Abstract

Background: Intestinal ischemic reperfusion (I/R) injury is associated with a high mortality rate; this condition is also related to significant endotoxemia and systemic inflammation. The preservation of tissue perfusion and a sufficient blood flow are required to deliver nutrients and oxygen, preserve metabolic pathways, and eliminate waste products. Oxidative stress plays a fundamental role in intestinal I/R injury and leads to disruption of the mucosal barrier and necrosis, allowing the migration of endotoxins and luminal bacteria into the systemic circulation. In this study, we evaluated the beneficial effects of a cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 inhibitor—firocoxib—plus the antioxidant vitamin C in a rat model of intestinal I/R injury. Methods: We used a rat model of I/R injury in which the superior mesenteric artery was clamped for 30 min by a vascular clamp, and the animals were then allowed 1 h of reperfusion. Results: Our results show the importance of combined anti-inflammatory and antioxidant treatment for the prevention of intestinal I/R injury that leads to reduced systemic endotoxemia. We observed a significantly synergistic effect of firocoxib and vitamin C in reducing intestinal wall damage and oxidative stress, leading to a significant reduction of inflammation and endotoxemia. Conclusions: Our results indicate that this approach could be a new pharmacological protocol for intestinal colic or ischemic injury-induced endotoxemia.

Keywords: intestinal strangulation, antioxidant

1. Introduction

Intestinal obstruction has been defined as simultaneous vascular and luminal damage that can be of ischemic or hemorrhagic origin [1]. It leads to disruption of the intestinal barrier function, hypovolemia, endotoxemia, and cytotoxic shock [2]. In particular, ischemic strangulating obstruction comprises simultaneous occlusion of the arterial vasculature and intestinal venous vasculature, resulting in cyanotic and blanched serosa [1]. The duration and magnitude of the reduced blood flow determine the severity of ischemic tissue. Most tissues can resist a considerable decrease in blood flow due to their ability to increase oxygen extraction and stock cellular energy [3]. Restoration of the oxygen supply and blood flow in ischemic tissues is required to re-establish a regular function and repair impaired components. Small intestine and large colon obstructions are common causes of acute abdominal disease in horses. Small intestine obstruction frequently results from either a volvulus or incarceration at several intraabdominal locations. The pathophysiological processes associated with ischemia and reperfusion (I/R) likely occur in the intestinal tract of horses during and after the surgical correction of naturally acquired intestinal vascular compromise. Intestinal ischemic injury in horses is associated with a high mortality rate—50% to 80%. The prognosis depends on the degree and duration of ischemia before surgical intervention. Despite surgical correction, intensive medical therapy, and supportive care, the perioperative mortality is high. This is likely a reflection of the severe damage the intestine sustains during the ischemic period and the further injury that occurs upon reperfusion. The progressive mucosal epithelial damage induces a disruption of the mucosal barrier and necrosis, allowing the migration of endotoxins and luminal bacteria into the systemic circulation.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) work through the inhibition of cyclooxygenase (COX) and are highly effective for the treatment of pain and inflammation in horses, reducing local prostaglandin (PG) synthesis and inflammatory mediators. While COX-1 is constitutively expressed in the equine intestine and is responsible for PG synthesis in normal conditions [4], COX-2 is upregulated in response to injury. Firocoxib is a COX-2-selective NSAID extensively used in horses, although the use of NSAIDs in the pharmacological treatment of clinical conditions due to damage from ischemia reperfusion has not been completely elucidated [5,6,7]. In particular, several studies have proven the superior efficacy of firocoxib in the treatment of intestinal ischemia in horses compared to flumixine meglumine [8]. During I/R injury and related cellular damage, oxidative stress also plays a key role. The restoration of tissue oxygenation, however, is followed by biochemical changes that can lead to an increased generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and be fatal to tissues. In particular, in the small intestine of horses, during complete arteriovenous ischemia, ROS production is responsible for lipid peroxidation. A decrease in the activity of superoxide dismutase (SOD)—an endogenous anti-oxidative enzyme—accompanies an increased tissue malondialdehyde (MDA) concentration during ischemia, potentially predisposing the intestinal mucosa to I/R damage. Several previous studies from our group have described the beneficial effects of natural antioxidant treatments in different pathologies [9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17]. Unfortunately, firocoxib did not display any antioxidant activity. On the other hand, the efficacy of the antioxidant vitamin C in restoring the oxidative balance is well-known [18,19].

Therefore, in line with the available evidence, the aim of the present study was to combine the COX-2 inhibitor firocoxib and the antioxidant vitamin C to fight the oxidative stress that characterizes intestinal I/R injury in horses using a rat system as a model.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

Male rats (Sprague–Dawley, 200–230 g; Envigo, Milan, Italy) were employed. The University of Messina Review Board for Animal Care (OPBA) approved the study. All animal experiments complied with the new Italian regulations (D.Lgs 2014/26), EU regulations (EU Directive 2010/63), and ARRIVE guidelines.

2.2. Experimental Protocol

Rats were randomly divided into the following groups (n = 10): Firocoxib (10 mg/kg), vitamin C (750 mg/kg) alone, or firocoxib (10 mg/kg) in combination with vitamin C (750 mg/kg), administered intraperitoneally 30 min before I/R induction [19,20,21,22]. Animals were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (45 mg/kg) and the induction of I/R was performed as previously described [23]. Briefly, the superior mesenteric artery was occluded for 30 min with a vascular clamp, and the animals were then allowed 1 h of reperfusion after clamp removal. After this time, blood was collected by intra-cardiac puncture and animals were sacrificed by cervical dislocation under anesthesia. Ileum tissue samples were collected for histological and biochemical analyses. In another set of experiments, following reperfusion, the various groups of animals were observed for 4 h to evaluate survival differences [24].

2.3. Experimental Groups

-

(1)

I/R + vehicle (saline): Rats were subjected to surgery and treated with a vehicle.

-

(2)

I/R + firocoxib (10 mg/kg): Rats were subjected to surgery and treated with firocoxib (10 mg/kg).

-

(3)

I/R + vitamin C (750 mg/kg): Rats were subjected to surgery and treated with vitamin C (750 mg/kg).

-

(4)

I/R + firocoxib (10 mg/kg) + vitamin C (750 mg/kg): Rats were subjected to surgery and treated with firocoxib (10 mg/kg) + vitamin C (750 mg/kg).

-

(5)

Sham groups: Animals were operated on with surgical steps; however, they were not subjected to I/R and were treated with either a vehicle, firocoxib alone, vitamin C alone, or firocoxib + vitamin C.

2.4. Measurement of Lipid Peroxidation

Lipid peroxidation was evaluated by a reaction between malondialdehyde (MDA), thiobarbituric acid, and lipid peroxides and measured spectrophometrically at 532 nm [13]. The results were expressed as nanomoles of thiobarbituric acid (TBA) reactant formed per gram of wet tissue.

2.5. Myeloperoxidase Activity

Myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity, which is an indicator of polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMN) accumulation, was determined spectrophotometrically at 650 nm [25]. MPO activity was expressed in U per gram weight of wet tissue and defined as the quantity of enzyme degrading 1 µmol of peroxide min−1 at 37 °C [26].

2.6. Measurement of the Protein Carbonyl Content

The protein carbonyl content (PCC) was evaluated spectrophotometrically at 370 nm by the reaction between 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine and the carbonyl group [27]. The results were expressed as nanomoles of carbonyl per milligram of protein.

2.7. Determination of Antioxidant Enzyme Activity

Ileum tissues were homogenized, and the supernatant collected for the determination of total glutathione (Glutathione Assay Kit; Trevigen Inc., Gaithersburg, MD, USA). The results of glutathione (GSH) levels were expressed as nmol/mg of protein [23]. SOD activity was determined on ileum tissue homogenate according to the nitro blue tetrazolium reduction assay [28]. Superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity was expressed as U/mg of protein. Catalase (CAT) activity was estimated by a decreased absorbance of H2O2 at 240 nm [29]. Glutathione peroxidase (GPx) activity was determined as described [23]. Oxidized glutathione (GSSG) is reduced by glutathione reductase and NADPH. The oxidation of NADPH to NADP+ was evaluated by a decreased absorbance at 340 nm, and GPx activity was expressed as U/mg of protein. Glutathione-S-transferase (GST) activity was determined spectrophotometrically at 340 nm [23]. For this measurement, 1 U is equal to the amount of enzyme producing 1 mmol of CDNB-GSH conjugate per minute.

2.8. Evaluation of PGE2, Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha (TNF-α), Interleukin (IL)-6, IL-1β, D-Lactate, Diamine Oxidase (DAO), and Endotoxin Levels

Serum interleukin IL-1β and IL-6 and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) levels were determined using an ELISA kit (R&D Systems Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA) [30]. Serum levels of D-lactate and DAO were investigated spectrophotometrically (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA; Merck KGaA). Serum levels of endotoxin were determined by a Limulus Amebocyte Lysate Assay kit (Shanghai Biochemical Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) [31]. PGE2 ileal tissue expression was determined according to the manufacturer’s instructions (MyBiosource, Bergamo, Italy) [32].

2.9. Histological Examination

Ileum tissues were collected after 1 h of reperfusion. After fixing the tissues in buffered formaldehyde solution (10% in phosphate buffered saline (PBS)), histological sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and evaluated using a Leica DM6 microscope (Leica Microsystems SpA, Milan, Italy) associated with Leica LAS X Navigator software (Leica Microsystems SpA, Milan, Italy). The morphological criteria were considered as already described [33]: 0, no damage; 1 (mild), focal epithelial edema and necrosis; 2 (moderate), diffuse swelling and necrosis of the villi; 3 (severe), necrosis with the presence of neutrophil infiltrate in the submucosa; and 4 (highly severe), widespread necrosis with massive neutrophil infiltrate and hemorrhage. All images were acquired at 10× magnification (250 μm).

2.10. Bacterial Translocation

Mesenteric lymph nodes (MLNs) and caudal lymph nodes (CLNs) were harvested for bacteriological analysis [34]. In addition, blood underwent bacterial colony counts [35].

2.11. Western Blot Analysis

Western blots were performed as described in our previous studies [14,36]. Specific primary antibody anti-COX-2 (1:600, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or anti-PGE2 (1:700; Bioss Antibodies) was mixed in 1× PBS, 5% w/v nonfat dried milk, and 0.1% Tween-20, and incubated at 4 °C, overnight. After that, blots were incubated with the peroxidase-conjugated bovine anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody or peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:2000, Jackson Immuno Research) for 1 h at room temperature. To verify the equal amounts of protein, membranes were also incubated with the antibody against beta actin (1:1000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Signals were detected with enhanced chemiluminescence detection system reagent (Super-Signal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate, Pierce). The relative expression of protein bands was quantified by densitometry with Bio-Rad ChemiDoc XRS software and standardized to β-actin levels. Images of blot signals were imported to analysis software (Image Quant TL, v2003).

2.12. Statistical Evaluation

All values in the figures and text are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of N number of animals. The results were analyzed by one-way ANOVA, followed by Bonferroni’s post-hoc test, for multiple comparisons. A p-value of <0.05 was considered significant; * p < 0.05 vs. sham + vehicle, # p < 0.05 vs. vehicle, ** p < 0.01 vs. sham + vehicle, ## p < 0.01 vs. vehicle, *** p < 0.001 vs. sham + vehicle, and ### p < 0.001 vs. vehicle.

3. Results

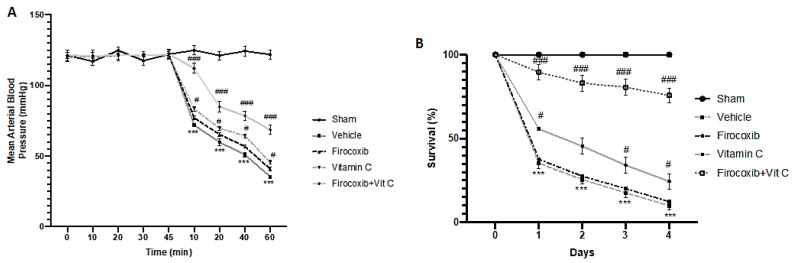

3.1. Firocoxib+Vit C Reduces Lethality and Falls of the Arterial Blood Pressure

In animals with I/R injury, reperfusion after 30 min of ischemia caused an abrupt and sustained decrease in systemic blood pressure, indicating circulatory shock (Figure 1A, Supplemental Figure S1). An intense shock state is associated with an increased mortality at the end of the reperfusion period (Figure 1B, Supplemental Figure S1). Firocoxib and vitamin C decreased mortality and falling blood pressure. Firocoxib+Vit C treatment significantly reduced mortality (Figure 1B, Supplemental Figure S1) and falling blood pressure (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Effect of combined therapy of firocoxib and vitamin C on ischemic reperfusion (I/R)-induced mortality and arterial blood pressure: (A) Mean arterial blood pressure and (B) survival (%). n = 5 animals from each group for each analysis. A p-value of <0.05 was considered significant; # p < 0.05 vs. vehicle, *** p < 0.001 vs. sham + vehicle, and ### p < 0.001 vs. vehicle.

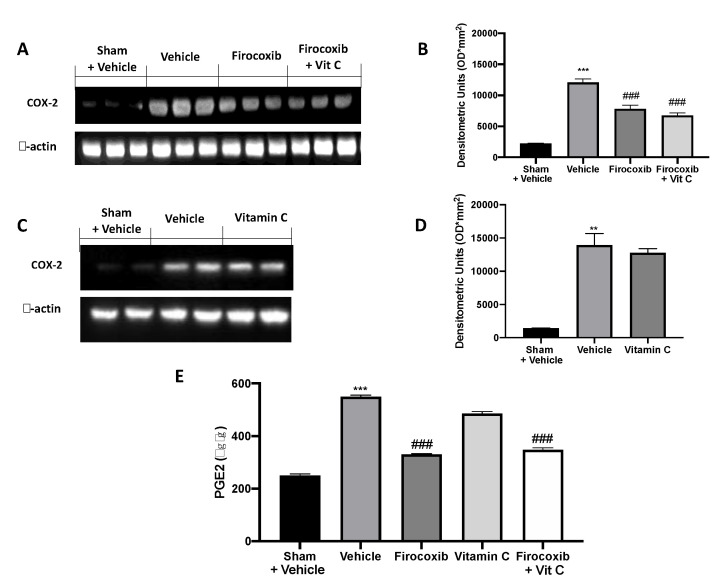

3.2. Firocoxib+Vit C Reduces COX-2 and PGE2 Expression

Western blot analysis of ileum tissue showed increased COX-2 expression in vehicle-treated animals compared to the sham + vehicle group (Figure 2A, also see densitometric analysis B, C; see densitometric analysis D, Supplemental Figure S1). Firocoxib and Firocoxib+Vit C decreased COX-2 and PGE2 levels (Figure 2A, see densitometric analysis B, E). Vitamin C treatment did not affect COX-2 expression (Figure 2 C, see densitometric analysis D) and PGE2 levels (Figure 2E).

Figure 2.

Effect of combined firocoxib and vitamin C therapy on cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 and PGE2 expression: Western blot analysis of (A) COX-2, (B) densitometric analysis, (C) COX-2, (D) densitometric analysis, (E) PGE2 expression. n = 5 animals from each group for each analysis. A p-value of <0.05 was considered significant; ** p < 0.01 vs. sham + vehicle, *** p < 0.001 vs. sham + vehicle, and ### p < 0.001 vs. vehicle.

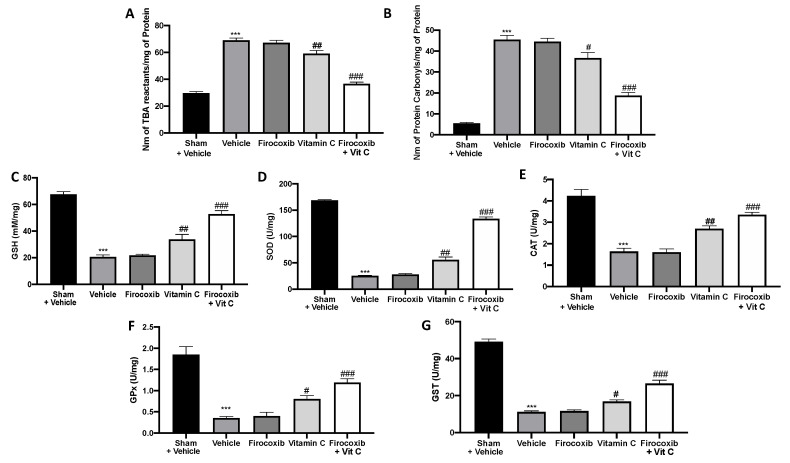

3.3. Firocoxib+Vit C Enhances the Antioxidant/Oxidant Balance during I/R Injury

ROS production was one of the earliest mechanisms postulated to explain tissue demise after an ischemic insult. ROS generated by hypoxia or reoxygenation are now recognized to interact with physiological signal transducers rather than to be simple reactants that peroxidize membrane lipids, oxidize DNA, or denature enzyme proteins. Animals treated with the vehicle showed increased lipid peroxidation (Figure 3A) and PCC (Figure 3B). No difference between vehicle-treated and firocoxib-treated rats was detected. Firocoxib+Vit C treatment was more effective in reducing lipid peroxidation (Figure 3A, Figure S1) and PCC (Figure 3B, Figure S1) than vitamin C alone. I/R in vehicle-treated rats decreased the antioxidant enzyme activity of CAT, SOD, GST, GPx, and GSH. Firocoxib+Vit C treatment restored the antioxidant status changed by I/R injury (Figure 3C–G respectively, Figure S1). Firocoxib treatment alone was not able to significantly increase the antioxidant enzyme activity.

Figure 3.

Effect of combined firocoxib and vitamin C therapy on oxidative stress: (A) Lipid peroxidation, (B) protein carbonyl, (C) total glutathione (GSH), (D) superoxide dismutase (SOD), (E) catalase (CAT), (F) glutathione peroxidase (GPx), and (G) glutathione-S-transferase (GST). n = 5 animals from each group for each analysis. A p-value of <0.05 was considered significant; # p < 0.05 vs. vehicle, ## p < 0.01 vs. vehicle, *** p < 0.001 vs. sham + vehicle, and ### p < 0.001 vs. vehicle.

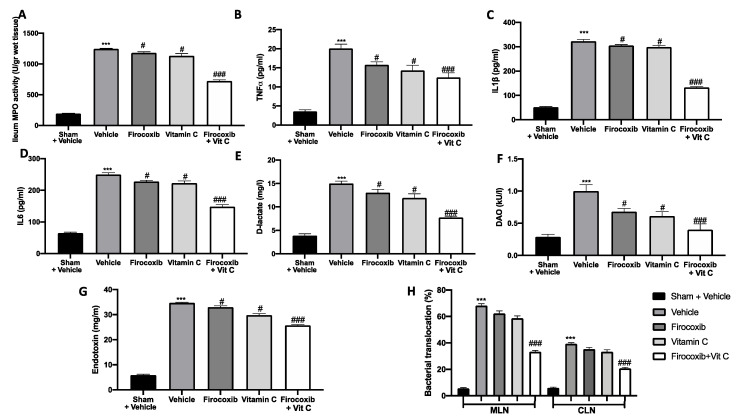

3.4. Firocoxib+Vit C Modulates MPO Activity, the Cytokine Plasma Level, the Intestinal Barrier Function, and Bacterial Translocation

The reperfusion of the ischemic mesenteric circulation was also characterized by an increase in MPO activity, which is an indicator of neutrophil accumulation in the ileum. MPO activity was reduced by both treatments (Figure 4A). In all analyzed parameters, the Firocoxib+Vit C treatment displayed major efficacy. Additionally, the inflammatory process is also characterized by an increased expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines. TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β plasma levels were increased in vehicle-treated animals (Figure 4B–D). Firocoxib, vitamin C, and Firocoxib+Vit C administration reduced cytokine plasma levels (Figure 4B–D). Additionally, all treatments reduced D-lactate, DAO, and endotoxin serum levels, showing protective effects on the intestinal barrier function (Figure 4E–G). Moreover, vehicle-treated mice showed increased bacterial translocation to mesenteric lymph nodes (MLNs) and caudal lymph nodes (CLNs). Firocoxib, vitamin C, and Firocoxib+Vit C treatment reduced bacterial translocation to MLNs and CLNs (Figure 4H). Firocoxib+Vit C treatment displayed more efficacy than firocoxib alone and vitamin C in reducing cytokine levels, improving the mucosal barrier function and decreasing bacterial translocation.

Figure 4.

Effect of combined therapy of firocoxib and vitamin C on myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), interleukin (IL)-6, IL-1β, D-lactate, diamine oxidase (DAO), and endotoxin levels, and bacterial migration: (A) MPO activity, (B) serum TNF-α, (C) IL-1β, (D) IL-6, (E) D-lactate, (F) DAO, (G) endotoxin levels, and (H) bacterial translocation. n = 5 animals from each group for each analysis. A p-value of <0.05 was considered significant; # p < 0.05 vs. vehicle, *** p < 0.001 vs. sham + vehicle, and ### p < 0.001 vs. vehicle.

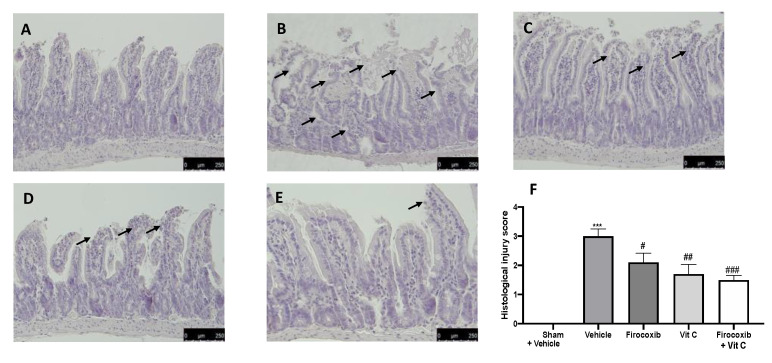

3.5. Firocoxib+Vit C Reduces Histological Alterations Caused by I/R Injury

Histological examination of the ileum after the I/R injury revealed expected and characteristic pathological changes. Histological features of normal gut tissue were observed in gut tissues prepared from sham rats (Figure 5A,F). The ileum of vehicle-treated animals displayed damage to the villi tips and diffuse inflammatory cell infiltrates in the submucosa (Figure 5B,F). Firocoxib (Figure 5C,F) and vitamin C (Figure 5D,F) and Firocoxib+Vit C showed decreased ileum damage (Figure 5E,F).

Figure 5.

Effect of combined therapy of firocoxib and vitamin C on I/R-induced intestine injury and MPO activity: hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining: (A) sham + vehicle, (B) vehicle, (C) firocoxib, (D) vitamin C, (E) Firocoxib+Vit C, (F) histological injury score. n = 5 animals from each group for each analysis. A p-value of <0.05 was considered significant; # p < 0.05 vs. vehicle, ## p < 0.01 vs. vehicle, *** p < 0.001 vs. sham + vehicle, and ### p < 0.001 vs. vehicle.

4. Discussion

The aim of this study was to evaluate the combined treatment of firocoxib—a COX-2 selective inhibitor—and vitamin C—a strong antioxidant molecule—for fighting the inflammation and oxidative stress that characterize intestinal I/R injury, using a rat system as a model. This could be an important pharmacological protocol across different species in the management of clinical conditions such as equine colic. Our results show that, as expected, based on the known mechanism of action of these molecules, firocoxib administration was able to reduce COX-2 expression, while vitamin C did not. The combined administration of both was able to downregulate COX-2 and PGE2 expression. Additionally, this combined therapy increased the endogenous antioxidant systems. Endogenous antioxidant systems such as catalase, superoxide dismutase, and glutathione peroxidase protect against oxidant injury [37]. In order to prevent the secondary generation of hydroxyl radicals, catalase reduces hydrogen peroxide to water. Superoxide dismutase transforms superoxide anions to hydrogen peroxide. Glutathione peroxidase uses glutathione as the substrate to transform hydrogen peroxide to water [38]. Treatment with firocoxib alone did not show any antioxidant activity compared to combined therapy. It is well-described that rats subjected to I/R injury display a significant increase in tissue MPO activity, cytokine levels, and marked injury to the distal ileum [24]. Firocoxib administered in combination with vitamin C was able to reduce small intestine damage and decrease neutrophil accumulation in the injured tissues, as shown by the MPO activity, with more efficacy than the compounds administered alone. The consequences of intestinal I/R injury include an altered absorptive function of the intestine; increased intestinal hyperpermeability with bacterial translocation; and the production of molecules such as hydrogen peroxide, superoxide, endotoxins, and inflammatory cytokines that may harm distant organs [39]. Numerous studies have shown that an increase of both D-lactate and DAO serum levels indicates functional and structural alteration in the intestinal mucosa permeability [40,41,42]. DAO is an enzyme primarily resident in the intestinal villus; its serum expression also increases following impairment to the mucosal barrier function [43]. The increased barrier permeability is also related to increased endotoxin serum levels. Endotoxins are molecules in the walls of bacilli that induce septic shock, sepsis, and gut-derived bacteremia; furthermore, these molecules are able to induce a very harmful inflammatory response known as a “cytokine storm” [44]. The combined administration of firocoxib with vitamin C was able to reduce impairment of the intestinal mucosal barrier, as shown by decreasing D-lactate, DAO, and endotoxin serum levels. Intestinal I/R injury also results in multiorgan failure and the release of several endogenous inflammatory mediators. We detected increased plasma cytokine levels and the translocation of bacteria and toxins in animals subjected to I/R [45]. Firocoxib treatment in combination with vitamin C was able to decrease cytokine plasma expression, toxins, and bacterial migration. From a histological point of view, I/R injury decreases the villus height, mucosal thickness, and crypt depth [46]. The combined administration of firocoxib with vitamin C, by reducing COX-2 expression and the related PG and cytokine production, exhibited an antioxidant capacity and, by reducing neutrophil recruitment to the lesion site, histological protection.

5. Conclusions

The results of our study show the usefulness of pharmacological combination therapy of firocoxib and vitamin C for alleviating intestinal injury due to ischemic reperfusion events. In particular, we show the importance of combined anti-inflammatory and antioxidant treatment for preventing intestinal I/R injury, which leads to reduced systemic endotoxemia. Our results indicate that this pharmacological approach could be a new protocol for managing ischemic conditions and combatting endotoxemia, such as that faced in equine intestinal colic.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3921/9/10/930/s1. Figure S1. Effect of combined therapy of firocoxib and vitamin C on sham animals.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.C. and R.D.P.; methodology, D.I.; software, M.C.; validation, M.C., R.S., and E.G.; formal analysis, R.C. and T.G.; investigation, A.F.P.; resources, R.F.; data curation, R.D.; writing—original draft preparation, R.F.; writing—review and editing, R.D.P.; visualization, E.G.; supervision, R.D.P.; project administration, S.C.; funding acquisition, S.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Snyder J.R. The pathophysiology of intestinal damage: Effects of luminal distention and ischemia. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Equine Pract. 1989;5:247–270. doi: 10.1016/S0749-0739(17)30587-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tinker M.K., White N.A., Lessard P., Thatcher C.D., Pelzer K.D., Davis B., Carmel D.K. Prospective study of equine colic incidence and mortality. Equine Vet. J. 1997;29:448–453. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-3306.1997.tb03157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Joyner M.J., Casey D.P. Regulation of increased blood flow (hyperemia) to muscles during exercise: A hierarchy of competing physiological needs. Physiol. Rev. 2015 doi: 10.1152/physrev.00035.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tomlinson J.E., Wilder B.O., Young K.M., Blikslager A.T. Effects of flunixin meglumine or etodolac treatment on mucosal recovery of equine jejunum after ischemia. Am. J. Vet. Res. 2004;65:761–769. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.2004.65.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCann M.E., Andersen D.R., Zhang D., Brideau C., Black W.C., Hanson P.D., Hickey G.J. In vitro effects and in vivo efficacy of a novel cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor in dogs with experimentally induced synovitis. Am. J. Vet. Res. 2004;65:503–512. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.2004.65.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCann M.E., Rickes E.L., Hora D.F., Cunningham P.K., Zhang D., Brideau C., Black W.C., Hickey G.J. In vitro effects and in vivo efficacy of a novel cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor in cats with lipopolysaccharide-induced pyrexia. Am. J. Vet. Res. 2005;66:1278–1284. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.2005.66.1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ziegler A., Freeman C., Fogle C., Burke M., Davis J., Cook V., Southwood L., Blikslager A. Multicentre, blinded, randomised clinical trial comparing the use of flunixin meglumine with firocoxib in horses with small intestinal strangulating obstruction. Equine Vet. J. 2019;51:329–335. doi: 10.1111/evj.13013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cook V.L., Meyer C.T., Campbell N.B., Blikslager A.T. Effect of firocoxib or flunixin meglumine on recovery of ischemic-injured equine jejunum. Am. J. Vet. Res. 2009;70:992–1000. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.70.8.992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Di Paola R., Fusco R., Gugliandolo E., Crupi R., Evangelista M., Granese R., Cuzzocrea S. Co-micronized palmitoylethanolamide/polydatin treatment causes endometriotic lesion regression in a rodent model of surgically induced endometriosis. Front. Pharmacol. 2016;7:382. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2016.00382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gugliandolo E., Fusco R., D’Amico R., Peditto M., Oteri G., Di Paola R., Cuzzocrea S., Navarra M. Treatment With a Flavonoid-Rich Fraction of Bergamot Juice Improved Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Periodontitis in Rats. Front. Pharmacol. 2018;9:1563. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.01563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fusco R., Cirmi S., Gugliandolo E., Di Paola R., Cuzzocrea S., Navarra M. Anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of a flavonoid-rich extract from orange juice in experimental colitis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2017;108:S37. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2017.04.144. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Britti D., Crupi R., Impellizzeri D., Gugliandolo E., Fusco R., Schievano C., Morittu V.M., Evangelista M., Di Paola R., Cuzzocrea S. A novel composite formulation of palmitoylethanolamide and quercetin decreases inflammation and relieves pain in inflammatory and osteoarthritic pain models. BMC Vet. Res. 2017;13:229. doi: 10.1186/s12917-017-1151-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cordaro M., Impellizzeri D., Siracusa R., Gugliandolo E., Fusco R., Inferrera A., Esposito E., Di Paola R., Cuzzocrea S. Effects of a co-micronized composite containing palmitoylethanolamide and polydatin in an experimental model of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2017;329:231–240. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2017.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gugliandolo E., Fusco R., Biundo F., D’Amico R., Benedetto F., Di Paola R., Cuzzocrea S. Palmitoylethanolamide and Polydatin combination reduces inflammation and oxidative stress in vascular injury. Pharmacol. Res. 2017;123:83–92. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2017.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Di Paola R., Fusco R., Gugliandolo E., D’Amico R., Campolo M., Latteri S., Carughi A., Mandalari G., Cuzzocrea S. The Antioxidant Activity of Pistachios Reduces Cardiac Tissue Injury of Acute Ischemia/Reperfusion (I/R) in Diabetic Streptozotocin (STZ)-Induced Hyperglycaemic Rats. Front. Pharmacol. 2018;9:51. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.00051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.D’Amico R., Fusco R., Gugliandolo E., Cordaro M., Siracusa R., Impellizzeri D., Peritore A.F., Crupi R., Cuzzocrea S., Di Paola R. Effects of a new compound containing Palmitoylethanolamide and Baicalein in myocardial ischaemia/reperfusion injury in vivo. Phytomedicine. 2019;54:27–42. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2018.09.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Siracusa R., Fusco R., Peritore A.F., Cordaro M., D’Amico R., Genovese T., Gugliandolo E., Crupi R., Smeriglio A., Mandalari G., et al. The Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Properties of Anacardium occidentale L. Cashew Nuts in a Mouse Model of Colitis. Nutrients. 2020;12:834. doi: 10.3390/nu12030834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spoelstra-de Man A.M.E., Elbers P.W.G., Oudemans-van Straaten H.M. Making sense of early high-dose intravenous vitamin C in ischemia/reperfusion injury. Crit. Care. 2018;22:70. doi: 10.1186/s13054-018-1996-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Higa O.H., Parra E.R., Ab’Saber A.M., Farhat C., Higa R., Capelozzi V.L. Protective effects of ascorbic acid pretreatment in a rat model of intestinal ischemia-reperfusion injury: A histomorphometric study. Clinics. 2007;62:315–320. doi: 10.1590/S1807-59322007000300017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reddyjarugu B., Pavek T., Southard T., Barry J., Singh B. Analgesic efficacy of firocoxib, a selective inhibitor of cyclooxygenase 2, in a mouse model of incisional pain. J. Am. Assoc. Lab. Anim. Sci. 2015;54:405–410. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.De Sales K.P.F., Pinto B.A.S., Ribeiro N.L.X., Melo T.M., Galvão-Moreira L.V., de Brito Filho S.B., Nigri F. Effects of Vitamin C on the Prevention of Ischemia-Reperfusion Brain Injury: Experimental Study in Rats. Int. J. Vasc. Med. 2019;2019:4090549. doi: 10.1155/2019/4090549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Campion J., Milagro F.I., Fernandez D., Martinez J.A. Diferential gene expression and adiposity reduction induced by ascorbic acid supplementation in a cafeteria model of obesity. J. Physiol. Biochem. 2006;62:71–80. doi: 10.1007/BF03174068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sun Y., Xu Y., Wang G.-N. Pterostilbene prevents intestinal ischemia reperfusion injury in Wistar rats via modulation of antioxidant defense and inflammation. Trop. J. Pharm. Res. 2015;14:1383–1391. doi: 10.4314/tjpr.v14i8.9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muia C., Mazzon E., Di Paola R., Genovese T., Menegazzi M., Caputi A.P., Suzuki H., Cuzzocrea S. Green tea polyphenol extract attenuates ischemia/reperfusion injury of the gut. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2005;371:364–374. doi: 10.1007/s00210-005-1076-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gugliandolo E., Fusco R., D’Amico R., Militi A., Oteri G., Wallace J.L., Di Paola R., Cuzzocrea S. Anti-inflammatory effect of ATB-352, a H2S -releasing ketoprofen derivative, on lipopolysaccharide-induced periodontitis in rats. Pharmacol. Res. 2018;132:220–231. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2017.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pallio G., Bitto A., Pizzino G., Galfo F., Irrera N., Squadrito F., Squadrito G., Pallio S., Anastasi G.P., Cutroneo G., et al. Adenosine Receptor Stimulation by Polydeoxyribonucleotide Improves Tissue Repair and Symptomology in Experimental Colitis. Front. Pharmacol. 2016;7:273. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2016.00273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levine R.L., Garland D., Oliver C.N., Amici A., Climent I., Lenz A.G., Ahn B.W., Shaltiel S., Stadtman E.R. Determination of carbonyl content in oxidatively modified proteins. Methods Enzymol. 1990;186:464–478. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)86141-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sun Y., Oberley L.W., Li Y. A simple method for clinical assay of superoxide dismutase. Clin. Chem. 1988;34:497–500. doi: 10.1093/clinchem/34.3.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aebi H. Methods of enzymatic analysis. Catalase. 1983:673–686. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Squadrito F., Micali A., Rinaldi M., Irrera N., Marini H., Puzzolo D., Pisani A., Lorenzini C., Valenti A., Laura R., et al. Polydeoxyribonucleotide, an Adenosine-A2A Receptor Agonist, Preserves Blood Testis Barrier from Cadmium-Induced Injury. Front. Pharmacol. 2016;7:537. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2016.00537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen S., Li X., Wang Y., Mu P., Chen C., Huang P., Liu D. Ginsenoside Rb1 attenuates intestinal ischemia/reperfusioninduced inflammation and oxidative stress via activation of the PI3K/Akt/Nrf2 signaling pathway. Mol. Med. Rep. 2019;19:3633–3641. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2019.10018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Büyükgebiz O., Aktan A.Ö., Yeĝen C., Yalçin A.S., Haklar G., Yalin R., Ercan Z.S. Captopril increases endothelin serum concentrations and preserves intestinal mucosa after mesenteric ischemia-reperfusion injury. Res. Exp. Med. 1994;194:339–348. doi: 10.1007/BF02576396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Di Paola R., Menegazzi M., Mazzon E., Genovese T., Crisafulli C., Dal Bosco M., Zou Z., Suzuki H., Cuzzocrea S. Protective effects of glycyrrhizin in a gut hypoxia (ischemia)-reoxygenation (reperfusion) model. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35:687–697. doi: 10.1007/s00134-008-1334-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang Y., Ye M., Wang C., Wang Z., Zhou W. Protective effect of CDDO-imidazolide against intestinal ischemia/reperfusion injury in mice. Eur. J. Inflamm. 2018;16:2058739218802681. doi: 10.1177/2058739218802681. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu X., Ren J., Chen G., Wu L., Song X., Li G., Deng Y., Wang G., Gu G., Li J. Systemic blockade of P2X7 receptor protects against sepsis-induced intestinal barrier disruption. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:1–13. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-04231-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pizzino G., Bitto A., Pallio G., Irrera N., Galfo F., Interdonato M., Mecchio A., De Luca F., Minutoli L., Squadrito F., et al. Blockade of the JNK signalling as a rational therapeutic approach to modulate the early and late steps of the inflammatory cascade in polymicrobial sepsis. Mediat. Inflamm. 2015;2015:591572. doi: 10.1155/2015/591572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Flaherty J.T., Weisfeldt M.L. Reperfusion injury. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1988;5:409–419. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(88)90115-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Flohé L. Glutathione peroxidase brought into focus. Free Radic. Biol. 1982;5:223–253. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nier A., Engstler A.J., Maier I.B., Bergheim I. Markers of intestinal permeability are already altered in early stages of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Studies in children. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0183282. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0183282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jin X., Yu C.H., Lv G.C., Li Y.M. Increased intestinal permeability in pathogenesis and progress of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in rats. World J. Gastroenterol. 2007;13:1732–1736. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i11.1732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Song W.B., Lv Y.H., Zhang Z.S., Li Y.N., Xiao L.P., Yu X.P., Wang Y.Y., Ji H.L., Ma L. Soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1, D-lactate and diamine oxidase in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 2009;15:3916–3919. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.3916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li H., Chen Y., Huo F., Wang Y., Zhang D. Association between acute gastrointestinal injury and biomarkers of intestinal barrier function in critically ill patients. BMC Gastroenterol. 2017;17:45. doi: 10.1186/s12876-017-0603-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guo Y.Y., Liu M.L., He X.D., Jiang C.Q., Liu R.L. Functional changes of intestinal mucosal barrier in surgically critical patients. World J. Emerg. Med. 2010;1:205–208. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Uramatsu M., Matsumoto T., Tateda K., Shibuya K., Miyazaki S., Horino T., Tanabe M., Sumiyama Y., Kusachi S., Yamaguchi K. Involvement of endotoxin in the mortality of mice with gut-derived sepsis due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Microbiol. Immunol. 2010;54:330–337. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2010.00217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Meakins J.L., Marshall J.C. The Gut as the Motor of Multiple System Organ Failure. CV Mosby; St Louis, MO, USA: 1988. pp. 1333–1347. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chiu C.J., McArdle A.H., Brown R., Scott H.J., Gurd F.N. Intestinal mucosal lesion in low-flow states. I. A morphological, hemodynamic, and metabolic reappraisal. Arch. Surg. 1970;101:478–483. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1970.01340280030009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.