Significance

The Mount Samalas eruption in 1257, one of the largest explosive volcanic eruptions in the Common Era, has proven a complex case for climate models which have generally overestimated the climate response compared with proxy data. Here we perform Earth system model simulations of the impacts of the Mount Samalas eruption using a range of and halogen emission scenarios. Reported halogen emissions are considerable from the eruption, but using our model simulations and reconstructed climate response we can rule out all but minor halogen emissions reaching the stratosphere. Including a minor fraction of the halogen inventory reaching the stratosphere captures the observed “muted” climate response but results in significant ozone depletion with implications for ultraviolet exposure and human health.

Keywords: Samalas, climate, ozone, modeling volcanic impacts

Abstract

The 1257 CE eruption of Mount Samalas (Indonesia) is the source of the largest stratospheric injection of volcanic gases in the Common Era. Sulfur dioxide emissions produced sulfate aerosols that cooled Earth’s climate with a range of impacts on society. The coemission of halogenated species has also been speculated to have led to wide-scale ozone depletion. Here we present simulations from HadGEM3-ES, a fully coupled Earth system model, with interactive atmospheric chemistry and a microphysical treatment of sulfate aerosol, used to assess the chemical and climate impacts from the injection of sulfur and halogen species into the stratosphere as a result of the Mt. Samalas eruption. While our model simulations support a surface air temperature response to the eruption of the order of −1°C, performing well against multiple reconstructions of surface temperature from tree-ring records, we find little evidence to support significant injections of halogens into the stratosphere. Including modest fractions of the halogen emissions reported from Mt. Samalas leads to significant impacts on the composition of the atmosphere and on surface temperature. As little as 20% of the halogen inventory from Mt. Samalas reaching the stratosphere would result in catastrophic ozone depletion, extending the surface cooling caused by the eruption. However, based on available proxy records of surface temperature changes, our model results support only very minor fractions (1%) of the halogen inventory reaching the stratosphere and suggest that further constraints are needed to fully resolve the issue.

The eruption of Mount Samalas in 1257 (Indonesia), with Volcanic Explosivity Index (VEI) 7, was identified by Lavigne et al. (1) as the source of the largest sulfate spike of the Common Era in both Greenland and Antarctica ice cores (2, 3). Analyses of erupted products and their melt inclusions suggests that the eruption released 15812 megatons (Tg) of sulfur dioxide (), together with 22718 Tg of chlorine (Cl) and up to 1.3 Tg of bromine (Br) (4), making it responsible for the emissions of the greatest quantity of volcanic gases into the stratosphere in the Common Era (4–6).

Tree-ring proxy records and historical narratives point toward a strong surface cooling in the Northern Hemisphere following the eruption, in the summer of 1258 (1, 7, 8). Contemporary narrative sources suggest an unusually cloudy, rainy, and cold summer in Europe in 1258 (1, 7). The climatic impact of the eruption is suspected to have amplified famines and political turmoil in Europe and Japan, with the most severe socioeconomic consequences reported in England (7, 9, 10).

Given the magnitude of the eruption and the scale of the societal impacts a number of previous climate modeling studies have investigated the climate response to the 1257 Mt. Samalas eruption. However, when compared with observations or proxy records (11–13), most previous simulations overestimate the surface cooling response to Mt. Samalas and other large eruptions (14). Despite the 1257 eruption of Mt. Samalas emitting 1.8 times more than the 1815 eruption of Mt. Tambora, the Northern Hemisphere temperature response, reconstructed by tree-ring maximum latewood density (MXD) methods, is relatively similar (7, 8). This has been a puzzle for the climate modeling community. Timmreck et al. (15) and Stoffel et al. (8) were able to simulate a broad agreement between their Atmosphere Ocean General Circulation Model (AO-GCM) simulations and tree-ring based reconstructions, but Stoffel et al. have shown that the surface temperature response was very sensitive to the assumed eruption month and the height of injection (8), while Timmreck et al. found that the size of the prescribed aerosol effective radii were very important (15).

Both the changes in aerosol number concentrations and size and gas-phase composition (chemistry) are important aspects of the role of large injections of sulfur (like those from Mt. Samalas) on climate (16, 17). Changes in aerosol properties and changes in chemistry are strongly coupled. Large eruptions, like Mt. Samalas, can inject their volatile gases into the stratosphere. In this region, volcanic sulfate aerosols [which scatter back sunlight and cool the planet (18)] are formed from the oxidation of in the gas phase by the hydroxyl radical (OH). Volcanic sulfate aerosols grow through microphysical processes of condensation and coagulation (19), with the size of the aerosols being important for their climate effects (20). There is an important self-limiting effect of sulfur oxidation in the stratosphere (17, 21). As the size of the injected into the stratosphere increases, the ability of the OH to react with decreases, slowing down the rate of aerosol production, causing sulfate to be produced over a longer time period, and leading to a longer-lived forcing. In addition, the reduction in OH can cause levels of ozone to increase in the lower stratosphere (21) where it can act as a climate-warming agent.

One aspect that affects our understanding of the effects of the Mt. Samalas eruption, and potentially other future eruptions, is in the role of coemitted halogens. The impacts of volcanic halogens on stratospheric ozone were first discussed by Stolarski and Cicerone (22). When halogens enter the stratosphere they contribute to the catalytic destruction of ozone (23) and lead to commensurate impacts on the composition and chemistry of the troposphere. Tie and Brasseur (24) showed that there is significant sensitivity in the response of stratospheric ozone following eruptions the size of 1991 Mt. Pinatubo eruption to the background chlorine levels. Kutterolf et al. (25) provided renewed interest in the topic of volcanic halogens and several studies have recently been published using a range of models and model setups (26–31) that have also identified important sensitivities to greenhouse gas loading and levels of short-lived bromine compounds (e.g., ref. 31). Vidal et al. (4) identified extremely large releases of halogens from the Mt. Samalas eruption, which could have significantly affected the stratospheric ozone burden. However, in-plume dynamics governing the injection of halogens into the stratosphere are poorly understood, and the current understanding of these remains limited to the few explosive eruptions monitored in the satellite era (32). None of the previous modeling setups used in the studies described above allowed for the investigation of combinations of emissions of sulfur and halogens from the 1257 Mt. Samalas eruption and the commensurate impacts of these on surface weather and climate.

Using eruption source parameters calculated by Vidal et al. (4, 6) and a fully coupled Earth system model (an AO-GCM with interactive atmospheric chemistry and aerosol microphysics; see Materials and Methods), here we investigate the Earth system response to the 1257 Mt. Samalas eruption and determine through comparison with an array of proxy records whether the surface climate response can provide evidence for large-scale ozone depletion that would have been caused by the coemissions of volcanic halogens (4).

Four emissions scenarios were developed based on scalings of the budget of Vidal et al. (4) (Table 1). These scenarios reflect the uncertainty in the amount of emitted from the eruption reaching the stratosphere obtained by comparing degassing budgets reconstructed from the eruption deposits with ice core records (3) and account for conservative minimum [1% of the estimates of Vidal et al. (4)] and maximum [20% of the estimates of Vidal et al. (4)] stratospheric injections of Cl and Br, reflecting results obtained through experimental modeling and satellite observations (32, 33).

Table 1.

Summary of experiments performed to reconcile the climate and ozone response to the Mt. Samalas eruption

| Stratospheric injection | |||||

| Ensemble | , Tg | HCl, Tg | HBr, Tg | ||

| HI-HAL (20%) | 6 | 142.2 | 46.68 | 0.263 | |

| LO-HAL (1%) | 6 | 94.8 | 2.33 | 0.013 | |

| BOTH- | HI- (90%) | 6 | 142.2 | 0.00 | 0.000 |

| BOTH- | LO- (60%) | 6 | 94.8 | 0.00 | 0.000 |

Nsims refers to the number of ensemble members performed for each set of simulations. In all simulations the same day of year and altitude is used to inject the volatile gases from the eruption of Mt. Samalas. BOTH-SO2 refers to the SO2 only experiments, which are averaged in further analysis. Percentages indicate the fraction of emissions compared to those estimated in ref. 4.

As a prior study showed best model agreement for modeled surface temperature with reconstructed surface temperature from tree rings was with an eruption occurring between May and July (8), a 1 June eruption was selected for our simulations at the latitude and longitude corresponding to the location of Mt. Samalas (8.5○S, 116.3○E). The gases listed in Table 1 were injected between 19-km and 34-km altitude (Materials and Methods).

For each of the emissions scenarios six simulations were performed (ensemble members) to investigate the role of internal variability. These ensemble members were initialized from a long preindustrial control run (PI control) using starting conditions spanning a range of El Niño Southern Oscillation and Quasi-Biennial Oscillation (QBO) states (SI Appendix, Table S1).

The results from our HadGEM3-ES simulations are compared against results from the CESM-Last Millennium Ensemble (CESM-LME) (34) and multimodel ensembles from the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase V/Paleoclimate Model Intercomparison Project Phase III (CMIP5/PMIP3) Past1000 experiment (hereafter CMIP5) (35) and evaluated against a range of tree-ring records and other evidence described below (see Materials and Methods for discussion on the tree-ring records).

Results

Surface Climate Response.

Our Earth system model results show that following the eruption of Mt. Samalas a complex cascade of physical and chemical processes occurred. These involved chemical oxidative processes (changes to the amount of ozone and hydroxyl radicals) and aerosol microphysical processes, which combined to affect the physical climate system [see Robock (18) and references therein for details of these processes]. Our results confirm that using the estimates of emissions from Vidal et al. (6) we are able to recreate a surface climate response that is consistent with climate proxies and that inclusion of coinjected halogens significantly alters the composition of the atmosphere with knock-on effects for the simulation of the climate response.

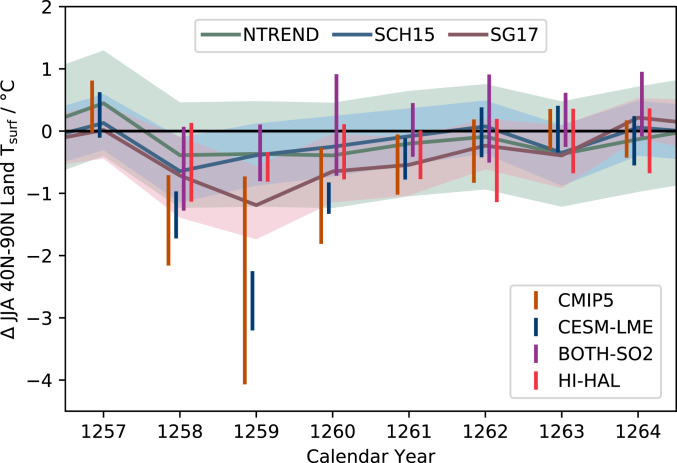

We begin by assessing the surface temperature response between the CMIP5, CESM-LME, and HadGEM3-ES ensembles with a selection of tree-ring reconstructions from Wilson et al. (36) (the Northern Hemisphere Tree-Ring Network Development; N-TREND), Schneider et al. (37) (SCH15), and Guillet et al. (7) (SG17), shown in Fig. 1. For simplicity, the HadGEM3-ES data in Fig. 1 focus on the HI-HAL simulations and the mean of the HI- and LO- ensembles (hereafter BOTH-). The LO-HAL simulations fall within the range of BOTH-. The model data presented in Fig. 1 show the range of results (maximum to minimum) and highlight a significant spread in the response in the simulations.

Fig. 1.

Reconstructed and simulated boreal summer (June, July, and August, JJA) N- N land surface air temperature. Reconstructed temperatures come from three different records [(7, 36, 37)], with the mean values for each record indicated with solid lines and uncertainty range (1 SD) denoted with shading. The ranges (maximum to minimum) of simulated to 90○ N land surface temperature for CMIP5, CESM-LME, and HadGEM3-ES (BOTH- and HI-HAL) ensembles are indicated as vertical bars and are calculated as anomalies relative to the preeruption climatologies of the individual models.

Fig. 1 shows that all three of the land surface temperature reconstructions suggest the cooling from the eruption of Mt. Samalas was only around 1 K over the Northern Hemisphere in the boreal summer. The cooling is strongest in the Guillet et al. (7) dataset, reaching almost 1.7 K and lasting for up to 5 y. Our HadGEM3-ES model results are in excellent agreement with the temperature reconstructions for 1258 for all proxy datasets but fail to capture the reduction in surface air temperature reconstructed between 1258 and 1259 by Guillet et al. (7). However, both the model results and proxy data show that there is considerable variability in surface temperature in the wake of the eruption of Mt. Samalas. The variability from the model results comes from the internal variability of the climate system simulated by the different ensemble members (with different initial conditions) and the variability from the different assumptions around the emissions. The variability from the proxy data, however, comes about from the uncertainty in the experimental techniques of reconstructing past temperatures and the uncertainty from local effects. Indeed, of the 24 simulations we performed there were several ensemble members that showed warming in the region of the temperature proxy data (SI Appendix, Fig. S1.)

Fig. 1 shows clearly that the CMIP5 and CESM-LME simulations result in surface temperatures much lower than our HadGEM3-ES simulations in 1259 and in addition much lower than any of the reconstructed temperatures. While there is variability and so uncertainty in the surface temperature reconstructions presented in Fig. 1, these data place a lower bound on the extent and timing of cooling. As such we are able to exclude many of the CMIP5 model simulations and all of the CESM-LME simulations as lying outside the reconstructed temperature anomalies. While none of the HadGEM3-ES simulations can be excluded by this metric, simulations of warmer temperature anomalies in 1258 and 1259 in particular could potentially be excluded as not representing an appropriate climate response.

The different HadGEM3-ES ensembles show variability in the simulated climate response, owing both to the internal climate variability (the variability from the ensemble members in each experiment) and variability from the different forcings applied in each experiment (i.e., halogen and sulfur loading). The 12 experiments where we varied only the amount of injected from Mt. Samalas (BOTH-) show a rapid recovery, within 3 y in most cases (SI Appendix, Fig. S1), with individual ensemble members agreeing well with the spatial distribution of warming and cooling reconstructed by Guillet et al. (7). Several of the ensemble members end up giving a warming in the years subsequent to the eruption (1260 onward) (Fig. 1). In the HI-HAL simulations the duration of cooling is shown to be extended in Fig. 1, with very little (if any) sign of warming in the years after the eruption.

Hartl-Meier et al. (14) showed that many CMIP5 simulations resulted in too strong a cooling response to the 1257 Mt. Samalas eruption. This is also the case for CESM-LME (34) and is likely connected with the timing and manner in which these models simulated the eruption [i.e., this could be due to the imposed radiative forcing, which is stronger in 1259 in the Gao et al. (38) reconstruction].

Our simulations therefore stand out from these earlier studies as showing very muted cooling in 1259. In their simulations forced with two-dimensional aerosol climatologies, Stoffel et al. (8) were also unable to simulate cooler temperatures in 1259 than 1258 in the ensemble mean. This is consistent with radiative forcing peaking the year after the eruption and then reducing rapidly due to aerosol sedimentation following the decreased residence time from microphysical growth of particles in the volcanic cloud (and increase in effective radius; see SI Appendix, Fig. S3B). This supports the climate response in the Schneider et al. (37) reconstruction, as this is weaker in 1259 than 1258 and puts into question the cooling in 1259 found by Guillet et al. (7).

Our HadGEM3-ES simulations show that there is a general agreement between the magnitude of cooling in tree-ring records and climate models, using an appropriate choice for loading. The use of a climate forcing scaled linearly from ice core deposition (38) in a large number of studies (e.g., ref. 34) is clearly inappropriate due to long-known self-limiting processes associated with larger magnitude of sulfur dioxide injection leading to larger aerosol sizes (16, 20). This leads to an overestimation of the climatic cooling response to Mt. Samalas in the CESM-LME simulations, and possibly other large volcanic eruptions (39). Taken together the results presented here (and in SI Appendix) suggest that caution should be exercised when using CESM-LME results to assess the role of volcanic forcing in 13th-century climate change.

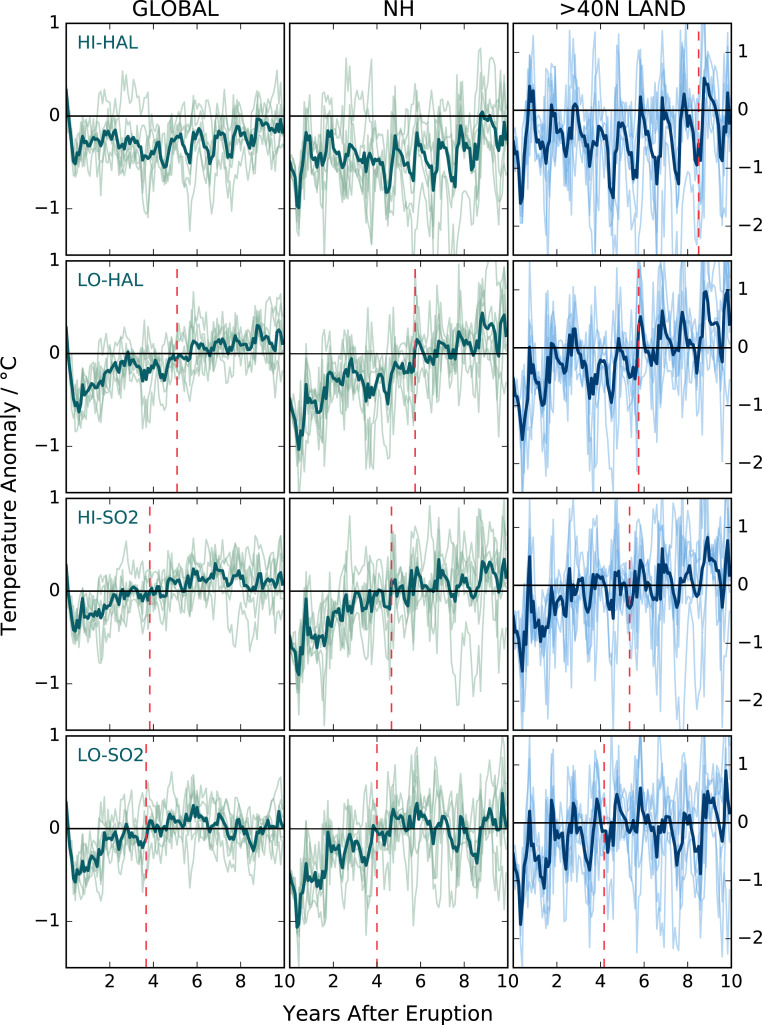

Fig. 2 shows the results for the global surface temperature response following the eruption of Salamas. Fig. 2 highlights that the return date, the time at which there is a positive anomaly in surface temperature for 12 mo following the eruption, is very sensitive to the experiment performed. At the global and Northern Hemisphere scales, the HI-HAL simulation does not result in a return to pre-Samalas-eruption conditions within the 10 y we analyzed. It is only in the Northern Hemisphere over land that the simulations show a return to pre-Samalas-eruption conditions, but this is not until 8 y after the eruption. Conversely, the LO-HAL and BOTH- simulations all return back to pre-Samalas-eruption climate conditions within 6 y. These data suggest that it is very unlikely that the amount of halogens injected into the stratosphere in the HI-HAL simulation are reflective of what happened. However, the LO-HAL simulation cannot be ruled out. Moreover, there are a number of important processes with potential societal impacts associated with the HI- and LO-HAL simulations which we discuss below.

Fig. 2.

Global (Left), Northern Hemisphere (Center), and to 90○ N land (Right) monthly mean surface air temperature anomalies simulated for each HadGEM3-ES simulation (light) and ensemble mean (dark). The x axis (time) starts at year zero, that is, at the point of the eruption, and continues after the eruption. The dark lines indicate the ensemble mean results for each of the HadGEM3-ES experiments, with individual ensemble members plotted as faint lines. Return dates, the time it takes for there to be a positive anomaly in surface temperature for the ensemble mean, are indicated as red dashed lines in each panel. Note the expanded temperature scale for N land, indicated in blue.

Composition and Forcing in HadGEM3-ES.

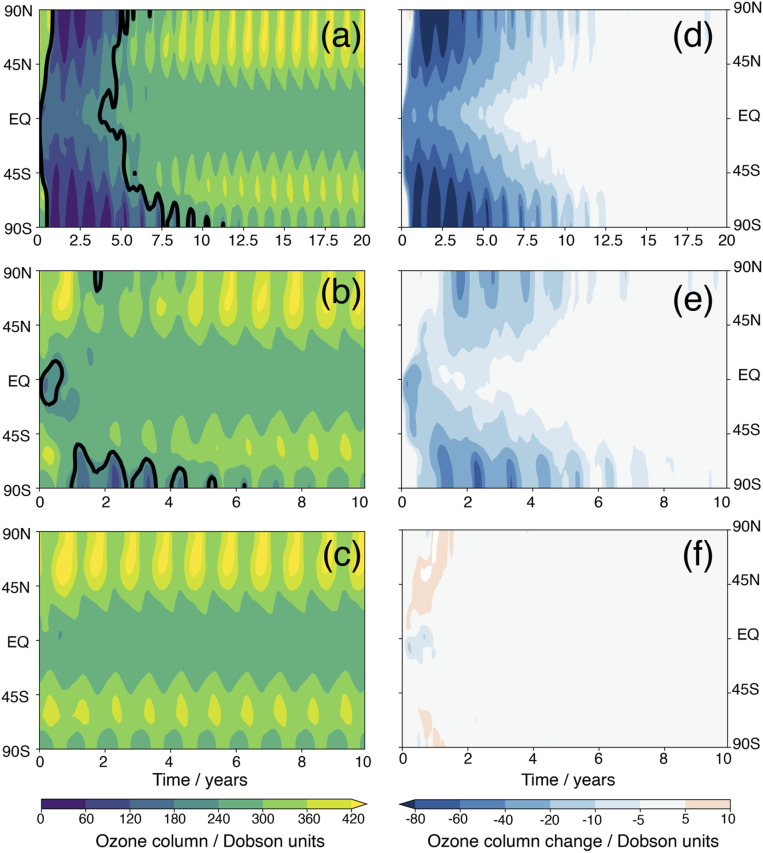

The ozone response to the injection of stratospheric is expected to depend on the background chemical state and the magnitude of the halogen injection (24, 40). Fig. 3 shows the zonal mean ozone column for the HI-HAL, LO-HAL, and BOTH- simulations. Ozone differences from the climatological mean of the unperturbed PI control are also shown in Fig. 3. For the HI-HAL case, the global mean ozone column drops by 242 Dobson units (DU), a 75% decrease from the unperturbed case. This represents near-total stratospheric ozone loss. Tropical ozone depletion remains for around 4 y after the eruption, where tropical column ozone drops below 180 DU. At high latitudes the ozone loss is greater and persists for longer, particularly in the Southern Hemisphere where ozone depletion (using a 220 DU definition) takes place up to a decade later. These results are broadly consistent with previous modeling studies [e.g., Tie and Brasseur (24)] and a very recent study by Ming et al. (28) and implies that the surface climate response calculated here is representative of ozone perturbations calculated with other models.

Fig. 3.

(Left) Ensemble mean simulated zonal mean ozone column for (A) HI-HAL, (B) LO-HAL, and (C) BOTH-. The black contour indicates the 220 DU isoline. (Right) Ensemble mean simulated zonal mean ozone column change for (D) HI-HAL, (E) LO-HAL, and (F) BOTH-. Differences that are not significant at the 95% confidence interval according to the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test are indicated with stipples.

In the more conservative LO-HAL scenario, there is a latitudinal dependence in the ozone response, with decreases in the tropics and increases in the extratropical midlatitudes. Tropical ozone depletion occurs only in the year following the eruption, with more limited Northern Hemisphere ozone loss. However, global mean ozone columns reduce by 25% 2 y after the eruption, representing a peak of 81 DU reduction. Declines in ozone are more persistent in the Southern Hemisphere, where ozone depletion still takes place up to 6 y after the eruption. Meanwhile, global mean column ozone increases in BOTH- by 4% at the peak, 12 mo after the eruption.

The latitudinal dependence of the ozone changes in the BOTH- scenario suggests a dynamical response to the aerosol heating (e.g., ref. 41). SI Appendix, Fig. S2 shows the change in residual mean vertical velocity meridional circulation, * at 70 hPa. * increases in the tropics (in a region of upwelling) and decreases in the extratropics (in a region of downwelling). This suggests a more vigorous Brewer–Dobson circulation in response to the injections of which brings up ozone poor air from the troposphere and increases transport of air masses away from ozone producing regions. In addition, the changes in * are sensitive to the magnitude of injected (SI Appendix, Fig. S2)—with HI- showing larger changes in * than LO- (driven by the increase in aerosol loading and heating). In any case, the ozone column would otherwise be expected to increase in BOTH- due to chemical feedbacks—heterogeneous reaction of on sulfate aerosol leads to a reduction in reactive nitrogen which reduces ozone depletion (24).

By contrast the sharp decreases in ozone column evident in HI-HAL and LO-HAL are indicative of chemical changes. The injection of HCl and HBr leads to reactive halogen species which can deplete ozone (40). The depletion of ozone resulting from these chemical changes (Fig. 3) is shown to have a further impact on * in the HI-HAL simulations (SI Appendix, Fig. S2).

These changes in the stratospheric oxidizing environment are important. They will have an effect not only on the climate through the direct changes in long-wave and short-wave radiation, primarily attributed to the changes in ozone, but also through the changes that ozone has on the formation and lifetime of aerosols in the stratosphere, as it is the oxidation of which leads to the formation of stratospheric sulfate aerosols that ultimately perturb Earth’s radiative budget in our simulations.

As the initial oxidation of by the hydroxyl radical (formed from ozone photolysis and subsequent reaction with water vapor) is the rate determining step in the production of stratospheric sulfate aerosols, the lifetime of () is a proxy for the rate of aerosol production. Here we use the e-folding time of —the time taken to reach 1/e of the initial injection of —to quantify this effect. The ensemble average lifetimes vary significantly across the simulations. is 102 d for the HI-HAL experiments, 68 d for the LO-HAL and HI- experiments, and 62 d for the LO- experiments.

The additional injection of from LO- to HI- leads to an increase in lifetime of 6 d, around the same as the injection of 1% halogens from LO- to LO-HAL. The 20% halogen emission, however, leads to a substantial increase in lifetime, from 68 to 102 d in HI-HAL. An increase in lifetime with the coemission of HCl is supported by model simulations of the Sarychev Peak volcano in 2009 (42).

Not surprisingly, the largest aerosol burden is simulated in the HI- case. For the LO- case, the peak in sulfate burden is simulated in December and is consistent with a 33% smaller injection size. The simulated peak effective radius is larger in the HI- case than the LO- case, 1.09 vs , which is consistent with a larger injection and an earlier peak in aerosol burden as larger aerosols sediment from the stratosphere more quickly. The additional halogens injected in the LO-HAL case compared to the LO- case lead to a small reduction in peak sulfate burden from 105 to 100 Tg while the aerosol effective radius is slightly reduced from 0.94 to ; however, this is within the variability between the different LO-HAL simulations. In the HI-HAL case the peak aerosol burden is substantially reduced to 80 Tg from 180 Tg, while effective particle radius drops to . In all cases these simulated aerosol size distributions are consistent with the 0.7 to that Timmreck et al. (15) employed to simulate a reasonable climate response to Mt. Samalas (SI Appendix, Fig. S3).

SI Appendix, Fig. S4 shows the LO- simulation predicts that the Mt. Samalas aerosol cloud caused an increase in top-of-atmosphere outgoing shortwave radiation, peaking around 20 W, but with a longwave effect at 80% of the magnitude of the solar dimming the outgoing longwave decreased by 17 (resulting in a net forcing around a factor of 4 greater than the effects of the 1991 Mt. Pinatubo eruption, e.g. ref. 43). This is due to the combination of scattering of shortwave radiation and the absorption of longwave radiation in the stratosphere. The shortwave and longwave contributions to the surface energy budget behave similarly (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). The surface energy budget also accounts for changes to sensible and latent heat fluxes, both positive (in the downward sense) in response to stratospheric aerosol. Sensible heat fluxes reduce in the upward direction in response to a cooler surface with respect to the troposphere and latent heat fluxes reduce in the upward direction as less water vapor is evaporated from the surface. SI Appendix, Fig. S4 shows the largest deviation in net surface shortwave radiation occurs for the HI- case, which is expected as it is a larger volcanic eruption. On the basis of this metric alone, we would expect the largest climatic cooling to be achieved with the HI- case and for HI-HAL to have the smallest climatic response. The top-of-atmosphere budgets (SI Appendix, Fig. S4, Left) show that while HI-HAL has a smaller peak in the top-of-atmosphere shortwave imbalance, the impact of the scenario on the shortwave (and net) radiative fluxes is extended compared to the HI- ensemble.

SI Appendix, Fig. S4C shows the change to top-of-atmosphere (Left) and surface (Right) net radiative budget change. Comparing this with the surface shortwave fluxes shows that the surface shortwave metric is insufficient to describe the changes to the surface radiative budget. When accounting for changes to longwave, sensible, and latent heat fluxes it is clear that all ensembles show a similar change to the surface radiative heat budget in the first year after the eruption. HI-HAL also shows an extended cooling, with negative net surface radiative flux anomalies up to 4 y after the eruption. This is due to the shorter residence time of sulfur in the stratosphere than halogens because sulfate aerosols sediment out of the stratosphere on timescales shorter than stratospheric circulation timescales. As a result, the impacts of the halogens persist longer. This would suggest that the short-term climate response to the different emissions scenarios should be similar.

Potential Societal Impacts.

The changes to atmospheric composition and climate in the aftermath of the 1257 Mt. Samalas eruption may be linked to the environmental and societal changes reported in several regions of the Northern Hemisphere in the years following the eruption (7, 9, 10).

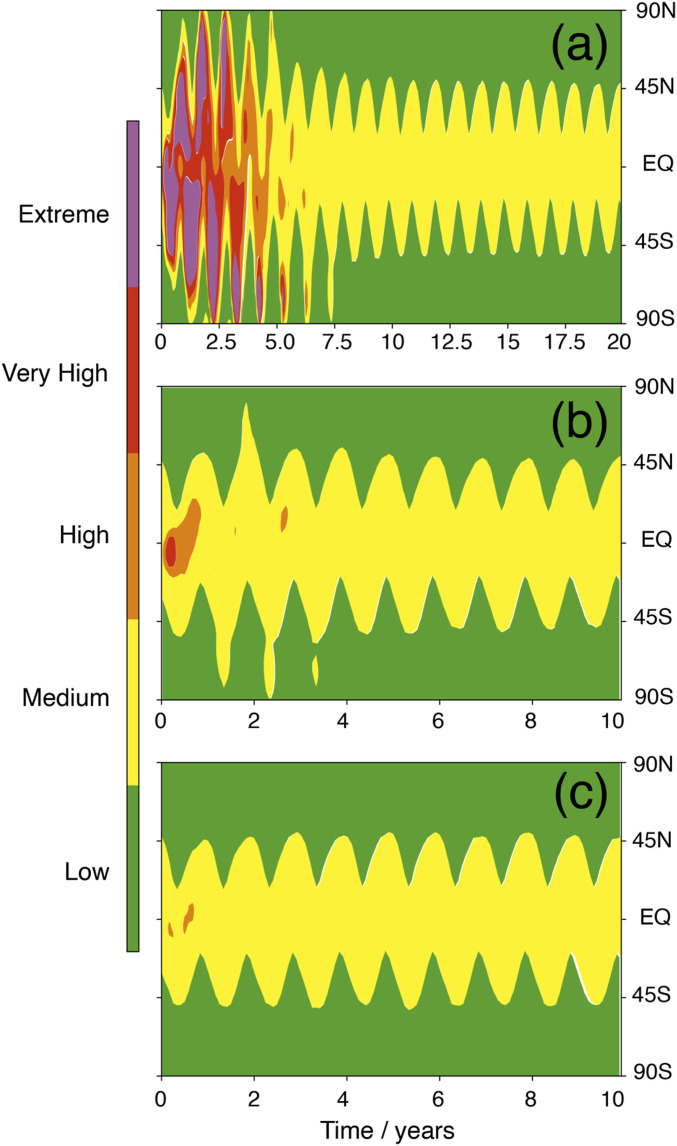

Ozone depletion can lead to an increase in surface ultraviolet (UV) radiation which can have adverse effects on living beings at different timescales, including immediate immunosuppression that favors infectious diseases (44), ocular diseases, and, on the longer term, skin cancer (45, 46). Climate modeling and environmental proxies showed that the gas emissions during the emplacement of Siberian Trap flood basalts lead to ozone depletion and temperature changes which could have caused stressed ecosystems and DNA mutations that would have contributed to the end-Permian extinction (47). A way to quantify the intensity of the UV exposure at the surface is the clear-sky UV index, given by

| [1] |

according to Madronich (48), where is the cosine of the solar zenith angle and is the total vertical ozone column (in Dobson units). The 12.5 is a unitless scaling factor. This equation only accounts for changes to ozone column and neglects aerosol and cloud changes. Fig. 4 shows the daily-mean average UV index colored by World Health Organization categories (Low [0 to 2], Medium [3 to 5], High [6 to 7], Very High [8 to 10], and Extreme [11+]) in the aftermath of the 1257 Mt. Samalas eruption for the high-, low-, and no-halogen scenarios. In the HI-HAL scenario, high or extreme UV levels would be expected for much of the extratropics in the four summers following the eruption, that is, until 1261. Assessment of changes to surface UV is made more challenging by the presence of volcanic aerosols, which also scatter UV radiation. However, it is worth noting that similarly to the case for visible light, scattering peaks when the diameter of the particle is of the order of the wavelength of radiation. Damaging UVB and UVC radiation will then be scattered even less effectively than visible light for the larger aerosol size distributions. Such a scenario could have caused immediate immunosuppression and epidemic outbreaks in civilizations from the equator to medium latitudes, as well as increased ocular diseases. Since famine also causes increased infectious diseases due to immunosuppression, it is difficult to distinguish whether the mass death toll in the mid-13th century (9) in Europe and Japan would be partly linked to ozone depletion. However, European and Asian historical archives show that death tolls significantly drop down in 1259, with a return to preeruption numbers in 1260 (10). Similarly, the epidemic outbreaks among the troops of the Song Dynasty of China that led to the victory of Mongol Emperor Möngke Khan in 1259 (49) were not followed by further epidemics. This would be inconsistent with extreme UV index lasting until 1261. Investigation of environmental proxies sensitive to UVB change such as pollen or coral would allow further confirmation of this hypothesis.

Fig. 4.

Daytime-mean clear-sky UV index for (A) HI-HAL, (B) LO-HAL, and (C) BOTH-.

A low injection of halogens would have caused a high UV index at the Equator in the year following the eruption (Fig. 4) and medium UV index at high latitude in the first 3 y. However, historical records for the region and proxies are lacking to confirm that localized ozone depletion affected the equatorial regions after the 1257 Mt. Samalas eruption.

Discussion.

Our results suggest that it is unlikely that emissions associated with the HI-HAL simulation are accurate for Mt. Samalas. However, we cannot rule out the emissions associated with the LO-HAL scenario, which still results in significant ozone depletion. This suggests that stratospheric injections of 20% of the halogen inventory of an eruption are very unlikely. Ozone depletion in the stratosphere would be expected to increase tropospheric OH and therefore lead to faster removal of and (50). Combined with cooler global temperatures, which would reduce biological emissions of and , mixing ratios of these chemical constituents would be expected to drop further. In addition, deposition of sulfate has been shown to reduce emissions from wetland sources (51). In the modeling setup used, and were held at lower boundary conditions, so are heavily constrained.

Including , and particularly , emissions would be too computationally intensive. However, records of these greenhouse gases in the ice core record could yield some insights into the chemical perturbation associated with the eruption. Very recently Ming et al. (28) have shown that one of the best candidates for an ozone-depletion signal, the stable isotopic composition of nitrate (delta 15 in nitrate), was obscured by interannual variability in the ice core samples they analyzed from Antarctica. However, based on these isotope data they were able to conclude that it was unlikely that the Mt. Samalas 1257 eruption injected enough HCl to cause complete ozone removal over Antarctica.

Shorter-lived trace gases may also give some insights into tropospheric changes. Increases in OH in the troposphere (as a result of decreases in overhead ozone columns in the stratosphere) could lead to short-term increases in hydrogen peroxide (); however, analysis of the Tunu (Greenland) record do not show increases in at this time (52). Changes in surface UV, linked to the stratospheric ozone changes which were particular marked in the HI- scenario, would be expected to lead to an increase in the incidence of cataracts or skin cancer. No evidence for such an increase in skin-cancer incidence exists to date; however, longevity was much lower in the 13th century. While UK aristocrats who reached 21 y of age could be expected to reach 64 y of age in the 13th century (53), life expectancy for the working classes would be much lower, preventing skin cancers, developing at a later stage of life, to be reported. UV increases would also most adversely affect those whose occupations were outdoors, such as farm laborers, many of whom perished in the famines at this time in Europe.

No conclusive signal in the metrics discussed above can be determined, and the occurrence of some form of ozone depletion is left open to be conclusively proved or disproved, but we find that there is limited evidence to support high levels of halogens being injected into the stratosphere from these additional metrics.

Looking to the future, many models that contribute to the sixth phase of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project [CMIP6 (54)] will perform Past1000 experiments (55) employing the (56) EVA(eVolv2k) Stratospheric Aerosol Optical Depth (SAOD) reconstruction for volcanic forcing. This is a major step forward from CMIP5, where the option was to use either the Gao et al. (38) or Crowley et al. (57) reconstructions, and lack of clarity in model implementation makes a quantitative comparison between models challenging (39, 58). Regardless, a detailed description of the implementation of volcanic forcing is still required—Jungclaus et al. (55) compare the “volcanic forcing” of Gao et al. (38), Crowley et al. (57), and Toohey and Sigl (56) by comparing AOD at 500 nm, which is insufficient to quantify the radiative forcing. If models account for the impacts of aerosol size on the radiative forcing in different ways or neglect these important effects entirely, this may make quantitative comparisons of the CMIP6 Past1000 experiment more challenging.

Conclusions.

While previous work using physical climate models, such as those taking part in CMIP5 and the CESM-LME model simulations, overestimated the climate response to the 1257 eruption, compared to tree-ring proxy data studies with offline aerosol schemes have been shown to be more consistent with the tree-ring proxy data (8, 15). By including key interactive Earth system processes, such as interactive chemistry and aerosol microphysics, in the HadGEM3-ES Earth system model we can confirm that our current understanding of the physical and chemical processes resulting from the 1257 eruption of the Mt. Samalas are in good agreement with the available tree-ring proxy record. Using HadGEM3-ES and proxies for surface temperature we have been able to rule out large injections of the halogen inventory from Mt. Samalas (4) to the stratosphere but note that small injections could still have been possible. As little as a 1% yield of the erupted halogens reaching the stratosphere could lead to substantial ozone depletion altering the atmospheric radiative imbalance, increasing incident UV light at Earth’s surface, and altering the evolution of stratospheric sulfate aerosol by increasing the lifetime and stratospheric circulation. HadGEM3-ES supports the use of fully interactive chemistry and aerosol microphysics for future studies exploring the climatic impacts of large volcanic eruptions. CESM-LME, which employs a simple representation based on prescribing the effects of the eruption via noninteractive SAOD (38), overestimates the climate response compared to all tree-ring reconstructions. This study comprehensively assesses CESM-LME against tree-ring data for the 1257 Mt. Samalas eruption, despite its being widely used to study 13th-century climate change in the context of the Little Ice Age. This suggests caution should be urged when drawing conclusions about the results of CESM-LME simulations during this time period and that future last-millennium studies should include a more physically based representation of aerosol forcing (43, 59), such as we have demonstrated here with fully interactive chemistry and aerosol microphysics or such as Toohey and Sigl (56), and extensively document its implementation to facilitate a quantitative comparison of model responses to volcanic forcing over the last millennium.

Materials and Methods

Methods.

The annual resolution of tree rings makes them ideal for reconstructing the climatic changes associated with volcanic eruptions over the last millennium. While there are many factors which determine tree growth, it has been shown previously that the growth of trees at cool, moist sites at high elevation in the mid latitudes or northern boreal forests can be considered to be limited by temperature (60). Thus, we make use of tree-ring records from these locations in reconstructing surface temperature anomalies for comparison with our model data. There are several ways in which tree-ring records can be analyzed but the most common approaches are to use tree ring width (TRW) or MXD. MXD is a more robust method for assessing short-term climate variability due to memory effects in TRW data (61). However, for long-term variability, TRW reconstructions show superior performance in comparison to multiproxy data. The N-TREND dataset (36) was developed to “bridge” between these two differing methods and has been shown to perform well compared to multiproxy data (36) while overcoming many of the drawbacks to TRW data after volcanic eruptions. However, a consideration of confounding variables for MXD reconstructions has not been performed, despite light limitation (62) and acid deposition possibly being important in the aftermath of extremely large volcanic eruptions. In our model analysis we made use of data from three main sources: The MXD-based SCH15 dataset (https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/paleo-search/study/18875) (37) and the N-TREND merged tree-ring dataset (https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/paleo-search/study/19743) (36), which provided annual varying reconstructions of Northern Hemisphere average JJA temperature anomaly data, and the combined TRW-MXD SG17 dataset (https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/paleo-search/study/21090) (7), which is spatially resolved across the Northern Hemisphere. Model temperatures at 1.5 m above the surface were output at a monthly time resolution and compared with the proxy data in Fig. 1 by focusing on JJA monthly averages and focusing on land grid cells only, between and N. The anomalies in the tree-ring reconstructions were calculated relative to 1960 to 1990 whereas the anomalies in the model were calculated relative to a 30-y period of the preindustrial control run (63). See SI Appendix for further details.

The emissions data used in our study are based on the work of Vidal et al. (4). Recent analysis of glass shards retrieved in Antarctic ice cores suggest multiple volcanic sources for the 1259 sulfate spike (64), including the 1257 Mt. Samalas tephra, and two other eruptions, one local and one from New Zealand. This suggests that Mt. Samalas would not be the only source of the sulfur in Antarctic ice cores. However, high-resolution sulfur isotope analyses of Greenland and Antarctic ice (65) have confirmed the tropical and stratospheric origin of the sulfate for the 1259 spike, which corroborates that the 1257 Mt. Samalas eruption is most likely the only source of sulfate in ice cores. This is consistent with the amount of emitted by the eruption estimated by Vidal et al. (4) and Toohey and Sigl (56) and reinforces the choice of emission scenario for this study.

Simulations performed as part of the CMIP5 are analyzed. The Past1000 simulations were conducted in collaboration with the Paleoclimate Modeling Intercomparison Project Phase 3 (PMIP3) (66) and are transient simulations between 850 and 1850 based on time-evolving climate forcing (35). Six CMIP5 models performed both the historical and Past1000 simulations. CMIP5 data were obtained from the CEDA/BADC (Center for Environmental Data Analysis/British Atmospheric Data Center) archive on the JASMIN postprocessing system. An ensemble of 13 simulations of the last millennium was performed for the CESM-LME (34). The results were obtained from the Earth System Grid.

HadGEM3-ES is a coupled atmosphere–ocean GCM with interactive atmospheric chemistry and microphysical sulfate aerosol. The atmosphere component is the UK Met-Office Unified Model version 7.3 (67) in the HadGEM3-A r2.0 climate configuration (68). It employs a regular Cartesian grid of longitude by latitude (N48). In the vertical, 60 hybrid height vertical levels are employed—“hybrid” indicating that the model levels are sigma levels near the surface, changing smoothly to pressure levels near the top of the atmosphere (69). The model top is 84 km, which permits a detailed treatment of stratospheric dynamics and enables an internally generated QBO to be simulated. The ocean component of the model is the NEMO-OPA [Nucleus for European Modeling of the Ocean (70)] model version 3.0 (68). The sea ice component of the model is CICE (Los Alamos Community Ice CodE) version 4.0 (71). Atmospheric chemistry is represented by the UKCA (United Kingdom Chemistry & Aerosols) model, with updates from the model version described by (72). The model simulates the reactions and advection of 49 chemical tracers undergoing 187 chemical reactions. This represents a comprehensive treatment of stratospheric chemistry. In addition, the model contains a thorough treatment of chemical Ox, NOx and ClOx catalytic cycles. The stratospheric heterogeneous chemistry used includes recent updates documented by Dennison et al. (73). Sulfur chemistry is also simulated according to ref. 74, which includes the rate-limiting reaction. Aerosol processes for the emitted species anthropogenic sulfur, anthropogenic and biomass burning black carbon, biomass burning organic carbon, and natural emissions of mineral dust are treated by CLASSIC (Coupled Large-Scale Aerosol Simulator for Studies in Climate), a bulk aerosol scheme. Aerosol microphysics tuned for stratospheric sulfate aerosol processes is treated by GLOMAP-mode. GLOMAP-mode is a two-moment aerosol scheme which tracks both number and mass (75). This allows for a three-dimensional evolution of the size distribution, which is assumed to be modal with an evolving mean width but a fixed variance (mode width). The model treats in detail the condensation, nucleation, coagulation, cloud processing, hygroscopic growth, scavenging, and dry deposition of aerosols (75). As the primary interest is stratospheric sulfate aerosol, only soluble modes are simulated by GLOMAP-mode (nonanthropogenic sulfate aerosol and sea salt). The use of a fixed modal width of 1.4 for the accumulation soluble mode, combined with preventing mode merging between the accumulation and coarse modes, was found to improve the model fidelity compared to a more detailed sectional scheme (74). Interaction between aerosols and radiation is simulated by RADAER (76). The model simulates the key modes of climate variability and the magnitude of the climate response to the Mount Pinatubo eruption (SI Appendix, Figs. S5 and S6). The use of GLOMAP-mode for simulating the 1991 Mount Pinatubo eruption has been comprehensively validated (74), performing similarly to other aerosol-composition climate models.

The emissions of gases from the eruption of Mt. Samalas were injected into the model in a column between heights of 19 to 34 km above the surface. While the maximum plume height is estimated at 43 km (4), the height of the gas cloud is unknown. Previous model simulations of the eruption of Mt. Samalas have used injection heights based on the 1991 eruption of Mt Pinatubo (e.g., ref. 8). In our simulations we chose the top of the injection height to be 34 km [higher than that simulated for Mt. Pinatubo in Dhomse et al. (74)], as beyond this height aerosol properties in the model are poorly constrained.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge support from the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) and the National Center for Atmospheric Science for funding for UKCA and The North Atlantic Climate System: Integrated Studies. D.C.W. was supported by a NERC Doctoral Training Partnership studentship (grant DTP-1502139). L.M., N.L.A., and A.S. are funded by the NERC via “Vol-Clim” grant NE/S000887/1. S.D., G.M., and A.S. acknowledge funding via the NERC SMURPHS (“Securing Multidisciplinary UndeRstanding and Prediction of Hiatus and Surge periods”) project (NE/N006038/1). G.M. also acknowledges funding from the Copernicus Atmospheric Monitoring Service. Model integrations were performed using the ARCHER UK National Supercomputing Service and MONSooN system, a collaborative facility supplied under the Joint Weather and Climate Research Program, which is a strategic partnership between the UK Met Office and the NERC. D.C.W. acknowledges Eric Wolff and David Stevenson for their comments on the PhD thesis of which this paper largely forms a part, and we thank Prof. A. Robock and another anonymous reviewer for their constructive comments, which have greatly improved the paper.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1919807117/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability.

Model output data have been deposited on the Zenodo archive and can be accessed at DOI 10.5281/zenodo.4011660 (77). In our model analysis we made use of data from three main sources: The MXD-based SCH15 dataset (https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/paleo-search/study/18875) (37) and the N-TREND merged tree-ring dataset (https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/paleo-search/study/19743) (36), which provided annual varying reconstructions of Northern Hemisphere average JJA temperature anomaly data, and the combined TRW-MXD SG17 dataset (https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/paleo-search/study/21090) (7), which is spatially resolved across the Northern Hemisphere.

References

- 1.Lavigne F., et al. , Source of the great A.D. 1257 mystery eruption unveiled, Samalas volcano, Rinjani volcanic complex, Indonesia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 16742–16747 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sigl M., et al. , Insights from Antarctica on volcanic forcing during the common Era. Nat. Clim. Change 4, 693–697 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sigl M., et al. , Timing and climate forcing of volcanic eruptions for the past 2,500 years. Nature 523, 543–549 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vidal C. M., et al. , The 1257 Samalas eruption (Lombok, Indonesia): The single greatest stratospheric gas release of the common Era. Sci. Rep. 6, 34868 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Métrich N., et al. , New insights into magma differentiation and storage in holocene crustal reservoirs of the lesser sunda arc: The Rinjani–Samalas volcanic complex (Lombok, Indonesia). J. Petrol. 58, 2257–2284 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vidal C. M., et al. , Dynamics of the major plinian eruption of Samalas in 1257 A.D. (Lombok, Indonesia). Bull. Volcanol. 77, 73 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guillet S., et al. , Climate response to the Samalas volcanic eruption in 1257 revealed by proxy records. Nat. Geosci. 10, 123–128 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stoffel M., et al. , Estimates of volcanic-induced cooling in the Northern Hemisphere over the past 1,500 years. Nat. Geosci. 8, 784–788 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campbell B. M. S., Global climates, the 1257 mega-eruption of Samalas volcano, Indonesia, and the English food crisis of 1258. Trans. R. Hist. Soc. 27, 87–121 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bauch M., “The samalas eruption revisited” in The Dance of Death in Late Medieval and Renaissance Europe: Environmental Stress, Mortality and Social Response, Kiss A., Pribyl K., Eds. (Routledge, 2019), p. 175. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robock A., Cooling following large volcanic eruptions corrected for the effect of diffuse radiation on tree rings. Geophys. Res. Lett. 32, L06702 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zielinski G. A., Stratospheric loading and optical depth estimates of explosive volcanism over the last 2100 years derived from the Greenland Ice Sheet Project 2 ice core. J. Geophys. Res. 100, 20937 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mann M. E., Fuentes J. D., Rutherford S., Underestimation of volcanic cooling in tree-ring-based reconstructions of hemispheric temperatures. Nat. Geosci. 5, 202–205 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hartl-Meier C. T. M., et al. , Temperature covariance in tree ring reconstructions and model simulations over the past millennium. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 9458–9469 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Timmreck C., et al. , Limited temperature response to the very large AD 1258 volcanic eruption. Geophys. Res. Lett. 36, L21708 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pinto J. P., Turco R. P., Toon O. B., Self-limiting physical and chemical effects in volcanic eruption clouds. J. Geophys. Res. 94, 11165–11174 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bekki S., Oxidation of volcanic : A sink for stratospheric OH and . Geophys. Res. Lett. 22, 913–916 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robock A., Volcanic eruptions and climate. Rev. Geophys. 38, 191–219 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kremser S., et al. , Stratospheric aerosol-observations, processes, and impact on climate. Rev. Geophys. 54, 278–335 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Timmreck C., et al. , Aerosol size confines climate response to volcanic super-eruptions. Geophys. Res. Lett., 37, L24705 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robock A., et al. , Did the Toba volcanic eruption of ?74 ka B.P. produce widespread glaciation? J. Geophys. Res. 114, D10107 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stolarski R. S., Cicerone R. J., Stratospheric chlorine: A possible sink for ozone. Can. J. Chem. 52, 1610–1615 (1974). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Farman J. C., Gardiner B. G., Shanklin J. D., Large losses of total ozone in Antarctica reveal seasonal ClOx/NOx interaction. Nature 315, 207–210 (1985). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tie X. X., Brasseur G., The response of stratospheric ozone to volcanic eruptions: Sensitivity to atmospheric chlorine loading. Geophys. Res. Lett. 22, 3035–3038 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kutterolf S., et al. , Combined bromine and chlorine release from large explosive volcanic eruptions: A threat to stratospheric ozone? Geology 41, 707–710 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cadoux A., Bruno S., Bekki S., Oppenheimer C., Druitt T. H., Stratospheric ozone destruction by the bronze-age minoan eruption (Santorini volcano, Greece). Sci. Rep. 5, 12243 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cadoux A., et al. , A new set of standards for in-situ measurement of bromine abundances in natural silicate glasses: Application to SR-XRF, LA-ICP-MS and SIMS techniques. Chem. Geol. 452, 60–70 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ming A., et al. , Stratospheric ozone changes from explosive tropical volcanoes: Modelling and ice core constraints. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 125, e2019JD032290 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brenna H., Kutterolf S., Krüger K., Global ozone depletion and increase of UV radiation caused by pre-industrial tropical volcanic eruptions. Sci. Rep. 9, 9435 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brenna H., Kutterolf S., Mills M. J., Krüger K., The potential impacts of a sulfur- and halogen-rich supereruption such as Los Chocoyos on the atmosphere and climate. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 20, 6521–6539 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Klobas J. E., Wilmouth D. M., Weisenstein D. K., Anderson J. G., Salawitch R. J., Ozone depletion following future volcanic eruptions. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 7490–7499 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mather T. A., Volcanoes and the environment: Lessons for understanding Earth’s past and future from studies of present-day volcanic emissions. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 304, 160–179 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Textor C., Graf H.-F., Herzog M., Oberhuber J. M., Injection of gases into the stratosphere by explosive volcanic eruptions. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 108, 4606 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Otto-Bliesner B. L., et al. , Climate variability and change since 850 CE: An ensemble approach with the community earth system model. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 97, 735–754 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schmidt G. A., et al. , Climate forcing reconstructions for use in PMIP simulations of the Last Millennium (v1.1). Geosci. Model Dev. 5, 185–191 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wilson R., et al. , Last millennium northern hemisphere summer temperatures from tree rings: Part I: The long term context. Quat. Sci. Rev. 134, 1–18 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schneider L., et al. , Revising midlatitude summer temperatures back to A.D. 600 based on a wood density network. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 4556–4562 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gao C., Robock A., Ammann C., Volcanic forcing of climate over the past 1500 years: An improved ice core-based index for climate models. J. Geophys. Res. 113, D23111 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schneider L., Smerdon J. E., Pretis F., Hartl-Meier C., Esper J., A new archive of large volcanic events over the past millennium derived from reconstructed summer temperatures. Environ. Res. Lett. 12, 094005 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wilka C., et al. , On the role of heterogeneous chemistry in ozone depletion and recovery. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 7835–7842 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Muthers S., Arfeuille F., Raible C. C., Rozanov E., The impacts of volcanic aerosol on stratospheric ozone and the Northern Hemisphere polar vortex: Separating radiative-dynamical changes from direct effects due to enhanced aerosol heterogeneous chemistry. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 15, 11461–11476 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lurton T., et al. , Model simulations of the chemical and aerosol microphysical evolution of the Sarychev Peak 2009 eruption cloud compared to in situ and satellite observations. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 18, 3223–3247 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schmidt A., et al. , Volcanic radiative forcing from 1979 to 2015. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 123, 12491–12508 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Norval M., Halliday G. M., The consequences of UV-induced immunosuppression for human health. Photochem. Photobiol. 87, 965–977 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Norval M., et al. , The effects on human health from stratospheric ozone depletion and its interactions with climate change. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 6, 232–251 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Diffey B., Climate change, ozone depletion and the impact on ultraviolet exposure of human skin. Phys. Med. Biol. 49, R1–R11 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Black B. A., Lamarque J.-F., Shields C. A., Elkins-Tanton L. T., Kiehl J. T., Acid rain and ozone depletion from pulsed Siberian traps magmatism. Geology 42, 67–70 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Madronich S., Analytic formula for the clear-sky UV index. Photochem. Photobiol. 83, 1537–1538 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pinke Z., Stephen P., Kern Z., Volcanic mega-eruptions may trigger major cholera outbreaks. Clim. Res. 79, 151–162 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bekki S., Law K. S., Pyle J. A., Effect of ozone depletion on atmospheric and CO concentrations. Nature, 371, 595–597 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gauci V., et al. , Sulfur pollution suppression of the wetland methane source in the 20th and 21st centuries. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 12583–12587 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McConnell J. R., “Tunu, Greenland 2013 ice core chemistry” (NSF Arctic Data Center, 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lancaster H. O., Expectations of Life: A Study in the Demography, Statistics, and History of World Mortality (Springer-Verlag, 1990). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Eyring V., et al. , Overview of the coupled model Intercomparison project phase 6 (CMIP6) experimental design and organization. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 1937–1958 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jungclaus J. H., et al. , The PMIP4 contribution to CMIP6 – Part 3: The last millennium, scientific objective, and experimental design for the PMIP4 past1000 simulations. Geosci. Model Dev. 10, 4005–4033 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 56.Toohey M., Sigl M., Volcanic stratospheric sulfur injections and aerosol optical depth from 500 BCE to 1900 CE. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 9, 809–831 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 57.Crowley T. J., et al. , Volcanism and the Little Ice Age. PAGES News. 16, 22–23 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 58.Atwood A. R., Wu E., Frierson D. M. W., Battisti D. S., Sachs J. P., Quantifying climate forcings and feedbacks over the last millennium in the CMIP5–PMIP3 models. J. Clim. 29, 1161–1178 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mills B. J. W., Belcher C. M., Lenton T. M., Newton R. J., A modeling case for high atmospheric oxygen concentrations during the Mesozoic and Cenozoic. Geology 44, 1023–1026 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 60.Briffa K. R., et al. , Reduced sensitivity of recent tree-growth to temperature at high northern latitudes. Nature 391, 678–682 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 61.Esper J., Schneider L., Smerdon J. E., Schöne B. R., Büntgen U., Signals and memory in tree-ring width and density data. Dendrochronologia 35, 62–70 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tingley M. P., Stine A. R., Huybers P., Temperature reconstructions from tree-ring densities overestimate volcanic cooling. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 7838–7845 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nowack P. J., et al. , A large ozone-circulation feedback and its implications for global warming assessments. Nat. Clim. Change 5, 41–45 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Narcisi B., Robert Petit J., Delmonte B., Batanova V., Savarino J., Multiple sources for tephra from AD 1259 volcanic signal in Antarctic ice cores. Quat. Sci. Rev. 210, 164–174 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 65.Burke A., et al. , Stratospheric eruptions from tropical and extra-tropical volcanoes constrained using high-resolution sulfur isotopes in ice cores. Earth Planet Sci. Lett. 521, 113–119 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 66.Braconnot P., et al. , Evaluation of climate models using palaeoclimatic data. Nat. Clim. Change 2, 417–424 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 67.Davies T., et al. , A new dynamical core for the Met Office’s global and regional modelling of the atmosphere. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 131, 1759–1782 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hewitt H. T., et al. , Design and implementation of the infrastructure of HadGEM3: The next-generation met office climate modelling system. Geosci. Model Dev. 4, 223–253 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 69.Simmons A. J., Strüfing R., Numerical forecasts of stratospheric warming events using a model with a hybrid vertical coordinate. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 109, 81–111 (1983). [Google Scholar]

- 70.Madec G., “NEMO ocean engine” (Note du Pôle de modélisation, Institut Pierre-Simon Laplace; No. 27, 2008). [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hunke E. C., Lipscomb W. H., “The Los Alamos sea ice model documentation and software user’s manual” (Version 4.0, LA-CC-06-012. Technical report, Los Alamos National Laboratory, 2008).

- 72.Morgenstern O., et al. , Evaluation of the new UKCA climate-composition model – Part I: The stratosphere. Geosci. Model Dev. 1, 381–432 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dennison F., et al. , Improvements to stratospheric chemistry scheme in the um-ukca (v10.7) model: Solar cycle and heterogeneous reactions. Geosci. Model Dev. 12, 1227–1239 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dhomse S. S., et al. , Aerosol microphysics simulations of the Mt. Pinatubo eruption with the UM-UKCA composition-climate model. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 14, 11221–11246 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mann G. W., et al. , Description and evaluation of GLOMAP-mode: A modal global aerosol microphysics model for the UKCA composition-climate model. Geosci. Model Dev. 3, 651–734 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bellouin N., “Interaction of UKCA aerosols with radiation: UKCA RADAER” (Met Office Hadley Centre, 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wade D., et al. , Ozone column data from Wade et al (Version 1) [Data set]. Zenodo. 10.5281/zenodo.4011660. Deposited 2 September 2020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Model output data have been deposited on the Zenodo archive and can be accessed at DOI 10.5281/zenodo.4011660 (77). In our model analysis we made use of data from three main sources: The MXD-based SCH15 dataset (https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/paleo-search/study/18875) (37) and the N-TREND merged tree-ring dataset (https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/paleo-search/study/19743) (36), which provided annual varying reconstructions of Northern Hemisphere average JJA temperature anomaly data, and the combined TRW-MXD SG17 dataset (https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/paleo-search/study/21090) (7), which is spatially resolved across the Northern Hemisphere.