Abstract

Diet is an important risk factor for colorectal cancer (CRC) and several dietary constituents implicated in CRC are modified by gut microbial metabolism. Microbial fermentation of dietary fiber produces short chain fatty acids, e.g., acetate, propionate, and butyrate. Dietary fiber has been shown to reduce colon tumors in animal models and, in vitro, butyrate influences cellular pathways important to cancer risk. Furthermore, work from our group suggests that the combined effects of butyrate and omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (n-3 PUFA) may enhance the chemopreventive potential of these dietary constituents. We postulate that the relatively low intakes of n-3 PUFA and fiber in Western populations and the failure to address interactions between these dietary components may explain why chemoprotective effects of n-3 PUFA and fermentable fibers have not been detected consistently in prospective cohort studies. In this review, we summarize the evidence outlining the effects of n-3 long-chain PUFA and highly fermentable fiber with respect to alterations in critical pathways important to CRC prevention, particularly intrinsic mitochondrial-mediated programmed cell death resulting from the accumulation of lipid reactive oxygen species (ferroptosis), and epigenetic programming related to lipid catabolism and beta-oxidation associated genes.

Keywords: n-3 PUFA, fermentable fiber, ferroptosis, diet interaction, colon cancer

Introduction

CRC is the third most common cancer in the U.S. [1], CRC and precursor lesions (e.g., hyperplastic and adenomatous polyps) [2], could be greatly reduced through dietary modification (i.e., increased dietary fiber intake and altered fat intake) [3]. In the 2018 Colorectal Cancer Report, part of the WCRF/AICR Continuous Update Project, the Expert Panel classified evidence supporting consumption of fiber-rich foods and CRC protection as ‘convincing’ [4], noting a 9% decrease in risk for every 10 g/d increase in fiber among 15 studies in the meta-analysis. Inconsistencies across epidemiologic studies are attributed in part to lower and narrower ranges of fiber intake in Western populations [5]. Intakes greater than the current recommendations (28 g/d for women/35 g/d for men) show robust CRC protection (RRs 0.72 to 0.90) [2,6–8]. However, less than 5% of Americans meet recommended intakes for dietary fiber (mean ~15 g/d) [2,9]. One hypothesized chemoprotective mechanism is fiber fermentation to short-chain fatty acids (SCFA), particularly butyrate, by gut microbiota [10–12]. Given the importance of fiber fermentation, consideration of fiber subtypes and variation in microbial capacity to produce butyrate [13], are important. We review evidence that fiber type in concert with other dietary factors modulates the relation between dietary fiber and CRC risk.

Several mechanisms have been hypothesized to explain how dietary fiber may reduce CRC, including a reduction in secondary bile acids, reduced intestinal transit time, and increased stool bulk [10–12]. One hypothesized chemoprotective mechanism is fiber fermentation to short-chain fatty acids (SCFA), particularly butyrate, by gut microbiota [10–12]. Butyrate is a potent histone deacetylase inhibitor[14,15] associated with reduced CRC risk [14,16–18]. Thus, dietary factors that may influence the production of butyrate are important to understand. Indeed, it is becoming increasingly apparent that modulation and consideration of fiber subtypes (i.e., soluble and insoluble or more and less fermentable) can influence the microbial interspecies competition to alter butyrate production [13,19–21]. However, given the importance of fiber fermentation as a source for butyrate, very few studies in humans have looked at fiber subtype and results have included both null [8,22,23] and inverse associations [24–27] with CRC. We hypothesize that the inconsistencies may be due in part to the interaction of other dietary factors with fiber. Therefore, in this review, we discuss evidence that fiber type in concert with other dietary factors (i.e., n-3 PUFA) modulates the relation between dietary fiber and CRC risk.

In observational studies, evidence is mixed for associations between subtypes of fat and CRC [8,28]. Omega 3 (n-3; α-linolenic acid, ALA) and omega 6 (n-6; α-linoleic acid, LA) PUFA are essential nutrients that are incorporated into tissue membranes, and have a variety of physiologic roles. Long-chain n-3 PUFA, eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), found in fish oils [29], can be produced from ALA, but the process is inefficient in humans, and there is competition with synthesis of other n-6 PUFA, which are found in much greater abundance in a typical Western diet [30]. While both are structural components and substrates of eicosanoid-related pathways, in general, PUFA derived from n-6 are pro-inflammatory whereas those produced from n-3 tend to have opposing effects [31,32]. Given the strong association between inflammation and CRC [32], higher intakes of n-3 PUFA provide biological plausibility for a chemoprotective effect [33].

As with dietary fiber, preclinical models consistently show reduced CRC risk with n-3 PUFA [34–37]. However, epidemiologic data are less consistent in part because intakes are often low and most studies do not adequately capture supplemental fish oil intake. Two meta-analyses concluded that fish intake is associated with decreased CRC risk [38,39]; however, two systematic reviews of n-3 PUFA on cancer risk qualitatively concluded that there is inadequate [40] or limited [41] evidence to suggest an association. A recent publication reported no overall association between n-3 PUFA and CRC risk among 123,529 individuals; however, in sub-site analyses, n-3 PUFA intakes were positively associated with distal colon cancer, but inversely associated with risk of rectal cancer in men [42]. Conversely, separate evaluation in the same cohort suggests that n-3 PUFA intake after CRC diagnosis may have a protective effect on survival [43]. Compared with women who consumed <0.1 g/d of marine n-3 PUFA, those who consumed >0.3 g/d had a reduced CRC-specific mortality (HR: 0.59, 95% CI: 0.35, 1.01), and those who increased their intake by at least 0.15 g/d after diagnosis had an even greater reduction (HR: 0.3; 95% CI: 0.14, 0.64, P-trend <0.001). In the VITamins And Lifestyle (VITAL) cohort (n=68,109), evaluating fish oil supplement use—where doses are often much higher than what can be obtained from diet—users on 4+ d/wk for 3+yr experienced 49% lower CRC risk than nonusers (HR = 0.51, 95% CI = 0.26–1.00; P trend = 0.06) [44]. Interestingly, CRC patients who consumed dark fish (>1/wk) after diagnosis had longer disease-free survival [45] , supporting further the need for higher doses than typically obtained with a US diet.

Interaction of Long-Chain n-3 PUFA and Dietary Fiber in Clinical Studies

Fat and fiber are two dietary components with the greatest impact on tumor development, and data support the concept that the type of fat or fiber is actually more important to tumor development than total amounts of either component [9,46–50]. Unfortunately, the effect of combinations of specific subtypes of dietary fiber and fatty acids and risk of CRC in humans is just beginning to be evaluated. This is an important consideration given their varied biologic, biochemical, and metabolic roles [8,9,48,51]. Among the nearly 97,000 Seventh Day Adventists, risk of CRC was reduced by 22% among all vegetarians combined compared to non-vegetarians, but the protection was greatest among pescovegetarians, who consumed high amounts of both fiber and n-3 PUFA-containing fish (HR: 0.57; 95% CI: 0.40, 0.82) [52]. Further, striking reciprocal changes in gut mucosal cancer risk biomarkers and microbiome were reported after African Americans were given a high-fiber, low-fat diet and rural Africans a high-fat, low-fiber Western-style diet [53]. Significantly increased butyrate production and reduced secondary bile acid concentrations were noted after the diet exchange to high-fiber, low-fat intake in African Americans [53]. A subsequent analysis in the Rotterdam prospective cohort lends support to the hypothesis that higher intakes of fat and fiber are important factors mediating the relationship between these variables. Increased risk of CRC was observed with n-3 PUFA intake when dietary fiber intakes were below the median, while fiber intakes above the median in combination with higher n-3 PUFA were associated with reduced risk [54]. Furthermore, when evaluated by food sources of n-3 PUFA, increased CRC risk was restricted to intake from non-marine sources. These mixed results for fat and fiber and CRC risk underscore the urgent need for controlled studies using standardized intakes of fat and fiber subtypes and consideration of the potential impact of the gut microbiome.

Mechanisms of Action: Fat and Fiber Interaction

We conducted a series of seminal studies using both preclinical and in vitro models looking at molecular mechanism of action and providing strong evidence for a combined effect of types of fat and fiber in relation to colon tumorigenesis. The combination of bioactive components from fish oil (i.e., DHA and EPA n-3 PUFA) and prebiotic fermentable fibers (i.e., pectin) act synergistically to protect against colon cancer, in part, by enhancing apoptosis at the base of the crypt throughout all stages (initiation, promotion and progression) of colon tumorigenesis [34,55–60]. Interestingly, the combination of these agents was i) more effective in blocking tumorigenesis compared to either compound alone; ii) more effective compared to other fat (e.g., corn oil) and fiber (e.g., cellulose); iii) protective effects were due to increased apoptosis rather than decreased cell proliferation; and iv) the same phenotype emerged in both cancer and non-cancer cells [61]. Initially, the effects of fat (fish oil or corn oil; 15 g/100 g) and fiber (pectin or cellulose; 6 g/100 g) diets with and without carcinogen for 36 wks (2x2x2x2 factorial design; n=160 rats, 10/ group) were assessed with respect to colon cancer progression and various other aspects of colonocyte physiology [34,62]. Fish oil resulted in a significantly lower proportion of animals with adenocarcinomas relative to corn oil feeding (56% vs 70%, P<0.05). While pectin led to a lower incidence (57% vs 69%; NS), the combination of fish oil and pectin compared to corn oil and cellulose led to a greater reduction than fish oil alone (51% vs 76%, P<0.05) [34]. In addition, fish oil and pectin, alone and in combination, resulted in significantly higher colonic apoptotic indices compared to corn oil or cellulose [34,63]

Butyrate, produced from fermented fiber, induces apoptosis in tumor cells- as well as T-cells, the source of colonic inflammation [64], through inhibition of histone deacetylases (HDACi) and activation of the Fas receptor-mediated extrinsic death pathway [48,62,64–66]. HDACi occurs in a concentration-dependent manner and the butyrate concentration to which colonic epithelial cells are exposed is dependent on the gut microbiome. However, the role of butyrate in the induction of colonocyte apoptosis may be a secondary consequence to its ability to promote cellular oxidation. Butyrate induces cellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) when metabolized [61,67].. This is relevant because long-chain PUFA from fish oil (e.g., DHA, EPA) incorporated into cell membranes are susceptible to oxidation due to their high degree of unsaturation [35]. Lipid peroxidation can directly trigger release of pro-apoptotic factors from mitochondria into the cytosol [51]. To study ROS generation and antioxidant response via synergy between butyrate and n-3 PUFA, rats were fed corn oil+cellulose or fish oil+pectin. Colonocytes from rats fed fish oil+pectin had increased ROS, but reduced DNA damage [55]. Importantly, this enhanced oxidative stress, in particular membrane lipid oxidation, e.g., the formation of phospholipid hydroperoxides, was associated with exponentially increased programmed cell death [55,68–70]. These findings indicate that fish oil plus fermentable fiber modulate the redox environment, promoting lipid oxidation-mediated apoptosis, thus protecting the colon against oxidative stress. Consistent with this hypothesis, combined effects of n-3 PUFA and butyrate-induced apoptosis were partially blocked by co-incubation with a mitochondrial-targeted antioxidant [71], and overexpression of glutathione peroxidase 4 (Gpx4), which catalyzes the reduction of hydrogen peroxide, organic hydroperoxides, and most specifically, lipid hydroperoxides [70]. This is particularly noteworthy, because the Gpx4-dependent peroxidation of PUFA in cell membranes has been linked to ferroptosis, a promising new mechanism to kill therapy-resistant cancers [72,73]. These novel findings suggest a regulated cell death nexus linking the metabolism of dietary fiber and n-3 PUFA, redox biology and cancer chemoprevention.

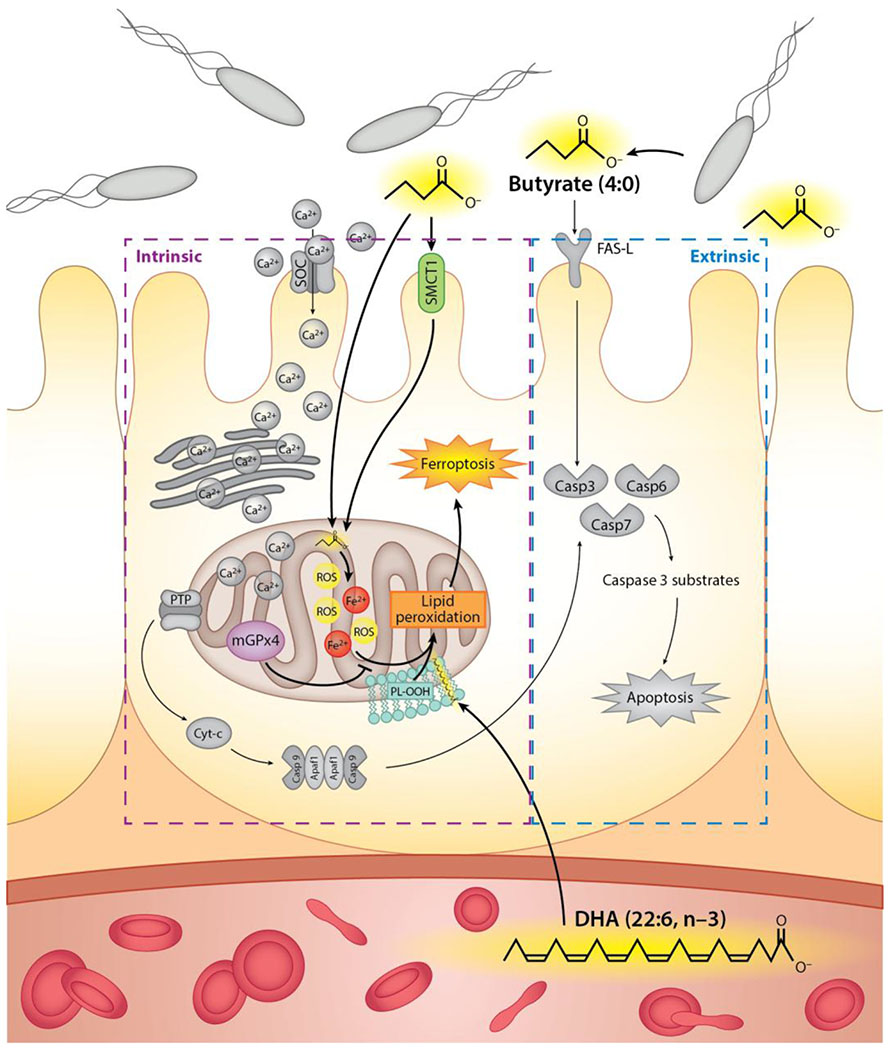

Since mitochondria play a key role in both apoptosis and necrosis by regulating energy metabolism, intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis, caspase activation and ROS release [74], we examined effects of DHA and butyrate on intracellular Ca2+ in mouse colonocytes [61]. Mitochondrial-to-cytosolic ratios were significantly increased compared to non-treated cultures; and a concomitant 43% increase in apoptosis compared to colonocytes treated with butyrate alone, but not DHA alone [61]. Complementary studies assessing whether DHA/ butyrate-induced cell death is p53-mediated, established that Ca2+ accumulation serves as the trigger for programmed cell death in a p53-independent manner. DHA (but not EPA) and butyrate uniquely modulates intracellular Ca2+ compartmentalization and channel entry to induce colonocyte apoptosis. [48,51]. These data are consistent with the hypothesis that n-3 PUFA and butyrate together, compared to butyrate alone, enhance colonocyte programmed cell death by inducing a p53-independent, lipid oxidation-sensitive, mitochondrial Ca2+-dependent (intrinsic) cell death pathway (Figure 1). Since the balance between cell proliferation and apoptosis is critical for maintaining a steady-state cell population, disruption of homeostatic mechanisms can result in clonal expansion and tumorigenesis. It is clearly established that colonic transformation of ademoma to carcinoma is associated with a progressive inhibition of apoptosis [34,75].

Figure 1. Proposed mechanisms by which supplemental n-3 PUFA and butyrate from bacterial fiber fermentation may reduce cancer risk.

n-3 PUFA + fermentable fiber will attenuate mitochondrial anti-oxidant defenses and promote colonocyte mitochondrial Ca2+ and Gpx4-dependent ferroptosis, a form of intrinsic programmed cell death. Increased butyrate exposure will also extrinsically alter cancer-related pathways in a CRC chemopreventive direction.

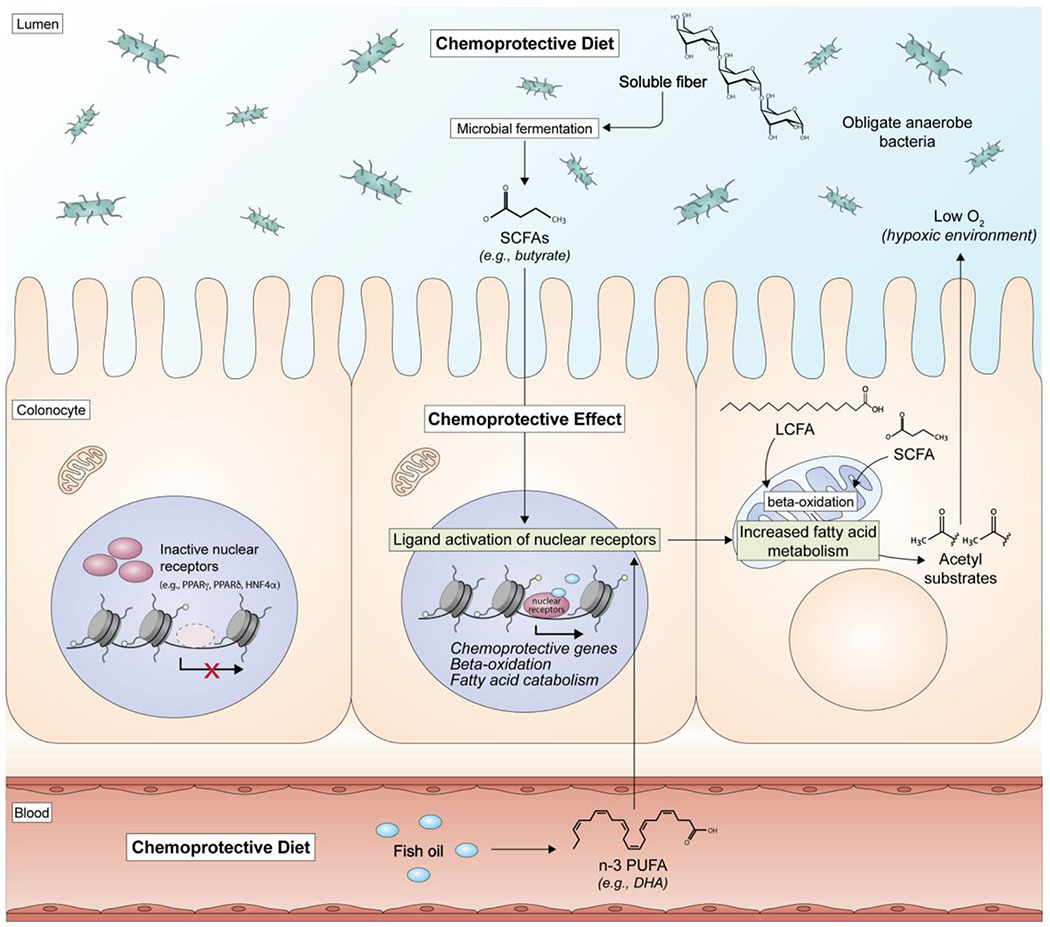

With respect to epigenetic programming, the effects of highly chemoprotective combination of fish oil and pectin on mouse colonic mucosal microRNA expression and their targets has been recently described [76]. The data indicate that this fat x fiber combination can modulate stem cell regulatory networks. In a complementary rat colon cancer progression model, the combinatorial diet (fish oil and pectin) uniquely modified global histone post-translational epigenetic programming, resulting in the upregulation of lipid catabolism and beta-oxidation associated genes [63] (Figure 2). Interestingly, emerging evidence indicates that colonocyte metabolism, e.g., mitochondrial beta-oxidation, determines the types of microbes that thrive in the gut [77,78]. Thus, dietary fat x fiber interactions may uniquely promote mechanisms that drive beta-oxidation induced hypoxia, thereby maintaining the growth of obligate anaerobic bacteria. This will help sustain a normal “healthy” symbiotic environment and stabilize mucosal barrier function [79].

Figure 2. Putative epigenetic effects of n-3 PUFA and fermentable fiber on global histone post-translational epigenetic programming in the colon.

The pescovegetarian diet (n-3 PUFA from fish and dietary fiber) upregulates EPA and DHA ligand-dependent nuclear receptors. Transcriptional events are further enhanced by the increased production of butyrate via fiber fermentation, which directly and indirectly modifies histone acetylation. These combinatorial effects enhance the mitochondrial L-carnitine shuttle, inhibit lipogenesis and promote the accumulation of acetyl CoA-dependent beta-oxidation. The enhanced mucosal beta-oxidation maintains a hypoxic environment in the gut and promotes the growth of obligate anaerobic bacteria and inhibits dysbiotic microbial expansion.

Heterogeneity in Microbial Fermentation Capacity Affects Host Response to Dietary Fiber and Fat

Diet affects CRC risk in part by contributing particular substrates (e.g., dietary fiber, phytochemicals) that result in microbial production of chemoprotective metabolites and modulation of specific gut microbial species [80]. However, these dietary effects are also modulated by the metabolic capacity of the microbial community. We showed recently that human colonic exfoliome gene expression response to a flaxseed lignan intervention depended on the composition of the microbial community at baseline prior to our intervention to modulate the production of the enterolignan, enterolactone [81]. The individuals that lacked the enterolactone microbial consortia never produced it during the intervention. Similarly, bacterial fermentation of dietary fibers and production of SCFA vary across individuals, driven partly by differences in gut microbial community structure and function [12]. Even in controlled feeding studies, where all participants receive the same food, substantial variation in fecal SCFA concentrations are reported [53,82].

A key factor in determining the availability of butyrate and setting apoptotic and other regulatory events in motion is the contribution of the gut microbiome to fiber fermentation. Types of complex carbohydrates consumed (e.g., dietary fibers, resistant starch) influence prevalence of certain consortia of gut bacteria and subsequent metabolites to which the host is exposed [83–96]. The microbiome responds rapidly to dietary interventions [97], although individual responses may differ [98–101]. Bacteria ferment fiber to SCFA, predominantly acetate, butyrate, and propionate, in a ratio of 3:1:1 [102] via metabolic pathways unique to anaerobic gut bacteria [103–106]. Butyrate producers form a functional cohort, rather than a monophyletic group, distributed across four different phyla: Firmicutes, Fusobacteria, Spirochaetes, and Bacteroidetes [107]. Butyrate is produced from fermentation via multiple pathways: the acetyl-CoA [21,108], glutarate [109–111], 4-aminobutyrate [112–114] and lysine pathways [115–117], but distribution of these pathways in the human microbiome varies [107].The dominant pathway associated with butyrate production is the acetyl-CoA pathway. The last step in conversion to butyrate across these multiple pathways is carried out by butyryl-CoA transferase (but) and butyrate kinase (buk) [107,118–120]. Acetate, often viewed as the final product of fermentation, supports syntrophy (cross-feeding) in the gut microbiome. For example, Roseburia spp. can condense acetate produced by other bacteria to produce butyrate via butyryl CoA: acetate CoA transferase and butyrate production is affected by the type of dietary fiber [121]. Vital et al [122] suggested that targeting specific human microbiome genes involved in butyrate production across these pathways gives a comprehensive picture of microbial butyrate production or “butyrogenic potential” in terms of gut resilience and a lower incidence of intestinal inflammation. These multiple pathways for bacterial production of butyrate ensure optimal butyrate availability to the host.

Methane-producing Archaea may also influence butyrate production in the gut [123]. Only a subset of healthy adult populations (~40%) harbor Archaea and among these individuals, an inverse association has been reported between fecal methanogen and butyrate concentrations [124]. Hydrogenotrophs, methanogens and eubacterial acetogens, compete for H2 produced during fiber fermentation. The methanogens use H2 to generate methane, whereas the acetogens use H2 to reduce CO2 to acetate via the acetyl-CoA pathway[125]. Because they lack butyrate kinase, these microbes can co-exist with other fermenters. Thus, the presence of methanogens may alter H2 availability and contribute to differential exposure to butyrate and indirectly to CRC risk across populations [124].

Changes in Cancer-Pathway Measures with Fish Oil and SCFA in Healthy Humans

Mechanistic investigation of diet effects on apoptosis has been conducted primarily in colon cancer cell lines; although examples of in vivo changes in normal human colon with fish oil suggest that diet effects on healthy colonic mucosa are measurable. For example, individuals with a history of adenomas received one of two dietary interventions: i) 20% total fat; and increased n-3 PUFA via dietary fish + fish oil (~100 mg EPA + 400 mg DHA/d; n=21 experimental group); or ii) 20% total fat only (n=20, comparison). After 24 mos, the apoptotic index, Bax-positive cells, and Bax/Bcl-2 ratio were significantly increased in normal mucosa among those randomized to increased n-3 PUFA, whereas no change was observed in the comparison group [126]. In patients with resected polyps, EPA (2 g/d), supplementation for 3 mos resulted in higher apoptosis at the base of the crypt in normal colonic mucosa and significantly decreased cell proliferation, while no change was noted in the control group [127]. Finally, results of a recent dietary intervention suggest that distinct fat-fiber combinations have differential effects on cell proliferation in normal colonic mucosa [53]. Individuals with colorectal adenomas also have increased crypt cell proliferation and decreased apoptosis in macroscopically normal appearing colonic mucosa [127], and progressive inhibition of apoptosis in the transformation of normal colorectal mucosa to carcinoma [75]. These findings support the importance of an “etiologic field effect” in the colon [128], and the assertion that understanding effects of diet on cancer-related pathways in normal tissue is an essential part of cancer-prevention research.

Gut Microbiome, Diet and Tumorigenesis

While most dietary fat is absorbed in the small intestine, some enters the colonic lumen. High-fat diets rich in saturated fats (Western diet) alter gut microbial composition with negative health outcomes [129–132]. In contrast, recent studies suggest that high n-3 PUFA influence the gut microbiome favorably or has no negative health effects [133,134]. Exposure to EPA and DHA increases Lactobacillus and Bifidobacteria and reduces Helicobacter and Fusobacteria nucleatum. [133–138], –important prebiotic effects given that increases in Lactobacillus and Bifidobacteria are associated with reduced inflammation [139–142]. Both Helicobacter and F. nucleatum are pathogens and n-3 PUFAs can act as antibacterial or bacteriostatic compounds. Differential susceptibility of bacteria to n-3 PUFAs is likely to be due to their ability to permeate the outer membrane or cell wall, which will enable access to the sites of action on the inner membrane leading to membrane disruption. Studies also suggest associations between specific microbes and CRC may be associated with diet [143]. Fusobacterium nucleatum has been shown to promote colorectal tumor growth and inhibit antitumor growth in animal models and is detected in a subset of human colorectal neoplasias [144]. In a large prospective cohort using data from the Nurse’s Health Study and Health Professionals Follow-up Study, diets rich in whole grains and dietary fiber are associated with a lower risk for F nucleatum–positive, but not F nucleatum–negative, CRC, supporting a potential role for gut microbiota in mediating the association between diet and colorectal neoplasms [145].

Conclusions

Studies in animals have shown that both n-3 PUFA and a bacterial metabolite of dietary fiber (butyrate) may reduce colon tumor formation, and that the two in combination are even more effective than either alone. Several novel mechanisms of action have been suggested, including the enhancement of a Gpx4-dependent, lipid oxidation-sensitive, Gpx-4 and mitochondrial dependent cell death pathway in the colonic mucosa. In humans, some epidemiologic studies suggest that people who consume high-fiber diets or use n-3 PUFA supplements may have a lower risk of CRC, however there are currently no controlled dietary interventions evaluating the combined effects of these two dietary constituents on CRC-relevant pathways in humans. Data from preclinical and mechanistic studies support an important role for gut microbe-derived SCFA, particularly butyrate, in combination with n-3 PUFA, in reduction of colon tumorigenesis. However, although both n-3 PUFA [34,146–149], and fiber [150–153], alone have been studied, no clinical studies have been conducted to translate these combinatorial findings to humans. We propose that low intakes of fiber and n-3 PUFA in Western populations, and the failure to address an interaction, may explain why the chemoprotective effects of n-3 PUFA and fermentable fibers are not detected consistently in prospective cohort studies.

Key Points:

n-3 PUFA and butyrate from bacterial fiber fermentation may reduce colorectal cancer risk

fat and fiber interaction (pescovegetarian diet) induces intrinsic mitochondrial-mediated programmed cell death in the colon, which reduces colorectal cancer risk

fish oil and fermentable fiber intake uniquely promote mucosal beta-oxidation which maintains a hypoxic environment in the gut and promotes the growth of obligate anaerobic bacteria, thereby inhibiting dysbiotic microbial expansion

Acknowledgments:

We would like to thank Rachel C. Wright for generation of the figures. Grant support was provided by the Allen Endowed Chair in Nutrition & Chronic Disease Prevention and the National Institutes of Health (R21-CA245456 and R35-CA197707).

Biographies

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

References

- 1.Trock BL E Greenwald P Dietary fiber, vegetables, and colon cancer: critical review and meta-analyses of the epidemiologic evidence Natl Cancer Inst. 2018;1990:650–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ben Q, Sun Y, Chai R, Qian A, Xu B, Yuan Y. Dietary fiber intake reduces risk for colorectal adenoma: a meta-analysis Gastroenterology. 2014;146:689–699 e686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perez-Cueto FJ, Verbeke W. Consumer implications of the WCRF’s permanent update on colorectal cancer Meat Sci. 2012;90:977–978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Research WC. Diet, nutrition, physical activity and colorectal cancer. City;2018:http://www.aicr.org/continuous-update-proiect/colorectal-cancer.html. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schatzkin A, Mouw T, Park Y et al. Dietary fiber and whole-grain consumption in relation to colorectal cancer in the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85:1353–1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murphy N, Norat T, Ferrari P et al. Dietary fibre intake and risks of cancers of the colon and rectum in the European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition (EPIC) PLoS One. 2012;7:e39361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aune D, Chan DS, Lau R et al. Dietary fibre, whole grains, and risk of colorectal cancer: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies BMJ. 2011;343:d6617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Navarro SL, Neuhouser ML, Cheng TD et al. The Interaction between Dietary Fiber and Fat and Risk of Colorectal Cancer in the Women’s Health Initiative Nutrients. 2016;8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thompson HJ, Brick MA. Perspective: Closing the Dietary Fiber Gap: An Ancient Solution for a 21st Century Problem Adv Nutr. 2016;7:623–626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bingham SA. Diet and large bowel cancer J R Soc Med. 1990;83:420–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Young GP, Hu Y, Le Leu RK, Nyskohus L. Dietary fibre and colorectal cancer: a model for environment--gene interactions Mol Nutr Food Res. 2005;49:571–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Slavin JL. Dietary fiber and body weight Nutrition. 2005;21:411–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen T, Long W, Zhang C, Liu S, Zhao L, Hamaker BR. Fiber-utilizing capacity varies in Prevotella- versus Bacteroides-dominated gut microbiota Sci Rep. 2017;7:2594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Donohoe DR, Bultman SJ. Metaboloepigenetics: interrelationships between energy metabolism and epigenetic control of gene expression J Cell Physiol. 2012;227:3169–3177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Donohoe DR, Garge N, Zhang X et al. The microbiome and butyrate regulate energy metabolism and autophagy in the mammalian colon Cell Metab. 2011;13:517–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang T, Cai G, Qiu Y et al. Structural segregation of gut microbiota between colorectal cancer patients and healthy volunteers ISME J. 2012;6:320–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu N, Yang X, Zhang R et al. Dysbiosis signature of fecal microbiota in colorectal cancer patients Microb Ecol. 2013;66:462–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weir TL, Manter DK, Sheflin AM, Barnett BA, Heuberger AL, Ryan EP. Stool microbiome and metabolome differences between colorectal cancer patients and healthy adults PLoS One. 2013;8:e70803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patnode ML, Beller ZW, Han ND et al. Interspecies Competition Impacts Targeted Manipulation of Human Gut Bacteria by Fiber-Derived Glycans Cell. 2019;179:59–73 e13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Makki K, Deehan EC, Walter J, Backhed F. The Impact of Dietary Fiber on Gut Microbiota in Host Health and Disease Cell Host Microbe. 2018;23:705–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duncan SH, Holtrop G, Lobley GE, Calder AG, Stewart CS, Flint HJ. Contribution of acetate to butyrate formation by human faecal bacteria Br J Nutr. 2004;91:915–923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Uchida K, Kono S, Yin G et al. Dietary fiber, source foods and colorectal cancer risk: the Fukuoka Colorectal Cancer Study Scand J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:1223–1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wakai K, Date C, Fukui M et al. Dietary fiber and risk of colorectal cancer in the Japan collaborative cohort study Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:668–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levi F, Pasche C, Lucchini F, La Vecchia C. Dietary fibre and the risk of colorectal cancer Eur J Cancer. 2001;37:2091–2096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Freudenheim JL, Graham S, Horvath PJ, Marshall JR, Haughey BP, Wilkinson G. Risks associated with source of fiber and fiber components in cancer of the colon and rectum Cancer Res. 1990;50:3295–3300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Le Marchand L, Hankin JH, Wilkens LR, Kolonel LN, Englyst HN, Lyu LC. Dietary fiber and colorectal cancer risk Epidemiology. 1997;8:658–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Negri E, Franceschi S, Parpinel M, La Vecchia C. Fiber intake and risk of colorectal cancer Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1998;7:667–671. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sellem L, Srour B, Gueraud F et al. Saturated, mono- and polyunsaturated fatty acid intake and cancer risk: results from the French prospective cohort NutriNet-Sante Eur J Nutr. 2019;58:1515–1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Strobel C, Jahreis G, Kuhnt K. Survey of n-3 and n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids in fish and fish products Lipids Health Dis. 2012;11:144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Simopoulos AP. Importance of the omega-6/omega-3 balance in health and disease: evolutionary aspects of diet World Rev Nutr Diet. 2011;102:10–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Skender B, Vaculova AH, Hofmanova J. Docosahexaenoic fatty acid (DHA) in the regulation of colon cell growth and cell death: a review Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 2012;156:186–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Azer SS. Overview of molecular pathways in inflammatory bowel disease associated with colorectal cancer development Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;25:271–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cockbain AJ, Toogood GJ, Hull MA. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids for the treatment and prevention of colorectal cancer Gut. 2012;61:135–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chang WC, Chapkin RS, Lupton JR. Predictive value of proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis as intermediate markers for colon tumorigenesis Carcinogenesis. 1997;18:721–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hou TY, Davidson LA, Kim E et al. Nutrient-Gene Interaction in Colon Cancer, from the Membrane to Cellular Physiology Annu Rev Nutr. 2016;36:543–570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reddy BS. Omega-3 fatty acids in colorectal cancer prevention Int J Cancer. 2004;112:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fuentes NR, Mlih M, Barhoumi R et al. Long-Chain n-3 Fatty Acids Attenuate Oncogenic KRas-Driven Proliferation by Altering Plasma Membrane Nanoscale Proteolipid Composition Cancer Res. 2018;78:3899–3912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu S, Feng B, Li K et al. Fish consumption and colorectal cancer risk in humans: a systematic review and meta-analysis Am J Med. 2012;125:551–559 e555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Geelen A, Schouten JM, Kamphuis C et al. Fish consumption, n-3 fatty acids, and colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies Am J Epidemiol. 2007;166:1116–1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.MacLean CH, Newberry SJ, Mojica WA et al. Effects of omega-3 fatty acids on cancer risk: a systematic review JAMA. 2006;295:403–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gerber M Omega-3 fatty acids and cancers: a systematic update review of epidemiological studies Br J Nutr. 2012;107 Suppl 2:S228–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Song M, Chan AT, Fuchs CS et al. Dietary intake of fish, omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids and risk of colorectal cancer: A prospective study in U.S. men and women Int J Cancer. 2014;135:2413–2423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Song M, Nishihara R, Cao Y et al. Marine omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid Intake and Risk of Colorectal Cancer Characterized by Tumor-Infiltrating T Cells JAMA Oncol. 2016;2:1197–1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kantor ED, Lampe JW, Peters U, Vaughan TL, White E. Long-chain omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid intake and risk of colorectal cancer Nutr Cancer. 2014;66:716–727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Van Blarigan EL, Fuchs CS, Niedzwiecki D et al. Marine omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid and Fish Intake after Colon Cancer Diagnosis and Survival: CALGB 89803 (Alliance) Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2018;27:438–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chapkin RS, Fan Y, Lupton JR. Effect of diet on colonic-programmed cell death: molecular mechanism of action Toxicol Lett. 2000;112–113:411–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cho Y, Turner ND, Davidson LA, Chapkin RS, Carroll RJ, Lupton JR. Colon cancer cell apoptosis is induced by combined exposure to the n-3 fatty acid docosahexaenoic acid and butyrate through promoter methylation Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2014;239:302–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kolar S, Barhoumi R, Jones CK et al. Interactive effects of fatty acid and butyrate-induced mitochondrial Ca(2)(+) loading and apoptosis in colonocytes Cancer. 2011;117:5294–5303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kansal S, Negi AK, Bhatnagar A, Agnihotri N. Ras signaling pathway in the chemopreventive action of different ratios of fish oil and corn oil in experimentally induced colon carcinogenesis Nutr Cancer. 2012;64:559–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sarotra P, Kansal S, Sandhir R, Agnihotri N. Chemopreventive effect of different ratios of fish oil and corn oil on prognostic markers, DNA damage and cell cycle in colon carcinogenesis Eur J Cancer Prev. 2012;21:147–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kolar SS, Barhoumi R, Callaway ES et al. Synergy between docosahexaenoic acid and butyrate elicits p53-independent apoptosis via mitochondrial Ca(2+) accumulation in colonocytes Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007;293:G935–943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Orlich MJ, Singh PN, Sabate J et al. Vegetarian dietary patterns and the risk of colorectal cancers JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:767–776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.O’Keefe SJ, Li JV, Lahti L et al. Fat, fibre and cancer risk in African Americans and rural Africans Nat Commun. 2015;6:6342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kraja B, Muka T, Ruiter R et al. Dietary Fiber Intake Modifies the Positive Association between n-3 PUFA Intake and Colorectal Cancer Risk in a Caucasian Population J Nutr. 2015;145:1709–1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sanders LM, Henderson CE, Hong MY et al. An increase in reactive oxygen species by dietary fish oil coupled with the attenuation of antioxidant defenses by dietary pectin enhances rat colonocyte apoptosis J Nutr. 2004;134:3233–3238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vanamala J, Glagolenko A, Yang P et al. Dietary fish oil and pectin enhance colonocyte apoptosis in part through suppression of PPARdelta/PGE2 and elevation of PGE3 Carcinogenesis. 2008;29:790–796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Crim KC, Sanders LM, Hong MY et al. Upregulation of p21Waf1/Cip1 expression in vivo by butyrate administration can be chemoprotective or chemopromotive depending on the lipid component of the diet Carcinogenesis. 2008;29:1415–1420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cho Y, Kim H, Turner ND et al. A chemoprotective fish oil- and pectin-containing diet temporally alters gene expression profiles in exfoliated rat colonocytes throughout oncogenesis J Nutr. 2011;141:1029–1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chapkin RS, DeClercq V, Kim E, Fuentes NR, Fan YY. Mechanisms by Which Pleiotropic Amphiphilic n-3 PUFA Reduce Colon Cancer Risk Curr Colorectal Cancer Rep. 2014;10:442–452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Triff K, Kim E, Chapkin RS. Chemoprotective epigenetic mechanisms in a colorectal cancer model: Modulation by n-3 PUFA in combination with fermentable fiber Curr Pharmacol Rep. 2015;1:11–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kolar SS, Barhoumi R, Lupton JR, Chapkin RS. Docosahexaenoic acid and butyrate synergistically induce colonocyte apoptosis by enhancing mitochondrial Ca2+ accumulation Cancer Res. 2007;67:5561–5568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jiang YH, Lupton JR, Chapkin RS. Dietary fat and fiber modulate the effect of carcinogen on colonic protein kinase C lambda expression in rats J Nutr. 1997;127:1938–1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Triff K, McLean MW, Callaway E, Goldsby J, Ivanov I, Chapkin RS. Dietary fat and fiber interact to uniquely modify global histone post-translational epigenetic programming in a rat colon cancer progression model Int J Cancer. 2018;143:1402–1415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zimmerman MA, Singh N, Martin PM et al. Butyrate suppresses colonic inflammation through HDAC1-dependent Fas upregulation and Fas-mediated apoptosis of T cells Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2012;302:G1405–1415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Donohoe DR, Collins LB, Wali A, Bigler R, Sun W, Bultman SJ. The Warburg effect dictates the mechanism of butyrate-mediated histone acetylation and cell proliferation Mol Cell. 2012;48:612–626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bultman SJ. Molecular pathways: gene-environment interactions regulating dietary fiber induction of proliferation and apoptosis via butyrate for cancer prevention Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:799–803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Roediger WE. Utilization of nutrients by isolated epithelial cells of the rat colon Gastroenterology. 1982;83:424–429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ng Y, Barhoumi R, Tjalkens RB et al. The role of docosahexaenoic acid in mediating mitochondrial membrane lipid oxidation and apoptosis in colonocytes Carcinogenesis. 2005;26:1914–1921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fan YY, Zhan Y, Aukema HM et al. Proapoptotic effects of dietary (n-3) fatty acids are enhanced in colonocytes of manganese-dependent superoxide dismutase knockout mice J Nutr. 2009;139:1328–1332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fan YY, Ran Q, Toyokuni S et al. Dietary fish oil promotes colonic apoptosis and mitochondrial proton leak in oxidatively stressed mice Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2011;4:1267–1274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kelso GF, Porteous CM, Coulter CV et al. Selective targeting of a redox-active ubiquinone to mitochondria within cells: antioxidant and antiapoptotic properties J Biol Chem. 2001;276:4588–4596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lyn PC, Lim TH. Listeria meningitis resistant to ampicillin J Singapore Paediatr Soc. 1986;28:247–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Stockwell BR, Friedmann Angeli JP, Bayir H et al. Ferroptosis: A Regulated Cell Death Nexus Linking Metabolism, Redox Biology, and Disease Cell. 2017;171:273–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Orrenius S, Zhivotovsky B, Nicotera P. Regulation of cell death: the calcium-apoptosis link Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:552–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bedi A, Pasricha PJ, Akhtar AJ et al. Inhibition of apoptosis during development of colorectal cancer Cancer Res. 1995;55:1811–1816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Shah MS, Kim E, Davidson LA et al. Comparative effects of diet and carcinogen on microRNA expression in the stem cell niche of the mouse colonic crypt Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1862:121–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Litvak Y, Byndloss MX, Tsolis RM, Baumler AJ. Dysbiotic Proteobacteria expansion: a microbial signature of epithelial dysfunction Curr Opin Microbiol. 2017;39:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Litvak Y, Byndloss MX, Baumler AJ. Colonocyte metabolism shapes the gut microbiota Science. 2018;362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kelly CJ, Zheng L, Campbell EL et al. Crosstalk between Microbiota-Derived Short-Chain Fatty Acids and Intestinal Epithelial HIF Augments Tissue Barrier Function Cell Host Microbe. 2015;17:662–671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.O’Keefe SJ. Diet, microorganisms and their metabolites, and colon cancer Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;13:691–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lampe JW, Kim E, Levy L et al. Colonic mucosal and exfoliome transcriptomic profiling and fecal microbiome response to a flaxseed lignan extract intervention in humans Am J Clin Nutr. 2019;110:377–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.David LA, Maurice CF, Carmody RN et al. Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome Nature. 2014;505:559–563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hooda S, Boler BM, Serao MC et al. 454 pyrosequencing reveals a shift in fecal microbiota of healthy adult men consuming polydextrose or soluble corn fiber J Nutr. 2012;142:1259–1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ross AB, Bruce SJ, Blondel-Lubrano A et al. A whole-grain cereal-rich diet increases plasma betaine, and tends to decrease total and LDL-cholesterol compared with a refined-grain diet in healthy subjects Br J Nutr. 2011;105:1492–1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Costabile A, Klinder A, Fava F et al. Whole-grain wheat breakfast cereal has a prebiotic effect on the human gut microbiota: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study Br J Nutr. 2008;99:110–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Finley JW, Burrell JB, Reeves PG. Pinto bean consumption changes SCFA profiles in fecal fermentations, bacterial populations of the lower bowel, and lipid profiles in blood of humans J Nutr. 2007;137:2391–2398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Smith SC, Choy R, Johnson SK, Hall RS, Wildeboer-Veloo AC, Welling GW. Lupin kernel fiber consumption modifies fecal microbiota in healthy men as determined by rRNA gene fluorescent in situ hybridization Eur J Nutr. 2006;45:335–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Johnson SK, Chua V, Hall RS, Baxter AL. Lupin kernel fibre foods improve bowel function and beneficially modify some putative faecal risk factors for colon cancer in men Br J Nutr. 2006;95:372–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Tuohy KM, Kolida S, Lustenberger AM, Gibson GR. The prebiotic effects of biscuits containing partially hydrolysed guar gum and fructo-oligosaccharides--a human volunteer study Br J Nutr. 2001;86:341–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hylla S, Gostner A, Dusel G et al. Effects of resistant starch on the colon in healthy volunteers: possible implications for cancer prevention Am J Clin Nutr. 1998;67:136–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Arumugam M, Raes J, Pelletier E et al. Enterotypes of the human gut microbiome Nature. 2011;473:174–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Faust K, Raes J. Microbial interactions: from networks to models Nat Rev Microbiol. 2012;10:538–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Faust K, Sathirapongsasuti JF, Izard J et al. Microbial co-occurrence relationships in the human microbiome PLoS Comput Biol. 2012;8:e1002606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lozupone C, Faust K, Raes J et al. Identifying genomic and metabolic features that can underlie early successional and opportunistic lifestyles of human gut symbionts Genome Res. 2012;22:1974–1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Bolca S, Van de Wiele T, Possemiers S. Gut metabotypes govern health effects of dietary polyphenols Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2013;24:220–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Heinzmann SS, Merrifield CA, Rezzi S et al. Stability and robustness of human metabolic phenotypes in response to sequential food challenges J Proteome Res. 2012;11:643–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Walker AW, Ince J, Duncan SH et al. Dominant and diet-responsive groups of bacteria within the human colonic microbiota ISME J. 2011;5:220–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Weickert MO, Arafat AM, Blaut M et al. Changes in dominant groups of the gut microbiota do not explain cereal-fiber induced improvement of whole-body insulin sensitivity Nutr Metab (Lond). 2011;8:90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Russell WR, Gratz SW, Duncan SH et al. High-protein, reduced-carbohydrate weight-loss diets promote metabolite profiles likely to be detrimental to colonic health Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;93:1062–1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Duncan SH, Belenguer A, Holtrop G, Johnstone AM, Flint HJ, Lobley GE. Reduced dietary intake of carbohydrates by obese subjects results in decreased concentrations of butyrate and butyrate-producing bacteria in feces Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:1073–1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ley RE, Turnbaugh PJ, Klein S, Gordon JI. Microbial ecology: human gut microbes associated with obesity Nature. 2006;444:1022–1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Cummings JH, Pomare EW, Branch WJ, Naylor CP, Macfarlane GT. Short chain fatty acids in human large intestine, portal, hepatic and venous blood Gut. 1987;28:1221–1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Louis P, McCrae SI, Charrier C, Flint HJ. Organization of butyrate synthetic genes in human colonic bacteria: phylogenetic conservation and horizontal gene transfer FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2007;269:240–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Louis P, Scott KP, Duncan SH, Flint HJ. Understanding the effects of diet on bacterial metabolism in the large intestine J Appl Microbiol. 2007;102:1197–1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Ley RE, Lozupone CA, Hamady M, Knight R Gordon JI. Worlds within worlds: evolution of the vertebrate gut microbiota Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6:776–788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Gibson GR, Macfarlane GT, Cummings JH. Sulphate reducing bacteria and hydrogen metabolism in the human large intestine Gut. 1993;34:437–439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Vital M, Howe AC, Tiedje JM. Revealing the bacterial butyrate synthesis pathways by analyzing (meta)genomic data MBio. 2014;5:e00889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Barcenilla A, Pryde SE, Martin JC et al. Phylogenetic relationships of butyrate-producing bacteria from the human gut Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:1654–1661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Matthies C, Schink B. Fermentative degradation of glutarate via decarboxylation by newly isolated strictly anaerobic bacteria Arch Microbiol. 1992;157:290–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Matthies C, Schink B. Reciprocal isomerization of butyrate and isobutyrate by the strictly anaerobic bacterium strain WoG13 and methanogenic isobutyrate degradation by a defined triculture Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:1435–1439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Roeder J, Schink B. Syntrophic degradation of cadaverine by a defined methanogenic coculture Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:4821–4828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Gharbia SE, Shah HN. Pathways of glutamate catabolism among Fusobacterium species J Gen Microbiol. 1991;137:1201–1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Gerhardt A, Cinkaya I, Linder D, Huisman G, Buckel W. Fermentation of 4-aminobutyrate by Clostridium aminobutyricum: cloning of two genes involved in the formation and dehydration of 4-hydroxybutyryl-CoA Arch Microbiol. 2000;174:189–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Buckel W Unusual enzymes involved in five pathways of glutamate fermentation Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2001;57:263–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Kreimeyer A, Perret A, Lechaplais C et al. Identification of the last unknown genes in the fermentation pathway of lysine J Biol Chem. 2007;282:7191–7197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Potrykus J, White RL, Bearne SL. Proteomic investigation of amino acid catabolism in the indigenous gut anaerobe Fusobacterium varium Proteomics. 2008;8:2691–2703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Uematsu H, Hoshino E, . Degradation of arginine and other amino acids by Eubacterium nodatum ATCC 33099 Microb Ecol Health Dis. 1996;9:305–311. [Google Scholar]

- 118.Hippe B, Zwielehner J, Liszt K, Lassl C, Unger F, Haslberger AG. Quantification of butyryl CoA:acetate CoA-transferase genes reveals different butyrate production capacity in individuals according to diet and age FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2011;316:130–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Louis P, Young P, Holtrop G, Flint HJ. Diversity of human colonic butyrate-producing bacteria revealed by analysis of the butyryl-CoA:acetate CoA-transferase gene Environ Microbiol. 2010;12:304–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Louis P, Flint HJ. Diversity, metabolism and microbial ecology of butyrate-producing bacteria from the human large intestine FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2009;294:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Duncan SH, Barcenilla A, Stewart CS, Pryde SE, Flint HJ. Acetate utilization and butyryl coenzyme A (CoA):acetate-CoA transferase in butyrate-producing bacteria from the human large intestine Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002;68:5186–5190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Vital M, Gao J, Rizzo M, Harrison T, Tiedje JM. Diet is a major factor governing the fecal butyrate-producing community structure across Mammalia, Aves and Reptilia ISME J. 2015;9:832–843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Fernandes J, Wang A, Su W et al. Age, dietary fiber, breath methane, and fecal short chain fatty acids are interrelated in Archaea-positive humans J Nutr. 2013;143:1269–1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Guy CJ Abell MACALM. Methanogenic archaea in adult human faecal samples are inversely related to butyrate concentration Microbial Ecology in Health and Disease. 2006;18:3-4, 154–160. [Google Scholar]

- 125.Ragsdale SW, Pierce E. Acetogenesis and the Wood-Ljungdahl pathway of CO(2) fixation Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1784:1873–1898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Cheng J, Ogawa K, Kuriki K et al. Increased intake of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids elevates the level of apoptosis in the normal sigmoid colon of patients polypectomized for adenomas/tumors Cancer Lett. 2003;193:17–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Courtney ED, Matthews S, Finlayson C et al. Eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) reduces crypt cell proliferation and increases apoptosis in normal colonic mucosa in subjects with a history of colorectal adenomas Int J Colorectal Dis. 2007;22:765–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Lochhead P, Chan AT, Nishihara R et al. Etiologic field effect: reappraisal of the field effect concept in cancer predisposition and progression Mod Pathol. 2015;28:14–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Wu GD, Chen J, Hoffmann C et al. Linking long-term dietary patterns with gut microbial enterotypes Science. 2011;334:105–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Tilg H, Kaser A. Gut microbiome, obesity, and metabolic dysfunction J Clin Invest. 2011;121:2126–2132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Ley RE. Obesity and the human microbiome Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2010;26:5–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.O’Keefe SJ. Nutrition and colonic health: the critical role of the microbiota Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2008;24:51–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Patterson E, RM OD, Murphy EF et al. Impact of dietary fatty acids on metabolic activity and host intestinal microbiota composition in C57BL/6J mice Br J Nutr. 2014;111:1905–1917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Tabbaa M, Golubic M, Roizen MF, Bernstein AM. Docosahexaenoic acid, inflammation, and bacterial dysbiosis in relation to periodontal disease, inflammatory bowel disease, and the metabolic syndrome Nutrients. 2013;5:3299–3310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Urwin HJ, Miles EA, Noakes PS et al. Effect of salmon consumption during pregnancy on maternal and infant faecal microbiota, secretory IgA and calprotectin Br J Nutr. 2014;111:773–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Geier MS, Torok VA, Allison GE et al. Dietary omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid does not influence the intestinal microbial communities of broiler chickens Poult Sci. 2009;88:2399–2405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Yu HN, Zhu J, Pan WS, Shen SR, Shan WG, Das UN. Effects of fish oil with a high content of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids on mouse gut microbiota Arch Med Res. 2014;45:195–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Sun M, Zhou Z, Dong J, Zhang J, Xia Y, Shu R. Antibacterial and antibiofilm activities of docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) against periodontopathic bacteria Microb Pathog. 2016;99:196–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Rodes L, Khan A, Paul A et al. Effect of probiotics Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium on gut-derived lipopolysaccharides and inflammatory cytokines: an in vitro study using a human colonic microbiota model J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2013;23:518–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Elmadfa I, Klein P, Meyer AL. Immune-stimulating effects of lactic acid bacteria in vivo and in vitro Proc Nutr Soc. 2010;69:416–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Cani PD, Bibiloni R, Knauf C et al. Changes in gut microbiota control metabolic endotoxemia-induced inflammation in high-fat diet-induced obesity and diabetes in mice Diabetes. 2008;57:1470–1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Karlsson H, Larsson P, Wold AE, Rudin A. Pattern of cytokine responses to grampositive and gram-negative commensal bacteria is profoundly changed when monocytes differentiate into dendritic cells Infect Immun. 2004;72:2671–2678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Desbois AP, Smith VJ. Antibacterial free fatty acids: activities, mechanisms of action and biotechnological potential Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2010;85:1629–1642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Mima K, Cao Y, Chan AT et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum in Colorectal Carcinoma Tissue According to Tumor Location Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2016;7:e200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Mehta RS, Nishihara R, Cao Y et al. Association of Dietary Patterns With Risk of Colorectal Cancer Subtypes Classified by Fusobacterium nucleatum in Tumor Tissue JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:921–927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Barone M, Notarnicola M, Caruso MG et al. Olive oil and omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids suppress intestinal polyp growth by modulating the apoptotic process in ApcMin/+ mice Carcinogenesis. 2014;35:1613–1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Piazzi G, D’Argenio G, Prossomariti A et al. Eicosapentaenoic acid free fatty acid prevents and suppresses colonic neoplasia in colitis-associated colorectal cancer acting on Notch signaling and gut microbiota Int J Cancer. 2014;135:2004–2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Han YM, Park JM, Cha JY, Jeong M, Go EJ, Hahm KB. Endogenous conversion of omega-6 to omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in fat-1 mice attenuated intestinal polyposis by either inhibiting COX-2/beta-catenin signaling or activating 15-PGDH/IL-18 Int J Cancer. 2016;138:2247–2256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Pot GK, Geelen A, van Heijningen EM, Siezen CL, van Kranen HJ, Kampman E. Opposing associations of serum n-3 and n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids with colorectal adenoma risk: an endoscopy-based case-control study Int J Cancer. 2008;123:1974–1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Goncalves P, Martel F. Butyrate and colorectal cancer: the role of butyrate transport Curr Drug Metab. 2013;14:994–1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Sengupta S, Tjandra JJ, Gibson PR. Dietary fiber and colorectal neoplasia Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:1016–1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.McIntyre A, Gibson PR, Young GP. Butyrate production from dietary fibre and protection against large bowel cancer in a rat model Gut. 1993;34:386–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Asano T, McLeod RS. Dietary fibre for the prevention of colorectal adenomas and carcinomas Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002:CD003430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]