Abstract

Background and objectives

The Covid-19 pandemic has put healthcare professionals around the world in an unprecedented challenge. This may cause some emotional difficulties and mental health problems. The aim of the present study was to analyze the emotional status among the health care workers form the Hospital of Igualada (Barcelona), while they were facing with Covid-19 in one of the most affected regions in all of Europe.

Patients and methods

A total of 395 participants were included in the study. A cross-sectional assessment was carried out between the months of March and April. Information about anxiety, depression, and stress was gathered. We also collected demographic data and concerning potentially stressful factors.

Results

A significant proportion of professionals reported symptoms of anxiety (31.4%) and depression (12.2%) from moderate to severe intensity. Symptoms of acute stress were reported by 14.5% of participants. We performed a regression analysis, which explained the 30% of the variance associated with the degree of emotional distress (R² = 0.30). The final model reveals that females (or young males), who are working in the frontline as nursing assistants, caretakers or radiology technicians, with the uncertainty of a possible infection, the perception of inadequate protection measures and having experienced the death of a close person by Covid-19, showed a heightened risk of experiencing psychological distress.

Conclusions

Coping with the Covid-19 pandemic caused a significant impact on emotional status of healthcare workers involved in this study.

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, Novel coronavirus, Anxiety, Depression, Mental health

Abstract

Antecedentes y objetivo

La actual pandemia de Covid-19 ha puesto a los profesionales sanitarios de todo el mundo ante un desafío sin precedentes. Esto les ha podido causarles dificultades emocionales y problemas de salud mental. El objetivo del presente estudio fue analizar el estado emocional de los trabajadores del Hospital de Igualada (Barcelona), mientras se enfrentaban a uno de los focos de contagio más importantes de Europa.

Pacientes y métodos

Se incluyó a un total de 395 trabajadores. Se realizó una evaluación transversal entre los meses de marzo y abril. Se recogió información sobre síntomas de ansiedad, depresión, estrés. También se recogieron datos demográficos y sobre factores potencialmente estresantes.

Resultados

Un porcentaje significativo de profesionales reportó síntomas de ansiedad (71.6%) y depresión (60.3%). El 14.5% informó de síntomas de estrés agudo. Se realizó un análisis de regresión que explicó el 30% de la variancia asociada al nivel de malestar emocional (R² = 0.30). Los factores de riesgo asociados a mayor malestar psicológico fueron el hecho de ser mujer (o hombre joven), trabajar como auxiliar de enfermería, celador o técnico de radiología, estar en contacto directo con pacientes Covid-19, no haber realizado la PCR, tener la sensación de no contar con los elementos de protección personales y haber experimentado la muerte de una persona cercana por Covid-19.

Conclusiones

El afrontamiento inicial de la situación de crisis asociada a la pandemia del Covid-19, tuvo un importante impacto emocional en los profesionales sanitarios analizados.

Palabras clave: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, Nuevo coronavirus, Ansiedad, Depresión, Salud mental

Introduction

The 2019 novel coronavirus disease (Covid-19) was first diagnosed in December 2019 in the city of Wuhan (Hubei, China).1 On 11th March the outbreak of the disease was classified as a pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO), after the number of cases detected globally soared, including major outbreaks in several countries of the world such as Iran, Italy or South Korea. At the end of May, there were 5,370,375 confirmed cases worldwide, as well as 344,454 people who had died from this disease.2 Faced with this new pandemic, an increase in symptoms of anxiety, depression and stress has been observed in the general population and, especially, in healthcare workers.3, 4

Spain has not been an exception. Since the first patient was known on 31 st January, the number of infections was increasing progressively throughout the entire territory, until the state of alarm was decreed on 14th March. In these early days, the psychological impact of the pandemic was already beginning to be felt, especially among women, young people, and people with chronic illnesses.5, 6

Days prior to the state of alarm (specifically, on 12th March), the lockdown of the Conca de Òdena region (Catalonia) was decreed, following an important outbreak of Covid-19. This exceptional lockdown lasted until 6th April. Thus, this region, made up of 4 municipalities (Igualada, Òdena, Santa Margarida de Montbuí and Vilanova del Camí) and some 70,000 inhabitants, became one of the epicentres of the pandemic in Spain and Europe. Specifically, the mortality rate associated with Covid-19 in this region exceeded that of Lombardy, doubled that of Madrid and was 10 times higher than that of the rest of Catalonia.7 The first positive cases were reported on 9th March, and on 20th March there were already 24 deaths and 209 positives. Of these, 91 cases were health workers, indicating the high level of spread of the virus among this group from the outset.8

To cope with this major Covid-19 outbreak in Conca de Òdena, the Igualada Hospital, a primary hospital with about 1100 workers, had to quickly adapt to this unfavourable situation. As it happened later in other Spanish hospitals, the professionals of Igualada Hospital started to be under a considerable physical and psychological pressure. Previous studies, especially carried out in China, already suggested that health professionals were especially vulnerable to psychological distress derived from the pandemic.4, 9 Some factors that explain this greater vulnerability are exposure to possible infection, concern about infecting loved ones, the feeling of lack of protection means, long work shifts, or the pressure associated with making decisions with ethical implications.10, 11

This study aimed to analyse the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on the psychological well-being of Igualada Hospital workers during the first phase of containment of the pandemic (March 2020).

Methods

Study sample

An e-mail with information about the purpose of the study was sent to all the workers of the Igualada Hospital (approximately 1100). The workers who were active at the time of the evaluation (between March and April 2020) were subsequently identified in a cross-sectional manner and given a booklet with the information to be provided, in addition to the informed consent. To do this, some of the investigators in the present study went to the workplace of each of the participants. The initial sample consisted of 470 workers (42.73% of all workers). To be eligible, participants had to be working in any of the Hospital departments, belong to any job category, understand the purpose of the study, and sign the informed consent. A total of 407 professionals met these inclusion criteria. Twelve participants were discarded due to errors and/or incomplete data, with which the final study sample was 395 professionals (35.91% of the total workers at the Igualada Hospital). Therefore, the number of workers available at the time of the study determined the sample size.

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the sample.

Table 1.

Demographic data and characteristics of the sample.

| Variable | Average (SD) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 40.20 (11.46) |

| Self-reported measures | |

| HARS | 11.92 (8.63) |

| MADRS | 9.93 (7.37) |

| List of ASD symptoms | 4.06 (4.03) |

| DASS-21_Depression | 3.05 (3.5) |

| DASS-21_Anxiety | 3.38 (3.78) |

| DASS-21_Stress | 6.29 (4.6) |

| Variable | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender (men) | 104 (26.4) |

| Employment category | |

| Group 1 | 106 (26.9) |

| Group 2 | 145 (36.8) |

| Group number 3 | 100 (25.4) |

| Group 4 | 34 (10.9) |

| Work and health stressors (yes) | |

| Work with Covid-19 patients | 365 (91.0) |

| PCR has been carried out | 107 (26.7) |

| Positive PCR | 360 (89.8) |

| Covid-19 symptoms | 223 (55.6) |

| Total or partial work in ICU | 114 (28.4) |

| Sense of lack of protection | 147 (36.7) |

| Family stressors (yes) | |

| Risk person/s at home | 89 (22.2) |

| Children at home | 156 (38.9) |

| Lockdown | 211 (52.6) |

| Death of a close person by Covid-19 | 83 (20.7) |

DASS-21: Depression Anxiety Stress Scales; SD: standard deviation; Group 1: nursing aides, orderlies, radiology technicians; Group 2: nursing professionals; Group 3: medical personnel; Group 4: administrative, security, cleaning, systems, warehouse and managerial staff; HARS: Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale; MADRS: Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale; PCR: polymerase chain reaction test; ASD: acute stress disorder; ICU: intensive care unit.

Methods

The present study arose from the collaboration between the Orthopaedic Surgery and Traumatology Department (COT) and the Mental Health Service of the Igualada Hospital (Consorci Sanitari de l'Anoia, Catalunya, Spain). Both services worked on the design of the study. The COT department was in charge of recruiting the sample and providing the information about the study. Later, both services collaborated in the interpretation, analysis and writing of results.

Participation was voluntary and anonymous. A booklet was provided to each of the participants with the questionnaires (see subsection "Instruments"). Finally, they were asked for a telephone number so that they could be contacted in the event that their results were susceptible to a more detailed assessment by the Mental Health Service.

The methods and procedure were approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge (Barcelona; code PR192/20). The study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations of the Declaration of Helsinki for research with humans.

Instruments

Different psychometric instruments were used to assess psychological distress and symptoms of anxiety and depression.

The DASS-21 (Depression Anxiety Stress Scales) 12 is a self-report instrument that assesses the intensity/frequency of 21 symptoms associated with a negative emotional state, during the previous 2 weeks. It consists of 3 subscales: (i) depression, which evaluates hopelessness, low self-esteem, and low positive affect; (ii) anxiety, which assesses physiological arousal, musculoskeletal symptoms, and subjective feelings of anxiety; (iii) stress, which assesses tension, agitation, and negative affect. DASS-21 has been used in both clinical and non-clinical samples.13 Previous data suggest that it is a useful instrument for the screening of mental disorders, since it has good discriminant validity.14 It has been used previously to assess the emotional impact associated with Covid-19 in the general population15 and in health workers.16

The Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HARS) and the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS)17 were also used to assess anxiety and depressive symptoms. The HARS consists of 14 items that contemplate different symptoms of psychic and somatic anxiety. Each item is assessed from 0 to 4 according to its degree of intensity, with the total score of the test ranging from 0 to 56 points. The MADRS consists of 10 items that assess depressive symptoms in adults (e.g., sleep difficulties, concentration, pessimism). Each item is assessed from 0 to 6, with the total score of the test ranging from 0 to 60 points. In both instruments, a higher score indicates greater severity of symptoms.

Although the HARS and MADRS are designed to be used in a hetero-applied way (that is, by an evaluator), taking into account the exceptional circumstances and the social distancing required at the moment, both instruments were used in a self-report way. Therefore, both tests were answered by the participants as a list of symptoms to be graded according to the perceived intensity. To facilitate understanding by the participants, the investigators clearly explained the procedure to follow in order to answer them. It should be noted that, in the case of the MADRS, there is a self-report version, similar to the original version, with equivalent characteristics.18, 19

An ad hoc questionnaire consisting of a list of 18 symptoms associated with acute stress disorder (ASD) was designed.20 This disorder is defined as an acute stress reaction that occurs as a result of some traumatic event and starts within 3 days to 4 weeks after the event. The typical symptoms of ASD are the re-experiencing of the traumatic event, the avoidance of situations that generate distress associated with the traumatic event, dissociation, or physiological hyperarousal. Previous work has suggested that ASD, despite being a self-limiting disorder in many cases, could be a predictor of post-traumatic stress disorder.21 In this questionnaire, the participants answered based on the presence or absence of ASD symptoms, in addition to whether they considered they had been exposed to any traumatic experience.

Finally, some questions on demographic data were also included, as well as on stressors potentially related to Covid-19. In the first section, data such as age and sex, and data on the employment situation were collected. The second included questions about potentially stressful factors for the participants, such as having suffered symptoms, feeling unprotected or working in the ICU. The answers in this section were categorized as yes or no (see Table 1).

Statistical analysis

Firstly, the employment position within the Igualada Hospital was recoded taking into account: (i) the level of direct contact with Covid-19 patients and (ii) the number of participants in each subgroup (so that the groups could be comparable). In this way, we worked with four groups: (a) Group 1: nurse's aides, orderlies, radiology technicians; (b) Group 2: nursing professionals; (c) Group 3: medical personnel; (d) Group 4: administrative, security, cleaning, systems, warehouse and managerial personnel.

For the descriptive analysis, the number and frequency were reported for categorical variables, as well as the mean and standard deviation for continuous variables (see Table 1).

For the measures of psychological distress and symptoms, case frequency was calculated from a range of severity to give the data clinical significance. For HARS, the percentage of cases with symptoms of anxiety (≥ 6) and moderate-severe anxiety (≥ 15) was calculated. In the case of MADRS, the percentage of cases with symptoms of depression (≥ 7) and moderate-severe depression (≥ 20) was calculated. For the ASD questionnaire, the percentage of cases with more than 9 positive symptoms was calculated.

Since all instruments were self-reported, the relationship of each instrument (HARS, MADRS and ASD questionnaire) to the total DASS-21 score was analysed. This analysis was carried out using the Spearman correlation coefficient, since the variables did not follow a normal distribution.

To analyse the impact on psychological well-being of some potentially stressful factors, an analysis of variance (ANOVA; Table 2 ) was carried out with the employment category (Group 1, Group 2, Group 3, Group 4), the variables associated with occupational and health stressors (yes, no), and family stressors (yes, no) as within-subject factors and the DASS-21 score (total score) as an between-subject factor. Since the DASS-21 score did not follow a normal distribution (negative skewness), we carried out a square root transformation. In this way, asymmetry and kurtosis remained within the normal ranges (−0.5 to 0.5).

Table 2.

Factors associated with the level of psychological distress (DASS-21).

| Variable | Average (SD) | F | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Employment category | |||

| Medical personnel | 2.53 (1.41) | 11.73*** | [2.25, 2.80] |

| DUE | 3.18 (1.46) | [2.94, 3.42] | |

| Nursing aide, orderly, technician radiology | 3.79 (1.67) | [3.47, 4.12] | |

| Other | 3.19 (1.66) | [2.68, 3.70] | |

| Works with Covid-19 patients | |||

| Yes | 3.24 (1.61) | 6.82** | [3.07, 3.40] |

| No | 2.44 (1.29) | [1.95, 2.93] | |

| PCR has been carried out | |||

| Yes | 3.08 (1.49) | 1.30 | [2.79, 3.37] |

| No | 3.23 (1.63) | [3.04, 3.42] | |

| Positive PCR | |||

| Yes | 3.16 (1.58) | 1.34 | [2.99, 3.32] |

| No | 3.48 (1.73) | [2.89, 4.08] | |

| Covid-19 symptoms | |||

| Yes | 3.57 (1.57) | 32.25*** | [3.36, 3.78] |

| No | 2.68 (1.49) | [2.46, 2.91] | |

| Total or partial work in ICU | |||

| Yes | 3.14 (1.51) | 0.126 | [2.86, 3.42] |

| No | 3.21 (1.64) | [3.01, 3.40] | |

| Sense of lack of protection | |||

| Yes | 3.68 (1.66) | 23.64*** | [3.41, 3.95] |

| No | 2.89 (1.48) | [2.71, 3.08] | |

| Risk person/s at home | |||

| Yes | 3.34 (1.59) | 0.99 | [3.00, 3.67] |

| No | 3.14 (1.60) | [2.96, 3.32] | |

| Children at home | |||

| Yes | 3.40 (1.61) | 4.51* | [3.14, 3.65] |

| No | 3.05 (1.58) | [2.85, 3.25] | |

| Lockdown | |||

| Yes | 3.34 (1.58) | 3.85 | [3.12, 3.56] |

| No | 3.02 (1.61) | [2.79, 3.25] | |

| Death of a close person by Covid-19 | |||

| Yes | 3.73 (1.76) | 12.61*** | [3.35, 4.12] |

| No | 3.04 (1.52) | [2.87, 3.21] | |

DASS-21: Depression Anxiety Stress Scales; SD: standard deviation; F: ANOVA statistic; CI: confidence interval; PCR: polymerase chain reaction test; ICU: intensive care unit.

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

p < 0.001.

Finally, a linear regression analysis was carried out. Gender and age were included as predictors of the model in a first block, and work category, work and health stressors, and family stressors in a second block. The dependent variable was the level of psychological distress (DASS-21 total score).

Results

The participants in the study were mostly women (73.6%), and the age range was between 18 and 64 years (see Table 1). The mean age was similar in men and women (women: 39.83 ± 11 years; male: 41.24 ± 12.5 years; F (1, 392) = 1.16; p = 0.28). The measures used to assess symptoms of anxiety, depression and acute stress (HARS, MADRS and list of ASD symptoms) showed high correlations with the total DASS-21 score (r = 0.83; r = 0.79; r = 0.79, respectively; all with a statistical significance level of p < 0.001). These results suggest that all the measures evaluated similar constructs, even though some of them were not designed to be used as self-reports.

The level of emotional distress was more severe in women than in men, as indicated by the higher scores on the DASS-21 in female workers (3.39 ± 1.55; 2.58 ± 1.54; F (392.1) = 20.69; p < 0.001). Of the 395 participants in the study, 71.6% (n = 287) of them showed anxiety symptoms, of which 31.4% (n = 126) had moderate to severe anxiety intensity according to HARS. Regarding the depressive symptoms evaluated with the MADRS, 60.3% (n = 242) of the participants reported symptoms of depression, of which 12.2% (n = 49) showed scores compatible with moderate to severe depression (and 48.1% with mild depression, n = 193). On the other hand, 14.5% (n = 59) of workers showed symptoms of ASD according to the ad hoc symptom list prepared.

The participants in the study showed different levels of psychological distress depending on the professional category to which they belonged (Table 2). Workers in Group 1 (nursing aides, orderlies, and radiology technicians) showed higher scores on the DASS-21, followed by Group 2 (made up of graduates in nursing). The rest of the professionals (Groups 3 and 4) were those who showed the least emotional impact, not observing differences between them (Group 3 vs. Group 4).

The presence (versus the absence) of some work and health stressors (direct work with Covid-19 patients, experiencing symptoms, feeling unprotected) was associated with higher levels of psychological distress. On the other hand, having minors at home, having been under lockdown, or having suffered the recent death of a close person due to Covid-19 were the family stressors that were associated with higher levels of emotional distress in our sample (Table 2).

Regarding the regression analysis, a significant model was obtained that explains 24% of the change in the variance in psychological distress (R² = 0.24, F (12.377) = 9.82, p < 0.001). Subsequently, possible interactions between the model's predictors were sought. Two significant interactions were found that increased the percentage of variance explained by the model (R² = 0.30, F (15.373) = 10.56, p < 0.001). To evaluate which of the two models obtained a better data fit, we use the ANOVA function, which allows us to compare nested models. We found that both models were significantly different (F (2375) = 12.43, p < 0.001), therefore, the model that included interactions presents a better data fit.

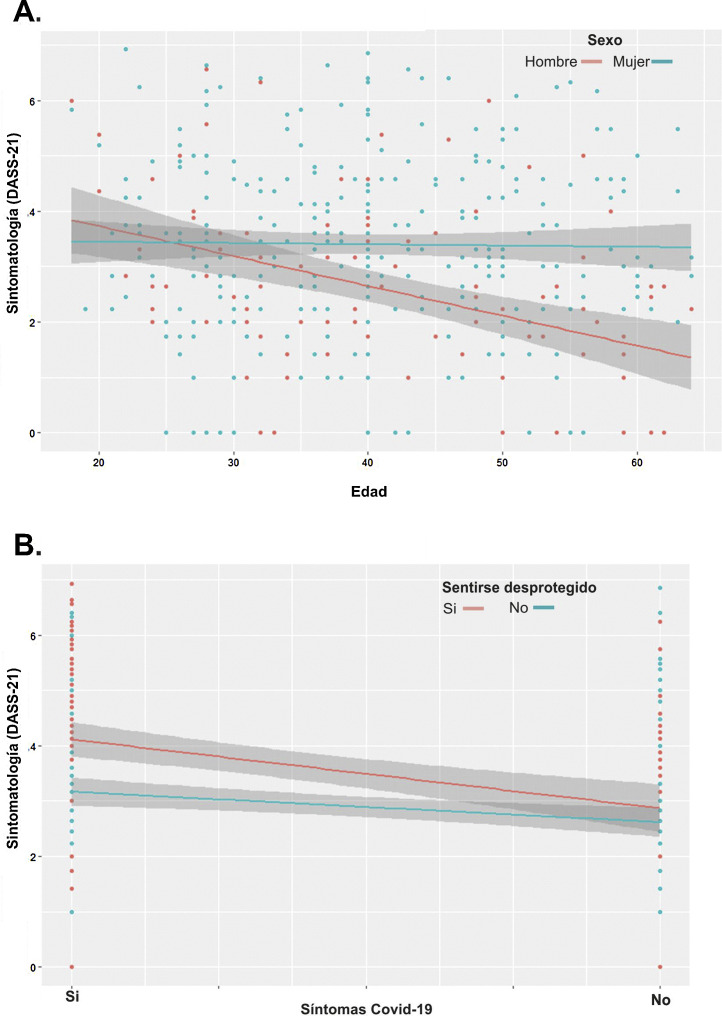

Table 3 shows the statistically significant predictors of the model. Being a woman (or young man), from Group 1 (nursing aides, orderlies, radiology technicians), working in direct contact with Covid-19 patients, not having carried out a PCR, the perception of not having the necessary protection elements to prevent infection (especially when experiencing symptoms), and having experienced the death of a close person from Covid-19, were risk factors for a greater degree of emotional distress in the study sample. Fig. 1 shows the interactions.

Table 3.

Linear regression model.

| B | SE B | t | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | ||||

| Intercept | 2.55 | 0.43 | 5.93*** | [1.71, 3.40] |

| Age | −0.01 | 0.00 | −2.70** | [−0.03, −0.00] |

| Sex | 0.78 | 0.17 | 4.43*** | [0.43, 1.13] |

| Model 2 | ||||

| Intercept | 12.01 | 1.41 | 8.47*** | [9.22, 14.79] |

| Age | −0.10 | 0.02 | −4.42*** | [−0.14, −0.05] |

| Sex | −1.36 | 0.57 | −2.39* | [−2.49, −0.24] |

| Employment category | −0.17 | 0.06 | −2.80** | [−0.30, −0.05] |

| Direct contact Covid-19 | −0.82 | 0.28 | −2.90** | [−1.37, −0.26] |

| PCR test | 0.46 | 0.17 | 2.66** | [0.12, 0.80] |

| Positive PCR | 0.15 | 0.25 | 0.62 | [−0.34, 0.66] |

| Covid-19 symptoms | −2.16 | 0.51 | −4.22*** | [−3.17, −1.15] |

| Lack of protection | −1.68 | 0.43 | −3.82*** | [−2.54, −0.81] |

| Work in ICU | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.81 | [−0.09, 0.21] |

| Risk person at home | 0.03 | 0.17 | 0.17 | [−0.30, 0.36] |

| Children at home | −0.28 | 0.14 | −1.97* | [−0.56, −0.00] |

| Lockdown | −0.21 | 0.14 | −1.50 | [−0.49, 0.06] |

| Close death from Covid-19 | −0.44 | 0.17 | −2.52* | [−0.78, −0.09] |

| Age × gender | 0.05 | 0.01 | 3.83*** | [0.02, 0.07] |

| Symptoms Covid-19 × lack of protection | 0.81 | 0.29 | 2.72** | [0.22, 1.40] |

B = non-standardized coefficient. Block 1: sex and age were entered, R² = 0.07, F (2.390) = 14.18, p < 0.001. Block 2: the rest of the variables and the interactions were entered, R² = 0.30, F (15.373) = 10.56, p < 0.001.

CI: confidence interval; PCR: polymerase chain reaction test; SE: standard error; ICU: intensive care unit.

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

p < 0.001.

Fig. 1.

Interactions found in the regression model. (A) Age was influenced by sex; the older the men, the fewer the symptoms, while women remained constant. (B) The presence of Covid-19 symptoms was influenced by the perception of lack of protection; the workers who had suffered symptoms, and also had the feeling of not having the necessary protective elements, showed greater psychological distress (compared to those who had not had symptoms).

Discussion

The professionals of the Igualada Hospital have had to face one of the epicentres of the Covid-19 pandemic in Europe. The fact that it was one of the first outbreaks in Spain meant that workers were initially exposed to greater uncertainty, a delay in diagnostic tests and a greater sense of lack of personal protection measures. In addition to the work overload that this entire process has implied, many of the professionals have had to deal with potentially traumatic events, such as the death of patients or decision-making in a context of limited therapeutic options.

The present study suggests that the professionals of the Igualada Hospital have suffered a high emotional impact as a result of the above. The results obtained indicate that 71.6% of the professionals suffered anxiety symptoms and 60.3% depressive symptoms at the time of the evaluation. In addition, a significant percentage had clinically significant symptoms of moderate-severe intensity anxiety and depression (31.4% and 12.2% respectively). These results are consistent with previous studies, indicating high levels of anxiety and depression among health professionals in the early stages of the crisis.3 For example, in a study with 1257 workers from 34 hospitals in China, the presence of depressive symptoms was observed in 50.4% of the participants and anxiety symptoms in 44.6%.22 Interestingly, this study also shows that the emotional distress in the Hubei area hospitals (especially affected by the pandemic) was greater than in the hospitals that were outside that area. In this sense, the data obtained in our study could indicate a similar impact on the Igualada Hospital personnel when compared to that of other hospitals in charge of caring for the population in areas especially affected by the pandemic.

Consistently, 14.6% of participants reported symptoms of acute stress associated with having experienced a traumatic event. This subgroup of professionals was experiencing symptoms such as physiological hyperarousal, the presence of distressing dreams, avoidance, and isolation, or re-experiencing the trauma. In addition, they would have a higher risk of suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder (compared to the rest of the professionals). These data would be consistent, at least in part, with previous studies that have associated the levels of distress of health professionals with the presence of sleep disturbances and with greater social isolation.23

Another relevant data was that a greater degree of emotional distress was observed in the professionals of Group 1 and Group 2 (nursing aides, orderlies, radiology technicians, nursing staff). These data could be explained by the fact that these groups may have suffered a greater exposure to infection, by spending more time in direct contact with patients affected by Covid-19. In this sense, previous studies suggest that the nursing group, which was in the "front line" of action against Covid-19, was the group that experienced more symptoms of anxiety and depression in the Wuhan area.22 On the other hand, this finding could also have to do with the fact that these two groups of professionals made up the majority of the participants in this study, thus being over-represented with respect to the rest of the professionals.

In the work context, it was also observed how some variables were associated with a greater degree of emotional distress. In particular, those professionals who worked directly with positive Covid-19 patients, who had experienced symptoms or who felt they did not have access to personal protective measures reported higher DASS-21 scores than workers who had not experienced these stressors. On the other hand, on a personal level, having children at home, having been under lockdown or having suffered the recent death of a close person due to Covid-19 were the family stressors that were associated with higher levels of emotional distress in our sample. Along these lines, a greater degree of emotional distress was also observed in women (in relation to men). These results reinforce previous findings that indicate higher levels of anxiety and depression in female workers,22, 24 as well as the relevance of different work, health, and family variables in coping with these symptoms.24

Finally, a regression analysis was carried out to assess the factors that best predicted emotional distress in the professionals of the Igualada Hospital. Interestingly, a greater risk of psychological distress was observed in young women and men, from Group 1 (nursing aide, orderly or radiology technician), who had been highly exposed to Covid-19, and who did not know if they were infected and did not have the feeling of having the necessary protection elements (especially when they had symptoms). Having experienced the death by Covid-19 of a close person was also a predictor variable. These results are partially consistent with previous studies. For example, a study of 5062 healthcare workers in Wuhan, Zhu et al.24 observed that gender (female), having a chronic disease, having a history of mental disorder and concern for the health of a relative were factors that predicted a greater number of anxiety and depression symptoms. On the contrary, having the necessary protection elements appeared as a protective factor. In another study, Lai et al.22 found that exposure to infection predicted higher levels of depression, anxiety, and insomnia.

The interaction that we found between sex and age in our sample is in line with previous studies in the general population that indicate a greater risk of suffering from anxiety and depression symptoms in young people.6 They also support previous studies that suggest that men may suffer more long-term psychological damage in situations of health crisis.16 One possible explanation would be that men tend to identify or experience distress later than women (something that would not happen in younger men). On the other hand, the interaction that was found between feeling unprotected and having symptoms (both were the two most robust predictors in the model) suggests an important role of the uncertainty of not knowing if one is infected on psychological well-being.

The present study has some important limitations. First, the use of some instruments (HARS, MADRS) as self-reported assessments could lead to a bias in the results. Although self-reported information should not replace hetero-reported information,25 the high correlation observed between these instruments and the DASS-21 could justify their use, taking into account the exceptional social distancing measures. Second, the fact that the data have been collected in a cross-sectional manner, in an initial phase, limits the generalization of the results. In this sense, in previous adverse situations such as that associated with SARS, it was observed that the initial effects on mental health can persist over time in health professionals.16 Something similar has been observed in the general population in the current situation.15 Future studies should consider a longitudinal evaluation of health professionals, in order to better assess the real impact of the pandemic on their mental health.26 Third, the fact that the study sample consisted only of active workers limits the statistical power of the results and could represent a possible bias in their interpretation. Finally, our study did not collect data on length of time in the company or on medical history, which could have improved the interpretation of the results.

The results obtained could have important implications at the clinical and health policy level. On the one hand, they suggest that health professionals are a particularly vulnerable group in the face of the Covid-19 pandemic, showing a level of psychological distress much higher than that of the general population.6 This information could be useful for the professionals themselves, who should pay attention to their mental health, monitoring their stress reactions and seeking support if necessary. For their part, hospitals should develop intervention plans for those professionals who require it. In this sense, the possibility of being able to consult with a mental health specialist should be ensured,27 as is already happening in different parts of the world.28 Finally, given the possibility of a future outbreak, the data from this work could be useful in establishing groups of workers at greater risk of emotional distress.

In conclusion, our study indicates that the professionals at the Igualada Hospital suffered a significant degree of psychological distress while facing the first stages of the Covid-19 pandemic. The identification of some variables associated with an increased risk of emotional distress can help to implement specific interventions on the most vulnerable groups.

Funding

CS has been awarded with a grant by the Chilean Government, through the Becas-Chile fellowship program of the National Agency for Research and Development (ANID), reference 2018-72190624.

Conflict of interests

None.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank all the workers of the Consorci Sanitari de l'Anoia, especially those who participated in this study. We wish to thank Dr. Marta Banqué for her support in data analysis.

Footnotes

Please cite this article as: Erquicia J, Valls L, Barja A, Gil S, Miquel J, Leal-Blanquet J, et al. Impacto emocional de la pandemia de Covid-19 en los trabajadores sanitarios de uno de los focos de contagio más importantes de Europa. Med Clin (Barc). 2020;155:434–440.

References

- 1.Harapan H., Itoh N., Yufika A., Winardi W., Keam S., Te H. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): A literature review. J Infect Public Health. 2020;13:667–673. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2020.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard, https://covid19.who.int/; 2020 [consultada el 26 de mayo de 2020].

- 3.Rajkumar R.P. COVID-19 and mental health: A review of the existing literature. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;52 doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tan B.Y.Q., Chew N.W.S., Lee G.K.H., Jing M., Goh Y., Yeo L.L.L. Psychological Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Health Care Workers in Singapore. Ann Intern Med. 2020;20:1083. doi: 10.7326/M20-1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ozamiz-etxebarria N., Dosil-santamaria M., Picaza-gorrochategui M., Idoiaga-mondragon N. Stress, anxiety, and depression levels in the initial stage of the COVID-19 outbreak in a population sample in the northern Spain. Cad Saude Publica. 2020;36:1–9. doi: 10.1590/0102-311X00054020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rodrígez-Rey R., Garrido-Hernansaiz H., Collado S. Psychological Impact of COVID-19 in Spain: early data report. Pyscho Trauma. 2020 doi: 10.1037/tra0000943. in press. https://doi.org/ 10.1037/tra0000943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ajuntament d’Igualada. Notícies. http://www.igualada.cat/; 2020 [consultada el 26 de mayo de 2020].

- 8.Agència de Qualitat i Avaluació Sanitàries de Catalunya (AQuAS). Dades actualitzades SARS-CoV-2, http://aquas.gencat.cat/ca/actualitat/ultimes-dades-coronavirus/; 2020 [consultada el 26 de mayo de 2020].

- 9.Wu P.E., Styra R., Gold W.L. Mitigating the psychological effects of COVID-19 on health care workers. Can Med Assoc J. 2020;192:459–460. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.200519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brooks S.K., Webster R.K., Smith L.E., Woodland L., Wessely S., Greenberg N. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395:912–920. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greenberg N., Docherty M., Gnanapragasam S., Wessely S. Managing mental health challenges faced by healthcare workers during covid-19 pandemic. BMJ. 2020;368:1211. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bados A., Solanas A., Andrés R. Psychometric properties of the Spanish version of Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scales (DASS) Psicothema. 2005:679–683. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vega D., Torrubia R., Soto À, Ribas J., Soler J., Pascual J.C. Exploring the relationship between non suicidal self-injury and borderline personality traits in young adults. Psychiatry Res. 2017;256:403–411. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mitchell M.C., Burns N.R., Dorstyn D.S. Screening for depression and anxiety in spinal cord injury with DASS-21. Spinal Cord. 2008;46:547–551. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3102154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang C., Pan R., Wan X., Tan Y., Xu L., McIntyre R.S. A longitudinal study on the mental health of general population during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Brain Behav Immun. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.028. S0889-1591(20)30511-0. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mcalonan G.M., Lee A.M., Cheung V., Cheung C., Tsang K.W., Sham P.C. Immediate and Sustained Psychological Impact of an Emerging Infectious Disease Outbreak on Health Care Workers. CMAJ. 2007;52:241–247. doi: 10.1177/070674370705200406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lobo A., Chamorro L., Luque A., Dal-Ré R., Badia X., Baró E. Validación de las versiones en español de la Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale y la Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale para la evaluación de la depresión y de la ansiedad. Med Clin. 2002;13:493–499. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7753(02)72429-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fantino B., Moore N. The self-reported Montgomery-Åsberg depression rating scale is a useful evaluative tool in major depressive disorder. BMC Psychiatry. 2009;9:26. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-9-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Backlund L.G., Löfvander M., Svanborg P., Asberg M. A comparison between the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) and the self-rating version of the Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) J Affect Disord. 2001;64:203–216. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(00)00242-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.APA . 2013. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: Dsm-5. Amer Psychiatric Pub Incorporated. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cardeña E., Carlson E. Acute Stress Disorder Revisited. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2011;7:245–267. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032210-104502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lai J., Ma S., Wang Y., Cai Z., Hu J., Wei N. Factors Associated With Mental Health Outcomes Among Health Care Workers Exposed to Coronavirus Disease 2019. JAMA Netw open. 2020;3 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xiao H., Zhang Y., Kong D., Li S., Yang N. The Effects of Social Support on Sleep Quality of Medical Staff Treating Patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in January and February 2020 in China. Med Sci Monit. 2020;26 doi: 10.12659/MSM.923549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhu Z., Xu S., Wang H., Liu Z., Wu J., Li G. 2020. COVID-19 in Wuhan: Immediate Psychological Impact on 5062 Health Workers. medRxiv. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Uher R., Perlis R.H., Placentino A., Dernovšek M.Z., Henigsberg N., Mors O. Self-report and clinician-rated measures of depression severity: Can one replace the other? Depress Anxiety. 2012;29:1043–1049. doi: 10.1002/da.21993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holmes E.A., O’connor R.C., Perry H., Tracey I., Wessely S., Arseneault L. Position Paper Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: a call for action for mental health science. Lancet. 2020;7:547–560. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30168-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pfefferbaum B., North C.S. Mental Health and the Covid-19 Pandemic. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2008017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen Q., Liang M., Li Y., Guo J., Fei D., Wang L. Mental health care for medical staff in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet. 2020;7:e15–e16. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30078-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]