Abstract

Background

As a pooled donor blood product, cryoprecipitate (cryo) carries risks of pathogen transmission. Pathogen inactivation (PI) improves the safety of cryoprecipitate, but its effects on haemostatic properties remain unclear. This study investigated protein expression in samples of pathogen inactivated cryoprecipitate (PI-cryo) using non-targeted quantitative proteomics and in vitro haemostatic capacity of PI-cryo.

Materials and methods

Whole blood (WB)- and apheresis (APH)-derived plasma was subject to PI with INTERCEPT® Blood System (Cerus Corporation, Concord, CA, USA) and cryo was prepared from treated plasma. Protein levels in PI-cryo and paired controls were quantified using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Functional haemostatic properties of PI-cryo were assessed using a microparticle (MP) prothrombinase assay, thrombin generation assay, and an in vitro coagulopathy model subjected to thromboelastometry.

Results

Over 300 proteins were quantified across paired PI-cryo and controls. PI did not alter the expression of coagulation factors, but levels of platelet-derived proteins and platelet-derived MPs were markedly lower in the WB PI-cryo group. Compared to controls, WB (but not APH) cryo samples demonstrated significantly lower MP prothrombinase activity, prolonged clotting time, and lower clot firmness on thromboelastometry after PI. However, PI did not affect overall thrombin generation variables in either group.

Discussion

Data from this study suggest that PI via INTERCEPT® Blood System does not significantly impact the coagulation factor content or function of cryo but reduces the higher MP content in WB-derived cryo. PI-cryo products may confer benefits in reducing pathogen transmission without affecting haemostatic function, but further in vivo assessment is warranted.

Keywords: data-independent acquisition, DIA, microflow liquid chromatography, cryoprecipitate, pathogen inactivation

INTRODUCTION

Cryoprecipitate (cryo) is utilised for fibrinogen supplementation in the setting of acquired hypofibrinogenaemia and bleeding from trauma and surgery1–3. Transmission of infectious organisms is a potential adverse effect of cryo transfusion, especially given the administration from pooled donors. To minimise transfusion-transmitted infections, pathogen inactivation (PI) technologies have been introduced to mitigate organism burden. The four major methods of PI are solvent detergent, methylene blue with visible light, amotosalen with UV light, and ribof lavin with UV light4–6. The INTERCEPT® Blood System (Cerus Corporation, Concord, CA, USA) is one example of a US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved PI technology that utilises a psoralen-derivative (amotosalen) and UVA light to cross-link nucleic acids and form mono-adducts to render organisms including viruses, bacteria, and protozoa non-viable. Previous studies assessing the impact of different PI technologies on plasma-derived blood products have demonstrated mixed results regarding residual coagulation factor activity and thrombin generation after PI treatment7–11.

With the introduction of omics technologies, investigations into the impacts of various blood product treatments have emerged12,13. Although evaluations of filtered plasma have demonstrated limited changes to the proteomic profile with amotosalen/UVA light treatment14, little has been done to assess the particular effects of PI on derived cryo products with this technology. Traditionally, quantitative and qualitative changes in cryo procoagulants have been investigated using factor activity assays4,7,11. The advent of robust quantitative proteomic approaches for plasma analysis, which have increasingly used data-independent acquisition15–17, offers the opportunity to evaluate a wider protein profile of cryo. Furthermore, while previous studies have assessed the impact of PI on whole blood-derived cryo4,11,18, the possible impact on apheresis (APH)-derived cryo has not been assessed.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the effects of PI with amotosalen and UVA light on total protein content, thrombin generation, and the effect on clot strength of cryoprecipitate prepared from whole blood (WB)- and APH-derived plasma before and after the PI process. Specifically, protein expression was quantified using mass spectrometry-based proteomics, thrombin generation was assessed using a microparticle (MP)-supported prothrombinase assay (Zymuphen-MP Activity, Aniara Diagnostica, West Chester, OH, USA) and thrombin generation assay (Calibrated Automated Thrombogram, Diagnostica Stago Inc., Parsippany, NJ, USA), and clot strength was measured using an in vitro model of dilutional coagulopathy and thromboelastometry (ROTEM Delta, Instrumentation Laboratory, Bedford, MA, USA). We tested the hypothesis that there is no difference in the activity of paired samples of cryoprecipitate prepared from plasma before and after amotosalen/UVA light treatment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study was granted a waiver of Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval by the Duke University IRB as no donor data were collected.

Cryoprecipitate units

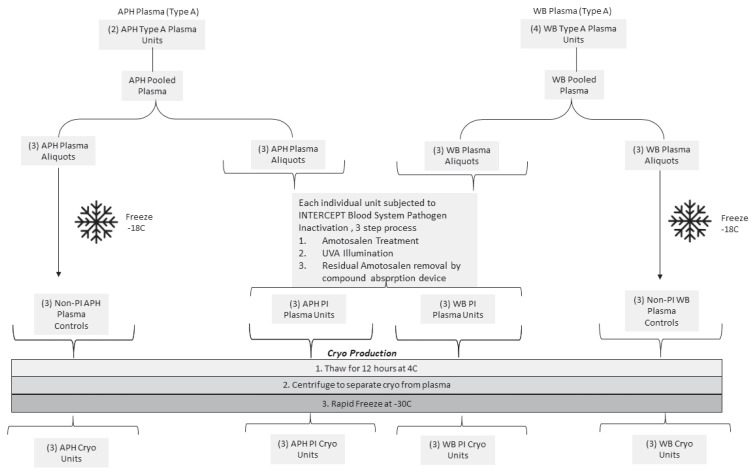

Group A plasma units were prepared at Vitalant Corporation (Scottsdale, AZ, USA). The APH-derived and WB-derived plasma pools were prepared in parallel by pooling two units of APH plasma and separately pooling four units of WB plasma and splitting each of the two pools into six equal-volume aliquots (12 total; 6 APH, 6 WB). WB plasma was manufactured via the platelet rich plasma (PRP) method19. From each set of six aliquots, three plasma aliquots were subjected to PI with the INTERCEPT® Blood System (Cerus Corporation) and three plasma aliquots were not treated and left as control plasma units (Figure 1). Plasma aliquots subjected to PI were processed utilising the INTERCEPT® Blood System as per the manufacturer’s instructions, as previously described6,20. Briefly, plasma was subject to three steps in the treatment system. First, plasma units were connected to the amotosalen container in sterile conditions and plasma passed through the amotosalen container into the INTERCEPT® UVA illumination container, yielding a plasma-amotosalen mixture with approximate amotosalen concentration of 150 μmol/L. Secondly, the plasma-amotosalen mixture was subject to illumination with a 3 J/cm2 UVA light treatment (320–400 nm). Lastly, the UVA-treated plasma-amotosalen mixture was transferred via gravity flow through a compound adsorption device to reduce the residual amotosalen concentration (<2 μmol/L) and simultaneously collect the PI plasma into final storage containers.

Figure 1.

Workflow for cryoprecipitate preparation. Starting material included 4 units of whole blood (WB)-derived and 2 units of apheresis (APH)-derived plasma

WB- and APH-derived cryo control samples were not subject to the pathogen inactivation. (PI) process.

Cryo was subsequently manufactured at Cerus Corporation as previously described21. Both PI and non-treated (control) plasma units were frozen at −18 °C then thawed for approximately 12 hours (h) at 4 °C. Cryo was subsequently separated from plasma by centrifugation and rapidly frozen at −30 °C. Finally, PI-cryo and controls (cryo) were thawed at 37 °C for 15 minutes (min) in a Thermomixer (Eppendorf, New York, NY, USA) and distributed into 1.5 mL cryovials and frozen at −80 °C until ready for evaluation.

Proteomic sample preparation

Samples in cryovials were thawed at 37 °C for 15 min in a Thermomixer and briefly centrifuged to remove condensate from tube lids. 10 μL samples were diluted 50-fold in 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate (Ambic) and used for Bradford assay. Next, 20 μL of each sample was diluted to 200 μL with 5.5% (w/v) sodium deoxycholate (SDC) in Ambic followed by addition of 10 mM DTT and heated at 80 °C for 10 min on a Thermomixer. Next, samples were alkylated by addition of 25 mM iodoacetamide and incubation for 30 min at room temperature in the dark. Excess IAM was quenched by an additional 10 mM DTT, and samples were digested with 1:10 (w/w) TPCK trypsin at 37 °C for 4 h. The SDC was precipitated by addition of 1% v/v trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) and 2% (v/v) acetonitrile (MeCN) followed by centrifugation. Samples were transferred to Maximum Recovery LC Vials (Waters, Milford, MA, USA). A quality control (QC) pool was made by mixing equal volumes of the 12 cryo samples.

Quantitative proteomic analysis using data-independent acquisition-LC-MS/MS

Individual samples and three replicates of the QC pool were analysed by data-independent acquisition (DIA)-LC-MS/MS (see Online Supplementary Content, Table SI for run order). For each analysis, peptides were separated by microflow LC-MS/MS using an ACQUITY UPLC (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA, USA) interfaced to a Q-Exactive HF-X mass spectrometer (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) as previously described22. Briefly, 14 μL of peptide digest (~50 μg) was separated on a 1 mmx150 mm 1.7 μm CSH C18 column using a flow rate of 100 μL/min, a column temperature of 55 °C and a gradient of 3–28% (v/v) MeCN: H2O containing 0.1% formic acid over 60 min. The column was interfaced to the HF-X via a heated electrospray ionisation (HESI) source with tune parameters: sheath gas, 35; auxiliary gas, 10; sweep gas, 1; spray voltage, 3.5 kV; capillary temperature, 250 °C; funnel RF, 40; auxiliary gas heater temperature, 200 °C. DIA-MS analysis used a 120,000 resolution precursor ion (MS1) scan from 375–1,500 m/z, AGC target of 3E6, and maximum injection time (IT) of 20 milliseconds (ms). DIA-MS/MS was performed using 30,000 resolution, AGC target of 3E6 and maximum IT of 60 ms, and 27 V NCE. The DIA windows included 15×37 m/z windows spanning 400–941 m/z with 1 m/z overlaps; as well as 3×87 m/z windows spanning 941–1,200 m/z. The approximate cycle time was 1.7 seconds (s), and the total injection-to-injection time was 67 min. The raw mass spectrometry proteomics data, the spectral library, Spectronaut. SNE file and associated results and metadata have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the MassIVE partner repository (ftp://massive.ucsd.edu/MSV000085374/) with the dataset identifier PXD018986.

Spectral library generation and DIA analysis

Spectronaut Pulsar X (Biognosys AG, Schlieren, Switzerland) was used for database searching, spectral library matching, and peptide/protein quantification. Individual DIA runs were searched used a UniProt database with homo sapiens specificity (downloaded on 16 August 2016 and containing 20,197 entries). Default settings were used (e.g., Trypsin/P specificity; up to 2 missed cleavages; peptide length from 7–52 amino acids) and in addition allowed for semitryptic peptide N-termini and variable peptide N-terminal Gln to pyroGlu. The library was also populated with data-dependent analysis of high pH-reserved phase (HPRP) fractions of pooled plasma and serum using the “Import Search Archive” option. The final library contained 660 protein groups and 26,000 precursors.

Data analysis in Spectronaut used default settings with the following modifications: quantification settings used sum peptide quantity, data filtering used Qvalue percentile of 0.1, and global normalisation was performed using the median values of precursors identified in all runs (Qvalue complete); workflow settings used iRT profiling with carry-over of exact peak boundaries, automatic selection of profiling with minimum Qvalue of 0.01, and unify peptide peaks enabled. Manual data curation was performed to remove non-correlating peptides based on QC pool data. Peptide precursor and Protein group expression data were exported (Online Supplementary Content, Table SII and SIII).

Microparticle prothrombinase activity assay

Preliminary investigations using flow cytometry with a MP size gate set between 0.2 μm and 1 μm identified numerous microparticles in cryo that were capable of generating thrombin, including red cell-derived (CD235a), neutrophil-derived (CD11b), lymphocyte-derived (CD4), platelet-derived (CD41), monocyte-derived (CD14), leukocyte antigen-derived (HLA class I), and leukocyte-derived MP (CD45) subsets. MP prothrombinase activity was assayed using the Zymuphen® MP-Activity kit, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Aniara Diagnostica), as previously described23. Samples of cryo (500 μL starting volume) were centrifuged (4,000 g × 10 min) to remove large debris. Procedures were carried out according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Samples were diluted as needed to fall within the standard curve.

Thrombin generation assay

Measurement of thrombin generation was performed using the Calibrated Automated Thrombogram (CAT) instrument (Diagnostica Stago Inc., Parsippany, NJ, USA). For each U-bottom plate, PPP-Reagent LOW (1 pM tissue factor) and a thrombin calibrator control were reconstituted with 1 mL of deionised water and allowed to sit for 10 min. After 10 min, the vials were carefully shaken and 20 μL was pipetted into the appropriate wells according to the plate setup. Previously aliquoted cryo samples in 1.5 mL cryovials were thawed at 37 °C for 15 min in a Plasmatherm dry water incubator (Barkey GmbH & Co., Leopoldshöhe, Germany) and then 80 μL of cryo was loaded into the appropriate wells. The plate was placed in the instrument for 10 min to warm to 37 °C. The CAT instrument was primed and 2,660 μL of warm Fluo-Buffer with 65 μL of Fluo-Substrate was prepared and added to the instrument. The automated dispensing of 20 μL FluCa (Fluo-Buffer and Fluo-Substrate mix) started the measurement process. For each trial, each well was measured every 20 s for 60 min. Upon completion of the measurement, the Thrombinoscope Software (Stago Group, Maastricht, The Netherlands) was used to analyse the results.

Rotational thromboelastometry functional analysis

Thromboelastometry analyses were performed on a validated rotational thromboelastometry device (ROTEM Delta, Instrumentation Laboratory). Daily internal and weekly external quality control were performed according to the manufacturer’s guidelines. All thromboelastometry assays were performed using the EXTEM (tissue factor triggered extrinsic pathway) test on an in vitro dilutional model of coagulopathy. This in vitro model was plasma-based (in absence of platelets) rather than WB-based. Individual assays were prepared according to EXTEM protocol instructions and stopped upon obtaining maximum clot firmness (MCF) data points. Three variables were measured and recorded: clotting time (CT), MCF, and alpha angle. Cryo and pooled normal plasma were thawed in a water bath at 37 °C for 15 min and all assays were completed within 120 min of blood product thawing to ensure cryo stability and reproducibility24.

The in vitro model of dilutional coagulopathy was established by diluting pooled normal plasma (PNP) (George King Biomedical Inc., Overland, KS, USA) with crystalloid solution (0.9% sodium chloride, Baxter International, Deerfield, IL, USA) in a 1:1 ratio to a 50% haemodilution as previously described21. The haemodiluted PNP model was subsequently used to simulate the effect of successive typical in vivo transfusions of 100 mL (10 units) of cryo1,25. Diluted PNP solutions were created in volumes to run EXTEM assays for each cryo unit in triplicate. The total haemodiluted volume was aliquoted into four cryovials for subsequent supplementation with cryo (Online Supplementary Content, Table SIV). Based on a typical adult dose of cryo (100 mL or 10 units) and a standard adult 3 L circulating plasma volume (5 L total blood volume with 40% haematocrit)1,25,26, volumes of cryo were calculated to simulate the administration of 1 (D1), 2 (D2), and 3 (D3) cryo doses to the diluted plasma sample used for thromboelastometry (Online Supplementary Content, Table SIV). Baseline thromboelastometry values were obtained for the diluted PNP model without supplementation of cryo (dilute-D0) as a coagulopathic control. Thromboelastometry values were also obtained for non-diluted PNP without supplementation of cryo (non-dilute-D0) as a non-coagulopathic control.

Statistical analysis

For proteomic analysis, a percentile cut-off of 10% (i.e., peptide precursors identified in at least 10% of the samples) were included for quantification. Robust quantification was defined as ≥2 quantified peptides and a coefficient of variation (CV) <30% across quality control (QC) pool replicates. Fold-changes were calculated by averaging ratios from each of the three unique cryo samples. Comparisons between PI and cryo groups were performed on log2-transformed data using paired Student’s t-test. Data were analysed using Microsoft Excel.

Prothrombinase activity was examined by comparing mean phosphatidyl serine (PS) equivalent (nM) values between PI-cryo and cryo samples in the Zymuphen® assay. Tests were conducted separately in APH and WB samples. Due to the small sample size, a permutation test was used to compare the groups.

Thrombin generation variables collected include lag-time (min), endogenous thrombin potential (ETP) (nM*min), thrombin peak (nM), time to peak (ttPeak) (min), and velocity index (nM/min). All variables are expressed as mean (standard deviation, SD). PI-cryo and cryo controls, and WB-derived and APH-derived cryo samples were compared between groups utilizing Wilcoxon Rank-Sum tests. Due to the exploratory nature of the analysis, p-values were not adjusted for multiple comparisons. Reference ranges for thrombin generation test variables were based on prior literature of calibrated automated thrombography assessing platelet-poor plasma with PPP-Reagent LOW (1 pM tissue factor) reported as 3 standard deviation reference intervals27. Reference ranges are not available for all parameters due to the units of results reported in prior literature27.

For each of the three ROTEM parameters (clotting time, maximum clot firmness, and alpha angle) a mixed effects linear regression model was fit. Each model included fixed effects for cryo dose, cryo-derivation source (WB or APH), and PI treatment. As each sample was measured multiple times and across multiple conditions, each model also had a random effect for cryo sample. A stratified analysis was also conducted by fitting similar models with data from WB samples and APH samples separately. In each group of samples, a mixed effects linear regression model was constructed with fixed effects for cryo dose and PI treatment as well as a random effect for cryo sample. In all models, significance of fixed effects was assessed using type III tests and, in all tests, p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analysis was carried out using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) and R version 3.5.0 (https://cran.r-project.org/) unless otherwise noted.

RESULTS

Platelet proteins are differentially expressed in pathogen inactivated WB-derived cryo

We first sought to quantify changes in WB- or APH-derived cryoprecipitate proteome after PI using a “bottom-up” mass spectrometry-based proteomic approach. Using data-independent acquisition (DIA), we quantified 12,358 precursors and 344 protein groups in tryptic digests of matched WB- and APH-derived cryo from 3 independent donors, with and without PI. Of these, 300 proteins were selected for statistical analysis based on quantification by 2 or more precursors and a %CV of <30% in triplicate measurements of a QC pool, which represents the average concentration across all samples (see Methods).

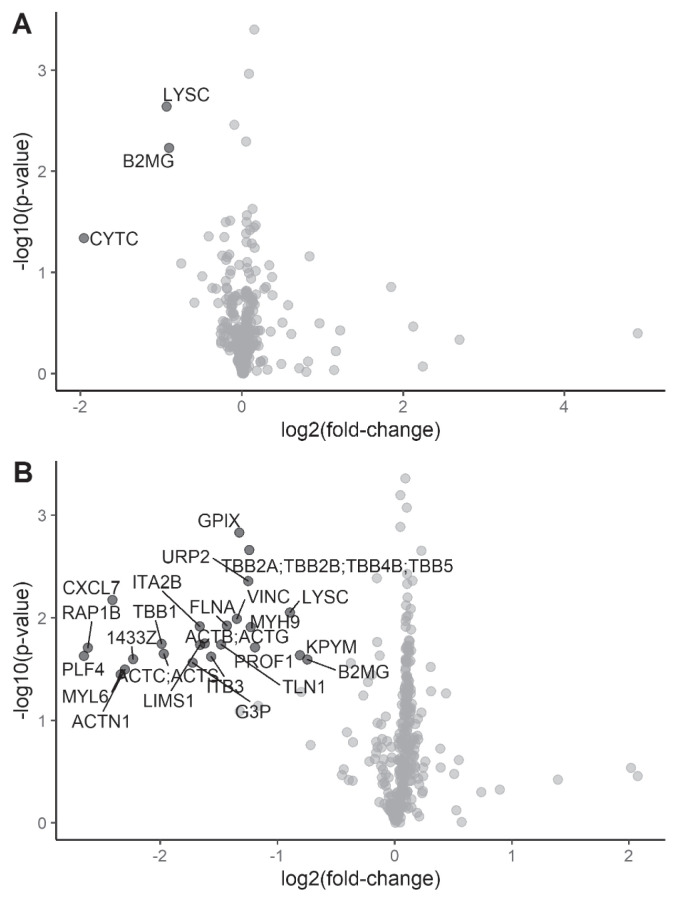

Twenty-four proteins were differentially expressed (all decreased) in pathogen-inactivated cryo derived from WB PI-cryo vs WB cryo (Table I and Figure 2B). The vast majority of these proteins are well-known platelet markers or have been recently described as quality markers for assessing platelet contamination of plasma28. In comparison, there were only three proteins that appeared to be differentially expressed (all decreased) in APH cryo as a function of PI (Table II and Figure 2A). Interestingly, these proteins, lysozyme C and β2-microglobulin, were altered to a similar extent in PI APH and WB cryo, suggesting a common mechanism. Of note, our proteomic analysis did not show the differential expression of any coagulation factors as a function of PI, despite the method quantifying the entire array of coagulation factors, except for factor VIII. We believe factor VIII is missing from the dataset because of sample heating during preparation for proteomic analysis due to the heat-sensitive nature of this factor29.

Table I.

Proteins differentially-expressed in WB PI-cryo vs WB cryo (>2 quantified precursors; %CV <30% for triplicate analyses of QC pool; Fold change ≥±1.5, PI vs control; p-value <0.05, 2-tailed, paired t-test)

| Protein group | Protein group description(s) | # Quantified precursors | %CV QC pools | Fold-change WB (PI vs control) | p-value (PI vs control) | Platelet protein |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLF4_HUMAN | Platelet factor 4 | 11 | 7.3 | −6.3 | 0.024 | Yes |

| RAP1B_HUMAN | Ras-related protein Rap-1b | 4 | 17.9 | −6.1 | 0.020 | Yes |

| CXCL7_HUMAN | Platelet basic protein | 11 | 5.6 | −5.3 | 0.007 | Yes |

| MYL6_HUMAN | Myosin light polypeptide 6 | 5 | 10.5 | −5.1 | 0.036 | Yes |

| ACTN1_HUMAN | Alpha-actinin-1 | 7 | 7.2 | −4.9 | 0.032 | Yes |

| 1433Z_HUMAN | 14-3-3 protein zeta/delta | 8 | 4.9 | −4.7 | 0.025 | Yes |

| TBB1_HUMAN | Tubulin beta-1 chain | 3 | 24.5 | −4.0 | 0.018 | Yes |

| ACTC_HUMAN; ACTS_HUMAN | Actin, alpha cardiac muscle 1; Actin, alpha skeletal muscle | 3 | 4.8 | −3.9 | 0.022 | Yes |

| G3P_HUMAN | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | 4 | 10.4 | −3.3 | 0.027 | Yes |

| ITA2B_HUMAN | Integrin alpha-IIb | 13 | 19.6 | −3.2 | 0.012 | Yes |

| LIMS1_HUMAN | LIM and senescent cell antigen-like-containing domain protein 1 | 2 | 9.8 | −3.2 | 0.018 | Yes |

| ACTB_HUMAN; ACTG_HUMAN | Actin, cytoplasmic 1; Actin, cytoplasmic 2 | 38 | 7.5 | −3.1 | 0.018 | Yes |

| ITB3_HUMAN | Integrin beta-3 | 12 | 23.7 | −3.0 | 0.024 | Yes |

| TLN1_HUMAN | Talin-1 | 56 | 4.5 | −2.8 | 0.018 | Yes |

| FLNA_HUMAN | Filamin-A | 35 | 11.4 | −2.7 | 0.012 | Yes |

| VINC_HUMAN | Vinculin | 14 | 14.2 | −2.5 | 0.010 | Yes |

| GPIX_HUMAN | Platelet glycoprotein IX | 2 | 10.6 | −2.5 | 0.001 | Yes |

| URP2_HUMAN | Fermitin family homolog 3 | 4 | 10.0 | −2.4 | 0.004 | Yes |

| TBB2A_HUMAN; TBB2B_HUMAN; TBB4B_HUMAN; TBB5_HUMAN | Tubulin beta-2A chain; Tubulin beta-2B chain; Tubulin beta-4B chain; Tubulin beta chain | 3 | 15.5 | −2.4 | 0.002 | Yes |

| MYH9_HUMAN | Myosin-9 | 34 | 2.0 | −2.3 | 0.012 | Yes |

| PROF1_HUMAN | Profilin-1 | 5 | 16.5 | −2.3 | 0.019 | Yes |

| LYSC_HUMAN | Lysozyme C | 4 | 6.7 | −1.9 | 0.009 | No |

| KPYM_HUMAN | Pyruvate kinase PKM | 6 | 4.3 | −1.8 | 0.023 | Yes |

| B2MG_HUMAN | Beta-2-microglobulin | 3 | 3.8 | −1.7 | 0.026 | No |

Figure 2.

Visualisation of differentially-expressed proteins

Volcano plots were generated in R to visualise differentially-expression proteins (absolute fold-change >1.5; p<0.05) in (A) apheresis (APH) pathogen inactivation (PI)-cryo vs APH cryo, and (B) whole blood (WB) PI-cryo vs WB cryo. Black: significant; grey: not significant.

Table II.

Proteins differentially-expressed in APH PI-cryo vs APH cryo (>2 quantified precursors; %CV <30% for triplicate analyses of QC pool; Fold change ≥±1.5, PI vs control; p-value <0.05, 2-tailed, paired t-test)

| Protein group | Protein group description | # Quantified precursors | %CV QC pools | Fold-change APH (PI vs control) | p-value (PI vs control) | Platelet protein |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CYTC_HUMAN | Cystatin-C | 3 | 21.4 | −3.9 | 0.046 | No |

| LYSC_HUMAN | Lysozyme C | 4 | 6.7 | −1.9 | 0.002 | No |

| B2MG_HUMAN | Beta-2-microglobulin | 3 | 3.8 | −1.9 | 0.006 | No |

Thrombin generation is not affected by PI

Between PI-cryo and cryo controls, no significant differences were demonstrated for lag-time (5.97 vs 6.00 min, p=0.810, reference range, 3.3–5.8 min), ETP (1,905 vs 2,215 nM*min, p=0.310), thrombin peak (253.2 vs 299.2 nM, p=0.485), ttPeak (9.01 vs 8.65 min, p=1.000, reference range, 6.1–10.9 min), and velocity index (96.6 vs 117.6 nM/min, p=0.485). Between WB-cryo and APH-cryo samples, lag-time was significantly shorter for WB-cryo (5.10 vs 6.87 min, p=0.016, reference range, 3.3–5.8 min), but there were no significant differences between groups for ETP (2,056 vs 1,963 nM*min, p=0.699), thrombin peak (283.5 vs 268.9 nM, p=1.000), ttPeak (7.94 vs 9.72 min, p=0.172, reference range, 6.1–10.9), and velocity index (105.6 vs 108.6 nM/min, p=0.699).

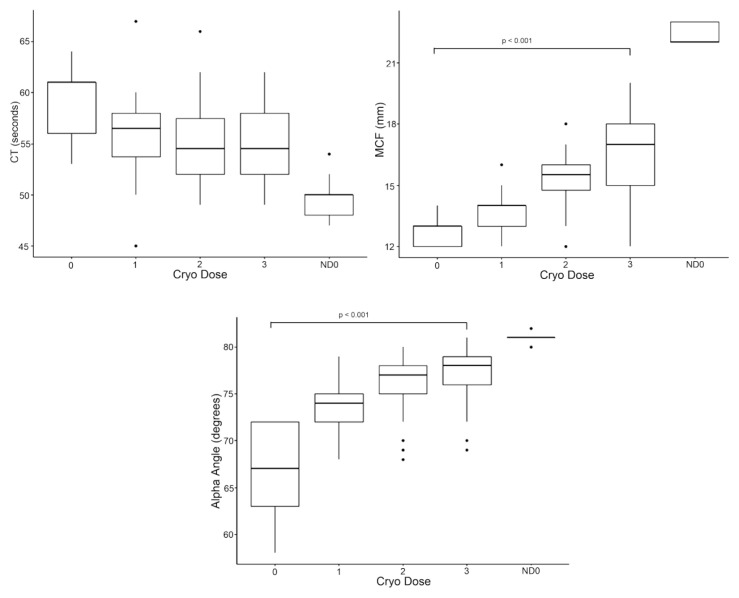

PI selectively alters rotational thromboelastometry function in WB-derived cryo

As a mixed model, successive transfusion of cryo doses to the coagulopathy model resulted in a significant rise in MCF (p<0.001) and alpha angle (p<0.001) but did not significantly affect CT (p=0.305) (Figure 3). PI did not demonstrate a significant impact on CT (1.41, 95% CI: −0.78–3.60, p=0.205), MCF (−0.13, 95% CI: −1.08–0.82, p=0.788), or alpha angle (0.28, 95% CI: −1.57–2.12, p=0.766). In subset analysis of WB-derived cryo, PI significantly prolonged CT (2.11, 95% CI: 0.17–4.06, p=0.034) and decreased MCF (−0.70, 95% CI: −1.16–−0.24, p=0.004) but had no effect on alpha angle (−0.44, 95% CI: −1.48–0.59, p=0.393). In subset analysis of PI of APH-derived cryo, PI did not significantly affect CT (0.70, 95% CI: −3.47–4.87, p=0.736), MCF (0.44, 95% CI: −1.38–2.27, p=0.627), or alpha angle (1.00, 95% CI: −2.69–4.69, p=0.588).

Figure 3.

Dose responses of ROTEM variables with cryo supplementation (mixed model) demonstrated a significant rise in maximum clot firmness (MCF) (p<0.001) (top right) and alpha angle (p<0.001) (bottom) but no effect on clotting time (CT); p=0.305 (top left)

ND0: non-dilute dose 0.

DISCUSSION

In this exploratory study we sought to quantify changes in the cryoprecipitate proteome derived from untreated and PI-treated plasma and to correlate these changes with haemostatic effects. Notably, PI of plasma used to prepare WB cryo resulted in a marked decrease in platelet-derived proteins. These changes occurred in the setting of reduced in vitro clot formation with WB cryo. Indeed, exposure to PI via the INTERCEPT® Blood System has been previously shown to reduce levels of platelet-derived extracellular vesicles in platelet concentrates compared to standard preparation methods30,31, and our results seem to provide independent confirmation of these earlier observations in a different blood product.

No difference was observed in coagulation factor content on proteomic analysis between PI-cryo and controls, in contrast to prior reports7–9,11. Previous studies have demonstrated a roughly 50% reduction in fibrinogen in cryo produced from methylene blue-treated plasma compared to untreated controls7,8,11. Plasma prepared from amotosalen and UVA treatment has previously demonstrated a reduction in coagulation factors, but with better preservation compared to other methods9. However, it may be difficult to compare results of proteomic analysis to previous studies that utilised traditional factor assays for their assessments. Proteomics represents protein content but not necessarily factor activity, given that these proteins must work as enzymatic complexes to assert their function. Therefore, although we did not see significant differences in protein content in the proteomic analysis, it remains possible that a proteomics analysis may not detect differences in factor activity in vitro or in vivo.

Despite there being no measurable changes in the coagulation factor protein content on proteomic analysis, we found that prothrombinase activity supported by MP was significantly decreased in WB but not APH PI-cryo samples compared to controls. These findings support prior work; Black et al. demonstrated with electron microscopy that the compound adsorption device utilised in the final step of the INTERCEPT® PI process to remove residual amotosalen sequesters platelet-derived extracellular vesicles30. The absolute quantity and magnitude of prothrombinase reduction evident in WB cryo as opposed to APH cryo is likely due to greater MP contamination during cryo production. The longer holding time of WB prior to individual component production as opposed to APH-derived plasma induces the release of MPs32. MP generation begins during the holding period of WB prior to separation to plasma, even under ideal refrigerated storage conditions at 4 °C in as little as eight hours, with greater MP release thereafter33. The observed outcome of decreased prothrombinase activity in the setting of stable coagulation factor content between paired groups in this study suggests potential crosstalk between soluble platelet constituents and the coagulation cascade that was not evident from our proteomic analysis. These types of events cannot be captured in our proteomic workflow because the trypsin digestion during sample preparation results in proteolysis. The physiological significance of this is unclear, especially in the light of non-significant changes in overall thrombin generation. Previous work by Ravanat et al. is consistent with our own observations that cryo produced from PI-treated plasma retains substantial thrombin generation activity despite changes in other assays34. While the present study demonstrates significant changes in prothrombinase activity, Ravanat et al. demonstrated stable thrombin generation variables in the setting of increased loss of FVIII after PI34.

The reduction in these MPs during the PI process did not affect ROTEM variables in APH PI-cryo and controls, which had minimal MP content at baseline. However, on ROTEM in vitro analysis, WB PI-cryo samples demonstrated lower MCF and prolonged CT compared to controls, suggesting a possible impact of platelet protein and MP removal on haemostasis. Prior studies examining microparticle contents of cryo and plasma products hypothesise that platelet contamination may result in von Willebrand factor cleavage by platelet calcium-activated proteases, and also platelet protease activity altering fibrinogen and fibronectin35,36. The lower MCF values observed in WB-derived samples subjected to PI supports similar previous findings4,8. Interestingly, this phenomenon is seen across multiple methods of PI, including amotosalen/UVA light and methylene blue-treated cryo4. However, the lower MCF could also be secondary to reduced fibrinogen content or activity. Indeed, previous work has shown plasma treated with amotosalen/UVA light to have upwards of 17% reduced fibrinogen activity14,34, which is likely to be reflected in subsequently-derived cryo.

Blood donor characteristics including lipid profile and age, blood product storage conditions including temperature and duration, and method of plasma production can contribute to the underlying extracellular circulating MP content30,37, in addition to the findings associated with PI in this study. The impact of the method of plasma (FFP) preparation on protein and MP composition has been previously demonstrated by Kriebardis et al. who showed that despite similar in vivo baseline patient characteristics and baseline MP content, FFP produced via buffy coat method exhibited significantly greater residual platelet content and greater total MP content (largely contributed to by platelet-derived MPs) irrespective of storage duration as compared to FFP produced via platelet-rich plasma (PRP) method37. As the cryo in this present study was derived from the latter of these two methods, these prior findings suggest that the cryo we utilised likely has lower baseline MP content, and likely lower platelet-derived protein content. As PI demonstrates a further reduction in platelet-derived MPs, starting from a lower baseline may mitigate large absolute reductions in other platelet-derived proteins, and thus may not be significantly altered in the current study. Ultimately, more platelet-derived proteins and other MPs may be significantly reduced by PI of cryo units with higher MP content, such as those derived from the buffy coat method. Furthermore, as these platelet-derived MPs demonstrate the potential to support thrombin generation, the current assessments of thrombin generation and thromboelastometry may underestimate the thrombogenic potential of certain units of cryo.

Efforts to reduce patient blood loss and transfusion burden encompass patient blood management. One proposed component, particularly in settings of surgical bleeding, is the use of platelet gels (PGs) to locally supplement post-operative haemostatic capacity at the site of surgical bleeding. This topical agent is composed of platelet-rich plasma, thrombin, and calcium, which collectively activate platelets and growth factors to promote haemostasis. Everts et al. demonstrated use of PG to reduce the incidence of allogeneic erythrocyte transfusion in knee arthroplasty, and Gunaydin et al. demonstrated superiority of PG as compared to gelatin treatment to achieve haemostasis in cardiac surgery38,39. In vitro assessment of PG with thromboelastography (TEG) has demonstrated interesting data showing that increasing thrombin concentration in the PG mileu does not correspond to significant increases in clot strength40. While this may be explained by an excessive amount of thrombin in the thromboelastograph system even at the lowest PG concentration, this differs in comparison to the dose-dependence of thromboelastometry variables observed in the present study. As a mixed model, thromboelastometry data showed increasing MCF and alpha angle with successive cryo doses, suggesting a dose-dependent haemostatic effect from this blood product. As previously mentioned, WB-cryo demonstrated a slight reduction in haemostatic capacity when subject to PI. While this in vitro evidence may not translate in vivo, it presents a possible compromise when choosing to transfuse PI-cryo. The benefit of reduced pathogen exposure may be offset by the need for repeated doses of cryo to attain similar haemostasis as non-PI cryo. Further in vivo study of PI-cryo is warranted to assess if this reduction in haemostatic capacity translates to impaired clinical outcomes. Keeping in mind that recent randomised trials suggest fibrinogen concentrate subjected to PI and purification demonstrates non-inferior haemostatic capacity to cryo in vivo in certain surgical settings41, comparison of PI-cryo meeting similar infectious risk standards as fibrinogen concentrate is warranted.

The alteration of thrombin generating MP content by the PI process may have in vivo implications on haemostatic effect with cryo transfusion, but also relevance to adverse transfusion reactions including alloimmunisation or thrombosis. Prior work has demonstrated elevated MP concentrations in prothrombotic disorders such as venous thromboembolism and heparin-induced thrombocytopenia42,43. It remains unclear if cryo containing more MPs has greater thrombogenic potential in other clinical settings warranting cryo transfusion, such as trauma or disseminated intravascular coagulation.

Limitations

This exploratory study contains the inherent limitations of such a study design. First, due to limited data of expected differences between PI cryo and controls, a power analysis was not conducted. Secondly, FVIII was not included on proteomic analysis output due to lability and heat sensitivity, as previously demonstrated; the development of an additional proteomics sample preparation method is needed in order to capture measurement of FVIII29,44. Lastly, in the present study, fibrinogen concentrations of each cryo unit were not measured with established assays.

CONCLUSIONS

In this study, we used proteomic and functional approaches to quantify changes in cryoprecipitate samples as a function of PI. The data demonstrate significant changes in platelet proteins in PI-cryo derived from WB and a reduction in prothrombinase activity likely due to filtration of MPs with PI. However, there were no significant differences in coagulant factors or effects on thrombin generation with PI. Further studies are warranted to assess the prothrombotic properties of MPs and their significance in vivo.

Supplementary Information

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Cerus Corporation (Concord, CA, USA) provided cryoprecipitate material for the study free of charge.

Footnotes

AUTHORSHIP CONTRIBUTIONS

RWK and IJW designed the study, were involved in data acquisition and analysis, and wrote the manuscript. MWF designed the study, was involved in sample processing, data acquisition and analysis, and wrote the manuscript. BAE, KS, JP and AJS were involved in data acquisition and wrote the manuscript. JWT, MAM and MJM designed the study and edited the manuscript.

DISCLOSURE OF CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

IJW and JP are Principal Investigators on industry and DARBA sponsored studies using Cerus products. Cerus provided the cryoprecipitate for this study free of charge. Otherwise, the Authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest relevant to the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Callum JL, Karkouti K, Lin Y. Cryoprecipitate: the current state of knowledge. Transfus Med Rev. 2009;23:177–88. doi: 10.1016/j.tmrv.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Curry N, Rourke C, Davenport R, et al. Early cryoprecipitate for major haemorrhage in trauma: a randomised controlled feasibility trial. Br J Anaesth. 2015;115:76–83. doi: 10.1093/bja/aev134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holcomb JB, Fox EE, Zhang X, et al. Cryoprecipitate use in the PROMMTT study. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;75(Suppl 1):S31–39. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31828fa3ed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Backholer L, Wiltshire M, Proffitt S, et al. Paired comparison of methylene blue- and amotosalen-treated plasma and cryoprecipitate. Vox Sang. 2016;110:352–361. doi: 10.1111/vox.12368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ettinger A, Miklauz MM, Bihm DJ, et al. Preparation of cryoprecipitate from riboflavin and UV light-treated plasma. Transfus Apher Sci. 2012;46:153–8. doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2012.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Irsch J, Pinkoski L, Corash L, et al. INTERCEPT plasma: comparability with conventional fresh-frozen plasma based on coagulation function--an in vitro analysis. Vox Sang. 2010;98:47–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.2009.01224.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aznar JA, Bonanad S, Montoro JM, et al. Influence of Methylene Blue Photoinactivation Treatment on Coagulation Factors from Fresh Frozen Plasma, Cryoprecipitates and Cryosupernatants. Vox Sang. 2000;79:156–60. doi: 10.1159/000031234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cardigan R, Philpot K, Cookson P, et al. Thrombin generation and clot formation in methylene blue-treated plasma and cryoprecipitate. Transfusion. 2009;49:696–703. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2008.02039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coene J, Devreese K, Sabot B, et al. Paired analysis of plasma proteins and coagulant capacity after treatment with three methods of pathogen reduction. Transfusion. 2014;54:1321–31. doi: 10.1111/trf.12460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hacquard M, Lecompte T, Belcour B, et al. Evaluation of the hemostatic potential including thrombin generation of three different therapeutic pathogen-reduced plasmas. Vox Sang. 2012;102:354–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.2011.01562.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hornsey VS, Krailadsiri P, MacDonald S, et al. Coagulation factor content of cryoprecipitate prepared from methylene blue plus light virus-inactivated plasma. Br J Haematol. 2000;109:665–70. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.02078.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Culp-Hill R, Srinivasan AJ, Gehrke S, et al. Effects of red blood cell (RBC) transfusion on sickle cell disease recipient plasma and RBC metabolism. Transfusion. 2018;58:2797–806. doi: 10.1111/trf.14931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gehrke S, Shah N, Gamboni F, et al. Metabolic impact of red blood cell exchange with rejuvenated red blood cells in sickle cell patients. Transfusion. 2019;59:3102–12. doi: 10.1111/trf.15467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ohlmann P, Hechler B, Chafey P, et al. Hemostatic properties and protein expression profile of therapeutic apheresis plasma treated with amotosalen and ultraviolet A for pathogen inactivation. Transfusion. 2016;56:2239–47. doi: 10.1111/trf.13670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bruderer R, Muntel J, Muller S, et al. Analysis of 1508 Plasma Samples by Capillary-Flow Data-Independent Acquisition Profiles Proteomics of Weight Loss and Maintenance. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2019;18:1242–54. doi: 10.1074/mcp.RA118.001288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu Y, Buil A, Collins BC, et al. Quantitative variability of 342 plasma proteins in a human twin population. Mol Syst Biol. 2015;11:786. doi: 10.15252/msb.20145728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Niu L, Geyer PE, Wewer Albrechtsen NJ, et al. Plasma proteome profiling discovers novel proteins associated with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Mol Syst Biol. 2019;15:e8793. doi: 10.15252/msb.20188793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cid J, Caballo C, Pino M, et al. Quantitative and qualitative analysis of coagulation factors in cryoprecipitate prepared from fresh-frozen plasma inactivated with amotosalen and ultraviolet A light. Transfusion. 2013;53:600–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2012.03763.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roback JD, Grossman BJ, Harris T, et al. AABB Technical Manual. 17th ed. Bethesda, MD: AABB; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schlenke P, Hervig T, Isola H, et al. Photochemical treatment of plasma with amotosalen and UVA light: process validation in three European blood centers. Transfusion. 2008;48:697–705. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2007.01594.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cushing MM, Asmis LM, Harris RM, et al. Efficacy of a new pathogen-reduced cryoprecipitate stored 5 days after thawing to correct dilutional coagulopathy in vitro. Transfusion. 2019;59:1818–26. doi: 10.1111/trf.15157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schaller TH, Foster MW, Thompson JW, et al. Pharmacokinetic analysis of a novel human EGFRvIII: CD3 bispecific antibody in plasma and whole blood using a high-resolution targeted mass spectrometry approach. J Proteome Res. 2019;18:3032–41. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.9b00145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mooberry MJ, Bradford R, Hobl EL, et al. Procoagulant microparticles promote coagulation in a factor XI-dependent manner in human endotoxemia. J Thromb Haemost. 2016;14:1031–42. doi: 10.1111/jth.13285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Theusinger OM, Nurnberg J, Asmis LM, et al. Rotation thromboelastometry (ROTEM) stability and reproducibility over time. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2010;37:677–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2009.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Droubatchevskaia N, Wong MP, Chipperfield KM, et al. Guidelines for cryoprecipitate transfusion. B C Med J. 2007;49:441–5. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sharma R, Sharma S. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): 2019. Physiology, Blood Volume. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bloemen S, Huskens D, Konings J, et al. Interindividual variability and normal ranges of whole blood and plasma thrombin generation. J Appl Lab Med. 2017;2:150–64. doi: 10.1373/jalm.2017.023630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Geyer PE, Voytik E, Treit PV, et al. Plasma Proteome Profiling to detect and avoid sample-related biases in biomarker studies. EMBO Mol Med. 2019:e10427. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201910427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boylan B, Miller CH. Effects of pre-analytical heat treatment in factor VIII (FVIII) inhibitor assays on FVIII antibody levels. Haemophilia. 2018;24:487–91. doi: 10.1111/hae.13435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Black A, Orso E, Kelsch R, et al. Analysis of platelet-derived extracellular vesicles in plateletpheresis concentrates: a multicenter study. Transfusion. 2017;57:1459–69. doi: 10.1111/trf.14109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stivala S, Gobbato S, Infanti L, et al. Amotosalen/ultraviolet A pathogen inactivation technology reduces platelet activatability, induces apoptosis and accelerates clearance. Haematologica. 2017;102:1650–60. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2017.164137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sugawara A, Nollet KE, Yajima K, et al. Preventing platelet-derived microparticle formation--and possible side effects-with prestorage leukofiltration of whole blood. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134:771–5. doi: 10.5858/134.5.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lawrie AS, Cardigan RA, Williamson LM, et al. The dynamics of clot formation in fresh-frozen plasma. Vox Sang. 2008;94:306–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.2008.01037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ravanat C, Dupuis A, Marpaux N, et al. In vitro quality of amotosalen-UVA pathogen-inactivated mini-pool plasma prepared from whole blood stored overnight. Vox Sang. 2018;113:622–31. doi: 10.1111/vox.12697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kunicki TJ, Montgomery RR, Schullek J. Cleavage of human von Willebrand factor by platelet calcium-activated protease. Blood. 1985;65:352–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Snyder EL, Ferri PM, Mosher DF. Fibronectin in liquid and frozen stored blood components. Transfusion. 1984;24:53–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1984.24184122562.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kriebardis AG, Antonelou MH, Georgatzakou HT, et al. Microparticles variability in fresh frozen plasma: preparation protocol and storage time effects. Blood Transfus. 2016;14:228–37. doi: 10.2450/2016.0179-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Everts PA, Devilee RJ, Brown Mahoney C, et al. Platelet gel and fibrin sealant reduce allogeneic blood transfusions in total knee arthroplasty. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2006;50:593–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2006.001005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gunaydin S, McCusker K, Sari T, et al. Clinical impact and biomaterial evaluation of autologous platelet gel in cardiac surgery. Perfusion. 2008;23:179–86. doi: 10.1177/0267659108097783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ellis WC, Cassidy LK, Finney AS, et al. Thrombelastograph (TEG) analysis of platelet gel formed with different thrombin concentrations. J Extra Corpor Technol. 2005;37:52–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Callum J, Farkouh ME, Scales DC, et al. Effect of fibrinogen concentrate vs cryoprecipitate on blood component transfusion after cardiac surgery: the FIBRES randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;322:1–11. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.17312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chirinos JA, Heresi GA, Velasquez H, et al. Elevation of endothelial microparticles, platelets, and leukocyte activation in patients with venous thromboembolism. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:1467–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.12.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hughes M, Hayward CP, Warkentin TE, et al. Morphological analysis of microparticle generation in heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Blood. 2000;96:188–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Simon TL. Changes in plasma coagulation factors during blood storage. Plasma Therapy and Transfusion Technology. 1988;9:309–15. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.