Abstract

Background: The genus Stachys L. (Lamiaceae) includes about 300 species as annual or perennial herbs or small shrubs, spread in temperate regions of Mediterranean, Asia, America and southern Africa. Several species of this genus are extensively used in various traditional medicines. They are consumed as herbal preparations for the treatment of stress, skin inflammations, gastrointestinal disorders, asthma and genital tumors. Previous studies have investigated the chemical constituents and the biological activities of these species. Thus, the present review compiles literature data on ethnomedicine, phytochemistry, pharmacological activities, clinical studies and the toxicity of genus Stachys. Methods: Comprehensive research of previously published literature was performed for studies on the traditional uses, bioactive compounds and pharmacological properties of the genus Stachys, using databases with different key search words. Results: This survey documented 60 Stachys species and 10 subspecies for their phytochemical profiles, including 254 chemical compounds and reported 19 species and 4 subspecies for their pharmacological properties. Furthermore, 25 species and 6 subspecies were found for their traditional uses. Conclusions: The present review highlights that Stachys spp. consist an important source of bioactive phytochemicals and exemplifies the uncharted territory of this genus for new research studies.

Keywords: Stachys L., traditional uses, pharmacological activities, phytochemicals, bioactive compounds

1. Introduction

The genus Stachys L., a large member of the Lamiaceae family, comprises more than 300 species, dispersing in temperate and tropical regions of Mediterranean, Asia, America and southern Africa [1,2,3]. Up to now, the most established and comprehensive classification of the genus is introduced by Bhattacharjee (1980), categorizing into two subgenera Betonica L. and Stachys L. [2,3]. The subgenus Stachys includes 19 sections, while the subgenus Betonica comprises 2 sections [1]. However, the two subgenera present important botanical and phytochemical differences which differentiate them [1,4,5].

Stachys species grow as annual or perennial herbs or small shrubs with simple petiolate or sessile leaves. The number of verticillate ranges from four to many-flowered, usually forming a terminal spike-like inflorescence. Calyx tubes are tubular-campanulate, 5 or 10 veined, regular or weakly bilabiate with five subequal teeth. Corolla has a narrow tube, 2-lipped; upper lip flat or hooded and generally hairy, while the lower lip is 3-lopped and glabrous to hairy. The nutlets are oblong to ovoid, rounded at apex [6].

The genus name derived from the Greek word «stachys (=στάχυς) », referring to the type of the inflorescence which is characterized as “spike of corn” and resembles to the inflorescences of the species of genus Triticum L. (Gramineae). In ancient times, the name “stachys” referred mainly to the species Stachys germanica L. whose inflorescence is like an ear and is covered with off-white trichome [7]. The Latin name of the genus is trifarium (=tomentose) [8].

Historically, Dioscorides mentioned the species S. germanica L. with the name “stachys” [9]. However, in late Byzantine era, ‘Nikolaos Myrepsos’ included some species of the genus Stachys (S. germanica L., S. officinalis (L.) Travis, S. alopecuros (L.) Benth.) in his medical manuscript “Dynameron”. Precisely, S. officinalis and S. alopecuros were probably included in 11 recipes, under the names vetoniki, drosiovotanon, lauriole, kakambri, while S. germanica was added in 1 recipe referred as stachys [10].

Many species of the genus are extensively used in traditional medicine of several countries, having various names. For instance, the species S. recta, known as yellow woundwort, is called as “erba della paura” (=“herb that keeps away fear”) in Italy, attributing to the anxiolytic properties of its herbal tea, while S. lavandulifolia Vahl is called as “Chaaye Koohi” in Iran [11,12,13]. In addition, herbal preparations of Stachys spp. are widely consumed in folk medicine to treat a broad array of disorders and diseases, including stress, skin inflammations, stomach disorders and genital tumors [3,14,15]. Specially, the herbal teas of these plants, known as “mountain tea”, are used for skin and stomach disorders [12,16]. The latter common name could lead to a misinterpretation since the herbal remedies of any Sideritis species are globally known with the same name.

In the international literature, Stachys species have been broadly studied through several phytochemical and pharmacological investigations, justifying their ethnopharmacological uses. Of special pharmacological interest are considered the anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, analgesic, renoprotective, anxiolytic and antidepressant activity [3,17,18,19]. The range of the therapeutic properties attributed to these species have been associated to their phytochemical content. Therefore, genus Stachys has received much attention for the screening of its bioactive secondary metabolites from different plant parts. In general, more than 200 compounds have been isolated from this genus, belonging to the following important chemical groups; terpenes (e.g., triterpenes, diterpenes, iridoids), polyphenols (e.g., flavone derivatives, phenylethanoid glycosides, lignans), phenolic acids and essential oils [3,5,14,20,21,22].

Consequently, plants of genus Stachys are considered a great source of phytochemicals with therapeutic and economic applications. Given the increasing demand for natural products, many Stachys species have been cultivated for uses in traditional medicine, in food market, in cosmetic industry and for ornamental reasons [21,22]. Despite the widely uses of the specific species and the large amount of research studies, there has been no recent comprehensive review including all the latest data of the specific genus and its contribution in medicine. Up to now, the available reviews are centered to the phytochemical profile and biological activities of Stachys spp. in correlation to chemotaxonomy approach [3,21,22,23]. Thus, this review summarizes the current state of knowledge on the traditional uses, phytochemistry, pharmacological activities, clinical studies and toxicity of the genus Stachys L.

2. Materials and Methods

A comprehensive search on previous studies was conducted on scientific databases such as PubMed, Scopus, Google scholar and Reaxys, including the years 1969–2020. The search terms “Stachys”, “Stachys compounds”, “Stachys phytochemicals”, “Stachys pharmacological” and “Stachys traditional uses” were used for data collection. Searches were performed for other potential studies by manual screening references in the identified studies. In total, 161 publications describing the traditional uses, bioactive compounds, pharmacological properties and the toxicity of the genus Stachys were included, excluding articles focuses on taxonomy, botany and agronomy. The traditional medicinal uses of Stachys species were reported in Table 1, while the isolated specialized products were categorized by species in Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5, Table 6, Table 7, Table 8, Table 9, Table 10, Table 11, Table 12, Table 13, Table 14 and Table 15, with the attempt of the discrimination between publications describing metabolites′ isolation (including NMR data) or identification/screening (by means of HPLC, LC-MS, etc.). The chemical structures of the bioactive compounds were showed in Table 16, Table 17, Table 18, Table 19, Table 20, Table 21, Table 22, Table 23, Table 24, Table 25, Table 26, Table 27, Table 28 and Table 29. The reported biological activities of extracts/compounds of the last five years were mentioned by Stachys species in Table 30. The general characteristics of the analyzed studies in the current review are showed in Table 31. According to recent publications which support the division of the genus Stachys based on Bhattacharjee (1980), the classification in the present review is formed on this latter study. The species name and their synonyms are quoted as reporting in databases “Plant list” or “Euro + Med” or “IPNI” [24,25,26].

Table 1.

Stachys species with reported traditional medicinal uses.

| Species | Geographical Origin of the Reported Traditional Use | Traditional Medicinal Use | Preparation and/or Administration/ Parts of the Plant |

Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. acerosa Boiss. | Iran | Common cold | Decoction | [31] |

| S. affinis Bunge (=S. sieboldii Miq.) | China | Infections, colds, heart diseases, tuberculosis, pneumonia |

Edible food (tubers) | [27,28] |

| China | Common cold, heart diseases, for pain relief, as antioxidant, to treat ischemic brain injury, dementia, various gastrointestinal related diseases | - | [29] | |

| S. annua (L.) L | Italy | Headache | Infusion of leaves; also, external use to wash face | [51] |

| S. annua (L.) L subsp. annua | Italy | Anti-catarrhal, febrifuge, tonic, vulnerary, against evil eye | Aerial parts | [52] |

| S. arvensis (L.) L. | - | Against evil eye | - | [55] |

| S. balansae Boiss. & Kotschy | - | Hypotonic diseases, cardiac neuroses | Liquid and alcoholic extracts | [23] |

| S. byzantina K. Koch. | - | Anti-inflammatory, antitumor, anticancer, antispasmodic, sedative and diuretic agent, and in the treatment of digestive disorders, wounds, infections, asthma, rheumatic and inflammatory disorders, dysentery, epilepsy, common cold and neuropathy |

- | [33] |

| Iran | Infected wounds, cutting | Decoction, Demulcent (Leaves) |

[34,35] | |

| Brazil | Antiinflammatory | Infusion of leaves | [60] | |

| S. cretica subsp. anatolica Rech. f. | Turkey | Colds, stomach ailments | Infusion, decoction, internal | [49] |

| S. cretica L. subsp. mersinaea (Boiss.) Rech. f. | Turkey | Colds, stomach ailments | Infusion, decoction, internal | [49] |

| S. fruticulosa M. Bieb. | Iran | Anti- inflammatory | Aerial parts | [32] |

| S. geobombycis C.Y.Wu | China, Japan and Europe | Tonic | - | [22] |

| S. germanica L. | Iran | Gastrodynia, for painful menstruation | Infusion of flowers | [34] |

| - | Skin disorders (Veterinary use) | - | [55] | |

| S. glutinosa L. | - | As antispasmoic and against chicken louse | - | [55] |

| S. iberica subsp. georgica Rech. f. | Turkey | Colds, antipyretic | Decoction, internal | [49] |

| S. iberica subsp. stenostachya (Boiss.) Rech. f. | Turkey | Colds, antipyretic, stomach ache | Decoction, internal | [49] |

| S. inflata Benth. | Iran | Infections, asthmatic, rheumatic, inflammatory disorders | Extracts of aerial parts (non flowering stems) | [36,37] |

| Iran | Common cold, Analgesic, high blood pressure |

Decoction of aerial parts | [31] | |

| S. iva Griseb. | Greece | Common cold and gastrointestinal disorders | Decoction, infusion | [56] |

| S. kurdica Boiss & Hohen var. kurdica | Turkey | Cold, stomach-ache | Decoction of branches/flowers Drink one glass of the plant on an empty stomach in the morning |

[50] |

| S. lavandulifolia Vahl. | Iran | Treat pain and inflammation | Boiled extracts of the aerial parts | [12] |

| Iran | Sedative, gastrotonic and spasmolytic properties, treatment of some gastrointestinal disorders, colds and flu | Herbal tea of flowering aerial parts | [13] | |

| Iran | Headache, renal calculus common cold, sedative flavoring agent, abdominal pain |

Decoction of aerial parts, Food additive (aerial parts) |

[31] | |

| Turkey | Antipyretic, cough | Decoction, internal | [49] | |

| Iran | Painful and inflammatory disorders | Boiled extracts of aerial parts | [41] | |

| Iran | Anxiolytic influence | Herbal tea | [38,39,40,41,42,43,44] | |

| S. mucronata Sieb. | Greece | Antirheumatic and antineuralgic remedy | Decoction for massage | [57] |

| For wounds and ulcers | Washed with the decoction and covered with a poultice of fresh leaves for cicatrization | |||

| Antidiarrhoic agent | Infusion of fresh leaves | |||

| Pugative | Infusion of roots | |||

| S. obliqua Waldst. & Kit. | Turkey | Cold, stomach ailments, fever and cough | Herb, infusion, decoction | [22] |

| S. officinalis (L.) Trevisan (=S. betonica Benth.; Betonica officinalis L.) | Serbia, Egypt, Montenegro | Skin disorders, antibacterial purposes, against headache, nervous tension, anxiety, menopausal problems, as a tobacco snuff | Tea of dried leaves | [22] |

| Italy | Dye wool yellow | Plant | [51] | |

| Italy | Wounds, in the sores of pack animals |

Oily extract of flowers | [54] | |

| S. palustris L. | - | Disinfectant, anti-spasmodic and for treatment of wounds | - | [17,61] |

| Poland | Wounds, additive in food | - | [58] | |

| - | Antiseptic, to relieve gout, to stop haemorrhage | - | [62] | |

|

S. parviflora Benth. (=Phlomidoschema parviflorum (Benth.) Vved.) |

- | Cramps, arthralgia, epilepsy, falling sickness, dracunculiasis | - | [63,64] |

| S. pilifera Benth. | Iran | Toothache, edible, tonic, analgesic, edema, expectorant, tussive |

Decoction of aerial parts | [31] |

| Iran | Asthma, rheumatoid arthritis and infections | - | [45] | |

| S. pumila Banks & Sol. | Anatolia | Antibacterial and healing effects | Tea of the whole part | [21] |

| Anatolia | Sedative, antispasmodic, diuretic and emmenagogic properties | Tea of the leaves | [21] | |

| - | Bronchitis, asthma, stomach pain and gall and liver disorders | - | [65] | |

| S. recta L. | Europe | Anxiolytic properties | Herbal tea, Oral administration | [11] |

| Italy | Headache | Infusion of leaves to wash face | [51] | |

| Italy | Bad influence/spirit | Decoction | [53] | |

| Italy | Depurative | Decoction of the aerial parts | [54] | |

| S. recta L. subsp. recta | Italy | Tootache and other pain | Aerial parts applied in body parts | [53] |

| against anxiety, pain and toothache | Decoction of flowering tops for bath or to wash face, hands and wrists for 3 days | |||

| S. schtschegleevii Sosn. ex Grossh. | Iran | Antiinflamatory | Aerial parts | [32,34] |

| Iran | Infectious diseases of the respiratoy tract (for colds and sinusitis), for asthma, rheumatism and other inflammatory disorders | - | [46] | |

| S. sieboldii Miq. (=S. affinis Bunge) | China | Cold and against infections, promoting blood circulation | Dried whole plant | [30] |

| S. sylvatica L. | - | Disinfectant, anti-spasmodic and for treatment of wounds | - | [17] |

| Iran | Diuretic, digestive, emmenagogue, antispasmodic, anti-inflammatory, sedative, tonic properties and for the treatment of women with PCOS | - | [47] | |

| Turkey | Cardiac disorders | Infusion of aerial parts | [48] | |

| S. tibetica Vatke | India | For fever, cough, phobias and various mental disorder |

Whole plant is boiled and made into a decoction. Drink one teacup decoction twice a day to treat fever for 5–7 days | [66] |

| S. turcomanica Trautv. | Iran | Foot inflammation, toothache, bronchitis and common cold |

Infusion, Demulcent, Vapor (Whole plant) |

[34] |

Table 2.

Flavones isolated from Stachys spp.

| Species | Plant Parts | Compound | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subgenus Stachys | |||

| Section Ambleia | |||

| S. aegyptiaca Pers. | Aerial parts | Apigenin (1), Apigenin 7-O-β-D-glucoside (cosmoside) (2), Apigenin 7-O-[6′″-O-acetyl]-allosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucoside (3), Apigenin 6,8-di-C-glucoside (Vicenin-2) (10), Isoscutellarein 7-O-allosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucoside (13), Isoscutellarein-7-O-[6′″-O-acetyl]-β-D-allopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucoside (15), Luteolin (34), Luteolin-7-O-[6′″-O-acetyl]-allosyl]-(1→2)-β-D-glucoside (39), 6,8 Di-C-β-D-glucopyranosyl luteolin (Lucenin-2) (40), Chrysoeriol (42) Chrysoeriol 7-O-β-D-glucoside (43), Hypolaetin 7-O-[6′″-O-acetyl]-allosyl-(1→2)-[3″-O-acetyl]- β-D-glucoside (54), Apigenin 7-O-diglucoside (not determined), Luteolin 7-O-diglucoside (not determined) |

[68] |

| Aerial parts | Apigenin-7-(3″-E-p-coumaroyl)-β-D-glucoside (4), Apigenin 7-(6″-p-coumaroyl)-β-D-glucoside (6) |

[69] | |

| Aerial parts | Isoscutellarein (11), 3′,4′-Dimethyl-luteolin-7-O-β-D-glucoside (41) |

[70] | |

| Isoscutellarein 8-O-(6″-trans-p-coumaroyl)-β-D-glucoside (18) | [71] | ||

| S. inflata Beth. | Scutellarein 7-O-β-D-mannopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucoside (stachyflaside) (31) | [72] | |

| Isoscutellarein (11), 4′-Μethyl-isoscutellarein (12), Scutellarein (29) | [73] | ||

| S. schtschegleevii Sosn. ex Grossh. | Stems | Apigenin 7-O-β-D-glucoside (2), Apigenin 7-(6″-E-p-coumaroyl)-β-D-glucopyranoside (6), 3′-Hydroxy-isoscutellarein-7-O-[6′″-O-acetyl]-β-D-glucopyranoside (14), Chrysoeriol 7-(6″-E-p-coumaroyl)-β-D-glucopyranoside (47) |

[74] |

| Section Campanistrum | |||

| S. arvensis (L.) L. | Aerial parts # | 8-Hydroxyflavone-allosylglucosides (not determined) | [75] |

| S. ocymastrum (L.) Briq. (= S. hirta L.) | Aerial parts # | 8-Hydroxyflavone-allosylglucosides (not determined) | [75] |

| Aerial parts | Apigenin (1), Apigenin 7-(6″-E-p-coumaroyl)-β-D-glucopyranoside (6), Isoscutellarein 7-O-allosyl-(1→2)- glucopyranoside (13), Luteolin (34) |

[76] | |

| Section Candida | |||

| S. candida Bory & Chaubard | Aerial parts | Chrysoeriol (42), Chrysoeriol 7-(3″-E-p-coumaroyl)-β-D-glucopyranoside (46) | [77] |

| Aerial parts | Apigenin 7-O-β-D- glucopyranoside (2), Isoscutellarein 7-O-[6′″-O-acetyl]-β-D-allopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucopyranoside (15), Isoscutellarein 7-O-[6′″-O-acetyl]-allosyl-(1→2)-[6″-O-acetyl]- glucopyranoside (17), 4′-Methyl-isoscutellarein 7-O-β-D-[6′″-O-acetyl]-allopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucopyranoside (21), Chrysoeriol 7-O-β-D- glucopyranoside (43), Chrysoeriol 7-(3″-E-p-coumaroyl)-β-D-glucopyranoside (46), 4′-Methyl-hypolaetin-7-O-[6′″-O-acetyl]-β-D-allopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucopyranoside (56) |

[78] | |

| S. chrysantha Boiss. and Heldr. | Aerial parts | Isoscutellarein 7-O-[6′″-O-acetyl]-allosyl(1→2)-[6″-O-acetyl]-glucoside (17), Luteolin 7-O-β-D-glucoside (37), Chrysoeriol (42), Chrysoeriol 7-O-β-D- glucopyranoside (43), Chrysoeriol 7-(3″-E-p-coumaroyl)-β-D-glucopyranoside (46) | [77] |

| S. iva Griseb. | Flowering aerial parts | Apigenin (1), Isoscutellarein 7-O-[6′″-O-acetyl]-β-D-allopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucopyranoside (15), Isoscutellarein 7-O-[6′″-O-acetyl]-β-D-allopyranosyl-(1→2)-[6″-O-acetyl]-β-D-glucopyranoside (17), 4′-Methyl-isoscutellarein 7-O-β-D-[6′″-O-acetyl]-allopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucopyranoside (21), 4′-Methyl-hypolaetin-7-O-[6′″-O-acetyl]-β-D-allopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucopyranoside (56) |

[56] |

| Section Corsica | |||

| S. corsica Pers. | Isoscutellarein 7-O-[6′″-O-acetyl]-β-D-allopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucopyranoside (15), 4′-Methyl-isoscutellarein 7-O-β-D-[6′″-O-acetyl]-allopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucopyranoside (21) |

[79] | |

| Section Eriostomum | |||

| S. alpina L. | Aerial parts # | 8-Hydroxyflavone-allosylglucosides (not determined) | [75] |

| Leaves # | Hypolaetin 7-O-acetyl-allosyl-(1→2)-glucoside (not determined), Isoscutellarein-7-O-acetyl-allosyl-glucoside (not determined), Hypolaetin-4′-methyl- 7-O- acetyl-allosyl-glucoside (not determined) | [5] | |

| S. byzantina K. Koch. | Aerial parts | Apigenin (1), Apigenin 7-O-β-glucoside (2), Apigenin 7-(6″-E-p-coumaroyl)-β-D-glucopyranoside (6) | [33] |

| Aerial parts | Apigenin 7-(6″-E-p-coumaroyl)-β-D-glucopyranoside (6), Isoscutellarein 7-O-β-D-allopyranosyl-(1→2)-[6″-O-acetyl]-β-D-glucopyranoside (16), 4′-Methyl-isoscutellarein-7-O-β-D-allopyranosyl-(1→2)-[6″-O-acetyl]-β-D-glucopyranoside (20) |

[80] | |

| S. cretica subsp. smyrnaea Rech. f. | Aerial parts # | Apigenin (1) | [81] |

| S. germanica L. | Aerial parts # | Hypolaetin 7-allosyl-(1→2)-glucoside monoacetyl, Isoscutellarein 7-allosyl-(1→2)-glucoside monoacetyl, Hypolaetin 7-allosyl-(1→2)-glucoside diacetyl, Isoscutellarein-7-allosyl-(1→2)-glucoside diacetyl(not determined) | [75] |

| Leaves # | Apigenin 7-O-glucoside (2), Chrysoeriol 7-O-acetyl-allosyl-glucoside (not determined), 4′-Methyl-hypolaetin 7-O-acetyl-allosyl-(1→2)-glucoside (not determined), Apigenin 7-O-p-coumaroyl-glucoside (not determined) | [5] | |

| S. heraclea All. | Aerial parts # | 8-Hydroxyflavone-allosylglucosides (not determined) | [75] |

| S. lanata Crantz. (=S. germanica L. subsp. germanica) | Aerial parts | Apigenin 7-O-β-D-glucopyranoside (2), Apigenin 7-(3″-Z-p-coumaroyl)-β-D-glucopyranoside (5), Apigenin 7-(6″-Z-p-coumaroyl)-β-D-glucopyranoside (7), Apigenin 7-O-(3′′,6′′-di-O-E-p-coumaroyl)-β-D-glucopyranoside (Anisofolin A) (8), Isoscutellarein 7-O-[6′″-O-acetyl]-β-D-allopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucopyranoside (15), Isoscutellarein 4′-methyl ether 7-O-β-D-[6′″-O-acetyl]-allopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucopyranoside (21), 4′-Methyl-hypolaetin-7-O-[6′″-O-acetyl]-β-D-allopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucopyranoside (56) |

[82] |

| S. spectabilis Choisy ex DC. | Epigeal parts | Isostachyflaside (25), Spectabiflaside (28), Scutellarein 7-O-β-D-mannopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucopyranoside (stachyflaside) (31) |

[83] |

| S. thirkei K. Koch. | Whole plant # | Apigenin (1) | [84] |

| S. tmolea Boiss. | Aerial parts # | Apigenin (1), Apigenin-7-O-glucoside (2) | [85] |

| S. tymphaea Hausskn. (=S. germanica subsp. tymphaea (Hausskn.) R. Bhattacharjee) | Flowering aerial parts | Isoscutellarein 7-O-[6′″-O-acetyl]-β-D-allopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucopyranoside (15), 4′-Methyl-isoscutellarein 7-O-β-D-[6′″-O-acetyl]-allopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucopyranoside (21), 4′-Methyl-hypolaetin-7-O-[6′″-O-acetyl]- allopyranosyl -(1→2)-[6″-O-acetyl]-glucopyranoside (58) |

[86] |

| Section Fragilicaulis | |||

| S. subnuda Montbret & Aucher ex Benth | Aerial parts | Ιsoscutellarein 7-O-allosyl-(1→2)-glucoside # (13), Isoscutellarein 7-O-[6″′-O-acetyl]-allosyl-(1→2)-glucoside (15), 4′-Methyl-isoscutellarein-7-O-β-D-allopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucoside # (19), 4′-Methyl-isoscutellarein 7-O-β-D-[6′″-O-acetyl]-allopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucoside (21), 4′-Methyl-isoscutellarein-7-O-[6′″-O-acetyl]-allosyl(1→2)-[6″-O-acetyl]-glucoside # (24) | [87] |

| Section Olisia | |||

| S. atherocalyx C. Koch | Stachyflaside (31) | [72] | |

| Diacetylstachyflaside (not determined), Diacetylspectabiflaside (not determined), Spectabiflaside (28) | [88] | ||

| 5,8,4′-Trihydroxy-3′-methoxy-7-O-(β-D-glucopyranosyl-2″-O-β-D-mannopyranosyl)-flavone (Spectabiflaside) (28), Acetyl-sectabiflaside (not determined), | [89] | ||

| Acetyl-isostachyflaside (26), Di-acetyl-isostachyflaside (27), Spectabiflaside (28) |

[90] | ||

| Leaves # | Isoscutellarein 7-O-[6′″-O-acetyl]-β-D-allopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucopyranoside (15), 4′-Methyl-isoscutellarein-7-O-β-D-[6′″-O-acetyl]-allopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucopyranoside (21), 4′-Methyl-hypolaetin-7-O-[6′″-O-acetyl]-β-D-allopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucopyranoside (56) |

[91] | |

| S. angustifolia M. Bieb. | Isoscutellarein 7-O-[6′″-O-acetyl]-β-D-allopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucopyranoside (15), 4′-Methyl-isoscutellarein 7-O-β-D-[6′″-O-acetyl]-allopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucopyranoside (21) | [92] | |

| S. annua (L.) L. | Epigeal parts | 4′-Methyl-isoscutellarein (12), 7-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl- 5,6-dihydroxy-4′-methoxyflavone (Stachannin A) (32), 4′-Methoxy-scutellarein-7-[O-β-D-mannopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucopyranoside] (Stachannoside B) (33) |

[93] |

| Leaves # | Isoscutellarein 7-O-[6′″-O-acetyl]-β-D-allopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucopyranoside (15), 4′-Methyl-isoscutellarein-7-O-β-D-[6′″-O-acetyl]-allopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucopyranoside (21), 4′-Methyl-hypolaetin-7-O-[6′″-O-acetyl]-β-D-allopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucopyranoside (56) |

[92] | |

| Aerial parts | 4′-Methyl-isoscutellarein 7-O-β-D-[6′″-O-acetyl]-allopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucopyranoside (21) | [94] | |

| Aerial parts | 4′-O-Methyl-isoscutellarein-7-O-[4′″-O-acetyl]allopyranosyl-(1→2)- glucopyranoside (Annuoside) (23) |

[95] | |

| Subterranean organs | 4′-O-Methyl-isoscutellarein (12), 4′-O-Methyl-isoscutellarein 7-O-(6′″-O-acetyl)allopyranosyl-(1→2)-glucopyranoside (21) |

[95] | |

| S.annua (L.) L. subsp. annua | Flowering aerial parts | 4′-Methyl-isoscutellarein 7-O-β-D-[6′″-O-acetyl]-allopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucopyranoside (21), Hypolaetin 7-O-[6′″-O-acetyl]-allosyl-(1→2)-[6″-O-acetyl]-glucopyranoside (53), 4′-Methyl-hypolaetin-7-O-[6′″-O-acetyl]-β-D-allopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucopyranoside (56) |

[52] |

| S. beckeana Dörfler & Hayek | Leaves # | Isoscutellarein 7-O-[6′″-O-acetyl]-β-D-allopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucopyranoside (21), 4′-Methyl-hypolaetin-7-O-[6′″-O acetyl]-β-D-allopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucopyranoside (56) | [92] |

| S. bombycina Boiss. | Aerial parts | Apigenin 7-(6″-E-p-coumaroyl)-β-D-glucopyranoside (6), Stachyspinoside (44) | [96] |

| S. parolinii Vis. | Leaves # | Isoscutellarein 7-O-[6′″-O-acetyl]-β- D-allopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucopyranoside (15), 4′-Methyl-hypolaetin-7-O-[6′″-O-acetyl]-β-D-allopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucopyranoside (56) | [92] |

| S. leucoglossa Griseb. | Leaves # | Isoscutellarein 7-O-[6′″-O-acetyl]-allosyl(1→2)-[6″-O-acetyl]-glucoside (17), 4′-Methyl-isoscutellarein 7-O-β-D-[6′″-O-acetyl]-allopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucopyranoside (21), 4′-Methyl-hypolaetin-7-O-[6′″-O-acetyl]-β-D-allopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucopyranoside (56) | [92] |

| S. neglecta Klok. ex Kossko (=S. annua (L.) L.) | Apigenin (1), Apigenin 7-O-β-D-glucoside (2), Luteolin (34), Luteolin 7-O-β-D-glucoside (37) |

[97] | |

| S. recta L. | Leaves | Isoscutellarein 7-O-[6′″-O-acetyl]-allosyl(1→2)-[6″-O-acetyl]-glucoside (17), 4′-Methyl-isoscutellarein 7-O-β-D-[6′″-O-acetyl]- allosyl](1→2)-β-D-glucoside (21), 4′-Methyl-hypolaetin 7-O-[6′″-O-acetyl]-β-D-allosyl(1→2)-β-D-glucoside (56) | [91,92] |

| Aerial parts | Apigenin 7-(3″-E-p-coumaroyl)-β-D-glucopyranoside (4), Apigenin 7-(6″-E-p-coumaroyl)-β-D-glucopyranoside (6), Isoscutellarein 7-O-[allosyl(1→2)]- glucopyranoside (13), Isoscutellarein 7-O-[6′″-O-acetyl]-β-D-allosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucopyranoside (15), Isoscutellarein 7-O-[6′″-O-acetyl]-allosyl(1→2)-[6″-O-acetyl]- glucopyranoside (17), 4′-Methylisoscutellarein 7- O-[allosyl-(1→2)]- glucopyranoside (19), 4′-Methyl-isoscutellarein 7-O-β-D-[6″-O-acetyl]-allopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucopyranoside (20), 4′-Methyl-isoscutellarein 7-O-β-D-[6′″-O-acetyl]- allosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucopyranoside (21), 4′-Methyl-isoscutellarein 7-O-[6′″-O-acetyl]-allosyl-(1→2)-[6″-O-acetyl]-glucoside (24), Hypolaetin 7-O-allosyl-(1→2)-glucopyranoside # (50), 4′-Methyl-hypolaetin 7-O-allosyl(1→2)-glucoside # (55), 4′-Methyl-hypolaetin-7-O-[6″-O-acetyl]-allosyl-(1→2)- glucopyranoside (57), 4′-Methyl-hypolaetin 7-O-[6′″-O-acetyl]-allosyl-(1→2)-[6″-O-acetyl]- glucopyranoside (58) |

[14] | |

| S. labiosa Bertol. (=S. recta subsp. labiosa (Bertol.) Briq.) | Leaves | Isoscutellarein 7-O-β-D-[6′″-O-acetyl]-allopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucopyranoside (15), 4′-Methyl-isoscutellarein-7-O-β-D-[6′″-O-acetyl]-allopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucopyranoside (21), 4′-Methyl-hypolaetin-7-O-β-D-[6′″-O-acetyl]-allopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucopyranoside (56) | [92] |

| S. subcrenata Vis.(=S. recta L. subsp. subcrenata (Vis.) Briq.) | Leaves | Isoscutellarein 7-O-β-D-[6′″-O-acetyl]-allopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucopyranoside (15), 4′-Methyl-isoscutellarein-7-O-β-D-[6′″-O-acetyl]-allopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucopyranoside (21), 4′-Methyl-hypolaetin-7-O-β-D-[6′″-O-acetyl]-allopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucopyranoside (56) | [92] |

| S. baldaccii (Maly) Hand.—Mazz. (=S. recta L. subsp. baldaccii (K. Maly) Hayek) | Leaves # | Isoscutellarein 7-O-β-D-[6′″-O-acetyl]-allopyranosyl]-(1→2)-β-D-glucopyranoside (15), 4′-Methyl-isoscutellarein-7-O-β-D-[6′″-O-acetyl]-allopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucopyranoside (21) | [92] |

| S. spinosa L. | Aerial parts | Chrysoeriol 7-O-[6′″-O-acetyl-allosyl]-(1→2)-glucoside (Stachyspinoside) (44) | [98] |

| Aerial parts | Chrysoeriol 7-O-[6′′-O-acetyl-allosyl]-(1→2)-glucoside (Isostachyspinoside) (45) | [99] | |

| S. tetragona Boiss. & Hayek | Leaves # | Isoscutellarein 7-O-[6′″-O-acetyl]-β-D-allopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucopyranoside (15), 4′-Methyl-isoscutellarein 7-O-β-D-[6′″-O-acetyl]-allopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucopyranoside (21) | [92] |

| Aerial parts | Isoscutellarein 7-O-[6′″-O-acetyl]-β-D-allopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucopyranoside (15), Isoscutellarein 7-O-[6′″-O-acetyl]- β-D-allosyl-(1→2)-[6″-O-acetyl]-β-D glucopyranoside (17) |

[100] | |

| Section Swainsoniana | |||

| S. anisochila Vis. & Pancic | Leaves | Isoscutellarein 7-O-β-D-allopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucopyranoside (13), Isoscutellarein 7-O-[6′″-O-acetyl]-β-D-allopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucopyranoside (15), Isoscutellarein 7-O-[6′″-O-acetyl]- β-D-allosyl-(1→2)-[6″-O-acetyl]-β-D-glucopyranoside (17), 4′-Methyl-isoscutellarein-7-O-β-D-allopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucopyranoside (19), Hypolaetin 7-O-[6′″-O-acetyl]-β-D-allopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucopyranoside (51), Hypolaetin 7-O-[6′″-O-acetyl]- β-D-allopyranosyl-(1→2)-[6″-O-acetyl]-β-D glucopyranoside (53), 4′-Methyl-hypolaetin-7-O-[6′″-O-acetyl]-β-D-allopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucopyranoside (56), 4′-Methyl-hypolaetin 7-O-[6′″-O-acetyl]-β-D-allosyl-(1→2)-[6″-O-acetyl]-β-D glucopyranoside (58) |

[101] |

| Leaves | Apigenin 7-O-(p-coumaroyl)-β-D-glucopyranoside (not determined) | [5] | |

| S. decumbens Pers. (=S. mollissima Willd.) | Aerial parts # | 8-Hydroxyflavone-allosylglucosides (not determined) | [75] |

| S. menthifolia Vis. (=S. grandiflora Host.) | Leaves # | Isoscutellarein 7-O-β-D-[6′″-O-acetyl]-β-D-allopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucopyranoside (15), 4′-Methyl-isoscutellarein-7-O-β-D-[6′″-O-acetyl]-β-D allopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucopyranoside (21) | [92] |

| S. swainsonii Benth. subsp. swainsonii | Aerial parts | Apigenin (1), Apigenin 7-O-β-D-glucopyranoside (2), Apigenin 7-O-β-D-glucoside (2), Luteolin 7-O-β-D-glucopyranoside (37), Chrysoeriol (42), Chrysoeriol 7-O-β-D-glucopyranoside (43), Stachyspinoside (44) | [102] |

| S. swainsonii subsp. argolica (Boiss.) Phitos and Damboldt | Aerial parts | Apigenin (1), Luteolin 7-O-β-D-glucopyranoside (37), Chrysoeriol (42), Chrysoeriol-7-O-β-D-glucopyranoside (43), Chrysoeriol 7-(3″-E-p-coumaroyl)-β-D-glucopyranoside (46) | [102] |

| S. swainsonii subsp. melangavica D. Persson | Aerial parts | Apigenin (1), Apigenin 7-O-β-D- glucopyranoside (2), Luteolin 7-O-β-D-glucopyranoside (37), Chrysoeriol-7-O-β-D-glucopyranoside (43), Stachyspinoside (44) | [102] |

| S. swainsonii subsp. scyronica (Boiss.) Phitos and Damboldt | Aerial parts | Apigenin (1), Apigenin 7-O-β-D- glucopyranoside (2), Luteolin 7-O-β-D-glucopyranoside (37), Chrysoeriol-7-O-β-D-glucopyranoside (43), Stachyspinoside (44) | [102] |

| S. ionica Halácsy | Aerial parts | Apigenin (1), Apigenin 7-(6″-E-p-coumaroyl)-β-D-glucopyranoside (6), Isoscutellarein 7-O-[6′″-O-acetyl]-β-D-allopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucopyranoside (15), 4′-Methyl-isoscutellarein 7-O-β-D-[6′″-O-acetyl]-β-D-allopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucopyranoside (21) | [20] |

| Section Stachys | |||

| S. sieboldii Miq. (=S. affinis Bunge) | Aerial parts | Isoscutellarein 7-O-[6′″-O-acetyl]-β-D-allosyl]-(1→2)-β-D-glucoside (15), 4′-Methyl-isoscutellarein 7-O-[6′″-O-acetyl]-β-D-allopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucoside (21) | [20] |

| S. mialhesii Noé | Aerial parts | Apigenin 7-(6″-E-p-coumaroyl)-β-D-glucopyranoside (6), Isoscutellarein 7-O-[6′″-O-acetyl]-β-D-allopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucopyranoside (15) | [103] |

| S. palustris L. | 5-(glycuroglucosyl)-7-methoxybaicalein (Palustrin) (63), 5-(glucuronosyl)-7-methoxybaicalein (Palustrinoside) (64) | [104] | |

| Leaves # | Vicenin-2 (10), Apigenin 7-O-p-coumaroyl-β-D-glucopyranoside (not determined) | [5] | |

| S. sylvatica L. | Aerial parts # | 8-Hydroxyflavone-allosyl-glucosides (not determined) | [75] |

| Leaves # | Chrysoeriol 7-O-acetylallosylglucoside (not determined), Apigenin 7-O-p-coumaroyl-β-D-glucopyranoside (not determined) | [5] | |

| S. plumosa Griseb. | Leaves # | Apigenin-7-O-β-D-glucoside (2), Luteolin 7-O-β-D-glucoside (37), Chrysoeriol 7-O-acetyl-allosyl-glucoside (not determined), Isoscutellarein 7-O-acetyl-allosyl-glucoside (not determined), Apigenin 7-O-p-coumaroyl-β-D-glucopyranoside (not determined) | [5] |

| Section Zietenia | |||

| S. lavandulifolia Vahl. | Aerial parts | Apigenin (1), Hydroxygenkwanin (Luteolin 7-Methyl ether) (35), Chrysoeriol (42) | [13] |

| S. tibetica Vatke | Roots | Apigenin 7-O-β-D-glucoside (2) | [66] |

| Subgenus Betonica | |||

| Section Betonica | |||

| S. alopecuros (L.) Benth. | Aerial parts | p-coumaroyl-glucosides (not determined) # | [75] |

| Leaves # | Isoscutellarein 7-O-glucoside (11a), Luteolin 7-O-glucuronide (36), Luteolin 7-O-glucoside (37), Chrysoeriol 7-O-glucoside (43), Hypolaetin 7-O-glucoside (49), Hypolaetin 7-O-glucuronide (49a), Selgin 7-O-glucoside (59), Tricin 7-O-glucuronide (60), Tricin 7-O-glucoside (61), Apigenin 7-O-p-coumaroyl glucopyranoside (not determined) |

[5] | |

| S. foliosa Regel. (=S. betoniciflora Rupr.; Betonica foliosa Rupr.) | Four flavonoids (not determined) | [105] | |

| S. monieri (Gouan) P.W. Ball. (=S. officinalis (L.) Trevis subsp. officinalis) | Aerial parts | p-coumaroyl-glucosides (not determined) # | [75] |

| S. officinalis (L.) Trevis (=Betonica officinalis L.) | Apigenin (1), 5, 6, 4′-trihydroxyflavone-7-O-β-D-glucoside (30) |

[20] | |

| Leaves # | Apigenin 8-C-glucoside (Vitexin) (9), Luteolin 7-O-glucuronide (36), Luteolin 6-C-glucoside (isoorientin) (38), Tricin 7-O-glucuronide (60), Tricin 7-O-glucoside (61), Tricetin 3′,4′,5′-trimethyl-7-O-glucoside (62), Apigenin 7-O-p-coumaroyl glucopyranoside (not determined) |

[5] | |

| Aerial parts | p-coumaroyl-glucosides (not determined) # | [75] | |

| Section Macrostachya | |||

| S. scardica Griseb. (=Betonica scardica Griseb.) | Leaves # | Apigenin 8-C-glucoside (9), Luteolin 7-O-glucoside (37), Luteolin 6-C-glucoside (38), Hypolaetin 7-O-glucoside (49), Selgin 7-O-glucoside (59), Tricin 7-O-glucuronide (60), Tricin 7-O-glucoside (61), Tricetin 3′,4′,5′-trimethyl-7-O-glucoside (isolation) (62), Apigenin 7-O-p-coumaroyl glucopyranoside (not determined) |

[5] |

# identified compounds by means of HPLC, LC-MS, etc.

Table 3.

Poly-methylated flavonoids from Stachys spp.

| Species | Plant Parts | Compound | Ref | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subgenus Stachys | ||||

| Section Ambleia | ||||

| S. aegyptiaca Pers. | Aerial parts | Xanthomicrol (69), Sideritiflavone (70), 5-Hydroxy-6,7,8,3′,4′-pentamethoxyflavone (75), 5,4′-Dihydroxy - 6,7,8,3′-tetramethoxyflavone (76), 5,3′,4′-Trihydroxy-3,6,7,8-tetramethoxyflavone (82), Calycopterin (83), Chrysosplenetin (84), 5-Hydroxy-3,6,7,8,4′- pentamethoxyflavone (88), 5,4′-Dihydroxy -3,6,7,8,3′- pentamethoxyflavone (89) |

[68] | |

| Aerial parts | 5,7,3′-Trihydroxy-6,4′-dimethoxyflavone (67), 5,7,3′-Trihydroxy-6,8,4′-trimethoxyflavone (68) | [70] | ||

| Aerial parts | Xanthomicrol (69), Eupatilin-7-methyl ether (73), Calycopterin (83), 5-Hydroxy-3,6,7,4′-tetramethoxy flavone (85), 5,8-Dihydroxy-3,6,7,4′-tetramethoxy flavone (86), 5-Hydroxy-auranetin (88), 4′-Hydroxy-3,5,7,3′- tetramethoxy flavone (90) | [106] | ||

| S. schtschegleevii Sosn. ex Grossh. | Stems | Cirsimaritin (66), Xanthomicrol (69) | [74] | |

| Section Aucheriana | ||||

| S. glutinosa L. | Xanthomicrol (69), Sideritiflavone (70), 8-Methoxycirsilineol (71), Eupatilin (72a) | [107] | ||

| Section Candida | ||||

| S. candida Bory & Chaubard | Aerial parts | Xanthomicrol (69), Calycopterin (83) | [77,78] | |

| S. chrysantha Boiss. and Heldr. | Aerial parts | Xanthomicrol (69), Calycopterin (83) | [77] | |

| Section Swainsoniana | ||||

| S. swainsonii Benth. subsp. swainsonii | Aerial parts | Eupatorin (72), Penduletin (81), 5-Hydroxyauranetin (88) | [102] | |

| S. swainsonii subsp. argolica (Boiss.) Phitos and Damboldt | Aerial parts | Xanthomicrol (69), Eupatorin (72), Salvigenin (74) |

[102] | |

| S. swainsonii subsp. melangavica D. Persson | Aerial parts | Eupatorin (72), 5-Hydroxyauranetin (88) | [102] | |

| S. swainsonii subsp. scyronica (Boiss.) Phitos and Damboldt | Aerial parts | Eupatorin (72), Penduletin (81), 5-Hydroxyauranetin (88) | [102] | |

| S. ionica Halácsy | Aerial parts | Xanthomicrol (69), Salvigenin (74), Chrysosplenetin (84), 5-Hydroxy-3,6,7,4′-tetramethoxyflavone (85), Casticin (87) | [20] | |

| S. lavandulifolia Vahl. | Aerial parts | Velutin (Luteolin 7,3′-dimethyl ether) (65), Viscosine (5,7,4′-trihydroxy-3,6-dimethoxyflavone (78), Kumatakenin (Kaempferol 3,7-dimethyl ether) (79), Pachypodol (Quercetin 3,7,3′-trimethyl ether) (80), Penduletin (81), Chrysosplenetin (84), | [13] | |

| Subgenus Betonica | ||||

| Section Betonica | ||||

| S. officinalis (L.) Trevis = (Betonica officinalis L.) | 5,4′-Dyhydroxy-7,3′,5′-trimethoxyflavone (77) | [20] | ||

Table 4.

Flavonols from Stachys spp.

| Species | Plant Parts | Compound | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subgenus Stachys | |||

| Section Eriostomum | |||

| S. cretica subsp. smyrnaea Rech. f. | Aerial parts # | Kaempferol (91) | [81] |

| Section Olisia | |||

| S. tetragona Boiss. & Hayek | Aerial parts | Kaempferol (91) | [100] |

| Section Swainsoniana | |||

| S. swainsonii Benth. subsp. swainsonii | Aerial parts | Isorhamnetin (92) | [99] |

| S. swainsonii subsp. argolica (Boiss.) Phitos and Damboldt | Aerial parts | Isorhamnetin (92) | [99] |

| Section Stachys | |||

| S. palustris L. | Leaves # | Quercetin-3-O-rutinoside (93), Isorhamnetin-3-O-rutinoside (94) | [5] |

# identified compounds by means of HPLC, LC-MS, etc.

Table 5.

Flavanones from Stachys spp.

| Species | Plant Parts | Compound | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subgenus Stachys | |||

| Section Ambleia | |||

| S. aegyptiaca Pers. | Aerial parts | Naringenin (96) | [69] |

| Section Eriostomum | |||

| S. cretica subsp. smyrnaea Rech. f. | Aerial parts # | Hesperidin (97) | [81] |

| Section Swainsoniana | |||

| S. swainsonii Benth. subsp. swainsonii | Aerial parts | Eriodictyol (95) | [102] |

| S. swainsonii subsp. argolica (Boiss.) Phitos and Damboldt | Aerial parts | Eriodictyol (95) | [102] |

| S. swainsonii subsp. melangavica D. Persson | Aerial parts | Eriodictyol (95) | [102] |

| S. swainsonii subsp. scyronica (Boiss.) Phitos and Damboldt | Aerial parts | Eriodictyol (95) | [102] |

Table 6.

Biflavonoid from Stachys spp.

| Species | Plant Parts | Compound | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subgenus Stachys | |||

| Section Ambleia | |||

| S. aegyptiaca Pers. | Aerial Parts | Diapigenin-7-O-(6″-trans,6″-cis-p, p′-dihydroxy-µ-truxinyl)glucoside (stachysetin) (98) |

[69] |

| Section Eriostomum | |||

| S. lanata Crantz. (=S. germanica L. subsp. germanica) | Aerial parts | Stachysetin (98) | [82] |

| Section Candida | |||

| S. iva Griseb. | Flowering aerial parts | Stachysetin (98) | [56] |

Table 7.

Phenolic derivatives from Stachys spp.

| Species | Plant Parts | Compound | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subgenus Stachys | |||

| Section Candida | |||

| S. candida Bory & Chaubard | Aerial parts | Chlorogenic acid (103) | [78] |

| S. iva Griseb | Flowering aerial parts | Chlorogenic acid (103) | [56] |

| Section Eriostomum | |||

| S. cretica subsp. smyrnaea Rech. f. | Aerial parts # | Chlorogenic acid (103) | [81] |

| S. cretica subsp. vacillans Rech. f. | Aerial parts # | Vanillic acid (100), Syringic acid (101), Chlorogenic acid (103) | [105] |

| S. cretica subsp. mersinaea (Boiss.) Rech. f. | Aerial parts # | Chlorogenic acid (103) | [108] |

| S. lanata Crantz. (=S. germanica L. subsp. germanica) | Roots | Chlorogenic acid (103) | [82] |

| S. tmolea Boiss | Aerial parts # | 4-Hydroxybenzoic acid (99), Chlorogenic acid (103) | [85] |

| S. thirkei K. Koch | Aerial parts # | Chlorogenic acid (103) | [84] |

| S. germanica L. subsp. salviifolia (Ten.) Gams. | Aerial parts | Arbutin (107) | [109] |

| Section Olisia | |||

| S. atherocalyx C. Koch. | Νeochlorogenic acid (105), p-Coumaric acid (106), Caffeic acid (108) | [110] | |

| S. recta L. | Aerial parts # | 1-Caffeoylquinic acid (102), Chlorogenic acid (103), 4-Caffeoylquinic acid (104) |

[14] |

| Section Stachys | |||

| S. palustris L. | 1-Caffeoylquinic acid (102), Chlorogenic acid (103), 4-Caffeoylquinic acid (104), Caffeic acid (108) | [104] | |

| Cryptochlorogenic acid (104), Neochlorogenic acid (105) | [23] | ||

| Subgenus Betonica | |||

| Section Betonica | |||

| S. officinalis L. (=Betonica officinalis L.) | Leaves # | Chlorogenic acid (103) | [111] |

# identified compounds by means of HPLC, LC-MS, etc.

Table 8.

Acetophenone glycosides from Stachys spp.

| Species | Plant Parts | Compound | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subgenus Stachys | |||

| Section Eriostomum | |||

| S. lanata Crantz. (=S. germanica L. subsp. germanica) | Roots | Androsin (109), Neolloydosin (110), Glucoacetosyringone (111) | [82] |

Table 9.

Lignans from Stachys spp.

Table 10.

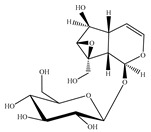

Phenylethanoid glycosides from Stachys spp.

| Species | Plant Parts | Compound | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subgenus Stachys | |||

| Section Ambleia | |||

| S. schtschegleevii Sosn. ex Grossh. | Stems | Acteoside (118), Betunyoside F (128) | [74] |

| Section Candida | |||

| S. candida Bory & Chaubard | Aerial parts | Acteoside (118) | [78] |

| S. iva Griseb. | Flowering aerial parts | Acteoside (118), Leucosceptoside A (131), Lavandulifolioside (129) |

[56] |

| Section Eriostomum | |||

| S. byzantina Κ. Koch | Aerial parts | Verbascoside (118), 2′-O-Arabinosyl verbascoside (122), Aeschynanthoside C (133) | [33] |

| S. cretica L. subsp. vacillans Rech. f. | Aerial parts # | Verbascoside (118) | [112] |

| S. germanica L. subsp. salviifolia (Zen.) Gams | Aerial parts | Verbascoside (118) | [109] |

| S. lanata Crantz (=S. germanica L. subsp. germanica) | Aerial parts | Leonoside B (134), Martynoside (135) | [82] |

| Roots | Rhodioloside (115), Verbasoside (116), Verbascoside (118), Isoacteoside (119), Darendoside B (120), Campneoside II (121), 2-Phenylethyl-D-xylopyranosyl-(1→6)-D-glucopyranoside (117), Campneoside I (136) |

[82] | |

| S. tymphaea Hausskn. (=S. germanica subsp. tymphaea (Hausskn.) R. Bhattacharjee) | Flowering aerial parts | Verbascoside (118), Stachysoside A (129) | [86] |

| Section Olisia | |||

| S. recta L. | Aerial parts | Acteoside (118), Isoacteoside (119), β-OH-Acteoside (121), Betunyoside E (127), Campneoside I (136), Forsythoside B (137), β-OH-Forsythoside B methyl ether (138) |

[14] |

| S. tetragona Boiss. & Heldr. | Aerial parts | Acteoside (118), Betonioside F (128), Leucosceptoside A (131), Stachysoside D (134), Forsythoside B (137), Lamiophloside A (141) |

[100] |

| Section Stachys | |||

| S. affinis Bunge (=S. sieboldii Miq.) | Tubers | Acteoside (118), Leucosceptoside A (131), Martynoside (135) |

[27] |

| Stachysosides A (129), B (139), C (140) | [113] | ||

| S. riederi Cham. | Whole plants | Acteoside (118), Campneoside II (121), Lavandulifolioside (129), Leonoside A (139) | [114] |

| Section Zietenia | |||

| S. lavandulifolia Vahl | Aerial parts | Acteoside (118), Lavandulifolioside (129) |

[115] |

| Aerial parts | Verbascoside (118), Lavandulofolioside A (129), Lavandufolioside B (130), Leucosceptoside A (131) |

[12] | |

| Aerial parts | Acteoside (118) | [116] | |

| Subgenus Betonica | |||

| Section Betonica | |||

| S. macrantha (C. Koch.) Stearn (=Betonica grandiflora Willd.) | Aerial parts | Verbascoside (118), Leucosceptoside A (131), Martynoside (135), Lavandulifolioside (129) |

[117] |

| S. officinalis (L.) Trevis. (=Betonica officinalis L.) | Aerial parts | Acteoside (118), Acteoside isomer (isoacteoside) (119), Campneoside II (121), Betonyosides A-F (123–128), Leucosceptoside B (132), Forsythoside B (137) |

[118] |

| S. alopecuros (L.) Benth subsp. divulsa (Ten.) Grande | Flowering aerial parts | Verbascoside (118) | [119] |

| Former Stachys species | |||

| S. parviflora Benth. (=Phlomidoschema parviflorum (Benth.) Vved.) | Whole plant | Parvifloroside A (142), Parvifloroside B (143) | [120] |

# identified compounds by means of HPLC, LC-MS, etc.

Table 11.

Phenylpropanoid glucosides from Stachys spp.

| Species | Plant Parts | Compound | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subgenus Stachys | |||

| Section Eriostomum | |||

| S. lanata Crantz. (=S. germanica L. subsp. germanica) | Roots | Coniferin (144), Syringin (145) |

[82] |

Table 12.

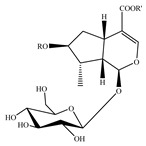

Iridoids from Stachys spp.

| Species | Plant Parts | Compound | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subgenus Stachys | |||

| Section Ambleia | |||

| S. inflata Benth. | Ajugol (146), Ajugoside (147), | [121] | |

| Section Aucheriana | |||

| S. glutinosa L. | Aerial parts | Harpagide (148), Acetylharpagide (150), Monomelittoside (165), Melittoside (166), Allobetonicoside (161), 5-Allosyloxy-aucubin (167) |

[122] |

| Section Campanistrum | |||

| S. ocymastrum (L.) Briq. (=S. hirta L.) | Leaves | 6β-Acetoxyipolamiide (172), 6β-Hydroxyipolamiide (173), Ipolamiide (174), Ipolamiidoside (175), Lamiide (176) | [123] |

| Section Candida | |||

| S. iva Griseb. | Flowering Aerial parts | Harpagide (148), 8-Acetylharpagide (150), 8-Epi-loganic acid (157), Gardoside (160), 8-Epi-loganin (159), Monomelittoside (165), Melittoside (166) |

[56] |

| Section Corsica | |||

| S. corsica Pers. | Harpagide (148), Acetylharpagide (150) |

[79] | |

| Section Eriostomum | |||

| S. alpina L. | Stems, Leaves # | Ajugoside (147), Harpagide (148), Acetylharpagide (150), Harpagoside (154), Aucubin (164), Catalpol (163) |

[124] |

| S. balansae Boiss. & Kotschy | Ajugol (146), Ajugoside (147) | [125] | |

| S. germanica L. | Harpagide (148) | [125] | |

| Leaf, Inflorescence # | Ajugoside (147), Harpagide (148), Acetylharpagide (150), Harpagoside (154), Aucubin (164), Catalpol (163) |

[124] | |

| S. spectabilis Choisy ex DC. | Ajugol (146), Ajugoside (147), Harpagide (148) | [125] | |

| S. byzantina Κ. Koch. | Aerial parts # | Ajugoside (147), Harpagide (148), Acetylharpagide (150), Harpagoside (154), Catalpol (163), Aucubin (164) |

[124] |

| S. germanica L. subsp. salviifolia (Zen.) Gams | Flowering Aerial parts | Harpagide (148) | [86] |

| Aerial parts | Ajugol (146), Harpagide (148), 7-Hydroxyharpagide (149), 5-Allosyloxy-aucubin (167) |

[109] | |

| S. lanata Crantz. (=S. germanica L. subsp. germanica) | Roots | Stachysosides E (168), G (170), H (171) | [82] |

| Aerial parts | Stachysosides E (168), F (169) | [82] | |

| S. tymphaea Hausskn. (=S. germanica subsp. tymphaea (Hausskn.) R. Bhattacharjee) | Aerial parts | Harpagide (148) | [86] |

| Section Olisia | |||

| S. angustifolia M. Bieb. | Ajugoside (147), Acetylharpagide (150), Harpagide (148), Melittoside (166) |

[92] | |

| S. annua (L.) L. | Ajugoside (147), Acetylharpagide (150), Melittoside (166) |

[92] | |

| S. atherocalyx C. Koch. | Ajugol (146), Harpagide (148), Acetylharpagide (150), Melittoside (166) |

[92,125] | |

| S. beckeana Dörfl. & Hayek | Harpagide (148), Ajugol (146), Acetylharpagide (150), Melittoside (166) |

[92] | |

| S. iberica M. Bieb. | Ajugol (146), Ajugoside (147), Harpagide (148), Acetylharpagide (150) | [121] | |

| S. recta L. | Ajugol (146), Harpagide (148), Acetylharpagide (150), Melittoside (166) | [92] | |

| Leaves | 8-Acetylharpagide (150), Melittoside# (166) | [14] | |

| Aerial parts # | Ajugoside (147), Harpagide (148), Acetylharpagide (150), Harpagoside (154), Catalpol (163), Aucubin (164) |

[124] | |

| S. baldaccii (Maly) Hand-Mazz (=S. recta L. subsp. baldaccii (K. Maly) Hayek) | Ajugol (146), Ajugoside (147), Harpagide (148), Acetylharpagide (150), Melittoside (166) | [92] | |

| S. subcrenata Vis. (=S. recta subsp. subcrenata) | Ajugol (146), Harpagide (148), Acetylharpagide (150), Melittoside (166) | [92] | |

| S. labiosa Bertol. | Ajugol (146), Harpagide (148), Acetylharpagide (150), Melittoside (166) | [92] | |

| S. leucoglossa Griseb. | Ajugol (146), Harpagide (148), Acetylharpagide (150), Melittoside (166) | [92] | |

| S. spinosa L. | Aerial parts | Ajugol (146), Harpagide (148), 7-O-Acetyl-8-epi-loganic acid (158) | [98] |

| S. tetragona Boiss. & Heldr. | Ajugol (146), Ajugoside (147), Harpagide (148), Acetylharpagide (150), Melittoside (166) | [92] | |

| Aerial parts | 8-Acetyl-harpagide (150), 5-O-Allopyranosyl-monomelittoside (167) | [100] | |

| Section Stachys | |||

| S. affinis Bunge (= S. sieboldii Miq.) | Tubers | Harpagide (148), Acetylharpagide (150), Melittoside (166), 5-Allosyloxy-aucubin (167) | [27] |

| S. palustris L. | Aerial parts # | Ajugoside (147), Harpagide (148), Acetylharpagide (150), Harpagoside (154), Catalpol (163), Aucubin (164) |

[124] |

| S. sylvatica L. | Aerial parts # | Ajugoside (147), Harpagide (148), Acetylharpagide (150), Harpagoside (154), Catalpol (163), Aucubin (164) |

[124] |

| Section Swainsoniana | |||

| S. anisochila Vis. & Pancic | Acetylharpagide (150), Melittoside (166) |

[92] | |

| S. ionica Halácsy | 8-epi-loganic acid (157), Gardoside (160) |

[20] | |

| S. menthifolia Vis. (= S. grandiflora Host.) | Ajugol (146), Harpagide (148), Acetylharpagide (150), Melittoside (166) |

[92] | |

| Aerial parts # | Ajugoside (147) Harpagide (148), Acetylharpagide (150), Harpagoside (154), Catalpol (163), Aucubin (164) |

[124] | |

| Section Zietenia | |||

| S. lavandulifolia Vahl. | Ajugol (146), Ajugoside (147) | [125] | |

| Aerial parts | Melittoside (166), Monomelittoside (165), 5-O-Allopyranosyl-monomelittoside (167) | [12] | |

| Subgenus Betonica | |||

| Section Betonica | |||

| S. alopecuros (L.) Benth subsp. divulsa (Ten.) Grande | Flowering aerial parts | Harpagide (148), Acetylharpagide (150), 4′-O-β-D-galactopyranosyl-teuhircoside (162) |

[119] |

| S. foliosa Rupr. (=S. betoniciflora Rupr.; Betonica foliosa Rupr.) | Harpagide (148), Acetylharpagide (150) | [126] | |

| S. betonicaeflora Rupr. | Harpagide (148), Acetylharpagide (150) | [126] | |

| S. macrantha (C. Koch.) Stearn (=Betonica grandiflora Steph. ex Willd.) | Aerial parts | Ajugol (146), Ajugoside (147), Harpagide (148), 8-O-Acetyl-harpagide (150), Reptoside (153), Macranthoside [=8-O- (3, 4-dimethoxy-cinnamoyl-harpagide)] (156), Allobetonicoside (161) |

[117] |

| S. officinalis (L.) Trevis. (=Betonica officinalis L.) | Aerial parts | Acetylharpagide (150), Reptoside (153), 6-O-Acetylmioporoside (155), Allobetonicoside (161) |

[127] |

| Harpagide (148), Acetylharpagide (150) | [128] | ||

| Aerial parts # | Ajugoside (147), Harpagide (148), Acetylharpagide (150), Harpagoside (154), Catalpol (163), Aucubin (164) |

[124] | |

| Unknown Section | |||

| S. grandidentata Lindl. ** | Aerial parts | Ajugol (146), Harpagide (148), Acetylharpagide (150), 5-Desoxy-harpagide (151), 5-Desoxy-8-acetyl-harpagide (152), Monomelittoside (165), Melittoside (166) |

[129] |

# identified compounds#identified compounds by means of HPLC, LC-MS, etc; ** endemic species of Chile.

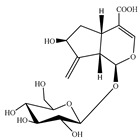

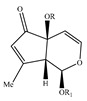

Table 13.

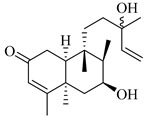

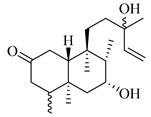

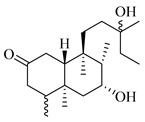

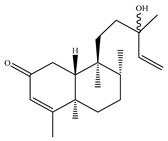

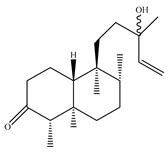

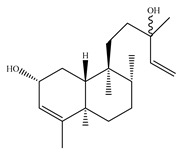

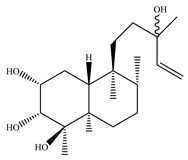

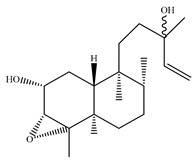

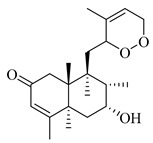

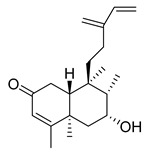

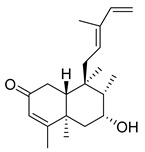

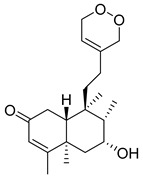

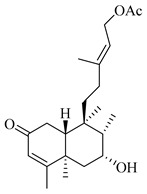

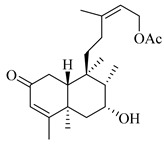

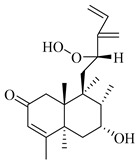

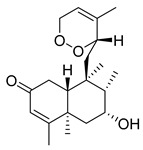

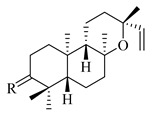

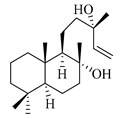

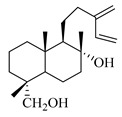

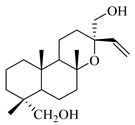

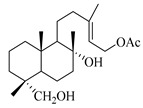

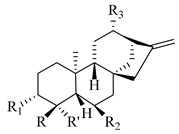

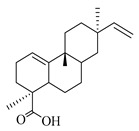

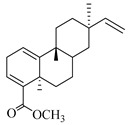

Diterpenes from Stachys spp.

| Species | Plant Parts | Compound | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subgenus Stachys | |||

| section Ambleia | |||

| S. aegyptiaca Pers. | Stachysolone (177), 11a,18-Dihydroxy-ent-kaur-16-ene (210) | [130] | |

| Aerial parts | Stachysperoxide (189), Stachysolone (177), 7,13-Diacetyl-stachysolone (180) | [131] | |

| Aerial parts | Stachaegyptin A-C (190–192), Roseostachenone (184), Stachysolone (177), 7,13-Diacetyl-stachysolone (180) |

[106] | |

| Aerial parts | Stachaegyptins D, E (193, 194) | [132] | |

| Aerial parts | Stachaegyptins A (190), F-H (195–197), Stachysperoxide (189) | [133] | |

| S. inflata Benth. | Annuanone (181), Stachylone (182), Stachone (183) | [134] | |

| Section Aucheriana | |||

| S. glutinosa L. | Aerial parts | Roseostachenone (184), 3α,4α-Epoxyroseostachenol (188) | [107] |

| Section Eriostomum | |||

| S. balansae Boiss. & Kotschy | Annuanone (181), Stachylone (182) | [134] | |

| S. lanata Crantz. (=S. germanica L. subsp. germanica) |

Ent-3α-acetoxy-kaur-16-en-19-oic acid (207), Ent-3α,19-dihydroxy-kaur-16-ene (208), Ent-3α-hydroxy-kaur-16-en-19-oic acid (209) |

[135] | |

| Section Mucronata | |||

| S. mucronata Sieb. | Aerial parts | Ribenone [=3β-hydroxy-13-epi-ent-manoyl oxide] (198), Ribenol [=3-keto-13-epi-ent-manoyl oxide] (199) | [57] |

| Section Olisia | |||

| S. annua (L.) L. | Stachysolone (177) | [136,137] | |

| Annuanone (181), Stachylone (182), Stachone (183) | [138] | ||

| S. atherocalyx C. Koch. | Annuanone (181), Stachylone (182), Stachone (183) |

[134] | |

| S. distans Benth | Aerial parts | (+)-6-Deoxyandalusol (201) | [139] |

| S. iberica M. Bieb. | Annuanone (181), Stachylone (182), Stachone (183) |

[134] | |

| S. recta L. | Aerial parts | 7,13-Diacetate stachysolone (180), 7-Acetate stachysolone (178), 13-Acetate stachysolone (179) | [140] |

| Section Roseostachys | |||

| S. rosea Boiss. | Aerial parts | Roseostachenone (184), Roseostachone (185), 13-epi-sclareol (200), Roseostachenol (186), Roseotetrol (187) | [141] |

| Section Stachys | |||

| S. mialhesii Noé | Aerial parts | Horminone (211) | [103] |

| S. palustris L. | Annuanone (181) | [134] | |

| S. sylvatica L. | Stachysic acid (204) | [142] | |

| Annuanone (181), Stachylone (182), Stachone (183) |

[134] | ||

| Stachysic acid (204), 6β-Hydroxy-ent-kaur-16-ene (205), 6β,18-Dihydroxy-ent-kaur-16-ene (206) |

[142] | ||

| Betolide (214) | [143] | ||

| Section Swainsoniana | |||

| S. ionica Halácsy | Aerial parts | (+)-6-Deoxyandalusol (201) | [139] |

| S. plumosa Griseb. | Aerial parts | (+)-6-Deoxyandalusol (201), 13-Epi-jabugodiol (202), (+)-Plumosol (203) |

[144] |

| Section Zietenia | |||

| S. lavandulifolia Vahl. | Aerial parts | Stachysolone (177) | [116] |

| Subgenus Betonica | |||

| Section Betonica | |||

| S. officinalis (L.) Trevis. (=Betonica officinalis L.) | Betolide (214) | [145] | |

| Betonicolide (215), Betonicosides A-D (216–219) |

[145] | ||

| Roots | Betolide (214) | [143] | |

| S. scardica (Griseb.) Hayek (=Betonica scardica Griseb.) | Roots | Betolide (214) | [143] |

| Former Stachys species | |||

| S. parviflora Benth. (=Phlomidoschema parviflorum (Benth.) Vved.) | Whole plant | Stachyrosane 1 (212) Stachyrosane 2 (213) |

[133] |

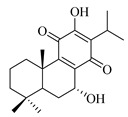

Table 14.

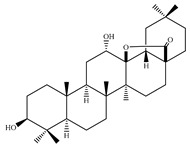

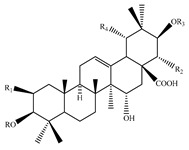

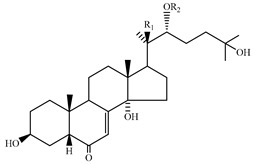

Triterpene derivatives, Phytosterols and Phytoecdysteroids from Stachys spp.

| Species | Plant Parts | Compound | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subgenus Stachys | |||

| Section Eriostomum | |||

| S. byzantina K. Koch | Aerial parts | Stigmasterol (220), | [17] |

| β-Sitosterol (221), Lawsaritol (223), Stigmastan-3,5-dien-7-one (224) |

[35] | ||

| S. hissarica Regel | - | 20-Hydroxyecdysone (239), Polipodin B (240), Integristeron A (241), 2-Desoxy-20-hydroxyecdysone (242), 2-Desoxyecdyson (243) | [67] |

| Section Olisia | |||

| S. annua (L.) L. | Aerial parts | β-Sitosterol (221), Ursolic acid (226) | [95] |

| S. spinosa L. | Aerial parts | Stigmasterol (220), β-Sitosterol (221), Oleanolic acid (227), 12α-Hydroxy-oleanolic lactone (228) |

[99] |

| S. tetragona Boiss. & Heldr. | Aerial parts | Stigmasterol (220), β-Sitosterol (221), Oleanolic acid (227), |

[100] |

| Section Stachys | |||

| S. palustris L. | β-Sitosterol (221), α-amyrin (225) |

[146] | |

| S. riederi Cham. | Whole plant | Stachyssaponins I-VIII (231–238) | [147] |

| Subgenus Betonica | |||

| Section Betonica | |||

| S. alopecuros (L.) Benth subsp. divulsa (Ten.) Grande | Flowering aerial parts | 3-O-β-Sitosterol-glucoside (222) | [119] |

| Former Stachys species | |||

| S. parviflora Benth. (=Phlomidoschema parviflorum (Benth.) Vved.) | Aerial parts | Stachyssaponin A (229), Stachyssaponin B (230) |

[63] |

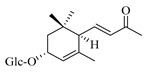

Table 15.

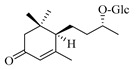

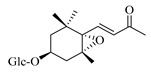

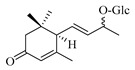

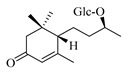

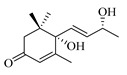

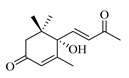

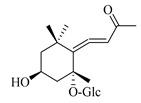

Megastigmane derivatives from Stachys spp.

| Species | Plant Parts | Compound | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subgenus Stachys | |||

| Section Eriostomum | |||

| S. byzantina K. Koch. | Aerial parts | Byzantionoside A (244), Byzantionoside B (245), Icariside B2 (246), (6R, 9R)- and (6R, 9S)-3-oxo-α-ionol glucosides (247), Blumeol C glucoside (248) |

[148] |

| S. lanata Crantz (=S. germanica L. subsp. germanica) | Aerial parts | Vomifoliol (249), Dehydrovomifoliol (250) | [82] |

| Roots | Citroside A (251) | [82] | |

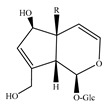

Table 16.

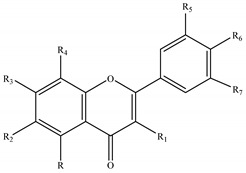

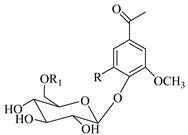

Chemical structures of flavones isolated from Stachys spp.

| Name | R1 | R2 | R3 | R4 | R5 | R6 | R7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R=OH | |||||||

| Apigenin (1) | H | H | OH | H | H | OH | H |

| Apigenin 7-O-β-D-glucoside (cosmoside) (2) | H | H | O-glc | H | H | OH | H |

| Apigenin 7-O-[6′″-O-acetyl]-β-D-allosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucoside (3) | H | H | O-[6′″-acetyl-allosyl]-(1→2)-glc | H | H | OH | H |

| Apigenin 7-(3″-E-p-coumaroyl)-β-D-glucoside (4) | H | H | O-(3″-E-p-coumaroyl)-glc | H | H | OH | H |

| Apigenin 7-(3″-Z-p-coumaroyl)-β-D-glucoside (5) | H | H | O-(3″-Z-p-coumaroyl)-glc | H | H | OH | H |

| Apigenin 7-(6″-E-p-coumaroyl)-β-D-glucoside (6) | H | H | O-(6″-E-p-coumaroyl)-glc | H | H | OH | H |

| Apigenin 7-(6″-Z-p-coumaroyl)-β-D-glucoside (7) | H | H | O-(6″-Z-p-coumaroyl)-glc | H | H | OH | H |

| Apigenin 7-(3″,6″-p-dicoumaroyl)- β-D-glucoside (Anisofolin A) (8) | H | H | O-(3″,6″-p-dicoumaroyl)-glc | H | H | OH | H |

| Apigenin 8-C-glucoside (9) | H | H | OH | C-glc | H | OH | H |

| Apigenin 6,8-di-C-glucoside (Vicenin-2) (10) | H | C-glc | OH | C-glc | H | OH | H |

| Isoscutellarein (11) | H | H | OH | OH | H | OH | H |

| Isoscutellarein 7-O-glucoside (11a) | H | H | O-glc | OH | H | OH | H |

| 4′-Methyl-isoscutellarein (12) | H | H | OH | OH | H | OCH3 | H |

| Isoscutellarein 7-O-allosyl-(1→2)-glucoside (13) | H | H | O-allosyl-(1→2)- glc | OH | H | OH | H |

| 3′-Hydroxy-isoscutellarein-7-O-[6′″-O-acetyl]-β-D-glucoside (14) | H | H | O-[6′″-O-acetyl]- glc | OH | OH | OH | H |

| Isoscutellarein 7-O-[6′″-O-acetyl]-β-D-allosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucoside (15) | H | H | O-[6′″-O-acetyl]-allosyl-(1→2)-glc | OH | H | OH | H |

| Isoscutellarein 7-O-β-D-allosyl-(1→2)-[6″-O-acetyl]-β-D-glucoside (16) | H | H | O-[6″-O-acetyl]-allosyl-(1→2)-glc | OH | H | OH | H |

| Isoscutellarein 7-O-[6′″-O-acetyl]-β-D-allosyl-(1→2)-[6″-O-acetyl]- β-D-glucoside (17) | H | H | O-[6′″-O-acetyl]-allosyl-(1→2)-[6″-O-acetyl]-glc | OH | H | OH | H |

| Isoscutellarein 8-O-(6″-trans-p-coumaroyl)-β-D-glucoside (18) | H | H | OH | O-(6”-trans-p-coumaroyl)-glc | H | OH | H |

| 4′-Methyl-isoscutellarein 7-O-β-D-allosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucoside (19) | H | H | O-allosyl-(1→2)-glc | OH | H | OCH3 | H |

| 4′-Methyl- isoscutellarein 7-O-β-D-allosyl-(1→2)-[6″-O-acetyl]-β-D-glucoside (20) | H | H | O-allosyl-(1→2)-[6″-O-acetyl]-glc | OH | H | OCH3 | H |

| 4′-Methyl-isoscutellarein 7-O-β-D-[6′″-O-acetyl]-allosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucoside (21) | H | H | O-[6′″-O-acetyl]-allosyl-(1→2)-glc | OH | H | OCH3 | H |

| 4′-Methyl-isoscutellarein 7-O- [2″-O-acetyl]-β-D-allosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucoside (22) | H | H | O-[2″-O-acetyl]-allosyl-(1→2)-glc | OH | H | OCH3 | H |

| 4′-Methyl-isoscutellarein 7-O-β-D-[4′′′-O-acetyl]-allosyl]-(1→2)-β-D-glucoside (annuoside) (23) | H | H | O-[4′′′-O-acetyl]-allosyl-(1→2)-glc | OH | H | OCH3 | H |

| 4′-Methyl-isoscutellarein 7-O-[6′′′-O-acetyl]-allosyl-(1→2)-[6″-O-acetyl]-glucoside (24) | H | H | O-[6′′′-O-acetyl]-allosyl-(1→2)-[6″-O-acetyl]-glc | OH | H | OCH3 | H |

| Isostachyflaside (25) | H | H | OH | OH | H | O-mannosyl- (1→2)-glc | H |

| Acetyl-isostachyflaside (26) | H | H | OH | OH | H | O-[acetyl]-mannosyl- (1→2)-glc | H |

| Di-acetyl- isostachyflaside (27) | H | H | OH | OH | H | O-[diacetyl-mannosyl]- (1→2)-glc | H |

| Spectabiflaside (28) | H | H | O-mannosyl- (1→2)-glc | OH | OCH3 | OH | H |

| Scutellarein (29) | H | OH | OH | H | H | OH | H |

| Scutellarein 7-O-β-D-glucoside[5,6, 4′-trihydroxyflavone-7-O-β-D-glucoside] (30) | H | OH | O-glc | H | H | OH | H |

| Scutellarein 7-O-β-D-mannnosyl- (1→2)-β-D-glucoside (stachyflaside) (31) | H | OH | O-mannosyl- (1→2)-glc | H | H | OH | H |

| 7-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl-5,6-dihydroxy-4′-methoxyflavone (Stachannin A) (32) | H | OH | O-glc | H | H | OCH3 | H |

| 4′-Methoxy-scutellarein 7-[O-β-D-mannosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucoside (Stachannoside B) (33) | H | OH | O-mannosyl- (1→2)-glc | H | H | OCH3 | H |

| Luteolin (34) | H | H | OH | H | OH | OH | H |

| Luteolin 7-methyl ether (35) | H | H | OCH3 | H | OH | OH | H |

| Luteolin 7-O-β-D-glucuronide (36) | H | H | O-glcA | H | OH | OH | H |

| Luteolin 7-O-β-D-glucoside (37) | H | H | O-glc | H | OH | OH | H |

| Luteolin 6-C-glucoside (isoorientin) (38) | H | -C-glc | OH | H | OH | OH | H |

| Luteolin 7-O-[6′′′-O-acetyl]-allosyl-(1→2)-glucoside (39) | H | H | O-[6′′′-O-acetyl]-allosyl-(1→2)-glc | H | OH | OH | H |

| 6,8 Di-C-β-D-glucopyranosyl luteolin (Lucenin-2) (40) | H | C-glc | OH | C-glc | OH | OH | H |

| 3′,4′-Dimethyl-luteolin-7-O-β-D-glucoside (41) | H | H | O-glc | H | OCH3 | OCH3 | H |

| Chrysoeriol (42) | H | H | OH | H | OCH3 | OH | H |

| Chrysoeriol 7-O-β-D-glucoside (43) | H | H | O-glc | H | OCH3 | OH | H |

| Chrysoeriol 7-O-[6′′′-O-acetyl]-β-D-allosyl-(1→2)-glucoside (Stachyspinoside) (44) | H | H | O-[6′′′-O-acetyl]- allosyl-(1→2)-glc | H | OCH3 | OH | H |

| Chrysoeriol 7-O-[6″-O-acetyl]-β-D-allosyl-(1→2)-glucoside (Isostachyspinoside) (45) | H | H | O-[6″-O-acetyl]- allosyl-(1→2)-glc | H | OCH3 | OH | H |

| Chrysoeriol 7-(3″-E-p-coumaroyl)-β-D-glucoside (46) | H | H | O-(3″-E-p-coumaroyl)-glc | H | OCH3 | OH | H |

| Chrysoeriol 7-(6″-E-p-coumaroyl)-β-D-glucoside (47) | H | H | O-(6″-E-p-coumaroyl)-glc | H | OCH3 | OH | H |

| Hypolaetin (48) | H | H | OH | OH | OH | OH | H |

| Hypolaetin-7-O-glucoside (49) | H | H | O-glc | OH | OH | OH | H |

| Hypolaetin-7-O-glucuronide (49a) | H | H | O-glcA | OH | OH | OH | H |

| Hypolaetin 7-O-allosyl-(1→2)-glucoside (50) | H | H | O-allosyl-(1→2)-glc | OH | OH | OH | H |

| Hypolaetin 7-O-[6′′′-O-acetyl]-β-D-allosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucoside (51) | H | H | O-[6′′′-O-acetyl]- allosyl-(1→2)- glc | OH | OH | OH | H |

| Hypolaetin 7-O-[6″-O-acetyl]-allosyl-(1→2)glucoside (52) | H | H | O-[6″-O-acetyl]- allossyl-(1→2)- glc | OH | OH | OH | H |

| Hypolaetin 7-O-[6′′′-O-acetyl]-allosyl-(1→2)-[6″-O-acetyl]-glucoside (53) | H | H | O-[6′′′-O-acetyl]-allosyl-(1→2)-[6″-O-acetyl]- glc | OH | OH | OH | H |

| Hypolaetin 7-O-[6′′′-O-acetyl]-allosyl-(1→2)-[3″-O-acetyl]-glucoside (54) | H | H | O-[6′′′-O-acetyl]-allosyl-(1→2)-[3″-O-acetyl]- glc | OH | OH | OH | H |

| 4′-Methyl-hypolaetin-7-O-allosyl-(1→2)-glucoside (55) | H | H | O-allosyl-(1→2)-glc | OH | OH | OCH3 | H |

| 4′-Methyl-hypolaetin-7-O-[6′′′-O-acetyl]-β-D-allopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucopyranoside (56) | H | H | O-[6′′′-O-acetyl]-allosyl-(1→2)- glc | OH | OH | OCH3 | H |

| 4′-Methyl-hypolaetin-7-O-[6″-O-acetyl]-β-D-allopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucopyranoside (57) | H | H | O-[6″-O-acetyl]-allosyl-(1→2)- glc | OH | OH | OCH3 | H |

| 4′-Methyl-hypolaetin-7-O-[6′′′-O-acetyl]-allosyl-(1→2)-[6″-O-acetyl]-glucoside (58) | H | H | O-[6′′′-O-acetyl]-allosyl-(1→2)-[6″-O-acetyl]- glc | OH | OH | OCH3 | H |

| Selgin 7-O-glucoside (59) | H | H | O-glc | H | OCH3 | OH | OH |

| Tricin 7-O-glucuronide (60) | H | H | O-glcA | H | OCH3 | OH | OCH3 |

| Tricin 7-O-glucoside (61) | H | H | O-glc | H | OCH3 | OH | OCH3 |

| Tricetin 3′,4′,5′-trimethyl-7-O-glucoside (62) | H | H | O-glc | H | OCH3 | OCH3 | OCH3 |

| R= O-glcA-glc (2 → 1) | |||||||

| Palustrin (63) | H | OH | OCH3 | H | H | H | H |

| R= O-glcA | |||||||

| Palustrinoside (64) | H | OH | OCH3 | H | H | H | H |

glc: glucose, glcA: glucuronide.

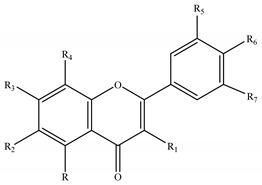

Table 17.

Chemical structures of poly-methylated flavonoids from Stachys spp.

| Name | R1 | R2 | R3 | R4 | R5 | R6 | R7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R=OH | |||||||

| Velutin (luteolin 7,3′-dimethyl ether) (65) | H | H | OCH3 | H | OCH3 | OH | H |

| Cirsimaritin (66) | H | OCH3 | OCH3 | H | H | OH | H |

| 5,7,3′-Trihydroxy-6,4′-dimethoxyflavone (67) | H | OCH3 | OH | H | OH | OCH3 | H |

| 5,7,3′-Trihydroxy-6,8,4′-trimethoxyflavone (68) | H | OCH3 | OH | OCH3 | OH | OCH3 | H |

| Xanthomicrol (69) | H | OCH3 | OCH3 | OCH3 | H | OH | H |

| Sideritiflavone (70) | H | OCH3 | OCH3 | OCH3 | OH | OH | H |

| 8-Methoxycirsilineol (71) | H | OCH3 | OCH3 | OCH3 | OCH3 | OH | H |

| Eupatorin (72) | H | OCH3 | OCH3 | H | OH | OCH3 | H |

| Eupatilin (72a) | H | OCH3 | OH | H | OCH3 | OCH3 | H |

| Eupatilin-7-methyl ether (73) | H | OCH3 | OCH3 | H | OCH3 | OCH3 | H |

| Salvigenin (74) | H | OCH3 | OCH3 | H | H | OCH3 | H |

| 5-Hydroxy-6,7,8,3′,4′-pentamethoxyflavone (75) | H | OCH3 | OCH3 | OCH3 | OCH3 | OCH3 | H |

| 5, 4′-Dihydroxy - 6,7,8,3′-tetramethoxyflavone (76) | H | OCH3 | OCH3 | OCH3 | OCH3 | OH | H |

| 5, 4′-Dihydroxy-7,3′,5′-trimethoxyflavone (77) | H | H | OCH3 | H | OCH3 | OH | OCH3 |

| Viscosine (5,7,4′-trihydroxy-3,6-dimethoxyflavone) (78) | OCH3 | OCH3 | OH | H | H | OH | H |

| Kumatakenin (kaempferol 3,7-dimethyl ether) (79) | OCH3 | H | OCH3 | H | H | OH | H |

| Pachypodol (quercetin 3,7,3′-trimethyl ether) (80) | OCH3 | H | OCH3 | H | OCH3 | OH | H |

| Penduletin (81) | OCH3 | OCH3 | OCH3 | H | H | OH | H |

| 5,3′,4′-Trihydroxy-3,6,7,8-tetramethoxyflavone (82) | OCH3 | OCH3 | OCH3 | OCH3 | OH | OH | H |

| Calycopterin (83) | OCH3 | OCH3 | OCH3 | OCH3 | H | OH | H |

| Chrysosplenetin (84) | OCH3 | OCH3 | OCH3 | H | OCH3 | OH | H |

| 5-Hydroxy-3,6,7,4′-tetramethoxyflavone (85) | OCH3 | OCH3 | OCH3 | H | H | OCH3 | H |

| 5,8-Dihydroxy-3,6,7,4′-tetramethoxyflavone (86) | OCH3 | OCH3 | OCH3 | OH | H | OCH3 | H |

| Casticin (87) | OCH3 | OCH3 | OCH3 | H | OH | OCH3 | H |

| 5-Hydroxy-3,6,7,8,4′- pentamethoxyflavone (5-hydroxyauranetin) (88) |

OCH3 | OCH3 | OCH3 | OCH3 | H | OCH3 | H |

| 5,4′-Dihydroxy -3,6,7,8,3′- pentamethoxyflavone (89) | OCH3 | OCH3 | OCH3 | OCH3 | OCH3 | OH | H |

| R=OCH3 | |||||||

| 4′-Hydroxy- 3,5,7,3′-tetramethoxyflavone (90) | OCH3 | H | OCH3 | H | OCH3 | OH | H |

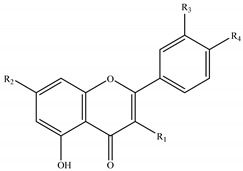

Table 18.

Chemical structures of flavonols from Stachys spp.

| Name | R1 | R2 | R3 | R4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kaempferol (91) | OH | OH | H | OH |

| Isorhamnetin (92) | OH | OH | OCH3 | OH |

| Quercetin 3-O-rutinoside (93) | O-rut | OH | OH | OH |

| Isorhamnetin 3-O-rutinoside (94) | O-rut | OH | OCH3 | OH |

rut: rutinoside.

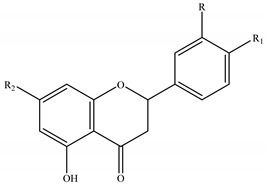

Table 19.

Chemical structures of flavanones from Stachys spp.

| Name | R | R1 | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eriodictyol (95) | OH | OH | OH |

| Naringenin (96) | H | OH | OH |

| Hesperidin (97) | OH | OCH3 | O-rut |

rut: rutinoside.

Table 20.

Chemical structure of biflavonoid from Stachys spp.

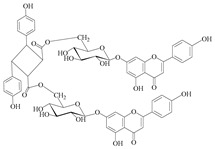

| Stachysetin (98) |

|---|

|

Table 21.

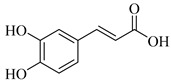

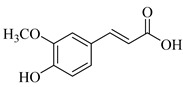

Chemical structures of phenolic derivatives from Stachys spp.

|

4-Hydroxybenzoic acid R=H, R1=H, R2=H (99) | |

| Vanillic acid R=H, R1=H, R2=OCH3 (100) | ||

| Syringic acid R=H, R1= OCH3, R2=OCH3 (101) | ||

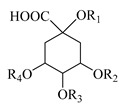

|

1-Caffeoylquinic acid R1=caffeoyl-, R2=R3=R4=H (102) | |

| 3-Caffeoylquinic acid (Chlorogenic acid) R1=H, R2=caffeoyl-, R3=R4=H (103) | ||

| 4-Caffeoylquinic acid (cryptochlorogenic acid) R1=R2=H, R3=caffeoyl-, R4=H (104) | ||

| 5-Caffeoylquinic acid (neohlorogenic acid) R1=R2=R3=H, R4=caffeoyl- (105) | ||

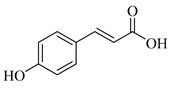

p-Coumaric acid (106) |

Arbutin (107) |

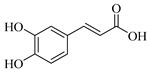

Caffeic acid (108) |

Glc: glucose.

Table 22.

Chemical structures of acetophenone glycosides from Stachys spp.

|

|---|

| Androsin R=R1=H (109) |

| Neolloydosin R=H, R1=Xyl (110) |

| Glucoacetosyringone R=OCH3, R1=H (111) |

Xyl: xylose.

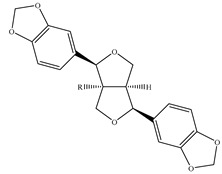

Table 23.

Chemical structures of lignans from Stachys spp.

|

|

|---|---|

| Sesamin R=H (112) Paulownin R=OH (113) |

(7S-8R)-Urolignoside (114) |

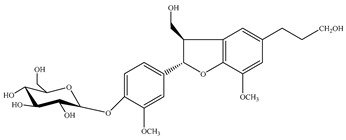

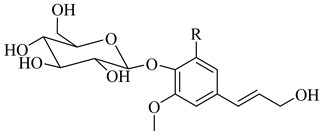

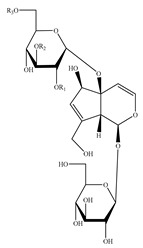

Table 24.

Chemical structures of phenylethanoid glycosides from Stachys spp.

Caffeic acid Caffeic acid |

Ferulic acid Ferulic acid |

||||||

| Name | R1 | R2 | R3 | R4 | R5 | R6 | R |

| Rhodioloside (Salidroside) (115) | H | H | H | H | H | OH | H |

| Verbasoside (decaffeoyl-acteoside) (116) | H | H | Rha | H | OH | OH | H |

| 2-Phenylethyl-D-xylopyranosyl-(1→6)-D-glucopyranoside (117) | Xyl | H | H | H | H | H | H |

| Acteoside (Verbascoside) (118) | H | Caf | Rha | H | OH | OH | H |

| Isoacteoside (119) | Caf | H | Rha | H | OH | OH | H |

| Darendoside B (deacyl-martynoside) (120) | H | H | Rha | H | OH | OCH3 | H |

| β-OH-Acteoside (Campneoside II) (121) | H | Caf | Rha | OH | OH | OH | H |

| 2′-O-Arabinosyl verbascoside (122) | H | Caf | Rha | H | OH | OH | Ara |

| Betonyoside A (123) | H | Fer | Rha | OH | OH | OH | H |

| Betonyoside B/C (isomers) (124/125) | Fer | H | Rha | OH | OH | OH | H |

| Betonyoside D (126) | Api | Cis-fer | Rha | H | OH | OCH3 | H |

| Betonyoside E (127) | Api | Fer | Rha | OH | OH | OH | H |

| Betonyoside F (128) | H | Caf | Rha-Api | H | OH | OH | H |

| Lavandulifolioside A (Stachysoside A) (129) | H | Caf | Rha-Ara | H | OH | OH | H |

| Lavandulifolioside B (130) | H | 4′-methyl-Fer | Rha-Ara | H | OCH3 | OH | H |

| Leucosceptoside A (131) | H | Fer | Rha | H | OH | OH | H |

| Leucosceptoside B (132) | Api | Fer | Rha | H | OH | OCH3 | H |

| Aeschynanthoside C (133) | H | Fer | Xyl | H | OH | OCH3 | H |

| Leonoside B (Stachysoside D) (134) | H | Fer | Rha-Ara | H | OH | OCH3 | H |

| Martynoside (135) | H | Fer | Rha | H | OH | OCH3 | H |

| Campneoside I (136) | H | Caf | Rha | OCH3 | OH | OH | H |

| Forsythoside B (137) | Api | Caf | Rha | H | OH | OH | H |

| β-OH-Forsythoside B methyl ether (138) | Api | Caf | Rha | OCH3 | OH | OH | H |

| Leonoside A (Stachysoside B) (139) | H | Fer | Rha-Ara | H | OH | OH | H |

| * Stachysoside C (140) | H | Fer | Rha-Ara | H | OH | OH | H |

| Lamiophloside A (141) | Api | Fer | Rha | H | OCH3 | OH | H |

| Parvifloroside A (142) | H | Caf | H | H | OH | OH | Rha |

| Parvifloroside B (143) | Caf | H | H | H | OH | OH | Rha |

Caf: Caffeic acid, Fer: Ferulic acid, Api: Apioside, Rha: Rhamnoside, Ara: Arabinoside, Xyl: Xyloside, *: might be synonym of Leonoside B.

Table 25.

Chemical structures of phenylpropanoid glucosides from Stachys spp.

| |

|---|---|

| Coniferin R=H (144) | Syringin R=OCH3 (145) |

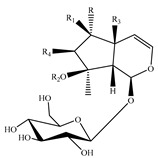

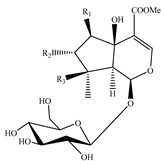

Table 26.

Chemical structures of iridoids from Stachys spp.

| Name | R | R1 | R2 | R3 | R4 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ajugol (146) | H | OH | H | H | H | |||

| Ajugoside (147) | H | OH | Ac | H | H | |||

| Harpagide (148) | H | OH | H | OH | H | |||

| 7-Hydroxyharpagide (149) | H | OH | H | OH | OH | |||

| 8-Acetylharpagide (Acetylharpagide) (150) | H | OH | Ac | OH | H | |||

| 5-Desoxyharpagide (151) | OH | OH | H | H | H | |||

| 5-Desoxy-8-acetylharpagide (152) | OH | OH | Ac | H | H | |||

| Reptoside (153) | H | H | Ac | OH | H | |||

| Harpagoside (154) | H | OH | Cinnamoyl- | OH | H | |||

| 6-O-Acetylmioporoside (155) | AcO | H | H | H | H | |||

| Macranthoside (156) | H | OH | 3,4-dimethoxy cinnamoyl- | OH | H | |||

|

8-Epi-loganic acid R=R′=H (157) | |||||||

| 7-O-Acetyl-8-epi-loganic acid R=Ac, R′=H (158) | ||||||||

| 8-Epi-loganin R=H, R′=CH3 (159) | ||||||||

|

Gardoside (160) | |||||||

|

Allobetonicoside R=Allose, R1=Glc (161) | |||||||

| 4′-O-β-D-galactopyranosyl-teuhircoside R=H, R1=Glc-Gal (162) | ||||||||

|

Catalpol (163) | |||||||

|

Aucubin R=H (164) | |||||||

| Monomelittoside R=OH (165) | ||||||||

| Melittoside R=O-Glc (166) | ||||||||

| 5-O-Allopyranosyl-monomelittoside; 5-Allosyloxy-aucubin R=O-Alo (167) | ||||||||

|

Name | R1 | R2 | R3 | ||||

| Stachysoside E (168) | H | p-(E)-coumaroyl- | H | |||||

| Stachysoside F (169) | H | p-(Z)-coumaroyl- | H | |||||

| Stachysoside G (170) | H | H | p-(E)-coumaroyl- | |||||

| Stachysoside H (171) | p-(E)-coumaroyl- | H | H | |||||

|

Name | R1 | R2 | R3 | ||||

| 6β-Acetoxyipolamiide (172) | OAc | H | OH | |||||

| 6β-Hydroxyipolamiide (173) | OH | H | OH | |||||

| Ipolamiide (174) | H | H | OH | |||||

| Ipolamiidoside (175) | H | H | OAc | |||||

Glc: Glucose, Gal: Galactose, Alo: Allose.

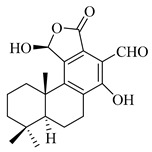

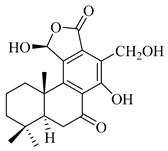

Table 27.

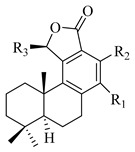

Diterpenes from Stachys spp.

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | R1 | R2 | |||

| Stachysolone (177) | H | H | |||

| 7-Monoacetyl-stachysolone (178) | Ac | H | |||

| 13-Monoacetyl-stachysolone (179) | H | Ac | |||

| 7,13-Diacetyl-stachysolone (180) | Ac | Ac | |||

|

|

|

|||

| Annuanone (181) | Stachylone (182) | Stachone (183) | |||

|

|

|

|||

| Roseostachenone (184) | Roseostachone (185) | Roseostachenol (186) | |||

|

|

||||

| Roseotetrol (187) | 3α,4α-Epoxyroseostachenol (188) | ||||

| |||||

| Stachysperoxide (189) | |||||

|

|

||||

| Stachaegyptin A (190) | Stachaegyptin B (191) | ||||

|

|

||||

| Stachaegyptin C (192) | Stachaegyptin D (193) | ||||

|

|

||||

| Stachaegyptin E (194) | Stachaegyptin F (195) | ||||

|

|

||||

| Stachaegyptin G (196) | Stachaegyptin H (197) | ||||

|

|

||||

| Ribenone R=O (198) Ribenol R=αOH,βH(199) |

13-Epi-sclareol (200) | ||||

|

|

||||

| (+)-6-Deoxyandalusol (201) | 13-Epi-jabugodiol (202) | ||||

| |||||

| (+)-Plumosol (203) | |||||

| |||||

| Name | R | R′ | R1 | R2 | R3 |

| Stachysic acid (204) | COOH | CH3 | H | OAc | H |

| 6β-hydroxy-ent-kaur-16-ene (205) | CH3 | CH3 | H | OH | H |

| 6β,18-dihydroxy-ent-kaur-16-ene (206) | CH2OH | CH3 | H | OH | H |

| Ent-3α-acetoxy-kaur-16-en-19-oic acid (207) | CH3 | COOH | OAc | H | H |

| 3α,19-Dihydroxy-ent-kaur-16-ene (208) | CH3 | CH2OH | OH | H | H |

| Ent-3α-hydroxy-kaur-16-en-19-oic acid (209) | CH3 | COOH | OH | H | H |

| 11a,18-Dihydroxy-ent-kaur-16-ene (210) | CH2OH | CH3 | H | H | OH |

Horminone (211) | |||||

Stachyrosane 1 (212) |

Stachyrosane 2 (213) |

||||

Betolide (214) |

Betonicolide (215) |

||||

|

Name | R1 | R2 | R3 | |

| Betonicoside A (216) | O-Glc | CH2OH | O-Glc | ||

| Betonicoside B (217) | O-Glc | CH2OH | OH | ||

| Betonicoside C (218) | OH | CH2OH | O-Glc | ||

| Betonicoside D (219) | OH | CH2O-Glc | OH | ||

Glc: Glucose.

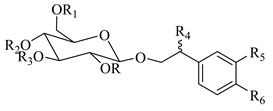

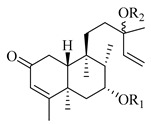

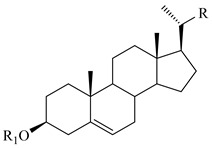

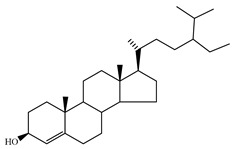

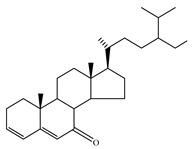

Table 28.

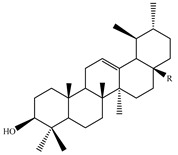

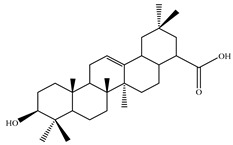

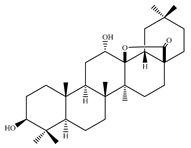

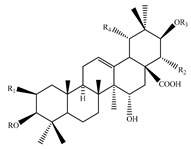

Triterpene derivatives, Phytosterols and Phytoecdysteroids from Stachys spp.

|

Stigmasterol (220) | R=

|

|

| R1=H | |||

| β-Sitosterol (221) | R=

|

||

| R1= H | |||

| 3-O-β-Sitosterol-glucoside (222) | R=

|

||

| R1=Glc | |||

Lawsaritol (223) |

Stigmastan-3,5-dien-7-one (224) |

||

α-Amyrin R=CH3 (225) Ursolic acid R=COOH (226) |

Oleanolic acid (227) |

||

12α-hydroxy-oleanolic lactone (228) |

|||

| |||

| Stachyssaponin A (229) | R=Glc-Rha, R1=H, R2=Glc-Ara, R3=H, R4=OH | ||

| Stachyssaponin B (230) | R=Glc, R1=Ara, R2=H, R3=Glc, R4=H | ||

|

Stachyssaponin I R=OGlc-Ara, R1=Ara (231) Stachyssaponin II R=OGlc-Ara, R1=Ara-Rha (232) Stachyssaponin III R=OGlc-Xyl, R1=Ara-Rha (233) Stachyssaponin IV R=OGlc-Ara, R1=Ara-Rha-Xyl (234) Stachyssaponin V R=OGlc-Ara, R1=Ara-Rha-Xyl-3Ac (235) Stachyssaponin VI R=OGlc-Ara, R1= Ara-Rha-Xyl-4Ac (236) Stachyssaponin VII R=OGlc-Ara, R1=Ara-Rha-(3Glc)-Xyl (237) Stachyssaponin VIII R=OGlc-Xyl, R1=Ara-Rha-Xyl (238) |

||

|

20-Hydroxyecdysone (239) R1=R2=R3=R5=H, R4=OH, R6=CH3 | ||

| Polipodin B (240) R1=R2=R5=H, R3=R4=OH, R6=CH3 | |||

| Integristeron A (241) R2=R3=R5=H, R1=R4=OH, R6=CH3 | |||

|

2-Desoxy-20-hydroxyecdysone (242) R1=OH, R2=H | ||

| 2-Desoxyecdyson (243) R1=R2=H | |||

Glc: Glucose, Xyl: Xylose, Rha: Rhamnose, Ara: Arabinose.

Table 29.

Chemical structures of megastigmane derivatives from Stachys spp.

|

|

| Byzantionoside A (244) | Byzantionoside B (245) |

|

|

| Icariside B2 (246) | (6R, 9R)- and (6R, 9S)-3-oxo-α-ionol glucosides (247) |

|

|

| Blumeol C glucoside (248) | Vomifoliol (249) |

|

|

| Dehydrovomifoliol (250) | Citroside A (251) |

Glc: Glucose.

Table 30.

Pharmacological activities of Stachys spp.

| Species | Extract or Compound | Activity a | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| S. aegyptiaca Pers. | Stachysolon diacetate (180) |

Cytotoxicity HepG2 cell line IC50: 59.5 μM |

[132] |