Abstract

Oxylipins are potent lipid mediators involved in a variety of physiological processes. Their profiling has the potential to provide a wealth of information regarding human health and disease and is a promising technology for translation into clinical applications. However, results generated by independent groups are rarely comparable, which increases the need for the implementation of internationally agreed upon protocols. We performed an interlaboratory comparison for the MS-based quantitative analysis of total oxylipins. Five independent laboratories assessed the technical variability and comparability of 133 oxylipins using a harmonized and standardized protocol, common biological materials (i.e., seven quality control plasmas), standard calibration series, and analytical methods. The quantitative analysis was based on a standard calibration series with isotopically labeled internal standards. Using the standardized protocol, the technical variance was within ±15% for 73% of oxylipins; however, most epoxy fatty acids were identified as critical analytes due to high variabilities in concentrations. The comparability of concentrations determined by the laboratories was examined using consensus value estimates and unsupervised/supervised multivariate analysis (i.e., principal component analysis and partial least squares discriminant analysis). Interlaboratory variability was limited and did not interfere with our ability to distinguish the different plasmas. Moreover, all laboratories were able to identify similar differences between plasmas. In summary, we show that by using a standardized protocol for sample preparation, low technical variability can be achieved. Harmonization of all oxylipin extraction and analysis steps led to reliable, reproducible, and comparable oxylipin concentrations in independent laboratories, allowing the generation of biologically meaningful oxylipin patterns.

Keywords: eicosanoids, lipidomics, liquid chromatography, mass spectrometry, quantitation, harmonization, plasma lipids, interlaboratory comparison, oxidized fatty acids, lipid mediators

Eicosanoids and other oxylipins are potent lipid mediators produced via the oxygenation of PUFAs. PUFAs can be oxygenated enzymatically by cyclooxygenases to form prostanoids, by lipoxygenases to form hydroperoxy fatty acids, which react further to mono- and poly-hydroxylated fatty acids, or by cytochrome P450 monooxygenases giving rise to epoxy and hydroxy fatty acids, or nonenzymatically by free radicals during autoxidation (1, 2). A major portion of circulating oxylipins (>90%) is found esterified in lipids, e.g., phospholipids, triacylglycerides, or cholesterol esters (3–5).

Oxylipins include hundreds of structurally different molecules that are involved in a variety of physiological processes, such as the regulation of blood coagulation (6), endothelial permeability (4), blood pressure, and vascular tone as well as the control of kidney function (7) and the immune system (4, 8). The function of fat tissue is also regulated by these lipid mediators, and it has been shown that oxylipins intervene in the energy homeostasis regulation of insulin and its signaling pathways (6, 9). Thus, the oxylipin pattern can provide a wealth of information regarding human health and disease and is a promising technology for translation into clinical applications. Several clinical studies have already demonstrated the utility of oxylipin profiling in the identification of potential disease biomarkers, the characterization of inflammatory and oxidative status, or the monitoring of the effects of diet or drugs (1).

Currently, the analysis of oxylipins is mainly carried out by LC coupled with MS using reversed phase columns filled with sub-2 μm particles, electrospray ionization, and triple quadrupole detectors. This provides an excellent chromatographic separation of the isomeric analytes as well as a fast detection by MS following fragmentation. Furthermore, this allows the quantification of low oxylipin concentrations with highest sensitivity over a large dynamic range (1, 10–13). Prior to MS analysis, several steps of sample preparation are usually carried out. The samples are often pretreated with organic solvents to precipitate proteins (12, 14, 15) or extract lipids (5, 16). Moreover, when analyzing total oxylipins, quantified as the sum of free and bound oxylipins, alkaline hydrolysis is performed (5, 17, 18). Then, matrix compounds are removed and oxylipins are concentrated via solid phase extraction (SPE) (19–21). All steps of the sample preparation procedure have to be optimized to achieve good oxylipin recoveries and remove the matrix efficiently and thus minimize ion suppression (1, 21). The analysis of oxylipins is usually quantitative, which requires external calibration with internal standards (ISs). However, there are only a small number of companies that sell oxylipin standards, and the quality is not always guaranteed (22). Only a few standards are available with verified concentrations (1, 22). Other commercially available oxylipin standards show varying purities often resulting in a different actual concentration than the stated nominal concentration (22), thus leading to inconsistent results across different studies (23).

There are currently no harmonized protocols for the analysis of oxylipins, although it is well established that each analytical choice (i.e., type of biofluid, type of anticoagulant, free or esterified oxylipins, type of sample preparation protocol, type of instrument) can have a major influence on the detection and quantification of oxylipins (1). Therefore, after optimization of relevant steps of the oxylipin analysis, standardized and harmonized methods should be established to obtain reliable and comparable results. Vesper, Myers, and Miller (24) mainly recommend the following for clinical laboratory tests: 1) the establishment of reference methods and materials, 2) calibration using the reference system, and 3) verification of the uniformity of method results.

Using a standardized and harmonized protocol for oxylipin quantification is a mandatory prerequisite to obtain meaningful and reproducible results, as oxylipin concentrations obtained from different laboratories are rarely comparable due to varying analytical strategies and the lack of certified analytical calibrators and reference materials (1, 10, 23). Therefore, the harmonization of oxylipin analysis can enhance the use of oxylipin profiling in clinics. Another crucial step is to assess the technical variability and interlaboratory comparability of each oxylipin quantified. This will allow the identification of potential technically critical oxylipins to appropriately power clinical studies and to guarantee the relevance of oxylipin profiling involving different laboratories. So far there are only a few studies that have investigated the comparability of targeted metabolomics across laboratories (25–28), and only one study that included oxylipins (26). In the present study, we used a standardized protocol for the quantitative analysis of total oxylipins (18) due to their higher relevance in a context of biomarker discovery (1). Five independent laboratories were involved to assess the technical (intralaboratory) variability and comparability of 133 oxylipins following a standardized and harmonized protocol for sample preparation and MS analysis and using the same biological material [i.e., seven quality control (QC) plasmas] and standard calibration series.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals

Acetonitrile, methanol (MeOH), iso-propanol (LC-MS grade), and acetic acid (Optima LC-MS grade) were purchased from Fisher Scientific. Ethyl acetate (HPLC grade) was bought from VWR and n-hexane (HPLC grade) was purchased from Carl Roth. The ultra-pure water with a conductivity of >18 MΩ·cm was generated by the Barnstead Genpure Pro system from Thermo Fisher Scientific. The oxylipin standards 10-HODE, 12-HODE, 15-HODE, 13-oxo-octadecatrienoic acid, 9,10,11-trihydroxyoctadecenoic acid (TriHOME), 9,12,13-TriHOME, 9,10,13-TriHOME, 9,10,11-trihydroxyoctadecadienoic acid (TriHODE), 9,12,13-TriHODE, and 9,10,13-TriHODE were obtained from Larodan (Solna, Sweden). Other oxylipin standards and deuterated oxylipin standards used as ISs were purchased from Cayman Chemical (local distributor Biomol, Hamburg, Germany). Calcium ionophore A23187 and all other chemicals were bought from Sigma-Aldrich (Schnelldorf, Germany). Pooled human plasma was purchased from BioIVT (West Sussex, UK).

Biological samples

Different types of QC plasma having contrasted oxylipin profiles and biological significance were prepared. For QC Plasma 1 – B, human EDTA-blood was collected from 4–6 healthy male and female individuals aged between 25 and 38 years and centrifuged (10 min, 4°C, 1,200 g). Separated plasma was pooled, aliquoted, and stored at –80°C. To obtain n3-rich plasma (QC Plasma 2 – n3) human EDTA-blood was collected from an individual following n3-rich dietary supplementation, centrifuged (10 min, 4°C, 1,200 g), aliquoted, and stored at –80°C. QC Plasma 3 – S was prepared by spiking of blank plasma pool (QC Plasma 1) with oxylipin standards PGF2α, 15(S)-F2t-IsoP, 14(15)-EpETrE, 11,12-DiHETrE, 15-HETE, 14,15-DiHETE, 15-HEPE, 18-HEPE, RvD5, 17-HDHA, 12(13)-EpOME, 9,10-DiHOME at a concentration of 20 nM and LxA4, 20-HETE, 17(18)-EpETE, 19(20)-EpDPE, 16,17-DiHDPE and 13-HODE at a concentration of 50 nM in plasma. In brief, the plasma pool was gently mixed while the spiking standard in MeOH (1% v/v of plasma) was added dropwise. Prepared QC Plasma 3 was aliquoted and stored at –80°C. For QC Plasma 4 – Ca EDTA-blood was collected from one healthy individual, incubated with calcium ionophore A23187 (50 µM) for 30 min at 37°C (29), centrifuged (10 min, 4°C, 1,200 g), aliquoted, and stored at –80°C. To prepare plasma obtained from obese individuals, human EDTA-blood was collected from 10 obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m²) male and female individuals without hypertriglyceridemia and centrifuged (QC Plasma 5 – Ob-H), or human EDTA blood was collected from 7 male and female obese individuals with hypertriglyceridemia (total cholesterol > 200 mg/dl; LDL > 130 mg/dl; TG > 150 mg/dl) (QC Plasma 6 – Ob+H). The blood was then centrifugated and separated plasma was pooled, aliquoted, and stored at –80°C. A commercially obtained pooled human plasma (BioIVT, West Sussex, United Kingdom), aliquoted and stored at –80°C, was used as QC Plasma 7 – B2.

Several aliquots (100–500 μl) of each QC plasma were sent to the other laboratories to ensure that the assessment of the technical variability was independent of the biological material.

Sample preparation and LC-ESI(-)-MS/MS analysis

All laboratories used the same standardized protocol for sample preparation. Human plasma samples were extracted using SPE following protein precipitation and alkaline hydrolysis as described previously [the detailed standard operation procedure (SOP) that was provided to all laboratories can be found in the supplemental information (supplemental Tables S1–S4)] (18). In brief, to 100 μl of human plasma, 10 μl of antioxidant mixture [0.2 mg/ml BHT, 100 μM indomethacin, 100 μM trans-4-(-4-(3-adamantan-1-yl-ureido9-cyclohexyloxy)-benzoic acid (t-AUCB) in MeOH] and 10 μl of IS solution [100 nM of each: 2H4-8-iso-PGF2α, 2H4-6-keto-PGF1α, 2H4-PGF2α, 2H11-8,12-iso-iPF2α-VI, 2H4-PGB2, 2H5-LxA4, 2H5-RvD1, 2H5-RvD2, 2H4-LTB4, 2H4-9,10-DiHOME, 2H11-11,12-DiHETrE, 2H4-13-HODE, 2H4-9-HODE, 2H6-20-HETE, 2H8-15-HETE, 2H8-12-HETE, 2H8-5-HETE, 2H4-12(13)-EpOME, 2H11-14(15)-EpETrE, 2H11-8(9)-EpETrE in MeOH] were added. Following protein precipitation with iso-propanol and alkaline hydrolysis at 60°C for 30 min using 0.6 M potassium hydroxide (MeOH/water, 75/25, v/v) samples were extracted using Bond Elut Certify II SPE cartridges (200 mg, 3 ml; Agilent, Waldbronn, Germany) as described (12, 13, 18). Oxylipins were eluted into glass tubes containing 6 μl of 30% glycerol in MeOH using ethyl acetate/n-hexane/acetic acid (75/25/1, v/v/v). Samples were evaporated and the residue was reconstituted in 50 μl of MeOH. The analysis of the samples was performed using a sensitive LC-ESI(-)-MS/MS method with optimized mass spectrometric and chromatographic parameters as described (12, 13), which was provided to all participating laboratories. The quantitative analysis was based in all laboratories on the same standard calibration series comprising 133 oxylipins with isotope-labeled ISs (30), allowing the same analyte/IS assignment in the laboratories.

Study design

A comprehensive SOP (supplemental Tables S1–S4) for sample preparation and MS analysis was standardized and validated in the reference laboratory (laboratory 1). Based on the European Joint Programming Initiative Grant of the European Union, it was possible to share not only the protocol but also the QC plasmas, the standard calibration, and the extensive LC-ESI(-)-MS/MS method with the participating laboratories.

Five laboratories participated in the interlaboratory comparison. Each participating laboratory analyzed the different QC plasmas in triplicate on two consecutive days or, in case of QC plasma 1, on three consecutive days. To investigate the contribution of the instrumental LC-MS analysis to the overall variability of the results, two additional triplicates of QC plasma 1 were prepared by laboratories 2 and 5 and analyzed using the MS platforms from laboratories 1 (MS1) and 3 (MS3) (supplemental Fig. S1). Furthermore, all participants were provided a data submission template including information on the analysis and calculation of the concentrations. The oxylipin concentrations in the plasma pools were reported in nanomoles per liter. For each triplicate determination, mean and SD were calculated. If in a triplicate determination the concentration of an analyte in one sample was below the lower limit of quantification (LLOQ), the LLOQ threshold was filled in for this sample and the mean and SD were calculated. This approach was chosen, as the omission of analyte concentrations below LLOQ leads to bias of the results (31). If concentrations in two or all samples were below the LLOQ, the concentration of the analyte was set to the LLOQ. Moreover, all participants were asked to fill out a short questionnaire with general remarks on the analysis.

Statistical analysis

Several statistical methodologies were used to assess the intra- and interlaboratory analytical variabilities. Coefficients of variation (CVs) were calculated to determine the intra- and inter-day variability for each laboratory and each QC plasma. Multivariate methods were applied to assess the interlaboratory variability. The matrix comprised 75 samples (analysis of six plasmas on two consecutive days + analysis of QC plasma 1 on three consecutive days × five laboratories) and 74 oxylipins (>LLOQ for at least one QC plasma and at least in one laboratory). First, a principal component analysis (PCA; unsupervised analysis) was built to observe the overall variability. Then, in order to specifically investigate the influence of the laboratory, a partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA; supervised analysis) was performed using the laboratory as the discriminant variable.

In order to compare the measurements from multiple laboratories, the consensus values and their associated uncertainties (u) were calculated by the median of the means (MEDM) method, as is previously described in (26). Briefly, the means and SDs of the triplicates on day 1 and day 2 (and day 3 for the QC plasma 1) for each quantified oxylipin were calculated. Then the median of the laboratories’ means (i.e., MEDM consensus values) were calculated for the oxylipins quantified in at least three laboratories. The associated standard uncertainties (u) for the MEDM consensus values were calculated as u = √(π/2m) × 1.483 × MAD where m and MAD are the number of laboratories and the median of absolute deviation of the laboratory means, respectively.

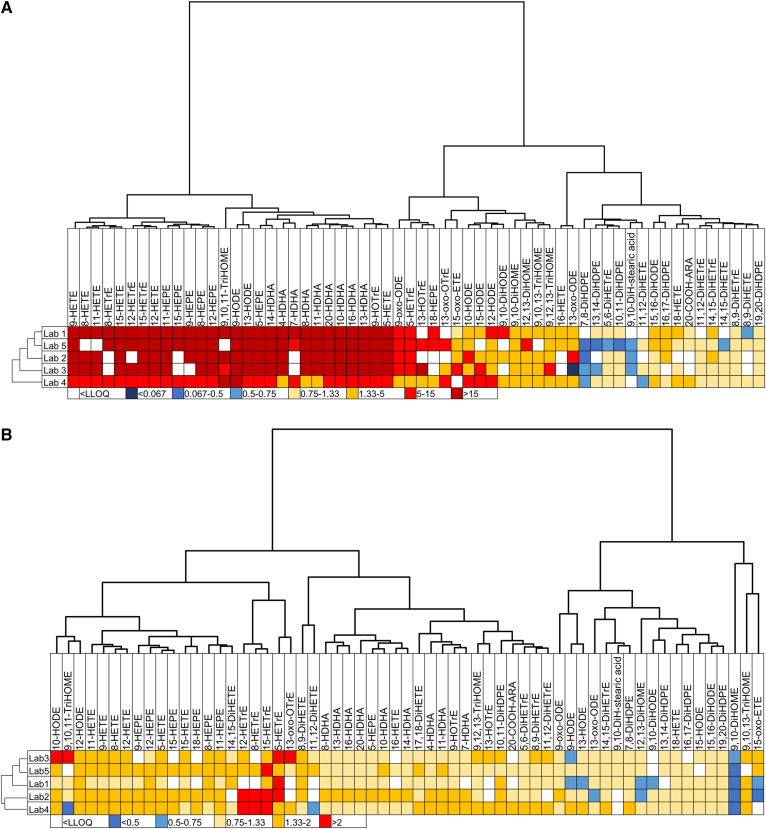

To assess the ability of laboratories to identify similar differences in the oxylipin profiles between two different QC plasmas and therefore to provide similar biological interpretation, ratios between QC plasmas 2, 3, 4, and 7 against QC plasma 1 were calculated for each laboratory as well as the ratios of QC plasma 5 (Ob-H) against QC plasma 6 (Ob+H). Additionally, to show similarities between the laboratories and between the oxylipins, hierarchical clustering analysis was performed with Euclidean distances and the Ward aggregation method.

To assess the contribution of the interlaboratory variability in the LC-MS-specific results, only a low number of samples were used; thus, no statistical analysis was performed on these specific samples and differences were assessed visually. For each quantified oxylipin and each laboratory of preparation, differences of concentration between the lower and the higher sample from MS1 (Δ intra-MS1) and MS3 (Δ intra-MS3) were calculated as well as the difference of concentration between the two closest samples from MS1-triplicate and MS3-triplicate (Δ inter-MS). When the Δ inter-MS was higher than the difference observed within the triplicate (Δ intra-MS), the MS effect was considered as consistent.

All statistical analyses were carried out using R version 3.1.3, Microsoft Excel Office version 365, and SIMCA (Umetrics AB, version 14).

RESULTS

Analytical variance of oxylipin analysis

All participating laboratories were able to simultaneously quantify 133 oxylipins in the standard calibration series using the provided LC-MS/MS method. Deviations from the SOP and analytical instruments used can be found in the supplemental information (supplemental Table S5). Oxylipins were analyzed in seven different QC plasmas in triplicate (i.e., three different samples were prepared) on two consecutive days to determine the analytical variance of the method. In all laboratories, an average of 84 oxylipins (63%) were above the limit of quantification (LLOQ, Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Number of quantified oxylipins

| QC Plasma 1 (B) | QC Plasma 2 (n3) | QC Plasma 3 (S) | QC Plasma 4 (Ca) | QC Plasma 5 (Ob-H) | QC Plasma 6 (Ob+H) | QC Plasma 7 (B2) | |

| Laboratory 1 | 80 | 82 | 90 | 84 | 85 | 92 | 103 |

| Laboratory 2 | 68 | 71 | 75 | 75 | 69 | 71 | 89 |

| Laboratory 3 | 71 | 76 | 79 | 80 | 71 | 70 | 97 |

| Laboratory 4 | 93 | 88 | 96 | 95 | 92 | 95 | 104 |

| Laboratory 5 | 83 | 79 | 89 | 86 | 84 | 84 | 91 |

Seven plasma pools were analyzed in five independent laboratories according to the SOP (including 133 oxylipins). Shown is the number of oxylipins above LLOQ quantified in each laboratory for each plasma pool.

Regarding the oxylipin pattern of QC plasmas 1–6, the determined oxylipin concentrations were in a similar range (0.16–547 nM), while in QC plasma 7 (mainly for hydroxy-PUFA and multi-hydroxylated oxylipins, as well as for linoleic acid-derived epoxy-PUFAs and oxo-PUFAs), 10- to 25-fold higher concentrations were found.

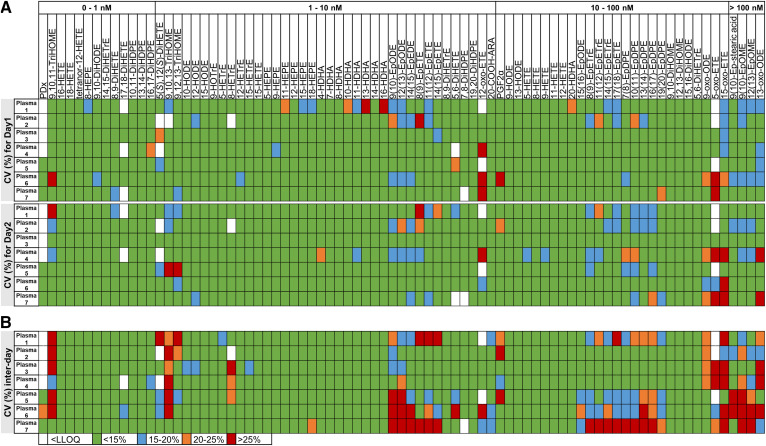

The results of the intra-day and inter-day variability of the oxylipin analysis in the reference laboratory (laboratory 1) is shown in Fig. 1. For this laboratory, the variabilities were assessed for 81 quantified oxylipins. Overall, low intra-day variability (CV <15%) was observed for 85% of oxylipins. The inter-day variability was also low (CV <15% for 73% of oxylipins). However, for epoxy-PUFAs as well as oxo- and trihydroxy-PUFAs a variance up to >25% was observed. This higher variability did not correlate with concentration. There was no difference between the different types of plasma.

Fig. 1.

Intra-day (A) and inter-day (B) variability of the oxylipin analysis in laboratory 1. Oxylipin analysis in the seven QC plasmas was carried out in triplicate on two consecutive days in the reference laboratory (laboratory 1) and the variability within each day as well as the inter-day variability were determined. The CVs were calculated using the mean concentration and SD . Shown are the CVs of 81 quantified oxylipins in the seven plasmas in laboratory 1 displayed in four different colors.

Increased intra-day and inter-day variability for epoxy-PUFAs could also be observed in the other participating laboratories (supplemental Figs. S2–S5). For laboratories 2, 3, 4, and 5, the variabilities were assessed for 69, 73, 94, and 82 quantified oxylipins, respectively. These laboratories presented higher variabilities overall, except for laboratory 2, with low intra-day variability (CV <15%) for 81% of oxylipins for day 2 and low inter-day variability (CV <15%) for 72% of oxylipins (supplemental Fig. S2), which is consistent with laboratory 1. Notably, for laboratories 2–5, the intra-day variability for day 1 was higher than for day 2, which impacted the inter-day variability (supplemental Figs. S2–S5). For example, laboratory 3 (supplemental Fig. S3) showed the highest inter-day variability (only 39% of oxylipins with a CV <15%), which is due to the very high intra-day variability for day 1 (CV <15% for 36% of oxylipins) compared with day 2 (CV <15% for 61% of oxylipins). For laboratories 4 and 5, the inter-day variability was also high with a CV <15% only for 52% and 44% of the oxylipins, respectively.

Laboratory comparison

The quantified oxylipin concentrations in all QC plasmas by all laboratories can be found in the supplemental information (supplemental Table S6).

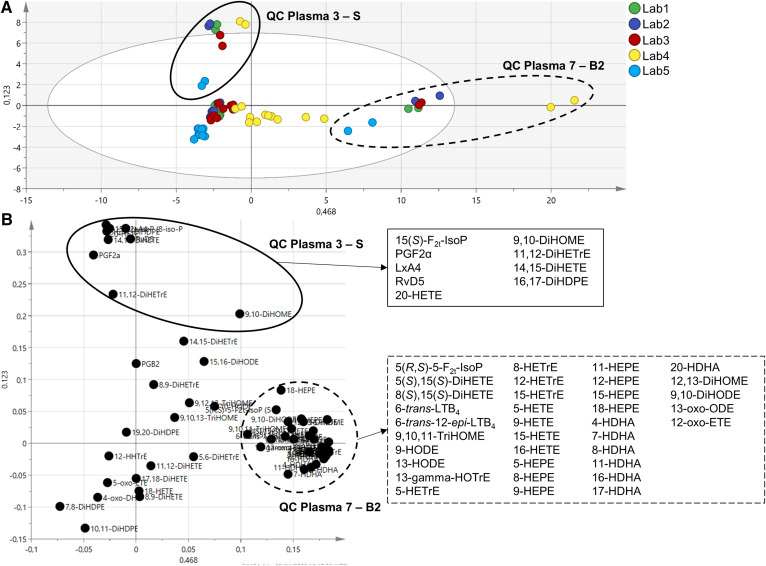

Unsupervised multivariate analysis (i.e., PCA) was first performed to assess the variability of the overall oxylipin profiles obtained in each laboratory and its major determinant (i.e., type of QC plasma, laboratory). The initial PCA shows that the main variability (40.5% on the first component) is related to the type of QC plasma with QC plasma 7 (B2) being different from the others. The variability on the second component is much lower (i.e., 18.6%) and mainly driven by laboratory 4 (supplemental Fig. S6A). The loading plot shows that the discrimination of laboratory 4 is based mainly on epoxy-PUFAs (supplemental Fig. S6B). Epoxy-PUFAs have already been noted for their high technical variability. Moreover, in laboratory 4, the samples could either not be measured directly or they had to be injected several times due to technical issues (as described in supplemental Table S5), the latter of which results in increased concentrations of epoxy-PUFAs (supplemental Fig. S7). Therefore, we speculated that including the epoxy-PUFAs in the PCA model might have artificially driven the discrimination of laboratory 4. To exclude this possibility and to precisely determine the influence of the laboratory on the variability of the oxylipin profiles, the 12 epoxy-PUFAs were excluded from further biostatistical analysis.

A second PCA model was built without the epoxy-PUFAs (matrix with 75 samples and 62 oxylipins). The score plot (Fig. 2A) confirms that the variability on the first component (46.8%) is related to the type of plasma with QC plasma 7 (commercial plasma rich in hydroxy-PUFAs) being clearly different from the others. In this second model, the variability on the second component (12.3%) is also related to the type of QC plasma with QC plasma 3 (plasma spiked with PGF2α, 15(S)-F2t-IsoP, 14(15)-EpETrE, 11,12-DiHETrE, 15-HETE, 14,15-DiHETE, 15-HEPE, 18-HEPE, RvD5, 17-HDHA, 12(13)-EpOME, 9,10-DiHOME, LxA4, 20-HETE, 17(18)-EpETE, 19(20)-EpDPE, 16,17-DiHDPE, and 13-HODE) being different from the others. The loading plot (Fig. 2B) shows that the oxylipins that contribute the most to the discrimination of QC plasmas 7 and 3 are consistent with the highly concentrated oxylipins in the profiles of the plasma, i.e., enriched with hydroxy-PUFAs and spiked with specific oxylipins, respectively.

Fig. 2.

Principal components analysis (PCA) model without epoxy-PUFAs. The model was built with 75 samples and 62 oxylipins (R2X = 0.592 and Q2 = 0.544). A: The score plot shows that the main variability is related to the type of plasma: QC plasma 7 (B2) (dotted circle) and QC plasma 3 (S) (solid circle). B: The loading plot displays oxylpins contributing to the discrimination of QC plasmas 7 (dotted circle) and 3 (solid circle). Lists of these oxylipins are depicted in respective boxes.

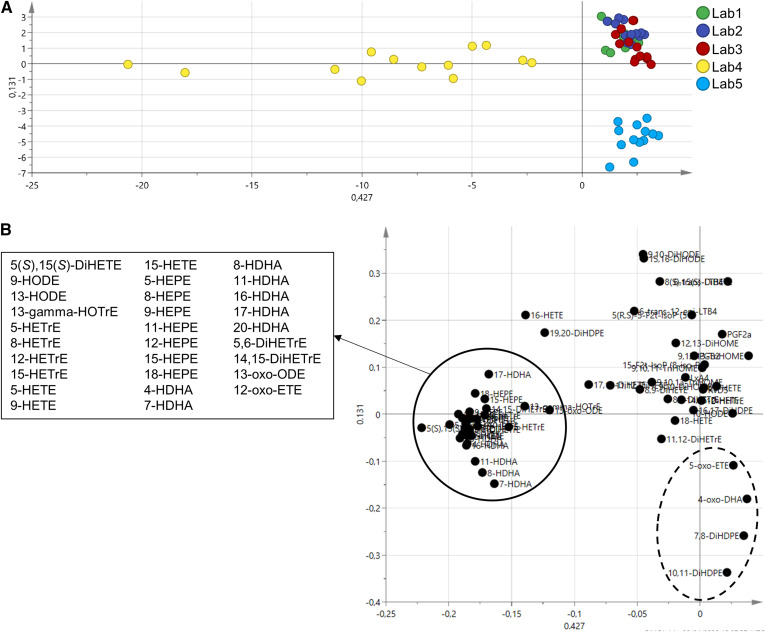

In order to go further in the assessment of the laboratory influence, a supervised multivariate method (i.e., PLS-DA) using the laboratory as discriminant variable was applied. For this, we again excluded the 12 epoxy-PUFAs from the PCA model as well as samples from QC plasma 7 (i.e., plasma with a very distinct oxylipin profile, 10 samples excluded) to highlight the laboratory effect. This allowed the generation of a PLS-DA model with good discrimination performances (R2Y = 0.78 and Q2 = 0.729). On the first component of the cross-validated score plot (CV score plot) bringing 42.7% of variability (Fig. 3A), laboratory 4 clearly distinguishes itself. The loading plot (Fig. 3B) shows that this difference is driven by the hydroxy-PUFAs. On the second component, the variability is much lower (13.1%). However, it shows that laboratory 5 is different from the others. Concerning the other three laboratories, no separation could be achieved with the model, suggesting very similar oxylipin profiles.

Fig. 3.

PLS-DA. The model was built with 65 samples and 62 oxylipins (R2Y = 0.78 and Q2 = 0.729). A: The cross-validated score plot shows that laboratories 4 and 5 distinguish themselves from the others. B: The loading plot shows the oxylipins contributing to the discrimination of laboratory 4 (solid circle); the list of these oxylipins indicates that this discrimination is driven by hydroxy-PUFAs. With less variability, four oxylipins (dotted circle) contribute to the discrimination of laboratory 5.

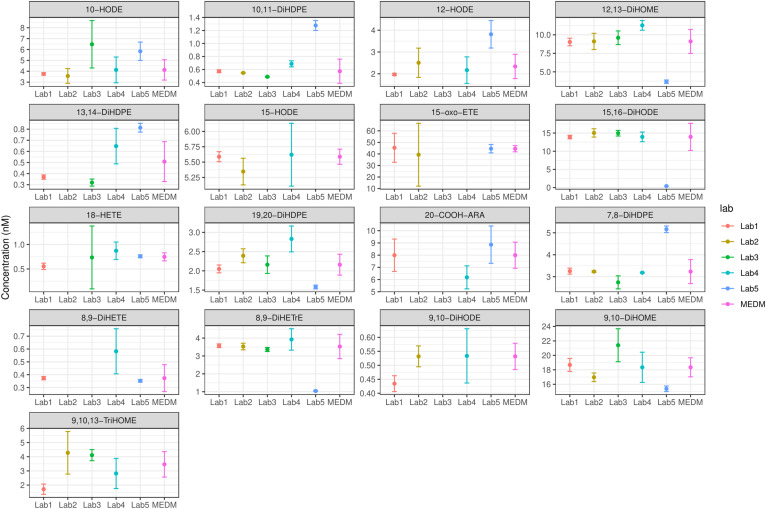

The consensus values were evaluated using the MEDM approach to assess the interlaboratory comparability. The consensus values were deemed acceptable when the coefficient of dispersion (COD) (COD = 100 × u/MEDM) was less than 40% as described in (26). The mean ± SD for each laboratory and MEDM consensus values ± u were plotted for oxylipins with an acceptable consensus value. The MEDM ± u and COD for oxylipins quantified in all QC plasmas can be found in the supplemental information (supplemental Tables S7, S8; supplemental Figs. S9–S14).

In total, 78 oxylipins were reported for QC plasma 1 in all laboratories, with an acceptable consensus value for 17 oxylipins (22%) (Fig. 4). Notably, the same analysis was performed without laboratory 4 (due to the issues encountered during sample analysis) and shows that an acceptable consensus value is obtained for 73% of the oxylipins (47 out of 64 quantified oxylipins) (supplemental Fig. S8). In QC plasmas 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7, the consensus values were acceptable for 19, 29, 29, 21, 23, and 60 oxylipins, respectively.

Fig. 4.

MEDM location plots. Plots were created for oxylipins quantified in QC plasma 1 by all laboratories. Shown are the mean concentrations ± SD determined in each laboratory and the MEDM ± u for 17 oxylipins with acceptable consensus value (COD <40%).

Identification of differences between plasma pools

To assess the ability of the laboratories to identify similar differences (in magnitude and direction) between two plasmas, we compared the ratios calculated between different QC plasmas by each laboratory. For this purpose, the concentration of each oxylipin for a given QC plasma was divided by the oxylipin concentration obtained for another QC plasma.

First, we compared the differences observed between two very contrasted QC plasmas, i.e., QC plasma 7 (commercial plasma rich in hydroxy-PUFAs and linoleic acid metabolites) versus QC plasma 1 (plasma prepared from fresh EDTA-blood of healthy donors immediately stored at −80°C). For 98% of the oxylipins (matrix consisting of 60 oxylipins), the ratio between QC plasma 7 and QC plasma 1 was similar for the five laboratories. The only noticeable difference in concentration ratios of compared QC plasmas occurred between laboratory 2 and laboratory 3 for 13-oxo-ODE (concentration ratio of 5–15 and <0.067, respectively), whereas the laboratories 1, 4, and 5 obtained very similar ratios between compared plasmas (concentration ratio 1.33–5; Fig. 5A).

Fig. 5.

The ability of laboratories to identify similar differences in oxylipin profiles. Shown are heatmaps with hierarchical clustering (Euclidean distances and Ward aggregation method) for laboratories and oxylipins. A: Heatmap of ratio between QC plasma 7 (B2) (rich in hydroxy-PUFAs) and QC plasma 1 (B). The range of ratio goes from <0.067 to more than 15. B: Heatmap of ratio between QC plasma 5 (Ob-H) and QC plasma 6 (Ob+H). The range of ratio goes from <0.5 to more than 2.

A second laboratory comparison was made with the ratios calculated between the QC plasmas obtained in obese individuals with or without hypertriglyceridemia (QC plasma 5 vs. QC plasma 6). For 92% of the oxylipins (matrix consisting of 61 oxylipins), the ratios were very similar between the five laboratories. However, ratios in opposite directions were obtained for 9,10,11-TriHOME, 11,12-DiHETE, 9-HODE, 13-HODE, and 15-oxoETE (Fig. 5B).

Interlaboratory variability in the LC-MS/MS-specific results

Knowing that the different laboratories use different mass spectrometers, the contribution of this factor on the overall variability of the oxylipin profiles was assessed (i.e., 42 oxylipins that were detected at a concentration above the LLOQ in all laboratories). The oxylipin profiles were generated from samples prepared in two different laboratories (laboratory 2 and laboratory 5), and the prepared samples were analyzed on either MS platform 1 or 3. The described approach should make it possible to separate the laboratory specific-variance from the instrument-specific variance. For samples prepared in laboratory 2, seven oxylipins (i.e., 9,10,13-TriHOME, 9,12,13-TriHOME, 10-HODE, 12-HETrE, 12-HEPE, 7-HDHA, and 11(12)-EpETrE) had different concentrations depending on where the LC-MS analysis was performed (MS1 or MS3), whereas in samples prepared in laboratory 5, only one oxylipin (i.e., 12-HETrE) had a different concentration depending on the MS platform (supplemental Table S9, supplemental Fig, S18). Notably, the intra-MS variabilities (i.e., variability within each independent triplicate) were generally higher for the samples prepared in laboratory 5, which impairs the detection of valid differences between the two sets of triplicate analyses.

DISCUSSION

The quantitative analysis of eicosanoids and other oxylipins has gained a lot of attention, especially with regard to the discovery of new biomarkers in health and disease (1). However, the analysis of oxylipins is complex and can be influenced by many factors, such as sample preparation and LC-MS-based quantification. For this reason, standardized procedures are required to achieve comparable and reproducible results. This was assured in this study by providing a detailed SOP (supplemental information), calibration series, and IS solutions to all the laboratories. This harmonization allows the extent and sources of technical variability to be assessed and investigation of which oxylipins can be robustly quantified as reliable potential biomarkers.

Technical variability of oxylipins

In each participating laboratory, the precision and reproducibility of the analytical method was determined using seven QC plasmas. In the reference laboratory (laboratory 1), the lowest inter-day variance (inter-day) was observed (<15% for 73% of oxylipins, Fig. 1). The SOP and LC-MS method have been developed here, and thus this laboratory is best trained in the procedures. The achieved analytical variances meet the criteria of international guidelines, i.e., analytes above the LLOQ should have a precision of <15% (32, 33). Low inter-day variances for 72% of oxylipins (<15%, supplemental Fig. S2) were also observed in laboratory 2, whose personnel were trained in the reference laboratory. In laboratories where the analysis was carried out only based on the SOP, slightly higher variances (>20%, supplemental Figs. S3–S5) were obtained for 38–56% of oxylipins. Although all participating laboratories are experienced in the field of oxylipin analysis, they have established methods (1) that slightly differ from the SOP used in this interlaboratory comparison. Thus, the personnel were not used to the detailed procedures, and a training effect could be observed with lower variance on day 2 of analysis than on day 1. It is quite possible that a slight difference in the handling of samples could lead to higher variances, as oxylipins can be easily formed or degraded (30). Training of technical skills for accurate sample preparation has been found to be of general importance for quantitative analysis, as discussed by Percy et al. (34) and Siskos et al. (25). Therefore, our results show that not only is the use of the same protocol important to achieve comparability between the laboratories but also personnel that have been trained in the technical skills required for the sample preparation procedure.

It should be noted that the observed CVs in reference laboratory 1 were comparable to those described by Ostermann et al. (18) (CV <20% using the same sample preparation protocol). However, when comparing with the independent method for the quantitation of total oxylipins described by Quehenberger et al. (17) (CV 5–20%), the observed CVs are slightly higher, indicating further potential of optimizing the protocol.

Notably, in all laboratories, higher CVs were observed for epoxy- and oxo-PUFAs as well as for TriHOMEs (up to ≥25%). We believe that this higher variance may be caused by deviating from the SOP as different steps of sample preparation can influence the quantified oxylipin concentration. Especially, epoxy-PUFAs can be artificially formed during sample preparation. Ostermann et al. (18) described the drying of samples on the SPE cartridges as a particularly critical step during sample preparation. During the SPE, the PUFAs released in large quantities during hydrolysis can adsorb on the phase material (mainly on nonendcapped silica groups) and be oxidized by atmospheric oxygen, mainly to epoxy-PUFAs (18, 35, 36). In addition, the analysis of the samples in laboratory 5 was carried out by two operators, probably resulting in increased variability. Using the presented sample preparation protocol, the inter-operator variability for most oxylipins is ≤21% (18).

Furthermore, reinjection of lipid extracts into the LC-MS instrument due to technical issues led to increased concentrations of epoxy-PUFAs. The fact that multiple injections of the same extract lead to an increased variability (up to 24% higher) was earlier described by Reinicke et al. (37) for arachidonic acid-derived eicosanoids. Reinicke et al. (37) examined the within-run (reinjection of the same sample 10 times within one analytical run) and between-run (reinjection of the same sample on 10 consecutive days) variability of oxylipins, whereby the variability was in a range of 1–24% in each case.

Although the individual laboratories have complied with the SOP as far as possible, the laboratories are nevertheless equipped with different analytical instruments. For this reason, we aimed to investigate the presence of confounding effects across laboratories by preparing and analyzing the samples in different laboratories. Overall, the observed influence of the MS instrument used is negligible. However, the differences in results obtained when analyzing sample extracts on two different MS platforms were interpreted as inherent acquisition platform variability. Whereby, this variability can be caused by various factors, such as variability in chromatographic performance, peak integrations, or hardware-associated sensitivity or specificity. Although different concentrations were obtained for 7 out of 42 quantified oxylipins in plasma extracts from laboratory 2, a clear MS platform effect could only be observed for 12-HETrE. This is consistent with the results from Percy et al. (34), indicating that the accuracy of the MS platform depends mostly on user handling. The quantification was carried out by an external calibration series with isotopically labeled standards (analyte/IS peak area ratio). Thus, sensitivity of the instruments impacts the number of analytes detected but not the determined concentrations. Overall, our results for the quantification of oxylipins show that comparable results are obtained if different MS instruments are used, which may differ in sensitivity.

Interlaboratory comparability of the total oxylipin profiles

A large number of laboratories deal with the analysis of oxylipins. Each laboratory has developed its own methods for this purpose, whereby an impressive number of oxylipins are covered by todays methods (1). However, methods differ greatly, which generates technical variance (1) and makes it difficult to assess the real interlaboratory comparability of oxylipin profiles. There are only a very small number of interlaboratory comparisons that investigate the comparability of lipidomic approaches (25–28) and even fewer studies that explicitly address the precision, reproducibility, and comparability of oxylipin analysis using a standardized and harmonized protocol. The few existing studies that address these points therefore show poor comparability (26, 38, 39).

The procedures for investigating interlaboratory comparability and reproducibility differ. A direct comparison of absolute concentrations is hardly possible and results in very large deviations, whereby the variability among laboratories can be caused mainly by the quality of the analytical standards used. When comparing clinical studies, it becomes apparent that the quality of the analytical standards used for quantification is a critical parameter, which may lead to noncomparable results (23). In order to solve this issue Hartung et al. (22) recently described a strategy to verify the concentration of commercially available standards. Because this strategy was not used in previous studies, interlaboratory comparisons can today only be evaluated under consideration of relative results. A common evaluation strategy in lipidomic studies is the normalization to a standard material, such as the National Institute of Standards and Technology standard reference material (NIST SRM) plasma. This normalization significantly improves variance and reproducibility (25, 27). In our study, we show that by normalization (the QC plasmas were normalized to QC plasma 1) and subsequent evaluation of relative results, no differences between laboratories are identified (Fig. 5, supplemental Figs. S15–S17).

The major field of application of targeted oxylipin metabolomics is biological studies aiming to provide a relative comparison of results, such as case and control groups (40–42). When comparing the two QC plasmas of obese subjects with and without hypertriglyceridemia in this study, for most oxylipins comparable ratios were identified, while for only 8% of the oxylipins a trend in the opposite direction was observed (Fig. 5B). Thus, our data clearly demonstrate that LC-MS oxylipin quantification is suitable to characterize differences in biological samples, e.g., in clinical studies.

The comparability of interlaboratory results after standardization to a reference material leads to the fact that a harmonization of methods to a standard material is increasingly desirable. Many describe the importance of standard reference materials, such as the NIST SRM plasma, to ensure interlaboratory comparability and to harmonize data sets (10, 24, 25, 27, 43). However, the introduction of a common standard material does not solve the problem that absolute concentrations are not comparable. This is most clearly shown by the comparison of two independent studies by Bowden et al. (26) and Quehenberger et al. (43) where the NIST SRM plasma was solely analyzed. When comparing the results of Bowden et al. (26) with the results of Quehenberger et al. (43), clear differences in the absolute oxylipin concentrations become apparent. Bowden et al. (26) quantified 10, 6.8, and 2.4 nM for 5-HETE, 12-HETE, and 15-HETE, respectively. While Quehenberger et al. (43) quantified the concentrations for these oxylipins at 11.9, 4.22, and 0.8 nM. Thus, the deviations in the quantified oxylipins 5-, 12-, and 15-HETE are respectively 14, 61, and 199% (26, 38, 43).

Although a relative quantification based on a reference standard is often used, this approach is limited and cannot replace a true quantification of concentrations, i.e., moles per amount per volume or gram sample. In order to compare molar concentration determined in independent laboratories, the consensus value is often evaluated. There are different methods whose advantages and disadvantages should be weighed beforehand (38). In the laboratory comparison by Bowden et al. (26), the MEDM approach was used to compare the results and the COD was calculated. This method is especially robust against outliers (independent of the intra-laboratory variance), as the participating laboratories processed the used NIST SRM plasma applying their own protocols and analytical methods, and the results varied considerably between laboratories (26). The disadvantage of the MEDM method, however, is that it does not take into account intra-laboratory variance, as all laboratories are equally weighted (38, 44). In the study by Bowden et al. (26), participating laboratories quantified all possible lipid classes; however, a large number of oxylipins (143 oxylipins) were quantified in only one laboratory. Further, only 5-HETE, 12-HETE, and 15-HETE were quantified in a sufficient number of laboratories to calculate a consensus value, with the COD being 13, 23, and 27%, respectively. However, these results show that the different procedures result in different analytical concentrations, so that the method used can be a limiting factor.

Using standardized and harmonized protocols for oxylipin quantification can greatly reduce variance and promote the generation of meaningful and reproducible results when data are to be compared across multiple laboratories. In the absence of such harmonization efforts, robust performance-based quality assurance protocols must be implemented to allow the harmonization of data sets processed using discrete protocols and will be critical to enhance the use of oxylipin profiling in clinics. Our study is the first where harmonization of all procedures has been carried out allowing a comparison of absolute concentrations of oxylipins determined in five different laboratories. This comparison is possible because, in the present study, a standardized protocol for sample preparation was used, and the standard calibration series (30) as well as the LC-MS method were established in all participating laboratories in order to reduce as many factors responsible for variability as possible. The concentration of the standard calibration series used was characterized as described by Hartung et al. (22) based on standards with verified concentrations. Based on the standard calibration series, all laboratories determined the limit of detection and LLOQ using a provided protocol, which takes into account the validation criteria of the European Medicines Agency guideline on bioanalytical method validation (limit of detection set to concentration with signal-to-noise ratio ≥3; LLOQ set to concentration with signal-to-noise ratio ≥5 and accuracy within ±20% of nominal concentration) (32). Sample preparation was carried out according to the same optimized protocol in all laboratories, also taking into account the use of materials from the same manufacturers, as different sample preparation procedures can influence the amount of quantified oxylipins (1, 23). Moreover, the used protocol for sample preparation was optimized to yield high reproducibility following the evaluation of various saponification techniques (1, 18). Furthermore, the integration of peaks was manually validated to ensure optimum precision, as automatic peak integration may lead to incorrect peak integration. Especially, the integration of peaks close to LLOQ or with unusual peak shapes using automatic integration may lead to deviating results.

With our study, we show that the harmonization of parameters that can cause technical variability leads to comparable absolute oxylipin concentrations obtained in different laboratories. If the quantified oxylipin concentrations for all plasma pools in all laboratories are presented in a PCA model, for three of five laboratories, no differences between the results can be observed (Fig. 2). The analysis instead reveals differences between the plasma pools, indicating that biological differences could be detected in batch samples analyzed in different laboratories. Notably, laboratory 4, showing the highest variability and most extreme deviation from the other results, experienced a MS/MS turbo pump failure mid analysis leading to a prolonged delay between sample processing and data acquisition, representing a serious deviation from the described protocols. To better reveal a difference between laboratories, the analysis tool can be forced to display such differences, as shown by the PLS-DA model (Fig. 3). If the results from laboratory 4 were excluded, the consensus value estimates were acceptable for 73% of the oxylipins in QC plasma 1. In general, excluding laboratory 4 increased the number of acceptable consensus values (supplemental Tables S7, S8). It is particularly enlightening that the long post extraction acquisition delays and repeated injections led to higher concentrations of epoxy-PUFAs in these samples (supplemental Figs. S7, S8). Furthermore, excluding the epoxy-PUFAs from the analysis, higher levels and variance in hydroxy-PUFAs were also observed in laboratory 4 data (Fig. 3). Therefore, extreme caution is generally suggested in the timing of post preparation delays in data acquisition.

Oxylipins have the potential to provide a wealth of information regarding human health and disease and are a promising technology for translation into clinical applications. The changes in the oxylipin profile are of particular importance, as physiological effects are not attributed to a single oxylipin but to an interplay of many oxylipins or a general shift of the oxylipin profile (1, 45). In addition, the oxylipins in biological samples come in a concentration range of several orders of magnitude (>4) with differences in polarity and stability. Therefore, the targeted metabolomic analysis of these potent lipid mediators requires sensitive and precise methods to detect as many different oxylipins as possible and to detect even the smallest concentration differences (1, 46–48).

The presented study is unique in evaluating comparability and reproducibility of oxylipin analysis. We are able to show for the first time that the standardization and harmonization of the processing protocol as well as the analysis allows an interlaboratory comparison not only in terms of relative results, but also in the absolute concentrations obtained. In the lipidomics community, there is an increasing demand for standardized methods (1, 10). Our study could be used as the first step for the development of internationally agreed upon oxylipin quantification procedures and benchmarks. Moreover, the standardization of routine performances will allow direct comparisons of data sets generated at various laboratories.

CONCLUSIONS

Our study is the first to investigate the technical variability and interlaboratory comparability of the targeted metabolomics analysis of total oxylipins. Epoxy- and oxo-PUFAs appear to be particularly sensitive to analytical sample handling, and delayed postprocessing analyses are to be avoided. In addition, when analyzing total oxylipins, special care should be taken during the drying steps when using non-endcapped silica materials. However, our findings show that reproducible results with low variability can be obtained using standardized protocols for sample preparation and analysis, and that specific training of personnel in these complex protocols reduces variability. This will be crucial to appropriately power experimental designs and to enhance the identification of reliable and relevant biomarkers of disease.

Overall, we could show that with appropriate standardization, a direct comparison of absolute concentrations obtained in different laboratories is possible, which opens a new door for the quantitative analysis of oxylipins and into clinical applications.

Limitations of this study

The small number of participating laboratories in this study is a significant limitation. However, the five participating laboratories represent three countries and laboratories in academic, governmental, and industrial environments, arguing that the findings have broad implications. The lack of a commercially available certified reference material for total oxylipins also limits future direct comparisons to the data reported here. Future efforts in this area should expand the number of laboratories to no less than 7 and include a commercially available reference plasma (e.g., NIST SRM 1950–Metabolites in Human Plasma) allowing the development of consensus values for the total oxylipin content of this material.

Data availability

All data are contained within the article or supplemental data.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the following individuals for their technical support in sample preparation and analysis: Ira J. Gray, Heike Zweers, and Inci Dogan.

Footnotes

This article contains supplemental data.

Author contributions—A.I.O., J.W.N., C.G., and N.H.S. research design; M.M., N.K., A.I.O., and N.H.S. methodology; M.M., N.K., A.I.O., and N.H.S. sample and standard preparation; M.M., C.D., M.P., J.D-C., and M.R. instrumental analysis; M.M., C.D., M.P., J.D-C., and M.R. data evaluation; J.B-M., J.W.N., C.G., and N.H.S. supervision; M.M., C.D., C.G. and N.H.S. writing. All authors had input into the final manuscript.

Funding and additional information—This study was supported by German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) Grant 01EA1702 to N.H.S. in the framework of the European Joint Programming Initiative, “A Healthy Diet for a Healthy Life” (JPI HDHL; http://www.healthydietforhealthylife.eu/) to N.H.S., C.G., J.B-M., and J.W.N. Additional support was provided by U.S. Department of Agriculture Project 2032-51530-025-00D to J.W.N. The US Department of Agriculture is an equal opportunity employer and provider.

Conflict of interest—The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

Abbreviations—

- COD

- coefficient of dispersion

- CV

- coefficient of variation

- DiHDPE

- dihydroxydocosapentaenoic acid

- DiHETE

- dihydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid

- DiHETrE

- dihydroxyeicosatrienoic acid

- DiHOME

- dihydroxyoctadecenoic acid

- EpDPE

- epoxydocosapentaenoic acid

- EpETE

- epoxyeicosatetraenoic acid

- EpETrE

- epoxyeicosatrienoic acid

- EpOME

- epoxyoctadecenoic acid

- HDHA

- hydroxydocosahexaenoic acid

- HEPE

- hydroxyeicosapentaenoic acid

- IS

- internal standard

- LLOQ

- lower limit of quantification

- Lx

- lipoxine

- MEDM

- median of the means

- MeOH

- methanol

- NIST SRM

- National Institute of Standards and Technology standard reference material

- PCA

- principal component analysis

- PLS-DA

- partial least squares discriminant analysis

- QC

- quality control

- Rv

- resolvin

- SOP

- standard operation procedure

- SPE

- solid phase extraction

- TriHODE

- trihydroxyoctadecadienoic acid

- TriHOME

- trihydroxyoctadecenoic acid

Manuscript received June 23, 2020, and in revised form August 25, 2020. Published, JLR Papers in Press, August 26, 2020, DOI 10.1194/jlr.RA120000991.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gladine C., Ostermann A. I., Newman J. W., and Schebb N. H.. 2019. MS-based targeted metabolomics of eicosanoids and other oxylipins: analytical and inter-individual variabilities. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 144: 72–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buczynski M. W., Dumlao D. S., and Dennis E. A.. 2009. An integrated omics analysis of eicosanoid biology. J. Lipid Res. 50: 1015–1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schebb N. H., Ostermann A. I., Yang J., Hammock B. D., Hahn A., and Schuchardt J. P.. 2014. Comparison of the effects of long-chain omega-3 fatty acid supplementation on plasma levels of free and esterified oxylipins. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 113–115: 21–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shearer G. C., and Newman J. W.. 2009. Impact of circulating esterified eicosanoids and other oxylipins on endothelial function. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 11: 403–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gladine C., Newman J. W., Durand T., Pedersen T. L., Galano J. M., Demougeot C., Berdeaux O., Pujos-Guillot E., Mazur A., and Comte B.. 2014. Lipid profiling following intake of the omega 3 fatty acid DHA identifies the peroxidized metabolites F4-neuroprostanes as the best predictors of atherosclerosis prevention. PLoS One. 9: e89393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tourdot B. E., Ahmed I., and Holinstat M.. 2014. The emerging role of oxylipins in thrombosis and diabetes. Front. Pharmacol. 4: 176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McGiff J. C., and Quilley J.. 1999. 20-HETE and the kidney: resolution of old problems and new beginnings. Am. J. Physiol. 277: R607–R623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Calder P. C., and Grimble R. F.. 2002. Polyunsaturated fatty acids, inflammation and immunity. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 56(Suppl 3): S14–S19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lopategi A., Lopez-Vicario C., Alcaraz-Quiles J., Garcia-Alonso V., Rius B., Titos E., and Claria J.. 2016. Role of bioactive lipid mediators in obese adipose tissue inflammation and endocrine dysfunction. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 419: 44–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burla B., Arita M., Arita M., Bendt A. K., Cazenave-Gassiot A., Dennis E. A., Ekroos K., Han X., Ikeda K., Liebisch G., et al. . 2018. MS-based lipidomics of human blood plasma: a community-initiated position paper to develop accepted guidelines. J. Lipid Res. 59: 2001–2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liakh I., Pakiet A., Sledzinski T., and Mika A.. 2019. Modern methods of sample preparation for the analysis of oxylipins in biological samples. Molecules. 24: 1639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rund K. M., Ostermann A. I., Kutzner L., Galano J. M., Oger C., Vigor C., Wecklein S., Seiwert N., Durand T., and Schebb N. H.. 2018. Development of an LC-ESI(-)-MS/MS method for the simultaneous quantification of 35 isoprostanes and isofurans derived from the major n3- and n6-PUFAs. Anal. Chim. Acta. 1037: 63–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kutzner L., Rund K. M., Ostermann A. I., Hartung N. M., Galano J. M., Balas L., Durand T., Balzer M. S., David S., and Schebb N. H.. 2019. Development of an optimized LC-MS method for the detection of specialized pro-resolving mediators in biological samples. Front. Pharmacol. 10: 169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dalli J., Colas R. A., Walker M. E., and Serhan C. N.. 2018. Lipid mediator metabolomics via LC-MS/MS profiling and analysis. Methods Mol. Biol. 1730: 59–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kortz L., Dorow J., Becker S., Thiery J., and Ceglarek U.. 2013. Fast liquid chromatography-quadrupole linear ion trap-mass spectrometry analysis of polyunsaturated fatty acids and eicosanoids in human plasma. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 927: 209–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang X., Yang N., Ai D., and Zhu Y.. 2015. Systematic metabolomic analysis of eicosanoids after omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation by a highly specific liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry-based method. J. Proteome Res. 14: 1843–1853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Quehenberger O., Dahlberg-Wright S., Jiang J., Armando A. M., and Dennis E. A.. 2018. Quantitative determination of esterified eicosanoids and related oxygenated metabolites after base hydrolysis. J. Lipid Res. 59: 2436–2445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ostermann A. I., Koch E., Rund K. M., Kutzner L., Mainka M., and Schebb N. H.. 2020. Targeting esterified oxylipins by LC-MS - effect of sample preparation on oxylipin pattern. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 146: 106384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang J., Schmelzer K., Georgi K., and Hammock B. D.. 2009. Quantitative profiling method for oxylipin metabolome by liquid chromatography electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 81: 8085–8093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Astarita G., McKenzie J. H., Wang B., Strassburg K., Doneanu A., Johnson J., Baker A., Hankemeier T., Murphy J., Vreeken R. J., et al. . 2014. A protective lipidomic biosignature associated with a balanced omega-6/omega-3 ratio in fat-1 transgenic mice. PLoS One. 9: e96221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ostermann A. I., Willenberg I., and Schebb N. H.. 2015. Comparison of sample preparation methods for the quantitative analysis of eicosanoids and other oxylipins in plasma by means of LC-MS/MS. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 407: 1403–1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hartung N. M., Mainka M., Kampschulte N., Ostermann A. I., and Schebb N. H.. 2019. A strategy for validating concentrations of oxylipin standards for external calibration. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 141: 22–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ostermann A. I., and Schebb N. H.. 2017. Effects of omega-3 fatty acid supplementation on the pattern of oxylipins: a short review about the modulation of hydroxy-, dihydroxy-, and epoxy-fatty acids. Food Funct. 8: 2355–2367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vesper H. W., Myers G. L., and Miller W. G.. 2016. Current practices and challenges in the standardization and harmonization of clinical laboratory tests. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 104 (Suppl. 3): 907S–912S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Siskos A. P., Jain P., Romisch-Margl W., Bennett M., Achaintre D., Asad Y., Marney L., Richardson L., Koulman A., Griffin J. L., et al. . 2017. Interlaboratory reproducibility of a targeted metabolomics platform for analysis of human serum and plasma. Anal. Chem. 89: 656–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bowden J. A., Heckert A., Ulmer C. Z., Jones C. M., Koelmel J. P., Abdullah L., Ahonen L., Alnouti Y., Armando A. M., Asara J. M., et al. . 2017. Harmonizing lipidomics: NIST interlaboratory comparison exercise for lipidomics using SRM 1950-Metabolites in Frozen Human Plasma. J. Lipid Res. 58: 2275–2288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Triebl A., Burla B., Selvalatchmanan J., Oh J., Tan S. H., Chan M. Y., Mellet N. A., Meikle P. J., Torta F., and Wenk M. R.. 2020. Shared reference materials harmonize lipidomics across MS-based detection platforms and laboratories. J. Lipid Res. 61: 105–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ribbenstedt A., Ziarrusta H., and Benskin J. P.. 2018. Development, characterization and comparisons of targeted and non-targeted metabolomics methods. PLoS One. 13: e0207082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gomolka B., Siegert E., Blossey K., Schunck W. H., Rothe M., and Weylandt K. H.. 2011. Analysis of omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acid-derived lipid metabolite formation in human and mouse blood samples. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 94: 81–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koch E., Mainka M., Dalle C., Ostermann A. I., Rund K. M., Kutzner L., Froehlich L. F., Bertrand-Michel J., Gladine C., and Schebb N. H.. 2020. Stability of oxylipins during plasma generation and long-term storage. Talanta. 217: 121074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bergstrand M., and Karlsson M. O.. 2009. Handling data below the limit of quantification in mixed effect models. AAPS J. 11: 371–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.EMA 2011. European Medicines Agency: Guideline on bioanalytical method validation EMEA/CHMP/EWP/192217/2009 Rev. 1 Corr. 2.Available from https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-bioanalytical-method-validation_en.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 33.US Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER), Center for Veterinary Medicine (CVM) 2018. Bioanalytical Method Validation: Guidance for Industry. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/files/drugs/published/Bioanalytical-Method-Validation-Guidance-for-Industry.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 34.Percy A. J., Tamura-Wells J., Albar J. P., Aloria K., Amirkhani A., Araujo G. D. T., Arizmendi J. M., Blanco F. J., Canals F., Cho J. Y., et al. . 2015. Inter-laboratory evaluation of instrument platforms and experimental workflows for quantitative accuracy and reproducibility assessment. EuPA Open Proteom. 8: 6–15. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mead J. F. 1980. Membrane lipid-peroxidation and its prevention. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 57: 393–397. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu G. S., Stein R. A., and Mead J. F.. 1977. Autoxidation of fatty-acid monolayers adsorbed on silica gel: II. Rates and products. Lipids. 12: 971–978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reinicke M., Dorow J., Bischof K., Leyh J., Bechmann I., and Ceglarek U.. 2020. Tissue pretreatment for LC-MS/MS analysis of PUFA and eicosanoid distribution in mouse brain and liver. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 412: 2211–2223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bowden J. A., Heckert A., Ulmer C. Z., Jones C. M., and Pugh R. S.. 2017. NISTIR 8185. Lipid concentrations in Standard Reference Material (SRM) 1950: results from an interlaboratory comparison exercise for lipidomics. Available from: https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/ir/2017/NIST.IR.8185.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Norris P. C., Skulas-Ray A. C., Riley I., Richter C. K., Kris-Etherton P. M., Jensen G. L., Serhan C. N., and Maddipati K. R.. 2018. Identification of specialized pro-resolving mediator clusters from healthy adults after intravenous low-dose endotoxin and omega-3 supplementation: a methodological validation. Sci. Rep. 8: 18050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Greupner T., Kutzner L., Nolte F., Strangmann A., Kohrs H., Hahn A., Schebb N. H., and Schuchardt J. P.. 2018. Effects of a 12-week high-alpha-linolenic acid intervention on EPA and DHA concentrations in red blood cells and plasma oxylipin pattern in subjects with a low EPA and DHA status. Food Funct. 9: 1587–1600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Keenan A. H., Pedersen T. L., Fillaus K., Larson M. K., Shearer G. C., and Newman J. W.. 2012. Basal omega-3 fatty acid status affects fatty acid and oxylipin responses to high-dose n3-HUFA in healthy volunteers. J. Lipid Res. 53: 1662–1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schuchardt J. P., Schmidt S., Kressel G., Willenberg I., Hammock B. D., Hahn A., and Schebb N. H.. 2014. Modulation of blood oxylipin levels by long-chain omega-3 fatty acid supplementation in hyper- and normolipidemic men. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids. 90: 27–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Quehenberger O., Armando A. M., Brown A. H., Milne S. B., Myers D. S., Merrill A. H., Bandyopadhyay S., Jones K. N., Kelly S., Shaner R. L., et al. . 2010. Lipidomics reveals a remarkable diversity of lipids in human plasma. J. Lipid Res. 51: 3299–3305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.CCQM 2013. CCQM Guidance note: Estimation of a consensus KCRV and associated degrees of equivalence. Version 10. Available from: https://www.bipm.org/cc/CCQM/Allowed/19/CCQM13-22_Consensus_KCRV_v10.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arita M. 2012. Mediator lipidomics in acute inflammation and resolution. J. Biochem. 152: 313–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Roberts L. D., Souza A. L., Gerszten R. E., and Clish C. B.. 2012. Targeted metabolomics. Curr. Protoc. Mol. Biol. Chapter 30: Unit 30.2.1-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Willenberg I., Rund K., Rong S., Shushakova N., Gueler F., and Schebb N. H.. 2016. Characterization of changes in plasma and tissue oxylipin levels in LPS and CLP induced murine sepsis. Inflamm. Res. 65: 133–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ostermann A. I., Waindok P., Schmidt M. J., Chiu C. Y., Smyl C., Rohwer N., Weylandt K. H., and Schebb N. H.. 2017. Modulation of the endogenous omega-3 fatty acid and oxylipin profile in vivo-A comparison of the fat-1 transgenic mouse with C57BL/6 wildtype mice on an omega-3 fatty acid enriched diet. PLoS One. 12: e0184470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data are contained within the article or supplemental data.