Abstract

Prior to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, telehealth was rarely utilized for oncologic care in metropolitan areas. Our large New York City based outpatient breast/gynecologic cancer clinic administered an 18-question survey to patients from March to June 2020, to assess the perceptions of the utility of telehealth medicine. Of the 622 patients, 215 (35%) completed the survey, and of the 215 respondents, 74 (35%) had participated in a telehealth visit. We evaluated the use of telehealth services using the validated Service User Technology Acceptability Questionnaire. Sixty-eight patients (92%) reported that telehealth services saved them time, 54 (73%) reported telehealth increased access to care, and 58 (82%) reported telehealth improved their health. Overall, 67 (92%) of patients expressed satisfaction with the use of telehealth services for oncologic care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Telehealth services should be carefully adopted as an addition to in-person clinical care of patients with cancer.

Keywords: Breast neoplasms, Coronavirus, Quality of life, Telemedicine

The first case of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) in New York State was detected in New York City (NYC) on March 1, 2020; COVID-19 was announced as a global pandemic by the World Health Organization shortly thereafter. The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic presents unique obstacles to the care of chronically ill and immunocompromised patients, including those with cancer—specifically, breast and gynecological malignancies. SARS-CoV-2 is rapidly spread from person-to-person via respiratory droplet transmission between individuals in close contact with one another [1,2,3]. Growing evidence suggests that patients with cancer have a greater risk of contracting COVID-19 and experiencing severe events such as admission to an intensive care unit, invasive ventilation, or death when infected [4,5,6,7].

Recommendations for breast cancer management during the COVID-19 pandemic published by established medical associations from the United States, United Kingdom and Europe included minimizing in-person appointments to prevent the spread of COVID-19 [8]. Although the current guidelines from the American Society of Clinical Oncology provide that telemedicine should be utilized to expand service capabilities, telemedicine has, historically, rarely been utilized in providing oncologic care [9]. A meta-analysis by Chen et al. [10], studied the psychosocial outcomes of telehealth interventions on breast cancer patients; however, it did not evaluate patients' perceptions of the care they were receiving. A systematic review by Cox et al. [11] studied cancer survivors' experience with telehealth. However, none of the participants included in their review were actively receiving treatment. Despite these shortcomings, both Chen et al. and Cox et al.'s findings [10,11] support the positive impact of telemedicine on patients. Chen et al. [10] found that telehealth interventions resulted in greater alleviation of stress and had a positive effect on patients' quality of life, perceived distress, and self-efficacy. Cox et al. [11] concluded that telemedicine had the potential to provide cancer survivors with a greater sense of independence.

Although the only studies that assess cancer patients' experiences with telemedicine are from programs that serve rural populations, these studies also paint an overwhelmingly positive reception of telemedicine. Several studies from programs in rural areas including Texas, Tennessee, Mississippi, Arkansas, and Newfoundland and Labrador all reported high patient satisfaction from the majority of patients, as well as other benefits such as convenience and cost effectiveness [12,13]. It is likely that these individuals would have different experiences from those living in a metropolitan area during a global pandemic. Cancer patients living through COVID-19 may feel an increased sense of isolation and fear, and have less access to social support due to social distancing and quarantine [4]. At our large NYC-based outpatient breast and gynecologic cancer clinic, telehealth services were quickly adopted for visits that could be completed outside of the clinic, in order to limit patient exposure to SARS-CoV-2. These services consisted of video-based telehealth visits through the electronic medical system. These visits were typically 15 to 30 minutes in duration, with patient assessed vital signs (when indicated), limited physical exam based on visual inspection, and patient and provider-based discussion of the patient's oncologic care. These services replaced non-essential in-person visits but did not replace essential visits required for physical exams, laboratory checks, chemotherapy, or other treatment administration. Any concerns that could not be addressed via telehealth required the scheduling of an in-person visit.

This survey-based study aimed to assess patients' perceptions of the utility of telehealth in their oncologic care during a time of national crisis and its impact on various quality of life measures. An 18-question survey was administered to all patients receiving care at our outpatient breast and gynecologic cancer treatment center from March 1, 2020 to June 30, 2020 (Appendix 1). Patients were included if they were seen in the clinic during that time, as well as if they had visits delayed or cancelled during this period. The survey was administered both by email through REDCap and physical copies given at the clinic, wherein the survey was returned anonymously through a drop-box. All responses were de-identified and personal data was not available to the researchers. This study received approval from the Mount Sinai Hospital institutional review board [IRB] (IRB-20-03619). The study was exempt from requiring the patient's completion of a consent form. Consent was obtained by completion of the survey itself and the patient's review of the exemption form which was attached to the survey. Survey responses were summarized by number (%) using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, USA). No hypothesis testing was performed.

For telehealth-specific questions, we adopted the validated Service User Technology Acceptability Questionnaire (SUTAQ) because the population it has been reliability tested for most closely fits the breast and gynecologic cancer patient population we serve—those with long-term health conditions or with social care needs [14,15]. The SUTAQ assesses patient acceptability of telehealth services via measures of accessibility, comfort, usability, privacy and security, confidentiality, satisfaction, convenience, and health benefits with in-home telemonitoring. For all survey questions using the SUTAQ scale, “agreement” was considered if the patient selected mildly, moderately, or strongly agreed on the 6-point scale (Appendix 2).

Of the 622 patients who received the survey via REDCap online or through a physical copy given at the clinic, 215 (35%) completed the survey. Of the 188 patients who responded to the question about their diagnostic history, 55 (29%) had a history of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS)/atypical ductal hyperplasia (ADH)/lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS), 96 (51%) had a history of invasive breast cancer, 7 (4%) had a gynecologic malignancy, and 30 (16%) responded “other.”

Of the 212 patients who responded to the question on whether they had participated in a telehealth visit during the COVID-19 pandemic, 74 (35%) responded that they participated in a telehealth visit during the 4-month evaluation period. Of the patients who participated in telehealth visits, 68 (92%) felt that the telehealth services saved them time as they did not have to visit their oncology clinic as often. Fifty-four (73%) felt that the telehealth services increased their access to care (health or social care professionals) and 58 (82%) reported that the telehealth services helped improve their health. Forty-five patients (63%) reported that telehealth services made them more actively involved in their own health, and 50 (68%) felt that these services allowed the people looking after them to better monitor them and their condition.

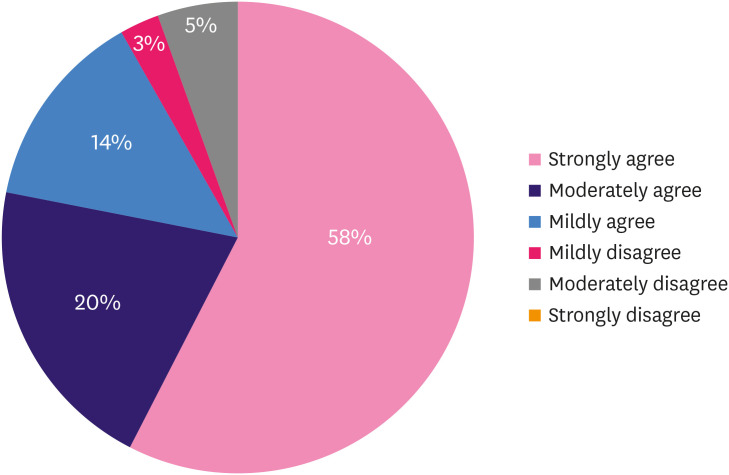

Overall, 67 (92%) patients were satisfied with the telehealth services they received, with 42 (57.5%) reporting that they “strongly agreed” that they were satisfied with the telehealth services (Figure 1). Of the respondents, 66 (89%) would recommend these services to people with similar health conditions. Twenty-seven (37%) felt that telehealth can be a replacement for their normal health care and 69 (93%) reported it could be a good addition to their care. Fifty-six (76%) would be interested in participating in telehealth visits in the future.

Figure 1. Patient satisfaction with telehealth services. Answer to the statement “I am satisfied with the telehealth services I received.” Overall, 58% of patients “strongly agreed” that they were satisfied with the telehealth services, 20% moderately agreed, 14% mildly agreed, 3% mildly disagreed, 5% moderately disagreed, and 0% strongly disagreed.

Very few patients reported concerns regarding the safety or confidentiality of the telehealth services. Only 8 (11%) patients felt that the telehealth services made them feel uncomfortable (physically or emotionally) and 5 (7%) worried about confidentiality related to telehealth usage. However, 48 (65%) patients felt that telehealth services were not as suitable as regular face-to-face consultations. Additional responses to all telehealth survey questions can be found in Table 1.

Table 1. Adapted SUTAQ and patient responses.

| Adapted SUTAQ for COVID-19 pandemic | Percentage of patients | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strongly disagree | Moderately disagree | Mildly disagree | Mildly agree | Moderately agree | Strongly agree | ||

| The telehealth services I received have saved me time in that I did not have to visit my oncology clinic as often. | 3 (4.1) | 1 (1.4) | 2 (2.7) | 12 (16.2) | 11 (14.9) | 45 (60.8) | 74 |

| The telehealth services I received have increased my access to care (health and/or social care professionals). | 6 (8.1) | 7 (9.5) | 7 (9.5) | 15 (20.3) | 17 (23.0) | 22 (29.7) | 74 |

| The telehealth services I received has helped me to improve my health. | 4 (5.6) | 4 (5.6) | 5 (7.0) | 20 (28.2) | 23 (32.4) | 15 (21.1) | 71 |

| The telehealth services have made me feel uncomfortable, e.g., physically or emotionally. | 47 (66.2) | 8 (11.3) | 8 (11.3) | 3 (4.2) | 3 (4.2) | 2 (2.8) | 71 |

| The telehealth services have allowed me to be less concerned about my health and/or social care. | 16 (21.6) | 6 (8.1) | 12 (16.2) | 14 (18.9) | 12 (16.2) | 14 (18.9) | 74 |

| The telehealth services have made me more actively involved in my health. | 10 (13.9) | 6 (8.3) | 11 (15.3) | 19 (26.4) | 19 (26.4) | 7 (9.7) | 72 |

| The telehealth services make me worried about the confidentiality of the private information being exchanged through it. | 48 (65.8) | 12 (16.4) | 8 (11.0) | 5 (6.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 73 |

| The telehealth services allow the people looking after me to better monitor me and my condition. | 6 (8.2) | 8 (11.0) | 9 (12.3) | 18 (24.7) | 18 (24.7) | 14 (19.2) | 73 |

| I am satisfied with the telehealth services I received. | 0 (0.0) | 4 (5.5) | 2 (2.7) | 10 (13.7) | 15 (20.5) | 42 (57.5) | 73 |

| The telehealth services should be recommended to people in a similar condition to mine. | 1 (1.4) | 2 (2.7) | 5 (6.8) | 15 (20.3) | 20 (27.0) | 31 (41.9) | 74 |

| The telehealth services can be a replacement for my regular health or social care. | 22 (30.1) | 11 (15.1) | 13 (17.8) | 10 (13.7) | 11 (15.1) | 6 (8.2) | 73 |

| The telehealth services can certainly be a good addition to my regular health or social care. | 2 (2.7) | 2 (2.7) | 1 (1.4) | 12 (16.2) | 19 (25.7) | 38 (51.4) | 74 |

| The telehealth services are notas suitable as regular face to face consultations with the people looking after me. | 6 (8.1) | 8 (10.8) | 12 (16.2) | 13 (17.6) | 21 (28.4) | 14 (18.9) | 74 |

| The telehealth services have made it easier to get in touch with health and social care professionals. | 2 (2.8) | 8 (11.1) | 9 (12.5) | 19 (26.4) | 19 (26.4) | 15 (20.8) | 72 |

| The telehealth services have allowed me to be less concerned about my health status. | 17 (23.6) | 7 (9.7) | 14 (19.4) | 13 (18.1) | 12 (16.7) | 9 (12.5) | 72 |

| I would be interested in continuing to participate in telehealth visits in the future. | 4 (5.5) | 5 (6.8) | 8 (11.0) | 13 (17.8) | 23 (31.5) | 20 (27.4) | 73 |

Values are presented as number (%).

SUTAQ = Service User Technology Acceptability Questionnaire; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019.

The COVID-19 pandemic led to major changes in the structure of oncologic care for the patients in our NYC center as we experienced the first peak of the pandemic from March through June 2020. The adaptation of telehealth services was one of the greatest changes to our practice, with telehealth visits increasing from rare usage to accounting for about 30% of all visits. Overall, patients with breast and gynecologic malignancies expressed satisfaction with the use of telehealth services for oncologic care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Although most patients do not feel that this is a suitable replacement for their in-person care, they expressed that it was certainly a good addition to their care. A large majority of patients expressed interest in continuing to participate in telehealth visits in the future. Based on this data and prior studies, telehealth services should be carefully adopted as a long-term addition to the in-person clinical care of patients with cancer, including those being treated in metropolitan areas.

There were several strengths to this study. First, the COVID-19 pandemic provided a rare opportunity to assess the rapid implementation of telehealth on a large scale, which otherwise likely would not have occurred. Secondly, it allowed us to receive rapid feedback regarding use of these services during an emergency public health situation. Based on the results of our study, telehealth is an excellent option for care of breast and gynecologic patients during times when in-person visits may need to be limited. These results also support the use of telehealth services in metropolitan areas and in high-risk oncology patients—patient groups in which the perception of telehealth has rarely been explored. Limitations of this study include that a large percentage of patients were undergoing routine follow-up for less active oncologic disorders such as DCIS/ADH/LCIS. From this study, we cannot identify the percentage of patients who were receiving active chemotherapy or systemic therapy for metastatic disease. We also were not able to stratify patient perception of telehealth by disease type, as the survey was anonymous. We are unable to assess long-term outcomes in this study population as that would take many years of follow up.

We acknowledge that there are inherent challenges in the incorporation of telehealth for care of cancer patients. These visits cannot replace in-person care, full assessment of vital signs, certain aspects of the physical exam (including breast exam) and chemotherapy, and other treatment administration which are specific to this population. The safety of telehealth services for breast and gynecologic cancer patients has not been specifically established, although major safety issues have not been reported in prior studies [10,11]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, benefits of telehealth outweighed the risks, and it was widely adapted. This study reported subjective measures of patient satisfaction but did not evaluate objective measures of patient safety and cancer-related outcomes which will need to be established in future large-scale studies with prolonged follow-up. However, in this study reported here, patients did not report any specific safety-related concerns in the comments section of the survey.

In conclusion, telehealth services can be utilized in addition to in-person care of patients with breast and gynecologic cancer in order to optimize patient satisfaction, save time and increase access to care, especially in times of public health crises. The findings of this study can likely be extrapolated to patients with other types of cancer in order to provide increased access to care for patients in metropolitan areas.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to acknowledge the support of the Biostatistics Shared Resource Facility funded by the National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support Grant P30CA196521-01 for analysis and interpretation of data and preparation of the manuscript.

Appendix 1. Survey questions (adapted Service User Technology Acceptability Questionnaire [SUTAQ])

Dubin Breast Center COVID-19 Care Questionnaire

Please complete the following survey in order to help your doctors understand the impact of COVID-19 on the perception of your oncology care.

By completing the survey, you will be providing consent for your data to be published. These survey results will in no way affect your future oncologic care.

This survey is anonymous.

-

1. What are you currently or previously receiving care for at Dubin Breast Center?

- a. DCIS (ductal carcinoma in situ), ADH (atypical ductal hyperplasia), ALH (atypical lobular hyperplasia) or LCIS (lobular carcinoma in situ)

- b. Invasive breast cancer

- c. Gynecological malignancy (ovarian, cervical, endometrial)

- d. Other: _________________________________________________

-

2. Have you participated in a telehealth (video) visit with your oncologist between March 1, 2020 through June 30, 2020?

- a. Yes

- b. No

Below is a list of statements referring to the telehealth you may have received to support your care during the COVID pandemic. Please indicate the degree to which you agree with each statement by TICKING the corresponding box.

3. The telehealth services I received have saved me time in that I did not have to visit my oncology clinic as often.

4. The telehealth services I received have increased my access to case (health and/or social care professionals).

5. The telehealth services I received has helped me to improve my health.

6. The telehealth services have made me feel uncomfortable, e.g., physically or emotionally.

7. The telehealth services have allowed me to be less concerned about my health and/or social care.

8. The telehealth services have made me more actively involved in my health.

9. The telehealth services make me worried about the confidentiality of the private information being exchanged through it.

10. The telehealth services allows the people looking after me to better monitor me and my condition.

11. I am satisfied with the telehealth services I received.

12. The telehealth services should be recommended to people in a similar condition to mine.

13. The telehealth services can be a replacement for my regular health or social care.

14. The telehealth services can certainly be a good addition to my regular health or social care.

15. The telehealth services are not as suitable as regular face to face consultations with the people looking after me.

16. The telehealth services have made it easier to get in touch with health and social care professionals.

17. The telehealth services have allowed me to be less concerned about my health status.

18. I would be interested in continuing to participate in telehealth visits in the future.

Appendix 2. Original Service User Technology Acceptability Questionnaire (SUTAQ)

Instructions: Below is a list of statements referring to the kit (TeleHealth and/or TeleCare equipment) you have received to support your care. Please indicate the degree to which you agree with each statement by TICKING the corresponding box.

1. The kit I received has saved me time in that I did not have to visit my GP clinic or other health/social care professional as often.

2. The kit I received has interfered with my everyday routine.

3. The kit I received has increased my access to care (health and/or social care professionals).

4. The kit I received has helped me to improve my health.

5. The kit I received has invaded my privacy.

6. The kit has been explained to me sufficiently.

7. The kit can be trusted to work appropriately.

8. The kit has made me feel uncomfortable, e.g., physically or emotionally.

9. I am concerned about the level of expertise of the individuals who monitor my status via the kit.

10. The kit has allowed me to be less concerned about my health and/or social care.

11. The kit has made me more actively involved in my health.

12. The kit makes me worried about the confidentiality of the private information being exchanged through it.

13. The kit allows the people looking after me, to better monitor me and my condition.

14. I am satisfied with the kit I received.

15. The kit can be/should be recommended to people in a similar condition to mine.

16. The kit can be a replacement for my regular health or social care.

17. The kit can certainly be a good addition to my regular health or social care.

18. The kit is not as suitable as regular face to face consultations with the people looking after me.

19. The kit has made it easier to get in touch with health and social care professionals.

20. The kit interferes with the continuity of the care I receive (i.e. I do not see the same care professional each time).

21. I am concerned that the person who monitors my status, through the kit, does not know my personal health/social care history.

22. The kit has allowed me to be less concerned about my health status.

Thank you for your responses to this questionnaire, please check that you have answered all items. Your responses will be kept confidential

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Below are the financial relationships with industry reported by Dr. Amy Tiersten during 2019-2020. Consulting: Immunomedics, AstraZeneca, Novartis, Elsai Inc, Cowen, Athenex. Research funding: Pfizer. The other authors (Brittney S. Zimmerman, Danielle Seidman, Natalie Berger, Krystal P. Cascetta, Michelle Nezolosky, Kara Trlica, Alisa Ryncarz, Caitlin Keeton and Erin Moshier) have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

- Conceptualization: Zimmerman BS, Seidman D, Berger N, Nezolosky M, Trlica K, Keeton C, Moshier E, Tiersten A.

- Data curation: Zimmerman BS, Seidman D, Berger N, Cascetta KP, Nezolosky M, Trlica K, Ryncarz A, Keeton C, Moshier E, Tiersten A.

- Formal analysis: Moshier E.

- Investigation: Zimmerman BS, Seidman D.

- Methodology: Zimmerman BS, Seidman D, Moshier E.

- Supervision: Tiersten A.

- Writing - original draft: Zimmerman BS, Seidman D, Berger N, Cascetta KP, Trlica K, Ryncarz A, Moshier E, Tiersten A.

- Writing - review & editing: Zimmerman BS, Seidman D, Berger N, Cascetta KP, Nezolosky M, Trlica K, Ryncarz A, Keeton C, Moshier E, Tiersten A.

References

- 1.Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, Qu J, Gong F, Han Y, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395:507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu YC, Chen CS, Chan YJ. The outbreak of COVID-19: an overview. J Chin Med Assoc. 2020;83:217–220. doi: 10.1097/JCMA.0000000000000270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, Li X, Yang B, Song J, et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Al-Shamsi HO, Alhazzani W, Alhuraiji A, Coomes EA, Chemaly RF, Almuhanna M, et al. A practical approach to the management of cancer patients during the novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: an international collaborative group. Oncologist. 2020;25:e936–45. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2020-0213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liang W, Guan W, Chen R, Wang W, Li J, Xu K, et al. Cancer patients in SARS-CoV-2 infection: a nationwide analysis in China. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:335–337. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30096-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liang X, Yang C. Full spectrum of cancer patients in SARS-CoV-2 infection still being described. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2020;32:407. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2020.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yu J, Ouyang W, Chua ML, Xie C. SARS-CoV-2 transmission in patients with cancer at a tertiary care hospital in Wuhan, China. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6:1108–1110. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.0980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Luther A, Agrawal A. A practical approach to the management of breast cancer in the COVID-19 era and beyond. Ecancermedicalscience. 2020;14:1059. doi: 10.3332/ecancer.2020.1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Society of Surgical Oncology. Resource for Management Options of Breast Cancer during COVID-19. Rosemont: Society of Surgical Oncology; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen YY, Guan BS, Li ZK, Li XY. Effect of telehealth intervention on breast cancer patients' quality of life and psychological outcomes: a meta-analysis. J Telemed Telecare. 2018;24:157–167. doi: 10.1177/1357633X16686777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cox A, Lucas G, Marcu A, Piano M, Grosvenor W, Mold F, et al. Cancer survivors' experience with telehealth: a systematic review and thematic synthesis. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19:e11. doi: 10.2196/jmir.6575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scurrey S, Garland SN, Thoms J, Laing K. Evaluating the experience of rural individuals with prostate and breast cancer participating in research via telehealth. Rural Remote Health. 2019;19:5269. doi: 10.22605/RRH5269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sharma JJ, Gross G, Sharma P. Extending oncology clinical services to rural areas of Texas via teleoncology. J Oncol Pract. 2012;8:68. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2011.000436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Torbjørnsen A, Småstuen MC, Jenum AK, Årsand E, Ribu L. The service user technology acceptability questionnaire: psychometric evaluation of the Norwegian version. JMIR Human Factors. 2018;5:e10255. doi: 10.2196/10255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hirani SP, Rixon L, Beynon M, Cartwright M, Cleanthous S, Selva A, et al. Quantifying beliefs regarding telehealth: development of the whole systems demonstrator service user technology acceptability questionnaire. J Telemed Telecare. 2017;23:460–469. doi: 10.1177/1357633X16649531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]