanduc D., Shoenfeld Y. Molecular mimicry between SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein and mammalian proteomes: implications for the vaccine. Immunol Res. 2020 Oct;68(5):310–313. doi: 10.1007/s12026-020-09152-6. (PubMed PMID: 32946016. Pubmed Central PMCID: 7499017) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Segal Y., Shoenfeld Y. Vaccine-induced autoimmunity: the role of molecular mimicry and immune crossreaction. Cell Mol Immunol. 2018 Jun;15(6):586–594. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2017.151. (PubMed PMID: 29503439. Pubmed Central PMCID: 6078966) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baghbanian S.M., Namazi F. Post COVID-19 longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis (LETM)-a case report. Acta Neurol Belg. 2020 Sep;18 doi: 10.1007/s13760-020-01497-x. (PubMed PMID: 32948995. Pubmed Central PMCID: 7500496) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barzilai O., Ram M., Shoenfeld Y. Viral infection can induce the production of autoantibodies. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2007 Nov;19(6):636–643. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e3282f0ad25. (PubMed PMID: 17917546) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barzilai O., Sherer Y., Ram M., Izhaky D., Anaya J.M., Shoenfeld Y. Epstein-Barr virus and cytomegalovirus in autoimmune diseases: are they truly notorious? A preliminary report. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007 Jun;1108:567–577. doi: 10.1196/annals.1422.059. (PubMed PMID: 17894021) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maya R., Gershwin M.E., Shoenfeld Y. Hepatitis B virus (HBV) and autoimmune disease. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2008 Feb;34(1):85–102. doi: 10.1007/s12016-007-8013-6. (PubMed PMID: 18270862) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pavlovic M., Kats A., Cavallo M., Shoenfeld Y. Clinical and molecular evidence for association of SLE with parvovirus B19. Lupus. 2010 Jun;19(7):783–792. doi: 10.1177/0961203310365715. (PubMed PMID: 20511275) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shoenfeld Y., Selmi C., Zimlichman E., Gershwin M.E. The autoimmunologist: geoepidemiology, a new center of gravity, and prime time for autoimmunity. J Autoimmun. 2008 Dec;31(4):325–330. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2008.08.004. (PubMed PMID: 18838248) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Watad A., Amital H., Shoenfeld Y. The environment and autoimmune diseases. Harefuah. 2015 May;154(5):308–311. 39. (PubMed PMID: 26168641) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ehrenfeld M., Tincani A., Andreoli L., Cattalini M., Greenbaum A., Kanduc D. Covid-19 and autoimmunity. Autoimmun Rev. 2020 Aug;19(8):102597. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2020.102597. (PubMed PMID: 32535093. Pubmed Central PMCID: 7289100) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sedaghat Z., Karimi N. Guillain Barre syndrome associated with COVID-19 infection: a case report. J Clin Neurosci. 2020 Jun;76:233–235. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2020.04.062. (PubMed PMID: 32312628. Pubmed Central PMCID: 7158817) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Toscano G., Palmerini F., Ravaglia S., Ruiz L., Invernizzi P., Cuzzoni M.G. Guillain-Barre syndrome associated with SARS-CoV-2. N Engl J Med. 2020 Jun 25;382(26):2574–2576. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2009191. (PubMed PMID: 32302082. Pubmed Central PMCID: 7182017) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Manganotti P., Pesavento V., Buoite Stella A., Bonzi L., Campagnolo E., Bellavita G. Miller fisher syndrome diagnosis and treatment in a patient with SARS-CoV-2. J Neurovirol. 2020 Aug;26(4):605–606. doi: 10.1007/s13365-020-00858-9. (PubMed PMID: 32529516. Pubmed Central PMCID: 7288617) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tsao H.S., Chason H.M., Fearon D.M. Immune Thrombocytopenia (ITP) in a pediatric patient positive for SARS-CoV-2. Pediatrics. 2020 Aug;146(2) doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-1419. (PubMed PMID: 32439817) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zulfiqar A.A., Lorenzo-Villalba N., Hassler P., Andres E. Immune thrombocytopenic Purpura in a patient with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020 Apr 30;382(18) doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2010472. (PubMed PMID: 32294340. Pubmed Central PMCID: 7179995) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bonometti R., Sacchi M.C., Stobbione P., Lauritano E.C., Tamiazzo S., Marchegiani A. The first case of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) triggered by COVID-19 infection. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2020 Sep;24(18):9695–9697. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202009_23060. (PubMed PMID: 33015814) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jones V.G., Mills M., Suarez D., Hogan C.A., Yeh D., Segal J.B. COVID-19 and Kawasaki disease: novel virus and novel case. Hosp Pediatr. 2020 Jun;10(6):537–540. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2020-0123. (PubMed PMID: 32265235) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Verdoni L., Mazza A., Gervasoni A., Martelli L., Ruggeri M., Ciuffreda M. An outbreak of severe Kawasaki-like disease at the Italian epicentre of the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic: an observational cohort study. Lancet. 2020 Jun 6;395(10239):1771–1778. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31103-X. (PubMed PMID: 32410760. Pubmed Central PMCID: 7220177) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Amital H., Agmon-Levin N., Shoenfeld N., Arnson Y., Amital D., Langevitz P. Olfactory impairment in patients with the fibromyalgia syndrome and systemic sclerosis. Immunol Res. 2014 Dec;60(2–3):201–207. doi: 10.1007/s12026-014-8573-5. (PubMed PMID: 25424576) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shamriz O., Shoenfeld Y. Olfactory dysfunction and autoimmunity: pathogenesis and new insights. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2017 Nov-Dec;35(6):1037–1042. (PubMed PMID: 28770710) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shoenfeld N., Agmon-Levin N., Flitman-Katzevman I., Paran D., Katz B.S., Kivity S. The sense of smell in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2009 May;60(5):1484–1487. doi: 10.1002/art.24491. (PubMed PMID: 19404932) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.David P., Shoenfeld Y. The smell in COVID-19 infection: diagnostic opportunities. Isr Med Assoc J. 2020 Jul;7(22):335–337. (PubMed PMID: 32692492) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shoenfeld Y., Agmon-Levin N. ‘ASIA’ - autoimmune/inflammatory syndrome induced by adjuvants. J Autoimmun. 2011 Feb;36(1):4–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2010.07.003. (PubMed PMID: 20708902) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]