Abstract

Background & Aims

Patients affected by hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) represent a vulnerable population during the COVID-19 pandemic and may suffer from altered allocation of healthcare resources. The aim of this study was to determine the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the management of patients with HCC within 6 referral centres in the metropolitan area of Paris, France.

Methods

We performed a multicentre, retrospective, cross-sectional study on the management of patients with HCC during the first 6 weeks of the COVID-19 pandemic (exposed group), compared with the same period in 2019 (unexposed group). We included all patients discussed in multidisciplinary tumour board (MTB) meetings and/or patients undergoing a radiological or surgical programmed procedure during the study period, with curative or palliative intent. Endpoints were the number of patients with a modification in the treatment strategy, or a delay in decision-to-treat.

Results

After screening, n = 670 patients were included (n = 293 exposed to COVID, n = 377 unexposed to COVID). Fewer patients with HCC presented to the MTB in 2020 (p = 0.034) and fewer had a first diagnosis of HCC (n = 104 exposed to COVID, n = 143 unexposed to COVID, p = 0.083). Treatment strategy was modified in 13.1% of patients, with no differences between the 2 periods. Nevertheless, 21.5% vs. 9.5% of patients experienced a treatment delay longer than 1 month in 2020 compared with 2019 (p <0.001). In 2020, 7.1% (21/293) of patients had a diagnosis of an active COVID-19 infection: 11 (52.4%) patients were hospitalised and 4 (19.1%) patients died.

Conclusions

In a metropolitan area highly impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, we observed fewer patients with HCC, and similar rates of treatment modification, but with a significantly longer treatment delay in 2020 vs. 2019.

Lay summary

During the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic era, fewer patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) presented to the multidisciplinary tumour board, especially with a first diagnosis of HCC. Patients with HCC had a treatment delay that was longer in the COVID-19 period than in 2019.

Keywords: 2019-nCoV, COVID-19, Management, Hepatocellular carcinoma, Cirrhosis

Abbreviations: aOR, adjusted OR; BCLC, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer; EASL, European Association for the Study of Liver; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; ICU, intensive care unit; IQR, inter-quartile range; IR, interventional radiology; ITT, intention to treat; LR, liver resection; LT, liver transplantation; MELD, model for end-stage liver disease; MTB, multidisciplinary tumour board; NASH, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis; OR, odds ratio; SIRT, selective internal radiation therapy; TACE, transarterial chemoembolisation

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

During the COVID-19 period, fewer patients with HCC presented to the multidisciplinary tumour board.

-

•

Globally, modification in the treatment strategy was observed in 13.1% of patients.

-

•

More than 21% of patients experienced a treatment delay >1 month in the COVID-19 period compared with 9.5% in 2019.

-

•

COVID-19 infection was the main reason for treatment delays in 2020.

-

•

In 2020, 7.1% of patients had a diagnosis of an active COVID-19 infection and 4/21 (19.1%) died.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic, as declared by the World Health Organization,1 has no true precedent in modern times and is a rapidly evolving crisis worldwide. Cancer remains a heavy burden with more than 18 million cases diagnosed in 2018 according to the GLOBOCAN reports, with an estimated global prevalence beyond 43 million people.2

Cancer patients represent a vulnerable population because of their acquired immunodeficiency, and are at increased risk of COVID-19-related serious events (intensive care admission, requirement for mechanical ventilation, or death).3

In a report from China on 72,314 COVID-19-positive patients, the crude-fatality rate was 5.3% among cancer patients with higher mortality rates among those aged over 70 years.4,5 In an Italian cohort of 335 infected patients, 20.3% of patients with COVID-related disease who died had an active cancer.6

The context is complexified by the unusual altered allocation of healthcare resources to the pandemic, which might be responsible for collateral damage to the healthcare system on which patients depend: screening interruption, treatments cancelled or downgraded, follow up delay, and patient fear.7 According to the European Association for the Study of Liver (EASL) guidelines, management and care of patients affected by hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), the fourth cause of cancer-related death worldwide, should be maintained, even with minimal exposure to medical staff, including systemic treatments and liver transplantation (LT) work up.8 Similarly, the French Association for the Study of the Liver board suggests to maintain the curative treatments of HCC in dedicated hospital units, separate from COVID-19 patients.9 In France, the metropolitan area of Paris10 is heavily impacted by the outbreak and non-urgent procedures might be re-scheduled, with an approximate delay of 1–2 months.9

The aim of this study was to determine the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the management (compliance with multidisciplinary tumour board [MTB] decisions on the time and type of treatment) for patients affected by HCC within 6 French academic referral centres of the metropolitan area of Paris.

Methods and analysis

This study was designed as a multicentre, retrospective, cross-sectional study on the management of patients affected by HCC during the first 6 weeks of the COVID-19 pandemic (from 6 March 2020 to 17 April 2020), compared with the same period in 2019 (from 6 March 2019 to 17 April 2019), within the metropolitan area of Paris.

Six academic referral centres from the AP-HP network (Pitié Salpêtrière-Paris, Saint-Antoine-Paris, Cochin-Paris, Beaujon-Clichy, Jean-Verdier-Bondy), including the steering committee (Hôpital Henri Mondor, Créteil) were involved in the study, organised during the first week of the French national first wave of the pandemic (6–14 March 2020).

Informed consent was obtained from all the participants; the study was approved by the Henri-Mondor Institutional Review Board (Ethics number committee 00011558, Approval Number 2020-071), and led in compliance with Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines for cross-sectional studies.11

Inclusion criteria

-

-

Adult patients (>18 years old) affected by HCC (histological and/or radiological diagnosis according to the EASL criteria),12 who received during the inclusion period.

-

-

A proposal of treatment in MTB meetings.

OR

-

-

A programmed surgical or radiological procedure, such as liver resection (LR) or any interventional radiology (IR) procedure: percutaneous ablation (radiofrequency, microwaves, or irreversible electroporation), trans-arterial-chemo-embolisation (TACE), or selective internal radiation therapy (SIRT).

Study period

Patients fulfilling the inclusion criteria and exposed to the pandemic between 6 March 2020 and 17 April 2020 were considered as cases (Exposed_COVID), and those fulfilling the same inclusion criteria between 6 March 2019 and 17 April 2019 (Unexposed_COVID) were considered as controls.

Study endpoints

The impact of the pandemic on the management of the target population affected by HCC was measured as the number of patients with a change in the treatment strategy (treatment realised was different from what was proposed in the MTB), during the 2 periods. We aimed to assess the incidence of COVID-19 infection among the study cohort, MTB-to-treatment interval (days) between the MTB decision and treatment, the type of management (curative or palliative treatment) within the time periods for the exposed and control groups.

Variables

From the digital integrated care patient file (Orbis©, Agfa HealthCare, Mortsel, Belgium), we retrieved variables on general demographics, underlying liver disease, HCC characteristics (main tumour size, presence of tumour thrombosis, extrahepatic disease, and BCLC staging), serum alpha-fetoprotein level, and clinical management proposed within MTB meetings. The type of treatment proposed was detailed, as well as the treatment finally realised, and any potential delay between the date planned and the date treatment finally occurred. In cases where treatment did not occur, we estimated the decision-to-treatment delay from the MTB to the date of planned treatment. We also collected the reason for an alternative therapeutic decision and for a treatment delay. The reasons for outpatient cancellation were recorded, as well as the type of consultation (video/telemedicine or classical outpatient consultation).

Treatments proposals were classed as:

-

-

Curative intent: surgery (LR, liver transplantation [LT]) or percutaneous ablation by IR (radiofrequency, microwaves, or irreversible electroporation);

-

-

Palliative intent: systemic therapies including sorafenib, lenvantinib, immunotherapy, regorafenib, cabozantinib; external radiotherapy; TACE; SIRT;

-

-

Best supportive care.

The above treatments were classed as interventional (surgery, IR, external radiotherapy, TACE, SIRT) or non-interventional (systemic therapies including sorafenib, levantinib, immunotherapy, regorafenib, cabozantinib).

The treatment strategy was considered ‘downgraded’ in case of treatment switch from ‘curative intent’ to ‘palliative intent’ or ‘best supportive care’.

In the cohort of patients exposed to COVID-19 in 2020, were identified patients with a diagnosis of an active COVID-19 infection based on RT-PCR testing, suggestive chest CT, or typical COVID-19 symptoms (fever and upper respiratory tract symptoms – including anosmia, dysgeusia, fatigue, dry cough, and dyspnoea – with lymphopenia or leukopenia).

Data from each centre were entered in a single digital worksheet database, hosted on a secure computer. Dataset from each centre were harmonised and merged in a single dataset for analysis. Each patient was de-identified and assigned to an anonymised alpha-numeric code. The quality of data management was compliant to the reference methodology on personal data processing and protection (MR004), as stated by the French data protection authority (Commission Nationale de l'Informatique et des Libertés, CNIL n 2209983 v 0).

Sample size

No a priori sample size calculation was realised, and the whole cohort of patients according to the inclusion criteria was included.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive results were expressed as median with inter-quartile range (IQR) for continuous variables and as n (%) for categorical data. Baseline characteristics of patients and HCC were compared between the 2 period cohorts using the Mann-Whitney U test for continuous data, and χ2 test or Fisher exact test for qualitative variables. Variables significantly different between the 2 cohorts were used as variables for adjustment.

The main criteria and proportion of cases with modified treatment was compared between the 2 time period cohorts and expressed as crude odds ratio (OR) with 95% CIs. Baseline characteristics found different between the 2 period cohorts (with p <0.10) were tested in a logistic regression model giving adjusted OR (aOR) with 95% CI. The main criteria were analysed in the whole study population proposed for surgical, radiological, and medical treatment and separately in patients with a first diagnosis of HCC and patients in follow up for a known HCC. A logistic regression model was used to test variables independently associated with main criteria and aORs are presented with 95% CI. No multiple imputations were used. A value of p ≤0.05 was considered significant. All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS version 26 (IBM SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and Stata version 13.0 (Statacorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

General characteristics

We screened 1661 patients in 6 centres for eligibility: either presented in a MTB meeting (n = 543, Exposed_COVID; n = 804 Unexposed_COVID) or with a programmed surgical or radiological procedure with intention to treat between 6 March and 17 April in 2019 and 2020. A detailed flowchart is shown in Fig. 1. Of these patients, 723 were excluded because they were not affected by HCC, and a further 268 were excluded because of the absence of any treatment proposal (follow up or requiring further explorations). Six hundred and seventy patients were included, and represented the study population (n = 293 Exposed_COVID, n = 377 Unexposed_COVID). The percentage of males was 82.6%, and the median age was 67 (60–74) years; no differences were observed in terms of patient characteristics (Child-Pugh score, model for end-stage liver disease) or tumour patterns (maximum diameter, portal vein invasion, AFP) between the 2 periods (Table 1). Among the group of patients exposed to the pandemic, 7.1% (n = 21) had a diagnosis of COVID-19 infection.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of patients included in the study.

HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; IR, interventional radiology; LS, liver surgery; MTB, multidisciplinary tumour board.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of 670 patients discussed by the MTB.

| Unexposed COVID-19 2019 (n = 377) |

Exposed COVID-19 2020 (n = 293) |

p value∗∗ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex – male, n (%) | 309 (82.0) | 245 (83.6) | 0.608 |

| Age, years | 67 (60–74) | 67 (60–73) | 0.888 |

| Cirrhosis, n (%) | 317 (84.1) | 243 (82.9) | 0.753 |

| Liver disease aetiology, n (%) | |||

| HCV | 63 (16.7) | 51 (17.4) | |

| HBV | 59 (15.7) | 38 (12.9) | |

| HCV+HCV | 41 (10.9) | 44 (15.0) | 0.569 |

| Alcohol | 67 (17.8) | 53 (18.1) | |

| NASH | 65 (17.2) | 54 (18.4) | |

| Alcohol + NASH | 57 (15.1) | 38 (13.0) | |

| Other | 25 (6.6) | 15 (5.1) | |

| Tumour burden, mm (n = 638) | 30 (18–57) | 30 (18–56) | 0.582 |

| BCLC classification | |||

| BCLC 0 | 35 (9.3) | 28 (9.6) | |

| BCLC A | 133 (35.2) | 109 (37.2) | |

| BCLC B | 99 (26.3) | 81 (27.6) | 0.142 |

| BCLC C | 84 (22.3) | 51 (17.4) | |

| BCLC D | 26 (6.9) | 24 (8.2) | |

| Tumour thrombosis (n = 667) | 58 (15.5) | 43 (14.7) | 0.828 |

| Alpha-fetoprotein, ng/ml (n = 653) | |||

| <10 | 192 (52.3) | 139 (48.6) | 0.385 |

| >10 | 175 (47.7) | 147 (51.4) | |

| Inclusion criteria, n (%) | |||

| LS and IR performed | 145 (21.6) | 72 (24.6) | 0.109 |

| MTB discussion | 525 (78.4) | 221 (75.4) | |

| Type of management, n (%) | |||

| First diagnosis | 143(36.9) | 104 (35.5) | 0.520 |

| Follow up | 234 (62.1) | 189 (64.5) | |

| Diagnostic modality, n (%) | |||

| Imaging | 288 (76.4) | 229 (78.2) | 0.643 |

| Histology | 89 (23.6) | 64 (21.8) | |

| Imaging technique, n (%) (n = 613) | |||

| CT | 118 (35.0) | 90 (32.6) | |

| MRI | 118 (35.0) | 99 (35.9) | 0.813 |

| Both | 101 (30.0) | 87 (31.5) | |

| Proposed treatment | |||

| Curative | 148 (39.3) | 122 (41.6) | |

| Palliative | 185 (49.1) | 138 (47.1) | 0.830 |

| BSC | 44 (11.7) | 33 (11.3) | |

| Performed treatment | |||

| Curative | 137 (36.3) | 101 (34,5) | |

| Palliative | 172 (45.6) | 134 (45.7) | 0.357 |

| BSC | 65 (17.2) | 36 (12.3) | |

| Planned but not realised | 3 (0.8) | 21 (5.3) | <0.001 |

| Therapeutic protocol inclusion | 24 (6.4) | 12 (4.1) | 0.228 |

| Treatment change | 49 (13.0) | 39 (13.3) | 0.909 |

| Cause of treatment change | |||

| Disease progression | 32 (65.3) | 9 (23.1) | <0.001 |

| Failed or contra-indicated treatment | 13 (26.5) | 4 (10.2) | |

| Patient's choice | 4 (8.1) | 8 (20.5) | |

| Related COVID-19 | 0 | 18 (46.1) | |

| MTB-to-treatment interval, days | |||

| Curative∗ | 32 (23–55) | 31 (18–53) | 0.324 |

| Palliative | 25 (10–36) | 26 (13–38) | 0.786 |

| BSC | 1 (0–5) | 0 (0–7) | 0.558 |

| MTB-to-treatment interval >1 month | 36 (9.5) | 63 (21.5) | <0.001 |

| Treatment related | 16/33 (48.4) | 7/61 (11.4) | |

| Material related | 9 (27.2) | 3/61 (5) | <0.001 |

| COVID-19 related | 0 | 47 (77) | |

| Patient related | 8 (24.2) | 4/61 (6.5) | |

| Outpatient consultation | |||

| Cancelled | 5 (1.4) | 21 (7.8) | |

| Standard | 364 (97.3) | 165 (56.5) | <0.001 |

| Teleconsultation | 5 (1.3) | 105 (35.9) |

BSC, best supportive care; IR, interventional radiology; LS, liver surgery; LT, lung transplant; MTB, multidisciplinary tumour board, NASH, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis.

∗∗Categorical variables were compared using Fisher’s exact test and continuous variables using Mann Whitney non parametric test.

LT and the related work up were excluded.

Impact of the pandemic on MTB meetings, treatments, and patient follow up

The absolute number of patients affected by HCC – including those with a first diagnosis – presented to the MTB was lower in 2020 (n = 221) compared with 2019 (n = 304). This number significantly decreased over the weeks in 2020 but not in 2019 (p = 0.034), with a similar – but not significant – trend for those with a first diagnosis of HCC (p = 0.083) as detailed in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Distribution of patients discussed in the MTB.

Number of patients presented to the MTB over the same time periods during 2019 and 2020. Each period was split in half (first 3 weeks and second 3 weeks), and the distribution was compared. The numbers of patients with HCC presented to the MTB in 2020 decreased during the pandemic period: (for 2019: 6–26 March, n = 153; 27 March–7 April, n = 151; for 2020: 6–26 March, n = 132; 27 March–7 April, n = 89, Fisher’s exact test, p = 0.034). The number of patients presented to the MTB with a first diagnosis of HCC also decreased: (for 2019: 6–26 March, n = 52; 27 March–7 April, n = 61; for 2020: 6–26 March, n = 49, 27 March–7 April, n = 34, Fisher’s exact test, p = 0.083). MTB, multidisciplinary tumour board.

The rate of treatments (proposed or performed) in patients with active HCC during the inclusion period was 56.7% (n = 377) in 2019 vs. 43.7% (n = 293) in 2020, with a significant decrease during the second half of the time period in 2020 (p = 0.018).

We observed no significant differences in the decision-to-treatment interval between 2019 and 2020 (Table 1) for each treatment class. Nevertheless, a higher rate of patients experienced a treatment delay longer than 1 month in 2020 compared with 2019 (21.5%, n = 63 vs. 9.5%, n = 36, respectively; p <0.001). The reasons for this delay were different according to the study period (Table 1). When focusing on the COVID-19 period, a higher rate of patients requiring an interventional procedure experienced a delay longer than 1 month (interventional procedure: <1 month, n = 100 [54.3%] vs. >1 month, n = 75 [68.8%]), compared with those requiring medical treatment (medical treatment: <1 month, n = 77 [41.8%] vs. >1 month, n = 15 [13.8%], Table S1).

Overall, 36 patients (5.4%) accepted to be included within a study protocol, with no differences in the inclusion rates between the 2 periods (n = 12, 4.1% vs. n = 24, 6.4% in 2020 vs. 2019, respectively, p = 0.228).

Finally, apart from a higher rate of cancelled consultations, the outpatient models have changed with a significantly greater use of teleconsultation during the pandemic (7.8%, n = 21 vs. 1.4%, n = 5, respectively, p <0.001; Table 1).

Modifications of clinical care and treatment strategies

A modification in the treatment strategy (between the treatments proposed during MTB and those finally received) was reported in 13.1% (n = 88) of patients, with no differences between the 2 periods (13.3%, n = 39 in 2020 vs. 13%, n = 49 in 2019; p = 0.91; Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Modification of treatment strategy.

Difference between the treatment proposed to the MTB and the treatment actually received, during the study periods (13.3%, n = 39 in 2020 vs. 13%, n = 49 in 2019; Fisher’s exact test, p = 0.909). MTB, multidisciplinary tumour board.

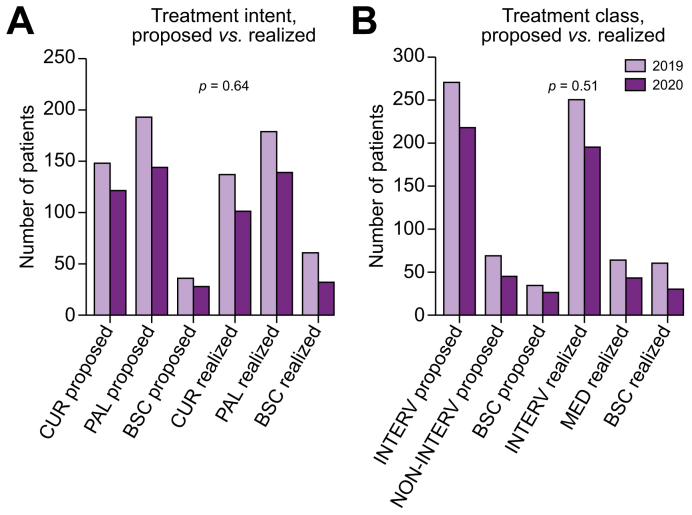

No differences were observed in the treatment distribution: neither for the treatment intent (curative, palliative, or BSC) nor class (interventional, non-interventional, or BSC), as shown in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Modification in treatment intent (A) or class (B), between the 2 time periods.

Comparison between years was performed using Fisher’s exact test. BSC, best supportive care; CUR, curative; INTERV, interventional treatment; NON-INTERV, non-interventional treatment; PAL, palliative.

The main reasons for the modification of treatment strategy were significantly different in 2020 compared with 2019: COVID-19 infection (46.1% in 2020 and 0% in 2019), and tumour progression (23.1% in 2020 and 65.3% in 2019; Table 1).

Subgroup analysis

Subgroup with active HCC, first diagnosis (Table 2)

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of 247 patients with first diagnosis of HCC.

| Unexposed COVID-19 2019 (n = 143) |

Exposed COVID-19 2020 (n = 104) |

p value∗∗ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex – male, n (%) | 124 (86.7) | 90 (86.5) | 1 |

| Age, years | 67 (60–74) | 69 (61–74) | 0.548 |

| Cirrhosis, n (%) | 116 (81.1) | 81 (77.9) | 0.631 |

| Liver disease aetiology, n (%) | |||

| HCV | 20 (14.0) | 17 (16.3) | |

| HBV | 28 (19.6) | 15 (14.5) | |

| HCV + HBV | 19 (13.3) | 13(12.5) | |

| Alcohol | 28 (19.6) | 21 (20.2) | 0.440 |

| NASH | 23 (16.1) | 25 (24.0) | |

| Alcohol + NASH | 17 (11.9) | 10 (9.6) | |

| Other | 8 (5.6) | 3 (2.9) | |

| Tumour burden, mm (n = 242) | 32 (22–60) | 49 (25–80) | 0.022 |

| BCLC classification | |||

| BCLC 0 | 11 (7.7) | 7 (6.7) | |

| BCLC A | 60 (42.0) | 46 (44.2) | |

| BCLC B | 27 (18.9) | 21 (20.2) | 0.780 |

| BCLC C | 27 (18.9) | 18 (17.3) | |

| BCLC D | 18 (12.6) | 12 (11.5) | |

| Tumour thrombosis | 26 (18.2) | 20 (19.2) | 0.869 |

| Alpha-fetoprotein, ng/ml (n = 241) | |||

| <10 | 66 (47.1) | 38 (37.6) | 0.149 |

| >10 | 74 (52.9) | 63 (62.4) | |

| Inclusion criteria, n (%) | |||

| LS and IR performed | 30 (21.0) | 21 (20.2) | 1 |

| MTB discussion | 113 (79.0) | 83 (79.8) | |

| Circumstance of diagnosis, n (%) | |||

| By chance | 25(17.4) | 17 (16.3) | |

| Screening | 72 (50.3) | 45 (43.6) | 0.401 |

| Symptomatic | 46 (32.2) | 42 (40.8) | |

| Diagnostic modality, n (%) | |||

| Imaging | 106 (74.1) | 72 (69.2) | 0.473 |

| Histology | 37 (25.9) | 32 (30.8) | |

| Imaging technique, n (%) (n = 220) | |||

| CT | 39 (31.7) | 30 (30.9) | |

| MRI | 44 (35.8) | 41 (42.3) | 0.551 |

| Both | 40 (32.5) | 26 (26.8) | |

| Proposed treatment | |||

| Curative | 68 (47.6) | 50 (48.1) | |

| Palliative | 43 (37.1) | 40 (38.5) | 0.576 |

| BSC | 22 (15.4) | 14 (13.5) | |

| Performed treatment | |||

| Curative | 63 (44.1) | 44 (42.3) | |

| Palliative | 48 (33.6) | 40 (38.5) | 0.530 |

| BSC | 31 (21.7) | 17 (16.3) | |

| None performed | 1 (0.7) | 3 (2.9) | |

| Therapeutic protocol inclusion | 10 (7.0) | 2 (1.9) | 0.078 |

| Treatment change | 22 (15.4) | 12 (11.5) | 0.456 |

| Cause of treatment change | |||

| Tumour progression | 12 (54.5) | 2 (16.7) | |

| Failed or contra-indicated treatment | 9 (40.9) | 2 (16.7) | <0.001 |

| Patient's choice | 1 (4.5) | 1 (8.3) | |

| Related to COVID-19 | 0 (0) | 7 (58.3) | |

| MTB-to-treatment interval, days | |||

| Curative∗ | 43 (24–61) | 31 (9–47) | 0.034 |

| Palliative | 30 (16–43) | 22 (13–31) | 0.109 |

| BSC | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–2) | 0.962 |

| MTB-to-treatment interval >1 month | 25 (17.5) | 19 (18.3) | 0.868 |

| Outpatient consultation | |||

| Cancelled | 5 (3.5) | 16 (15.4) | |

| Standard | 138 (96.5) | 68 (65.4) | <0.001 |

| Teleconsultation | 0 (0) | 20 (19.2) |

BSC, best supportive care; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; IR, interventional radiology; LS, liver surgery; MTB, multidisciplinary tumour board; NASH, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis.

∗∗Categorical variables were compared using Fisher’s exact test and continuous variables using Mann Whitney non parametric test.

LT and the related work up were excluded, only 4 cases of TH.

Among the 247 patients with a first diagnosis of HCC (n = 104 in 2020 vs. n = 143 in 2019), the tumour size was significantly larger in 2020 (49 [25–80] mm) compared with 2019 (32 [22–60] mm, p = 0.002) with no significant increase in AFP level in the 2 periods (Table 2).

Subgroup with active, recurrent HCC (Table 3)

Table 3.

Baseline characteristics of 423 patients with recurrent active HCC.

| Unexposed COVID-19 2019 (n = 234) |

Exposed COVID-19 2020 (n = 189) |

p value∗∗ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex – male, n (%) | 185 (79.1) | 155 (82.0) | 0.463 |

| Age, years | 67 (60–74) | 66 (60–73) | 0.549 |

| Cirrhosis, n (%) | 201 (85.9) | 162 (85.7) | 0.239 |

| Liver disease aetiology, n (%) | |||

| HCV | 43 (18.4) | 34 (18.0) | |

| HBV | 31 (13.2) | 23 (12.2) | |

| HCV + HBV | 22 (9.4) | 31 (16.4) | 0.542 |

| Alcohol | 39 (16.7) | 32 (16.9) | |

| NASH | 42 (17.9) | 29 (15.3) | |

| Alcohol + NASH | 40 (17.1) | 28 (14.8) | |

| Other | 17 (7.3) | 12 (6.3) | |

| Tumour burden, mm (n = 398) | 27 (16–50) | 25 (16–45) | 0.545 |

| BCLC classification (n = 404) | |||

| BCLC 0 | 24 (11.0) | 21 (11.4) | |

| BCLC A | 58 (26.5) | 59 (31.9) | |

| BCLC B | 72 (32.9) | 60 (32.4) | 0.224 |

| BCLC C | 57 (26.0) | 33 (17.8) | |

| BCLC D | 8 (3.7) | 12 (6.5) | |

| Tumour thrombosis (n = 421) | 32 (13.8) | 23 (12.2) | 0.665 |

| Alpha-fetoprotein, ng/ml (n = 412) | |||

| <10 | 126 (55.5) | 101 (54.6) | 0.921 |

| >10 | 101 (44.5) | 84 (45.4) | |

| Inclusion criteria, n (%) | |||

| LS and IR performed | 43 (18.4) | 51 (27.0) | 0.045 |

| MTB discussion | 191 (81.6) | 138 (73.0) | |

| Diagnostic modality, n (%) | |||

| Imaging | 182 (77.8) | 157 (83.1) | 0.643 |

| Histology | 52 (22.2) | 32 (16.9) | |

| Imaging technique, n (%) (n = 393) | |||

| CT | 79 (36.9) | 60 (33.5) | |

| MRI | 74 (34.6) | 58 (32.4) | 0.499 |

| Both | 61 (28.5) | 61 (34.1) | |

| Proposed treatment | |||

| Curative | 80 (34.2) | 72 (38.1) | |

| Palliative | 132 (56.4) | 98 (51.9) | 0.644 |

| BSC | 22 (9.4) | 19 (10.1) | |

| Performed treatment | |||

| Curative | 74 (31.6) | 57 (30.2) | |

| Palliative | 124 (53.0) | 94 (49.7) | 0.609 |

| BSC | 34 (14.5) | 19 (10.1) | |

| None performed | 2 (0.9) | 18 (9.5) | <0.001 |

| Therapeutic protocol inclusion | 14 (6.0) | 9 (4.8) | 0.669 |

| Treatment change | 27 (11.5) | 27 (14.3) | 0.464 |

| Cause of treatment change (n = 53) | |||

| Disease progression | 20 (74.1) | 6 (22.2) | |

| Failed or contra-indicated treatment | 5 (18.5) | 2 (7.4) | <0.001 |

| Patient's choice | 2 (7.4) | 6 (22.2) | |

| Related COVID-19 | 0 (0) | 13 (48.1) | |

| MTB-to-treatment interval, day | |||

| Curative∗ | 31 (22–40) | 31 (18–60) | 0.445 |

| Palliative | 22 (8–36) | 27 (11–43) | 0.116 |

| BSC | 1 (0–17) | 4 (0–23) | 0.871 |

| MTB-to-treatment interval >1 month | 11 (4.7) | 44 (23.3) | <0.001 |

| Outpatient consultation | |||

| Cancelled | 4 (1.7) | 6 (3.2) | |

| Standard | 226 (96.6) | 97 (51.3) | <0.001 |

| Teleconsultation | 4 (1.7) | 86 (45.5) |

BSC, best supportive care; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; IR, interventional radiology; LS, liver surgery; MTB, multidisciplinary tumour board; NASH, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis.

∗∗Categorical variables were compared using Fisher’s exact test and continuous variables using Mann Whitney non parametric test.

LT and the related work up were excluded.

This subgroup of 423 patients (n = 189 in 2020 vs. n = 234 in 2019) presented similar characteristics between the 2 periods. Nevertheless, the rate of patients with a delay of treatment longer than 1 month was significantly higher in 2020 vs. 2019 (n = 44, 23.3% vs. n=11, 4.7%, respectively; p <0.001; Table 3). When focusing only on the COVID-19 period, we observed differences between the classes of treatment with an MTB-to-treatment delay >1 month or <1 month (Table S2).

Subgroup of patients affected by COVID

Among patients exposed to the COVID-19 pandemic, 7.1% (21/293) had a diagnosis of an active COVID-19 infection. Patients were male in 62% of cases and 66.2 (43.5, 73.6) years old at diagnosis. This latter was based on PCR and CT scan or CT scan alone in more than two-thirds of patients (n = 8, 38.1% and n = 7, 33.3%, respectively), followed by PCR alone or typical symptoms of COVID-19 (both n = 3, 14.3%). Eleven patients (52.4%) were hospitalised with a median length of stay of 7.00 (2.00, 28.0) days, and 5 patients needed hospitalisation in an intensive care unit (ICU) but 3 were refused ICU admission. Two patients (9.5%) developed acute respiratory distress syndrome in our group, the rate of complications was similar to patients with other cancer.13 Their medical treatment was highly heterogeneous, including antibiotic regimen, hydrochloroquine, and antivirals. Overall, 4 patients died (19.1%), including the 2 hospitalised in ICU (Table S3), with a median OS of 26.0 (3.00, 65.0) days.

Multivariate logistic regression for predictors of intention to treat strategy change (Table 4)

Table 4.

Uni- and multivariate logistic regression analysis for changed/delayed treatment and for delay of treatment ≥1 month.

| Univariate analysis |

Multivariate analysis∗ |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p value | aOR | 95% CI | p value | |

| Changed/delayed treatment | ||||||

| Diagnosis status | ||||||

| First diagnosis | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Follow up | 3.022 | 1.02–8.95 | 0.046 | 2.968 | 0.99-8.90 | 0.052 |

| Proposed treatment | ||||||

| Systemic | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Interventional | 4.160 | 0.97–17.88 | 0.055 | 3.982 | 0.92–17.32 | 0.065 |

| Period | ||||||

| 2019 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 2020 | 9.661 | 2.85–32.72 | <0.001 | 9.323 | 2.74–31.69 | <0.001 |

| Delay of treatment ≥1 month | ||||||

| Proposed treatment | ||||||

| Systemic | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Interventional | 9.518 | 3.44–26.36 | <0.001 | 9.585 | 4–26.69 | 0.065 |

| Period | ||||||

| 2019 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 2020 | 3.267 | 2.03–5.25 | <0.001 | 3.288 | 2.03–5.33 | <0.001 |

Hosmer Lemeshow test: changed/delayed treatment = 0.967; aOR adjusted for type of management and type of treatment; delay of treatment ≥1 month = 0.956. aOR, adjusted odds ratio.

In univariate analysis, the diagnosis status (first diagnosis or follow up), the type of treatment proposed and the period (2019 vs. 2020) were associated with a significant delay or change in strategy of treatment. On multivariate analysis, only the period in 2020 was independently associated with delay or change in strategy (aOR = 9.661 [95% CI: 2.85–32.72], p <0.001; Table 4).

When focusing on variables associated with a treatment delay longer than 1 month, the period and the type of treatment proposed were found to be significant using univariate analysis. After adjusting, only the period in 2020 was independently associated (aOR = 9.323, 95% CI: 2.74–31.69, p <0.001; Table 4).

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic has suddenly shattered the processes of healthcare in general, and for patients affected by cancer in particular. In France, similarly to other Western countries, planned clinical activities were reduced and postponed to minimise the risk of viral transmission but also to allow the re-assignment of health professionals to support COVID-19 units. Recommendations14 by scientific societies try to deal with the current situation, but the real impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in HCC management is still unknown. A recent multicentre Italian study reported the outcomes of COVID-19 infection in patients with cirrhosis.15 In contrast, our study focused on HCC and the treatment received in this period.

In this study, involving 6 referral academic centres within the metropolitan area of Paris, highly affected by the pandemic, we observed a significant decrease over the weeks in the rate of patients with HCC referred for first diagnosis or treatment (proposed or performed). The interpretation of these findings may rely on a complex set of correlated reasons, including an increased delay of consultation of patients for symptoms to their general practitioner, a decreased referral by other professionals because of fear of COVID-19 infection, and reduced access to diagnostic tools, operating theatres, and ICU. The lower number of new patients with HCC diagnosed during the COVID-19 period could be also explained by the travel limitation which prevented patients from other areas reaching medical centres in Paris.

Hence, the modification in the treatment strategy (curative vs. palliative, and interventional vs. non-interventional) were not different in 2020 from 2019. A panel of experts published recommendations about treatment modification and downgrading16 for patients with HCC in the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the period of the current study was at the beginning of the lockdown, before these recommendations were published.

The rate of patients with a treatment delay longer than 1 month was significantly higher in 2020 compared with 2019, and this observation is supported by multivariate analysis, in which the period 2020 was found to be a strong independent predictor of treatment delay or cancellation. This finding could be explained by a decreased access to operating theatres, interventional radiology facilities, post-operative ICUs, and ventilators, forcing physicians to delay patient treatment. However, we found a shorter interval between presentation to the multidisciplinary tumour board and treatment in 2020 compared with 2019. This difference could be explained by the high numbers of treatments delayed in 2020 after the period considered. Consequently, the few patients treated during the COVID-19 period in 2020 has a shorter delay to treatment compared with 2019. Most of the patients with a treatment delayed for more than 1 month have a recurrent HCC. These data suggested that physicians tended to treat patients with a new HCC more quickly during the COVID-19 period. We could hypothesise that patients with new HCC tend to be treated quickly because of the lack of knowledge of tumour biology and the pressure of patients who received a recent diagnosis of cancer. In patients with HCC recurrence, the physician tends to be familiar with the tumour biology and could adapt the delaying of treatment accordingly.

Not surprisingly, the significant shift towards the rates of teleconsultation in 2020 vs. 2019 is related to social distancing measures as well as patient fear, as a result of the pandemic. The impact of teleconsultation on the patient–physician relationship, as well as on the patient's understanding of HCC diagnosis and treatment should be further explored.

Finally, 7.1% of patients exposed to the pandemic were affected by COVID-19, and almost half of them required hospitalisation. With 4 deaths (19%) the crude fatality rate in this study population is significantly higher than that reported in China,4,5 Italy,6 or the UK,17 but is consistent with reported French government data.10 The reduced number of infected patients and the competitive risk of death of cancer and comorbidities prevent any reliable conclusion. The mortality rate (19.2%) was lower than that observed at 30 days (34%) in patients with cirrhosis (mostly without HCC) in an Italian multicentre study.15 Of note, fewer patients required hospitalisation in our series (52.4%) compared with the Italian cohort (96%) suggesting a different severity profile at baseline.

We have to emphasise that the COVID-19 diagnosis was performed by clinicians and was not a systematic prospective assessment of patient symptoms with a pre-defined PCR or CT scan-based diagnostic algorithm.

The main limit of this study is represented by the uncertain delay of treatment reported in 2020 (at the time of the study, some 7% of patients had not received the treatment planned) preventing calculation of a reliable delay that could be compared with 2019. In this study, we could not assess the impact on patient survival of treatment delay and of the reduced rates of MTB presentations. Moreover, the observations reported in this study could not be generalised to areas with a low incidence of COVID-19 infection.

To better understand the impact of COVID-19 on HCC management, we will need to gather the reasons for the reduction in MTB presentations and the delay in treatments. These data would be helpful to improve access to clinical care for patients affected by cancer, and could be generalised to other types of cancers, in case of future pandemics.

This study is a very early snapshot (6 weeks) of the French lockdown (10 weeks); it offers the first report of a homogeneous population affected by HCC within a network of high-volume academic French centres in a COVID-19 pandemic area.

Based on the available data, the pandemic seems to impact the management of patients affected by HCC in one-quarter of the population, owing to a delay in treatment realisation but not with a modification in treatment strategy.

The mid-term follow up of this cohort will inform about the impact of the pandemic on the long-term HCC management, waitlist dropout, and mortality.

Authors' contributions

Conceived and organised the study, planned the data management, organised data collection for the steering centre and contributed to the statistical analyses, wrote the manuscript and figures, obtained the IRB approval, gave their final approval of the manuscript: GA, RB.

Organised data collection for each participating centre, significantly contributed to the manuscript and gave the final approval before submission: JCN, MA, ML, CH, HR, MB.

Planned and realised the statistical analyses, significantly contributed to the manuscript and gave her final approval before submission: FRT.

Revised the manuscript and gave their final approval before submission: all remaining authors.

Data availability

Research data are not available for sharing given their confidential nature.

Conflict of interest

JCN received a research grant from Bayer for INSERM UMR1138. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest that pertain to this study.

Please refer to the accompanying ICMJE disclosure forms for further details.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhepr.2020.100199.

Contributor Information

Giuliana Amaddeo, Email: giuliana.amaddeo@aphp.fr.

Jean-Charles Nault, Email: naultjc@gmail.com.

Supplementary data

References

- 1.Coronavirus disease 2019. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019?gclid=Cj0KCQjwzZj2BRDVARIsABs3l9KnvaU-065-0zz6tR7Qr-ZRzsyzY5TEU3mO-mdhSLe9j9Kx72bTgcUaAg4FEALw_wcB Available at.

- 2.Bray F., Ferlay J., Soerjomataram I., Siegel R.L., Torre L.A., Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gosain R., Abdou Y., Singh A., Rana N., Puzanov I., Ernstoff M.S. COVID-19 and cancer: a comprehensive review. Curr Oncol Rep. 2020;22:53. doi: 10.1007/s11912-020-00934-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu Z., McGoogan J.M. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020;323:1239–1242. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liang W., Guan W., Chen R., Wang W., Li J., Xu K. Cancer patients in SARS-CoV-2 infection: a nationwide analysis in China. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:335–337. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30096-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Onder G., Rezza G., Brusaferro S. Case-fatality rate and characteristics of patients dying in relation to COVID-19 in Italy. JAMA. 2020;323:1775–1776. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.You B., Ravaud A., Canivet A., Ganem G., Giraud P., Guimbaud R. The official French guidelines to protect patients with cancer against SARS-CoV-2 infection. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:619–621. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30204-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boettler T., Newsome P.N., Mondelli M.U., Maticic M., Cordero E., Cornberg M. Care of patients with liver disease during the COVID-19 pandemic: EASL-ESCMID position paper. JHEP Rep. 2020;2:100113. doi: 10.1016/j.jhepr.2020.100113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ganne-Carrié N., Fontaine H., Dumortier J., Boursier J., Bureau C., Leroy V. Suggestions for the care of patients with liver disease during the Coronavirus 2019 pandemic. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2020;44:275–281. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2020.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Info coronavirus covid 19 – carte et donnees covid 19 en france, Gouvernement.fr. https://www.gouvernement.fr/info-coronavirus/carte-et-donnees Available at.

- 11.von Elm E., Altman D.G., Egger M., Pocock S.J., Gøtzsche P.C., Vandenbroucke J.P. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61:344–349. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Galle P.R., Forner A., Llovet J.M., Mazzaferro V., Piscaglia F., Raoul J.L. EASL clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2018;69:182–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuderer N.M., Choueiri T.K., Shah D.P., Shyr Y., Rubinstein S.M., Rivera D.R. Clinical impact of COVID-19 on patients with cancer (CCC19): a cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10241):1907–1918. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31187-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Di Fiore F., Bouché O., Lepage C., Sefrioui D., Gangloff A., Schwarz L. COVID-19 epidemic: proposed alternatives in the management of digestive cancers: a French intergroup clinical point of view (SNFGE, FFCD, GERCOR, UNICANCER, SFCD, SFED, SFRO, SFR) Dig Liver Dis. 2020;52:597–603. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2020.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iavarone M., D'Ambrosio R., Soria A., Triolo M., Pugliese N., Del Poggio P. High rates of 30-day mortality in patients with cirrhosis and COVID-19. J Hepatol. 2020;73:1063–1071. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barry A., Apisarnthanarax S., O'Kane G.M., Sapisochin G., Beecroft R., Salem R. Management of primary hepatic malignancies during the COVID-19 pandemic: recommendations for risk mitigation from a multidisciplinary perspective. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5:765–775. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30182-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Undela K., Gudi S.K. Assumptions for disparities in case-fatality rates of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) across the globe. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2020;24:5180–5182. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202005_21215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Research data are not available for sharing given their confidential nature.