The COVID-19 pandemic stretched health care resources to their limit globally, but more so in the low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) that had limited health care resources even before the pandemic. Patients with cancer were a particularly vulnerable group because of the concerns with increased risk of severe infections and death from COVID-19.1 On the other hand, the diagnosis of cancer itself implies impending mortality for most patients with advanced disease. Experience from India showed that most patients with cancer wanted uninterrupted cancer treatment despite the risk of COVID-19.2 This required an unprecedented response from health care staff, who had to juggle their own safety and the safety of their families with providing care to patients with cancer during a pandemic. Thus, maintaining oncology services during a pandemic can lead to mental health challenges among health care staff.3 In this commentary, we discuss the possible sources of psychological stress on health care staff working during COVID-19 in cancer centers in LMICs, drawing examples from India and Nepal, and share the lessons in mitigating the psychological concerns of health care staff learned from the pandemic control exercise at Tata Medical Center, Kolkata, a multidisciplinary cancer center in India.

CAUSES OF PSYCHOLOGICAL STRESS IN CANCER CARE STAFF IN LMICS

The causes of psychological stress for cancer care workers in LMICs during the pandemic include some generic sources of stress and some LMIC-specific and oncology-specific sources. Because the burden of cancer in LMICs like India has grown exponentially, and the infrastructural and human resources were limited even before the pandemic, the anxiety of the impending catastrophe preceded the spread of the virus in India. As the pandemic evolved in the neighboring country of China, patients with cancer and health care providers started to mentally prepare for the looming double whammy of COVID and cancer. Information overload and real-time updates of mortality figures from around the world constantly reminded the health care workers in LMICs of the inadequacy of facilities and workforce. That the intensive care units and emergency services from even the best of countries were unable to contain the challenges of the pandemic and that even the most resourceful countries had shortages of personal protective equipment (PPE) contributed to substantial anxiety. With the news of health care workers succumbing to the virus in developed countries, health care workers in LMICs like India experienced burden and burnout just in anticipation, even before India had the surge in cases of COVID-19.

At the outset of the pandemic, test facilities for COVID-19 were not widely available in many LMICs, and there was a considerable delay before the definitive test results were available. This created additional pressure of having to care for “suspected” patients, increasing psychological stress, although the majority of suspected patients turned out to be negative. Moreover, a shortage of PPE made the health care staff feel vulnerable.4 The scarcity of hospital beds, inadequate manpower, and unprepared health care infrastructure adversely affected the treatment of non–COVID-19 ailments, including cancer, in countries like India or Nepal. Risk of COVID-19 infection, longer working hours, physical fatigue, loneliness, and shortage of PPE were found to be risk factors for poor psychological health among health care workers.5 In addition, in oncology, there is often an ethical and psychological dilemma in LMICs while choosing treatment options, because they are dictated not only by disease, biology or evidence but also by socioeconomic challenges. To account for a pandemic on top of these challenges added an extra layer of emotional burden on cancer clinicians.6

This pandemic has brought forth several other causes of psychological stress among cancer care workers that are unique to LMICs like India and Nepal. Most health care workers do not possess personal vehicles in LMICs. The lockdown in LMICs like India and Nepal also involved a restriction on public transportation. Even routine activities like commuting to work and getting back home on time now became a cause for psychological trauma, a unique scenario that to our knowledge did not occur in any high-income countries during the lockdown. In some cases commute was impossible, and health care workers had to arrange for a new place of accommodation nearby the hospital, adding to the mental stress and burnout. Outside the hospital, some health care workers faced considerable stigma and felt discriminated against by the community; they were refused entry to their own homes, suddenly kicked out of their apartments, and in rare cases even physically assaulted.7 In Nepal, on discovery of some physicians testing positive for COVID-19, the community ostracized them by putting up a banner in their home shaming them for bringing the disease to the local community and raising voices to evict physicians from houses where they were self-quarantining.8 It is thus likely that the causes of psychological stress in cancer care workers in LMICs were multifactorial, depending on the place of work, the specific role of the clinician, and the community’s perception of clinicians. One can only imagine the magnitude of psychosocial trauma for health care workers who are working in hospitals with the fear not only of contracting the infection and bringing the infection to their homes and families but also of being physically assaulted or socially ostracized from the community.

THE PREVALENCE AND TYPE OF PSYCHIATRIC MORBIDITIES IN CANCER CARE WORKERS IN LMICS

The severity of the short-term effect of the pandemic on health care staff in terms of stress, insomnia, anxiety, and depression is varied. It ranges from mild distress to suicide and depends on age, sex, and type of work,9,10 among other factors.11 A review of 59 studies with > 33,000 health care workers revealed that one in every five participants had either anxiety or depression, even before the pandemic.12 Insomnia was the most common symptom affecting one of every three health care workers.12 Studies from the Indian subcontinent also showed approximately one-third of doctors had anxiety or depression during the COVID-19 pandemic,13 and a report from Pakistan conducted on health care staff working in COVID-19 isolation wards, quantifying depression, anxiety and stress, showed 90.1% of participants reported moderate to extreme levels of psychological stress.14

CARING FOR THE CARERS

The leaders of health care institutions have important roles to help staff feel secure during the time of COVID-19. In India, many institutions set up a command center that coordinated the institutional response to the pandemic, so that clinical work could continue with minimum disruptions. The command center in Tata Medical Center, Kolkata was geographically away from the clinical areas to reduce the chances of its members contracting COVID-19. This was perceived to be useful, as most staff could focus on their own work and feel reassured that there was centralized decision making. This team kept the staff updated about relevant practical information for managing the pandemic locally, and the information cascade was done through group e-mails and virtual meetings.

The staff in many of the subspecialties in oncology benefited by changing over to a shift pattern of work; one group of staff worked on site and others worked remotely from home, reducing the odds of being exposed to patients with possible COVID-19 infection. If any staff members were unable to commute because of the lockdown, transport and accommodation were provided. Employees were paid on time or even slightly early to ease financial anxiety. We believe that all these measures boosted the morale of the staff working during crisis times.

The institution started telephone and video-based consultation for patients with cancer where feasible, which included providing psychiatric and psychological support to patients through the clinicians in the psycho-oncology department. This psychological support was also extended to staff who were distressed and included those who were quarantined or those under home isolation.

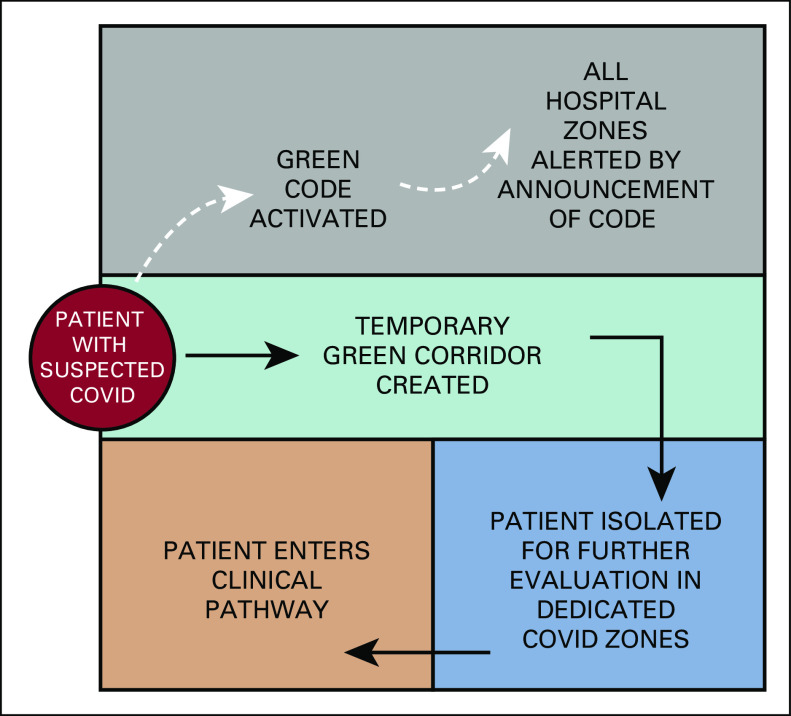

The hospital had set up screening desks for all patients coming inside the premises of the hospital so that unintended exposure of health care workers to patients with suspected COVID could be minimized. Despite all the screening measures, one of the causes of distress among staff was to suddenly discover a patient having symptoms suggestive of COVID-19 who was not identified with the usual questionnaire at the screening desk. We report a unique intervention started in Tata Medical Centre, Kolkata, where a new “green code” was developed to organize care for a patient with any symptoms suggestive of COVID-19 (Fig 1). This diminished the staff’s stress and made them feel protected.

FIG 1.

On encountering a patient with potential COVID infection, staff activated the green code. This triggered a particular set of responses that included being supportive to the patient, escorting the patient to an isolation facility for further evaluation, and reducing transmission to other staff and patients.

The hospitals also devised a rota of staff responsible for the care of patients with COVID-19, comprising doctors and nurses from a number of departments to reduce the burden on any individual staff or department. Staff members were informed about recent government circulars regarding protection offered by statutory agencies to health care professionals and also exemption from general movement restrictions imposed on the public by the state.15 If needed, the human resources department provided staff with a copy of the government order that they could use for movement despite the lockdown. In exceptional circumstances, the chief security officer of the hospital liaised with the community leaders to reassure them about the steps that were being taken to look after the hospital staff.

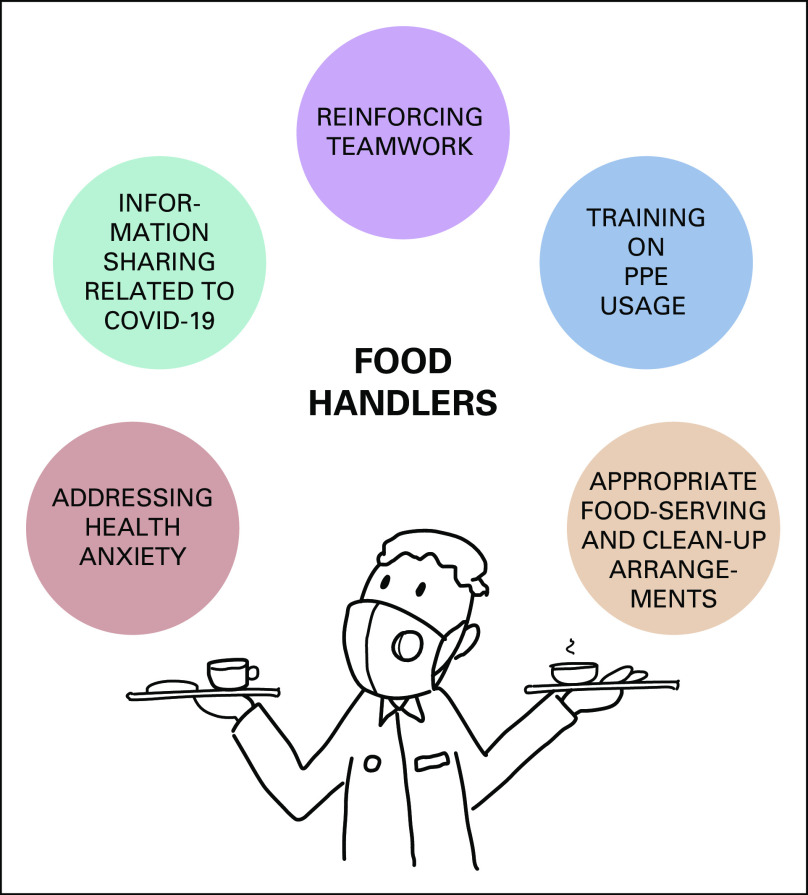

Several educational sessions were organized for various staff groups of the hospital to address anxieties and fears. The sessions are conducted by two psychiatrists, a microbiologist, and a public health specialist. The discussions were specific to the job roles of the staff (Fig 2). Broadly, the sessions included listening to the worries voiced by staff, addressing their information needs, and some skill transfer related to PPE usage and other related topics, depending on the job role of the specific group of staff in the meeting.

FIG 2.

An example interactive session with staff (organized for food handlers).

However, there were many generic queries as well. One of the main topics of discussion was the transmissibility of COVID-19. A large part of the discussions was around worries of transmitting the illness to family members once the staff got back home. Scientific and common-sense measures were discussed with all members of staff. The sessions also tried to address some of the myths around measures that could be taken to prevent SARS-CoV-2 infections. Hand-washing steps were demonstrated on an ongoing basis and revised by the trainers for the new staff. During the meetings, there was always some protected time for a frank discussion about anything that the staff felt to be important. The trainers did not always have the answers to all the questions the staff asked. Honesty was valued by the attendees in their feedback. The trainers shared accepted knowledge, while admitting the gaps in the current understanding of the situation. These communications built a bridge between various departments and acted as a conduit for information and views to be carried to the command center from the front-line staff.

Occupational mental health used psychological methods to improve the emotional well-being of staff. Psychological first aid was offered for those who were acutely stressed and those who reached the clinical threshold for a psychiatric disorder.

SILVER LININGS

Most health organizations understood that they needed to continue to deliver routine medical care in addition to handling the COVID pandemic, as the pandemic did not show signs of disappearing anytime soon. Staff members adapted to the change and were psychologically supported to accept the new normal. The human loss, both in terms of mortality due to COVID-19 and indirectly because of social, medical, emotional, and financial impact of COVID will be difficult to quantify. However, as in any crisis, in the longer term, COVID-19 should be viewed as a unique learning opportunity for health care staff. With high-quality online learning events that could be accessed free of cost from around the world, many staff cognitively restructured the adversity as an opportunity for learning that they had never had in the past. In some specialties, junior staff felt more empowered and confident in making decisions. During the COVID-19 pandemic, it was seen that team bonding improved within the hospital. The vulnerability of life probably taught staff the value of what was available.

In conclusion, we believe that the COVID-19 pandemic taught us the importance of being empathic, sensitive, and responsive in the face of a crisis. Nourishing the mental health of staff working in a cancer center is always critical for a healthy cancer care ecosystem, but this is all the more important during the time of crisis. In LMICs, cancer care workers face several unique challenges in addition to the routine challenges of working during a pandemic. The lessons learned during this pandemic will be helpful for us and other institutions in LMICs to prepare for the challenges of this and future pandemics, especially with regard to preserving the mental health of health care staff.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Soumitra S. Datta, Soumita Ghose, Sanjay Bhattacharya, Bishal Gyawali

Administrative support: Soumitra S. Datta, Bishal Gyawali

Collection and assembly of data: Soumitra S. Datta, Arnab Mukherjee, Soumita Ghose, Bishal Gyawali

Data analysis and interpretation: Soumitra S. Datta, Arnab Mukherjee, Soumita Ghose, Bishal Gyawali

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/go/site/misc/authors.html.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

No potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Karacin C, Bilgetekin I, Basal FB, et al. doi: 10.2217/fon-2020-0592. How does COVID-19 fear and anxiety affect chemotherapy adherence in patients with cancer Future Oncol . [epub ahead of print on July 17, 2020] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Ghosh J, Ganguly S, Mondal D, et al. Perspective of oncology patients during COVID-19 pandemic: A prospective observational study from India. JCO Glob Oncol. 2020;6:844–851. doi: 10.1200/GO.20.00172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reger MA, Piccirillo ML, Buchman-Schmitt JM. COVID-19, Mental health, and suicide risk among health care workers: Looking beyond the crisis. J Clin Psychiatry. [epub ahead of print on August 4, 2020] [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Gold JA. Covid-19: Adverse mental health outcomes for healthcare workers. BMJ. 2020;369:m1815. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kang L, Li Y, Hu S, et al. The mental health of medical workers in Wuhan, China dealing with the 2019 novel coronavirus. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:e14. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30047-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu Q, Luo D, Haase JE, et al. The experiences of health-care providers during the COVID-19 crisis in China: A qualitative study. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8:e790–e798. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30204-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ravi R. Abused, Attacked, Beaten: Frontline Workers Are Risking Their Lives Everyday In India. 2020 https://thelogicalindian.com/news/covid-19-healthcare-workers-attacked-20665

- 8.Poudel A. Health workers under attack as lack of Covid-19 awareness is fuelling stigma. https://kathmandupost.com/health/2020/08/23/health-workers-under-attack-as-lack-of-covid-19-awareness-is-fuelling-stigma.

- 9.Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e203976. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bohlken J, Schömig F, Lemke MR, et al. COVID-19 pandemic: Stress experience of healthcare workers - a short current review [in German] Psychiatr Prax. 2020;47:190–197. doi: 10.1055/a-1159-5551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kisely S, Warren N, McMahon L, et al. Occurrence, prevention, and management of the psychological effects of emerging virus outbreaks on healthcare workers: Rapid review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020;369:m1642. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pappa S, Ntella V, Giannakas T, et al. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;88:901–907. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chatterjee SS, Bhattacharyya R, Bhattacharyya S, et al. Attitude, practice, behavior, and mental health impact of COVID-19 on doctors. Indian J Psychiatry. 2020;62:257–265. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_333_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sandesh R, Shahid W, Dev K, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of healthcare professionals in Pakistan. Cureus. 2020;12:e8975. doi: 10.7759/cureus.8974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Government of West Bengal: Order No 27/CS dated 25/03/2020. https://wb.gov.in/COVID-19/LD5.pdf.