Pain is a signal of distress in the body. It can erode one’s ability to work or to enjoy life. Some people try to numb pain with painkillers, illicit drugs, and alcohol, and intolerable pain is implicated in suicide and other deaths of despair (1–3). Pain is commonly triggered by disease or an impairment in physical functioning. However, pain can also be triggered by social or psychological distress (4). It is widely believed that pain rises with age as disease, deterioration, and stress take their toll on the body. In their PNAS article “Decoding the mystery of American pain reveals a warning for the future,” Case et al. (5) investigate an irregular feature of the relationship between pain and age in present-day America—midlife individuals report higher levels of pain than do the elderly. Ominously, this inverted age–pain profile exists only for individuals without a bachelor’s degree (BA) and in no wealthy country other than America (5).

Case et al. (5) solve the mystery of the inverted age–pain profile with cohort analysis. That is, if one follows the same birth cohort as it ages, pain prevalence does indeed rise with age, as expected. However, if one compares birth cohorts across time, the cohorts born more recently report more pain—at every age. To put it another way, at every age less educated people in America report more pain today than people the same age did in the past. This cohort pattern generates the inverted age–pain relationship because at the present time, birth cohorts born more recently (who are in more pain) are younger than the birth cohorts born long ago (who are in less pain). The authors make their case by marshaling large, nationally representative survey datasets from Gallup US and World Poll, and they corroborate the finding in other large survey datasets from the United States and Europe.

This is a consequential sequel to the 2015 article in PNAS by Case and Deaton (2), which called attention to the alarming increase in “deaths of despair” among middle-aged, non-Hispanic Whites since 1999, especially those without a BA. Case et al. (5) reveal that less educated Americans are not just hurting in middle age. They are hurting at every age and more so in each successive cohort than the last.

This is not a small group or a small effect. The majority of Americans, some 65%, do not have a BA (6). In 2016, ∼23% of non-BA holders ages 18 and older (from all birth cohorts) experienced pain that had lasted for at least 3 mo (compared with just 12% of those with a BA) (7), but as Case et al. (5) show, that point-in-time average masks a dramatic 21-percentage point increase in the prevalence of pain as one moves from the birth cohort of 1950 to 1990.

It is hard to overstate the significance of this finding. Its implications are far reaching and dismal. For one, people in pain are often unable to work. Causation runs the other way as well, where loss of work leads to psychological distress and often pain. Indeed, pain is implicated in the troubling decline in employment among American men over the last several decades. Forty-three percent of prime-age men who are not in the labor force have a serious health condition, and nearly half report daily use of painkillers (8). They also report emotional distress and low life satisfaction (8). About 25 to 35% are receiving Social Security Disability Insurance (DI) benefits, which bring automatic qualification for Medicare (8). Musculoskeletal problems (e.g., back pain) and mental health diagnoses are the most common reasons for receiving disability benefits. Nearly all applicants cite pain in their applications, and not surprisingly, over 20% of DI beneficiaries take opioid painkillers regularly (9). The DI program has grown rapidly since it was created in 1956, but recent years have brought a decline in caseload and fiscal relief, as the outsized baby boom cohort exited DI for the Social Security retirement program and as policy changes made screening more stringent. The rise in pain among later-born cohorts raises doubt about whether the downward caseload trend can continue, although it also raises concern for the people applying for DI today, who appear sicker but face a markedly lower award rate than did earlier-born cohorts.

The widening gap in pain between the more and less educated is yet another manifestation of health inequities in America, which arise from our long history of racial, social, and economic inequality. People without a BA are more likely to lose their jobs and more likely to experience pain from serious health conditions, and if they are employed, their low-paying, physically demanding jobs are more likely to cause them pain. In contrast, people with a BA, for example, have borne relatively little of the employment losses from the COVID-19 pandemic (10), they experience comparatively little pain, and their well-paying, less physically demanding jobs are less likely to be a source of their pain.

If less educated, prime-age Americans are unable to work or are less productive at work because they are in pain, the nation’s economic future is at stake. Although it is hard to see it from inside the COVID-19 economic recession, America needs workers to fuel economic growth and preserve the standard of living that many, although not all, enjoy. The long arc of population aging has slowed labor force growth and also, productivity growth, imposing a drag on economic growth (11).

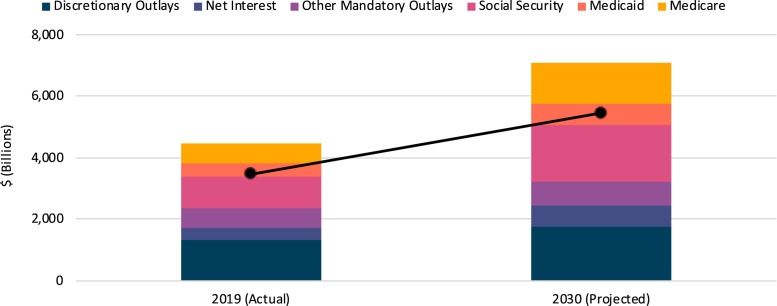

Compounding matters, the rise of pain among the less educated has vast implications for health care for the foreseeable future. The problem with health care in America is that it costs too much, in absolute terms and relative to the value it provides or the resources available to pay for it. Total health care spending (public and private) has been growing faster than gross domestic product (GDP) (what we produce as a nation) and at present, eats up almost 18% of GDP (12), far more than in other wealthy countries (13). Medicare, Medicaid, and other federal health care programs account for nearly one-third of this spending (14). Fig. 1 shows that, by 2030, federal spending will greatly outpace tax revenues, and nearly all of the spending will be devoted to “mandatory” spending items like these—that is, bills that must be paid because benefits were earned (Medicare and Social Security), eligibility criteria were met (Medicaid), or money was borrowed (interest on federal debt) (14). Mandatory spending edges out “discretionary” spending on other national priorities like education, infrastructure and roads, national defense, and climate change.

Fig. 1.

Federal outlays and revenues compared in 2019 and 2030. Data are from the Congressional Budget Office (14). Bars represent outlays in 2019 and 2030, while endpoints of black line denote revenues in the same years.

Medicare is already under significant cost pressure from population aging. Most Americans become eligible for Medicare at age 65. By 2030, one in every five Americans will be age 65 or older, up from one in every six today (15). The COVID-19 pandemic has made the situation worse, exacerbating the program’s financing challenges (16). If, as Case et al. (5) tell us, the future elderly population is likely to be sicker than the current elderly, this will add further pressure to Medicare’s financing crisis. The pressure packs a double punch: to the degree people in pain work less than they would if they were not in pain, they will contribute less in taxes during their working years but need more health care services when they are older.

Medicaid is already bearing costs of care for many in this population. Now the largest public health insurance program in the United States, Medicaid covers one in five Americans (17), all of whom are low income. Medicaid is jointly financed by the federal government and the states from general tax revenues, and states are required to cover all who qualify. As Medicaid grows, states increasingly struggle to balance their budgets, a task made more arduous by the fact that states (unlike the federal government) cannot borrow to finance budget shortfalls. On average, Medicaid accounts for 29% of state budgets, more than states spend on education (18). However, there is another, perhaps even more consequential way in which Medicaid will be impacted. Medicaid is the federal health insurance program that finances long-term care. If the elevated pain experienced by less educated Americans today foretells elevated rates of impairment and reduced function with age, then Medicaid will bear a double burden.

Could American health care be part of the solution to the American pain crisis? This is doubtful. So far, the American approach to pain treatment has been to first ignore it and then to overtreat it with dangerously addictive opioids. With all of the crises that beset the country at the moment, it is easy to forget that America is still in the midst of a tragic opioid epidemic. Over 71,000 lives were lost in 2019, an increase of 5% since December 2018 (19). Tragically, there is now evidence that long-term use of opioid painkillers makes pain worse, not better (20).

The story of the opioid epidemic illustrates how pain is both a cause of labor force nonparticipation and a consequence of nonparticipation. In their book, Case and Deaton (3) delve into the many ways in which social and economic conditions have deteriorated for the less educated in America, who have been sidelined from the labor market, ironically they argue, in no small part because of unsustainable health care costs in the employment-based, private health insurance system.

However, in case educated readers think they are immune to the personal, social, and economic tragedies that lie behind the pain gap, the interconnectedness of our economic lives signals that the plight of less educated Americans is the plight of us all. Case et al. (5) offer a stark warning for the future that all should take note of.

Footnotes

The author declares no competing interest.

See companion article, “Decoding the mystery of American pain reveals a warning for the future,” 10.1073/pnas.2012350117.

References

- 1.Case A., Deaton A., “Suicide, age, and well-being: An empirical investigation” in Insights in the Economics of Aging, Wise D., Ed. (University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL, 2017), pp. 307–334. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Case A., Deaton A., Rising morbidity and mortality in midlife among white non-Hispanic Americans in the 21st century. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, 15078–15083 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Case A., Deaton A., Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism, (Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, 2020). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eisenberger N. I., Social pain and the brain: Controversies, questions, and where to go from here. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 66, 601–629 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Case A., Deaton A., Stone A.A., Decoding the mystery of American pain reveals a warning for the future. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 117, 24785–24789 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.US Census Bureau , Number of people with master’s and doctoral degree doubles since 2000 (2019). https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2019/02/number-of-people-with-masters-and-phd-degrees-double-since-2000.html. Accessed 17 September 2020.

- 7.Dahlhamer Jet al., Prevalence of chronic pain and high-impact chronic pain among adults—United States, 2016. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 67, 1001–1006 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krueger A. B., Where have all the workers gone? An inquiry into the decline of the U.S. labor force participation rate. Brookings Pap. Econ. Act. 2017, 1–87 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morden N. E.et al., Prescription opioid use among disabled Medicare beneficiaries: Intensity, trends, and regional variation. Med. Care 52, 852–859 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.US Bureau of Labor Statistics , The employment situation, Aug 2020 (2020). https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/empsit.pdf. Accessed 9 September 2020.

- 11.Maestas N., Mullen K. M., Powell D., “The effect of population aging on economic growth, the labor force and productivity” (Rep. w22452, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA, 2016).

- 12.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services , National Health Expenditure Fact Sheet (2018). https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NHE-Fact-Sheet. Accessed 17 September 2020.

- 13.Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development , OECD health expenditure and financing data (2019). https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=SHA. Accessed 10 October 2019.

- 14.Congressional Budget Office , An update to the budget outlook: 2020 to 2030 (2020). https://www.cbo.gov/publication/56542. Accessed 17 September 2020.

- 15.US Census Bureau , An aging nation: The older population in the United States (2014). https://www.census.gov/prod/2014pubs/p25-1140.pdf. Accessed 17 September 2020.

- 16.Congressional Budget Office , The outlook for major federal trust funds: 2020 to 2030 (2020). https://www.cbo.gov/publication/56523. Accessed 17 September 2020.

- 17.Rudowitz R., Garfield R., Hinton E., 10 things to know about Medicaid: Setting the facts straight. Kaiser Family Foundation (2019). https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/10-things-to-know-about-medicaid-setting-the-facts-straight/. Accessed 17 September 2020.

- 18.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services , Medicaid facts and figures (2018). https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/medicaid-facts-and-figures. Accessed 17 September 2020.

- 19.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention , Provisional drug overdose death counts (2020). https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/drug-overdose-data.htm. Accessed 17 September 2020.

- 20.Ballantyne J. C., Mao J., Opioid therapy for chronic pain. N. Engl. J. Med. 349, 1943–1953 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]