Abstract

The application of haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) with mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) infusion as a treatment regimen for severe aplastic anemia (SAA) has been reported to be efficacious in single-arm trials. However, it is difficult to assess without comparing the results with those from a first-line, matched-sibling HSCT. Herein, we retrospectively reviewed 91 patients with acquired SAA. They received HSCT from haploidentical donors combined with MSC transfer (HID group). We compared these patients with 103 others who received first-line matched-sibling HSCT (MSD group) to evaluate relative treatment efficacy. Compared with the patients in the MSD group, those in the HID group presented with higher incidences of grades II–IV and III–IV acute graft versus host disease (aGvHD) and chronic graft versus host disease (cGvHD) (p < 0.05). However, the incidence of myeloid and platelet engraftment, graft failure, poor graft function, and extensive cGvHD were comparable for both groups. The median follow-up was 36.6 months and the 3-year overall survival rate was similar for both groups (83.5% versus 79.1%). Univariate and multivariate analyses revealed that time intervals greater than 4 months from diagnosis to transplantation, experienced graft failure, poor graft function, or grade III–IV aGvHD were significantly associated with adverse outcomes. All HID patients received MSC co-transplantation with hematopoietic stem cells. However, the infused MSCs were derived from umbilical cord (UC-MSC group; 43 patients) or bone marrow (BM-MSC group; 48 patients) and were administered at different medical centers. We first compared the outcomes between the two groups and detected that the BM-MSC group exhibited lower incidences of grade III–IV aGvHD and cGvHD (p < 0.05). This study suggests that co-transplantation of hematopoietic and MSCs significantly reduces the risk and incidence of graft rejection and may effectively improve overall survival in patients with SAA even in the absence of closely related histocompatible donor material.

Keywords: co-transplantation, haploidentical HSCT, mesenchymal stem cells

Introduction

Aplastic anemia (AA) is pancytopenia with hypocellular bone marrow in the absence of abnormal infiltrate or marrow fibrosis.1 Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) from human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-matched siblings is a first-line and potentially curative treatment for young patients with severe aplastic anemia (SAA).2 Haploidentical HSCT has been considered as an alternative and possibly curative treatment for SAA patients without sibling donors who fail to respond to immunosuppressive therapy (IST).3–5 However, haplo-HSCT as a treatment for SAA is associated with high graft failure and incidence of graft versus host disease (GvHD).3,6,7 Previous reports3,5 revealed that the incidences of grade II–IV acute graft versus host disease (aGvHD) and chronic graft versus host disease (cGvHD) ranged from 33.7% to 42.1% and 22.4% to 56.2%, respectively; while overall survival (OS) ranged from 64.6% to 89%.

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are pluripotent, non-hematopoietic progenitors that may support hematopoiesis, enhance HSCT engraftment, and reduce the incidence of GvHD.8–10 Thus, MSCs are highly promising for use in haplo-HSCT. In previous studies, MSCs were co-transplanted with hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) in an attempt to improve haplo-HSCT efficacy. Wu et al.11 co-transplanted umbilical cord MSCs into 21 juveniles with SAA who had undergone haplo-HSCT. All patients sustained hematopoietic engraftment. The rates of grade II–IV aGvHD and cGvHD were 42.8% and 50%, respectively. The probability of 2-year disease and progression-free survival was 74.1%. Elsewhere, we previously reported 44 SAA patients who had undergone bone marrow-derived MSC co-transplantation during the haplo-HSCT procedure. We presented lower incidences of grade II–IV aGvHD (29.3%) and cGvHD (14.6%), with an overall survival rate of 77.3% during a median 12-month follow-up period.4

MSC co-transplantation during the haplo-HSCT procedure was efficacious and exhibited good rates of hematopoietic engraftment, an acceptable incidence of GvHD, and comparable OS. However, it is difficult to make an objective assessment in the absence of a reference standard such as Matched Sibling Donor (MSD)-HSCT. Furthermore, MSCs derived from different tissues may generate variable clinical outcomes. To the best of our knowledge, however, no such comparisons have been published to date. Thus, in the current study we collected data from 91 patients who received both haploidentical donor (HID)-HSCT and MSC infusion, including 43 patients using umbilical cord-MSCs from the First Affiliated Chinese PLA General Hospital and 48 patients using bone marrow-derived MSCs from our alternative centers including five hospitals. We also collected data from 103 SAA patients receiving HSCT from HLA-matched sibling donors, from 10 hospitals, and compared the efficacy of HID-HSCT co-transplantation with that of matched sibling donor (MSD)-HSCT to assess objectively the value of the co-transplantation model. We then compared the clinical outcomes from patients administered MSCs from umbilical cords with those who received bone marrow-derived MSCs.

Materials and methods

Patients

The present study included 103 transplant recipients from HLA-identical siblings and 91 transplant recipients from haploidentical family donors between March 2009 and March 2019. The patients were selected from 10 transplant hospitals across China and met the following inclusion criteria: (a) they presented with symptoms of aplastic anemia (SAA) or very severe aplastic anemia (VSAA) as defined in the 2016 Edition of Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of adult aplastic anemia;1 (b) age range was 2–56 years; (c) HLA-identical sibling donors for MSD-HSCT; (d) HLA-mismatched related family donors with ⩾5/10 HLA-matched loci for HID-HSCT; (e) no serious infection or acute hemorrhage; (f) presented with left ventricular ejection fractions >50%; (g) transaminase and serum creatinine levels were ⩽2× the upper normal limit; (h) no acute contagious diseases; (i) understood and were willing to sign a written informed consent document; and (j) were assigned Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group scores in the range of 0–2 points. HLA compatibility was established using high-resolution DNA techniques for HLA-A, B, C, DRB1, and DQB1 loci. Donors were ranked according to HLA match, age (younger preferred), gender (same preferred), and health status (better preferred). The HID-HSCT procedure was chosen on the basis of a lack of response to a previous IST, insufficient time to search for a matched unrelated donor due to high disease severity, limited financial resources to cover IST and HID-HSCT, and/or patient preference. Before treatment choices were made and informed written consent was obtained from all patients, they were advised in detail of all currently available treatment options including their benefits and risks. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the General Hospital of Guangzhou Military Command [approval number: (2014) Lunshenzi no. 001]. All patients were followed until the end of the evaluation period on 17 November 2019.

Conditioning regimen

Patients who underwent MSD-HSCT were placed on regimens including CY/antithymocyte globulin (ATG) or Flu/CY/ATG. These consisted of cyclophosphamide (CY; 50 mg kg–1 once daily for 4 consecutive days on days ‒5 to ‒2), ATG (rabbit, Genzyme Polyclonals S.A.S, Lyon, France; 2.5–3.75 mg kg–1 once daily on days ‒5 to ‒2) and fludarabine (Flu; 30 mg kg–1 d–1 on days ‒5 to ‒2). Patients who underwent HID-HSCT were placed on regimens consisting of alternate Flu/CY/ATG and BU/CY/ATG treatments. The latter consisted of busulfan (BU) 3.2 mg kg–1 once daily for 2 days, on days ‒7 and ‒6, CY 50 mg kg–1 once daily for 4 consecutive days on days ‒5 to ‒2, and ATG 3 mg kg–1 once daily on days ‒5 to ‒2.

GvHD prophylaxis

Acute GvHD prophylaxis for MSD-HSCT comprised ciclosporin A (CsA) and short-term methotrexate (MTX). For HID-HSCT, the aGvHD prophylaxis consisted of CsA, short-term MTX, and mycophenolate mofetil (MMF). CsA was administered intravenously at 2.5 mg kg–1 d–1 twice daily from day ‒7 until bowel function returned to normal. Thence, the patients were administered oral CsA. A target trough blood concentration of 200–250 ng mL–1 was maintained for ⩾9 months after HSCT and gradually tapered off until the CsA was withdrawn completely over the next 2–3 months. MTX was administered intravenously at 15 mg m–2 on day +1 and at 10 mg m–2 on days +3, +6, and +11. MMF was administered orally (0.5 g every 12 h; 0.25 g for children) from days −9 to +30. Thereafter, it was administered at 0.25 g from days +30 to +90. When GvHD occurred, CsA and MMF were maintained and their doses were adjusted to therapeutic concentrations.

Stem cell harvest

Bone marrow and hematopoietic stem cell mobilization and collection are described in detail in a previous report.4 Target densities for mononuclear cells (MNCs) from bone marrow and peripheral blood and CD34+ cells were ⩾5 × 108 kg−1 and ⩾2 × 106 kg−1 recipient weight, respectively, at day 0 of the recipient cycle. The first and second days of stem cell infusion were designated day ‘01’ and day ‘02’, respectively.

MSC preparation and transfusion

Umbilical cord derived (UC)-MSCs were cultured and supplied by the National Engineering Research Center of Cell Products, State Key Laboratory of Experimental Hematology. Each patient received UC-MSCs from a single donor. Patients received the UC-MSCs 4 h before stem cell transfusion on day 01. Bone marrow derived (BM)-MSCs were cultured and supplied by the Center for Cell Therapy and Research of the General Hospital of Guangzhou Military Command. MSCs were cultured, expanded, and transfused as previously described.4 The target density for the UC-MSCs and BM-MSCs was 3–5 × 105 kg−1. All patients were monitored for vital signs and allergic symptoms during MSC transfusion.

Definition and evaluation of engraftment and chimerism

Myeloid engraftment, complete donor chimerism, and primary and late graft failure (GF) were defined in a previous report.4 Poor graft function (PGF) is cytopenia in ⩾2 hematopoietic lines (neutrophil count <1.5 × 109 L–1, platelet count <30 × 109 L–1, and hemoglobin (Hb) <8.5 g dL–1) for ⩾2 consecutive weeks beyond day +14 following documented engraftment in the presence of full donor chimerism, the absence of severe GvHD, CMV reactivation, relapse or drug-related myelosuppression, and hypocellular bone marrow.12 The incidence and severity of GvHD were evaluated according to a National Institutes of Health (NIH) consensus conference on the determination of GvHD grade.13 Cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection and pneumonia were defined according to the literature.14,15 Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) infection and EBV-associated post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders (PTLD) were defined in previous reports.16,17

Infection prevention and supportive care

The prevention of infection and supportive care were administrated as described in a previous report.4

Statistical analysis

Patients who died before engraftment were excluded from the acute and chronic GvHD analyses. Patients who survived for >100 days were analyzed for cGvHD. The incidences of acute and chronic GvHD were evaluated by Kaplan–Meier estimation. To compare the MSD and HID groups, Mann–Whitney U and χ2 tests were used, respectively. OS was determined by Kaplan–Meier estimation and the log-rank test. Associations between the independent variables and OS were analyzed by Cox regression. For the multivariate analysis, the forced factors at p < 0.2 in the univariate analysis were evaluated by the Cox regression model. Factors were considered independent outcome predictors when significant associations (p < 0.05) were found. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics v. 20 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The two-tailed significance level was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Characteristics of the patients and their treatments

SAA patients undergoing MSD-HSCT (103) and HID-HSCT (91) were enrolled in the study. Clinical characteristics were compared between groups (Table 1). Age distribution, previous treatments, and graft type were significantly different between the groups (p < 0.05). Patient gender did not significantly differ between groups (p > 0.05). In the HID group, there were more patients <20 years, and with more serious disease status (VSAA) than the MSD group (p < 0.05). The time intervals from diagnosis to transplantation were longer in the HID group than the MSD group (p < 0.05).

Table 1.

Characteristics of SAA patients and their donors for HSCT (n = 194).

| Variable | MSD group (n = 103) | HID group (n = 91) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at transplant, n (%) | 0.000* | ||

| ⩽20 years | 24 (23.3) | 51 (56.0) | |

| 20–40 years | 62 (60.2) | 33 (36.3) | |

| ⩾40 years | 17 (16.5) | 7 (7.7) | |

| Age at transplant, year, median (range) | |||

| ⩽20 years | 16 (6~20) | 13 (2~20) | 0.013* |

| 20–40 years | 28 (20~38) | 28 (21~39) | 0.950 |

| ⩾40 years | 46 (40~56) | 44 (40~47) | 0.131 |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.863 | ||

| Male | 61 (59.2) | 55 (60.4) | |

| Female | 42 (40.8) | 36 (39.6) | |

| Disease and status at transplantation, n (%) | 0.048* | ||

| SAA | 70 (68.0) | 46 (50.5) | |

| VSAA | 30 (29.1) | 41 (45.1) | |

| SAA-PNH | 3 (2.9) | 4 (4.4) | |

| History of hepatitis B virus infection, n (%) | 11 (10.7) | 5 (5.5) | 0.296 |

| Previous treatments, n (%) | 0.009* | ||

| CsA ± andriol/stanozole ± corticosteroid ± others | 74 (71.8) | 71 (78.0) | |

| ATG ± CsA ± corticosteroid±andriol | 2 (1.9) | 9 (9.9) | |

| Supportive treatment | 24 (23.3) | 11 (12.1) | |

| Others | 3 (2.9) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Intervals from diagnosis to transplantation, n (%) | 0.02* | ||

| ⩽4 months | 70 (68.0) | 47 (51.6) | |

| >4 months | 33 (32.0) | 44 (48.4) | |

| Donor-recipient sex match, n (%) | 0.001* | ||

| Male to male | 27 (26.2) | 38 (41.8) | |

| Male to female | 29 (28.2) | 15 (16.5) | |

| Female to male | 33 (32.0) | 13 (14.3) | |

| Female to female | 14 (13.6) | 25 (27.4) | |

| Blood types of donor to recipient, n (%) | 0.066 | ||

| Matched | 56 (54.4) | 59 (64.8) | |

| Major mismatched | 11 (10.7) | 9 (9.9) | |

| Minor mismatched | 8 (7.8) | 16 (17.6) | |

| Major and minor | 23 (22.3) | 7 (7.7) | |

| Unclear | 5 (4.8) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Conditioning regimen, n (%) | 0.000* | ||

| Flu/Cy/ATG | 30 (29.1) | 23 (25.3) | |

| Cy/ATG | 63 (61.2) | 2 (2.2) | |

| Bu/Cy/ATG | 9 (8.7) | 58 (63.7) | |

| Flu/Bu/Cy/ATG | 1 (1.0) | 8 (8.8) | |

| Graft types | 0.000* | ||

| BM | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| PB | 41 (39.8) | 6 (6.6) | |

| BM+PB | 61 (59.2) | 85 (93.4) | |

| Stem cells | |||

| MNC, ×108/kg, median (range) | 10.6(1.3–33.3) | 11.2 (5.6–25.1) | 0.374 |

| CD34+ cells, ×106/kg, median (range) | 6.0 (1.1–17.7) | 5.2 (0.5–16.9) | 0.105 |

| MSCs/dose, ×105/kg, median (range) | 0.084 | ||

| UC-MSCs | —— | 4.6 (2.9–7.1) | |

| BM-MSCs | —— | 4.2 (3.2–5.7) | |

| Follow-up of alive patients, months, median (range) | 44.1 (3.3–129.5) | 28.6 (3.0–118.3) | 0.000* |

ATG, antithymocyte globulin; BM, bone marrow; Bu, busulfan; CsA, ciclosporin; Cy, cyclophosphamide; Flu, fludarabine; HID, haplo-identical donor; HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; MNC, mononuclear cell; MSCs, mesenchymal stem cells; MSD, matched sibling donor; PNH, paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria; SAA, severe aplastic anemia; UC, umbilical cord; VSAA, very severe aplastic anemia.

statistical difference (P<0.05).

Engraftment

Primary graft failure occurred in four MSD patients (3.9%) and two HID patients (2.2%). Ninety-eight MSD patients (95.1%) and 88 HID patients (96.7%) survived for >28 days. All 98 MSD patients presented with myeloid engraftment and full donor chimerism. In the HID group, only one out of the 88 patients failed to achieve myeloid engraftment. The 28-day cumulative incidences of myeloid engraftment in both groups were 100% and 98.9%, respectively. The median times for myeloid engraftment were 13 days (range 8–24 days) and 12 days (range 8–21 days), respectively. Ninety-five MSD patients (96.9%) presented with platelet engraftment within a median of 17 days (range 7–41 days). Eighty-seven HID patients (98.9%) achieved platelet engraftment within a median of 16 days (range 8–154 days). For the MSD group, five patients (5.1%) experienced late GF and nine patients (9.2%) presented with PGF. For the HID group, three (3.4%) and seven (7.7%) patients presented with late GF and PGF, respectively. No significant differences were observed between groups in terms of primary GF, late GF, median myeloid and platelet engraftment time, or PGF (p > 0.05; Table 2). Of the five MSD patients experiencing late GF, one underwent a second HSCT and achieved hematological remission, one had hemogram recovery after donor leukocyte infusion (DLI), two survived despite illness, and one died. In the HID group, two patients presenting with late GF underwent a second HSCT using different haploidentical donors and achieved hematological remission. One patient survived despite illness.

Table 2.

Clinical outcomes between MSD group and HID group.

| Variable | MSD group (103) | HID group (91) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary GF, n (%) | 4/103 (3.9) | 2/91 (2.2) | 0.686 |

| Patients survived for more than 28 days, n (%) | 98/103 (95.1) | 88/91 (96.7) | 0.725 |

| Incidence of engraftment, n (%) | |||

| Incidence of myeloid engraftment | 98 /98 (100) | 87/88 (98.9) | 0.469 |

| Incidence of platelet engraftment | 95/98 (96.9) | 87/88 (98.9) | 0.624 |

| Neutrophil engraftment, days, median (range) | 13 (8–24) | 12 (8–21) | 0.107 |

| Platelet engraftment, days, median (range) | 17 (7–41) | 16 (8–154) | 0.643 |

| Late GF and PGF, n (%) | |||

| Late GF | 5/98 (5.1) | 3/88 (3.4) | 0.724 |

| PGF | 9/98 (9.2) | 7/88 (7.9) | 0.401 |

| Acute GvHD | 10/98 (10.2) | 46/88 (52.3) | 0.000* |

| Grade II–IV, n (%) | 5/98 (5.1) | 25/88 (28.4) | 0.000* |

| Grade III–IV, n (%) | 0/98 (0) | 10/88 (11.4) | 0.001* |

| Patients survived longer than 100 days, n (%) | 92/98 (93.9) | 82/88 (96.6) | 1.000 |

| Chronic GvHD | 5/92 (5.4) | 22/82 (26.8) | 0.000* |

| Extensive cGvHD | 1/92 (1.1) | 5/82 (6.1) | 0.052 |

| Viremia | |||

| CMV | 43/103 (41.7) | 48/91 (52.7) | 0.150 |

| EBV | 26/103 (25.2) | 26/91 (28.6) | 0.629 |

| EBV-associated PTLD | 4/103 (3.9) | 5/91 (5.5) | 0.423 |

| Overall survival, n (%) | 86/103 (83.5) | 72/91 (79.1) | 0.397 |

| ⩽20 years | 22/24 (91.7) | 42/51 (82.4) | 0.272 |

| 20–40 years | 51/62 (82.3) | 25/33 (75.8) | 0.472 |

| ⩾40 years | 14/17 (82.4) | 5/7 (71.4) | 0.487 |

CMV, cytomegalovirus; EBV, Epstein–Barr virus; GF, graft failure; GvHD, graft versus host disease; HID, haplo-identical donor; MSD, matched sibling donor; PGF, poor graft function; PTLD, post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders.

statistical difference (P<0.05).

Severity of GvHD

Table 2 shows the incidence and severity of GvHD for the MSD and HID groups.

Acute graft versus host disease

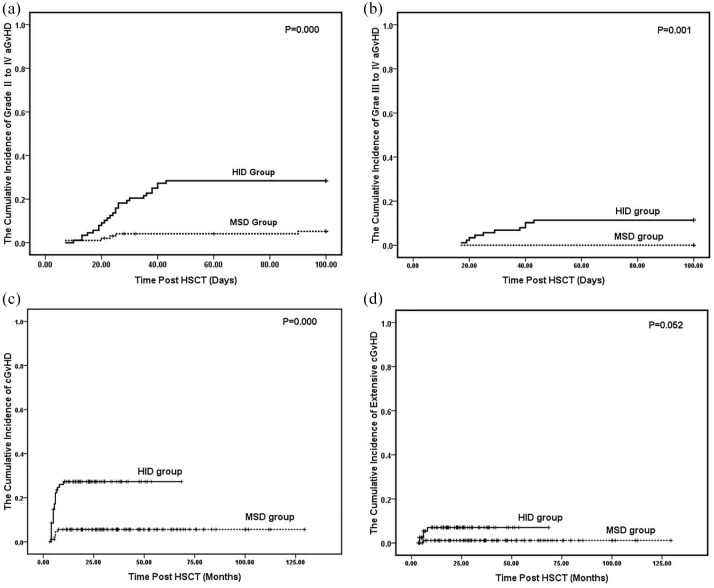

Of the 98 MSD patients, 10 (10.2%) experienced aGvHD after transplantation. These included five (5.1%) with grade I, five (5.1%) with grade II, and none (0%) with grade III or grade IV. In the HID group, 46 (52.3%) presented with post-transplantation aGvHD including 21 (23.9%) with grade I, 15 (17.0%) with grade II, eight (9.1%) with grade III, and two (2.3%) with grade IV. At 100 days post-transplantation, the cumulative incidences of grades II–IV aGvHD for the MSD and HID groups were 5.1% and 28.4%, respectively (p = 0.000; Figure 1A). The cumulative incidences of grades III–IV aGvHD in the MSD and HID groups were 0% and 11.4%, respectively (p = 0.001; Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

The Kaplan–Meier curves for the cumulative incidences of GvHD for the MSD group and HID group. A shows grade II–IV aGvHD. B shows grade III–IV aGvHD. C shows cGvHD and D shows extensive cGvHD.

aGvHD, acute graft versus host disease; cGvHD, chronic graft versus host disease; GvHD, graft versus host disease; HID, haploidentical donor; MSD, matched sibling donor.

Chronic graft versus host disease

Ninety-two MSD patients and 82 HID patients who survived for >100 days were assessed for cGvHD. In the MSD group, only five patients (5.4%) presented with cGvHD after transplantation. Twenty-two patients (26.8%) experienced cGvHD in the HID group. There was a significant difference between groups (p = 0.000; Table 2; Figure 1C). However, only one (1.1%) and five (6.1%) patients in the MSD and HID groups, respectively, exhibited extensive cGvHD. No significant difference were observed between the groups (P = 0.052; Table 2; Figure 1D).

CMV reactivation

Forty-three out of 103 patients (41.7%) in the MSD group experienced CMV reactivation detected by antigen or DNA testing. The average time of onset was 34 days (range 8–90 days) and the average duration was 22 days after HSCT. In the HID group, 48 out of 91 patients (52.7%) presented with CMV reactivation. The average time of onset was 36 days (range 16–120 days) and the average duration was 36 days after HSCT. There was no significant difference in CMV reactivation between the groups (p > 0.05; Table 2). In the MSD group, one patient progressed to CMV-associated pneumonia and succumbed to respiratory failure. In the HID group, five patients were confirmed to have CMV-associated bladder cystitis and three presented with CMV-associated enteritis. Most patients with post-HSCT CMV reactivation completely recovered following antiviral therapy. However, five and three patients with CMV reactivation in the MSD and HID groups, respectively, eventually succumbed to non-CMV related causes.

EBV reactivation

Twenty-six out of 103 patients (25.2%) experienced EBV reactivation in the MSD group as detected by antigen or DNA testing. The average time of onset was 37 days (range 18–159 days) and the average duration was 29 days after HSCT. In the HID group, 26 out of 91 patients (28.6%) presented with EBV reactivation. The average time of onset was 38 days (range 13–150 days) and the average duration was 45 days after HSCT. Four patients (3.9%) in the MSD group and five (5.5%) in the HID group progressed to EBV-associated post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder (PTLD). There were no significant differences in EBV reactivation or EBV-associated PTLD between the groups (p > 0.05; Table 2). Viral infections were treated with ganciclovir or foscarnet and γ-globulin. All patients with PTLD received rituximab (Mabthera; Roche Pharma AG, Reinach, Switzerland). Most of the PTLD-free patients recovered fully. Three MSD and two HID patients with PTLD died. One patient in the MSD group and three patients in the HID group recovered from PTLD. They presented with enlarged lymph nodes which disappeared over time and their numbers of copies of EBV declined to normal. However, one patient in the HID group died of septic shock at day +325 after HSCT.

Regimen-related toxicity

All patients received the conditioning regimen on schedule. No patients in the HID group experienced infusion-related toxicity while receiving MSCs. Most regimen-related toxicities (RRTs) were mild or moderate. One patient with cerebral hemorrhage and one with acute renal failure in the MSD group died of RRT on day +4 and day +7, respectively. No patients in the HID group died of RRT. Six MSD patients (5.8%) and 25 HID patients (27.5%) presented with hemorrhagic cystitis. The incidence of hemorrhagic cystitis in the HID group was significantly higher than that of the MSD group (p = 0.000). All patients with hemorrhagic cystitis recovered within 2–3 weeks after hydration, urinary alkalization, and bladder flushing.

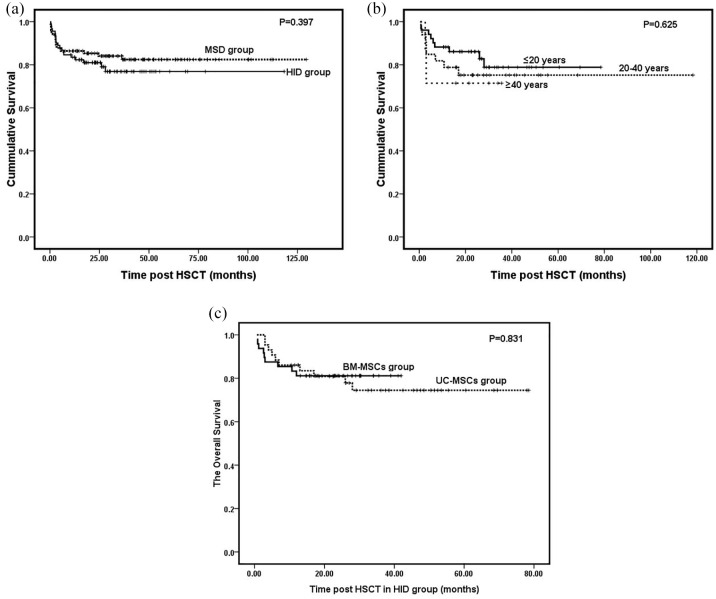

Overall survival and transplant-related mortality

With a median follow-up of 36.6 months (range 3.0–129.5) for the MSD group, five patients died before engraftment and 12 died within the follow-up period. Three patients died before engraftment and 16 died within the follow-up period in the HID group. The 3 year OS was 83.5% for the MSD group and 79.1% for the HID group but it did not differ significantly (p = 0.397; Table 2; Figure 2A). The age subgroups in MSD and HID did not differ significantly in terms of OS (p > 0.05; Table 2). For the HID group, OS gradually declined with age (82.4% versus 75.8% versus 71.4%). However, the age groups did not differ significantlyin terms of OS (p = 0.625; Figure 2B). Univariate analysis showed significant differences in survival among patients with longer time intervals (⩾4 months) from diagnosis to transplantation (p = 0.188), GF (p = 0.000), PGF (p = 0.071), and grade III–IV aGvHD (p = 0.006). Multivariate analysis disclosed that all four factors were significantly associated with adverse outcomes (p < 0.05; Table 3). Severe infection was the primary cause of death. In the MSD group, 13 patients died of infection. Eight presented with severe pneumonia, two with septicemia, and three with EBV-associated PTLD. For the HID group, 16 patients succumbed to infection. Ten had severe pneumonia, three had septicemia, two had EBV-associated PTLD, and one had CMV-associated enteritis. The other causes of transplant-related mortality (TRM) in the MSD group included RRT in two patients and one case each of acute myocardial infarction and late GF. For the HID group, the other causes of TRM included one case each of severe intestinal GvHD, primary GF, and thrombotic microangiopathy.

Figure 2.

The cumulative survival curves. A shows the total survival curves of the MSD group and HID group. B shows the survival curves of different age groups in the HID group. C shows the survival curves of patients with MSCs derived from bone marrow or umbilical cord in the HID group.

HID, haploidentical donor; MSCs, mesenchymal stem cells; MSD, matched sibling donor.

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of adverse factors associated with overall survival (Cox regression).

| Univariate analysis |

Multivariate analysis |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | HR (95% CI) | p value | HR (95% CI) | p value |

| Identical group | 1.315 (0.683–2.533) | 0.412 | – | – |

| MSD group | ||||

| HID group | ||||

| Age group | 1.499 (0.737–3.047) | 0.264 | – | – |

| ⩽20 years | ||||

| >20 years | ||||

| Intervals from diagnosis to HSCT | 0.621 (0.305–1.262) | 0.188* | 0.443 (0.211–0.931) | 0.032* |

| ⩽4 months | ||||

| >4 months | ||||

| GF | 4.935 (2.155–11.302) | 0.000* | 8.282 (3.402–20.160) | 0.000* |

| No | ||||

| Yes | ||||

| PGF | 2.246 (0.934–5.399) | 0.071* | 3.370 (1.332–8.528) | 0.010* |

| No | ||||

| Yes | ||||

| Grade II–IV aGvHD | 1.452 (0.662–3.187) | 0.352 | – | – |

| No | ||||

| Yes | ||||

| Grade III–IV aGvHD | 3.446 (1.434–8.282) | 0.006* | 4.261 (1.730–10.493) | 0.002* |

| No | ||||

| Yes | ||||

| cGvHD | 1.041 (0.433–2.504) | 0.929 | – | – |

| No | ||||

| Yes | ||||

CI, confidence interval; GF, graft failure; GvHD, graft versus host disease; HID, haplo-identical donor; HR, hazard ratio; MSD, matched sibling donor; PGF, poor graft function; SCT, stem cell transplantation.

statistical difference (P<0.05).

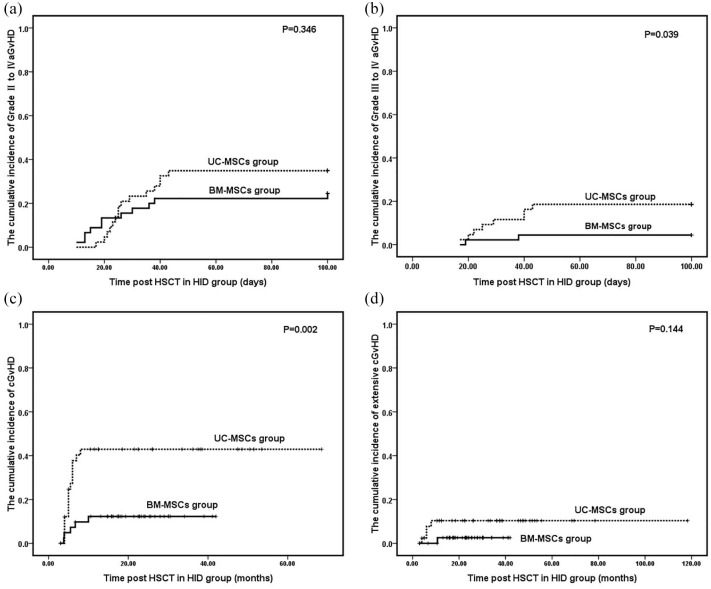

Comparison of patients with MSCs derived from bone marrow and umbilical cord

There were no significant differences between MSD and HID groups in terms of myeloid and platelet engraftment, median time of myeloid and platelet engraftment, and incidences of primary and late GF and PGF (p > 0.05; Table 4). No differences were detected between the groups in terms of grade II–IV aGvHD and extensive cGvHD (p > 0.05; Table 4; Figure 3A and D). However, the incidences of grades III–IV aGvHD and cGvHD in the UC-MSC group were significantly higher than those of the BM-MSC group (p < 0.05; Table 4, Figure 3B and C). No differences were observed between groups in terms of the incidences of EBV reactivation and EBV-associated PTLD (p > 0.05; Table 4). However, the patients in the BM-MSC group presented with a higher incidence of CMV reactivation than those in the UC-MSC group (p = 0.006; Table 4). The 2-year OS was 76.7% for the UC-MSC group and 81.2% for the BM-MSC group (Table 4; Figure 2C). No significant difference was identified between groups in terms of 2-year OS (p = 0.831; Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparison between UC-MSC group and BM-MSC group.

| Variable | UC-MSC group (43) | BM-MSC group (48) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary GF, n (%) | 0/43 (0) | 2/48 (4.2) | 0.496 |

| Late GF, n (%) | 3/43 (7.0) | 0/48 (0) | 0.102 |

| PGF, n (%) | 5/43 (11.6) | 2/48 (4.2) | 0.249 |

| Patients survived for more than 28 days, n (%) | 43/43 (100) | 45/48 (93.8) | |

| Incidence of engraftment, n (%) | |||

| Incidence of myeloid engraftment | 43/43 (100) | 44/45 (97.8) | 0.496 |

| Incidence of platelet engraftment | 43/43 (100) | 44/45 (97.8) | 0.496 |

| Neutrophil engraftment, days, median (range) | 12 (8–21) | 12 (8–20) | 0.464 |

| Platelet engraftment, days, median (range) | 14 (9–26) | 18 (8–154) | 0.194 |

| aGvHD | |||

| Grade II–IV, n (%) | 15/43 (34.9) | 11/45 (24.4) | 0.346 |

| Grade III–IV, n (%) | 8/43 (18.6) | 2/45 (4.4) | 0.039* |

| Patients survived longer than 100 days, n (%) | 43/43 (100) | 42/48 (87.5) | 0.000* |

| cGvHD | 17/43 (39.5) | 5/42 (11.9) | 0.002* |

| Extensive cGvHD | 4/43 (9.3) | 1 (2.4) | 0.144 |

| Viremia | |||

| CMV | 16/43 (37.2) | 32/48 (66.7) | 0.006* |

| EBV | 8/43 (18.6) | 18/48 (37.5) | 0.063 |

| EBV-associated PTLD | 0/43 (0) | 5/48 (10.4) | 0.058 |

| Overall survival, n (%) | 33/43 (76.7) | 39/48 (81.2) | 0.831 |

BM, bone marrow; CMV, cytomegalovirus; EBV, Epstein–Barr virus; GF, graft failure; GvHD, graft versus host disease; MSCs, mesenchymal stem cells; PGF, poor graft function; PTLD, post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders; UC, umbilical cord.

statistical difference (P<0.05).

Figure 3.

The Kaplan–Meier curves for the cumulative incidences of GvHD for the UC-MSC group and BM-MSC group in the HID group. A shows the grade II–IV aGvHD. B shows the grade III–IV aGvHD. C shows the cGvHD and D shows the extensive cGvHD.

aGvHD, acute graft versus host disease; BM-MSC, bone marrow-mesenchymal stem cell; cGvHD, chronic graft versus host disease; GvHD, graft versus host disease; HID, haploidentical donor; MSD, matched sibling donor; UC-MSC, umbilical cord-mesenchymal stem cell.

Discussion

Previous studies showed favorable survival outcomes with acceptable engraftment and GvHD for haploidentical HSCT co-transplanted with MSCs for SAA treatment.4,9,11 However, confirmation of the positive effects elicited by MSC co-transplantation with HID-HSCT was difficult to attain as no control was used and no comparison made with standard MSD-HSCT. In the present study, we collected data from 10 medical centers to compare therapeutic outcomes between HID-HSCT with MSC co-transplantation and MSD-HSCT for SAA therapy. The age groups differed significantly in terms of the type of transplants they received. Most of the MSD transplant recipients were in the 20–40-year age range whereas those in the HID group were primarily <20 years. In the latter case, the median age was 13 years whereas for the <20 years age subgroup of the MSD patients it was 16 years. Younger patients lacking histocompatible sibling donors were more inclined to opt for HID-HSCT than MSD-HSCT as they were more likely than the older patients to have parents who were young enough to be suitable donors. This conclusion corroborates with that of a previous study.5 Thus, the age effect is a major survival predictor.18,19 We analyzed OS for various age subgroups in the HID group and found that patients <20 years had the highest survival rate (82.4%). This discovery was consistent with an earlier study indicating that OS significantly increased with decreasing age in haplo-HSCT.19

In the HID group, most patients (87.9%) did not receive HSCT before IST failure. Therefore, HID patients had relatively longer time intervals from diagnosis to transplantation than MSD patients. ATG plus CsA comprises a well-known standard immunosuppressive therapy. However, only two patients (1.9%) in the MSD group and nine (9.9%) in the HID group chose ATG therapy. This treatment is very expensive in China and may not reduce the risk of recurrence. Most patients received CsA alone before transplantation. This practice was consistent with those reported by other domestic centers.3,20

Graft failure (GF) is a serious complication of allogeneic HSCT. Its incidence in patients with non-malignant hematological diseases is 3× higher than in patients with malignant blood disorders.21 GF is often observed after allogeneic transplants for SAA treatment.22 Grafts obtained from matched unrelated and mismatched donors are more likely to fail than those acquired from HLA-matched siblings.23,24 However, in the present study, the incidence of GF was lower in the HID than the MSD group. The incidences of primary and late GF for the MSD group were 3.9% and 5.1%, respectively. In the HID group, they were 2.2% and 3.4%, respectively. Moreover, the incidences of myeloid and platelet engraftment in the HID group were comparable with those for the MSD group.

The observed relative improvement of engraftment may be explained by an intensified conditioning regimen with busulfan (BU) which lowers the risk of rejection.5,25 Additional MSC grafts may also help improve engraftment. For animal models wherein MSC co-transplantation with HSCs improved engraftment, it is presumed that MSCs contributed to hematopoiesis.26,27 Noort et al. demonstrated that co-infusion of fetal lung-derived MSCs and umbilical cord blood (UCB )-derived CD34+ cells in nonobese diabetic/severe combined immunodeficient (NOD/SCID) mice was associated with enhanced human HSC engraftment in mouse bone marrow (BM) especially when the HSCs were infused at relatively low doses.26 Previous studies demonstrated the feasibility and safety of clinical HSC and MSC co-transplantation and its facilitation of HSC engraftment.9,28–31 In HLA-haploidentical allografts, MSCs may lower the risk of GF by modulating host alloreactivity and/or enhancing the engraftment of donor hematopoiesis.32,33 Ball et al.33 co-transplanted donor MSCs with HSCs in 14 children undergoing haploidentical HSCT. The GF rate in the historical controls was 15%. In contrast, all 14 patients presented with sustained hematopoietic engraftment and no adverse reactions. Thus, MSCs may reduce the risk of GF in haploidentical HSCT.

GvHD is another major challenge in HID-HSCT for SAA. For HID-HSCT administered under various schedules, the incidence of aGvHD (⩾grade II) ranged from 12% to 42% and that for cGvHD ranged from 20% to 56%.3,34–36 MSCs have immunoregulatory properties and may modulate immune responses against alloantigens. Preliminary results also indicated that they may be safe and efficacious for GvHD prevention or treatment.4,37–39 Thus, we administered MSCs with HID-HSCT expecting that the combination would reduce the incidence of GvHD. In the present study, the incidence of grade II–IV aGvHD was 28.4% and that of grade III–IV aGvHD was 11.4%. The incidence of cGvHD was 26.8% and that of extensive cGvHD was 6.1%. The incidences of aGvHD (>grade II) and cGvHD in the HID group were significantly higher than those for the MSD group. Nevertheless, they were more closely comparable here than they were in previous studies.4,37–39

In a previous study, high incidences of EBV (31.8%) and CMV (65.9%) reactivation were observed.4 In the present study, we compared the incidences of EBV and CMV reactivation in the HID and MSD groups. No significant differences were observed between the HID and MSD groups in terms of EBV or CMV reactivation and EBV-associated PTLD. In the HID group, however, the patients receiving BM-MSCs exhibited a higher incidence of CMV reactivation than those administered UC-MSCs (p = 0.006).

Herein, OS in the HID group was 79.1% and was comparable with that for the MSD group (83.5%; p > 0.05). This finding is consistent with that of Xu et al.5 That study showed that survival was comparable for patients receiving MSD-HSCT and those administered HID-HSCT. In this study, we analyzed OS for various age groups and found that younger patients (<20 years) had better OS than older patients (91.7% for the MSD group versus 82.4% for the HID group). This discovery aligned with that reported by Kojima et al.40 The latter authors analyzed the factors influencing OS in 154 patients with SAA who had received HSCT from unrelated donors. Patient age >20 years was an unfavorable factor. According to Xu et al.,5 patients receiving HID-HSCT had a better OS (89%) than those in the present study. One possible explanation is that the average age of their patients (19 years) was lower than those in the present study. Earlier reports identified other factors affecting OS including transplantation >3 years after diagnosis, preconditioning regimen without antithymocyte globulin, HLA-A or HLA-B locus mismatching as determined by DNA typing, and grade III–IV aGvHD.5,40 Here, we found that patients with longer intervals from diagnosis to transplantation (⩾4 months) before HSCT, presented with GF, PGF, or grade III–IV aGvHD after HSCT and all of these were significantly associated with adverse outcomes.

For the HID group, we evaluated the effects of various tissue sources of MSCs on the haplo-HSCT outcomes. Patients receiving BM-MSCs had lower incidences of grade III–IV aGvHD, cGvHD, and CMV reactivation (p < 0.05) than those administered umbilical cord-derived MSCs (UC-MSCs). No significant differences were observed between these subgroups in terms of GF, PGF, engraftment, grade II–IV aGvHD, extensive cGvHD, EBV reactivation, or OS. It was reported that MSCs derived from various tissue sources have different biological characteristics. BM-MSCs have relatively lower proliferative capacity, whereas UC-MSCs have comparatively higher proliferation potency.41 Moreover, a gene expression analysis of BM-MSCs and UC-MSCs indicated that the genes associated with osteogenic differentiation were upregulated in the former, whereas those involved in angiogenesis were upregulated in the latter.42 In this study, engraftment was similar for both groups. This observation corroborates that of a previous report in which BM-MSCs and UC-MSCs supported hematopoiesis.26,27,29,31,43 The fact that the incidences of grade III–IV aGvHD and cGvHD were lower in the BM-MSC than the UC-MSC group indicates that the former treatment is a stronger immunosuppressant than the latter.44,45 This finding also explains why the CMV and EBV reactivations were greater in the BM-MSC than the UC-MSC group. However, the differences between UC-MSCs and BM-MSCs have not been studied clearly, and more basic research is needed to clarify the functional differences between them in the future.

The present study had several limitations. Certain flaws are inherent in retrospective studies. Firstly, the HID group had a relatively short follow-up time as the haploidentical HSCT was initiated late. Secondly, the patient baselines were not matched between the groups, most notably in terms of disease status and previous treatments at the time of transplantation and the time intervals from diagnosis to transplantation. Thirdly, this study was directly head to head in its procedures when we evaluated the various MSC sources. Moreover, a prospective, head-to-head study should be performed to obtain more credible results. Basic studies examining the biological characteristics of MSCs from different tissue sources with an emphasis on deciphering the mechanisms responsible for the differences in promoting hematopoietic implantation and suppressing immunorejection also require further investigation.

The present retrospective, multi-center study revealed that the outcomes for HID-HSCT with MSC infusion are encouraging and are associated with high rates of engraftment and survival. Although the incidence of GvHD in the HID group was higher than that in the MSD group, it was nonetheless acceptable. The efficacy of MSC co-transplantation with HID-HSCT is potentially comparable with that of MSD-HSCT for SAA patients lacking matched sibling donors and failing to respond to IST.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Editage for the language editing provided for this manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by funding from the National Natural Science Foundations of China (project no. 81903973, project no. 81570107, and project no. 81873426), the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (project no. 2014A030311006), Guangdong Traditional Chinese Medicine Bureau (project no. 20202064), and the Youth Research Fund Project of the Innovation to Strengthen Hospital Project of the First Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (project no. 2019QN03).

ORCID iD: Yang Xiao  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0046-4967

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0046-4967

Contributor Information

Zenghui Liu, Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine; The First Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine, Guangzhou, China; General Hospital of Guangzhou Military Command, Guangzhou, China.

Xiaoxiong Wu, First Affiliated Hospital of PLA General Hospital, Beijing, China.

Shunqing Wang, Guangzhou First People’s Hospital, Guangzhou, China.

Linghui Xia, Union Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China.

Haowen Xiao, General Hospital of Guangzhou Military Command, Guangzhou, China.

Yonghua Li, General Hospital of Guangzhou Military Command, Guangzhou, China.

Hongbo Li, The First Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine, Guangzhou, China.

Yuping Zhang, Guangzhou First People’s Hospital, Guangzhou, China.

Duorong Xu, First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-Sen University, Guangzhou, China.

Danian Nie, Second Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-Sen University, Guangzhou, China.

Yongrong Lai, First Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University, Nanning, China.

Bingyi Wu, Affiliated Zhujiang Hospital of Southern Medical University, Guangzhou, China.

Dongjun Lin, Third Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-Sen University, Guangzhou, China.

Xin Du, Shenzhen Second People’s Hospital, Shenzhen, China.

Zujun Jiang, General Hospital of Guangzhou Military Command, Guangzhou, China.

Yang Gao, General Hospital of Guangzhou Military Command, Guangzhou, China.

Xuekui Gu, Department of Hematology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine, No 16, Jichang Road, Guangzhou, Guangdong Province, 510405, PR China.

Yang Xiao, Stem Cell Translational Medicine Center, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University, No. 250, Changgang East Road, Guangzhou, Guangdong Province, 510260, PR China.

References

- 1. Killick SB, Bown N, Cavenagh J, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of adult aplastic anaemia. Br J Haematol 2016; 172: 187–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Young NS, Bacigalupo A, Marsh JC. Aplastic anemia: pathophysiology and treatment. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2010; 16: 119–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Xu LP, Liu KY, Liu DH, et al. A novel protocol for haploidentical hematopoietic SCT without in vitro T-cell depletion in the treatment of severe acquired aplastic anemia. Bone Marrow Transplant 2012; 47: 1507–1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Liu Z, Zhang Y, Xiao H, et al. Cotransplantation of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in patients with severe aplastic anemia: an interim summary for a multicenter phase II trial results. Bone Marrow Transplant 2017; 52: 704–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Xu LP, Wang SQ, Wu DP, et al. Haplo-identical transplantation for acquired severe aplastic anaemia in a multicentre prospective study. Br J Haematol 2016; 175: 265–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Woodard P, Cunningham JM, Benaim E, et al. Effective donor lymphohematopoietic reconstitution after haploidentical CD34+-selected hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in children with refractory severe aplastic anemia. Bone Marrow Transplant 2004; 33: 411–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lacerda JF, Martins C, Carmo JA, et al. Haploidentical stem cell transplantation with purified CD34+ cells after a chemotherapy-alone conditioning regimen in heavily transfused severe aplastic anemia. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2005; 11: 399–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Guo M, Sun Z, Sun QY, et al. A modified haploidentical nonmyeloablative transplantation without T cell depletion for high-risk acute leukemia: successful engraftment and mild GVHD. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2009; 15: 930–937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lazarus HM, Koc ON, Devine SM, et al. Cotransplantation of HLA-identical sibling culture-expanded mesenchymal stem cells and hematopoietic stem cells in hematologic malignancy patients. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2005; 11: 389–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dazzi F, Ramasamy R, Glennie S, et al. The role of mesenchymal stem cells in haemopoiesis. Blood Rev 2006; 20: 161–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wu Y, Cao Y, Li X, et al. Cotransplantation of haploidentical hematopoietic and umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells for severe aplastic anemia: successful engraftment and mild GVHD. Stem Cell Res 2014; 12: 132–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Alchalby H, Yunus DR, Zabelina T, et al. Incidence and risk factors of poor graft function after allogeneic stem cell transplantation for myelofibrosis. Bone Marrow Transplant 2016; 51: 1223–1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cho BS, Min CK, Eom KS, et al. Feasibility of NIH consensus criteria for chronic graft versus host disease. Leukemia 2009; 23: 78–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Luo XH, Chang YJ, Huo MR, et al. Cytomegalovirus-specific T cells immune reconstitution after human leukocyte antigen matched sibling donor allogeneic bone marrow plus peripheral blood hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Zhonghua Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi 2012; 33: 605–609. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ljungman P, Boeckh M, Hirsch HH, et al. Definitions of cytomegalovirus infection and disease in transplant recipients. Clin Infect Dis 2002; 34: 1094–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Han TT, Xu LP, Liu DH, et al. Prevalence of EBV infection in patients with allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Zhonghua Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi 2013; 34: 651–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Styczynski J, Reusser P, Einsele H, et al. Management of HSV, VZV and EBV infections in patients with hematological malignancies and after SCT: guidelines from the Second European Conference on Infections in Leukemia. Bone Marrow Transplant 2009; 43: 757–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gupta V, Eapen M, Brazauskas R, et al. Impact of age on outcomes after bone marrow transplantation for acquired aplastic anemia using HLA-matched sibling donors. Haematologica 2010; 95: 2119–2125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kim H, Lee JH, Joo YD, et al. Comparable allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation outcome of a haplo-identical family donor with an alternative donor in adult aplastic anemia. Acta Haematol 2016; 136: 129–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Xu LP, Jin S, Wang SQ, et al. Upfront haploidentical transplant for acquired severe aplastic anemia: registry-based comparison with matched related transplant. J Hematol Oncol 2017; 10: 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Olsson R, Remberger M, Schaffer M, et al. Graft failure in the modern era of allogeneic hematopoietic SCT. Bone Marrow Transplant 2013; 48: 537–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Storb R, Thomas ED, Buckner CD, et al. Marrow transplantation for aplastic anemia. Semin Hematol 1984; 21: 27–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mattsson J, Ringdén O, Storb R. Graft failure after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2008; 14: 165–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cluzeau T, Lambert J, Raus N, et al. Risk factors and outcome of graft failure after HLA matched and mismatched unrelated donor hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a study on behalf of SFGM-TC and SFHI. Bone Marrow Transplant 2016; 51: 687–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dulley FL, Vigorito AC, Aranha FJ, et al. Addition of low-dose busulfan to cyclophosphamide in aplastic anemia patients prior to allogeneic bone marrow transplantation to reduce rejection. Bone Marrow Transplant 2004; 33: 9–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Noort WA, Kruisselbrink AB, in’t Anker PS, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells promote engraftment of human umbilical cord blood-derived CD34(+) cells in NOD/SCID mice. Exp Hematol 2002; 30: 870–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bensidhoum M, Chapel A, Francois S, et al. Homing of in vitro expanded Stro-1− or Stro-1+ human mesenchymal stem cells into the NOD/SCID mouse and their role in supporting human CD34 cell engraftment. Blood 2004; 103: 3313–3319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Koç ON, Gerson SL, Cooper BW, et al. Rapid hematopoietic recovery after coinfusion of autologous-blood stem cells and culture-expanded marrow mesenchymal stem cells in advanced breast cancer patients receiving high-dose chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 2000; 18: 307–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Macmillan ML, Blazar BR, DeFor TE, et al. Transplantation of ex-vivo culture-expanded parental haploidentical mesenchymal stem cells to promote engraftment in pediatric recipients of unrelated donor umbilical cord blood: results of a phase I-II clinical trial. Bone Marrow Transplant 2009; 43: 447–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gonzalo-Daganzo R, Regidor C, Martín-Donaire T, et al. Results of a pilot study on the use of third-party donor mesenchymal stromal cells in cord blood transplantation in adults. Cytotherapy 2009; 11: 278–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wu Y, Wang Z, Cao Y, et al. Cotransplantation of haploidentical hematopoietic and umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells with a myeloablative regimen for refractory/relapsed hematologic malignancy. Ann Hematol 2013: 92: 1675–1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. `Bernardo ME, Ball LM, Cometa AM, et al. Co-infusion of ex vivo-expanded, parental MSCs prevents life-threatening acute GVHD, but does not reduce the risk of graft failure in pediatric patients undergoing allogeneic umbilical cord blood transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 2011; 46: 200–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ball LM, Bernardo ME, Roelofs H, et al. Cotransplantation of ex vivo expanded mesenchymal stem cells accelerates lymphocyte recovery and may reduce the risk of graft failure in haploidentical hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. Blood 2007; 110: 2764–2767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gao L, Li Y, Zhang Y, et al. Long-term outcome of HLA-haploidentical hematopoietic SCT without in vitro T-cell depletion for adult severe aplastic anemia after modified conditioning and supportive therapy. Bone Marrow Transplant 2014; 49: 519–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wang Z, Zheng X, Yan H, et al. Good outcome of haploidentical hematopoietic SCT as a salvage therapy in children and adolescents with acquired severe aplastic anemia. Bone Marrow Transplant 2014; 49: 1481–1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Esteves I, Bonfim C, Pasquini R, et al. Haploidentical BMT and post-transplant Cy for severe aplastic anemia: a multicenter retrospective study. Bone Marrow Transplant 2015; 50: 685–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Le Blanc K, Rasmusson I, Sundberg B, et al. Treatment of severe acute graft versus host disease with third party haploidentical mesenchymal stem cells. Lancet 2004; 363: 1439–1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ringdén O, Uzunel M, Rasmusson I, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells for treatment of therapy-resistant graft versus host disease. Transplantation 2006; 81: 1390–1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Le Blanc K, Frassoni F, Ball L, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells for treatment of steroid-resistant, severe, acute graft versus host disease: a phase II study. Lancet 2008; 371: 1579–1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kojima S, Matsuyama T, Kato S, et al. Outcome of 154 patients with severe aplastic anemia who received transplants from unrelated donors: the Japan Marrow Donor Program. Blood 2002; 100: 799–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kern S, Eichler H, Stoeve J, et al. Comparative analysis of mesenchymal stem cells from bone marrow, umbilical cord blood, or adipose tissue. Stem Cells 2006; 24: 1294–1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Panepucci RA, Siufi JL, Silva WA, Jr, et al. Comparison of gene expression of umbilical cord vein and bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells 2004; 22: 1263–1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Friedman R, Betancur M, Boissel L, et al. Umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells: adjuvants for human cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2007; 13: 1477–1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Heo JS, Choi Y, Kim HS, et al. Comparison of molecular profiles of human mesenchymal stem cells derived from bone marrow, umbilical cord blood, placenta and adipose tissue. Int J Mol Med 2016; 37: 115–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Karaöz E, Çetinalp Demircan P, Erman G, et al. Comparative analyses of immunosuppressive characteristics of bone-marrow, Wharton’s jelly, and adipose tissue-derived human mesenchymal stem cells. Turk J Haematol 2017; 34: 213–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]