Abstract

Smokeless tobacco (SLT) use is widespread across many nations and populations, and India shares more than three-quarters of the global burden of SLT consumption. Tobacco use in India has been largely viewed as a male-dominant behaviour. However, evidence from medical, social and behavioural sciences show significant SLT use among women and young girls. This paper highlights key dimensions of SLT use among women in India including prevalence and determinants, the health effects arising from SLT use and cessation behaviours. The paper concludes by providing recommendations with the aim of setting research priorities and policy agenda to achieve a tobacco-free society. The focus on women and girls is essential to achieve the national targets for tobacco control under the National Health Policy, 2017, and Sustainable Development Goals 3 of ensuring healthy lives and promote well-being for all.

Keywords: India, public health, smokeless tobacco, tobacco control, women

Introduction

Smokeless tobacco (SLT) is defined as a product that contains tobacco, is not smoked or burned at the time of use, and commonly consumed orally or nasally. These products can be placed in the mouth, cheek or the lip and are sucked or chewed1. These are often used for gargling, and also as dentifrice2. The widespread use of SLT dates back to the early 16th century due to its perceived properties of increasing salivation, reducing thirst and appetite, serving medicinal purposes and even reducing dependence on smoked tobacco3. Due to these properties, there has been a surge in its use across the nations, however, concrete evidence on its harm reduction has not been substantial4,5. Further, the carcinogenic nature of SLT products and the accompanying risk of being addicted to similar products warrant regulation and development of de-addiction strategies. The proliferation of various types of SLT products across regions, countries and tribes has ingrained practices of SLT use in cultural identities6. Thus, it remains challenging to develop data on health effects7 and regulate the product.

Tobacco use or abuse of any type in India has been largely viewed as a male-dominant behaviour. This paper highlights some of the key dimensions of SLT use among women in India with the aim of setting research priorities and policy agenda to achieve tobacco-free society.

Prevalence of SLT use

Despite the evidence of its harms and consequences, there is a high prevalence of SLT use in many populations across the globe; however, low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) share the largest burden8,9,10. According to the Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS), some of the countries with a high prevalence of SLT use include India, Bangladesh, Egypt, Nigeria and the Philippines. However, among the global 248 million SLT users, 232 million belong to India and Bangladesh alone, wherein India alone carries more than 83 per cent of the global burden11. Evidence demonstrates that increasing use of SLT has not just been reported among adult males, but also among children, teenagers, women of reproductive age and immigrants of South Asia wherever they have migrated and settled6.

SLT use among women

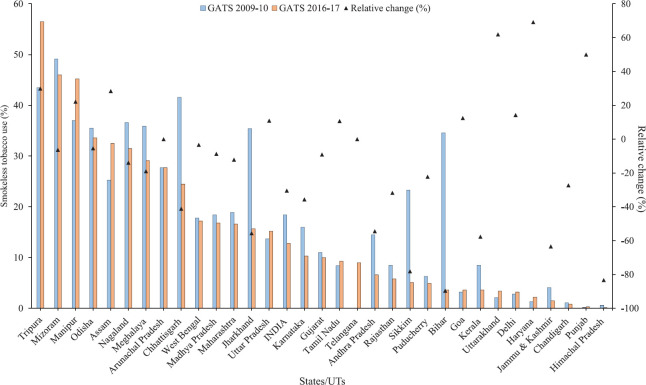

In India, according to the latest GATS survey (2016-2017)12, 12.8 per cent women aged 15 yr and above were consuming any form of SLT. In absolute numbers, this corresponds to nearly 58.2 million women consuming any form of SLT in India. The SLT use among women was over 10 per cent in 16 States of India (Fig. 1). Although SLT use has declined from 18.4 per cent (GATS 2009-2010)13 to 12.8 per cent (GATS 2016-2017)12 among women, a relative increase in SLT use was evident in nine States of India. Nearly, 17 per cent of women in India initiated SLT use before the age of 15, much higher than men (11%)12. Among the various SLT product types, women in India consume betel quid with tobacco (4.5%), oral tobacco (4.3%) and khaini (4.2%), followed by gutka (2.7%) predominantly12.

Fig. 1.

Trends in smokeless tobacco use among women aged 15 yr and above (in %), GATS, Global Adult Tobacco Survey. Source: Refs. 12,13.

SLT use among pregnant and lactating women

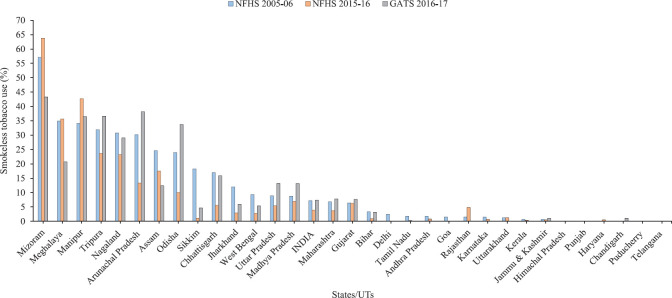

The use of SLT among pregnant women and exposure of foetuses to chemicals and hazards present in SLT products, is leading to many preventable morbidities and adverse outcomes14. The pooled prevalence of current SLT users among pregnant women was found to be lowest in Europe [0.1%, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.0-0.3] and highest in Southeast Asia (2.6%, 0.0-7.6)15. Though a slight decline has been reported from 7.17 per cent to 3.95 per cent in the rates of SLT use in pregnant women in the decade since the third round of the National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3) (2005-2006)16 to NFHS-4 (2015-2016)17, the two nationally representative surveys (NFHS 2015-2016 and GATS 2016-2017)12,17 have revealed that nearly 4.0 and 7.4 per cent women, respectively consuming any form of SLT were pregnant (Fig. 2 and Table). Moreover, the NFHS-4 (2015-2016)17 further suggests that nearly 5.0 per cent of lactating women in India consume SLT, which may directly harm neonatal health and nutrition. Both surveys also revealed substantial regional variations in SLT use among pregnant and lactating women. Among SLT product types, gutka and paan with tobacco were mostly consumed by both pregnant and lactating women (Table).

Fig. 2.

Use of any type of smokeless tobacco among currently pregnant women aged 15-49 yr in India. Source: Refs 12,16,17.

Table.

Use of smokeless tobacco (SLT) among pregnant and lactating women aged 15-49 yr in India, National Family Health Survey, 2015-2016

| States/UTs | Pregnant women 15-49 yr | Lactating women 15-49 yr | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gutka | Paan with tobacco | Khaini | Any SLT | n | Gutka | Paan with tobacco | Khaini | Any SLT | n | |

| India | 1.85 | 1.07 | 0.91 | 3.95 | 32428 | 2.2 | 1.5 | 1.3 | 5.0 | 114922 |

| North | ||||||||||

| Jammu & Kashmir | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.32 | 0.47 | 1071 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 3599 |

| Himachal Pradesh | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 319 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1052 |

| Punjab | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 734 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2182 |

| Uttarakhand | 0.75 | 0.68 | 0.34 | 1.26 | 680 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 1.1 | 2664 |

| Haryana | 0.09 | 0.14 | 0.17 | 0.48 | 1213 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 3420 |

| Delhi | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 196 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.7 | 638 |

| Central | ||||||||||

| Rajasthan | 3.87 | 0.16 | 0.54 | 4.82 | 2064 | 4.4 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 5.3 | 6942 |

| Uttar Pradesh | 3.73 | 0.93 | 0.95 | 5.39 | 5580 | 4.5 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 6.4 | 17064 |

| Chhattisgarh | 1.32 | 0.04 | 2.76 | 5.63 | 1157 | 1.4 | 0.5 | 2.3 | 5.6 | 4924 |

| Madhya Pradesh | 4.34 | 0.90 | 1.67 | 6.99 | 3089 | 5.4 | 1.0 | 2.1 | 8.9 | 10536 |

| East | ||||||||||

| West Bengal | 0.41 | 0.37 | 1.56 | 2.74 | 660 | 0.9 | 1.6 | 1.4 | 4.5 | 3301 |

| Jharkhand | 0.16 | 0.00 | 2.80 | 2.96 | 1319 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 3.5 | 3.7 | 6356 |

| Odisha | 4.68 | 2.02 | 5.01 | 10.05 | 1181 | 3.8 | 4.0 | 6.1 | 11.8 | 6438 |

| Bihar | 0.41 | 0.20 | 0.44 | 0.95 | 3364 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 1.1 | 11112 |

| Northeast | ||||||||||

| Sikkim | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.10 | 1.10 | 162 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 2.8 | 3.2 | 540 |

| Arunachal Pradesh | 4.89 | 5.48 | 3.68 | 13.33 | 743 | 5.2 | 6.6 | 3.2 | 13.5 | 2167 |

| Nagaland | 10.22 | 12.41 | 2.31 | 23.19 | 494 | 12.1 | 9.6 | 3.8 | 23.7 | 1444 |

| Manipur | 4.55 | 35.22 | 7.75 | 42.68 | 688 | 4.3 | 44.9 | 7.9 | 51.2 | 3100 |

| Mizoram | 16.86 | 28.94 | 16.99 | 63.75 | 513 | 11.7 | 25.5 | 13.6 | 56.4 | 1905 |

| Tripura | 17.19 | 6.44 | 0.51 | 23.62 | 167 | 20.1 | 11.6 | 0.7 | 29.7 | 854 |

| Meghalaya | 2.04 | 31.09 | 4.68 | 35.66 | 669 | 2.1 | 30.2 | 5.3 | 35.0 | 1909 |

| Assam | 2.76 | 14.03 | 3.00 | 17.48 | 1121 | 2.7 | 13.3 | 3.1 | 16.7 | 5974 |

| West | ||||||||||

| Gujarat | 4.82 | 0.52 | 0.32 | 6.28 | 880 | 6.0 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 7.6 | 3100 |

| Maharashtra | 0.27 | 1.34 | 0.06 | 3.70 | 1146 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 3.6 | 3758 |

| Goa | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 35 | 1.2 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 2.2 | 172 |

| South | ||||||||||

| Andhra Pradesh | 0.00 | 0.54 | 0.00 | 0.81 | 347 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.7 | 1189 |

| Karnataka | 0.03 | 0.68 | 0.00 | 0.71 | 956 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.8 | 2869 |

| Kerala | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.41 | 383 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.7 | 1147 |

| Tamil Nadu | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.29 | 914 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 2346 |

| Telangana | NA | NA | NA | NA | 254 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.8 | 1030 |

Determinants of SLT use

SLT use among women has been inversely associated with increasing levels of education, wealth and knowledge about the health effects18. It increases linearly with rise in age19,20, more prevalent in rural women21 and also depends on taxation policies22. SLT use is found to be positively associated with its use by partner or peers23,24. In a study conducted among married women at Mumbai, India, SLT use was found to be attributed for reducing stress, providing pleasure, associated companionship with peers at workplace and in the neighbourhood, increasing energy for workload and suppressing hunger when dietary requirements were not met25. Further, SLT use is often initiated at an early age as children and youth are often exposed to it when involved in purchase activities for their mothers and other older family members26. Often, individuals initiate use due to the lesser perceived harm on health from SLT use as compared to other methods of tobacco consumption such as smoking cigarettes and bidis27. Initiation of tobacco use in women often occurs during pregnancy28 as beliefs are often held by peers, family members and other individuals that tobacco can provide positive health effects and relief from common ailments and distress during pregnancy such as nausea, vomiting and constipation29,30.

Adverse health effects of SLT use among women

Among women, SLT has been associated with the risk of oral31 and pharyngeal cancers32, cancer of the gums and buccal mucosa32, oesophageal cancer33, upper aero-digestive tract cancer (UADT)34, cervical cancer34, ischaemic heart disease (IHD)34 and osteoporosis35. A meta-analysis revealed higher risk for oral cancer among female SLT users with an odds ratio (OR) of 5.83 (95% CI: 2.93-11.58), as compared to 2.72 (1.73-4.27) for males and 3.35 (2.34-4.78) for combined sex36. In another study, the difference in mortality and cancer estimates among men and women for all causes (1.21 vs. 1.38), all cancers (1.42 vs. 1.62), UADT cancer (2.16 vs. 2.95) and IHD (0.97 vs. 1.13) showed higher risks for women as compared to men34.

SLT use and reproductive morbidities

The adverse health effects of SLT on pregnant women and neonatal health are numerous37. Compounds in SLT products such as nicotine can cross the placental barrier and act as neuroteratogens38 affecting the development of the brain, lungs and the central nervous system of the foetus39. Infertility, degenerative placental changes40, increased placental weight41, pregnancy complications42, pre-term delivery43, low-birth weight43, increased stillbirth risk44 and risk of cancers in the developing foetus39 are some of the adverse health effects of SLT use during pregnancy.

SLT use and nutrition

Use of SLT has been associated with low body mass index, and this association is found to be stronger among women (OR=2.19; 95% CI: 1.90-3.41) as compared to men (OR=1.83; 95% CI: 1.67-2.00)45. Tobacco use and poor nutrition may impair immunity46 and may lead to infections and poor reproductive outcomes. Because maternal micronutrient intake is an essential factor for optimum foetal growth47, the effect of toxins in SLT on depletion of antioxidant micronutrients may lead to poor nutritional outcomes in both the mother and the foetus45. Further, among pregnant women, mean haemoglobin levels have been observed to be lower in SLT users compared to those women who do not use SLT. This may lead to severe anaemia and affect the health of the foetus and may have long-lasting impacts on the health of the mother48.

Intention to quit, quitting attempts and cessation

In India, only about 5.8 per cent of adults have successfully quit SLT use12. The percentage of female users who attempted to quit SLT products (28.4%) was lower than the male users (35.2%). Moreover, when compared to men (33.3%), a lesser percentage of women (28.6%) were advised by healthcare providers to quit SLT use12. More than 50 per cent (54.4%) women SLT users were not interested in quitting, while the corresponding percentage was 45.1 per cent among men. Among all these women who attempted to quit SLT use in the year preceding the GATS survey, only 2.7 per cent sought pharmacotherapy and 8.4 per cent underwent counselling at local cessation centres or through telephone Quitline/helpline12. While only 4.3 per cent of the women opted for traditional methods to enable cessation, 71.6 per cent attempted cessation without any assistance12. This indicates an intrinsic issue with respect to access and willingness to enrol in cessation programmes or quitting practices as these centres often receive low number of female SLT users and participants. Low support for cessation, associated stigma and low access to cessation methods are some of the factors that may act as barriers to cessation among both men and women49. There is limited research on intention to quit and barriers to cessation among women that need to be understood to facilitate quitting and awareness.

Marketing, promotion and regulation

As most countries have smoke-free policies, tobacco companies attempt to market SLT products using means to circumvent these policies50. Aggressive selling strategies such as availability of SLT as single pouches have also increased its use in many LMICs, including India51. Various decision-making bodies have implemented policies aimed at reducing the sale and purchase of SLT products. In 2004, India ratified the WHO-Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO-FCTC), which is a global instrument aimed at preventing and reducing tobacco use52. The legislative action for tobacco control in India started in 2003, when Cigarettes and Other Tobacco Products (prohibition of advertisement and regulation of trade and commerce, production, supply and distribution) Act (COTPA), 2003 prohibited any kind of tobacco advertising on all media platforms. COTPA also banned the sale of tobacco products to minors, and applied a ban on the sale of tobacco products within 100 yards of educational institutions and mandatory public health warnings and pictorial depiction of health hazards on packaging53.

In 2007-2008, the National Tobacco Control Programme (NTCP) was launched54 to generate awareness about the harmful effects of tobacco, reduce production and supply, ensure effective implementation of COTPA, enable cessation and facilitate implementation of tobacco control strategies as envisaged under the WHO-FCTC. Although initially focused on cigarette smoking, regulation of SLT products has also increased in recent years. Legal decisions aided by the advocacy measures by civil society and non-governmental organizations have allowed to regulate and control the use of tobacco55,56,57,58,59. Despite all these measures to restrict the promotion of any form of tobacco products as well as dissemination of knowledge and awareness of adverse impact of tobacco use, nearly 45.3 per cent of women SLT users did not notice health-related warnings on SLT products, much higher than the male counterparts (21.5%)12.

Despite the presence of strong political will and favourable legal instruments, gender-based policies and women-centric actions are insignificant and the implementation of the NTCP by many States is not promising. Hence, educational and community-based health interventions are of paramount importance, especially for women and girls60.

Conclusion

According to The Oxford Medical Companion, tobacco is the only legalized product which, even when used in moderation and exactly as the manufacturer intended, causes harm to the consumer61. Tobacco products such as SLT that are often sold and produced locally, are being consumed by 248 million individuals globally with 206 million users (83.06%) from India11. Women, especially, pregnant and lactating, remain to be a neglected group in terms of understanding SLT use linkages and cessation strategies. Hence, it is essential to articulate the rights of women as human rights and engage in the development of gender-sensitive tobacco research62. This focus on women and girls is essential to achieve the national targets for tobacco control under the National Health Policy, 201763, and Sustainable Development Goals 3 of ensuring healthy lives and promote well-being for all64.

Recommendations

Robust data collection and dissemination

For enabling gender-sensitive tobacco cessation initiatives, surveillance and monitoring of data on SLT use need to be disaggregated by gender. Because SLT use is often associated with stigma, and many women users may give socially desirable responses, emphasis on accurate and quality data reporting is necessary, particularly for large-scale surveys such as GATS and NFHS. Data collection and research on prevalence, determinants and health effects of SLT use among special population groups such as pregnant, lactating and older women need to be emphasized. Identification of specific regions, districts and subpopulation groups with higher burden of SLT use is critical to ensure focused interventions with local solutions.

Development of awareness materials and effective health safety warnings

Development of awareness materials and using information, education and communication strategy on SLT use is of utmost importance. Specific strategies such as enhanced health communication through packaging of SLT products depicting health risks for pregnant women are required. Further, a rights-based approach must be undertaken wherein the mother and other members of the social network are engaged in discourse over the well-being of the newborn and the potential impact of SLT use on newborn's health.

Priority setting in research areas

Research on cataloguing and identifying locally or indigenously produced SLT goods is essential. It is imperative to understand the patterns of use of these products, and the accompanying effects on health and nutrition, especially among women and girls, for development of effective de-addiction strategies. The linkages of SLT use and nutrition need to be examined; especially in lactating women. Research on the impact of health warning labels must also be conducted to ascertain their efficacy in enabling improved decision-making and quit attempts among women by age, literacy and education levels. This would enable the development of potent and effective health warning labels and awareness campaign. Examining the interface of tobacco industry interference such as manipulation of public opinion and tobacco control efforts can enable development of policies that can circumvent these manoeuvres, prevent initiation and enable cessation of SLT use.

Understanding social-embeddedness of use

Social-embeddedness and inter-generational linkages of SLT use need to be understood further as this may enable a deeper understanding of determinants and factors of initiation and continued use among women.

Identification of opportunities and challenges in quitting and development of interventions

Monitoring the extent of access to district cessation centres by women is crucial. Research on barriers to quitting and enrolling in cessation programmes will enable the development of more gender-sensitive cessation centres and culturally appropriate approaches. Behavioural change and psychosocial intervention models and tools need to be developed for those groups where pharmacological and nicotine replacement therapies are challenging, such as among pregnant women. Development of locally contextualized women-centric schemes and policies may enable focused attention to those States and regions, which have shown heavy prevalence of SLT use among women.

Capacity building

To design gender-sensitive cessation centres, orientation of individuals engaged in cessation efforts on enabling a women-friendly environment for quitting is crucial. Strengthening of the existing models and mechanisms of provision of healthcare must be done that aim to address the stigma surrounding SLT use, to provide safe and gender-sensitive de-addiction and cessation services. Health and wellness centres, village health, sanitation and nutrition committees and Mahila Arogya Samitis could be engaged in tobacco control efforts and equipped with effective cessation programmes aimed at women with close coordination and support of local self-help groups. Further, recording information on SLT use after thorough enquiry by local health providers, frontline workers, gynaecologists and other medical personnel involved in the delivery of antenatal care is essential. Patient history forms, especially antenatal care screening form, must include columns for SLT use for monitoring of risky behaviour among pregnant women. Training of healthcare providers on delivering help and support for SLT cessation in standard operating procedures may also enable cessation efforts without stigma.

Taxation and demand reduction

The overall effective taxation on SLT products in India, is roughly 60 per cent, which is below the recommended rate of 75 per cent as recommended by the WHO-MPOWER guidelines65. Hence, taxation on SLT products could be increased as a means to reduce consumption.

Footnotes

Financial support & sponsorship: This study was supported by the ICMR Task Force Study on Smokeless Tobacco and Reproductive & Maternal Health (No. RBMH/SLT/2018).

Conflicts of Interest: None.

References

- 1.Boffetta P, Hecht S, Gray N, Gupta P, Straif K. Smokeless tobacco and cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:667–75. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70173-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhisey RA. Chemistry and toxicology of smokeless tobacco. Indian J Cancer. 2012;49:364–72. doi: 10.4103/0019-509X.107735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stewart GG. A history of the medicinal use of tobacco 1492-1860. Med Hist. 1967;11:228–68. doi: 10.1017/s0025727300012333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hatsukami DK, Lemmonds C, Tomar SL. Smokeless tobacco use: Harm reduction or induction approach? Prev Med. 2004;38:309–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Savitz DA, Meyer RE, Tanzer JM, Mirvish SS, Lewin F. Public health implications of smokeless tobacco use as a harm reduction strategy. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:1934–9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.075499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gupta PC, Ray CS. Smokeless tobacco and health in India and South Asia. Respirology. 2003;8:419–31. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1843.2003.00507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O'Connor RJ. Non-cigarette tobacco products: What have we learnt and where are we headed? Tob Control. 2012;21:181–90. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sinha DN, Kumar A, Bhartiya D, Sharma S, Gupta PC, Singh H, et al. Smokeless tobacco use among adolescents in global perspective. Nicotine Tob Res. 2017;19:1395–6. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntx004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sinha DN, Gupta PC, Ray C, Singh PK. Prevalence of smokeless tobacco use among adults in WHO South-East Asia. Indian J Cancer. 2012;49:342–6. doi: 10.4103/0019-509X.107726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nethan S, Sinha D, Mehrotra R. Non communicable disease risk factors and their trends in India. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2017;18:2005–10. doi: 10.22034/APJCP.2017.18.7.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Asma S, Mackay J, Yang Song S, Zhao L, Morton J, Palipudi KM, et al. The GATS atlas. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Global Adult Tobacco Survey GATS 2 India 2016-17. [accessed on March 1, 2020]. Available from: https://wwwwhoint/tobacco/surveillance/survey/gats/GATS_India_2016-17_FactSheetpdfua=1 .

- 13.Global Adult Tobacco Survey India 2009-10. [accessed on March 1, 2020]. Available from: https://ntcpnhpgovin/assets/document/surveys-reports-publications/Global-Adult-Tobacco-Survey-India-2009-2010-Reportpdf .

- 14.Rogers JM. Tobacco and pregnancy: Overview of exposures and effects. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today. 2008;84:1–5. doi: 10.1002/bdrc.20119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Caleyachetty R, Tait CA, Kengne AP, Corvalan C, Uauy R, Echouffo-Tcheugui JB. Tobacco use in pregnant women: Analysis of data from Demographic and Health Surveys from 54 low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet Glob Health. 2014;2:e513–20. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70283-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National family health survey (NFHS-3), 2005-06: India. I. Mumbai: IIPS; 2007. International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and Macro International. [Google Scholar]

- 17.International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and ICF. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4), 2015-16: India. Mumbai: IIPS; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Palipudi KM, Gupta PC, Sinha DN, Andes LJ, Asma S, McAfee T, et al. Social determinants of health and tobacco use in thirteen low and middle income countries: Evidence from Global Adult Tobacco Survey. PLoS One. 2012;7:e33466. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singh A, Ladusingh L. Prevalence and determinants of tobacco use in India: Evidence from recent Global Adult Tobacco Survey data. PLoS One. 2014;9:e114073. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rani M, Bonu S, Jha P, Nguyen SN, Jamjoum L. Tobacco use in India: Prevalence and predictors of smoking and chewing in a national cross sectional household survey. Tob Control. 2003;12:e4. doi: 10.1136/tc.12.4.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sreeramareddy CT, Pradhan PM, Mir IA, Sin S. Smoking and smokeless tobacco use in nine South and Southeast Asian countries: Prevalence estimates and social determinants from Demographic and Health Surveys. Popul Health Metr. 2014;12:22. doi: 10.1186/s12963-014-0022-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thakur JS, Paika R. Determinants of smokeless tobacco use in India. Indian J Med Res. 2018;148:41–5. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_27_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Begum S, Schensul JJ, Nair S, Donta B. Initiating smokeless tobacco use across reproductive stages. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16:7547–54. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2015.16.17.7547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barakoti R, Ghimire A, Pandey AR, Baral DD, Pokharel PK. Tobacco use during pregnancy and its associated factors in a mountain district of Eastern Nepal: A cross-sectional questionnaire survey. Front Public Health. 2017;5:129. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2017.00129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nair S, Schensul JJ, Begum S, Pednekar MS, Oncken C, Bilgi SM, et al. Use of smokeless tobacco by Indian women aged 18-40 years during pregnancy and reproductive years. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0119814. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Narain R, Sardana S, Gupta S, Sehgal A. Age at initiation & prevalence of tobacco use among school children in Noida, India: A cross-sectional questionnaire based survey. Indian J Med Res. 2011;133:300–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Raute LJ, Sansone G, Pednekar MS, Fong GT, Gupta PC, Quah ACK, et al. Knowledge of health effects and intentions to quit among smokeless tobacco users in India: Findings from the International Tobacco Control Policy Evaluation (ITC) India Pilot Survey. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2011;12:1233–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patten CA, Renner CC, Decker PA, O'Campo E, Larsen K, Enoch C, et al. Tobacco use and cessation among pregnant Alaska Natives from Western Alaska enrolled in the WIC program, 2001-2002. Matern Child Health J. 2008;12(Suppl 1):30–6. doi: 10.1007/s10995-008-0331-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Senn M, Baiwog F, Winmai J, Mueller I, Rogerson S, Senn N. Betel nut chewing during pregnancy, Madang province, Papua New Guinea. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;105:126–31. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nelson BS, Heischober B. Betel nut: A common drug used by naturalized citizens from India, Far East Asia, and the South Pacific Islands. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;34:238–43. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(99)70239-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jayalekshmi PA, Gangadharan P, Akiba S, Nair RR, Tsuji M, Rajan B. Tobacco chewing and female oral cavity cancer risk in Karunagappally cohort, India. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:848–52. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Winn DM, Blot WJ, Shy CM, Pickle LW, Toledo A, Fraumeni JF., Jr Snuff dipping and oral cancer among women in the southern United States. N Engl J Med. 1981;304:745–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198103263041301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Phukan RK, Ali MS, Chetia CK, Mahanta J. Betel nut and tobacco chewing; potential risk factors of cancer of oesophagus in Assam, India. Br J Cancer. 2001;85:661–7. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.1920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sinha DN, Suliankatchi RA, Gupta PC, Thamarangsi T, Agarwal N, Parascandola M, et al. Global burden of all-cause and cause-specific mortality due to smokeless tobacco use: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Tob Control. 2018;27:35–42. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spangler JG, Quandt S, Bell RA. Smokeless tobacco and osteoporosis: A new relationship? Med Hypotheses. 2001;56:553–7. doi: 10.1054/mehy.2000.1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Asthana S, Labani S, Kailash U, Sinha DN, Mehrotra R. Association of smokeless tobacco use and oral cancer: A systematic global review and meta-analysis. Nicotine Tob Res. 2019;21:1162–71. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nty074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.England LJ, Kim SY, Tomar SL, Ray CS, Gupta PC, Eissenberg T, et al. Non-cigarette tobacco use among women and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2010;89:454–64. doi: 10.3109/00016341003605719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liao CY, Chen YJ, Lee JF, Lu CL, Chen CH. Cigarettes and the developing brain: Picturing nicotine as a neuroteratogen using clinical and preclinical studies. Tzu Chi Med J. 2012;24:157–61. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rogers JM. Tobacco and pregnancy. Reprod Toxicol. 2009;28:152–60. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2009.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ashfaq M, Channa MA, Malik MA, Khan D. Morphological changes in human placenta of wet snuff users. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2008;20:110–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Agrawal P, Chansoriya M, Kaul KK. Effect of tobacco chewing by mothers on placental morphology. Indian Pediatr. 1983;20:561–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pratinidhi A, Gandham S, Shrotri A, Patil A, Pardeshi S. Use of ‘Mishri’ a smokeless form of tobacco during pregnancy and its perinatal outcome. Indian J Community Med. 2010;35:14–8. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.62547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gupta PC, Subramoney S. Smokeless tobacco use, birth weight, and gestational age: Population based, prospective cohort study of 1217 women in Mumbai, India. BMJ. 2004;328:1538. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38113.687882.EB. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gupta PC, Subramoney S. Smokeless tobacco use and risk of stillbirth: A cohort study in Mumbai, India. Epidemiology. 2006;17:47–51. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000190545.19168.c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pednekar MS, Gupta PC, Shukla HC, Hebert JR. Association between tobacco use and body mass index in urban Indian population: Implications for public health in India. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:70. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Keusch GT. The history of nutrition: Malnutrition, infection and immunity. J Nutr. 2003;133:336S–40S. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.1.336S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rao S, Yajnik CS, Kanade A, Fall CH, Margetts BM, Jackson AA, et al. Intake of micronutrient-rich foods in rural Indian mothers is associated with the size of their babies at birth: Pune Maternal Nutrition Study. J Nutr. 2001;131:1217–24. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.4.1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Subramoney S, Gupta PC. Anemia in pregnant women who use smokeless tobacco. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10:917–20. doi: 10.1080/14622200802027206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Murthy P, Saddichha S. Tobacco cessation services in India: Recent developments and the need for expansion. Indian J Cancer. 2010;47(Suppl 1):69–74. doi: 10.4103/0019-509X.63873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Piano MR, Benowitz NL, Fitzgerald GA, Corbridge S, Heath J, Hahn E, et al. Impact of smokeless tobacco products on cardiovascular disease: Implications for policy, prevention, and treatment: A policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010;122:1520–44. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3181f432c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gupta PC, Ray CS, Sinha DN, Singh PK. Smokeless tobacco: A major public health problem in the SEA region: A review. Indian J Public Health. 2011;55:199–209. doi: 10.4103/0019-557X.89948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Burki TK. WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control conference. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:e588. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)71037-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.The Gazette of India. The Cigarettes and Other Tobacco Products (Prohibition of advertisement and regulation of trade and commerce, production, supply and distribution) Act. 2003. [accessed on Februray 12, 2020]. Available from: http://wwwhpgovin/dhsrhp/COTPA Act-2003pdf .

- 54.National Tobacco Control Cell. Operating Guidelines - National Tobacco Control Programme. New Delhi: Ministry of Health & Family Welfare Government of India; 2015. [accessed on February 12, 2020]. Available from: https://nhmgovin/NTCP/Manuals_Guidelines/Operational_Guidelines-NTCPpdf . [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mohan P, Lando HA, Panneer S. Assessment of Tobacco Consumption and Control in India. Indian J Clin Med. 2018;9:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kaur J, Jain DC. Tobacco control policies in India: Implementation and challenges. Indian J Public Health. 2011;55:220–7. doi: 10.4103/0019-557X.89941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yadav A, Singh A, Khadka BB, Amarasinghe H, Yadav N, Singh R. Smokeless tobacco control: Litigation & judicial measures from Southeast Asia. Indian J Med Res. 2018;148:25–34. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_2063_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Siddiqi K, Vidyasagaran AL, Readshaw A, Croucher R. A policy perspective on the global use of smokeless tobacco. Curr Addict Rep. 2017;4:503–10. doi: 10.1007/s40429-017-0166-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lal P, Singh RJ, Pandey AK. Opening gambit: Strategic options to initiate the tobacco endgame. Indian J Public Health. 2017;61:S60–2. doi: 10.4103/ijph.IJPH_231_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kumar MS, Sarma PS, Thankappan KR. Community-based group intervention for tobacco cessation in rural Tamil Nadu, India: A cluster randomized trial. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2012;43:53–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2011.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Scriver CR. The Oxford medical companion. BMJ. 1995;310:609. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Amos A, Greaves L, Nichter M, Bloch M. Women and tobacco: A call for including gender in tobacco control research, policy and practice. Tob Control. 2012;21:236–43. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, Government of India. National Health Policy. 2017. [accessed on March 1, 2020]. Available from: https://www.nhp.gov.in/nhpfiles/national_health_policy_2017.pdf .

- 64.United Nations. The Sustainable Development Goals Report. New York: United Nations Publications; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 65.John RM, Yadav A, Sinha DN. Smokeless tobacco taxation: Lessons from Southeast Asia. Indian J Med Res. 2018;148:46–55. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_1822_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]