Abstract

Objectives

Infectious disease outbreaks can be distressing for everyone, especially those deemed to be particularly vulnerable such as pregnant women, who have been named a high-risk group in the current COVID-19 pandemic. This paper aimed to summarise existing literature on the psychological impact of infectious disease outbreaks on women who were pregnant at the time of the outbreak.

Study design

The design of this study is a rapid review.

Methods

Five databases were searched for relevant literature, and main findings were extracted.

Results

Thirteen articles were included in the review. The following themes were identified: negative emotional states; living with uncertainty; concerns about infection; concerns about and uptake of prophylaxis or treatment; disrupted routines; non-pharmaceutical protective behaviours; social support; financial and occupational concerns; disrupted expectations of birth, prenatal care and postnatal care and sources of information.

Conclusions

Pregnant women have unique needs during infectious disease outbreaks and could benefit from up-to-date, consistent information and guidance; appropriate support and advice from healthcare professionals, particularly with regards to the risks and benefits of prophylaxis and treatment; virtual support groups and designating locations or staff specifically for pregnant women.

Keywords: Coronavirus, COVID-19, Disease outbreaks, Infectious diseases, Mental health, Pregnancy

Highlights

-

•

Pregnant women may be particularly susceptible to distress during pandemics.

-

•

Infection fears and prophylaxis concerns may exacerbate distress.

-

•

Disrupted routines, financial concerns and uncertainty are also stressors.

-

•

Disrupted expectations of birth and related healthcare may be distressing.

-

•

Pregnant women may benefit from clear information/guidance and support groups.

Introduction

The outbreak of coronavirus COVID-19 has – as of June 2nd, 2020 – seen more than six million cases and more than 377,000 related deaths worldwide.1 Such outbreaks are understandably distressing; there is a wealth of research to suggest a substantial negative psychological impact of public health emergencies such as pandemics.2 The importance of addressing the negative impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health is reflected in the provision of public guidance for mental health and well-being during the pandemic3 and calls for psychosocial support to be incorporated into pandemic healthcare; after all, there is ‘no health without mental health’.4

There is historical evidence of pregnant women being a high-risk group during pandemics; pregnancy was associated with high mortality rates during the H1N1 ‘swine flu’ pandemic5 and the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) pandemic.6 During the COVID-19 outbreak, questions have been raised about the particular risks for pregnant women and their unborn babies,7 with a review of the limited data available so far,8 suggesting that outcomes for mothers are more promising than for mothers of previous outbreaks. However, on March 16th 2020, the UK government announced that pregnant women were considered a ‘vulnerable group’ and recommended they self-isolate.9

Despite the considerable body of literature on clinical outcomes of being diagnosed with an infectious disease during pregnancy, little attention has been paid to the psychological impact of such outbreaks on pregnant women (including non-infected individuals). They may have fears for their own health, given the physiological changes that occur during pregnancy which may make them more severely affected by infectious diseases,10 as well as the health of their unborn babies. They may also experience distress due to disrupted prenatal care and delivery: women who gave birth during the SARS and H1N1 outbreaks were discharged as soon as possible after delivery, and prenatal services considered non-essential were suspended.6 , 11 , 12 Research suggests lack of control over decisions relating to childbirth can be traumatic,13 raising concerns about how women giving birth during the COVID-19 pandemic will cope with, for example, restrictions on hospital visitation procedures during and after labour. In many countries (such as the UK), women are being requested to attend all prenatal appointments alone14 and in some countries (including Poland and China) are required to give birth alone,15 , 16 despite familial support during the birthing process being considered essential for women's well-being.17

Maternal mental health research is an important, yet understudied, aspect of public health research, as psychological difficulties during pregnancy can affect the mental health of both mothers and children. Buekens et al.18 have called for research on pregnancy during the COVID-19 pandemic, recognising its potential psychological and social impact. This review is the first to systematically examine literature on the psychological impact of infectious disease outbreaks on pregnant women and factors associated with this impact.

Methods

This was a rapid evidence review in response to the 2019–2020 COVID-19 outbreak. Rapid reviews follow the general guidelines for traditional systematic reviews but are simplified to produce evidence quickly; they are recommended during circumstances where policymakers urgently need evidence synthesis to inform public health guidelines.19

Medline, PsycInfo, Embase, Global Health and Web of Science databases were searched from inception to the date of the searches (April 1st 2020). The search involved a combination of pregnancy-related terms (e.g. pregnant, pregnanc∗), mental health–related terms (e.g. mental health, well-being) and outbreak-related terms (e.g. pandemic, SARS). The full search strategy is presented in Appendix I.

Inclusion criteria for the review were as follows: articles must (i) report primary data either quantitative or qualitative, (ii) be published in peer-reviewed journals, (iii) be written in English and (iv) report on psychological effects of emerging infectious disease outbreaks (e.g. SARS, H1N1) on women who were pregnant at the time of the outbreak. Zika was also considered a relevant outbreak for review because, despite the spread of the infection being different, this outbreak had a particular impact on pregnant women as it was associated with birth defects.20 The review focused on emerging infectious diseases (that is, diseases appearing for the first time in a population or rapidly increasing in incidence or geographic range).21 Articles were excluded if they were letters, commentaries or reviews without primary data; if they were written in any language other than English; if they did not consider a psychological aspect of being pregnant during an infectious disease outbreak and if the disease outbreak was not an emerging infectious disease (i.e. articles on seasonal influenza were excluded).

The authors ran the searches and downloaded all citations to EndNote version X9 (Thomson Reuters, New York, United States) where duplicates were removed. Titles and then abstracts were screened by one author (SKB) for relevance to the selection criteria. Full texts of all articles remaining after abstract screening were downloaded and assessed to decide whether they met all inclusion criteria. Reference lists of all included articles were hand searched, and any references not found by our own search, which suggested from their title that they may contain relevant data, were downloaded and assessed for eligibility. Screening was performed by one author; however, any uncertainties about whether an article met all inclusion criteria or not were discussed with the other authors.

Spreadsheets were created to systematically extract the following data from the articles: country, design, infectious disease outbreak, participant information (n and sociodemographics), measures used and results. During data extraction, it became clear that the included studies used varying methodologies and measures and presented their data in various ways. Therefore, study results were synthesised using inductive thematic analysis to code the data and organise into themes.22 This was chosen as an effective way of describing data from multiple studies. Following repeated readings of the ‘results’ section of our data spreadsheet, data were first broadly coded and used to develop descriptive themes. Similar results were grouped together (e.g. all data on anxiety, stress or fear were grouped together and coded as ‘negative emotional states’; all data on work or money concerns were grouped together and coded as ‘financial and occupational concerns’). The final list of themes was reached when no new themes emerged from the data.

Results

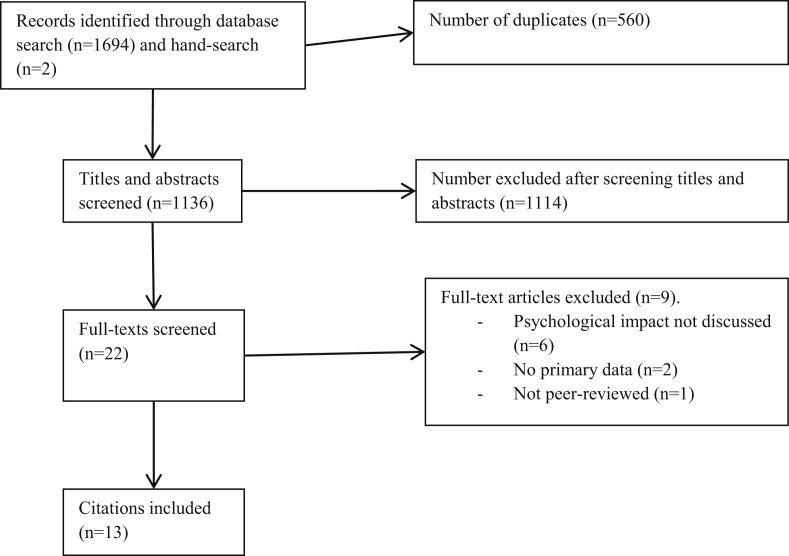

Initial searches yielded 1694 citations; 560 duplicates were removed. Nine hundred ninety-nine articles were excluded based on title, 115 excluded based on abstract and nine excluded after assessing full texts. Two additional articles were found via hand searching, leaving a total of thirteen articles included (refer Fig. 1 for flow diagram).

Fig. 1.

. Flow diagram of the screening process.

Study characteristics

Studies were international, including participants from China;23, 24, 25 Brazil, Puerto Rico and the USA;26 Scotland and Australia;27 the USA;28, 29, 30 Brazil;31 Turkey;32 Canada;33 Japan34 and Scotland and Poland.35 Outbreaks included SARS (n = 3), H1N1 (n = 8) and Zika (n = 2). Articles were published between 2006 and 2018. The number of participants ranged from 8 to 980. A variety of quantitative and qualitative measures were used by the studies, with more than half (n = 7) using interviews or focus groups. Study characteristics are presented in more depth in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Study characteristics of included articles.

| Study | Country | Disease outbreak | Participants | Measures |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dodgson et al. (2010)23 | China (Hong Kong) | SARS | 8 women who delivered healthy babies during the outbreak; mean age 34.3 years (range 28–38) | Interviews about experiences of being pregnant and delivering their baby during the SARS epidemic |

| Lee et al. (2006)24 | China (Hong Kong) | SARS | 235 women pregnant during the outbreak compared with a historical cohort of 939 recruited a year before; mean age 29.9 years (SARS cohort), 29.6 years (pre-SARS cohort) | Beck Depression Inventory, Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey. The SARS cohort also completed a 41-item questionnaire on worries, perceived risk and behavioural responses to SARS |

| Linde & Siqueira (2018)26 | Brazil, Puerto Rico and USA | Zika | 18 women: 5 had a recently born baby, 6 were pregnant, 5 were planning to get pregnant, 3 had no plans to get pregnant. Age range 22–41 | Interviews about personal and family life, perceptions and knowledge of Zika, views on reproductive health and rights regarding the Zika syndrome |

| Lohm et al. (2014)27 | Australia and Scotland | H1N1 | 14 pregnant women aged between 20 and 40 years | Interviews and focus groups about experiences with H1N1 and the public health response to H1N1 |

| Lyerly et al. (2012)28 | USA | H1N1 | 22 pregnant women who had participated in the H1N1 vaccine trials; mean age 31 years, range 19–39 | Interviews about experiences of decision-making around participation in the H1N1 vaccine trial |

| Lynch et al. (2012)29 | USA | H1N1 | 144 women: 43.4% of women were pregnant and 56.6% were within 6 months postpartum; 26.4% aged 18–24 years, 61.8% aged 25–34 years and 11.8% aged 35–44 years | Focus groups covering perceptions and awareness of H1N1, influenza vaccinations and antiviral medicines and trusted sources of information |

| Meireles et al. (2017)31 | Brazil | Zika | 14 pregnant women: 6 in the first trimester, 5 in the second trimester and 3 in the third trimester; mean age 33.4 years, range 28–40 | Focus groups with questions on feelings and experiences around being pregnant during the Zika outbreak |

| Ng et al. (2013)25 | China (Hong Kong) | SARS | 980 pregnant women of at least 16 weeks gestation; 0.6% aged younger than 18 years, 80.7% aged 18–35 years and 18.7% aged older than 35 years | Study-specific survey asking about sociodemographics, SARS knowledge, socio-economic impact of SARS and Chinese version of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory |

| Ozer et al. (2010)32 | Turkey | H1N1 | 314 pregnant women; 27.4% in the first trimester, 33.8% in the second trimester and 38.8% in the third trimester | 48-question study-specific survey covering vaccination status, factors affecting decisions about vaccinating, H1N1 vaccine side-effects and beliefs about H1N1 vaccination campaign conspiracy |

| Sakaguchi et al. (2011)33 | Canada | H1N1 | 130 pregnant women who called counselling service Motherisk for counselling regarding the safety of H1N1 vaccine; median age 33 years, range 21–45; 31.5% in the first trimester at time of call, 46.2% in the second trimester, 22.3% in the third trimester | Study-specific questionnaire including questions on vaccination status, decision-making and factors that precipitated call to Motherisk |

| Sasaki et al. (2013)34 | Japan | H1N1 | 109 pregnant women attending prenatal classes | Study-specific questionnaire measuring anxiety, satisfaction with information supplied, reasons for anxiety, prophylaxis interventions practiced |

| Sim et al. (2011)35 | Scotland and Poland | H1N1 | 10 pregnant women | Interviews covering socio-economic background, migration history, family circumstances, general health during pregnancy, views of healthcare received during pregnancy, perceptions and experience of H1N1 influenza and the vaccine, sources of information about H1N1 and the vaccine, government responses to the pandemic and decision-making about the H1N1 vaccine |

| Steelfisher et al. (2011)30 | USA | H1N1 | 514 pregnant women | Study-specific survey with approximately 84 questions relating to attitudes and experiences associated with the H1N1 vaccine |

SARS, severe acute respiratory syndrome.

A detailed summary of the thematic analysis is presented in Table 2 . It should be noted there is some overlap between themes; specifically, ‘negative emotional states’ in general emerged as a theme, but many articles also referred to negative emotions due to specific factors, which have also been classified as themes (for example, ‘concern about risk of infection’ is a negative emotional state but also a theme in itself).

Table 2.

Themes emerging from included studies.

| Theme | Reference | Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Negative emotional states | Dodgson et al. (2010)23 | Participants reported frustration, anxiety and difficulty sleeping. |

| Lee et al. (2006)24 | State anxiety was higher in pregnant women (mean score 37.2) during the SARS pandemic than in a comparative pre-SARS group (mean score 35.5, P = 0.02) while no significant difference was found in trait anxiety scores. The SARS cohort was slightly more likely to score highly on depression but not significantly. Among all, 18.4% of women felt uneasy even at home due to SARS, 54.7% felt a lack of security and 48.3% felt a loss of freedom. Participants reported worries and fears, primarily regarding the risk of infection (refer ‘concerns about risk of infection’ theme). |

|

| Linde & Siqueira (2018)26 | Participants reported sadness, uneasiness, fear, helplessness, panic, tension, responsibility, shame, failure, guilt due to pressure of having a healthy child, perceived loss of control of their own lives. | |

| Lohm et al. (2014)27 | Participants reported emotional stress. | |

| Meireles et al. (2017)31 | Participants reported a negative impact on body image due to not being able to show their bump or wear dresses that emphasised their pregnancy and having to cover up in clothing that made them feel constrained. Participants felt that others (e.g. their partners and parents) placed demands of them regarding prevention of Zika, leaving them feeling under pressure. Participants reported anxiety around the impact of the virus – refer ‘concerns about risk of infection’ subtheme. |

|

| Ng et al. (2013)25 | The mean state anxiety score (measured by the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory) was 50.4 (range 23–80). Among all, 65.2% of participants experienced moderate anxiety, 22.6% high anxiety and 12.2% low-level anxiety. Age, marital status, gestational age, parity, education level and gestational complications were not significantly associated with anxiety level, but there was a significant relationship between the state anxiety score and extent of socio-economic impact (P < 0.01) where higher anxiety was associated with higher socio-economic impact. | |

| Sasaki et al. (2013)34 | Among all, 96.3% of participants felt concerned or strongly concerned about the pandemic. Nearly, all who felt anxious cited their pregnancy as the main reason for this. | |

| Living with uncertainty | Dodgson et al. (2010)23 | Participants reported doubt and confusion about what was a true threat to themselves and their babies, often due to conflicting and constantly changing messages in the media. All reported receiving no recommendations from doctors regarding what they should and should not be doing during pregnancy and postpartum; all but two found this frustrating and said it added to their anxiety about their baby's safety. |

| Linde & Siqueira (2018)26 | Participants reported uncertainty and mistrust concerning unknown factors surrounding Zika, contributing to feelings of helplessness and distress. | |

| Lohm et al. (2014)27 | Participants reported that the unknown effects of both infection and vaccination against infection increased their emotional stress. | |

| Meireles et al. (2017)31 | Participants reported uncertainty about the impact of the virus. | |

| Concerns about infection | Lee et al. (2006)24 | Pregnant women tended to overestimate their risk of contracting SARS: 21.9% of participants believed they were likely or very likely to contract it, while 21.5% believed their newborns were likely to. Almost half (49.6%) of their participants were worried or very worried about contracting SARS themselves, while 58.1% of participants were worried or very worried about their newborn contracting it; 63.2% of participants were worried about their spouse contracting it; and 57.3% of participants were worried about relatives or friends contracting it. Among all, 46.6% were worried or very worried about infection leading to miscarriage, and 46.2% of participants were worried or very worried about infection leading to preterm delivery. Fears could lead to disrupted healthcare: 66.7% of participants feared antenatal visits in the hospital, 79.9% feared any consultations in the hospital, 12.0% cancelled appointments in the hospital and 38.9% considered doing so and 20.9% postponed appointments in the hospital while 29.1% considered doing so. |

| Lohm et al. (2014)27 | Participants reported concerns about the health of both themselves and their babies. Not knowing anyone who had the virus provided an impression of safety, and many were not too worried if they did not know of any cases. By contrast, others were mobilised into action (such as stopping work, pulling children out of school and no longer leaving the house) if the pandemic broke out in their neighbourhood. |

|

| Lynch et al. (2012)29 | Participants did not show high levels of concern: 25.2% of participants were not at all worried, and many doubted the outbreak was as severe as reported and blamed the media for generating mass hysteria. Although many did not initially perceive H1N1 to be severe or personally threatening, views shifted during group discussions and exposure to news media and raised levels of concern. Concerns about infection appeared to depend on perceptions of risk: some participants reported awareness that pregnant women were at a higher risk for H1N1 and cited pregnancy as the main reason for their concern about infection, while others believed they were less vulnerable and pregnant women had stronger immune systems due to prenatal vitamins, healthy diet and exercise. Most reported a limited understanding of the potential severity of H1N1 during pregnancy, and many were confused about how H1N1 differed from seasonal influenza. The primary source of this confusion was lack of consistent messages, particularly from the media. Concern about infection was higher among women in cities where H1N1 was most active and lower in cities where the outbreak had not yet peaked. |

|

| Meireles et al. (2017)31 | Participants reported uncertainty, anxiety and fear around the impact of the virus on both themselves and their baby. | |

| Ng et al. (2013)25 | Among all, 71.4% of participants perceived that pregnant women would have a higher risk of being infected. Eighty-nine percent of participants believed their unborn babies would be affected if they contracted it. Ninety-eight percent of participants were worried about getting infected. |

|

| Steelfisher et al. (2011)30 | Thrity-four percent of participants were concerned they might get sick from H1N1, and 49% of participants were concerned their baby might get sick. Fifty-two percent of participants believed pregnant women were more likely to become seriously ill than the general population from H1N1. | |

| Concerns about, and uptake of, prophylaxis/treatment | Lee et al. (2006)24 | Among all, 68.8% of participants were worried or very worried about foetal malformation if antiviral drugs were needed for infection. |

| Lohm et al. (2014)27 | Participants reported difficulties in deciding whether to get vaccinated or not; some delayed vaccination due to anticipating changing knowledge of the side-effects. | |

| Lyerly et al. (2012)28 | Participants universally articulated positive or neutral valuation of risks and benefits associated with the H1N1 vaccine (although it must be noted, all participants had taken part in the vaccine trial and therefore are likely to have positive views of the vaccine and are not necessarily representative of pregnant women as a whole). Many believed the risk of contracting H1N1 outweighed any theoretical risk from vaccine. Many jumped at the chance to participate in the trial due to early access to the vaccine. Notions of a growing pandemic and finite supply of vaccine made them eager to have it early, particularly women nearing the end of their pregnancies. Many felt reassured by the research question itself which was focused on dosing rather than vaccine-related harm and made the vaccine seem already safe. | |

| Lynch et al. (2012)29 | Women had concerns about both vaccinations and antiviral medicine and were not well informed about either: 41.1% of participants had low acceptance of the H1N1 vaccine, mostly due to concerns about the vaccine being untested and uncertainty about side-effects, particularly long-term side-effects for the developing foetus. Most were unaware of how antivirals work, confusing them with both antibiotics and vaccines, and some were hesitant about potential side-effects of antivirals on their unborn baby. In fact, many were cautious about taking any medications during pregnancy for the same reason. Concern about infant's well-being, however, was a strong motivator for adopting preventive recommendations including vaccination. Among all, 43.5% of participants would take antivirals such as Tamiflu. | |

| Ozer et al. (2010)32 | Of all, 8.9% of participants got the H1N1 vaccine. The percentage of participants who felt comfortable with decisions about the vaccine, who did not feel comfortable and who felt hesitant was 68.5%, 7.3% and 24.2%, respectively. Probability of receiving a vaccine was 3.46 times higher among working women than among housewives, 1.85 times higher among women who already had a child and 1.29 times higher among women with a high school education or higher. Correct knowledge about minimal risks associated with vaccine was associated with increase in receiving vaccine. Age, education, place of residence, chronic disease situation and trimester were not significantly associated with vaccination status. Among all, 70.1% of participants believed the vaccine could cause miscarriage, 74.2% thought it could cause deformation in children and 72.3% were worried vaccine could cause infertility. | |

| Sakaguchi et al. (2011)33 | Among the 104 participants who received the H1N1 vaccine, concern about risk of H1N1 in foetus and/or themselves was the most cited reason for decision (73.1%), followed by recommendations encouraging vaccination (34.6%) and previous history of complication or illness from influenza (3.8%). More than 20% of participants cited having household contacts (infant or elderly relative) or being a caregiver as contributing to decision. Among those who did not get the vaccine (n = 26), concern about safety of vaccine for themselves and/or foetus was the most cited reason (42.3%) followed by not thinking it necessary (23.1%) and previous adverse events associated with vaccinations (7.7%). | |

| Sim et al. (2011)35 | Almost all (9/10) had a critical stance towards H1N1 vaccine. Deciding whether to have the vaccine or not was difficult and anxiety provoking for all and was seen as choosing the ‘least worst’’ option in terms of competing risks. Participants identified a contradiction between the culture of caution which characterises pregnancy-related advice and being urged to accept a relatively untested vaccine. The risk of being seen as a ‘bad mother’ for whichever course of action they took heightened the anxiety surrounding decision-making. The unborn baby was the primary concern in weighing up risks and benefits of having the vaccine; the protective effect of the vaccine on the baby was a key motivator, both to protect the baby in utero and also after birth. Participants were concerned about the vaccine being relatively untested, and what was perceived to be a lack of evidence about long-term efficacy and side-effects for both women and unborn babies. |

|

| Steelfisher et al. (2011)30 | Those who were concerned about their babies getting sick were more likely to have the H1N1 vaccine (50% v 33%), as well as those who believed they themselves were at greater risk than the general population of becoming seriously ill (54% v 28%). Main reasons for not having vaccine: concerns about safety risk to unborn babies (62%) and to themselves (59%); not believing they were at risk of getting H1N1 (15%) or that they would get seriously ill from it (15%); ability to get medication if they did become sick (11%). Sixty-seven percent of participants felt the H1N1 vaccine was safe, compared with 81% who felt the seasonal influenza vaccine was safe for pregnant women. Women who believed it was safe were more likely to get the vaccine (86% v 27%). Sixty-two percent of participants discussed the vaccine with their healthcare provider. Pregnant women who received a recommendation from their healthcare provider to get the vaccine were more likely to have it (65% v 18%). |

|

| Disrupted routines | Dodgson et al. (2010)23 | Daily routines were disrupted, often leading to relationship difficulties with spouses. Examples included sleeping separately from partners if their partner had a high-risk occupation, avoiding contact with other family members, not leaving the house. Not leaving the house left participants who lived in small apartments feeling confined. Participants also did less shopping for food and baby supplies. |

| Lee et al. (2006)24 | Many participants stopped leaving the house. | |

| Linde & Siqueira (2018)26 | Participants reported eliminating leisure activities. | |

| Ng et al. (2013)25 | Decreased social activities: 4.5% not at all, 32.1% somewhat, 38% moderately, 25.4% very much. Decreased intimate contact with partner: 30.5% not at all, 40.2% somewhat, 22.3% moderately, 7% very much. Decreased social contact with friends: 16.9% not at all, 37% somewhat, 33.9% moderately, 12.3% very much. |

|

| Non-pharmaceutical protective behaviours | Dodgson et al. (2010)23 | All participants reported living in a state of intense vigilance related to hygiene measures. Behaviours included monitoring the news, gathering hygiene supplies, ensuring anyone who entered their homes abided by the current recommendations, cleaning hands vigilantly, washing bags, clothes and hair after going out, cancelling planned visits from family or banning visitors from the home entirely. |

| Lee et al. (2006)24 | Participants reported adopting behavioural strategies to mitigate their risk of contracting infection, including washing hands more than usual (91.5%), wearing masks most or all of the time (70.1%), wearing gloves most or all of the time (1.7%), rarely or never leaving the house (37.2%) and going out less than usual (54.7%). | |

| Lynch et al. (2012)29 | Likelihood of taking the following recommendations: 100% of participants would wash their hands and cover coughs; 74.6% would keep children at home; 68.1% would stay away from large gatherings; 43.9% would get alternative prenatal care such as appointments being held over the telephone or at a different location; 36.8% would wear a mask. | |

| Linde & Siqueira (2018)26 | Participants reported using repellents constantly and wearing long sleeves and closed shoes which often caused discomfort. | |

| Meireles et al. (2017)31 | Participants avoided places of risk. | |

| Ng et al. (2013)25 | Wearing a mask: 61.2% very much, 25.4% moderately, 10.6% somewhat, 2.8% not at all. Increased personal hygiene: 54.5% very much, 31.1% moderately, 10.8% somewhat, 3.6% not at all. Increased environment disinfection: 46.2% very much, 36.4% moderately, 14.6% somewhat, 2.9% not at all. Increased awareness of infection prevention: 50.8% very much, 37.8% moderately, 9.7% somewhat, 1.6% not at all. |

|

| Sasaki et al. (2013)34 | Major precautions taken included wearing a mask, stocking up on ‘prophylaxis materials’ (not clear from article what these were) and information gathering. Nearly all practiced hand washing; other measures included gargling and wearing a mask. | |

| Social support | Lee et al. (2006)24 | Women who were pregnant during the SARS outbreak reported significantly higher affectionate support (P = 0.03), positive social interaction (P = 0.01) and informational support (P = 0.03) than the pre-SARS cohort, although the groups did not differ on tangible support. Only 10.8% of the SARS cohort reported feeling lonely during the outbreak. Social support appeared to mediate symptoms of depression; the authors noted a significant negative correlation between depression scores and social support scores (P < 0.0001). |

| Financial and occupational concerns | Dodgson et al. (2010)23 | Some participants took early maternity leave from work with no pay if they worked in high-risk occupations such as healthcare. Other decreases in income were noted due to added expenses of having to use taxis as buses and subways were considered unsafe and having to spend money on masks and cleaning supplies. |

| Linde & Siqueira (2018)26 | Several participants placed careers at risk by giving up growth opportunities such as attending meetings and travelling for work; many tried to work from home or change occupation, often leading them to feel isolated from their colleagues. | |

| Meireles et al. (2017)31 | Participants reported additional expenses due to needing to buy repellents and appropriate clothing. | |

| Ng et al. (2013)25 | Among all, 24.5% of participants reported somewhat negative socio-economic impact of SARS on daily life, 27.5% moderately, 30.2% very much so, 17.8% not at all. One third stated their family's financial situation had changed. There was a significant relationship between the state anxiety score and extent of socio-economic impact (P < 0.01) Some participants made special leave arrangements from work: 43.6% not at all, 24.5% somewhat, 15.5% moderately, 16.4% very much. |

|

| Disrupted expectations of birth and prenatal/postnatal care | Dodgson et al. (2010)23 | None of the women had the birth experience they had hoped for, due to changes in hospital practices. Fifty percent of participants reported that they could not have family members visit them in the hospital; 25% of participants reported that the father was to be the only visitor; 37.5% of participants had restricted time with their own babies as they were kept separately in the hospital nursery. They had to wear masks and gowns and could not kiss their babies, while fathers could only see them through glass, leading to concerns about lack of time for bonding and attachment. There were scheduled feeding times and if they missed one they had to wait for the next. Three participants who had planned deliveries in public hospitals opted instead to pay for private hospitals; participants reported monitoring the visiting policies of their chosen hospitals as well as whether there were SARS cases in those hospitals. One chose a caesarean delivery in a private hospital as her husband would not have been allowed to accompany a natural delivery. One participant reported having to wear a mask during labour which made her sick and caused difficulty breathing. Others reported a lack of pain relief during labour (for example, not being allowed to breathe nitrous oxide to prevent the spreading of disease). Participants reported feeling a lack of connection with healthcare providers in antenatal classes (due to having to sit at the back of the room and nurses all having masks on), as well as minimal contact with medical staff and less than optimal care during delivery. Participants also reported a lack of discharge teaching, so they were sent home not knowing how to properly change nappies or bathe their babies. |

| Sources of information | Lyerly et al. (2012)28 | Participants felt they got more detailed information about the H1N1 vaccine from researchers in the vaccine trial than their doctors. |

| Lynch et al. (2012)29 | Highly trusted sources of information were healthcare providers such as obstetricians, midwives and paediatricians and government health agencies; many distrusted the media which they perceived to be benefiting financially from the outbreak, and in some cases, this distrust extended to government officials. Participants preferred the internet or social networks for communication because of immediate access and low cost. Participants with older children also recommended schools as a helpful medium for disseminating information. Most agreed that information should be disseminated in multiple ways through many channels. | |

| Sakaguchi et al. (2011)33 | More than 60% of participants reported information from direct healthcare providers or Motherisk was helpful. More than 65% of participants found information from media was confusing and unhelpful. | |

| Sasaki et al. (2013)34 | Users of municipality information reported using many more information sources than non-users. Major information sources used were television, internet and newspapers. Nearly all used television; fewer than 30% obtained information from a hospital or clinic, despite being seen regularly for appointments. Many felt that too little information was available. | |

| Sim et al. (2011)35 | Participants did not feel official information about H1N1 vaccine addressed concerns in sufficient detail and sought information from a variety of sources. Four women perceived official information about H1N1 vaccine to be a form of propaganda. All sought out alternative information primarily through social networks and the internet. Lack of information about side-effects on unborn baby was the most significant gap in official information. |

SARS, severe acute respiratory syndrome.

Negative emotional states

State anxiety was significantly higher in pregnant women during the SARS pandemic than in a comparative pre-SARS group in China,24 while another Chinese study during the SARS pandemic found that 22.6% of 980 participants reported high anxiety and 65.2% moderate anxiety.25 Other negative emotions reported across different outbreaks and in different countries included sadness, uneasiness, fear, panic, tension, loss of control of life, shame, failure and guilt due to the pressure of having a healthy child;26 unease even when at home, feeling a lack of security and a loss of freedom;24 stress;27 frustration, anxiety and sleep problems;23 pandemic-related anxiety;34 pressure from others regarding infection prevention31 and negative body image due to wearing protective clothing.31

Living with uncertainty

Participants in various countries during the SARS, Zika and H1N1 outbreaks reported living with uncertainty, mostly due to doubt and confusion about the risk to their health and that of their baby.23 , 26 , 27 , 31 Uncertainty was worsened by conflicting and rapidly changing media messages and not receiving recommendations from doctors regarding what mothers should and should not be doing during pregnancy, according to a SARS-related interview study from Hong Kong.23

Concerns about infection

Participants in various countries and experiencing different outbreaks expressed concerns about the health of themselves and their babies,24 , 25 , 27 , 29 , 31 , 30 including fears that infection could lead to miscarriage or preterm delivery.24 Concerns about infection appeared to depend on perceptions of risk: many participants in a large Chinese study of the SARS pandemic overestimated their risk of being infected25 while others in the USA during the H1N1 outbreak reported during focus groups that they believed they were less vulnerable as they believed pregnant women had stronger immune systems due to prenatal vitamins, healthy diet and exercise.29

Concerns about, and uptake of, prophylaxis/treatment

Pregnant women across many of the countries and outbreaks studied expressed concerns about antivirals24 , 29 and vaccinations,27 , 29 , 30 , 32 , 33 , 35 mostly due to potential side-effects for the developing foetus.29 , 30 , 32 , 33 , 35 Reasons for lack of uptake of vaccines included anticipating changing knowledge of side-effects,27 thinking it unnecessary33 and previous adverse vaccination effects.33 Many participants in the USA during the H1N1 outbreak reported being cautious about taking any medications at all during pregnancy;29 others in Scotland and Poland during the same outbreak noted during interviews the contradiction between the culture of caution characterising most pregnancy-related health advice and being urged to have a relatively untested vaccine.35 Conversely, motivators for receiving vaccines included concerns about infants’ well-being,28 , 29 , 33 , 35 previous history of complication or illness from influenza,33 having contact with vulnerable people33 and knowledge about the minimal risks of vaccination.32

Disrupted routines

Pregnant women's daily routines, social lives and leisure activities were disrupted as they tried to eliminate the risk of contracting the diseases.23, 24, 25, 26 Some participants in China did not leave their homes at all during the SARS pandemic23 , 24 which led to feeling confined especially when living in a small apartment.23 Relationships with spouses were affected due to decreased intimate contact25 and sleeping separately due to fear of infection.23

Non-pharmaceutical protective behaviours

Participants across different countries and outbreaks reported living in a state of vigilance related to hygiene measures and adopting new behaviours to mitigate their risk of contracting infection such as monitoring the news and information gathering;23 , 34 avoiding places of risk;23 , 29 , 31 gathering hygiene supplies;23 cleaning hands vigilantly;23 , 24 , 29 , 34 washing bags, clothes and hair after leaving the house;23 wearing masks;24 , 25 , 29 , 34 stocking up on prophylaxis materials34 and cancelling planned visits from family or banning visitors to the home altogether.23 During the Zika outbreak, participants reported using insect repellents constantly and wearing long sleeves and closed shoes which caused discomfort.26

Social support

Women pregnant during the SARS outbreak reported significantly higher affectionate support, positive social interaction and informational support than a pre-SARS cohort.24 Social support appeared to mediate symptoms of depression; the authors noted a significant negative correlation between depression and social support.

Financial and occupational concerns

In one study of SARS in Hong Kong,25 more than a third of participants reported their family's financial situation had been negatively affected by the outbreak. Participants reported increased expenses due to using taxis because buses and subways were considered unsafe23 and having to buy supplies to mitigate their risk of infection, such as masks and cleaning supplies, during the SARS pandemic23 or insect repellents and clothing during the Zika outbreak.31 Some participants took early maternity leave and forfeited pay if they worked in high-risk occupations such as healthcare23 or made special leave arrangements;25 others risked their careers by giving up career-promoting opportunities which involved attending meetings or travelling.26

Disrupted expectations of birth and prenatal/postnatal care

One interview study23 reported on disrupted expectations of birth, prenatal care and postnatal care in Hong Kong during the SARS outbreak. No participants had the birth experience they had hoped for, due to changes in hospital practices. Prenatal care was also affected: participants reported feeling a lack of connection with healthcare providers in antenatal classes due to having to keep their distance from nurses and nurses having masks on. In terms of postnatal care, participants reported a lack of discharge teaching, so they were sent home not knowing how to properly care for their babies.

Sources of information

Healthcare providers and government health agencies were generally highly trusted as sources of information.29 , 33 Many expressed distrust of the media or found it confusing and unhelpful.29 , 33 Conversely, in a Japanese quantitative study of the H1N1 outbreak, Sasaki et al.34 found that television, internet and newspapers were the most common sources of information about the H1N1 outbreak. In the study by Sim et al.,35 participants in Scotland and Poland did not feel that official information about the H1N1 vaccine addressed their concerns, particularly about potential effects on unborn babies, and sought information from a variety of sources such as social networks and the internet. It is also noteworthy that participants who had taken part in an H1N1 vaccine trial felt they had received more information from the trial's researchers than they had from their doctors.28

Discussion

This review suggests disease outbreaks can have a negative emotional impact on pregnant women, creating anxiety, distress and fear which are exacerbated by uncertainty; concerns about infection; concerns about prophylaxis or treatment; disrupted routines; financial and occupational concerns and disrupted expectations of healthcare. Intense vigilance with regards to non-pharmaceutical protective behaviours was frequently reported. Social support may be a protective factor for poor mental health although during an outbreak may be difficult to access. Given the critical role of mental health provision in combatting outbreaks such as COVID-19 and the reciprocal relationship between mental health and physical health,4 it is important to understand the implications of these findings to help inform public health interventions or campaigns.

While it is likely that outbreaks can cause anxiety for all, one study24 found that participants of a pre-SARS cohort were less anxious than a group of participants who were pregnant during the SARS outbreak; another study34 found that, nearly all participants cited that being pregnant during an outbreak was their primary reason for feeling anxious. This is concerning as previous research suggests that experiencing prenatal stress can lead to adverse birth outcomes.36 Early identification of mental health issues in perinatal patients is essential; midwives should be aware of pregnant women's propensity to experience anxiety during outbreaks and take account of the potential impact of such symptoms on their physical and mental health. Early identification of problems can allow obstetric providers to partner with mental health specialists to establish appropriate treatment plans37 and provision of public health education and mental health services specifically for pregnant women.25

Stress has been frequently linked to uncertainty across the population as a whole38 but is particularly concerning for pregnant women as previous research suggests that uncertainty can cause fear and distress in pregnancy39 which could lead to adverse birth outcomes.36 Public health officials can reduce uncertainty by ensuring that information provided to the public is timely, accurate and consistent with information from other sources. Information directly from healthcare providers and official public health organisations appears preferable. Distrust of media reporting may be prevalent across the population as a whole.40 The current outbreak advice is not to watch much media and seek information only from trusted sources;41 pregnant women can take action to avoid media if it causes anxiety.

Many participants expressed concerns about becoming infected, with some overestimating the risk of infection during pregnancy. This highlights the need for timely dissemination of accurate public health information and for clinicians to monitor for overestimation of risk among pregnant women and clear up misconceptions. Where simple advice and reassurance does not work, there may be benefit in brief psychotherapy using a cognitive-behavioural model to reduce anxiety and the associated risk of pregnancy complications.42 , 43

Concerns about prophylaxis or treatment were prevalent, perhaps unsurprisingly as pregnant women have historically low vaccination rates for seasonal influenza44 and pandemic influenza.45 , 46 The decision about whether to receive vaccines or medications may be distressing as pregnancy is already a time when women are faced with cultural expectations of motherhood and any examples of not abiding by advice can lead to women being seen as undisciplined.47 It is essential that pregnant women are aware of trustworthy, up-to-date information about the risks and benefits of vaccines and medications, particularly given the potential for pregnant women to be identified as a priority group for any vaccination programme as was the case in the UK during the H1N1 pandemic.48

Participants reported disrupted routines and changes to relationships with others due to social distancing. This is concerning as social support is essential in enhancing resilience during times of crisis49 while poor social support is associated with negative psychological outcomes,50 as is the isolation felt by people quarantined during pandemics.51 Mental health campaigns aimed at encouraging communication via phone or internet during physical isolation may be useful.51 Support from others with similar experiences can be particularly helpful to alleviate stress in pregnancy,52 and social media is a substantial source of support for pregnant women and new mothers53; therefore, virtual support groups specifically for pregnant women to support each other may be beneficial. Some of these recommendations (particularly concerning signposting to resources and the use of social media to connect with others) are reflected in existing public health guidance for maintaining good mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic.3

Financial and occupational concerns were common; these are stressors for many people during pandemics.51 Pregnant women – and the public as a whole – would benefit from ensuring they are aware of financial assistance available during the pandemic and how and when it can be claimed.54 In particular, the COVID-19 outbreak may be stressful for pregnant women who are ‘critical workers’ and therefore expected to continue working,55 despite also being told they are a vulnerable group who should be ‘particularly stringent in following social distancing measures’.9 Organisations could help by changing the work roles of pregnant women, so they can work from home or away from the public where possible.

Participants in one study reported an overwhelming disruption in their expectations of birth, prenatal care and postnatal care, causing them to change their birth plans. In addition, maternity staff levels may be lower than usual during a pandemic due to reassignment of staff to other areas of the hospital or staff minimising contact with patients for their own protection. This raises the question of what is an acceptable level of care to provide to uninfected pregnant women during a pandemic.23 Guidance for healthcare professionals needs to be clear about which routine visits could be done over the phone or cancelled altogether, as well as how to provide appropriate care without exposing healthy women to illness. A solution may be designating a location and staff specifically for the care of healthy pregnant women.56

The literature showed that pregnant women often cope by taking drastic non-pharmaceutical precautions to avoid infection, which may affect all areas of their lives. They may become hypervigilant with regard to monitoring the most current self-protection information available, hygiene practices and reducing contact with others. These practices are recommended in infectious disease outbreaks and in themselves are positive behaviours as they reduce infection risk. However, it is possible that such measures could also cause distress. More research is needed to explore the benefits and risks to mental health of prolonged hypervigilance.

This review enhances understanding of how being pregnant during an emerging infectious disease outbreak may affect maternal mental health. Owing to the unpredictable nature of disease outbreaks, large numbers of women may find themselves pregnant during a pandemic, something they are unlikely to have expected or planned for. The psychological impact of pandemics may affect their mental health which could subsequently affect their children and families.

Overall, this review supports the suggestion that pregnant women are a highly vulnerable group in terms of psychological consequences during a pandemic;57 they need to care for both their own health and that of their unborn child, in a ‘doubling of health responsibilities’.27 Planning for future pandemics should make considerations specific to pregnant women: involving them in pandemic preparedness exercises would ensure that their voices are heard and helping policymakers identify any gaps related to prenatal and postnatal care in current pandemic planning.

Limitations

Data screening, extraction and analysis were carried out by one author; in typical systematic reviews, it is preferable for double screening to take place and multiple reviewers to analyse the data. However, the results were discussed between all authors as the article went through multiple revisions before submission. Searches were limited to English language articles, meaning evidence may have been missed. No standardised quality appraisal of the included articles was carried out, as is common in rapid evidence reviews.58 However, there were some particularly notable limitations to the literature, such as low response rates and a lack of quantitative research. Only one study24 compared mental health outcomes for women pregnant during an outbreak with preoutbreak pregnant controls, making it difficult to ascertain the mental health–related differences in being pregnant during a disease outbreak and at any other time. No research directly compared pregnant women with non-pregnant individuals during an outbreak, so again, we cannot say whether pregnant women are more likely to experience stress during an outbreak than the general population. However, it is not unreasonable to think that the combination of usual pregnancy concerns and pandemic-related concerns may result in particularly negative psychological outcomes.

Conclusion

Pregnant women have specific needs during a pandemic and may be at risk of adverse psychological effects of the COVID-19 outbreak. This is important as there is a clear link between poor mental health in pregnant women and pregnancy complications. It is vital they are well informed about public health recommendations, which should include detailed description of benefits or lack of risk to unborn babies, as well as clear rationale for why prophylaxis or treatment is necessary. Virtual support groups specifically for pregnant women may be useful. Healthcare professionals involved in the care of pregnant women should be aware of the most current guidance and ensure that they closely monitor mental health during pregnancy and where necessary provide early evidence-based care.

Author statements

Ethical approval

Not required as no original data collected.

Funding

The research was funded by the National Institute for Health Research Health Protection Research Unit (NIHR HPRU) in Emergency Preparedness and Response at King's College London in partnership with Public Health England (PHE), in collaboration with the University of East Anglia. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, the Department of Health and Social Care or Public Health England. DW is also a member of the NIHR Health Protection Research Unit in Behavioural Science and Evaluation at University of Bristol. The funding source had no role in study design; the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; the writing of the article or the decision to submit it for publication.

Competing interests

None declared.

Appendix I. Search strategy

-

1.

pregnant OR pregnanc∗

-

2.

psychological OR mental health OR trauma OR stress OR distress OR anxiety OR well-being OR well-being OR panic OR depress∗

-

3.

pandemic∗ OR disease outbreak∗ OR SARS OR severe acute respiratory syndrome OR swine flu OR H1N1 OR avian influenza OR bird flu OR H5N1 OR Ebola OR MERS OR Middle East respiratory syndrome OR Zika OR coronavirus OR COVID-19.

-

4.

1 AND 2 AND 3.

References

- 1.Worldometer COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic. https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/

- 2.Gardner P.J., Moallef P. Psychological impact on SARS survivors: critical review of the English language literature. Can Psychol. 2015;56(1):123–135. doi: 10.1037/a0037973. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Public Health England . 2020. Guidance for the public on the mental health and wellbeing aspects of coronavirus (COVID-19)https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/covid-19-guidance-for-the-public-on-mental-health-and-wellbeing/guidance-for-the-public-on-the-mental-health-and-wellbeing-aspects-of-coronavirus-covid-19 accessed. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Public Health England . 2020. No health without mental health: why this matters now more than ever.https://publichealthmatters.blog.gov.uk/2020/05/21/no-health-without-mental-health-why-this-matters-now-more-than-ever/ accessed. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mosby L.G., Rasmussen S.A., Jamieson D.J. Pandemic influenza A (H1H1) in pregnancy: a systematic review of the literature. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;205(1):10–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.12.033. 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lam C.M., Wong S.F., Leung T.N., Chow K.M., Yu W.C., Wong T.Y. A case-controlled study comparing clinical course and outcomes of pregnant and non-pregnant women with severe acute respiratory syndrome. BJOG An Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;111:771–774. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00199.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schwartz D.A., Graham A.L. Potential maternal and infant outcomes from (Wuhan) Coronavirus 2019-nCoV infecting pregnant women: lessons from SARS, MERS, and other human coronavirus infections. Viruses. 2020;12(2):194. doi: 10.3390/v12020194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dashraath P., Jing Lin Jeslyn W., Mei Xian Karen L., Li Min L., Sarah L., Biswas A. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Public Health England . 2020. Guidance on social distancing for everyone in the UK.https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/covid-19-guidance-on-social-distancing-and-for-vulnerable-people/guidance-on-social-distancing-for-everyone-in-the-uk-and-protecting-older-people-and-vulnerable-adults accessed. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jamieson D.J., Theiler R., Rasmussen S.A. Emerging infections and pregnancy. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12(11):1638–1643. doi: 10.3201/eid1211.060152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jamieson D.J., Ellis J.E., Jernigan D.B., Treadwell T.A. Emerging infectious disease outbreaks: old lessons and new challenges for obstetrician-gynecologists. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194:1546–1555. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.06.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee C.-H., Huang N., Chang H.-J., Hsu Y.-J., Wang M.-C., Chou Y.-J. The immediate effects of the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) epidemic on childbirth in Taiwan. BMC Publ Health. 2005;5:30. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-5-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patterson J., Hollins Martin C., Karatzias T. PTSD post-childbirth: a systematic review of women's and midwives‘ subjective experiences of care provider interaction. J Reprod Infant Psychol. 2018;37(1):56–83. doi: 10.1080/02646838.2018.1504285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oppenheim M. 2020. Pregnant women forced to give birth without support in hospital amid coronavirus outbreak.https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/coronavirus-pregnant-women-birth-hospital-nhs-parents-advice-a9439391.html accessed. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kahn M., Cristoferi C. 2020. Anxiety, anger and hope as women face childbirth during coronavirus pandemic.https://uk.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-europe-childbirth/anxiety-anger-and-hope-as-women-face-childbirth-during-coronavirus-pandemic-idUKKBN21E1O2 accessed. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stevenson A. 2020. ‘I felt like crying’: coronavirus shakes China's expecting mothers.https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/25/business/coronavirus-china-pregnant.html accessed. [Google Scholar]

- 17.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Hospital disaster preparedness for obstetricians and facilities providing maternity care. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(6):e291–e297. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buekens P., Alger J., Breart G., Cafferata M.L., Harville E., Tomasso G. A call for action for COVID-19 surveillance and research during pregnancy. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8(7):e877–e878. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30206-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization . 2017. Rapid reviews to strengthen health policy and systems: a practical guide.https://www.who.int/alliance-hpsr/resources/publications/rapid-review-guide/en/ accessed. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chakhtoura N., Hazra R., Spong C.Y. Zika virus: a public health perspective. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2019;30(2):116–122. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0000000000000440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Health Organization . 2014. A brief guide to emerging infectious diseases and zoonoses. WHO Regional Office for South-East Asia.https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/204722 accessed. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Braun V., Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dodgson J.E., Tarrant M., Chee Y.-O., Watkins A. New mothers' experiences of social disruption and isolation during the severe acute respiratory syndrome outbreak in Hong Kong. Nurs Health Sci. 2010;12(2):198–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2018.2010.00520.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee D.T.S., Sahota D., Leung T.N., Yip A.S.K., Lee F.F.Y., Chung T.K.H. Psychological responses of pregnant women to an infectious outbreak: a case-control study of the 2003 SARS outbreak in Hong Kong. J Psychosom Res. 2006;61(5):707–713. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2006.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ng J., Sham A., Leng Tang P., Fung S. SARS: Pregnant women's fears and perceptions. Br J Midwifery. 2004;12(11):698–703. doi: 10.12968/bjom.2004.12.11.16710. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Linde A.R., Siqueira C.E. Women's lives in times of Zika: mosquito-controlled lives? Cad Saúde Pública. 2018;34(5) doi: 10.1590/0102-311X00178917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lohm D., Flowers P., Stephenson N., Waller E., Davis M.D.M. Biography, pandemic time and risk: pregnant women reflecting on their experiences of the 2009 influenza pandemic. Health. 2014;18(5):493–508. doi: 10.1177/1363459313516135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lyerly A.D., Namey E.E., Gray B., Swamy G., Faden R.R. Women's views about participating in research while pregnant. IRB Ethics Hum Res. 2012;34(4):1–8. PMID: 22893991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lynch M.M., Mitchell E.W., Williams J.L., Brumbaugh K., Jones-Bell M., Pinkney D.E. Pregnant and recently pregnant women's perceptions about influenza A pandemic (H1N1) 2009: implications for public health and provider communication. Matern Child Health J. 2012;16:1657–1664. doi: 10.1007/s10995-011-0865-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Steelfisher G.K., Blendon R.J., Bekheit M.M., Mitchell E.W., Williams J., Lubell K. Novel pandemic A (H1N1) influenza vaccination among pregnant women: motivators and barriers. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204(6 Suppl 1):S116–S123. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.02.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meireles J.F.F., Neves C.M., da Rocha Morgado F.F., Ferreira M.E.C. Zika vírus and pregnant women: a psychological approach. Psychol Health. 2017;32(7):798–809. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2017.1307369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ozer A., Arikan D.C., Kirecci E., Ekerbicer H.C. Status of pandemic influenza vaccination and factors affecting it in pregnant women in Kahramanmaras, an Eastern Mediterranean city of Turkey. PloS One. 2010;5(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sakaguchi S., Weitzner B., Carey N., Bozzo P., Mirdamadi K., Samuel N. Pregnant women's perception of risk with use of the H1N1 vaccine. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2011;33(5):460–467. doi: 10.1016/S1701-2163(16)34879-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sasaki T.-K., Yoshida A., Kotake K. Attitudes about the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic among pregnant Japanese women and the use of the Japanese municipality as a source of information. SE Asian J Trop Med. 2013;44(3):388–399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sim J.A., Ulanika A.A., Katikireddi S.V., Gorman D. ‘Out of two bad choices, I took the slightly better one’: vaccination dilemmas for Scottish and Polish migrant women during the H1N1 influenza pandemic. Publ Health. 2011;125(8):505–511. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2011.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pais M., Pai M.V. Stress among pregnant women: a systematic review. J Clin Diagn Res. 2018;12(5):LE01–4. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2018/30774.11561. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maher M.J. Emergency preparedness in obstetrics: meeting unexpected key challenges. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 2019;33(3):238–245. doi: 10.1097/JPN.0000000000000421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grupe D.W., Nitschke J.B. Uncertainty and anticipation in anxiety: an integrated neurobiological and psychological perspective. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013;14(7):488–501. doi: 10.1038/nrn3524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Melander H. Experiences of fears associated with pregnancy and childbirth: a study of 329 pregnant women. Birth. 2002;29(2):101–111. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-536x.2002.00170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goodall C., Sabo J., Cline R., Egbert N. Threat, efficacy, and uncertainty in the first 5 months of national print and electronic news coverage of the H1N1 virus. J Health Commun. 2012;17(3):338–355. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2011.626499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Williamson V., Murphy D., Greenberg N. COVID-19 and experiences of moral injury in front-line key workers. Occup Med. 2020;70(5):317–319. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqaa052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Asghari E., Faramarzi M., Mohammmadi A.K. The effect of cognitive behavioural therapy on anxiety, depression and stress in women with preeclampsia. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10(11):QC04–7. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2016/21245.8879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Goodman J.H., Guarino A., Chenausky K., Klein L., Prager J., Petersen R. CALM pregnancy: results of a pilot study of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for perinatal anxiety. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2014;17(5):373–387. doi: 10.1007/s00737-013-0402-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yuen C.Y.S., Tarrant M. Determinants of uptake of influenza vaccination among pregnant women – a systematic review. Vaccine. 2014;32:4602–4613. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.06.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fridman D., Steinberg E., Azhar E., Weedon J., Wilson T.E. Predictors of H1N1 vaccination in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204(6):S124–S127. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.04.011. S1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schmid P., Rauber D., Betsch C., Lidolt G., Denker M.-L. Barriers of influenza vaccination intention and behavior – a systematic review of influenza vaccine hesitancy. PloS One. 2017;12(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0170550. 2005-2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bessett D. Negotiating normalization: the perils of producing pregnancy symptoms in prenatal care. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71:370–377. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hine D. 2010. The 2009 influenza pandemic: an independent review of the UK response to the 2009 influenza pandemic.https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/61252/the2009influenzapandemic-review.pdf accessed. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brooks S.K., Amlot R., Rubin G.J., Greenberg N. Psychological resilience and post-traumatic growth in disaster-exposed organisations: overview of the literature. BMJ Military Health. 2020;166(1):52–56. doi: 10.1136/jramc-2017-000876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Goldmann E., Galea S. Mental health consequences of disasters. Annu Rev Publ Health. 2014;35:169–183. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brooks S.K., Webster R.K., Smith L.E., Woodland L., Wessely S., Greenberg N. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395(10227):912–920. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McLeish J., Redshaw M. Mothers' accounts of the impact on emotional wellbeing of organised peer support in pregnancy and early parenthood: a qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17:28. doi: 10.1186/s12884-017-1220-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Baker B., Yang I. Social media as social support in pregnancy and the postpartum. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2018;17:31–34. doi: 10.1016/j.srhc.2018.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Treasury H.M. 2020. Support for those affected by COVID-19.https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/support-for-those-affected-by-covid-19/support-for-those-affected-by-covid-19 accessed. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cabinet Office . 2020. Guidance for schools, childcare providers, colleges and local authorities in England on maintaining educational provision.https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/coronavirus-covid-19-maintaining-educational-provision/guidance-for-schools-colleges-and-local-authorities-on-maintaining-educational-provision accessed. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rasmussen S.A., Jamieson D.J., Bresee J.S. Pandemic influenza and pregnant women. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14(1):95–100. doi: 10.3201/eid1401.070667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Thapa S.B., Mainali A., Schwank S.E., Acharya G. Maternal mental health in the time of the COVID-19 pandemic. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2020;99(7):817–818. doi: 10.1111/aogs.13894. https://doi:10.1111/aogs.13894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Haby M.M., Chapman E., Clark R., Barreto J., Reveiz L., Lavis J.N. What are the best methodologies for rapid reviews of the research evidence for evidence-informed decision making in health policy and practice: a rapid review. Health Res Pol Syst. 2016;14(1):83. doi: 10.1186/s12961-016-0155-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]