Abstract

Introduction

Medications are compounded when a formulation of a medication is needed but not commercially available. Regulatory oversight of compounding is piecemeal and compounding errors have resulted in patient harm. We review compounding in the United States (US), including a history of compounding, a critique of current regulatory oversight, and a systematic review of compounding errors recorded in the literature.

Methods

We gathered reports of compounding errors occurring in the US from 1990 to 2020 from PubMed, Embase, several relevant conference abstracts, and the US Food and Drug Administration “Drug Alerts and Statements” repository. We categorized reports into errors of “contamination,” suprapotency,” and “subpotency.” Errors were also subdivided by whether they resulted in morbidity and mortality. We reported demographic, medication, and outcome data where available.

Results

We screened 2155 reports and identified 63 errors. Twenty-one of 63 were errors of concentration, harming 36 patients. Twenty-seven of 63 were contamination errors, harming 1119 patients. Fifteen errors did not result in any identified harm.

Discussion

Compounding errors are attributed to contamination or concentration. Concentration errors predominantly result from compounding a prescription for a single patient, and disproportionately affect children. Contamination errors largely occur during bulk distribution of compounded medications for parenteral use, and affect more patients. The burden falls on the government, pharmacy industry, and medical providers to reduce the risk of patient harm caused by compounding errors.

Conclusion

In the US, drug compounding is important in ensuring access to vital medications, but has the potential to cause patient harm without adequate safeguards.

Keywords: Compounding, Pharmacy, Error, Contamination, Toxicology, Regulation

Introduction

In the modern-day United States (US), medications are by-in-large manufactured in commercial facilities, and this production is regulated and overseen by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Historically, however, medications were mixed—or compounded—by independent pharmacists for use by individual patients. While traditional compounding is becoming less prevalent, it still occurs in instances where a particular patient may require a formulation of a medication that is not otherwise available. Furthermore, a new form of large-scale compounding has become commonplace, whereby pharmacies produce bulk volumes of medications which are not available commercially, and broadly distribute them to healthcare practices and individual patients.

Compounding does not traditionally fall under the purview of FDA oversight, instead being regulated by individual states’ boards of pharmacy. This approach has resulted in a patchwork and oftentimes underfunded regulatory framework, which has subsequently harmed patients [1–4]. Morbidity and mortality frequently result either from a compounded medication that is contaminated with bacteria, fungi, or another medication during production, or from an error whereby the concentration of the drug dispensed is not as intended, which can lead to inadvertent over- or under-dosing. Patient harm caused by compounded medications has been the focus of media, medical, and legislative attention in recent years, especially following a multistate, multi-fatality outbreak of fungal meningitis caused by contaminated steroid injections compounded at a pharmacy in Framingham, MA [2, 3, 5, 6].

This article seeks to provide a comprehensive review of the state of outpatient compounding in the US. Compounding performed by hospital pharmacies for inpatient use is beyond the scope of this paper. Much has been written on compounding pharmaceuticals; this paper is an effort to succinctly address the history, purpose, and regulatory framework in a unified location, as well as to perform a systematic review of all US compounding errors over the past 30 years. To our knowledge, no systematic review of both contamination and non-contamination errors has to this point been undertaken. We will first explore the definition and modern role of compounding. Then, we will briefly discuss the modern US history of compounding, with a particular focus on factors influencing the current state of compounding. Next, we will examine compounding through a legislative and regulatory lens, to better decipher how governmental oversight—or a lack thereof—may contribute to errors in compounding resulting in patient harm. Understanding the interventions being made on a federal level can help improve the safety of compounding. Finally, we have performed a systematic review of documented compounding errors and categorized those errors by type and patient outcome. Whereby, we elucidate just how and with what frequency patients are harmed by compounding errors, with the ultimate aim of identifying potential strategies for reducing these adverse events.

Compounding: What It Is and Why It Is Essential

Compounding is defined by the FDA as the combination, mixing, or alteration of drug ingredients to create medications tailored to individual patient needs [7]. The United States Pharmacopeia (USP), which sets quality standards for drugs, describes compounding as “the preparation, mixing, assembling, altering, packaging, and labeling of a drug … in accordance with a licensed practitioner’s prescription …” [8] Put simply, it is the creation of a medication that is not commercially available.

In the US, compounding is performed in both the inpatient hospital setting and in outpatient pharmacies, with a trend in recent decades towards larger scale outpatient production [9]. As will be discussed later in this paper, compounding may now occur in newly defined “outsourcing facilities,” which are designed to compound in bulk; some examples of these facilities include QuVa Pharma and Leiters [10]. There are many indications for compounding. Some patients may not tolerate pills and require a compounded liquid drug formulation; examples include young children taking antibiotics, feeding tube-dependent patients, or patients with dysphagia from neurologic compromise such as a stroke [11, 12]. Patients may be allergic to binding agents, dyes, diluents, or other inactive ingredients in commercially available formulations. Dietary restrictions, such as a ketogenic diet in pediatric epilepsy patients, may necessitate compounding of sugar-free medications [13]. Refractory neuropathic pain may benefit from compounded analgesic topical creams containing multiple medications not commercially available in combination; examples include ketamine, baclofen, gabapentin, amitriptyline, bupivacaine, and clonidine [14]. Painful oral lesions can be treated with “magic mouthwash” and dyspepsia can be treated with a “gastrointestinal (GI) cocktail”; these are terms that actually encompass a range of compounded preparations [15]. Total parenteral nutrition (TPN) is needed for patients unable to take in sufficient oral nutrition, and numerous chemotherapy regimens must be compounded for cancer treatment [16, 17]. Healthcare providers may need compounded medications to perform specialized procedures such as intraarticular or intravitreal injections. In some instances, commercial preparations may be available but expensive, and a compounded equivalent is more affordable [18]. Drug shortages, a longstanding healthcare problem exacerbated by crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic and the devastation of Puerto Rico by Hurricane Maria, may be addressed by compounding as well [19, 20]. The FDA has responded to significant shortages during the COVID-19 pandemic by temporarily relaxing restrictions on compounding of commercially available drugs [21, 22].

When a compounded medication is prescribed or administered, patient safety depends on adherence to Current Good Manufacturing Practices (CGMP), which are outlined in Chapter 795 of the USP for non-sterile preparations and Chapter 797 for sterile preparations. Appropriateness of the prescription indication, safety, and dosing should be assessed by the pharmacist. Ingredient quantities must be meticulously calculated, and the source quality of those ingredients assured. Compounding facilities and equipment must be clean and monitored continuously. Staff must routinely practice and be assessed for competency in proper hygienic measures. Sterile preparations, by definition, require a higher level of care to prevent contamination than do non-sterile preparations, including differences in staff training and personal protective equipment (PPE), environment and air quality monitoring, and disinfection. Compounded sterile preparations are further subdivided into low-, medium-, and high-risk depending upon the quantity of ingredients, number of manipulations required during compounding, and whether nonsterile ingredients requiring subsequent sterilization are incorporated. Multiple medications must not be simultaneously compounded in the same workspace. The compounding process must be reproducible such that medication quality is consistent throughout many production cycles. Finally, prescriptions must be correctly labeled and patients instructed in appropriate use [8, 23–25]. Failure to adhere to these standards has the potential to result in patient harm through multiple mechanisms including medication suprapotency, subpotency, contamination, and consumer misuse.

Historical Context

Throughout pre-industrial history, pharmacists played the critical role of admixing various materials to produce a finished therapeutic substance. This role was, in essence, one of compounding [26, 27]. However, the industrial revolution and the resultant mass production of pharmaceuticals—coupled with the increasing presence of synthetic proprietary medications—led to a change in pharmacists’ primary role. Instead of compounding, community pharmacists in the early 1900s turned their focus to the dispensing of previously manufactured medications as well as to general retail, including operating the soda fountains which came into vogue with the prohibition of alcoholic beverages. In fact, by the 1930s, fewer than 1% of pharmacies in the US made a majority of their income from pharmaceutical sales [27].

The decline in community pharmacy compounding was precipitous through the mid-1900s. In the 1930s, 75% of prescriptions required some sort of in-pharmacy compounding. That number fell to 25% by the 1950s, less than 5% by 1960, and to 1% by 1970 [28]. Interestingly, there was a concurrent increase in the need for hospital pharmacy compounding during the same period; largely due to the advent of chemotherapy, TPN, and cardiac surgery which necessitated the administration of complex cardioplegic regimens. By the 1980s, these advanced therapeutics began to spill into the outpatient setting, generating a novel home infusion industry for treatments such as TPN, antibiotics, and chemotherapeutics [29]. As a result, the 1990s and 2000s yielded further diversification within the compounding industry as pharmacies began to compound in bulk. This development was brought about by expanding home infusion programs, the more frequent outsourcing of hospital compounding to the outpatient setting, and the rise of hormone replacement therapy. Large volume compounding blurs the line between traditional compounding which has state-based regulatory oversight, and the mass manufacture of pharmaceuticals which falls under well-established federal FDA regulations [29–31].

The inspiration for this article is a well-documented history of medication errors attributable to pharmaceutical compounding, for which a lack of regulatory oversight persists as a common thread [3, 29, 32, 33]. The most lethal and infamous of these cases occurred in 2012, when an outbreak of fungal meningitis occurred amongst patients who had received epidural spinal injections. The outbreak affected 753 patients across 20 states, killing 64 [5, 6, 34, 35]. Ultimately, the outbreak was linked to a compounding pharmacy, the New England Compounding Center (NECC, located in Framingham, MA). Amongst other pharmaceuticals, NECC produced injectable sterile methylprednisolone acetate for epidural injections, which it then distributed nationally. Following the outbreak (hereafter “Framingham”), the FDA determined that the pharmacy had disregarded basic sanitary standards and had not taken corrective measures despite internal knowledge of potential contamination [2, 5, 6, 34–36]. As with many compounding pharmacies, NECC operated in a historically murky regulatory space, producing medications in bulk as would a commercial pharmaceutical manufacturer, while only being subjected to reduced state oversight given to compounding pharmacies. In fact, in the years preceding the outbreak, the FDA had thrice investigated NECC and found sterility violations, but they were unable to enforce any interventions or penalties due to the FDA’s contested regulatory jurisdiction [4]. Both preceding and following Framingham, efforts have been made at the federal level to improve oversight of compounding; these are reviewed in depth later in this article. Currently, there is incomplete tracking of compounded pharmaceuticals in the US, though they are estimated to comprise 1–3% of all prescriptions [30, 31, 37, 38]. Ultimately, compounding is highly prevalent, and so clinicians must be familiar with the risks associated with compounded medications as they care for patients who may be suffering from a related adverse event.

Regulatory and Legislative Framework

Prior to Framingham, modern compounding pharmacies evolved within a regulatory framework that lacked distinct federal or state oversight roles. In 1938, the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FDCA) authorized FDA oversight of pharmaceutical manufacturing [39]. However, because compounders traditionally produced drugs in response to individual prescriptions and on a much smaller scale than conventional drug manufacturers, pharmaceutical compounding developed and remained under the regulatory purview of individual state boards of pharmacy [32, 40]. Towards the end of the twentieth century, pharmacies began bulk compounding in response to (1) the home infusion industry and (2) hospitals’ financial interest in outsourcing compounding from their inpatient pharmacies to the outpatient setting [29]. Concerned that bulk compounders were self-classifying as pharmacies to avoid the rigorous federal oversight required of drug manufacturers under the FDCA, Congress passed the 1997 Food and Drug Administration Modernization Act (FDAMA) [40]. FDAMA addressed the changing nature of compounding pharmacies by creating a “safe harbor” exempting pharmacies from the more stringent FDCA regulations so long as compounders refrained from advertising their product and abided by requirements designed to increase drug safety [40, 41].

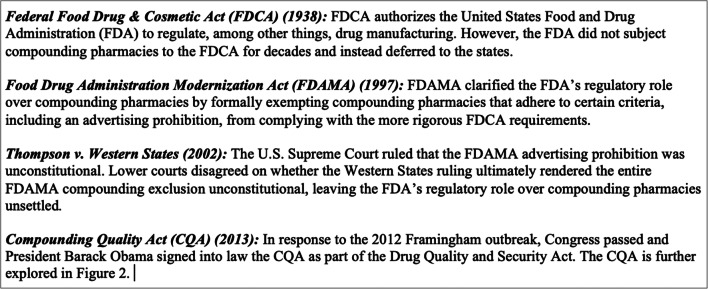

Despite Congress’s attempt to strengthen oversight of compounding pharmacies, litigation challenging FDAMA tempered the FDA’s authority to regulate compounders. In 2002, a narrowly divided US Supreme Court ruled in Thompson v. Western States Medical Center that the FDAMA advertising prohibition was unconstitutional on First Amendment free speech grounds [42]. The ensuing regulatory confusion is well described in the literature, and the details are beyond the scope of this review [3, 28, 29, 31, 32, 40]. For reference, a summary of the relevant legislation and litigation is provided in Fig. 1. Decades of regulatory uncertainty culminated in the 2012 Framingham incident, which revived Congressional efforts to address pharmaceutical compounding industry safety concerns.

Fig. 1.

Significant federal legislation and litigation related to compounding pharmacies.

In response to Framingham, Congress passed and President Barack Obama signed into law the bipartisan-supported Compounding Quality Act (CQA) as part of a broader legislative package (the 2013 Drug Quality and Security Act) [43]. The CQA delineated state and federal oversight authority by defining two distinct categories of compounding pharmacies. The first category is traditional compounding pharmacies, or “503A” pharmacies [44]. 503A pharmacies under the CQA may compound only in response to individual prescriptions. Importantly, 503A pharmacies may not compound bulk medications either in anticipation of receiving prescriptions or with plans to distribute broadly to healthcare facilities [31, 45]. In exchange for complying with these limitations, 503A pharmacies largely avoid the more burdensome regulations required of drug manufacturers under the FDCA, including adhering to CGMP [31, 37, 46–48]. Accordingly, state boards of pharmacy continue to serve as the primary regulators of 503A pharmacies [45].

The CQA created a second category of compounding pharmacy, called an “outsourcing facility.” [49] Unlike 503A pharmacies, outsourcing facilities voluntarily opt-in to this category by paying the FDA a user fee (approximately $18,298 in FY2020) [50], and comply with stringent CGMP standards as well as reporting requirements [38, 46]. Because they submit to more robust FDA oversight, outsourcing facilities are permitted to compound in bulk in advance of receiving a prescription, and may distribute their products across state lines [31, 51]. Though the FDA enjoys primary regulatory authority over outsourcing facilities, states are not precluded from imposing additional requirements [51]. Should a compounding pharmacy fail to comply with the 503A criteria or voluntarily register as an outsourcing facility, it is subject to the full breadth of regulations required of drug manufacturers under the FDCA [37]. The distinctions between 503A pharmacies and outsourcing facilities are illustrated in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Key provisions of the 2013 Compounding Quality Act.

Following enactment of the CQA, states have taken numerous steps to further develop their respective oversight structures under the new framework. A majority of states have strengthened regulations empowering state boards of pharmacy to hold 503A pharmacies accountable to higher safety practices, such as requiring conformation with recognized sterile compounding guidelines. However, state oversight of 503A pharmacies continues to vary, with fewer than half of all states reporting annual inspections of 503A pharmacies in 2018 [52].

The FDA has similarly adjusted its enforcement priorities [53, 54]. For example, the CQA permits a 503A pharmacy to distribute no more than 5% of its total prescriptions out of state unless the pharmacy’s home state enters into a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with the FDA [55]. The goal of this provision is to avoid another national outbreak by reducing the likelihood that contaminated drugs cross state lines. If a given state enters into a MOU with the FDA, 503A pharmacies in that state may distribute a higher percentage of prescriptions (now up to 50%) across state lines in exchange for that state’s board of pharmacy agreeing to identify, investigate, and report associated adverse events [ 45]. Importantly, the MOU standardizes procedures for state boards of pharmacy to report concerns to the FDA and other states; however, the agreement also grants states significant discretion in how states conduct investigations [54]. In short, states that participate in the MOU, rather than the FDA, will undertake primary responsibility for detecting poor quality or dangerous compounded medications distributed by 503A pharmacies from their state.

The FDA also announced an effort to entice more compounding pharmacies to register as outsourcing facilities by embracing a risk-based approach [45]. Since enactment of the CQA, far fewer pharmacies have registered as outsourcing facilities than the FDA had expected. In fact, the FDA anticipated 50 pharmacies to register per year, but only 78 total were registered as of May 2020 (even fewer than the 91 registered in 2016) [38, 51, 56]. To attract compounding pharmacies—some of which have cited cost of compliance with CGMP as a prohibitively expensive barrier to registering as an outsourcing facility—the FDA plans to reduce CGMP requirements for compounding pharmacies it deems as “lower risk.” [45] Though the FDA published draft guidance in 2018 describing how the agency may tailor CGMP requirements for outsourcing facilities, the FDA has yet to issue final guidance on this matter [53, 57].

Critics warn that FDA and state efforts to implement the CQA regulatory scheme excludes compounding pharmacies from the decision-making process and may limit patients’ access to compounded medications. For example, the Preserving Patient Access to Compounded Medications Act (H.R. 1959) introduced in the US House of Representatives attempts to address complaints expressed by compounders [58]. The proposed legislation seeks to ensure that compounders and other interested parties have an opportunity to comment on (and influence) FDA compounding regulations. Furthermore, the proposed legislation would explicitly allow physicians who engage in in-office sterile compounding, or who otherwise maintain a supply of compounded medications for “office use,” to avoid complying (where state law permits) with outsourcing facility regulations [58].

Meanwhile, the sterility practices of some compounding pharmacies continue to raise alarm: between 2013 and 2018, the FDA issued more than 180 warning letters to compounding pharmacies, resulting in approximately 140 recalls. As acknowledged by the agency, the FDA’s transition to a risk-based approach may assist the agency in more efficiently targeting its limited resources, but it could also increase the likelihood of compounders engaging in unsafe practices that elude regulators [45]. In sum, the CQA and subsequent state and FDA actions have somewhat clarified oversight roles after Framingham, largely by defining separate 503A pharmacies and outsourcing facilities. Seven years after its enactment, however, uncertainty regarding the relative strength and consistency of said regulatory framework remains.

Methods

We performed a systematic review of compounding errors, including both errors that resulted in patient harm and those that did not, as reported in the academic literature. We searched the National Center for Biotechnology Information (PubMed; U.S. National Library of Medicine: Bethesda, Maryland) and Embase (Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands) using the following search criteria: “‘compounding AND pharmacy’ AND ‘error,’ ‘overdos*,’ ‘toxicol*,’ ‘infect*,’ ‘death,’ ‘outbreak,’ ‘injur*,’ OR ‘case report.’” This search was limited to January 1990 through March 2020. Additionally, we reviewed abstracts for years 1990–2019 for the following conferences using keyword searches for “compound” and “compounding”: American College of Medical Toxicology (ACMT) Annual Scientific Meeting, North American Congress of Clinical Toxicology (NACCT), American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) Scientific Assembly, Society for Academic Emergency Medicine (SAEM) Annual Meeting, American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) National Conference & Exhibition, and the Pediatric Academic Societies (PAS) Meeting. We also reviewed the FDA’s online “Drug Alerts and Statements” repository for alerts regarding compounding pharmacies’ failures in sterility and potency standards. Authors CJW and JDW screened reports by title and, when necessary for clarification, by abstract. Under manual review, articles were excluded if they were obviously irrelevant, consisted of research comparing samples of compounded and commercial pharmaceuticals, were in a non-English language, regarded medications compounded outside of the US, were redundant with another included report, represented misuse of properly compounded medications, regarded veterinary patients, were compounded by an inpatient hospital pharmacy (including chemotherapeutics and parenteral nutrition), were published prior to 1990, or if the report lacked sufficient information to provide substantive value. Redundant reports of the same error were included for analysis only once, but efforts were made to reference all identified reporting sources. For included reports, CJW and JDW extracted information including date, type of error, cause of error, number of patients affected, age of patients affected, and clinical course of patients affected. Incomplete data was acknowledged and by-in-large was not grounds for exclusion from the study.

We categorized errors under the conceptual framework described by Sarah Sellers, PharmD, MPH, former board member for the FDA’s Advisory Committee on Pharmacy Compounding, in testimony to the US Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions, namely, that “suprapotency,” “subpotency,” and “contamination” are the primary risks associated with pharmaceutical compounding [59]. We further broke down “contamination” into subgroups of “microbiologic contamination” for cases of bacterial, viral, or fungal contamination and “toxic contamination” for non-infectious contaminants. When available, we documented patient age and outcome, route of administration, and medication-in-question, so as to better characterize the types of medications, errors, and patients most associated with adverse events.

We referenced and applied the principles for authoring review articles delineated within the Journal of Medical Toxicology when feasible and appropriate during the review process [60].

Findings

Our search terms identified 1058 potential articles in PubMed and 721 potential articles in Embase. The review of conference abstracts yielded additional potential cases as follows: ACMT Annual Scientific Meeting (49; original research first reported at this conference in 2011), NACCT (235; abstracts available from 1997 to 2019), ACEP Scientific Assembly (9; data missing for 1993, 1995, 1996), SAEM Annual Meeting (34), AAP National Conference & Exhibition (0; abstracts available from 2010 to 2018), and the PAS Meeting (0; abstracts available from 2017 to 2019). The FDA’s “Drug Alerts and Statements” repository contained an additional 19 reports related to non-hospital-based compounding pharmacies. Through the database searches, two pre-existing reviews of compounding contamination errors were identified, by Staes et al. in 2013 and Shehab et al. in 2018; these respectively identified 11 and 19 cases [61, 62]. In total, a total of 2155 articles, statements, and reports were identified and underwent our manual review (performed by CJW and JDW).

After the application of our exclusion criteria, a total of 63 errors were included. These 63 errors are documented as harming 1155 patients. When broken down by type, contamination accounted for 27 errors adversely affecting 1119 patients (Appendix Table 3) and errors in concentration accounted for 21 events adversely affecting 36 patients (Appendix Table 4). There were 15 reports of identified compounding errors which potentially exposed innumerable patients but did not end up causing any known harm; these were predominantly errors of contamination (Appendix Table 5). The number of patients exposed to potential harm cannot be calculated based on the available data, but reaches at least the several thousands (Framingham alone exposed 13,534 patients with 753 documented instances of patient harm).

Supplemental Table 1.

Contamination compounding errors

| Year of outbreak (Citation) | Contaminated Product | Patients | Average Age (Years) | Pharmacy Location (State) | Location(s) of Outbreak Cases (State) | Where Product(s) Received | Reason for Compounding | Contaminant | Cause of Contamination | Route(s) of Administration | Complications (No. Affected, If Known) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2001 [63] |

Betamethasone | 11 | 66 | CA | CA | Ambulatory surgery center | Drug shortage, off label | Serratia marcescens | Inadequate autoclaving temperatures, failure to perform terminal sterilization | Epidural injection, joint injection |

Meningitis (5 cases, 3 deaths), epidural abscess (5 cases), hip septic arthritis (1 case) |

|

2002 [62] |

Methylprednisolone | 2 | Unknown | MI | MI | Unknown | Drug shortage, off label | Chryseomonos luteola | Unknown | Epidural injection | Meningitis (2) |

|

2002 [68] |

Intrathecal morphine with clonidine, bupivacaine | 8 |

58 (2 patients ≥ 65-years) |

TN | TN | Pain clinic | Intrathecal formulation not commercially available | Methadone, ethanol, methanol | Likely poor labeling, insufficient safety and quality control | Intrathecal | Altered mental status (3), aseptic meningitis (1), extradural/intradural mass or abscess (4) |

|

2002 [64, 65] |

Methylprednisolone | 6 |

65 (3 patients ≥ 65-years) |

SC | NC | Pain clinic | Drug shortage, off label | Exophiala dermatitidis | Improper autoclaving, sterility testing, clean room practices | Epidural injection | Meningitis (4 cases, 1 death), sacroileitis (1), lumbar diskitis |

|

2004 [79] |

Heparin-vancomycin | 2 |

5.5 (2 patients < 18-years) |

FL | CT | Home health | High-volume acute care product | Burkholderia cepacia | Unknown | Catheter flush | Bacteremia/sepsis (2) |

| 2004–2005 [80, 81] | Cardioplegia solution | 11 | Unknown | MD | VA | Hospital | High-volume acute care product | Unknown, multiple GNR species in unopened cardioplegia bags | Unknown | Coronary infusion |

Bacteremia (11 cases, 3 deaths) |

| 2004–2006 [82] | Heparin-sodium chloride | 80 | Unknown | TX | MI, MO, NY, SD, TX, WY | Inpatient, outpatient, home health | High-volume acute care product | Pseudomonas species | Unknown | Catheter flush | Bacteremia (80) |

|

2005 [83] |

Magnesium sulfate | 19 | Unknown | TX | CA, MA, NC, NJ, NY, SD | Hospital | High-volume acute care product | Serratia marcescens | Unknown | Intravenous injection | Bacteremia (18), sepsis (1) |

|

2005 [71] |

Tryptan blue | 6 | Unknown | MN | DC, MN | Ophthalmologic surgery | High volume surgery product | Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Burkholderia cepacia | Unknown | Intraocular injection | Endophthalmitis (6) |

|

2007 [69] |

Fentanyl | 8 |

52 (2 patients ≥ 65-years) |

MS (suspected) | CA, MD | Hospital | High-volume acute care product, custom concentration | Sphingomonas paucimobilis | Unknown | Intravenous injection |

Bacteremia (8 cases, 1 death) |

|

2007 [72] |

Bevacizumab | 5 | Unknown | TN | TN | Ophthalmology clinic | High-volume surgery product, off label | Alpha hemolytic streptococcus | Face mask non-compliance | Intraocular injection | Endophthalmitis (5) |

|

2011 [84] |

TPN | 19 | Unknown | AL | AL | Hospital | High-volume acute care product, drug shortage | Serratia marcescens | Mixing, filtration, sterility testing breaches | Intravenous injection |

Bacteremia (19 cases, 9 deaths) |

|

2011 [73] |

Bevacizumab | 12 | 78 | FL | FL | Ophthalmology clinic | High-volume surgery product, off label | Streptococcus mitis/oralis | Unknown | Intraocular injection | Endophthalmitis (12) |

| 2011–2012 [77] | Brilliant Blue Green (BBG), Triamcinolone | 47 | Unknown | FL | CA, CO, IL, IN, LA, NC, NV, NY, TX | Ambulatory surgery center | Commercially unavailable, off label (BBG) | Fusarium incarnatum-equiseti, Bipolaris hawaiiensis | Contaminated clean room | Intraocular injection | Endophthalmitis (47) |

|

2012 [74] |

Bevacizumab and triamcinolone | 8 |

65 (3 patients ≥ 65-years) |

Unknown | NY | Ophthalmology clinic | Formulation not commercially available | Exserohilum speces, Bipolaris hawaiiensis | Reuse of contaminated bottle of medication to fill multiple single-use vials | Intraocular injection | Endophthalmitis (8) |

|

2012 [6, 66] |

Methylprednisolone | 753 | Unknown | MA | FL, GA, ID, IL, IN, MD, MI, MN, NC, NH, NJ, NY, OH, PA, RI, SC, TN, TX, VA, WV | Various | Commercially unavailable preservative-free, off label | Exserohilum rostratum, Aspergillus fumigatus, other fungi | Contaminated clean room, nonsterile ingredients, improper autoclave use | Spinal (e.g., epidural, nerve root block), paraspinal (e.g., sacroiliac), peripheral joint injection | 13,534 potential exposures, Meningitis (234); Meningitis + Paraspinal Infection (152); Stroke (7); Paraspinal Infection (325); Joint Infection (33); Paraspinal Infection + Joint Infection (2); Deaths (64) |

|

2012 [70] |

Fentanyl | 7 |

37 (1 patient < 18-years) |

NC | NC | Hospital | High volume acute care product | Burkholderia cepacia | Contaminated clean room | Intravenous injection | Bacteremia (7) |

| 2012–2013 [67] | Methylprednisolone | 26 | Unknown | TN | AR, FL, IL, NC | Various | Commercially unavailable preservative-free, off label | Enterobacter cloacae, Klebseilla pneumoniae, Aspergillus spp. | Violations of sterile compounding best practices | Intramuscular injection | Skin/soft tissue infection (26) |

|

2013 [75] |

Bevacizumab | 5 | 80 | GA | GA, IN | Ophthalmology clinic | High-volume surgery product, off label | Granulicatella adiacens, Abiotrophia spp. | Violations of sterile compounding best practices | Intraocular injection | Endophthalmitis (5) |

|

2013 [85] |

Methylcobalamin | 6 | Unknown | TX | TX | Unknown | Commercially unavailable, off label | Unknown | Violations of sterile compounding best practices | Intravenous injection | Fever, flu-like symptoms (6) |

|

2013 [86] |

Calcium gluconate | 15 | Unknown | TX | TX | Hospital | Drug shortage, off label | Rhodococcus equi | Violations of sterile compounding best practices | Intravenous injection | Bacteremia (15) |

|

2016 [87]* |

Omeprazole suspension | 1 | 4 months | Unknown | MA | At home | Liquid formulation for feeding tube administration | Baclofen | Accidental baclofen substitution for sodium bicarbonate powder | Enteral | Decreased mental status, metabolic acidosis, recurrent seizures (1) |

|

2016 [88]* |

Biotin | 2 | Unknown | CA | Unknown | Unknown | Commercial formulation not available | 4-Aminopyridine | Deficiencies in the firm's conditions and controls | Oral | Unknown |

|

2016 [89]* |

Human chorionic gonadotropin | 6 | Unknown | Unknown | MN | Weight loss clinic | Commercial formulation not available | Mycobacterium chelonae | Unknown | Intramuscular injection | Soft tissue infection (6) |

|

2017 [78]* |

Triamcinolone and moxifloxacin | 43 | Unknown | TX | TX | Surgical center | Commercial formulation not available | Unknown | Unknown | Intravitreal injection | Vision loss, macular swelling, retinal degeneration |

|

2019 [76]* |

Bevacizumab | 4 | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Commercial formulation not available | Granulicatella adiacens | Unknown | Intravitreal | Endophthalmitis (4) |

|

2019 [90]* |

Glutathione | 7 | Unknown | AL | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unspecified endotoxin | Unknown | Intravenous injection | Various including vomiting, dyspnea |

*Denotes contamination error occurring after 2013 Compounding Quality Act

Supplemental Table 2.

Supratherapeutic and subtherapeutic compounding errors

| Year Reported (Citation) |

Patients (Split As Able) | Age (Years) | Substance and Dose (When Available) | Reason for Compounding | Cause of Error | Supra- / Subtherapeutic Ingredient | Person Administering Medication | Route of Administration | Clinical Course |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1997 [105] |

1 | 55 | Atropine 0.25 mg compounded into suppository also containing ergotamine tartrate and caffeine | Combination of multiple active ingredients | Dosage increased by order of magnitude | Supratherapeutic atropine | Self | PR | Anticholinergic toxidrome, “comatose state” for 48 h, suppositories contained 25 mg atropine instead of 0.25 mg. |

|

2001 [93] |

1 | 5 |

Clonidine 0.025–0.05 mg (0.5–1 mL of 0.05 mg/mL suspension) |

Commercial formulation not available | Unknown source of error. Concentration dispensed 1000x greater than prescribed. | Supratherapeutic clonidine | Family/Friend | PO, liquid | Decreased mental status, bradycardia, bradypnea requiring ICU admission, multiple doses of atropine, naloxone infusion. Discharged at baseline after 42 h. Testing of clonidine suspension confirmed 1000x concentration error. |

|

2001 [111] |

1 | 1 month | Phenytoin | To correct for a prescribed formulation no longer available | Mathematical error while calculating dosage resulted in prescription of 40 mg TID instead of 15 mg TID | Supratherapeutic phenytoin | Family/Friend | PO, liquid | Abdominal distention, decreased mental status, PICU admission. Presenting phenytoin level 91.8 mg/L. Course complicated by impaired phenytoin elimination due to empirically administered antibiotics (ampicillin and cefotaxime). Patient discharged at baseline after 7 days. Dosage error confirmed with compounding pharmacy. |

|

2002 [94] |

2 | 9 |

Clonidine 0.05 mg (2 mL of 0.025 mg/mL suspension) |

Commercial formulation not available | Found to be 87x the prescribed dose. | Supratherapeutic clonidine | Family/Friend | PO, liquid | Headache, lethargy, ataxia, urinary incontinence, bradycardia requiring neuroimaging and admission. Discharged after one day. |

| 10 |

Clonidine 0.1 mg QAM and 0.05 mg QPM |

Commercial formulation not available | Unknown source of error. Found to be 10x the prescribed dose. | Supratherapeutic clonidine | Family/Friend | PO, capsule | Headache, somnolence, bradycardia, and hypotension requiring fluid resuscitation, atropine, ICU admission. Discharged after one day. | ||

|

2007 [91] |

3 | 77 | Injectable Colchicine | Commercial formulation not available | Injectable colchicine prepared at 8x the intended concentration. | Supratherapeutic colchicine | Infusion Center | IV | Received compounded colchicine for chronic back pain at a naturopathic clinic and at home. Developed acute onset vomiting and hypotension, developed multisystem organ failure and died on hospital day 1. Postmortem colchicine level 44 ng/mL (reference level < 5 ng/mL). |

| 56 | Injectable Colchicine | Commercial formulation not available | Unknown source of error. Batch of injectable colchicine reportedly prepared at 8x the intended concentration. | Supratherapeutic colchicine | Infusion Center | IV |

Received compounded colchicine for chronic back pain at a naturopathic clinic. Developed acute onset vomiting, diarrhea, and chest pain. She developed multisystem organ failure, was intubated, and died on hospital day 3. Postmortem colchicine level 32 ng/mL (reference level < 5 ng/mL). |

||

| 55 | Injectable Colchicine | Commercial formulation not available | Unknown source of error. Batch of injectable colchicine reportedly prepared at 8x the intended concentration. | Supratherapeutic colchicine | Infusion Center | IV | Received compounded colchicine at a naturopathic clinic from the same lot as two confirmed deaths from colchicine toxicity. He developed vomiting, diarrhea, and chest pain within one hour of infusion. He died within 24 h of admission. No autopsy was performed and no colchicine levels were collected. | ||

|

2007 [92] |

9 | Unknown |

Tacrolimus 0.5 mg/mL solution |

Facilitate ingestion in pediatric population | Solutions 10x less concentrated than intended | Subtherapeutic tacrolimus | Family/friend | PO, liquid | 9 pediatric patients with sudden decreases in serum tacrolimus levels. One suffered grade II graft versus host disease, one suffered mild rejection. |

|

2009 [101] |

2 | 49 |

Liothyronine 7.5 mcg tablets |

Commercial formulation not available | Unknown source of error. | Supratherapeutic liothyronine | Self | PO, tablet | Altered mental status, vomiting, headaches, palpitations, intubated. TSH undetectable, normal free T4, total T3 of 8523 ng/dL (upper reference limit of 170 ng/dL). Outcome unknown. Laboratory analysis found the tablets contained 6264 mcg of liothyronine instead of 7.5 mcg. |

| 66 |

Liothyronine 7.5 mcg tablets |

Commercial formulation not available | Unknown source of error. | Supratherapeutic liothyronine | Self | PO, tablet | Diaphoresis, palpitations, shortness of breath requiring esmolol infusion and intubation. TSH, free T4 low, total T3 8249 ng/dL (upper reference limit of 170 ng/dL). Outcome unknown. Laboratory analysis found the tablets contained 7234 mcg of liothyronine instead of 7.5 mcg. | ||

|

2009 [95] |

1 | 3 |

Clonidine 0.1 mg (1 mL of 0.1 mg/mL concentration) |

To facilitate ingestion in pediatric patient | Unknown source of error | Supratherapeutic clonidine | Family/Friend | PO, liquid | Decreased mental status and bradypnea requiring supplemental oxygen. Serum clonidine level 18 h after last dose 300 ng/mL (reference range 0.5–4.5 ng/mL). Compounding pharmacy records showed correct dosage. Prescription was for 30 days, but was empty on day 19. Patient improved and discharged on day 3. |

|

2010 [98] |

2 | 47 | 4-Aminopyridine | Commercial formulation not available | Unknown source of error |

Supratherapeutic 4-Aminopyridine |

Self | PO, capsule | After taking first dose from newly compounded prescription, patient developed diaphoresis, rigors, and akathisia which self-resolved. No analysis of the medication was performed. |

| 57 | 4-Aminopyridine | Commercial formulation not available | Unknown source of error |

Supratherapeutic 4-Aminopyridine |

Self | PO, capsule | After taking first dose from newly compounded prescription, patient developed akathisia, ocular dystonia, clonus, confusion, and tachycardia which self-resolved. Analysis of the medication showed normal dosage but an impaired release mechanism. | ||

|

2011 [102] |

1 | 43 | Liothyronine 3 mcg | Commercial formulation not available | Capsules contained 1.3 mg liothryronine each. | Supratherapeutic liothyronine | Self | PO, capsule | Thyrotoxicosis complicated by anxiety, vomiting, diarrhea, tachycardia requiring admission, IV hydration, beta-blockade. Discharged after 3 days. |

|

2011 [99] |

1 | 42 |

4-aminopyridine 10 mg capsules |

Commercial formulation not available | Concentration dispensed was 10x greater than prescribed. | Supratherapeutic 4-Aminopyridine | Self | PO, capsule | Agitated delirium, status epilepticus, intubated. Developed hypertensive intracranial hemorrhage, recurrent respiratory failure requiring reintubation, central line associated blood stream infection, upper gastrointestinal bleed, PE. Discharged with persistent memory loss. Laboratory analysis confirms 10-fold supratherapeutic dosage of 4-aminopyridine. |

|

2012 [107] |

1 | 4 |

Atenolol 8.5 mg (4.25 mL of 2 mg/mL suspension) |

Commercial formulation not available | Laboratory analysis showed increased drug concentration and flocculation of the drug at the bottom of the bottle. | Supratherapeutic atenolol | Family/Friend | PO, liquid | Asymptomatic complete heart block noted at routine electrophysiology appointment for supraventricular tachycardia. Admitted to the hospital and discharged with a normal sinus rhythm after 12 h. Laboratory analysis showed supratherapeutic drug concentrations. |

|

2012 [108] |

1 | 9 months |

Flecainide 21 mg (4 mL of 5 mg/mL suspension) |

Commercial formulation not available | Initially on 15 mg flecainide dose in 5 mg/mL suspension. Compounding pharmacy converted medication to 20 mg/mL suspension instead without prescriber being made aware. When patient’s family was told to increase the dose to 20 mg by PCP, patient took 4 mL of the 20 mg/mL suspension. | Supratherapeutic flecainide | Family/Friend | PO, liquid | Lethargy and fussiness, found to be in intermittent ventricular tachycardia requiring ICU admission and sodium bicarbonate infusion. |

|

2013 [100] |

1 | 55 |

4-Aminopyridine 12.5 mg BID |

Commercial formulation not available | Unknown source of error. Found to be 10x the prescribed dose. | Supratherapeutic 4-aminopyridine | Self | PO, capsule | Acute onset agitated delirium after first two doses of new 4-aminopyridine prescription with associated status epilepticus and pulmonary edema requiring intubation, sedation, diuresis, and ICU admission. Discharged after 5 days. Laboratory analysis showed that capsules contained 127 mg of 4-aminopyridine instead of the prescribed 12.5 mg. |

|

2013 [96] |

1 | 7 |

Clonidine 0.05 mg (2.5 mL of 0.1 mg / 5 mL suspension) |

Presumed to facilitate ingestion in pediatric patient | Inadvertently compounded with 1000x increased concentration of clonidine | Supratherapeutic Clonidine | Family/Friend | PO, liquid | Sedation, hypopnea requiring intubation complicated by secondary infection. Discharged at baseline after 9 days. |

|

2014 [110]* |

1 | 5 months | Pyrimethamine | Commercial formulation not available | Incorrectly compounded to contain 94 mg/mL instead of the 2 mg/mL which was prescribed | Supratherapeutic pyrimethamine | Family/Friend | PO, liquid | Irritabiilty and tonic-clonic seizure × 2. 18-h following final dose, blood concentration 3.8 mcg/mL (upper limit therapeutic window is 0.4). |

|

2016 [104]* |

3 | N/A | Morphine | Commercial formulation not available | Medications distributed prior to confirmatory potency testing. | Supratherapeutic | Healthcare Setting | IV | 3 pediatric patients received morphine and suffered undescribed adverse events. One required naloxone and ICU. Morphine found to be 2500x more potent than labeled. |

|

2017 [103]* |

1 | 53 | liothyronine 25 mcg | Commercial formulation not available | Pharmacy acknowledged “releas[ing] compounded thyroid replacement medications with ‘increased amounts of thyroid hormone.’“ | Supratherapeutic liothyronine | Self | PO, capsule | Vomiting, aphasia, altered mental status with undetectable TSH, normal free T4, and a free T3 of 15 ng/dL (reference range 2.0–3.5 ng/dL). Discharged after 7 days. Re-presented new-onset agitated delirium and atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response with similarly isolated increase in free T3. Required intubation and admission to the ICU, treated with medication and plasma exchange, discharged after 6 days. |

|

2018 [109]* |

1 | 20 months |

Hydrocortisone 1.67 mg |

Commercial formulation not available | Hydrocortisone 5-times greater concentration than intended. | Supratherapeutic hydrocortisone | Family/Friend | PO, capsule | Patient on hydrocortisone and fludrocortisone for 21-hydroxylase deficiency congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Growth deceleration, weight gain, irritability, plethora, excess body hair noted between 6 months and 20 months of life. Negative workup for adrenal mass. Once changed off supratherapeutic hydrocortisone, symptoms resolved. |

|

2019 [106]* |

1 | 65 |

GI Cocktail: Atropine Sulfate 1 mg / Lidocaine 2% / “Antacid” |

Combination of multiple active ingredients | Pharmacy added atropine in 1 mg/mL concentration rather than 1 mg/bottle total | supratherapeutic atropine | Self | PO, liquid | Anticholinergic toxicity including agitated delirium requiring intubation. Discharged after 3 days. |

|

2020 [97]* |

1 | 12 |

Clonidine 0.2 mg (2.2 mL of 0.09 mg/mL solution) |

To facilitate ingestion in pediatric patient | Unknown source of error, however clonidine confirmed to be concentration of 0.72 mg/mL, leading to total ingestion of 1.58 mg | Supratherapeutic Clonidine | Family/Friend | PO, liquid | Sedation, bradycardia, and hypotension requiring atropine. Discharged after 1 day. |

*Denotes contamination error occurring after 2013 Compounding Quality Act

Supplemental Table 3.

Compounding pharmacy errors without documented patient harm.

| Pharmacy Involved and Year Reported (Citation) |

Event | Medication | Documented Adverse Events | Pharmacy Action |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

The Compounding Shop 2013 [124] |

Through unknown means, FDA identified that compounded inhaled budesonide was contaminated with fungus | Budesonide | None | Recall recommended, not initiated |

|

Unknown Pharmacy 2013 [112] |

1309 potential in-hospital exposure exposures to magnesium sulfate contaminated with multiple fungal species, no documented infections | Magnesium Sulfate | None | Unknown |

|

Downing Labs, 2014 [125]* |

On inspection, FDA identified insufficient sterility measures at compounding facility | Multiple | None | No recall |

|

Medistat RX 2015 [126]* |

On inspection, FDA identified insufficient sterility measures at compounding facility | Multiple | None | Voluntary recall |

|

Qualgen 2015 [127]* |

On inspection, FDA identified insufficient sterility measures at compounding facility | Multiple | None | Recall recommended, not initiated |

|

Glades 2015 [114]* |

FDA notified of “several” adverse events involving supratherapeutic Vitamin D; events not documented or enumerated | Vitamin D3 | Unknown | Voluntary recall |

|

Medaus 2016 [128]* |

On inspection, FDA identified insufficient sterility measures at compounding facility | Multiple | None | Ordered to cease sterile pharmaceutical compounding, did not comply with recommendation for recall |

|

Pharmakon, 2016 [129]* |

On inspection, FDA identified insufficient sterility measures at compounding facility | Multiple | None | Voluntary recall |

|

Atlantic Pharmacy 2017 [130]* |

On inspection, FDA identified insufficient sterility measures at compounding facility | Multiple | None | Recall recommended, not initiated |

|

Coastal Meds 2018 [131]* |

On inspection, FDA identified insufficient sterility measures at compounding facility | Multiple | None | Voluntary recall |

|

Ranier’s Rx 2018 [132]* |

On inspection, FDA identified insufficient sterility measures at compounding facility | Multiple | None | Voluntary recall |

|

Pharm D 2018 [133]* |

On inspection, FDA identified insufficient sterility measures at compounding facility | Multiple | None | Partial voluntary recall |

|

Promise Pharmacy 2018 [134]* |

On inspection, FDA identified insufficient sterility measures at compounding facility | Multiple | None | Partial voluntary recall |

|

Infusion Options 2019 [135]* |

On inspection, FDA identified insufficient sterility measures at compounding facility | Multiple | None | Voluntary recall |

|

AmEx Pharmacy 2019 [136]* |

On inspection, FDA identified insufficient sterility measures at compounding facility | Multiple | None | Voluntary recall |

*Denotes contamination error occurring after 2013 Compounding Quality Act

Table 1 is a summary of the 27 included contamination errors. With 1119 patients over 27 errors, the median number of patients affected per error is 8. The mean number of patients affected per error is 41; however, by excluding Framingham, that number is 14. With 81 deaths over 27 errors, the mean number of fatalities per error is 3; however, excluding Framingham drops that number to less than 1 (0.65). The median number of deaths per error is 0. Five out of the 27 contamination errors were from intraarticular (including epidural) steroids, and eight of 27 were from medications injected intravitreally. A total of 25 of the 27 errors were from medications administered parenterally, in healthcare settings. Three of 27 were from toxic contamination rather than microbiologic contamination. Interestingly, six of 27 errors with documented adverse outcomes occurred following the CQA.

Table 1.

Summary of contamination errors.

| Medication | Number | Route of administration | Location of administration | Type of contaminant | Deaths |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intraarticular steroids | |||||

| Betamethasone | 11 patients, 1 error [63] | Epidural and joint injection | Healthcare setting | Microbiologic | 3 |

| Methylprednisolone | 787 patients, 4 errors [6, 62, 64–67] | Epidural, intraarticular, intramuscular | Healthcare setting | Microbiologic | 65 |

| Analgesics | |||||

| Morphine with clonidine, bupivacaine | 8 patients, 1 error [68] | Intrathecal | Healthcare setting | Methadone, ethanol, methanol | 0 |

| Fentanyl | 15 patients, 2 errors [69, 70] | Intravenous | Healthcare setting | Microbiologic | 1 |

| Ophthalmologic agents | |||||

| Tryptan blue | 6 patients, 1 error [71] | Intravitreal | Healthcare setting | Microbiologic | 0 |

| Bevacizumab | 34 patients, 5 errors [72–76] | Intravitreal | Healthcare setting | Microbiologic | 0 |

| Brilliant blue green & triamcinolone | 47 patients, 1 error [77] | Intravitreal | Healthcare setting | Microbiologic | 0 |

| Triamcinolone & moxifloxacin | 43 patients, 1 error [78] | Intravitreal | Healthcare setting | Microbiologic | 0 |

| Heparin-vancomycin solution | 2 patients, 1 error [79] | Intravenous | Healthcare setting | Microbiologic | 0 |

| Cardioplegia solution | 11 patients, 1 error [80, 81] | Coronary infusion | Healthcare setting | Microbiologic | 3 |

| Heparin-saline solution | 80 patients, 1 error [82] | Intravenous | Healthcare setting | Microbiologic | 0 |

| Magnesium sulfate | 19 patients, 1 error [83] | Intravenous | Healthcare setting | Microbiologic | 0 |

| Parenteral nutrition | 19 patients, 1 error [84] | Intravenous | Healthcare setting | Microbiologic | 9 |

| Methylcobalamin | 6 patients, 1 error [85] | Intravenous | Healthcare setting | Microbiologic | 0 |

| Calcium gluconate | 15 patients, 1 error [86] | Intravenous | Healthcare setting | Microbiologic | 0 |

| Omeprazole | 1 patient, 1 error [87] | Oral | Home | Baclofen | 0 |

| Biotin | 2 patients, 1 error [88] | Oral | Unknown | 4-aminopyridine | 0 |

| Human chorionic gonadotropin | 6 patients, 1 error [89] | Intramuscular | Healthcare setting | Microbiologic | 0 |

| Glutathione | 7 patients, 1 error [90] | Intravenous | Healthcare setting | Microbiologic | 0 |

| Total | 1119 patients, 27 errors | 81 deaths | |||

Table 2 is a summary of the 21 included sub- and supratherapeutic errors. One report describes a subtherapeutic error affecting 9 pediatric patients who were on post-transplant immunosuppression with tacrolimus. The remaining 20 reports involved errors of supratherapeutic drug concentrations; they affected a total of 27 patients, of which 14 (52%) were pediatric. Of the 36 total patients affected by concentration errors, 23 (64%) were pediatric and 3 (8%) were over the age of 65 years. Three patients died, all of whom received supratherapeutic intravenous colchicine at an alternative medicine infusion clinic for chronic back pain [91].

Table 2.

Summary of subtherapeutic and supratherapeutic error.

| Medication | Number | Patient age < 18 years | Patient age ≥ 65 years | Administered at home | ICU admission | Deaths |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tacrolimus | 9 patients, 1 error [93] | 9/9 | 0/9 | 9/9 | Unknown | Unknown |

| Clonidine | 6 patients, 5 errors [106–110] | 6/6 | 0/6 | 6/6 | 3 | 0 |

| 4-Aminopyridine | 4 patients, 3 errors [111–113] | 0/4 | 0/4 | 4/4 | 2 | 0 |

| Liothyronine | 4 patients, 3 errors [114–116] | 0/4 | 1/4 | 4/4 | 3 | 0 |

| Colchicine | 3 patients, 1 error [91] | 0/3 | 1/3 | 0/3 | 3 | 3 |

| Morphine | 3 patients, 1 error [95] | 3/3 | 0/3 | 0/3 | 1 | 0 |

| Atropine | 2 patients, 2 errors [117, 118] | 0/2 | 1/2 | 2/2 | 1 | 0 |

| Atenolol | 1 patient, 1 error [119] | 1/1 | 0/1 | 1/1 | 0 | 0 |

| Flecainide | 1 patient, 1 error [120] | 1/1 | 0/1 | 1/1 | 1 | 0 |

| Hydrocortisone | 1 patient, 1 error [121] | 1/1 | 0/1 | 1/1 | 0 | 0 |

| Pyrimethamine | 1 patient, 1 error [122] | 1/1 | 0/1 | 1/1 | 0 | 0 |

| Phenytoin | 1 patient, 1 error [123] | 1/1 | 0/1 | 1/1 | 1 | 0 |

| Total | 36 patients, 21 errors | 23 patients, 11 errors | 3 patients, 3 errors | 30/36 | 15/27* | 3/27* |

*Number of ICU admissions and deaths from 9 tacrolimus patients unknown therefore not included

Appended to this article are Appendix Tables 3, 4, 5, which respectively catalog all contamination errors causing patient harm, all sub- and suprapotency errors causing patient harm, and all potential compounding errors identified and rectified before patient harm occurred. Of the 15 potential errors identified before patient harm occurred, 13 came after the enactment of the CQA.

Discussion

In this study, we separated compounding errors into the categories of contamination, suprapotency, and subpotency. We found that medications with contamination errors are frequently (1) bulk-produced and distributed, (2) used parenterally, and (3) administered by physicians. Because of their parenteral administration, medications contaminated with otherwise benign environmental flora are able to disseminate throughout the body and cause the devastating outcomes documented here. Furthermore, because contamination errors are often associated with larger—even multistate—distribution networks, the reach of their impact is large.

Framingham was the archetypal contamination error. It woke much of the medical and lay communities to the potential dangers of compounding. It inspired the federal government to enact the CQA in 2013 and create an entirely new form of compounding facility—the outsourcing facility—to attempt to regulate the subsection of pharmacies who were bulk-compounding medications not available (or not available cheaply) through commercial channels, and who exported those medications across state lines to be used on countless patients in several healthcare settings. We do not have FDA alert archives dating prior to 2010, but we have identified over a dozen instances post-CQA where FDA inspections have identified outsourcing facilities at risk for distributing contaminated medications despite their expected adherence to CGMP standards. While this FDA oversight is clearly needed, it is likely not sufficiently robust. For example, no budgetary allocation was initially made to support oversight in the CQA’s establishment of outsourcing facilities [46]. FDA Commissioner Scott Gottleib, in 2018 Congressional testimony, highlighted the funding struggles affecting oversight, stating “I don’t want to get too deep into the resource question… [b]ut this is a program where we do operate by in some cases begging, borrowing, and stealing from... other parts of the agency.” [45]

Certainly, contamination has persisted despite the CQA and the FDA’s efforts to oversee outsourcing facilities. Given this ongoing concern, the medical community must bear some of the responsibility for reducing the number of medications manufactured in substandard environments. It should be the expected standard for healthcare practices to purchase exclusively from compounding pharmacies strictly adherent to CGMP standards and formally approved as outsourcing facilities by the FDA. Leading expert Outterson referenced the potential for this approach in 2014 [46], and it is unclear how purchasers have responded. While these policies may be more expensive; the physical, ethical, and even financial [92] consequences of purchasing compounded medications from organizations not sufficiently invested in safety are clearly documented here.

Subpotency and suprapotency can be considered as the single category of errors of concentration, as the sources and scope of concentration errors are largely similar. Our findings demonstrate that subpotency is largely not a reportable issue, but that does not mean it is not a danger. As an example, beyond the cited series of subtherapeutic tacrolimus concentrations [93], another case series (excluded for location outside the US) identifies dozens of patients who received subtherapeutic chemotherapy treatments [94]. These subtherapeutic errors are difficult to capture. Identification must be done during routine serum testing, as occurred with the tacrolimus series; or on the supply side, as occurred with the chemotherapy series. When considering subtherapeutic and supratherapeutic errors together as errors of concentration, we found a somewhat different pattern than that which we identified amongst errors of contamination. The concentration errors we were able to identify, with a few notable exceptions [95, 96], were caused by traditional compounding pharmacies. These pharmacies, labeled as 503A pharmacies under the CQA, are limited in their scope to producing compounded medications only after an individual prescription is in-hand. Per the CQA, 503A pharmacies are still solely regulated by state boards of pharmacy, meaning that oversight is patchwork across the US. Many concentration errors are of orders of magnitude, suggesting that simple mathematical and measurement mistakes are to blame. In addition to hoping that states will implement greater oversight of these 503A pharmacies, we call on the pharmacy industry to emphasize and standardize compounding training amongst its students and even consider a mandatory credential before allowing a pharmacist or pharmacy technician to compound a medication [26, 97–99].

It is worth noting that 4-aminopyridine and liothyronine are fairly uncommon medications, however they accounted for a large number of compounding concentration errors. There is nothing particularly special about these medications which make them prone to concentration errors, except for the fact that they are not readily commercially available, and so they must be compounded. The prescribers of these medications need to carefully consider the benefits and risks of prescribing a treatment which requires compounding; especially when the risks are so great (status epilepticus with 4-aminopyridine and thyrotoxicosis with liothyronine). Liothyronine, in particular, has had its clinical utility recently questioned. For example, the National Health Service (UK) has recently called on general practitioners to stop prescribing liothyronine without specialist consultation, as most patients benefit equally from commercially prepared levothyroxine [100]. Given the risks of inadvertent overdose due to compounding errors, providers must consider commercially available alternatives whenever able. In fact, it has been questioned whether providers who knowingly prescribe a compounded medication despite commercially available alternatives might be legally liable for any harm resulting from compounding errors [101]. At the very least, it is incumbent on prescribers as well as pharmacists to educate their patients on the risks of taking a compounded medication—both from errors in concentration and contamination—and to instruct them on when to present to a healthcare provider. Additionally, practitioners must be aware of their patients’ medication lists, and consider a possible compounding error as a cause of medical illness. Notably, we found that the majority of concentration errors were made in pediatric and geriatric patients, vulnerable populations who are already at increased risk of providers failing to diagnose toxicity from prescription medications.

In 2020 and beyond, we anticipate the demand for compounding to only increase. The number of novel therapeutics continues to rise rapidly, as do their approved routes of administration. The anti-angiogenesis medication bevacizumab is a classic example; it is commercially manufactured but is frequently compounded into smaller aliquots for intravitreal administration. As we have seen, this process has unfortunately resulted in multiple outbreaks of endophthalmitis [72–76]. Furthermore, regional and global disasters have recently resulted in significant pharmaceutical supply chain issues. Examples of this phenomenon include Hurricane Maria’s impact on Puerto Rican manufacturers in 2017 and the COVID-19 pandemic [120–123]. These disruptions place increased demand on alternative means of supply, including via pharmaceutical compounding. In fact, the COVID-19 pandemic and its associated drug shortages has already resulted in the loosening of FDA restrictions, including allowing outsourcing facilities to compound copies of commercially available drugs for hospital use [21].

Our study has its limitations. While we made every effort to capture published cases of compounding errors, it is possible that our search criteria missed some cases that would have impacted our analyses. While we also strove to review less-traditional sources, including conference abstracts and FDA alerts, we are not free of publication bias and are at risk for having excluded compounding errors not associated with adverse events, or with very small numbers of patients affected. Similarly, it must be noted that compounding errors can only be identified following adverse events, laboratory screening, or industry or governmental report. Even once identified, we were dependent on the publication of the error in order to capture it here. As such, we are likely underreporting the frequency with which compounding errors occur.

Conclusions

Compounding is more relevant than ever. Appreciating that the need for compounding is unlikely to diminish in the near future, we can only re-emphasize the critical nature of our recommendations for the federal and state governments to fully fund the oversight of outsourcing facilities, for healthcare practices to refuse medications compounded without strict adherence to CGMP and FDA regulations, for pharmacy schools to expand compounding training and certification, and for physicians to think critically about the risks of prescribing medications that are not commercially produced. Conversely, we must remain aware that compounding pharmacies frequently provide an essential service and poorly calibrated regulations may contribute to issues of access. Ultimately, medical providers must remain vigilant, especially when caring for members of vulnerable populations, and consider the possibility that a new-onset illness may very well be the result of a compounding error.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of Shannon Manzi, PharmD, Assistant Professor of Pediatrics at Harvard Medical School and Manager of the Boston Children’s Hospital Emergency Department and Intensive Care Unit Pharmacy Services, to this manuscript.

Appendix

Author Contributions

Study concept and design: CJW, JDW, AMS, MMB

Acquisition of the data: CJW, JDW

Analysis and interpretation of the data: CJW, JDW, AMS, MMB

Drafting of the manuscript: CJW, JDW, AMS, MMB

Critical revision of the manuscript: CJW, JDW, AMS, MMB

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

CJW, JDW, and AMS report no conflicts of interest. MMB reports that she is the Pediatric Toxicology Section Editor at UpToDate.

Footnotes

Prior Presentations: None

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Young D. Outsourced compounding can be problematic. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2002;59:2261–2264. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/59.23.2261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alcorn T. Meningitis outbreak reveals gaps in US drug regulation. Lancet. 2012;380(9853):1543–1544. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(12)61864-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Outterson K. Regulating compounding pharmacies after NECC. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(21):1969–1972. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1212667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Teshome BF, Reveles KR, Lee GC, Ryan L, Frei CR. How gaps in regulation of compounding pharmacy set the stage for a multistate fungal meningitis outbreak. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2014;54(4):441–445. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2014.14011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kainer MA, Reagan DR, Nguyen DB, Wiese AD, Wise ME, Ward J, Park BJ, Kanago ML, Baumblatt J, Schaefer MK, Berger BE, Marder EP, Min JY, Dunn JR, Smith RM, Dreyzehner J, Jones TF. Fungal infections associated with contaminated methylprednisolone in Tennessee. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(23):2194–2203. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1212972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith RM, Schaefer MK, Kainer MA, Wise M, Finks J, Duwve J, Fontaine E, Chu A, Carothers B, Reilly A, Fiedler J, Wiese AD, Feaster C, Gibson L, Griese S, Purfield A, Cleveland AA, Benedict K, Harris JR, Brandt ME, Blau D, Jernigan J, Weber JT, Park BJ. Fungal infections associated with contaminated methylprednisolone injections. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(17):1598–1609. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1213978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Human drug compounding. U.S. Food & Drug Administration. December 19, 2019. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/guidance-compliance-regulatory-information/human-drug-compounding. Accessed May 31, 2020.

- 8.Chapter 795: pharmaceutical compounding - nonsterile preparations. United States Pharmacopeia. January 1, 2014. https://www.uspnf.com/sites/default/files/usp_pdf/EN/USPNF/revisions/gc795.pdf. Accessed June 29, 2020. [PubMed]

- 9.Gudeman J, Jozwiakowski M, Chollet J, Randell M. Potential risks of pharmacy compounding. Drugs RD. 2013;13(1):1–8. doi: 10.1007/s40268-013-0005-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guidance For Entities Considering Whether to Register As Outsourcing Facilities Under Section 503B of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. August 2015. https://www.fda.gov/files/drugs/published/Guidance-For-Entities-Considering-Whether-to-Register-As-Outsourcing-Facilities-Under-Section-503B-of-the-Federal-Food%2D%2DDrug%2D%2Dand-Cosmetic-Act.pdf. Accessed June 29, 2020.

- 11.Williams NT. Medication administration through enteral feeding tubes. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2008;65(24):2347–2357. doi: 10.2146/ajhp080155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cimolai N. Penicillin VK oral suspension. Can Med Assoc J. 2015;187(6):439.2–43439. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.115-0025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Misiewicz Runyon A, So T-Y. The use of ketogenic diet in pediatric patients with epilepsy. ISRN Pediatr. 2012;2012:1–10. doi: 10.5402/2012/263139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang X, Fang P, Xiang D, Yang Y. Topical treatments for diabetic neuropathic pain (review) Exp Ther Med. 2019;17:1963–1976. doi: 10.3892/etm.2019.7173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Younis US, Fazel M, Myrdal PB. Characterization of tetracycline hydrochloride compounded in a miracle mouthwash formulation. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2019;20(5):1–8. doi: 10.1208/s12249-019-1388-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DeLegge MH. Parenteral nutrition therapy over the next 5–10 years: where are we heading? J Parenter Enter Nutr. 2012;36(Supplement 2):56S–61S. doi: 10.1177/0148607111435333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gilbert RE, Kozak MC, Dobish RB, Bourrier VC, Koke PM, Kukreti V, Logan HA, Easty AC, Trbovich PL. Intravenous chemotherapy compounding errors in a follow-up pan-Canadian observational study. J Oncol Pract. 2018;14(5):e295–e303. doi: 10.1200/JOP.17.00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sklenar Z, Scigel V, Horackova K, Slanar O. Compounded preparations with nystatin for oral and oromucosal administration. Acta Poloniae Pharmaceutica - Drug Research. 2013;70(4):759–762. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guharoy R, Noviasky J, Haydar Z, Fakih MG, Hartman C. Compounding pharmacy conundrum. Chest. 2013;143(4):896–900. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-0212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barrera K, McNicoll C, Sangji N. Drug shortages: the invisible epidemic. Bulletin of the American College of Surgeons November 1, 2018. https://bulletin.facs.org/2018/11/drug-shortages-the-invisible-epidemic/. Accessed June 29, 2020.

- 21.Temporary policy for compounding of certain drugs for hospitalized patients by pharmacy compounders not registered as outsourcing facilities during the COVID-19 public health emergency (revised): guidance for industry. United States Food and Drug Administration. May 21, 2020. https://www.fda.gov/media/137125/download. Accessed June 29, 2020.

- 22.Compounding activities: COVID-19. U.S. Food & Drug Administration. April 7, 2020. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/coronavirus-covid-19-drugs/compounding-activities-covid-19. Accessed June 29, 2020.

- 23.Chapter 797: pharmaceutical compounding - sterile preparations. United States Pharmacopeia. June 1, 2008. https://www.sefh.es/fichadjuntos/USP797GC.pdf. Accessed June 29, 2020.

- 24.Allen L. The art, Science, and Technology of Pharmaceutical Compounding. 4. Washington, DC: American Pharmacists Association; 2012. Guidelines for compounding practices; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mullarkey T. Pharmacy compounding of high-risk level products and patient safety. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2009;66(17_Supplement_5):S4–S13. doi: 10.2146/ajhp0108b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kochanowska-Karamyan AJ. Pharmaceutical compounding: the oldest, most symbolic, and still vital part of pharmacy. Int J Pharm Compd. 2016;20(5):367–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Urick BY, Meggs EV. Towards a greater professional standing: evolution of pharmacy practice and education, 1920–2020. Pharmacy. 2019;7(3):98. doi: 10.3390/pharmacy7030098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Higby GJ. The continuing evolution of American pharmacy practice, 1952–2002. J Am Pharm Assoc 1996. 2002;42(1):12–15. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Cantrell SA. Improving the quality of compounded sterile drug products: a historical perspective. Ther Innov Regul Sci. 2016;50(3):266–269. doi: 10.1177/2168479015620833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grober ED, Garbens A, Božović A, Kulasingam V, Fanipour M, Diamandis EP. Accuracy of testosterone concentrations in compounded testosterone products. J Sex Med. 2015;12(6):1381–1388. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pinkerton JV, Pickar JH. Update on medical and regulatory issues pertaining to compounded and FDA-approved drugs, including hormone therapy. Menopause. 2016;23(2):215–223. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000000523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boodoo JM. Compounding problems and compounding confusion: federal regulation of compounded drug products and the FDAMA circuit split. Am J Law Med. 2010;36:220–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Drazen JM, Curfman GD, Baden LR, Morrissey S. Compounding errors. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(25):2436–2437. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1213569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kainer M, Wiese AD, Benedict K, et al. Multistate outbreak of fungal infection associated with injection of methylprednisolone acetate solution from a single compounding pharmacy - United States, 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61(41):839–842. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Multistate outbreak of fungal meningitis and other infections. United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. October 30, 2015. https://www.cdc.gov/hai/outbreaks/meningitis.html. Accessed June 2, 2020.

- 36.Abbas KM, Dorratoltaj N, O’Dell ML, Bordwine P, Kerkering TM, Redican KJ. Clinical response, outbreak investigation, and epidemiology of the fungal meningitis epidemic in the United States: systematic review. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2016;10(1):145–151. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2015.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goldman TR. Health policy brief: regulating compounding pharmacies. Health Aff May. 2014;1.

- 38.Drug compounding: FDA has taken steps to implement compounding law, but some states and stakeholders reported challenges. United States Government Accountability Office. November 2016. https://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-17-64. Accessed June 29, 2020.

- 39.Food F. Drug, and Cosmetic Act, 21 USC §§301-399i. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nolan A. Federal authority to regulate the compounding of human drugs. Congressional Research Service April 12, 2013. https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R43038.pdf. Accessed June 29, 2020.

- 41.Food and Drug Administration Modernization Act of 1997, 21 USC § 353a (2018).

- 42.Thompson v Western States Medical Center. 535 US 357, 368–78 (2002).

- 43.The Drug Quality and Security Act, 21 USC §331-379j-62 (2018).

- 44.The Proposed Drug Quality and Security Act (H.R. 3204). Congressional Research Service. October 31, 2013. https://www.everycrsreport.com/files/20131031_R43290_b736047f7532e678fb6793b144115d837c6029a4.pdf. Accessed May 14, 2020.

- 45.Examining Implementation of the Compounding Quality Act, Hearing before the Subcommittee on Health of the House Committee on Energy and Commerce. 115th Cong, 2nd Sess (2018) (testimony of Scott Gottlieb, (former) Commissioner of FDA).

- 46.Outterson K. The drug quality and security act — mind the gaps. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(2):97–99. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1314691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.21 USC §353a (2018).

- 48.21 USC §353a(a)-(b) (2018).

- 49.21 USC §353b (2018).

- 50.Human drug compounding outsourcing facility fees. United States Food and Drug Administration. August 12, 2019. https://www.fda.gov/industry/fda-user-fee-programs/human-drug-compounding-outsourcing-facility-fees. Accessed May 25, 2020.

- 51.Palumbo FB, Rosebush LH, Zeta LM. Navigating through a complex and inconsistent regulatory framework: section 503B of the Federal Food Drug and Cosmetic Act outsourcing facilities engaged in clinical investigation. Ther Innov Regul Sci. 2016;50(3):270–278. doi: 10.1177/2168479015618695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.State oversight of drug compounding. Pew Charitable Trust. February 2018. https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/reports/2018/02/state-oversight-of-drug-compounding. Accessed May 15, 2020.

- 53.U.S. FDA. 2018 Compounding policies priorities plan. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/human-drug-compounding/ 2018-compounding-policy-priorities-plan. Published January 2018. Current as of June 21, 2018. Accessed May 25, 2020.

- 54.Human Drug Compounding Under Sections 503A and 503B of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. Fed Regist. 2020; 85 FR 28961: 28961–28965. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2020/05/14/ 2020–10336/agency-information-collection-activities-submission-for-office-of-management-and-budget-review. Accessed June 28, 2020.

- 55.21 USC § 353a(b)(3)(B)(i)-(ii) (2018).