Individualized development plans (IDPs) are tools designed to support persons in identifying professional goals and strategies to achieve these goals. Currently, IDPs are used across all of the Ruth L. Kirschstein Institutional National Research Service Awards (T32) funded by the National Institute for Nursing Research (NINR). While several organizations, including the National Institutes of Health (NIH), have strongly encouraged the use of IDPs to support identification and achievement of learning and career development goals, limited information is available on how to best implement these tools in research training. The purpose of this paper is to present an experiential discussion of NINR-funded T32 programs to identify initial best practices for use of IDPs in the mentoring and development of pre- and postdoctoral trainees, emphasizing the role of the IDP in provision of feedback and advancing the training and career development of nurse scientists.

The Individual Development Plan and Its Purpose Within Nursing Science

The IDP is a planning roadmap customized to a pre- or postdoctoral trainee’s needs and goals and their emergent program of research. The overarching purpose of the IDP within the context of nursing science is to support learning and career development by assuring achievement of the essential competencies required for a productive career as a nurse scientist, as well as the trainee’s individualized goals during their PhD and/or postdoctoral program. Moreover, the IDP is a way to prepare trainees to realize their identified career aspirations and to foster communication and reflection between the trainee and mentor (National Institutes of Health [NIH], 2014). The IDP process generally includes self-assessment and reflection; identification of career goals and areas for professional growth; establishment of specific short- and long-term goals; and statements of general strategies and specific tactics for realizing these goals (Vanderford, Evans, Weiss, Bira, & Betran-Gastelum, 2018).

History of IDP Use With Pre- and Postdoctoral Trainees

Government and private-sector employers have long utilized IDPs to assist employees to identify their abilities, goals, and needed skills; maximize their work performance; navigate their career; and advance their employer’s enterprise (Austin & Alberts, 2012; Cohen, 2003). Application of IDPs to research career planning was developed and endorsed by the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology (Clifford, 2002; Gould, 2017), and subsequently recommended by the National Postdoctoral Association (2011) as a best practice to foster personal responsibility for career planning and active mentoring of postdoctoral scientists. This practice advanced in 2012 when a working group advised the NIH Director that, as part of developing and sustaining a capable and diverse research workforce, NIH should require the use of IDPs to structure the creation, evolution, and achievement of training and career goals for all postdoctoral scientists supported by NIH-funded training, career development, and research grants (NIH, 2012). Moreover, this working group proposed that operationalization of this requirement should be considered when evaluating training grants. The NIH implemented this advice in 2013 by “strongly encouraging” grantee institutions to develop policies that necessitate the use of IDPs for all graduate students and postdoctoral scientists supported by NIH funds (NIH, 2013). The following year, NIH mandated that annual research performance progress reports (RPPR) to the NIH describe whether, and if so, how, IDPs were being used at the institution to guide research training and career development for trainees linked with the award (NIH, 2014).

Purpose of the Individual Development Plan

Individual development plans are multipurpose, pertinent to trainees, to mentors, and to research training programs in general. IDPs support trainees to (1) achieve synergy with the tripartite mission of scholarship, namely, research, teaching, and service (Gillespie et al., 2018); (2) identify and pursue career aspirations (Vanderford et al., 2018); and (3) develop realistic trajectories for their careers and priorities for their various scholarly endeavors along the way (Gillespie et al., 2018). The quality and quantity of mentoring and mentors within and across programs varies enormously, which influences trainee perspectives on possible career trajectories and paths (Cohen, 2003). IDPs address some of this variability in mentoring by helping mentors achieve best practice through structured guidance and documentation of their trainees’ self-assessments, goals, and strategies and tactics for achieving these goals. Program-level goals that IDPs can assist in achieving include assurance of mentor engagement in research training. IDPs provide a device through which progression and accomplishments of trainees can be monitored and summarized. They also enable identification of areas requiring early intervention such as the need for additional mentors or potential mismatches between trainees and mentors.

Federal and foundation sponsors encourage the use of IDPs to achieve more structured training experiences across trainees and across programs and to improve placements of graduates by promoting accountability through required reporting. From the NIH’s perspective, requiring information about the use of IDPs at the institution in annual progress reports for training grants, career awards, and research awards serves as an incentive for awardees to assure carefully planned education and training that meets the unique goals of the trainee. In this way, this tool improves the likelihood of high-quality outcomes and placements for trainees following completion of funded training programs (NIH, 2014).

IDP Use and Components Across NINR-Funded T32s

Survey Methods and Analysis

The issue of mentoring and IDP use was raised at a national meeting of T32 program directors with NINR program staff during the 2018 Council for the Advancement of Nursing Science Meeting. In follow-up to this discussion, the current program directors for the 21 NINR-funded Ruth L. Kirschstein Institutional National Research Service Awards (T32s) completed a collectively developed survey in March 2019 about the use of IDPs in our pre- and postdoctoral training programs. In addition to survey questions, we elicited narrative data using two open-ended questions: “What benefits (if any) do you experience with using IDPs?” and “What challenges (if any) do you experience with using IDPs?” In addition, we requested a copy or template of the IDPs currently used by these T32s training programs. As the survey was used to gather experiential information for discussion, and was not research, IRB approval was not sought.

We summarized the survey responses using simple descriptive statistics. Six of the authors independently reviewed the responses to the two open-ended questions. Then, these authors discussed their results to achieve agreement. Three of the authors independently reviewed the submitted IDP templates to identify specific components included in the IDPs, identified commonalities and differences in the components, compared their reviews, and came to consensus on the findings.

Survey Results

A total of 16 individual survey responses were received (N= 16). These responses represented all 21 NINR-funded T32s across 15 Schools or Colleges of Nursing (referred to hereafter as schools); some of these institutions have more than one NINR-funded T32 and thus, in some cases, one response to the survey was sent for multiple T32s. All respondents reported using IDPs with T32 predoctoral trainees and 14 reported using the IDPs with T32 postdoctoral trainees (of note, not all NINR-funded T32s have postdoctoral trainee positions). Respondents reported using IDPs at their school with pre (n = 7) and postdoctoral (n = 4) trainees not affiliated with their T32. A few respondents reported using IDPs with junior faculty (n = 4) or other persons (n = 1) at their school. One-half of the respondents indicated that they integrated T32 program-specific competencies into their IDPs. Nine respondents used the IDP to formally collect trainee-level outcome data, five used the IDP to informally collect these data, and two did not use the IDP in this manner. Eight respondents used the IDP to formally collect program-level outcome data, five used the IDP to informally collect these data, and three did not use the IDP for this purpose.

IDP Template Components

We received 15 IDP templates from 13 schools. The IDP templates differed from one another and appeared to meet multiple purposes, as well as have common components (Table 1). In terms of differing from one another, some IDP templates were used for annual reviews not only by the T32 but also by the school or the graduate school. Directors were not asked to submit instructions for template use. However, a few templates were submitted with complete instructions for use, including when the initial IDP would be completed and how often and by whom the document would be reviewed. For the majority of templates, it was clear that mentors were to assist the trainee in developing the IDP, particularly around goals and activities, or that they were to review the IDP and sign it. Some templates had a place where the trainee could list all dissertation committee or mentoring team members in addition to their T32 mentor. A few templates could be completed electronically with drop-down menus and other electronic features for updating or revising.

Table 1–

Components Included in IDPs of NINR-Funded T32 Programs

| Frequently Included Components (>50% of Program Templates) | Less Common Components | Unique Components |

|---|---|---|

| Self-assessment | Required coursework for the training program | Individualized course work |

| Goals (e.g., manuscripts, presentations, funding, career, training) | Socialization/professionalization | Personal interests |

| Strategies or activities (e.g., course work, conferences, mentored research experiences, networking) | Teaching skills and experience | Grants management training |

| Resources needed to achieve goals | Clinical competencies | |

| Timelines/completion checklists | Interpersonal skill development | |

| Training in working with interdisciplinary team | Opportunity to indicate why goals are important to the trainee | |

| Listing advisors/mentors, dissertation committees, or mentoring network | ||

| Training in ethical conduct of research |

Template organization varied greatly. Some templates were organized by term (semester, quarter, or academic year) and others by training goal. While some templates (n = 3) included a section about training in the responsible conduct of research, most did not. Some templates had trainees list specific grants or scholarships and timelines for these applications. Some templates asked trainees to list papers planned and/or submitted and presentations planned and/or completed. While some templates had areas specific for mentor comments and review; most did not.

Although they differed in appearance and perhaps intended use, the template components generally included a: (1) self-assessment; (2) short- and long-term professional and career goals; and (3) strategies to achieve these goals. About half of the IDPs required trainees to complete a self-assessment. While the template formats varied, many appeared to have been guided by the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) myIDP (https://myidp.sciencecareers.org/Overview/Summary). Broad self-assessment categories were used such as Scientific Knowledge, Research Skills, Communication, Teaching, and Professional Development. Specific skills to be assessed were included under each broad category. In some cases, scales were provided for trainees to rate their proficiency or ability. Two IDPs included an area for mentors to rate trainees on the same skills. Several templates included unique areas for self-assessment of skills particular to the T32 focus.

All but one template asked trainees to write goals for training and/or career development. Typically, these goals were to be created by the trainee. Two templates were prepopulated with common goals and strategies with trainees reporting their progress toward meeting those goals. Some templates had headers, for example “Research Skill Goal,” and then provided space for the trainee to specify goals or objectives in that area. A number of the templates accommodated both short- and long-term goals. Some had timeframes up to 5 years in length. Only two templates instructed the trainee to develop SMART goals (i.e., Specific, Measurable, Action oriented, Realistic, Time-bound).

Strategies to achieve targeted goals were required in all but one IDP. While strategies or activities were clearly individualized, many of the IDP templates provided guidance by including sections regarding completion of course work, research practicums/experiences, training in the responsible conduct of research, dissemination activities (presentations and publications), and other areas of professional development. Four of the IDPs incorporated identification of the resources needed for the trainee to be successful in carrying out the identified strategies.

Responses to Open-Ended Survey Questions

Of the 16 replies to the survey, all included responses to the open-ended questions about the benefits and challenges associated with IDP use and identified several themes in these data (Table 2). Benefits of IDP use included the following: (1) requires the trainee and the mentor to specify the trainee’s goals and exactly what the trainee needs to do to achieve those goals; (2) promotes trainee reflection, self-assessment, and accountability; and (3) promotes consistency in mentoring across trainees and communication among mentors, T32 directors, and/or PhD program directors. Some respondents wrote that their trainees benefited from the use of IDPs through peer review that provided motivation and helped trainees learn how to express their goals and to identify additional strategies for achieving them. As one respondent noted, the IDP “assists trainees with goal setting and the specifics on how to achieve those goals.” Another noted that before IDPs, “we used to experience inconsistencies (in mentoring) between students.”

Table 2–

Benefits and Challenges of IDP Use

| Benefits | Challenges |

|---|---|

| 1. Encourages self-assessment | 1. Requires education of both trainees and mentors |

| 2. Requires trainees to identify goals and the skills and resources needed to achieve them | 2. Takes time to establish and maintain |

| 3. Provides an individualized guide for training and evaluation of progress | 3. Relies on a culture that appreciates their value in supporting trainee success |

| 4. Increases consistency of mentoring across trainees | 4. Needs to integrate and align with other documentation required by the PhD program to avoid duplication |

| 5. Promotes accountability for both trainees and mentors | |

| 6. Serves as a data source regarding trainee productivity and other outcomes |

Challenges were also noted, including that meeting with trainees to create an initial IDP and then regularly to review and update is time consuming. Respondents reported the necessity to keep the IDP realistic, to provide trainees and faculty with instruction and support regarding the best ways to create and use an IDP, and to reorganize the IDP template to align with other documentation required by the overall PhD or postdoctoral training program. One T32 director indicated that “The IDP is meant [to be] a tool, not an outcome in itself and sometimes trainees focus on a great [looking] IDP, but it may not be realistic. Keeping it updated is important.” A further challenge identified by respondents was institutionally-based. It was suggested that as IDP use broadens within a school to trainees who are not supported by NIH funds despite their apparent effectiveness in promoting trainee success, such adoption can be tentative or encounter resistance. This challenge can be overcome by educating and fostering peers through the adoption process and clearly articulating the benefits associated with more IDP use. Further, it is suggested that data be explicitly gathered to demonstrate the effectiveness of IDPs on institutional and individual outcomes in order to strengthen the argument for return on investment. This should include trainee perspectives.

Reasons PhD and Postdoctoral Programs in Nursing Should Use IDPs

Clear benefits can result from comprehensive use of IDPs with all pre- and postdoctoral trainees. As noted above, the IDP promotes identifying goals, targeting benchmarks representing scholarly progress, determining mentoring and development needs, and monitoring of training and development activities and outcomes. These expected outcomes for NIH-funded trainees are the same for all PhD students and postdoctoral fellows. Thus, adoption of IDPs across PhD and postdoctoral programs will strengthen the education and training of the next generation of nurse scientists.

Schools often have departmental, programmatic, and/or institutional annual review procedures and policies for trainees. IDP use can serve as replacement for or a supplement to existing review procedures. The IDP’s focus on regular review of accomplishments in various areas like coursework, projects, proposals, qualifying and/or comprehensive examinations, dissertation progress, manuscripts, and presentations reflects achievements that can be celebrated or areas for which supportive plans and resources can be created. Establishment of specific goals with timeframes provides guidance and benchmarks to evaluate and monitor at levels beyond the individual trainee.

Recommendations for Best Practices for the Use of IDPs at the Trainee Level

We recommend that PhD and postdoctoral programs use IDPs as devices to increase communication, structure mentoring and annual review meetings, and promote accountability on the parts of both the mentor and the mentee. Pre- and postdoctoral trainees can use IDPs to assess their skills, goals, strengths, and limitations and to identify strategies and tactics to advance their knowledge and skills to achieve their education, training, and career goals. An IDP can help to identify strengths and gaps in trainee’s education and research-related experiences to ensure learning and achievement of program milestones (e.g., committee formation, proposal approval, grant submissions). The IDP self-assessment component should lead to the development of specific goals and a plan with specific activities to accomplish these goals. Using the IDP to assist trainees to reflect on and clarify their goals will help them to meet program expectations and keep on target to reach them. Documentation of progress toward goals provides data for ongoing trainee self-assessment and evaluation. For additional guidance on IDP use, trainees and mentors can refer to the AAAS’ tool http://myidp.sciencecareers.org/ and then have a collective discussion on self-assessment results in order to develop a meaningful and actionable IDP.

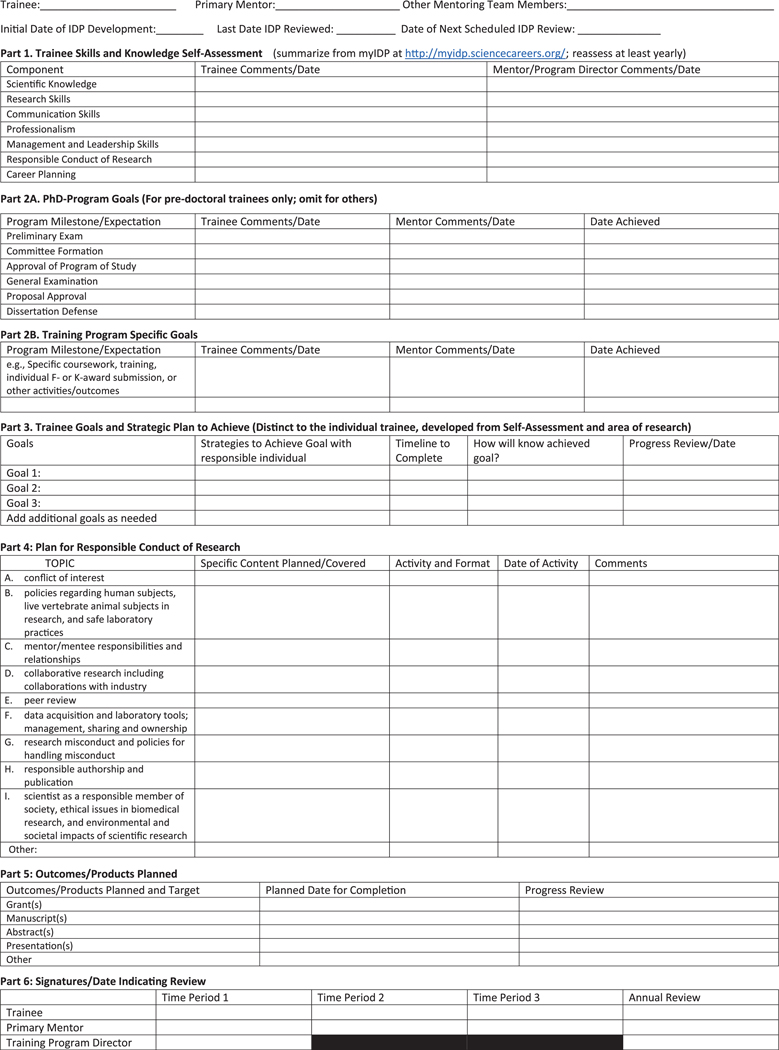

Best practice does not mandate a particular IDP format. Based on our analysis of templates from NINR-funded T32s, we developed a prototype IDP that can be adapted for use by programs training nurse scientists (Figure 1). Of note, our recommendations include a component about training in the responsible conduct of research given that this training is required for NIH National Research Service Awards to individuals (F31, F32) as well as to institutions (T32). In addition, we recommend that instructions be provided to trainees and mentors, including a statement that the IDP needs to be reviewed on a regularly scheduled basis by trainee, mentor, program director, and/or designated review panel. This prototype can be adapted as needed, with timeline for completion of the various components and review individualized to suit the program. The IDP is meant to be a dynamic document with the possibility to change or update as needed; as such, a collaborative document tool may be useful.

Figure 1–

Individual Development Plan Template Prototype for Adaptation for Nurse Scientist Training.

IDPs should be used for ongoing self-assessment as well as formal and informal mentoring. Examples of how trainees and faculty mentors achieve these activities are helpful in determining how to use an IDP. For example, one of the NINR-funded T32s requires all new trainees to complete a self-assessment across five domains: overall core scientific knowledge, general research skills, professional skills, leadership and management skills, and interpersonal skills. This assessment helps the trainee and the mentor focus on specific strengths and areas for growth. Goals are written in relationship to areas where growth is needed. Then the trainee and mentor strategically plan specific activities and experiences to meet these goals. In many cases, trainees have interdiscipinary mentoring teams, and the IDP can help mentors harmonize suggested training plan activities and clarify their specific roles in assisting the trainee.

Across T32s, initial IDPs are typically developed collaboratively between trainee and mentor and submitted to the T32 program director(s) during the first term of the program (quarter or semester). Mentors, and in some cases, peers use the self-assessment questions to rate the trainee at various times during the program, typically at least once a year and in some cases at the end of each term. Then, this rating is reviewed by the T32 and/or PhD program director at least on an annual basis. At the completion of the predoctoral or postdoctoral training program, a final progress report is reviewed by the mentors, directors, and in some cases, other advisory or oversight committees. Best practices for individual use and updating of IDPs include initial completion at program start, periodic evaluation (minimally annually), and evaluation at the completion of the training program. As individuals transition positions (from pre- to postdoctoral or postdoctoral to junior faculty), they may find it useful to provide a copy of their final updated IDP to their new mentor(s) in order to facilitate a more seamless development of skills and knowledge as a nurse scientist.

Developing Feedback Skills

Seeking, offering, and receiving feedback is an essential part of the research mentoring process. Not only is the IDP a planning document, it is a tool for stimulating regular exchanges about trainee progress, identifying mentoring, areas for ongoing growth and development, and outlining potential strategies for making additional progress. Some basic principles about effective, constructive feedback are that the advice should be: (1) focused on behaviors essential to achieve outcomes, not personal characteristics; (2) clear; and (3) timely. Such feedback is facilitated by IDP use in that most stipulate an agreed-upon set of behaviors, skills, and scholarly products, which provides a template to focus on outcomes, and not personality during the provision of feedback.

Another principle in offering effective feedback is to be clear and constructive in the messages being conveyed. IDPs tend to be detailed documents containing numerous goals and means for evaluation. Although a quick check on progress can be accomplished on most goals and behaviors, the person providing feedback should be clear about a few behaviors in which further improvement and/or alternative behavioral strategies are needed. This requires preparation about the key messages to be conveyed during a feedback session and clarity about why this particular feedback is being offered without interjecting personal motives and biases including those that might arise from generational gaps between mentees and mentors.

Last, feedback should be timely and not limited to the more formal IDP discussions at the end of the year or semester. Most IDPs include multiple research training goals, including program-specific goals, building research networks, finding collaborators, producing scholarly products, completing courses, acquiring research skills, and planning one’s career. Progress toward these distinct goals proceeds at different paces, which necessitates different intervals for evaluation and feedback. For example, feedback about presentation skills is best given soon after a presentation, when the experience is fresh in the trainee’s and the mentor’s minds.

IDP discussions between trainees and mentors can provide an opportunity for the trainee to offer the mentor feedback about the quality of mentorship and training processes. Posing the simple question “What specifically would you like more of and less of from me?” can be useful in eliciting feedback on one’s mentorship skills. Another question might be “How can we improve this learning experience for you?” Offering and receiving constructive feedback can greatly enhance the effectiveness of IDPs. These skills are essential to the mentoring process and learning to perform them well should not be left to chance. Quality mentored training programs include formal preparation in how to offer and receive feedback. This formal preparation can be completed at the program level for all trainees and the faculty who engage with them.

Best Practices for Use of IDPs at the Program Level

Programmatic Development and Evaluation of Mentoring

The IDP can be very useful as a resource for improving the training program overall. IDPs that include self and mentor assessments of trainees’ strengths and needs offer insights into common content or skills that require attention in the training program. Most IDPs require trainees to identify specific outcomes they will produce or achieve, with timelines for accomplishing these goals and regular updates on progress. This invaluable data enable faculty to synthesize the types of outcomes which trainees have success in achieving as a group (e.g., analysis and publication of secondary data) versus where they struggle to meet their goals (e.g., submitting an application for further research training; training in the responsible conduct of research). Then, additional systematic research training activities can be created at the program level to effectively target areas where, as a group, trainees require more support.

The quality of faculty mentorship across the program can be enhanced via use of IDPs that fosters consistency in key aspects of mentoring among all trainees. Some T32 Directors meet with each trainee on a regular basis to review progress on their IDPs and assess perceived adequacy of their mentorship on each IDP goal. These meetings provide important information for follow-up discussions with specific mentors about challenges they may be experiencing as mentors; advice on mentorship responsibilities and strategies; and additional support that may be needed for the mentor and/or for the trainee. This same approach can be used when a seasoned mentor is working with a less experienced mentor to nurture her/his mentorship skills. Faculty meetings or workshops at the program level can offer additional opportunities for mentors to discuss specific challenges or successes in helping a trainee address IDP goals. Mentors can learn from each other when grappling with difficult situations as a group and hearing about innovative strategies they can integrate into their own mentoring repertoire.

Another best practice is to engage in peer review of IDPs with the larger group of trainees. In this way, trainees can develop their emerging mentorship skills by contributing to another trainee’s growth. Peer review facilitates direct observation of the various ways in which faculty model mentorship approaches as IDPs are discussed.

Formal Program Assessment

For some schools, policies regarding IDPs are governed centrally. For example, one T32 program has a centralized postdoctoral office at the university level that sets policies for postdoctoral fellows (trainees) as well as postdoctoral associates (research staff). The office has developed IDP forms in a fillable pdf format that must be used by all postdoctoral fellows and associates. Having a common form allows benchmarking of research training programs across the university. A similar form can be developed for predoctoral trainees and used not only to support compliance with the NIH requirement regarding RPPR reporting about IDP use with trainees at the institution, but also for benchmarking with other relevant PhD programs in the University. As a future consideration within pre- and postdoctoral training programs for nurse scientists, such forms may be using for benchmarking outcomes across schools.

Conclusion

IDPs can serve as a tool to improve communication, promote accountability, and structure mentoring meetings with trainees. At the program level, IDPs can assist with the development of consistent approaches to meeting expected program benchmarks and for equitable allocation of resources across trainees. Further, self-assessment and reflection are critical components of IDP development. These skills are critical to the ongoing professional development of the nurse scientist. Despite the fact that IDPs are highly recommended for use across NIH-funded training programs, significant variability exists in the specific forms used. However, common components were found across all IDPs used by NINR-funded T32s including self-assessment, goal setting, and identification of strategies to achieve goals. Thus, we conclude that IDPs can be tailored to meet individual trainee’s needs, while allowing for assessment of outcomes both within and across programs and schools.

Acknowledgments

This work, was supported, in part, by training grants from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Nursing Research: T32NR014833 (HJT), T32NR016913 (HJT and MMH), T32NR007091 (SJS), T32NR014225 (RHP and BM), T32NR012704 (JKA), T32NR015426 (JMA), T32NR007969 (SRB), T32NR009356 (KHB and MDN), T32NR009759 (YPC), T32NR012715 (SAD), T32NR013456 (LAE), T32NR008346 (MG), T32NR011147 (KAH and AMM), T32NR007104 (EL), T32NR016920 (CAM and SJW), T32NR015433 (SMM), T32NR014205 (PWS), T32NR016914 (MGT).

The authors acknowledge the help of Drs. David Banks and Rebekah Rasooly at the National Institute of Nursing Research in the initial phases of this work.

REFERENCES

- Austin J, & Alberts B. (2012). Planning career paths for Ph.Ds. Science, 337, 1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen N. (2003). The journey of the principles of adult mentoring inventory. Adult Learning, 14, 4–7. [Google Scholar]

- Clifford P. (2002). Quality time with your mentor. Scientist, 16, 59 https://www.the-scientist.com/fine-tuning/quality-time-with-your-mentor-52734. [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie GL, Gakumo CA, Von Ah D, Pesut DJ, Gonzalez-Guarda RM, & Thomas TA (2018). Summative evaluation of productivity and accomplishments of Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Nurse Faculty Scholars Program participants. Journal of Professional Nursing, 34, 289–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould J. (2017). Career development: A plan for action. Nature, 548, 489–490. [Google Scholar]

- National Institutes of Health Advisory Committee to the Director. (2012). Biomedical workforce work group report. http://acd.od.nih.gov/bwf.htm Accessed April 4, 2019.

- National Institutes of Health. (2013). NIH encourages institutions to develop individual development plans for graduate students and postdoctoral researchers. Retrieved from https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/NOT-OD-13-093.html Accessed April 4, 2019.

- National Institutes of Health. (2014). Descriptions on the use of individual development plans for graduate students and postdoctoral researchers required in annual progress reports beginning October 1, 2014. Retrieved from https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/NOT-OD-14-113.html Accessed April 4, 2019.

- National Postdoctoral Association. (2011). Recommendations for postdoctoral policies and practices. Retrieved from https://www.nationalpostdoc.org/page/recommpostdocpolicy Accessed April 15, 2019.

- Vanderford N, Evans T, Weiss L, Bira L, & Betran-Gastelum B. (2018). Use and effectiveness of the individual development plan among postdoctoral researchers: Findings from a cross-sectional study. F1000Research, 7, 1132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]