Abstract

Cronkhite–Canada syndrome (CCS) is a rare acquired polyposis with unknown etiology. To date, >500 cases have been reported worldwide. CCS is typically characterized by gastrointestinal symptoms, such as diarrhea and skin changes (e.g. alopecia, pigmentation, and nail atrophy). Endoscopic features include diffuse polyps throughout the entire gastrointestinal tract, except for the esophagus. Pathological types of polyps in CCS mainly include inflammatory, hyperplastic, hamartomatous, and adenomatous polyps. CCS can be complicated by many diseases and has a canceration tendency with a high mortality rate. Moreover, there is no uniform standard treatment for CCS. A review of the reported cases of CCS is presented herein, with the goal of improving our understanding of this disease.

Keywords: Cronkhite–Canada syndrome, clinical characteristics, gastrointestinal polyps, malignant transformation

Introduction

Cronkhite–Canada syndrome (CCS) is a rare disease that was first reported by Cronkhite and Canada in 1955 [1]. More than 500 cases have been reported worldwide, with most of the cases being reported in Japan [2]. A study of 210 patients in Japan found that the age of onset of symptomatic CCS ranged from 31 to 86 years, with an average age of 63.5 years [3]. Another study found that 80% of patients were older than 50 years [4]. Sporadic disease also occurs in young people. Three cases of CCS in individuals younger than 30 years old have been reported [5–7]. Analysis of CCS data from China showed that the age of symptomatic CCS onset in China was 21–77 years, with an average age of 58.28 years, and 81.6% of these patients were older than 50 years [8]. There are slightly more cases among males than females; a study conducted in Japan showed that the ratio of males to females is 1.84:1 [3], whereas a study conducted in China showed that the ratio of males to females is 2:1 [8]. The prognosis of CCS is poor, with a 5-year mortality rate of 55% [9]. Although most reported cases of CCS are sporadic, nonhereditary, and nonfamilial, Patil et al. [10] reported CCS in a 50-year-old male patient and his 22-year-old son in India. Currently, the etiology of CCS is unknown and it has a high mortality rate. Moreover, there is no uniform treatment standard. Therefore, we reviewed the clinical manifestations, endoscopic features, pathological features, complications, and treatment of CCS to gain a better understanding of this disease.

Case presentation

A 62-year-old male visited our hospital and presented with a loss of appetite; epigastric discomfort; hair, eyebrow, and beard loss; diarrhea; taste loss; weight loss; and nail atrophy after oral administration of a traditional Chinese medicine >2 months prior. Figure 1 shows the patient’s hair loss and nail atrophy. He complained of watery stool five to eight times per day and a small amount of melena intermittently. Gastroscopy performed previously at the patient’s local hospital revealed atrophic gastritis and the pathology results suggested chronic gastritis. However, we did not view the report in detail. Doctors at the local hospital administered symptomatic treatment, but the patient unfortunately showed no improvement.

Figure 1.

Hair loss and nail atrophy

Therefore, the patient was admitted to our hospital. A colonoscopy revealed that the whole colonic mucosa was congested and edematous, with dense nodular hyperplasia. There were also numerous sessile or semipedunculated polypoid protuberances in the colon (Figure 2A). Gastroscopy showed that the mucosa of the gastric antrum and angle exhibited an uneven and nodular appearance, and the mucosa was congested and edematous (Figure 3A). Capsule endoscopy showed that partial small-intestinal mucosa was edematous and congested with villous atrophy (Figure 4). Pathological examination showed local mucosal gland cystic dilatation with intraluminal fluid (Figure 5). The serum IgE was 238.50 IU/ml (normal range 0–100 IU/mL), eosinophil count was normal, serum albumin was 31.6 g/L (normal range 40–55 g/L), serum calcium was 1.91 mmol/L (normal range 2.17–2.57 mmol/L), and other ions were within normal ranges. Antinuclear antibody (ANA), antimitochondrial antibody (AMA), smooth-muscle antibody, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody were negative, and fecal occult blood was positive. Upon combining the clinical, endoscopic, and pathological features of the patient, a diagnosis of CCS was made.

Figure 2.

No obvious changes in colonoscopic findings (A) before and (B) after treatment with prednisone and mesalazine. The whole colonic mucosa was congested and edematous, with dense nodular hyperplasia. There were numerous sessile or semipedunculated polypoid protuberances in the colon.

Figure 3.

No obvious changes in gastroscopic findings (A) before and (B) after treatment with prednisone and mesalazine. The mucosa of the gastric antrum and angle exhibited an uneven and nodular appearance, and the mucosa was congested and edematous.

Figure 4.

Capsule endoscopy showing edematous and congested mucosa of the small intestine with villous atrophy

Figure 5.

Histopathology of the colon (hematoxylin-erosin staining). (A) Local mucosal gland cystic dilatation with intraluminal fluid (×100). (B) Eosinophils infiltration (×200).

After obtaining a definite diagnosis, prednisone 40 mg/d combined with mesalazine 1.0 g three times a day was administered orally. After treatment with prednisone and mesalazine, symptoms such as diarrhea were gradually improved. One month later, the patient underwent gastroscopy and colonoscopy again to assess the condition of the digestive tract and resect partial large-intestinal polyps, showing no obvious improvement in endoscopic findings (Figure 2B and C).

Etiology

The etiology of CCS is not clear. Both psychological and physical stress may be important risk factors [11]. The occurrence of CCS under psychological stress and after colectomy and left-heel-bone fracture has been reported [12–14]. One case even improved only after pressure relief without treatment [3]. In addition, many studies have reported that CCS may have an autoimmune background. First, patients with CCS can appear ANA and anti-Saccaromyces cerevisiae antibody-positive [12, 15, 16]. IgG4-positive plasma-cell infiltration was also found in CCS polyps [17–19]. Second, CCS was reported to be associated with autoimmune diseases such as hypothyroidism and membranous nephropathy [15, 16, 20, 21]. However, another study conducted in China showed that the results of autoimmune tests among patients with CCS were nearly normal [8]. Helicobacter pylori (Hp) infection may also play a role in the pathogenesis of CCS. A correlation between CCS and Hp infection has been reported in some cases. Watanabe et al. [3] found that 54% of patients with CCS had Hp infection and some studies noted that CCS was alleviated after Hp eradication [22–24].

Gene mutations may also be involved in CCS. Genome-wide analysis revealed that PRKDC gene mutation may play a role in the pathogenesis of CCS [25]. Wang et al. [26] reported a family in which both the mother and child suffered from CCS in China. They carried out genetic analysis and found that both the mother and the child had APC gene C. 3921-3925delAAAAG (p. Ile1307fsX6) mutation. These findings indicate that CCS may not be entirely nonhereditary.

Allergic reactions may also be a cause [15]. There are cases of CCS after oral administration of thyroxine [27]. Our case also occurred after oral administration of a traditional Chinese medicine. Moreover, in our case, the serum IgE level increased significantly. Although we cannot confirm whether there is a necessary link between allergic reactions and CCS, it is speculated that allergic reactions induced by drugs may participate in CCS pathogenesis.

In summary, the pathogenesis of CCS may be complex and many factors participate in its occurrence and development (Table 1).

Table 1.

Possible etiology of Cronkhite–Canada syndrome

| Non-genetic correlation |

|---|

| Psychological stress and physical stress |

| Autoimmune |

| Helicobacter pylori infection |

| Allergic reaction |

| Gene correlation |

| PRKDC gene variation |

| Mutation of the C.3921-3925delAAG (p.Ile1307fsX6) locus in APC gene |

Clinical features

Typical symptoms of CCS include hypogeusia, diarrhea, abdominal pain, alopecia, skin pigmentation, onychodystrophy, and even onychomadesis. A patient may have some or all of the above symptoms. Japanese scholars classified CCS into five types based on the presenting symptoms: Type I, with diarrhea as the initial symptom; Type II, with hypogeusia as the initial symptom; Type III, with thirst or abnormal sensation in the mouth as the initial symptom; Type IV, with abdominal discomfort other than diarrhea as the initial symptom; and Type V, with alopecia as the initial symptom [11].

The most common initial symptom of CCS is hypogeusia [11, 28], which may be related to zinc deficiency. Some patients with taste loss reported improvement after zinc supplementation [29, 30]. Gastrointestinal symptoms are mostly related to gastrointestinal mucosal changes.

With regard to skin changes, pigmentation of the skin is a vital sign, such as brown macula or red nonpruritic nodular papules, which can be seen on the scalp, wrist, palms, soles, limbs, face, and chest [3, 12, 31]. Yuan et al. reported that pigmentation can also occur in the oral mucosa [32]. However, not all the patients had apparent pigmentation and there was no significant pigmentation in our patients. Nail changes and hair loss are other characteristic changes of CCS. Typical nail changes include thin, soft, triangular nail plates [33]. Typical alopecia involves hair loss, but it is not limited to hair; eyebrows and eyelashes can also fall out [34]. In our case, the hair, eyebrows, and beard were all lost. It is generally believed that nail changes, hair loss, and other skin manifestations are related to malnutrition [3, 28]. Watanabe-Okada et al. [35] found no inflammatory cell infiltration and no hair-follicle atrophy in the scalp, and only diffuse anagen–telogen transition was found. Therefore, they believe that hair loss is caused by malnutrition. However, Jarnum and Jensen [36] have reported different opinions, namely that ectodermal alterations may not be caused by malnutrition. First, when skin lesions occur, the weight and nutritional status of some patients are still normal [37]. Second, Chuamanochan et al. [38] performed a pathological analysis of the nail matrix and found matrix hypergranulosis, which is generally caused by inflammation, so the change in nail atrophy may be caused by inflammation, rather than malnutrition. Third, scalp biopsy showed peripheral lymphocyte infiltration of the hair bulb [34], epidermal atrophy, and hair-follicle atrophy [39]. Horikawa et al. [40] also found lymphocyte infiltration around the anagen hair bulbs, suggesting that malnutrition may not be the only promoting factor of skin changes.

The type of symptoms and the sequence of symptoms appearing in CCS remain unknown. For example, in some instances, skin changes such as alopecia can occur before gastrointestinal symptoms [41]. One patient was reported to present with only alopecia and nail atrophy, and not diarrhea or other gastrointestinal symptoms; when they visited a doctor for anemia and positive fecal occult blood, numerous polyps were found in the colon [42]. A 51-year-old female patient in Japan was diagnosed with CCS due to progressive alopecia, fatigue, and emaciation, but she also did not present any gastrointestinal symptoms [35]. One patient was even completely asymptomatic [43].

Early-stage CCS may manifest as inflammatory bowel disease, e.g. intermittent abdominal pain, diarrhea, mucous, and bloody stool, and colonoscopy showing a colitis-like appearance. Changes in skin appearance and taste loss appeared later, and numerous polyps were found by colonoscopy. Therefore, CCS may be misdiagnosed as ulcerative colitis and intestinal tuberculosis in the early stage [44, 45]. It was reported that a male patient with CCS had symptoms such as taste loss, alopecia, nail atrophy, anorexia, nausea, and mild epigastric pain with no polyps in the gastrointestinal tract; only diffuse gastroduodenal mucosal edema and severe atrophy were found [46]. Anderson et al. [37] reported a unique CCS case: at the first visit, no polyps were observed in the stomach; only thickening and hypertrophy of gastric folds, erythema, and edema of the mucosa were found. The pathology results showed a large amount of eosinophilic infiltration and the patient was initially misdiagnosed as having eosinophilic gastroenteritis. However, gastric mucosal atrophy and numerous polyps of the entire digestive tract were found several weeks later.

Endoscopic characteristics

Although it is generally believed that CCS can involve all digestive tracts, except the esophagus, there are also cases of CCS with esophageal squamous cell papilloma and esophageal tumors [47, 48]. However, the relationship between them has not been confirmed. A Japanese study showed that CCS with esophageal lesions accounted for 12.3% of cases [3]. Although most cases exhibit non-specific inflammation, some are squamous cell papillomas. A retrospective analysis of six CCS cases showed one case with esophageal polyps [15].

In patients with CCS, numerous sessile polyps with normal or abnormal mucosa are observed in the stomach [3]. A study in China showed that polyps in the gastric antrum are the most common [8]. Research in Korea also reported that polyps in the distal part of the stomach are more numerous and larger than those in the proximal part [49]. The gastric mucosa can also have a nodular appearance and the distal portion of the gastric body is more predominant than the proximal part, with a polypoid appearance in the gastric antrum [50]. It seems that lesions show a trend toward increasing severity from the gastric body to the gastric antrum. From this point of view, Hp infection may promote the onset of CCS. Polyps can also be absent in the stomach, with only gastroduodenal inflammation and numerous polyps present in the colon [51].

Yun et al. [49] reported that ∼50% of patients had small-intestine involvement in Korea, primarily in the duodenum and terminal ileum. Cao et al. [52] reported changes in the small intestine among patients with CCS undergoing capsule endoscopy, e.g. actinian-like intestinal mucosa, diffuse herpes-like polyps in the jejunum, and diffuse strawberry-like red polyps in the ileum. White, elongated, and branched villi were observed in the duodenum and jejunum, but this change gradually diminished along the small bowel and the distal ileum mucosa showed atrophy [53, 54]. Small-intestinal mucosa could be edematous and reddened, and villi can also be enlarged or atrophic [55]. Further observation of the small intestine by magnifying endoscopy revealed an irregular villus structure, scattered white spots on the tips of the villi (pathology confirmed that the white spots were dilated lymphatic vessels), fine granular structures at the tops of the villi, loops in blood vessels with different sizes, and punctate erythema within the villi (pathology confirmed intestinal bleeding) [55].

The colon may have sessile, hemipedunculated, or pedunculated polyps, ranging from 2 to 40 mm [3, 12, 50, 56]. Patients with CCS without polyps may exhibit the following endoscopy findings: mucosal edema and congestion, mosaic-like changes in the gastric mucosa, abnormal duodenal fold with furrowing, and nodular changes in the small intestine [46].

Pathological characteristics

There are several pathological types of polyps in CCS: inflammatory polyps, hyperplastic polyps, hamartomatous polyps, and adenomatous polyps [28, 42, 56–58]. In adenomatous polyps, tubular adenoma, tubular adenoma with low-grade intraepithelial neoplasia, and villous tubular adenoma with locally well-differentiated adenocarcinoma have been reported [3, 58, 59]. Serrated adenoma has also been found [49]. Tubular adenoma and villous tubular adenoma with low-grade intraepithelial neoplasia were found in our case, but no canceration was found. CCS also have the following pathological characteristics: inflammatory cell infiltration dominated by eosinophils, gland/crypt changes (gland/crypt cystic dilatation with some filled with protein fluid or mucus, withering, and branching), lamina propria edema, and duodenal villous atrophy [3, 60]. Mucosa edema with chronic inflammation and hyperemia in the lamina propria and submucosa can be found in areas without polyps [3]. IgG4-positive plasma-cell infiltration can also occur in CCS polyps [17–19].

Diagnosis and differential diagnosis

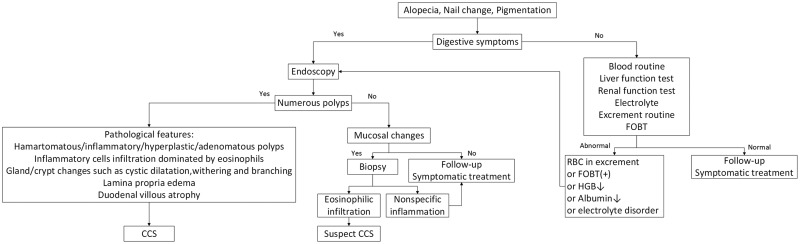

The diagnosis of CCS is dependent on a combination of clinical, endoscopic, and pathological features. Based on the relevant literature, we present our own perspective on the diagnosis of CCS, as shown in Figures 6 and 7.

Figure 6.

Diagnostic flow chart of Cronkhite–Canada syndrome (CCS) with skin-change onset. HOBT, fecal occult blood test; RBC, red blood count; HGB, hemoglobin.

Figure 7.

Diagnostic flow chart of Cronkhite–Canada syndrome (CCS) with digestive-symptom onset

Although CCS is a rare disease, it still needs to be differentiated from some other diseases. Typical digestive-tract polyps need to be differentiated from the following: Peutz–Jeghers syndrome, familial adenomatous polyposis, juvenile polyposis, Cowden disease, cap polyposis, and Ménétrier's disease [2, 58]. For patients with atypical symptoms and endoscopic features, inflammatory bowel disease, gastric fundus gland polyps, and HP-related inflammatory polyps need to be differentiated [43]. For patients with atypical symptoms, endoscopic features, and pathological findings indicating eosinophilic infiltration, eosinophilic gastroenteritis, celiac disease, vasculitis, parasitic infection, and lymphoma should be taken into consideration for the differential diagnosis [37].

Complications

CCS can be complicated by many diseases and tends to be malignant. A total of 10%–20% of CCS patients have gastric cancer and other gastrointestinal cancers. Additionally, >75% of complicated gastric cancers are highly differentiated adenocarcinomas, most of which are limited to within T1 [3, 61, 62]. The types of gastric cancer associated with CCS are gastric-type cancer with MUC5AC positivity [62] and complete intestinal-type gastric cancer in high-grade hyperplasia with CD10 positivity [63]. The intestinal tumors associated with CCS include major duodenal papillary adenocarcinoma and colon cancer [64–66]. There are many polyps in the background of CCS. The mechanism of malignant transformation is therefore worthy of further study. Nagata et al. [65] speculated that the polyp–adenoma–tumor pathway may be involved in CCS canceration. Moreover, a Japanese study found that serrated adenoma was present in 40% patients with CCS, and microsatellite instability and P53 overexpression existed in both the tumors and adenomas of CCS in a case of CCS [67]. No loss of heterozygosity of genes or KRAS mutations was found in that case. These results indicated that the serrated adenoma–tumor malignant-transformation pathway may exist in CCS. In addition, CCS can also be complicated with villous adenocarcinoma, causing McKittrick–Wheelock syndrome [68].

Intestinal mucosal changes in CCS patients lead to malabsorption, hypocalcemia, and vitamin D deficiency, which can ultimately lead to rib fracture and flail chest [56, 69]. CCS combined with vestibular dysfunction, arteriovenous thrombosis, and pulmonary embolism has also been reported [70–72]. CCS can even be complicated by peripheral neuropathy such as mononeuritis multiplex, which affects sensory and motor conduction. The underlying reason remains unclear. However, studies found that the number of myelinated nerve fibers decreased in the sural nerve [73, 74].

Malnutrition, water and electrolyte disorders, hypoproteinemia [2], chronic inflammatory anemia [27], gastrointestinal bleeding, intussusception [3], major duodenal papillary prolapse [75], and recurrent pancreatitis (caused by polyps in Vater's ampulla) [76] have also been found in CCS patients. Our case was also found to have hypocalcemia and hypoproteinemia. Indeed, hypoalbuminemia, malnutrition, heart failure, gastrointestinal bleeding, repeated infection, and sepsis are considered to be causes of CCS-related death [49, 51]. Moreover, some patients suffer from recurrent hematochezia and even require colorectal resection [77].

Treatment

There is no consensus on the treatment of CCS and there is no uniform standard of treatment. The reported cases received the following treatments:

Hormone therapy is the main treatment and prednisone is the major drug. Over 85% of patients responded to a dosage of >30 mg/d [3]. The initial dosages reported were different, including 40 mg/d [56, 67], 30 mg/d, 50 mg/d, 60 mg/d [12, 35, 64], or 1 mg/kg per day [15, 78]. In Chinese reports, 20 mg/d as the initial dosage was also effective, although the patients relapsed after the dosage was reduced to 10 mg/d [14, 79]. As a result, the dosage should be decreased gradually and slowly after symptoms improve according to the situation of the patient.

Anti-TNF-α therapy: a high expression of TNF-α was detected in the small-intestinal mucosa of patients with CCS [80]. Some studies reported that infliximab exerted a good therapeutic effect on CCS [25, 81].

Eradication of Hp: CCS was relieved after Hp eradication [22, 24].

Some patients with hormone-treatment failure or hormone resistance were treated with immunosuppressive agents, such as cyclosporine, azathioprine, and sirolimus, which were also effective [82–84].

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, such as salazosulfapyridine, were also administered [43]. A study reported that sulindac was used to treat colorectal adenomas and CCS polyps, and that remission was achieved [85].

The combination of hormone and mesalazine for the treatment of CCS was found to achieve long-term relief [86, 87]. In our case, prednisone combined with mesalazine was used and the symptoms were well controlled. No diarrhea relapse occurred, and the hair and nails gradually recovered.

Symptomatic treatment and nutritional-support therapy [89].

Acid suppression and antibiotic treatments were also administered [20].

Tranexamic acid is also a choice if other treatments are ineffective or unsuitable for patients [90].

Severe and refractory protein-losing enteropathy induced by CCS could be treated by surgery [91, 92].

Polyps that are large or have the potential for malignant transformation according to endoscopic appearance and pathology need to be removed at an early stage. Malignant lesions should be resected in time.

We present a treatment flowchart of CCS, as shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Treatment flow chart of Cronkhite–Canada syndrome (CCS)

Conclusions

CCS is a rare disease and its etiology is not yet clear. Clinical, endoscopic, and pathological characteristics appear to be non-specific. When digestive-tract symptoms and skin changes co-occur, CCS should be considered. Considering its high mortality and malignant-transformation rate, early diagnosis and treatment are very important. Follow-up and monitoring are also necessary. How to identify early malignant polyps from a large number of polyps deserves more attention. Interestingly, Watari et al. [63] found that malignant polyps are discolored among other reddish polyps. Therefore, it may be necessary to pay attention to this feature when examining and monitoring patients with CCS. In addition, there are no reports on the changes in intestinal flora in patients with CCS. Changes in the intestinal flora play a role in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease, irritable bowel syndrome, and other intestinal diseases. Therefore, the intestinal flora may also play a role in the pathogenesis of CCS, which should be explored in the future.

Authors’ contributions

Z.Y.W, L.X.S and B.C conceptualized and designed the structure of the manuscript; Z.Y.W, L.X.S and B.C reviewed the literature; Z.Y.W drafted the manuscript; L.X.S and B.C critically revised the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Innovative Talent Support Program of the Institution of Higher Learning in Liaoning Province [No. 2018-478] and the Innovative Talents of Science and Technology Support Program of Young and Middle Aged People of Shenyang [RC170446].

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Contributor Information

Ze-Yu Wu, Department of Gastroenterology, First Hospital of China Medical University, Shenyang, Liaoning, P. R. China.

Li-Xuan Sang, Department of Geriatrics, First Hospital of China Medical University, Shenyang, Liaoning, P. R. China.

Bing Chang, Department of Gastroenterology, First Hospital of China Medical University, Shenyang, Liaoning, P. R. China.

References

- 1. Cronkhite LW Jr, Canada WJ. Generalized gastrointestinal polyposis; an unusual syndrome of polyposis, pigmentation, alopecia and onychotrophia. N Engl J Med 1955;252:1011–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Slavik T, Montgomery EA. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome six decades on the many faces of an enigmatic disease. J Clin Pathol 2014;67:891–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Watanabe C, Komoto S, Tomita K et al. Endoscopic and clinical evaluation of treatment and prognosis of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: a Japanese nationwide survey. J Gastroenterol 2016;51:327–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Daniel ES, Ludwig SL, Lewin KJ et al. The Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: an analysis of clinical and pathologic features and therapy in 55 patients. Medicine (Baltimore ) 1982;61:293–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Faria MAG, Basaglia B, Nogueira VQM et al. A case of adolescent Cronkhite-Canada syndrome. Gastroenterol Res 2018;11:64–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vernia P, Marcheggiano A, Marinaro V et al. Is Cronkhite-Canada syndrome necessarily a late-onset disease? Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2005;17:1139–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bandyopadhyay D, Hajra A, Ganesan V et al. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: a rare cause of chronic diarrhoea in a young man. Case Rep Med 2016;2016:1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. She Q, Jiang JX, Si XM et al. A severe course of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome and the review of clinical features and therapy in 49 Chinese patients. Turk J Gastroenterol 2013;24:277–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Padda MS, Ryu J, Pham BV. Unusual cause of diarrhea: Cronkhite-Canada syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008;6:A28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Patil V, Patil LS, Jakareddy R et al. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: a report of two familial cases. Indian J Gastroenterol 2013;32:119–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Goto A. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: epidemiological study of 110 cases reported in Japan. Nihon Geka Hokan 1995;64:3–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Murata I, Yoshikawa I, Endo M et al. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: report of two cases. J Gastroenterol 2000;35:706–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ikeda K, Sannohe Y, Murayama H. A case of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome developing after hemi-colectomy. Endoscopy 1981;13:251–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zong Y, Zhao H, Yu L et al. Case report-malignant transformation in Cronkhite-Canada syndrome polyp. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96:e6051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wen XH, Wang L, Wang YX et al. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: report of six cases and review of literature. World J Gastroenterol 2014;20:7518–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Takeuchi Y, Yoshikawa M, Tsukamoto N et al. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome with colon cancer, portal thrombosis, high titer of antinuclear antibodies, and membranous glomerulonephritis. J Gastroenterol 2003;38:791–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fan RY, Wang XW, Xue LJ et al. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome polyps infiltrated with IgG4-positive plasma cells. World J Clin Cases 2016;4:248–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Riegert-Johnson DL, Osborn N, Smyrk T et al. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome hamartomatous polyps are infiltrated with IgG4 plasma cells. Digestion 2007;75:96–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sweetser S, Ahlquist DA, Osborn NK et al. Clinicopathologic features and treatment outcomes in Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: support for autoimmunity. Dig Dis Sci 2012;57:496–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Qiao M, Lei Z, Nai-Zhong H et al. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome with hypothyroidism. South Med J 2005;98:575–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Firth C, Harris LA, Smith ML et al. A case report of Cronkhite-Canada Syndrome complicated by membranous nephropathy. Case Rep Nephrol Dial 2018;8:261–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Okamoto K, Isomoto H, Shikuwa S et al. A case of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: remission after treatment with anti-Helicobacter pylori regimen. Digestion 2008;78:82–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kim MS, Jung HK, Jung HS et al. [A case of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome showing resolution with Helicobacter pylori eradication and omeprazole] (in Korean). Korean J Gastroenterol 2006;47:59–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kato K, Ishii Y, Mazaki T et al. Spontaneous regression of polyposis following abdominal colectomy and helicobacter pylori eradication for Cronkhite-Canada Syndrome. Case Rep Gastroenterol 2013;7:140–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Boland BS, Bagi P, Valasek MA et al. Cronkhite Canada syndrome: significant response to infliximab and a possible clue to pathogenesis. Am J Gastroenterol 2016;111:746–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wang JY, Lu WQ, Ning HB. [ Clinical analysis of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome] (in Chinese). Henan Med Res 2019;28:1931–5. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ho V, Banney L, Falhammar H. Hyperpigmentation, nail dystrophy and alopecia with generalised intestinal polyposis: Cronkhite-Canada syndrome. Aust J Dermatol 2008;49:223–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kopáčová M, Urban O, Cyrany J et al. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: review of the literature. Gastroenterol Res Pract 2013;2013:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yoshida S, Tomita H. A case of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome whose major complaint, taste disturbance, was improved by zinc therapy. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl 2002;122:154–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dawra S, Sharma V, Dutta U. Clinical and endoscopic remission in a patient with Cronkhite-Canada syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018;16:e84–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Aoun E, Victain M, Mitre MC. Diarrhoea, weight loss and polyposis: think Cronkhite-Canada syndrome. BMJ Case Rep 2011;2011:bcr0820114640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yuan W, Tian L, Ai FY et al. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: a case report. Oncol Lett 2018;15:8447–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Piraccini BM, Rech G, Sisti A et al. Twenty nail onychomadesis: an unusual finding in Cronkhite-Canada syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol 2010;63:172–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ong S, Rodriguez-Garcia C, Grabczynska S et al. Alopecia areata incognita in Cronkhite-Canada syndrome. Br J Dermatol 2017;177:531–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Watanabe-Okada E, Inazumi T, Matsukawa H et al. Histopathological insights into hair loss in Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: diffuse anagen-telogen conversion precedes clinical hair loss progression. Aust J Dermatol 2014;55:145–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Jarnum S, Jensen H. Diffuse gastrointestinal polyposis with ectodermal changes. a case with severe malabsorption and enteric loss of plasma proteins and electrolytes. Gastroenterology 1966;50:107–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Anderson RD, Patel R, Hamilton JK et al. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome presenting as eosinophilic gastroenteritis. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 2006;19:209–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chuamanochan M, Tovanabutra N, Mahanupab P et al. Nail matrix pathology in Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: the first case report. Am J Dermatopathol 2017;39:860–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kindblom LG, Angervall L, Santesson B et al. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome. case report. Cancer 1977;39:2651–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Horikawa H, Hirai I, Umegaki-Arao N et al. Alopecia in Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: is it truly telogen effluvium? Aust J Dermatol 2019;60:e342–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Choi YJ, Lee DH, Song EJ et al. Vitiligo: an unusual finding in Cronkhite-Canada syndrome. J Dermatol 2013;40:848–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rubio CA, Björk J. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: a case report. Anticancer Res 2016;36:4215–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ueyama H, Fu KI, Ogura K et al. Successful treatment for Cronkhite-Canada syndrome with endoscopic mucosal resection and salazosulfapyridine. Tech Coloproctol 2014;18:503–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Xue LY, Hu RW, Zheng SM et al. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: a case report and review of literature. J Dig Dis 2013;14:203–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Urabe S, Akazawa Y, Takeshima F. A case of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome with a colitis-mimicking endoscopic presentation. J Crohns Colitis 2015;9:1179–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. De Petris G, Chen L, Pasha SF et al. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome diagnosis in the absence of gastrointestinal polyps: a case report. Int J Surg Pathol 2013;21:627–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sharma V, Mandavdhare HS, Prasad KK et al. Gastrointestinal: esophageal squamous cell papilloma in a patient with Cronkhite-Canada syndrome. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018;33:1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ito M, Matsumoto S, Takayama T et al. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome associated with esophageal and gastric cancers: report of a case. Surg Today 2015;45:777–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Yun SH, Cho JW, Kim JW et al. Cronkhite-Canada Syndrome associated with serrated adenoma and malignant polyp: a case report and a literature review of 13 Cronkhite-Canada Syndrome cases in Korea. Clin Endosc 2013;46:301–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Flannery CM, Lunn JA. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: an unusual finding of gastro-intestinal adenomatous polyps in a syndrome characterized by hamartomatous polyps. Gastroenterol Rep 2015;3:254–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Iqbal U, Chaudhary A, Karim MA et al. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: a rare cause of chronic diarrhea. Gastroenterol Res 2017;10:196–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Cao XCWB, Han ZC. Wireless capsule endoscopic finding in Cronkhite-Canada syndrome. Gut 2006;55:899–900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Wallenhorst T, Pagenault M, Bouguen G et al. Small-bowel video capsule endoscopic findings of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome. Gastrointest Endosc 2016;84:739–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Heinzow HS, Domschke W, Meister T. Innovative video capsule endoscopy for detection of ubiquitously elongated small intestinal villi in Cronkhite-Canada syndrome. Wideochir Inne Tech Maloinwazyjne 2014;1:121–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Murata M, Bamba S, Takahashi K et al. Application of novel magnified single balloon enteroscopy for a patient with Cronkhite-Canada syndrome. World J Gastroenterol 2017;23:4121–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Yuan B, Jin X, Zhu R et al. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome associated with rib fractures: a case report. BMC Gastroenterol 2010;10:121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Jha AK, Kumar A, Singh SK et al. Panendoscopic characterization of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome. Med J Armed Forces India 2018;74:196–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Sweetser S, Alexander GL, Boardman LA. A case of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome presenting with adenomatous and inflammatory colon polyps. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010;7:460–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Jain A, Nanda S, Chakraborty P et al. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome with adenomatous and carcinomatous transformation of colonic polyp. Indian J Gastroenterol 2003;22:189–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Bettington M, Brown IS, Kumarasinghe MP et al. The challenging diagnosis of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome in the upper gastrointestinal tract: a series of 7 cases with clinical follow-up. Am J Surg Pathol 2014;38:215–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Egawa T, Kubota T, Otani Y et al. Surgically treated Cronkhite-Canada syndrome associated with gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer 2000;3:156–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Karasawa H, Miura K, Ishida K et al. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome complicated with huge intramucosal gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer 2009;12:113–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Watari J, Morita T, Sakurai J et al. Endoscopically treated Cronkhite-Canada syndrome associated with minute intramucosal gastric cancer: an analysis of molecular pathology. Dig Endosc 2011;23:319–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Fuyuno Y, Moriyama T, Kumagae Y et al. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome with a major duodenal papillary adenocarcinoma. Intern Med 2017;56:2805–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Nagata J, Kijima H, Hasumi K et al. Adenocarcinoma and multiple adenomas of the large intestine, associated with Cronkhite-Canada syndrome. Dig Liver Dis 2003;35:434–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Maruno T, Kikuyama M. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome associated with sigmoid colon cancer. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011;9:e118–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Yashiro M, Kobayashi H, Kubo N et al. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome containing colon cancer and serrated adenoma lesions. Digestion 2004;69:57–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Watari J, Sakurai J, Morita T et al. A case of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome complicated by McKittrick-Wheelock syndrome associated with advanced villous adenocarcinoma. Gastrointest Endosc 2011;73:624–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Liu S, Ruan GC, You Y et al. A striking flail chest: a rare manifestation of intestinal disease. Intest Res 2019;17:155–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Naoshima-Ishibashi Y, Murofushi T. A case of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome with vestibular disturbances. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2004;261:558–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Sampson JE, Harmon ML, Cushman M et al. Corticosteroid-responsive Cronkhite-Canada syndrome complicated by thrombosis. Dig Dis Sci 2007;52:1137–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Nemade NL, Shukla UB, Wagholikar GD. Cronkhite Canada syndrome complicated by pulmonary embolism: a case report. Int J Surg Case Rep 2017;30:17–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Chalk JB, Georgk J, McCOMBE PA et al. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome associated with peripheral neuropathy. Aust N Z J Med 1991;21:379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Lo YL, Lim KH, Cheng XM et al. Steroid responsive mononeuritis multiplex in the Cronkhite-Canada syndrome. Front Neurol 2016;7:207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Marinoni B, Tontini GE, Elli L et al. Major duodenal papilla prolapse in Cronkhite-Canada syndrome. Endoscopy 2019;51:E81–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Yasuda T, Ueda T, Matsumoto I et al. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome presenting as recurrent severe acute pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc 2008;67:570–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Wijekoon N, Samarasinghe M, Dalpatadu U et al. Proctocolectomy for persistent haematochezia in a patient with Cronkhite-Canada syndrome. J Surg Case Rep 2012;2012:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Chakrabarti S. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome (CCS): a rare case report. J Clin Diagn Res 2015;9:OD08–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Zhu X, Shi H, Zhou X et al. A case of recurrent Cronkhite-Canada syndrome containing colon cancer. Int Surg 2015;100:402–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Martinek J, Chvatalova T, Zavada F et al. A fulminant course of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome. Endoscopy 2010;42:E350–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Taylor SA, Kelly J, Loomes DE. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: sustained clinical response with anti-TNF therapy. Case Rep Med 2018;2018:1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Ohmiya N, Nakamura M, Yamamura T et al. Steroid-resistant Cronkhite-Canada syndrome successfully treated by cyclosporine and azathioprine. J Clin Gastroenterol 2014;48:463–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Yamakawa K, Yoshino T, Watanabe K et al. Effectiveness of cyclosporine as a treatment for steroid-resistant Cronkhite-Canada syndrome; two case reports. BMC Gastroenterol 2016;16:123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Langevin C, Chapdelaine H, Picard JM et al. Sirolimus in refractory Cronkhite-Canada syndrome and focus on standard treatment. J Invest Med High Impact Case Rep 2018;6:232470961876589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Hizawa K, Nakamori M, Yao T et al. A case of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome with colorectal adenomas: effect of the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug Sulindac. Am J Gastroenterol 2007;102:1831–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Schulte S, Kütting F, Mertens J et al. Case report of patient with a Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: sustained remission after treatment with corticosteroids and mesalazine. BMC Gastroenterol 2019;19:36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Takakura M, Adachi H, Tsuchihashi N et al. A case of Cronkhite–Canada syndrome markedly improved with mesalazine therapy. Dig Endosc 2004;16:74–8. [Google Scholar]

- 88. Kojima E, Tomita A, Matsumura M et al. Magnifying the endoscopic appearance of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome. Gastrointest Endosc 2009;70:1242–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Lipin SP, Paul B, Nazimudeen E et al. Case of Cronkhite Canada syndrome shows improvement with enteral supplements. J Assoc Physicians India 2012;60:61–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Nakayama M, Muta H, Somada S et al. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome associated with schizophrenia. Intern Med 2007;46:175–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Hanzawa M, Yoshikawa N, Tezuka T et al. Surgical treatment of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome associated with protein-losing enteropathy: report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum 1998;41:932–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Samalavicius NE, Lunevicius R, Klimovskij M et al. Subtotal colectomy for severe protein-losing enteropathy associated with Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: a case report. Colorectal Dis 2013;15:e164–5–e165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]