Abstract

Since the spread of multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae (MDRKP) strains is considered as a challenge for patients with weakened or suppressed immunity, the emergence of isolates carrying determinants of hypervirulent phenotypes in addition may become a serious problem even for healthy individuals. The aim of this study is an investigation of the nonoutbreak K. pneumoniae emergence occurred in early 2017 at a maternity hospital of Kazan, Russia. Ten bacterial isolates demonstrating multiple drug resistance phenotypes were collected from eight healthy full-term breastfed neonates, observed at the maternity hospital of Kazan, Russia. All the infants and their mothers were dismissed without symptoms or complaints, in a satisfactory condition. Whole-genome shotgun (WGS) sequencing was performed with the purpose to track down a possible spread source(s) and obtain detailed information about resistance determinants and pathogenic potential of the collected isolates. Microdilution tests have confirmed production of extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBL) and their resistance to aminoglycoside, β-lactam, fluoroquinolone, sulfonamide, nitrofurantoin, trimethoprim, and fosfomycin antibiotics and Klebsiella phage. The WGS analysis has revealed the genes that are resistant to aminoglycosides, fluoroquinolones, macrolides, sulfonamides, chloramphenicols, tetracyclines, and trimethoprim and ESBL determinants. The pangenome analysis had split the isolates into two phylogenetic clades. The first group, a more heterogeneous clade, was represented by 5 isolates with 4 different in silico multilocus sequence types (MLSTs). The second group contained 5 isolates from infants born vaginally with the single MLST ST23, positive for genes corresponding to hypervirulent phenotypes: yersiniabactin, aerobactin, salmochelin, colibactin, hypermucoid determinants, and specific alleles of K- and O-antigens. The source of the MDRKP spread was not defined. Infected infants have shown no developed disease symptoms.

1. Introduction

Newborn babies could obtain microorganisms from clinical environment, personnel, other patients, and parents, e.g., via breast milk. Since Enterobacteriaceae are known as early human gastrointestinal tract colonizers, local and systemic diseases could take place during the dynamic microbiome development. Their stabilization and persistence may have destructive consequences on the host's vital functions. Moreover, due to high horizontal gene transport frequency between the microbiome members, persistence of even a single strain carrying pathobiotic genes after its spread may cause explicit cytotoxic and genotoxic effects on host cells, leading to dangerous repercussion including colorectal cancer in particular [1]. Underweight and weakened patients of neonatal intensive care nurseries often suffer from Gram-positive bacterial infections, mostly caused by coagulase-negative Staphylococci, while the infections caused by Gram-negative bacteria are considered as more rare and deadly even after more rapid generalization [2].

Klebsiella pneumoniae is a causative agent of numerous nosocomial and community acquired infections including pneumonia, sepsis, bacteremia, meningitis, pyogenic liver abscesses, urinary tract infections, and more. The risk group historically includes patients with a weakened and malfunctioning immune system, but the spread of hypervirulent strains also endangers immunosufficient individuals [3]. First isolated from the lungs of patients with pneumonia postmortem, K. pneumoniae were acknowledged as a part of the normal human gastrointestinal tract microbiome since then. The colonization can spread, persist for years, and cause different pathologies from hidden carriage to fatal acute infections even for healthy individuals [4].

In this study, we applied whole-genome shotgun (WGS) sequencing to describe in detail 8 cases of asymptomatic carriage of multidrug-resistant K. pneumoniae (MDRKP) in the gastrointestinal tract of full-term infants, detected at similar time periods after the birth without visible symptoms in their health.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Approval

The infant stool samples collection was performed as a routine task during normal observation at the maternity hospital. The standard biosecurity and institutional safety procedures have been adhered to handle human subjects. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants' parents included in the study. No special ethical restrictions were raised.

2.2. Isolation of MDRKP from the Infants' Stool Samples

2.2.1. Patients

A total of 10 K. pneumoniae isolates demonstrating a multidrug resistance phenotype were collected from 10 stool samples (8 nonrepetitive) from 8 newborn full-term breastfed infants during hospitalization in a maternity hospital of Kazan, Russia. 5 neonates were born with vaginal delivery, 3 after cesarean surgery. No infection outbreak was recorded, and no detailed microbiological analysis was performed on parents. The infant stool samples were collected at 3–4 days of life and were contaminated with 108–109 of MDRKP colony-forming units per gram of stool. The meconium samples obtained from all 8 individuals were not tested for contamination. Yet, the meconium samples obtained from 40 infants in the previous research studies were conditionally sterile or contained bifidobacteria [5]. Two samples collected from two infants after 1 and 3 months of monitoring also contained MDRKP (Table 1). All 8 neonates were discharged from hospital at 4-5 days of life in a satisfactory condition. Blood in stool and liquid stool were reported only once for the patient #1 on the third month of life, and constipation was reported for the patient #2 on the first month of life. No other manifested and prolonged symptoms were reported across the whole monitoring time from the individuals.

Table 1.

Patient data, sample data, and demonstrated drug resistance of the studied K. pneumoniae isolates.

| Sample name | Kleb102 | Kleb22 | Kleb24 | Kleb27 | Kleb28 | Kleb29 | Kleb60 | Kleb85 | Kleb90 | Kleb91 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample number | 102 | 22 | 24 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 60 | 85 | 90 | 91 |

| Delivery | C | V | V | V | V | V | C | C | V | C |

| Patient ID | 2 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 1 | 2 |

| Patient age, days | 33 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 90 | 3 |

| K. pneumoniae, log10(CFU/g) | 7 | 9 | 8 | 8 | 9 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 8 |

| ESBL | - | + | - | - | + | + | + | + | - | + |

| Klebsiella phage | R | S | R | R | N | R | S | S | R | R |

| Pyo phage | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S |

| Amikacin | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S |

| Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid | R | R | S | S | R | R | R | R | S | R |

| Ampicillin | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R |

| Aztreonam | R | R | S | S | R | R | R | R | N | R |

| Ceftriaxone | R | R | S | S | R | R | R | R | S | R |

| Chloramphenicol | N | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S |

| Ciprofloxacin | S | I | S | S | R | I | S | S | S | S |

| Fosfomycin | R | R | I | R | R | R | R | R | N | R |

| Gentamicin | S | S | S | N | R | R | S | S | N | S |

| Imipenem | R | S | S | I | R | I | R | R | N | R |

| Meropenem | R | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | N | S |

| Netilmicin | S | R | S | S | R | R | S | S | N | I |

| Nitrofurantoin | R | I | S | R | R | I | R | R | R | R |

| Sulfamethoxazole | S | R | S | S | R | R | R | R | N | R |

| Trimethoprim | S | R | S | S | R | R | R | R | N | R |

CFU, colony-forming unit. Delivery: V, vaginal; C, cesarean section. Susceptibility to an antimicrobial agent: S, susceptible, R, resistant; I, intermediate; N, not defined.

2.3. Phenotype Characterization

The antimicrobial susceptibilities of the 10 microbial isolates were determined using a broth microdilution procedure. The following antibacterial agents were tested: aminoglycosides (amikacin, netilmicin, gentamicin), β-lactam (amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, ampicillin, aztreonam, ceftriaxone, imipenem, meropenem), nitrofuran derivatives (nitrofurantoin), sulfonamides (sulfamethoxazole), 2, 4-diaminopyrimidines (trimethoprim), fluoroquinolones (ciprofloxacin), chloramphenicol, and fosfomycin. The production of extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBL) and susceptibility to Klebsiella phage and pyo bacteriophage were also analyzed during the routine. The results were interpreted in automated mode using a VITEK 2 Compact analyzer (bioMérieux SA, France) according to the producer's guidance documents.

2.4. Whole-Genome Sequencing and Assembly

Libraries were prepared using the NEBNext Ultra II DNA Library Preparation Kit. Whole-genome DNA was sequenced using the Illumina MiSeq platform (Illumina Inc., USA), with a paired-end run of 2 by 250 bp. Raw reads quality control was performed using FastQC v0.11 [6]; then, reads were trimmed using Trimmomatic v0.39 [7] and Cutadapt v2.4 [8], assembled using SPAdes v3.9.1 [9]. Assembly statistics were calculated using the reference K. pneumoniae genome with RefSeq ID NC_016845.1.

2.5. Further Genome Assembly Processing

The per-sample chromosome and plasmid assemblies were merged, filtered, and deduplicated using in-house scripts. The resulting assemblies were submitted to NCBI. The assemblies were annotated locally using Prokka v1.13.7 [10] and remotely with the NCBI Prokaryotic Genome Annotation Pipeline (PGAP) [11]. The in silico multilocus sequence type (MLST) results were computed using SRST2 v0.2 [12] and Kleborate [13]. The virulence-associated genes encoding yersiniabactin, aerobactin, salmochelin, colibactin, regulators of mucoid phenotypes, serotypes, and drug resistance determinants were combined using Kleborate with Kaptive subroutine [14]. Pangenome analysis was performed across the sequence query containing also 365 K. pneumoniae completed genome assemblies downloaded from the NCBI FTP server. A phylogeny was drawn using Roary, Pan Genome Pipeline v3.12.0 [15].

3. Results and Discussion

Neonatal infection is a clinical syndrome, characterized by systemic symptoms of the first month of life. However, in this study, we observed the case of newborn infant gastrointestinal tract colonization by the known pathogen K. pneumoniae, demonstrating a multidrug resistance phenotype without manifested symptoms.

The microdilution method has confirmed isolates with resistance to aminoglycosides, β-lactam, nitrofuran, fluoroquinolones, sulfonamides, trimethoprim, and fosfomycin antibiotics and Klebsiella phage. All the isolates were susceptible to amikacin, chloramphenicol, and pyo bacteriophage (Table 1).

The discovered WGS de novo resistome profile has included genetic determinants of drug resistance to aminoglycosides, fluoroquinolones, macrolides, sulfonamides, chloramphenicols, tetracyclines, and trimethoprim. It also confirmed the common β-lactamase (BLA) gene spread across all the isolates as well as the occurrence of isolates carrying certain genes of broad-spectrum β-lactamases (BSBL), BSBL with resistance to β-lactamase inhibitors (BSBL-inhR), and ESBL (Table 2). The results of the screening for genetic determinants of resistance to colistin, fosfomycin, glycopeptide, nitroimidazole, rifampicin, and a possible production of carbapenemases or ESBL with resistance to BLA inhibitors were negative.

Table 2.

Genome assembly data, MLSTs, and drug resistance determinants of the studied K. pneumonia isolates.

| Sample name | Kleb102 | Kleb22 | Kleb27 | Kleb24 | Kleb28 | Kleb29 | Kleb60 | Kleb85 | Kleb90 | Kleb91 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GenBank Accession ID | VOOJ00000000 | VOOA00000000 | VOOD00000000 | VOOC00000000 | VOOE00000000 | VOOF00000000 | VOOG00000000 | VOOH00000000 | VOOB00000000 | VOOI00000000 |

| SRA accession ID | SRR12102917 | SRR12102926 | SRR12102923 | SRR12102924 | SRR12102922 | SRR12102921 | SRR12102920 | SRR12102919 | SRR12102925 | SRR12102918 |

| Reads number | 1040088 | 805318 | 1056762 | 856300 | 926382 | 1259976 | 994296 | 1207354 | 1216382 | 1381726 |

| Coverage | 58.7x | 45.4x | 59.6x | 48.3x | 52.3x | 71.1x | 56.1x | 68.1x | 68.6x | 78.0x |

| Genome assembly length | 5297684 | 5881113 | 5641111 | 5518356 | 5885411 | 5890967 | 5666743 | 5324705 | 5882697 | 5326604 |

| Contig number | 106 | 111 | 76 | 94 | 120 | 118 | 91 | 74 | 108 | 77 |

| N50 metric | 350001 | 307112 | 322041 | 319410 | 307112 | 307112 | 263911 | 358425 | 307112 | 437151 |

| Largest contig length | 1106296 | 770102 | 1334922 | 930837 | 771547 | 799268 | 642551 | 812552 | 799226 | 812552 |

| MLST | ST983-1LV | ST23 | ST23 | ST37 | ST23 | ST23 | ST268 | ST45 | ST23 | ST45 |

| Yersiniabactin | ybt unknown | ybt 1; ICEKp10 | ybt 1; ICEKp10 | — | ybt 1; ICEKp10 | ybt 1; ICEKp10 | ybt 17; ICEKp10 | — | ybt 1; ICEKp10 | — |

| Colibactin | — | clb 2 | clb 2 | — | clb 2 | clb 2 | clb 3 | — | clb 2 | — |

| Aerobactin | — | iuc 1 | iuc 1 | — | iuc 1 | iuc 1 | iuc 1 | — | iuc 1 | — |

| Salmochelin | — | iro 1 | iro 1 | — | iro 1 | iro 1 | iro 1 | — | iro 1 | — |

| rmpA | — | rmpA_2 (KpVP-1), rmpA_2 (KpVP-1) | rmpA_2 (KpVP-1) | — | rmpA_2 (KpVP-1) | rmpA_2 (KpVP-1) | rmpA_2∗(KpVP-1), rmpA_2∗(KpVP-1) | — | rmpA_2 (KpVP-1) | — |

| rmpA2 | — | rmpA2_8, rmpA2_8 | rmpA2_5, rmpA2_5 | — | rmpA2_8, rmpA2_8 | rmpA2_8, rmpA2_8 | rmpA2_2∗, rmpA2_2∗ | — | rmpA2_8, rmpA2_8 | — |

| Wzi | wzi39 | wzi1 | wzi1 | wzi123 | wzi1 | wzi1 | wzi95 | wzi101 | wzi1 | wzi101 |

| K Locus | KL39 | KL1 | KL1 | KL136 | KL1 | KL1 | KL20 | KL24 | KL1 | KL24 |

| O Locus | O3b | O1v2 | O1v2 | O2v2 | O1v2 | O1v2 | O2v1 | O2v1 | O1v2 | O2v1 |

| Aminoglycosides | StrB; StrA∗ | StrB; StrA∗; Aac3-IIa∗; StrB; StrA∗ | — | StrB; StrA | StrB; StrA∗; Aac3-IIa∗ | StrB; StrA∗; Aac3-IIa∗ | StrB; StrA∗; Aph3-Ia∗ | StrB; StrA∗ | StrB; StrA∗; Aac3-IIa∗; StrB; StrA∗ | StrB; StrA∗ |

| Fluoroquinolones | — | QnrB1? | — | — | QnrB1? | QnrB1? | — | — | QnrB1? | — |

| Macrolides | — | — | — | — | — | — | EreA2 | — | — | — |

| Phenicols | CatA1∗ | CatB4 | — | — | CatB4 | CatB4 | — | CatB4 | CatB4 | CatB4 |

| Sulfonamides | SulII∗ | SulII; SulII | — | — | SulII | SulII | SulI; SulII∗ | SulII | SulII; SulII | SulII |

| Tetracyclines | TetA | TetA | — | — | TetA | TetA | — | — | TetA | — |

| Trimethoprim | — | DfrA14; DfrA14 | — | — | DfrA14 | DfrA14 | DfrA5 | DfrA14 | DfrA14 | DfrA14 |

| BLA | SHV-187∗; AmpH∗ | SHV-190∗; AmpH; OXA-1 | SHV-190∗; AmpH | AmpH∗ | SHV-190∗; AmpH; OXA-1 | SHV-190∗; AmpH; OXA-1 | AmpH∗ | AmpH∗; OXA-1 | SHV-190∗; AmpH; OXA-1 | AmpH∗; OXA-1 |

| ESBL | — | CTX-M-15; CTX-M-15 | — | — | CTX-M-15 | CTX-M-15 | SHV-13∗; CTX-M-3; CTX-M-3 | CTX-M-15 | CTX-M-15; CTX-M-15 | CTX-M-15 |

| BSBL | — | — | — | SHV-77∗ | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| BSBL-inhR | TEM-30∗ | TEM-30∗; TEM-30∗ | — | — | TEM-30∗ | TEM-30∗ | — | SHV-26∗; TEM-30∗ | TEM-30∗; TEM-30∗ | SHV-26∗; TEM-30∗ |

MLST, in silico multilocus sequence type; BLA, β-lactamases; BSBL, broad-spectrum β-lactamases, BSBL-inhR, BSBL with resistance to β-lactamase inhibitors, ESBL, extended-spectrum β-lactamases. Asterisked proteins are ones without exact nucleotide and amino acid match.

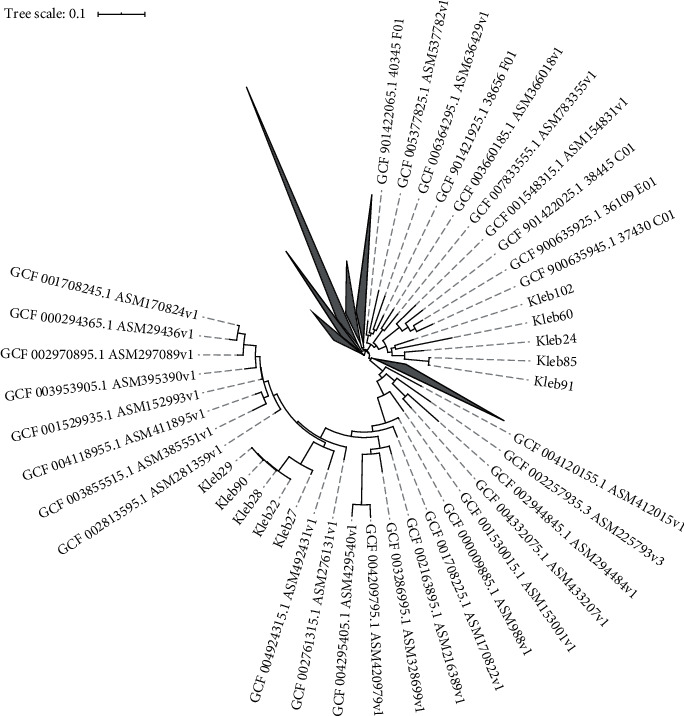

Biotype profiling has revealed that 10 isolates were related to 31 reference strains and combined into two clusters (Figure 1). The first cluster has included samples ##60, 85, 91, 102, and 24. All the isolates except the last one were obtained from cesarean delivery infants. The MLST analysis results have included the STs 37, 45, 268, and 9831LV (Table 2). The ST37 strains were reported as possible reservoirs for carbapenem resistance genes during antimicrobial therapy in neonates [16]; ST45, as the ESBL carrying infectious agents of highly contagious neonatal sepsis [17]; ST268, as possible reservoirs for New Delhi metallo-BLA (NDM) [18]; and ST983, as typical causative agents of nosocomial infections also harboring ESBL [19].

Figure 1.

Phylogeny tree showing the relationship between 10 studying K. pneumoniae isolates and reference strains; built using Roary, the pangenome software; visualized using iTOL.

Due to the genetic divergence within the group, the patients most likely were infected from different sources. Because of the lack of the microbiological data from detailed examination performed on their mothers, we also cannot exclude the vertical transmission case after the silent colonization of the maternal urinary tract by MDRKP. It is known that asymptomatic bacteriuria occurs in 2–7 % of pregnant women in the United States and may cause severe urinary tract infection even leading to nephrectomy [20]. Gravidas are experiencing a 20-fold increased risk of pyelonephritis mainly caused by pregnancy immunosuppression, mechanical bladder compression, and ureteral dilatation [21]. The vertical transmission of pathogenic microorganisms is possible during the birth and before. The described cases of uterine K. pneumoniae infection during pregnancy include penetration via the fetal membranes and hematoplacental barrier, resulting to chorioamnionitis [22] and acute placental infection [23]. The infection source for the first group of studying infants remains unclear, due to the fact that their mothers were reported as healthy, with no symptoms or complains.

The other five isolates, ##22, 90, 27, 28, and 29, obtained from the infants born vaginally have formed even a less-divergent clade (Figure 1), allowing us to make a conclusion about a single MDRKP infection source. All 5 isolates were also positive for the genes of siderophore yersiniabactin (ybt), aerobactin (iuc) and salmochelin (iro), genotoxin colibactin (clb), hypermucoid determinants (rmpA, rmpA2), and specific wzi loci alleles related to the K- (capsule) and O- (LPS) antigen development, which cumulative presence corresponds to extremely virulent phenotypes in theory. More important, their MLST was only ST23. First reported in the mid-1980s in Taiwan, ST23 was often mentioned to present and strongly associated with the K1 capsular serotype [24]. The K. pneumoniae ST23 strains were confirmed as multidrug-resistant hypervirulent pathogens causing abscesses of the kidneys, pancreas, liver [25], and endogenous endophthalmitis [26], with dominance in the Asian Pacific region [27]. In fact, it means the 4 cases of asymptomatic colonization of the infant intestinal tract by hypervirulent strains of MDRKP that spread a short time ago and may be accounted as a hospital-acquired infection. The persistence of the MDRKP ST23 strain has been also confirmed for the patient #1 (sample #90) at the third month of life (Table 1)—still without acute immune response.

The fetal immune system is not developed compared with later life mostly due to the environmental limitation—the stress of the own remodeling tissues and noninherited maternal alloantigens should not provoke the immune reaction from the fetus side [28]. Their innate immune system is muted [29], the humoral immune responses are blunted, the immunoglobulin class switching is incomplete, and the released IgG antibodies decline rapidly after immunization [30]. However, the immature Th1-type T-cell response is compensated by the IFN-γ producing γδ-T cells [31]. By the way, the main mechanism of neonatal immune protection is based on vertical transport of antibodies via breastfeeding. With some fortune, breastfed newborns will not suffer infections that have induced the immune response from their mothers earlier. Otherwise, a lack of specific antibodies will result in infection development [32].

4. Conclusion

The emergence and spread of hypervirulent K. pneumoniae-carrying multidrug resistance genes in a hospital setting have constant dangerous context. We have demonstrated a phenomenon of silent carriage of two K. pneumoniae strain groups within the gut microbiome of healthy full-term neonates—more-divergent “normal” groups with multiple possible transmission paths and less-divergent hypervirulent strains with a single possible source. An undeveloped infant infection may indicate the successful production of the required antibodies by a maternal organism. It is possible after immunization of maternal organism occurred definitely before the childbirth—in maternity hospital settings or even before the hospitalization. Retrospectively, no infection source has been declared by hospital personnel after a time.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the subsidy allocated to Kazan Federal University for the state assignment in the sphere of scientific activities (project no. 0671-2020-0058).

Data Availability

The corresponding WGS project has been deposited at the NCBI GenBank database under the main BioProject accession ID PRJNA556398. The project data analysis scripts and materials are hosted on GitHub (https://github.com/ivasilyev/curated_projects/tree/master/inicolaeva/klebsiella_infants).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Pope J. L. Microbial colonization coordinates the pathogenesis of a Klebsiella pneumoniae infant isolate. Scientific Reports. 2019;9(1):p. 3380. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-39887-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dorota P., Chmielarczyk A., Katarzyna L., et al. Mach, “Klebsiella pneumoniae in breast milk-A cause of sepsis in neonate”. Archives of Medicine. 2017;9(1):1–4. doi: 10.21767/1989-5216.1000189. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shankar C. Whole genome analysis of hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates from community and hospital acquired bloodstream infection. BMC Microbiology. 2018;18(1):p. 6. doi: 10.1186/s12866-017-1148-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rebekah M. Martin and michael A. Bachman. “Colonization, infection, and the accessory genome of Klebsiella pneumoniae”. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology. 2018;8:1–15. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2018.00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nikolaeva I. V. Metabolic activity of intestinal microflora in newborns with a different mode of delivery. Rossiyskiy Vestnik Perinatologii i Pediatrii (Russian Bulletin of Perinatology and Pediatrics) 2019;64(2):81–86. doi: 10.21508/10274065-2019-64-2-81-86. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steven W. Wingett and Simon Andrews. “FastQ Screen: a tool for multi-genome mapping and quality control”. F1000Research. 2018;7:p. 1338. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.HYPERLINK. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bolger A. M., Lohse M., Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(15):2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martin M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from highthroughput sequencing reads. EMBnet.journal. 2011;17(1):p. 10. doi: 10.14806/ej.17.1.200. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bankevich A., Nurk S., Antipov D., et al. SPAdes: a New genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. Journal of Computational Biology. 2012;19(5):455–477. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Torsten S. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics. 2014;30.14:2068–2069. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haft D. H., DiCuccio M., Badretdin A., et al. RefSeq: an update on prokaryotic genome annotation and curation. Nucleic Acids Research. 2018;46:D851–D860. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inouye M., Dashnow H., Raven L., et al. Rapid genomic surveillance for public health and hospital microbiology labs. Genome Medicine. 2014;6(11):p. 90. doi: 10.1186/s13073-0140090-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pichler C. First report of invasive liver abscess syndrome with endophthalmitis caused by a K2 serotype ST2398 hyperviru- lent Klebsiella pneumoniae in Germany, 2016. New Microbes and New Infections. 2017;17:77–80. doi: 10.1016/j.nmni.2017.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ryan R. W. Kaptive Web: user-Friendly Capsule and Lipopolysaccharide Serotype Prediction for Klebsiella Genomes. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2018;56(6) doi: 10.1128/JCM.00197-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Page A. J. Roary: Rapid large-scale prokaryote pan genome analysis. Bioinformatics. 2015;31(22):3691–3693. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li P. ST37 Klebsiella pneumoniae: development of carbapenem resistance in vivo during antimicrobial therapy in neonates. Future Microbiology. 2017;12(10):891–904. doi: 10.2217/fmb-2016-0165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marando R. Predictors of the extended-spectrum-beta lactamases producing Enterobacteriaceae neonatal sepsis at a tertiary hospital, Tanzania. International Journal of Medical Microbiology. 2018;308(7):803–811. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2018.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kiaei S., Moradi M., Hosseini-Nave H., Ziasistani M., Kalantar-Neyestanaki D. Endemic dissemination of different sequence types of carbapenem-resistant klebsiella pneumoniae strains harboring bla NDM and 16S rRNA methylase genes in kerman hospitals, Iran, from 2015 to 2017. Infection and Drug Resistance. 2019;12:45–54. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S186994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Founou R. C., Founou L. L., Allam M., Ismail A., Essack S. Y. Whole genome sequencing of extended spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated from hospitalized patients in KwaZulu-natal, South Africa. Scientific Reports. 2019;9(1):1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-42672-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim S. J., Parikh P., King A. N., Marnach M. L. Asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnancy complicated by pyelonephritis requiring nephrectomy. Case Reports in Obstetrics and Gynecology 2018. 2018;4:1–4. doi: 10.1155/2018/8924823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Farkash E., Weintraub A. Y., Sergienko R., Wiznitzer A., Zlotnik A., Sheiner E. Acute antepartum pyelonephritis in pregnancy: a critical analysis of risk factors and outcomes. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 2012;162(1):24–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2012.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oh K. J. Twenty-four percent of patients with clinical chorioamnionitis in preterm gestations have no evidence of either culture-proven intraamniotic infection or intraamniotic inflammation. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2017;216(6):604.e1–604.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.02.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sheikh S. S., Samir S. A., Lage J. M. Acute placental infection due to Klebsiella pneumoniae: report of a unique case. Infectious Disease in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2005;13(1):49–52. doi: 10.1080/10647440400028177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shon A. S., Bajwa R. P. S., Russo T. A. Hypervirulent (hypermucoviscous) Klebsiella pneumoniae. Virulence 4. 2013;2:107–118. doi: 10.4161/viru.22718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shen D. Emergence of a multidrug-resistant hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae sequence type 23 strain with a rare bla CTX-M-24 -harboring virulence plasmid. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2019;63:1–5. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02273-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xu M. Endogenous endophthalmitis caused by a multidrugresistant hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae strain belonging to a novel single locus variant of ST23: first case report in China. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2018;18(1):1–6. doi: 10.1186/s12879-018-3543-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thiry D. New bacteriophages against emerging lineages ST23 and ST258 of Klebsiella pneumoniae and efficacy assessment in Galleria mellonella larvae. Viruses 11.5. 2019;49:p. 411. doi: 10.3390/v11050411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Simon A. K., Hollander G. A., McMichael A. Evolution of the immune system in humans from infancy to old age. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2015;282:p. 1821. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2014.3085.20143085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haase C., Yu L., Eisenbarth G., Markholst H. Antigen-dependent immunotherapy of non-obese diabetic mice with immature dendritic cells. Clinical & Experimental Immunology. 2010;160(3):331–339. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2010.04104.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pihlgren M. Reduced ability of neonatal and early-life bone marrow stromal cells to support plasmablast survival. The Journal of Immunology. 2006;176(1):165–172. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.1.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gibbons D. L., Haque S. F., Silberzahn T., et al. Neonates harbour highly active γδ T cells with selective impairments in preterm infants. European Journal of Immunology. 2009;39(7):1794–1806. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dias E. M., Rocha-Rodrigues D. B., Geraldo-Martins V. R., Nogueira R. D. Analysis of colostrum IgA against bacteria involved in neonatal infections. Einstein (São Paulo) 15. 2017;3:256–261. doi: 10.1590/s167945082017ao3958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The corresponding WGS project has been deposited at the NCBI GenBank database under the main BioProject accession ID PRJNA556398. The project data analysis scripts and materials are hosted on GitHub (https://github.com/ivasilyev/curated_projects/tree/master/inicolaeva/klebsiella_infants).