Abstract

Motivated by historical and present clinical observations, we discuss the possible unfavorable evolution of the immunity (similar to documented antibody-dependent enhancement scenarios) after a first infection with COVID-19. More precisely we ask the question of how the epidemic outcomes are affected if the initial infection does not provide immunity but rather sensitization to future challenges. We first provide background comparison with the 2003 SARS epidemic. Then we use a compartmental epidemic model structured by immunity level that we fit to available data; using several scenarios of the fragilization dynamics, we derive quantitative insights into the additional expected numbers of severe cases and deaths.

MSC: 92C60, 92D30, 34C60

Keywords: COVID-19, Antibody-dependent enhancement, SEIR model, Vaccine, Dengue fever, Asymptomatic

Highlights

-

•

The interactions between SARS-CoV-2 virus and the immune system is still unclear.

-

•

We discuss the impact of a primary infection on a secondary challenge.

-

•

Immune dynamics is modeled through increasing probability of severe forms and lethality.

-

•

Under immune fragility hypothesis we compute the incidence on challenge.

1. Introduction

The present outbreak of COVID-19 and the unprecedented response from the global human population, whether at an individual level or collectively at a political level, integrate a myriad of factors. Making out the most relevant lessons from the course taken by the disease will take time. In particular many perplexing questions have not yet found adequate answers, that would be crucial for the design of optimal treatment policies and healthcare strategies, both at the individual and societal level. Among these questions, prominent ones are: Why are the mortality patterns so skewed toward higher ages? What is the common denominator of the observed comorbidities that affect in a non-negligible way the outcome of the disease? What is the size of the asymptomatic cohorts? Are asymptomatic (or pauci-symptomatic) cases a barrier or an accelerator of the disease propagation? etc. To these salient questions, which deal with the present situation, we should add questions relative to future outbreaks, their severity and characteristics. This is particularly important as health authorities have, for obvious reasons, focused on the design of vaccines, despite the fact that vaccines are sometimes extremely difficult to obtain [1]. In particular while a response to previous infections is usually protective it can sometimes be deleterious and result in severe outcomes (see e.g. [2]). Answering many of these questions requires deep understanding of the immune response of the host, whether innate or acquired, at the cellular or humoral level. Recent research pointed out that it is critical to investigate previous history of interaction between host and infective virus strains (see [3] for SARS-CoV-2 and [4] for the Zika virus). In this context, the question of whether previous infection with coronaviruses is beneficial or detrimental to the immunity of the host is a matter of active debate, see for instance [5], [6], [7].

Here, we focus on the so-called antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE) mechanism (related to the more colorful name of cytokine storm). ADE corresponds to a situation where antibodies that normally alleviate the consequences of a viral infection end up doing the opposite: they fail to control the virus’ pathogenicity by failing to be neutralizing (i.e., the antibodies are not able to kill the virus), or even enhance its virulence either by facilitating its entry into the cell (thus enhancing the viral reproduction potential), or by triggering an extensive and misadapted reaction, thereby causing damage to the host organs through hyper-inflammation (cytokine storm).

Several documented examples are known that give rise to ADE: in SARS (see [11]), dengue (see [12], [13]), HIV-1 [14] to cite but a few. This is even already documented in the case of COVID-19 as the similarity with dengue fever has resulted in false-positive identification when using diagnostic tests based on serology (see for example in Singapore [15]). Furthermore, recent genomic investigations [9] show that reinfection can indeed occur (as opposed to viral shedding from the primary infection). Let us illustrate the first two situations more in detail: for dengue fever it is established that a previous infection with a virus belonging to a particular serotype family can cause adverse reaction upon re-infection with a virus from another serotype (see [12]). This unwanted outcome was demonstrated in a study that monitored two dengue fever outbreaks: a first one in Cuba in 1977 [16], followed by a second one twenty years later (1997) [17]. Being infected during the first epidemic was proven to negatively influence the outcome of patients infected in the 1997 epidemic (with a dengue fever serotype that differed from that of 1997). To put this otherwise, the acquired immune response was fit for a given serotype but detrimental upon challenge with a different serotype. In the present context, the large time lapse between the two dates is worth emphasizing. Irrespective of whether or not the challenge is or is not related to a different serotype, we will call this situation a “Cuban hypothesis” and discuss it below.

A misadapted immune response is not limited to infection by the dengue virus (DENV). Another documented ADE case in animal models concerns the coronavirus family. M. Bolles and his collaborators (see [11]) tested a coronavirus vaccine on animal models and the results differed, depending on the age of the vaccinated animal: while the vaccine provided partial protection against both homologous and heterologous viruses for young animal models, the same vaccine performed poorly in aged animal models and was potentially pathogenic. This shows that a faulty immune response can depend on the general maturation of the immune system, with a significant age-dependent component.

At least four human coronaviruses [229E, NL63, OC43 and HKU1 [18]] are known to be endemic. They infect mainly the upper respiratory tract. To these we must add the now well-known strains SARS-CoV-1 (responsible for the 2003 epidemic), MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2. If a “Cuban hypothesis” is found to account for the persistent development of related diseases, the challenge by any one of these viruses or novel variants may reach human populations in a variety of forms. This dire anticipation prompted us to investigate the impact of such a scenario on the immune system status within the population at large. In this context, we ask here the following questions:

-

1.

is the severity of the current individual outcomes influenced by previous coronavirus infections?;

-

2.

what is the likely state of the immune system after a first SARS-CoV-2 infection?;

-

3.

how can the present epidemic impact a future (homologous or heterologous, endemic or pandemic) coronavirus outbreak or any medical condition triggering the immune response induced by a primary infection?

2. Methods

2.1. The epidemic model of the impact of previous virus infection

The epidemic model we explored is the following: during the initial infection pathway, any patient starts in a “Susceptible” (notation “S”) class, can progress to the “Exposed” (notation “E”) class and then either to a “Severely infected” (label “”) or “Mild infected” class (including the asymptomatic and undetected individuals, denoted “”). The mild infected progress, after days to a “Mild Recovered” “” class while the “Infected” can either die (class “Deceased”, “D”) or recover after days and arrive in class “”. Note that, as in the Pasteur Institute study [8], we excluded from this analysis the dynamics of the COVID-19 epidemic within the retirement homes for aged people in France, as both the demographics of this part of the population and the transmission dynamics are very specific, while the data used to describe the COVID-19 dynamics in this setting is very uncertain.

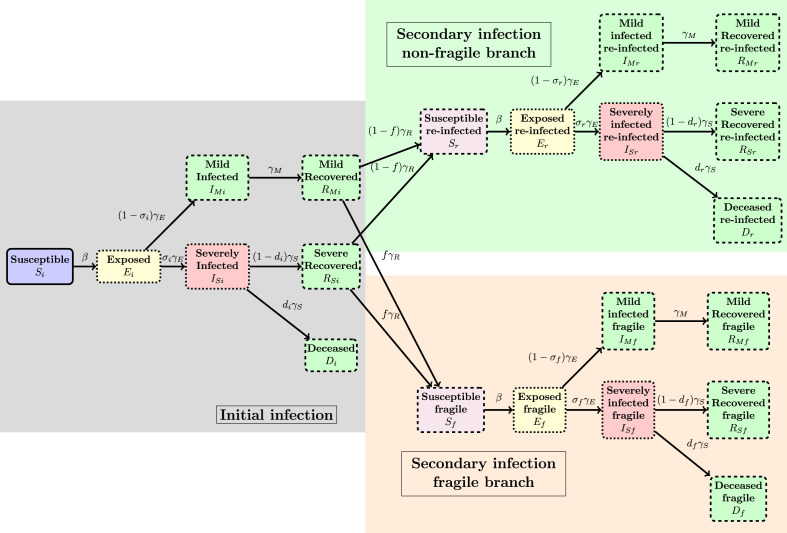

The individuals having arrived in the or classes then have a period of immunity of days and then can start a new infection again either in the class (“Susceptibles Fragilized”) or in the class of susceptibles (having had a first infection) with no particular fragility. The probability to arrive in class is taken to be . Each of the classes and is then the starting point of a new infection pathway of the same type as before. In all notations the suffix “i” in a class name will denote the “initial” infection block, the suffix “f” the “fragilized” pathway and the suffix “r” will denote the “reinfection” branch.

Mathematically the SEIRIS model is written for (see Fig. 2, Fig. 3 for illustrations):

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

| (7) |

with the notations

| (8) |

| (9) |

| (10) |

Fig. 2.

Schematic illustration of the SEIRIS model in Eqs. (1)–(7). See Fig. 3 for details.

Fig. 3.

Detailed illustration of the flow of the SEIRIS model in Eqs. (1)–(7). See Fig. 2 for a brief illustration of the general flow.

Note that the last term in Eqs. (5), (6) is only non-null for the class ‘i’ and represents the outgoing flow of primary infected individuals to the “fragile” or “non-fragile” blocks, see also Fig. 3. The incoming part of these flows, denoted appear in Eq. (1).

To model the impact of previous infections on the next possible epidemic we have to take several facts into account: while the SARS 2003 had a negligible asymptomatic class (see [21]) the COVID-19 has non-negligible number of mild or even asymptomatic individuals. Those patients are usually not detected and their estimation is statistically challenging. Even more difficult is to extrapolate the state of the immune system after a mild or severe infection and how this can be translated to future immune unbalanced response. Our assumption is the following: a coronavirus infection will sensitize a proportion of infected persons to future infections; for these persons, the immune function parameters and will increase.

2.2. Choice of parameters

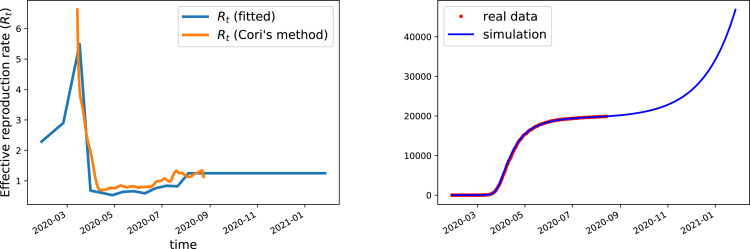

The parameters of the model were set as follows: the scenario independent infection parameters were fit, once for all, to match the curve of cumulative fatalities in a model without reinfection and fragilization (i.e., only the first block present). The results are given in Tables 1,2 and Fig. 1. Note that is only known up to time when data is available (that was stopped at August 18th). Concerning future values of we took the following assumption: the value will be set constant, at mid-distance between epidemic extinction () and the government threshold for drastic interventions ), i.e. . Once the initial simulation has been calibrated, we moved to the challenge. The set of scenarios considered is given in Table 3.

Table 1.

Description and values of the parameters used in the simulations.

| Parameter | Description (unit) | Value (95% CI if available) |

|---|---|---|

| Transmission rate | From formula (12) | |

| Severe infection rate | 3.6% (–) [8] | |

| Incubation time (day−1) | 0.25 (fit to data) | |

| Infectious time, mild infections (day−1) | 0.17 (fit to data) | |

| Infectious time, severe infections (day−1) | 0.14 (fit to data) | |

| Fatality rate (severe infections) | 18.1% (–) [8] | |

| Initial simulation time | Jan 28th 2020 | |

| Infected at initial time: (severe, mild) | (fit to data) | |

| Immunity time (day−1) | [9], see also [10] | |

| Parameters for | Scenario dependent | |

| Other branches | cf. Table 3 | |

| Effective | Fit to data | |

| Reproduction rate | See Table Table 2, Fig. 1 | |

Table 2.

Values of the effective transmission rates used in the linear interpolation that defines .

| Date | 1/1/20 | 25/2/20 | 17/3/20 | 31/3/20 | 14/4/20 |

| 1.7 | 2.9 | 5.49 | 0.68 | 0.61 | |

| Date | 28/4/20 | 12/5/20 | 26/5/20 | 9/6/20 | 23/6/20 |

| 0.53 | 0.64 | 0.66 | 0.59 | 0.76 | |

| Date | 7/7/20 | 21/7/20 | 4/8/20 | 18/8/20 | 27/1/21 |

| 0.84 | 0.82 | 1.25 | 1.25 | 1.25 | |

Fig. 1.

Left: Effective reproduction rate used in the simulations compared with the effective transmission rate published by the government site “Santé France” from [19]; this effective reproduction rate is computed using the Cori’s method [20] (averaged between tests and admissions to emergency units). Our effective reproduction rate is computed using a linear interpolation between the values given in Table 2 obtained after fitting the cumulative deaths curve until August 18th. Right: fit quality (cumulative deaths) produced by this choice of (other parameters are as in Table 1).

Table 3.

Scenarios definition (parameters) and results. Baseline scenario has ID 0. All results can be reproduced using the Python code provided as supplementary material.

| ID | Fragile () | () () |

Severe cases from 18/08/20 | Deaths from 18/08/20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0% | , | 150265 | 26863 |

| 1 | 33% | , , | 200189 | 35770 () |

| 2 | 33% | , , | 204190 | 36483 () |

| 3 | 100% | , | 309408 | 41792 () |

3. Results

We compared the outcome, in terms of deaths, of the impact of first infection on the secondary infection (challenge) outcomes under the Cuban hypothesis described in Section 1 through several scenarios. The baseline scenario (ID=0) has no fragilization neither long term immunization, immunity from initial infection being lost after days.

The first alternative scenario is when all people at high risk (age above years or with co-morbidities, i.e. 33% of the population) will experience, upon reinfection, the severe version of the disease; on the contrary all other individuals, upon reinfection, will only experience mild forms. In this scenario the second wave (defined as cases occurring after August 18th) will witness a increase in the death toll. The increase is due to the fragile branch as can be checked considering a second alternative scenario where the non-fragile branch is allowed to experience severe forms (with same rate as the primary infection, i.e., neither fragilization nor long term immunization). In this second scenario the death toll is 36% larger than the baseline, which is not very far from the figure previously obtained.

The increase between the baseline and the first alternative scenario is due to the reinfection phase: in the baseline scenario, 4.1% of the all deaths are due to the reinfection while in the first alternative scenario, 28% of all deaths come from re-infections, thus the reinfection plays a significant role in augmenting the epidemic burden.

Until now, the scenarios only considered the probability to have a severe form. We investigated next an even more extreme scenario whose parameters are similar to the SARS 2003 epidemic: upon reinfection all individuals experience severe forms with a death rate of 10%. The results show, as expected, a further deterioration of the outcomes with respect to all other scenarios (56% more when compared to the baseline). All results can be reproduced using the Python code provided as supplementary material.

4. Discussion and conclusion

We propose an epidemic model to investigate the immune function alteration induced by an initial SARS-CoV-2 infection, similar to the antibody-dependent enhancement phenomenon. Note first that the relatively controlled nature of the 2003 SARS epidemic did not allow us to draw conclusions on how the 2003 epidemic influenced the infected (too few cases); by contrast, if a sensitizing process in the immune response triggered by SARS-CoV-2 exists, the pandemic nature of the 2019/20 COVID-19 outbreak will likely have noticeable effects on the overall population health state. In particular, this implies that additional care has to be observed when validating vaccines against the COVID-19.

We developed a scenario meant to explore the consequences that a previous infection changed the likeliness to get a severe form when challenged by a new infection, possibly also increasing the death risk of severe forms (similar to more documented ADE situations as for dengue, see [13]). Irrespective of the precise parameter values we expect that this could be used as a promising methodology to quantify the epidemiological impact of ADE, with coronaviruses as key examples.

The deterioration of the immune function can be evident on two occasions: either when a second epidemic occurs or when submitted to a challenge. The challenge can be very diverse, not necessarily in the form of a fully-fledged epidemic but also a small infection with an endemic coronavirus. This may manifest in the form of multi-organ inflammation as witnessed in UK, France, Canada and the US with some presentations recalling the Kawasaki syndrome [22], [23], [24].

Until now, the global pattern of lethality of the infection appears to be more or less the same worldwide. To monitor whether an ADE-like scenario is emerging it is critical to identify, very early on, regions in the world where a significant number of young people is affected by a severe form of the disease. If this happens analysis of the viral genomes involved in these cases might reveal key features that trigger ADE.

We include a comparison with the 2003 SARS coronavirus as a mean to illustrate the shifting nature of the age classes of individuals most affected by the virus. Although this is not an evidence per se, it may allow investigators to attract research interest and more quantitative qualification of the dynamics of cross-immunity (or fragility) between SARS-CoV-2 and other (corona)viruses.

We present simulation data that measure the possible impact of such a immune function evolution. We emphasize that the alternatives considered here and the resulting figures should not be viewed as quantitative predictions but as “worst case scenarios” that may motivate further, more clinically oriented, research. Of course, our model has many limitations and the real-life immune dynamics may show a more nuanced behavior in which the immunity could be lost after a certain period of time, renewed under certain levels of new exposures to the virus, or even lost again if the additional exposures are too (or too less) frequent; further investigation into the determinants of the immune dynamics is necessary to unveil the conditions of the correct and impaired immune response. Until this is carried over, past COVID-19 patients should not be considered as having a life-time permanent acquired immunity to SARS-CoV-2 or other coronaviruses.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

We thank the CNRS MODCOV19 research platform for their support and two anonymous referees for their suggestions.

Footnotes

Supplementary material related to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mbs.2020.108499.

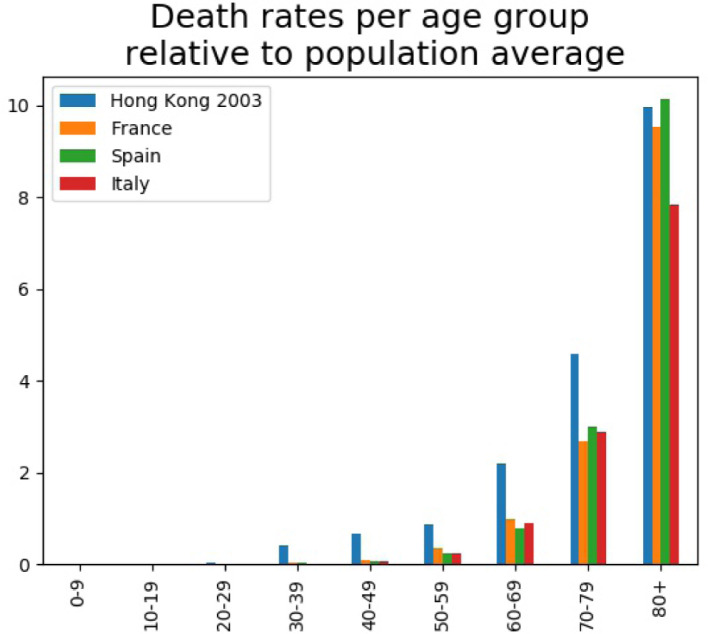

Appendix A. The Cuban hypothesis: Comparing case fatality rates in SARS 2003 and 2019–2020

In the absence of any relevant serological information, we compared age-dependent case fatality ratios of the SARS 2003 and COVID-19. More precisely, using data from [25] (see [26], [27] for additional data) we computed the age-dependent death rate for all 1755 SARS 2003 patients in Hong Kong. The benefit of using this database is that it contains information on all patients and therefore has no representation bias. For COVID-19 such data is not yet available so we used the Institut National d’Études Démographiques (INED) database [28] at the date of May 4th 2020. The two bases do not allocate cases exactly to the same age groups, we grouped together the 5-year 2003 data to fit the 2020 INED 10-year database ranges and on the other hand use uniform attribution for ages in the “above 75” 2003 HK class) to fill two corresponding classes “70-79” and “80+”.

The comparison of the 2003 and 2020 data in Fig. 4 shows a striking difference between a panel of several European countries (France, Spain, Italy) with respect to the Hong Kong results. All curves share a common shape: a constant null range followed by a marked (exponential) increase starting in the “30-39” age group for the 2003 data and “50-59” group for all countries in 2020. This 20 years shift at the onset of the exponential regime can be interpreted as resulting from the existence of a common cause (situated approximately 30–40 years before 2003 and 50–59 years before 2020, that is, between 1960 and 1970) that affected all people living at that date and which could explain why there are, 30 (respectively 50) years later, affected by the coronavirus outbreaks in a more severe way. Since the cause occurred before 1970 people born after this date will have no fragility, which is precisely what is seen in the plot. We interpret this as an evidence that previous infection history can negatively impact the individual outcome of a future infection. Note that historically the 1960–70 decade is rich in epidemic/virus related events: the Hong Kong flu of 1968–1969 (that killed an estimated 1 million people worldwide) but also the start of the identification of the four endemic human coronaviruses (mid-1960s). Note that such a conclusion is consistent with recent investigations, see [29] that showed that individuals are prone to repeated infection with coronaviruses, with the unfortunate consequence that not only the immunity may vanish (sometimes within a year) but that the re-infection can be more severe. Data in Fig. 4 substantiates the same conclusion.

Fig. 4.

Age dependent death rate comparisons between SARS 2003 and COVID-19.

Appendix B. Technical details

We compute here the basic and effective reproduction ratios (for instance the famous “”) of the model in Eqs. (1)–(7).

To this end we recall some facts concerning this computation. We will use the “next generation matrix” method as in [30], [31]. The method uses only the infectious compartments (here and works with the linearized equation in the form

| (11) |

where the matrix describes the rate of new infections and describes the transfer between compartments. Then the basic reproduction ratio is defined as the largest eigenvalue of . Note that if is an eigenvalue-eigenvector pair for i.e., , then for , thus is a root of the following equation . The same method works for the effective reproduction ratio.

Proposition B.1

The effective reproduction ratio of the model (1) – (7) is given by the formula:

(12) In particular the basic reproduction ratio is

(13)

Proof

To obtain (12) we note that, with the previous notations

(14)

(15) Manipulating the determinant of we obtain (a symbolic Python code reproducing this computation is provided as supplementary material):

(16) Thus the equation has null roots and the only non-null root is real and given by the formula (12).

The derivation of (13) from (12) is immediate from the fact that corresponds to a fully susceptible population i.e., and . □

Appendix C. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary material related to this article.

Attached are two Python codes. One of the codes reproduces the computation of the reproduction number; the other code provides numerical simulations for the test case considered in the paper.

References

- 1.Oyston Petra, Robinson Karen. The current challenges for vaccine development. J. Med. Microbiol. 2012;61(7):889–894. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.039180-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nansen Anneline, Thomsen Allan Randrup. Viral infection causes rapid sensitization to lipopolysaccharide: Central role of IFN-alpha-beta. J. Immunol. 2001;166(2):982–988. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.2.982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Armengaud Jean, Delaunay-Moisan Agnes, Thuret Jean-Yves, Anken Eelco van, Acosta-Alvear Diego, Aragon Tomás, Arias Carolina, Blondel Marc, Braakman Ineke, Collet Jean-FranΩ CÇcois, Courcol Rene, Danchin Antoine, Deleuze Jean-FranΩ CÇcois, Lavigne Jean-Philippe, Lucas Sophie, Michiels Thomas, Moore Edward R.B., Nixon-Abell Jonathon, Rossello-Mora Ramon, Shi Zheng-Li, Siccardi Antonio G., Sitia Roberto, Tillett Daniel, Timmis Kenneth N., Toledano Michel B., Sluijs Peter van der, Vicenzi Elisa. The importance of naturally attenuated SARS-CoV-2 in the fight against COVID-19. Environ. Microbiol. 2020;22(6):1997–2000. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.15039. https://sfamjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/1462-2920.15039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Katzelnick Leah C., Narvaez César, Arguello Sonia, Lopez Mercado Brenda, Collado Damaris, Ampie Oscarlett, Elizondo Douglas, Miranda Tatiana, Bustos Carillo Fausto, Mercado Juan Carlos, Latta Krista, Schiller Amy, Segovia-Chumbez Bruno, Ojeda Sergio, Sanchez Nery, Plazaola Miguel, Coloma Josefina, Halloran M. Elizabeth, Premkumar Lakshmanane, Gordon Aubree, Narvaez Federico, de Silva Aravinda M., Kuan Guillermina, Balmaseda Angel, Harris Eva. Zika virus infection enhances future risk of severe dengue disease. Science. 2020;369(6507):1123. doi: 10.1126/science.abb6143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bao Linlin, Deng Wei, Gao Hong, Xiao Chong, Liu Jiayi, Xue Jing, Lv Qi, Liu Jiangning, Yu Pin, Xu Yanfeng, Qi Feifei, Qu Yajin, Li Fengdi, Xiang Zhiguang, Yu Haisheng, Gong Shuran, Liu Mingya, Wang Guanpeng, Wang Shunyi, Song Zhiqi, Liu Ying, Zhao Wenjie, Han Yunlin, Zhao Linna, Liu Xing, Wei Qiang, Qin Chuan. 2020. Lack of reinfection in rhesus macaques infected with SARS-CoV-2. bioRxiv, 2020.03.13.990226, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tay Matthew Zirui, Poh Chek Meng, Rénia Laurent, MacAry Paul A., Ng Lisa F.P. The trinity of COVID-19: immunity, inflammation and intervention. Nature Rev. Immunol. 2020:1–12. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-0311-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tetro Jason A. Is COVID-19 receiving ADE from other coronaviruses? Microbes and Infection. 2020;22(2):72–73. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2020.02.006. Special issue on the new coronavirus causing the COVID-19 outbreak. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Salje Henrik, Tran Kiem Cécile, Lefrancq Noémie, Courtejoie Noémie, Bosetti Paolo, Paireau Juliette, Andronico Alessio, Hozé Nathanal, Richet Jehanne, Dubost Claire-Lise, Le Strat Yann, Lessler Justin, Levy-Bruhl Daniel, Fontanet Arnaud, Opatowski Lulla, Boelle Pierre-Yves, Cauchemez Simon. Estimating the burden of SARS-CoV-2 in France. Science. 2020;369(6500):208. doi: 10.1126/science.abc3517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.To Kelvin Kai-Wang, Hung Ivan Fan-Ngai, Ip Jonathan Daniel, Chu Allen Wing-Ho, Chan Wan-Mui, Tam Anthony Raymond, Fong Carol Ho-Yan, Yuan Shuofeng, Tsoi Hoi-Wah, Ng Anthony Chin-Ki, Lee Larry Lap-Yip, Wan Polk, Tso Eugene, To Wing-Kin, Tsang Dominic, Chan Kwok-Hung, Huang Jian-Dong, Kok Kin-Hang, Cheng Vincent Chi-Chung, Yuen Kwok-Yung. COVID-19 re-infection by a phylogenetically distinct SARS-coronavirus-2 strain confirmed by whole genome sequencing. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1275. ciaa1275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kellam Paul, Barclay Wendy. The dynamics of humoral immune responses following SARS-CoV-2 infection and the potential for reinfection. J. Gen. Virol. 2020;101(8):791–797. doi: 10.1099/jgv.0.001439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bolles Meagan, Deming Damon, Long Kristin, Agnihothram Sudhakar, Whitmore Alan, Ferris Martin, Funkhouser William, Gralinski Lisa, Totura Allison, Heise Mark, Baric Ralph S. A double-inactivated severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus vaccine provides incomplete protection in mice and induces increased eosinophilic proinflammatory pulmonary response upon challenge. J. Virol. 2011;85(23):12201–12215. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06048-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kourí Gustavo, Alvarez Mayling, Rodriguez-Roche Rosmari, Bernardo Lídice, Montes Tibaire, Vazquez Susana, Morier Luis, Alvarez Angel, Gould Ernest A., Guzman Maria G., Halstead Scott B. Neutralizing antibodies after infection with Dengue 1 virus. Emerg. Infect. Dis. J. 2007;13(2):282. doi: 10.3201/eid1302.060539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Katzelnick Leah C., Gresh Lionel, Halloran M. Elizabeth, Mercado Juan Carlos, Kuan Guillermina, Gordon Aubree, Balmaseda Angel, Harris Eva. Antibody-dependent enhancement of severe dengue disease in humans. Science. 2017;358(6365):929–932. doi: 10.1126/science.aan6836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Willey Suzanne, Aasa-Chapman Marlen MI, O’Farrell Stephen, Pellegrino Pierre, Williams Ian, Weiss Robin A., Neil Stuart JD. Extensive complement-dependent enhancement of HIV-1 by autologous non-neutralising antibodies at early stages of infection. Retrovirology. 2011;8(1):16. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-8-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yan Gabriel, Lee Chun Kiat, Lam Lawrence T.M., Yan Benedict, Chua Ying Xian, Lim Anita Y.N., Phang Kee Fong, Kew Guan Sen, Teng Hazel, Ngai Chin Hong, Lin Li, Foo Rui Min, Pada Surinder, Ng Lee Ching, Tambyah Paul Anantharajah. Covert COVID-19 and false-positive dengue serology in Singapore. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020;20(5):536. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30158-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cantelar de Francisco N., Fernández A., Albert Molina L., Pérez Balbis E. Survey of dengue in Cuba. 1978-1979. Rev. Cubana Med. Trop. 1981;33(1):72–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guzmán Maria G., Kouri Gustavo, Valdes Luis, Bravo Jose, Alvarez Mayling, Vazques Susana, Delgado Iselys, Halstead Scott B. Epidemiologic studies on dengue in Santiago de Cuba, 1997. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2000;152(9):793–799. doi: 10.1093/aje/152.9.793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Corman Victor M., Muth Doreen, Niemeyer Daniela, Drosten Christian. Hosts and sources of endemic human coronaviruses. In: Kielian Margaret, Mettenleiter Thomas C., Roossinck Marilyn J., editors. Advances in Virus Research, vol. 100. Academic Press; 2018. pp. 163–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Covid Tracker : suivez l’épidémie du Covid19 en France et dans le monde ! - data.gouv.fr, https://www.data.gouv.fr/fr/reuses/covid-tracker-suivez-lepidemie-du-covid19-en-france-et-dans-le-monde/.

- 20.Thompson R.N., Stockwin J.E., van Gaalen R.D., Polonsky J.A., Kamvar Z.N., Demarsh P.A., Dahlqwist E., Li S., Miguel E., Jombart T., Lessler J., Cauchemez S., Cori A. Improved inference of time-varying reproduction numbers during infectious disease outbreaks. Epidemics. 2019;29 doi: 10.1016/j.epidem.2019.100356. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1755436519300350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leung Gabriel M., Chung Pui-Hong, Tsang Thomas, Lim Wilina, Chan Steve K.K., Chau Patsy, Donnelly Christl A., Ghani Azra C., Fraser Christophe, Riley Steven, Ferguson Neil M., Anderson Roy M., Law Yuk-lung, Mok Tina, Ng Tonny, Fu Alex, Leung Pak-Yin, Peiris J.S. Malik, Lam Tai-Hing, Hedley Anthony J. SARS-CoV antibody prevalence in all Hong Kong patient contacts. Emerg. Infect. Diseases. 2004;10(9):1653–1656. doi: 10.3201/eid1009.040155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Riphagen Shelley, Gomez Xabier, Gonzalez-Martinez Carmen, Wilkinson Nick, Theocharis Paraskevi. Hyperinflammatory shock in children during COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2020;395(10237):1607–1608. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31094-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Verdoni Lucio, Mazza Angelo, Gervasoni Annalisa, Martelli Laura, Ruggeri Maurizio, Ciuffreda Matteo, Bonanomi Ezio, D’Antiga Lorenzo. An outbreak of severe Kawasaki-like disease at the Italian epicentre of the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic: an observational cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10239):1771–1778. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31103-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Viner Russell M., Whittaker Elizabeth. Kawasaki-like disease: emerging complication during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2020;395(10239):1741–1743. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31129-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leung Gabriel M., Hedley Anthony J., Ho Lai-Ming, Chau Patsy, Wong Irene O.L., Thach Thuan Q., Ghani Azra C., Donnelly Christl A., Fraser Christophe, Riley Steven, Ferguson Neil M., Anderson Roy M., Tsang Thomas, Leung Pak-Yin, Wong Vivian, Chan Jane C.K., Tsui Eva, Lo Su-Vui, Lam Tai-Hing. The epidemiology of severe acute respiratory syndrome in the 2003 Hong Kong epidemic: An analysis of all 1755 patients. Ann. Int. Med. 2004;141(9):662. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-9-200411020-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chan Jane C.K., Tsui Eva L.H., Wong Vivian C.W. Prognostication in severe acute respiratory syndrome: A retrospective time-course analysis of 1312 laboratory-confirmed patients in Hong Kong. Respirology. 2007;12(4):531–542. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2007.01102.x. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1440-1843.2007.01102.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jia Na, Feng Dan, Fang Li-Qun, Richardus Jan Hendrik, Han Xiao-Na, Cao Wu-Chun, Vlas Sake J. De. Case fatality of SARS in mainland China and associated risk factors. Trop. Med. Int. Health. 2009;14(s1):21–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2008.02147.x. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1365-3156.2008.02147.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ined - Institut national d’études démographiques, La démographie des décés par COVID-19, https://dc-covid.site.ined.fr/fr/.

- 29.Galanti Marta, Shaman Jeffrey. 2020. Direct observation of repeated infections with endemic coronaviruses. medRxiv. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.04.27.20082032v1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van den Driessche P., Watmough James. Reproduction numbers and sub-threshold endemic equilibria for compartmental models of disease transmission. Math. Biosci. 2002;180(1):29–48. doi: 10.1016/s0025-5564(02)00108-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roddam Andrew W. mathematical epidemiology of infectious diseases: Model building, analysis and interpretation: O Diekmann and JAP Heesterbeek, 2000, Chichester: John Wiley pp. 303, £39.95. ISBN 0-471-49241-8. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2001;30(1) 186–186. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Attached are two Python codes. One of the codes reproduces the computation of the reproduction number; the other code provides numerical simulations for the test case considered in the paper.