Abstract

BACKGROUND

The placenta is the active interface between mother and foetus, bearing the molecular marks of rapid development and exposures in utero. The placenta is routinely discarded at delivery, providing a valuable resource to explore maternal-offspring health and disease in pregnancy. Genome-wide profiling of the human placental transcriptome provides an unbiased approach to study normal maternal–placental–foetal physiology and pathologies.

OBJECTIVE AND RATIONALE

To date, many studies have examined the human placental transcriptome, but often within a narrow focus. This review aims to provide a comprehensive overview of human placental transcriptome studies, encompassing those from the cellular to tissue levels and contextualize current findings from a broader perspective. We have consolidated studies into overarching themes, summarized key research findings and addressed important considerations in study design, as a means to promote wider data sharing and support larger meta-analysis of already available data and greater collaboration between researchers in order to fully capitalize on the potential of transcript profiling in future studies.

SEARCH METHODS

The PubMed database, National Center for Biotechnology Information and European Bioinformatics Institute dataset repositories were searched, to identify all relevant human studies using ‘placenta’, ‘decidua’, ‘trophoblast’, ‘transcriptome’, ‘microarray’ and ‘RNA sequencing’ as search terms until May 2019. Additional studies were found from bibliographies of identified studies.

OUTCOMES

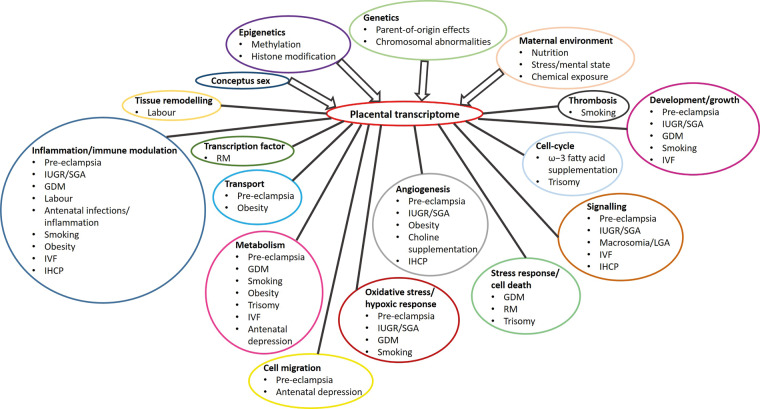

The 179 identified studies were classifiable into four broad themes: healthy placental development, pregnancy complications, exposures during pregnancy and in vitro placental cultures. The median sample size was 13 (interquartile range 8–29). Transcriptome studies prior to 2015 were predominantly performed using microarrays, while RNA sequencing became the preferred choice in more recent studies. Development of fluidics technology, combined with RNA sequencing, has enabled transcript profiles to be generated of single cells throughout pregnancy, in contrast to previous studies relying on isolated cells. There are several key study aspects, such as sample selection criteria, sample processing and data analysis methods that may represent pitfalls and limitations, which need to be carefully considered as they influence interpretation of findings and conclusions. Furthermore, several areas of growing importance, such as maternal mental health and maternal obesity are understudied and the profiling of placentas from these conditions should be prioritized.

WIDER IMPLICATIONS

Integrative analysis of placental transcriptomics with other ‘omics’ (methylome, proteome and metabolome) and linkage with future outcomes from longitudinal studies is crucial in enhancing knowledge of healthy placental development and function, and in enabling the underlying causal mechanisms of pregnancy complications to be identified. Such understanding could help in predicting risk of future adversity and in designing interventions that can improve the health outcomes of both mothers and their offspring. Wider collaboration and sharing of placental transcriptome data, overcoming the challenges in obtaining sufficient numbers of quality samples with well-defined clinical characteristics, and dedication of resources to understudied areas of pregnancy will undoubtedly help drive the field forward.

Keywords: placenta, decidua, transcriptome, microarray, RNA sequencing, pregnancy, trophoblast, development, pre-eclampsia

Introduction

The human placenta undergoes rapid growth and development usually over a span of 9 months. Serving as the maternal–foetal interface, the placenta facilitates communication between mother and child throughout gestation. Therefore, investigating the placenta provides a window into how the pregnancy has progressed and an insight into the potential health trajectory of the child. To better understand maternal–placental–foetal health, especially in the context of pregnancy complications, numerous microarrays and RNA-sequencing studies have been performed to profile the placental transcriptome. Recent rapid technological advancements in ‘omics’ have enabled parallel gathering of large datasets from maternal, placental and foetal tissues across gestation.

This review summarizes genome-wide human placental transcriptome studies performed over the last two decades. We provide an overview of transcriptome study methods, outline the important considerations for study design and interpretation, discuss past study results and highlight knowledge gaps that should be addressed in future studies. As the review is focussed on human placental studies, animal studies will not be referred to. Studies in other mammals (Barreto et al., 2011; Buckberry et al., 2017; Carter, 2018) have undoubtedly provided additional valuable perspectives on placental health and disease and have added to knowledge on comparative placentation across species.

Transcript profiling methods

Two methods used to obtain genome-wide placental transcript profiles are microarrays and RNA sequencing. These high-throughput technologies generate large amounts of data and offer a means to analyse the placenta in an unbiased manner.

Microarrays

Microarrays utilize short oligonucleotide probes embedded on a chip, which when hybridized to specific RNA or DNA sequences present in the sample emits fluorescence (Cox et al., 2015), allowing simultaneous quantitation of many gene transcripts. Commercially available chips from Affymetrix, Agilent and Illumina are commonly used in placental research, although a few studies have custom-made theirs. The main drawback of microarray chips is that a gene-specific probe must be present for a gene to be detected. As the earliest placental microarray studies were performed around the time the first human genome was sequenced, not all transcripts were detectable by gene probes available at that time. Moreover, RNA biology was not as well understood as it is now with the current knowledge of non-coding RNA and RNA gene silencing. Additionally, microarray probes are species-specific. Nevertheless, given established bioinformatics pipelines and readily available statistical tools to analyse microarray data, with publically available datasets for comparison from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) and the European Bioinformatics Institute (EBI) ArrayExpress repositories, microarrays continue to be widely used (Cox et al., 2015).

RNA sequencing

Next-generation RNA sequencing is more sensitive than conventional microarray and generates a fuller picture of the placental transcriptome. The Illumina Hiseq and Genome Analyzer II systems are the most popular platforms in placental research and are increasingly used as the price of sequencing falls. Sequencing can detect rare and novel RNA transcripts, identify single-nucleotide variants in both coding and non-coding RNA of all lengths, and is not species-dependent. Furthermore, recent development of microfluidics technology with RNA sequencing allows transcripts of individual cells to be determined, which was not previously possible (Hu et al., 2018b). However, single-cell RNA sequencing of the syncytiotrophoblast, which forms the placental cellular barrier, remains a challenge since its large size and multi-nucleated nature does not permit its isolation with microfluidics technology. The targeted sequencing depth or number of reads sequenced per sample is dependent on experimental aims and design. For instance, the ENCODE guidelines recommend a minimum sequencing depth of 30 million reads for bulk RNA sequencing that is commonly used for differential gene expression analysis, while 10 000 to 50 000 reads per cell in single-cell sequencing are sufficient to classify cells in an unbiased manner (Haque et al., 2017). Another question-dependent experimental design consideration is whether to sequence library preparations from ribosomal RNA (rRNA)-depleted total RNA (including non-coding RNA) or those enriched for mRNA transcripts by poly A+ selection. Given the vast potential of RNA sequencing, it is unsurprising that its use is growing exponentially in placental research.

Why profile the human placental transcriptome?

In most pregnancies, the villous placenta is genetically identical to the foetus and is the first foetal-placental tissue in direct contact with the maternal exposome. The placental transcriptome may, therefore, represent to an extent both inherent foetal characteristics and the foetal response to the intrauterine environment. Data generated from genome-wide profiling of the human placenta have several uses. Firstly, analyses of normal placentas throughout gestation enhances understanding of healthy development, which serves as a reference point for studies of how the placenta responds and adapts to various exposures and challenges in complicated pregnancies. Secondly, by analysing placentas from compromised pregnancies, pathological changes linked with different clinical phenotypes can be identified and utilized for developing biomarkers or targets for prediction, diagnosis and therapeutic interventions. For instance, placental-specific gene products that are secreted into the maternal circulation can serve as a non-invasive direct readout of placental function and an indirect measure of foetal wellbeing (Cox et al., 2015). One such success story of transcript profiling is sFLT1, which was first identified to be up-regulated in pre-eclamptic placentas by microarray (Maynard et al., 2003) and is now being trialled in clinical screening to predict if a pregnant woman is at risk of developing pre-eclampsia (Zeisler et al., 2016). Additionally, knowledge of the dysfunctional molecular processes at the maternal–foetal interface provides novel insights into the potential causal mechanisms underlying placental pathologies, which may open up new avenues for developing preventative measures for pregnancy complications. Moreover, the placenta functions as the intermediary between mother and child, participating in the normal programming of the developing foetus to face the prevailing environmental conditions of ex utero life (Burton et al., 2016). Understanding these programming mechanisms and deviations in pathological conditions opens up the possibility of modifying offspring growth and health trajectories arising from compromised intrauterine environments, through interventions that target the placenta, or identifying at-risk children who will benefit from close follow-up and early childhood interventions.

Placental transcriptome: search methods and study themes

The PubMed database and the NCBI GEO and EBI ArrayExpress repositories were used to identify relevant studies and human placental transcriptome datasets, respectively up to May 2019. Our search included terms such as ‘placenta’, ‘decidua’, ‘trophoblast’, ‘transcriptome’, ‘microarray’, ‘RNA sequencing’ and was refined by restricting only to human studies and genome-wide datasets. Additional studies were identified by references within articles.

We identified a total of 179 unique genome-wide datasets related to human placenta. These datasets collectively represent the genome-wide transcriptomes of around 3000 placentas since 2004. Most of these datasets were generated within the last five years, highlighting the rapid expansion of human placental transcriptome studies, with a clear preferential shift towards RNA sequencing from conventional microarrays in the field.

Placental transcriptome studies can broadly be divided into four main study themes: healthy placental development (Table I), pregnancy complications (Table II), exposures during pregnancy (Table III) and in vitro placental cultures (Table IV). The tables list studies in chronological order and studies with fewer than five samples are presented separately in Supplementary Table SI. Studies in each theme are summarized and discussed in the context of the following considerations.

Table I.

Healthy placental development.

| Year | Accession ID | Platform | Type | Tissue/cell | Sampling site | Total no. | Gestation | Purpose | Associated publications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Gestation-specific effects | |||||||||

| 2008 | NCBI GEO GSE9984 | Affymetrix Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Array | Microarray | Tissue | Chorionic villi |

|

1st, 2nd and 3rd trimester | Profile placenta across gestation | Mikheev et al. (2008) |

| 2011 | NCBI GEO GSE28551 | ABI Human Genome Survey Microarray Version 2 | Microarray | Tissue | Chorionic villi |

|

1st and 3rd trimester | Assess placental development across gestation | Sitras et al. (2012) |

| 2015 | NCBI GEO GSE66302 |

|

RNA-seq | Tissue | Amnion, chorion, chorionic villi, decidua, umbilical cord |

|

1st and 2nd trimester | Development from early to mid-pregnancy | Roost et al. (2015) |

| 2016 | NCBI GEO GSE75010 | Affymetrix Human Gene 1.0 ST Array | Microarray | Tissue | Placenta biopsy (basal plate + chorionic villi) | 157 | 3rd trimester | Identify markers of villous maturation (with histological data) | Leavey et al. (2017) |

| 2017 | NCBI GEO GSE98752 |

|

RNA-seq | Tissue | Chorionic villi |

|

1st and 3rd trimester | Placental development across gestation (with linked methylation data) | Lim et al. (2017b) |

| 2018 | NCBI GEO GSE100051 | Illumina HumanHT-12 V4.0 Expression Beadchip | Microarray | Tissue | Chorionic villi |

|

1st, 2nd and 3rd trimester | Profile placenta across gestation | Soncin et al. (2018) |

| Not publically available | Affymetrix Human Genome U133A Array | Microarray | Tissue | Chorionic villi |

|

1st and 3rd trimester | Identify placental-specific transcripts in maternal blood | Tsui et al. (2004) | |

|

| |||||||||

|

Cellular characterization and differentiation | |||||||||

| 2008 | NCBI GEO GSE10612 | Affymetrix Human Genome U133A Array; Affymetrix Human Genome U133A 2.0 Array | Microarray | Sorted cell (flow cytometry/ magnetic bead) | Decidua | 11 | 1st trimester | Characterize decidual macrophages | Gustafsson et al. (2008) |

| 2008 | NCBI GEO GSE11510 | Affymetrix Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Array | Microarray | Primary cell cultures | Amnion, chorionic plate, chorionic villi, decidua, umbilical cord | 10 | 3rd trimester | Placental cell taxonomy | Kawamichi et al. (2010) |

| 2013 | NCBI GEO GSE44368 | Affymetrix Human Gene 1.0 ST Array | Microarray | Primary cell cultures | Chorionic villi |

|

3rd trimester | Sexual dimorphism of trophoblast and endothelial cells | Cvitic et al. (2013) |

| 2013 | NCBI GEO GSE24268 | Agilent-014850 Whole Human Genome Microarray 4 × 44K G4112F | Microarray | Sorted cell (flow cytometry) | Decidua | Pooled | 1st trimester | Characterize decidual natural killer cells | Wang et al. (2014) |

| 2015 | NCBI GEO GSE59126 | Affymetrix Human Genome U133A Array | Microarray | Primary cell cultures | Chorionic villi (1st trimester), chorionic plate (3rd trimester) |

|

1st and 3rd trimester | Compare 1st trimester trophoblast vs 3rd trimester endothelial degradome | Ghaffari-Tabrizi-Wizsy et al. (2014) |

| 2015 | NCBI GEO GSE57834 | Affymetrix Human Gene Expression Array | Microarray | Sorted cell (flow cytometry) | Chorionic villi | 5 | 1st trimester | Characterize trophoblast subpopulations in early pregnancy | James et al. (2015) |

| 2017 | EBI ArrayExpress E-MTAB-5517 | Affymetrix Human Transcriptome Array 2.0 | Microarray | Sorted cell (flow cytometry) | Decidua | 6 | 3rd trimester | Characterize decidual T-cell populations | Powell et al. (2017) |

| 2017 | EBI EGA EGAD00001003705 (access requires approval) |

|

RNA-seq | Single cell | Chorionic villi | 8 | 3rd trimester | Characterize cells from term and early-onset pre-eclampsia-affected placentas | Tsang et al. (2017) |

| 2018 | NCBI GEO GSE79879 |

|

RNA-seq | Sorted cell (flow cytometry) | Decidua | 5 (pooled) | 1st trimester | Profile decidual natural killer cell population with expanded memory in subsequent pregnancy | Gamliel et al. (2018) |

| 2018 | NCBI GEO GSE89497 |

|

RNA-seq | Single cell with pre-sorting (magnetic bead) | Chorionic villi (1st trimester), basal plate (2nd trimester) |

|

1st and 2nd trimester | Characterize placental cell subpopulations | Liu et al. (2018) |

| 2018 | NCBI GEO GSE107824 | Illumina HumanHT-12 V4.0 Expression Beadchip | Microarray | Primary trophoblast cell culture | Chorionic villi |

|

1st, 2nd and 3rd trimester | Assess trophoblast differentiation across gestation | Soncin et al. (2018) |

| 2018 | NCBI SRA PRJNA492324 |

|

RNA-seq | Single cell and tissue | Chorionic villi, decidua | 9 | 1st trimester | Characterize cells from the first-trimester maternal–foetal interface | Suryawanshi et al. (2018) |

| 2018 | EBI ArrayExpress E-MTAB-6678 |

|

RNA-seq | Single cell with pre-sorting (flow cytometry) | Decidua | 5 | 1st trimester | Characterize cells from the first-trimester maternal–foetal interface | Vento-Tormo et al. (2018) |

| 2018 | EBI ArrayExpress E-MTAB-6701 |

|

RNA-seq | Single cell with pre-sorting (flow cytometry) | Chorionic villi, decidua | 7 | 1st trimester | Characterize cells from the first-trimester maternal–foetal interface | Vento-Tormo et al. (2018) |

| 2018 | NCBI GEO GSE124282 |

|

RNA-seq | Primary trophoblast cell culture | Chorionic villi |

|

2nd and 3rd trimester | Assess trophoblast differentiation across gestation (with linked ChIP sequencing data) | Wang et al. (2019a) |

|

| |||||||||

|

Gene expression variation and regulation | |||||||||

| 2006 | NCBI GEO GSE4421 | Stanford Functional Genomics Human cDNA Microarray | Microarray | Tissue | Amnion, basal plate, chorion, chorionic plate, chorionic villi, umbilical cord | 19 | 3rd trimester | Examine gene expression variation within the placenta and between closely associated tissues | Sood et al. (2006) |

| 2012 | NCBI GEO GSE36828 | Illumina HumanHT-12 V3.0 Expression Beadchip | Microarray | Tissue | Chorionic villi | 48 | 3rd trimester | Examine relationship of placental gene expression with methylation | Turan et al. (2012) |

| 2014 | NCBI GEO GSE56524 |

|

RNA-seq | Tissue | Whole placenta biopsy (basal plate + chorionic plate + chorionic villi) | 10 | 3rd trimester | Identify imprinted genes in the placenta | Metsalu et al. (2014) |

| 2015 | NCBI GEO GSE66622 |

|

RNA-seq | Tissue | Chorionic villi | 40 | 3rd trimester | Assess inter and intra-variation in placental transcriptome (African-American, European-American, South Asian and East Asian ancestry) | Hughes et al. (2015) |

| 2017 | NCBI GEO GSE77085 |

|

RNA-seq | Tissue | Chorionic villi | 16 | 3rd trimester | Identify gene co-expression patterns in normal term placenta | Buckberry et al. (2017) |

| 2018 | EBI ArrayExpress E-MTAB-6683 | Affymetrix Human Gene 2.1 ST Array | Microarray | Tissue | Chorionic villi | 8 | 1st trimester | Validate source and source-derived organoid | Turco et al. (2018) |

| 2019 | dbGaP Study Accession: phs001717.v1.p1 (access requires approval) |

|

RNA-seq | Tissue | Chorionic villi | 80 | 3rd trimester | Determine placental gene regulation (with linked genotyping and methylation data) | Delahaye et al. (2018) |

| 2019 | NCBI GEO GSE109120 |

|

RNA-seq | Tissue | Chorionic villi | 39 | 1st trimester | Sex: males vs females | Gonzalez et al. (2018) |

| Not publically available |

|

RNA-seq | Tissue | Amnion, chorion, basal plate | 5 (pooled) | 3rd trimester | Examine gene expression variation between placental-associated tissues | Kim et al. (2012) | |

| Not publically available |

|

RNA-seq | Tissue | Placenta biopsy (no details provided) | 20 | 3rd trimester | Identify placental-enriched genes compared to other tissue types | Saben et al. (2014b) | |

| Not publically available |

|

RNA-seq | Tissue | Chorionic villi | 159 | 3rd trimester | Determine expression quantitative trait loci in the placenta (with linked genotyping data) | Peng et al. (2017) | |

ChIP, chromatin immunoprecipitation; dbGaP, database for Genotypes and Phenotypes; EBI, European Bioinformatics Institute; EGA, European Genome-phenome Archive; GEO, Gene Expression Omnibus; M, million reads; NCBI, National Center for Biotechnology Information; SRA, sequence read archive.

Table II.

Pregnancy complications.

| Year | Accession ID | Platform | Type | Tissue/cell | Sampling location | Total no. | Gestation | Purpose | Associated publications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Pre-eclampsia | |||||||||

| 2006 | NCBI GEO GSE4707 | Agilent-012391 Whole Human Genome Oligo Microarray G4112A | Microarray | Tissue | Chorionic villi |

|

3rd trimester | EOPE or LOPE vs controls | Nishizawa et al. (2007) |

| 2007 | EBI ArrayExpress E-MEXP-1050 | Affymetrix GeneChip Human Genome Focus Array | Microarray | Tissue | Decidua |

|

3rd trimester | PE or IUGR vs controls | Eide et al. (2008) |

| 2007 | NCBI GEO GSE6573 | Affymetrix Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Array | Microarray | Tissue | Decidua, placenta biopsy (no details provided) |

|

3rd trimester | PE vs controls | Herse et al. (2007) |

| 2008 | NCBI GEO GSE12767 | Affymetrix Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Array | Microarray | Tissue | Chorionic villi |

|

1st trimester | Subsequent PE vs controls | Founds et al. (2009) |

| 2008 | NCBI GEO GSE10588 | Applied Biosystems Human Genome Survey Microarray Version 2 | Microarray | Tissue | Chorionic villi |

|

3rd trimester | PE vs controls | Sitras et al. (2009b) |

| 2009 | EBI ArrayExpress E-TABM-682 | Illumina Human-6 v2 Expression BeadChip | Microarray | Tissue | Decidua |

|

3rd trimester | PE or SGA vs controls | Loset et al. (2011) |

| 2009 | NCBI GEO GSE14722 | Affymetrix Human Genome U133A Array; Affymetrix Human Genome U133B Array | Microarray | Tissue | Basal plate |

|

3rd trimester | PE vs preterm controls | Winn et al. (2009) |

| 2010 | NCBI GEO GSE24129 | Affymetrix Human Gene 1.0 ST Array | Microarray | Tissue | Chorionic villi |

|

3rd trimester | PE or IUGR vs controls | Nishizawa et al. (2011) |

| 2010 | NCBI GEO GSE25906 | Illumina humanWG-6 V2.0 Expression Beadchip | Microarray | Tissue | Chorionic villi |

|

3rd trimester | PE vs controls | Tsai et al. (2011) |

| 2011 | NCBI GEO GSE22526 | Operon Human Genome Array Ready Oligo Set version 2.1 | Microarray | Tissue | Placenta biopsy (basal plate + chorionic villi) |

|

3rd trimester | EOPE vs LOPE | Junus et al. (2012) |

| 2011 | NCBI GEO GSE30186 | Illumina HumanHT-12 V4.0 Expression Beadchip | Microarray | Tissue | Chorionic villi |

|

3rd trimester | PE vs controls | Meng et al. (2012) |

| 2012 | NCBI GEO GSE25861 | Affymetrix Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Array | Microarray | Sorted cells (magnetic beads) | Chorionic villi |

|

3rd trimester | Placental endothelial cells in PE with IUGR vs preterm controls | Dunk et al. (2012) |

| 2012 | NCBI GEO GSE35574 | Illumina HumanWG-6 V2.0 Expression Beadchip | Microarray | Tissue | Chorionic villi |

|

3rd trimester | PE or IUGR vs controls | Guo et al. (2013) |

| 2013 | NCBI GEO GSE44711 | Illumina HumanHT-12 V4.0 Expression Beadchip | Microarray | Tissue | Chorionic villi |

|

3rd trimester | EOPE vs preterm controls (with linked methylation data) | Blair et al. (2013) |

| 2013 | NCBI GEO GSE47187 | Agilent-028004 SurePrint G3 Human GE 8 × 60K Microarray | Microarray | Tissue | Chorionic villi |

|

3rd trimester | PE vs preterm controls | Song et al. (2013) |

| 2013 | NCBI GEO GSE43942 | NimbleGen Homo sapiens HG18 090828 opt expr HX12 (12 × 135k) | Microarray | Tissue | Placenta biopsy (basal plate + chorionic villi) |

|

3rd trimester | PE vs controls | Xiang et al. (2013) |

| 2014 | NCBI GEO GSE54618 | Illumina HumanHT-12 V4.0 Expression Beadchip | Microarray | Tissue | Chorionic villi |

|

3rd trimester | PE vs controls | Jebbink et al. (2015) |

| 2015 | EBI ArrayExpress E-MTAB-3265 | Illumina HumanHT-12 V3.0 Expression BeadChip | Microarray | Tissue | Chorionic villi |

|

1st trimester | High risk vs low risk of PE (based on uterine artery Doppler resistance index) | Leslie et al. (2015) |

| 2015 | NCBI GEO GSE74341 | Agilent-039494 SurePrint G3 Human GE v2 8 × 60K | Microarray | Tissue | Chorionic villi |

|

3rd trimester | EOPE or LOPE vs controls | Liang et al. (2016) |

| 2015 | NCBI GEO GSE73374 | Affymetrix Human Gene 2.0 ST Array | Microarray | Tissue | Whole placenta biopsy (basal plate + chorionic plate + chorionic villi) |

|

3rd trimester | PE vs controls (with linked methylation data) | Martin et al. (2015) |

| 2015 | NCBI GEO GSE60438 | Illumina HumanWG-6 V3.0 Expression Beadchip; Illumina HumanHT-12 V4.0 Expression Beadchip | Microarray | Tissue | Decidua |

|

3rd trimester | PE vs controls | Yong et al. (2015) |

| 2016 | NCBI GEO GSE75010 | Affymetrix Human Gene 1.0 ST Array | Microarray | Tissue | Placenta biopsy (basal plate + chorionic villi) |

|

3rd trimester | PE vs controls (with linked methylation and histological data) | Leavey et al. (2016); Christians et al. (2017); Leavey et al. (2018); Benton et al. (2018); Gibbs et al. (2019) |

| 2017 | NCBI GEO GSE94643 | Affymetrix Human Gene 2.0 ST Array | Microarray | Tissue | Decidua |

|

3rd trimester | Decidualization in PE vs preterm controls | Garrido-Gomez et al. (2017) |

| 2017 | NCBI GEO GSE93839 | Affymetrix Human Gene 2.0 ST Array | Microarray | Tissue (laser microdissected) | Placenta biopsy (basal plate + chorionic villi) |

|

3rd trimester | Trophoblast populations in PE vs preterm controls | Gormley et al. (2017) |

| 2017 | NCBI GEO GSE99007 | Agilent SurePrint G3 Human GE v3 8 × 60K Microarray | Microarray | Primary cell culture | Chorionic villi |

|

3rd trimester | Fibroblasts from PE vs controls | Ohmaru-Nakanishi et al. (2018) |

| 2017 | EBI EGA EGAD00001003705 (access requires approval) | Illumina NextSeq 500 -mean sequencing depth ∼21 471 reads | RNA-seq | Single cell | Chorionic villi |

|

Late 2nd and 3rd trimester | EOPE vs controls | Tsang et al. (2017) |

| 2018 | NCBI GEO GSE96984 | Agilent-078298 human ceRNA array V1.0 4X180K | Microarray | Tissue | Basal plate |

|

3rd trimester | PE vs controls | Unpublished |

| 2018 | NCBI GEO GSE66273 | Agilent-014850 Whole Human Genome Microarray 4 × 44K G4112F | Microarray | Tissue | Chorionic villi |

|

3rd trimester | EOPE vs preterm controls | Than et al. (2018); Varkonyi et al. (2011) |

| 2019 | NCBI GEO GSE102897 | Agilent-078298 human ceRNA array V1.0 4X180K | Microarray | Tissue | Chorionic villi |

|

3rd trimester | PE vs controls | Hu et al. (2018a) |

| Not publically available, but available on request | CapitalBio Genomewide Microarray | Microarray | Tissue | Chorionic villi |

|

3rd trimester | PE vs controls | Zhou et al. (2006) | |

| Not publically available | Affymetrix Human Genome U133 Plus 2 | Microarray | Tissue | Placenta biopsy (no details provided) |

|

3rd trimester | PE with IUGR vs controls | Jarvenpaa et al. (2007) | |

| Not publically available | Operon Human Genome Array Ready Oligo Set version 2.1 | Microarray | Tissue | Placenta biopsy (basal plate + chorionic villi) |

|

3rd trimester | PE vs controls | Enquobahrie et al. (2008) | |

| Not publically available | Affymetrix Human Genome U133A Array | Microarray | Tissue | Placenta biopsy (basal plate + chorionic villi) |

|

3rd trimester | PE vs controls | Hoegh et al. (2010) | |

| Not publically available | Agilent Human Genome Microarray 4 × 44K | Microarray | Tissue | Chorionic villi |

|

3rd trimester | PE vs controls | Lee et al. (2010) | |

| Not publically available | Operon Human Genome Array Ready Oligo Set versions 2.1 and 2.1.1 | Microarray | Tissue | Chorionic villi |

|

3rd trimester | PE vs controls (with Doppler findings) | Centlow et al. (2011) | |

| Not publically available | GE Healthcare Codelink Human Whole Genome Bioarrays | Microarray | Tissue | Placenta biopsy (basal plate + chorionic plate + chorionic villi) |

|

3rd trimester | PE vs controls | Kang et al. (2011) | |

| Not publically available | Illumina HumanRef-12 v3 Expression BeadChip | Microarray | Tissue | Chorionic villi |

|

3rd trimester | PE or PTL vs TNL (with linked miRNA data) | Mayor-Lynn et al. (2011) | |

| Not publically available |

|

RNA-seq | Tissue | Placental biopsy (basal plate + chorionic plate + chorionic villi) |

|

3rd trimester | LOPE, GDM, SGA or LGA vs controls | Sober et al. (2015) | |

| Not publically available |

|

RNA-seq | Tissue | Chorionic villi |

|

3rd trimester | LOPE or GDM vs controls | Lekva et al. (2016) | |

| Not publically available |

|

RNA-seq | Tissue | Decidua |

|

3rd trimester | EOPE or LOPE vs controls | Tong et al. (2018) | |

|

| |||||||||

|

Intrauterine growth restriction/small for gestational age | |||||||||

| 2007 | EBI ArrayExpress E-MEXP-1050 | Affymetrix GeneChip Human Genome Focus Array | Microarray | Tissue | Decidua |

|

3rd trimester | IUGR or PE vs controls | Eide et al. (2008) |

| 2008 | NCBI GEO GSE12216 | ABI Human Genome Survey Microarray Version 2 | Microarray | Tissue | Chorionic villi |

|

3rd trimester | IUGR with placental insufficiency vs controls | Sitras et al. (2009a) |

| 2009 | EBI ArrayExpress E-TABM-682 | Illumina Human-6 v2 Expression BeadChip | Microarray | Tissue | Decidua |

|

3rd trimester | SGA or PE vs controls | Loset et al. (2011) |

| 2010 | NCBI GEO GSE24129 | Affymetrix Human Gene 1.0 ST Array | Microarray | Tissue | Chorionic villi |

|

3rd trimester | IUGR or PE vs controls | Nishizawa et al. (2011) |

| 2012 | NCBI GEO GSE25861 | Affymetrix Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Array | Microarray | Sorted cells (magnetic bead) | Chorionic villi |

|

3rd trimester | Placental endothelial cells in IUGR with PE vs preterm controls | Dunk et al. (2012) |

| 2012 | NCBI GEO GSE35574 | Illumina HumanWG-6 V2.0 Expression Beadchip | Microarray | Tissue | Chorionic villi |

|

3rd trimester | IUGR or PE vs controls | Guo et al. (2013) |

| 2014 | EBI ArrayExpress E-MTAB-1956 | NimbleGen Human HG18 60mer 4 × 72K Expression Array | Microarray | Tissue | Chorionic villi |

|

3rd trimester | IUGR vs control | Madeleneau et al. (2015) |

| 2017 | NCBI SRA PRJNA358255 |

|

RNA-seq | Tissue | Placenta biopsy (chorionic plate + chorionic villi) |

|

3rd trimester | SGA or LGA vs controls | Deyssenroth et al. (2017) |

| 2018 | NCBI GEO GSE100415 | Affymetrix Human Gene 1.0 ST Array | Microarray | Tissue | Placenta biopsy (basal plate + chorionic villi) |

|

3rd trimester | Normotensive suspected IUGR only (extension of earlier study comparing healthy controls and hypertensive suspected IUGR) | Gibbs et al. (2019) (extension of GSE75010) |

| 2018 | Available as supplementary data within journal article |

|

RNA-seq | Tissue | Placenta biopsy (basal plate + chorionic villi) |

|

3rd trimester | IUGR vs controls in women with and without chemotherapy during pregnancy | Verheecke et al. (2018) |

| 2019 | EBI ENA PRJEB30656 |

|

RNA-seq | Tissue | Placenta biopsy (no details provided) |

|

3rd trimester | IUGR vs controls | Majewska et al. (2019) |

| Not publically available | Affymetrix U95A Microarray | Microarray | Tissue | Placenta biopsy (no details provided) |

|

3rd trimester | IUGR vs controls | Roh et al. (2005) | |

| Not publically available | Affymetrix Human Genome U133 Plus 2 | Microarray | Tissue | Placenta biopsy (no details provided) |

|

3rd trimester | IUGR with PE vs controls | Jarvenpaa et al. (2007) | |

| Not publically available | Affymetrix Human Genome U133A Array | Microarray | Tissue | Placenta biopsy (basal plate + chorionic villi) |

|

3rd trimester | IUGR vs controls | McCarthy et al. (2007) | |

| Not publically available | Affymetrix Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Array | Microarray | Tissue | Placenta biopsy (chorionic plate + chorionic villi) |

|

3rd trimester | IUGR vs preterm controls | Struwe et al. (2010) | |

| Not publically available | Affymetrix Human Genome U219 Array | Microarray | Tissue | Chorionic villi |

|

3rd trimester | IUGR or macro vs controls | Sabri et al. (2014) | |

| Not publically available |

|

RNA-seq | Tissue | Placental biopsy (basal plate + chorionic plate + chorionic villi) |

|

3rd trimester | SGA, LGA or PE or GDM vs controls | Sober et al. (2015) | |

|

| |||||||||

|

Macrosomia/large for gestational age | |||||||||

| 2017 | NCBI SRA PRJNA358255 |

|

RNA-seq | Tissue | Placenta biopsy (chorionic plate + chorionic villi) |

|

3rd trimester | LGA or SGA vs controls | Deyssenroth et al. (2017) |

| Not publically available | Affymetrix Human Genome U219 Array | Microarray | Tissue | Chorionic villi |

|

3rd trimester | Macro or IUGR vs controls | Sabri et al. (2014) | |

| Not publically available |

|

RNA-seq | Tissue | Placental biopsy (basal plate + chorionic plate + chorionic villi) |

|

3rd trimester | LGA, SGA, PE or GDM vs controls | Sober et al. (2015) | |

| Not publically available | Arraystar Human LncRNA Microarray V3.0 | Microarray | Tissue | Placenta biopsy (basal plate + chorionic villi) |

|

3rd trimester | Non-diabetes macro vs controls | Song et al. (2018) | |

|

| |||||||||

|

Gestational diabetes mellitus | |||||||||

| 2005 | NCBI GEO GSE2956 | Affymetrix Human U133 Array | Microarray | Tissue | Chorionic villi | 15 −8 C −7 GDM |

3rd trimester | GDM vs controls | Radaelli et al. (2003) |

| 2015 | NCBI GEO GSE70493 | Affymetrix Human Transcriptome Array 2.0 | Microarray | Tissue | Placenta biopsy (basal plate + chorionic villi) |

|

3rd trimester | GDM vs controls (with linked methylation data) | Binder et al. (2015) |

| Not publically available | Operon Human Genome Array Ready Oligo Set version 2.1 | Microarray | Tissue | Chorionic villi |

|

3rd trimester | GDM vs controls | Enquobahrie et al. (2009) | |

| Not publically available | Affymetrix Human U133 Array | Microarray | Tissue | Chorionic villi |

|

3rd trimester | GDM or T1D vs controls | Radaelli et al. (2009) | |

| Not publically available |

|

RNA-seq | Tissue | Placental biopsy (basal plate + chorionic plate + chorionic villi) |

|

3rd trimester | GDM, PE, SGA or LGA vs controls | Sober et al. (2015) | |

| Not publically available | Affymetrix HuGene ST 1.0 Array | Microarray | Tissue (laser microdissected) | Placenta biopsy (no details provided) |

|

3rd trimester | GDM vs obese non-diabetic vs lean controls | Bari et al. (2016) | |

| Not publically available |

|

RNA-seq | Tissue | Placenta biopsy (no details provided) |

|

3rd trimester | GDM vs controls (with linked miRNA data) | Ding et al. (2018) | |

| Not publically available |

|

RNA-seq | Tissue | Chorionic villi |

|

3rd trimester | GDM or LOPE vs controls | Lekva et al. (2016) | |

| Not publically available, but available on request |

|

RNA-seq | Tissue | Placenta biopsy (chorionic plate + chorionic villi) |

|

3rd trimester | Diabetes during pregnancy (GDM and T2D) vs controls (with linked methylation data) | Alexander et al. (2018) | |

|

| |||||||||

|

Antenatal infections and inflammation | |||||||||

| 2007 | NCBI GEO GSE7586 | Affymetrix Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Array | Microarray | Tissue | Chorionic villi |

|

3rd trimester | Active placental malaria vs controls | Muehlenbachs et al. (2007) |

| 2009 | EBI ArrayExpress E-TABM-577 | Affymetrix Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 | Microarray | Tissue | Chorionic villi |

|

3rd trimester | Idiopathic PI vs controls | Kim et al. (2009) |

| 2015 | NCBI GEO GSE68474 | Illumina HumanHT-12 WG V4.0 Expression Beadchip | Microarray | Tissue | Placental biopsy (basal plate + chorionic villi) |

|

3rd trimester | Chronic PI vs controls | Raman et al. (2015) |

| 2016 | NCBI GEO GSE73712 |

|

RNA-seq | Tissue | Chorionic villi, decidua |

|

3rd trimester | Preterm with PI or preterm without PI vs controls | Ackerman et al. (2016) |

| 2018 | NCBI GEO GSE107376 |

|

RNA-seq | Tissue | Placenta biopsy (basal plate + chorionic plate + chorionic villi) |

|

3rd trimester | TrypC+ vs controls | Juiz et al. (2018) |

|

Labour | |||||||||

| 2009 | NCBI GEO GSE18809 | Affymetrix Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Array | Microarray | Tissue | Chorionic villi |

|

3rd trimester | PTSL vs TSL | Chim et al. (2012) |

| 2009 | NCBI GEO GSE18850 | Affymetrix Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Array | Microarray | Tissue | Chorionic villi |

|

3rd trimester | TSL vs TNL | Chim et al. (2012) |

| 2016 | NCBI GEO GSE73685 | Affymetrix Human Gene 1.0 ST Array | Microarray | Tissue | Amnion, chorion, decidua, placenta biopsy (no details provided) |

|

3rd trimester | Preterm vs term with and without labour | Bukowski et al. (2017) |

| 2017 | EBI ArrayExpress E-MTAB-5353 | Illumina Human HT-12 WG V4.0 Expression Beadchip | Microarray | Tissue | Decidua |

|

3rd trimester | Preterm vs term with and without labour | Rinaldi et al. (2017) |

| Not publically available | Illumina HumanRef-12 v3 Expression BeadChip | Microarray | Tissue | Chorionic villi |

|

3rd trimester | PTL or PE vs TNL (with linked miRNA data) | Mayor-Lynn et al. (2011) | |

|

| |||||||||

|

Recurrent miscarriage | |||||||||

| 2010 | NCBI GEO GSE22490 | Affymetrix Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Array | Microarray | Tissue | Placenta biopsy (chorionic villi + basal plate) |

|

1st and 2nd trimester | RM vs controls | Rull et al. (2013) |

| 2016 | NCBI GEO GSE76862 | Affymetrix GeneChip Human Transcriptome Array 2.0 | Microarray | Primary cell culture | Chorionic villi | Not stated (pooled into 6 groups of 3 to 5 samples) | 1st trimester | Placental trophoblast cells from RM vs controls | Tian et al. (2016) |

| 2018 | NCBI GEO GSE121950 |

|

RNA-seq | Tissue | Chorionic villi |

|

1st trimester | RM vs controls | Huang et al. (2018) |

| 2018 | NCBI GEO GSE113790 |

|

RNA-seq | Tissue | Decidua |

|

1st trimester | RM vs controls (with linked methylation data) | Yu et al. (2018) |

| Not publically available |

|

RNA-seq | Tissue | Chorionic villi |

|

1st trimester | RM vs controls | Sober et al. (2016) | |

|

| |||||||||

|

Chromosomal abnormalities | |||||||||

| 2015 | NCBI GEO GSE70102 | Affymetrix Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Array | Microarray | Tissue | Basal plate |

|

2nd trimester | Aneupoidy vs controls | Bianco et al. (2016) |

| Not publically available | Affymetrix GeneChip Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Array | Microarray | Tissue | Chorionic villi |

|

1st trimester | T21 vs controls | Lim et al. (2017a) | |

|

| |||||||||

|

Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy | |||||||||

| 2013 | NCBI GEO GSE46157 | Agilent-026652 Whole Human Genome Microarray 4 × 44K v2 | Microarray | Tissue | Chorionic villi |

|

3rd trimester | IHCP vs controls | Du et al. (2014) |

C, control; ENA, European Nucleotide Archive; EOPE, early-onset pre-eclampsia; GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus; HELLP, haemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low-platelet count syndrome; IHCP, intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy; iPTB, idiopathic preterm birth; IUGR, intrauterine growth restriction; LGA, large for gestational age; LOPE, late-onset pre-eclampsia; macro, macrosomia; miRNA, microRNA; PE, pre-eclampsia; PI – placental inflammation; PTL, preterm labour; PTNL, preterm no labour; PTSL, preterm spontaneous labour; RM, recurrent miscarriage; SGA, small for gestational age; T13, trisomy 13; T18, trisomy 18; T21, trisomy 21; T1D, type 1 diabetes; T2D, type 2 diabetes; TL, term labour; TNL, term no labour; TSL, term spontaneous labour; TrypC+, Trypanosoma cruzi seropositive.

Table III.

Pregnancy exposures.

| Year | Accession ID | Platform | Type | Tissue/cell | Sampling location | Total no. | Gestation | Purpose | Associated publications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Obesity | |||||||||

| 2013 | EBI ArrayExpress E-MTAB-4541 | Affymetrix Human Gene 2.0 ST Array | Microarray | Tissue | Chorionic villi |

|

3rd trimester | Obese vs lean before pregnancy | Altmae et al. (2017) |

| 2018 | NCBI SRA PRJNA478464 | Illumina NextSeq 500 -mean sequencing depth ∼31M | RNA-seq | Tissue | Placenta biopsy (no details provided) |

|

3rd trimester | Obese vs lean before pregnancy | Sureshchandra et al. (2018) |

| 2019 | NCBI GEO GSE128381 | Agilent-039494 SurePrint G3 Human GE v2 8 × 60K 039381 | Microarray | Tissue | Chorionic villi |

|

3rd trimester | Across a continuum of maternal pre-pregnancy BMI including 41% overweight or obese | Cox et al. (2019) |

| Not publically available |

|

RNA-seq | Tissue | Placenta biopsy (no details provided) |

|

3rd trimester | Obese vs lean before pregnancy | Saben et al. (2014a) | |

| Not publically available | Affymetrix HuGene ST 1.0 Array | Microarray | Tissue (laser microdissected) | Placenta biopsy (no details provided) |

|

3rd trimester | GDM vs obese non-diabetic vs lean controls | Bari et al. (2016) | |

|

| |||||||||

|

Smoking | |||||||||

| 2007 | NCBI GEO GSE7434 | Affymetrix Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Array | Microarray | Tissue | Placenta biopsy (no details provided) |

|

3rd trimester | Smoking vs non-smoking controls | Huuskonen et al. (2008) |

| 2009 | NCBI GEO GSE18044 | Illumina humanRef-8 v2.0 Expression Beadchip | Microarray | Tissue | Chorionic villi |

|

3rd trimester | Smoking vs non-smoking controls | Bruchova et al. (2010) |

| 2011 | NCBI GEO GSE27272 | Illumina HumanRef-8 V3.0 Expression Beadchip | Microarray | Tissue | Chorionic villi |

|

3rd trimester | Smoking vs non-smoking controls | Votavova et al. (2011) |

| 2011 | NCBI GEO GSE30032 | Illumina HumanRef-8 V3.0 Expression Beadchip | Microarray | Tissue | Chorionic villi |

|

3rd trimester | Passive smokers vs non-smoking controls | Votavova et al. (2012) |

|

Clinical trials | |||||||||

| 2012 | NCBI GEO GSE39290 | Agilent-014850 Whole Human Genome Microarray 4 × 44K G4112F | Microarray | Tissue | Placenta biopsy (basal plate + chorionic plate + chorionic villi) |

|

3rd trimester | High vs low choline intake in third trimester | Jiang et al. (2013) |

| 2014 | NCBI GEO GSE53291 | Affymetrix NuGO array (human) NuGO_Hs1a520180 | Microarray | Tissue | Chorionic villi |

|

3rd trimester | Omega-3 supplementation vs placebo | Sedlmeier et al. (2014) |

| 2015 | EBI ArrayExpress E-MTAB-6418 | Illumina HumanHT-12 V4.0 Expression Beadchip | Microarray | Tissue | Placenta biopsy (basal plate + chorionic plate + chorionic villi) |

|

3rd trimester | Obese women treated with metformin vs placebo | Chiswick et al. (2016) |

|

| |||||||||

|

IVF | |||||||||

| 2018 | NCBI GEO GSE122214 | Affymetrix Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Array | Microarray | Tissue | Chorionic villi |

|

1st trimester | IVF vs controls | Zhao et al. (2019) |

| Not publically available | Affymetrix GeneChip Human Gene 1.0 ST Array | Microarray | Tissue | Chorionic villi |

|

3rd trimester | IVF vs controls | Nelissen et al. (2014) | |

| Not publically available |

|

RNA-seq | Tissue | Chorionic villi |

|

1st trimester | IVF or non-IVF fertility treated vs controls | Lee et al. (2019) | |

|

| |||||||||

|

Antenatal depression | |||||||||

| 2014 | Available as supplementary data within journal article | Affymetrix GeneChip Human Gene 1.0 ST Array | Microarray | Tissue | Placenta biopsy (chorionic plate + chorionic villi) |

|

3rd trimester | Depressed women with and without SSRI treatment vs controls | Olivier et al. (2014) |

IVF, in vitro fertilisation; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

Table IV.

In vitro placental cultures.

| Year | Accession ID | Platform | Type | Model | Treatment | Source | Purpose | Associated publications | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Trophoblast cultures | |||||||||

| 2004 | NCBI GEO GSE1302 | Affymetrix Human Genome U95B Array, Affymetrix Human Genome U95C Array, Affymetrix Human Genome U95D Array, Affymetrix Human Genome U95E Array, Affymetrix Human Genome U95 Version 2 Array | Microarray | Primary cytotrophoblast culture | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma ligand GW7845 | Term placenta | Assess accuracy of microarray data | Mecham et al. (2004) | |

| 2005 | NCBI GEO GSE2531 | Affymetrix Human Genome U133A Array | Microarray | Cytrophoblast cell lines | None | JEG-3 and BeWo | Compare trophoblast cell lines | Burleigh et al. (2007) | |

| 2008 | NCBI GEO GSE13475 | Affymetrix Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Array | Microarray | Cytrophoblast cell lines | Transfected with STOX1 overexpression plasmid | JEG-3 | Determine effect of STOX1 overexpression on trophoblast function | Rigourd et al. (2008) | |

| 2010 | NCBI GEO GSE20510 | Affymetrix Human Genome U133A Array | Microarray | Cytotrophoblast and extravillous trophoblast cell lines | None | SGHPL-5, HTR-8/SVneo, BeWo, JEG-3 and ACH-3P | Compare trophoblast cell lines | Bilban et al. (2010) | |

| 2011 | EBI ArrayExpress E-MEXP-2800 | Agilent Whole Human Genome Microarray 4 × 44K 014850 G4112F | Microarray | Cytotrophoblast cell line | Infected with Coxiella burnetii | BeWo | Determine pathways of Coxiella burnetii (Q fever) placental infection in trophoblast | Ben Amara et al. (2010) | |

| 2011 | NCBI GEO GSE27909 | Affymetrix Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Array | Microarray | Extravillous trophoblast cell line | Hoechst dye | HTR-8/SVneo | Compare side population (consists of stem and progenitor cells) and non-side trophoblast population | Takao et al. (2011) | |

| 2011 | NCBI GEO GSE20404 | Affymetrix Human Gene 1.0 ST Array | Microarray | Cytotrophoblast cell line | Heme oxygenase-1 silencing | BeWo | Assess effect of HO-1 silencing on trophoblast cell adhesion | Tauber et al. (2010) | |

| 2011 | NCBI GEO GSE31679 | Illumina HumanHT-12 V3.0 expression beadchip | Microarray | Extravillous trophoblast cell line | Cobalt chloride, interleukin-1-beta, tumour necrosis factor alpha | Swan-71 | Assess effects of chemical hypoxia and pro-inflammatory cytokines on trophoblast function | Unpublished | |

| 2012 | NCBI GEO GSE40182 | Affymetrix Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Array | Microarray | Primary cytotrophoblast culture | Exposed to pre-eclampsia in vivo | 3rd trimester placenta | Assess long-term effect of exposure to pre-eclampsia in vivo on trophoblast | Zhou et al. (2013) | |

| 2012 | NCBI GEO GSE30330 | Agilent Whole Human Genome Microarray 4 × 44K 014850 G4112F | Microarray | Cytotrophoblast cell line | Infected with Coxiella burnetii | JEG3 | Determine pathways of Coxiella burnetii (Q fever) placental infection in trophoblast | Unpublished | |

| 2012 | NCBI GEO GSE41441 | Agilent-012391 Whole Human Genome Oligo Microarray G4112A | Microarray | Cytotrophoblast cell line | Valproic acid | JEG-3 | Determine adverse effects of valproic acid on trophoblast | Unpublished | |

| 2013 | NCBI GEO GSE49922 | Agilent-028004 SurePrint G3 Human GE 8 × 60K Microarray | Microarray | Primary cytotrophoblast culture | Irradiation | Term placenta | Determine irradiated trophoblast response | Kanter et al. (2014) | |

| 2013 | NCBI GEO GSE41331 | Illumina HumanHT-12 V4.0 Expression Beadchip | Microarray | Primary cytotrophoblast culture | Hypoxia | Term placenta | Determine hypoxic trophoblast response | Yuen et al. (2013) | |

| 2014 | EBI ArrayExpress E-MTAB-429 | Illumina HumanHT-12 v3.0 Expression BeadChip | Microarray | Cytotrophoblast and extravillous trophoblast primary culture and cell lines | None | First-trimester placenta, JAR and JEG-3 | Compare trophoblast cell lines | Apps et al. (2011) | |

| 2014 | NCBI GEO GSE56564 | Agilent-028004 SurePrint G3 Human GE 8 × 60K Microarray | Microarray | Primary cytotrophoblast culture and extravillous trophoblast cell line | Transfected with plasmid for C19MC miRNA expression | Term placenta; HTR-8/SVneo | Determine effect of C19MC miRNA on trophoblast function | Xie et al. (2014) | |

| 2015 | NCBI GEO GSE60432 | Agilent-028004 SurePrint G3 Human GE 8 × 60K Microarray | Microarray | Primary cytotrophoblast culture | Hypoxia | Term placenta | Determine hypoxic trophoblast response | Unpublished | |

| 2016 | NCBI GEO GSE79333 | Stanford Functional Genomics Facility SHDZ | Microarray | Primary cytotrophoblast and syncytiotrophoblast culture | In vitro differentiation | Term placenta | Characterize in vitro cytotrophoblast differentiation | Rouault et al. (2016) | |

| 2016 | NCBI GEO GSE73016 |

|

RNA-seq | Primary cytrophoblast culture | Time course differentiation | Term placenta | Compare synctytiotrophoblast derived from placenta and human pluripotent stem cells | Yabe et al. (2016) | |

| 2017 | NCBI GEO GSE98523 | Applied Biosystems Human Genome Survey Microarray Version 2 | Microarray | Cytotrophoblast cell line | In vitro differentiation with forskolin | BeWo | Characterize in vitro cytotrophoblast differentiation | Gauster et al. (2018) | |

| 2017 | NCBI GEO GSE86171 | Affymetrix Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Array | Microarray | Primary cytotrophoblast culture | In vitro differentiation with Matrigel | 2nd trimester placenta | Characterize in vitro cytotrophoblast differentiation | Robinson et al. (2017) | |

| 2017 | NCBI SRA PRJNA383955 |

|

RNA-seq | Cytotrophoblast cell line | Dexamethasone | Not stated, obtained from cell bank | Determine trophoblast response to dexamethasone | Shang et al. (2018) | |

| 2018 | NCBI SRA PRJNA397241 |

|

RNA-seq | Primary cytotrophoblast culture and cell line | In vitro differentiation by time course or with forskolin | Term placenta and BeWo | Characterize in vitro cytotrophoblast differentiation | Azar et al. (2018) | |

| 2018 | NCBI GEO GSE65866 | Illumina HumanHT-12 V4.0 Expression Beadchip | Microarray | Cytotrophoblast cell line | ZNF554 silencing | BeWo | Determine role of ZNF554 in trophoblast function | Than et al. (2018) | |

| 2018 | NCBI GEO GSE65940 | Illumina HumanHT-12 V4.0 Expression Beadchip | Microarray | Extravillous trophoblast cell line | ZNF554 silencing | HTR-8/SVneo | Determine role of ZNF554 in trophoblast function | Than et al. (2018) | |

| 2018 | NCBI GEO GSE66304 |

|

RNA-seq | Cytotrophoblast cell line | PEG10 silencing | JEG-3 | Determine role of PEG10 in trophoblast function | Unpublished | |

| 2018 | NCBI GEO GSE118351 | Affymetrix Human Gene Expression Array | Microarray | Primary cytotrophoblast culture | Time course differentiation | Term placenta | Characterize in vitro cytotrophoblast differentiation | Unpublished | |

| 2019 | NCBI GEO GSE125778 |

|

RNA-seq | Extravillous trophoblast cell line | Interferon-gamma | HTR-8/SVneo | Assess effect of interferon-gamma on trophoblast invasion | Verma et al. (2018) | |

| 2019 | NCBI GEO GSE124586 |

|

RNA-seq | Extravillous trophoblast cell line | Epidermal growth factor | HTR-8/SVneo | Assess effect of epidermal growth factor on trophoblast invasion | Unpublished | |

| 2019 | NCBI GEO GSE127170 | Affymetrix Human Gene 1.0 ST Array | Microarray | Cytotrophoblast cell line | In vitro differentiation with forskolin | BeWo and JEG-3 | Identify genes associated with trophoblast fusion | Unpublished | |

| Not publically available | Affymetrix U95A array | Microarray | Primary cytotrophoblast culture | Hypoxia | Term placenta | Determine hypoxic trophoblast response | Roh et al. (2005) | ||

| Not publically available |

|

RNA-seq | Cytotrophoblast cell line | In vitro differentiation with forskolin | BeWo | Assess relationship of cell fusion transcriptome with methylome | Shankar et al. (2015) | ||

| Not publically available | Affymetrix Human Gene 1.1 ST Array | Microarray | Primary cytotrophoblast culture | Insulin | 1st trimester placenta | Investigate the effects of obesity and insulin on trophoblast | Lassance et al. (2015) | ||

| Not publically available |

|

RNA-seq | Cytotrophoblast cell line | In vitro differentiation with forskolin | BeWo | Identify syncytialization-related genes in trophoblast | Zheng et al. (2016) | ||

|

Non-trophoblast cultures | |||||||||

| 2006 | NCBI GEO GSE5809 | Affymetrix Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Array | Microarray | Primary decidualized stromal cell culture | Conditioned medium from primary first or second trimester trophoblast | Endometrial biopsy | Determine decidual response to trophoblast secretions/paracrine signals | Hess et al. (2007) | |

| 2010 | NCBI GEO GSE21332 | Illumina HumanWG-6 v3.0 Expression Beadchip | Microarray | Primary pericyte culture | None | Term placenta | Compare pericytes by tissue source | Maier et al. (2010) | |

| 2011 | EBI ArrayExpress E-MEXP-3299 | Applied Biosystems Human Genome Survey Microarray v2.0 | Microarray | Primary placental endothelial cell culture | Foetal HDL | Term placenta | Identify apoE-HDL regulated genes in placental endothelium | Augsten et al. (2011) | |

| 2013 | NCBI GEO GSE41946 | Agilent-014850 Whole Human Genome Microarray 4 × 44K G4112F | Microarray | Primary decidual endothelial culture | None | 1st trimester placenta | Compare immunoregulatory and pro-angiogenic functions of endothelial cells relative to tissue of origin | Agostinis et al. (2019) | |

| 2016 | NCBI GEO GSE58220 | Affymetrix Human Gene 2.0 ST Array | Microarray | Primary decidual stromal cell culture | Interleukin-1-beta | Term placenta | Determine decidual response to cytokine challenge | Ibrahim et al. (2016) | |

|

| |||||||||

|

In vitro models of in vivo exposures | |||||||||

| 2012 | NCBI GEO GSE36083 | Affymetrix Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Array | Microarray | Primary explants | Antiphospholipid antibodies | 1st trimester placenta | Determine trophoblast response to antiphospholipid antibodies | Pantham et al. (2012) | |

| 2017 | NCBI GEO GSE104348 | Illumina HiSeq 2500-mean sequencing depth ∼65M | RNA-seq | Primary explants | Interferon-beta or interferon-lambda | 2nd trimester placenta | Assess placental response to different interferons (in the context of Zika virus infection) | Yockey et al. (2018) | |

| 2018 | NCBI GEO GSE113155 | Agilent-039494 SurePrint G3 Human GE v2 8 × 60K Microarray 039381 | Microarray | Primary explants | Infected with Trypanosoma cruzi | Term placenta | Assess placental response to Trypanosoma cruzi infection | Castillo et al. (2018) | |

| Not publically available |

|

RNA-seq | Primary decidual and chorionic villus organoid cultures | Infected with Zika virus | 1st trimester placenta | Assess decidual and chorion response to Zika virus infection | Weisblum et al. (2017) | ||

HDL, high-density lipoprotein.

Important considerations for placental transcriptome studies

Good study design is critical to harness the potential of genome-wide transcript profiling of the placenta. Key aspects to be considered in study design are subject recruitment, sample processing at delivery, transcript profiling and data analysis methods and data validation (Fig. 1), all of which may represent potential pitfalls and limit the validity of conclusions that can be drawn.

Figure 1.

Key aspects to consider for placental transcriptome studies.

Subject recruitment

Two main points to consider in subject recruitment are selection criteria and sample size. Firstly, the selection process in case–control studies should ensure suitable controls are chosen to compare with pathological cases identified by well-defined and established clinical definitions. As will be discussed in subsequent sections, varied clinical criteria can impact study findings and reproducibility. Hence, a consensus about research definitions of common pregnancy complications should be reached to make full use of available resources. The selection process must also determine if variables, such as gestational age, sex, labour status, mode of delivery and treatment modalities, which are known to affect placental gene transcription, are part of the inclusion/exclusion criteria. Researchers should also recognize a caveat of sampling placenta from the first half of pregnancy, is that the pregnancy outcome of an electively terminated pregnancy cannot truly be guaranteed as healthy as the final outcome cannot be determined, thus interpretation of findings involving such samples must take this into account.

Secondly, inadequate sample size may affect statistical power and study reproducibility. Although the average number of placentas profiled in each study is ∼28, this is largely skewed by eight large studies of more than 100 placentas each. The median number of placentas profiled per study is merely 13 (interquartile range 8–29). It is noted that while around one in five studies used fewer than 10 placentas, a considerable number of these smaller studies were performed when the use of profiling technologies were in their infancy and they were valuable in providing an early proof of concept for application in the field. Nevertheless, meta-analysis may be a means to overcome the effects of sample size in some of these earlier studies and small studies of rare conditions. While the choice of study inclusion ultimately rests on the researchers performing the meta-analysis, we strongly recommend caution with including very small studies with fewer than five samples (Supplementary Table SI) as study batch effects are unlikely to be sufficiently corrected for in such cases. Hence, future studies should aim for much larger sample sizes that are adequately powered to answer the study question, to improve reproducibility and verify the findings of past studies going forward.

Sample processing at delivery

Another important factor is the placental sampling procedure at delivery. The region of the placenta to biopsy is dependent on the question asked (Fig. 2). For instance, studies addressing invasion of the extravillous trophoblast into the maternal decidua sample the basal plate (Winn et al., 2009), while those investigating the maternal–foetal transfer across the syncytiotrophoblast would sample the villous placenta (Bari et al., 2016). Unwanted variation may arise from inappropriate sampling of the placenta, such as non-removal of the decidua for studies of the villous placenta, inclusion of infarcted areas and insufficient cleaning to remove excess blood. Another consideration is the importance of multisite sampling of the same region as several studies established intra-placental variation of gene expression (Pidoux et al., 2004; Hughes et al., 2015). The ideal way is to run replicate samples of each placenta, although this may not always be practical given that the cost of genome-wide transcript profiling is still relatively high per sample. An alternative is to pool RNA from multiple sites of the region of interest for each placenta and to have a large enough number of different placentas, so as to ensure differential expression patterns identified are related to the condition studied, rather than normal intra- and inter-individual biological variability.

Figure 2.

Placental regions commonly sampled for transcriptome analyses.

RNA integrity is also vital for proper interpretation of transcriptome data. RNA integrity is determined by measuring the 28S to 18S rRNA ratio or assessing the RNA integrity number (RIN) by a commercially available algorithm. Some placental RNA transcripts are more susceptible to degradation than others due to differences in post-transcriptional regulation (Reiman et al., 2017). Rapidly degrading transcripts are enriched among those encoding membrane components or proteins with transporter function, while stable transcripts are primarily those involved in intracellular function (Reiman et al., 2017). A major determinant of RNA integrity is the time taken to fully immerse in RNAlater or snap-freeze placental biopsies following delivery, which shows an inverse correlation with RIN values (Fajardy et al., 2009; Jobarteh et al., 2014). Biopsies are often rinsed in ice-cold buffer to remove maternal blood contamination prior to RNA preservation, but this step may also alter the transcript profile, particularly at the villous sprouts, which are transcriptionally sensitive to mechanical disturbances (Burton et al., 2014). Storage length prior to RNA extraction may affect the RIN value as well, depending on preservation methods used (Martin et al., 2017). Flash-frozen samples appear more sensitive to RNA degradation over a long period of storage, compared with RNAlater-preserved samples (Fajardy et al., 2009; Martin et al., 2017). Therefore, RNAlater-preservation is preferential for better placental RNA quality as compared to snap-freezing in liquid nitrogen (Wolfe et al., 2014; Pisarska et al., 2016). However, if the sample is limited and there are plans to utilize the tissue for other types of analysis, a potential drawback is that preservation in RNAlater, which has a high salt content and denatures proteins, may interfere with future analysis of native proteins and other techniques. Therefore, researchers should ideally work as efficiently as possible with RNase-free equipment and consumables while handling the placenta, although it is ultimately up to the researcher how they wish to process and store their placental samples.

Transcript profiling and data analysis methods

Following sample collection, various RNA isolation and possibly enrichment methods may be required, depending on which RNA species (e.g. long non-coding RNA or mRNA) are being studied. After RNA isolation, the choice of profiling platform and data analysis is another consideration. While either microarray or RNA sequencing can be used to determine genome-wide transcriptomes, as mentioned earlier, they each have their advantages and disadvantages (thoroughly reviewed by Cox et al., 2015). Data analysis considerations include whether to identify differentially expressed genes or broad categories of dysregulated pathways in case–control studies and to ensure adequate statistical adjustment to account for multiple testing, i.e. false discovery correction. Technical notes and methods to visualize these data are further discussed in a recent review by Konwar et al. (2019).

Data validation

Another key aspect is to validate the findings from transcriptome analyses. Expression changes should ideally be confirmed at the RNA and protein levels by techniques, such as real-time qPCR, immunoblotting, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays and immunohistochemistry. Furthermore, in vitro functional assays with primary explant cultures or isolated cells and in vivo animal models would provide deeper mechanistic insights into the role of identified genes.

Transcriptome studies of healthy placental development

Studies assessing healthy placentas (Table I) have three general aims: to investigate transcriptome changes across gestation, to characterize cell populations within the placenta or to determine the regulation and variability of gene expression across individual placentas.

Gestation-specific effects

Transcriptome datasets exist for each trimester of pregnancy, allowing identification of gestation-specific signatures (Table I: Gestation effects). Two microarray datasets contain placental expression profiles across all trimesters and serve as useful references of the temporal changes that occur during development (Mikheev et al., 2008; Soncin et al., 2018). Unsurprisingly, a common finding of first-trimester studies is an enrichment of highly expressed genes involved in cell proliferation and cell-cycle regulation (Mikheev et al., 2008; Sitras et al., 2012; Lim et al., 2017b; Soncin et al., 2018), which reflects rapid placental growth in early gestation. Interrogation of a large third-trimester microarray dataset of 157 placentas in conjunction with detailed histological analyses enabled markers of normal villous maturation to be identified, which was used to establish a method to calculate the molecular age in weeks of a given placenta, enabling a maturation measure to be assigned to placentas from pathological pregnancies (Leavey et al., 2017). However, the overall number of just under 300 placentas represented by these datasets is still relatively small, particularly for the first and second trimesters with data from only 73 and 21 placentas respectively, and expanding the number of samples profiled will enable elimination of spurious findings and further refinement of gestation-specific transcriptome signatures of placental development.

Cellular characterization and differentiation

The placenta comprises many different cell types. To improve resolution of gene expression to the cellular level, multiple studies have performed global profiling of isolated cells or primary cell cultures from the maternal–foetal interface (Table I: Cellular characterization and differentiation). However, an important caveat is that in addition to varying cell purity of the derived sample, differences may arise in the cellular response to the isolation and/or culture methods, which could become a source of bias and lead to data artefacts that are indistinguishable from naturally occurring in vivo differences. Moreover, aside from one study, datasets in this theme are derived from studies with fewer than 13 individual placentas each, with the majority having five or fewer. This is understandable, given the technical complexities and high time investment involved in isolating and culturing placental cells. However, such a limitation may lead to conclusions that may not fully reflect the natural diversity between individual placentas. Nonetheless, they can still serve as valuable baseline references for future studies in this area.

Trophoblast cells are unique to the placenta and therefore a major cell type specifically targeted for genome-wide transcript profiling. Cytotrophoblast cells are precursors of the extravillous trophoblast and syncytiotrophoblast. Extravillous trophoblast cells are responsible for maternal tissue invasion and placentation, while syncytiotrophoblast forms the maternal–foetal exchange barrier and acts as a major source of endocrine and paracrine factors for supporting pregnancy. However, common trophoblast isolation methods disrupt the multi-nucleated synctiotrophoblast layer, resulting in most studies focussing on just the cytotrophoblast and extravillous trophoblast cells. Extrapolation of their results to the understanding of syncytiotrophoblast function must, therefore, be made with extreme caution. Furthermore, one key finding is that cultured term placental trophoblast cells, as well as endothelial cells, have sex-specific expression patterns, with the male placental transcriptome enriched for pathways involved in the immune system and inflammatory response, which may partly explain the general observation of poorer outcomes for pregnancies with a male foetus (Cvitic et al., 2013). Hence, future studies should consider having a large enough sample size to stratify analyses by sex or be able to account for the possible influence of sex on the cell-specific gene expression profiles.

Recent studies have used single-cell RNA sequencing with microfluidics to characterize gene expression profiles of a variety of individual cells at the maternal–foetal interface. Although the first single-cell study only sequenced 87 cells from just two-term placentas (Pavlicev et al., 2017), it provided an important proof of concept for successfully applying this technology to interrogate the placental transcriptome. Additionally, given the limitation of microfluidics in isolating large cells, the authors utilized laser microdissection to facilitate more accurate profiling of the large multi-nucleated syncytiotrophoblast (Pavlicev et al., 2017), in sharp contrast to subsequent studies that merely dissociated placental tissues and then reported cellular characterization of the syncytiotrophoblast. Although one of these studies acknowledged the shortcomings of the cellular dissociation approach that undoubtedly alters transcript profiles, and the possible under-representation of synctiotrophoblast profiling in the data (Suryawanshi et al., 2018), this consideration was neglected and ignored by the rest (Tsang et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2018; Vento-Tormo et al., 2018). Hence, the current available data are likely biased and not fully reflective of syncytiotrophoblast gene expression across gestation, and should be viewed and used with some caution. Given the important role the syncytiotrophoblast serves as the active cellular and regulatory barrier between mother and foetus, future studies should strive to better profile the synctiotrophoblast, and ensure isolation methods are carefully justified and weaknesses accounted for to allow proper interpretation of findings.

Another methodological factor to consider is the additional mechanical stress following tissue dissociation imposed by either a pre-enrichment of cells by magnetic bead separation (Liu et al., 2018) or pre-sorting of cells by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (Vento-Tormo et al., 2018), which may potentially modify the observed gene expression patterns. A first-trimester study without prior pre-selection did, however, demonstrate a good correlation (Pearson r value of 0.86) of the multi-cell transcriptome of an average villi assessed by single-cell RNA sequencing with that assessed by bulk tissue RNA sequencing, suggesting that overall, tissue dissociation and subsequent microfluidics techniques have only minor effects on the gene expression profiles for most dissociated cells (Suryawanshi et al., 2018). Thus, these latter single-cell sequencing studies can be considered to have collectively established for the first time, at the single-cell level, cell-specific gene expression profiles of the maternal–foetal interface throughout gestation, which serve as a potential reference to deconvolute placental cellular heterogeneity in future bulk tissue studies.

Gene expression variation and regulation

Another purpose of analysing the healthy placental transcriptome is to discover how gene expression is regulated and its variability across different regions of each placenta and between individuals (Table I: Gene expression variation and regulation). One study of third-trimester placentas estimated that while more than half of term placental gene variation was due to differences between individuals, a significant third of variation was attributable to intra-individual differences, compared with only <10% of variation due to ethnic background (Hughes et al., 2015). Foetal-placental sex is a major contributor to inter-individual variation, with sexual dimorphism predominantly arising from differential expression of genes on the sex chromosomes (Gonzalez et al., 2018). Some of the observed differences between individuals and between tissue biopsies of the same placenta likely also arise from cellular heterogeneity, as evidenced by a single-cell sequencing study showing different cellular proportions between individual samples biopsied from within the same placental region and from sample replicates obtained from the same placenta (Tsang et al., 2017). Furthermore, multi-regional sampling of the placenta and associated tissues, such as the decidua and umbilical cord, highlights distinct gene expression patterns associated with each sampling region (Sood et al., 2006; Kim et al., 2012). All of these underscore the importance of sampling region selection (Fig. 2) and having a sufficiently large sample size with multi-site sampling of the same region within each placenta to overcome variations, due to sample collection and intra-individual and inter-individual placental differences, to produce robust datasets reflective of the true ‘experimental’ group differences in question.

Additionally, there are clusters of genes that demonstrate relatively consistent placental expression between individuals and throughout pregnancy regardless of gestation, while others are trimester-specific and even show conserved expression patterns between humans and mice (Buckberry et al., 2017). These consistently expressed genes are likely key regulatory genes indispensable for normal overall placental function and for directing temporal-specific changes relating to the particular requisite functions of the placenta at each trimester.

Attempts to discover what underlies placental gene transcriptional regulation have explored genotype and methylation, which are DNA-based, in association with the transcriptome. Indeed, two large RNA sequencing studies comprising a total of 239 individual placentas with genotype data showed a consistent overlap of 381 expression quantitative trait loci (eQTLs), suggesting that the placental expression of genes in these loci are under stringent genetic control (Peng et al., 2017; Delahaye et al., 2018). Methylation is also associated with variation in placental gene expression. Dual profiling of the third-trimester placental transcriptome and methylome showed that DNA methylation accounted for a greater variance of birthweight than gene expression profiles at a single timepoint, and identified MSX1 and GRB10 methylation as potential master regulators in the transcriptional control of growth-related genes in the term placenta (Turan et al., 2012). Hence, these studies highlight the complexities of placental gene expression regulation which may drive the large variation of expression observed between and within individual placentas and subsequent birth outcomes.

Placental transcriptome studies of pregnancy complications

Improved understanding of the pathophysiology of pregnancy complications is a main driver for interrogating the placental transcriptome (Table II). Studies in this research theme have compared placentas from the normal and pathological states and are discussed taking into account the considerations of study design mentioned above.

Pre-eclampsia

Pre-eclampsia, a serious hypertensive disorder of pregnancy, is the most common pathology in which the placenta has been profiled, with 40 datasets produced from a total of 1192 placentas (44% affected). These datasets represent approximately a fifth of all placental transcriptome datasets (Table II:Pre-eclampsia). Given the nature of pre-eclampsia, difficulty in prediction of its onset and challenges with sampling placenta from ongoing pregnancies, most of the placentas profiled were collected in the third trimester at delivery, during the advanced stages of the disorder. Nevertheless, there is a single study of 12 samples collected from controls and women who subsequently developed pre-eclampsia (Founds et al., 2009). This study utilized surplus tissue obtained from first-trimester chorionic villus sampling and demonstrated placental dysregulation of genes involved in immune modulation, inflammation and cell motility months before the clinical manifestation of pre-eclampsia (Founds et al., 2009), highlighting the early development of this insidious disease in the placenta. This dataset, while small, serves as a rare reference of the early placenta with known outcomes at delivery.

Expression profiling studies at the pre-eclamptic maternal–foetal interface frequently and consistently reveal dysregulated expression of genes involved in the oxidative stress and inflammatory pathways (Eide et al., 2008; Loset et al., 2011; Tsai et al., 2011; Song et al., 2013; Yong et al., 2015; Tong et al., 2018). Moreover, abnormal gene expression signatures of extravillous trophoblast cells, which was identified by the first single-cell RNA sequencing study of pre-eclamptic placenta, were also detectable in the maternal circulation in pre-eclampsia and may potentially serve as a non-invasive marker or ‘liquid biopsy’ of anomalous placental function in the future (Tsang et al., 2017). Collectively, these studies highlight how pre-eclampsia affects multiple molecular pathways and functions of cells of both maternal and foetal origin at the placental interface, thereby underscoring the complexity of disease pathophysiology and the potential to develop some of these differentially expressed genes as biomarkers of pre-eclampsia.

Attempts have been made to delineate pre-eclampsia from other complications, such as gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) and macrosomia (Sitras et al., 2009a; Mayor-Lynn et al., 2011; Nishizawa et al., 2011; Guo et al., 2013; Sober et al., 2015; Lekva et al., 2016; Gibbs et al., 2019). Results of these studies are consistent with the notion that pre-eclampsia is heterogeneous, comprising of multiple molecular subtypes that distinctly cluster with other pregnancy pathologies (Guo et al., 2013; Gibbs et al., 2019), suggestive of a shared aetiology or pathophysiology involving the placenta (Nishizawa et al., 2011; Sober et al., 2015).