Abstract

Viral metagenomics next-generation sequencing (mNGS) is increasingly being used to characterize the human virome. The impact of viral nucleic extraction on virome profiling has been poorly studied. Here, we aimed to compare the sensitivity and sample and reagent contamination of three extraction methods used for viral mNGS: two automated platforms (eMAG; MagNA Pure 24, MP24) and the manual QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit (QIAamp). Clinical respiratory samples (positive for Respiratory Syncytial Virus or Herpes Simplex Virus), one mock sample (including five viruses isolated from respiratory samples), and a no-template control (NTC) were extracted and processed through an mNGS workflow. QIAamp yielded a lower proportion of viral reads for both clinical and mock samples. The sample cross-contamination was higher when using MP24, with up to 36.09% of the viral reads mapping to mock viruses in the NTC (vs. 1.53% and 1.45% for eMAG and QIAamp, respectively). The highest number of viral reads mapping to bacteriophages in the NTC was found with QIAamp, suggesting reagent contamination. Our results highlight the importance of the extraction method choice for accurate virome characterization.

Keywords: viral metagenomics, next-generation sequencing, acid nucleic extraction, sample cross-contamination, kitome

1. Introduction

The development of metagenomics next-generation sequencing (mNGS) has enabled the exploration of whole viral nucleic acids within a clinical sample (human virome) in order to detect pathogens not targeted by conventional PCR and to identify emerging viruses [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. Several studies have used various mNGS protocols to explore the human virome in diverse clinical samples, including human stools [9,10], blood [11,12], cerebrospinal fluid [13,14], human tissues [15,16], and respiratory tract samples [17,18,19,20,21]. However, the lack of standardization, the cost and duration of sequencing, and the complexity of bioinformatics analysis critically limit the wide implementation of mNGS approaches in clinical labs [22].

In particular, the extraction of viral nucleic acids is a crucial step in the molecular detection of viruses from clinical samples [23]. While there are many manual and automatic extraction methods available, it is important to choose the most sensitive and reliable one for mNGS. Numerous studies evaluating different extraction platforms in terms of their viral qPCR performance have found that the choice of extraction platform has a major impact on the reliability of the diagnostic results [24,25,26,27,28,29]. Furthermore, nucleic acid extraction methods can also impact bacteriome profiles [30,31,32] as well as the detection of particular viruses with mNGS [16,23,27,29].

Other potential issues related to extraction methods are sample cross-contamination (contamination from one sample to another) [24,33,34] and contamination by sequences present in the environment [32,34] or in the molecular biology reagents (referred to as the kitome) [35,36,37]. In viral mNGS studies, these two aspects constitute a major concern and must be precisely evaluated [38,39,40]. The impact of nucleic acid extraction methods on human virome characterization, kitome, and cross-contamination has thus far been poorly studied [41,42].

The aim of this study was to compare two automated extraction platforms commonly used in diagnostic laboratories, the eMAG (bioMérieux, Marcy-l′Étoile, France) and the MagNA Pure 24 (MP24) (Roche, Basel, Switzerland), and one manual QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit extraction (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), which is among one of the most popular methods used in research laboratories. The performance of each extraction kit was evaluated in terms of (1) their ability to detect different DNA and RNA viruses in one mock sample and in clinical samples, (2) their sample cross-contamination rate, and (3) the detection of the kitome.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design of the Mock Virome

The mock virome included known concentrations of five viruses isolated from respiratory samples (Table 1). These viruses were selected as representatives of a wide range of virus characteristics, such as different virion sizes (ranging from 30 to 300 nm), the presence or absence of an envelope, different genome lengths (ranging from 7 to 150 kb), different genome types (dsDNA, ssRNA), and different genome compositions (linear, segmented). All the viruses were provided by the virology laboratory at the university hospital of Lyon (Hospices Civils de Lyon). This mix contained the cell culture supernatant of Adenovirus 31 (AdV), respiratory syncytial virus A (RSV-A), herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1), influenza A virus, and rhinovirus. For each virus, clinical samples obtained from hospitalized patients were cultured with the appropriate cell line and media, for which the viral supernatant was then collected (Table 2).

Table 1.

List of the five selected viruses included in the mock virome and the clinical respiratory samples. The mock virome consists of known concentrations of five viruses isolated from respiratory samples, selected as representatives of a wide range of virus characteristics (virion size, the presence or absence of an envelope, genome length, genome type (dsDNA, ssRNA), and genome composition (linear, segmented)). All the viruses were provided by the virology laboratory (Hospices Civils de Lyon). Human clinical respiratory samples were obtained from hospitalized patients. dsDNA: double stranded DNA; ssRNA: single stranded RNA.

| Samples | Virus | Virus Family |

Molecular Typing | Baltimore Classification | Genome Composition | Genome Size (kb) | Virion Size (nm) | Enveloped | Ct Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adenovirus | Adenoviridae | ADV-A31 | Group I: dsDNA | Linear | 34 | 65/80 | No | 21.1 | |

| Respiratory Syncytial Virus | Paramyxoviridae | RSV-A | Group V: ssRNA (-) | Linear | 15 | 150 | Yes | 22.1 | |

| Mock Virome | Herpes Simplex Virus | Herpesviridae | HSV-1 | Group I: dsDNA | Linear | 150 | 120/300 | Yes | 26.2 |

| Influenza Virus | Orthomyxoviridae | IAV | Group V: ssRNA (-) | Segmented | 13 | 80/120 | Yes | 20.4 | |

| Rhinovirus | Picornaviridae | HRV-A13 | Group IV: ssRNA (+) | Linear | 7 | 30 | No | 29 | |

| Clinical samples | Herpes Simplex Virus | Herpesviridae | HSV-1 | Group I: dsDNA | Linear | 150 | 120/300 | Yes | 16.6 |

| Respiratory Syncytial Virus | Paramyxoviridae | RSV | Group V: ssRNA (-) | Linear | 15.2 | 150 | Yes | 19.3 |

Table 2.

Cell culture and media. The different types of cells used for culture are HEp-2 cells (human liver cancer cells, ATCC CCL-23), Vero cells (monkey kidney epithelial cells, ATCC CCL-81), MRC-5 cells (human fetal lung fibroblasts, Biowhittaker, 25-10-1995 produced by RD-Biotech (Besançon, France)), and MDCK cells (canine kidney epithelial cells, ATCC CCL-34). FBS: foetal bovine serum; HEp-2: human epithelial cell line type 2; MDCK: Madin-Darby canine kidney; MEM: minimal essential medium.

| Virus | Cells | Nature of the Sample | Culture Media | Additional Elements | Number of Days in Culture | Cryoprotectant Medium |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adenovirus | Hep | stool | MEM | 2% penicillin-streptomycin + 1% L-glutamine + 0.05% neomycin + 2% FBS + 2% Hepes Buffer | 4 | Yes |

| Respiratory Syncytial Virus | Hep | nasal throat | MEM | 2% penicillin-streptomycin + 1% L-glutamine + 0.05% neomycin + 2% FBS + 2% Hepes Buffer | 4 | Yes |

| Herpes Simplex Virus | Vero | vaginal swab | MEM199 | 2% penicillin-streptomycin | 3 | No |

| Influenza A | MDCK | bronchoalveolar lavage | MEM | 2% penicillin-streptomycin + 1% L-glutamine + 0.05% neomycin + 0.05% Trypsine + 2% Hepes Buffer | 5 | Yes |

| Rhinovirus | MRC5 | tracheobronchial aspiration | MEM | 2% penicillin-streptomycin + 1% L-glutamine + 0.05% neomycin + 2% FBS + 2% Hepes Buffer | 5 | Yes |

Using the Ct values obtained by semi-quantitative real-time PCR assays (r-gene, bioMérieux, Marcy l’Étoile, France) a mix with an identical Ct value for each virus was prepared. Individual aliquots of 250 μl were prepared in triplicate for each extraction method to evaluate (9 aliquots). Aliquots were stored at −80 °C (Figure 1).

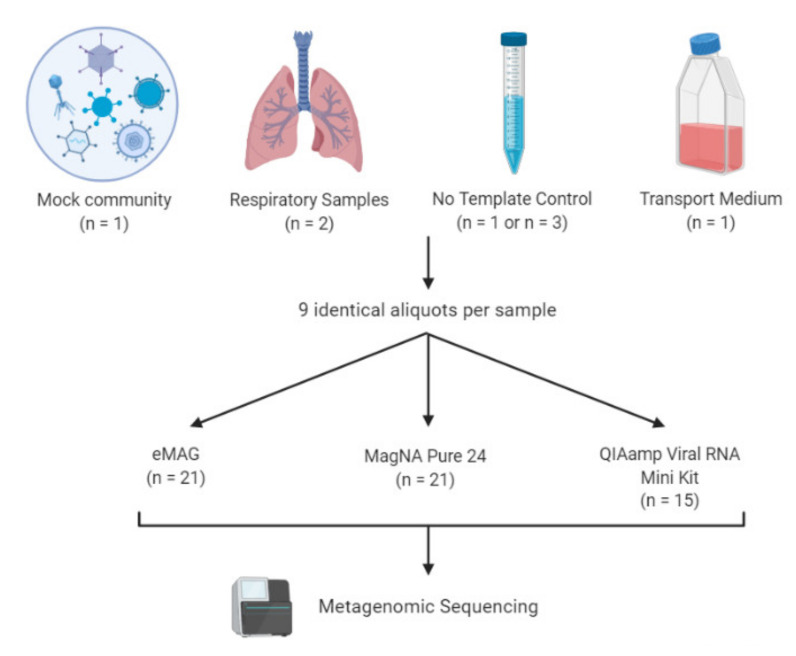

Figure 1.

Overview of the study design. A mock virome containing five viruses isolated from respiratory samples representative of a wide range of virus characteristics (adenovirus 31, respiratory syncytial virus A, herpes simplex virus 1, influenza A virus, and rhinovirus) was prepared. Human clinical samples were obtained from hospitalized patients (one bronchoalveolar lavage positive for herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1) and one nasopharyngeal aspiration positive for respiratory syncytial virus A (RSV-A). No template controls (NTCs) and transport medium samples were implemented in the process to control for sample and kitome cross-contamination. For the automatic extractors, NTCs were interspersed between the samples of each batch (n=3 per batch), whereas for the manual method only 1 NTC was included per batch (n = 1). To assess the reliability and reproducibility of the experimental results, the extractions and next generation sequencing (NGS) workflow were set up in triplicate (for the mock and respiratory samples), using the same amount of sample input. Finally, libraries were sequenced in the same run with Illumina NextSeq 500 ™ using a 2 x 150 paired-end (PE) high-output flow cell.

2.2. Sample Collection

Two additional patient samples—one positive for a DNA virus and one positive for an RNA virus—that were initially sent to our laboratory for routine viral diagnosis were also selected (Table 1). These clinical samples were a bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) positive for HSV-1 and a nasopharyngeal aspiration (NPA) positive for RSV-A. These samples were stored at +4 °C for initial diagnosis and then diluted in transport medium (MEM medium + 1% L-glutamine + 1% fetal bovine serum + 2% Hepes) in order to obtain a sufficient volume for all the tests (up to 2.3 mL). Then, 250 μL aliquots were prepared in triplicate for each extraction method to evaluate (9 replicate samples in total). The aliquots were stored at −80°C (Figure 1).

2.3. Nucleic Acid Extraction

The selection of the manual kits and the different platforms was based on their commercial and hospital availabilities. The 3 different methods chosen were the NucliSENS eMAG platform (bioMérieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France), the magNA Pure 24 platform (Roche, Basel, Switzerland), and the QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany)—all methods widely used in diagnostic laboratories. Frozen samples were thawed and homogenized by vortexing. Nucleic acids were extracted in parallel from 220 μL of the aliquot in triplicate for each kit, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For the NucliSENS eMAG platform, specific protocol B 2.0.1 was selected. For the MP24 platform, protocol pathogen 1000 was selected. In addition, in order to evaluate the cross-contamination during automated extractions, no-template controls (NTC) were regularly interspersed between samples (i.e., 7 samples per series) (Figure 2). The QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit was used following the manufacturer’s recommendation with the addition of an inert Linear Acrylamide (LA) carrier (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) to ensure the maximum recovery of nucleic acids. To assess the reproducibility of the experimental results, the extraction and NGS analysis were set up in triplicate (for mock and respiratory samples) using the same amount of sample input.

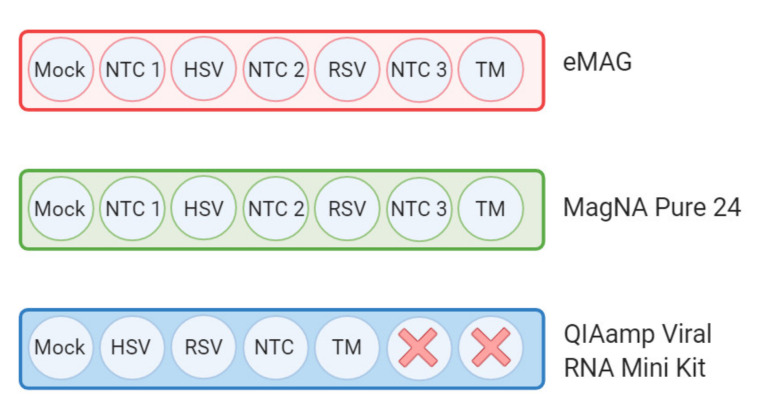

Figure 2.

Arrangement of the samples on the extraction platforms. The three different extraction methods used here were the NucliSENS eMAG platform (bioMérieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France), MagNA Pure 24 platform (Roche, Basel, Switzerland), and manual QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Nucleic acids were extracted in triplicate from the same aliquot for each kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In order to evaluate cross-contamination during the automated extractions, an NTC was regularly interspersed between samples (7 samples per series). To evaluate the kitome contamination, a transport medium sample was added in addition to NTC. Here, each color represents a different extraction method. NTC: No Template Control; HSV: Herpes Simplex Virus; RSV: Respiratory Syncytial Virus; TM: Transport Medium.

2.4. Metagenomic Workflow

As previously described, we used an mNGS protocol optimized in our lab [43]. Briefly, after thawing all the samples were supplemented with MS2 bacteriophage (Levivirus genus) from a commercial kit (MS2, IC1 RNA internal control; r-gene, bioMérieux) to check the validity of the process. Only the RNA internal control MS2 was added because it validates all the steps of our protocol (including RT stage during amplification) in contrast to a DNA internal control. A no-template control (NTC) consisting of RNase free water was implemented to evaluate the contamination during the process. An additional negative control consisting of viral transport medium was added. For sample viral enrichment, a 3-step method was applied to 220 μL of vortexed sample spiked with MS2 (low-speed centrifugation, followed by the filtration of the supernatant and then Turbo DNase treatment), as described in detail in Bal et al. [43]. After viral enrichment, the total nucleic acids were extracted using one of the three methods selected for the study described above. After random nucleic acid amplification using modified whole transcriptome amplification (WTA2, Sigma-Aldrich, Darmstadt, Germany), libraries were prepared using the Nextera XT DNA Library kit and sequenced with Illumina NextSeq 500 ™ using a 2 x 150 PE high-output flow cell (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA).

2.5. Bioinformatic Analysis

High-quality reads were filtered using trimmomatic PE and were further analysed using Kraken 2, followed by Braken for a taxonomic abundance estimation [44]. A custom kraken 2 database made up of (1) human, bacteria, fungi, archaea, and plasmid genome sequences given by kraken 2 and (2) an in-house viral genome database was used (viromedb, personal communication). The viromedb consists of complete viral genome sequences extracted from genbank and refseq subjected to vecscreen and seqclean softwares to remove the vectors and adaptor sequences and dustmasker to remove the low-complexity sequences.

2.6. Statistical Analyses

To compare the sensitivity of the three extraction methods, the mean proportion of total viral reads and specific viral abundance were determined. Kitome and sample cross-contamination were assessed by normalizing reads in reads per million (RPM), mapping the reads, and transforming them in log10 (RPM). For the kitome assessment, a sample was considered to be positive for a particular virus when the log10 (RPM) of this virus exceeded 1. Analyses were performed at the genus taxonomy level, except for the kitome, for which analyses were performed at the family taxonomy level. All the plots were constructed via ggplot2 and statistical analyses were performed with Rstatix using R (version 3.6.1). For all the statistical tests, the Student’s t-test was used.

2.7. Data Availability

The raw sequence data were deposited at SRA (PRJNA665071).

2.8. Ethics

Respiratory samples were collected for regular disease management during hospital stay and no additional samples were taken for this study. In accordance with the French legislation relating to this type a study, written informed consent from participants was not required for the use of de-identified collected clinical samples (bioethics law number 2004-800 of August 6, 2004). During their hospitalization in the Hospice Civils de Lyon (HCL), patients were made aware that their de-identified data including clinical samples may be used for research purposes, and they could opt out if they objected to the use of their data.

3. Results

Three different extraction methods were evaluated: two automated extraction platforms (eMAG and MP24) and a manual extraction kit (QIAamp) (Figure 1).

3.1. Sensitivity for the Detection of the Targeted Viruses

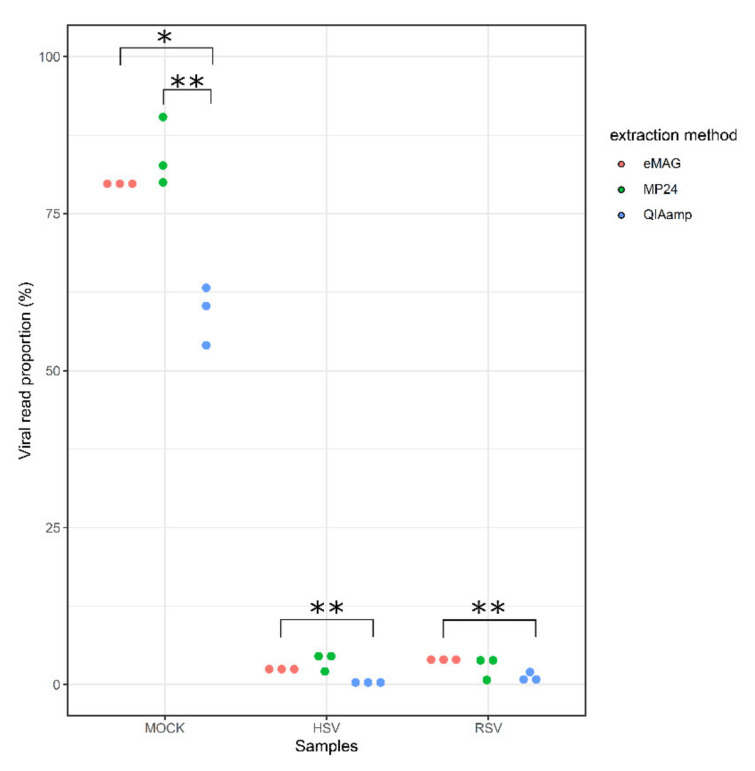

To evaluate the sensitivity of each method, the mean proportion of viral reads out of the total reads generated was first compared (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Distribution of the viral read proportion (%) according to the three extraction methods. QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit (QIAamp, blue dots), MagNA Pure 24 (MP24, green dots), and eMAG (eMAG, red dots) extraction methods for mock and clinical samples (HSV and RSV). HSV: herpes simplex virus; RSV: respiratory syncytial virus. The average of viral read proportions was compared two by two using a Student’s t test (*p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01).

For the mock sample, both eMAG and MP24 yielded significantly higher proportions of viral reads (79.9% and 84.5%, respectively) in comparison with QIAamp (59.4%; p < 0.05 and p < 0.01, respectively). For the HSV-positive BAL, eMAG yielded a higher proportion of viral reads (2.6%) compared with QIAamp (0.5%, p < 0.01), but did not significantly differ with the MP24 (3.9% viral reads). For the RSV-positive NPA, a similar trend was observed, with an average of 4.3%, 3%, and 1.4% viral reads for eMAG, MP24, and QIAamp, respectively.

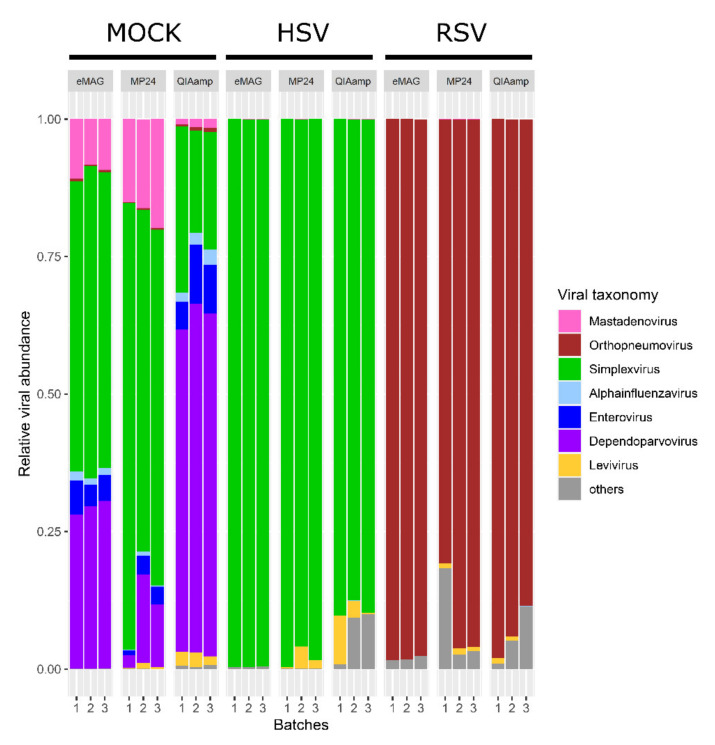

To determine potential bias in the detection of DNA or RNA viruses, the relative abundance of Levivirus (Internal Quality Control) and targeted viruses in each triplicate were then compared (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Taxonomic distribution (relative abundance) of triplicates for mock and clinical samples according to the three extraction methods. The relative distribution is described at the genus taxonomic level. Only major viral sequences are illustrated with different colours. HSV: herpes simplex virus; RSV: respiratory syncytial virus.

Levivirus was detected in all samples for MP24 and QIAamp, and in 8/9 samples for eMAG. For the targeted viruses, all the viruses were detected with all the extraction methods (Figure 4).

For the mock sample, a difference in the relative abundance of both the RNA and DNA viruses was noted when comparing the extraction methods.

The highest relative abundance of RNA viruses was observed using the QIAamp method (8.2% Enterovirus, 2.2% Alphainfluenzavirus, and 0.6% Orthopneumovirus), which was not significantly different from that of eMAG (5% Enterovirus, 1.4% Alphainfluenzavirus, and 0.4% Orthopneumovirus). The lowest relative abundance was obtained with MP24 (2.5% Enterovirus, 0.4% Alphainfluenzavirus, and 0.2% Orthopneumovirus; p < 0.05 only for Alphainfluenzavirus and Orthopneumovirus compared to the QIAamp method).

For DNA viruses, the highest relative abundance was obtained using eMAG and MP24 (54.4% and 69.3% for Simplexvirus, respectively, vs. 23.4% with QIAamp; 9.5% and 17.1% for Adenovirus, respectively, vs. 1.3% with QIAamp; p < 0.01).

Surprisingly, many reads associated with Dependoparvovirus, an ssDNA virus, were observed in the mock sample after the QIAamp extraction (29.4% with eMAG, 9.9% with MP24, and 61.4% with the QIAamp extraction).

3.2. Sample Cross-Contamination

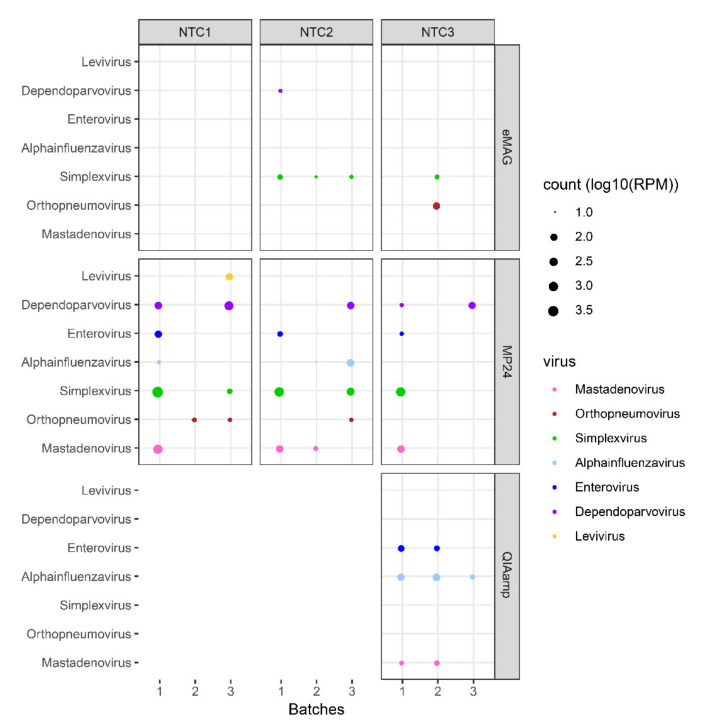

The impact of the different extraction methods on sample cross-contamination was then evaluated from the NTC samples included between each sample during the extractions (Figure 2) by mapping the read count of viruses that were present in samples from the same batch: internal quality control (MS2, Levivirus) and targeted viruses (Adenovirus, Orthopneumovirus, Simplexvirus, Alphainfluenzavirus, Enterovirus, and Dependoparvovirus) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Sample cross-contamination. Bubble plot showing the normalized abundance in log10(RPM) of the targeted viruses in each NTC and for the different extraction methods. During the automated extractions, NTCs were interspersed between samples (i.e., 3 NTCs per batch). For manual extraction, only one NTC was added. Analyses were performed at the genus level. Each genus is represented by coloured dots. The size of the dots represents the abundance normalized in log10(RPM) for viral reads associated with sample cross-contamination. HSV: herpes simplex virus; RSV: respiratory syncytial virus; NTC: no template control; RPM: reads per million.

Levivirus was not found in any NTC extracted by eMAG and QIAamp but was found in 1/9 NTCs extracted by MP24 (MS2 log10RPM = 2.1).

For the two automatic extractors, the main contaminant was Simplexvirus (HSV1), found in 4/9 NTCs (up to 1.5 log10(RPM)) and in 5/9 NTCs (up to 3.7 log10(RPM)) extracted with eMAG and MP24, respectively. For eMAG, there was also a high level of Dependoparvovirus contamination in 1/9 NTCs (log10(RPM) = 1.2) and of Orthopneumovirus in 1/9 NTCs (log10(RPM) = 2.1). For MP24, cross-contamination was noted in the NTC, with all viruses contained in the mock 4/9 NTCs with Mastadenovirus (up to 2.9 log10(RPM)), 5/9 NTCs with Dependoparvovirus (up to 2.8 log10(RPM)), 3/9 NTCs with Enterovirus (up to 2.1 log10(RPM)), 3/9 NTCs with Alphainfluenzavirus (up to 2.1 log10(RPM)), and 3/9 NTCs with Orthopneumovirus (up to 1.3 log10(RPM)).

For the QIAamp manual extractor, the main contaminant was Alphainfluenzavirus (3/3 NTC, up to 2.2 log10(RPM)). There were also contaminations with Mastadenovirus (2/3 NTC, up to 1.5 log10(RPM)) and with Enterovirus (2/3 NTC, up to 1.8 log10(RPM)).

Overall, the viral sample cross-contamination represented on average 0.002%, 0.107%, and 0.015% of the total reads generated from the NTC for the eMAG, MP24, and QIAamp extraction methods, respectively (corresponding to 1.53%, 36.09%, and 1.45% of the viral reads for the eMAG, MP24, and QIAamp extraction methods, respectively).

Importantly, for MP24 we also noted that sample cross-contamination was more associated with a batch effect than with the position of the sample in the extraction cartridge. Hence, while NTC#1, #2, and #3 were all contaminated, there was less contamination in all NTCs from batch #2 than in the NTCs from the two other batches of extractions (Figure 5).

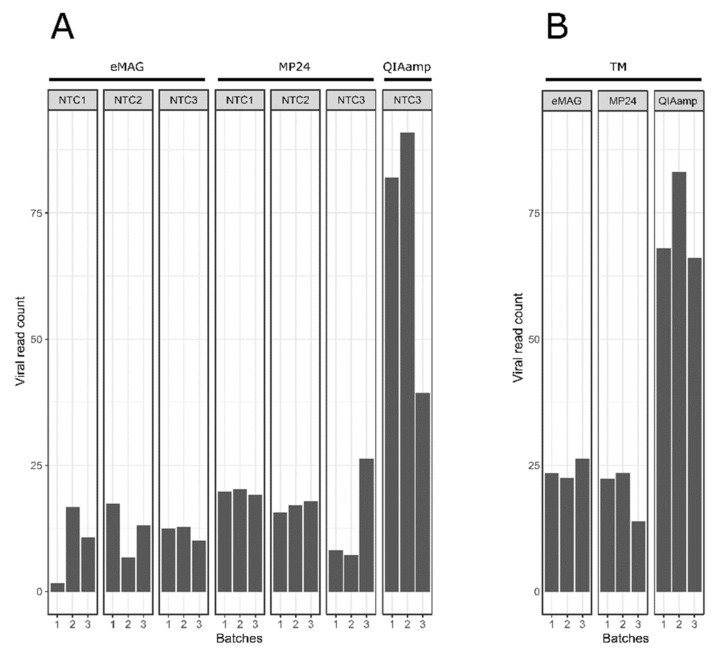

3.3. Kitome Assessment

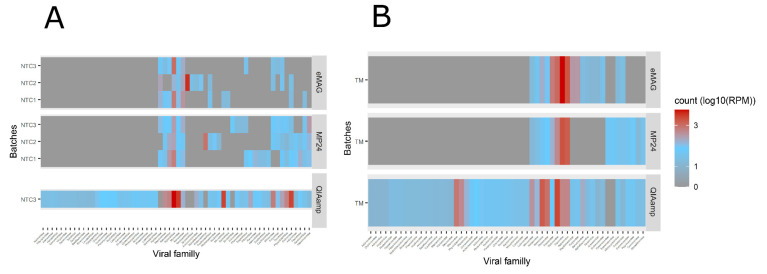

The impact of the different extraction methods on the viral kitome contamination was then evaluated by detecting in the NTC and TM the presence of reads associated with viruses other than the targeted viruses. The log10(RPM) of the kitome was significantly higher with the QIAamp extraction compared to the eMAG and MP24 extractions (p < 0.01).

The viral kitome contamination generated from the NTC represented an average of 11.31 log10(RPM), 16.88 log10(RPM), and 70.77 log10(RPM) with the eMAG, MP24, and QIAamp extraction methods, respectively (Figure 6a).

Figure 6.

Proportion of Kitome contained in each triplicate from the different extraction methods (A) in NTC and (B) in the transport medium. Bar plot showing the sum of the viral read count normalized in log10(RPM), associated with reagent contamination (i.e., reads associated with other viruses than the targeted viruses: kitome) for each NTC and TM compared between different extraction methods. During automated extractions, NTCs were interspersed between samples (i.e., 3 NTCs per batch). For manual extractions, only one NTC was added. In addition to the NTC, a transport medium was added. Analyses were performed at the family taxonomy level. A sample was considered to be positive for a particular virus when the log10(RPM) of this virus exceeded 1. HSV: herpes simplex virus; RSV: respiratory syncytial virus; NTC: no template control; TM: transport medium; RPM: reads per million.

A total of 19, 28, and 55 different viral families were detected in the NTC with the eMAG, MP24, and QIAamp methods, respectively (Figure 7a).

Figure 7.

Virus family presence contained (A) in NTC and (B) in TM (other than the target virus) in each triplicate from the different extraction methods. The heatmap showed the viral family read count associated with the kitome (the presence of reads associated with other viruses than the targeted viruses) normalized in log10(RPM) in each NTC and TM between the different extraction methods. A gradient of colors was defined from gray (no count) to blue (few counts) to red (highest counts). During the automated extractions, the NTCs were interspersed between samples (i.e., 3 NTCs per batch). For manual extraction, only one NTC was added. In addition to the NTC, transport medium was added. Analyses were performed on the family taxonomical level. A sample was considered to be positive for a particular virus when the log10(RPM) of this virus exceeded 1. HSV: herpes simplex virus; RSV: respiratory syncytial virus; NTC: no template control; TM: transport medium; RPM: reads per million.

The contaminants derived mainly from bacteriophage families. In particular, Siphoviridae was found in all three methods (ranging from 2.32 to 3.39 log10(RPM)), corresponding to 21.4%, 13.7%, and 4.8% of the total viral kitome reported with the eMAG, MP24, and QIAamp extraction methods, respectively.

Regarding the transport medium, the viral kitome contamination represented an average of 24.11 log10(RPM), 19.94 log10(RPM), and 72.45 log10(RPM) with the eMAG, MP24, and QIAamp extraction methods, respectively (Figure 6b). The same main viral families associated with kitome were found for the two automatic extractors with a majority of Poxviridae, while for the manual extractor the main family found was Siphoviridae (Figure 7b).

Overall, the kitome contamination was higher with the QIAamp extraction (p < 0.01). Siphoviridae bacteriophages were found in the three methods, while other contaminants such as Poxviridae were specifically found in the transport medium extracted by the automated methods.

4. Discussion

In this study, we compared the performance of three extraction methods commonly used in clinical laboratories for viral mNGS analysis (eMAG, MagNA Pure 24, and QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit). The extractors yielding the highest proportion of viral reads were the two automatic extractors, eMAG and MP24. A previous study found that Qiagen kits tend to extract a high proportion of human nucleic acids, which could explain the lower viral proportion reported in the present study [29].

Despite this difference, all the viruses present in the mock or clinical samples could be detected with all the methods evaluated herein. Nonetheless, a difference in the relative abundance of RNA and DNA viruses was noted in the mock sample. The highest relative abundance of RNA viruses was reported with QIAamp, and the highest relative abundance of DNA viruses was reported with the eMAG and MP24 platforms. This bias should be taken into account during the interpretation of mNGS studies and underlines the importance of the extraction method choice, depending on the virus to be explored.

These differences could be due to the various properties of viruses, including the presence of an envelope, the type of genome, or the size of the virions. Yang et al. showed a better performance of RNA virus recovery with EasyMag (identical silica extraction technology and similar performance to that of Emag [45]) compared to the MagNA Pure Compact. They explained this difference by a possible RNA degradation or by an ineffective binding of RNA to the magnetic beads [30]. Finally, the higher sensitivity of the QIAamp kit for the detection of RNA viruses might be explained by the kit having been initially intended for the extraction of RNA viruses. The detection of DNA viruses would still be possible through the capture of the RNA transcripts of DNA viruses. Meanwhile, a higher number of reads on RNA viruses for the QIAMP method was noted from the mock sample including both RNA and DNA viruses at equi-Ct; the supplementation of both DNA and RNA internal controls in NTCs would have been interesting for evaluating also the extraction bias in low-biomass samples. In addition to the differences related to the extraction methods, certain types of viruses or genomes can be preferentially amplified as described for the Poliovirus by Lewandoska et al. [23].

Moreover, bioinformatics analysis of mNGS data can also impact the viral reads annotation. The presence of gaps at the level of taxonomic classification (genus) can bias the interpretation for these given taxonomic groups (notably phages). The choice of the viral reference database is therefore crucial in order to limit viral misclassifications or the lack of detection of new emerging viruses [46]. Moreover, short reads reduce the accuracy of viral read assignation. As there is currently no gold standard in de novo assembly software for virome assessment, extensive benchmarking will be necessary in order to choose the most adapted method for future studies. With the new advances in third-generation sequencing and the improvement in sequence quality generated by this approach, we expect that the use of longer reads will led to an increase in specificity as compared to short-read technology.

Interestingly, we observed many reads associated with Dependoparvovirus only in the mock sample, especially with the QIAamp extraction. This can be explained by the presence of ADV in the mock, which might be associated with Adeno-associated dependoparvovirus [47] or with contaminants from the QIAamp column [35,48]. Our internal control (MS2, Levivirus) was detected for all replicates extracted with the three methods, except for two extracts with eMAG. As previously described, competition between the target viruses and MS2 might be observed during the process, leading to undetected MS2 [43].

To date, few studies have assessed the impact of different extraction methods on the performance of metagenomics. Klenner et al. evaluated four manual QIAamp nucleic acid extraction kits (QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit, QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit, QIAamp cador Pathogen Mini Kit, and QIAamp MinElute Virus Spin Kit) with four different viruses (including Reovirus, Orthomyxovirus, Orthopoxvirus, and Paramyxovirus), and reported that the selection of the kits has only a minor impact on the yield of viral reads and the quantity of reads obtained by NGS [28]. However, this study only evaluated manual kits from the same manufacturer and with separate RNA and DNA extraction methods.

Conversely, several studies have highlighted the importance of the nucleic acid extraction protocol in producing high-quality extracts suitable for sequencing [23,27,29]. Lewandoska et al. compared the impact of three extraction methods (QIAamp Viral RNA mini Kit, PureLink Viral RNA/DNA Mini Kit, and automated NucliSENS EasyMAG) on the recovery of different viral genomes (adenovirus, poliovirus, HHV-4, influenza A virus). The EasyMAG extraction was more efficient for both RNA and DNA viruses, leading to a higher recovery of viral genomes. The mNGS results are highly susceptible to inaccurate conclusions resulting from the sequencing of contaminants [36]. In the present study, the viral contamination was higher with MP24 than with eMAG and QIAamp. Automated extraction platforms may lead to sample cross-contamination due to the generation of aerosols or robotic errors. Knepp et al. compared two automated extractors (BioRobot M48 instrument (Qiagen, Inc.) and MagNA Pure) and did not show contamination with the automated instruments [24]. However, they only investigated cross-contamination related to enterovirus (RNA virus), unlike our study, which evaluated a panel of RNA and DNA viruses.

The second source of contamination may come from the reagents (kitome) used throughout the process or from laboratory contaminants. The extractor for which the kitome abundance was highest was the QIAamp. The main contaminants were Siphoviridae, Myoviridae, Microviridae, and Podoviridae, which is consistent with other studies that have reported similar findings with spin columns [34]. In order to monitor the kitome and avoid misinterpretation, it is important to implement negative controls at different steps of the process [38,42,49]. Here, we did not add any internal controls in the NTC in order to get the highest sensitivity in detecting the kitome (without using reads to sequence MS2). On the other hand, the internal control MS2 was added in the TMs and was detected in all except one batch of the eMAG extraction in order to estimate the potential contaminants present in the transport medium, as it was previously published that fetal bovine serum contains DNA [50,51].

Furthermore, a computational approach for removing contaminants of viral origin should be developed, as previously described for bacteriome data [34,52].

Although the results show higher sample cross-contamination with the MP24 and higher kitome-related contamination with the QIAamp, other steps throughout sample processing can produce contamination. Here, we did not include an NTC at each step of the process to control for other sources of contamination. In addition, only a few respiratory samples were tested herein, and so further studies on a larger number of respiratory samples, as well as on other types of samples (stool, blood, and tissue) or other respiratory viruses (such as the SARS-CoV-2, which has the largest human RNA virus genome), should be performed. While three commonly used extraction methods have been evaluated in this study, it could be interesting to test others.

5. Conclusions

Our findings highlight the importance of extraction method choice for viral mNGS analysis. The eMAG platform yielded a higher proportion of viral reads, with a limited impact of reagents and sample cross-contamination compared to the QIAamp and MP24 extractors.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the LABEX ECOFECT (ANR-11-LABX-0048) of Université de Lyon, within the program “Investissements d’Avenir” (ANR-11-IDEX-0007) operated by the French National Research Agency (ANR). We are grateful to Florence Morfin, who provided culture strains of the different viruses in the study. The bioinformatics analysis was performed using the computing facilities of the CC LBBE/PRABI-AMSB.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S., A.B., and L.J.; formal analysis, M.S., H.R., V.N., and L.J.; methodology, M.S.; resources, V.C. and K.B.-P.; software, H.R. and V.N.; supervision, V.N. and L.J.; writing—original draft, M.S.; writing—review and editing, M.S., A.B., G.D., G.Q., B.L., V.N., and L.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

eMAG®. The eMAG consumables and R-gene® kits necessary for this evaluation were provided by bioMerieux France. However, the data obtained during the evaluation were independently analyzed in the virology department of Lyon University Hospital, which possesses the entire final data bank. BioMerieux had no role in the study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Conflicts of Interest

Valérie Cheynet and Karen Brengel-Pesce are employees of Biomérieux. Antonin Bal has received a research grant from bioMérieux and has served as a consultant for bioMérieux. The other authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- 1.Graf E.H., Simmon K.E., Tardif K.D., Hymas W., Flygare S., Eilbeck K., Yandell M., Schlaberg R. Unbiased Detection of Respiratory Viruses by Use of RNA Sequencing-Based Metagenomics: A Systematic Comparison to a Commercial PCR Panel. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2016;54:1000–1007. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03060-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xu L., Zhu Y., Ren L., Xu B., Liu C., Xie Z., Shen K. Characterization of the nasopharyngeal viral microbiome from children with community-acquired pneumonia but negative for Luminex xTAG respiratory viral panel assay detection. J. Med. Virol. 2017;89:2098–2107. doi: 10.1002/jmv.24895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang Y., Walls S.D., Gross S.M., Schroth G.P., Jarman R.G., Hang J. Targeted Sequencing of Respiratory Viruses in Clinical Specimens for Pathogen Identification and Genome-Wide Analysis. In: Moya A., Pérez Brocal V., editors. The Human Virome. Volume 1838. Springer; New York, NY, USA: 2018. pp. 125–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cummings M.J., Tokarz R., Bakamutumaho B., Kayiwa J., Byaruhanga T., Owor N., Namagambo B., Wolf A., Mathema B., Lutwama J.J., et al. Precision Surveillance for Viral Respiratory Pathogens: Virome Capture Sequencing for the Detection and Genomic Characterization of Severe Acute Respiratory Infection in Uganda. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2019;68:1118–1125. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paskey A.C., Frey K.G., Schroth G., Gross S., Hamilton T., Bishop-Lilly K.A. Enrichment post-library preparation enhances the sensitivity of high-throughput sequencing-based detection and characterization of viruses from complex samples. BMC Genom. 2019;20:155. doi: 10.1186/s12864-019-5543-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kufner V., Plate A., Schmutz S., Braun D.L., Günthard H.F., Capaul R., Zbinden A., Mueller N.J., Trkola A., Huber M. Two Years of Viral Metagenomics in a Tertiary Diagnostics Unit: Evaluation of the First 105 Cases. Genes. 2019;10:661. doi: 10.3390/genes10090661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eibach D., Hogan B., Sarpong N., Winter D., Struck N.S., Adu-Sarkodie Y., Owusu-Dabo E., Schmidt-Chanasit J., May J., Cadar D. Viral metagenomics revealed novel betatorquevirus species in pediatric inpatients with encephalitis/meningoencephalitis from Ghana. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:2360. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-38975-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen L., Liu W., Zhang Q., Xu K., Ye G., Wu W., Sun Z., Liu F., Wu K., Zhong B., et al. RNA based mNGS approach identifies a novel human coronavirus from two individual pneumonia cases in 2019 Wuhan outbreak. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2020;9:313–319. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1725399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moore N.E., Wang J., Hewitt J., Croucher D., Williamson D.A., Paine S., Yen S., Greening G.E., Hall R.J. Metagenomic Analysis of Viruses in Feces from Unsolved Outbreaks of Gastroenteritis in Humans. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2015;53:15–21. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02029-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deng L., Silins R., Castro-Mejía J.L., Kot W., Jessen L., Thorsen J., Shah S., Stokholm J., Bisgaard H., Moineau S., et al. A Protocol for Extraction of Infective Viromes Suitable for Metagenomics Sequencing from Low Volume Fecal Samples. Viruses. 2019;11:667. doi: 10.3390/v11070667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Law J., Jovel J., Patterson J., Ford G., O’keefe S., Wang W., Meng B., Song D., Zhang Y., Tian Z., et al. Identification of Hepatotropic Viruses from Plasma Using Deep Sequencing: A Next Generation Diagnostic Tool. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e60595. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rascovan N., Duraisamy R., Desnues C. Metagenomics and the Human Virome in Asymptomatic Individuals. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2016;70:125–141. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-102215-095431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miller S., Naccache S.N., Samayoa E., Messacar K., Arevalo S., Federman S., Stryke D., Pham E., Fung B., Bolosky W.J., et al. Laboratory validation of a clinical metagenomic sequencing assay for pathogen detection in cerebrospinal fluid. Genome Res. 2019;29:831–842. doi: 10.1101/gr.238170.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilson M.R., Sample H.A., Zorn K.C., Arevalo S., Yu G., Neuhaus J., Federman S., Stryke D., Briggs B., Langelier C., et al. Clinical Metagenomic Sequencing for Diagnosis of Meningitis and Encephalitis. New Engl. J. Med. 2019;380:2327–2340. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1803396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johansson H., Bzhalava D., Ekström J., Hultin E., Dillner J., Forslund O. Metagenomic sequencing of “HPV-negative” condylomas detects novel putative HPV types. Virology. 2013;440:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2013.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kohl C., Brinkmann A., Dabrowski P.W., Radonić A., Nitsche A., Kurth A. Protocol for Metagenomic Virus Detection in Clinical Specimens. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2015;21:48–57. doi: 10.3201/eid2101.140766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lysholm F., Wetterbom A., Lindau C., Darban H., Bjerkner A., Fahlander K., Lindberg A.M., Persson B., Allander T., Andersson B. Characterization of the Viral Microbiome in Patients with Severe Lower Respiratory Tract Infections, Using Metagenomic Sequencing. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e30875. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fischer N., Indenbirken D., Meyer T., Lütgehetmann M., Lellek H., Spohn M., Aepfelbacher M., Alawi M., Grundhoff A. Evaluation of Unbiased Next-Generation Sequencing of RNA (RNA-seq) as a Diagnostic Method in Influenza Virus-Positive Respiratory Samples. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2015;53:2238–2250. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02495-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takeuchi S., Kawada J., Horiba K., Okuno Y., Okumura T., Suzuki T., Torii Y., Kawabe S., Wada S., Ikeyama T., et al. Metagenomic analysis using next-generation sequencing of pathogens in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from pediatric patients with respiratory failure. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:1209. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-49372-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li Y., Fu X., Ma J., Zhang J., Hu Y., Dong W., Wan Z., Li Q., Kuang Y.-Q., Lan K., et al. Altered respiratory virome and serum cytokine profile associated with recurrent respiratory tract infections in children. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:2288. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10294-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van den Munckhof E.H.A., de Koning M.N.C., Quint W.G.V., van Doorn L.-J., Leverstein-van Hall M.A. Evaluation of a stepwise approach using microbiota analysis, species-specific qPCRs and culture for the diagnosis of lower respiratory tract infections. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2019;38:747–754. doi: 10.1007/s10096-019-03511-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simner P.J., Miller S., Carroll K.C. Understanding the Promises and Hurdles of Metagenomic Next-Generation Sequencing as a Diagnostic Tool for Infectious Diseases. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2018;66:778–788. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lewandowska D.W., Zagordi O., Geissberger F.-D., Kufner V., Schmutz S., Böni J., Metzner K.J., Trkola A., Huber M. Optimization and validation of sample preparation for metagenomic sequencing of viruses in clinical samples. Microbiome. 2017;5:94. doi: 10.1186/s40168-017-0317-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Knepp J.H., Geahr M.A., Forman M.S., Valsamakis A. Comparison of Automated and Manual Nucleic Acid Extraction Methods for Detection of Enterovirus RNA. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2003;41:3532–3536. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.8.3532-3536.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller S., Seet H., Khan Y., Wright C., Nadarajah R. Comparison of QIAGEN Automated Nucleic Acid Extraction Methods for CMV Quantitative PCR Testing. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2010;133:558–563. doi: 10.1309/AJCPE5VZL1ONZHFJ. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Verheyen J., Kaiser R., Bozic M., Timmen-Wego M., Maier B.K., Kessler H.H. Extraction of viral nucleic acids: Comparison of five automated nucleic acid extraction platforms. J. Clin. Virol. 2012;54:255–259. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2012.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lewandowski K., Bell A., Miles R., Carne S., Wooldridge D., Manso C., Hennessy N., Bailey D., Pullan S.T., Gharbia S., et al. The Effect of Nucleic Acid Extraction Platforms and Sample Storage on the Integrity of Viral RNA for Use in Whole Genome Sequencing. J. Mol. Diagn. 2017;19:303–312. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2016.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klenner J., Kohl C., Dabrowski P.W., Nitsche A. Comparing Viral Metagenomic Extraction Methods. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2017:59–70. doi: 10.21775/cimb.024.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang D., Lou X., Yan H., Pan J., Mao H., Tang H., Shu Y., Zhao Y., Liu L., Li J., et al. Metagenomic analysis of viral nucleic acid extraction methods in respiratory clinical samples. BMC Genom. 2018;19:773. doi: 10.1186/s12864-018-5152-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang J., Yang F., Ren L., Xiong Z., Wu Z., Dong J., Sun L., Zhang T., Hu Y., Duet J., et al. Unbiased Parallel Detection of Viral Pathogens in Clinical Samples by Use of a Metagenomic Approach. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2011;49:3463–3469. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00273-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Angebault C., Payen M., Woerther P.-L., Rodriguez C., Botterel F. Combined bacterial and fungal targeted amplicon sequencing of respiratory samples: Does the DNA extraction method matter? PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0232215. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0232215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sui H., Weil A.A., Nuwagira E., Qadri F., Ryan E.T., Mezzari M.P., Phipatanakul W., Lai P.S. Impact of DNA Extraction Method on Variation in Human and Built Environment Microbial Community and Functional Profiles Assessed by Shotgun Metagenomics Sequencing. Front. Microbiol. 2020;11:953. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.00953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thoendel M., Jeraldo P., Greenwood-Quaintance K.E., Yao J., Chia N., Hanssen A.D., Abdel M.P., Patel R. Impact of Contaminating DNA in Whole-Genome Amplification Kits Used for Metagenomic Shotgun Sequencing for Infection Diagnosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2017;55:1789–1801. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02402-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Drengenes C., Wiker H.G., Kalananthan T., Nordeide E., Eagan T.M.L., Nielsen R. Laboratory contamination in airway microbiome studies. BMC Microbiol. 2019;19:187. doi: 10.1186/s12866-019-1560-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Naccache S.N., Greninger A.L., Lee D., Coffey L.L., Phan T., Rein-Weston A., Aronsohn A., Hackett Jr J., Delwart E.L., Chiu C.Y. The Perils of Pathogen Discovery: Origin of a Novel Parvovirus-Like Hybrid Genome Traced to Nucleic Acid Extraction Spin Columns. J. Virol. 2013;87:11966–11977. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02323-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kjartansdóttir K.R., Friis-Nielsen J., Asplund M., Mollerup S., Mourier T., Jensen R.H., Hansen T.A., Rey-Iglesia A., Richter S.R., Alquezar-Planas D.E., et al. Traces of ATCV-1 associated with laboratory component contamination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:E925–E926. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1423756112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stinson L.F., Keelan J.A., Payne M.S. Identification and removal of contaminating microbial DNA from PCR reagents: Impact on low-biomass microbiome analyses. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2019;68:2–8. doi: 10.1111/lam.13091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miller R.R., Uyaguari-Diaz M., McCabe M.N., Montoya V., Gardy J.L., Parker S., Steiner T., Hsiao W., Nesbitt M.J., Tang P., et al. Metagenomic Investigation of Plasma in Individuals with ME/CFS Highlights the Importance of Technical Controls to Elucidate Contamination and Batch Effects. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0165691. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0165691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gargis A.S., Kalman L., Lubin I.M. Assuring the Quality of Next-Generation Sequencing in Clinical Microbiology and Public Health Laboratories. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2016;54:2857–2865. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00949-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schlaberg R., Queen K., Simmon K., Tardif K., Stockmann C., Flygare S., Kennedy B., Voelkerding K., Bramley A., Zhang J., et al. Viral Pathogen Detection by Metagenomics and Pan-Viral Group Polymerase Chain Reaction in Children With Pneumonia Lacking Identifiable Etiology. J. Infect. Dis. 2017;215:1407–1415. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li L., Deng X., Mee E.T., Collot-Teixeira S., Anderson R., Schepelmann S., Minor P.D., Delwart E. Comparing viral metagenomics methods using a highly multiplexed human viral pathogens reagent. J. Virol. Methods. 2015;213:139–146. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2014.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Asplund M., Kjartansdóttir K.R., Mollerup S., Vinner L., Fridholm H., Herrera J.A.R., Friis-Nielsen J., Hansen T.A., Jensen R.H., Nielsen I.B., et al. Contaminating viral sequences in high-throughput sequencing viromics: A linkage study of 700 sequencing libraries. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2019;25:1277–1285. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2019.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bal A., Pichon M., Picard C., Casalegno J.S., Valette M., Schuffenecker I., Billard L., Vallet S., Vilchez G., Cheynet V., et al. Quality control implementation for universal characterization of DNA and RNA viruses in clinical respiratory samples using single metagenomic next-generation sequencing workflow. Bmc Infect. Dis. 2018;18:537. doi: 10.1186/s12879-018-3446-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bolger A.M., Lohse M., Usadel B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Garcia M., Chessa C., Bourgoin A., Giraudeau G., Plouzeau C., Agius G., Lévêque N., Beby-Defaux A. Comparison of eMAGTM versus NucliSENS® EasyMAG® performance on clinical specimens. J. Clin. Virol. 2017;88:52–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2017.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Plyusnin I., Kant R., Jääskeläinen A.J., Sironen T., Holm L., Vapalahti O., Smura T. Novel NGS Pipeline for Virus Discovery from a Wide Spectrum of Hosts and Sample Types. Bioinformatics. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.05.07.082107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rose J.A., Hoggan M.D., Shatkin A.J. Nucleic acid from an adeno-associated virus: Chemical and physical studies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1966;56:86–92. doi: 10.1073/pnas.56.1.86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Conceição-Neto N., Zeller M., Lefrère H., De Bruyn P., Beller L., Deboutte W., Kwe Yinda K., Lavigne R., Maes P., Van Ranst M., et al. Modular approach to customise sample preparation procedures for viral metagenomics: A reproducible protocol for virome analysis. Sci. Rep. 2015:5. doi: 10.1038/srep16532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Holmes E.C. Reagent contamination in viromics: All that glitters is not gold. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2019;25:1167–1168. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2019.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gagnieur L., Cheval J., Gratigny M., Hébert C., Muth E., Dumarest M., Eloit M. Unbiased analysis by high throughput sequencing of the viral diversity in fetal bovine serum and trypsin used in cell culture. Biologicals. 2014;42:145–152. doi: 10.1016/j.biologicals.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sadeghi M., Kapusinszky B., Yugo D.M., Phan T.G., Deng X., Kanevsky I., Opriessnig T., Woolums A.R., Hurley D.J., Meng X.-J., et al. Virome of US bovine calf serum. Biologicals. 2017;46:64–67. doi: 10.1016/j.biologicals.2016.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Davis N.M., Proctor D.M., Holmes S.P., Relman D.A., Callahan B.J. Simple statistical identification and removal of contaminant sequences in marker-gene and metagenomics data. Microbiome. 2018;6:226. doi: 10.1186/s40168-018-0605-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]