ABSTRACT

Background

International Medical Graduates (IMGs) contribute to about 23% of the physician workforce in the USA. Certain US-trained IMGs face long wait times for transitioning to a permanent resident status, which limits their ability to work to fullest capacity, especially during a public health emergency.

Objectives

To estimate the number of US-trained IMGs awaiting permanent residency.

Study Design

Data were obtained from National Residency Matching Program (NRMP) to quantify the number of IMGs who secured residency training in the US from 2004 to 2020. Estimates of physician demographics were based on NRMP/ECFMG 2014 match data and Federation of State Medical Boards (FSMB) physician census data.

Results

Between 2004 and 2020, a total of 57,160 non-US IMGs who were not US citizens successfully matched to residency training programs. Applicants from India and China were noted to be impacted by delays in adjustment to permanent resident status. Per our estimate, there are between 1,460 and 1,959 US-trained physicians from China currently awaiting permanent residency, with applicants waiting since October 2015, and between 13,250 and 14,230 US-trained physicians from India currently awaiting permanent residency, with applicants waiting since June 2009.

Conclusions

The total number of US-trained immigrant physicians in active practice awaiting permanent residency to the USA is estimated to be ranging between 14,710 and 16,189.

KEYWORDS: International Medical Graduates Policy Physician shortage

1. Background

Each year, multiple physicians from all over the world attempt to secure residency training in the USA [1]. Physicians who graduate from international medical schools are called International Medical Graduates (IMGs) [1]. Many of these physicians require visa sponsorship for legal entry into the USA (US) to initiate their residency training [2]. After completion of their training, they become eligible to apply for a permanent resident status in the USA, often colloquially referred to as a ‘green card’ [3]. However, due to the limited annual quota of green cards, which are allocated based on the country of birth of the applicant, the wait times can vary widely among applicants. Due to the sheer number of applicants from countries like India and China, expectedly higher from the two most populous countries in the world, these applicants have the longest wait times before they become eligible to adjust their status to that of a permanent resident [4]. While every applicant seeking an employment-based immigrant visa must demonstrate that they possess specific skills, advanced degrees or extraordinary abilities for their eligibility, physicians constitute a small but particularly highly trained subset of these applicants. Notably, these physicians are perhaps the few immigrants where federal tax dollars have already been utilized for their training, as they navigate through years of grueling residency training, often followed by even more specialized fellowship training.

Given the resource-intensive process of training a physician, there are several legislative programs in places such as the Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC) program and the Conrad 30 program, with the primary purpose of retaining these assets to serve areas of the USA with inadequate physician access [5]. Furthermore, if these highly trained physicians are unencumbered by restrictions imposed by their visa status, they could be mobilized to areas of higher need. This flexibility could prove crucial amidst a public health crisis, such as the COVID-19 pandemic [6]. Therefore, it is imperative to quantify the number of immigrant physicians who are awaiting permanent residency status due to the reasons mentioned above.

To the best of our knowledge, the USA Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) does not publish or track profession-specific data pertaining to applicants with an approved I-140 (Immigrant Petition for Alien Workers), who have not yet become eligible for applying for an adjustment of status [5]. In the absence of this information, one can only estimate the number of immigrant physicians currently awaiting permanent residency status. For this reason, we have attempted to quantify the prevalence of US-trained immigrant physicians awaiting permanent residency.

2. Methods

We formulated a stepwise approach to the problem, by first quantifying the number of non-US IMGs (International Medical Graduates who were not US citizens), who had sought residency training in the USA, from 2004 until 2020. Residency training in the USA has a minimum duration of 3 years, with some physicians pursuing subsequent fellowship training of minimum 2 years duration, only after completion of which would the physician start working in the capacity of an attending physician and become eligible to apply for permanent residency[7]. Most physicians qualify for the ‘EB-2’ immigrant visa category, which specifies that the applicants must be ‘professionals holding advanced degrees and persons of exceptional ability’[8]. As of May 2020, based on data from the US Department of State, the subset of EB-2 applicants most impacted by delays in transition to permanent residency had applied in July 2009 and onwards[9]. To account for 5 years of training as elucidated above, we chose 2004 as the earliest data point for the sake of our analysis. The National Residency Matching Program (NRMP) is a private, non-profit organization that utilizes a sophisticated algorithm to allow medical students to be matched with their preferred residency training programs[10]. With rare exceptions, the overwhelming majority of applicants utilize the NRMP match to secure a residency training position. We collected data from the NRMP Residency Match Data and Reports to determine the cumulative number of non-US IMGs who had successfully matched for each year since 2004 [10–14].

Determining the country of birth of practicing physicians posed a unique challenge, as this demographic information is not evaluated by agencies tracking data pertaining to the US physician workforce. While there are exceptions, most individuals complete their medical education prior to residency in their countries of birth. Therefore, we used the country where the physician completed their medical school graduation as a surrogate for their country of birth. Based on 2018 data from the biennial census of physicians with active licenses conducted by the Federation of State Medical Boards (FSMB), we determined the percentage of practicing physicians who completed their medical school graduation from various countries[15]. These numbers were used to get an estimate of physicians who had likely applied for immigrant petitions currently practicing in the USA but were awaiting permanent residency.

3. Results

The cumulative number of non-US IMGs who had successfully matched for residency training from 2004 to 2020 was 57,160 [10–14]. Based on the May 2020 [11] Visa Bulletin released by the US Department of State, all EB-2 applicants with an approved I-140 were eligible to adjust their status, other than those who were born in India and China[9]. Thus it was important to determine the percentage of non-US IMGs from these countries who had secured residency training since 2004. The 2018 FSMB census data suggested that while the proportion of physicians from China was relatively small and was not quantified, the majority of licensed IMGs that were currently in practice in the US had graduated from medical schools in India, with their numbers being estimated at 50,173 (23%) (Figure 1)[15]. Upon review of prior biennial census data from the FSMB, this percentage of IMGs from India has remained remarkably stable over several years. Furthermore, match data obtained by a joint effort from the NRMP and the Educational Council for Foreign Medical Graduates (ECFMG) in 2014, also obtained every applicant’s citizenship at birth. Review of these demographic data suggested that 24.7% (880/3556) of matched applicants were Indian citizens at birth. Therefore, given the stability of this percentage despite the influx of medical graduates each year, we operated under the assumption that the composition of IMGs matching to US residency programs was similar to FSMB census data. We thereby estimate approximately between 13,250 and 14,230 US-trained physicians from India currently awaiting permanent residency, with some applicants waiting since June 2009 (Figure 2).

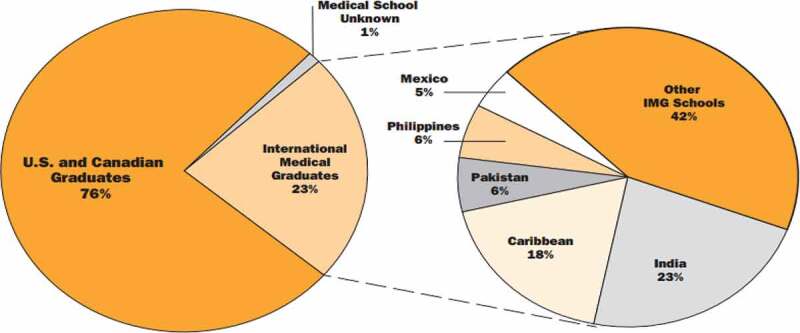

Figure 1.

Licensed physicians in the USA by location of medical school graduation (Source: 2018 FSMB Census of Licensed Physicians).[15]

IMG = International Medical Graduate. Twenty-three percent of the physician workforce in the USA is IMGs. Eighteen percent of the IMGs are US or Canadian born citizens graduated from a Caribbean medical school. Twenty-three percent of the IMGs are from India.

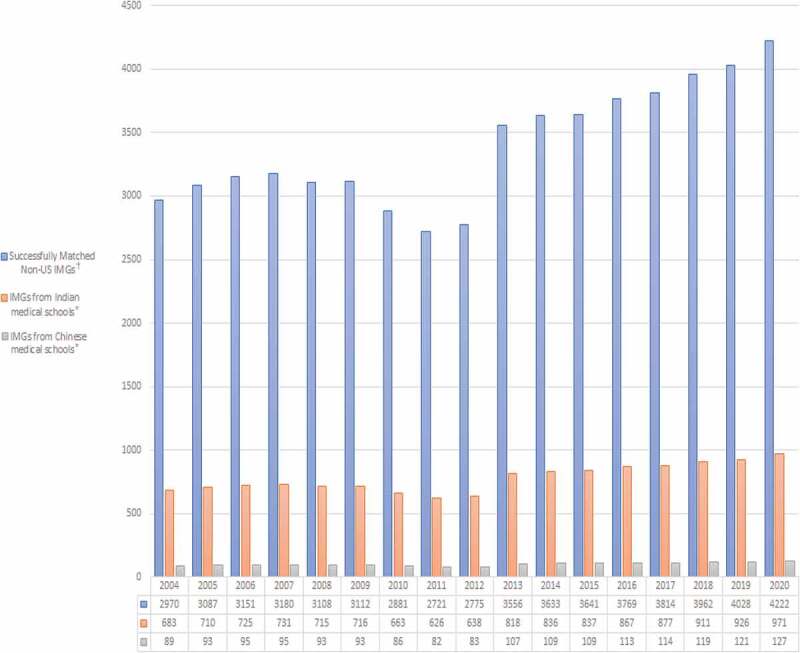

Figure 2.

Estimated number of IMGs graduating from medical schools in India and China

†Numbers of non-US IMGs successfully matched from 2004 to 2020 obtained from NRMP (data used with permission) [10–14]*Estimated IMGs graduating from medical schools in India and China, based on FSMB data[15]

Since the FSMB census data did not assign a definitive number of US-trained Chinese physicians, we revisited the NRMP-ECFMG 2014 match data and noted that 3.4% (122/3556) were Chinese citizens at birth (Figure 3)[13]. Additionally, we utilized data from a study published by Duvivier et al. in April 2019[16]. The authors procured data from the American Medical Association Physician Masterfile, noting that the total number of Chinese-educated physicians had risen modestly from 3,878 in 2008, to 5,355 in 2017. Additionally, they noted that as compared to 2008 data where 892 physicians were in residency training, only 730 physicians were in residency training positions in 2017. They inferred that there had been a relative decline in the influx of physicians who completed their medical school graduation in China. According to data from the May 2020 Visa Bulletin, EB-2 applicants from China with an approved I-140 from October 2015 are eligible for adjustment of status to permanent residency[8]. Assuming the modest rate of influx of Chinese physicians as noted in the Duvivier study, with a relatively higher rate noted in the NRMP-ECFMG 2014 data, there would be approximately between 1,460 and 1,959 US-trained physicians from China currently awaiting permanent residency, with some applicants waiting since October 2015.

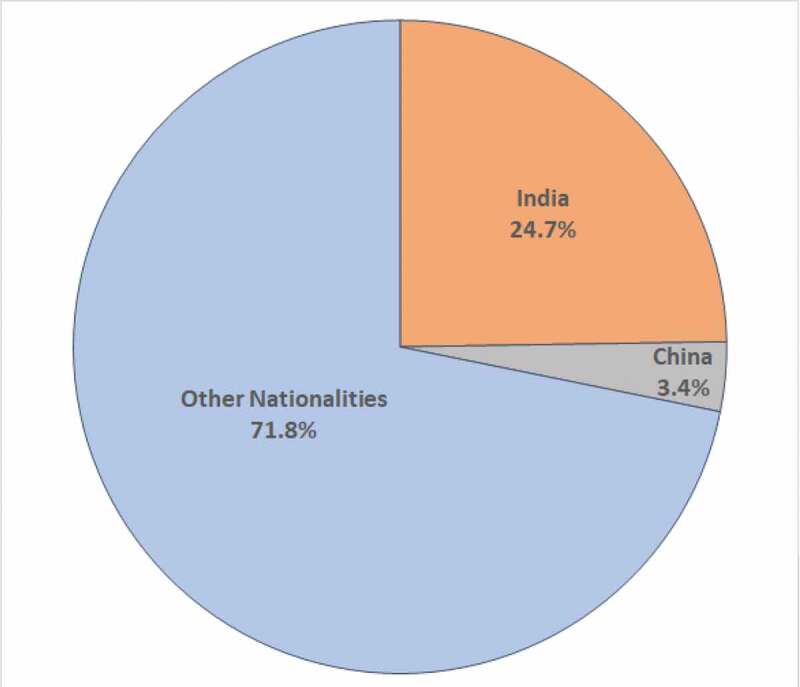

Figure 3.

2014 NRMP match applicants – Citizenship at birth. Adapted from charting outcomes in the Match for IMGs, 2014. Source: NRMP data warehouse and ECFMG.[12]

About 24.7% of the NRMP match applicants are from India, followed by China, 3.4%. Rest of the world constituted about 71.8%.

Combining the estimates listed above, the total number of US-trained foreign physicians in active practice awaiting permanent residency to the USA is estimated to be ranging between 14,710 and 16,189.

4. Discussion

The robust clinical and research experience offered during residency and fellowship training attracts thousands of foreign physicians to the USA each year. This has resulted in nearly a quarter of practicing physicians in the US to be IMGs. American Medical Association (AMA) suggests that about 22.7% of the licensed US physicians are IMGs. Owing to the ever-expanding population and the retirement of the existing physician workforce, the number of IMGs in practice has grown by nearly 28,000 since 2010, a 14.6% rise and that figure is bigger than the 12% rise in US. medical graduates over that same time period[17].

In a report published by the AMA in October 2019, it was noted that 98% of IMGs speak two or more languages fluently, helping patients overcome linguistic and cultural barriers that can impede care. IMGs tend to work mostly in the primary care specialties (about 62%) and that is about double the 31% of all US. physicians who work in a primary care specialty, helping to meet a critical workforce need. This influx of highly trained immigrants has positively impacted the physician shortages across the country. Due to programs redirecting these US-trained foreign physicians such as the ARC program and Conrad 30 program, these physicians serve in higher proportions in rural and underserved areas, where there are greater African American, Hispanic and non-White populations[18]. This suggests that these actively licensed physicians are caring for the most medically vulnerable Americans. In this manner, physician immigration into the USA is mutually beneficial.

However, the inability of US-trained immigrant physicians to secure permanent resident status for prolonged periods, in comparison to their peers who trained in other countries, increases physician dissatisfaction and may serve as a disincentive to continue to practice in the USA. Furthermore, their visa restrictions prevent them from pursuing additional opportunities such as offering new medical services or hiring additional staff members, which would benefit the communities they serve from both healthcare and economic standpoint. For this reason, it is important to be able to quantify this untapped resource and introduce means to expedite the permanent residency status of these highly skilled immigrants working towards the nation’s best interests.

5. Conclusion and policy implications

There are nearly 15,000 US-trained foreign physicians in the USA who are awaiting permanent resident status and are consequently limited in their scope due to visa restrictions. This cohort represents a large pool of US-trained, licensed physicians who are not being utilized to their fullest potential. Devising means to expedite their legal immigration would bolster the healthcare workforce and prevent growing physician shortages in the USA, during and even after the ongoing global public health emergency.

6. Limitations and bias

There are several limitations and potential sources of error that we would like to acknowledge, which limit the precision of our estimates. While the EB-2 immigrant visa is the pathway that most physicians are eligible for, a few others may have obtained permanent residency via alternative means which greatly reduced wait times, such as the EB-1 immigrant visa (alien of extraordinary ability) or the EB-5 immigrant visa (immigrant investor) category.

There are personal circumstances which may alter our estimate, such as dual foreign physician households (only one family immigrant petition would be required), foreign physicians married to US citizens, foreign physicians who accepted a residency position outside of the NRMP match, and US-trained foreign physicians who may no longer be in practice (left the US, became disabled, or deceased). These factors are difficult to quantify based on publicly available databases. However, our effort appears to be the only publication attempting a quantitative analysis of this unique problem afflicting the US physician workforce.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- [1].Ranasinghe PD. International Medical Graduates in the US Physician Workforce. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2015;115(4):236–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].International medical graduate (IMGs ). American Medical Association website. [cited June 4, 2020]. http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/about-ama/our-people/member-groups-sections/international-medical-graduates.page

- [3].Immigration information for international medical graduates . [cited June 4, 2020]. https://www.ama-assn.org/education/international-medical-education/immigration-information-international-medical-graduates

- [4].150‐ Year Wait for Indian Immigrants With Advanced Degrees . [cited June 5, 2020]. https://www.cato.org/blog/150-year-wait-indian-immigrants-advanced-degrees.

- [5].Ester K. Knowledge Services Group. Foreign medical graduates: A brief overview of the J-1 visa waiver program. Congressional Research Service, Library of Congress; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Events as they Happen, World Health Organization . [cited June 5, 2020]. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/events-as-they-happen [Google Scholar]

- [7].Getting a U.S. Fellowship . Requirements for Foreign Medical Graduates. [cited June 5, 2020]. Available form: https://www.aao.org/young-ophthalmologists/yo-info/article/getting-u-s-fellowship-requirements-foreign-medica

- [8].Green card Eligibility criteria . [cited June 5, 2020]. Available form: https://www.uscis.gov/green-card/green-card-eligibility-categories.

- [9].US Department of State - Bureau of Consular Affairs . Visa Bulletin for May 2020. Published April 2020. [cited June 5, 2020]. Available form: https://travel.state.gov/content/travel/en/legal/visa- law0/visa-bulletin/2020/visa-bulletin-for-may- 2020.html

- [10].National Residency Matching Program . Results and Data: 2008 main residency match®. Published April 2008. [cited June 5, 2020]. Available form: https://mk0nrmp3oyqui6wqfm.kinstacdn.com/wp- content/uploads/2013/08/resultsanddata2008.pdf [Google Scholar]

- [11].National Residency Matching Program . Results and Data: 2010 main residency match®. Published April 2010. [cited May 2020] http://www.nrmp.org/wp- content/uploads/2013/08/resultsanddata2010.pdf [Google Scholar]

- [12].National Resident Matching Program and Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates . Charting outcomes in the match for international medical graduates; 2014. Published January 2014. Accessed May 2020.

- [13].National Residency Matching Program . Results and Data: 2015 Main Residency Match®. Published April 2015. [cited May 2020]. http://www.nrmp.org/wp- content/uploads/2015/05/Main-Match-Results-and- Data-2015_final.pdf.

- [14].National Residency Matching Program . Advance Data Tables for the 2020 Main Residency Match®. Published March 2020. [cited May 2020]. https://mk0nrmp3oyqui6wqfm.kinstacdn.com/wpcontent/uploads/2020/03/AdvanceData-Tables- 2020.pdf

- [15].Young A, Chaudhry HJ, Pei X, et al. Steingard SA. FSMB Census of Licensed Physicians in the USA, 2018. J Med Reg. 2019. July;105(2):7–23. . [Google Scholar]

- [16].Duvivier RJ, Boulet J, Qu JZ.. The contribution of Chinese-educated physicians to health care in the USA. PloS One. 2019;14(4):e0214378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].How IMGs have changed the face of American medicine . [cited June 2020]. https://www.ama-assn.org/education/international-medical-education/how-imgs-have-changed-face-american-medicine.

- [18].American Immigration Council . Foreign-trained doctors are critical to serving many U.S. Communities. Published January 2018. [cited May 2020]. https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/sites/default/files/research/foreign- trained_doctors_are_critical_to_serving_many_us_c ommunities.pdf.